Abstract

Trauma theories suggest that childhood maltreatment (CM) may partly explain intimacy problems in romantic relationships. However, empirical studies have yielded conflicting findings, likely due to the varying conceptualizations of intimacy. Findings that support long-term negative effects of CM on sexual and relationship satisfaction are almost exclusively based on cross-sectional intra-individual data, precluding the examination of mediating pathways and of dyadic interactions between individuals reporting CM and their partners. This study used a dyadic perspective to examine the associations between CM and the different components of intimacy based on the interpersonal process model of intimacy: self-disclosure, perceived partner disclosure, and perceived partner responsiveness. We also tested the mediating role of these intimacy components at Time 1 in the relations between CM and sexual and relationship satisfaction 6 months later. A sample of 365 heterosexual couples completed self-report questionnaires. Results of path analyses within an actor–partner interdependence framework showed that women and men’s higher levels of CM did not affect self-disclosure, but was negatively associated with their own perception of partner disclosure and responsiveness. In turn, women and men’s perception of partner responsiveness at Time 1 was positively associated with their own sexual satisfaction, as well as their own and their partner’s relationship satisfaction at Time 2. Thus, perception of partner responsiveness mediated the associations between CM and poorer sexual and relationship satisfaction. The overall findings may inform the development of couple intervention that targets the enhancement of intimacy to promote sexual and relationship well-being in couples where one partner experienced CM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Childhood maltreatment (CM) is a prevalent public health and social welfare concern with well-established long-lasting consequences. CM refers to any act of commission or omission that results in harm, potential for harm, or threat of harm to a child, such as physical, emotional, or sexual abuse, as well as physical or emotional neglect (Briere & Scott, 2014; Gilbert et al., 2009). Although most studies have focused on sexual abuse alone, research indicates that individuals tend to experience multiple types of CM and that emotional abuse and neglect are also related to significant long-lasting repercussions (Bigras, Godbout, Hébert, Runtz, & Daspe, 2015; Briere, Agee, & Dietrich, 2016). Indeed, in line with the general effect theory and past empirical research, an increasing number of forms of CM is associated with more adverse outcomes (Bigras, Godbout, Hébert, & Sabourin, 2017; Higgins & McCabe, 2000). In large population-based studies, 35–40% of individuals retrospectively report at least one type of CM with multiple chronic victimizations being the norm (Cyr et al., 2013; MacDonald et al., 2016; Vachon, Krueger, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, 2015). Although studies suggest that some individuals with CM history report adaptive resilient adult functioning (Domhardt, Munzer, Fegert, & Goldbeck, 2015), most of the existing literature points toward wide-ranging long-term negative psychosocial effects of CM, with multiple chronic victimizations predicting poorer functioning (Bigras et al., 2017).

CM is a relational trauma, whereby the betrayal, powerlessness, breach of trust, or disregard experienced early on may disturb future romantic relationships in several ways (Freyd & Birrell, 2013; Herman, 1992). An emerging empirical literature suggests that all forms of CM are associated with romantic relationship difficulties even when controlling for childhood family dynamics and environment (Colman & Widom, 2004; Seehuus, Clifton, & Rellini, 2015). Specifically, CM is related to relationship dissolution or instability (Colman & Widom, 2004; Whisman, 2006), domestic violence (Godbout et al., 2017), lower trust (DiLillo et al., 2009), sexual difficulties (DiLillo, Lewis, & Loreto-Colgan, 2007; Seehuus et al., 2015), and ultimately lower levels of sexual and relationship satisfaction (Rellini, Vujanovic, Gilbert, & Zvolensky, 2012; Vaillancourt-Morel et al., 2015).

Yet, empirical findings supporting negative effects of CM on sexual and relationship satisfaction are almost exclusively based on intra-individual data, precluding the examination of dyadic interactions between individuals reporting CM and their partners’ sexual and relationship outcomes. As suggested by secondary trauma theory, partners of individuals reporting CM may also struggle with sexual and relationship issues (Nelson & Wampler, 2000). The few studies that have examined the cross-partner effects of CM support this dyadic impact. Partners of individuals reporting childhood physical abuse report poorer relationship quality (Whisman, 2014). Men and women’s childhood physical and psychological abuse is related to lower couple adjustment in their partners via their own higher attachment avoidance and anxiety (Godbout, Dutton, Lussier, & Sabourin, 2009). Finally, higher levels of CM reported by male partners of women with genito-pelvic pain are associated with women’s lower relationship satisfaction (Corsini-Munt, Bergeron, Rosen, Beaulieu, & Steben, 2017). Even if some of these findings are limited by the examination of specific traumas and are circumscribed to relationship satisfaction, they point toward the necessity of including both partners to examine the effects of CM in one partner on sexual and relationship satisfaction within the couple.

Cross-sectional data also limit what we know about possible affective interpersonal processes that may underlie the low sexual and relationship satisfaction characterizing the relationships of CM victims (DiLillo, 2001; Rellini, 2008). Prospective research identifying such processes may yield targets for therapeutic intervention and thus help prevent and treat sexual and relationship problems among adults with CM, who comprise 60% of couples and 80% of individuals seeking sex or couple therapy (Berthelot et al., 2014; Bigras et al., 2017; Nelson & Wampler, 2000). The present study used a dyadic longitudinal perspective to examine one potential couple process—intimacy—explaining the association between CM and sexual and relationship satisfaction in community couples.

Childhood Maltreatment and Intimacy

Empirical studies examining whether adults reporting CM experience problems with intimacy have yielded conflicting, mostly nonsignificant, findings. In a sample of 192 young adult women, Rellini et al. (2012) reported no significant association between CM and intimacy. Similarly, in a university sample of 315 women, Davis, Petretic-Jackson, and Ting (2001) found that CM was not a significant predictor of intimacy and trust in participants’ current relationship. This result was replicated by Seehuus et al. (2015) in a sample of 417 young adult women by examining the effect of CM on a latent relationship quality indicator that included an intimacy factor. In a sample of 174 undergraduate students, DiLillo et al. (2007) showed that CM had a negative effect on the current level of intimacy for women, but not for men. The nonsignificant findings are likely due to the use of a restrictive conceptualization of intimacy. Indeed, apart from DiLillo et al.’s study which reported a negative association in women, studies to date assessed only the “self-disclosure” dimension of intimacy, i.e., how much the person shared secrets or feelings with their partner (Davis et al., 2001; Rellini et al., 2012; Seehuus et al., 2015). Thus, nonsignificant results only show that CM does not affect the self-disclosure component of intimacy, but this narrow definition overlooks the dynamic process of intimacy. To rectify this conceptual limitation, the present study used the interpersonal process model of intimacy.

