Abstract

Bullying is a serious public health issue among children and adolescents in the United States. Existing national data sources provide limited current information about involvement in bullying among youth. The purpose of this study was to estimate the prevalence of parent-reported bullying victimization and perpetration among U.S. children and adolescents ages 6–17 years using nationally representative data, and to examine health-related factors associated with bullying experiences. We conducted secondary data analysis of the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health, and stratified the sample by age (6–11 years, 12–17 years). We performed bivariate analyses to examine prevalence of bullying experiences according to demographic characteristics, health conditions, health behaviors, health services, and family environment. Using multivariable logistic regressions, we assessed the association between these factors and bullying experiences. Results showed that 22.7% of U.S. children and adolescents were bullied by others and 6.4% bullied others. The rate of bullying victimization was slightly higher among 6–11 year olds than among 12–17 year olds (24.1 vs. 21.1%, p = 0.011). The rate of bullying perpetration was 7.2% among children and 5.6% among adolescents but the difference between age groups was not statistically significant (p = 0.086). Several health conditions and health services factors were associated with either bullying victimization or perpetration, including special health care needs, internalizing problems, behavior or conduct problems, speech or other language disorders, autism, and unmet need for mental health treatment or counseling. Bullying victimization was also strongly associated with bullying perpetration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bullying is widely recognized as a serious public health issue among children and adolescents in the United States and worldwide (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [National Academies] 2016; U.N. General Assembly 2016; U.N. Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Violence against Children 2016). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines bullying as “unwanted aggressive behavior(s) by another youth or group of youths… that involves an observed or perceived power imbalance and is repeated multiple times or is highly likely to be repeated” (Gladden et al. 2014, p. 7). It may involve direct or indirect behaviors, and may assume different forms, including verbal, physical, and relational bullying (Gladden et al. 2014).

Several nationally representative self-report surveys provide insight into the prevalence and frequency with which children and adolescents in the U.S. are involved in bullying, although the focus has primarily been on adolescents. These include: (1) The School Crime Supplement (SCS) to the National Crime Victimization Survey, which is funded by the U.S. Department of Education (Musu-Gillette et al. 2017); (2) the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), funded by the CDC (Kann et al. 2016); (3) the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence (NatSCEV), funded by the U.S. Department of Justice and the CDC (Finkelhor et al. 2015); and (4) the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children survey (HBSC), funded by the World Health Organization, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau (HRSA MCHB) (Iannotti 2013). Estimates reported from these surveys vary due to different age groups sampled, sample sizes, and time intervals of administration.

The SCS (12–18 year-olds) and YRBS (14–18 year-olds), which provide the most current data on adolescents, suggest that approximately 20% have been bullied at school during the prior year (Kann et al. 2016; Musu-Gillette et al. 2017). The NatSCEV provides estimates of victimization for wider age ranges (0–17 year olds), although the survey questions focus on assault and relational aggression, which do not necessarily correspond with common definitions of bullying (Finkelhor et al.; Gladden et al. 2014). As of 2014, 16% of 0–17 year olds had experienced assault by a non-sibling peer, 13% had experienced physical intimidation, and 36% had experienced relational aggression in the previous year (Finkelhor et al.). Neither the SCS, the YRBS, nor the NatSCEV provide estimates of bullying perpetration. The HBSC survey found that during the 2009–2010 school year, 28% of youth 10–16 years had bullied another student at school at least once in the prior couple of months, and 8% had bullied others 2–3 times a month or more (Iannotti 2013). This survey also found that 28% of youth had been bullied at school at least once in the previous couple of months, and 12% of youth had been bullied 2–3 times a month or more during this time frame (Iannotti 2013).

Experiences with bullying vary significantly according to age. In a 2014 survey of students in grades 3–12, rates of being bullied were highest among 3rd graders (age 9) and decreased steadily through elementary, middle, and high school grades (Luxenberg et al. 2015). Decreases in bullying victimization with age were also observed among adolescents in the SCS (Musu-Gillette et al. 2017) and the YRBS (Kann et al. 2016), where the percentage of students bullied on school property decreased from 23% among 9th graders to 16% among 12th graders. Somewhat different age patterns are observed for bullying others. In a meta-analysis, rates of bullying others decreased between childhood (3–11 years) and adolescence (12–18 years), while the likelihood of being bullied and also bullying others (frequently referred to as bully-victims in the research literature) peaked in early adolescence (12–14 years), although age was a weak predictor for both outcomes (Cook et al. 2010).

