Abstract

We paint a detailed picture of whether the trade-off between human capital and fertility decisions was shaped in a pre-industrial society during the Qing dynasty. Using data from the China Multi-Generational Panel Dataset-Liaoning (CMGPD-LN), we investigate 16,328 adult males born between 1760 and 1880 in Northeast China. We control for birth-order effects and for a rich set of individual-, parental-, household-, and village-level characteristics in regression analyses on individuals from different household categories (elite vs. non-elite households). Our findings suggest that sibship size, as instrumented by twins at last birth, starts to have a substantial negative effect on the probability of receiving an education, indicating the emergence of a child quantity-quality trade-off for large parts of the population belonging to the Eight Banner System in Liaoning around the mid-Qing dynasty. Our results provide supportive evidence for the unified growth theory, showing that the decreased fertility rates in pre-transition China could be a result of rational behaviors perpetuated by households in response to higher educational returns and accessibility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The unified growth theory (UGT) aims to explain the relationship between demographic changes and economic growth, modeling the transition from Malthusian stagnation, featuring decreasing returns to labor, high fertility, and a positive association between income and population, to a developed economy with a high income and low fertility rates (Galor 2005; 2011). Most of those models show that investments in human capital explain the negative relationship between income and population size that emerged in some countries at the end of the nineteenth century.Footnote 1 The increased demand for education during the later phase of the industrial revolution, owing to complementarities of technological progress and human capital, triggered a historical fertility decline in Western Europe. The trade-off between the number of children in a household and each child’s human capital was therefore considered a crucial mechanism in the transition at the basis of the UGT (Galor 2011; Galor and Weil 1999; 2000; Galor and Moav 2002; Galor and Mountford 2008).

The quantity-quality trade-off theory states that parents limit the number of children they choose to have as a way to increase the quality of their offspring.Footnote 2 Although the relationship between human capital and fertility rates in industrialized countries in the midst of their transition is well established (e.g., Becker et al., 2010, for Prussia; Klemp and Weisdorf, 2019, for England; Murphy, 2015, for France; and Fernihough, 2017, for Ireland), with the notable exception of Shiue (2017), few scholars have documented this trade-off was also present in the pre-industrial revolution era due to a lack of historical data.

The focus of our paper on the Qing dynasty in China permits the examination of the universal validity of UGT. The paper argues that the fertility restrictions enacted in a non-industrialized society could also be based on rational parental decisions related to the accumulation of human capital and shows that high returns to education and improved access to educational resources were the triggers of the emergence of the quantity-quality trade-off.

We investigate historical micro-data from the China Multi-Generational Panel Dataset-Liaoning (CMGPD-LN). A caveat is that the population under study as described in the CMGPD-LN dataset cannot be taken as representative of China as a whole. The sample households, which consist of farmers renting hereditary land from the Qing government to provide food for military members of the imperial clan and their families (the Eight Banner System), are likely to be subject to different incentives than other Chinese households. On the one hand, human capital incentives may have been relatively low because farmers could not change their job freely. On the other hand, households may have been able to acquire relatively more human capital because they had a relatively secure flow of income. Final answers on this will have to await future research on additional Chinese populations.

In the regions covered by the dataset, Confucian education was introduced in the late seventeenth century as a consequence of the adoption of the Civil Service Examinations (Keju). It rapidly expanded and became popularized beginning from the middle of the Qing dynasty (i.e., the 1760s and 1770s) when the number of Confucian academies (Shuyuan) and private schools (Sishu) dramatically increased. These led to more children gaining access to education regardless of their socioeconomic status. It is therefore possible that the increased incentives to control the birth rate in the region were motivated by the newly acquired educational goals of sample households.

The results of this paper support our hypothesis. We find a negative link between human capital and fertility rates for sample households as a whole with sons born between 1760 and 1880, which corresponds to the period when a large number of privately funded Shuyuan and Sishu were established and were made accessible for people from all socioeconomic backgrounds. For men from elite households, having one fewer brother leads to a 17% increase in the probability of obtaining an education, while for those from non-elite households, the effect of sibship size on educational attainment is smaller.

We show that the observed pattern would not have occurred if the trade-off had been purely mechanical; instead, it was likely to be associated with local educational development. First, by including village-level controls as well as birth year, regional, and register dataset fixed effects, we attempt to remove other economic and demographic factors and trends that might have led to the trade-off. Second, using samples born before 1760, we show that the negative relationship between male sibship size and human capital investment was not observed when there were not enough schools to admit children from non-elite households. Third, we explore the geographic and temporal heterogeneities in the effects by including the number of Confucian academies and the quota for academic titles. Fourth, we show how the opportunity costs of education enter the quantity-quality trade-off function. For causal identification purposes, we use the number of male twins at the last birth as our instrumental variable, aiming to control for unobservable determinants of fertility and parental choices.

The paper contributes to the literature in three ways.

First, our paper tests the validity of the UGT from several aspects. To begin with, it provides evidence that the quantity-quality trade-off was also present in pre-industrial China apart from the industrialized Europe and extends the past literature that used aggregated data to explore the trade-off, which might conceal important heterogeneous factors. Increasingly more researchers have employed either rather disaggregated information (Becker et al. 2010; 2012; Murphy 2015) or individual data from genealogies and registries (Klemp and Weisdorf 2019). The extensive historical micro-level records employed in this paper allow us to capture the trade-off of interest by using essential individual and household characteristics and enable the usage of various econometric estimation procedures designed to alleviate endogenous issues and obtain unbiased results.

In addition, our conclusion is consistent with another vital implication of the UGT, namely that cultural and institutional characteristics affected the pace at which society transitioned from no quantity-quality trade-offs to adopting such trade-offs (Galor 2005; 2011).Footnote 3 Our targeted region, Liaoning, has undergone a process of transitioning from a military-based society to a typical Confucian one that values traditional education; such a massive institutional and cultural change further shaped society’s preference for human capital during our period of interest. Our discovery therefore offers evidence that the different trade-off levels observed over time can be attributed to changes in the cultural and institutional characteristics of the region.

The UGT also argues that variations in those characteristics may lead to differences in the cost of and opportunity to access education across social classes and status (Galor 2010). Our findings support this testable prediction; the variety in the socioeconomic levels of the subpopulations residing in Liaoning allowed us to investigate whether the quantity-quality trade-off can also be seen as a function of social status and responsibility.

Second, our paper tackles the long debate on the timing and origins of fertility controls in the male population of pre-modern China. The possibility of a fertility inhibition model emerging in ancient China has generated widespread controversies among historical demographers. Malthus (1798) believed that the fertility decline in ancient China had been mainly caused by involuntary positive checks such as war, natural disasters, and infectious diseases. In contrast, since the 1990s, some have reinterpreted the fertility trends apparent since the Qing dynasty, postulating that internal fertility controls played a greater role than external inhibitors in the decrease of fertility rates.Footnote 4 A groundbreaking view was that education-motivated fertility restrictions started as early as the seventeenth century in China. Using data from genealogies of households in the Tong Cheng County of Anhui, Shiue (2017) confirmed that, during the Ming and early Qing dynasties, the fertility rates show a similar pattern to those of Western populations in the later part of the Industrial Revolution, with a substantial substitution of quantity by quality within the population, while by the late Qing dynasty (around the year 1800), there was no significant trade-off anymore.

