Abstract

Purpose

In order for diversity management programs to serve as competitive resources, organizations must attract employees who will fit in and support an organization’s diversity management programs. Two experiments examined situational perspective taking, in which one imagines being the target of workplace discrimination, as an intervention to increase positive attitudes toward organizations that invest in diversity management programs. Participant gender and ethnic identity were examined as moderators.

Design/Methodology/Approach

In two experiments, managers (study 1) and active job seekers (study 2) were instructed to imagine and write down how they would feel if they were the targets of workplace discrimination and read recruitment materials of an organization and its investment in diversity management programs.

Findings

Both studies showed that engaging in a situational perspective taking about being the target of workplace discrimination led to more P-O fit and organizational attraction toward an organization that has diversity management programs. The effect of situational perspective taking had a greater impact on White men than on women and ethnic minority participants.

Implications

These results suggest that the design of organizational recruitment activities should highlight their support of diversity management programs and emphasize that all member benefit from diversity management programs. Originality/value—despite theoretical work that suggests that organizational attitudes are an important factor for the effectiveness of diversity management programs, this is the first known research that shows that perspective taking can help people see the value in diversity management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The workforce is characterized by individuals from diverse social identity groups, including ethnic minorities, women, sexual minorities, religious minorities, people with disabilities, immigrant employees, and intergenerational workers, making diversity a reality for the American workforce (Bond & Haynes, 2014; U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). As a result of such diversity in the workforce, corporate investments in diversity management programs that promote fair treatment and a more positive environment for a diverse staff have increased over the last two decades (Chavez & Weisinger, 2008). Diversity management programs are formal organizational practices that capitalize on the opportunities that diversity offers through policies that promote fairness in hiring, developing, and advancing employees from diverse backgrounds (Society for Human Resource Management, 2008; Yang & Konrad, 2011). Diversity management programs are not only perceived as socially responsible but also as a strategic business objective with the capability to make the organization more competitive by reducing discrimination (Avery, 2011; Kalev, Dobbin, & Kelly, 2006; Triana & Garcia, 2009; Triana, Garcia, & Colella, 2010).

However, in order for diversity management programs to serve as competitive resources, employees must support diversity management programs (Avery, 2011; Yang & Konrad, 2011). For example, a growing body of literature has examined the effect of specific programs (e.g., diversity training) or organizational support for diversity management programs on applicant and employee attitudes and has shown that not all have positive attitudes toward diversity management programs (e.g., Furunes & Mykletun, 2007; Gilbert & Ivancevich, 2000; Herrera, Duncan, Green, Ree, & Skaggs, 2011; Holladay, Knight, Paige, & Quiñones, 2003; Kidder, Lankau, Chrobot-Mason, Mollica, & Friedman, 2004; Kossek & Zonia, 1993; Martins & Parsons, 2007; Ng & Burke, 2004; Sawyerr, Strauss, & Yan, 2005; Strauss, Connerley, & Ammermann, 2003; Williams & Bauer, 1994). In particular, women and ethnic minorities tend to have more positive attitudes toward diversity management programs than White men.

Research also shows that individual differences, such as the salience of gender and ethnic identity, personality types, and cultural values can influence attitudes toward diversity management programs, such that women and ethnic minorities do not always hold positive attitudes toward diversity management programs (e.g., Martins & Parsons, 2007; Ng & Burke, 2004; Sawyerr et al., 2005; Strauss et al., 2003). If organizational members do not embrace diversity management programs, their negative attitudes can disrupt the efficacy of diversity management programs. Thus, there is a need to examine interventions than can be used to positively influence attitudes toward organizations that invest in diversity management programs.

A promising intervention that can potentially lead to positive attitudes toward organizations that have diversity management programs is perspective taking, which is the cognitive capacity to consider the situations from the viewpoints, feelings, and reactions of others (Dovidio et al., 2004; Galinsky & Ku, 2004; Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000). Perspective taking involves having a person think about how one would feel in another person’s situation, which has been shown to reduce prejudice and bias against members of stigmatized groups and increases liking of, empathy toward, and support of stigmatized individuals (e.g., Batson, Chang, Orr, & Rowland, 2002; Galisnky, Ku, & Wang, 2005; Todd, Bodenhausen, Richeson, & Galinsky, 2011).

One unexplored area of research of perspective taking is whether perspective taking of a situation (e.g., experiencing discrimination) can lead to positive attitudes toward structures (e.g., organizational investment diversity management programs) that would remediate the imagined situation. That is, not only can individuals take the perspective of out-group members but they can also take the perspective of experiencing a particular situation, which is hereafter referred to as situational perspective taking. Therefore, the purpose of the current paper was to examine how situational perspective taking can positively influence attitudes toward an organization that invests in diversity management programs.

In particular, the current study examined situational perspective taking in the applicant recruitment context by using experimental methods to examine if perspective taking positively affects organizational attraction and person-organization fit (P-O fit) toward an organization that invests in diversity management programs. Examining the proposed intervention––situational perspective taking––in the applicant recruitment context is important for several practical and theoretical reasons. Seeing diversity as a competitive advantage, many organizations have information about their diversity management programs in recruitment materials and on their corporate websites for prospective applicants (Madera, 2013; Point & Singh, 2003; Uysal, 2013; Singh & Point, 2004; Singh & Point, 2006). In fact, many corporations have diversity management information under their “about us” or “careers” sections (Diversityinc.com, 2016; Madera, 2013). Not all applicants will see the benefits and value of diversity management programs, which could influence their decision to apply and potentially affect the applicant pool quality. The more qualified individuals are attracted to organizations, the greater utility for an organization’s selection system (Dineen & Soltis, 2010). Organizations must attract employees who will fit in and support an organization’s diversity management programs (Avery, 2011; Yang & Konrad, 2011).

The current paper proposes that taking the perspective of being the target of discrimination may lead to more positive attitudes toward organizations that invest in diversity management programs. Just as social perspective taking leads to positive attitudes and feelings toward others, situational perspective taking of discrimination can lead to positive attitudes toward organizational investment in diversity management programs. In other words, imagining one is the target of discrimination that can lead to the sense that organizational programs that reduce discrimination are of value and importance, making organizations that support diversity management programs attractive.

Background and Hypotheses

Perspective Taking

Individuals tend to categorize themselves and others into groups using personally meaningful dimensions, such as ethnicity, sex, nationality, or culture (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). Specifically, individuals categorize themselves and similar others in the “in-group” and categorize individuals who are dissimilar as the “out-group.” Social perspective taking has been shown to reduce the thinking in terms of in-groups and out-groups or “me” versus “others” and increase the mental representations of the self and others to share common elements (Cialdini, Brown, Lewis, Luce, & Neuberg, 1997; Davis, Conklin, Smith, & Luce, 1996; Dovidio et al., 2004; Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000). Social perspective taking requires a person to think and feel what it would be like to be a member of an out-group, which leads to a mental representation of the self and others creating a sense of similarity and shared identity with others, thereby producing positive attitudes and feelings toward others.

The standard paradigm of social perspective taking involves having people imagine a day in the life of an individual from an out-group. After this manipulation, individuals show more positive attitudes toward the out-group than individuals who do not take the perspective of other targets (for a review, see Todd & Galinsky, 2014). Thus, social perspective taking leads to positive attitudes and less prejudice toward out-group members. Situational perspective taking has similar mechanisms to social perspective taking, but differs from social perspective taking in that social perspective taking involves imagining being in the shoes of a specific target who they read about or viewed in a picture (e.g., African-American, a person with HIV/AIDS, an addict, or a homeless person (Batson, Early, & Salvarani, 1997a; Batson et al., 1997b; Batson et al., 2002; Dovidio et al., 2004; Galinsky & Ku, 2004) and situational perspective taking requires imagining experiencing a particular situation (Gehlbach, 2004).

