Abstract

Drawing on conservation of resources theory, we built and tested a theoretical model that explores how and when leader humor can impact employee bootlegging. Based on a field study using a time-lagged research design, we found that leader humor can influence employee bootlegging by fueling relational energy. Furthermore, work unit structure moderates the effect of leader humor on relational energy as well as the indirect effect of leader humor on employee bootlegging via relational energy such that these effects are stronger when the unit operates in an organic structure as opposed to a mechanistic structure. Based on these findings, the current study sheds light on both the leader humor and the bootlegging literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In today’s rapidly changing business environment, the notion that individual innovation contributes to organizational success is widely accepted (Baer & Oldham, 2006; Sacramento et al., 2013). As a result, organizations make every effort to improve employee innovative performance. Nonetheless, there is often a paradox in innovation practice: On the one hand, organizations give employees a high degree of autonomy to pursue innovative outcomes, while on the other hand, they establish a series of formal procedures and rules to ensure that employees’ innovation activities are in line with company strategies, goals, and priorities (Amabile, 1996; Kanter, 2000). In this case, when an individual’s innovation plan conflicts with the R&D strategy and thus might be rejected by the organization, he or she is likely to continue to carry out the innovation secretly if the innovation idea is expected to succeed (Mainemelis, 2010; Nemeth, 1997). This prevalent phenomenon is referred to as bootlegging, the process “by which individuals take the initiative to work on ideas that have no formal organizational support and are often hidden from the sight of senior management, but are undertaken with the aim of producing innovations that will benefit the company” (Criscuolo et al., 2014, p. 1288), and is the focus of our research. Evidence shows that more than 80% of companies have reported bootlegging within their organizations (Augsdorfer, 2012), and employees generally spend more than 10% of their working time on bootleg innovation (Augsdorfer, 2005). As a specific form of deviant behavior that takes place without formal support (Criscuolo et al., 2014; Unsworth, 2001), bootlegging may have a double-edged sword effect: On the one hand, bootlegging may produce enormous benefits to the organization if the innovative idea succeeds (Augsdorfer, 2005). On the other hand, because bootlegging requires a certain amount of time and resources, under circumstances such as a period of increased formalization (Criscuolo et al., 2014), it may undermine the efficiency and effectiveness of formal innovation projects and ultimately lead to reduced innovative performance of both employees and organizations. Given the contingent effects of bootlegging, it is important to know which factors may impact the emergence of bootlegging so that organizations can flexibly regulate the occurrence of bootlegging according to their needs.

Despite recent research interest in this area (Criscuolo et al., 2014; Globocnik, 2019; Globocnik & Salomo, 2015; Masoudnia & Szwejczewski, 2012; Nanyangwe et al., 2021), our understanding of this issue is still insufficient, and only a few studies have showed that organizational factors such as formal management practices (Globocnik & Salomo, 2015) and individual factors such as self-identification (Nanyangwe et al., 2021) can predict bootlegging. In their seminal work, Criscuolo et al. (2014) identified bootlegging as a secret, nonprogrammed, and illegitimate activity, thus highlighting the risky nature of this behavior. Specifically, bootlegging may challenge the status quo and thereby cause potential adverse consequences for bootleggers (Globocnik, 2019; Mainemelis, 2010). In addition, the threat of visible failure exposes bootleggers to the risk of personal resource loss. Therefore, employees’ willingness to take risks may predict their general attitude toward bootleg activity. Indeed, recent research has confirmed that risk propensity is positively related to employee bootlegging (Globocnik, 2019). Despite individual differences in the tendency to take or avoid risks, employees’ preference for risk activity is also influenced by contextual factors. In the workplace, since leaders often serve as role models, employees may learn from leaders’ words and deeds about what behavior is tolerated or even encouraged, which in turn, affects their risk perception in a given situation (Sitkin & Pablo, 1992). However, previous research has yet to explicitly consider how certain leadership styles influence the extent to which employees view deviation from formal innovative plans to make underground R&D efforts risky, which is key to bootlegging.

To fill this research gap, in this paper, we propose that leader humor, or leaders’ intentional use of humor to amuse their subordinates, might be particularly relevant to employee bootlegging. Previous research has identified numerous humor styles (e.g., self-enhancing humor, affiliative humor) (Martin et al., 2003), some positive and some negative (Mesmer-Magnus et al., 2012; Veselka et al., 2010). In line with Cooper et al.’s (2018) conceptualization, we view humor as an interpersonal resource that leaders use to motivate subordinates. Therefore, in this study, we mainly focus on the positive humor style. As an effective social lubricant, positive humor can help foster high-quality interpersonal relationships. By using humor, leaders actively remove social barriers associated with formal hierarchy (Cooper, 2008). This helps lessen hierarchical differences and psychological distance between leaders and their followers (Cooper, 2008; Romero & Cruthirds, 2006). These relational processes make employees feel that it is safe to experiment their ideas and to take interpersonal risks without fear of adverse outcomes (i.e., psychological safety) (Edmondson, 1999), which is critical for employees’ norm violations in pursuit of innovation. In support of this assertion, several recent studies have demonstrated that leader humor helps to create a psychologically secure atmosphere where employees feel comfortable implementing risk-taking behavior, such as voice and boundary-spanning activity (e.g., Potipiroon & Ford, 2021; Wang et al., 2022). Consequently, the first aim of this research is to investigate the relationship between leader humor and employee bootlegging.

