Abstract

Discrepancies often occur among informants’ reports of various domains of child and family functioning and are particularly common between parent and child reports of youth violence exposure. However, recent work suggests that discrepancies between parent and child reports predict subsequent poorer child outcomes. We propose a preliminary conceptual model (Discrepancies in Victimization Implicate Developmental Effects [DiVIDE]) that considers how and why discrepancies between parents’ and youths’ ratings of child victimization may be related to poor adjustment outcomes. The model addresses how dyadic processes, such as the parent–youth relationship and youths’ information management, might contribute to discrepancies. We also consider coping processes that explain why discrepancies may predict increases in youth maladjustment. Based on this preliminary conceptual framework, we offer suggestions and future directions for researchers who encounter conflicting reports of community violence exposure and discuss why the proposed model is relevant to interventions for victimized youths.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One of the most consistent findings in the social sciences is that different informants do not agree on ratings of behavior. Poor cross-informant agreement can present a conundrum for researchers, as estimates regarding the prevalence of disorders may be quite different depending on the informant (e.g., Rubio-Stipec et al. 2003; Youngstrom et al. 2003). Models of risk and protective factors can also vary considerably depending on the informant used (Kuo et al. 2000; Offord et al. 1996), and this can have implications for the application of preventive interventions. Moreover, parent–youth discrepancies on ratings of behavior and stressful experiences may dictate what clinicians identify as problems warranting treatment (Hawley and Weisz 2003; Yeh and Weisz 2001).

One area where discrepancies are of particular concern is youths’ exposure to violence. Parents typically report lower levels of youths’ exposure to violence than do youth (e.g., Ceballo et al. 2001; Howard et al. 1999; Kuo et al. 2000; Richters and Martinez 1993). Therefore, researchers may draw very different conclusions about both risk and protective processes for violence exposure depending on the informant (Kuo et al. 2000). These discrepancies also have implications for service use initiation, treatment goal-setting, and screening prior to intervention. Indeed, violence exposure is likely an unaddressed issue for many youths enrolled in mental health treatment, although the emotional and behavioral sequelae of violence exposure may be considered the “presenting problem” (Guterman and Cameron 1999; Guterman et al. 2002).

Most critically, some researchers posit that parent–youth discrepancies on severe forms of violence exposure (e.g., violent victimization) reflect circumstances in which youths feel unsupported by caregivers and therefore may lack adequate coping resources (Ceballo et al. 2001; Richters and Martinez 1993). Under these circumstances, one might surmise that parent–youth discrepancies on violence exposure—especially severe forms of exposure, such as violent victimization—are linked to maladjustment. In fact, a growing body of evidence suggests that discrepancies in how parents and adolescents perceive the same behaviors (e.g., parenting) predict poor youth adjustment outcomes (e.g., Ferdinand et al. 2004; Pelton et al. 2001). However, in order to investigate the implications of informant discrepancies on victimization and their links to youth adjustment, it would be especially useful to have a theoretical framework to guide research.

In the current paper, we offer a preliminary model to conceptualize why informant discrepancies in reports of youth violence exposure might predict poor youth outcomes. First, we review definitional and conceptual issues that provide a foundation for our theoretical model. Second, with a focus on youth victimization, we review the research on parent–youth discrepancies in reports of exposure to community violence, and we highlight the need for a theoretical framework to guide research on the implications of such discrepancies. Third, we present a theoretical model that includes factors that may precipitate the discrepancies as well as factors that arise once such discrepancies are evident. This model conceptually links informant discrepancies to youth maladjustment, and we review empirical work supporting it. Lastly, we demonstrate how this preliminary model can be used to guide future research that seeks to understand the mechanisms by which the informant discrepancies of youth victimization are linked to poor youth outcomes.

Definitional and Conceptual Issues

Community Violence Exposure

Violence is commonly conceptualized as intentional acts initiated by one person to cause harm to another (e.g., Guterman et al. 2000; Trickett et al. 2003); it often includes deliberate acts intended to cause physical harm against a person or persons in the community (Cooley-Quille et al. 1995). Non-physically injurious acts (i.e., threats) are also included in definitions of violence (Brennan et al. 2007; Guterman et al. 2000). This is important because perceptions and coping processes shape one’s interpretations of experiences deemed violent (Garbarino 2001; Garbarino et al. 1992). As such, some existing measures qualify items such as “chased” with the stipulation that there is some intention of harm on the part of the perpetrator (e.g., “when you thought you could really get hurt”), in order to reduce possible interpretive ambiguity around violence (e.g., Brennan et al. 2007). Most measures assess physical harm (e.g., being chased or hit); however, item content varies considerably across instruments (Brandt et al. 2005; Guterman et al. 2000; Trickett et al. 2003). Exposure to violence includes primary/direct (victimization), secondary (witnessed violence), and tertiary exposure (hearing about violence) (Brennan et al. 2007; Guterman et al. 2000). In the current paper, we focus on parent–child rating discrepancies of victimization.

Researchers also vary in their conceptions and use of definitions of “community” to characterize the setting in which violence occurs (e.g., Brandt et al. 2005; Guterman et al. 2000). Although some studies of community violence exposure specify the context of in-home exposure (e.g., Richters and Saltzman 1990), others do not (e.g., Bell and Jenkins 1993) or even specifically exclude victimization in the home (e.g., Cooley-Quille et al. 1995). Prior work is also inconsistent in its measurement of violence exposure that occurs at school. Indeed, several measures include items that specify violence exposure at school (Brandt et al. 2005).

As Guterman et al. (2000) noted, community connotes the “where” and the “who” of violent events experienced (p. 575). With regard to perpetrator characteristics, a few studies have assessed whether the perpetrator was a stranger, known to the youth, or a friend or family member (e.g., Lynch 2003), although the perpetrator is often not assessed in the measurement of community violence exposure (Brandt et al. 2005). Not surprisingly, the wide variation in the conceptualization of both violence exposure and community yields variability in measurement of these constructs. As illustrated in Fig. 1, there is some overlap across these different forms of youth victimization. We raise these issues to acknowledge the substantial co-occurrence in content areas assessed in different literatures measuring youth victimization (e.g., Finkelhor et al. 2007; Holt et al. 2007; Shields and Cicchetti 2001)Footnote 1; however, the current focus is on victimization by community violence.

Informant Agreement

The concordance in ratings between two informants is often referred to as “informant agreement”. As a metric, informant agreement reflects the extent to which informants’ ratings are congruent on a given domain. As a construct, informant agreement can reflect the extent to which informants share the same perspective on the domain being rated. In fact, when two informants’ ratings on any construct are components of the metric of agreement, agreement itself can be considered as a distinct construct, separate from its components (Edwards 2002; Kraemer et al. 2003). Historically, in the developmental and clinical sciences, disagreements between self and other ratings are often attributed to measurement error (e.g., Bernard et al. 1984; Fisher et al. 2006; Krosnick 1999; Richters 1992) and thus considered a nuisance. In contrast, psychometric work in the clinical and developmental literatures suggests that even when methodological features (e.g., item content and response scale) are kept constant across informants, informant disagreement nonetheless remains relatively high (e.g., Achenbach 2006; Baldwin and Dadds 2007). These disagreements remain high, even when it is quite clear from psychometric testing that measurement unreliability cannot parsimoniously explain disagreements (Comer and Kendall 2004; Rapee et al. 1994). In fact, researchers have recently found that this disagreement can be a useful metric of how children’s behavior varies across contexts, particularly when informants (e.g., parents, teachers) vary considerably with regard to the contexts in which they observe children’s behavior (e.g., De Los Reyes et al. 2009; Kraemer et al. 2003). Indeed, researchers across multiple fields [e.g., criminal justice (Kirk 2006), social psychology (Perez et al. 2005), and industrial-organizational psychology (Edwards 1994)] have begun to consider discrepancies as potentially meaningful information.