Involvement in bullying has been found to be associated with a variety of physical and mental health problems. A robust literature indicates that youth who have been bullied are at increased risk of internalizing problems such as depression and anxiety (Cook et al. 2010; Copeland et al. 2013; Reijntjes et al. 2010), self-harm behaviors (Lereya et al. 2015), suicidal thoughts and behavior (Espelage and Holt 2013; Kowalski and Limber 2013; van Geel et al. 2014), psychotic symptoms (Cunningham et al. 2016), and somatic symptoms (Fekkes et al. 2006; Gini and Pozzoli 2013; Herge et al. 2016). Although considerably less research has focused on physical and mental health problems associated with bullying others (National Academies 2016), studies suggest that youth who bully others are at increased risk of psychosomatic problems (Gini and Pozzoli 2009) and psychotic experiences (Wolke et al. 2014). Children and adolescents involved in bullying are also at risk for externalizing problems, although the effect size for bullied youth is much smaller than that for bully-victims or for youth who bully others (Cook et al. 2010). There are limited studies examining links between health services and bullying experiences, however, referral to psychosocial services has been associated with both being bullied and bullying others (Sourander et al. 2000).

A large literature has also examined individual, peer, family, school-, and community-level factors that affect the likelihood that a youth is involved in bullying (National Academies 2016). Risk factors for being bullied include the presence of certain health conditions and health behaviors. With respect to health conditions, youth with disabilities are at heightened risk of bullying, compared with their non-disabled peers (Christensen et al. 2012; Rose et al. 2011a, b), but rates of bullying vary significantly by type of disability. For example, youth with autism spectrum disorder are more likely to be bullied than youth with intellectual disabilities or typically developing youth (Zeedyk et al. 2014). Those with emotional disturbance or other health impairments experience higher rates of bullying than youth with other types of disabilities (Blake et al. 2016), and those with noticeable disabilities such as physical handicaps tend to be bullied more frequently than those with less obvious disabilities (Dawkins 1996; Swearer et al. 2012). The extent to which youth with disabilities are involved in bullying others also appears to be related to the nature of the disability. For example, youth with emotional, behavioral, and developmental disabilities are more likely to bully others than their peers without disabilities, but not youth with physical disabilities (van Cleave and Davis (2005).

Health-related behaviors may also increase the likelihood of bullying involvement. For example, several aspects of technology use have been found to be consistently associated with higher rates of involvement in bullying (Guo 2016). Electronic aggression, also known as cyberbullying, is bullying that “occurs through e-mail, a chat room, instant messaging, a website (including blogs), text messaging, or videos or pictures posted on websites or sent through cell phones” (David-Ferdon and Hertz 2009, p. 3). Youth who are involved in cyberbullying (as victims, perpetrators, or both) spend more time online, report more online game use, engage in more risky use of technology, and report exposure to more media violence compared to their peers who are not involved in cyberbullying (Baldry et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2017; Chang et al. 2015).

Aspects of the family environment may significantly influence the likelihood that youth are involved in bullying. Low parental warmth and involvement, parental hostility, inconsistent discipline, physical punishment by parents, and lack of parental supervision are related to higher rates of bullying among children and adolescents (Burkhart et al. 2013; Cook et al. 2010; Olweus 1993). In addition, youth who live with both parents are less likely to be bullied than youth living in other family arrangements (Garmy et al. 2017; Kim et al. 2004), bully others (Kim et al. 2004), or both (Kim et al. 2004). Adolescents from “non-intact” families bully others more often than those from two-parent families, but involvement in bullying is attenuated when the mother and father are involved in their lives (Flouri and Buchanan 2003). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which include stressful or traumatic events, abuse, neglect, household dysfunction, and witnessing domestic conflict and violence, also increase the likelihood of involvement in bullying (Baldry 2003; Cook et al.; Espelage and Swearer 2010; Forster et al. 2017).

Despite ample previous studies examining risk factors for bullying involvement among youth, these studies have primarily been smaller-scale clinical or developmental studies with limited sample sizes and geography or have been based on national data limited by age group, focusing almost exclusively on adolescents. Comprehensive analyses are needed using national samples comprised of both children and adolescents and examining a broad array of child- and family-level characteristics associated with bullying experiences. For this study, we sought to build on this body of literature by examining recent national data on both bullying victimization and perpetration, for a wide age range of youth, including younger ages. Specifically, the goals were to: (1) estimate the prevalence of bullying victimization and perpetration among children and adolescents ages 6–17, using nationally representative data from parents; (2) determine whether the prevalence of victimization and perpetration differs between children (6–11 years) and adolescents (12–17 years); and (3) examine associations between bullying involvement and demographic factors, health conditions, health behaviors, health services factors, and aspects of the family environment (particularly family structure and functioning). Based on previous findings that parents typically report lower levels of youths’ exposure to violence and bullying than youth themselves (Goodman et al. 2010), we hypothesized that the rate of bullying victimization would be lower than that reported by other national youth self-report surveys, due to the parent-reported nature of the data. We further anticipated that the prevalence of bullying involvement would be higher among 6–11 year olds than among 12–17 year olds, partly because this would be consistent with age-related differences established in previous work on bullying experiences and partly because parents are less likely to be familiar with their child’s daily experiences as the child grows older and more independent.