To unlock the black box between leader humor and employee bootlegging, we draw on conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989) to investigate the mediating role of relational energy, or “a heightened level of psychological resourcefulness generated from interpersonal interactions that enhances one’s capacity to do work” (Owens et al., 2016, p. 37). As noted by Criscuolo et al. (2014), bootlegging generally occurs when an organization lacks sufficient resources to sponsor every innovative idea, so employees must rely on themselves to develop resources (such as time, energy, and materials) in pursuit of private thoughts. In a psychologically safe work environment cultivated by leader humor, there tends to be a high level of mutual trust and respect (Kahn, 1990; Wang et al., 2022), where employees believe that their leaders respect and support their personal interests, needs, and vulnerabilities (Tang et al., 2021). Hence, employees tend to view humorous leaders as supportive and inclusive and feel good and at ease around them (Potipiroon & Ford, 2021). These positive social interactions may foster the sharing and transferring of energy resources (i.e., relational energy). Indeed, previous research has shown that positive leader-follower interactions contribute to high levels of relational energy, which enables employees to exert greater effort in their work (Owens et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018). Therefore, our second aim is to examine the role of relational energy as a meaningful enabling mechanism linking leader humor to employee bootlegging.

Furthermore, bootlegging behavior does not occur in an organizational vacuum (Nanyangwe et al., 2021). Although it is employees’ decision to take underground initiatives, the framing of bootlegging as a more or less favorable behavioral option might be influenced by contextual factors (Globocnik, 2019). Previous research has shown that work environment features such as work autonomy and decision-making styles can influence employees’ creativity and innovation (Amabile, 1996; Ekvall, 1996). We therefore used the work unit structure construct to examine the contingent influence of work environments on our model. In line with COR theory, we posit that work unit structure can modify the effects of resource development (Halbesleben et al., 2014; Hobfoll et al., 2018), which ultimately influences employees’ preference for bootlegging. Thus, the third aim of this research is to determine whether work unit structure functions as a boundary condition that alters the relationship between leader humor and employee bootlegging.

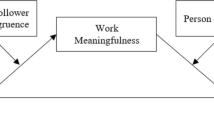

Our research makes several contributions. First, we contribute to the nascent but growing bootlegging literature by introducing leader humor as a leadership antecedent that may affect employee bootlegging. Compared with other leadership approaches, leader humor signals the acceptability of norm violations in the workplace. Employees who see leaders display humor are likely to feel more secure in the workplace and view deviating from formal innovative projects to engage in bootlegging as less risky, making leader humor particularly relevant to employee bootlegging. Thus, our research provides new insights into the role of leadership in the bootlegging phenomenon. Second, we reveal the mechanism through which leader humor influences employee bootlegging by identifying a meaningful enabling mediator (i.e., relational energy). Third, we adopt a contextual view and introduce work unit structure as a critical boundary condition for the emergence of bootlegging. Finally, we contribute to the leader humor literature by extending its individual outcomes as well as its contextual contingency. Our theoretical model is depicted in Fig. 1

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

Leader Humor, Relational Energy, and Employee Bootlegging

According to COR theory, individuals try to retain, protect, and build valuable resources, such as energy (Hobfoll, 1989). Previous research has indicated that social interactions with others can generate energy resources, which help individuals effectively cope with work demands (Atwater & Carmeli, 2009). In the organizational setting, since leaders possess more authority and higher status, they play a central role in setting the tone of the workplace and have a significant impact on employees. Therefore, interactions with leaders become a useful way for employees to develop relational energy because they tend to place more value on social interactions with their leaders. Recent research has initially confirmed that some positive leadership styles, such as leader humility (Wang et al., 2018), and spiritual leadership (Yang et al., 2019), have positive influences on employees’ relational energy.

Although both COR theory and empirical research have constructed the relationship between leadership and employee relational energy, we argue that leader humor may particularly contribute to stimulating employee relational energy. As a typical informal communication strategy, humor reflects leaders’ attempts to reduce hierarchical gaps between leaders and followers (Cooper, 2008; Wang et al., 2022). When leaders interact with their followers in a playful and humorous way, the psychological distance associated with formal hierarchy and status can be lessened, while leader-follower similarity is strengthened (Kim et al., 2016; Pundt, 2015). These relational processes help to create a psychologically safe environment where employees may feel more secure during interpersonal interactions (i.e., psychological safety; Potipiroon & Ford, 2021; Wang et al., 2022). In a psychological safety work environment cultivated by leader humor, the relationship between leaders and followers can be characterized by a high level of mutual trust and respect (Kahn, 1990; Wang et al., 2022). Such positive leader-follower interactions facilitate high-quality interpersonal exchanges (Owens et al., 2016) from which employees can generate valuable energy resources that help them actively pursue underground innovation, reflecting a high level of relational energy. Overall, as a positive resource (Lehmann-Willenbrock & Allen, 2014; Robert & Wilbanks, 2012), leader humor tends to promote the transfer of social and psychological energy (i.e., relational energy; Wang et al., 2018) by creating a psychologically safe atmosphere and improving the leader-follower relationship. Based on the above arguments, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 1: Leader humor is positively related to employee relational energy.

