Abstract

This paper studies the effect of changes in the return to human capital on the fertility–education relationship. The setting is in Anhui Province, China in the thirteenth to twentieth centuries. Over this period, key changes occurred in the civil service examination system, providing a means to test whether incentives for acquiring education influenced fertility decisions. I form an intergenerationally linked dataset from over 43,000 individuals from all social strata to examine the evidence for a child quantity–quality tradeoff. First, as the civil service examination system became more predictable and less discretionary starting in the seventeenth century, raising the return to human capital, I find evidence that households with a lower number of children had a higher chance that one of their sons would participate in the state examinations. This finding is robust to accounting for differences in resources, health, parental human capital, and demographic characteristics. Importantly, the finding is not limited to a small subset of rich households but present in the sample as a whole. Second, the negative relationship between fertility and education disappeared as the lower chance to become an official during the nineteenth century implied a decline in the return to human capital. Taken together, my findings support the hypothesis that fertility choices respond to changes in the return to human capital.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The historical development of countries around the world shows that sustained increases in per-capita income coincide with increasing skills and education per worker. Human capital is seen as one the most important determinants of economic development in the growth experience of the United States, Britain, as well as other countries (Crafts 1995; DeLong et al. 2003; Galor and Weil 2000; Galor and Moav 2002). Today, the World Bank spends $11.1 billion on education-related projects in 71 developing countries.Footnote 1 The consequences of this policy for per-capita income pivot on the relationship between the education of each child (human capital) and the number of children (fertility). This paper examines whether the fertility–human capital relationship responds to economic incentives.Footnote 2

Specifically, I examine the extent to which families responded to incentives to invest in human capital in a sample of over 43,000 individuals in central China between the years 1300 and 1900. A simple model along the lines of Galor and Weil (2000) and Galor and Moav (2002) predicts that the choice between fertility and education depends on their relative returns. Consistent with changes instituted by the government in incentives to acquire human capital in China, I find a robust negative relationship between education and fertility in the seventeenth century in China. However, within the following two centuries, the decline in the return to education was accompanied by the disappearance of the quantity–quality relationship. The increase and subsequent decrease in demand for child quality supports the hypothesis that economic factors determined the relationship between fertility and education in pre-industrial China.

The Qing State (1644–1911) used the civil service examinations as an entry mechanism to determine who could hold office, and enforced uniformity on the system. A priori, we might expect that this helped to raise the incentives to invest in human capital. The examination consisted of a series of written tests that demanded advanced literary skills and a sophisticated knowledge of an extensive curriculum requiring many years of study in order to master. Although civil service examinations were used already in the Song dynasty (960–1127), throughout the history of the civil service examination system, personal recommendation and discretionary routes of advancements co-existed with it. Even during the Ming era (1368–1644), it was not uncommon for office seekers to purchase a degree or title.

It was not until the seventeenth century, with the reign of the first Qing emperor Shun-zhi (1644–1661), that the role of these non-examination channels was substantially reduced. One reason why the Qing shifted away from the previous, more discretionary channels for entering officialdom may have been that the Qing Manchu emperors sought to establish greater legitimacy of rule over local (sub-provincial) sources of power based on local lineage organization.Footnote 3 It may have been a mutually advantageous political development.Footnote 4 Most educated and wealthy local families tried to enter officialdom by competing in the examination system, and once appointed in official positions, these local elites became invested in promoting the political agenda of the Qing state within the local community.

Against this institutional backdrop of examination competition, from the seventeenth century to the nineteenth century, growth in China’s population averaged 1% a year. The number of official positions for magistrates and prefects, by contrast, remained roughly the same due to the consolidation of counties as the population increased. More importantly, the increase in population relative to the unchanging number of official positions available meant that the degree of competition in the exams increased dramatically (Ho 1962; Elman 2002; Miyazaki 1976). What has not been so far examined is whether this, in turn, led to a decline in the expected return to education, as we might expect if the historical record is correct.

In this paper, I contribute to the literature by providing evidence that fertility responded to economic incentives: namely, that incentives to acquire human capital, as defined by whether a man participates in the examinations, produced a significant negative relationship with the size of the family in which he was raised. The results imply that at the start of the Qing—from the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries—among the elite families in which both the father and grandfather were educated, an additional brother is associated with a fall in the probability of investing in human capital of 4%. As roughly one-third of the sons in these elite families participated in the examinations (so that quite substantial investments in human capital were made in these cases), an additional brother means roughly a 12% decline in human capital investment \((0.04/0.34 = 12\%)\). The relationship is negative and significant not only for these individuals, but also for those who had neither an educated father nor grandfather, thus demonstrating that the quantity–quality relationship was not confined to elite groups but applied to a large social spectrum.

This negative relationship between fertility and education during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries by itself does not imply that households chose the number of children in response to education goals. Fertility differences could be determined by resource differences, health shocks, or famines, for example, and given variation in the number of children a negative quantity–quality relationship could be the result of a resource constraint—child quantity crowds out quality. This concern is addressed in two ways. First, I use information on a range of resource, health, demographic, and aggregate factors, showing that the negative relationship between fertility and education remains present even after plausible determinants of fertility other than parental choice have been controlled for. Second, and more importantly, in the temporal analysis I show changes in the quantity–quality relationship. After the early nineteenth century, the disappearance of the negative child quantity–quality relationship in China becomes apparent and is consistent with the decline in the return to education.

The implication is striking especially since demographers have traditionally stressed early and universal marriage for women in China, as well as large families for rich men, and strong son preference.Footnote 5 Other authors have debated whether fertility control occurred. By shifting the focus from demographic patterns to the link between human capital and fertility, my work sheds new light on a mechanism central to economic development in the historic context, and provides the first empirical study of whether parents chose to forego sons, as would be implied in a quantity–quality calculation. Furthermore, although the cultural and historical emphasis on education embodied in the civil service examinations is well known, we do not know whether economic incentives for human capital investments mattered enough to affect fertility behavior. By analyzing several centuries, I am able to show not only that a negative child-quantity quality relationship existed, but also that the strength of the relationship changed in ways that are consistent with what is known about long-term changes in the economic incentive to become highly educated in China.

Fertility decline has been depicted as arising after the onset of modern growth around 1800, and linked to changes in child mortality, demand for children, women’s work, public schooling, child labor, and other factors (Doepke 2004; Lee 2003; Easterlin and Crimmins 1985; Guinnane 2011 provides an overview).Footnote 6 Studies on the fertility–education relationship have frequently focused on increases in the return to human capital and the associated fertility decline. For example, Bleakley and Lange (2009) find that the eradication of the hookworm raised the return to human capital in the early twentieth century American South, while Vogl (2016) considers rising returns to investment in children in 48 countries in the later twentieth century and how this may have lowered the income threshold at which families begin to invest.Footnote 7 In contrast, this paper sheds light on the fertility–education relationship in the late Qing economy when the return to human capital decreases (and fertility increases).

Also in counterpoint to Western developments, during my sample period China was a pre-industrial economy experiencing few of the social and institutional developments often associated with industrialization and fertility decline in the Western experience. In this context, my findings for early-Qing China demonstrate that the quantity–quality tradeoff is not a modern phenomenon. A relatively high demand for human capital is critical for the quantity–quantity tradeoff to emerge, though it may not lead to modern economic growth. The higher human capital returns triggered by changes in the civil service examinations along with the subsequent weakening of incentives in China fits into the overall history of increasing population and growth divergence between China and Western Europe during the late eighteenth to nineteenth centuries (the ‘Great divergence’, Pomeranz 2000). The effect would likely have been reinforced by declines in the state’s per-capita tax revenues that could have lowered the returns of being a state official. By focusing on domestic reasons for a lower human capital return this paper complements research showing that international trade in the twentieth century has lowered the human capital returns in many non-OECD countries (Galor and Mountford 2008).