The Interpersonal Process Model of Intimacy

Intimacy in romantic relationships is conceptualized as an interpersonal dynamic process with multiple components that lead to feelings of closeness and connectedness between partners (Reis & Shaver, 1988). The interpersonal process model of intimacy developed by Reis and Shaver (1988) posits that intimacy begins with self-disclosure of feelings and personal thoughts to the partner, who, in return, emits disclosures and empathic behaviors that are responsive to the initial disclosure. If the response of the partner is perceived as demonstrating understanding, validation, and caring, intimacy is increased. Laurenceau, Barrett, and Rovine (2005) validated this theoretical model and stressed the importance of the three components of intimacy: self-disclosure, perceived partner disclosure, and perceived partner responsiveness.

Given that past studies mainly examined the effect of CM on self-disclosure, the effects on the other components of intimacy remain to be clarified. CM may affect intimacy by interfering with the perception of partner responsiveness or partner disclosure. This hypothesis is consistent with trauma theoretical perspectives, such as the self-trauma model (Briere & Scott, 2014) and the betrayal trauma theory (Freyd & Birrell, 2013), which propose that CM may result in high levels of distrust in romantic partners or negative relational schemas and behaviors. Indeed, the internalization of others as caring and protective may be strongly weakened in neglecting or abusing families, leading the individuals reporting CM to view others, particularly a significant other, as inherently intrusive, rejecting, or unavailable (Briere, 2002).

Intimacy as a Mediator of the Relation Between Childhood Maltreatment and Sexual and Relationship Satisfaction

Although positively correlated, sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction are distinct constructs that may have different determinants (Fallis, Rehman, Woody, & Purdon, 2016). CM may affect the perception of partner disclosure or responsiveness, with resultant relationship dissatisfaction, as much as it may explain why some individuals reporting CM are more likely to consider sexual experiences as unsatisfying. Indeed, lack of intimacy is a common complaint in couple therapy and may result in both sexual and relational difficulties (Whisman, Dixon, & Johnson, 1997). Cross-sectional dyadic studies have shown that all components of intimacy were positively correlated with women and men’s own relationship and sexual satisfaction and with their partners’ relationship satisfaction (MacNeil & Byers, 2005; Rubin & Campbell, 2012). Even if non-recursive models show reciprocal relationships between intimacy and satisfaction indicators (Yoo, Bartle-Haring, Day, & Gangamma, 2014), the directionality of the intimacy–satisfaction effect is mainly based on theory and practice, whereby intimacy precedes overall satisfaction indicators (MacNeil & Byers, 2005). The present study examined the association between intimacy at one time in the relationship and sexual and relationship satisfaction 6 months later. This longitudinal methodology allows one to elucidate the mediational role of intimacy by applying temporal precedence of the mediator while decreasing shared variance and hence the probability of inflated relations (Kraemer, Kiernan, Essex, & Kupfer, 2008).

Current Study

Using a dyadic perspective, the current study examined the associations between higher levels of CM and different components of intimacy: self-disclosure, perceived partner disclosure, and perceived partner responsiveness. Moreover, we examined the potential role of these intimacy components at Time 1 in the relations between CM and sexual and relationship satisfaction 6 months later. Given that past studies assessing only self-disclosure reported nonsignificant associations, we predicted that higher levels of CM would be negatively associated with perceived partner disclosure and partner responsiveness at Time 1, which would, in turn, be associated with sexual and relationship satisfaction at Time 2, mediating the negative association between CM and poorer sexual and relationship satisfaction. We also predicted that higher levels of CM would be associated with lower partner intimacy (i.e., self-disclosure, perceived partner disclosure, and responsiveness) at Time 1, which would, in turn, be associated with lower partner sexual and relationship satisfaction at Time 2.

Method

Participants

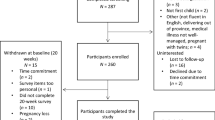

A convenience sample of 365 heterosexual couples was recruited between January and December 2016 via online advertisements (e.g., social media, classified advertisement Web sites), email lists, and posters or flyers distributed in various locations. The present study was part of a larger research project on the role of negative experiences during childhood in community couples’ romantic relationships. Interested participants were contacted by a research assistant for a brief telephone eligibility interview. Both partners had to be at least 18 years of age and together for at least 6 months. Couples were excluded if women were pregnant at Time 1 and, at Time 2, only intact couples were included.

Procedure

At Time 1, eligible couples independently accessed a hyperlink to complete a consent form and a series of self-report questionnaires hosted by Qualtrics Research Suite. Six months later, couples were contacted by email to complete Time 2 questionnaires. Each partner received a $10 gift card after each completion and was eligible to win a $100 gift card as compensation for their time. All procedures were approved by our university’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Childhood Maltreatment

CM was measured at Time 1 using the short form of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein et al., 1994; 2003). This 25-item measure retrospectively assesses the extent of five types of CM: emotional, physical, and sexual abuse as well as emotional and physical neglect. The CTQ scales were based on the following definitions of abuse and neglect. Sexual abuse was defined as sexual contact or conduct between a child younger than 18 years of age and an older individual. Physical abuse was defined as bodily assaults on a child by an older individual that posed a risk of or resulted in injury. Emotional abuse was defined as verbal assaults on a child’s sense of worth or well-being or any humiliating or demeaning behavior directed toward a child by an older individual. Physical neglect was defined as the failure of caretakers to provide for a child’s basic physical needs, including food, shelter, clothing, safety, and health care. Emotional neglect was defined as the failure of caretakers to meet children’s basic emotional and psychological needs, including love, belonging, nurturance, and support (Bernstein & Fink, 1998). Participants rated the frequency with which various events took place when they were growing up on a five-point Likert scale (1 = never true, 5 = very often true). The items were summed to obtain a total score ranging from 25 to 125, with higher levels of CM reflecting multiple chronic victimizations given it combines the frequency of each type of CM and the cumulative experience of multiple types of CM. The CTQ demonstrates good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .61–.95), measurement invariance across four samples including a community sample, good temporal stability over a 2- to 6-month interval (r =.79–.95), and good convergent and discriminant validity with a structured trauma interview (Bernstein et al., 1994, 2003; Paquette, Laporte, Bigras, & Zoccolillo, 2004). In the present study, Cronbach’s α was .92 for women and .88 for men.

