Abstract

Purpose

To examine how social distance and affective trust in supervisor affect the relationships between supervisor humor and the psychological well-being and job performance of subordinates.

Design/Methodology/Approach

A survey was conducted among 322 matched supervisor–subordinate dyads in 14 South Korean organizations. Multi-level analyses were performed to test the research hypotheses, including the moderating effects.

Findings

Self-enhancing humor of supervisors was positively associated with the psychological well-being and job performance of subordinates. Affiliative humor was positively associated with psychological well-being, whereas aggressive humor was negatively associated with psychological well-being. In addition, supervisor humor was indirectly related to the psychological well-being of subordinates via social distance. Moreover, affective trust in supervisor significantly moderated the relationship between supervisor humor and social distance, such that the relationship between affiliative humor and social distance was stronger when affective trust in supervisor was high rather than low.

Implications

These findings are important in developing and refining humor theory on the responses of employees to various types of supervisor humor. Moreover, they provide practical implications for organizations. For example, organizations should note that supervisor humor may not always produce good results, and thus should encourage managers to use constructive humor. Similarly, supervisors should build a high-trust relationship with their subordinates to increase the effectiveness of their constructive humor.

Originality/Value

This study is one of the few studies that has examined the mechanism and boundary conditions of the effects of supervisor humor on employee outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The role of humor in the workplace has received increasing interest among management and social psychology researchers (Cann et al. 2009; Gkorezis et al. 2011; Martin 2007; McGee and Shevlin 2009; Mesmer-Magnus et al. 2012; Romero and Pescosolido 2008). Humor refers to any event that is shared by a person with another individual (i.e., a target), intending to amuse the target, and that the target perceives the act as intentional (Cooper 2005). Several organizations such as Southwest Airlines and Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream use humor as a business strategy to improve organizational performance (Avolio et al. 1999). Moreover, in the last several decades, scholars have assembled evidence to show that supervisor humor is positively associated with employee job performance (Avolio et al. 1999), job satisfaction and commitment (Decker 1987), psychological empowerment (Gkorezis et al. 2011), supervisor satisfaction (Decker and Rotondo 2001), and group cohesion (Cann et al. 2009).

Although current studies on humor have enhanced our understanding of the usefulness of supervisor humor at work, several important issues remain unaddressed. First, little is known about the mechanisms by which supervisor humor enhances employee outcomes. We propose that social distance is the key to understand the linkage between supervisor humor and employee outcomes. Social distance refers to the degree of intimacy or acceptance people feel toward others in social relationships (Graham 1995). Romero and Cruthirds (2006) reviewed the studies on humor and leadership effectiveness and concluded that leaders’ humor may reduce social and status distance between leaders and subordinates by enhancing similarities and reducing the importance of status. The close relationship between leader and subordinates would enhance employee work outcomes due to the better communication and understanding between the parties. Thus, we argue that supervisors who use positive and adaptive humors on their subordinates are more likely to develop close relationships with their subordinates, which subsequently improves employee outcomes. We conceptualize employee outcomes as the psychological well-being and job performance of employees, which have been frequently used as outcomes in humor research (Romero and Cruthirds 2006).

Second, given that the effects of supervisor humor on employee job performance are not consistent across studies (Mesmer-Magnus et al. 2012), understanding the conditions under which supervisor humor induces more favorable work outcomes is important (Decker 1987). To understand the conditions that enhance or mitigate the effects of supervisor humor on employee outcomes, interpersonal contexts within which employees are embedded should be considered (Decker 1987). As Wyer (2004) suggested, humor recipients evaluate the motives behind the delivery of humor, and the evaluation can affect the effectiveness of humor. One of the factors that would influence subordinate evaluations on supervisor humor is trust in supervisor. Research has indicated that trust in supervisor significantly influences how subordinates interpret the managerial behaviors of their supervisors (Cook and Wall 1980; Mayer et al. 1995). Hence, the effects of supervisor humor on employee outcomes may vary according to the level of trust in supervisor. This “social interaction” perspective offers an important and a complementary perspective on how supervisor humor is associated with employee outcomes.

To summarize, the issue of how and under what conditions supervisor humor is associated with employee outcomes (i.e., psychological well-being and job performance) should be examined. To achieve these ends, this paper examines the mediating effects of social distance and the moderating role of affective trust in supervisor on the relationship between supervisor humor and employee outcomes.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

Humor Styles

To understand the dynamic effects of humor on employee attitudes and behaviors, Martin et al. (2003) proposed four styles of humor, which are different in two dimensions. The first dimension pertains to the target of humor, which focuses on the humor on the self or others. The other dimension pertains to the content of humor, which focuses on whether the humor is benign and benevolent or potentially detrimental and injurious. The composition of these two dimensions forms four styles of humor, namely self-enhancing, affiliative, aggressive, and self-defeating humors.

Self-enhancing humor is directed toward the self and is benevolent (Martin et al. 2003). This dimension involves a humorous outlook in life despite stressful events or adversities (Kuiper et al. 2004). People who use self-enhancing humor constantly notice the funny side of an event and would cheer themselves up when they feel sad. Thus, this type is closely related to the concept of coping humor (Martin 1996), which allows an individual to use humor as a coping mechanism to minimize negative emotions and to deal effectively with adverse situations.

Affiliative humor focuses on the humor to facilitate interpersonal relationships, and to be adaptive and beneficial to others (Martin et al. 2003). Examples of affiliative humor include funny stories, jokes, and spontaneous witty banter to amuse others, to enhance social interactions, and to reduce interpersonal tensions (Lefcourt 2001). This type of humor is essentially benign and non-hostile, and can facilitate interpersonal interaction and create a positive working environment.

Different from the preceding two types of humor, aggressive humor is maladaptive and potentially detrimental to others (Martin et al. 2003). This interpersonal form of humor includes sarcasm, teasing, ridicule, derision, and disparagement to put others down (Zillman 1983). Aggressive humor may be displayed without considering its potential negative effects on others. This type of humor may hurt and alienate others, as well as impair social and interpersonal relationships (Kuiper et al. 2004).

Finally, self-defeating humor is detrimental to the self (Martin et al. 2003). This type of humor involves excessive self-disparagement and jokes about oneself to amuse others. People who use self-defeating humor ridicule themselves to gain the approval of others and to enhance their interpersonal relationships at their own expense (Kuiper et al. 2004). Self-defeating humor may bring some benefits to interpersonal relationships (e.g., reducing interpersonal tensions). However, it may also hurt the images and feelings of the focal person, which may influence his/her future interactions with others, and be detrimental to others as well as to oneself.