Because aggregate-level data masks important heterogeneity determining historical human capital–fertility relationships (Guinnane 2011), together with a recent but rapidly expanding literature I employ more disaggregated data.Footnote 8 Becker et al. (2010, 2012), in particular, use detailed county-level data to show that a fertility–education trade-off existed in nineteenth century Prussia. I extend this literature by exploiting variation across intergenerationally linked households over a long sample period, which is key to observing long-term changes in the return to education.

Finally, this paper contributes to the literature employing Chinese genealogies (Liu 1978, 1980; Fei and Liu 1982; Telford 1986). Although genealogies have certain limitations compared to contemporary high-income country census data, the possibility of linking multiple generations is a key advantage, especially on questions where long-run dynamics could be important, such as the intergenerational transmission of human capital (discussed below in Sect. 4.1). Most of the existing work to date employing genealogies focuses on questions in demography (Harrell 1987; Telford 1990; Zhao 1994); by examining the relationship between fertility and education, this paper sheds new light on the potential of using genealogies for studying economic questions.

2 The Ming–Qing educational system and state sponsored civil-service examinations

2.1 Eligibility and scope: from discretion to rules

The civil service examination system was an institution that was shaped over a long period of time that spanned many centuries.Footnote 9 Early on, from the Tang Dynasty (670–906) to the Northern Song Dynasty (960–1126), even though literacy and knowledge of the classic texts were prerequisites for appointment to government office the selection process was a simpler process. Most appointees were made on the basis of discretionary official recommendations and kinship relationships among a highly constrained pool of candidates who resided near the capital (see Teng 1967, pp. 25–49; Elman 1991). In addition, up until the end of the Southern Song Dynasty, circa 1279, artisans and merchant families were not legally eligible to participate in state examinations because of sumptuary laws (Ho 1962, p. 41).

After the Song, examinations and discretionary appointment existed side-by-side, and examinations were effectively used in conjunction with ad hoc appointments of officials up to the Ming (1368–1644). A series of decrees, starting in the Ming dynasty, formally permitted men without academic degrees to purchase their way towards appointment to high-level offices (Ho 1962, pp. 32–33). According to Ho (1962): “All the way down to the end of the Ming period chien-sheng (holders of a purchased degree) were legally and institutionally entitled” to government office. Between the years 1406 and 1574, more than half of the high-level candidates that had obtained their office from these unorthodox or irregular channels had purchased degrees.

Under circumstances where wealth could be converted into high-status positions through purchased degrees and discretionary means, or when the return to education is unpredictable or low, we would not expect to find much incentives to investment in child education. One example is the 14 years lapse that occurred between the administrations of two national civil service examinations in the fourteenth century under Ming rule.Footnote 10 Not only would such a large gap between when the two examinations were held have discouraged potential candidates from investing in the education needed for these exams, but it also suggests that the early Ming state did not depend on routine national exams for recruiting officials.

In addition, through at least the late sixteenth century, there were no effective limitations on the number of new licensing degrees awarded each year in the larger counties (Ho 1962, p. 178). The effect was the number of degrees awarded fluctuated sharply across different regions, depending on the discretionary power of the local education commissioner to influence the number of awards. There were also strong overall increases in the numbers of degrees held in the early seventeenth century that was attributable to increased sales of titles (ibid p. 178).Footnote 11 The variations suggest that degree standards were relatively unpredictable across regions and over time, which would have made it more difficult to plan investments in exam preparation.

It was not until the mid-seventeenth century that renewed efforts to overhaul the system made the returns to education more predictable. The changes were not all made at once, but the cumulative effect was such that by the end of the reign of the first Qing emperor in 1661, the civil service examination system was quite different from what it had been up to that time in essentially important ways (Elman 1994).

Several changes were crucial.Footnote 12 First, examinations were held at regular intervals in provinces throughout the Qing Empire. The Qing state held the provincial examinations in the provincial capital every 3 years over a period of 9 days.Footnote 13 Supporting measures were introduced. For instance, national examination areas were supervised closely to prevent cheating, and the candidates’ names were removed from the test before the answers were graded and ranked to prevent favoritism. Exam questions were based on the moral and political thinking of classicism, and required candidates to compose poems and essays—the content reflected what was generally considered to be the essential abilities of a learned person. The exams were not exclusively humanist, containing also policy questions on statecraft, fiscal policy, as well as military and political institutions at the time.Footnote 14

Second, the discretionary fluctuations in the awarding of new degrees seen in the late Ming were stabilized in the seventeenth century when the first Qing emperor Shun-zhi (1644–1661) issued a decree that reset quotas for each prefectural city and county insofar as the number of new licensing degrees that could be issued at each examination.Footnote 15 Unlike the Ming state, the Qing government enforced the upper limits of new degrees issued, especially at the basic entry level, or the licensing level (the sheng-yuan degree). Since only people with a licensing degree obtained through written exams could be considered for the upper-level examinations, much like a tournament, the enforcement of lower level quotas thereby reinforced education rather than discretion in the system (Ho 1962, p. 182). Variations in the number of sheng-yuan degrees during the first two centuries of the Qing period were minor compared to the Ming (Ho 1962, p. 179).Footnote 16 Third, complementing these changes, Qing rulers closed down on other means for the majority population of Han Chinese to enter officialdom. Discretionary appointments declined sharply and purchased degrees effectively became vanity titles that did not confer the same political power and elite status as the degrees that required the passing of the difficult written examination.Footnote 17

The result of the changes was that the civil service examinations became a well-defined and predictable gateway allowing entry into government office. These changes were in evidence in the early Qing and should have increased incentives to invest in education.

2.2 Costs of education

There were major differences between basic literacy training and investments in civil service. While the state established the content and curriculum for the official examinations, mandatory public education did not exist at any level through the period under study.Footnote 18 Anecdotal accounts of teacher salaries, however, suggest the costs of schooling to attain basic literacy during the Qing period were modest.Footnote 19

By contrast, a great deal of time and effort was required to prepare for the imperial examinations, which required the memorization of vast tracts of literary and historical material and the ability to compose highly stylized texts. The decision of whether or not to groom a son for civil service was a private investment decision. Formal education started early because of the large number of characters that had to be memorized. For boys, schooling likely began at the age of 5, often first with their mother and then with hired tutors (Elman 1991, pp. 16–17; Miyazaki 1976). Although women were barred from state service, upper-class girls also received lessons and were literate.

Since schooling was neither mandatory nor regulated, a wide variety of schools could be found, with some kind of school present in most villages and urban centers (Rawski 1979, p. 17; Leung 1994).Footnote 20 Evidence of the costs of higher education can be seen in the private academies established in the eighteenth century, which allowed teaching and classical research to be alternative careers to high paid government appointment. Unlike teachers for youngsters, these teachers might have been men who were previously successful examination candidates with degrees; some may have been retired officials who had returned home after their civil service career.