Intimacy

Intimacy in the relationship was measured at Time 1 using the relationship intimacy measure (Bois, Bergeron, Rosen, McDuff, & Gregoire, 2013) which was designed based on the diary measure of Laurenceau, Barrett, and Pietromonaco (1998) and reflects the various components of intimacy as theorized in Reis and Shaver’s (1988) model of intimacy. This eight-item scale included three subscales that ask both partners to rate in general in the relationship (1) the degree to which they disclosed thoughts and feelings to their partner (self-disclosure, two items), (2) the degree to which they perceived their partner’s disclosed thoughts and feelings (perceived partner disclosure, two items), and (3) the degree to which they felt understood, validated, accepted, and cared for by their partner (perceived partner responsiveness, four items). These subscales were rated on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 7 = a lot) which were summed to provide a subscale score ranging from 2 to 14 or 4 to 28, with higher scores indicating greater intimacy. This scale achieves good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .91 and .92; Bois et al., 2013) and good construct validity with all subscales predicting intimacy across a range of social relationships (Laurenceau et al., 1998, 2005). In the present study, Cronbach’s α of the three subscales ranged from .88 to .89 for women and men.

Sexual Satisfaction

At Time 2, the global measure of sexual satisfaction (GMSEX) was used to evaluate global satisfaction with various aspects of the sexual relationship (Lawrance & Byers, 1992, 1998). This scale includes five items rated on seven-point bipolar scales: good–bad, pleasant–unpleasant, positive–negative, satisfying–unsatisfying, and valuable–worthless. Items were summed to provide a total score ranging from 5 to 35, where higher scores reflected greater sexual satisfaction. This scale demonstrates good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .96), good 2-week and 3-month test–retest reliability, and good convergent validity with other measures of sexual satisfaction (Lawrance & Byers, 1992, 1995). In the present study, Cronbach’s α was .95 for women and .93 for men.

Relationship Satisfaction

At Time 2, the 32-item Couple Satisfaction Index (CSI; Funk & Rogge, 2007) was used to assess one’s subjective global evaluation of one’s relationship, without any reference to sexual satisfaction. One global item used a seven-point scale, whereas the other 31 items used a variety of six-point scales. All items were summed to obtain a total score ranging from 0 to 161, with higher scores indicating greater relationship satisfaction. The CSI demonstrates good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .84–.98; Graham, Diebels, & Barnow, 2011), correlates highly with other measures of relationship satisfaction, and discriminates between distressed and nondistressed relationships (Funk & Rogge, 2007). In the present study, Cronbach’s α was .97 for both women and men.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive and correlation analyses were computed using SPSS 20 to examine sample characteristics, mean differences between men and women, and the relationships between study variables. The hypotheses were then tested using Mplus version 8.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015). First, the associations between CM and intimacy components were examined using path analysis within an actor–partner interdependence model (APIM; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). Second, according to the results of this preliminary model, the indirect effects of CM on sexual and relationship satisfaction through intimacy were examined using an APIM. As suggested by the MacArthur approach, we used a longitudinal design with two time points to examine mediation as CM is a fixed marker that does not change over time. Indeed, as it happens in childhood, it precedes any event in adulthood (Kraemer et al., 2008).

APIM analyses were conducted because they account for the interdependence between partners and allow testing for actor effects while controlling for partner effects, and for partner effects while controlling for actor effects. Theoretically, partners were expected to be distinguishable by their gender, which was confirmed by omnibus within-dyad tests of distinguishability (Kenny et al., 2006): CM–intimacy model: χ2(20) = 99.54, p < .001; CM–intimacy–sexual and relationship satisfaction model: χ2(42) = 139.34, p < .001. These chi-square tests constrained means, variances, and intrapersonal and interpersonal covariances to be equal across genders, with a significant p value, indicating that the pattern of means, variances, and covariances differed significantly between women and men.

Because study variables were naturally non-normally distributed (kurtosis varied between − 0.24 and 5.09 and skewness between − 1.97 and 2.02), the maximum likelihood parameter estimates with standard errors and chi-square test statistics that are robust to non-normality were used (MLR; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015). Missing data (in women ranging from 1.9% for intimacy subscales to 18.8% for sexual satisfaction at Time 2 and in men ranging from 12.9% for intimacy subscales to 21.7% for sexual satisfaction at Time 2) were treated using full-information maximum likelihood. Most missing data at Time 2 are due to dropout after Time 1. Based on Kline’s (2015) guidelines, overall fit model was tested by considering together several fit indices: the chi-square statistic, the comparative fit index (CFI), the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR). Indicators of good fit are a non-statistically significant chi-square value, a CFI value of .95 or higher, a RMSEA value below .05, and a SRMR value below .08 (Kline, 2015). Following Preacher and Hayes’ (2008) recommendations, bootstrapping analyses with 5000 resamples were conducted to examine the significance of indirect effects.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Of the 470 interested couples, 28 (6.0%) refused to participate, 27 (5.7%) did not meet eligibility criteria, and 32 (6.8%) withdrew before starting the survey. Of the 383 eligible couples, nine couples were excluded because they had missing data on all variables included in the present study and nine same-sex couples were excluded because the test of distinguishability revealed that the couples were distinguishable by participant gender. Therefore, the final sample size at Time 1 was 365 heterosexual couples. Sociodemographic characteristics are given in Table 1. At Time 2, 19 couples were excluded because they were separated. At Time 1, compared with couples who separated, intact couples reported a significantly higher relationship duration (M = 5.19 years, SD = 4.62; M = 2.29 years, SD = 1.54; t[300] = 6.48, p < .001) and a relationship status that suggested more commitment (i.e., lower proportion of couples not living together and higher proportion of cohabiting or married couples; χ2(2) = 11.99, p = .002). There were no other significant differences on Time 1 sociodemographic variables and on Time 1 study variables (CM and intimacy components). A total of 283 couples completed the questionnaires at Time 2, for a retention rate of 81.8%. Reasons for not completing Time 2 included not being able to recontact or lack of interest in participating. The final sample size for the analyses including Time 2 outcomes was 346 couples as missing data were treated using full-information maximum likelihood.