Supervisor Humor and Employee Outcomes

Romero and Cruthirds (2006) proposed that the four types of humor are associated with various organizational outcomes, including group cohesiveness, creativity, leadership, and organizational culture. In this study, we investigate how the humor styles of supervisors are associated with employee outcomes. However, generating a clear pattern linking supervisor self-defeating humor to employee outcomes is difficult. As previously described, self-defeating humor is used in order to amuse others and to enhance interpersonal relationships. However, self-defeating humor can also be detrimental to oneself and eventually becomes negative to others. Thus, the positive and negative effects of self-defeating humor on employee outcomes might be canceled out (Ünal 2014). As such, we have developed the research hypotheses only for self-enhancing, affiliative, and aggressive humors.

Self-enhancing Humor and Employee Psychological Well-Being and Job Performance

We propose that the use of self-enhancing humor by supervisors would be positively associated with the psychological well-being and job performance of employees. Previous humor research provided significant evidence on the benefits of self-enhancing humor on individual outcomes. For example, self-enhancing humor is positively related to psychological well-being (Martin et al. 2003) and negatively related to depression and other stress symptoms (Chen and Martin 2007) of the persons who use it. We propose that the benefits of self-enhancing humor of supervisors would be extended to employees. Although the self-enhancing humor of supervisors may not be delivered directly toward their subordinates, supervisors who adopt more self-enhancing humor could positively affect the well-being of employees by establishing a more pleasant working environment. Supervisors who use self-enhancing humor would show less anxiety and depression and develop more positive effects at work, and thus enhance the psychological well-being of employees (Ünal 2014). Moreover, a relaxing environment would elicit positive emotion (i.e., mirth) that may trigger less rigid thinking and would enhance the ability to relate and to integrate divergent material, resulting in effective management of job-related problems (Isen et al. 1987; Martin 2007).

Hypothesis 1

The self-enhancing humor of supervisors is positively associated with subordinates’ (a) psychological well-being and (b) job performance.

Affiliative Humor and Psychological Well-Being and Job Performance

The affiliative humor of supervisors is also positively related to work attitudes and behavior of their subordinates by influencing the interpersonal communication between the two parties. The benign humor of supervisors toward subordinates is a form of self-disclosure that can help supervisors develop a close relationship with their subordinates (Cooper 2008). An intimate relationship with supervisors can enhance subordinate stability in the workplace and eventually improve their psychological well-being (Bernerth et al. 2007). Moreover, the affiliative humor of supervisors can enhance effective communication with their subordinates by increasing the interpersonal attraction (Kuiper et al. 2004), which can facilitate the exchange of ideas and information between supervisors and subordinates. This exchange of ideas could support subordinates to effectively manage job-related problems. Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2

The affiliative humor of supervisors is positively associated with subordinates’ (a) psychological well-being and (b) job performance.

Aggressive Humor and Employee Psychological Well-Being and Job Performance

Different from self-enhancing and affiliative humors, aggressive humor is maladaptive and detrimental to others (Kuiper et al. 2004; Martin et al. 2003). Although the supervisor may deliver it in a friendly manner, the aggressive humor of supervisors may create negative effects among subordinates, such as intimidation and embarrassment. As time passes, the unpleasant interaction becomes a stressor for the subordinates, which negatively influences their psychological well-being (Ünal 2014). Moreover, subordinates who work with supervisors using aggressive humor may avoid interacting with their supervisors, and thus may be reluctant to obtain necessary feedback and support from their supervisors to solve their job-related problems. The aggressive humor of supervisors, such as sarcasm and teasing, may also diminish the task-specific self-efficacy of subordinates, and thus deteriorating their job performance. Hence, we predict:

Hypothesis 3

The aggressive humor of supervisors is negatively associated with subordinates’ (a) psychological well-being and (b) job performance.

Supervisor Humor and Social Distance

We posit that supervisor humor can also be indirectly related to the psychological well-being and job performance of employees through social distance, which describes a specific characteristic of interpersonal relationships between two parties. Social distance between supervisors and subordinates is defined as the degree of understanding and intimacy in their interpersonal relationships (Graen 1976; Graham 1995). A high degree of social distance between supervisor and subordinate represents a “distant” relationship with minimal mutual understanding between them. By contrast, a low social distance between supervisor and subordinate denotes a close and an intimate relationship and can be characterized by a high level of understanding and self-disclosure. Social distance between subordinates and supervisors has been an important topic in the leadership literature, and management researchers have investigated the effects of social distance on leadership effectiveness (Antonakis and Atwater 2002; Napier and Ferris 1993). Napier and Ferris (1993) proposed that perceived similarity between the supervisor–subordinate dyads, value similarity, opportunity to interact, and span of management can affect social distance between supervisors and subordinates.

We expect that supervisor humor can be significantly associated with social distance between supervisors and subordinates. According to Graham (1995), humor may reduce social distance by identifying similarities between people, such as needs and values. However, various humor styles adopted by supervisors would produce different effects on social distance. For example, self-enhancing humor may reduce the social distance between supervisor and subordinate through affect-reinforcement. Supervisors experience a positive affect when they engage in self-enhancing humor, which elicits the positive affective experience of their followers. Consequently, the positive interactions of subordinates with their supervisor reduce the hierarchical differences between them (Cooper 2008) and subordinates develop a close relationship with their supervisors.

Affiliative and aggressive humor would be related to the social distance between supervisors and subordinates through the hierarchical salience process, but in opposite directions. The affiliative humor of supervisors may decrease the salience of the formal hierarchy and the power and status differences between supervisors and subordinates because affiliative humor facilitates interpersonal relationship (Romero and Cruthirds 2006; Vinton 1989). By contrast, supervisors who express aggressive humor may further increase power difference with their subordinates. The status difference between the parties may further reinforce the hierarchical salience because aggressive humor (e.g., teasing and ridicule) is typically delivered by the more powerful party (cf. Cooper 2008). Therefore, supervisors who use aggressive humor in their interactions with subordinates further reinforce their power and status over the subordinates. Consequently, the subordinates would feel more distant and separate from their supervisors, and the perceived intimacy is weakened. Overall, we predict that

Hypothesis 4a

Self-enhancing humor is negatively associated with social distance.

Hypothesis 4b

Affiliative humor is negatively associated with social distance.