Agreement metrics typically focus on whether, at the sample level, two groups of informants’ reports (i.e., parents and youths) exhibit evidence of shared variance or similar patterns of reports. Agreement at the sample level is typically assessed using metrics such as kappa coefficients or Pearson r correlations (Cohen 1960; Saal et al. 1980). However, these metrics typically provide little information about whether the groups of informants indicate a similar level or severity of problems. Indeed, high agreement is possible when informants do not agree, so long as informants disagree consistently. For example, if youths in a sample tend to consistently rate victimization frequency three times as high as the parents in the sample, the correlation between their ratings would remain high, because correlation is not sensitive to additive or multiplicative ratings differences (Richters 1992). Additionally, because agreement metrics are typically sample statistics, they cannot be used to capture individual differences between informants’ reports within informant dyads.

Whereas informant agreement indicates shared information between raters, measurements of informant discrepancies represent the differences between informants’ reports (Richters 1992; Treutler and Epkins 2003). As a complementary metric to agreement, difference scores can be an intuitive and appealing approach to measuring agreement. Notably, different scores reflect which informant reports fewer or greater symptoms. However, discrepancy, as a variable, is not simply a continuum that reflects agreement on one end and disagreement on the other. Rather, it is a continuum that can range from negative values to positive values, with perfect agreement (discrepancy = 0) falling in the middle of the continuum. In sum, the terms “discrepancies” and “agreement” can denote similar constructs but can also denote specific metrics (e.g., correlations, difference scores) used to operationalize the constructs.

The focus of the current paper is on discrepant reports between parents and youths regarding youth violence exposure. We refer to “informant discrepancies” as a construct that represents discrepant perspectives and is typically assessed using difference scores and to “informant agreement” as a construct that represents shared perspectives and is typically assessed using sample statistics of correspondence (e.g., correlations, kappa coefficients). In the proposed theoretical framework, we primarily refer to discrepancies because the literature highlights one particular direction of discrepant perspectives (i.e., parents reporting lower levels of violence exposure than youths self-report), and our model is most applicable to this direction of discrepant perspectives. However, below we also consider other types of discrepancies and recommend directions for future research on these discrepancy types.

Agreement in Reports of Youth Violence Exposure

Numerous studies have documented poor agreement between parents and youths in reports of community violence exposure. To our knowledge, five published studies have assessed parent–youth agreement on both victimization and witnessed violence (i.e., Brennan et al. 2007; Ceballo et al. 2001; Howard et al. 1999; Raviv et al. 2001; Richters and Martinez 1993), and four additional studies have focused exclusively on reporting agreement on witnessed violence (i.e., Hill and Jones 1997; Kuo et al. 2000; Shahinfar et al. 2000; Thomson et al. 2002) (see summaries of sample characteristics and primary findings in Table 1). The cross-informant correlations vary considerably, ranging from non-significant and weak for reports of severe victimization (e.g., threatened with knife or gun, robbed) in the neighborhood (r = 0.11; Raviv et al. 2001) and witnessed violence (r = 0.12; Thomson et al. 2002), to moderate correlations for victimization (r = 0.37; Ceballo et al. 2001) and witnessed violence (r = 0.43; Kuo et al. 2000). In one noteworthy exception, Brennan et al. (2007) reported a strong cross-informant correlation for victimization (r = 0.72) and a moderate correlation for witnessed violence (r = 0.50). However, even in these studies, agreement at the highest level (r = 0.72) reflects that the two informants’ reports share 52% of the variance and would not be considered redundant [for a similar argument see Achenbach (2006)].

Direction of Discrepant Reports of Youth Victimization

Studies of informant discrepancies on ratings of violence exposure have focused largely on prevalence rates of violence exposure as reported by parents versus youth. Rates of violence exposure are typically lower for parent reports than for child reports, and the discrepancies are particularly striking for reports of victimization (e.g., Ceballo et al. 2001; Howard et al. 1999; Richters and Martinez 1993). In one of the first studies to document such discrepancies, Richters and Martinez (1993) observed that prevalence of child victimization according to parent reports (44%) was significantly lower than child self-reports (67%). Other studies have provided detailed item-level analyses and have tended to observe greater rates of victimization based on youth report relative to parent report. For instance, a study of multi-ethnic low-income 4th and 5th grade children found that 13% reported having been attacked or stabbed with a knife, whereas none of their caregivers reported that the children had experienced such victimization (Ceballo et al. 2001). The children were more than twice as likely than their caregivers to report that they had been chased by gangs or threatened with serious physical harm. Similarly, in an urban sample of youths aged 9–15 years, Howard et al. (1999) found that youths endorsed several incidents of victimization at significantly higher rates than did parents (i.e., being raped or threatened with rape, being attacked with a knife, and being shot). Across diverse and severe forms of victimization, youth self-reports translate into higher prevalence estimates of victimization relative to parent reports.

Demographic Associative Characteristics of Discrepancies

Given that low informant agreement is common, researchers have sought to identify the characteristics associated with levels of agreement. Studies generally suggest that the child’s sex and age are two demographic characteristics associated with informant discrepancies on reports of youth violence exposure. Specifically, lower parent–child agreement and greater discrepancies are often observed for male youths relative to female youths (e.g., Ceballo et al. 2001; Howard et al. 1999; Kuo et al. 2000), although there are exceptions (e.g., Richters and Martinez 1993). Additionally, prior work generally indicates that discrepancies—in the direction of children reporting higher levels of exposure than parents—increase with age (Ceballo et al. 2001; Howard et al. 1999; Kuo et al. 2000). Interestingly, the ways in which demographic characteristics are related to parents’ relative underreporting of youth violence exposure may also reflect some of the reasons why discrepancies arise. For example, Kuo et al. (2000) posited that older and male children may experience higher levels of exposure outside the home environment (and thus, parental underreporting reflects the fact that exposure is not observable to parents). This suggests that informant discrepancies may reflect variation between informants in the contexts in which they observe the assessed behaviors (e.g., Achenbach et al. 1987). Furthermore, the literature on adolescent social development, and, more specifically, on how and why adolescents disclose information to significant others about their whereabouts and activities may inform our understanding of potential linkages between informant discrepancies in reports of violence exposure and maladjustment. Indeed, adolescents typically undergo several social-developmental changes in interpersonal functioning (e.g., adolescent-parent dyad processes), and these changes can provide a useful foundation for understanding why parents may not be aware of youths’ experiences (Larson et al. 1996).

Discrepancies in Victimization Implicate Developmental Effects (DiVIDE) Framework

Taken together, the available research suggests that informant agreement in youth violence exposure is generally low and that youths typically self-report more victimization than parents. This pattern emerges for aggregated prevalence data, as well as discrepancies assessed between reports on specific victimization events. These discrepancies are particularly troubling, given the nature of the domains assessed. Because of the saliency and severity of direct exposure (victimization), discrepant reports of victimization might have particularly significant implications for the development of youth maladjustment. The paucity of research in this area may be due in part to the lack of a framework to guide conceptualizations of how or why such discrepancies are meaningfully linked to youth maladjustment.

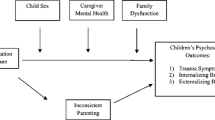

In order to begin addressing these gaps in the literature, we propose a broad conceptual framework called Discrepancies in Victimization Implicate Developmental Effects (DiVIDE) to serve as a foundation for investigating why discrepant perspectives on victimization may predict maladjustment. Although the proposed preliminary framework may be applicable to ratings of witnessed violence and other stressful experiences, we focus on discrepant ratings of victimization. We draw upon the growing body of theoretical and empirical literature suggesting that the role of parents in shaping youth development is characterized by dynamic youth- and parent-driven processes (Beveridge and Berg 2007; Darling et al. 2008; Granic and Patterson 2006; Tilton-Weaver et al. 2010). Specifically, the DiVIDE framework considers two broad categories of dyadic processes that are implicated in discrepant reports of youth victimization. We first describe factors that precipitate the discrepancies between parent and child reports and explain why these discrepancies exist (see Fig. 2). These precipitating factors may also support the utility of discrepant reports in predicting poor outcomes. We then consider factors that arise once discrepancies are evident and may further explain the utility of discrepant reports in predicting adolescent maladjustment (see Fig. 3).