Descriptive Statistics

Means and SD for CM, intimacy at Time 1, and sexual and relationship satisfaction at Time 2 in women and men are given in Table 2. To account for non-independence between partners, paired t tests using gender as a repeated measure indicated that women reported significantly more self-disclosure and less partner disclosure than men. Women were also significantly more satisfied with their relationship than men.

Bivariate Correlations

Women and men’s correlations between CM, intimacy, and sexual and relationship satisfaction are given in Table 3. Correlations between five types of CM, intimacy, and sexual and relationship satisfaction are given in Supplementary Table 1. Non-independence of the dyadic data was supported by significant small-to-medium correlations between men and women’s study variables. The correlational analyses revealed preliminary relationships in line with our hypothetical models. Women and men’s higher levels of CM were negatively related to their own perception of partner disclosure and their own perception of partner responsiveness, with small effect sizes. Women’s higher levels of CM were also negatively associated with their own self-disclosure and men’s perception of partner responsiveness, with small effect sizes. Women and men’s higher levels of CM were negatively associated with their own and their partner’s sexual and relationship satisfaction, with small effect sizes, except for the association between men’s higher levels of CM and their partner’s sexual satisfaction which was nonsignificant. For both men and women, all subscales of intimacy were positively related, with small-to-large effect sizes, to their own and their partner’s sexual and relationship satisfaction.

Preliminary correlational analyses were conducted to examine the associations between sociodemographic variables and outcomes. Relationship duration was significantly correlated with women’s perception of partner responsiveness, r(356) = − .17, p = .001. Thus, relationship duration was included as a covariate in all models.

Actor–Partner Interdependence Models

Childhood Maltreatment and Intimacy

A path analysis model examined the actor and partner associations between CM and the different components of intimacy at Time 1, controlling for relationship duration (N = 365). Results indicated good fit for this model: χ2(2) = 3.19, p = .203; RMSEA = .04, 90% CI: .00–.12; CFI = 0.99; SRMR = 0.01. Results showed actor effects wherein women and men’s higher levels of CM were associated with their own lower perception of partner disclosure (βwomen = − .16, p = .010; βmen = − .15, p = .018) and responsiveness (βwomen = − .15, p = .021; βmen = − .17, p = .012). Given that women and men’s higher levels of CM were unrelated to actor (βwomen = − .11, p = .160; βmen = − .07, p = .285) and partner (βwomen = − .03, p = .615; βmen = − .04, p = .521) self-disclosure, the further path analysis model excluded self-disclosure.

Childhood Maltreatment, Intimacy, and Sexual and Relationship Satisfaction

A path analysis model was tested to examine the indirect actor and partner associations between CM and sexual and relationship satisfaction at Time 2, mediated through perception of partner disclosure and responsiveness at Time 1 (N = 346). Relationship duration was included as a control variable. The final model, presented in Fig. 1, fit the data well: χ2(2) = 3.38, p = .184; RMSEA = .045, 90% CI(.000–.125); CFI = 0.998; SRMR = 0.012. Results showed that for women and men, higher levels of CM were negatively associated with their own perception of partner disclosure and their own perception of partner responsiveness. In turn, women’s perception of partner disclosure was positively associated with their own sexual satisfaction, while women and men’s perception of partner responsiveness was positively associated with their own sexual satisfaction as well as their own and their partner’s relationship satisfaction.

Actor–partner interdependence model of the associations between childhood maltreatment, intimacy at Time 1, and sexual and relationship satisfaction at Time 2. Note: M = men, W = women. The regression coefficients are standardized scores. Direct actor and partner paths between childhood maltreatment and sexual and relationship satisfaction were estimated in the model. All covariances between intimacy subscales and between sexual and relationship outcomes were estimated in the model. The effects of relationship duration on intimacy and sexual and relationship satisfaction were included as a covariate. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Women and men’s actor associations between CM and sexual satisfaction were significant before the inclusion of mediators (βwomen = − .13, p = .025; βmen = − 15, p = .027) and became nonsignificant after the inclusion of the intimacy subscales (βwomen = − .07, p = .150; βmen = − .09, p = .169). The associations between women and men’s CM and their partner’s sexual satisfaction were nonsignificant before and after the inclusion of mediators (before: βwomen = − .13, p = .066; after: βwomen = − .07, p = .176; before: βmen = .002, p = .972; after βmen = .05, p = .309). Actor and partner associations between men’s CM and relationship satisfaction were significant before the inclusion of mediators (actor: β = − .19, p = .011; partner: β = − .19, p = .008). After the inclusion of intimacy subscales, the actor association was no longer significant (β = − .10, p = .095), while the partner association remained significant (β = − .12, p = .026). Actor and partner associations between women’s CM and relationship satisfaction were nonsignificant before and after the inclusion of mediators (actor before: β = − .09, p = .242; after: β = − .01, p = .880; partner before: β = − .13, p = .107; after: β = − .06, p = .327). To obtain a parsimonious model and optimize statistical power, all nonsignificant direct paths between CM and sexual and relationship satisfaction were removed from the model. These modifications improved model fit: χ2(9) = 12.90, p = .167; RMSEA = .035, 90% CI(.00–.08); CFI = 0.965; SRMR = 0.025.

Bootstrapping analyses indicated that the negative indirect effect of women’s CM on their own sexual satisfaction through their own perception of partner disclosure was significant (b = − .01, 95% bootstrap CI − .03 to − .001) as were the negative indirect effects of women and men’s CM on their own sexual satisfaction through their own perception of partner responsiveness (bwomen = − .02, 95% bootstrap CI − .06 to − .01; bmen = − .04, 95% bootstrap CI − .08 to − .01). The negative indirect effects of women and men’s CM on their own relationship satisfaction through their own perception of partner responsiveness were significant (βwomen = − .14, 95% bootstrap CI − .31 to − .04; βmen = − .23, 95% bootstrap CI − .46 to − .07). The indirect effects of women and men’s CM on their partner’s relationship satisfaction through their own perception of partner responsiveness were also significant (βwomen = − 06, 95% bootstrap CI − .18 to − .01; βmen = − .11, 95% bootstrap CI − .30 to − .02). The final model explained 24.3% of the variance in sexual satisfaction for women and 28.5% for men, as well as 41.5% of the variance in relationship satisfaction for women and 46.5% for men.