Hypothesis 4c

Aggressive humor is positively associated with social distance.

Considering that social distance between supervisor and subordinate reflects the relationship quality between the two parties, it can be significantly associated with the job performance and psychological well-being of subordinates. Napier and Ferris (1993) proposed that the closeness and quality of functional working relationships between supervisors and subordinates were significantly related to subordinates’ job performance, job satisfaction, and withdrawal. Consistent with this, Dulebohn et al. (2012) and Epitropaki and Martin (1999) found that the relationship quality of supervisors affects subordinates’ outcomes such as job satisfaction and job performance. In addition, a close relationship between supervisors and employees can make employees feel stable and pleasant with their supervisors, thus enhancing their psychological well-being (Bernerth et al. 2007), communication effectiveness, and job performance consequently. Our theoretical development so far suggests that supervisor humor is associated with the psychological well-being and job performance of subordinates indirectly as well as directly through social distance (discussed in Hypotheses 1–3). Hence, we predict the following:

Hypothesis 5

Supervisor humor (i.e., self-enhancing, affiliative, and aggressive humors) has an indirect relationship with subordinates’ psychological well-being and job performance through social distance.

The Moderating Role of Affective Trust in Supervisor

In the above hypotheses, we proposed that self-enhancing and affiliative humors are negatively related to social distance while aggressive humor is positively related to social distance. However, the effectiveness of supervisor humor depends on how employees react to or interpret the motives of the humor used (Wyer 2004). Thus, the potential effects of supervisor humor on social distance can be mitigated or enhanced by the relational context within which employees interact with their supervisors. A critical relational context that can affect employee reactions to supervisor humor or the evaluation for its motives is a trust relationship with supervisors, which can engender the benevolent interpretation of supervisor behavior. We focus on the affect-based trust relationship (hereafter, affective trust in supervisors), referring to the emotional bond and reciprocated interpersonal care and concern between subordinates and supervisors (McAllister 1995). The emotional ties linking employees and supervisors allow them to express genuine care and concern for each other’s welfare (Gong et al. 2013), thus affecting employee evaluation of supervisor humor.

We expect affective trust in supervisor to moderate the link between self-enhancing humor and social distance. Specifically, we hypothesize that the relationship between self-enhancing humor and social distance becomes stronger as affective trust in supervisor increases. When subordinates have a strong emotional bond with their supervisors, they are more likely to internalize the experience of their supervisors at work (Burke et al. 2007). Moreover, emotions can be contagious and easily transferred to others in social interactions, particularly in close relationships (Hatfield et al. 1994; Wild et al. 2001). Extrapolating from the literature, we expect the positive mood experienced by supervisors who use self-enhancing humor would easily “pass on” to their subordinates with high affective trust in supervisor. On the other hand, for subordinates with low affective trust in supervisor, their mood would be less influenced by their supervisors because their emotional bond with their supervisors is weak. In addition, positive interactions between supervisors and subordinates can help them develop a close relationship. Thus, self-enhancing humor is more likely to reduce social distance between supervisors and subordinates when the subordinates have high (rather than low) affective trust in their supervisor.

Hypothesis 6a

Affective trust in supervisor moderates the relationship between self-enhancing humor and social distance, such that the relationship between self-enhancing humor and social distance is stronger when affective trust in supervisor is high rather than low.

Affective trust in supervisor would also moderate the relationships between interpersonal forms of humor (i.e., affiliative and aggressive humors) and social distance. According to the cognitive elaboration processes, humor recipients may engage in “post-comprehension cognitive activities,” which may enhance or mitigate the effectiveness of humor of the event (Wyer 2004). These post-comprehension cognitive activities include considering the motives of the person who delivered humor. When subordinates experience reciprocated interpersonal care and concern from their supervisors, they tend to believe their supervisors are willing to do something good for them (Cook and Wall 1980; Mayer et al. 1995; Molm et al. 2000). Consequently, high affective trust in supervisor enables subordinates to interpret and react to the affiliative humor of supervisors more positively, and thus feel more intimacy with their supervisors. Affective trust also helps subordinates to react to the aggressive humor of supervisors less negatively, such that aggressive humor may not seriously damage the interactions between the subordinates and their supervisors. On the other hand, subordinates with low affective trust in supervisor are more suspicious about the motives of the interpersonal forms of humor used by their supervisors. Consequently, they may perceive that supervisors use aggressive humor to hurt others (and thus increasing social distance between the subordinates and their supervisors) and use affiliative humor to improve interpersonal relationships as a way to achieve their self-interested goals (and thus not feel strong intimacy with their supervisors who use affiliative humor). Taken together, we predict that

Hypothesis 6b

Affective trust in supervisor moderates the relationship between affiliative humor and social distance, such that the relationship between affiliative humor and social distance is stronger when affective trust in supervisor is high rather than low.

Hypothesis 6c

Affective trust in supervisor moderates the relationship between aggressive humor and social distance, such that the relationship between aggressive humor and social distance is weaker when affective trust in supervisor is high rather than low.

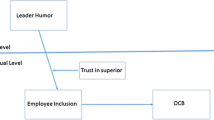

The preceding predictions suggest a first-stage moderation (Edwards and Lambert 2007), such that supervisor humor and trust in supervisor are interactively associated with social distance which, in turn, is significantly associated with psychological well-being (Hypothesis 7a) and job performance (Hypothesis 7b). The proposed first-stage moderation effects are shown in Fig. 1.

Method

Sample and Procedure

Data were collected from employees and their supervisors from 14 large organizations in South Korea. The organizations included three pharmaceutical companies, six electronic companies, one chemical company, one information technology company, and three manufacturing companies. We obtained the participation of the organizations from a list of companies with the help of the university where one of the coauthors works. The human resources manager of each company compiled lists of employees who have no subordinates and their immediate supervisors. The final list of dyads generated 478 subordinate–supervisor pairs in the target organizations, and all of them were invited to participate in the study. Participation was voluntary, and the respondents were assured of the confidentiality of their responses. The employees reported the humor styles of their immediate supervisor, trust in their supervisor, their psychological well-being, and social distance with their supervisor, whereas the supervisors reported the job performance of their subordinates. The surveys were translated into Korean according to the back-translation procedure (Brislin 1986).