COR theory posits that people invest current resources to acquire a new valuable resource, and the value of this new resource depends on whether it contributes to achieving one’s goals (Halbesleben et al., 2014). For R&D workers, their primary goal is to pursue outstanding innovative performance. Although bootlegging is not formally recognized by the organization, it serves employees’ strong desire to explore private ideas that have the potential to produce groundbreaking innovations, thereby contributing to employees’ personal goals. Therefore, bootlegging might be a valuable and attractive way for R&D workers to invest their energy resources derived from leader humor (i.e., relational energy). As a target-specific energy construct (Wang et al., 2018), relational energy not only reflects the transfer of energy resources that enables employees to pursue underground activities to explore new opportunities but also conveys social cues embedded in humor that can be interpreted as leaders’ tolerance of norm violations, which may shape employees’ risk perceptions of deviant behavior (e.g., bootlegging). Therefore, we argue that employees who are relationally energized by leader humor may not only have sufficient resources to explore their private thoughts but also dare to take such actions without fear of adverse consequences. In addition, since relational energy is generated from direct leader-follower dyadic interactions, a high level of relational energy implicitly indicates that the focal employee has a good relationship with the leader. In this case, the employee may be less worried about being punished by the leader for bootlegging. Based on these theorizations, we argue that employees with more relational energy are more capable of and willing to engage in bootlegging.

In contrast, employees with less relational energy may fall into the spiral of resource losses (Hobfoll, 2001). They have difficulty meeting daily work demands and therefore have little energy and motivation to engage in bootlegging that may cause potential risks and exacerbate resource loss. Besides, a low level of relational energy implies that the employee does not have a good relationship with his or her leader and receives fewer signals of tolerance of norm violations. Under such circumstances, once bootlegging fails or is detected by the leader, it may lead to severe sanctions. Thus, employees with low relational energy are less likely to adopt an aggressive resource investment strategy, such as bootlegging.

This resource investment effect of relational energy based on COR theory has been preliminarily confirmed by other studies. For example, the works of Owens et al. (2016) and Yang et al. (2019) showed that relational energy is positively related to employees’ job performance, and the research of Atwater and Carmeli (2009) suggested that a sense of energy helps individuals participate in high-level creative work. Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Relational energy is positively related to employee bootlegging.

Based on Hypotheses 1 and 2, we further propose the mediating effect of relational energy between leader humor and employee bootlegging. According to COR theory, leader humor can fuel employee relational energy by creating a psychologically safe atmosphere and subsequently improving the leader-follower relationship. In turn, high relational energy represents a resourceful state and signals the acceptability of norm violations in the workplace, which makes employees more capable and willing to invest in bootlegging to pursue breakthrough inventions. Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 3:

Hypothesis 3: Relational energy mediates the relationship between leader humor and employee bootlegging.

The Contextual Contingence of Work Unit Structure

COR suggests that work environments play a role in resource conservation and development, incorporating the notion that contextual factors might modify the effect of resource transformation (Halbesleben et al., 2014; Hobfoll et al., 2018). Given that humor in leadership mainly functions to decrease formal hierarchy (Romero & Cruthirds, 2006), the hierarchical and structural states of the organization are likely to have some bearing on the effectiveness of leader humor. In addition, the creativity literature has found that work environments that support creativity and innovation can be characterized by open communication channels, decentralized decision-making styles, and less formal rules (Hudson & González-Gómez, in press). We therefore consider the moderating role of work unit structure (i.e., “sum total of the ways in which labor is divided into distinct tasks and coordination is achieved among them”; Mintzberg, 1979, p. 2) in our model.

Two types of structures are distinguished: mechanistic structures and organic structures (Slevin & Covin, 1997). As the epitome of Weber’s ideal bureaucracy, the mechanistic structure can be characterized by centralization, tight control, a high degree of task division and standardization, top-down communication channels, and emphasis on strict compliance with rules and procedures (Yang, 2017). Such a structure emphasizes strict compliance with organizational rules and regulations (Christensen-Salem et al., 2021). Conversely, the organic structure is characterized by decentralization, less control, wide task boundaries, open channels of communication, and few constraints from rules and procedures (Aryee et al., 2008). Based on our discussions on leader humor and bootlegging, we argue that the energizing effects of leader humor on employee bootlegging are contingent upon work unit structure such that the organic structure provides a facilitating environment, while the mechanistic structure serves as an inhibiting one.

First, when leaders interact with their employees in a humorous way, the workplace atmosphere can be energized. If such leadership exists in a mechanistic structure where communication between leaders and employees is often limited by a formal communication channel, which is usually known as a “top-down” approach (Ambrose et al., 2013), this not only reduces leaders’ opportunity to express humor but also restricts employees’ interactions with their humorous leader, thus decreasing relational energy. In contrast, in the organic structure, leaders can flexibly adopt humor strategies and increase the frequency of humorous interactions with employees. In addition, employees can respond humorously without worrying about offending their leaders. Therefore, the organic structure can maximize the power of humor and eventually increase employees’ relational energy.

Second, humor reflects leaders’ intention to reduce social distance from employees (Romero & Cruthirds, 2006). This leadership style is inherently consistent with the concept of decentralization advocated by the organic structure, which might be more easily accepted by employees due to cognitive congruence. In the mechanistic structure, strict control and highly centralized characteristics expand psychological distances and aggravate the power imbalance between leaders and employees (Aryee et al., 2008). Under such conditions, employees may regard leader humor as a façade of affability which might produce cognitive dissonance, thus weakening the positive influence of leader humor on employees’ relational energy.

Third, previous studies have shown that a weak context makes the role of leadership more prominent than a strong one (Yang, 2017). In the mechanistic structure, the strong context of institutionalization and tight control attenuates the role of leader humor. Employees are more likely to follow established rules and regulations instead of expecting leader incentives (Dragoni & Kuenzi, 2012). Correspondingly, there may be less relational energy generated from leader humor. In contrast, when leader humor displays in an organic structure, this loose and weak situation highlights the personal charm of humorous leaders and strengthens employees’ dependence on their leaders (Dragoni & Kuenzi, 2012). In this case, the influence of leader humor on employee relational energy will be enhanced. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: Work unit structure moderates the positive effect of leader humor on employee relational energy, such that the relationship is stronger when the unit has an organic structure rather than a mechanistic structure.