Discussion

This study contributes to a growing body of research on the long-term role of CM in understanding adult sexuality and relationships in a sample of relatively satisfied couples. Using a prospective dyadic design, we examined if CM was associated with lower intimacy and whether these intimacy difficulties at Time 1 mediated the negative associations between CM and sexual and relationship satisfaction 6 months later. A primary finding was that both women and men’s higher levels of CM did not affect the self-disclosure component of intimacy, but rather had negative associations with their own perception of partner disclosure and responsiveness. The second main finding was that women’s and men’s higher levels of CM were negatively associated with their own sexual and relationship satisfaction and their partner’s relationship satisfaction, mainly through lower perceived partner responsiveness.

Childhood Maltreatment and Intimacy

Our findings showed that for both women and men, higher levels of CM did not affect the self-disclosure component of intimacy. This is in line with nonsignificant associations reported in past studies that assessed intimacy only based on self-disclosure (Davis et al., 2001; Rellini et al., 2012; Seehuus et al., 2015). Thus, having experienced higher levels of CM does not affect the ability of these individuals to disclose intimate thoughts and feelings with their romantic partner. However, we know little about the content and the context of these self-disclosures. For some individuals reporting CM history, self-disclosure may be a way of processing their own emotions and traumatic past with the support of the partner, while others may self-disclose with compulsion or insensitivity to the partner’s needs or responses, not necessarily leading to more intimacy. Even if CM does not affect the amount of reports of self-disclosure of individuals reporting CM history or their partners, more insight concerning the self-disclosing process of participants reporting CM is needed before concluding that CM has no effect on this component of intimacy.

The present findings, however, showed that higher levels of CM were negatively associated with other components of intimacy. Indeed, when women and men experienced higher levels of CM, they also reported that their partner was less likely to disclose intimate thoughts and feelings and they also felt less well understood, validated, accepted, and cared for by their partner. These results suggest that the perception of the partner’s behavior is particularly important in difficulties with intimacy of individuals reporting CM. This is in line with past quantitative and qualitative studies describing the relational dynamics of men and women who self-reported CM experiences (DiLillo & Long, 1999; MacIntosh, 2017; Mullen, Martin, Anderson, Romans, & Herbison, 1994). Perception of their partner as less disclosing and less empathically responsive may be explained by past results, reporting that individuals with CM history report more rejection or interpersonal sensitivity (Godbout et al., 2009; Luterek, Harb, Heimberg, & Marx, 2004), higher levels of distrust or suspiciousness toward partners (Cole & Putnam, 1992; DiLillo & Long, 1999), and a propensity to perceive their partners as uncaring or engaging in more negative exchanges (Mullen et al., 1994; Whisman, 2014). These difficulties may lead to frequent misinterpretations of others’ interpersonal behaviors, particularly within a romantic relationship. Indeed, the perception of partner disclosure as well as partner understanding, validation, and care may be biased or distorted in individuals having experienced CM in which a parent or a caretaker, who was supposed to take care of them, abused, neglected, or invalidated them. In a romantic relationship, participants reporting CM may have difficulty to develop and maintain a vision of the partner as genuinely caring and protective. This negative perception of partner behaviors may explain the development or maintenance of rigid negative interactions in some couples consulting for couple difficulties where one partner experienced CM (MacIntosh, 2017).

This childhood-to-adulthood interpersonal continuity in traumatic processes is described in most trauma theoretical models. They propose that growing up in abusing or neglecting families interferes with the internalization of loving and protective others and may rather imbue relationships with feelings of betrayal, exploitation, powerlessness, bewilderment, or shame (Briere & Scott, 2014; Finkelhor & Browne, 1985; Freyd & Birrell, 2013; Pearlman, 1997). These feelings and relational schemas perpetuate into adulthood via negative self-inferences and other inferences that may be primed by the intimacy context of a close relationship, leading to negative perceptions of the partner regardless of his/her actual behaviors or in reaction to normal experiences of empathic failures from the partner. In these situations, memories of the abuser as dangerous, rejecting, or unavailable may become temporarily or chronically intertwined with the perception of the partner (van der Kold, 1989). This process also refers in some parts to the notion of internal working models in attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969), in which CM has been shown to disturb attachment security and strategies for regulating affect in the context of close relationships (Frias, Brassard, & Shaver, 2014; Godbout et al., 2009).

In the present study, however, it was not possible to determine whether the dynamics were fueled by biased perceptions induced by past CM or a reflection of actual partner behaviors. In fact, individuals reporting CM may also be in a relationship with a partner that effectively self-discloses less and shows insufficient understanding, validation, and caring. This hypothesis is in line with results of past studies, showing that CM is associated with an increased risk of repetition of abusive relationships and of being victims of partner violence (Drapeau & Perry, 2004; Godbout et al., 2017). Future studies should ideally combine self-report measures of perceptions and coders’ observations of recorded intimacy interactions between partners to shed light on both interpretations.

Partner Responsiveness as a Mediator of the Relation Between Childhood Maltreatment and Sexual and Relationship Satisfaction

Findings also showed that, for both women and men, it was mainly the perception of lower partner responsiveness that explained the negative associations between higher levels of CM and poorer sexual and relationship satisfaction. In contrast, the perception of partner disclosure only mediated the association between women’s higher levels of CM and their own sexual satisfaction. Perceived partner responsiveness showed a wider range of actor and partner effects for women and men, explaining the associations between women and men’s higher levels of CM and their own sexual and relationship satisfaction as well as their partners’ relationship satisfaction. As such, CM may trigger weaker perceptions of partner responsiveness, which could act as an important mechanism explaining how the effect of CM is carried forward over time and contributes to shape sexuality and relationships in adulthood.