Our study uses a unique sample of the population belonging to the Eight Banner System and shows a different temporal pattern of changes in the offspring quantity-quality trade-offs compared to the areas where Confucian education had remained constant. More specifically, Liaoning was a military-based society, and the transition of its institutional and cultural features which favored human capital formation only appeared around the middle of the Qing dynasty; therefore, fertility restrictions motivated by human capital emerged one century later than in Anhui and other inner regions of China.

Last but not least, numerous studies of the trade-off between human capital and fertility rates in China are based on contemporary populations and can therefore not quantitatively support the transition occurred in pre-modern history.Footnote 5

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 briefly introduces the historical background of the northeastern region and its education. Section 3 discusses the CMGPD-LN dataset and the variables of interest. Section 4 introduces the model and presents the empirical results. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2 Historical background

2.1 Northeast population and ruling system

The Jurchen, a strong military federation of nomadic tribes living in Northeast China (provinces of Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang nowadays), conquered northern China and founded the Jin dynasty (1115–1234). Their ethnic descendants, the Manchus, established the Qing dynasty, later conquering the Ming dynasty and ruling over the entirety of China between 1644 and 1911.

After the Qing dynasty started to take over Inner China (i.e., the Central Plains) in 1644, millions of Manchus moved westward; at that time, Northeast China was mainly characterized by deserted cities, castle ruins, and fertile fields devoid of the necessary labor force.Footnote 6 Due to a belief in Manchu (including Liaoning) being “the homeland of the emperors and their ancestors” and according to which “other ethnic groups should not exploit the natural resources in Manchu” (Reardon-Anderson 2000), a formal lockdown policy was enacted in 1668, which led to a custom palisade being built to restrict the movement from Inner China or Mongolia (Elliott 2000). Since the subsequent inflow of immigrants was mostly illegal and limited, the population growth remained low.

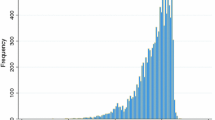

In the 1760s, after getting the permission of the Qing government, Borjigit, the prince of Mongolia, recruited immigrants to cultivate the grasslands on the Mongolian territory on the northern side of the palisade. On the one hand, upon hearing this and due to the combination of overpopulation in their area, an increasing number of residents from the northern part of the Central Plain risked their livelihood to immigrate across the palisade, moving their families to the sparsely populated Northeast. On the other hand, the Manchu who owned the land in the Northeast were eager for labor due to the shortage of workers and their limited farming experience (Shi 1987). For Han migrants from the Central Plains, the manor owners provided them with various conveniences to settle down in the Northeast (Lu 1987). The Qing government noticed the influx of immigrants and acquiesced in these movements. In 1861, most restrictions on migration in this region were officially lifted to resist external humiliation and defend the frontier, and Yingkou started to serve as a commercial port. After this change, the population started to grow at a much more dramatic rate. Figure 1 depicts the population in Liaoning over time; the increase in the population growth rate is generally associated with the acquiescence (since the 1760s) and formal approval (since the 1860s) of Han immigration.

Population in Liaoning (Fengtian). Note: The gray dots indicate the population size in the years with a record; the dashed line represents the fitted line of population growth. Until the 1860s, there has been a formal restriction on migration, with some Han immigrants moving to this region secretly since the 1760s. Source: Zhang (2010) and Zhao (2004)

Though being a settler society, Liaoning was very different from others, as the lifting of its migration ban occurred quite late, and its land resource was so abundant and uncultivated. The cultivated land size in Liaoning was just 0.03% in 1661, 0.2% in 1724, 1.3% in 1753, 10.9% in 1812, and 14.6% in 1887 (Li 1957; Shi 2011). Therefore, various phenomena driven by the land unavailability in other settler societies have not happened to determine fertility rates and other household decisions in Liaoning before the 1900s. First, the population pressure on the arable land per capita has never been a problem; thus, Liaoning did not belong to a Malthusian world. Before the restriction was lifted, the population of Liaoning (Fengtian) in 1741 was 377,454; in 1760, it was 649,394, in 1796 it was 843,579, 1,674,000 in 1818, and around 2,439,000 in 1860 (Zhang 2010). Given that Liaoning’s size was around 130,000 km2, the population density increased from 2.9 to 18.8 persons per km2; the statistics were much smaller (around 1/20–1/30) than those in provinces of Inner China (such as Shandong province). The arable land per capita first increased with the inflow of the Han exiles in cultivating more land and then decreased slightly to 10 mu (1 mu= 666.7 square meters) in 1860; the values both before and after the lifting of restrictions in the 1860s were considerably exceeding the national average in the same period and the population pressure level.

Second, the price of agricultural products has not been much changed. Wang (2018) supported that the migration from Inner China led to almost no change in food prices before the 1900s. This is because although the demand for food has increased as a consequence of the increased population, land exploitation was promoted on the supply side and food production has also increased. Third, the battle for land has never occurred between locals and Han immigrants, as Han people also acknowledged the absolute privileged position of Manchus and found it better to cooperate with them. Starting from Qianlong Emperor’s period, the conflicts between migrants and natives have reduced to a minimum (Wang 2016), making it unlikely to lead to the outcomes explored in the literature (Dippel 2014; Hao and Xue 2017).Footnote 7

Even before the rulers entered the Pass in 1644, all the people living in Liaoning, including native Manchu and Han Chinese or Mongolian immigrants, were included under the Eight Banners system, which was a civil and military-based administrative system applied in this region (Gao 1996; Liang 2005). The bannermen were mainly engaged in military activities, and the status of people depended mainly on their military performance in war during the early Qing period. However, during Qianlong Emperor’s reign, when the Qing government settled down in the country well, the role of the Banners soldiers gradually weakened in the military power of the Qing government, and many Han soldiers were dismissed. They did not leave the region but rented hereditary land from the Qing government to make a living on agricultural activities (Ding et al. 2004). Moreover, the inflow of Han people starting from the mid-Qing dynasty further spread the Confucian philosophies and governance system. As a consequence, the original Eight Banner system ruling system was largely affected, which changed from a military-oriented one to one that consisted of more economical and administrative duties and functions, such as agricultural production, and combined the Confucian ruling system, with some of its key components playing a dominating role in governing people.

2.2 Civil exam and popularization of education

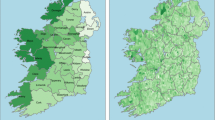

One fundamental change made by the Confucian ruling system was the adoption of the civil exam, which aimed to recruit educated and talented citizens into the government of the country (Shi 1994). Before the Qing dynasty, this exam was almost nonexistent in this region, as depicted by Fig. 2. To develop an effective form of governance and consolidate the empire, the Qing dynasty adopted the civil exam left from the Ming dynasty and expanded it throughout all of China; this included the Manchu region, although the introduction of the exam was delayed by half a century when compared to the other provinces in the northern part of the Central Plain (Zhang 2000). There were three levels: the prefectural exam, the provincial exam, and the Jinshi exam (Chen et al. 2020). The first step was to pass the prefectural exam; the successful candidates could then become Shengyuan (or Xiucai) and were eligible to take the provincial exam. Only a few of them could pass this second exam and receive a Juren title. Finally, those with a Juren qualification had a chance to take the final stage of the civil exam. Only a few of those holding a Juren qualification could obtain the Jinshi qualification.