Among the 352 returned subordinate–supervisor paired questionnaires, 30 were discarded because of excessive missing data from either supervisor or subordinate. The 322 participating subordinates were matched with the 52 participating supervisors. The average number of subordinates for each supervisor was 6.2 (ranging from 2 to 7). Among the subordinates, 27 % were female. The average age of the subordinates was 32.6 years (SD = 6.0), and the average organizational tenure was 6.6 years (SD = 5.2). The average number of subordinates per organization was 3618.9 (SD = 846.2). Among the supervisors, 11 % were female, the average age was 44.7 years (SD = 4.8), and the average organizational tenure was 20.1 years (SD = 5.9).

Measures

Supervisor Humor Styles

We used Martin et al.’s (2003) Humor Styles Questionnaire (HSQ) to measure four styles of supervisor humor. Sample items include “My supervisor enjoys making people laugh (affiliative humor),” “If my supervisor is feeling depressed, he/she can usually cheer him-/herself up with humor (self-enhancing humor),” “If someone makes a mistake, my supervisor will often tease them about it (aggressive humor),” and “My supervisor let people laugh at him/her or make fun at his/her expense more than he/she should” (self-defeating humor).” Subordinates were asked to assess the humor styles of their immediate supervisors on a seven-point scale (1 = “strongly disagree,” 7 = “strongly agree”).

To test how the humor style items were factored, we conducted exploratory factor analysis and used eigenvalues, factor loadings, scree plot, and alpha reliability to decide the number of subscales. Specifically, eigenvalues above 1.00 were used to decide upon the number of sub-dimensions for supervisor humor (Stevens 2002). The criterion for factor loadings was set at 0.40 because this value is acceptable in the social sciences (Joreskog and Sorbom 1993). Finally, Cronbach’s alpha was used to present evidence of internal consistency for the extracted sub-dimensions. The results indicated that the four-factor solution proposed by Martin et al. (2003) was generally appropriate. However, we deleted five items that have low loading on the factors (i.e., <0.40). These items were “My supervisor does not have to work very hard at making other people laugh, he/she seems to be a naturally humorous person”; “My supervisor does not need to be with other people to feel amused, he/she can usually find things to laugh about even when he/she is by him-/herself”; “If my supervisor is feeling sad or upset, he/she usually loses his/her sense of humor (R)”; “Letting others laugh at him/her is my supervisor’s way of keeping his/her friends and family in good spirits”; and “If my supervisor is having problems or feeling unhappy, he/she often covers it up by joking around, so that even his/her closest friends do not know how he/she really feels.” We also deleted one item with high loading on the wrong dimension: “Sometimes my supervisor thinks of something that is so funny that he/she cannot stop him-/herself from saying it, even if it is inappropriate for the situation.”

Social Distance

Social distance was measured using the six items from Graham (1995)’s study. Subordinates rated the degree to which they agree with the six items using a seven-point scale (1 = “Strongly disagree” to 7 = “Strongly agree”). Sample items were “I do not know this person very well” and “I would enjoy working with this person (R).”

Affective Trust in Supervisor

We measured trust in supervisor using the scale of McAllister (1995) to assess the affect-based trust. Subordinates were asked to assess the extent to which they agree with the five items on a seven-point scale (1 = “Strongly disagree” and 7 = “Strongly agree”). Sample items included “I can talk freely to my immediate supervisor about difficulties I am having at work and know that (s)he will want to listen” and “If I share my problems with my immediate supervisor, I know (s)he would respond constructively and caringly.”

Psychological Well-Being

Psychological well-being was measured using the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al. 1983), a 14-item scale which measured the stress experienced in the past month. Subordinates were asked to assess how frequently they experienced stress symptoms in the last month on a five-point scale (1 = “Never,” 2 = “Almost never,” 3 = “Sometimes,” 4 = “Fairly often,” and 5 = “Very often”). An example of item is “In the last month, how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly?”

Job Performance

Supervisors assessed job performance of their subordinates using the seven-item scale of Williams and Anderson (1991) to measure in-role behavior. Response options were 1 = “Never” to 5 = “Always.” Sample items were “This employee adequately completes assigned duties” and “This employee fulfills responsibilities specified in the job description.”

Control Variables

We included employees’ age, sex, and organizational tenure as the control variables in the analysis. We also controlled for tenure with supervisors because the recognition of employees of the humor styles of their supervisors and the influence of supervisor humor on employee perception require time.

Analytical Strategies

Given the multi-level nature of the data (i.e., the same supervisor assessed multiple employees in multiple companies), we conducted multi-level analyses using MLwiN (Rasbash et al. 2009). Specifically, we included an intercept-only model at the company and supervisor levels to control for any possible confounding effects of company- and supervisor-level factors on the relationships we tested. Thus, we used three-level models, with employees at level 1, supervisors at level 2, and companies at level 3. To test the indirect relationships between supervisor humor and employee outcomes via social distance, we applied a product of coefficient test recommended by MacKinnon et al. (2004). Specifically, we used the bootstrap sampling method (bootstrap sample size = 5000), which is more rigorous than traditional methods, such as the Sobel test (MacKinnon et al. 2004). Moreover, to test the first-stage moderation effect (i.e., testing whether trust in supervisor moderates the indirect relationships of supervisor humor with employee outcomes via social distance), we applied the procedure of Edwards and Lambert (2007).

Results

We conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to assess the distinctness of the variables used in this study. We used three-item parcels for measures with more than three items to achieve a better variable-to-sample size ratio (our ratio is 6.2, which is relatively low, refer to Hair et al. 1995; Hogarty et al. 2005; Nunnally 1978). Item parceling can be particularly effective when the items from a unidimensional scale are parceled, and if a research principally focuses on the relationships among latent variables instead of fully understanding the relationships among items (Little et al. 2002), which is the case for our study. We specifically parceled the items using the item-to-construct balance method (i.e., matching the highest factor loaded item to the lowest loaded item, Little et al. 2002). The results indicated that the seven-factor model [χ2 (322, 168) = 278.69, p < 0.01; root-mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.05; comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.95; Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.93] fit the data better than the best-fitting six-factor model that treats affective trust in supervisor and social distance as the same [χ2 (322, 174) = 421.63, p < 0.01; RMSEA = 0.07; CFI = 0.91; TLI = 0.88], the best-fitting five-factor model that treats affective trust in supervisor and social distance and psychological well-being and job performance as the same [χ2 (322, 179) = 544.95, p < 0.01; RMSEA = 0.08; CFI = 0.86; TLI = 0.82], and the one-factor model [χ2 (322, 192) = 1552.55, p < 0.01; RMSEA = 0.15; CFI = 0.48; TLI = 0.36]. These results support the distinctness of variables in this study.