The role of perceived partner responsiveness in this mediational model is significant because it is the component of intimacy that plays a more important role in the experience of daily intimacy according to Reis and Shaver’s (1988) model of intimacy and to Laurenceau et al.’s (1998, 2005) daily diary studies. For an interaction to be perceived as intimate and influencing satisfaction indicators, individuals need to interpret their partners’ statements as being responsive, accepting, and caring. Simple disclosure, when not followed by an empathic response, is not conducive to increased feelings of closeness. Thus, our results were in line with the interpersonal process model of intimacy whereby individuals reporting CM may generally feel less understood, validated, and cared for, which leaves them feeling less satisfied with their relationship. Lower perceived partner empathy may also explain how individuals reporting CM regulate their sexual feelings and behaviors, leading to lower sexual satisfaction.

Even if CM did not have a direct effect on all components of partner intimacy, it was associated with lower partner relationship satisfaction via the effect on partner responsiveness as perceived by individuals reporting CM. This is in line with theoretical and clinical analyses of the secondary trauma effects of CM on romantic partners (Nelson & Wampler, 2000) and also with past studies reporting lower relationship satisfaction in partners of individuals reporting CM (Corsini-Munt et al., 2017; Whisman, 2014). Our results extended these findings by showing that partners of individuals reporting CM may also struggle with relationship difficulties, but that these issues are partially explained by the perception of partner responsiveness. Even if studies using dyadic models to examine partner effects of a perceived behavior are still scarce, Rosen, Bois, Mayrand, Vannier, and Bergeron (2016) reported that partner perceived empathy is associated with higher relationship adjustment in women coping with genito-pelvic pain. In the context of romantic relationships of individuals reporting CM, the partner’s recurrent feelings that regardless of how he/she is responsive it will be negatively interpreted by the individuals reporting CM may over time affect partner’s self-image and their desire to pursue the relationship, diminishing partner relationship satisfaction.

Limitations and Future Studies

This study moved beyond past intra-individual, cross-sectional studies nonsignificant results concerning the association between CM and intimacy, by using a prospective, dyadic, theoretically based, and multidimensional model of intimacy. Results shed light on possible mechanisms explaining relationship and sexual difficulties of individuals with CM history, reporting that two components of intimacy were highly relevant and explained how CM may limit sexual and relation satisfaction through complex dyadic effects. Despite these strengths, there were some limitations that require consideration.

First, even if the CTQ measure used behaviorally defined questions which are usually accurate (Thombs et al., 2006), there may still be memory biases or distortions in the recall of the events. The CTQ does not provide a clear picture of CM severity, with the total score reflecting only the frequency of the different types of CM and the cumulative experiences of multiple types of CM. Moreover, based on the general effect theory (Higgins & McCabe, 2000) and past empirical research (Bigras et al., 2017), we examined the role of cumulative childhood maltreatment, which gives limited information on the unique or interactive effects of each type of CM. Second, the representativeness of our sample and generalizability of our results may be limited by our convenience sample of couples recruited through advertisements where self-selection biases may occur. Indeed, examination of sexual and relationship satisfaction means suggested that this sample included couples that were generally satisfied with their sexual and relationship functioning. This study only included couples who had been together for at least 6 months. Thus, it is possible that our sample was biased toward higher functioning couples. Participating couples may not be representative of most relationships of individuals reporting CM, as victims may experience difficulties in pursuing long-term relationships (Cherlin, Burton, Hurt, & Purvin, 2004). The effect of CM on the capacity for intimacy in clinical sample of couples with sexual or relationship difficulties awaits additional examination, as does the applicability of our findings to single individuals and same-sex couples. Third, even if this study used a longitudinal design to examine mediation, it remains a correlational study which precludes causal interpretations. An alternative hypothesis may be that in couples with lower relationship satisfaction, individuals reporting CM tend to perceive less empathic responses from their partners. Moreover, although intimacy as well as sexual and relationship satisfaction can change across time, the effect of CM on these patterns of change remains understudied. Thus, studies examining how intimacy and other sexual and relationship indicators may evolve over the course of relationship history in the aftermath of CM are needed.

Clinical Implications

Due to its myriad of long-term effects on sexual and relationship outcomes, childhood maltreatment is an important historical factor to assess in clinical practice where the routine use of a standardized questionnaire or a specific interview should be considered (Rossiter et al., 2015). Findings underscore the importance of considering perception of partners’ behaviors and the partner’s current empathic responses in the evaluation of individuals reporting CM, particularly in couple therapy. These results suggest that couple interventions targeting the enhancement of intimacy may foster relationship and sexual well-being in individuals reporting CM. An intervention might attempt, in a first step, to disentangle what is coming from the inner world of the individuals reporting CM and what is coming from the partner’s difficulties to respond empathically. In a second step, treatment might focus on current intimate interactions, addressing how CM has disrupted the quality of attachment representations, and pave the way to the development of empathic response skills (Buttenheim & Levendosky, 1994; Kardan-Souraki, Hamzehgardeshi, Asadpour, Mohammadpour, & Khani, 2015; MacIntosh, 2017). These foci for treatment interventions may help prevent sexual and relationship difficulties of individuals reporting CM.

References

Bernstein, D., & Fink, L. (1998). Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A retrospective self-report. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

Bernstein, D. P., Fink, L., Handelsman, L., Foote, J., Lovejoy, M., Wenzel, K., … Ruggiero, J. (1994). Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 1132–1136. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132.

Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., … Zule, W. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27, 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0.

Berthelot, N., Godbout, N., Hébert, M., Goulet, M., & Bergeron, S. (2014). Prevalence and correlates of childhood sexual abuse in adults consulting for sexual problems. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 40, 434–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2013.772548.

Bigras, N., Godbout, N., Hébert, M., Runtz, M., & Daspe, M. E. (2015). Identity and relatedness as mediators between child emotional abuse and adult couple adjustment in women. Child Abuse and Neglect, 50, 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.07.009.

Bigras, N., Godbout, N., Hébert, M., & Sabourin, S. (2017). Cumulative adverse childhood experiences and sexual satisfaction in sex therapy patients: What role for symptom complexity? Journal of Sexual Medicine, 14, 444–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.01.013.

