Abstract

Objectives

The ACT Raising Safe Kids Program is a research-based parenting intervention developed by the American Psychological Association to teach caregivers positive parenting skills and prevent violence. It has been implemented and evaluated in several countries. This study conducted a systematic review of the literature evaluating the ACT Program to identify its current state of the art.

Methods

Reporting follows PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols) guidelines. Searches were conducted from 2000 to October 2018 in the following databases: CAPES, PsycINFO, SciELO, Scopus and Web of Science.

Results

Thirteen empirical studies evaluating the program were found: 3 evaluated workshops for facilitators and 10 evaluated caregiver-training programs. All studies reported positive effects of the ACT program on knowledge held by both facilitators and caregivers, such as significant increase of positive parenting and decrease of corporal punishment. Overall 10 studies demonstrated the effectiveness of the program, 4 of these using quasi-experimental research designs and 6 studies through pre-experimental research designs. Three assessed the program’s efficacy by using experimental group designs with randomized controlled trials (RCT). Retention rates of the interventions are compared and research strategies to foster retention are listed. The authors of the studies identified the data collected exclusively on self-reports as one of the main limitations, and suggested the use of third-party information and/or observational measures to evaluate direct behavior changes.

Conclusions

The ACT Program’s current state of the art is promising, and further RCT studies are needed to consolidate it as an evidence-based parenting program.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Global statistics portray a worrisome picture of violence against children. It is estimated that 1.1 billion caregivers worldwide, or just over 1 in 4 parents believe in corporal punishment as a form of discipline (United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF] 2017). UNICEF’s report (2017), based on data gathered from 30 different countries, shows that approximately half of children aged 12 to 23 months experience physical violence at home during their upbringing, and a similar proportion of children are exposed to verbal or psychological violence. According to the report, three-quarters of 2 to 4-year-olds (approximately 300 million individuals) are victims of violent discipline methods (physical and/or psychological) perpetrated by parents or caregivers at home. Furthermore, throughout the world, six out of every 10 children (250 million individuals) experience corporal punishment during their upbringing.

The consequences of violence perpetrated against children can be devastating to child development. A meta-analysis encompassing data gathered from over 36,000 people, as well as from 88 studies on the subject, have confirmed that corporal punishment in its various forms is related to the increase in aggressive, antisocial, and delinquent behavior in children; deterioration of parent-child relationships; child mental health problems, and a greater propensity of becoming a victim of physical violence (Gershoff 2002). The meta-analysis also suggested increased risk of aggressive and antisocial behavior to be manifested in adulthood along with mental health problems and increased risk of perpetrating violence against one’s own spouse or child.

Additionally, research indicates that children who have suffered a particular type of violence are at increased likelihood of suffering another modality of violence: for instance, according to Finkelhor (2011), if a child is physically assaulted by a caregiver, he/she is 60% more likely to suffer violence from their peers than other children are. In their study, 22% of 2030 children ages 2–17 had experienced 4 or more kinds of victimization over the last year, phenomenon called poly-victimization (Finkelhor et al. 2007). Likewise, in a study by Pinheiro and Williams (2009) in Brazilian schools, children who were victims of at least one modality of violence committed by their mothers were 3.2 times more likely to have bullying involvement as a victim or a perpetrator. In the same study, results showed that the likelihood of engaging in bullying increased as the degree of violence perpetrated by the father against the child increased. Boys who suffered mild physical violence by the father were 4.1 times more likely to bully or be bullied; the odds ratio increased to be 7 in case of moderate physical violence and 8.5 times greater in case of severe physical violence by the father.

Although the negative side effects resulting from the use of violence as a modality of child discipline have been attested, this practice tends to be replicated later on by the offspring through the intergenerational phenomenon of violence, as the parents’ history of violence is a risk factor contributing to their children’s involvement in acts of violence, thus relaying their violent educational practices from generation to generation (Berlin et al. 2011; Marin et al. 2013). According to Barnett (1997), 30% of abused children will abuse or neglect their own children in the future, and 70% of parents who mistreat their children had been mistreated as children. These findings are consistent with Bandura’s Theory of Social Learning (1977), since what children learn as the norm in a violent home serve as role model for how to behave in social interactions.

Thus, violence preventive measures are considered to be essential in avoiding adverse consequences in child development and in the promotion of children’s well-being. Primary or universal violence prevention programs, i.e. programs that involve efforts to reduce the incidence of a problem before it occurs (in this case violence), are important in attempting to halt the cycle of violence, preventing that it perpetuates itself, and enabling children to develop properly free from violence (Wolfe and Jaffe 1999). Two universal violence prevention parenting programs have been implemented in various parts of the world: the Triple P - Positive Parenting Program which originated in Australia (Sanders et al. 2014), and the ACT Raising Safe Kids parenting Program (Silva 2009), developed by the American Psychological Association (APA) emphasizing the importance of quality of parent-child relationship for promoting healthy development of children. This last program is the focus of the present study.

The ACT Raising Safe Kids Program (ACT-RSK) was developed by the Violence Prevention Office (VPO) of the APA in collaboration with the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) in the United States to divulge findings resulting from scientific research on four targeted areas of early violence prevention: Anger Management, Social Problem-Solving, Discipline and Media Violence. These areas were organized in modules that can be disseminated to adults who either raise or work with children. In doing so, the ACT program attempts to fill the gap left by the scarcity of programs dedicated to the prevention of early childhood violence (Silva and Randall 2005).

The ACT is a universal violence prevention program that seeks to enable multidisciplinary professionals to disseminate knowledge and skills to prevent violence perpetrated against children and to teach positive parenting to parents or caregivers of children aged from 0-8 years in a group format (Silva 2009). The program was based on the categories established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) concerning best practices of youth violence prevention (Thornton et al. 2002) and on Albert Bandura’s Social Learning theory (Bandura1977).