Descriptive Results

Descriptive statistics, reliability estimates, and correlations for all of the measures are reported in Table 1. The means for affiliative and self-enhancing humors were significantly higher than that of aggressive humor (i.e., 4.69 and 4.63 vs. 3.44, mean difference = 1.25, p < 0.01 and 1.19, p < 0.01, respectively). All of the reliability estimates exceeded 0.75 with an average reliability of 0.82. The affiliative and self-enhancing humors of supervisors were positively correlated with affective trust in supervisor, but aggressive humor was negatively correlated (r = 0.34, p < 0.01; r = 0.50, p < 0.01, r = −0.31, p < 0.01, respectively).

Hypothesis 1 stated that the self-enhancing humor of supervisors would be positively associated with the (a) psychological well-being and (b) job performance of their subordinates. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, the self-enhancing humor of supervisors was positively associated with the psychological well-being (γ = 0.12, p < 0.01) and job performance (γ = 0.09, p < 0.01) of subordinates as shown in Table 2.

Hypothesis 2 predicted that the affiliative humor of supervisors would be positively associated with the (a) psychological well-being and (b) job performance of their subordinates. Model 1 in Table 2 shows that affiliative humor was positively and significantly associated with psychological well-being (γ = 0.07, p < 0.01) but not job performance (γ = 0.01, n.s.). Thus, Hypothesis 2a was supported, but Hypothesis 2b was not.

Hypothesis 3 proposed that the aggressive humor of supervisors would be negatively associated with the (a) psychological well-being and (b) job performance of their subordinates. Table 2 shows that aggressive humor was negatively and significantly associated with psychological well-being, but not significantly associated with job performance (γ = −0.07, p < 0.05; γ = 0.03, n.s., respectively). Thus, only Hypothesis 3a was supported.

Hypothesis 4 predicted that supervisor humor would be significantly associated with social distance. Consistent with this prediction, Model 1 in Table 3 shows that self-enhancing and affiliative humors were negatively associated with social distance, whereas aggressive humor was positively associated with social distance (γ = −0.37, p < 0.01; γ = −0.16, p < 0.01; γ = 0.21, p < 0.01, respectively). Thus, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

Hypothesis 5 proposed that supervisor humor has an indirect positive relationship with the psychological well-being and job performance of their subordinates via social distance. Supervisor humor was significantly related to social distance as shown above. The result of Model 2 in Table 2 indicates that social distance was negatively and significantly related to psychological well-being (γ = −0.11, p < 0.01), but not job performance (γ = −0.03, n.s.) after taking supervisor humor into account. In addition, the bootstrapping test indicated that the indirect effects of supervisor humor on psychological well-being via social distance were significant. Specifically, for self-enhancing humor, the 99 % confidence interval of the indirect effect was [0.01, 0.08], not containing zero; for affiliative humor, the 99 % confidence interval of the indirect effect was [0.001, 0.04], which excluded zero; and for aggressive humor, the 99 % confidence interval of the indirect effect was [−0.05, −0.003], which excluded zero. However, the bootstrapping test indicated that the indirect effects of supervisor humor on job performance via social distance were not significant. Thus, Hypothesis 5 was supported only for psychological well-being.

Hypothesis 6a predicted that affective trust in supervisor would moderate the relationship between self-enhancing humor and social distance, such that the relationship between self-enhancing humor and social distance is stronger when affective trust in supervisor is high rather low. Model 3 in Table 3 shows that the moderating effect of affective trust in supervisor on the relationship between self-enhancing humor and social distance was significant (γ = 0.08, p < 0.05). However, contrary to hypothesis 6a, the positive interaction term indicated that affective trust in supervisor complemented the effect of self-enhancing humor on social distance. Specifically, tests of simple slopes showed that self-enhancing humor significantly reduced social distance when affective trust in supervisor was low (simple slope =−0.28, p < 0.01), but did not play a significant role for social distance when affective trust in supervisor was high (simple slope = −0.12, n.s.) (Fig. 2).

Hypothesis 6b stated that affective trust in supervisor would moderate the relationship between affiliative humor and social distance, such that the relationship between affiliative humor and social distance is stronger when affective trust in supervisor is high rather than low. Model 3 in Table 3 shows that the interaction term between affiliative humor and trust was significant (γ = −0.19, p < 0.01). Specifically, tests of simple slopes indicated that the relationship between affiliative humor and social distance was negative and significant when affective trust in supervisor was high (simple slope = −0.31, p < 0.01), but was not significant when affective trust in supervisor was low (simple slope = 0.09, n.s.). These slopes are depicted in Fig. 3. Thus, Hypothesis 6b was supported.

Hypothesis 6c predicted that affective trust in supervisor would moderate the relationship between aggressive humor and social distance, such that the relationship between aggressive humor and social distance is weaker as affective trust in supervisor is high rather than low. Model 3 in Table 3 shows that the interaction terms between aggressive humor and affective trust in supervisor were not significant (γ = 0.06, n.s.). Thus, Hypothesis 6c was not supported.

Hypothesis 7 predicted that affective trust in supervisor would moderate the indirect relationships of supervisor humor with the psychological well-being and job performance of their subordinates via social distance, such that the indirect effect is stronger as affective trust in supervisor is high rather than low. We examined whether the first-stage moderation was significant by following the procedure of Edwards and Lambert (2007). The moderated path analytic procedures showed that the path linking affiliative humor and social distance associated with the psychological well-being of employees, which was the first stage of the indirect effect of supervisor humor on the psychological well-being of employees, significantly varied as a function of trust (99 % confidence interval = [0.01, 0.05], not containing zero). Specifically, the indirect effect of affiliative humor on psychological well-being via social distance was not significant when affective trust in supervisor was low (simple slope = 0.00, n.s.), but became significant when affective trust in supervisor was high (simple slope = 0.05, p < 0.01). These moderated indirect relationships are plotted in Fig. 4. However, other significant indirect effects of supervisor humor on employee outcomes via social distance did not significantly vary by the level of affective trust in supervisor. Thus, Hypothesis 7 was only partially supported.