Bois, K., Bergeron, S., Rosen, N. O., McDuff, P., & Gregoire, C. (2013). Sexual and relationship intimacy among women with provoked vestibulodynia and their partners: Associations with sexual satisfaction, sexual function, and pain self-efficacy. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10, 2024–2035. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12210.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. Attachment (Vol. 1). New York, NY: Basic Books.

Briere, J. (2002). Treating adult survivors of severe childhood abuse and neglect: Further development of an integrative model. In J. E. B. Myers, L. Berliner, J. Briere, C. T. Hendrix, T. Reid, & C. Jenny (Eds.), The APSAC handbook on child maltreatment (2nd ed., pp. 175–202). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Briere, J., Agee, E., & Dietrich, A. (2016). Cumulative trauma and current posttraumatic stress disorder status in general population and inmate samples. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8, 439–446. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000107.

Briere, J., & Scott, C. (2014). Principles of trauma therapy: A guide to symptoms, evaluation, and treatment (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Buttenheim, M., & Levendosky, A. (1994). Couples treatment for incest survivors. Psychotherapy, 31, 407–414.

Cherlin, A. J., Burton, L. M., Hurt, T. R., & Purvin, D. M. (2004). The influence of physical and sexual abuse on marriage and cohabitation. American Sociological Review, 69, 768–789. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240406900602.

Cole, P. M., & Putnam, F. W. (1992). Effect of incest on self and social functioning: A developmental psychopathological model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 174–183.

Colman, R. A., & Widom, C. S. (2004). Childhood abuse and neglect and adult intimate relationships: A prospective study. Child Abuse and Neglect, 28, 1133–1151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.02.005.

Corsini-Munt, S., Bergeron, S., Rosen, N. O., Beaulieu, N., & Steben, M. (2017). A dyadic perspective on childhood maltreatment for women with provoked vestibulodynia and their partners: Associations with pain and sexual and psychosocial functioning. Journal of Sex Research, 54, 308–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1158229.

Cyr, K., Chamberland, C., Clement, M.-È., Lessard, G., Wemmers, J. A., Collin-Vezina, D., … Damant, D. (2013). Polyvictimization and victimization of children and youth: Results from a populational survey. Child Abuse and Neglect, 37, 814–820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.009.

Davis, J. L., Petretic-Jackson, P. A., & Ting, L. (2001). Intimacy dysfunction and trauma symptomatology: Long-term correlates of different types of child abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 14, 63–79.

DiLillo, D. (2001). Interpersonal functioning among women reporting a history of childhood sexual abuse: Empirical findings and methodological issues. Clinical Psychology Review, 21, 553–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00072-0.

DiLillo, D., Lewis, T., & Loreto-Colgan, A. D. (2007). Child maltreatment history and subsequent romantic relationships. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 15, 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1300/J146v15n01_02.

DiLillo, D., & Long, P. J. (1999). Perceptions of couple functioning among female survivors of child sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 7, 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1300/J070v07n04_05.

DiLillo, D., Peugh, J., Walsh, K., Panuzio, J., Trask, E., & Evans, S. (2009). Child maltreatment history among newlywed couples: A longitudinal study of marital outcomes and mediating pathways. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 680–692. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015708.

Domhardt, M., Munzer, A., Fegert, J. M., & Goldbeck, L. (2015). Resilience in survivors of child sexual abuse: A systematic review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 16, 476–493. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838014557288.

Drapeau, M., & Perry, J. C. (2004). Childhood trauma and adult interpersonal functioning: A study using the Core Conflictual Relationship Theme Method (CCRT). Child Abuse and Neglect, 28, 1049–1066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.05.004.

Fallis, E. E., Rehman, U. S., Woody, E. Z., & Purdon, C. (2016). The longitudinal association of relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction in long-term relationships. Journal of Family Psychology, 30, 822–831. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000205.

Finkelhor, D., & Browne, A. (1985). The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: A conceptualization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 55, 530–541.

Freyd, J., & Birrell, P. (2013). Blind to betrayal: Why we fool ourselves we aren’t being fooled. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Frias, M. T., Brassard, A., & Shaver, P. R. (2014). Childhood sexual abuse and attachment insecurities as predictors of women’s own and perceived-partner extradyadic involvement. Child Abuse and Neglect, 38, 1450–1458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.02.009.

Funk, J. L., & Rogge, R. D. (2007). Testing the ruler with item response theory: Increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the Couples Satisfaction Index. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 572–583. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.572.

Gilbert, R., Spatz Widom, C., Browne, K., Fergusson, D., Webb, E., & Janson, S. (2009). Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet, 373, 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7.

Godbout, N., Dutton, D. G., Lussier, Y., & Sabourin, S. (2009). Early exposure to violence, domestic violence, attachment representations, and marital adjustment. Personal Relationships, 16, 365–384.

Godbout, N., Vaillancourt-Morel, M. P., Bigras, N., Briere, J., Hébert, M., Runtz, M., et al. (2017). Intimate partner violence in male survivors of child maltreatment: A meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838017692382.

Graham, J. M., Diebels, K. J., & Barnow, Z. B. (2011). The reliability of relationship satisfaction: A reliability generalization meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 25, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022441.supp.

Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence from domestic abuse to political terror. New York: Basic Books.

Higgins, D. J., & McCabe, M. P. (2000). Multi-type maltreatment and the long-term adjustment of adults. Child Abuse Review, 9, 6–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0852(200001/02)9:1%3c6:AID-CAR579%3e3.0.CO;2-W.

Kardan-Souraki, M., Hamzehgardeshi, Z., Asadpour, I., Mohammadpour, R. A., & Khani, S. (2015). A review of marital intimacy-enhancing interventions among married individuals. Global Journal of Health Science, 8, 74–93. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v8n8p74.

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Kraemer, H. C., Kiernan, M., Essex, M., & Kupfer, D. J. (2008). How and why criteria defining moderators and mediators differ between the Baron & Kenny and MacArthur approaches. Health Psychology, 27, 101–108. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S101.

Laurenceau, J. P., Barrett, L. F., & Pietromonaco, P. R. (1998). Intimacy as an interpersonal process: The importance of self-disclosure, partner disclosure, and perceived partner responsiveness in interpersonal exchanges. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1238–1251. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1238.