The program is based on the following tenets: violence results from the lack of problem-solving skills and social skills required for dealing with conflicts; children learn through observation and imitation; if children develop social skills they will be more likely to avoid involvement in violent conflict; adults can learn to be role models and teach children social skills; and this will help them deal with their social relationships in a non-aggressive manner (Silva and Randall 2005).

The current version of the ACT Program contains the following materials: Parent’s Handbook, Children’s Activities Guide, Facilitator Manual, Motivational Interviewing Manual, and Evaluation Guide (Silva 2009). The program consists of eight sessions, approaching the four modules of the program: 1. Understanding your children’s behavior; 2. Young children’s exposure to violence; 3. Understanding and controlling parent’s anger; 4. Understanding and helping angry children; 5. Children and electronic media; 6. Discipline and parenting styles; 7. Discipline for Positive Behaviors; and 8. Taking the ACT Program with you. In addition, the program suggests an initial session, which is regarded as a Pre-Program Meeting, in which the facilitator and participants get to know each other, determine the group’s rules, and fill out pre-program measures. Thus, in total, the program comprises of nine sessions.

Professionals are authorized to conduct the ACT Program if trained at two-day workshops conducted by ACT coordinators or master trainers, filling out the checklist while conducting the program for the first time and submitting a video recording of the sixth session of the conducted group in order to get certified as ACT Facilitators. The ACT Program has been implemented in more than 80 communities in different countries (Howe et al. 2017); and it was recently listed by the World Health Organization (WHO 2018) as one of the seven inspiring “selected strategies based on the best available evidence” (p. 3) for reducing violence against children at low or no cost. Among the program’s strengths, Knox et al. (2011) highlight the fact that there are well-written manuals in English and Spanish (now also available in Portuguese, Greek, Turkish, Croatian, Bosnian, Romanian, Japanese and Mandarin), with detailed instructions directed at the facilitators, which contribute to the accuracy of its application. The fact that the ACT program offers an affordable model of dissemination was also highlighted. The same authors also point out that ACT is the only parenting training program that educates caregivers about the negative effects regarding exposure to violence in the media, offering strategies to mitigate such exposure.

A systematic review of the program has not yet been conducted, although the ACT program has been the source of specific reviews for different purposes (Altafim and Linhares 2016; Howe et al. 2017; Silva and Williams 2015). Thus, the intent of this article is to systematically review the ACT Program’s assessment studies, which will be described and compared methodologically to highlight advances, shortcomings, and future possibilities concerning the evaluation of the program, thus circumscribing its current state of the art.

Method

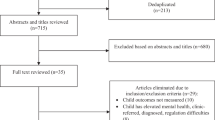

We employed the recommendations of the PRISMA Protocol (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols) proposed by Moher et al. (2009) as the guiding principles for this systematic review. The protocol consists of a checklist containing several items and sub-items and a four-phase flow diagram, which is considered to be essential for transparently reporting a systematic review or meta-analysis.

Search Strategy

Searches using the keywords “ACT” and “Raising Safe Kids” and “ACT against violence” were conducted in the following databases: CAPES, PsycINFO, SciELO, Scopus and Web of Science for articles published in the period ranging from the year 2000 (when the program was created) to October of 2018. Inclusion criteria involved published articles concerning empirical studies with clarity of methodology evaluating interventions of the ACT Program that were presented with fidelity to the original program (group applicability). Studies that did not fulfill any of these criteria were not selected.

As you can see in the flow diagram of the selection process (Fig. 1), 200 references resulted from the initial database searching, and of these 31 were duplicates. While evaluating the title and/or abstract of the 169 remaining references, only 24 were articles related to the ACT Raising Safe Kids Program. Upon reading the articles in full and based on the criteria previously described, 11 were excluded from the study. The 13 studies that met the criteria were subsequently analyzed.

The PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process. N/A not available (adapted from Moher et al. 2009)

Data Analyses

Descriptive and comparative analyses were conducted regarding the target audience, research design, sample size, evaluation measures, results, limitations and research suggestions of each study. We categorized the study designs as: experimental (group-based design with randomized controlled trial - RCT); quasi-experimental (with a non-equivalent control group or without RCT), according to Cozby’s classification (2008), or as pre-experimental (only one group undergoes pre-, post- and/or follow-up measures), as defined by Campbell and Stanley (1963).

Regarding program evaluation, the concepts of efficacy and effectiveness must be differentiated to proper analyze the results of the intervention. O’Connell et al. (2009) define efficacy as the impact a program has under ideal conditions and effectiveness as the impact a program has under conditions likely to occur with real-world implementations (imperfect and not ideal). In the specific context of Psychology, Meltzoff (1997) conceptualizes efficacy as a rigorously controlled study of patients with a well-defined disorder, randomly assigned to a number of fixed sessions according to what is prescribed in the treatment manual. The author conceptualizes effectiveness as a study exerting less control, in which the patients with a variety of different disorders, with no fixed treatment guide, and with a flexible therapy time-span would be evaluated for the benefits of the treatment. In the present review, experimental studies, with a randomized controlled trial (RCT) were classified as evaluating the efficacy of the study, while the remaining research designs were classified as evaluating the effectiveness of the study.

Results

Thirteen articles evaluating the ACT Program were analyzed in this systematic review. All of the studies are empirical in nature; three of them evaluated the training workshop for professionals (Guttman et al. 2006; Miguel and Howe 2006; Thomas et al. 2009) and 10 evaluated training programs for parents and caregivers (Altafim et al. 2016; Burkhart et al. 2013; Knox and Burkhart 2014; Knox et al. 2010, 2011, 2013; Pedro et al. 2017; Porter and Howe 2008; Portwood et al. 2011; Weymouth and Howe 2011).