There were three major stages of the state examinations. The licentiate degree (sheng-yuan) was a lower level title given to men who passed an initial exam at the local (prefectural or county) level; literate men were nominated for candidacy to this first level. Candidates as young as 15–16 years old were known to pass these licensing examinations, but most were in their twenties (Elman 2000, p. 263). Estimates place the number of licentiates in the nation in 1700 at 500,000 (perhaps 0.3% of the population).

Those who succeeded were eligible to go on to the intermediate stage. An intermediate degree (at the provincial level) was known as the ju-ren; it was significant from a returns-to-human capital standpoint because it would allow the individual to be appointed to (a minor) office. It was necessary also for a chance to take the national examination given every 3 years. The jin-shi degree was the highest national degree awarded, and these degree-holders were entitled to the highest ranked positions in government.Footnote 21

Attempting to pass in the civil service examination was a costly venture. The fee alone for taking the national examinations was already a large sum. Miyazaki (1976, p. 118) estimated it was around 833 silver dollars in the sixteenth century, when the literati (those who were literate in the classics and therefore could enter teaching careers) might have earned an average annual income of 778 silver dollars plus room and board in the nineteenth century (Elman 2002, p. 403). Undoubtedly, the sons of the upper-class families had more opportunities and resources to obtain the schooling or tutoring for their exam preparation. However, unlike purchased degrees, obtaining examination degrees depended on individual performance and the extent of competition. Even if wealthy families could greatly increase the odds of success of the next generation, they could not guarantee success. This was underscored by the fact that the number of candidates greatly outpaced the number of degrees awarded and not all wealthy families produced sons that passed the exams. In addition, since the system did not bar non-elite families from the examinations, especially gifted boys who were funded by a wealthy benefactor could rise in a rags-to-riches way through the ranks. Although they were few in number, there were men of legendary brilliance who did so (Elman 2000, p. 263).

2.3 Returns to education

At the conclusion of the national exams, a list of the successful candidates was produced, in rank order. A high official position in the government offered some of the most financially rewarding careers available, and the prestige and power that came with such positions was unmatched (Elman 2000, p. 292; Chang 1962, p. 3). Merchants who had accumulated fortunes could on occasion purchase minor titles and thus buy into some part of the governing elite, but merchants also funded private academies to educate their sons for the reason that passing the examinations was the way to gain the ultimate prize.

The annual salary of the head of the province (the governor-general) in the eighteenth century, plus the expected official bonuses, informal gifts, and grain easily surpassed the value of 250,000 silver dollars. For the head administrator of the county (the district magistrate), the sum of informal bonuses and gifts alone would have amounted to about 45,500 silver dollars per year (Wakeman 1975, pp. 26–27).Footnote 22 Far more important than official salary was the extra income that came with the office, which was a legitimate revenue stream that was attached to the office.Footnote 23 Although these figures are not systematically available, the records that do exist for these payments demonstrate that they were considerable. The extra income for a Grand Secretary was approximately 52,500 taels annually, for example; and that for a Vice-President of one of the Boards was about 30,000 taels (Chang 1962, Table 16). The official portion of the salary, then, is a small fraction—about 0.3 and 0.5%, respectively—of the total income that these officials commanded.

In summary, since the state did not interfere with decisions on household investment activities or the number of children families should have, economic investments into education were almost entirely borne by the families or benefactors of potential candidates. Although children could not directly inherit official positions and titles, earned income could be passed on to descendants because of an economic environment of generally secure property rights combined with low taxation during the period under study. The usefulness of the knowledge that was tested in these exams from our current perspective is a subject worthy of study in its own right (e.g. Yuchtman 2017). For the purposes of this paper—what is important is that the material required years of study and the human capital investments were not small.

2.4 The incentives to acquire human capital over time

During the seventeenth century, the Qing state started to set up a non-discretionary and merit-based state examination system. In this section, I show that subsequent changes in the nineteenth century likely reduced the incentives to acquire human capital. The incentive to accumulate human capital depends on the expected return to human capital, net of the costs.Footnote 24 Here, the return to educational investments depended in large part on the likelihood of being successfully in obtaining an appointment to one of the coveted official positions. As described above, the pool of candidates eligible to participate in the examinations expanded from an institutional standpoint, and additionally, there was also significant growth in the size of China’s population over this period, from about 145 million in 1700 to about 425 million by the late Qing.Footnote 25

Despite the strong increase in population, the number of high-ranking official positions was based on the number of county seats, and this was nearly static: 1385 in Ming and 1360 in Qing. As a consequence, the ratio of official positions relative to both the size of the population and the number of eligible candidates fell. The resulting increase in competition placed strong downward pressure on the odds of being successful in the examinations, thus reducing the expected return to human capital.Footnote 26

The change in the officials’ lifestyle and spending patterns, based on information from biographies, lineage genealogies, as well as local histories (gazetteers), is consistent with a decline in the return to human capital over the Qing era. For example, in the eighteenth century a single retired official, Chiang Chi, spent 300,000 taels on constructing roads around his native place, after having served for 10 years as official on the Board of Punishment. In contrast, comparably high sums for the nineteenth century are much less common (Chang 1962).

Another way to assess the return to human capital is to examine the amount of income derived from teaching. Men who passed the lower level exams but repeatedly failed to pass the intermediate or higher exams could not obtain an official position—many of these individuals resorted to a livelihood as a schoolteacher. Towards the end of the Qing, the income from teaching was reportedly so low that in some cases teachers could not sustain themselves with it, forcing them to take up other tasks (Chang 1962, pp. 252–254; Ho 1962, p. 140). Consistent with this, teachers’ real wages were lower in the nineteenth century compared to the earlier Qing period (see Rawski 1979, Fig. 1).

This is consistent with the downward trend in government stipends that were given to the students who were preparing for the civil service examinations. During the Ming dynasty, students received generous allowances in the form of food (two bushels of rice), cotton and silk cloth, embroidered silk cloth, as well as sets of clothing, headgear, and boots, and travel money to go home to visit family. They were also given holiday money, money to help pay for their wedding, grain to support their wives and children, and other goods (Ho 1962). In contrast, during the Qing students received only a minimal grain stipend and tax exemptions from the state (Cong 2007).

Additional evidence for the decline in the return to human capital comes from data on private academies, which during the Qing were primarily concerned with preparing students for the state examinations (Ho 1962, p. 200). Over the period from 1662 to 1795 there were about 20 academies per one million of Guangdong’s population, whereas during the period from 1796 to 1908 this ratio fell to 8 academies per one million people, less than half the earlier figure.Footnote 27 To the extent that this decline in the expansion of preparatory schools for the state examinations reflects a lower demand for human capital, it is consistent with a decline in the return to human capital.

Overall, multiple indicators provide support for the hypothesis that the return to human capital, as defined by the curriculum of the civil service, fell towards the later part of the Qing era. To the extent that this decline led to lower levels of human capital in the population, this trend is evident in my sample. Between 1661 and 1700, more than 14% of the married men are educated, followed by 6.5% between 1700 and 1750, 5.1% between 1750 and 1800, and 3.9% after the year 1800.