Although most of the literature in social and organizational psychology has focused on social perspective taking (Todd & Galinsky, 2014), there is research in which participants are asked to imagine a situation rather than being in the shoes of an out-group member, such as being mistreated by a classmate (Takaku, 2001), experiencing a social phobia in front of others (Wells, Clark, & Ahmad, 1998), or suffering from a neurological disease (Lamm, Batson, & Decety, 2007) with similar outcomes as social perspective taking. One unexplored area of research is if situational perspective taking would then lead to positive attitudes toward structures (e.g., organizations that invest in diversity management programs) that would remediate the imagined situation (e.g., experiencing discrimination). Just as social perspective taking leads to positive attitudes and feelings toward members of out-groups, situational perspective taking of discrimination can lead to positive attitudes toward organizations that invest in diversity management programs for several reasons.

First, imagining being the target of discrimination invokes personal distress (Batson, Early, & Salvarani, 1997; Batson et al., 1997), which result in greater egocentrism (Vorauer & Sasaki, 2014; Vorauer & Sucharyna, 2013). This occurs because it is easier to imagine how one would feel and think than it is to imagine how another person would feel and think. Second, individuals have egocentric biases that lead to exaggerations on how they would experience an event (Blaine & Crocker, 1993). By invoking being the target of discrimination, individuals are likely to exaggerate the distress that they could experience. Third and last, maintaining a positive view of the self is vital for overall well-being, consequently, individuals will strive to protect a positive view of the self (Crocker & Wolfe, 2001). Therefore, activating the self through situational perspective taking can lead to positive evaluations of structures that would alleviate the negativity of a situation (e.g., experiencing discrimination), because egocentric biases are applied to said structures. Thus, situational perspective taking of discrimination can lead to positive attitudes toward diversity management programs.

Organizational Investment in Diversity Management Programs: Fit and Attraction

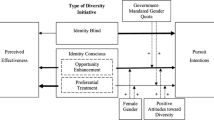

Figure 1 outlines the theoretical model illustrating the hypothesized relationships between the variables for the current series of studies: organizational attraction (i.e., the extent to which an individual views an organization as desirable and wants to work for it) and P-O fit (i.e., the extent to which one perceives organizational attributes, values, and principles are compatible with their own personal characteristics values; Swider, Zimmerman, & Barrick, 2014; Yu, 2014). As shown in Fig. 1, P-O fit is the proximal outcome of situational perspective taking, mediating the relationship between situational perspective taking and organizational attraction toward organizations that invest in diversity management programs. Avery’s (2011) model suggests that there are two general factors that are theorized to predict diversity endorsement. The first factor is based on self-interest, because “individuals tend to be motivated to maximize their personal outcomes, which could put them in favor of diversity, depending on the nature of their identity” (p. 242). The second factor includes ideological beliefs in intergroup equality.

These two factors provide reasons to why situational perspective taking of discrimination would impact the extent to which one feels that one’s values and attitudes are similar with those of an organization that invests in diversity management programs. The first reason focuses on self-interests. When one imagines being the target of discrimination (1) the self is evoked, (2) there is a need to reduce the distress of discrimination, (3) diversity management programs remediate discrimination and endorse intergroup equality (Avery, 2011; Kalev et al., 2006; Thomas, 2008; Triana et al., 2010; Richard, 2000), thereby (4) making organizations that support diversity management programs compatible to the self. In other words, situational perspective taking of discrimination increases P-O fit toward organizations that invest in diversity management programs, because diversity management programs reduce the distress of discrimination that one imagines could occur to him or her. If one imagines that they can be the target of discrimination then they are likely to see more fit with an organization that has structures to reduce discrimination (i.e., diversity management programs) than an individual who does not imagine they can be the target of discrimination.

A second reason for why situational perspective taking of discrimination would impact the extent to which one feels that one’s values and attitudes are similar with those of an organization that invests in diversity management programs focuses on beliefs in intergroup equality. Research shows that organizational members (employees and applicants) are concerned about how they will be treated at work, because organizational members want to work for organizations that care about their fair treatment and development (Greening & Turban, 2000; Turban & Greening, 1997). In other words, organizational members often have implicit expectations that their current or future workplace is fair. If organizations invest resources in diversity management programs, then organizational members and potential applicants might perceive this as a signal that their organization endorses egalitarian values that are compatible with the implicit expectations that the organization will treat them fairly. Imagining being the target of discrimination through situational perspective taking can lead to greater perceived fit with an organization with diversity management, because the goal of diversity management (i.e., to increase fairness and equality) is made more compatible with one’s implicit expectation of intergroup equality and fairness.

Thus, the two factors articulated in Avery’s (2011) model of diversity endorsement are relevant to the theoretical rationale in the current study: situational perspective taking of discrimination, in which one imagines being the target of discrimination, can make both factors—self-interests and implicit expectations of a fair workplace—salient. The relationship between P-O fit and organizational attraction has been well established (e.g., Carless, 2005; Chapman, Uggerslev, Carroll, Piasentin, & Jones, 2005; Phillips, Gully, McCarthy, Castellano, & Kim, 2014; Uggerslev, Fassina, & Kraichy, 2012; Yu, 2014) and therefore not reviewed in the current paper. However, less is known about how situational perspective taking can positively influence applicants’ P-O fit and attraction toward organizations that invest in diversity management programs. Based on the theoretical explanations of the outcomes of perspective taking and Avery’s (2011) model, it was hypothesized that situational perspective taking of discrimination would lead to greater attraction toward organizations that support diversity management programs through P-O fit. In sum,

Hypothesis 1:

Situational perspective taking of discrimination will lead to higher P-O fit toward an organization that supports diversity management programs than not engaging in perspective taking.

Hypothesis 2:

P-O fit will mediate the effect of situational perspective taking of discrimination on organizational attraction.

Race

As shown in Fig. 1, race is proposed as a moderator of the relationship between situational perspective taking of discrimination and P-O fit. Research on employee attitudes toward diversity management programs has shown that all else being equal, racial minority members (Asians, Blacks, and Latinos) tend to have more positive attitudes toward diversity management programs than their White counterparts (e.g., Furunes & Mykletun, 2007; Gilbert & Ivancevich, 2000; Herrera et al., 2011; Harrison, Kravitz, Mayer, Leslie, & Lev-Arey, 2006; Holladay et al., 2003; Kidder et al., 2004; Konrad & Spitz, 2003; Kossek & Zonia, 1993; Ng & Burke, 2004; Strauss et al., 2003; Williams & Bauer, 1994). In addition, Avery’s (2011) theoretical model of diversity support also proposed that racial minorities would be more supportive of diversity than majority members.

Therefore, given that racial minorities are more likely to have positive attitudes toward an organization that supports diversity management programs, the effect of situational perspective taking on P-O fit might be stronger for White individuals than for racial minority individuals. In fact, when asked what racial groups associate the word diversity with, both racial minorities and White individuals associate the word “diversity” with minority groups, but not with the majority group members (Unzueta & Binning, 2010; Unzueta & Binning, 2012). As such, even without perspective taking, racial minorities are more likely to perceive more compatibility or fit with organizations that support diversity management programs than White individuals (Avery & McKay, 2006; Avery, Hernandez, & Hebl, 2004).