Laurenceau, J. P., Barrett, L. F., & Rovine, M. J. (2005). The interpersonal process model of intimacy in marriage: A daily-diary and multilevel modeling approach. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 314–323. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.314.

Lawrance, K.-A., & Byers, E. S. (1992). Development of the interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction in long-term relationships. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 1, 123–128.

Lawrance, K.-A., & Byers, E. S. (1995). Sexual satisfaction in long-term heterosexual relationships: The interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. Personal Relationships, 2, 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.1995.tb00092.x.

Lawrance, K.-A., & Byers, S. E. (1998). Interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction questionnaire. In C. M. Davis, W. L. Yarber, R. Bauserman, G. Schreer, & S. L. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of sexuality-related measures (pp. 514–515). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Luterek, J. A., Harb, G. C., Heimberg, R. G., & Marx, B. P. (2004). Interpersonal rejection sensitivity in childhood sexual abuse survivors: Mediator of depressive symptoms and anger suppression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19, 90–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260503259052.

MacDonald, K., Thomas, M. L., Sciolla, A. F., Schneider, B., Pappas, K., Bleijenberg, G., … Wingenfeld, K. (2016). Minimization of childhood maltreatment is common and consequential: Results from a large, multinational sample using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. PLOS One, 11, e0146058. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146058.

MacIntosh, H. B. (2017). Dyadic traumatic reenactment: An integration of psychoanalytic approaches to working with negative interaction cycles in couple therapy with childhood sexual abuse survivors. Clinical Social Work Journal, 45, 344–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-016-0607-0.

MacNeil, S., & Byers, E. S. (2005). Dyadic assessment of sexual self-disclosure and sexual satisfaction in heterosexual dating couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22, 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407505050942.

Mullen, P. E., Martin, J. L., Anderson, J. C., Romans, S. E., & Herbison, G. P. (1994). The effect of child sexual abuse on social, interpersonal and sexual function in adult life. British Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.165.1.35.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2015). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Nelson, B. S., & Wampler, K. S. (2000). Systemic effects of trauma in clinic couples: An exploratory study of secondary trauma resulting from childhood abuse. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 26, 171–184.

Paquette, D., Laporte, L., Bigras, M., & Zoccolillo, M. (2004). Validation de la version française du CTQ et prévalence de l’histoire de maltraitance. Santé mentale au Québec, 29, 201–220. https://doi.org/10.7202/008831ar.

Pearlman, L. A. (1997). Trauma and the self. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 1, 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1300/J135v01n01_02.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.40.3.879.

Reis, H. T., & Shaver, P. (1988). Intimacy as an interpersonal process. In S. W. Duck (Ed.), Handbook of personal relationships (pp. 367–389). Chichester: Wiley.

Rellini, A. H. (2008). Review of the empirical evidence for a theoretical model to understand the sexual problems of women with a history of CSA. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5, 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00652.x.

Rellini, A. H., Vujanovic, A. A., Gilbert, M., & Zvolensky, M. J. (2012). Childhood maltreatment and difficulties in emotion regulation: Associations with sexual and relationship satisfaction among young adult women. Journal of Sex Research, 49, 434–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2011.565430.

Rosen, N. O., Bois, K., Mayrand, M.-H., Vannier, S., & Bergeron, S. (2016). Observed and perceived disclosure and empathy are associated with better relationship adjustment and quality of life in couples coping with vulvodynia. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45, 1945–1956. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0739-x.

Rossiter, A., Byrne, F., Wota, A. P., Nisar, Z., Ofuafor, T., Murray, I., … Hallahan, B. (2015). Childhood trauma levels in individuals attending adult mental health services: An evaluation of clinical records and structured measurement of childhood trauma. Child Abuse and Neglect, 44, 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.01.001.

Rubin, H., & Campbell, L. (2012). Day-to-day changes in intimacy predict heightened relationship passion, sexual occurrence, and sexual satisfaction: A dyadic diary analysis. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3, 224–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611416520.

Seehuus, M., Clifton, J., & Rellini, A. H. (2015). The role of family environment and multiple forms of childhood abuse in the shaping of sexual function and satisfaction in women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 1595–1608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0364-5.

Thombs, B. D., Bernstein, D. P., Ziegelstein, R. C., Scher, C. D., Forde, D. R., Walker, E. A., et al. (2006). An evaluation of screening questions for childhood abuse in 2 community samples: Implications for clinical practice. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166, 2020–2026.

Vachon, D. D., Krueger, R. F., Rogosch, F. A., & Cicchetti, D. (2015). Assessment of the harmful psychiatric and behavioral effects of different forms of child maltreatment. JAMA Psychiatry, 72, 1135–1142. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1792.

Vaillancourt-Morel, M.-P., Godbout, N., Labadie, C., Runtz, M., Lussier, Y., & Sabourin, S. (2015). Avoidant and compulsive sexual behaviors in male and female survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect, 40, 48–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.10.024.

van der Kold, B. A. (1989). The compulsion to repeat the trauma: Re-enactment, revictimization, and masochism. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 12, 389–411.

Whisman, M. A. (2006). Childhood trauma and marital outcomes in adulthood. Personal Relationships, 13, 375–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2006.00124.x.

Whisman, M. A. (2014). Dyadic perspectives on trauma and marital quality. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6, 207–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036143.

Whisman, M. A., Dixon, A. E., & Johnson, D. (1997). Therapists’ perspectives of couple problems and treatment issues in couple therapy. Journal of Family Psychology, 11, 361–366. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.11.3.361.

Yoo, H., Bartle-Haring, S., Day, R. D., & Gangamma, R. (2014). Couple communication, emotional and sexual intimacy, and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 40, 275–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2012.751072.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Laurence de Montigny Gauthier and Mylène Desrosiers for their assistance with data collection.

Funding

This study was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) to Marie-Pier Vaillancourt-Morel and by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to Sophie Bergeron.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vaillancourt-Morel, MP., Rellini, A.H., Godbout, N. et al. Intimacy Mediates the Relation Between Maltreatment in Childhood and Sexual and Relationship Satisfaction in Adulthood: A Dyadic Longitudinal Analysis. Arch Sex Behav 48, 803–814 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1309-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1309-1