Alternative Models

Notwithstanding the logic that we proposed in our hypotheses development, we discuss and examine several alternative conceptualizations of the model. For example, supervisors may possibly use more affiliative and less aggressive humor when they are socially close to their subordinates. In turn, supervisor humor affects employee outcomes. To examine this possibility, we tested the indirect effects of social distance on employee outcomes via supervisor humor. The results indicated that affiliative and aggressive humors were not significantly associated with psychological well-being (γ = 0.05, n.s.; γ = 0.05, n.s., respectively) nor job performance (γ = 0.01, n.s.; γ = 0.03, n.s., respectively). The bootstrapping test likewise indicated that the indirect effects of social distance on psychological well-being and job performance via affiliative and aggressive humors were not significant.

Second, supervisors who use adaptive humor (e.g., affiliative humor) are possibly more likely to be trusted by their subordinates (Hampes 1999; Hughes and Avey 2009). In turn, a trusting relationship would have beneficial effects on the psychological well-being and job performance of subordinates (Aryee et al. 2002). To investigate this issue, we tested the indirect effects of supervisor humor on employee outcomes via affective trust in supervisor. The bootstrapping test indicated that the indirect effects of self-enhancing humor on psychological well-being via affective trust in supervisor were significant at the 95 % confidence interval [0.003, 0.06], not containing zero. The indirect effects of aggressive humor were significant at the 99 % confidence interval [−0.03, −0.002], which excluded zero. However, the indirect effects of affiliative humor on psychological well-being and the indirect effects of all types of humor on job performance via affective trust in supervisor were not significant. In summary, although the cross-sectional nature of our data precludes a definitive test of causal ordering, our results suggest that the indirect effects of social distance on employee outcomes through supervisor humor were not significant. Furthermore, affective trust in supervisors mediates only the relationships between self-enhancing and aggressive humors and psychological well-being.

Discussion

We develop a model in which supervisor humor is related to employees’ psychological well-being and job performance directly and indirectly through social distance, and affective trust in supervisors moderates the latter relationships. Our findings suggest several conclusions. First, self-enhancing humor is positively related to psychological well-being and job performance. Second, affiliative humor is positively related to psychological well-being, whereas aggressive humor is negatively related to psychological well-being. Third, supervisor humor is indirectly related to psychological well-being through social distance. Fourth, the relationship between affiliative humor and social distance is stronger when affective trust in supervisors is high instead of low. Fifth, the relationship between self-enhancing humor and social distance is significant when affective trust in supervisors is low but is insignificant when affective trust in supervisors is high. Finally, the indirect effect of affiliative humor on psychological well-being via social distance is insignificant when affective trust in supervisors is low but becomes significant when affective trust in supervisors is high.

Theoretical Implications

These findings provide several important theoretical implications for humor research and suggested several opportunities for more in-depth research. One important result of this study was the relationships between various types of supervisor humor and employee outcomes. As expected, self-enhancing and affiliative humors were positively related to the psychological well-being of subordinates, and aggressive humor was negatively related to psychological well-being. Moreover, self-enhancing humor was positively associated with the job performance of subordinates. However, affiliative and aggressive humors were not associated with job performance. These results were consistent with the argument of Rapp (1951) that the usefulness of sense of humor depended on how carefully people applied it to the frailties of others. Our findings similarly supported and extended current studies and indicated that various humor styles differently influence mental health (Chen and Martin 2007) and job-related affective well-being (feeling about one’s job) (Ünal 2014). Moreover, our findings responded to the call from Nevo et al. (2001) that the effects of humor should be tested in different cultural contexts because cultural preferences may affect the appropriateness of the type of humor. Specifically, we demonstrated that the positive relationship between supervisor humor and the psychological well-being of subordinates, and the positive relationship between self-enhancing humor and job performance found in Western society can be generalized to South Korea, where cultural values and norms are different from those in the United States.

Next, our findings demonstrated that supervisor humor was significantly associated with social distance. Specifically, self-enhancing and affiliative humors were negatively related to social distance, but aggressive humor was positively related to social distance. Our findings supported the proposition of Graham (1995) that the humor of leaders would affect their social distance with subordinates. Moreover, the results supported that social distance mediated the relationship between supervisor humor and psychological well-being of subordinates. Showing how supervisor humor translates into employee outcomes is an important step in the development of the literature because it helps in identifying the underlying processes of the effect.

Another important implication of this study was the investigation of the boundary conditions of the effects of supervisor humor. The results indicated that affective trust in supervisor moderated the relationship between affiliative humor, social distance, and the psychological well-being of employees. Specifically, affiliative humor was significantly associated with social distance only when employees had a high level of trust in their supervisor. Moreover, the indirect effects of social distance on the relationship between affiliative humor and psychological well-being significantly varied depending on the levels of affective trust in supervisor. These results supported the propositions of Decker (1987) and Wyer (2004) that supervisor humor may have a positive effect on employee outcomes under certain circumstances, but not others. These results are important for the development and refinement of humor theory about the instances in which supervisor humor affects employee outcomes, although additional research is evidently required on this issue. However, our results indicated that affective trust in supervisor did not significantly moderate the relationship between aggressive humor and social distance. Moreover, the maladaptive nature of aggressive humor was determined to be consistently harmful to interpersonal relationship even when humor receivers have high affective trust toward their supervisors.

One of the interaction results was significant but contrary to that of our prediction. Specifically, the self-enhancing humor of supervisors has greater effect on social distance when subordinates have lower (rather than higher) affective trust in supervisor. This result suggests that the positive mood created by the self-enhancing humor of supervisors may decrease the distant feelings (i.e., social distance) of employees toward their supervisors when employees have low affective trust in supervisor. By contrast, employees with high affective trust in their leaders may no longer need to use the mood of leaders as information to determine the type of interpersonal interaction (i.e., close or distant relationship) with their leaders.

Practical Implications

Our study provided practical implications for managers and organizations. First, managers should note that humor may not always bring beneficial effects to employee outcomes. Our results highlighted the importance of encouraging managers to use more constructive humor (i.e., self-enhancing and affiliative humors) than destructive humor (i.e., aggressive humor) to improve the well-being of employees. Even if supervisors have a high sense of humor, the use of destructive humor may harm individual and organizational effectiveness or even instigate legal activities or cultural clashes. Although managers could not be realistically assumed to be uniformly successful in its implementation, they can be trained to use constructive humor (cf. Prerost 1993). Moreover, supervisors should be aware that even constructive humor can be more effective under certain situations. Our results indicated that the effects of humor styles on social distance and employee outcomes depend on the level of affective trust in supervisor. Thus, trust is the fundamental situation for humor to be effective, and supervisors should build a high-trust relationship with their subordinates to increase the effectiveness of their constructive humor.