Evaluation of the ACT Training Workshop for Professionals

The first two empirical studies published involving the ACT Program (Guttman et al. 2006; Miguel and Howe 2006), along with the study by Thomas et al. (2009), sought to evaluate the effects of the ACT training workshop on child care professionals. The studies of this group evaluated the impact of the ACT training workshop with regard to the acquisition of knowledge and skills in the area of violence prevention (Miguel and Howe 2006; Thomas et al. 2009), as well as participants’ knowledge levels and perception of knowledge gained (Guttman et al. 2006). As secondary goals, Guttman et al. (2006) and Miguel and Howe (2006) were interested in the evaluation of the dissemination of the program in the community: Guttman et al. (2006) addressed this by means of the analysis of the perceived usefulness of the modules to be used by psychologists in their practice, and Miguel and Howe (2006) addressed it through the assessment of ACT’s train-the-trainer method of dissemination. Conversely, the study conducted by Thomas et al. (2009) had as secondary goal developing a reliable and valid outcome measure to assess the effectiveness of the ACT Training Program.

Miguel and Howe (2006) evaluated a 14-hour, two-day ACT training workshop, whereas Guttman et al. (2006) evaluated the impact of a 3–4 h training workshop, and the study by Thomas et al. (2009) evaluated a workshop that consisted of five weekly 90-minute sessions dedicated to the ACT training. Such configurations must be taken into account while evaluating the results that were obtained. Table 1 illustrates the participants’ profile, the sample size in the post-test and follow-up (n/n) - if the study has both, evaluation measures employed, research design, and results achieved in the studies.

The first two studies that analyzed the ACT training workshop for professionals evaluated its effectiveness by conducting respectively pre-experimental (Guttman et al. 2006) and quasi-experimental studies (Miguel and Howe 2006), while Thomas et al. (2009) conducted the first study of the ACT Program that evaluated the efficacy of the training workshop on the participants. In terms of evaluation measures used, Miguel and Howe (2006) developed the ACT Evaluation Scenarios, which evaluated participant’s knowledge and skills by answering open-ended questions on child development and violence prevention through eight different scenarios, two scenarios for each age group (infant, toddler, preschool, school-age). Thomas et al. (2009) improved the assessment tool by incorporating quantitative measures (multiple choice responses) to the scenarios and additional questions to measure the knowledge gain of participants in the four training modules of the program, naming it the ACT Evaluation Questionnaire.

As limitations of the study, Miguel and Howe (2006) mentioned the absence of psychometric data available in larger scale studies regarding the measures used, suggesting that future studies may focus on the reliability and validity of these measures, as well as they might assess the degree of fidelity to program curricula. Guttman et al. (2006) identified the lack of random assignment of participants, participant characteristics and the absence of follow-up measures as limiting factors in the generalization of the study. Both studies also recognized as limitation the fact that the results were exclusively based on self-reports without employing observational measures or objective behavior evaluations. Thomas et al. (2009) argue that it is impossible to generalize the study as it had a small sample and was conducted in only one geographic region; that the randomization of groups could have been more rigorous and that the use of the same scenarios in the pre, post-test, and follow-up sessions could have influenced participants’ “learning process”, thus suggesting the use of different scenarios for future studies. Only one experimental study addressing the ACT workshop for professionals has been conducted, thus more studies are needed to prove the efficacy of such training initiative.

Evaluation of the ACT Training Program for Parents or Caregivers

With the exception of the study conducted by Thomas et al. (2009), articles published since 2008 fall into this second category, and evaluate the efficacy or effectiveness of the ACT training administered to parents and/or caregivers by certified facilitators. Eight of the 10 studies sought to evaluate the effect of the program based on parent/caregiver self-report measures concerning the following: maternal parenting and children’s behavior (Altafim et al. 2016, Pedro et al. 2017); positive parenting behaviors and aggressive behavior toward children (Knox et al. 2013); level of skill and knowledge acquisition by caregivers (Weymouth and Howe 2011; Porter and Howe 2008), as well as frequency of physical punishment by the latter; parents’ knowledge, behaviors, and attitudes (Portwood et al. 2011); and parenting beliefs and behaviors as well as harsh parenting practices - spanking and hitting children with objects (Knox et al. 2010).

The two remaining articles stand out because they have different and unprecedentedly unique objectives for evaluation studies of the ACT Program: to evaluate the ACT Program’s effect exclusively based on the behavior problems of the children (Knox et al. 2011); and on reducing early childhood bullying, as well as examining its relationship to parent characteristics - hostility, depression, and overall parenting skills (Burkhart et al. 2013). The studies conducted by Burkhart et al. (2013) and Knox et al. (2010, 2011) used the same database for different purposes: in the first, the behavior of parents and their discipline strategies were evaluated. The studies conducted by Altafim et al. (2016), Knox and Burkhart (2014) and Pedro et al. (2017) had innovative secondary goals: Altafim et al. (2016) sought to compare the effectiveness of the program according to the age of the children; Knox and Burkhart (2014) sought to evaluate whether participants had any characteristics that favored treatment outcomes and retention to the program; and Pedro et al. (2017) compared the outcomes of the intervention combining families from different socioeconomic contexts with children enrolled in public or private schools.

Table 2 describes the empirical studies evaluating the ACT intervention with parents according to the experimental rigor (experimental, quasi-experimental and pre-experimental). When more than one study employs the same design, the study is placed in chronological order. Accordingly, two studies used experimental design (Knox et al. 2013; Portwood et al. 2011), with randomized experimental and control groups and pre-test and post-test measures, and as was the case with Portwood et al. (2011), follow-up measures were also included; three studies had a quasi-experimental design with non-randomized intervention and control groups and pre and post-test measures (Burkhart et al. 2013; Knox et al. 2010, 2011); five studies employed pre-experimental designs (Altafim et al. 2016; Knox and Burkhart 2014; Pedro et al. 2017; Porter and Howe 2008; Weymouth and Howe 2011), with pre and post-test measures for only one group and various subgroups distributed throughout the same locality in Brazil (Altafim et al. 2016; Pedro et al. 2017), distributed in various cities throughout America (Weymouth and Howe 2011), in three different American States (Knox and Burkhart 2014), and with pre-test, post-test, and follow-up measures (Porter and Howe 2008). Two studies bear a design that evaluates the efficacy of the ACT Program (Knox et al. 2013; Portwood et al. 2011); making use of RCT considered to be methodologically rigorous as an evidence-based research criterion, and eight studies evaluated the effectiveness of the program (Altafim et al. 2016; Burkhart et al. 2013; Knox and Burkhart 2014; Knox et al. 2010, 2011; Pedro et al. 2017; Porter and Howe 2008; Weymouth and Howe 2011).