The Integrated Model

Building on the rationale above, we hypothesize a moderated mediation model in which work unit structure moderates the indirect effect of leader humor on employee bootlegging through relational energy. Specifically, when the team operates in a mechanistic structure, leader humor will have a weaker influence on shaping employees’ relational energy and, indirectly, on their bootlegging. In contrast, when the team operates in an organic structure, leader humor will be more appreciated by employees, which contributes to more relational energy and, subsequently, employee bootlegging. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5: Work unit structure moderates the indirect relationship between leader humor and employee bootlegging via relational energy, such that the indirect relationship is stronger when the unit has an organic structure rather than a mechanistic structure.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were recruited from six firms in Eastern China, including insurance, pharmacy, education, and training industries. Before the formal survey began, we stated the purpose of this study and the potential benefits for the companies to the managers. HR departments were asked to send internal emails to encourage employees to actively participate in the survey, and we stressed in the email that we would keep the data strictly confidential. We then distributed and collected the questionnaires with the help of HR departments. To reduce common method bias, we followed previous leader humor research to adopt a time-lagged survey method to collect data at three time points, each separated by 1 month (e.g., Cooper et al., 2018). At time 1, employees evaluated perceived leader humor and work unit structure and filled in their demographic information. At time 2, employees assessed their relational energy level, thriving at work and perceived acceptability of norm violations. At time 3, employees rated their bootlegging behavior. A total of 422 employees from 71 teams participated in the survey. After eliminating questionnaires with incomplete information and teams with fewer than three valid responses, we finally collected 335 matched and useful responses from 59 teams, yielding a response rate of 79.38%. Among the 335 employees, men accounted for 61.19%, the average age was 26.06 years (SD = 2.83), the average tenure was 3.03 years (SD = 1.10), and average tenure with the current direct supervisor was 2.16 years (SD = 0.76). Furthermore, 85.07% of the employees had obtained a bachelor’s degree or above.

Measurements

All measurements were rated on a 5-point Likert scale unless otherwise stated. The range was from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). We translated the scales from English to Chinese following the standard back-translation procedure (Brislin, 1986).

Leader Humor

Leader humor was assessed with the three-item scale developed by Cooper et al. (2018). Compared with other leader humor scales (e.g., Avolio et al., 1999), this scale does not include any contextual questions and simply measures the frequency of leaders’ humor expression, which can avoid the potential measurement bias caused by different humor norms across cultures (Niwa & Maruno, 2010). A sample item is “My manager expresses humor with me at work.” Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.861. The range for this measure was from 1 (very infrequently) to 5 (very frequently).

Relational Energy

Relational energy was assessed with the five-item scale developed by Owens et al. (2016), which has been validated in the Chinese context (Yang et al., 2019). A sample item is “I feel invigorated when I interact with my manager.” Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.900.

Work Unit Structure

Work unit structure was assessed with the seven-item scale developed by Khandwalla (1977). Based on previous studies, this variable was assessed by team members and aggregated at the team level (Yang, 2017). The items were designed as paired statements, and a sample item was “Highly structured channels of communication and highly restricted access to important operating information” vs. “Open channels of communication with important financial and operating information flowing quite freely throughout the organization.” Higher scores represent a more organic structure. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.906.

Bootlegging

Employee bootlegging was assessed with the five-item measure developed by Criscuolo et al. (2014). A sample item is “I proactively take time to work on unofficial projects to seed future official projects.” Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.885.

Control Variables

Based on previous research on leader humor and bootlegging, we controlled for several demographic variables, including employee gender, age, tenure, dyadic tenure, and education level (Romero & Cruthirds, 2006). In addition, since recent research has confirmed that leader humor signals the acceptability of norm violations at work, which motivates employees to engage in deviant behavior (Yam et al., 2018), we controlled for employees’ perceived acceptability of norm violations to establish the incremental validity of relational energy. Since Owens et al. (2016) theorized that relational energy is generated from interpersonal interactions, which is different from intrapersonal energy concepts, we further controlled for thriving at work, a self-generated energy concept, to determine whether relational energy explains the energizing effects of leader humor above and beyond thriving at work. Perceived acceptability of norm violations was measured with the five-item scale developed by Yam et al. (2018). A sample item was “To what extent you thought it acceptable for a person in your team to be improper.” The range for this measure was from 1 (not at all acceptable) to 5 (highly acceptable). Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.900. Thriving at work was assessed with the ten-item scale developed by Porath et al. (2012), including five items each for the two dimensions of learning and vitality. Sample items included “I continue to learn more and more as time goes by” (learning) and “I am looking forward to each new day” (vitality). Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.845.

Analytical Approach

We first conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) using Mplus7.4 to test the factorial validity of our measurements. After confirming the reliability and validity of the constructs, we aggregated individual responses of work unit structure to the team level. The proposed model of this research was two-level, with the predicting, mediating and dependent variables (leader humor, relational energy, and bootlegging) as individual-level constructs and the moderating variable (work unit structure) as a team-level variable. Accordingly, we employed multilevel structural equation modeling (MSEM) to test our hypotheses. Specifically, we tested the mediating hypotheses using a lower level (1-1-1) mediation model with random intercepts on the between level (Preacher et al., 2010). In this model, leader humor, relational energy, and employee bootlegging were all measured and tested at level 1 but nested in level 2. For the moderating hypotheses, we tested the cross-level interaction with a “slopes as outcomes” model, in which a random slope is predicted by the work unit structure (Preacher et al., 2016). We used the fully latent approach to conduct analyses to mitigate potential measurement bias (Cortina et al., 2021; Preacher et al., 2010). Finally, we employed the Monte Carlo method recommended by Preacher et al. (2010) to estimate the confidence intervals for the moderated indirect effects. The statistical analysis software used in this study was SPSS 22.0 and Mplus7.4.