3 Theoretical framework and testable implications

The relationship between child quantity and quality is determined by the utility-maximizing choice of households. Human capital formation will be affected by changes in the costs and benefits of child quantity versus quality. Let there be a household that derives utility u from consumption c, the number of (surviving) children n, as well as from the quality (human capital) h of those children. As in Galor and Weil (2000), and Galor and Moav (2002), I assume that households maximize a log-linear utility function of the following form:

where \(\gamma , 0< \gamma < 1\), and \(b, b < 1\), are constant parameters. Expenditure is divided between the share spent on consumption goods, \((1 -\gamma )\), and the share spent on children, \(\gamma \). The parameter b gives the preference for child quality. The household cares about human capital both because of the potential future revenue stream (in particular, if the child passes the government exam and obtains an official position) and for intrinsic reasons.

For each child, parents spend a fraction \(\tau ^{q}\) of their time budget (and a corresponding share of their potential income) on raising children. Furthermore, a fraction \(\tau ^{e}\) of parents’ time is required for each unit of education of each child. The costs for raising one child with education e thus are \(\tau ^{q}+\tau ^{e}e\) units of time. Assuming that the potential income of the household working full-time is y, the household faces the following budget constraint:

where the price of a child is the opportunity cost associated with raising it, \(y\left( {\tau ^{q}+\tau ^{e}e} \right) .\) Equation (2) confirms that both child quantity and child quality come at the expense of a lower consumption of goods.

Suppose that the level of human capital of each child, h, is an increasing, strictly concave function of the parental time investment in the education of the child, \(e: h=h(e)\). Optimization yields

and

where \(n^{*}\) and \(e^{*}\) denote the optimal choice of child quantity and quality, respectively. The central result of the model for present purposes is Eq. (3), which shows that the household’s choice implies that optimal child quantity \((n^{*})\) and optimal child quality \((e^{*})\) are inversely related. Versions of this equilibrium relationship will be estimated below (after rearranging so that \(e^{*}\) is on the left side). Equation (4) gives the optimal demand for child quality as a function of model parameters. It can be shown that the return to education varies inversely with \(\tau ^{e}\) because parents who do not spend time educating their offspring will produce with any w units of time w units of consumption goods. Furthermore, the optimal level of child quality increases as \(\tau ^{e}\) falls, and vice versa.

This model yields the following predictions for my analysis: first, the cumulative changes up to the seventeenth century made in the state examination system (as described above) can be interpreted as an increase in the expected return to human capital accumulation (lower \(\tau ^{e})\). Second, the decline in the expected return to human capital accumulation from the Early to the Late Qing (higher \(\tau ^{e})\), as discussed above, will decrease the optimal level of human capital investment (and thus lead to higher fertility).

This simple model can accommodate a number of extensions without changing the key prediction. First, differences in the productivity of the education process over time can be captured as follows. Let ln\((h)=\delta ^{t}\) ln\((e), 0<\updelta ^{t} < 1\), where t indexes a certain era, \(t = { early}\) or \(t = { late}\). If \(\updelta ^{\mathrm{early}} > \updelta ^{\mathrm{late}}\), a decline over time has the same qualitative implications as a decline in the return to education: it reduces child quality.Footnote 28 See also Moav (2005) on the case where individuals’ productivity as teachers increases with their own human capital while their productivity in raising children is not affected by their human capital levels. Second, the model assumes that all household investments in child education are in terms of time. As noted above, mothers often spent time on educating their sons. If households could also purchase education services at price \(p^{e}\) (by hiring tutors), this would provide a reason why richer households acquire more education for their children. Nevertheless, as long as households need to spend some part of their time on child education, such as the time needed for the selection and monitoring of tutors, the model’s prediction remains qualitatively unchanged.

4 Data

The data of this paper comes from genealogies of individuals and households who lived in Tongcheng County of Anhui Province.Footnote 29 Tongcheng County is approximately 30 miles by 60 miles, and is situated on the Yangzi River about 300 miles inland from the coast of the East China Sea. The county is about 150 miles from Nanjing, the early Ming Dynasty capital, and 650 miles from Beijing, the later Ming and Qing capital. Anhui Province was representative of the more developed and densely settled regions of China, with Tongcheng considered an important economic region in the relatively developed agricultural economies of the lower Yangzi (Shiue, 2002). The region was mainly a rice-producing area where some of the wealthiest families were landowners (Beattie 1979, pp. 130–131). Over the Ming and Qing Dynasties, the region gained some fame for having produced a number of the highest officials of the empire.

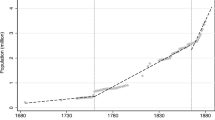

The dataset is created from genealogies of seven lineages (or clans). Typically, genealogies start with the progenitor, the person who first settled in the county and who later descendants consider to be their common ancestor. The earliest date of birth observed in my sample is in the year 1298, with an average coverage of 18 consecutive generations and a maximum of 21. The latest death recorded in my data set is 1925. Generally, the coverage of genealogies at the turn of the twentieth century becomes patchy (e.g., Harrell 1987). The Tongcheng genealogies span the years 1300–1880 (Telford 1990, p. 124), which is by the standards of most micro data an extraordinarily long period.Footnote 30 While my sample covers part of the Yuan and the Ming dynasties, as shown in Fig. 1 the large majority of observations are for the Qing.

4.1 Chinese genealogies as source for research

Given their purpose and method of collection, genealogies are different from census data, official population registers, and other administrative data.Footnote 31 Census data typically record the observed population at a certain date, either at the time of registration or in retrospect. One would need repeated observations throughout the lifetime of the same individual in order to determine the highest education level of that person or household. By contrast, Chinese genealogical data follows the male line of descent and presents one entry per person in biographical format. Genealogies cover men (and boys) better than women (and girls), being organized patrilineally–each male member of the lineage is a member. Furthermore, in terms of vital statistics genealogies cover birth better than death.

Genealogies give a window to examine questions that are hard to address otherwise, in China or elsewhere. The usefulness of genealogies for research depends on the questions asked. One important distinction is whether or not the primary goal of the research is to assess the entire population, with birth rates, death rates, and fertility rates derived from it. In particular, underreporting matters if the main goal is to estimate population totals. My interest is to see whether in a particular sample the relationship between education and fertility evolved over time.

The Tongcheng genealogies are an extraordinarily strong source in this genre (Telford 1986, 1990; Harrell 1987). This is the result of both the high-quality original material and also of the work that researchers have done to improve the original source. For example, in the original Tongcheng records, the year and month of the death for males is missing in only 19% of the cases (Telford 1990, p. 124) while the typical figure is around 50% (Harrell 1987, p. 76). Subsequently, the Tongcheng data has been enhanced by the estimation of vital dates using life tables and other well-known methods (see Telford 1990).Footnote 32 I have taken another step at improving this data by eliminating a number of clerical and otherwise obvious errors.

4.2 Sources of information in the Tongcheng data

Generally, genealogies provide information on male lineage members, their wives, and their children. One can link the data across generations simply by tracing sons as they reappear in the genealogies as adult men. The unit of observation in my analysis is the household, defined by the male head of the household. The nuclear household of parents and children is often embedded in a broader family structure reflecting lineage ties.Footnote 33

Based on the biographical entry for the lifetime of each individual, I distinguish men who have acquired substantial amounts of human capital from those who have not; see column 1 of Table 1. \({ Education} = 1\) if the man has passed one or more levels of official state examinations. Official students (preparing for licentiate status), civil service licentiates (sheng-yuan; preparing for the higher level exams), as well as men who prepared for (but failed) the examinations, are all considered educated and coded with 1 for Education.Footnote 34 Others are given a 0 for Education and are considered not educated (top part of Table 1).

