Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine the effectiveness of goal-setting theory (Locke, Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 3, 157–189, 1968; Locke and Latham, 1990, A theory of goal setting and task performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; Locke and Latham, American Psychologist, 57, 705–717, 2002) within a diversity training context to enhance training outcomes. In particular, the training focused on an understudied group—gay men and lesbians—and examined both the short- and long-term outcomes associated with diversity training.

Design/Methodology/Approach

Using experimental methods in a field setting, participants (college students) were randomly assigned to a 2(goal-setting condition: self-set goals and no goals) × 2(mentor goal condition: mentor goals and no mentor goals) factorial design, where behavioral and attitudinal data were collected at two points in time: 3 months and 8 months subsequent to training.

Findings

Participants who developed sexual orientation supportive goals reported more supportive behaviors and attitudes toward gay and lesbian individuals than those who did not. Sexual orientation supportive behaviors mediated the relationship between goal-setting and sexual orientation attitudes.

Implications

The pattern of results suggests that time was the key for participants to meet the goals that were set during the diversity training. Both behaviors and attitudes were influenced by the goal setting at 8 months, but not after 3 months. This study demonstrates the importance of measuring both behaviors and attitudes in assessing diversity training.

Originality/Value

This is one of the first studies to integrate goal-setting theory (Locke and Latham, 1990, A theory of goal setting and task performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; Locke and Latham, American Psychologist, 57, 705–717, 2002) into the area of diversity training in an experimental field setting. We used a longitudinal design, addressing limitations of past research that usually examine short-term reactions to diversity training.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Evidence clearly shows that diversity within university and college campuses is a modern day reality (Bell 2007; Gurin et al. 2004; Hurtado 2005). As grounds for developing future employees and leaders, universities and colleges are important settings to examine successful diversity management initiatives. Importantly, organizations are paying considerable attention to diversity in educational settings. For example, many Fortune 500 organizations have publicly recognized the importance of educating and training university students on the skills and abilities to interact with individuals from different backgrounds and cultures (Clark 2003; Segal 2003).

One popular approach to achieving these ideals has been diversity-training programs, which have become the standard for many universities (e.g., University of California, Colorado State University, Duke University, and University of Chicago) and organizations (e.g., DaimlerChrysler, IBM, Hyatt Hotels and Resorts). For example, as a part of diversity-training program, Syracuse University required all incoming freshman to read a book about racism and held a diversity discussion panel during the orientation week (Bell 2007). These trends are mirrored in organizational contexts; in fact, a recent survey found that up to 79 % of organizations indicated that they use some form of diversity training (Galvin 2003).

Despite the ubiquity of diversity training in educational and organizational settings, empirical research examining factors that contribute to its effectiveness is sparse (Holladay and Quinones 2008; Kalev et al. 2006; Roberson et al. 2001; Weaver and Dixon-Kheir 2002). Therefore, there is a great research need to establish what can be done to increase the effectiveness of diversity training. This study attempts to address this dearth in the literature by examining two structures that might be implemented within the training context to enhance training outcomes in an educational setting.

First, goal-setting initiatives (Locke 1968; Locke and Latham 1990, 2002) might provide structure to diversity training. Goal-setting theory proposes that conscious ideas regulate individuals’ actions and therefore, setting goals motivates individuals (Locke and Latham 2002). In training contexts, Latham (1997) argued that setting specific goals after completing training influences trainees to transfer what they learned during training to their job. Very little research, however, has examined the influence of self-set goals on diversity-training outcomes (Roberson et al. 2009). Second, we contend that diversity-training effectiveness is influenced by the participation of mentors. Diversity training might be more effective if trainees are provided with reinforcement and modeling outside of the training session (Goldstein and Ford 2002; Rynes and Rosen 1995). To evaluate the effectiveness of self-set goal setting and mentor training on diversity-training outcomes, we examined both attitudes and behaviors as a function of goal-setting and mentor goal setting. We focus on these two variables because there is very little research that examines both attitudes and behaviors (Bell and Kravitz 2008; Noe 1999; Roberson et al. 2009).

In this research, we focus on diversity training toward those who are gay and lesbian. It is estimated that people who are gay or lesbian may comprise up to 10 % of the population but are nonetheless among the most negatively stereotyped and stigmatized of groups in our society (Gonsiorek and Weinrich 1991; Haddock et al. 1993; Herek 1994, 2000). Although there are state and local anti-discrimination laws that protect sexual orientation diversity and 470 Fortune 500 companies provide non-discrimination protection for their gay and lesbian employees (Lazin 2007), sexual orientation is not protected at the federal level. The Civil Rights Act prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin but not sexual orientation. In fact, discrimination against gay and lesbian individuals is still apparent in many universities (Horn et al. 2008; Morrison et al. 2009; Whitley et al. 2011) and organizations (i.e., Friskopp and Silverstein 1996; Hebl et al. 2002; Ragins et al. 2007). Thus, the purpose of this research was to examine attitudes and self-reported behaviors toward gay and lesbian individuals as a function of self-set goal setting and mentor goal setting in a diversity-training context.

Goal-Setting Within Diversity Training

One tool that may be particularly useful for enhancing diversity-training effectiveness is self-set goal setting. The training literature points to the importance of transfer strategies, such as goal setting, for trainees to transfer or use what they learned in training well after the conclusion of the training program (e.g., Baldwin and Ford 1988; Burke and Hutchins 2007; Cheng and Ho 2001; Ford and Weissbein 1997; Latham 1997; Roberson et al. 2009; Salas and Cannon-Bowers 2001). Latham (1997) proposed that goal setting is a transfer strategy that increases transfer behavior by enhancing the effects of the training.

According to goal-setting theory (Locke and Latham 1990), goals have two major functions: First, they are the basis for motivation, and second, they direct behavior. Goals are intentions that guide behavior and influence performance through four mechanisms (Locke and Latham 2002): (1) Goals direct attention and effort toward goal-relevant behaviors, (2) goals have an energizing function in that high-level goals lead to greater effort than low-level goals, 3) goals affect persistence in that individuals tend to prolong efforts on challenging goals, and 4) goals affect behavior “indirectly by leading to the arousal, discovery, and/or use of task-relevant knowledge and strategies” (Wood and Locke 1990, p. 712).