Results

Descriptive Statistics, Correlations, and Confirmatory Factor Analyses

The means, standard deviations, correlations, and reliabilities among the variables are shown in Table 1. A significant positive correlation was found between leader humor and relational energy (r = 0.288, p < 0.01) and between relational energy and bootlegging (r = 0.305, p < 0.01), thereby providing initial support for our hypotheses.

The results of a Harman single-factor analysis showed that the unrotated first factor explained only 28.16% of the total variation, which indicated that there was no serious common method bias in the samples. The CFAs results further supported this assertion, which showed that our hypothesized four-factor model provided a good fit to the data, χ2(164) = 394.335, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.942, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.932, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.065, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.040. This model provided a better fit to the data than the alternatives we tested, including (a) a three-factor model in which leader humor and bootlegging items were specified to load onto one factor (χ2(167) = 797.588, CFI = 0.840, TLI = 0.818, RMSEA = 0.106, and SRMR = 0.083); (b) a three-factor model in which leader humor and relational energy items were specified to load onto one factor (χ2(167) = 878.557, CFI = 0.820, TLI = 0.795, RMSEA = 0.113, and SRMR = 0.095); (c) a two-factor model in which leader humor, relational energy, and work unit structure items were specified to load onto one factor (χ2(169) = 1954.007, CFI = 0.547, TLI = 0.491, RMSEA = 0.178, and SRMR = 0.198); (d) a one-factor model (χ2(170) = 2852.243, CFI = 0.320, TLI = 0.240, RMSEA = 0.217, and SRMR = 0.236). These results support the discriminant validity of our measurements.

Hypothesis Testing

Level of Analysis

Our sample was nested data, with individuals nested within teams. Since the work unit structure was a team-level variable, we assessed the interrater agreement coefficient (rwg(j)) and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC1 and ICC2) to evaluate the suitability of aggregating scores. The results indicated acceptable values (mean rwg(j) = 0.91, ranging from 0.71 to 0.98, ICC(1) = 0.29, and ICC(2) = 0.69), which justified the suitability of aggregating individual assessments of work unit structure into a team-level variable.

The results of one-way analysis of variance demonstrated that the between-group variances of relational energy and bootlegging were not significant among firms (relational energy, F (5, 329) = 2.17, p = 0.057; bootlegging, F (5, 329) = 0.58, p = 0.715); however, they were significant among teams (relational energy, F (58, 276) = 1.77, p < 0.001; bootlegging, F (58, 276) = 1.59, p < 0.01). This result implied that the variance of these two variables was mainly from teams rather than firms. Therefore, a two-level structural equation modeling approach was appropriate for data analysis. The model results are presented in Table 2.

Relational Energy as a Mediator (Hypotheses 1–3)

As shown in Table 2, leader humor had a significant positive effect on relational energy (b = 0.239, p < 0.001), and relational energy had a significant positive effect on bootlegging (b = 0.215, p < 0.001). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2 were supported. With respect to the mediation effects, we conducted a 5000-time Monte Carlo simulation, and the results suggested that the indirect effect of leader humor on bootlegging via relational energy was positive and significant (indirect effect = 0.051; 5000-time sampling; 95% CI [0.013, 0.099], excluding zero), thus supporting Hypothesis 3.

Work Unit Structure as a Moderator (Hypothesis 4)

Hypothesis 4 predicted that the work unit structure serves as a moderator in the relationship between leader humor and employee relational energy, such that the relationship is stronger when the unit operates in an organic structure as opposed to a mechanistic structure. As expected, we found a positive cross-level interaction between leader humor and work unit structure in predicting employees’ relational energy (b = 0.322, p = 0.023).

We plotted the form of interaction in Fig. 2. Simple slope analyses indicated that leader humor was significantly positively related to employee bootlegging in organic structures (b = 0.339, p < 0.001) but not significant in mechanistic structures (b = 0.139, p = 0.056) and that the difference between slopes was significant (b = 0.200, p < 0.001), thus providing support for Hypothesis 4.

Tests of Moderated Mediation Effects (Hypothesis 5)

Finally, Hypothesis 5 predicted that work unit structure moderates the indirect effect of leader humor and employee bootlegging through relational energy, such that the indirect effect is stronger when the unit operates in an organic structure as opposed to a mechanistic structure. We used the Monte-Carlo method recommended by Preacher et al. (2010) to calculate the confidence intervals for the mediated effect of leader humor on employee bootlegging via relational energy in organic and mechanistic conditions. Based on 5000 Monte Carlo replications, the results of Table 3 showed that the indirect effect of leader humor on bootlegging via relational energy is significant in an organic structure (estimate = 0.077, p < 0.01, 95% CI [0.033, 0.119], excluding zero) but not in a mechanistic structure (estimate = 0.033, p = 0.060, 95% CI [− 0.002, 0.067], including zero). The difference between the conditions was also significant (estimate = 0.043, p = 0.035, 95% CI [0.003, 0.083], excluding zero). Besides, following Hayes’s (2015) recommendation, we calculated the index of moderate mediation and the results showed that it was significant (estimate = 0.069, p = 0.035, 95% CI [0.005, 0.133], excluding zero). Thus, Hypothesis 5 was supported.