The introduction of the civil examination system significantly increased the return to education, as qualification holders (Jinshi and Juren) were guaranteed a position in the government. The returns were not as high for the citizens with only the Shengyuan qualification, but their income was much higher than that of the average worker. Many could find employment in educational institutions, for example by teaching in public or private schools. Meanwhile, they gained several privileges, such as the right to be exempt from taxation; many of them also received a subsidy from the state. Even those who had received an education, but had not passed the Shengyuan test, had a greater chance of finding a paid, non-physical job due to their advanced knowledge and greater literacy rates; for example, many worked as bookkeepers or as secretarial staff.

The importance of Confucian education was further reinforced at the end of the seventeenth century, when the native Manchu people lost their privilege to take the civil examination and apply for governmental positions (Ren 2007; Xu 2010). Instead, they started being required to attend the same civil examination track as the Han Chinese, therefore encountering direct competition from these highly educated citizens during the application process for governmental positions (Shi 1994; Zhang 2004).

Although the education system continued to develop and the returns to schooling remained high during the entire Qing dynasty, educational resources (e.g., schools) in the early period of the Qing dynasty were so limited that they inevitably limited who had access to them, which ended up being only the children from elite households. At the early stage, the education system of the Northeast was dominated by the few existing government-run schools, which represented formal schools owned by governmental bodies (Guanxue) and included state-, prefecture- or county-run schools (Fuxue, Zhouxue, and Xianxue, respectively). They were mainly concentrated in the pre-unification Qing capital (i.e., Shengjing) and aimed at preparing officials for the local government. Their admission procedure was largely based on the administrative ranks (pin) of the candidates’ fathers or grandfathers, as being politically well-connected played a non-negligible role in being recommended and subsequently selected to become an official student (Qi 2011). As a consequence, most of the admitted students were aristocratic bureaucrats (Zhao 2004), with only a small part of them coming from among the Shengyuan qualification holders of the lower socioeconomic classes.

Under the rule of the Kangxi Emperor and later the Yongzheng Emperor, the admission system of the government-run schools was largely improved; the power of local administrators and Manchu aristocratic bannerman to recommend and send children to the schools was restricted as a way of recruiting more talented children regardless of their background. During the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, children from low-status households could also be selected to become official students (Qi 2011).

Given that the supply of government-run schools could not meet the educational demands of ordinary citizens, the Qing government offered a considerable subsidy to Confucian academies (Shuyuan) as a way to encourage their operation and satisfy the need for educational resources. However, the development of the government-subsidized academies was still restricted during the early Qing era.Footnote 8 In the early years of Qianlong’s reign (1736–1795), the Shuyuan started to use donations from industrial and commercial Confucian scholars to be able to afford a large number of their services. Starting from around the middle of his reign, the government formulated stricter rules and regulations to ensure the rights of the privately funded Shuyuan. Through these efforts, the Shuyuan were able to develop and to supplement the limited admissions in the state- or county-run schools (Xi 2011). A large majority of the Shuyuan in Liaoning were thus established around the middle of the Qing dynasty.Footnote 9

As these formal schools were still insufficiently supplied, a large number of old-style private schools (Sishu) emerged to provide training. Although Han people’s entry to the northeastern region was officially forbidden, criminalized Han intellectuals and writers were sent there in exile by the Qing government; many of them were political prisoners or intellectuals who had surrendered when the Qing army had attacked the Central Plain (Gao 1996). Under the influence of the exiled intellectuals and their descendants, the local scholars started apprenticeship programs in private schools during the Qianlong period. As a consequence, starting with the second half of the eighteenth century, these Sishu could be found everywhere in Liaoning (Zhang 2013). The objectives of private education were quite inclusive: Children from the age of 5 or 6 up to 25 or 26 years old, regardless of their social background, had an opportunity to receive an education. They actively supplemented the insufficient opportunities offered by government-run schools and Confucian academies, becoming the most important part of education in Northeast China, especially for the non-elite majorities.

To conclude, the establishment of an equitable civil exam fostered the birth of Confucian education in Northeast China, although the Confucian schools were only designed for and accessible to the aristocratic elites at the beginning. The later reform of the admission procedure of the government-run schools and the increased educational resources in this region, particularly due to the expansion of privately funded Shuyuan and Sishu starting from the middle of the Qing dynasty, eventually generated incentives for the non-elite parents to invest in their successors’ human capital. Based on the historical context examined, we propose that the high returns and accessibility to education were key elements that generated the quantity-quality trade-off in the average population.Footnote 10

3 Data and variables

3.1 Dataset

In this study, the data used comes from the China Multi-Generational Panel Dataset-Liaoning (CMGPD-LN), a large-scale dataset that comprises triennial household register data covering the period of 1749–1909; it was collected by the Imperial Household Agency, digitalized by James Lee and Cameron Campbell, and its features have been discussed in Lee and Campbell (1997) and Lee and Wang (1999).Footnote 11 Compared with other historical datasets from China, the CMGPD-LN provides accurate information on the sociological and demographic variables required for this study, including important individual data on reproduction and education, household factors such as basic information on family members, and village-level characteristics.

Most individuals included in the CMGPD-LN were peasants belonging to the Eight Banner System. The sample covered a large group of the descendants of Han Chinese immigrants who settled down in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries and a small group of native Manchus.Footnote 12 According to Mare and Song (2014), a large proportion of registered samples served as hereditary laborers of the Imperial Household and were classified as the regular farming subpopulation. Peasants belonging to this type of subpopulation rented hereditary lands from the Qing government and paid a fixed tax in return. The sons of those peasants were more likely to be employed as civil or military officials via civil exams or military service, with some even receiving honorific titles. These upward mobility opportunities brought with them a variety of privileges and substantial salaries (Lee and Campbell 2010).

Besides, the CMGPD-LN data included people from two other categories with a lower social status, namely from the specialized and the low-status administrative populations. The special duty subpopulation (13% of the total population) included peasants who provided special goods (i.e., cotton, fish, game, honey, and salt) for the imperial palace, for the military (i.e., banner) families, and for sacrificial rituals. The Qing government assigned annual service quotas; if a household could not meet the quota, it had to pay the Qing government a penalty. The low-status administrative population (6% of the total population) consisted of exiled Han intellectuals and their families, servants, and criminals of wars. They had the lowest status and had no right to rent government-owned land or to marry outside of their group (Ding et al. 2004). Although people belonging to these two subgroups had the right to be enrolled in school ever since Qianlong’s reign, their probability of receiving an education was much smaller than that of regular farmers.

From longitudinal to cross-sectional data

Given that the CMGPD-LN is a dataset explicitly collected for Event History Analysis (EHA), data on the participating individuals were repeatedly recorded every three years. However, this paper requires cross-sectional information on each individual (i.e., one record per individual) since we aim to understand the relationship among defining life decisions, such as human capital investments. To do so, we consider the birth year of a subject instead of their age and select cross-sectional values at a certain point in an individual’s life as inputs. For instance, variables such as the household size, the father’s social status, occupation, and education at the time of the child’s birth,Footnote 13 along with some time-invariant factors such as individual educational experience, the maximum number of brothers, and birth order, are all selected as main variables in the regression.