Empirical research has shown the positive results of goal setting on post-training outcomes. In a seminal study, Wexley and Nemeroff (1975) examined the effectiveness of goal setting on positive transfer of training and found that employees who were assigned to a goal-setting condition at the end of a 2-day workshop on leadership and interpersonal skills exhibited greater transfer of the learned material on the job (measured 2 months post-training) than did the participants in the control group. Similarly, Wexley and Baldwin (1986) found that setting goals, whether assigned or self-set, resulted in higher improvements of time management skills (measured 2 months post-training) than no goal setting after a time management training session. Furthermore, goal setting has been shown to result in long-term training outcomes. In a study of safety training in an applied setting, setting goals for safety during training led to significant improvements in observed worker use of safe procedures 9 months later (Reber and Wallin 1984).

Building on this line of research, we argue that self-set goal setting is particularly relevant to diversity training in that it can provide trainees with tangible objectives and clarify the behaviors and attitudes that they need to personally adopt to meet the objectives that they have set. Some examples of goals related to sexual orientation diversity might include refraining from using derogatory words when talking about or to gay men and lesbians, attending a gay and lesbian alliance meeting, and/or reading a book about gay and lesbian issues. Such goals related to sexual orientation diversity might not only lead individuals to engage in supportive behaviors but they might also create more expansive thought and attitudinal patterns that are supportive and accepting of gay and lesbian individuals.

In addition, setting goals can lead to long-term effects on attitudes and behaviors because goals energize performance by motivating “individuals’ to persist in their activities through time” (Locke and Latham 1990, p. 94). Thus, we believe that self-set goal setting helps individuals identify and set attainable goals, and that achieving these goals might result in more general and overall improvement in attitudes and behaviors displayed toward those who are gay and lesbian. In this study, we examined both the short- and long-term outcomes associated with self-set goal setting and mentor goal setting in a diversity-training context. In fact, we examined the effects of goal setting and mentor goal setting at two different time points across an 8-month time period. Therefore, we hypothesized

Hypothesis 1

Individuals who set gay and lesbian supportive goals will report more positive behaviors (1a) and positive attitudes (1b) toward gay and lesbian individuals 3 months post-training than individuals who do not set goals.

Hypothesis 2

Individuals who set gay and lesbian supportive goals will report more positive behaviors (2a) and positive attitudes (2b) toward gay and lesbian individuals 8 months post-training than individuals who do not set goals.

Mentor Support

The educational literature points to the importance of mentors—individuals who have influence and give advice and support—in students’ adjustment into campus life (Jacobi 1991; Fagenson 1989; Noe 1988). In fact, colleges and universities have implemented formal mentoring programs for undergraduate students with the objective of improving students’ levels of academic achievement, reducing attrition, increasing the prospects of graduate school, and to assist new students adapt to their institutions (Bernier et al. 2005; Jacobi 1991). In organizational settings, mentored individuals report more job satisfaction, career mobility, and recognition than those without mentors (Chao et al. 1992; Eby 1997; Fagenson 1989). Therefore, a second tool that may also enhance the effectiveness of diversity training involves mentor self-set goal setting.

The training literature suggests the importance of support from individuals with influence and higher ranking (Goldstein and Ford 2002; Quiñones and Ehrenstein 1997; Smith-Jentsch et al. 2001). In fact, researchers have stated that top management and supervisor support may be critical to achieving effective diversity training (Chrobot-Mason and Quiñones 2002); however, this has not yet been empirically tested. In one relevant correlational study, Rynes and Rosen (1995) found that across a number of organizations, leader support was the single most important predictor of both the adoption and success of diversity training. Others suggest that leader and mentor beliefs are critical determinants of organizational practices (Dutton and Ashford 1993).

Relational cultural theory provided a theoretical framework for explaining how mentors’ influence might influence attitudes and behaviors (Fletcher and Ragins 2007). According to relational culture theory, mentors are a source of influence because they provide an opportunity for assistance, feedback, and psychosocial support. Consistent with relational cultural theory, research has found that mentors are a source of formal influence and that mentees do rely on their mentors for both technical and psychosocial support (Eby and Lockwood 2005; Kleinman et al. 2001, 2002).

Thus, from a rational cultural theory perspective, having mentors self-set goals to support mentees’ gay and lesbian supportive goals should lead to positive behaviors and attitudes toward gay and lesbian individuals, because mentors are a source of important influence. Without the buy-in from those with influence, goals developed during diversity training may not be modeled, reinforced, or rewarded. Hence, mentor support through self-set goals may be key to the effectiveness of diversity training. As such, we predicted:

Hypothesis 3

Individuals with mentors who set gay and lesbian supportive goals will report more positive behaviors (3a) and positive attitudes (3b) toward gay and lesbian individuals 3 months post-training than when their mentors do not set supportive goals.

Hypothesis 4

Individuals with mentors who set gay and lesbian supportive goals will report more positive behaviors (4a) and positive attitudes (4b) toward gay and lesbian individuals 8 months post-training than when their mentors do not set supportive goals.

It is also possible that the most effective diversity training may occur when both individuals and their mentors self-set goals. Bell (2007) proposed that support from the top, regardless of whether its top management or just supervisors, can be critical because diversity supportive behaviors from individuals with influence send a signal to trainees of what are appropriate attitudes and behaviors. Having mentors participate by setting goals that support and facilitate mentees’ goals may influence participants to take their own goals more seriously and follow through on them. Therefore, we anticipated that the most positive attitudes and behaviors in trainees will occur when both trainees and mentors set goals. That is, we hypothesized an additive effect of having both trainees and their mentors set goals.

Hypothesis 5

The positive effect of individual supportive goals on reported behaviors (5a) and attitudes (5b) will be larger when their mentors also set supportive goals than when their mentors do not set supportive goals 3 months post-training.

Hypothesis 6

The positive effect of individual supportive goals on reported behaviors (6a) and attitudes (6b) will be larger when their mentors also set supportive goals than when their mentors do not set supportive goals 8 months post-training.

Mediating Effect of Behavior on Goal Setting and Attitudes

Cognitive dissonance theory proposes that when people behave inconsistently with their attitudes, people can change their attitudes to match their behaviors or they can change their behaviors to match their attitudes (Festinger 1957; Festinger and Carlsmith 1959). This need for a change is a result of a tendency for individuals to seek consistency among their attitudes and behaviors. When there is an inconsistency, then there is dissonance, which leads to feelings that something must change to eliminate the dissonance. In a typical dissonance paradigm, participants are instructed to behave in ways that are inconsistent with their private attitudes, which then influences their attitudes in the direction of that behavior to reduce the dissonance (i.e., reconcile their attitudes with their behavior; Festinger and Carlsmith 1959).