Factors Precipitating Discrepancies

Whereas caregiver observation and outside information sources may contribute to parental knowledge in early and middle childhood, parents rely primarily on youth disclosure in later adolescence (Collins and Laursen 2004). Figure 2 illustrates the key factors hypothesized to precipitate informant agreement on victimization, including three factors (disclosure of victimization, caregiver observation, and outside sources of knowledge) that contribute to shared perspectives (agreement). Because the term “monitoring” has often been operationalized as “parental knowledge” of adolescent whereabouts and activities (Dishion and McMahon 1998), the parental monitoring literature provides a useful foundation for conceptualizing how and why discrepant perceptions of youth violence exposure are linked to maladjustment.

Selective Disclosure

Recent work highlights child-driven processes as critical to how parents acquire a knowledge base of their youth’s experiences (Keijsers et al. 2010; Kerr et al. 2010; Kerr and Stattin 2000). Although parent behaviors (e.g., active attempts to control youths’ whereabouts and activities, soliciting information) can contribute to parental knowledge (Crouter et al. 2005; Fletcher et al. 2004), recent research suggests that youths’ disclosure of information is a major source of parental knowledge (Frijns et al. 2005; Keijsers et al. 2010; Kerr and Stattin 2000; Stattin and Kerr 2000).

Parent–Youth Relationship Quality

Importantly, research also indicates that factors related to higher quality of the parent–adolescent relationship (i.e., youth-rated “trust” in parents and youth-rated parental acceptance) are associated with more disclosure and less secrecy (Smetana et al. 2006). Research also underscores the importance of parental warmth in fostering adolescent disclosure (Darling et al. 2006). Darling et al. (2006) investigated the reasons for adolescent non-disclosure of information and found that fear of consequences (e.g., parental anger) and emotional concerns (e.g., parent would not understand, or adolescent would be embarrassed or uncomfortable) were dominant. In this case, the construct of parental warmth (or lack thereof) seems to be an inherent aspect of adolescents’ reasons for non-disclosure. Further, warmth and acceptance in parents’ reactions to youth disclosure may predict increased feelings of connectedness to parents, which in turn predicts increased disclosure (Tilton-Weaver et al. 2010).

In cases where parent–youth discrepancies on victimization reflect parental “unawareness” of victimization experiences, these discrepancies may be precipitated by impairment in parent–youth relationship quality (e.g., lack of parental acceptance/warmth or impaired trust) and communication (e.g., non-disclosure). As Fig. 2 illustrates, youths’ disclosure of victimization contributes to parent–child agreement on victimization. Although this figure suggests that disclosure is a discrete event, one might also conceptualize disclosure as a process in which parental knowledge leads to the subsequent disclosure and positive adjustment (cf. Keijsers et al. 2010). Importantly, the direction of discrepant perspectives on which we focus—parents reporting less victimization than youths self-report—may reflect a lack of parental awareness of victimization (e.g., Ceballo et al. 2001; Howard et al. 1999; Richters and Martinez 1993). This likely has important implications for the processes that arise once discrepant perspectives occur.

Factors Mediating Links Between Discrepancies and Youth Maladjustment

Child Emotional Response

Youths whose parents are unaware of their victimization experiences likely lack a crucial source of emotional support. We posit that one reason shared perspectives may support positive adjustment over time is because they promote a key protective factor—youths’ feeling understood and accepted by caregivers—that is, in turn, related to adaptive coping and adjustment. Unfortunately, constraints on disclosure may present an important barrier to feeling understood and accepted. In a study of adolescents who reported talking to someone else about a violent experience in the past 6 months, 35% perceived others as uncomfortable or unwilling to discuss violent experiences and 46% kept feelings to themselves because they believed such discussion made another person uncomfortable or upset (Ozer and Weinstein 2004). We highlight the importance of feeling understood and accepted, because victimization is an especially strong personal affront and isolating experience (O’Donnell et al. 2006). Importantly, O’Donnell et al. (2006) found that isolation and self-estrangement mediated the association between victimization and internalizing (depression and anxiety) symptoms. We posit that disclosure of victimization and accompanying feelings might prevent or reduce the sense of isolation and estrangement that may contribute to maladjustment in victimized youths.

Constraints on disclosure may cause individuals to inhibit discussion of the event or to suppress thoughts, and thereby impair adaptive coping (Kliewer et al. 1998; Lepore et al. 1996). On the other hand, if discussing the event allows youths to express thoughts and feelings, this discussion may help to reduce stress-related symptoms in victimized youths. Indeed, violence-exposed youths who feel constrained in talking about their experiences are more likely to experience internalizing symptoms (Kliewer et al. 1998; Ozer 2005; Ozer and Weinstein 2004). Furthermore, some researchers posit that keeping a secret from an intact social network can be more deleterious than not having a social network at all (Cole et al. 1996; Pennebaker and Chung in press).

Caregiver Support

The socialization of coping with violence may further explain why shared perspectives are adaptive (Kliewer et al. 2006; Power 2004; Zimmer-Gembeck and Locke 2007). According to Kliewer et al. (2006) model of coping socialization, children’s coping strategies are influenced, in part, by caregiver coaching, or direct suggestions for how to cope with violence. We posit that parents who do not know about youths’ victimization are likely impaired in their ability to suggest adaptive coping responses to victimization events. Conversely, caregivers who are well informed of their children’s experiences with violence may be better equipped to suggest appropriate and effective coping strategies. It is important to acknowledge, however, that caregivers can be protective both by coaching youths to cope with victimization after it has occurred and by helping youths to cope proactively and prevent or minimize future victimization (Aspinwall and Taylor 1997; Kliewer et al. 2006).

Protective Function of Informant Agreement

Figure 3 provides a broad conceptual framework for considering how and why informant discrepancies on victimization may be linked to maladjustment for victimized youths. We note that parental warmth is likely a precursor to youth disclosure (Fig. 2). Youths with stronger caregiver support (e.g., those who perceive caregivers as warm and accepting) may be more likely to disclose personal experiences of victimization, therefore leading to greater parent–youth agreement. As Fig. 3 illustrates, shared perspectives may lead to the adjustment through caregiver responsiveness and youth coping. Specifically, when caregivers know about youths’ victimization experiences and share youths’ perspectives, they are likely better equipped to help youths cope with victimization.

Preliminary Empirical Support for the Proposed DiVIDE Framework

The research summarized below regarding the causes and consequences of informant discrepancies provides preliminary empirical support for the proposed DiVIDE framework. Whereas discrepancies (discrepant perspectives) may be a risk factor for victimized youths, agreement (shared perspectives) may serve as a protective factor for these youth (Fig. 3).

Parent–Child Relationship and Discrepancies

Some empirical research supports the idea that quality of the parent–child relationship is related to parent–child discrepancies on ratings of behavior and psychological symptoms (e.g., Grills and Ollendick 2002; Treutler and Epkins 2003) and exposure to violence (e.g., Ceballo et al. 2001). Family conflict and stress have been related to parent–child discrepancies (Grills and Ollendick 2002; Jensen et al. 1988), perhaps because family conflict impairs communication (Grills and Ollendick 2002). A child’s perceptions of the parent as positively evaluating, affectionate, and providing emotional support—commonly referred to as “parental acceptance”—have been related to fewer discrepancies in psychological symptoms in both clinic-referred and non-referred samples (Kolko and Kazdin 1993; Treutler and Epkins 2003). This literature used the parental acceptance scale of the Child Report of Parent Behavior Inventory (CRPBI; Schaefer 1965) that included items such as “understands my problems and my worries”, “makes me feel better after talking over my worries with him/her”, and “speaks to me in a warm and friendly voice”. Specifically, Kolko and Kazdin (1993) found that parental acceptance was associated with parent–youth agreement for externalizing behavior in a sample of clinic-referred youths aged 6–13. In a community-based sample of adolescents (aged 10–12), parental acceptance also was related to discrepancies in reports of externalizing symptoms (Treutler and Epkins 2003). Finally, Howard et al. (1999) examined the association between parent and youth relationship characteristics and informant discrepancies for youth’s exposure to violence. They found that youth–caregiver dyads with low agreement were characterized as having less communication, less parental involvement, and less parental monitoring.