As for the participants that were targeted, six of the ten studies involved participants belonging to vulnerable social groups (Burkhart et al. 2013; Knox et al. 2010, 2011, 2013; Porter and Howe 2008; Weymouth and Howe 2011), such as caregivers referred by the court, some of them involved in substance abuse, low-income adults, residents of rural areas who were exposed to multiple stressors (e.g., homeless families), underinsured and uninsured immigrants from Latin America and poor ethnically diverse populations who have poor or no healthcare coverage, drug users, and incarcerated parents. The remaining four studies were able to envision universal prevention through their recruitment: in the studies conducted by Altafim et al. (2016) and Pedro et al. (2017) mothers were recruited from schools and family health centers; in Portwood et al. (2011) participants came from social service agencies and parent programming sites; and in Knox and Burkhart (2014) participants were recruited from elementary schools, community agencies, as well as a children’s advocacy center. The last authors, as well as Portwood et al. (2011), mentioned that the focus of their recruitment was not to select parents who used corporal punishment, emphasizing a more preventive rather than remediating approach.

Positive results were achieved in all of the studies evaluating the ACT training, either in terms of reduction in use of corporal punishment, improvement of knowledge, as well as in skills and beliefs held by participants regarding media violence, positive parenting behavior, child development, anger management, social problem-solving, reduction of bullying and harsh parenting, or changes in children’s behaviors before and after the ACT intervention. In the study conducted by Porter and Howe (2008), as well as in the Miguel and Howe (2006) and Thomas et al. (2009) studies evaluating the workshop for facilitators, some of the scores obtained during the follow-up presented a significant increase when compared to the pre-test scores.

Table 3 illustrates in percentages participants’ retention to the 10 empirical studies evaluating the ACT intervention for parents/caregivers in descending order of post-test rates along with the sample size at different stages of each study. To calculate the study’s retention rates both number of participants who began the intervention and number of participants who completed it were considered (using as minimum criterion participation in at least 7 sessions, and filling out the studies’ instruments). Thus, the final post-test and/or follow-up sample size was the number considered for calculating retention rates, and may not coincide with the retention rates reported by the original studies’ authors.

The retention rates of the ACT Evaluation studies ranged from 53 to 86% in the post-test. Although total participant retention in Pedro et al.’s (2017) program was of 56%, as shown in Table 3, it is possible to distinguish retention rates based on the Brazilian socioeconomic groups involved in the study: 51% of retentions in the low-income group (C-Public School); 48% in the middle-income group (B-Public School); and the larger retention (76%) in the higher-income group (B-Private School).

The study conducted by Knox and Burkhart (2014) sought to examine whether or not participants displayed a pattern with regard to dropping out, concluding that younger parents quit the program significantly more than older parents and the latter were more likely to achieve improvements in the behaviors of the child following the intervention. Parent age was, therefore, a predictor to the likelihood of intervention completion, as well as of improvements in children’s behavior.

Although all studies reviewed have several strengths, each also contains limitations, described by the authors: Porter and Howe (2008) listed their small and non-diversified sample, lack of scoring methods as well as methodology for analyzing the ACT Evaluation Survey, a similar limitation described by Knox et al. (2013), and Pedro et al. (2017), mentioning the instrument’s lack of psychometric data. Knox et al. (2010) identified that the study did not employ well-established standardized measures, the “hitting with an object” behavior was not operationally defined, and that a dubious scale was used for determining the frequency with which physical child abuse occurred; although Altafim et al. (2016) made use of a second informant report as a measure of the child’s behavior, the authors state that since the instrument is delivered to the caregiver by the participating mother it is impossible to ensure that it had been filled out exclusively by the informant. Additionally, the authors also pointed to the fact that the study was performed exclusively with mothers as a constraint, limitation also shared in the Pedro et al. (2017) study. The latter authors also identified their failure to include families from extreme ends of the socioeconomic pyramid as a limiting factor in their study, and criticized the Brazilian instrument on classification of socioeconomic status for being predominantly based on the individual’s purchasing power of consumer goods and not income; Weymouth and Howe (2011) argued that the program might not be appropriate for the incarcerated public; Portwood et al. (2011) stressed that the large proportion of Hispanics in the sample may have limited the generalization of the results - characteristic which can also be interpreted as one of the study’s strengths as it demonstrates that the program is also effective with Hispanics; Knox et al. (2011) believed that participants may have been exposed to various components of the program before the intervention and also stressed that the established psychometric properties of the SDQ may not be applicable for the age range of the children in the study (1–10 years); Burkhart et al. (2013) stated as limitations the fact that the instrument developed (Early Childhood Bullying Questionnaire) lacked psychometric validation or comparison with other studies and that reports of parental depression and hostility were only evaluated in the pre-test measure; Knox and Burkhart (2014) pointed out that they did not collect detailed information on reasons for participants quitting the intervention.

By analyzing the presented studies, the following limitations may be grouped as commonalities: absence of control group for comparison (Altafim et al. 2016; Knox and Burkhart 2014; Pedro et al. 2017; Porter and Howe 2008; Weymouth and Howe 2011); non-randomized distribution of groups (Knox et al. 2010, 2011; Burkhart et al. 2013); absence of follow-up measures (Altafim et al. 2016; Burkhart et al. 2013; Knox and Burkhart 2014; Knox et al. 2010, 2011, 2013; Pedro et al. 2017; Weymouth and Howe 2011); and research based exclusively on data resulting from self-reports or third-party reports without observational measures as means of assessing participants’ behavior change (Altafim et al. 2016; Burkhart et al. 2013; Knox and Burkhart 2014; Knox et al. 2010, 2011, 2013; Pedro et al. 2017; Porter and Howe 2008; Weymouth and Howe 2011).