Because goal-setting theory focuses on actions and behaviors, a goal-setting approach to diversity training can influence behaviors. Self-set goals are intended behavior, and if individuals have goals that require engaging in behaviors that are counter-attitudinal, then individuals’ behaviors might influence their attitudes to reduce dissonance. In other words, if a person behaves inconsistently with their attitude, then cognitive dissonance triggers a search for positive aspects of the target of the behavior. For example, if an individual holds negative attitudes toward GLBT individuals, but then sets a goal to refrain from laughing at gay and lesbian jokes, this individual is behaving inconsistently with their attitudes, which creates dissonance. Having preformed self-set goal-oriented behaviors (i.e., not laughing at a gay joke), the behaviors might influence attitude so that it matches their behavior—decreasing negative attitudes towards GLBT individuals. Thus, the focus of diversity training could be on behaviors that might ultimately influence attitudes (Chrobot-Mason and Quiñones 2002; Noe 1999).

Cognitive dissonance theory proposes that attitudes are influenced by behaviors that conflict with their attitudes (Festinger 1957; Festinger and Carlsmith 1959). In such situations, their attitudes might be influenced by their behaviors. Because participants will make goals in which they engage in more GLBT supportive behaviors, students’ attitudes might be influenced by their behaviors. Therefore, we hypothesized that positive GLBT attitudes might be because of the supportive behaviors that individuals engage in. Thus, individuals’ ratings of their GLBT supportive behaviors will account for the effect of time; simply, the change in attitude ratings from their initial ratings to 8-month post-training. Formally,

Hypothesis 7

Individuals’ reported supportive behaviors toward GLBT individuals will mediate the relationship between self-set goal setting and long-term GLBT supportive attitudes, such that goal setting will lead to greater supportive behaviors, which will lead to greater supportive attitudes than when individual do not set goals.

Method

Sample and Data Collection

Undergraduate students at a small American southern university participated in this study from the start of a school year (August) through the end of the school year (April). We utilized an existing annual diversity-training program as a field setting to test the effectiveness of a goal-setting strategy. Students were randomly assigned to a 2(goal-setting condition: self-set goals and no goals) × 2(mentor goal condition: mentor goals and no mentor goals) factorial design, where behavioral and attitudinal data were collected at two points in time: 3 months and 8 months subsequent to training. To allow students enough time to engage in the goals they developed during the diversity training, we measured their attitudes and behaviors related to acceptance of sexual orientation diversity 3 months post-training. To assess long-term effects of the goal-setting and mentor training, students completed the measures 8 months post-training. With approval from the institutional review board, students provided their e-mail addresses for the purpose of tracking their responses over time, but were ensured that the data would be kept in confidence.

During the orientation, 114 upper-class student-mentors and approximately 500 incoming students participated. Students attended their required 1.5-h diversity training during orientation week in which we experimentally implemented a goal-training module. The training was developed by members of multiple student campus groups and involved discussions of multiple stigmatized identities: African-American, Asian-American, Hispanic-American, Arab-American, and gay men and lesbian women. The training involved the sharing of personal experiences (i.e., cases)—senior students shared personal stories in which they faced some challenge related to their identity while a student at the university. One out of the five stories was about a homosexual student.

At the beginning of the training, before the cases were presented, we randomly assigned half of the students to participate in a “Diversity-Training Activity” in which they were asked to develop a “personalized contract.” First, we defined a “personalized contract” as “a tool that individuals use to set goals about changes that they would like to make.” Furthermore, we provided students with some guidelines to help facilitate the attainment of their goals, namely, we instructed them to set goals that are specific, challenging, attainable, and personal. Then, we instructed the students to focus on how they might maximally respect and appreciate diversity in sexual orientation. Examples of goals are “I will try not to use the word ‘gay’ in the derogatory way,” “I will not laugh at jokes about homosexuality,” and “I will learn about a famous homosexual individual.” The remaining half of the students did not participate in the goal-setting exercise. The students’ goals were transcribed and the researchers reviewed the goals as a manipulation check to ensure that the students who were included in the analyses did in fact develop goals that were related to supportive behaviors toward sexual orientation diversity. Students developed an average of 3.1 (SD = 1.3) goals.

Half of the upper-class student-mentors, who are assigned to provide guidance and mentorship for incoming students during the course of the students’ first year of college, were also randomly assigned to complete contracts identifying achievable ways in which they could reinforce diversity initiatives with respect to the new students who they would be advising. All incoming students were assigned a mentor by the university, and the mentors were randomly assigned to a group of four to five incoming students. The role of the mentor was to meet with students and help students orient to their new environment and attend social functions with the students. Examples of such goals are “I will talk to advisees about gay and lesbian issues,” “I will invite advisees to attend a gay and lesbian meeting,” and “I will not laugh at jokes about homosexuality.” All students completed a measure of attitudes toward sexual orientation diversity and behaviors related to acceptance of sexual orientation diversity.

Three months post-training (at the end of the fall semester), we measured attitudes toward sexual orientation diversity and behaviors related to acceptance of sexual orientation diversity (e.g., “Been friends with a gay man or lesbian”) from 79 respondents who participated in the diversity-training and the goal-setting manipulation. We used both the online questionnaire sent by e-mail and the paper version distributed by research assistants.

Near the end of the academic year, 8 months post-training, we assessed long-term impacts of the training and the goal-setting manipulation. This final survey assessed attitudes and behaviors from 158 respondents who participated in the diversity-training and the goal-setting manipulation. The increase in response rate was because of having research assistants post signs at the dormitories with the Website information for the online survey. These data were also collected through e-mail and by having assistants solicit participants on campus.