Discussion

Based on COR theory, we built and tested a theoretical model that investigates the relationship between leader humor and employee bootlegging. Through a longitudinal research design, we showed that leader humor has a positive indirect effect on employee bootlegging through relational energy. Furthermore, the work unit structure, as a contextual factor, imposes different modifications on these relationships. Specifically, these positive effects are intensified within the organic structure but neutralized within the mechanistic structure. Next, we delineate theoretical implications, practical implications and limitations that provide future directions.

Theoretical Implications

First, our research complements and extends the existing literature (constructive deviance broadly and bootlegging particularly) by applying COR to bridge linkages between leader humor, relational energy, and employee bootlegging. Previous research in this area has mainly adopted three mechanisms to explain why multiple incentives lead to constructively deviant behaviors, that is, intrinsic motivation, felt obligation, and psychological empowerment (see the recent review: Vadera et al., 2013). By applying a resource lens, we provide scholars with new insights into the mechanism through which these phenomena occur. The results support our proposition that leader humor can fuel employees’ personal resources (i.e., more relational energy), which in turn enables employees to pursue underground innovation (i.e., bootlegging). Thus, we bring fresh accents to the current literature.

Second, we also respond to Owens et al.’s (2016) call for extensive exploration of the antecedents and consequences of relational energy. As a newly developed construct, the nomological network of relational energy remains largely incomplete, and only a few studies have examined whether leadership styles such as spiritual leadership (Yang et al., 2019) and leader humility (Wang et al., 2018) are positively associated with subordinates’ relational energy. Regarding the consequences, existing studies mainly select job engagement and job performance as evaluation criteria and neglect the potential behavioral consequences (Owens et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2019). Thus, our model adds theoretical richness to the emerging literature about the antecedents and behavioral consequences of relational energy. Furthermore, our control of thriving at work (an intrapersonal energetic state) provides incremental explanatory validity to the relational energy construct, since Owens et al. (2016) theorized that relational energy generated from interpersonal interactions is different from intrapersonal energy concepts.

Third, this research helps to extend the literature on leader humor effectiveness by considering the powerful role of situational features. As Johns (2006, p. 386) noted, “The impact of context on organizational behavior is not sufficiently recognized or appreciated by researchers.” This is problematic because contextual factors may “affect the occurrence and meaning of organizational behavior as well as functional relationships between variables” (Johns, 2006, p. 386). Similarly, studies in the leadership domain display a strong trend of conducting contextualized leadership research (Dust et al., 2014; Oc, 2018). Our results suggest that leader humor effectiveness seems to be stronger in certain organizational contexts than in others. In particular, the mechanistic structure provides an inhibitory environment for leader humor, while the organic structure provides a promoting environment. Therefore, we provide more comprehensive recognition of the impacts of leader humor on employees’ affective and behavioral outcomes under different work unit structures and emphasize the necessary integration of situational features in understanding the preconditions of bootlegging. This contributes to a new horizon that underlines the situations in which leader humor may be more effective.

Finally, we extend the leader humor literature and COR theory by systematically theorizing and empirically testing leader humor as an interpersonal resource that enables subordinates to engage in proactive resource investment strategies. As stated by Hobfoll (1989, 2001), COR theory contains two central tenets: resource loss and resource gain. The resource loss tenet suggests that individuals who lack resources are more vulnerable to additional losses and therefore are motivated to prevent the further depletion of their remaining resources. Previous humor studies applying COR theory as a theoretical foundation have mainly adopted this tenet and asserted that leader humor, as an interpersonal resource, can help employees cope with work stress (e.g., Cooper et al., 2018). However, the resource gain tenet regarding humor issues is largely overlooked, leaving an incomplete picture. Our research bridges this research gap and provides a more comprehensive understanding of the social functions of leader humor.

Practical Implications

This research also has practical implications for leaders and organizations. First, the results suggest that leader humor has a significant positive effect on employee bootlegging. However, as previously mentioned, bootlegging is a double-edged sword: It may be either a boost or a barrier for the innovative performance of both employees and organizations. Given the double-edged sword effect of bootlegging, we recommend that leaders be wise in determining whether and when to use humor in the workplace. Specifically, if organizations make strategic decisions to take advantage of employee bootlegging, leaders can use humor to elicit such behaviors. In contrast, in a bootlegging-hating phase, leaders should be careful about using humor when interacting with their subordinates to avoid sending the wrong signals.

Second, since leader humor is positively related to employees’ relational energy, as suggested by Quinn et al. (2012) regarding how to cope with the “human energy crisis,” managers should take advantage of humorous communication approaches during their interactions with followers. Compared with other structural policies (e.g., paid vacation) that aim to alleviate employee stress or replenish employee energy, the leaders’ use of humor is a low-cost and high-benefit method (Cooper et al., 2018). Thus, we recommend that organizations take humor into account during leader selection and manager training (Dampier & Walton, 2013).

Third, we demonstrate that work unit structure can regulate the impacts of leader humor; more specifically, the mechanistic structure provides an inhibitory environment for leader humor, while the organic structure functions as a promoting one. This implies that leader humor is not uniformly good. For example, leaders should cautiously display humor in a bureaucratic organization since it may fall short of expectations.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations that highlight future research directions. First, although it was validated with a time-lagged sample, the causality of variables is not well addressed. To obtain reliable results, measuring all variables at all measurement points and then conducting full cross-lagged panel analyses would be ideal for future research.