Surprisingly, there is a dearth of qualitative research that has explored the reasons for parent–child informant discrepancies. One noteworthy exception is a study conducted by Bidaut-Russell et al. (1995), which investigated the reasons for discrepancies in reports of psychological symptoms. Based on open-ended responses to interview questions, the authors conducted a thematic analysis of reasons for anticipated informant disagreement. Parental unawareness emerged as one common reason adolescents anticipated that parents would provide conflicting reports. Adolescents most commonly attributed lack of parental awareness to their own non-disclosure of information. Less commonly mentioned reasons for parental unawareness included adolescents’ lack of emotional expressiveness, lying to parents, and lack of parental attentiveness. Notably, the themes that emerged in this study dovetail with developmental literature regarding the importance of adolescent disclosure.

Predictive Utility of Discrepancies

Discrepant Reports of Victimization

A core feature of the DiVIDE model is the hypothesized association between discrepant perspectives on violence exposure and youth maladjustment. Support for the proposed link between discrepant perspectives and maladjustment comes from two cross-sectional studies. Specifically, Ceballo et al. (2001) investigated parent–youth agreement on victimization (10 items) and witnessed violence (10 items) as a predictor of youths’ psychological symptoms in 104 mother–child pairs (grades 4–5). They found that parent–youth agreement on victimization significantly added to the prediction of child-reported PTSD and parent-reported internalizing (but not externalizing) symptoms, after controlling for demographic variables and parents’ report of youths’ exposure to violence. The authors suggested that processes such as family support might account for this association, although the role of family was not examined in their study. Similarly, a study of 333 dyads in urban public housing developments found that parent–youth agreement was related to poor parent–child communication, low parental monitoring, symptoms of distress, low self-esteem, low problem-solving, and perpetration of violence (Howard et al. 1999).

Discrepancies in Other Domains

A growing body of literature has investigated the predictive utility of discrepancies between parent and child reports of behaviors across diverse domains of assessment (e.g., child’s behavior and emotional problems, negative parenting, parent–child relationship quality, and teenage driving restrictions), providing an empirical foundation for the idea that discrepancies longitudinally predict poor youth adjustment (e.g., Beck et al. 2006; Ferdinand et al. 2004; Guion et al. 2009; Israel et al. 2007; Pelton et al. 2001). Although theoretical frameworks are lagging behind empirical findings, some researchers have suggested that discrepant perspectives lead to the maladaptive dyadic and relationship processes, which in turn lead to maladjustment. For example, discrepant perspectives on parenting and dyadic processes are believed to create additional strain for families, which can adversely impact youths’ psychosocial adjustment (e.g., Guion et al. 2009; Pelton et al. 2001). Similarly, discrepant perspectives on parental monitoring may reflect a lack of access to information that can impair parents’ abilities to protect youths from harm (De Los Reyes et al. in press-a). When parents report fewer problems than youth, these discrepancies may suggest a lack of youth disclosure of information about feelings or impaired communication styles (Barker et al. 2007). Overall, researchers surmise that factors related to parent–child communication (e.g., lack of parental awareness, lack of child disclosure) may ultimately explain why discrepancies are broadly related to youth maladjustment.

Taken together, a growing body of empirical literature suggests that parent–youth discrepancies on ratings of behavior are linked with maladjustment. The proposed DiVIDE framework provides a model to explain why discrepancies may predict future dysfunction for victimized youths. We contend that when discrepancies reflect parental unawareness of youth victimization, the caregiver is not able to provide appropriate coping suggestions or to offer social and emotional support; this disconnect likely impairs the youths’ adjustment, which may be exacerbated by the more general lack of acceptance and social support perceived by the youth.

Suggestions for Future Research

Information Sources

The proposed DiVIDE framework provides a theoretical model to explain why discrepancies may predict future dysfunction for victimized youths; however, there are several aspects of the model that require further exploration. For example, the model highlights youths’ disclosure of information as a primary source through which parents acquire the knowledge of youths’ exposure to violence. Because parents spend less time directly monitoring and observing their children’s whereabouts in adolescence (Collins and Laursen 2004), the model emphasizes youth disclosure as a primary information source (Fig. 3), although we acknowledge that parents might obtain information about youths’ victimization through sources other than youths’ disclosure (Fig. 2). The literature to date is relatively limited with regard to what outside sources of information exist beyond other family members and direct observation, and this remains an important direction for future research (e.g., Crouter et al. 2005; Waizenhofer et al. 2004). Interestingly, prior work suggests that when parents obtain information of youth whereabouts through other sources of information (i.e., not via youth disclosure), this knowledge is less protective against and more strongly associated with adolescent risky behavior (Crouter et al. 2005). Future research could explore the implications of parents obtaining knowledge of youth exposure to violence from outside information sources, such as school, police, direct observation, or possibly review of the youths’ electronic communications with their friends (e.g., email, Facebook, and text messages).

Link Between Discrepant Perspectives and Psychopathology

Discrepancy as Risk Versus Protective Factor

The DiVIDE model posits that increased parent–youth discrepancies are predictive of poor outcomes and thus assumes that the presence of fewer discrepancies (i.e., more agreement) is related to better outcomes. It might be, however, that under certain circumstances, parent–youth agreement on reports of victimization is related to the indices of maladjustment (e.g., aggression). For example, when parents know that their child has been exposed to violence, they may encourage their children to engage in aggressive behavior in response to the violence (Kliewer et al. 2006; Malek et al. 1998; Solomon et al. 2008). In fact, one study of victimized urban youth found that over half of their parents believed that fighting back was an effective way of stemming the victimization (Solomon et al. 2008). It is likely that in some violent communities, parents may encourage youths to retaliate aggressively, as such responses may be adaptive within a violent context (Anderson 1999). Yet, most researchers caution that aggressive retaliation likely increases youths’ risk for injury to the self and others (Guerra et al. 2003). Thus, future work might consider whether parental attitudes toward violence influence the extent to which parent–youth reporting discrepancies operate as risk versus protective factors in the development of aggressive behavior.

Discrepant perspectives in adolescence also may reflect individuation, an important and healthy developmental process. Indeed, some literature suggests that discrepant perspectives between parents and youths may be a healthy and normal part of adolescent development (Ohannessian et al. 2000; Welsh et al. 1998). Conversely, high levels of agreement may, in some cases, reflect enmeshed family patterns characterized by psychological and emotional fusion among family members. Enmeshment is associated with poor adjustment outcomes, perhaps because its constraining and intrusive nature impairs youths’ autonomy and sense of power or control in their interactions with parents (Barber and Buehler 1996). Under such circumstances, high levels of agreement would not be adaptive. We encourage future work to examine contexts in which discrepancies may be protective, and contexts in which agreement may predict poor adjustment.

Longitudinal Research on DiVIDE

Although we posit that parent–youth disagreement contributes to maladjustment (Ceballo et al. 2001; Howard et al. 1999), it is possible that youth psychopathology contributes to parent–youth discrepancies on violence exposure. For example, youth depression is related to youths’ self-reporting greater levels of victimization relative to peer reports (De Los Reyes and Prinstein 2004). This finding is consistent with prior theoretical work that an informant’s levels of depressed mood result in that informant attending to and reporting negative as opposed to positive behaviors (McFarland and Buehler 1998; Richters 1992; Youngstrom et al. 1999). Alternatively, youth-perceived internalizing and externalizing symptoms may relate to an increased pressure of youth social desirability, thereby inhibiting youths from disclosing information about victimization experiences to caregivers. Depression may intensify motivational determinants of non-disclosure, such as fear of disapproval or disbelief, embarrassment, self-blame, and impaired self-efficacy (i.e., lack of belief in one’s ability to effectively disclose information). These factors, in turn, might inhibit disclosure among victimized youth (Bussey and Grimbeek 1995).