Research on affirmative action programs shows that White individuals do not necessarily have negative attitudes toward diversity nor believe that race-based affirmative action programs lead to a perceived disadvantage to Whites; instead, their attitudes can depend on their level of modern racism and collective relative deprivation (Shteynberg, Leslie, Knight, & Mayer, 2011). This research suggests that their implicit expectations of a fair workplace and equality predict support for race-based affirmative action. Research on attitudes toward affirmative action also shows that measures of self-interest are strong predictors of attitudes toward affirmative action, such that self-interest has a positive correlation with support for affirmative action, regardless of race and gender (Harrison et al., 2006). While this aforementioned research was on affirmative action, it lends support for the idea that White individuals would have positive attitudes toward an organization’s investment in diversity management programs. Because situational perspective taking of discrimination makes self-interests and implicit expectations of a fair workplace salient, White individuals will perceive more fit toward an organization that has diversity management programs when they engage in situational perspective taking of discrimination than those who do not. The difference in P-O fit between those who do versus do not engage in situational perspective taking will be greater for Whites than for racial minorities given that racial minorities are more likely to already have positive attitudes toward diversity management than White individuals. Thus, it was hypothesized that the effect of perspective taking on P-O fit would be stronger for White individuals than for racial minority individuals, which is positively related to organizational attraction.

Hypothesis 3:

Race will moderate the relationship between situational perspective taking of discrimination and organizational attraction via P-O fit, such that the effect of situational perspective taking on P-O fit will be stronger for White individuals than for minority individuals..

Gender

In addition, gender is also proposed as a moderator of the relationship between situational perspective taking of discrimination and P-O fit. Avery (2011) proposed that women would be more supportive of organizations with diversity management programs than men. Although numerically women represent about half of the workforce, women are still a minority in regard to hierarchical representation within organizations, having less status and access to power than men (Koenig, Eagly, Mitchell, & Ristikari, 2011; Weyer, 2007). Research shows that women tend to have more positive attitudes toward diversity management programs and organizations that implement them than men (e.g., Chen & Hooijberg, 2000; Cundiff, Nadler, & Swan, 2009; Ng & Burke, 2004; Sawyerr et al., 2005). As such, men are more likely to gain positive attitudes toward organizations that support diversity management programs through situational perspective taking than women, because women tend to already have positive attitudes toward diversity initiatives. Thus, it was hypothesized that the effect of situational perspective taking on P-O fit would be stronger for men than for women, and subsequently leads to more organizational attraction.

Hypothesis 4:

Gender will moderate the relationship between situational perspective taking of discrimination and organizational attraction via P-O fit, such that the effect of situational perspective taking on P-O fit will be stronger for men than for women.

Interaction of Race and Gender

Building on Berdahl and Moore’s (2006) paper on double jeopardy, the current studies examined the intersectionality of race and gender. Not only do race and gender have main effects on attitudes toward diversity management, it is possible that race and gender interact such that White men have the most to gain from situational perspective taking than White women, minority men, and minority women. In a study of sex and racial harassment, Berdahl and Moore (2006) found an additive effect of race and gender such that minority women experience the most harassment compared to minority men, White men, and White women. Likewise, the current study examined if White men are more likely to gain positive attitudes toward organizations that support diversity management programs through perspective taking than majority women, minority men, and minority women. In their model of coping strategies of White privilege, Knowles, Lowery, Chow, and Unzueta (2014) argued that interventions aimed at reducing inequality should focus on the strategy of dismantling, which is when privilege members embrace policies and behaviors aimed at reducing in-group privilege. Imagining one can be the target of discrimination gives White men the opportunity to imagine what it is like to not have privilege. In contrast, women and minorities are more likely to already embrace diversity making situational perspective taking less impactful than for White men, because both women and minorities have some experience with being disadvantaged.

For example, in a study of attitudes toward affirmative action, Konrad and Spitz (2003) found that White men had less support for affirmative action than did White women and minority women, but not significantly different than minority men. In another study of attitudes toward affirmative action (Parker, Baltes, & Christiansen, 1997), White women and minority men and women perceived organizational support for affirmative action to be positively linked to organizational justice and increased career development opportunities, but not White men. Thus, it was hypothesized that the effect of situational perspective taking on P-O fit will be stronger for White men than for White women, minority women, and minority men.

Hypothesis 5:

There will be a three-way interaction between ethnicity, gender, and situational perspective taking of discrimination on organizational attraction via P-O fit, such that the effect of situational perspective taking on P-O fit will be stronger for White men than for all other demographic members.

Study 1

Method

Participants

The participants were 138 managers (51% men, 49% women) working in the hotel industry who were attending a regional hotel association training and development conference. All of the managers were from distinct hotels and worked as operation managers. The average age of the participant was 28.84 (SD = 7.64) and had an average tenure of 7.03 (SD = 4.94) years working in the hotel industry, 4.80 (SD = 3.31) years working as a manager, and 2.78 (SD = 1.88) years working at their current company. In regard to race, 50.7% of the participants identified as Caucasian/White, 28.1% identified as Latino(a)/Hispanic, 13.6% as African-American/Black, 3.1% as Asian, and 4.5% reported as “other.”

Design and Procedure

The current study used a 2(Perspective taking: yes or no) × 2(Race: White or minority) × 2(Gender: male or female) between-subjects experimental design. A survey was distributed to the managers in between various sessions during a break. They were informed that they were going to read recruitment material of a hotel and make an evaluation of the hotel assuming the role of an applicant. After consenting to participate on a study of hotel evaluations, the first independent variable (Perspective taking: yes or no) was manipulated by having half of the participants engage in a situational perspective taking. Based on research on perspective taking manipulation (Todd & Galinsky, 2014; Vorauer & Sasaki, 2014; Vorauer & Sucharyna, 2013), the participants were asked to imagine and write down how they would feel if they were the targets of workplace discrimination. Specifically, the managers read:

“Antidiscrimination laws protect all individuals from workplace discrimination, regardless of one's background. Unfortunately, workplace discrimination still occurs. Now imagine that you are the target of discrimination at work and imagine how you would feel.”

Participants in the control condition did not receive this manipulation and instead proceeded to the next page after the consent form, which was presented as recruitment material of a hotel that is depicted in their corporate website. The recruitment material included a description of the hotel, which included information that is normally provided in recruitment materials and on websites, such as the type of hotel segment (full-service), location segment, average published rate, descriptions of the services offered, the various food and beverage operations, and the service quality of the hotel. This recruitment material closely simulated actual recruitment materials that are often used at hospitality career fairs. The information of recruitment material also served as a filler between the manipulation and the dependent measures. Following similar procedures used in prior research examining reactions to organizational information (e.g., Elkins & Phillips, 2000; Kaiser et al., 2013; Madera, 2012; Ng & Burke, 2005), the participants then read a description of the “Careers Section” that is available for prospective applicants. This section served to also include information about the organizational investment in diversity management programs:

“The following statement is from the official hotel website under their ‘Careers Section’:

Hotel Surca is proud of its commitment to being an employer of choice in the hospitality industry for people of all backgrounds. We implement diversity management programs that offer opportunities for career progression in a working environment that supports human rights and a workplace free of discrimination and harassment”.

After reading about the hotel, the participants were asked to complete the dependent measures, demographic questions, and a manipulation check.