Method

Data Source

The 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) is a cross-sectional survey of non-institutionalized children and adolescents ages 0 through 17 years living in the 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. The survey provides state-level and nationally representative estimates of key indicators of child health and well-being, including measures of physical, emotional, and behavioral health; presence and impact of special health care needs; healthcare access, utilization, and quality; and family and community factors that affect health. With funding and direction from HRSA MCHB, the U.S. Census Bureau conducted the 2016 NSCH using a two-phased data collection approach. First, an initial household screener assessed the presence, basic demographic characteristics, and special health care need status of all children in the home. Then one of three detailed age-specific topical questionnaires was completed for a randomly selected child or adolescent. Questionnaires included slightly different topics and questions depending on age categories (0–5 years, 6–11 years, 12–17 years). Respondents were parents or other caregivers familiar with the child’s health and health care needs. Children with special health care needs and children 0 to 5 years old were oversampled in homes with multiple children. Data collection occurred from June 2016 to February 2017. A letter was sent to randomly selected households with an invitation to participate in the survey via the web; non-responders received multiple mailings, including a paper instrument to complete and return by mail. The survey was available in English and Spanish, and a Telephone Questionnaire Assistance line was available to assist respondents in completing the survey.

The total sample for the 2016 NSCH was 50,212 children and adolescents. The overall weighted response rate was 40.7%. The screener completion rate (estimated proportion of occupied households that completed a screener) was 53.0% and the interview completion rate (proportion of households with children or adolescents who completed the detailed topical questionnaire) was 69.7%. Sampling weights were adjusted to account for nonresponse and to reduce the magnitude of bias. Post-stratification adjustment was conducted to ensure that sociodemographic subgroups were appropriately represented in the estimates. Additional information regarding the survey’s methodology and response rates are available elsewhere (Health Resources and Services Administration 2017). The current study utilized existing data that were publicly available, and therefore was exempt from Institutional Review Board review.

Measures

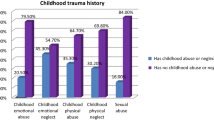

We assessed bullying victimization using the question: “How well does the following phrase describe this child? This child is bullied, picked on, or excluded by other children.” Bullying perpetration was assessed through a similar statement: “This child bullies others, picks on them, or excludes them.” Response options for both items were “Definitely true,” “Somewhat true”, and “Not true.” Both items were parent-reported, thus the measures are a reflection of parental/caregiver awareness of their child’s bullying experiences, not necessarily of the actual rates of bullying. We examined the distribution of response options and found that it was rare for parents/caregivers to endorse the “Definitely true” response option, resulting in small sample sizes that precluded the use of the original 3-point scale (see Table 1 and Fig. 1). Therefore, in the reported analyses, we combined the “Definitely true” and “Somewhat true” responses within each question and created separate dichotomous variables for bullying victimization and bullying perpetration (yes vs. no). We elected to create dichotomous measures because our primary motivation was to estimate the prevalence of bullying victimization and perpetration, rather than severity or frequency.

Selection of covariates was informed by data availability and previous literature indicating associations with bullying. Variables include demographic characteristics, current health conditions, health behaviors, health services, and family structure/functioning factors. Demographic characteristics include sex, race/ethnicity, and household federal poverty level (FPL). Current health conditions included special health care needs status, based on the Children with Special Health Care Needs Screener (Bethell et al. 2002), internalizing problems (combining anxiety and/or depression), behavioral or conduct problems, developmental delay, speech or other language disorder, learning disability, autism, and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Health behaviors included adequate sleep, time spent watching television/videos or playing video games, and time spent using recreational computers/cell phones/handheld video games. We derived adequate sleep based on the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s recommendations for sleep among pediatric populations (Paruthi et al. 2016). Given the paucity of data on the link between health services and bullying, we also examined having a usual source of care for preventive services, receipt of treatment/counseling from a mental health professional in the past year, current receipt of services under a special education or early intervention plan, and number of emergency department (ED) visits in the past year.

Family-related factors included family structure, parent/child rapport, and number of ACEs in child’s lifetime. Parent/child rapport was based on the question “How well can you and this child share ideas or talk about things that really matter?” We categorized responses into “Very well,” “Somewhat well,” and “Not very well/Not at all.” ACEs included parent/guardian death, parent/guardian time in jail, witnessing interpersonal violence, witnessing/victim of neighborhood violence, living with someone mentally ill, suicidal, or severely depressed, living with someone with alcohol/drug problem, and unfair treatment/judgment because of race/ethnicity.