Graphic evidence

Figure 3 maps the pattern of fertility and education across time in the CMGPD-LN; in Fig. 3(a), the values on the y-axis represent the average number of siblings of both sexes for the birth cohorts 1700–1880, while in Fig. 3(b) these values represent the proportion of educated men born between 1700 and 1880. As can be observed from the figures, the reproductive rate of the region had been in decline since the mid-eighteenth century, with the likelihood of being educated increasing at around the same time.Footnote 14

Pattern of fertility rates and educational levels. Note: Panel (a) plots the pattern of fertility rates. The values on the y-axis represent the average number of brothers and sisters for the birth cohorts 1700–1880; the x-axis represents the birth year. The dotted lines represent the fitted lines of the yearly average number of siblings of both sexes for households before and after 1760. Panel (b) plots the pattern of educational levels. The values on the y-axis represent the proportion of men born between 1700 and 1880 who were educated; the x-axis represents the birth year. The dotted lines represent the fitted lines of the yearly ratio of the educational level before and after 1760

Figure 3(b) shows a different temporal pattern from that of Shiue (2017), in which the ratio of educated people experienced a substantial decrease during the Qing dynasty. First, this is because, during the Yuan and Ming dynasties, the civil exam system was at the height of its glory in Inner China regions, while being almost nonexistent in Liaoning (see Fig. 2). Second, the external shocks that eroded Central Plain China’s education system ever since the mid-Qing dynasty (e.g., westernization, rebellions, the opening of treaty ports) did not affect Liaoning at all. In contrast, the Qing dynasty was a period during which the Liaoning people transitioned to a society that valued Confucian education, which is reflected in the education plot that shows an opposite pattern from the one observed in Central Plain China. We show evidence of Liaoning’s transition to Confucian society by showing that native Manchus became more adapted to Han-style life by being more interested in going to Han-style schools and taking civil exams in Appendix Fig. A.5.

This observation in Fig. 3 suggests that, at a sudden point in time, a higher proportion of regular farmers from the northeastern region may have started reducing their reproductive rate in order to finance their accumulation of human capital. This timing coincides with the historical expansion of Shuyuan and Sishu and the increased proportion of people that valued education in this region starting from the middle of the Qianlong period (i.e., the 1760s or 1770s).

Sample limitations

Inspired by the pattern shown in Fig. 3, for the benchmark analysis we select men born between 1760 and 1880, a period when the returns to education were high and accessibility to education was possible for ordinary people, to explore a quantity-quality trade-off among a large proportion of the population in this region.Footnote 15

Since women in ancient China had neither political positions nor jobs and since there is less information recorded on all the female unmarried household members, we then restrict our analytical sample to men who have survived into adulthood.Footnote 16 The unique parental ID allows not only for the matching of parental education and social status, but also for the identification of brothers. Individuals without a valid parental ID or those whose brotherhood linkages could not be identified are excluded from the sample. By merging several files into one dataset, household information and other regional-level variables are linked to personal data. Those whose household and village IDs could not be traced are excluded from the analysis. Taking into account the possibility of mistakes and recording errors during the data collection process, we also exclude those observations with unreasonably extreme values or inconsistent records on some key variables such as the year and month of birth of a child.

Lastly, our sample households only consist of those belonging to the regular farming population; we exclude the other two subpopulations, as we do not expect to find a relationship between fertility controls and education in these two groups.Footnote 17

All these restrictions leave us with 16,328 records for 16,328 individuals born between 1760 and 1880 and from approximately 698 different villages.Footnote 18 A more detailed, step-by-step sample exclusion process and its related robustness checks are reported in Appendix Table A.1.

3.2 Variables

The dependent variable is a dummy variable indicating if an individual has ever passed one or more levels of the civil exam (obtained from the variable Examination in the dataset) or if an individual was an official student (from the variable Guan Xue Sheng in the dataset).Footnote 19 A smaller proportion of the official students were preparing for the Shengyuan exam (the entry-level exam of the civil service exam system), while most were Han Eight Banners, who managed to obtain positions as translation clerks or bithesi through some special exams for the Eight Banners. We use this dummy variable in the benchmark analysis to measure the overall level of an individual’s educational achievement; separating the two types of educational outcomes does not alter the results (reported in Appendix Table A.2). We generate the main explanatory variable by sorting and counting the total brothers of every traceable individual, which is a suitable proxy for sibship size.Footnote 20 This variable does not count the female siblings in the benchmark model due to the omission of girls in the dataset.Footnote 21

Our set of covariates includes individual- and cohort-level characteristics. The individual (including parental) covariates include an individual’s birth order,Footnote 22 a dummy variable that establishes whether the individual was an ethnic Manchu or not, three dummy variables indicating if the father of the individual held a salaried official position or title (e.g., soldier, artisan, or clerk), if the father had received an education, and if the father held a purchased title, and a variable reflecting the father’s birth order. The characteristics of an individual’s father are considered to control for the potential endogeneity of fertility choices due to parental preferences. We also include birth cohort fixed effects, which account for secular trends and patterns of education.

The household-level covariates account for the endogeneity that comes from one’s family background. A household is defined in the CMGPD-LN dataset as referring to the extended family; such a family included several second-generation couples and third-generation household members living together. These covariates include all household income from salaried positions and household size. Household size also counts females, particularly married females such as wives and mothers, because this variable is included to count how many people the household budget needed to feed.Footnote 23 We consider the values measured at each individual’s birth in our analysis.

Village-level control variables are also considered, including several birthplace cluster dummies (i.e., for the northern, central, south-central, and southern regions), the population density, and the gender ratio of the village of residence at one’s birth. These variables account for regional economic development and other demographic elements. The dataset (or register) fixed effects are also included, which capture data generation processes, as the registers are generated and named by sorting the districts and the functions of their residents.

3.3 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 summarizes the features of the independent variables, as well as the individual-, household-, and village-level control variables. The data show that 6.7% (i.e., 1,089 out of 16,328) of the individuals born between 1760 and 1880 were educated. The average number of brothers was 1.8. The individuals included in the sample were on average second-born offspring, and 3.6% of them were ethnic minorities. Few fathers had a high administrative status, with about 7.8% occupying an official position, and 1.6% of the fathers had received an academic degree.

Moreover, Table 1 reports the summary statistics by education status. Columns (2)–(4) report that educated individuals had a smaller number of male siblings than non-educated ones; the difference was about 0.39. There were also some indications of heterogeneity in resources across the cohorts: Ethnic minorities had better access to education in the northeastern region, and educated men tended to have more highly educated and high-status fathers as well as wealthier households. All these variables are explicitly controlled for in the following regression analyses.

4 Empirical analysis

4.1 Sibship size effects

We derived our theoretical framework in line with Galor and Moav (2002) which predicted a rational choice between human capital and fertility rates based on the relative returns and costs of education (see Appendix B). Given that the outcome is a binary variable, we apply a probit model and a linear probability model (LPM) to test whether our data support the theoretical predictions.Footnote 24 The outcome of the equation describing the human capital investments can be expressed as:

where Edui represents the probability that individual i was educated and had a formal degree; Sibi is the maximum number of brothers of individual i, which is a proxy for the reproductive rates. Xib is a vector of covariates including individual and parental specific features as well as cohort indicators; Wj contains the characteristics of household j of individual i. Zk further includes a series of village-level effects for village k; 𝜖i represents an error term. Robust standard errors are clustered at the level of dataset registers to account for different data generation processes.