Measures

Person-Organization Fit

P-O fit was measured using the three-item instrument developed by Cable and Judge (1996) using a 7-point Likert-type scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Example items include the following: “I feel my values fit Hotel Surca’s values” and “My values match those of Hotel Surca.” The reliability for this measure was 0.94.

Organizational Attraction

To measure organizational attraction, the five-item measure developed by Highhouse, Levens, and Sinar (2003) was used. The participants used a 7-point Likert-type scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Example items include the following: “Hotel Surca is attractive to me as a place for employment,” “I am interested in learning more about Hotel Surca,” and “For me, Hotel Surca would be a great place to work.” The reliability for this measure was 0.96.

Race

Following past research (e.g., Berdahl & Moore, 2006; Harrison et al., 2006; Konrad & Spitz, 2003; Leslie, Snyder, & Glomb, 2013; Unzueta & Binning, 2010; Unzueta & Binning, 2012), the non-Caucasian/White respondents were recoded as “ethnic/racial minority.” The final coding for race included 50.7% Caucasian/White and 49.3% ethnic minority respondents.

In addition to the theoretical rationale, there was also a practical rationale for aggregating ethnic minorities into a single category––simply––the sample size for each ethnic minority group varied greatly and were small for participants who identified as Asian (n = 4) and “other” (n = 6). A four-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with ethnicity representing the four ethnic minority groups (Latino(a)/Hispanic, African-American/Black, Asian, and “other”) as the independent variable and P-O fit and organizational attraction as the dependent variables did not reveal a significant main effect for ethnicity (Wilks’s Λ = 0.88, F(6, 126) = 1.34, p > 0.05). Follow-up analysis of variance (ANOVA) for P-O fit (F[3, 64] = 0.67, p > 0.05; Latino(a)/Hispanic [M = 6.02, SD = 0.71], African-American/Black [M = 6.09, SD = 0.63], Asian [M = 6.50, SD = 0.52], and “other” [M = 6.17, SD = 0.52]) and organizational attraction (F[3, 64] = 0.50, p > 0.05; Latino(a)/Hispanic [M = 6.13, SD = 0.70], African-American/Black [M = 6.33, SD = 0.55], Asian [M = 6.08, SD = 0.82], and “other” [M = 6.03, SD = 0.49]) confirmed that the means for the different ethnic minority groups were not significantly different from each other.

Gender

Gender was dummy coded as 1 = male and 2 = female.

Manipulation Check

Participants were asked if they imagined “being the target of workplace discrimination” with a “yes/no” response scale. The written responses from the managers in the perspective taking condition were also reviewed to check that they wrote about being the target of discrimination.

Results

Psychometric Analyses

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to demonstrate that the participants differentiated between P-O fit and organizational attraction. A CFA of a two-factor model representing P-O fit and organizational attraction demonstrated adequate fit: χ 2 = 18.79, df = 19, NFI = 0.97, IFI = 0.99, CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.018; all loadings were statistically significant and were higher than 0.50 (they varied from 0.72 to 0.89), indicating convergent validity (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988; Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2010). The average variance extracted (AVE) was 0.56 for the P-O fit and 0.65 for organizational attraction, both greater than the 0.50 cutoff (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988). The squared correlation between the measures (r 2 = 0.31) was lower than each AVE, demonstrating discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). This two-factor model was compared to a one-factor-model, which demonstrated poor fit and did not significantly improve the fit: χ 2 = 71.42, df = 20, NFI = 0.89, IFI = 0.92, CFI = 0.92; RMSEA = 0.137 (Δχ 2 = 52.63; Δdf = 1; p < 0.05).

Test of Hypotheses

In regard to the manipulation check, all of the managers in the perspective taking condition correctly identified that they did imagine that they were the target of workplace discrimination. In addition, all of the managers wrote about being the target of discrimination in the situational perspective taking condition. The means, standard deviations, and correlations of the variables are shown in Table 1. Hypothesis testing was conducted by examining nested (1) mediation, (2) moderated mediation with both moderators, and (3) moderated moderated mediation models with the Preacher, Rucker, and Hayes (2007) bootstrapping procedure with confidence intervals that provide evidence of significant indirect effects when they exclude zero (Shrout & Bolger, 2002) using PROCESS version 2.13 for SPSS (Hayes, 2013). The index of partial moderated mediation is used to provide a formal test for the two simultaneous moderated mediation effects and indicates if the moderated mediation for one moderator is significant when the other moderator is held constant (Hayes, 2015). Likewise, the index of moderated moderated mediation is used to provide a formal test for the three-way interaction mediation model (Hayes, 2015).

Hypothesis 1 predicted a direct effect of situational perspective taking on P-O fit and Hypothesis 2 predicted an indirect effect between situational perspective taking and organizational attraction through P-O fit. As shown in Table 2, both Hypotheses 1 and 2 were supported. Specifically, there was a significant direct effect of situational perspective taking on P-O fit (β = 0.56, p < 0.01), and a significant indirect effect between situational perspective taking and organizational attraction through P-O fit (effect = 0.44, CI.95 = 0.31, 0.57).

Both moderators were examined simultaneously. Hypothesis 3 predicted that race would moderate the relationship between situational perspective taking of discrimination and organizational attraction via P-O fit, such that the effect of situational perspective taking on P-O fit will be stronger for White individuals than for minority individuals. Hypothesis 4 predicted that gender would moderate the relationship between situational perspective taking of discrimination and organizational attraction via P-O fit, such that the effect of situational perspective taking on P-O fit will be stronger for men than for women. As shown in Table 2, support was found for both moderated mediation models. Specifically, the index of partial moderated mediation was significant for race (index = −0.16, CI.95 = −0.31, −0.03), indicating that the conditional indirect effect the White managers (index = .41, CI.95 = 0.26, 0.60) was statistically different and stronger than for the ethnic minority managers (index = .25, CI.95 = 0.23, 0.41), even after controlling for the effect of gender, supporting Hypothesis 3. Figure 2a shows the race by situational perspective taking interaction in predicting P-O fit. The index of partial moderated mediation was significant for gender (index = −0.42, CI.95 = −0.62, −0.28), indicating that the conditional indirect effect for the male managers (index = .54, CI.95 = 0.36, 0.77) was statistically stronger than for the female managers (index = .12, CI.95 = 0.02, 0.24), even after controlling for the effect of ethnicity, supporting Hypothesis 4. Figure 2b shows the gender by perspective taking interaction in predicting P-O fit.

Lastly, Hypothesis 5 predicted a three-way interaction between ethnicity, gender, and situational perspective taking of discrimination on organizational attraction via P-O fit, such that the effect of situational perspective taking on P-O fit will be stronger for White men than for all other demographic members. This three-way interaction was examined with the moderated moderated mediation. As shown in Table 2, the index of the moderated moderated mediation was significant (index = 0.64, CI.95 = 0.34, 0.96). As indicated by the conditional indirect effect of the moderators in Table 2, the indirect effect for White men was significant and larger (index = 0.97, CI.95 = 0.73, 1.19) than for all other demographic members. This interaction is depicted in Fig. 3.