As most relevant suggestions with future research initiatives in mind, Knox and Burkhart (2014), Porter and Howe (2008) and Knox et al. (2010, 2011) mentioned the need for long-term studies (six month to one year-long follow-ups) or longitudinal studies for evaluating the delayed effects posed by the intervention; Knox et al. (2010) also called for a cost-benefit analysis so that the ACT may be compared with other modalities of child abuse prevention such as home visitation; Weymouth and Howe (2011) suggested that illustrations and drawings could be incorporated into the program to reach participants with low educational levels; Burkhart et al. (2013) proposed the use of in vivo role-playing during sessions so that mothers could practice the learning skills with their children; Altafim et al. (2016), proposed that missed sessions could be rescheduled as possible strategy to increase participants’ retention, and further studies comparing different group configurations (groups composed exclusively by fathers, groups of mothers, as well as mixed groups) to ascertain whether gender would influence the results; along the same lines, Pedro et al. (2017) advocated for studies that assess the father’s involvement, as well as psychometric analysis of the ACT Evaluation Survey, which was later done by Altafim et al. (2018); Burkhart et al. (2013) and Knox et al. (2013) suggested the use of third-party reports deriving from significant others, teachers and/or colleagues to evaluate the reliability of evaluators; and Weymouth and Howe (2011) proposed that teacher assessments should be conducted regarding the children’s behavior and in vivo instructions should be incorporated in caregiver-child interactions.

Discussion

This article’s goal was to conduct a systematic review of the literature evaluating the ACT Program. Of the 13 empirical articles that were reviewed, only three are experimental (Knox et al. 2013; Portwood et al. 2011; Thomas et al. 2009) and evaluated the efficacy of the program: two of them (Portwood et al. 2011; Thomas et al. 2009) in a full-fledged manner, with the randomization of groups (RCT) and the employment of pre-test, post-test, and follow-up measures, one of such articles (Portwood et al. 2011) evaluating the ACT training program for parents or caregivers and the second (Thomas et al. 2009) evaluating the ACT training workshop for professionals; and the third article (a) also made use of randomized control and experimental groups (RCT) to evaluate parent training, but did not include a follow-up measure. Therefore, only 23% of the empirical evaluation studies of the program presented RCT, calling for more similar studies to attest to the efficacy of the ACT program.

Regarding the evaluation measures employed in the studies, an evolving trend can be observed within the ACT Evaluation Survey, measure developed by the APA with the assistance of the ACT psychologists/coordinators (Silva, 2009). The instrument emerged for the first time in the work of Miguel and Howe (2006) as APA Self-Assessment, and was administered along with the ACT Evaluation Scenarios, developed by the authors to evaluate the ACT training workshop for professionals. Porter and Howe (2008) introduced a “media literacy” variable into the instrument and named it ACT Evaluation Survey, which was also employed in studies conducted by Knox et al. (2010), and Burkhart et al. (2013). Thomas et al. (2009) introduced the ACT Evaluation Scenarios in multiple-choice format and called it the ACT Evaluation Questionnaire. Knox et al. (2013) created their own instrument called the ACT Parenting Behaviors Questionnaire. Lastly, the version of the ACT Evaluation Survey that was used in the studies of Weymouth and Howe (2011), Altafim et al. (2016), and Pedro et al. (2017) is the version currently included in the ACT Evaluation Guide. The internal consistency obtained in the abridged version of the instrument in the study conducted by Knox et al. (2010) was 0.73. Weymouth and Howe (2011), Altafim et al. (2016) and Pedro et al. (2017) calculated the internal consistencies of each subscale of the last published version of the instrument in their studies. The internal consistencies ranged from 0.65 to 0.86; in the Brazilian studies the highest value was obtained in the parenting styles subscale (Altafim et al. al. 2016; Pedro et al. 2017), and in the American study it was in the electronic media subscale. The current ACT Evaluation Survey had its psychometric properties recently evaluated by Altafim et al. (2018) through data originating from a Brazilian study, proving to be a fast and internally consistent method for evaluating parenting programs.

Although the pioneering study assessing the ACT program for parents (Porter and Howe 2008) used a standardized instrument in addition to the ACT Evaluation Survey to evaluate program effectiveness, only Portwood et al. (2011) resumed the use of other standardized instruments. Since then, all of the subsequent studies (Altafim et al. 2016; Burkhart et al. 2013; Knox and Burkhart 2014; Knox et al. 2011, 2013; Pedro et al. 2017), made use of well-established instruments to evaluate the achievement of their objectives, and not necessarily those present in the ACT Evaluation Guide, showing adequate concern to evaluate the program in multiple ways to more reliably prove its efficacy/effectiveness. It is also important to consider that Altafim et al. (2016) and Pedro et al. (2017) studies were the only empirical studies published in a middle-income country (Brazil) evaluating the ACT program. The need to culturally diversify the target population had previously been pointed out by Altafim and Linhares (2016) as all other publications derived from the United States. The studies conducted by Altafim et al. (2016) and Pedro et al. (2017) were also the first studies evaluating the ACT Program to use multiple informants’ measures, as other caregivers identified by participating mothers also responded to instruments regarding the child’s behavior prior and after the intervention.

Considering the positive outcomes of the interventions, the significant increase obtained in the scores of some studies during follow-up (Miguel and Howe 2006; Porter and Howe 2008; Thomas et al. 2009) is also worth discussing. It would be unfounded to speculate that such positive change resulted from the intervention as other external variables could theoretically have influenced participants’ performance. However, Porter and Howe’s (2008) argument that the positive follow-up results may indicate that some of the program’s effects took longer to be noticed by participants, which is questionable. More studies are necessary to answer this question.