Measures

Attitudes Toward Sexual Orientation Diversity

We used the short version of the Attitudes Toward Lesbians and Gay Men (ATLG) Scale to measure attitudes toward gay men and women (Herek 1994). Participants made their ratings on five items using a 7-point Likert-type scale, anchored by 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). These items are “Lesbians just can’t fit into our society,” “I think male homosexuals are disgusting,” “Female homosexuality is a threat to many of our basic social institutions,” and “Male homosexuality is merely a different kind of lifestyle that should not be condemned” (reversed item), and “Homosexual behavior between two men is just plain wrong.” The alpha coefficients for the ATLG scale at both time points (3 months and 8 months post-training) were .88 and .90, respectively. A principle factor analysis with a varimax rotation revealed one meaningful factor for each of the two time point measures.

Sexual Orientation Diversity Supportive Behaviors

Because of the dearth of research on sexual orientation diversity, we constructed a scale to measure behaviors that indicate support for sexual orientation diversity in the university context. The developers of the diversity-training session served as subject matter experts; therefore, there was no overlap between the students who helped create the measure and the students who served as participants. The behavioral measure was intended to capture a count of relevant behaviors in the university context that were expected to appear in the specific goals set by the students during the training session. Example items are “Been to a gay or lesbian bar, social club, party, or march,” “Laughed at a ‘queer’ joke” (reversed item), “Been friends with a gay man or lesbian,” “Interacted with individuals of different sexualities,” and “Discouraged others from using derogatory terms to refer to gay and lesbian individuals.”

Participants made their ratings on ten items using a 7-point frequency scale, anchored by 1 (never) to 7 (all the time). Thus, the measure was the total frequency of behaviors. The alpha coefficients for behavioral scale .76 for the 3-month post-training time point and .81 for the 8-month post-training time point. A principle factor analysis with a varimax rotation revealed one meaningful factor for both time points, and therefore, we were justified to use all ten items as one measure for the 3 and 8 months time points.

Manipulation Check

To ensure that participants did set goals in the goal-setting condition, the goals developed by the participants and mentors were collected at the end of the diversity training. We recorded the goals and the number of goals per participant. Participants who did not complete goals were not included in the analyses.

Three trained coders read all the goals and coded how “proactive” the goals were (i.e., did the participant set goals in which they would actively engage in supportive behaviors toward gay and lesbian individuals?) using a scale of 1 (not at all proactive) to 5 (very proactive). That is, the raters coded how behaviorally oriented the goals were to engage in supportive behaviors toward gay and lesbian individuals. The coders rated each participant’s set of goals using this one item. As such, we used a two-way random effects model to examine the reliability of the coders. The interrater reliability or intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC1) was .91 and the group mean reliability (ICC2) was .96, thereby suggesting high interrater reliability and justification for averaging the coders’ ratings.

Results

Comparing Respondents Versus Non-Respondents

In light of our response rates at the 3- and 8-month time points, we examined differences between the respondent and non-respondents on demographic variables that were collected during the diversity training. We conducted a multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA) with response type (1 = yes, 2 = no) as the independent variable and gender, age, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and academic major as the dependent variables. The results showed no significant differences for gender, F(1, 475) = .09, p > .05, age, F(1, 475) = 1.52, p > .05, ethnicity, F(1, 475) = .03, p > .05, sexual orientation, F(1, 475) = .09, p > .05, and academic major, F(1, 475) = .22, p > .05. Thus, there were no differences for the demographic variables between students who did participate and students who did not participate at the 3- and 8-month periods.

Three-Months Post-Training

We conducted a 2 (goal-setting condition: self-set goals and no goals) × 2 (mentor goal condition: mentor self-set goals and no mentor goals) MANOVA for each time point with the reported sexual orientation diversity supportive behaviors and attitudes toward sexual orientation diversity as the dependent variables. Descriptive statistics, reliability coefficients, and intercorrelations for the attitudinal and behavioral variables are reported in Table 1.

Sexual Orientation Diversity Supportive Behaviors

The results from a MANOVA revealed a significant effect for student goal condition on sexual orientation diversity supportive behaviors, F(1, 75) = 5.18, p < .05, η 2 = .065, such that students who set goals were more likely to report positive behaviors (M = 38.45, SD = 8.31) than were students who did not set goals (M = 34.42, SD = 8.08), thereby supporting Hypothesis 1a. The main effect of mentor goal condition was not significant, F(1, 75) = .26, p > .05, η 2 = .017, not supporting Hypothesis 3a. The interaction between student goal-setting and mentor goal setting was not significant, F(1, 75) = .03, p > .05, η 2 = .001, not supporting Hypothesis 5a.

Attitudes Toward Sexual Orientation Diversity

The results from a MANOVA did not reveal significant main effects for student goal condition on the 3 months post-training attitudes toward sexual orientation diversity, F(1, 75) = .03, p > .05, η 2 = .001, and mentor goal condition, F(1, 75) = 1.04, p > .05, η 2 = .001, thereby not supporting Hypotheses 1b and3b, respectively. Furthermore, the interaction between student goal condition and mentor goal condition on attitude was not significant, F(1, 75) = 2.33, p > .05, η 2 = .03. Thus, Hypothesis 5b was not supported.

Eight Months Post-Training

Sexual Orientation Diversity Supportive Behaviors

We conducted a 2(goal-setting condition: self-set goals and no goals) × 2(mentor goal condition: mentor self-set goals and no mentor goals) MANOVA with the reported sexual orientation diversity supportive behaviors and attitudes toward sexual orientation diversity 8 months post-training as the dependent variables. The results from a MANOVA revealed a significant effect for student goal condition on sexual orientation diversity supportive behaviors, F(1, 154) = 4.18, p < .05, η2 = .03, such that students who set goals were more likely to report positive behaviors (M = 40.44, SD = 10.43) than were students who did not set goals (M = 36.42, SD = 10.17), supporting Hypothesis 2a. The results revealed a significant effect for mentor goal condition on sexual orientation diversity supportive behaviors, F(1, 154) = 4.27, p < .05, η2 = .03, such that students who had mentors set goals were more likely to report positive behaviors (M = 39.46, SD = 10.45) than did students who did not have mentors set goals (M = 35.3, SD = 9.95), supporting Hypothesis 4a. The interaction between student goal condition and mentor goal condition on attitude was not significant, F(1, 154) = 1.04, p > .05, not supporting Hypothesis 6a.