Data Analyses

We estimated the prevalence of bullying victimization and perpetration among U.S. children and adolescents aged 6 through 17 years, by individual year of age and then stratified by age group (6–11 years, 12–17 years). We selected these two age strata to roughly correspond to elementary vs. middle/high school age cohorts. Although the NSCH uses three age-specific topical questionnaires to address developmentally appropriate conditions, the core content is shared across each age range, and the bullying questions are included in both the 6–11 and 12–17 year questionnaires.

We performed bivariate analyses to examine the unadjusted rates of bullying experiences within each age group by the characteristics of interest, which provide descriptive percentages of reported bullying experiences. We conducted chi-square tests of independence with design-based F statistics for all covariates, and then used multivariable logistic regression models to assess the independent relationship between the outcome variables, (a) bullying victimization and (b) bullying perpetration, and the various correlates, which provide adjusted relative prevalence rates to understand the likelihood that children with characteristics of interest will be involved in bullying relative to children in meaningful reference groups while holding other correlates constant. Separate models were conducted for children 6–11 years, and adolescents 12–17 years to account for different significant associations for each age group identified in the bivariate analyses. Estimates are reported as adjusted prevalence rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals comparing the association between each covariate and the bullying measures.

The following demographic variables were imputed for the purpose of raking during weighting procedures: sex (0.10% missing), race (0.32%), ethnicity (0.57%), and FPL (18.57%). The demographic variables were imputed using hot-deck imputation while FPL was multiply imputed using regression imputation; a multiple imputation file containing six FPL implicates was used to calculate estimates with correct standard errors. For all other variables, we dropped observations with missing or unknown data from the analyses, resulting in an overall sample of 15,010 6–11 year olds and 20,708 12–17 year olds. All analyses were weighted based on the survey’s sampling design to produce estimates that were representative of children and adolescents nationally, and were conducted using StataSE 15.

Results

Bullying Victimization

Overall, 22.7% of children and adolescents aged 6–17 years were reported to be bullied by others (range: 15.9–27.2%, Fig. 1). The highest rates occurred among middle childhood ages, however substantial bullying victimization was reported even for the youngest ages, including 17.9% of 6-year-olds. After stratifying by age group, the prevalence of bullying victimization was 24.1% among children and 21.2% among adolescents (Table 2).

Among children (6–11 years), bivariate analyses indicated that most factors were significantly associated with bullying victimization in the expected directions (Table 2). After including all covariates in the model, children from families <100% FPL had 49% increased prevalence of being bullied by others, and children from families 100–199% FPL had 28% increased prevalence, compared with children from families ≥ 400% FPL (Table 3). Children with special health care needs had 28% increased prevalence of being bullied by others, children with internalizing problems had 47% increased prevalence, children with behavioral or conduct problems had 41% increased prevalence, and children with speech or other language disorders had 65% increased prevalence, compared with children who did not have those health conditions. Children with greater than 3 h of technology usage had 37% increased prevalence of being bullied by others, compared with children with 1 h or less usage. Regarding health services factors, children who needed but did not receive any mental health treatment or counseling in the past year had 104% increased prevalence (or 2.04 times greater) of being bullied by others compared with children who did not need or receive treatment, and children with 2 or more emergency department visits in the past year had 72% increased prevalence of being bullied by others, compared with children with no visits. Compared with children from families who share ideas or talk ‘very well’, there was a 23% increased prevalence for children from families who share ideas or talk ‘somewhat well’, but no increased prevalence for children from families who share ideas or talk ‘not very well/not at all’. Compared with children with no adverse childhood experiences, those with 1 and those with 2 or more had a 41 and 46% greater prevalence, respectively, of being bullied by others.

Among adolescents (12–17 years), bivariate analyses indicated that many factors were associated with bullying victimization in the expected directions (Table 2). After adjusting for all covariates, female adolescents had 20% increased prevalence of being bullied by others compared with male adolescents (Table 3). Non-Hispanic Black adolescents had 40% decreased prevalence of being bullied by others compared with non-Hispanic White adolescents. Compared with adolescents from families ≥400% FPL, adolescents 200–399% FPL had 24% increased prevalence of being bullied by others, whereas adolescents from families in other poverty levels had similar prevalence. Similar to the results observed in children, compared with adolescents who did not have the following health conditions, adolescents with special health care needs had 38% increased prevalence of being bullied by others, adolescents with internalizing problems had 52% increased prevalence, and adolescents with behavioral or conduct problems had 69% increased prevalence. Unlike children, adolescents with autism had 56% increased prevalence of being bullied by others and adolescents with speech or other language disorders had similar prevalence of being bullied by others, compared with adolescents who did not have those conditions, respectively. Regarding health services factors, mental health treatment or counseling was associated with bullying victimization: specifically, compared with adolescents who did not need treatment, those who needed but did not receive any treatment in the past year had 67% increased prevalence and those who received treatment had 37% increased prevalence of being bullied by others. Lastly, adverse childhood experiences were the only family-related factor associated with bullying victimization. Compared with children with no adverse childhood experiences, those with 1 and those with 2 or more had 44% and 53%, respectively, increased prevalence of being bullied by others.