Second, we adopted a unidimensional leader humor behavior scale to reduce measurement bias caused by cultural differences (Yue, 2011). However, compared with other multidimensional humor scales, it is difficult to distinguish the mechanisms of how various types of humor impact employees psychologically. Hence, future studies may develop a multidimensional leader humor scale to enrich and expand this model.

Third, although we stated that leader humor may be particularly relevant to employee bootlegging compared with other leadership behaviors, we did not prove this empirically. Further research should include several other leadership styles as control variables to show whether leader humor can predict employee bootlegging above and beyond other leadership styles (such as transformational leadership).

Finally, scholars have claimed that humor norms vary in different cultures and “the perception and appreciation of humor may be circumstantial and are culturally embedded” (Yue, 2011, p. 463). Therefore, future research can focus on the role of cultural contextual variables, such as power distance, collectivism/individualism, and traditionalism, to obtain a more accurate understanding of the leader humor phenomenon in the workplace.

References

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context: Update to the social psychology of creativity. Westview Press.

Ambrose, M. L., Schminke, M., & Mayer, D. M. (2013). Trickle-down effects of supervisor perceptions of interactional justice: A moderated mediation approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(4), 678–689. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032080

Aryee, S., Sun, L. Y., Chen, Z. X. G., & Debrah, Y. A. (2008). Abusive supervision and contextual performance: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion and the moderating role of work unit structure. Management and Organization Review, 4(3), 393–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2008.00118.x

Atwater, L., & Carmeli, A. (2009). Leader-member exchange, feelings of energy, and involvement in creative work. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(3), 264–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.07.009

Augsdorfer, P. (2005). Bootlegging and path dependency. Research Policy, 34(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2004.09.010

Augsdorfer, P. (2012). A diagnostic personality test to identify likely corporate bootleg researchers. International Journal of Innovation Management, 16(1), 125–133. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919611003532

Avolio, B. J., Howell, J. M., & Sosik, J. J. (1999). A funny thing happened on the way to the bottom line: Humor as a moderator of leadership style effects. Academy of Management Journal, 42(2), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.5465/257094

Baer, M., & Oldham, G. R. (2006). The curvilinear relation between experienced creative time pressure and creativity: Moderating effects of openness to experience and support for creativity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 963–970. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.963

Brislin, R. W. (1986). The wording and translation of research instruments. In W. J. Lonner & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Field methods in cross-cultural research. Sage.

Christensen-Salem, A., Walumbwa, F. O., Babalola, M. T., Guo, L., & Misati, E. (2021). A multilevel analysis of the relationship between ethical leadership and ostracism: The roles of relational climate, employee mindfulness, and work unit structure. Journal of Business Ethics, 171(3), 619–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04424-5

Cooper, C. (2008). Elucidating the bonds of workplace humor: A relational process model. Human Relations, 61(8), 1087–1115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726708094861

Cooper, C. D., Kong, D. T., & Crossley, C. D. (2018). Leader humor as an interpersonal resource: Integrating three theoretical perspectives. Academy of Management Journal, 61(2), 769–796. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0358

Cortina, J. M., Markell-Goldstein, H. M., Green, J. P., & Chang, Y. (2021). How are we testing interactions in latent variable models? Surging forward or fighting shy? Organizational Research Methods, 24(1), 26–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428119872531

Criscuolo, P., Salter, A., & Ter Wal, A. L. (2014). Going underground: Bootlegging and individual innovative performance. Organization Science, 25(5), 1287–1305. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2013.0856

Dampier, P., & Walton, A. (2013). White house wit, wisdom, and wisecracks. Barzipan Publishing.

Dragoni, L., & Kuenzi, M. (2012). Better understanding work unit goal orientation: Its emergence and impact under different types of work unit structure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(5), 1032–1048. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028405

Dust, S. B., Resick, C. J., & Mawritz, M. B. (2014). Transformational leadership, psychological empowerment, and the moderating role of mechanistic-organic contexts. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(3), 413–433. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1904

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

Ekvall, G. (1996). Organizational climate for creativity and innovation. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(1), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594329608414845

Globocnik, D. (2019). Taking or avoiding risk through secret innovation activities—The relationships among employees’ risk propensity, bootlegging, and management support. International Journal of Innovation Management, 23(03), 1950022. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919619500221

Globocnik, D., & Salomo, S. (2015). Do formal management practices impact the emergence of bootlegging behavior? Journal of Product Innovation Management, 32(4), 505–521. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12215

Halbesleben, J. R., Neveu, J. P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527130

Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.513

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

Hudson, S., & González-Gómez, H. V. (in press). Can impostors thrive at work? The impostor phenomenon’s role in work and career outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 128, 103601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103601

Johns, G. (2006). The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Academy of Management Review, 31(2), 386–408. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.20208687

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. https://doi.org/10.5465/256287

Kanter, R. M. (2000). When a thousand flowers bloom: Structural, collective, and social conditions for innovation in organization. In R. Swedberg (Ed.), Entrepreneurship: The social science view (pp. 167–210). Oxford University Press.

Khandwalla, P. N. (1977). Some top management styles, their context and performance. Organization and Administrative Sciences, 7(4), 21–51.