Attitudes Toward Sexual Orientation Diversity

The results from a MANOVA revealed a significant main effect for student goal condition, F(1, 154) = 4.58, p < .05, η2 = .03, such that students who set goals were more likely to report more positive attitudes (M = 6.33, SD = .98) than did students who did not set goals (M = 5.73, SD = 1.41), supporting Hypothesis 2b. There was a significant effect for mentor goal condition on attitudes, F(1, 154) = 3.95, p < .05, η2 = .03, such that students who had mentors set goals were more likely to report more positive attitudes (M = 6.14, SD = 1.20) than did students who did not have mentors set goals (M = 5.69, SD = 1.38), supporting Hypothesis 4b. The interaction between student goal condition and mentor goal condition on attitude was not significant, F(1, 154) = 1.37, p > .05, disconfirming Hypothesis 6b. A summary of the analyses is provided in Table 2.

Mediating Effect of Behavior on the Goal-Setting and Attitudes Relationship

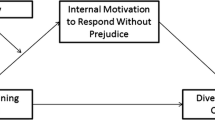

Using Preacher and Hayes’s (2008) tests of the indirect effect, we examined Hypothesis 7 (student goal setting → 3-month GLBT supportive behaviors → 8-month GLBT supportive attitudes; Fig. 1). In this mediation test, the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable is tested with and without the addition of the mediator, and the indirect effect test addresses whether the total effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable is significantly reduced with the addition of the proposed mediator to the model. Preacher and Hayes’s (2008) Sobel test and bootstrapped formula were used to test the indirect effect with a 95 % confidence interval.

The results for Hypothesis 7 showed that student goal setting had a significant positive relationship with the reported 3-month GLBT supportive behaviors (β = .45, p < .05) and the reported 3-month GLBT supportive behaviors had a significant positive relationship with the 8-month GLBT supportive attitudes (β = .61, p < .05). The direct effect for student goal setting to the 8-month GLBT supportive attitudes (β = .26, p < .05) was reduced with the mediator in the model (β = −.02, p > .05) and this reduction (indirect effect) was significant, Z = 2.03, p < .05, with a statistically significant 95 % confidence interval (.036–1.32). The results suggest that the participants who developed goals reported more supportive behaviors 3 months post-training, which led to greater supportive attitudes 8 months post-training, thereby supporting Hypothesis 7.

Exploratory Analyses

For exploratory reasons, we examined the correlations between the two measures of the reported behaviors and attitudes with the quantity and quality ratings of the goals. The mean score of the rating of the goals was 3.21 (SD = 1.22). The average number of goals developed was 3.08 (SD = 1.31), ranging from 1 to 5 goals. We correlated the quantity and the ratings of the goals with the four outcomes: 3- and 8-month GLBT supportive attitudes and reported behaviors. The quantity of goals was significantly related to 8-month GLBT supportive behavior (r = .30, p < .05).

The ratings of the goals were significantly related to the 3-month GLBT supportive attitudes (r = .43, p < .05), 3-month supported behaviors (r = .45, p < .05), and 8-month supported behaviors (r = .42, p < .05). Although, not significant, the correlation between the ratings of the goals and the 8-month GLBT supportive attitudes was in the expected direction (r = .14, n.s.). Thus, the students who set more proactive or behaviorally oriented goals reported more supportive attitudes and behaviors.

Discussion

This research contributes to existing literature in three primary ways. First, this research integrates goal-setting theory (Locke 1968; Locke and Latham 1990; Locke and Latham 2002) into the area of diversity training in an experimental field setting. The results suggest that attitudes and reported behaviors depended on student and mentor goal conditions. Second, we examined the relative efficacy of self-set goal setting with regard to support for sexual orientation diversity, a topic that has received relatively little research in organizational research (Ragins and Cornwell 2001). Third, we used a longitudinal design, assessing attitudes and behaviors 3 and 8 months post-training, addressing limitations of past research that usually examine short-term reactions to training (Goldstein and Ford 2002). By using a longitudinal design, we found that behaviors influenced attitudes.

The results showed that there was a temporal effect of self-set goal setting on GLBT supportive behaviors and attitudes for both student and mentor goal conditions. In particular, 3 months post-training, students who developed supportive GLBT goals were more likely to report more supportive behaviors (H1a), but goal setting did not affect GLBT supportive attitudes (H1b). Mentor goal-setting condition did not influence GLBT supportive behaviors (H3a) or GLBT supportive attitudes (H3b). However, 8 months post-training, students who developed supportive GLBT goals were more likely to report more supportive behaviors (H2a) and attitudes (H2b) than students who did not set goals. Students with mentors who developed supportive GLBT goals were more likely to report more supportive behaviors (H4a) and attitudes (H4b) than students who did not set goals. Thus, both behaviors and attitudes were influenced by students’ goal setting at 8 months, but only students’ behaviors changed after 3 months.

These results have important implications for the implementation of diversity training in organizations. First, the pattern of results suggests that time was the key for participants to meet the goals that were set during the diversity training. That is, goals such as, “I will try not to use the word ‘gay’ in the derogatory way” or “I will not laugh at jokes about homosexuality” are not fulfilled immediately; rather, such goals need time. The importance of time for fulfilling the goals might be because of the research setting of our study, namely, a university campus. In such a context, students need time or the appropriate environment to meet goals that are related to GLBT issues. The goal-setting exercise during the diversity training is akin to behavioral outcome goals, which focus on behaviors rather than a hard outcome (e.g., number of widgets produced; Brown and Latham 2002). Goal setting in a diversity-training context does not lend itself to hard criterion measures, but rather on a series of behavioral acts (e.g., not laughing at gay jokes or learning about a famous GLBT individual) that occur over time.

Second, the results also showed that mentor goal setting influences attitudes and reported behaviors. The main effect of mentor goal setting did not affect students’ attitudes and behaviors 3 months post-training, but it did after 8 months. Because research shows that support is a key predictor of successful diversity training (Chrobot-Mason and Quiñones 2002; Rynes and Rosen 1994), this finding was consistent with past research in regard to supportive behaviors and attitudes toward gay men and lesbians. The main effect of mentor goal setting is particularly interesting, because the students were not aware of their mentor’s goal-setting condition. As such, there is a very low probability that demand characteristics could have played a role in the students’ report of their behaviors. This is particularly true for students who did not develop goals but their mentors did, because the students were not informed that their mentors also participated in the goal-setting manipulation.