Bullying Perpetration

Overall, 6.4% of children and adolescents aged 6–17 years were reported to bully others (range: 4.3–8.9%, Fig. 2). Older adolescents (15–17 years) were the least likely to bully others. After stratifying by age group, the prevalence of bullying perpetration did not significantly differ between children and adolescents (p = 0.086) (Table 1). Total prevalence of bullying perpetration was 7.2% among children and 5.6% among adolescents (Table 2). The percentage of bully-victims was 5.1% among children and 4.0% among adolescents (Table 1).

Among children, all health conditions, health behavior, health services, and family factors were significantly associated with bullying perpetration in the expected directions (Table 2). After adjusting for all covariates, compared with children who did not have the following conditions, children with speech or other language disorders had 43% decreased prevalence of bullying others, children with learning disabilities had 37% decreased prevalence, and children with ADHD had 47% decreased prevalence. In contrast, children with behavioral or conduct problems had 440% increased prevalence (or 5.40 times greater) of bullying others (Table 3). Children with 2 h of TV in an average weekday had 38% decreased prevalence of bullying others compared with those with 1 h or less of TV. For bullying perpetration, the model also included bullying victimization as a covariate: children who were bullied by others had 567% increased prevalence of bullying others (or 6.67 times greater), compared with those who were not bullied. The only family factor associated with bullying perpetration was the number of adverse childhood experiences: compared with children who had no adverse experiences, those with 1 adverse childhood experience had 32% decreased prevalence of bullying others, whereas those with 2 or more adverse childhood experiences had 88% increased prevalence of bullying others.

Among adolescents, many factors were significantly associated with bullying perpetration in the expected direction (Table 2). After adjusting for all covariates, several factors were no longer associated with bullying perpetration (Table 3). Female adolescents had 35% decreased prevalence of bullying others compared with male adolescents. Compared with adolescents without the following conditions, adolescents with developmental delays had 62% decreased prevalence of bullying others and adolescents with autism had 46% decreased prevalence. Adolescents with behavioral or conduct problems had 322% increased prevalence of bullying others (or 4.22 times greater) compared with adolescents without such problems. The perpetration model included bullying victimization as a covariate: compared with adolescents who were not bullied by others, those who were bullied by others had 706% increased prevalence of bullying others (or 8.06 times greater). Compared with adolescents from families who share ideas or talk ‘very well’, those from families who share ideas or talk ‘not very well/not at all’ had 110% increased prevalence (or 2.10 times greater) of bullying others. Lastly, compared with adolescents who had no adverse childhood experiences, adolescents with 1 adverse experience had 42% decreased prevalence of bullying others; contrary to the findings among children, adolescents with 2 or more adverse experiences had similar prevalence of bullying others.

Discussion

Among U.S. children and adolescents aged 6–17 years, 22.7% were reported to be bullied by others and 6.4% were reported to bully others. The rate of bullying victimization was slightly but statistically significantly higher among 6–11 year olds (24.1%) than among 12–17 year olds (21.1%). The rate of bullying perpetration was also slightly higher among children than adolescents (7.2% vs. 5.6%) although the difference was not statistically significant. The lower rates of bullying perpetration vs. victimization may indicate that children and adolescents who bully others may be less likely to report this behavior to their parents, while children who are bullied may be more likely to report the experiences to their parents. Alternatively, the differential rates of perpetration and victimization may reflect that youth who bully others have multiple targets. The difference in rates found our study is consistent with other data from youth self-reporting on bullying in U.S. schools (Luxenberg et al. 2015).

We expected to find that parent-reported rates of bullying victimization would be lower than youth self-reported rates, based on the assumption that parents may be less familiar with their child’s daily experiences at school, especially as the child gets older. Moreover, because the wording in the NSCH questions likely reflects parents’ awareness of the extent to which their child is currently being bullied (whereas other self-report measures assess the frequency of being bullied within the past year or past school year) we anticipated lower rates to be reflected in the NSCH compared with the SCS or YRBS. However, we found that the parent-reported NSCH estimate for bullying victimization among adolescents (21.1%) was similar to the YRBS (20.2%; Kann et al. 2016) and the SCS (20.8%; Musu-Gillette et al. 2017). Current national estimates for younger children are not available, and thus our finding that 24.1% of children 6–11 years were bullied by others, with substantial early manifestation, provides an important extension to previous literature.