We begin with the probit estimates and report our benchmark results in Table 2, where the dependent variable is the probability of being educated. Column (1) reports the raw correlation between sibship size and human capital investment based on the full baseline sample, which is statistically significant and negative. Column (2) includes a set of individual-, parental-, household-, and village-level characteristics, while column (3) further includes birth cohort fixed effects. The significant coefficient estimated from the full specification in column (4) indicates that, on average, one fewer male sibling is correlated with a 15% (1.08/7.10 ≈ 0.15) increase in the likelihood of human capital formation for the full sample as a whole. Although the absolute value of the estimated coefficient may seem small, it represents a significant rise in human capital accumulation at the sample average.

As mentioned in Section 3.2, our dependent variable combines two educational outcomes: whether an individual has ever passed one or more levels of the civil exam and/or whether an individual was a governmental student (Guang Xue Sheng). In Qing China, the number of successful candidates at each exam level was controlled by a quota system. The quota, especially the quota for the entry-level exam, remained stable during the Qing dynasty (after the 1730s). One concern is that if the effect of sibling number on education mainly comes from the first type of educational outcome, the negative effect of sibling number might be mechanically driven by the fixed quotas and the increased population size, rather than the quantity-quality trade-off. To address this concern, we separate those two educational outcomes by using respective dummy variables Examination and Guan Xue Sheng. The results shown in Appendix Table A.2 suggest that the effects of the sibship size on both educational outcomes remain significant, implying that the effect in the benchmark analysis is not solely driven by the effect on Examination.

However, a negative correlation between fertility rates and educational levels does not necessarily imply a rational choice made by the household. To address this concern, we perform separate analyses on samples from elite and non-elite households. The coefficients for the sibship size are significant for selected cohorts from both household types, as indicated in columns (5) and (6). As expected, the size of the coefficient is larger in column (5), which exhibits that one fewer male sibling is associated with a 17% (3.79/22.28 ≈ 0.17) greater chance of receiving an education over its mean for those individuals coming from elite households, who were able to acquire human capital more easily. For a large spectrum of population from non-elite households, one fewer brother is also associated with a 0.62 percentage points increase in the probability of receiving an education, which corresponds to a 14% (0.62/4.54 ≈ 0.14) increase when we take the mean of the outcome variable into consideration.Footnote 25 The trade-off is salient because they were born in the years in which educational resources were relatively sufficient.

We show that the results in Table 2 are robust to the change of covariates and standard errors. First, we use household size and birth order measures that do not account for females as covariates, that is, the number of male household members and birth order of male children, so that females have no way to enter into other variables in the regression. Results reported in columns (1)–(3) of Appendix Table A.3 imply that the conclusion does not alter after this change. Then, we use the natural log of the household income; this does not alter the results, as shown in columns (4)–(6). Using standard errors clustered at other levels, such as based on the village’s ID or the father’s ID, does not alter the results either, which are reported in columns (7)–(9) of Table A.3.

4.2 Inclusion of female siblings

Women were excluded from our sample due to not being eligible for education and largely omitted from household registers.Footnote 26 However, surviving women could have influenced the household dynamics in two ways. On the one hand, women still carry some weight in the household budget, and on the other hand, they enable the development of a more traditional quantity-quality trade-off model.

In the conceptual framework, a male sibling is treated as both a consumer, who was raised by the family, and a supplier, who could do farm work to support the family. If the labor income channel was significant enough, having another brother might have increased one’s likelihood of getting an education. To address this concern, we first utilize the number of female siblings as the independent variable, as female siblings in Liaoning were, to a much larger extent, consumers rather than suppliers, which could partly help with disaggregating these two opposing roles.

The results reported in Appendix Table A.4 further include the gender composition of one’s siblings in the covariates. In columns (1) and (2), we find a trade-off between the number of female siblings and men’s likelihood of receiving an education, particularly among elite households. The size of the correlation is larger than the one in the benchmark analysis after ruling out the potential influence of the labor income channel, which might have allowed for an underestimation of the effects. We then employ a sensitivity check whereby female siblings in the same household are accounted for in addition to male siblings; the results are reported in columns (3) and (4). When our explanatory variable counts all the siblings of an individual regardless of their gender, the results do not alter.

Historically, China was characterized by an extreme preference for sons, which is why it was often the case that a household would keep having more children until they had at least one boy. Therefore, for those households with only one son, the answer to the question “How many older sisters were born before the first boy?” provides a quasi-experimental variation in the number of siblings. Moreover, the number of older sisters could only affect a household’s human capital investments through the constraints that would arise from having more children to feed. Thus, this strategy can be used to show that the relationship between fertility rates and the educational opportunities allotted to sons could be causal. The results of this additional analysis are reported in columns (5) and (6) of Table A.4. In those households with only one male child, having one fewer older sister would increase the youngest son’s educational opportunity by 2.8 percentage points. This lends support to the results of the instrumental variable (IV) strategy in Section 4.9.

4.3 Status of subpopulations

One of the advantages of this paper, when compared to previous literature, is that the different subpopulations in Liaoning allowed us to investigate whether the quantity-quality trade-off is a function of social status and responsibilities. Besides our baseline sample, comprised of the regular farming population, there are two other population categories: the special duty and the low-status subpopulation. The special duty population was essentially comprised of indentured workers, whose duty was to meet the annual service quotas set by the Qing government and feed the military and imperial households; they also received subsidies from the government, and had to pay the government in cash if they could not meet their yearly quota. As these households needed a greater labor force to exploit their fixed plot of land and meet the assigned quotas, they had no incentive to educate their male offspring and, therefore, no incentive to trade quantity for quality. Column (1) of Table A.5 offers support for this hypothesis, as there is no relationship between fertility rates and education in this special duty subpopulation. The observed trade-off is the smallest out of the three population categories.

Historical documents attest that those belonging to the low-status subpopulation still had a chance to take the civil examination during our time span of interest. However, due to their low status, this chance was relatively small, and their resources were limited compared to the regular farming population. There was a small and non-significant quantity-quality relationship in this subpopulation (see column 2), only exceeding the trade-off observed in the special duty population. A viable explanation for this is that this subgroup could not rent government-owned lands and, therefore, had no specific need for male labor forces.

4.4 Addressing the concerns

There are several concerns needed to be addressed. First, there are concerns driven by different record collection processes before and after 1789. According to the codebook, the records before 1789 were from five fewer population register books and were less detailed when the data was reported at the level of the household group (zu) other than the residential household (linghu). We address this issue by using only the individual data registered after 1789. This restriction means that for individuals with records both before and after 1789, we use the information collected after 1789, especially for the household-related variable, and for individual register recodes that appeared only before 1789, we drop them from the sample. This exclusion has almost no impact on cohorts born after 1760 (with results reported in column 3 of Table A.5 ). Nevertheless, we argue that our results should not be much affected by changes in the group format process in 1789 because the household variables mostly affected (such as household size and household income) are only covariates in the analysis, and the key variable–sibship size–which is derived from the father’s ID instead of the household ID, is not severely affected by the change in the generation process of household-level variables.