We reasoned that the direct effect of mentor goal setting is because of social influence processes (Eby and Lockwood 2005; Fletcher and Ragins 2007; Kleinman et al. 2001, 2002). That is, mentors who set goals about their mentees are likely motivated to signal to mentees what are appropriate attitudes and behaviors. Having the “buy-in” from those with influence can lead to the GLBT supportive behaviors from mentors to be modeled or reinforced (Bell 2007; Rynes and Rosen 1995). That is, the students might have learned through observation and modeling. According to social learning theory (Bandura 1977), people learn through observing others’ behavior and attitudes and by observing the outcomes of those behaviors and attitudes. Our data cannot speak directly to these issues; we did not observe the interactions nor did mentors and students report the frequency and quality of their interactions, but it appears to be a plausible interpretation for the behavioral and attitudinal differences between the goal and no goal-setting conditions that were hypothesized and supported.

The results did not show support for the interaction between student and mentor goal-setting condition. These results were surprising considering that setting goals or having a mentor-set goals led to more supportive GLBT behaviors and attitudes. We expected that having mentors participate by setting goals would support and facilitate mentees’ goals because it may influence participants to take their own goals more seriously and follow through on them. Students who set goals during the diversity training had reached their goals of engaging in more supportive behaviors by the 3-month period; thus, it could be the case that the goal-setting students did not need to model behaviors and attitudes from their mentors.

Another implication for implementing diversity training in organizations is that our study demonstrates the importance of measuring both behaviors and attitudes in assessing diversity training. With respect to cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger and Carlsmith 1959), this study provides evidence that behaviors can influence attitudes, even if the reported behaviors and attitudes are months apart. In particular, behaviors were influenced by the diversity training at 3 months post-training, but not the attitudes. However, both behaviors and attitudes were influenced by the goal setting at 8 months. This finding is consistent with the idea that goals can motivate performance outcomes (i.e., behavioral acts) one wishes to attain (Brown and Latham 2002). In this study, goals were based on behavioral acts (e.g., not laughing at gay jokes) and not attitudes. Furthermore, analyses showed that students’ behaviors mediated the relationship between goal setting and the long-term attitudes (8-month time point) toward GLBT individuals. That is, goal-setting led to greater supportive behaviors, which resulted in more supportive attitudes 8 months post-training than when individuals did not set goals, suggesting that behaviors influence attitudes. This is consistent with recent research on cognitive dissonance (e.g., Norton et al. 2003) and with the typical dissonance paradigm in which participants engage in behavior inconsistent with their attitudes, which influences their attitudes in the direction of that behavior to reduce dissonance (e.g., Festinger and Carlsmith 1959).

Implications for Practice

This study has pragmatic implications for diversity training in organizations—a self-set goal-setting approach to diversity training can lead to improved behaviors toward gay men and lesbians. This study also suggests that mentor participation is a key in influencing attitudes and reported behaviors (Goldstein and Ford 2002; Chrobot-Mason and Quiñones 2002; Rynes and Rosen 1994). Based on relational cultural theory, we reasoned and found a direct effect of mentor goal setting, suggesting that mentors do influence mentees (Eby and Lockwood 2005; Fletcher and Ragins 2007; Kleinman et al. 2001, 2002). By setting goals about their mentees, mentors are likely signaling to their mentees appropriate attitudes and behaviors.

This simple, intuitive, and low-cost strategy would likely appeal to trainees, trainers, and the organizations in which they work. Furthermore, these initial findings point to goal setting as a strategy through which other diversity management strategies, such as performance appraisal systems that include diversity metrics or employee resource groups, might be enhanced. Brown and Latham (2002) have argued that goals can motivate performance outcomes by developing goals that are behaviorally oriented. This is consistent with the findings from Kalev et al. (2006), which showed that diversity management programs lead to more diversity in management when efforts to establish responsibility are in place. This suggests that goals that are set around establishing responsibility for diversity management might lead to effective outcomes.

Limitations and Future Directions

This research has several limitations that raise questions that can be addressed by future research. First, the diversity training was mandatory and all incoming students had to participate. Therefore, it is difficult to discern if attitudes and behaviors were completely influenced by the diversity training or if being in a college environment also affected attitudes and behaviors. Research shows that college students’ attitudes tend to become more open, egalitarian, tolerant, and liberal during their college years (Jacobs 1986; Lottes and Kuriloff 1994; Wilder et al. 1986). In a study of an Ivy League institution, senior students’ attitudes toward homosexuality were more positive than their attitudes as first-year students (measured a week before classes started; Lottes and Kuriloff 1994). We do not know to what extent attitudes and reported behaviors were influenced by the diversity training, because the diversity training was not manipulated. Related to this potential limitation is that we did not have pre-training measures of the attitudes and behaviors. Therefore, we were unable to look at changes in attitudes and behaviors pre- and post-training. However, the differences between the goal-setting and non goal-setting groups were because of our manipulation.

It is also important to note that the training session included discussions of multiple stigmatized identities. Future research might examine how attitudes and behaviors toward gay and lesbian individuals are influenced when the diversity-training content includes other minorities (e.g., race and religion) as it did with this research. This is particularly an important avenue for future research considering that the content in diversity training can vary. It can include a variety of demographic dimensions (e.g., race, age, gender, ethnicity, disability, and sexual orientation) as well as individual dimensions (e.g., parental status, learning styles, education level, and personality) and narrow dimensions that may only consider a few demographic dimensions (e.g., race, age; Roberson et al. 2003).

Second, our goal-setting manipulation focused solely on sexual orientation diversity, potentially limiting the generalizability of these findings to other stigmatized groups, such as those based on race, gender, or physical disability. Not all stigmas are the same. For example, the stigma of homosexuality includes the controllability, concealability, and contagion dimensions of stigma (Crocker et al. 1998; Goffman 1963; Herek 2004). Our focus on sexual orientation, however, was because of the dearth in organizational research examining sexual orientation and diversity training (Ragins 2004; Ragins and Cornwell 2001; Ragins et al. 2007). As such, the question arises as to how the results would change if the target of the diversity training. Future research might examine if goal setting in diversity training can be applied to other stigmatized groups. It would also be interesting to examine the types of goals that individuals would develop to be more accepting of individuals from other stigmatized groups.