Although licentiates, as well as those who prepared for the exams but failed, were not eligible for office, these men and their families would certainly have already made considerable investments in their education. The number of men in this group was large and included the 1–2 million men who sat for the licensing examinations every other year across the empire; we know they must have been educated because they already had to have passed a series of pre-qualifying tests in their districts. Since I am mainly interested in the household investment aspect, and not just the outcome, I consider these men as being educated because they invested in education. Including only the men who succeeded in passing the examinations would not adequately capture the relationship between child quantity and quality. At the same time, for the baseline analysis I separate human capital from non-human capital investments even though the latter might matter for family size too.Footnote 35

The size of my sample is \(\hbox {n} = 8893\) men, see Table 2. All of these men have survived childhood and have married.Footnote 36 Together with their wives, sons, and daughters, there are about 43,000 individuals listed in the Tongcheng genealogies, or roughly 1.5% of the population of Tongcheng around the year 1790.Footnote 37 Central to my analysis is the relationship between human capital and family size. Table 2 shows that for 6.3% of these men there is evidence of substantial levels of human capital (\({ Education} = 1\), first row), while the average number of brothers, as the measure of family size, was 3.3.Footnote 38

Figure 2 shows that fertility rates in this sample, defined as the average number of male births per woman per year, have the expected shape, dropping off with age and reaching virtually zero by age 45–49.Footnote 39 While the date of marriage is unknown, the difference between the birth year of the wife and the birth year of her first recorded child indicates a relatively early marriage age for women in the sample. On average, the mother’s age at birth is about 28 years. Both the relatively early marriage age and the age-specific fertility patterns are broadly consistent with other sources and what we would expect to be true biologically about fertility and age (Shryock and Siegel 1973).Footnote 40 The average number of total siblings, boys and girls, is about 4.85 in my sample. My analysis will take into account the number of female siblings as well as whether a man had multiple wives.

Table 2 shows the size of my sample during different dynasties. Seven percent of the men live during Yuan and Ming times, just over 55% during the early Qing (defined as years 1644–1800), and 38% during the late Qing (defined as post-1800) years. Notice that from the Early to the late Qing the average level of education decreases (6.7–3.9%) whereas the average number of brothers increases (3.3–3.4). While these trends do not account for other factors they are consistent with a change in the fertility–education relationship over time.

Table 9 in the appendix shows summary statistics across the seven lineages in my sample, the Chen, Ma, Wang, Ye, Yin, Zhao, and Zhou. The largest lineage in my data is the Wang, with about 4700 married men, followed by the Ye with around 1600 men. While in many dimensions the differences across lineages are relatively small, they are different in terms of the average level of human capital. In particular, the Ma lineage is exceptionally well educated, with one-third of the married adult men having extensive human capital, in the sense of Education equal to 1.

In addition, I report summary statistics separately by education level in Table 3. Educated men tend to be recorded earlier than not educated men, with mean birth years of 1728 and 1766, respectively, reflecting temporal trends. In contrast, we would not expect the month of birth to differ between educated and non-educated men, and the table shows there is no evidence that they do. Educated men, however, live longer and have a larger number of wives than not educated men (third and fourth columns, respectively). Furthermore, educated men have a higher number of siblings than not educated men as well as more educated fathers. These are signs of resource and health differences across households. The number of male siblings for educated men tends to be smaller than for not educated men. This is consistent with a quality–quantity trade-off.

On average, the difference in the number of brothers for educated and non-educated men is about 0.2 (see Table 3), and about 0.3 when we match on observable individual characteristics (see Table 7, Panel B). Note also that women of the Ma lineage have comparatively low fertility rates when aged 20–30 years, while women of the Chen and Zhao lineages have comparatively high fertility when they are around 20 and 30 years old, respectively. Given that the Ma lineage is highly educated while the Chen and the Zhao lineages are the two least-educated lineages (see Table 9), this pattern is also consistent with a deliberate choice of quality versus quantity. Temporal trends provide another source of variation. Table 4 shows differences in fertility relative to education for the Qing versus the Yuan–Ming era.

4.3 The Tongcheng sample compared with other evidence

The most systematic evidence on education in China during the Ming–Qing is related to the state examinations. In particular, the number of licentiates (sheng-yuan), individuals that passed the initial state examination, was about 500,000 in the year 1700 (Elman 2000), or roughly 0.3% of the population. In the Tongcheng sample, about 0.76% of the men alive around 1700 were licentiates. Accounting for women, children, and the elderly indicates that the fraction of licentiates in Tongcheng was similar, or perhaps somewhat lower, than that in China as a whole.

Moving up in terms of human capital to the highest degree holders (jin-shi), in his seminal study on China-wide mobility, Ho (1962) reports that during the Qing in Anhui Province there were 41 jin-shi per one million population, or, 0.0041%. The province of Anhui, it should be noted, was below the provincial average in terms of jin-shi per capita in Qing China (Ho 1962, p. 228). In comparison, Tongcheng County in Anhui had 14 jin-shi during the Qing as per my sample, which comes to about 0.045% of the population.Footnote 41 Thus, there are about ten times more jin-shi in the Tongcheng sample than in Qing Anhui overall.

While this suggests that Tongcheng had higher levels of education than Anhui’s population on average, jin-shi were very rare, with many parts of Anhui not producing a single jin-shi over centuries. The strong influence of aggregation in these comparisons becomes clear when noting that a single prefecture could have as many as 1004 jin-shi during the Qing (Ho 1962, p. 247). With seven counties to a prefecture, this means that the average county of that prefecture had \(1004/7 = 143\) jin-shi during the Qing, or an order of magnitude higher than the number of jin-shi in Tongcheng county. Overall, although the number of men with the highest levels of human capital in Tongcheng was higher than in the local surrounding area, Tongcheng was not among the top human capital areas in China; rather, it was noteworthy at a local, perhaps provincial, level.

Moreover, variation in jin-shi across lineages in the Tongcheng sample dwarfs the difference between the sample variation in jin-shi and what we know about the population. At the top of the list, the Ma lineage had 9 jin-shi relative to 627 men, a ratio of 1.4%, whereas other lineages in my sample do not have a single jin-shi. As a consequence, variation across lineages can be used to assess the influence of status and sample composition on the results.

In sum, in terms of many characteristics potentially affecting the relationship between fertility and education, the Tongcheng sample is quite similar to what we know about China from other sources, and to the extent that there are differences they can be explained to a substantial degree by observable factors. Further discussion on various forms of sample selection can be found in Shiue (2016). Overall, these findings indicate that the Tongcheng sample should be informative for studying the fertility–education relationship in China.

5 Empirical results

5.1 The fertility–human capital relationship from the Yuan–Ming to the Qing period

The historical evidence provided in Sect. 2 supports the view of the state examination system becoming more consistent at the Qing Dynasty, compared to the early Ming era. While no single change might have been decisive, cumulatively, the evolution of the examination system within the context of late imperial society meant that human capital accumulation provided a path for upward mobility. The difference in the relationship between human capital and fertility between the Yuan–Ming and the Qing eras is summarized in Table 4. We see that men without education had on average 2.7 brothers during the Yuan–Ming while educated men typically had about 3.1 brothers. The difference is statistically significant, as shown on the right side of Table 4. In contrast, during the Qing educated men had fewer brothers than not-educated men. This demonstrates a change in the human capital–fertility relationship when we move from the Yuan–Ming to the Qing. During the Qing, the fertility and human capital patterns in the sample support a negative relationship between child quantity and child quality, whereas during the earlier period the data points to a positive relationship between child quantity and quality.