In adjusted analyses, several health conditions were associated with bullying victimization: in both children and adolescents, special health care needs, internalizing problems, and behavior or conduct problems were associated with higher relative prevalence of being bullied by others. Children with speech or other language disorders and adolescents with autism also had increased prevalence. These findings are consistent with previous research that found that youth with internalizing problems (Cook et al. 2010; Copeland et al. 2013) are more likely to be bullied, as are youth with a variety of special health care needs and disabilities (Blake et al. 2016; Christensen et al. 2012; Rose et al. 2011a, b), including autism (Zeedyk et al. 2014) and speech impairment (Blood et al. 2011). Children with greater recreational computer or cell phone use also had increased prevalence, consistent with previous findings that youth who are cyberbullied report more time online (Baldry et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2017; Guo 2016). In addition, in both age groups, unmet need for mental health treatment or counseling was also independently associated with bullying victimization even when other health services factors were no longer statistically significant.

Behavioral or conduct problems and bullying victimization were strongly associated with bullying perpetration. The adjusted prevalence of bullying others was five times higher among children with behavioral or conduct problems, and four times higher among adolescents. These findings are consistent with past research that has found strong associations between externalizing behavior and bullying perpetration, and weaker associations between externalizing behavior and bullying victimization (Cook et al. 2010). In addition, children who were bullied by others had over six times the prevalence of bullying others, and adolescents bullied by others had over eight times the prevalence. However, the proportion of youth who were bully-victims was small (5 and 4%, respectively), consistent with other studies that have found this is typically a small group (Yang and Salmivalli 2013).

Limitations and Future Research

There are several limitations to consider for this study. First, the cross-sectional nature of the survey does not allow for inference about causal relationships between certain health conditions, health behaviors, or health services factors and bullying behaviors. In addition, there may be some response bias especially around bullying perpetration due to the question wording. In past iterations of the NSCH, a similar question was used but it was asked in the context of “the past month”. For the 2016 NSCH, this reference to the past month was dropped, resulting in the possible perception by parents that they are making permanent character statements about their child through their responses. Parents may have been more reluctant to describe their child as a bully, as opposed to reporting bullying behavior within a limited time period. Furthermore, due to small sample sizes in “Definitely true” responses for the bullying measures, we combined these with the “Somewhat true” responses, resulting in some loss of information. We were also limited in our ability to examine bully-victims due to small sample sizes. However, new NSCH data will be available annually starting in 2017 so in the future it may be possible to combine multiple years of data to increase sample size and conduct detailed analyses on particular subgroups, including more nuanced comparisons of “Definitely true” vs. “Somewhat true” responses and investigations about bully-victims. Future studies could also explore interaction or additive terms, to examine whether the specific independent covariates included in the current study have different effects on bullying experiences when considered in combination. Finally, the NSCH did not collect information to provide additional context surrounding the bullying experiences, such as the type (e.g., physical harm, threats, name-calling/insults), location (e.g., school property, playground, cyberbullying), or frequency.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the current study has provided the first nationally representative estimates of both bullying victimization and perpetration across a wide age range of U.S. children and adolescents, based on parental reports, along with associated demographic, health condition, health behavior, health services, and family factors. Bullying experiences are common among both age groups: 1 in 4 children and 1 in 5 adolescents are bullied by others. In addition, 7% of children and 5.5% of adolescents bully others. Several health conditions and health services factors are associated with either bullying victimization or perpetration, including special health care needs, internalizing problems, behavior or conduct problems, speech or other language disorders, autism, and unmet need for mental health treatment or counseling. Bullying victimization is also strongly associated with bullying perpetration.

This study is consistent with others (National Academies 2016) in highlighting the need for universal prevention efforts and targeted services for children and adolescents to address bullying, Findings from this study suggest that such efforts should begin at young ages and address the needs of those who are at greatest risk of being bullied, including those with special health care needs, internalizing problems, behavioral and conduct problems, autism, and speech or other language disorders. Results also reveal opportunities to improve access to mental health services for youth experiencing bullying. Efforts should be made to target bullying prevention strategies where children and adolescents at higher risk are served, such as during health care visits and mental health visits. Parents, educators, speech and occupational therapists, coaches, and other adults who are in frequent contact with children and adolescents, should be offered training on bullying, who is at the greatest risk, and prevention and intervention strategies.

Data Availability Statement

All data and supporting documentation are publicly available from the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau (https://mchb.hrsa.gov/data/national-surveys).

Disclaimer

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. The current study utilized existing data that were publicly available, and therefore was exempt from Institutional Review Board review. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Health Resources and Services Administration, or the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, nor does mention of the department or agency names imply endorsement by the U.S. government.

References

Baldry, A. C. (2003). Bullying in schools and exposure to domestic violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27, 713–732.