Third, the student sample may not be generalizable to organizational settings. That is, students’ attitudes and behaviors can be influenced by living on a campus with diverse others and not necessarily because of diversity training. Future research might examine goal setting in diversity training with an adult sample in organizations. In such settings, for example, mentor participation might be more important than mentors’ participation in a college sample. Although the student–mentor relationships were formalized by assigning students to upper-class mentors and interactions are encouraged, the quality and frequency of the interactions between mentors and students is not monitored. Mentoring programs in organizations can be more formal than those in college and important for employees’ job satisfaction, career mobility, and recognition (Chao et al. 1992; Eby 1997; Fagenson 1989). As such, mentors’ goal-setting condition might produce stronger effects of goal setting in organizational settings.

Fourth, our sample size and response rate across time was small. This is a potential limitation because we do not have results from all the participants of the diversity training. It could be the case that students who participated in the 3-month and 8-month time points were students who were influenced the most by the diversity training or who took their goals more seriously than nonparticipants, which could potentially inflate our results. In addition, because there was a small overlap between the respondents at the 3 and 8 months time points, we cannot rule out the possibility that the differences in the results between these times could be because of differences in the samples. The small sample size for the 3-month post-training also could have led to the null effects of attitudes toward sexual orientation diversity. The results, however, were generally consistent with the literature and hypotheses and there were no differences on demographic variables between students who did participate and students who did not participate at the 3- and 8-month periods.

Finally, the measure of the sexual orientation diversity supportive behaviors was a self-report one and not based on actual behaviors. As such, demand characteristics might have influenced this measure. However, we did take steps to reduce the influence of demand characteristics. First, we informed the participants that their responses would be kept confidential. Second, the participants did not interact with the researchers when completing the measures, limiting the pressures to “please” or be a “good participant” when interacting with a researcher. Third and last, low scores on this measure (i.e., a “1” on an item) did not indicate discriminatory behavior toward gay and lesbian individuals. That is, if someone had not visited a gay or lesbian establishment, this does not indicate discrimination. Therefore, we believe that participants did not feel the pressure to inflate their responses to avoid being perceived as discriminatory or prejudiced against gay and lesbian individuals.

Conclusions

Despite its limitations, our study makes broad contributions to the diversity-training literature and has important implications for organizations. In accordance with our review of the research on diversity training, we (1) defined effective diversity training as improvement in behaviors and attitudes; (2) focused on a specific understudied group—gay men and lesbians—as the topic of the diversity training; and (3) examined both the short- and long-term outcomes associated with diversity training. This study shows the importance of using longitudinal methods for implementing and assessing diversity training, as it revealed that the effect of diversity training and goal-setting on supportive behaviors and attitudes toward gay men and lesbians was different across the two time points. Furthermore, this study demonstrates the importance of measuring both behaviors and attitudes and suggests that behaviors can influence attitudes. Thus, researchers and practitioners should strive to integrate theory into diversity-training programs, focus on behavioral and attitudinal metrics over time, and ensure management support.

References

Baldwin, T. T., & Ford, J. K. (1988). Transfer of training: A review and directions for future research. Personnel Psychology, 41, 63–105.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bell, M. P. (2007). Diversity in organizations. Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western.

Bell, M. P., & Kravitz, D. A. (2008). What do we know and need to learn about diversity education and training? Academy of Management Learning and Education, 7, 301–308.

Bernier, A., Larose, S., & Soucy, N. (2005). Academic mentoring in college: The interactive role of student’s and mentor’s interpersonal dispositionsannie. Research in Higher Education, 46, 29–51.

Brown, T. C., & Latham, G. P. (2002). The effects of behavioural outcome goals, learning goals, and urging people to do their best on an individual’s teamwork behaviour in a group problem-solving task. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 34, 276–285.

Burke, L. A., & Hutchins, H. M. (2007). Training transfer: An integrative literature review. Human Resource Development Review, 6, 263–296.

Chao, G. T., Walz, P. M., & Gardner, P. D. (1992). Formal and informal mentorships: A comparison on mentoring functions and contracts with nonmentored counterparts. Personnel Psychology, 45, 619–636.

Cheng, E., & Ho, D. (2001). A review of transfer training studies in the past decade. Personnel Review, 30, 102–118.

Chrobot-Mason, D., & Quiñones, M. A. (2002). Training for a diverse workplace. In K. Kraiger (Ed.), Creating, implementing and managing effective training and development (pp. 117–159). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Clark, M. M. (2003). Three non-employment law cases in high court have business ramifications. HR Magazine, 48, 31–47.

Crocker, J., Major, B., & Steele, C. (1998). Social stigma. In D. T. Gilbert & S. T. Fiske (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 504–553). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Dutton, J. E., & Ashford, S. J. (1993). Selling issues to top management. Academy of Management Review, 18, 397–428.

Eby, L. T. (1997). Alternative forms of mentoring in changing organizational environments: A conceptual extension of the mentoring literature. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 51, 125–144.

Eby, L. T., & Lockwood, A. (2005). Proteges and mentors’ reactions to participating in formal mentoring programs: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67, 441–458.

Fagenson, E. A. (1989). The mentor advantage: Perceived career-job experiences of protégés versus non-proteges. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 10, 309–320.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Festinger, L., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1959). Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58, 203–210.

Fletcher, J. K., & Ragins, B. R. (2007). Stone centre relational cultural theory: A window on relational mentoring. In B. R. Ragins & K. E. Kram (Eds.), The handbook of mentoring at work: Research, theory and practice (pp. 373–399). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Ford, J. K., & Weissbein, D. A. (1997). Transfer of training: an updated review and analysis’. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 10, 22–41.

Friskopp, A., & Silverstein, S. (1996). Straight jobs, gay lives: Gay and lesbian professionals, the Harvard Business School, and the American workplace. New York: Touchstone/Simon & Schuster.

Galvin, T. (2003, October). The twenty-second annual industry report. Training, 19–45.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Prentice Hall.

Goldstein, I., & Ford, J. K. (2002). Training in organizations (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Gonsiorek, J. C., & Weinrich, J. D. (1991). Homosexuality: Research implications for public policy. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

Gurin, P., Nagda, B. A., & Lopez, G. E. (2004). The benefits of diversity in education for democratic citizenship. Journal of Social Issues, 60, 17–34.

Haddock, G., Zanna, M. P., & Esses, V. M. (1993). Assessing the structure of prejudicial attitudes: The case of attitudes toward homosexuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 1105–1118.