Delinquent and aggressive characteristics may also contribute to non-disclosure. Youths who perpetrate violence may be less likely to discuss their personal experiences with victimization, for fear of parental disapproval, risk of parental sanctions on activities (Darling et al. 2006; Kerr et al. 1999) or pressure within their peer groups to hide information from their parents (Stattin and Kerr 2000). Indeed, adolescents who engage in delinquent acts tend to hide more information from their parents (Keijsers et al. 2010; Marshall et al. 2005). Further, youths who commit delinquent (especially violent) acts are at increased risk for victimization in the community relative to youths who do not (DuRant et al. 1994; Lynch and Cicchetti 1998).

The DiVIDE framework focuses on one direction of discrepant reporting (youths self-reporting higher levels of victimization than parents report), as the literature indicates a high prevalence of parents reporting fewer youth exposure incidents relative to youths (e.g., Ceballo et al. 2001; Hill and Jones 1997; Howard et al. 1999; Kuo et al. 2000; Richters and Martinez 1993). However, in the relatively rare cases in which parents report higher levels of youth violence exposure relative to youths, these discrepant perspectives may also reflect maladaptive processes that place youths at risk for maladjustment. Whereas the DiVIDE framework suggests that discrepant reports affect coping processes, it is also possible that discrepant reports reflect coping processes. For example, youths’ reporting fewer events relative to parents may reflect youth coping efforts, such as repressing or denying that victimization has occurred (i.e., disengagement coping; Compas et al. 2001). Some forms of disengagement coping (i.e., disengagement from the stressor by denying its existence or avoiding unwanted thoughts and emotions associated with it) have been associated with an increased likelihood of youth externalizing symptoms (Compas et al. 2001). Alternatively, youths’ reporting fewer exposure events relative to caregivers may reflect youths’ feelings of shame in endorsing victimization experiences to an interviewer. In fact, proneness (i.e., an affective disposition that might be associated with both youths’ denying experiencing trauma and opting to hide information from significant others, such as parents) has been linked to a host of maladjustment outcomes (Tangney et al. 1992). Future research should examine whether youths’ reporting fewer victimization experiences relative to parents (or other informants) is in fact associated with maladjustment and investigate the processes (e.g., disengagement coping) or child characteristics (e.g., shame proneness) that might explain this association.

Discrepancies and Environmental Contexts

The model draws attention to interpersonal context—characteristics of the parent–youth relationship (e.g., youth-rated parental warmth)—that may influence youth disclosure and thus contribute to discrepant reports of youth victimization. Victimization is also embedded in environmental contexts (home, neighborhood, and school settings) that influence discrepant perspectives. Notably, informant discrepancies in ratings of youth behavior can reflect differences in the settings in which behavior is observed by different informants (e.g., Achenbach et al. 1987; De Los Reyes and Kazdin 2005; Kraemer et al. 2003). Furthermore, parent–youth disagreement on witnessed violence appears to be higher for exposure at school than at home (e.g., Raviv et al. 2001; Thomson et al. 2002).

Examining discrepancies within specific settings may not only help to understand why discrepancies occur but also under what circumstances (e.g., contexts for victimization, family characteristics) discrepancies are risk factors for dysfunction. As illustrated in Fig. 1, contexts for victimization might include setting or perpetrator. For example, if youths experience and report victimization perpetrated by non-parental family members and parents do not, this may indicate a chaotic home environment typified by chronically low levels of parental monitoring. Some literature suggests that victimization by a close other may be more damaging than victimization by stranger (Lynch 2003), although this may not always be the case. Specific types of victimization such as sexual assault or rape may warrant special attention to understand how a victim’s relationship with the perpetrator affects subsequent coping processes and adjustment (Littleton and Radecki Breitkopf 2006). Where the perpetrator is known to the caregiver, youths may feel inhibited in disclosing victimization to caregivers, although little empirical work has investigated this supposition. Further, given that contexts for victimization change over the course of childhood and adolescence (Finkelhor et al. 2009), it is likely that these changing contexts also impact discrepancies. Therefore, a critical next step for future research is to examine the ways in which informant discrepancies on victimization are systematically related to the context (e.g., setting and relationship with perpetrator) of victimization. Finally, the utility of the DiVIDE model might vary based on family characteristics (e.g., marital status, employment) that have been associated with parental monitoring and child adjustment (Bumpus and Rodgers 2009; Crouter and Bumpus 2001). We encourage future research to examine the role of family structures and demographic characteristics when applying and testing the model.

Methodological Challenges and Measurement Issues

Informant Discrepancies in Relation to Item Content

There are a number of methodological challenges to assessing informant discrepancies. First, the diversity in the forms of violence exposure is particularly challenging (Brandt et al. 2005; Brennan et al. 2007; Trickett et al. 2003). For example, Trickett et al. (2003) noted that most studies scored violence exposure “implicitly and arbitrarily,” by aggregating item responses into summary indices, without a theoretical framework to guide such aggregation. Several investigators have applied sophisticated modeling techniques (e.g., Rasch modeling) to address these concerns and in particular the issue of equally weighting exposure items despite differences across items in the severity of the exposure experiences assessed. Specifically, researchers have applied item response theory (IRT) to model the severity and frequency of assessed exposure experiences (e.g., Brennan et al. 2007; Kindlon et al. 1996; Selner-O’Hagan et al. 1998).Footnote 2,Footnote 3 Accordingly, one challenge for future work is considering that the impact of discrepancies likely depends on the domain of victimization being rated. For example, discrepancies on items such as “attacked with a weapon” may be more consequential than discrepancies on items such as “threatened”.

Statistically Modeling Informant Discrepancies

Our theoretical framework focused on only one direction of discrepant perspectives (i.e., youths self-reporting greater violence exposure relative to parent reports about youths). Therefore, it is important that future research considers both the direction of discrepant perspectives and the heterogeneity and patterns of discrepancies in the population. We also encourage researchers to consider both variable-centered and person-centered analytic approaches in future work. Variable-centered analytic approaches are common in the literature and assume that the population is homogeneous with respect to how predictors operate on the outcomes (Laursen and Hoff 2006). For example, these approaches employ discrepancies as predictors of outcomes or correlates in relation to other variables (e.g., informant characteristics; for reviews see De Los Reyes and Kazdin 2004, 2005; Owens et al. 2007). In addition to discrepancy scores, a variety of variable-centered approaches may be used to examine informant agreement, such as principal components analysis (Kraemer et al. 2003), structural equation modeling (Bartels et al. 2007), hierarchical linear modeling (Kuo et al. 2000), and polynomial regression (Edwards 2002).

There is also growing interest in the application of person-centered approaches to examine discrepancies (e.g., De Los Reyes et al. in press-a; De Los Reyes et al. in press-b; Romano et al. 2004). In contrast to variable-centered approaches, person-centered approaches consider that different subgroups of individuals may underlie the population, such that variables are related to one another in different ways for different groups of people (Laursen and Hoff 2006; Magnusson 2003). These approaches may be particularly useful for examining discrepant perspectives on reports of victimization. Indeed, it is unclear whether there are underlying subgroups in the population with different patterns of reporting agreements, as all informant discrepancies might not operate in the same way. For example, in a sample in which parent and youth reports largely disagree on violence exposure, some parents may report more youth exposure than youths self-report, some youths may self-report more exposure than their parents report about them, and some parents and youths might largely agree on the level of exposure. Thus, a person-centered approach may clarify whether there are patterns of agreement in the population, such that parent–child dyads vary in whether parents over- or underestimate youths’ violence exposure in some domains and not others.