Second, Shiue (2017) reported the disappearance of the trade-offs of interest around the middle of the Qing dynasty and explained it as: “China witnessed many other changes in the nineteenth century, including the opening of foreign treaty ports, natural disasters, rebel activities, and the eventual end of China’s imperial era.” However, Liaoning was not affected by most of these changes. The only notable change in the region was the official lifting of the migration restrictions in the 1860s and the abolishment of the state exam system in 1904–1905. By dividing the baseline cohort into those born between 1760 and 1840 and those born between 1840 and 1880 (see columns 4 and 5 of Appendix Table A.5), we find that the trade-off remained strong in the later-born cohorts. This suggests that, due to the differences from the more developed areas near the Yangtze River, the incentives to trade quantity for quality were only apparent in Liaoning a century later and did not experience a significant decline at the end of the Qing dynasty.

The third potential confounding explanation for our baseline results can be based on the concept of intra-household division of labor. Specifically, if some households need only one son to do the accounting work or to write letters (i.e., to be educated) while the other sons do the physical labor, then there would be a mechanical correlation between the number of male siblings and the likelihood of receiving an education. To address this concern, we conduct the same analysis for a restricted sample containing only those households with multiple educated sons; as suggested by column (6) of Table A.5, our findings remain robust. Lastly, we further distinguish soldiers from other elite types. Though the main selection method for Han soldiers was recruitment rather than hereditary (Zhao 2010), it is also true that some of the soldier positions were passed to sons or brothers. When we run regressions for soldiers and other elites separately, the trade-offs are salient for both types, as reported in columns (7) and (8).

4.5 Cohorts born before 1760

We then perform the same regression for the cohort born before 1760 to explore when and why the quantity-quality trade-off appeared in this region. From the historical background outlined in Section 2, the Confucian schools (Shuyuan and Sishu) operating at the time that this cohort was being raised were insufficient to meet the needs of the majority, which resulted in higher admission thresholds when it came to receiving an education. Column (1) of Table 3 indicates that the fertility-education correlation is essentially zero for the pre-1760 sample as a whole when controlling for other observable indicators.Footnote 27

Although the relationship between fertility rates and the acquired human capital was not salient for the pre-1760 sample as a whole, restricting the sample to children from elite households leads to a significant coefficient on sibship size. This result reported in column (2) indicates that the households who had the privilege of being allowed to send their children to government-funded schools suppressed their birth rates to focus on investing in education, which was perceived as profitable. Column (3) suggests a non-significant correlation between fertility and education of earlier-born cohorts from non-elite households.

We conduct several robustness checks to support the results estimated using cohorts born earlier. There is a concern related to the surviving age of individuals and their siblings. As the CMGPD-LN registers only started recording data in 1749, there may be limited coverage of those born in the early 1700s, as they would have had to survive to 1749 in order to be included in the dataset; as suggested by Appendix Fig. A.6, this would imply that they lived a longer life, had wealthier families, and had more adult brothers. To deal with this selection problem, we further restrict the sample to individuals born between 1730 and 1760, which means that even those individuals in the eldest cohorts (1730) had just entered adulthood at the time of the first data wave and therefore qualified to be included in the regressions. Moreover, the mean surviving age of siblings stayed at the same level since the 1730s. The coefficient shown in column (4) of Table 3 is in line with our conclusions.

Recalling the concern that the difference in the record collection process before and after 1789 would lead to a statistical artifact of the results (in Section 4.4), we use only the individual data registered after 1789 in columns (5)–(7) of Table 3. This exclusion leaves us with a smaller sample size for the pre-1760 cohorts; the number of individuals drops from 5,549 to 1,423, with 150 from elite households and 1,273 from non-elite households. This set of restricted pre-1760 observations, exempted from the changes in the data formatting in 1789, leads to the same conclusion: a significant quantity-quality trade-off for elite households and an insignificant trade-off for non-elite households. Also, when we allow an upper birth year bound (such as 1770) that leaves us with more samples, we still find similar results, which are reported in the lower panel of columns (5)–(7). Moreover, if this correlation is insignificant only because of its small sample size, we should find a significant effect when we use the bootstrap method to repeatedly select the sample 1000 times. However, we do not find it (implied by the standard errors reported in the bracket). Therefore, it is unlikely that the effects capture solely an artifact driven by the difference in the data generation process before 1789.

In addition, non-elite households which educated individuals were from might have unobservables that would predict longer lifespans for its members; this raises a concern that the negative relationship between sibship and education that might otherwise exist will be offset. However, the surviving age of siblings of the pre-1760 non-elite cohort, for whom we do not find a trade-off, do not significantly differ across education statuses of individuals (difference= 0.869, p-value= 0.484). Besides, we use the nearest neighbor matching to make the characteristics (including surviving age of siblings) more balanced in columns (5)–(7) of Appendix Table A.6 and find that education remains not significantly correlated with the sibship size of the pre-1760 non-elite cohort.Footnote 28

The results in this section suggest that the trade-off became salient with both increased returns on investments in education and greater accessibility to education (i.e., increased Han-style schools). This did not happen in Northeast China until the mid-eighteenth century when the increased educational resources incentivized also non-elite households to choose a rational trade-off between fertility and education.

4.6 Heterogeneity

We investigate the heterogeneity in the effects by looking at the density of schools established in the time span of interest. There was no historical documentation of the locations and names of Sishu, because these private schools were numerous, dispersed, and small. Therefore, we use the number of official Shuyuan (academies) as a proxy for school density. The Shuyuan in the provincial capital were relatively large, with the number of enrolled students generally reaching 200; the scale of Shuyuan at the prefecture or the county level was smaller (with around 30 enrolled students). This information was obtained from Ji’s (1996) Zhongguo Shuyuan Cidian (A Compendium on the Chinese Academies) and Zhao (1995). Although there were only 21 Shuyuan reported in Liaoning, there appear to be some geographic variations.Footnote 29

We have geocoded these academies in relation to the 13 counties of residence,Footnote 30 and explored this heterogeneity in treatment effects by first splitting the sample based on whether individuals were living a county with or without a large Shuyuan. The results reported in columns (1) and (2) of Table 4 show that the probability of households in the regions with at least one large Shuyuan to invest in human capital rises by nearly one percentage point with each one-unit decrease in sibship size, which constitutes evidence for a much stronger trade-off than in those without a Shuyuan. We then include the intensity of Shuyuan in a county (measured by the number of Shuyuan in each county and in its neighborhood counties) and the interaction between Shuyuan and the number of brothers in the regression analysis and present the results in columns (3) and (4); these show that the intensity of Shuyuan in a county is positively correlated with the probability of the individuals living there being educated. Furthermore, the inclusion of the interaction term eliminates the effect of sibship size on education, which shows that our hypothesis remains supported even when geographical heterogeneity is taken into account.

The geographical heterogeneity in the effects can also be explored by a dummy variable indicating whether the individual lived in Shenyang, the most urban part of Liaoning; the results are reported in Appendix Table A.7. Columns (1), (3), and (5) report that the fertility-human capital link was stronger in Shenyang than average. Importantly, as shown in columns (2), (4), and (6), when Shenyang is excluded, all the conclusions hold, though with a smaller trade-off size. This suggests that the trade-offs became salient not only in big cities. The previous conclusions hold when applying the same regressions to non-elite cohorts born before 1760 (see columns 7 and 8).