Concerning participants’ retention rates, although individual studies reviewed found it to be relatively low (53-86%), they are still within the boundaries of the reported parent training retention rates (52-92%) found in literature (Assemany and McIntosh 2002). The study conducted by Knox et al. (2013) ranking eighth in retention rate, considers it to be similar (percentage-wise) to studies conducted in other non-familiar settings, however the results were opposed to the authors’ initial hypothesis that a larger number of participants would adhere to the intervention since the data collection took place in a familiar setting (Community Health Center).

Among the analyzed studies, the first publication evaluating the ACT intervention program for parents (Porter and Howe 2008), and considered an important initiative for the development of subsequent studies, was also the one with the smallest sample (N = 18), but the third higher retention rate at post-test (78%). The authors attribute the high attendance in the study to multiagency collaboration, community involvement, a warm and supportive environment, easy access to the intervention venue, as well as free dinner and childcare provided to the families. It is interesting to note that the study that obtained the highest retention rate (Portwood et al. 2011) is also among the few that did not work with at-risk populations, which is the case of only four out of the 10 reviewed studies. This suggests that to achieve the retention of at-risk populations, strategies such as the ones employed by Porter and Howe (2008), for increasing retention are fundamentally important, along with the distribution of gifts, snacks, bus passes and certificates, as used in Burkhart et al. (2013), Knox et al. (2011) and Altafim et al. (2016). Regarding retention within vulnerable populations, Visovsky and Morrison-Beedy (2012) suggest that the professionals should have special training including cultural singularities concerning local population and the recruiters should be cultural peers to improve the attendance in minority groups.

Altafim et al. (2018) defend the relevance of administering the ACT Program to low-income populations, since a lower socioeconomic level is associated with greater risks for behavior problem in children, as well as negative parental practices. However, insufficient schooling is a barrier to participant retention in the intervention (Webster-Stratton 1998), and is a difficulty that was also described by Silva and Williams (2016) in their case study resulting from the failed attempt to implement a group program in a very impoverished neighborhood in Brazil. On the other hand, the study conducted by Pedro et al. (2017) demonstrates that the application of the ACT Program in low-income families is possible, and that the intervention was equally effective for all groups, regardless of socioeconomic class. The effectiveness of the program demonstrated in both high and middle-income countries and communities, with few or abundant resources, is discussed by Howe et al. (2017) and considered to be one of the highlights of the ACT Program.

Weymouth and Howe’s (2011) study had the largest sample (65 groups of parents distributed throughout 8 US cities), but it also had the second lowest retention rate out of the studies that were analyzed, with a dropout rate of nearly half of initial sample. The authors identified the at-risk profile of participants, involving parents undergoing incarceration and drug treatment as one of the possible explanations for the low retention rates. Weymouth and Howe’s (2011) also argue that the participants’ profile was atypical in universal prevention programs due to lack of contact with their children; low educational level; lack of institutional support and family communication; the transient nature of prison life; presence of mental illness and post-prison instability, all factors that may have contributed to the fact that the highest dropout rates and the lowest rates of progress were found among incarcerated participants (52%). Weymouth and Howe (2011) also observed that highly educated parents (college or graduate school), Spanish-speaking, over 56 years of age, non-European Americans and females presented a lower dropout rate. It is well known that low educational level is one of the most significant predictors of withdrawal from participation in parent programs (Reyno and McGrath 2006), corroborating the results of such study. However, personal and cultural characteristics of the Spanish-speaking group’s facilitators, such as sympathy, attentiveness, and persistence may have positively influenced the study’s results. Gross et al. (2001) state that professionals’ positive personal characteristics encourage participation in the programs. Such individual differences between facilitators represent a variable that up until then was not controlled in studies analyzing the application of ACT and this points in the direction of new research possibilities for future studies.

On the other hand, the study that had the second largest sample (Portwood et al. 2011) was also the one that obtained the highest retention among the studies evaluating the ACT program. Although not listed by these authors, one factor that could have possibly contributed in increasing participant’s retention to the program was the institutional support that was received: an employee who was part of the research team acting as ACT coordinator was inserted in each of the social services agencies. For this to happen, only agencies having successfully implemented the ACT Program could participate. Another important factor was that participants in the control group continued to receive community support services on a regular basis, thus, their link to the institution was permanent.

Although the study by Altafim et al. (2016) is the one with the lowest retention rates, it is the only study found that mentions that participants did not receive any type of financial incentive for participating in the intervention. This occurred due to Brazilian research ethics regulations prohibiting such conduct. The authors also identified difficulties in scheduling sessions as a contributing factor that decreased retention rate: sessions could not be scheduled at night or on weekends as they had to be held during school hours or while health centers were available.

Important aspects of some of the studies which favored participants retention or contributed to the validity of the research must be highlighted in order to prompt the replication of such aspects in future studies. In the studies conducted by Burkhart et al. (2013), Knox and Burkhart (2014), Knox et al. (2010, 2011, 2013), Portwood et al. (2011) and Weymouth and Howe (2011), participants were recruited from multiple settings, which enhanced the generalizability of the results across different populations. Portwood et al. (2011) also conducted a focus group in each agency location with subsets of parents who had completed the program to obtain more information on its implementation details and effectiveness to further improve it. Knox et al. (2011) made use of a treatment-as-usual (TAU) comparison group, where participants were involved in some form of treatment or family services, such as mental health or educational treatment, center-based child care, financial education, early childhood assessment or mental health agency, which, according to the authors, made it possible to reach more realistic conclusions concerning the study’s results and to compare the outcomes from the ACT Program to the ones obtained from existing services. Altafim et al. (2016) and Pedro et al. (2017) obtained data from a second informant regarding children’s behavior, strategy that had been suggested in other ACT studies (Knox et al. 2013; Silva and Williams 2015). Thus, to maximize retention it is important that such strategies should be employed and that institutional support is available so that moderate levels of retention are achieved, which in turn will contribute to obtaining large samples that increase the validity of studies, as was the case of the study conducted by Portwood et al. (2011).