Both variable-centered and person-centered analyses have been used to evaluate the psychometric properties (e.g., test–retest reliability) of discrepancy scores, considering that parent–youth discrepancies may be most predictive of maladjustment when these discrepancies are stable over time (De Los Reyes et al. 2010; De Los Reyes et al. in press-a). However, it is not clear whether and how stability on discrepant reports of victimization should be examined. For example, discrepant reports of serious victimization events may lack stability from 1 year to the next but nevertheless have profound effects for youths’ coping resources and adjustment. This issue invites new questions regarding the optimal timeframe (e.g., past-year, lifetime) for informants’ reports. Past-year incidence typically is considered to be an optimal timeframe for collecting informant reports in order to maximize the likelihood of accurate recall, especially because lifetime prevalence reports may be inaccurate when children are recalling stressful events that occurred at a very young age (Howe et al. 2006). We encourage future research to examine stability within and between informants and to explore the optimal timeframe for obtaining informants’ ratings.

Implications for Intervention and Prevention

The DiVIDE model may also inform the assessment and treatment of victimized youths. Interestingly, some research suggests that clinicians report lower levels of their youth clients’ exposure to violence than clients’ self-report (Guterman and Cameron 1999). Although this may indicate that some forms of exposure do not reach a threshold deemed clinically significant from the clinician’s perspective, this finding may also indicate that victimization is sometimes undetected and unaddressed for youths already in treatment. Other research suggests that victims do not receive services. For example, one study found that after controlling for several predictors (e.g., demographics, depression, and externalizing problems), victimization was associated with significantly lower odds of subsequent mental health service use in high school students (Guterman et al. 2002). Further, Guterman et al. (2002) surmised that, although exposure to violence may play a causal role in youths’ mental health problems and subsequent treatment, their receipt of services likely depends on parents’ detection of problems that result from exposure to violence.

Youths who do not disclose their victimization experiences to caregivers may, therefore, have unique intervention needs. School-based mental health services may offer a unique opportunity for intervention with these youths because these services are delivered in the school and do not rely on parents’ detection of problems. Interestingly, some research indicates that school mental health programs may serve a more at-risk population with higher levels of violence exposure relative to community-based mental health services (Weist et al. 2002). It is important to consider that youths who do not feel comfortable discussing their victimization experiences with parents must be willing to disclose their victimization in the context of assessment/screening in order to obtain services. As indicated in Table 1, most studies documenting discrepancies on exposure to violence did in fact rely on interview methods. While a variety of measures have been developed for the assessment of violence exposure (Brandt et al. 2005), an interview format may be preferable to paper-and-pencil format because the interview process itself may be therapeutic (Weist et al. 2001).

Future work might further explore formal service use and informal sources of support that exist for youths whose parents are unaware of their victimization. Moreover, interventions might target contexts in which parents are aware of youth victimization. For example, hospital-based interventions for victimized youths present unique opportunities to help victimized youths who may have dropped out of mainstream contexts for interventions (e.g., schools; Zun et al. 2006). In fact, visits to the emergency room may be “teachable moments” for assault-injured youths and their parents (Johnson et al. 2007), and these interventions might consider discrepant perspectives as a potential target for change. Shared perspectives may facilitate the adaptive changes in the very processes that are also targeted in clinical interventions, such as coping and parenting behaviors (Pynoos and Nader 1988; Kazdin 2003).

Concluding Comments

Although discrepant reports can pose interpretive dilemmas, they may also provide useful information about processes that occur when two informants perceive events differently. We posit that discrepant perspectives on youths’ victimization experiences may contribute to an increased likelihood of developing psychosocial maladjustment, and in this paper we propose a preliminary conceptual model to describe key processes that might contribute to and result from discrepant reports. Given research indicating that parents typically report lower levels of youths’ victimization than youths’ self-report, we focused on the implications of discrepant reports that reflect a lack of youth disclosure—and subsequent lack of parental awareness—of youth victimization. This lack of parental awareness likely impairs caregiver responsiveness (e.g., suggestions for how to cope) and social support resources that in turn affect youths’ adjustment. On the other hand, shared perspectives might facilitate positive adjustment for victimized youths through parental responsiveness and additional coping resources. Our framework therefore suggests that informant discrepancies can enhance our understanding of risk and protective processes for violence-exposed youths. We encourage future research to examine dyadic processes related to discrepant perspectives in order to empirically test aspects of the DiVIDE framework. We also encourage further conceptual work to consider the meaning and utility of informant discrepancies, in violence exposure as well as other domains of assessment, to guide research that must use conflicting information from different informants.

Notes

Specifically, the literature on peer victimization often examines different types of victimization (e.g., physical, verbal, and relational), and may delineate overt (physical and verbal) forms of victimization from covert (relational) forms of victimization (Crick and Grotpeter 1996; Prinstein et al. 2001); much of this research has focused on victimization by peers and at school. Whereas threats to exact physical harm are often considered under the rubric of community violence (Guterman et al. 2000), neither verbal forms of victimization (e.g., being called names, taunted, or teased) nor relational forms of aggression (e.g., malicious gossip or organized social exclusion) are typically included on community violence exposure checklists. Furthermore, some aspects of maltreatment do not overlap with community violence measures. For example, emotional abuse and neglect are two forms of maltreatment which are not typically conceptualized as “victimization” by community violence measures (Vorrasi et al. 2005).

As an illustration, Brennan et al. (2007) used IRT to empirically distinguish interpersonal violence from other forms of violence exposure, demonstrating that a victimization factor was comparable for parent and youth reports, with high correspondence (r = 0.72) for informants’ reports of victimization. As mentioned previously, such a large correlation can be identified between informants’ reports and the informants might nonetheless disagree if both informants differ systematically in the same general direction (e.g., youth consistently reports four times more experiences relative to parents).

Using IRT, Brennan et al. (2007) found that violence exposure could be distinguished along three dimensions: victimization (direct exposure), witnessed violence (secondary exposure), and hearing about violence (tertiary exposure). In this case, victimization is a single factor. Application of item response theory in this case requires relatively large sample sizes that may not be feasible in certain contexts (e.g., clinic-referred samples).

References

Achenbach, T. M. (2006). As others see us: Clinical and research implications of cross-informant correlations for psychopathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15, 94–98.

Achenbach, T. M., McConaughy, S. H., & Howell, C. T. (1987). Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 213–232.

Anderson, E. (1999). Code of the street: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. New York: W.W. Norton.

Aspinwall, L. G., & Taylor, S. E. (1997). A stitch in time: Self-regulation and proactive coping. Psychological Bulletin, 121, 417–436.

Baldwin, J. S., & Dadds, M. R. (2007). Reliability and validity of parent and child versions of the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children in community samples. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46, 252–260.

Barber, B. K., & Buehler, C. (1996). Family cohesion and enmeshment: Different constructs, different effects. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 433–441.

Barker, E. T., Bornstein, M., Putnick, D., Hendricks, C., & Suwalsky, J. (2007). Adolescent-mother agreement about adolescent problem behaviors: Direction and predictors of disagreement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 950–962.

Bartels, M., Boomsma, D. I., Hudziak, J. J., van Beijsterveldt, T. C. E. M., & van den Oord, E. J. C. G. (2007). Twins and the study of rater (dis)agreement. Psychological Methods, 12, 451–466.

Beck, K. H., Hartos, J. L., & Simons-Morton, B. G. (2006). Relation of parent-teen agreement on restrictions to teen risky driving over 9 months. American Journal of Health Behavior, 30, 533–543.

Bell, C. C., & Jenkins, E. J. (1993). Community violence and children on Chicago’s Southside. Psychiatry, 56, 46–54.

Bernard, H. R., Killworth, P., Kronenfeld, D., & Sailer, L. (1984). The problem of informant accuracy: The validity of retrospective data. Annual Review of Anthropology, 13, 495–517.

Beveridge, R. M., & Berg, C. A. (2007). Parent-adolescent collaboration: An interpersonal model for understanding optimal interactions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 10, 25–52.