Furthermore, I find that the negative relationship between the number of brothers and education is stronger in the early Qing than in the late Qing period. Restricting the analysis to men born during the Qing years 1644–1800 (“Early Qing” in Table 4), educated men have on average 0.35 brothers less than not-educated men, compared to 0.25 fewer for the entire Qing era. This is initial evidence for a weakening of the quantity–quality relationship towards the end of the Qing. I will return to this in Sect. 5.3 below.

5.2 The human capital–fertility relationship during the early Qing (1644–1800)

The model laid out in Sect. 3 implies a negative relationship between optimal child quantity \((n^{*})\) and optimal child quality (\(e^{*})\); it is summarized in equation (3), which solving for \(e^{*}\) can be rewritten as

In this section, I employ simple linear regression specifications to test for this negative relationship between \(e^{*}\) and \(n^{*}\) in my sample. Consider the following OLS specification:

where \({ Education}_i^{hl}\) is determined by the highest lifetime education level of individual i. \({ Brothers}_i^{hl} \) is the number of his brothers, and \(\varepsilon _i^{hl} \) is the regression error.Footnote 42 The superscripts h and l stand for household and lineage, respectively. In my analysis, I consider a range of other determinants of human capital acquisition, including parental resources, lineage, health, and time trends. These factors are captured by the vector X in Eq. (5), and they will be included successively.

The simple regression of education on the number of brothers gives a negative coefficient of \({-}\)0.09 (Table 5, column 1). The coefficient implies that one less brother is associated with a 0.9 percentage point higher chance of being educated. This compares with a chance of about 7% that a randomly picked man in my sample would be educated. I will return to a discussion of economic magnitudes below. Inferences are based on standard errors clustered at the level of the household (as defined by the father), which allow for an arbitrary variance–covariance matrix capturing potential correlation in the residual error term (Wooldridge 2007, Chap. 7). In particular, one reason for this clustering is that parental decisions may induce a correlation between the education levels of their sons. It is shown below that other assumptions on the error term, including two-dimensional clustering, do not affect these results very much.

An additional determinant of educational outcomes could be birth order (see Black et al. 2005). Including a fixed effect for each birth order level increases the (absolute) size of the coefficient on Brothers (column 2), and I include birth order fixed effects in all remaining specifications. Next, I include the birth year of the man, capturing trends in human capital acquisition over time (Trend). The birth year of the man enters the regression with a negative coefficient, which picks up the fact that the fraction of men in the sample that are educated declines over time (column 3).Footnote 43

Given that the sample includes lineages with quite different mean levels of human capital (Table 9, column 1), and the resources that come with that, it is reasonable to believe some men have an easier time to acquire human capital themselves than other men, irrespective of fertility levels. Furthermore, while average human capital levels for the lineage are observed, there could be many unobserved determinants of Education that remain unobserved. To the extent that these are constant over time the inclusion of lineage fixed effects will eliminate their effect, and the Brothers coefficient is identified from changes within the lineage over time. Results are shown in column 4 of Table 5. There is a substantial increase in the \(\hbox {R}^{2}\), indicating that fixed cross-lineage differences are important. While the size of the Brothers coefficient falls, it remains significant at standard levels. Nevertheless, one would have overestimated the importance of fertility differences without accounting for heterogeneity across lineages.

Since the sample has, for each man, linked information on three generations, I can quantify the role of inter-generational transmission of human capital for educational outcomes in the current generation. Table 5 shows that a man’s chance to become educated is increasing in both his father’s and his grandfather’s human capital (column 5). Quantitatively, the size of the coefficients on father’s and grandfather’s education indicates that past generations’ human capital matters a great deal. In particular, the coefficient of about 0.09 on grandfather’s education is larger than the chance that a randomly chosen man from the sample is educated (about 7%). At the same time, having an educated father and grandfather put a man into a quite distinct environment in terms of his chance to become educated: in the sample, one in three men with educated father and grandfather becomes educated himself, whereas for a man with neither educated father nor grandfather, the chance that he becomes educated is only one in 50.

In the following, I consider a number of other household characteristics that might affect the relationship between fertility and human capital acquisition. In particular, it is possible that a lower number of Brothers is the result of demographic factors that induce couples to have children relatively late, or to have longer periods between child births (spacing). While such behavior could be motivated by the desire to raise average child quality, there are other possible reasons, such as health or resources factors.

Some light can be shed on these effects for the relationship between fertility and education by considering the parents’ age at their son’s birth, because older parents will typically have fewer children. We see that while human capital acquisition is less likely for men with relatively old fathers, if anything, including father’s age at the man’s birth strengthens the negative relationship between the number of brothers and education (column 6). The mother’s age at the man’s birth does not matter (column 7).

Next, I turn to the health of the parents, which is correlated with their longevity, and to the extent that if death occurs during the woman’s period of fertility it will directly impact the number of children she can have. The results indicate that longevity of the father is unrelated to the human capital acquisition of his son (column 8). In contrast, the man’s chance to become educated is increasing in the longevity of his mother (column 9). According to these results, the son of a woman dying at age 50 has a one percentage point higher chance to become educated compared to a man whose mother dies at age 40. This could be due to the role of mothers in the education of their sons. Overall, including demographic and health controls strengthens the evidence for a negative relationship between child quantity and child quality (compare the coefficients on Brothers in columns 5 and 10, respectively).

I have also considered the total size of the household, as well as the gender composition of the children. Size is, to an extent, an indicator of household resources. Note that conditional on covariates already included, the number of total siblings a man has is not significantly related to his education level (column 11). Furthermore, his chances of becoming educated are also unaffected by the share of female children the household has (column 12). In contrast, when the father has one wife a man’s chance to become educated is significantly lower (column 13). Men growing up in households where their father marries more than once, by contrast, have a better chance of becoming educated. This could be due to relatively abundant resources in such households. We also see that a man’s chance to become educated is positively correlated with his age at death. Lifespan can enter directly or it may be a measure of health, which increases education prospects.

Overall, controlling for trend, the inter-generational transmission of human capital, demographic, health, and household size effects, as well as unobserved heterogeneity across lineages, there is a negative relationship between fertility and human capital acquisition. The coefficient on Brothers in column 13 is about \({-}\)0.09. It means that during the early Qing (1644–1800), having one fewer brother raised the chance of a man to become educated himself typically by about 0.9% points. Evaluated at the mean of Education, which is 0.067 during this period, this amounts to a 13% higher chance of becoming educated. Arguably, this is an economically significant magnitude.

One might be concerned that this average quantity–quality relationship might be of limited value if subsets of the Tongcheng population exhibit fertility–human capital patterns that differ strongly from this. Therefore, I estimate the baseline specification for a number of subsamples (see Table 6). In the first subsample, I focus on the men whose father is not-educated. Given the strong inter-generational transmission of human capital documented above, these men would generally be relatively unlikely to acquire human capital themselves. This is reflected in the relatively low average education level of 3.7%, compared to 7% in the baseline sample (see columns 1 and 2, bottom). Also for the subset of these men, I estimate a significant quantity–quality relationship. The coefficient on Brothers is now smaller than before, at \({-}\)6.8 versus \({-}\)9.4%. Given the lower average education level for these men with a not-educated father, however, lower fertility in the form of one less brother is associated with a moderately higher probability of acquiring education when compared to the education mean of the sample (bottom of Table 6, column 2).