Discussion

The results of study 1 showed that engaging in a situational perspective taking in which one imagines being the target of workplace discrimination led to more P-O fit, and subsequently to more organizational attraction toward an organization that has diversity management programs than those who did not engage in perspective taking. These results are consistent with the social perspective taking literature in that perspective taking generally leads to positive outcomes (Todd & Galinsky, 2014). However, the current study also provides the first known experiment in which the target of the perspective taking is structures (e.g., organizational support for diversity management programs) that would remediate the imagined situation (e.g., experiencing discrimination). The typical target of the perspective taking is a member of a stigmatized group, but the current study provides evidence that similar effects can occur toward structures that can reduce discrimination. Therefore, imagining one is the target of discrimination (i.e., a situational perspective taking) that can lead to positive attitudes toward organizations that invest in diversity management programs.

The results also showed that the effect of situational perspective taking was stronger for White managers and male managers. This finding is consistent with Avery’s (2011) theoretical model of diversity support, which proposed that racial minorities and women would be more supportive of diversity than majority members. The results of the current study found that it was White and male managers who were most influenced by the situational perspective taking manipulation. Without the manipulations, White and male managers had lower P-O fit and organizational attraction toward an organization that supports diversity management program. Thus, the current study suggests that situational perspective taking is a promising intervention that can lead to positive attitudes toward organizations that support diversity management programs.

Overview of Study 2

A second study was conducted to replicate the results of study 1 and to address the potential limitations of study 1 using a distinct sample. The managers in study 1 were full-time employees who were not active job seekers; thus, P-O fit and organizational attraction may have been influenced by the fact that the participants were not active job seekers. Therefore, study 2 used a sample of upper-level college students who were actively seeking jobs at a career fair.

In addition, study 1 did not have a control condition for the organizational support of diversity management programs. Ideally, the perspective taking manipulation should only have an influence on organizational attitudes in conditions in which an organization supports diversity management programs, but not in conditions in which this information is not known. Drawing from the organizational justice literature, Lind and van den Bos’ (2002) theory of uncertainty management states that applicants and employees use fairness perceptions to manage concerns about uncertainty. Individuals use any available information on fair treatment to develop global impressions of an organization’s fairness. Because diversity management is related to increasing fair treatment of all employees, it could also be used to decrease the uncertainty of an organization’s fairness. Lacking this information on fair treatment (i.e., diversity management) potentially increases uncertainty, which can negatively impact fit and attraction.

In addition, the theoretical rationale in the current study is that situational perspective taking of discrimination can make both factors from Avery’s (2011) model—self-interests and implicit expectations of a fair workplace—salient. When these factors are made salient through situational perspective taking, it can lead to greater perceived fit with an organization with diversity management, because the goal of diversity management (i.e., to increase fairness and equality) is made more compatible with one’s implicit expectation of intergroup equality. This then reduces the potential distress of discrimination (i.e., self-interests). Therefore, the effect of situational perspective taking on P-O fit and attraction should not occur when the diversity management of an organization is unknown. Study 2 examined if the effect of situational perspective taking on both P-O fit and organizational attraction would be stronger for organizations that support diversity management programs than when organizational support for diversity management programs is unknown. Thus, study 2 replicated Hypotheses 1 through 5 and tested additional hypotheses using a control condition for the organizational support of diversity management programs.

Hypothesis 6:

The effect of situational perspective taking on P-O fit will be stronger for organizations that support diversity management programs than when organizational support for diversity management programs is unknown.

Hypothesis 7:

The effect of situational perspective taking on organizational attraction will be stronger for organizations that support diversity management programs than when organizational support for diversity management programs is unknown.

Study 2

Method

Participants

The participants were 227 (53% female, 47% male) college students majoring in hospitality management attending a career fair focusing on hospitality organizations. The participants’ average age was 22.55 (SD = 5.03): 61.3% reported working part-time in the hospitality industry, 29.3% reported having a full-time job in the hospitality industry, and 9.3% reported as not currently employed. In regard to race, 45.8% of the participants identified as Caucasian/White, 24.4% identified as Latino(a)/Hispanic, 4.0% as African-American/Black, 19.6% as Asian, and 6.2% reported as “other.” The current study focused on college students attending a career fair, because all the participants were actively seeking employment at a career fair and therefore provided an opportunity to replicate study 1 with job seekers.

Design and Procedure

The current study used a 2(Perspective taking: yes or no) × 2(Organizational support for diversity management programs: yes or control) × 2(Race: White or minority) × 2(Gender: male or female) between-subjects experimental design. College students enrolled in upper-level hospitality management courses who attended a career fair were asked to complete a survey via an email in exchange for extra credit. After consenting to participate, they were informed that they were going to read about a hotel and make an evaluation of the hotel. Participants first read the same background information defining and describing diversity management programs from study 1.

After reading about diversity management programs, the first independent variable (Perspective taking: yes or no) was manipulated by having half of the participants engage in a situational perspective taking. The same situational perspective taking from study 1 was used. Participants in the control condition did not receive this manipulation and instead proceeded to the next section that included the same description of a hotel company used in study 1. However, the second independent variable, organizational support for diversity management programs (yes or control), was manipulated by either including the statement describing the hotel’s support of diversity management programs from study 1 or not. After reading about the hotel, the participants were asked to complete the dependent measures, demographic questions, and a manipulation check.

Measures

Person-Organization Fit

The same measure from study 1 was used. The reliability for this measure was 0.89.

Organizational Attraction

The same measure from study 1 was used. The reliability for this measure was 0.88.

Race

Using the same procedure from study 1, the non-Caucasian/White respondents were recoded as “ethnic/racial minority.” The final coding for race included 45.8% Caucasian/White and 54.2% ethnic minority respondents. A four-way MANOVA with ethnicity representing the four ethnic minority groups (Latino(a)/Hispanic, African-American/Black, Asian, and “other”) as the independent variable and P-O fit and organizational attraction as the dependent variables did not reveal a significant main effect for ethnicity (Wilks’s Λ = 0.89, F(6, 132) = 1.20, p > 0.05). Follow-up analysis of variance (ANOVA) for P-O fit (F[3, 66] = 1.62, p > 0.05; Latino(a)/Hispanic [M = 6.04, SD = 0.73], African-American/Black [M = 6.17, SD = 1.07], Asian [M = 5.71, SD = 0.42], and “other” [M = 6.00, SD = 0.0]) and organizational attraction (F[3, 66] = 0.17, p > 0.05; Latino(a)/Hispanic [M = 5.95, SD = 0.91], African-American/Black [M = 6.17, SD = 0.66], Asian [M = 5.89, SD = 0.82], and “other” [M = 6.00, SD = 0.0]) confirmed that the means for the different ethnic minority groups were not significantly different from each other.

Gender

Gender was dummy coded as 1 = male and 2 = female.

Manipulation Check

Participants were asked if they imagined being the target of workplace discrimination with a “yes/no” response scale. The written responses from the participants in the perspective taking condition were also reviewed to check that they wrote about being the target of discrimination. For the organizational support for diversity management programs manipulation, the participants were asked if the “hotel implements diversity management programs” with a “yes/no” response scale.

Results

Psychometric Analyses

A CFA demonstrated adequate fit: χ 2 = 100.88, df = 19, NFI = 0.93, IFI = 0.94, CFI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.15; all loadings were statistically significant and were higher than 0.50 (they varied from 0.63 to 0.92), indicating convergent validity (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988; Hair et al., 2010). The AVE was 0.71 for the P-O fit and 0.66 for organizational attraction, both greater than the 0.50 cutoff. The squared correlation between the measures (r 2 = 0.45) was lower than each AVE, demonstrating discriminant validity. This two-factor model was compared to a one-factor-model, which demonstrated poor fit and did not significantly improve the fit: χ 2 = 382.22, df = 20, NFI = 0.74, IFI = 0.75, CFI = 0.75; RMSEA = 0.283 (Δχ 2 = 281.34; Δdf = 1; p < 0.05).