Bidaut-Russell, M., Reich, W., Cottler, L. B., Robins, L. N., Compton, W. M., & Mattison, R. E. (1995). The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (PC-DISC v.3.0): Parents and adolescents suggest reasons for expecting discrepant answers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 23, 641–659.

Brandt, R., Ward, C. L., Dawes, A., & Flisher, A. J. (2005). Epidemiological measurement of children’s and adolescents’ exposure to community violence: Working with the current state of the science. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 8, 327–342.

Brennan, R. T., Molnar, B. E., & Earls, F. (2007). Refining the measurement of exposure to violence (ETV) in urban youth. Journal of Community Psychology, 35, 603–618.

Bumpus, M. F., & Rodgers, K. B. (2009). Parental knowledge and its sources: Examining the moderating roles of family structure and race. Journal of Family Issues, 30, 1356–1378.

Bussey, K., & Grimbeek, E. J. (1995). Disclosure processes: Issues for child sexual abuse victims. In K. J. Rotenberg (Ed.), Disclosure processes in children and adolescents (pp. 166–203). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ceballo, R., Dahl, T., Aretakis, M., & Ramirez, C. (2001). Inner-city children’s exposure to community violence: how much do parents know? Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 927–940.

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 37–46.

Cole, S. W., Kemeny, M. E., Taylor, S. E., & Visscher, B. R. (1996). Elevated physical health risk among gay men who conceal their homosexual identity. Health Psychology, 15, 243–251.

Collins, W. A., & Laursen, B. (2004). Parent-adolescent relationships and influences. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of Adolescent Psychology (pp. 331–362). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Comer, J. S., & Kendall, P. C. (2004). A symptom-level examination of parent–child agreement in the diagnosis of anxious youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, 878–886.

Compas, B. E., Connor, J. K., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 87–127.

Cooley-Quille, M. R., Turner, S. M., & Beidel, D. C. (1995). Emotional impact of children’s exposure to community violence: A preliminary study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 34, 1362–1368.

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1996). Children’s treatment by peers: Victims of relational and overt aggression. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 367–380.

Crouter, A. C., & Bumpus, M. F. (2001). Linking parents’ work stress to child and adolescent psychological adjustment. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 156–159.

Crouter, A. C., Bumpus, M. F., Davis, K. A., & McHale, S. M. (2005). How do parents learn about adolescents’ experiences? Implications for parental knowledge and adolescent risky behavior. Child Development, 76, 869–882.

Darling, N., Cumsille, P., Caldwell, L. L., & Dowdy, B. (2006). Predictors of adolescents’ disclosure strategies and perceptions of parental knowledge. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 667–678.

Darling, N., Cumsille, P., & Martinez, M. L. (2008). Individual differences in adolescents’ beliefs about the legitimacy of parental authority and their own obligation to obey: A longitudinal investigation. Child Development, 79, 1103–1118.

De Los Reyes, A., Alfano, C. A., & Beidel, D. C. (2010). The relations among measurements of informant discrepancies within a multisite trial of treatments for childhood social phobia. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 395–404.

De Los Reyes, A., Goodman, K.L., Kliewer, W. & Reid-Quiñones, K.R. (in press-a). The longitudinal consistency of mother-child reporting discrepancies of parental monitoring and their ability to predict child delinquent behaviors 2 years later. Journal of Youth and Adolescence.

De Los Reyes, A., Henry, D. B., Tolan, P. H., & Wakschlag, L. S. (2009). Linking informant discrepancies to observed variations in young children’s disruptive behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 637–652.

De Los Reyes, A., & Kazdin, A. E. (2004). Measuring informant discrepancies in clinical child research. Psychological Assessment, 16, 330–334.

De Los Reyes, A., & Kazdin, A. E. (2005). Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 483–509.

De Los Reyes, A., & Prinstein, M. J. (2004). Applying depression-distortion hypotheses to the assessment of peer victimization in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 325–335.

De Los Reyes, A., Youngstrom, E.A., Pabón, S.C., Youngstrom, J.K., Feeny, N.C., & Findling, R.L. (in press-b). Internal consistency and associated characteristics of informant discrepancies in clinic referred youths age 11–17 years. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology.

Dishion, T. J., & McMahon, R. J. (1998). Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 1, 61–75.

DuRant, R. H., Pendergrast, R. A., & Cadenhead, C. (1994). Exposure to violence and victimization and fighting behavior by urban black adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 15, 311–318.

Edwards, J. R. (1994). The study of congruence in organizational behavior research: Critique and a proposed alternative. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 58, 51–100. (erratum, 58, 323–325).

Edwards, J. R. (2002). Alternatives to difference scores: Polynomial regression analysis and response surface methodology. In F. Drasgow & N. W. Schmitt (Eds.), Advances in measurement and data analysis (pp. 350–400). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ferdinand, R. F., van der Ende, J., & Verhulst, F. C. (2004). Parent-adolescent disagreement regarding psychopathology in adolescents from the general population as a risk factor for adverse outcome. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113, 198–206.

Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R., & Turner, H. (2007). Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse and Neglect, 31(1), 7–26.

Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R. K., & Turner, H. A. (2009). The developmental epidemiology of childhood victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(5), 711–731.

Fisher, S. L., Bucholz, K. K., Reich, W., Fox, L., Kuperman, S., Kramer, J., et al. (2006). Teenagers are right-parents do not know much: An analysis of adolescent-parent agreement on reports of adolescent substance use, abuse, and dependence. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 30, 1699–1710.

Fletcher, A. C., Steinberg, L., & Williams-Wheeler, M. (2004). Parental influences on adolescent problem behavior: Revisiting Stattin and Kerr. Child Development, 75(3), 781–796.

Frijns, T., Finkenauer, C., Vermulst, A. A., & Engels, R. C. M. E. (2005). Keeping secrets from parents: Longitudinal associations of secrecy in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34, 137–148.

Garbarino, J. (2001). An ecological perspective on the effects of violence on children. Journal of Community Psychology, 29(3), 361–378.

Garbarino, J., Dubrow, N., Kostelny, K., & Pardo, C. (1992). Children in danger: Coping with the consequences of community violence. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Granic, I., & Patterson, G. R. (2006). Toward a comprehensive model of antisocial development: A dynamic systems approach. Psychological Review, 113, 101–131.

Grills, A. E., & Ollendick, T. H. (2002). Issues in parent–child agreement: The case of structured diagnostic interviews. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 5, 57–83.

Guerra, N. G., Huesmann, L. R., & Spindler, A. (2003). Community violence exposure, social cognition, and aggression among urban elementary school children. Child Development, 74(5), 1561–1576.

Guion, K., Mrug, S., & Windle, M. (2009). Predictive value of informant discrepancies in reports of parenting: Relations to early adolescents’ adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 17–30.

Guterman, N., & Cameron, M. (1999). Young clients’ exposure to community violence: How much do their therapists know? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 69, 382–391.

Guterman, N. B., Cameron, M., & Staller, K. (2000). Definitional and measurement issues in the study of community violence among children and youths. Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 571–587.

Guterman, N., Hahm, H., & Cameron, M. (2002). Adolescent victimization and subsequent use of mental health counseling services. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30, 336–345.

Hawley, K. M., & Weisz, J. R. (2003). Child, parent, and therapist (dis)agreement on target problems in outpatient therapy: The therapist’s dilemma and its implications. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 62–70.

Hill, H., & Jones, L. P. (1997). Children’s and parents’ perceptions of children’s exposure to violence in urban neighborhoods. Journal of the National Medical Association, 89, 270–276.

Holt, M., Finkelhor, D., & Kantor, G. (2007). Hidden forms of victimization in elementary students involved in bullying. School Psychology Review, 36(3), 345–360.

Howard, D., Cross, S., Li, X., & Huang, W. (1999). Parent–youth concordance regarding violence exposure: Relationship to youth psychosocial functioning. Journal of Adolescent Health, 25(6), 396–406.