In a second specification, I focus on the subset of men who have both educated fathers and grandfathers. This is an elite group of \(\hbox {n} = 347\) men. Although the sample is relatively small, there is evidence (significant at the 10% level) that higher fertility is associated with lower human capital levels for these men (column 3). The coefficient on Brothers is about \({-}\)0.42, which is more than four times the size of the coefficient for the sample as a whole. However, these elite men have roughly a one in three chance to become educated (mean of Education is 0.346, see the bottom of column 3). As a consequence, the relatively high coefficient on Brothers means that one brother less for these men is associated with a higher chance of being educated of about 12%, quite similar to the figure of 13% that I obtain for the sample as a whole. This shows that the quantity–quality relationship applies to rather diverse subpopulations, and furthermore the implied economic magnitude compared to typical education levels of the subpopulations does not drastically differ.

It is interesting to compare this pattern with the finding that fertility in pre-transitional Europe was not high everywhere; rather, there were elite ‘forerunners’ that practiced fertility control even though the population as a whole was still in a high-fertility regime (Livi Bacci 1986). The results for the elite men reported in column 3 of Table 6 clearly indicate that this pattern was not unique to Europe but also existed in China. More surprisingly perhaps, my finding that there was a significant quantity–quality trade-off in China in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in non-elite households as well (column 2, Table 6) seems to go beyond what we know about pre-transitional Europe. There are two opposing factors: on the one hand, Table 6 provides evidence that the quantity–quality trade-off existed for large parts of China’s population, while on the other hand the regression coefficient in column 2 is small, at least compared to that for the elites in column 3. More research is needed to clarify how important this quantity–quality relationship in the Early Qing was in the aggregate.

5.2.1 Robustness

Probit estimation I begin by showing probit specifications analogous to the earlier results: see Table 10. Marginal effects for Brothers are shown at the bottom of the table. In the baseline, the marginal effect of Brothers is \({-}\)0.098 in the probit. The estimates are generally similar to those obtained with OLS in Table 5.

Temporary shocks, trends, and two-way clustering In Table 11, I examine the importance of temporary shocks and lineage-specific trends for the results, and also explore other assumptions on the error term. Specifically, the baseline specification of column 13 in Table 5 is repeated in the first column. Shown are four sets of alternative standard errors. The first set is clustered by household, as before.Footnote 44 The second set of standard errors is clustered both on household and by decade (16 decades between 1644 and 1800). This accounts for possible correlation of the residual error due to specific shocks in one or several of these decades. The third set of standard errors is two-way clustered by lineage and decade. This accounts for any correlation in the residual errors of men belonging to the same lineage, for example, because lineage resources are utilized in the acquisition of human capital for these men. Finally, I present two-way clustered standard errors by household and by lineage-specific cohort. Comparing the different sets of standard errors shows that inferences are not much affected by these different assumptions on the error.

I have also considered a generalized time trend by including fixed effects for each decade in the regression (column 2). This has no major effect on the estimates, indicating that the results are not driven by temporary shocks. Table 11 also shows results that include separate trends for each lineage. To the extent that my results are affected by cross-lineage differences in how much the relationship between fertility and human capital changes over time, separate trends for each lineage would pick this up. The results suggest that differential trends across lineages play no role for my results (column 3).

Finally, I show results that include indicator variables for men that were born in one of the years in which a new emperor came to power during the period 1644–1800 (reign change). Such years can be associated with turmoil and other changes that might affect the relationship between fertility and human capital. The results show that reign changes do not greatly affect my findings (column 4).

Human capital heterogeneity Here I examine the quantity–quality relationship separately for those men that prepared for the examination but did not pass from those men that passed at least the first level examination. It is reasonable to assume that the latter acquired a higher level of human capital than the former. Results are shown in Table 7.

The baseline quantity–quality relationship is shown in column 1 for comparison. I first focus on men that have prepared for (and hence, acquired human capital) but did not pass the first-level state examination. The men who successfully passed at least the first-level state examination are dropped from the estimation. I estimate a coefficient on Brothers of \({-}\)0.029, not significant at standard levels. This is evidence for, at best, a weak quantity–quality relationship for these men. One interpretation of this is that these households did not reduce fertility enough to be successful in the state examinations.

In contrast, the significant relationship between child quantity and quality reemerges when I drop the men who prepared but failed to pass the first-level examination from the estimation (column 3). Generally, the regression results for these men are similar to the full sample results given in column 1. Overall, these results indicate that not only was there a negative relationship between child quantity and quality during the early Qing period, it was also stronger for those with higher human capital investments.

Nearest-neighbor matching One might be concerned that the number of educated men in the sample is small compared to those that are not educated (roughly 7 vs. 93%, respectively), and as a consequence the two groups might differ in ways that cannot be controlled for in a regression. To address this issue, recall that the model describes an equilibrium relationship between child quantity and quality (Eq. 3), and an alternative approach to the quantity–quality relationship is to ask whether educated men had a lower number of brothers compared to the men who were not-educated.

Given that Education is a 0/1 variable, a matching estimator is natural: each educated man in the sample is paired with the one not-educated man who is as similar as possible based on observables, except education (nearest-neighbor matching). The match is based on the propensity score using all covariates in the baseline regression (Table 5, column 13). Using this approach, I find that educated men during the Early Qing had on average 0.27 fewer brothers than men without education (Table 7, Panel B, column 1).

For those men that studied for the state examination but did not pass, the difference in the number of brothers from those men that did not acquire human capital is \({-}\)0.22 (column 2). The third column shows that men who came from families that made relatively high human capital investments, as evidenced by the men themselves being educated, typically have 0.285 fewer brothers.

Overall, this shows the main regression finding of a negative child quantity-child quality relationship is unlikely driven by differences in characteristics between the educated and not-educated that regression covariates cannot control for. The matching approach yields two additional results relative to the OLS. First, the focus on a more narrowly defined comparison shows that even for relatively low levels of human capital there is a marginally significant (10% level) negative relationship between child quantity and quality. Second, the nearest-neighbor matching results show that the negative relationship is strongest for relatively high human capital investments, which is not the case using the regression approach (see columns 3 and 1 in Panels A and B).

Purchased degrees Because the main analysis is focused on the human capital–fertility relationship, I have abstracted so far from those men who purchased a degree rather than passing or attempting the examinations. Is it the case that the purchase of a degree had similar implications for fertility as when the degree was obtained through human capital investments? Table 12 shows the results of this analysis.

First, coding the purchased degrees as Education equal to one instead of zero, I find that the negative relationship between quantity and quality remains (column 2). In the next specification, I include the interaction \({ Brothers} \times { Purchase}\), where Purchase is one if the degree is purchased and zero otherwise. The coefficient on this interaction is positive at about 2. This means that the quantity–quality relationship is weaker for non-human capital investments than for human capital investments. Is there evidence for a negative relationship at all? The answer is yes. While one less brother is associated with a 0.9% point higher chance of becoming educated, one less brother means a 0.6 percentage points higher chance that a degree is purchased. I have also examined whether there is evidence that the role of father’s and grandfather’s education depends on whether the degree is purchased or not, finding no evidence for it (column 4).Footnote 45

5.3 The fading of the quantity–quality relationship towards the end of the Qing

In this section, I examine the evidence for a change in the quantity–quality relationship over time. As discussed in Sect. 2, there is evidence that the return to human capital fell during the Qing era. According to the model presented in Sect. 3, this should lead to a weakening in the relationship between fertility and education. To be sure, China witnessed many other changes over the Qing period, including the opening of foreign treaty ports in the nineteenth century, natural disasters, rebel activity, and the eventual end of China’s imperial period. Because this poses challenges for tracing the quantity–quality relationship over relatively short periods of time, I first adopt a broad approach in which only two sub-periods are compared, the Early and the Late Qing. My baseline for the split between early and late is the year 1800. Below, the robustness of the findings with respect to this breakdown into two periods is discussed.