Test of Hypotheses

In regard to the manipulation check, all of the participants in the perspective taking condition correctly identified they did imagine that they were the target of workplace discrimination; however, two participants in the non-perspective taking condition misidentified their condition and indicated that they imagined being the target of discrimination (the results remain unchanged with their inclusion). After reviewing the written responses from the participants in the perspective taking condition, one participant was dropped for not following the instructions. For the organizational support for diversity management programs manipulation check, three participants misidentified their condition, but their inclusion did not change the results.

The means, standard deviations, and correlations of the variables are shown in Table 3. Replicating study 1, hypothesis testing was also conducted by examining nested mediation, moderated mediation, and moderated moderated mediation models with the Preacher et al. (2007) bootstrapping procedure with confidence intervals that provide evidence of significant indirect effects when they exclude zero (Shrout & Bolger, 2002) using PROCESS version 2.13 for SPSS (Hayes, 2013). Hypothesis 1 predicted a direct effect of situational perspective taking on P-O fit and Hypothesis 2 predicted an indirect effect between situational perspective taking and organizational attraction through P-O fit. As shown in Table 4, both Hypotheses 1 and 2 were supported. Specifically, there was a significant direct effect of situational perspective taking on P-O fit, (β = 0.28, p < 0.01), and a significant indirect effect between situational perspective taking and organizational attraction through P-O fit (effect = 0.17, CI.95 = 0.07, 0.29).

Both moderators were examined simultaneously to replicate the test of Hypothesis 3 and Hypothesis 4. As shown in Table 4, support was found for gender as a moderator, but not ethnicity. Specifically, the index of partial moderated mediation was not significant for ethnicity (index = −0.14, CI.95 = −0.33, 0.01), not supporting Hypothesis 3, indicating that the moderating effect of ethnicity was not significant when controlling for the moderating effect of gender. Figure 4a shows the race by perspective taking interaction in predicting P-O fit. However, the index of partial moderated mediation was significant for gender (index = −0.27, CI.95 = −0.48, −0.12), indicating that the conditional indirect effect for the male managers (index = .29, CI.95 = 0.15, 0.49) was statistically stronger than for the female managers (index = .04, CI.95 = −0.12, 0.17), even after controlling for the effect of ethnicity, supporting Hypothesis 4. Figure 4b shows the gender by perspective taking interaction in predicting P-O fit.

Lastly, Hypothesis 5 predicted a three-way interaction between ethnicity, gender, and situational perspective taking of discrimination on organizational attraction via P-O fit, such that the effect of situational perspective taking on P-O fit will be stronger for White men than for all other demographic members. As shown in Table 2, the index of the moderated moderated mediation was not significant (index = 0.04, CI.95 = −0.28, 0.43), not supporting the indirect effect of the three-way interaction. However, as indicated by the conditional indirect effect of the moderators in Table 4, the indirect effect for White men was significant and larger (index = 0.44, CI.95 = 0.22, 0.72) than for all other demographic members. The conditional indirect effects of the moderators are depicted in Fig. 5.

Hypotheses 6 and 7 predicted that the effect of situational perspective taking on P-O fit (H6) and organizational attraction (H7) would be stronger for organizations that support diversity management programs than when organizational support for diversity management programs is unknown. This was tested with moderated models. The results showed a significant interaction effect between situational perspective taking and organizational support for diversity on P-O fit was significant (β = −0.19, p < 0.01). The conditional effect of situational perspective taking on P-O fit was significant for the condition in which the managers read that the organization supports diversity management (effect = 0.31, CI.95 = 0.14, 0.47), but not for the control condition (effect = −0.09, CI.95 = −0.28, 0.11).

The results also showed a significant interaction effect between situational perspective taking and organizational support for diversity on organizational attraction was significant (β = −0.14, p = 0.02). The conditional effect of situational perspective taking on organizational attraction was significant for the condition in which the managers read that the organization supports diversity management (effect = 0.42, CI.95 = 0.26, 0.58), but not for the control condition (effect = 0.12, CI.95 = −0.06, 0.32). These results demonstrate that the situational perspective taking manipulation had an influence on P-O fit and organizational attraction only in the condition in which an organization supports diversity management programs, but not for the control group, in which this information was not provided.

Discussion

Study 2 replicated most of the results of study 1 using a sample of university students who were also actively participating in a career fair seeking a job. In particular, the results showed that engaging in a situational perspective taking in which one imagines about being the target of workplace discrimination led to more P-O fit, and subsequently to more organizational attraction toward an organization that supports diversity management programs. These results also showed that the effect of the situational perspective taking was stronger for male participants, replicating study 1. However, unlike study 1, the moderating effect of ethnicity was not significant when controlling for the moderating effect of gender. These results suggest that for the study 2 sample, gender was a stronger moderator than race. It could be the case that age or generational differences (full-time managers versus college students) are an explanation for this difference in results. When examining the interaction of race and gender and perspective taking, the indirect effect for White men was significant and larger than for all other demographic members. Thus, the pattern of results for White men versus all other demographic members was similar across study 1 and study 2.

Study 2 also demonstrated that the situational perspective taking manipulation only had an influence on both organizational attitudes in the condition in which an organization supports diversity management programs, but not in the condition in which this information is not known. In particular, study 2 showed that the effect of perspective taking on both P-O fit and organizational attraction was present when participants read about the organization’s support of diversity management programs, but not when participants did not read about the organizational support for diversity management programs.

General Discussion

Taken together, the results of the two studies suggest that situational perspective taking is a promising intervention that can be used to increase positive attitudes toward organizational support for diversity management programs. The results were mostly consistent across two samples (i.e., full-time managers and university students seeking a job). Both studies showed that engaging in a situational perspective taking about being the target of workplace discrimination led to more P-O fit, which led to more organizational attraction toward an organization that supports diversity management programs than participants who did not engage in situational perspective taking. Furthermore, study 2 showed that this effect was absent in conditions in which participants did not read about organizational support of diversity management programs, suggesting that situational perspective taking about being the target of workplace discrimination leads to positive organizational attitudes specifically toward an organization that supports diversity management programs. This particular finding also suggests that situational perspective taking does not lead to social desirability or more general positive attitudes. Moreover, both studies showed that the effect of situational perspective taking had a greater impact on White male participants than minorities and female participants, supporting Avery’s (2011) theoretical model of diversity support.

Theoretical Contributions

The current studies suggest several theoretical implications for influencing support of diversity management programs. First, despite theoretical work that suggests organizational attitudes are an important factor for the effectiveness of diversity management programs (Avery, 2011; Yang & Konrad, 2011), this is the first known research that explores an intervention to increase positive attitudes toward organizations that have diversity management programs. The results showed that situational perspective taking can help individuals see the value in diversity management programs. The current findings inform and extend theoretical understanding in how to build support for diversity, such as Avery’s (2011) model of diversity endorsement, by illustrating that situational perspective taking of discrimination can lead to greater attraction toward an organization with diversity management through P-O fit.