Regarding the main shortcomings identified, 7 of the 10 articles evaluating the ACT intervention (Altafim et al. 2016; Burkhart et al. 2013; Knox et al. 2010, 2011, 2013; Porter and Howe 2008; Weymouth and Howe 2011), and 2 of the 3 articles evaluating the training workshop for professionals (Guttman et al. 2006; Miguel and Howe 2006), identified the attainment of data exclusively through participant’s self-reports as one of the limiting factors, and recommended the introduction of observational measures that attest to behavioral changes of caregivers/professionals, and children in their interactions to compare self-reports to the behaviors observed. Therefore, suggestions for future studies include research initiatives that involve observation measures regarding parent-child interaction as well as those that make use of third-party reports, which are to be compared with self-report measures (Marvin et al. 2002; Santini and Williams 2017; Woodhouse et al. 2015). It is also recommended that a six-month long (or longer) follow-up be carried out to evaluate the long-term effects of the program; multi-site studies in order to favor the generalization of results; that a larger number of experimental studies with RCT and follow-ups be carried out to increase the control and generalization of results, aiding in the evaluation of the program’s efficacy. It is also recommended that studies investigate the relationship between the age of the caregivers, completion of the program, and improvement in children’s behavior.

Methodological Limitations

The current systematic review accounts only for the qualitative analyses of the ACT Program evaluation studies published, allowing for comparisons of the research objectives, participants, designs, methodologies and findings published until October 2018, in order to enlighten future researchers about the interventions and research procedures that may foster retention and obtention of more significative samples sizes and results while evaluating the evidence-based status of the program. The effect sizes and statistical significance of the interventions were not given or compared, which would cause a meta-analysis to be inappropriate. Grey literature and publications from November 2018 on are not considered within this review.

Recommendations for Future Research

The current state of the art of the ACT Program is promising, and its effectiveness is attested by favorable results associated with the prevention of violence for American parents (including Hispanic parents), and Brazilian mothers alike. However, further experimental studies attesting its efficacy are necessary. This conclusion of the present review supports the classification of the ACT Program as “Promising Research Evidence” by the California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare in December 2017 (https://www.cebc4cw.org/program/act-raising-safe-kids/, retrieved on April, 03, 2019).

Future systematic reviews regarding the ACT Program evaluation should consider effect sizes and statistical power of the interventions in order to better evaluate the evidence level of the program. Hopefully, the shortcomings and improvement recommendations listed in this review may promote the advancement of research initiatives evaluating the program and serve as subsidy for the development of new research that may contribute to the consolidation of the ACT Program as an evidence-based intervention model for universal prevention of violence perpetrated against children.

References

Altafim, E. R. P., & Linhares, M. B. M. (2016). Universal violence and child maltreatment prevention programs for parents: a systematic review. Psychosocial Intervention, 25(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psi.2015.10.003.

Altafim, E. R. P., McCoy, D. C., & Linhares, M. B. M. (2018). Relations between parenting practices, socioeconomic status, and child behavior in Brazil. Children and Youth Services Review, 89, 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.04.025.

Altafim, E. R. P., Pedro, M. E. A., & Linhares, M. B. M. (2016). Effectiveness of ACT raising safe kids parenting program in a developing country. Children and Youth Services Review, 70, 315–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.09.038.

Assemany, A. E., & McIntosh, D. E. (2002). Negative treatment outcomes of behavioral parent training programs. Psychology in the Schools, 39(2), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10032.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. New York: General Learning Press.

Barnett, D. (1997). The effects of early intervention on maltreating parents and their children. In M. J. Guralnick, The effectiveness of early intervention (pp. 147–170). Baltimore, MD: Paul Brookes.

Berlin, L. J., Appleyard, K., & Dodge, K. A. (2011). Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Development, 82(1), 162–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547.x.

Burkhart, K., Knox, M., & Brockmyer, J. (2013). Pilot evaluation of the impact of the ACT Raising Safe Kids Program on children’s bullying and oppositional behavior. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(7), 942–951. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9656-3.

Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental design for research on teaching. In N. L. Gage (Ed.). Handbook of research on teaching. (pp. 6–12). Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Cozby, P. C. (2008). Methods in behavioral research (10th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Finkelhor, D. (2011). Prevalence of child victimization, abuse, crime, and violence exposure. In J. W. White, M. P. Koss, & A. E. Kazdin (Eds). Violence against women and children—mapping the terrain (pp. 9–29). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R. K., & Turner, H. A. (2007). Poly-victimization: a neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(1), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008.

Gershoff, E. T. (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and the associated child behaviors and experiences: a meta-analytic and theoretical review. American Psychological Association, 128, 539–579. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.128.4.539.

Gross, D., Julion, W., & Fogg, L. (2001). What motivates participation and dropout among low-income urban families of color in a prevention intervention? Family Relations, 50(3), 246–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2001.00246.x.

Guttman, M., Mowder, B. A., & Yasik, A. E. (2006). The ACT against violence training program: a preliminary investigation of knowledge gained by early childhood professionals. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 37(6), 717–723. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.37.6.717.

Howe, T. R., Knox, M., Altafim, E. R. P., Linhares, M. B. M., Nishizawa, N., Fu, T. J., Camargo, A. P. L., Ormeno, G. I. R., Marques, T., Barrios, L., & Pereira, A. I. (2017). International child abuse prevention: insights from ACT Raising Safe Kids. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 22(4), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12238.

Knox, M., & Burkhart, K. (2014). A multi-site study of the ACT Raising Safe Kids program: predictors of outcomes and attrition. Children and Youth Services Review, 39, 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.01.006.

Knox, M., Burkhart, K., & Cromly, A. (2013). Supporting positive parenting in community health centers: The ACT Raising Safe Kids program. Journal of Community Psychology, 41(4), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21543.

Knox, M., Burkhart, K., & Howe, T. (2011). Effects of the ACT Raising Safe Kids parenting program on children’s externalizing problems. Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies—Family Relations, 60(4), 491–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00662.x.