Baldry, A. C., Farrington, D. P., & Sorrentino, A. (2015). ‘Am I at risk of cyberbullying’? A narrative review and conceptual framework for research on risk of cyberbullying and cybervictimization: The risk and needs assessment approach. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 23, 36–51.

Bethell, C. D., Read, D., Stein, R. E., Blumberg, S. J., Wells, N., & Newacheck, P. W. (2002). Identifying children with special health care needs: Development and evaluation of a short screening instrument. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 2, 38–47.

Blake, J. J., Kim, E. S., Lund, E. M., Zhou, Q., Kwok, O. M., & Benz, M. R. (2016). Predictors of bully victimization in students with disabilities: A longitudinal examination using a national data set. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 26(4), 199–208.

Blood, G. W., Blood, I. M., Tramontana, G. M., Sylvia, A. J., Boyle, M. P., & Motzko, G. R. (2011). Self-reported experience of bullying of students who stutter: Relations with life satisfaction, life orientation, and self-esteem. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 113, 353–364.

Burkhart, K. M., Knox, M., & Brockmyer, J. (2013). Pilot evaluation of the ACT raising safe kids program on children’s bullying behavior. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(7), 942–951.

Chang, F. C., Chiu, C. H., Miao, N. F., Chen, P. H., Lee, C. M., Huang, T. F., & Pan, Y. C. (2015). Online gaming and risks predict cyberbullying perpetration and victimization in adolescents. International Journal of Public Health, 60(2), 257–266.

Chen, L., Ho, S. S., & Lwin, M. O. (2017). A meta-analysis of factors predicting cyberbullying perpetration and victimization: From the social cognitive and media effects approach. New Media & Society, 19(8), 1194–1213.

Christensen, L. L., Fraynt, R. J., Neece, C. L., & Baker, B. L. (2012). Bullying adolescents with intellectual disability. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 5(1), 49–65.

Cook, C. R., Williams, K. R., Guerra, N. G., Kim, T. E., & Sadek, S. (2010). Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic investigation. School Psychology Quarterly, 25(2), 65.

Copeland, W. E., Wolke, D., Angold, A., & Costello, E. J. (2013). Adult psychiatric outcomes of bullying and being bullied by peers in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(4), 419–426.

Cunningham, T., Hoy, K., & Shannon, C. (2016). Does childhood bullying lead to the development of psychotic symptoms? A meta-analysis and review of prospective studies. Psychosis, 8(1), 48–59.

David-Ferdon, C., & Hertz, M. F. (2009). Electronic media and youth violence: A CDC issue brief for researchers.. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pdf/Electronic_Aggression_Researcher_Brief-a.pdf.

Dawkins, J. L. (1996). Bullying, physical disability and the paediatric patient. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 38(7), 603–612.

Espelage, D. L., & Holt, M. K. (2013). Suicidal ideation and school bullying experiences after controlling for depression and delinquency. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(1), S27–S31.

Espelage, D. L., & Swearer, S. M. (2010). A social-ecological model for bullying prevention and intervention: Understanding the impact of adults in the social ecology of youngsters. In S. R. Jimerson, S. M. Swearer & D. L. Espelage (Eds.), Handbook of bullying in schools: An international perspective (pp. 61–72). New York: Routledge.

Fekkes, M., Pijpers, F. I., Fredriks, A. M., Vogels, T., & Verloove-Vanhorick, S. P. (2006). Do bullied children get ill, or do ill children get bullied? A prospective cohort study on the relationship between bullying and health-related symptoms. Pediatrics, 117(5), 1568–1574.

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H. A., Shattuck, A., & Hamby, S. L. (2015). Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: Results from the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(8), 746–754.

Flouri, E., & Buchanan, A. (2003). The role of mother involvement and father involvement in adolescent bullying behavior. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18(6), 634–644.

Forster, M., Gower, A. L., McMorris, B. J., & Borowsky, I. W. (2017). Adverse Childhood Experiences and School-Based Victimization and Perpetration. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. https://doi.org/10.1177/00886260517689885.

Garmy, P., Vilhjalmsson, R., & Kristjánsdóttir, G. (2017). Bullying in school-aged children in Iceland: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn2017.05.009.

Gini, G., & Pozzoli, T. (2009). Association between bullying and psychosomatic problems: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 123(3), 1059–1065.

Gini, G., & Pozzoli, T. (2013). Bullied children and psychosomatic problems: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 132(4), 720–729.

Gladden, R. M., Vivolo-Kantor, A. M., Hamburger, M. E., & Lumpkin, C. D. (2014). Bullying surveillance among youths: Uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements, version 1.0. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Goodman, K. L., De Los Reyes, A., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2010). Understanding and using informants’ reporting discrepancies of youth victimization: A conceptual model and recommendations for research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 13(4), 366–383.