Limitations, Strengths, and Future Studies

As with any study, our study has several limitations. First, with the exception of data on job performance, which was supervisor-rated job performance, the variables were measured by subordinate ratings, raising the concern for the common method variance. To reduce this concern, as Podsakoff et al. (2003) suggested, we used distinct questionnaire section and instructions, ordering of questions, and assurance of confidentiality. Moreover, we adopted precautions against the effects of common method bias, including high discriminant validity based on CFA results; nevertheless, their influence over the results could not be completely ruled out. One method of detecting inflated correlations caused by common method bias is examining simple correlations among all variables. As Spector (2006) noted, unless the strength of common method variance is so small as to be inconsequential, all simple correlations should be significant. Although our sample size was sufficiently large to provide a power of 0.80 to detect correlations at an alpha level of 0.05, 5 out of 28 correlations among the variables assessed by subordinates (18 %) were nonsignificant. Moreover, common method variance is less likely to affect nonlinear relationships (Crampton and Wagner 1994), and many of the significant findings derived from self-reported data involved the interaction effects and complex moderated mediation relationships rather than linear relationships. Thus, the potential response bias may not be a serious concern. Nevertheless, corroborating our findings using other measurement methods (e.g., multisource assessment for independent and dependent variables) would be useful.

Second, our data were collected from South Korea. Consequently, we are uncertain about the extent to which our findings can be generalized to employees in other cultural contexts. Furthermore, our study is the first to use the four-factor humor measures developed by Martin et al. (2003) in the South Korean context. Future studies need to perform measurement invariance tests for the humor measure in order to offer a more rigorous empirical support for such construct validation across countries and to check whether the humor measure can be legitimately used for cross-cultural comparison (Vandenberg and Lance 2000).

In addition, we do not have the information regarding whether subordinates sufficiently interacted with their supervisor to actually notice supervisor humor. However, this lack of information may not seriously affect the results because in testing the research hypotheses, we controlled for tenure with supervisors, which may reflect the frequency of the interaction between supervisors and employees and may affect employees’ recognition of the humor styles of their supervisors. Nevertheless, future research should measure and control for the interaction frequency between subordinates and supervisors, which can affect how frequent subordinates notice supervisor humor.

The limitations of this study are countered by several strengths. First, this investigation fills an important gap in the humor literature by examining how supervisor humor connects to employee outcomes. Our conceptual model was mostly supported, suggesting that this model represents a viable direction for future research. Second, we collected the data from different sources (e.g., supervisor assessment of the job performance of employees) to minimize potential common method biases. Third, the multi-level analysis separated the within- and between-supervisor variance of employee outcomes, such that error terms were not biased systematically. Fourth, the sample size was relatively large, which might provide adequate variance and relatively stable results, and enhance the generalizability of the results.

We call for future studies to develop a more comprehensive theory to clarify how and when supervisor humor positively affects employee outcomes. First, we suggest future studies to examine how the sense of humor of employees may moderate the effectiveness of supervisor humor on employee outcomes. Employees with a higher sense of humor may be more responsive and positively react to supervisor humor. Moreover, supervisor humor likely affects the employee humor. If supervisors use affiliative humor, then their subordinates may be more likely to adopt a similar humor style. In turn, this situation could strengthen mutual trust, which suggests the need to examine the effects of supervisor humor on the employee humor and subsequent employee outcomes. Such research efforts will broaden our explanatory frameworks for the effectiveness of supervisor humor on employee outcomes.

References

Antonakis, J., & Atwater, L. (2002). Leader distance: A review and a proposed theory. Leadership Quarterly, 13, 673–704. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00155-8.

Aryee, S., Budhwar, P. S., & Chen, Z. X. (2002). Trust as a mediator of the relationship between organizational justice and work outcomes: Test of a social exchange model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 267–285. doi:10.1002/job.138.

Avolio, B. J., Howell, J. M., & Sosik, J. J. (1999). A funny thing happened on the way to the bottom line: Humor as a moderator of leadership style effects. Academy of Management Journal, 42, 219–227. doi:10.2307/257094.

Bernerth, J. B., Armenakis, A. A., Field, H. S., Giles, W. F., & Walker, J. (2007). Leader–member social exchange (LMSX): Development and validation of a scale. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 28, 979–1003. doi:10.1002/job.443.

Brislin, R. W. (1986). The wording and translation of research instrument. In W. J. Lonner & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Field methods in cross-cultural research (pp. 137–164). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Burke, C. S., Sims, D. E., Lazzara, E. H., & Salas, E. (2007). Trust in leadership: A multi-level review and integration. Leadership Quarterly, 18(606–632), 2007. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.09.006.

Cann, A., Zapata, C. L., & Davis, H. B. (2009). Positive and negative styles of humor in communication: Evidence for the importance of considering both styles. Communication Quarterly, 57, 452–468. doi:10.1080/01463370903313398.

Chen, G.-H., & Martin, R. A. (2007). A comparison of humor styles, coping humor, and mental health between Chinese and Canadian university students. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research, 20, 215–234. doi:10.1515/HUMOR.2007.011.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396. doi:10.2307/2136404.

Cook, J., & Wall, T. (1980). New work attitude measures of trust, organizational commitment and personal need non-fulfillment. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 53, 39–52. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1980.tb00005.x.

Cooper, C. (2005). Just joking around? Employee humor expression as an ingratiatory behavior. Academy of Management Review, 30, 765–776. doi:10.5465/AMR.2005.18378877.

Cooper, C. (2008). Elucidating the bonds of workplace humor: A relational process model. Human Relations, 61, 1087–1115. doi:10.1177/0018726708094861.

Crampton, S. M., & Wagner, J. A. (1994). Percept-percept inflation in microorganizational research: An investigation of prevalence and effect. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 67–76. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.79.1.67.

Decker, W. H. (1987). Managerial humor and subordinate satisfaction. Social Behavior and Personality, 15, 225–232. doi:10.2224/sbp.1987.15.2.225.

Decker, W. H., & Rotondo, D. M. (2001). Relationships among gender, type of humor, and perceived leader effectiveness. Journal of Managerial Issues, 13, 450–465.

Dulebohn, J. H., Bommer, W. H., Liden, R. C., Brouer, R. L., & Ferris, G. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of leader-member exchange: Integrating the past with an eye toward the future. Journal of Management, 38, 1715–1759. doi:10.1177/0149206311415280.