The coefficient on Brothers for the Early Qing period of 1644–1800 is the baseline result of \({-}\)0.09 (Table 5, column 13), which is reproduced in Table 8, column 1. For the Late Qing period, I estimate a coefficient on Brothers of virtually zero (Table 8, column 2).Footnote 46 In the early period, lower fertility was associated with higher human capital acquisition, while this is no longer the case in the Late Qing period. The result is even more remarkable given that several other determinants of human capital acquisition, such as father’s education and grandfather’s education, change very little from the Early to the Late Qing.

To what extent does this result depend on using the year 1800 to separate the early from the late Qing period? This is explored by shifting the breakpoint between the periods to other breakpoints ranging from 1780 to 1820. The results that emerge from shifting the breakpoint are shown as well in Table 8. The key findings are that independent of the specific year used to separate early from late Qing period: there is, first, always a significant quantity–quality relationship for the Early Qing, and second, there is never a significant quantity–quality relationship for the Late Qing. The result is confirmed using probit regressions, as shown in Table 13.

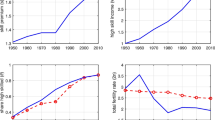

In Fig. 3, I show the probit marginal effects on Brothers for alternative dates for separating the Early from the Late Qing periods. In the baseline with periods (1644–1800) and (1800–1820), the Brothers marginal effect estimate is \({-}\)0.098 for the Early and 0.018 for the Late Qing (shown in the center of Fig. 3). For alternative breakpoints into Early and Late Qing, the quantity–quality trade-off during the Early period exists while for the Late Qing it does not.

One might still be concerned that the result of a stark change in the quantity–quality relationship from the Early to the Late Qing period is in part driven by the regression approach in which a small number of educated men are compared to a large number of uneducated men. To address this concern I have employed the nearest-neighbor matching approach from above to compare the number of brothers that the educated and the not-educated men had during the Early versus the Late Qing. These results, summarized in Fig. 4, confirm the regression results of Tables 8 and 13. Specifically, for any particular year dividing the Qing into early and late sub-periods between 1780 and 1820, during the Early Qing, nearest-neighbor matched uneducated men always had a significantly higher number of brothers than educated men. In contrast, during the Late Qing the matched uneducated men never had a significantly higher number of brothers than their educated counterparts. This confirms the earlier results.

Additional robustness It could be that my results for the Late Qing period are affected by temporary shocks, foreign intrusion, as well as internal warfare. To assess the influence of these events on my results I re-estimate the fertility–education relationship with decade-specific fixed effects (Table 14). Comparing column 2 with column 1, there is no evidence that the results on quantity–quality during the Late Qing are strongly affected by such shocks.

I also revisit the question of non-human capital investments to obtain official positions in the form of purchased degrees. Because of low tax revenue during the Taiping Rebellion, the government resorted to the sale of government office during the mid-nineteenth century. I ask how this affects my estimate of the fertility–education relationship during the Late Qing. I begin with a specification where the Education variable is recoded from zero to equal one in the case of a degree purchase, which yields a negative but insignificant coefficient on Brothers (column 3, Table 14). I also allow for an interaction variable between Brothers and Purchased degree. This interaction enters positively, indicating that there is more evidence for a child quantity–quality trade-off for human capital investments than for degree purchases. This confirms the result for the Early Qing era above. With about 1.5% of the Late Qing sample having a purchased degree, the marginal effect of Brothers in the case of degree purchase is about \({-}\)0.01, compared to about \({-}\)0.04 in the case of human capital investments (no degree purchase). In either case, the coefficients are not significantly different from zero. Thus, accounting for the extent of degree sales of the Qing government during the nineteenth century does not change the main finding.

Overall, I find a robust quantity–quality relationship for the relatively early years of the Qing. This is consistent with the hypothesis that the state examinations provided households a clear path to upward mobility through human capital accumulation, which in turn was facilitated by a relatively low number of children. Towards the end of the Qing, this quantity–quality relationship disappeared. This is consistent with the lower return to education shifting the household choice away from quality (education) and towards quantity (fertility).

6 Conclusions

The changes promoted by the Qing state in the civil service examination increased its effectiveness as an exclusive and predictable channel through which men could pursue high-status official careers. The material required years of study and the human capital investments were not small. The emergence of the negative child quantity–quality relationship provides evidence of fertility control for human capital objectives in China by the seventeenth century. This setting of high returns for child investment gives rise to a negative relationship between fertility and education—educated men come from smaller families after controlling for other factors, and the relationship holds not only for high-status families but also for poorer families.

Towards the late Qing, however, population growth combined with diminished odds of examination success changed the returns to the kind of education that was at the heart of the civil service system in China. Historical evidence suggests a decline in the return to education towards the end of the Qing, and this is consistent with the results in this paper showing the disappearance of the negative quantity–quality relationship. The timing of the appearance as well as the disappearance of the quantity–quality tradeoff shows that economic incentives affected the choice between the quantity and the quality of son outcomes.

More broadly, my findings present evidence supportive of the idea that child quantity–quality tradeoffs are not necessarily the consequence of industrialization, which would not arrive in China for at least another century. I also show that the negative quantity–quality relationship and the return to human capital can rise and fall, emerge and then reverse course. China’s lagging performance relative to Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries has triggered influential work on the sources of divergence. The declining rewards to human capital in China in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries seem broadly consistent with the history of divergence.

Notes

World Bank (2014).

As summarized in Esherick and Rankin (1990): “There is a strong tendency for this literature to view state-elite competition as a zero-sum game. The autocratic state seeks full fiscal and coercive power over rural society, while local elites—sometimes representing community interests, sometimes pursuing their own gain—seek to check the state’s intrusion...most of this literature sees order as the product of state control. When elites organize it is a symptom of crisis, conflict, or the disintegration of established order.” See also Hsiao (1960) and Wakeman (1975). Fear of regional clans and military leaders was also the motivation of Sung emperors, who promulgated the civil service examinations in 960; on this point, see Elman (1991).

Although this suggests a greater degree of cooperation and integration between the center and local actors, Beattie’s (1979) study of Tongcheng county shows that families also used income from land holdings, coupled with civil service, in order to maintain status. In other regions, merchants entered elite status and civil service through activities in trade or patronage of the literati lifestyle. See also Naquin and Rawski (1987) for other detailed accounts of local society.

For example, after Newcomen and Watt pioneered the steam engine in eighteenth century Britain, by the 1830s the first railway lines were being constructed in Germany as well as the United States. Between 1825–1850, markets in Europe were much more integrated than they were just 50 years earlier, suggesting that the roots of modernization had taken hold (Shiue and Keller 2007). Printing and the Enlightenment also played a role in the timing of growth in Europe (Mokyr 2012).