Guo, S. (2016). A meta‐analysis of the predictors of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization. Psychology in the Schools, 53(4), 432–453.

Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. (2017). 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health: Frequently Asked Questions. https://mchb.hrsa.gov/data/national-surveys/data-user.

Herge, W. M., La Greca, A. M., & Chan, S. F. (2016). Adolescent peer victimization and physical health problems. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 41(1), 15–27.

Iannotti, R. J. (2013). Health Behavior in School-Aged Children (HBSC), 2009-2010. ICPSR34792-v1. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. Available from: 10.3886/ICPSR34792.v1.

Kann, L., McManus, T., Harris, W. A., Shanklin, S. L., Flint, K. H., & Hawkins, J., et al. (2016). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance: United States, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries, 65(6), 1–174.

Kim, Y. S., Koh, Y. J., & Leventhal, B. L. (2004). Prevalence of school bullying in Korean middle school students. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 158(8), 737–741.

Kowalski, R. M., & Limber, S. P. (2013). Psychological, physical, and academic correlates of cyberbullying and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, S13–S20.

Lereya, S. T., Copeland, W. E., Costello, E. J., & Wolke, D. (2015). Adult mental health consequences of peer bullying and maltreatment in childhood: two cohorts in two countries. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(6), 524–531.

Luxenberg, H., Limber, S. P., & Olweus, D. (2015). Bullying in U.S. schools: 2014 status report. Center City, MN: Hazelden Publishing.

Musu-Gillette, L., Zhang, A., Wang, K., Zhang, J., & Oudekerk, B. A. (2017). Indicators of school crime and safety: 2016 (NCES 2017-064/NCJ 250650). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Preventing bullying through science, policy, and practice.. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what can we do. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Paruthi, S., Brooks, L. J., D’Ambrosio, C., Hall, W. A., Kotagal, S., & Lloyd, R. M., et al. (2016). Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: A consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Journal of Clinical Sleeping Medicine, 12, 785–786.

Reijntjes, A., Kamphuis, J. H., Prinzie, P., & Telch, M. J. (2010). Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(4), 244–252.

Rose, C. A., Espelage, D. L., Aragon, S. R., & Elliott, J. (2011a). Bullying and victimization among students in special education and general education curricula. Exceptionality Education International, 21(3), 2–14.

Rose, C. A., Monda-Amaya, L. E., & Espelage, D. L. (2011b). Bullying perpetration and victimization in special education: A review of the literature. Remedial and Special Education, 32(2), 114–130.

Sourander, A., Helstelä, L., Helenius, H., & Piha, J. (2000). Persistence of bullying from childhood to adolescence—A longitudinal 8-year follow-up study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24(7), 873–881.

Swearer, S. M., Wang, C., Maag, J. W., Siebecker, A. B., & Frerichs, L. J. (2012). Understanding the bullying dynamic among students in special and general education. Journal of School Psychology, 50(4), 503–520.

U.N. General Assembly (2016). Protecting children from bullying: Report of the Secretary General, A/71/213 (July26, 2016). www.undocs.org.

U.N. Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Violence against Children. (2016). Ending the torment: Tackling bullying from the schoolyard to cyberspace. New York: United Nations.

van Cleave, J., & Davis, M. M. (2005). Bullying and peer victimization among children with special health care needs. Pediatrics, 118, e1212–e1219.

van Geel, M., Vedder, P., & Tanilon, J. (2014). Relationship between peer victimization, cyberbullying, and suicide in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(5), 435–442.

Wolke, D., Lereya, S. T., Fisher, H. L., Lewis, G., & Zammit, S. (2014). Bullying in elementary school and psychotic experiences at 18 years: a longitudinal, population-based cohort study. Psychological Medicine, 44(10), 2199–2211.

Yang, A., & Salmivalli, C. (2013). Different forms of bullying and victimization: Bully-victims versus bullies and victims. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 10(6), 723–738.

Zeedyk, S. M., Rodriguez, G., Tipton, L. A., Baker, B. L., & Blacher, J. (2014). Bullying of youth with autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, or typical development: victim and parent perspectives. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(9), 1173–1183.

Author Contributions

L.L.H. designed and executed the study, conducted data analysis, and wrote the methods. L.S. collaborated with the design of the study and wrote the results. S.L. collaborated with the design of the study and wrote the introduction. B.M. collaborated with the design of the study and wrote the discussion. E.E. collaborated with the design of the study and edited the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lebrun-Harris, L.A., Sherman, L.J., Limber, S.P. et al. Bullying Victimization and Perpetration among U.S. Children and Adolescents: 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health. J Child Fam Stud 28, 2543–2557 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1170-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1170-9