Hebl, M. R., Foster, J. B., Mannix, L. M., & Dovidio, J. F. (2002). Formal and interpersonal discrimination: A field study of bias toward homosexual applicants. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 815–825.

Herek, G. M. (1994). Assessing heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and ay men: A review of the empirical research with the ATLG scale. In B. Greene & G. M. Herek (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives in lesbian and gay issues in psychology (pp. 206–228). Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

Herek, G. M. (2000). The psychology of sexual prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9, 19–22.

Herek, G. M. (2004). Beyond “homophobia”: Thinking about sexual prejudice and stigma in the twenty-first century. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 1, 6–24.

Holladay, C. L., & Quinones, M. A. (2008). The influence of training focus and trainer characteristics on diversity training effectiveness. Academy of Management: Learning & Education, 7, 343–354.

Horn, S. S., Szalacha, L. A., & Drill, K. (2008). Schooling, sexuality, and rights: An investigation of heterosexual students’ social cognition regarding sexual orientation and the rights of gay and lesbian peers in school. Journal of Social Issues, 64, 791–813.

Hurtado, S. (2005). The next generation of diversity and intergroup relations research. Journal of Social Issues, 61, 595–610.

Jacobi, M. (1991). Mentoring and undergraduate academic success: A literature review. Review of Educational Research, 61, 505–532.

Jacobs, J. A. (1986). The sex-segregation of fields of study. Journal of Higher Education, 57, 134–154.

Kalev, A., Dobbin, F., & Kelly, E. (2006). Best practices or best guesses? Assessing the efficacy of corporate affirmative action and diversity policies. American Sociological Review, 71, 589–617.

Kleinman, G., Siegel, P. H., & Eckstein, C. (2001). Mentoring and learning: The case of CPA firms. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 22, 22–33.

Kleinman, G., Siegel, P. H., & Eckstein, C. (2002). Teams as a learning forum for accounting professionals. Journal of Management Development, 21, 427–460.

Latham, G. P. (1997). Overcoming mental models that limit research on transfer of training in organizational settings. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 46, 371–375.

Lazin, M. (2007). Record 94% of Fortune 500 companies provide sexual orientation discrimination protection. Retrieved June 1, 2011, from http://Equalityforum.com.

Locke, E. A. (1968). Toward a theory of task motivation and incentives. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 3, 157–189.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting and task performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57, 705–717.

Lottes, I. L., & Kuriloff, P. J. (1994). The impact of college experience on political and social attitudes. Sex Roles, 31, 31–54.

Morrison, M. A., Morrison, T. G., & Franklin, R. (2009). Modern and old-fashioned homonegativity among samples of Canadian and American university students. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40, 523–542.

Noe, R. A. (1988). An investigation of the determinants of successful assigned mentoring relationships. Personnel Psychology, 41, 457–480.

Noe, R. A. (1999). Employee training and development. Boston: Irwin McGraw-Hill.

Norton, M. I., Monin, B., Cooper, J., & Hogg, M. A. (2003). Vicarious dissonance: Attitude change from the inconsistency of others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 47–62.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891.

Quiñones, M. A., & Ehrenstein, A. (1997). Psychological perspectives on training in organizations. In M. A. Quiñones & A. Ehrenstein (Eds.), Training for a rapidly changing workplace: Applications of psychological research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Ragins, B. R. (2004). Sexual orientation in the workplace: The unique work and career experiences of gay, lesbian and bisexual workers. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 23, 25–120.

Ragins, B. R., & Cornwell, J. M. (2001). Pink triangles: Antecedents and consequences of perceived workplace discrimination against gay and lesbian employees. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 1244–1261.

Ragins, B. R., Singh, P., & Cornwell, J. M. (2007). Making the invisible visible: Fear and disclosure of sexual orientation at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 1103–1118.

Reber, R. A., & Wallin, J. A. (1984). The Effects of Training, Goal Setting, and Knowledge of Results on Safe Behavior: A Component Analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 27, 544–560.

Roberson, L., Kulik, C. T., & Pepper, M. B. (2001). Designing effective diversity training: Influence of group composition and trainee experience. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(8), 871–885.

Roberson, L., Kulik, C. T., & Pepper, M. B. (2003). Using needs assessment to resolve controversies in diversity training design. Group & Organization Management, 28, 148–174.

Roberson, L., Kulik, C. T., & Pepper, M. B. (2009). Individual & environmental factors influencing the use of transfer strategies after diversity training. Group & Organization Management, 34, 67–89.

Rynes, S., & Rosen, B. (1994). What makes diversity programs work? HR Magazine, 39, 67–73.

Rynes, S., & Rosen, B. (1995). A field survey of factors affecting the adoption and perceived success of diversity training. Personnel Psychology, 48, 247–270.

Salas, E., & Cannon-Bowers, J. A. (2001). The science of training: A decade of progress. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 471–499.

Segal, J. A. (2003). Diversity: Direct or disguised? HR Magazine, 48, 10–20.

Smith-Jentsch, K. A., Salas, E., & Brannick, M. T. (2001). To transfer or not to transfer? Investigating the combined effects of trainee characteristics, team leader support, and team climate. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 279–292.

Weaver, V. J., & Dixon-Kheir, C. (2002). Making the business case for diversity. SHRM.

Wexley, K. N., & Baldwin, T. T. (1986). Post-training strategies for facilitating positive transfer: An empirical exploration. Academy of Management Journal, 29, 503–520.

Wexley, K. N., & Nemeroff, W. (1975). Effectiveness of positive reinforcement and goal setting as methods of management development. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, 239–246.

Whitley, B. E., Childs, C. E., & Collins, J. B. (2011). Differences in black and white American college attitudes toward lesbian and gay men. Sex Roles, 64, 299–310.

Wilder, D. H., Hoyt, A. E., Surbeck, B. S., Wilder, J. C., & Carney, P. A. (1986). Greek affiliation and attitude change in college students. Journal of College Student Personnel, 27, 510–519.

Wood, R. A., & Locke, E. A. (1990). Goal setting and strategy effects on complex tasks. Research in Organizational Behavior, 12, 73–109.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Madera, J.M., King, E.B. & Hebl, M.R. Enhancing the Effects of Sexual Orientation Diversity Training: The Effects of Setting Goals and Training Mentors on Attitudes and Behaviors. J Bus Psychol 28, 79–91 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-012-9264-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-012-9264-7