Kim, T. Y., Lee, D. R., & Wong, N. Y. S. (2016). Supervisor humor and employee outcomes: The role of social distance and affective trust in supervisor. Journal of Business and Psychology, 31(1), 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-015-9406-9

Lehmann-Willenbrock, N., & Allen, J. A. (2014). How fun are your meetings? Investigating the relationship between humor patterns in team interactions and team performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(6), 1278–1287. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038083

Mainemelis, C. (2010). Stealing fire: Creative deviance in the evolution of new ideas. Academy of Management Review, 35(4), 558–578. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.35.4.zok558

Martin, R. A., Puhlik-Doris, P., Larsen, G., Gray, J., & Weir, K. (2003). Individual differences in uses of humor and their relation to psychological well-being: Development of the Humor Styles Questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(1), 48–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00534-2

Masoudnia, Y., & Szwejczewski, M. (2012). Bootlegging in the R&D departments of high-technology firms. Research-Technology Management, 55(5), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.5437/08956308X5505070

Mesmer-Magnus, J., Glew, D. J., & Viswesvaran, C. (2012). A meta-analysis of positive humor in the workplace. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(2), 155–190. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941211199554

Mintzberg, H. (1979). The structuring of organizations. Prentice-Hall.

Nanyangwe, C. N., Wang, H., & Cui, Z. (2021). Work and innovations: The impact of self-identification on employee bootlegging behaviour. Creativity and Innovation Management, 30(4), 713–725. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12455

Nemeth, C. J. (1997). Managing innovation: When less is more. California Management Review, 40(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165922

Niwa, S., & Maruno, S. (2010). Strategic aspects of cultural schema: A key for examining how cultural values are practiced in real-life settings. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology, 4(2), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0099298

Oc, B. (2018). Contextual leadership: A systematic review of how contextual factors shape leadership and its outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1), 218–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.12.004

Owens, B. P., Baker, W. E., Sumpter, D. M., & Cameron, K. S. (2016). Relational energy at work: Implications for job engagement and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000032

Porath, C., Spreitzer, G., Gibson, C., & Garnett, F. G. (2012). Thriving at work: Toward its measurement, construct validation, and theoretical refinement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(2), 250–275. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.756

Potipiroon, W., & Ford, M. T. (2021). Does Leader humor influence employee voice? The mediating role of psychological safety and the moderating role of team humor. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 28(4), 415–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/15480518211036464

Preacher, K. J., Zhang, Z., & Zyphur, M. J. (2016). Multilevel structural equation models for assessing moderation within and across levels of analysis. Psychological Methods, 21(2), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000052

Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15(3), 209–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020141

Pundt, A. (2015). The relationship between humorous leadership and innovative behavior. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 30(8), 878–893. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-03-2013-0082

Quinn, R. W., Spreitzer, G. M., & Lam, C. F. (2012). Building a sustainable model of human energy in organizations: Exploring the critical role of resources. The Academy of Management Annals, 6(1), 337–396. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2012.676762

Robert, C., & Wilbanks, J. E. (2012). The wheel model of humor: Humor events and affect in organizations. Human Relations, 65(9), 1071–1099. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726711433133

Romero, E. J., & Cruthirds, K. W. (2006). The use of humor in the workplace. Academy of Management Perspectives, 20(2), 58–69. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2006.20591005

Sacramento, C. A., Fay, D., & West, M. A. (2013). Workplace duties or opportunities? Challenge stressors, regulatory focus, and creativity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 121(2), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2013.01.008

Sitkin, S. B., & Pablo, A. L. (1992). Reconceptualizing the determinants of risk behavior. Academy of Management Review, 17(1), 9–38. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1992.4279564

Slevin, D. P., & Covin, J. G. (1997). Strategy formation patterns, performance, and the significance of context. Journal of Management, 23(2), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(97)90043-X

Tang, S., Nadkarni, S., Wei, L., & Zhang, S. X. (2021). Balancing the yin and yang: TMT gender diversity, psychological safety, and firm ambidextrous strategic orientation in Chinese high-tech SMEs. Academy of Management Journal, 64(5), 1578–1604. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2019.0378

Unsworth, K. (2001). Unpacking creativity. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 289–297. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2001.4378025

Vadera, A. K., Pratt, M. G., & Mishra, P. (2013). Constructive deviance in organizations: Integrating and moving forward. Journal of Management, 39(5), 1221–1276. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313475816

Veselka, L., Schermer, J. A., Martin, R. A., & Vernon, P. A. (2010). Relations between humor styles and the Dark Triad traits of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(6), 772–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.01.017

Wang, L., Owens, B. P., Li, J. J., & Shi, L. (2018). Exploring the affective impact, boundary conditions, and antecedents of leader humility. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(9), 1019–1038. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000314

Wang, X., Liu, S., & Feng, W. (2022). How leader humor stimulates subordinate boundary-spanning behavior: A social information processing theory perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 956387. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.956387

Yam, K. C., Christian, M. S., Wei, W., Liao, Z., & Nai, J. (2018). The mixed blessing of leader sense of humor: Examining costs and benefits. Academy of Management Journal, 61(1), 348–369. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.1088

Yang, F. (2017). Better understanding the perceptions of organizational politics: Its impact under different types of work unit structure. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 26(2), 250–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2016.1251417

Yang, F., Liu, J., Wang, Z., & Zhang, Y. (2019). Feeling energized: A multilevel model of spiritual leadership, leader integrity, relational energy, and job performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(4), 983–997. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3713-1

Yue, X. D. (2011). The Chinese ambivalence to humor: Views from undergraduates in Hong Kong and China. Humor, 24(4), 463–480. https://doi.org/10.1515/humr.2011.026

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Qin, G., Yang, F. et al. Linking Leader Humor to Employee Bootlegging: a Resource-Based Perspective. J Bus Psychol 38, 1233–1244 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-023-09881-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-023-09881-z