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12, 1–22. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1.

Epitropaki, O., & Martin, R. (1999). The impact of relational demography on the quality of leader–member exchanges and employees’ work attitudes and well-being. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72, 237–240. doi:10.1348/096317999166635.

Gkorezis, P., Hatzithomas, L., & Petridou, E. (2011). The impact of leader’s humor on employees’ psychological empowerment: The moderating role of tenure. Journal of Managerial Issue, 23, 83–95.

Gong, Y., Kim, T.-Y., Lee, D.-R., & Zhu, J. (2013). A multilevel model of team goal orientation, information exchange, and creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 56, 827–851. doi:10.5465/amj.2011.0177.

Graen, G. B. (1976). Role making processes within complex organizations. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 1201–1245). Chicago: Rand-McNally.

Graham, E. E. (1995). The involvement of sense of humor in the development of social relationships. Communication Reports, 8, 158–169. doi:10.1080/08934219509367622.

Hair, J. F. J., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1995). Multivariate data analysis (4th ed.). Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hampes, W. P. (1999). The relationship between humor and trust. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research, 12, 253–260. doi:10.1515/humr.1999.12.3.253.

Hatfield, E., Cacioppo, J., & Rapson, R. L. (1994). Emotional contagion. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hogarty, K. Y., Hines, C. V., Kromrey, J. D., Ferron, J. M., & Mumford, K. R. (2005). The quality of factor solutions in exploratory factor analysis: The influence of sample size, communality, and overdetermination. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 65, 202–226. doi:10.1177/0013164404267287.

Hughes, L. W., & Avey, J. B. (2009). Transforming with levity: Humor, leadership, and follower attitudes. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 30, 540–562. doi:10.1108/01437730910981926.

Isen, A. M., Daubman, K. A., & Nowicki, G. P. (1987). Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 1122–1131. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.6.1122.

Joreskog, K., & Sorbom, D. (1993). LISREL 8: Structural modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kuiper, N. A., Grimshaw, M., Leite, C., & Kirsh, G. (2004). Humor is not always the best medicine: Specific components of sense of humor and psychological well-being. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research, 17, 135–168. doi:10.1515/humr.2004.002.

Lefcourt, H. M. (2001). Humor: The psychology of living buoyantly. New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 151–173. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 99–128. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4.

Martin, R. A. (1996). The Situational Humor Response Questionnaire (SHRQ) & Coping Humor Scale (CHS): A decade of research findings. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research, 9, 251–272. doi:10.1515/humr.1996.9.3-4.251.

Martin, R. A. (2007). The psychology of humor: An integrative approach. Burlington. MA: Elsevier Academic Press.

Martin, R. A., Puhlik-Doris, P., Larsen, G., Gray, J., & Weir, K. (2003). Individual differences in uses of humor and their relation to psychological well-being: Development of humor styles questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 48–75. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00534-2.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20, 709–734. doi:10.5465/AMR.1995.9508080.

McAllister, D. J. (1995). Affect-and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 24–59. doi:10.2307/256727.

McGee, E., & Shevlin, M. (2009). Effect of humor on interpersonal attraction and mate selection. Journal of Psychology, 143, 67–77. doi:10.3200/JRLP.143.1.67-77.

Mesmer-Magnus, J., Glew, D. J., & Viswesvaran, C. (2012). A meta-analysis of positive humor in the workplace. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27, 155–190. doi:10.1108/02683941211199554.

Molm, L. D., Takahashi, N., & Peterson, G. (2000). Risk and trust in social exchange: An experimental test of a classical proposition. American Journal of Sociology, 105, 1396–1427. doi:10.1086/210434.

Napier, B. J., & Ferris, G. R. (1993). Distance in organizations. Human Resource Management Review, 3, 321–357. doi:10.1016/1053-4822(93)90004-N.

Nevo, O., Nevo, B., & Yin, J. L. S. (2001). Singaporean humor: A cross-cultural, cross-gender comparison. Journal of General Psychology, 128, 143–156. doi:10.1080/00221300109598904.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879.

Prerost, F. J. (1993). A strategy to enhance humor production among elderly persons: Assisting in the management of stress. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 17, 17–24. doi:10.1300/J016v17n04_03.

Rapp, A. (1951). The origins of wit and humor. New York: E. P. Dutton.

Rasbash, J., Steele, F., Browne, W. J., & Goldstein, H. (2009). A user’s guide to MLwiN, v2.10. Bristol: Centre for Multilevel Modelling, University of Bristol.

Romero, E. J., & Cruthirds, K. W. (2006). The use of humor in the workplace. Academy of Management Perspectives, 20, 58–69. doi:10.5465/AMP.2006.20591005.

Romero, E. J., & Pescosolido, A. (2008). Humor and group effectiveness. Human Relation, 61, 395–418. doi:10.1177/0018726708088999.

Spector, P. E. (2006). Method variance in organizational research truth or urban legend? Organizational Research Methods, 9, 221–232. doi:10.1177/1094428105284955.

Stevens, J. (2002). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Ünal, Z. M. (2014). Influence of leaders’ humor styles on the employees’ job related affective well-being. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences, 4, 201–211. doi:10.6007/IJARAFMS/v4-i1/585.

Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3, 4–70. doi:10.1177/109442810031002.

Vinton, K. L. (1989). Humor in the workplace: It is more than telling jokes. Small Group Research, 20, 151–166. doi:10.1177/104649648902000202.

Wild, B., Erb, M., & Bartels, M. (2001). Are emotions contagious? Evoked emotions while viewing emotionally expressive faces: Quality, quantity, time course and gender differences. Psychiatry Research, 102, 109–124. doi:10.1016/S0165-1781(01)00225-6.

Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and task behaviors. Journal of Management, 17, 601–617. doi:10.1177/014920639101700305.

Wyer, R. S. (2004). Social comprehension and judgment: The role of situation models, narratives, and implicit theories. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Zillman, D. (1983). Disparagement humor. In P. E. McGhee & J. H. Goldstein (Eds.), Handbook of humor research (Vol. 1, pp. 85–108). New York: Springer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Korea Research Foundation Grant funded by the Korean Government (KRF-2009-32A-B00066).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, TY., Lee, DR. & Wong, N.Y.S. Supervisor Humor and Employee Outcomes: The Role of Social Distance and Affective Trust in Supervisor. J Bus Psychol 31, 125–139 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-015-9406-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-015-9406-9