It was theorized that the process in which this occurs is through the self-interests and implicit expectations of a fair workplace, which are made salient when one imagines being the target of workplace discrimination. By activating self-interests and implicit expectations of a fair workplace through situational perspective taking, individuals perceive greater fit with an organization implementing diversity management, because the goal of diversity management (i.e., to increase fairness and equality) is made more compatible with one’s implicit expectation of fair treatment (i.e., ideological beliefs in intergroup equality) and reduction of the potential distress of discrimination (i.e., self-interests).

Avery’s (2011) model also states that minority status is a predictor of diversity endorsement. The results of the current study, however, showed that engaging in situational perspective taking of discrimination can influence the effect of minority status on diversity endorsement. In particular, White men’s attitudes were positively influenced by engaging in situational perspective taking more than White women, minority men, and minority women. Thus, the current results also advance Avery’s (2011) model showing that the link between minority status and diversity endorsement can be influenced to include non-minority men.

Study 1 also provides implications for how managers who are seeking new organizations can be influenced by situational perspective taking. For example, diversity management programs tend to focus on reducing barriers and discrimination against minority applicants and employees in regard to employment decisions that are typically made by managers (e.g., selection, promotion, and development). Managers are not only responsible for interviewing and selecting applicants but also training, appraising, rewarding, and developing their employees. If managers have negative attitudes toward an organizations’ support of diversity management programs, managers may be less likely to implement and follow through with the diversity management programs (Thomas, 2008). Thus, organizations hiring new managers can use situational perspective taking to positively influence managers’ attitudes toward the organization that implements diversity management programs.

The current paper also suggests that situational perspective taking about being the target of workplace discrimination can lead to more positive attitudes toward an organization that supports diversity management programs among active job seekers (study 2). This is particularly important because as more organizations are investing in diversity management programs (Avery, 2011; Dobbin, Kim, & Kalev, 2011; Madera, 2013), many organizations are using recruitment activities, such as corporate websites, to advertise their support of diversity (Walker, Feild, Bernerth, & Becton, 2012). Job seekers may use these diversity cues to make assessments about the organization. The results of the current paper suggests that situational perspective taking increased P-O fit, which was positively related to organizational attraction toward an organization that does indeed advertise their support of diversity management programs.

The current paper also makes a significant contribution to the use of situational perspective taking. The typical target of perspective taking, both social and situational, is a member of a stigmatized group and the outcomes focus on attitudes toward members of the stigmatized group (e.g., African-American, a person with HIV/AIDS, an addict, or a homeless person; Todd & Galinsky, 2014). A gap in this literature is if situational perspective taking could also lead to positive attitudes toward organizations that have structures (e.g., diversity management programs) that would remediate the imagined situation (e.g., experiencing discrimination). Just as social perspective taking leads to positive attitudes and feeling toward others, the current results suggest that situational perspective taking of discrimination can lead to positive attitudes toward organizations that have diversity management programs. Imagining being the target of discrimination invokes personal distress (Batson, Early, & Salvarani, 1997; Batson et al., 1997), which primes egocentrism to maintain a positive view of the self, consequently, leading to individuals protecting themselves (Crocker & Wolfe, 2001) and maintain the implicit expectation of fair treatment, making organizations that have diversity management programs a better fit and more attractive than organizations that do not.

Practical Implications

The current paper has practical value for organizations that use recruitment activities, such as corporate websites, to advertise their support of diversity. Specifically, there are at least three avenues for how organizations can use situational perspective taking of discrimination. First, situational perspective taking prompts can be included in the descriptions of an organization’s diversity management on corporate websites. Many corporate websites include diversity statements and/or descriptions of their various programs, and therefore can also include statements that lead them to situational perspective taking, such as “imagine you are the target of discrimination… our programs are here to ensure an inclusive environment that protects you.” Potential applicants looking through this page might then read this prompt and engage in situational perspective taking, positively influencing their P-O fit and organizational attraction.

Second, situational perspective taking prompts can also be used in sections of the website listing the benefits for working at a particular organization. For example, corporate websites often have “why work for us” sections outlining various benefits. Situational perspective taking prompts (e.g., “imagine you are the target of discrimination… ”) can also be used to explain why an organization’s diversity management is a benefit for all employees. Third, the results suggest that in the recruitment context it would be ideal that organizations have situational perspective taking prompts as someone potentially applies to an organization. This intervention needs active participation, so organizations can have applicants engage in situational perspective taking during the application process and then proceed with a description of their diversity management as beneficial to all. This is particularly feasible using online applications. In fact, due to the advances of technology, organizations often have online applications that include multiple screener questions and various assessments that require active participation by the applicants (Stone, Deadrick, Lukaszewski, & Johnson, 2015).

By emphasizing that these programs protect all future applications/employees, organizations are priming applicants to recognize that they can be targets of discrimination in organizations that do not support diversity management programs. In doing so, organizations can increase applicant perceived fit and attraction. This is particularly important for organizations who are actively recruiting women and ethnic minorities (Walker et al., 2012), but do not want to disaffect White and male applicants (Unzueta & Binning, 2012). The results of the current study showed that situational perspective taking of being the target of discrimination led to higher fit and organizational attraction for all, but this effect was greater for White and male individuals. Therefore, not only can organizations attract women and ethnic minorities through the design of recruitment activities that highlight their support of diversity management programs but they can also increase the fit and attraction of White and male applicants using the same methods.

Another practical implication for organizations is that situational perspective taking can be used to increase support of diversity management programs among current managers, particularly for White and male mangers. Qualitative research has suggested that diversity management programs are effective if managers are integrated in the diversity management strategic goals and plans that are implemented by top management (Benschop, 2001; Furunes & Mykletun, 2007; Madera, 2013; Thomas, 2004). For instance, Thomas (2004) reported that mandatory diversity training for all managers was part of IBM’s success in launching their diversity management initiative. Similarly, Madera (2013) found that hospitality and service organizations that were rated as the best companies for diversity made diversity training mandatory for all managers. Managers are vital for implementing diversity management programs, because many of these programs focus on reducing discrimination among employees related to selecting, appraising, developing, and promoting women and ethnic minorities, which are decisions that are mostly contingent on managers (Kalev et al., 2006; Thomas, 2008). Thus, the current study found support that situational perspective taking is an intervention that can potentially lead to positive attitudes toward organizational support for diversity management programs.

Limitations and Future Research

Although the present studies yielded consistent findings, there are potential limitations worth noting that can also lead to future research. One potential limitation is related to the operationalization of the perspective taking manipulation. In both study 1 and study 2, the participants were asked to imagine being the target of discrimination in general, rather than imagining a specific type of discrimination (e.g., racial, gender, age, disability). Because different types of discrimination have the potential to influence reactions (Thomas, 2008), future research might examine how specific types of discrimination can interact with demographic characteristics to influence attitudes toward organizational support of diversity management programs. For example, for White participants, imagining racial discrimination might lead them to think of “reverse discrimination,” which is often linked to diversity management efforts giving preferential treatment to racial minorities. Therefore, thinking about racial discrimination might prime thoughts of “reverse discrimination,” which would lead to negative attitudes toward diversity management (Ku, Wang, & Galinsky, 2015).

Another potential limitation is that the current studies did not examine how long lasting the effects are, which provides an area for future research. In fact, the typical perspective taking manipulation in the literature has not examined the effect of time, which provides a great need to examine how long the effects of perspective taking lasts. This is an important area for future research, because social desirability is a potential limitation when perspective taking and measures of the outcomes occur within the same timeframe. Separating the manipulation and the measure of the outcomes in two time points can address how long the effects last and avoid social desirability. The current studies do provide some evidence to suggest that social desirability was minimized. First, using a cover story, filler materials, and filler items were some procedural methods to reduce the potential effect of social desirability. This was consistent with the perspective taking literature. Second, the moderating effects suggest that the manipulation had real effects that go above and beyond any potential social desirability effects. That is, if the results were due only to social desirability, then gender or ethnic differences would not have emerged, because social desirability would have an equal effect on every group member.