Knox, M., Burkhart, K., & Hunter, K. (2010). ACT against violence Parents Raising Safe Kids program: effects on maltreatment-related parenting behaviors and beliefs. Journal of Family Issues, 32(1), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X10370112.

Marin, A. H., Martins, G. D. F., Freitas, A., P. C. O., Silva, I. M., Lopes, R. C. S. L., & Piccinini, C. A. (2013). Transmissão intergeracional de práticas educativas parentais: Evidências empíricas. [Intergenerational transmission of parenting practices: Empirical evidence]. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 29(2), 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-37722013000200001.

Marvin, R., Cooper, G., Hoffman, K., & Powell, B. (2002). The Circle of Security project: attachment-based intervention with caregiver-pre-school child dyads. Attachment & Human Development, 4(1), 107–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730252982491.

Meltzoff, J. (1997). Critical thinking about research: psychology and related Fields. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Miguel, J. J., & Howe, T. R. (2006). Implementing and evaluating a national early violence prevention program at the local level: lessons from ACT (Adults and Children Together) against violence. Journal of Early Childhood and Infant Psychology, 2, 17–38.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G., the PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLOS Medicine, 6(7), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

O’Connell, M. E., Boat, T. F., & Warner, K. E. (Eds.) (2009). Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: progress and possibilities. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Pedro, M. E. A., Altafim, E. R. P., & Linhares, M. B. M. (2017). ACT Raising Safe Kids Program to promote positive maternal parenting practices in different socioeconomic contexts. Psychosocial Intervention, 26, 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psi.2016.10.003.

Pinheiro, F. M. F., & Williams, L. C. A. (2009). Violência intrafamiliar e intimidação entre colegas no ensino fundamental [Family violence and bullying on primary school]. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 39(138), 995–1018. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-15742009000300015.

Porter, B. E., & Howe, T. R. (2008). Pilot evaluation of the ACT Parents Raising Safe Kids violence prevention program. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 1, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361520802279158.

Portwood, S. G., Lambert, R. G., Abrams, L. P., & Nelson, E. B. (2011). An evaluation of the Adults and Children Together (ACT) against violence Parents Raising Safe Kids Program. Journal of Primary Prevention, 32(3-4), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-011-02495.

Reyno, S. M., & McGrath, P. J. (2006). Predictors of parent training efficacy for child externalizing behavior problems—a meta-analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 47(1), 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01544.x.

Sanders, M., Kirby, J., Tellegen, C., & Day, J. (2014). The Triple P—Positive Parenting Program: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a multi-level system of parenting support. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(4), 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.04.003.

Santini, P. M., & Williams, L. C. A. (2017). A randomized controlled trial of an intervention program to Brazilian mothers who use corporal punishment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 71, 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.04.019.

Silva, J. (2009). Parents Raising Safe Kids: ACT 8-Week Program for Parents. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Silva, J., & Randall, A. (2005). Giving psychology away: educating adults to ACT against early childhood violence. Journal of Early Childhood and Infant Psychology, 1, 37–44.

Silva, J. A., & Williams, L. C. A. (2016). A case-study with the ACT Raising Safe Kids program. Trends in Psychology, 24(2), 757–769. https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2016.2-19En.

Silva, J. A., & Williams, L. C. A. (2015). O Programa ACT para educar crianças em ambientes seguros: Da elaboração à avaliação.[The ACT Raising Safe Kids Program: From its creation to evaluation]. In: S. G. Murta, C. Leandro-França, K. B. Santos, & L. Polejack. (Org.). Prevenção e Promoção em Saúde Mental: Fundamentos, Planejamento e Estratégias de Intervenção (pp. 489–507). Novo Hamburgo, RS: Sinopsys.

Thomas, V., Kafescioglu, N., & Love, D. P. (2009). Evaluation of the Adults and Children Together (ACT) against violence training program with child care providers. Journal of Early Childhood and Infant Psychology, 5, 141–156.

Thornton, T. N., Craft, C. A., Dahlberg, L. L., Lynch, B. S., & Baer, K. (2002). Best practices of youth violence prevention: a sourcebook for community action. Atlanta, GA: Division of Violence Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). (2017). A familiar face: violence in the lives of children and adolescents. New York: UNICEF.

Visovsky, C., & Morrison-Beedy, D. (2012). Participant recruitment and retention. In B. M. Melnyk, & D. Morrison-Beedy (Eds). Intervention research: designing, conducting, analyzing, and funding (pp. 193–212). New York: Springer Publishing.

Webster-Stratton, C. (1998). Parent training with low-income families. In J. Lutzker (Ed.), Handbook of child abuse research and treatment (pp. 183–210). New York: Plenum.

Weymouth, L. A., & Howe, T. R. (2011). A multi-site evaluation of Parents Raising Safe Kids violence prevention program. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 1960–1967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011/05.022.

Wolfe, D. A., & Jaffe, P. G. (1999). Emerging strategies in the prevention of domestic violence. Futures of Children, 9(3), 133–144.

Woodhouse, S. S., Lauer, M., Beeney, J. R. S., & Cassidy, J. (2015). Psychotherapy process and relationship in the context of a brief attachment-based mother-infant intervention. Psychotherapy, 52(1), 145–150. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037335.

World Health Organization. (2018). INSPIRE handbook: action for implementing the seven strategies for ending violence against children. Geneva: WHO.

Acknowledgements

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001 and by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), Brazil [Grant #2013/05007-3].

Author Contributions

L.B.P. and L.C.A.W.: conceptualized the review. L.B.P. conducted the review steps and wrote the paper. A.C.S.: assisted with the data analyses. L.C.A.W.: collaborated with the discussion and writing of the paper. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pontes, L.B., Siqueira, A.C. & Williams, L.C.d.A. A Systematic Literature Review of the ACT Raising Safe Kids Parenting Program. J Child Fam Stud 28, 3231–3244 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01521-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01521-6