Temporal heterogeneity is explored by including time-varying variations in the analysis, namely, the quota of higher-level qualifications assigned to the Liaoning (Fengtian) province. We collected the information on the quota for Juren titles from Qing Hui Dian Shi Li (edited by Kun 1899) and from Chu (2012). Appendix Fig. A.8 plots the average assigned number of Juren qualifications for each birth cohort at the time point when they were between 6 and 15 years old. The permitted numbers comprised the regular and the temporary permitted numbers. The regular permitted number of Juren in the Fengtian province increased from 2 to 8, a small number when compared to the quota allotted to Shuntian (that Fengtian was part of). However, some additional admissions were also made due to special and temporary circumstances. After summing up these two numbers, we divide the number of men aged 15–50 and use it to calculate the average quota of Juren at the time when each birth cohort was of schooling age. We included the quota effects across time in our analysis to explore the heterogeneity. From column (5) of Table 4, we can observe that the assigned number of qualifications is positively correlated with education, and that the inclusion of the interaction term eliminates the direct sibship size effects, which means that our hypothesis is valid even when we account for temporal heterogeneity.

4.7 Opportunity costs of education

It is hard to estimate how the quantity-quality relationship alters in response to a unitary change in educational returns and costs, because we do not have precise information on yearly tuition fees and monetary returns to education. Besides, some of the schools were subsidized by the government or by society, which might imply that an improvement in quality would not necessarily crowd out the quantity. In light of these subsidies, it would be worthwhile to explore whether a trade-off would still occur and what could influence that.

To address these two issues, we bring in the opportunity costs (i.e., loss of labor income) associated with becoming a student. The real costs of human capital investments were not only the direct educational costs (e.g., tuition fees) but also the indirect costs, such as opportunity costs, namely the earnings that were lost by choosing to receive an education instead of working during one’s childhood.Footnote 31 Among the regular-status population, the majority of households in this region made a living from farming.Footnote 32 The profits gained from farming can reliably approximate the loss of labor income for farm households, because male children born in agricultural households were generally required to be involved in farming activities throughout their entire childhood. In contrast, individuals pursuing an education participated less in farming activities, with some of them not doing any physical labor at all, because their parents were encouraging them to focus on their studies. The CMGPD-LN contains information on annual variations in the price of rice and soy starting from 1765, which allows us to calculate the opportunity costs of education by using the average grain prices, measured by taels of silver per dan, during the period when one was school-aged (6–15 years old).Footnote 33

We then analyze the quantity-quality trade-off separately for those individuals from full-time farm households (i.e., where all the older household members made their own clothing, tools, and farmed their own food) and for those men from salaried households (i.e., where at least one older household member earned a salary as a head of the household groups, or as an artisan, clerk, soldier). The overall effect of crop price on education captures two opposite effects for farm households: the income effect (as they are the supplier of food) and the substitution effect (the higher the price, the higher the opportunity costs of education); the mathematical symbol of the overall effect indicates which one of the two effects dominates the other. The coefficients on rice prices reported in columns (1) and (4) of Table 5 suggest that the substitution effect dominates and that this effect is only influential for farm households.

The results reported in columns (2) and (3) suggest that opportunity costs played a role in determining the level of a household’s human capital accumulation (i.e., direct effect) and the quantity-quality trade-off (i.e., indirect effect) for those households relying on farming activities, regardless of the type of grain. The coefficients of the interaction terms indicate that when the opportunity costs were low (i.e., low grain prices), decreasing the sibship size led to a greater increase in human investments, namely a stronger quantity-quality relationship among agricultural households. These results confirm the importance of opportunity costs in amplifying the elasticity of quality of those households relying on farming, and provide evidence on how unitary changes in net educational returns influenced the quantity-quality trade-off, as supported by the model outlined in Appendix B. The results in columns (5) and (6) indicate that the effects of grain prices on the education decisions of salaried households are statistically zero. Individuals from these households were likely not required to work the land during their schooling years, which is why high grain prices were not their opportunity costs of education.

4.8 Netting out the birth-order effects

There remain two potential interpretations of households’ decision-making process. First, to increase the average educational achievement of a household, one had to cut down the number of children which could be raised within certain budget constraints. Second, higher educational attainment was typically associated with lower birth order, since constraining the size of one’s sibship would lead to fewer individuals with high birth order and increased average education. Previous empirical studies have not accounted for the fact that sibship size and birth order are jointly determined (i.e., a household cannot change its size while holding the average individual birth order within the family constant). In particular, if parents have the predisposition to favor children based on their birth order, then the coefficient would provide a biased estimate of the quantity-quality trade-off.

We resolve this issue using the two-steps empirical strategy from Bagger et al. (2019) and Bratti et al. (2020). In the first step, we estimate the birth-order effects while controlling for father-fixed effects. In the second step, the family size effect is captured by netting out the estimated birth-order effect from the educational outcome \(\widehat {\textit {NE}_{i}}=\textit {Edu}_{i}-{\sum }_{q=1}^{Q}\widehat {\gamma _{1q}}\textit {BirthOrder}_{ijq}\). The subscript q indicates the birth order q = 1,...,Q, where Q is the maximum number of children. With this two-stage model, we assess the effect of sibship size on firstborns by looking at the outcomes of firstborns in families of different sizes. This is because it would, for example, not be feasible to look at the outcomes of the fifth-born children when the sibship size increases from three to four, since fifth-born children are only present in larger families.

Column (1) of Table A.8 shows the estimates when using a linear specification of birth order, while column (2) allows for a more flexible specification by using specific birth-order indicators instead. The within-father estimates show that an individual with one additional unit of birth rank is 1.45 percentage points less likely to be educated, and this effect is highly significant. When the firstborns are used as the reference group, the second-born, third-born, and fourth-born children and the children with an even higher birth rank are all increasingly less likely to receive an education. These estimates are all negative and highly significant. Columns (3)–(5) report the results for the second step of our two-step estimation. When we apply the linear regression of netted education, which nets out the birth-order effect estimated in the first step, we find that the coefficients on sibship size remain highly significant, although at a smaller magnitude than those reported in Table 2.

4.9 Instrumental variable approach

The coefficients for the sibship size as estimated by the LPM are likely to be biased even after controlling for a series of observable factors, as the fertility rates may be endogenous with respect to education. We thus employ an instrumental variable (IV) methodology and explore an exogenous fertility-determinant variable represented by the birth of twins.Footnote 34

Our IV strategy explicitly uses the occurrence of twins at last birth as a plausible instrument for sibship size (de Haan 2010; Hatton and Martin 2010). Using twins at the last birth ensures that the desired fertility is, on average, the same across parents with singletons and parents with a twin birth. By restricting the sample to children born before the last birth, we avoid selection problems due to the possible differences between the households choosing to stop having children after a twin birth and the households choosing to stop having children after a singleton birth (Black et al. 2005; 2010). Siblings who shared the same parental ID and were born in the same month and year are considered twins. The twin variable is generated based on the all-male sample and therefore only includes male twins.Footnote 35 We assign a value of one to the individuals belonging to a household with twins as of the last birth. Around 2.2% of individuals had a pair of twin brothers in the family.

Table 6 presents the two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimates after implementing a linear specification at both stages. The first stage results show a statistically significant and positive correlation between twins and sibship size. In particular, any incidence of male twins at the last birth increases the number of male siblings by around 70–95%. The validity of the relevance condition is satisfied, as the calculated F-statistic of our instrument is greater than 10.