Third, in study 2, the main effect of perspective taking was not significant in the condition in which the participants did not receive information about the organization’s diversity management programs. This finding indicates that social desirability did not lead to more P-O fit and organizational attraction when participants were asked to engage in situational perspective taking, because the perspective taking manipulation only had an influence on organizational attitudes in conditions in which participants read about an organization’s support of diversity management programs. In other words, if social desirability played a role, then the effect of perspective taking would have also been significant in the condition in which the participants did not receive information about the organization’s diversity management programs.

Lastly, the current studies examined situational perspective taking of discrimination as intervention to influence attitudes toward diversity management in the recruitment context. Future research can examine this intervention in other contexts. The results of the current studies are consistent with the literature in that perspective taking leads to positive attitudes. Thus, there are reasons to expect that these results can be generalized to other contexts using other outcome variables. Other contexts include having current employees engage in a situational perspective taking exercise as part of diversity training. Outcome measures in this context might include the perceived utility of diversity management or fairness of diversity management. Because the current results showed the positive effect of situational perspective taking of discrimination in a recruitment context, it is possible that current employees engaging in perspective taking would also perceive diversity management as useful and fair. Similar mechanisms might play a role in increasing the perceived utility of diversity management or fairness of diversity management. By activating self-interests and implicit expectations of a fair workplace through perspective taking, employees might then perceive the utility and fairness of diversity management programs.

Another context can include new employees who engage in a situational perspective taking as part of their employee orientation. Similar to the current study, new employees might perceive more fit with their new organization after engaging in situational perspective taking during orientation that includes information about the organizations diversity management efforts. Situational perspective taking might help new employees understand why their organizations implement their diversity management programs.

A third context to examine situational perspective taking is when organizations are introducing new diversity management programs. The current research suggests that situational perspective taking of discrimination can lead to positive attitudes toward diversity, so it is possible that in this particular context, situational perspective taking can be used to influence positive attitudes toward a new type of diversity management program. In all three proposed contexts, the current results can guide future research examining these empirical inquiries.

Conclusion

Across the two studies, the current research showed that engaging in a situational perspective taking in which one imagines being the target of workplace discrimination leads to more P-O fit, which then leads to more organizational attraction toward an organization that has diversity management programs. These results also showed that the effect of situational perspective taking was stronger for White and male participants than for ethnic minorities and women. Thus, this paper provides a potential intervention that can be used to increase positive attitudes toward organizations that invest in diversity management programs, which is paramount for the effectiveness of diversity management programs (Avery, 2011; Yang & Konrad, 2011). These results also suggest that the design of organizational recruitment activities should highlight their support of diversity management programs and emphasize that all member benefit from diversity management programs.

References

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411.

Avery, D. R. (2011). Support for diversity in organizations: A theoretical exploration of its origins and offshoots. Organizational Psychology Review, 1(3), 239–256.

Avery, D. R., Hernandez, M., & Hebl, M. R. (2004). Who’s watching the race? Racial salience in recruitment advertising. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(1), 146–161.

Avery, D. R., & McKay, P. F. (2006). Target practice: An organizational impression management approach to attracting minority and female job applicants. Personnel Psychology, 59(1), 157–187.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. doi:10.1007/BF02723327.

Batson, C. D., Chang, J., Orr, R., & Rowland, J. (2002). Empathy, attitudes, and action can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group motivate one to help the group? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 1656–1666.

Batson, C. D., Early, S., & Salvarani, G. (1997a). Perspective taking: Imagining how another feels versus imagining how you would feel. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 751–758.

Batson, C. D., Sager, K., Garst, E., Kang, M., Rubchinsky, K., & Dawson, K. (1997b). Is empathy-induced helping due to self-other merging? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 495–509.

Benschop, Y. (2001). Pride, prejudice and performance: Relations between HRM, diversity and performance. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 12(7), 1166–1181.

Berdahl, J. L., & Moore, C. (2006). Workplace harassment: Double jeopardy for minority women. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(2), 426.

Blaine, B., & Crocker, J. (1993). Self-esteem and self-serving biases in reactions to positive and negative events: An integrative review. In Self-esteem (pp. 55–85). Springer US.

Bond, M. A., & Haynes, M. C. (2014). Workplace diversity: A social–ecological framework and policy implications. Social Issues and Policy Review, 8(1), 167–201.

Cable, D. M., & Judge, T. A. (1996). Person–organization fit, job choice decisions, and organizational entry. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 67,(3), 294–311.

Carless, S. A. (2005). Person–job fit versus person–organization fit as predictors of organizational attraction and job acceptance intentions: A longitudinal study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78(3), 411–429.

Chapman, D. S., Uggerslev, K. L., Carroll, S. A., Piasentin, K. A., & Jones, D. A. (2005). Applicant attraction to organizations and job choice: A meta-analytic review of the correlates of recruiting outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(5), 928.

Chavez, C. I., & Weisinger, J. Y. (2008). Beyond diversity training: A social infusion for cultural inclusion. Human Resource Management, 47, 331–350.

Chen, C. C., & Hooijberg, R. (2000). Ambiguity intolerance and support for valuing-diversity interventions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 2392–2408.

Cialdini, R. B., Brown, S. L., Lewis, B. P., Luce, C., & Neuberg, S. L. (1997). Reinterpreting the empathy-altruism relationship: When one into one equals oneness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 481–494.

Crocker, J., & Wolfe, C. T. (2001). Contingencies of self-worth. Psychological Review, 108(3), 593–623.

Cundiff, N. L., Nadler, J. T., & Swan, A. (2009). The influence of cultural empathy and gender on perceptions of diversity programs. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 16, 97–110.

Davis, M. H., Conklin, L., Smith, A., & Luce, C. (1996). Effects of perspective taking on the cognitive representation of persons: A merging of self and other. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 713–726.

Dineen, B. R., & Soltis, S. M. (2010). Recruitment: A review of research and emerging directions. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of I/O psychology, Selecting and developing members for the organization (Vol. 2, pp. 43–66). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Diversityinc.com (2016). Who has the best website for diversity? Retrieved from http://www.diversityinc.com/diversity-management/ask-diversityinc-who-has-the-best-website-for-diversity/

Dobbin, F., Kim, S., & Kalev, A. (2011). You can’t always get what you need organizational determinants of diversity programs. American Sociological Review, 76(3), 386–411.

Dovidio, J. F., Ten Vergert, M., Stewart, T. L., Gaertner, S. L., Johnson, J. D., Esses, V. M., Riek, B. M., & Pearson, A. R. (2004). Perspective and prejudice: Antecedents and mediating mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1537–1549.

Elkins, T. J., & Phillips, J. S. (2000). Job context, selection decision outcome, and the perceived fairness of selection tests: Biodata as an illustrative case. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 479–484.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. doi:10.2307/3151312.

Furunes, T., & Mykletun, R. J. (2007). Why diversity management fails: Metaphor analyses unveil manager attitudes. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 26(4), 974–990.

Galinsky, A. D., & Ku, G. (2004). The effects of perspective-taking on prejudice: The moderating role of self-evaluation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 594–604.