Howe, M. L., Toth, S. L., & Cicchetti, D. (2006). Memory and developmental psychopathology. In D. Cicchetti & D. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Developmental neuroscience (2nd ed., Vol. 2, pp. 629–655). New York: Wiley.

Israel, P., Thomsen, P. H., Langeveld, J. H., & Stormark, K. M. (2007). Parent–youth discrepancy in the assessment and treatment of youth in usual clinical care setting: Consequences to parent involvement. European Child & Adolescent Psychology, 16, 138–148.

Jensen, P. S., Xenakis, S. N., Davis, H., & Degroot, J. (1988). Child psychopathology rating scales and interrater agreement: II. Child and family characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27, 451–461.

Johnson, S. B., Bradshaw, C. P., Wright, J. L., Haynie, D. L., Simons-Morton, B. G., & Cheng, T. L. (2007). Characterizing the teachable moment: is an emergency department visit a teachable moment for intervention among assault-injured youth and their parents? Pediatric Emergency Care, 23, 553–559.

Kazdin, A. E. (2003). Psychotherapy for children and adolescents. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 253–276.

Keijsers, L., Branje, S. J. T., Van der Valk, I. E., & Meeus, W. (2010). Reciprocal effects between parental solicitation, parental control, adolescent disclosure, and adolescent delinquency. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20, 88–113.

Kerr, M., & Stattin, H. (2000). What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Developmental Psychology, 36, 366–380.

Kerr, M., Stattin, H., & Burk, W. J. (2010). A reinterpretation of parental monitoring in longitudinal perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20, 39–64.

Kerr, M., Stattin, H., & Trost, K. (1999). To know you is to trust you: Parents’ trust is rooted in child disclosure of information. Journal of Adolescence, 22, 737–752.

Kindlon, D. J., Wright, B. D., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. (1996). The measurement of children’s exposure to violence: A Rasch analysis. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 64, 187–194.

Kirk, D. (2006). Examining the divergence across self-report and official data sources on inferences about the adolescent life-course of crime. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 22(2), 107–129.

Kliewer, W., Lepore, S. J., Oskin, D., & Johnson, P. D. (1998). The role of social and cognitive processes in children’s adjustment to community violence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 199–209.

Kliewer, W., Parrish, K., Taylor, K., Jackson, K., Walker, J., & Shivy, V. (2006). Socialization of coping with community violence: Influences of caregiver coaching, modeling, and family context. Child Development, 77(3), 605–623.

Kolko, D. J., & Kazdin, A. E. (1993). Emotional/behavioral problems in clinic and non-clinic children: Correspondence among child, parent, and teacher reports. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 34, 991–1006.

Kraemer, H. C., Measelle, J. R., Ablow, J. C., Essex, M. J., Boyce, W. T., & Kupfer, D. J. (2003). A new approach to integrating data from multiple informants in psychiatric assessment and research: Mixing and matching contexts and perspectives. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 1566–1577.

Krosnick, J. A. (1999). Survey research. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 537–567.

Kuo, M., Mohler, B., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. J. (2000). Assessing exposure to violence using multiple informants: Application of hierarchical linear modeling. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41, 1049–1056.

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33, 159–174.

Larson, R. W., Richards, M. H., Moneta, G., Holmbeck, G., & Duckett, E. (1996). Changes in adolescents’ daily interactions with their families from ages 10–18: Disengagement and transformation. Developmental Psychology, 32(4), 744–754.

Laursen, B., & Hoff, E. (2006). Person-centered and variable-centered approaches to longitudinal data. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 52, 377–389.

Lepore, S. J., Silver, R. C., Wortman, C. B., & Wayment, H. (1996). Social constraints, intrusive thoughts, and depressive symptoms among bereaved mothers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 271–282.

Littleton, H. L., & Radecki Breitkopf, C. (2006). Coping with the experience of rape. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 106–116.

Lynch, M. (2003). Consequences of children’s exposure to community violence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 6, 265–273.

Lynch, M., & Cicchetti, D. (1998). An ecological-transactional analysis of children and contexts: The longitudinal interplay among child maltreatment, community violence, and children’s symptomatology. Development and Psychopathology, 10, 235–257.

Magnusson, D. (2003). The person-centered approach: Concepts, measurement models, and research strategy. New Directions in Child and Adolescent Development, 101, 3–23.

Malek, M. K., Chang, B. H., & Davis, T. C. (1998). Fighting and weapon-carrying among seventh-grade students in Massachusetts and Louisiana. Journal of Adolescent Health, 23, 94–102.

Marshall, S. K., Tilton-Weaver, L. C., & Bosdet, L. (2005). Information management: Considering adolescents’ regulation of parental knowledge. Journal of Adolescence, 28, 633–647.

McFarland, C., & Buehler, R. (1998). The impact of negative affect on autobiographical memory: The role of self-focused attention to moods. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1424–1440.

O’Donnell, D. A., Schwab-Stone, M. E., & Ruchkin, V. (2006). The mediating role of alienation in the development of maladjustment in youth exposed to community violence. Development and Psychopathology, 18, 215–232.

Offord, D. R., Boyle, M. H., Racine, Y., Szatmari, P., Fleming, J. E., Sanford, M., et al. (1996). Integrating assessment data from multiple informants. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 1078–1085.

Ohannessian, C. M., Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., & von Eye, A. (2000). Adolescent-parent discrepancies in perceptions of family functioning and early adolescent self-competence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 24, 362–372.

Owens, J. S., Goldfine, M. E., Evangelista, N. M., Hoza, B., & Kaiser, N. M. (2007). A Critical review of self-perceptions and the positive illusory bias in children with ADHD. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 10, 335–351.

Ozer, E. J. (2005). The impact of violence on urban adolescents: Longitudinal effects of perceived school connection and family support. Journal of Adolescent Research, 20(2), 167–192.

Ozer, E. J., & Weinstein, R. S. (2004). Urban adolescents’ exposure to community violence: The role of support, school safety, and social constraints in a school-based sample of boys and girls. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 463–476.

Pelton, J., Steele, R. G., Chance, M. W., & Forehand, R. (2001). Discrepancy between mother and child perceptions of their relationship: II. Consequences for children considered within the context of maternal physical illness. Journal of Family Violence, 16, 17–35.

Pennebaker, J. W. & Chung, C. K. (in press). Expressive writing and its links to mental and physical health. In H. S. Friedman (Ed.), Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Perez, M., Vohs, K., & Joiner, T. (2005). Self-esteem, self-other discrepancies, and aggression: The consequences of seeing yourself differently than others see you. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 24, 607–620.

Power, T. G. (2004). Stress and coping in childhood: The parents’ role. Parenting: Science and Practice, 4, 271–317.

Prinstein, M. J., Boergers, J., & Vernberg, E. M. (2001). Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social–psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30(4), 479–491.

Pynoos, R. S., & Nader, K. (1988). Psychological first aid and treatment approach to children exposed to community violence: Research implications. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 1(4), 445–473.

Rapee, R. M., Barrett, P. M., Dadds, M. R., & Evans, L. (1994). Reliability of the DSM-III-R childhood anxiety disorders using structured interview: Interrater and parent–child agreement. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 33, 984–992.

Raviv, A., Erel, O., Fox, N. A., Leavitt, L. A., Raviv, A., Dar, I., et al. (2001). Individual measurement of exposure to everyday violence among elementary schoolchildren across various settings. Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 117–140.

Richters, J. E. (1992). Depressed mothers as informants about their children: A critical review of the evidence for distortion. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 485–499.

Richters, J. E., & Martinez, P. (1990). Things I have seen and heard: An interview for young children about exposure to violence. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health.

Richters, J. E., & Martinez, P. (1993). The NIMH community violence project: I. Children as victims of and witnesses to violence. Psychiatry, 56, 7–21.

Richters, J., & Saltzman, W. (1990). Survey of exposure to community violence: Self report version. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health.