According to our second stage results, the coefficients on the instrumented sibship size are always negative and significant for the baseline cohort; the baseline estimates are biased upwards, which fits our expectations. The estimate in column (1) suggests that, for the baseline sample as a whole, one fewer brother leads to an around 3.18 percentage points increase in the likelihood of receiving formal education. Columns (2) and (3) further report the results for the subgroup analysis and show that the fertility-human capital link remains salient for individuals from both household types using an IV approach.

It is important to note that the IV approach requires the instrument to be randomly conditional on the observable covariates. This assumption can be violated if parents seek an abortion or other medical treatments to avoid giving birth to twins. However, it was impossible to reliably predict the sex of one’s child, the likelihood of carrying twins, or the birth order of one’s offspring in ancient China. Another possible concern is that of postnatal fertility controls. However, infanticide mostly affected female offspring, which have already been excluded from our sample.

In order for our instrument to be valid, it must also satisfy the exclusion restriction assumption related to the effect of having a twin brother on the probability of receiving an education. Using twin birth at the last birth ensures that the family size changes without changing the birth orders of the non-twin children. The correlations between twin births and most of the other personal or parental characteristics could be rejected at a 0.1 significance level; the few existing exceptions, such as household size, were already important controls in the education-focused equation.

4.10 Robustness checks

Supporting evidence from the CMGPD-SC

We show that child mortality (i.e., the surviving age of siblings) does not confound the results of our main research question, namely, the existence of a linkage between human capital accumulation and sibship size in the Eight Banner regions in the mid-and-late-Qing dynasty, by using the China Multi-Generational Panel Dataset, Shuangcheng (CMGPD-SC). In Shuangcheng of Jilin province, both metropolitan and rural bannermen received state-allocated land without paying taxes or rent. They could use this land as their personal property and pass the property rights down to their descendants. These economic incentives enabled the CMGPD-SC households to register their children as early as possible. Additionally, as the population registration played an essential role in land allocation, the Shuangcheng local government updated the registers annually.

These facts suggested little evidence of under-reporting male infants and boys and made the CMGPD-SC dataset quite suitable for studying fertility and mortality in the late-Qing period. Using this sample from the CMGPD-SC and controlling for the average-surviving age of siblings to measure the intercorrelation between human capital and sibship size, we find conclusions similar to those obtained using the CMGPD-LN, as indicated in columns (1)–(3) of Table 7.Footnote 36

We show evidence that our identification strategies and method for defining the sibship size in the benchmark analysis (i.e., by counting the maximum number of brothers regardless of their current status) made the sibship size insignificantly correlated with the mean surviving age in a household when we use accurate child mortality data (see column 4). Moreover, regarding the concern that the non-elite households where educated individuals came from might have unobservables that would predict longer lifespans for its members, our results show that brothers’ surviving age does not differ significantly across the education statuses of individuals (see column 5).

Father-level estimations

In this section, the education equation is estimated with the father as the unit of analysis instead of the child, in order to check the robustness of the baseline findings by changing the estimation unit and sample. We are focusing on the ratio of educated sons as a function of total household fertility, as measured by the number of sons of each father (or his nuclear household). It is not required to include variables at the individual or cohort levels, such as birth-order effects. The covariates contain the father’s characteristics, such as the father’s position or title, the features of the extended household that the father belonged to, and the village-level characteristics. This model is estimated with both OLS and IV.

Results are shown in Table 8. The OLS and IV estimates in columns (1) and (2) suggest that, as a consequence of a unitary decrease in the number of sons, the ratio increases for the sample households which was exposed to more accessible education. Other results using a different subsample are reported in columns (3)–(7) and show a similar pattern to Tables 2 and 3 regardless of the approaches explored. This indicates that the deliberate fertility control motivated by human capital objectives was not homogenous across all households, only being present in the general population in Liaoning when the educational resources increased.

4.11 Interpreting fertility decline

We are aware of the mechanisms through which the decline in fertility rates should be identified (Guinnane 2011). These mechanisms include the decline of child mortality (which affects the supply of children), the rise of income per capita (which affects the demand for children), the rise of demand for human capital, and the opportunity costs of parents (Galor 2012).

In light of the literature (Murphy 2015), our empirical analysis was able to identify those channels which were relevant in our sample (see Appendix Table A.9). The first piece of finding is that, in line with other quantitative analyses, child mortality before the transition does not significantly contribute to the observed decline in fertility rates. Second, the inclusion of the household’s salaried income per capita captures the channel through which fertility rates change via the demand for children. The quantity-quality trade-offs remain robust when accounting for this by controlling for the level of per capita income at the time when the children are born, and we find evidence that fertility is negatively correlated with income (Strulik 2017). In an alternative analysis, we use the price of the main grain at the time of an individual’s birth to approximate the opportunity cost of raising children and find similar results. Most importantly, the demand for human capital, as proxied by the interaction between the number of Shuyuan within the county of residence and the quota for Juren titles during the schooling ages of each birth cohort, played a crucial role in determining the fertility rates, as indicated in Section 4.6.

5 Conclusion

This paper provides empirical support for one of the central elements of the UGT, which attempts to explain demographic transitions as well as economic growth over a long period of time (Galor 2011). This theory was typically investigated in the context of past fertility declines in the Western world, ascribing these declines to the increasing need for education stimulated by the industrialization process, and indicating that technological progress is the common element that encouraged both a demographic and a historical transition from Malthusian stagnation to modern growth.

Using rigorous quantitative data, we find evidence that the quantity-quality trade-off was notable among the farming population belonging to the Eight Banner System in Liaoning in the eighteenth century. This temporal pattern quantity-quality trade-off does not support evidence for other parts of China, since the sample population is drawn from a military-based society, and thus, they are not representative of China. The trade-off became salient with increased returns on investments in education and improved access to Confucian education (i.e., increased Han-style schools), all of which provided incentives for the sample households to reduce their family size and focus on human capital objectives.

We attempt to rule out two other interpretations of this negative relationship, which would contradict the rational choice theory about restricting fertility: The idea that our findings were unintended consequences of the limited household resources; and the influence of birth-order effects, which would imply that a constrained sibship size limited the individual with a higher birth order, while increasing the average educational level of the household. The historical background, along with the empirical analyses, provides evidence that fertility was deliberately restricted as an incentive to receive an education.

Our research contributes to the expanding empirical literature on the UGT by examining the relationship between cultural or institutional factors and fertility behaviors in China in the phases preceding modern economic growth.Footnote 37 The gradual increase in the fraction of households with a higher valuation for the quality of their offspring leverages the overall investment in human capital (Galor 2012). The accumulation of human capital ultimately served as a historical base to study the reasons behind the unprecedented prosperity and growth in northeastern China in the later era of the Republic of China, before the Second Sino-Japanese War (1912–1937).

Data Availability

The CMGPD-LN data that support the findings of this study are available in ICPSR with the identifier https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR27063.v10. Other materials are available at Mendeley Data, V4, doi:https://doi.org/10.17632/wvsy8mwk5t.1.

Notes

Other explanations, such as those postulated by Cervellati and Sunde (2005), focused on a unified growth model where human capital is crucial due to its association with life expectancy but not due to its link to fertility. Strulik and Weisdorf (2008) also advanced a unified growth model that does not rely on human capital accumulation as the driving force behind the demographic changes.