Abstract

Positive parenting behavior is a robust predictor of child and adolescent psychosocial adjustment; however, contextual factors that relate to parenting itself are not well understood. This limited understanding is, in part, related to the fact that although theories have been put forth to explain the link between ecological context and parenting, there has been little integration of key concepts across these theories or empirical examination to determine their soundness. This review aims to begin to fill this gap by focusing on one contextual influence on parenting in particular, neighborhood context. Specifically, this review utilizes three constructs to provide a framework for integrating and organizing the literature on parenting within the neighborhood context: Danger (capturing crime and concerns for safety), Disadvantage (assessing the absence of institutional and economic resources), and Disengagement (noting the absence of positive social processes in the community). Findings from this review suggest evidence for an association between neighborhood context and positive parenting. Yet these results appear to vary, at least to some extent, depending on which neighborhood construct is examined, the way positive parenting is assessed, and specific sample demographics, including family income and youth gender and age. Findings from this review not only summarize the research to date on neighborhood and parenting, but provide a foundation for future basic and applied work in this area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Parenting is one of the most important influences on child psychosocial adjustment (see Newman et al. 2008, for a review), and many family-focused programs for youth hypothesize change in parenting behavior as the primary mechanism by which intervention effects on youth adjustment occur (see Henggeler and Sheidow 2011, for a review). Yet, relatively little is known in the literature about the contextual factors that influence parenting style or specific parenting behaviors. In addition, most programs that target parenting have yet to incorporate modules or techniques which specifically aim to address contextual factors into their curriculums (e.g., Al-Hassan 2009; Akers and Mince 2008). This may be due, at least in part, to the paucity of a larger organized framework or approach to integrating the existing literature on parenting in context, including the neighborhood context within which parenting occurs.

Within the developmental psychopathology literature, ecological systems models have traditionally embedded the neighborhood context within the “macrosystem”, or the system considered most distal to the child (see Cummings et al. 2002, for a review). A primary focus of research on the macrosystem is the direct link between neighborhood context, in particular, and youth adjustment (e.g., Bronfenbrenner 1979; also see Cummings et al. 2002 for a review). Relatively less attention, however, has been devoted to understanding the primary hypothesized mechanism through which neighborhood is theorized to influence child adjustment, parenting. Reviews on the association between neighborhood factors and child psychosocial adjustment have, in fact, included sections describing some findings related to the association between neighborhood and parenting (e.g., Jencks and Mayer 1990; Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2000). Such reviews also note that although the link between neighborhood context and parenting practices is critical to understanding the factors contributing to youth psychosocial adjustment, this area of research merits further theoretical and empirical development.

Building upon this assertion, several questions regarding the link between neighborhood contexts and parenting exist. First, what are the overarching constructs that represent the aspects of neighborhood typically examined in the literature on parenting? In addition, how are these overarching neighborhood constructs linked to parenting? Third, are there any moderators of the link between neighborhood contexts and parenting behavior? Finally, what are the mechanisms underlying associations between neighborhood context and parenting? A greater understanding of such issues may, in turn, better inform more tailored and specific parenting interventions in two ways: (1) Identifying parents that may be at-risk for engaging in maladaptive parenting behaviors as a function of the neighborhood contexts in which they reside, and (2) Utilizing prevention and intervention programming to address these factors and their impact on parenting.

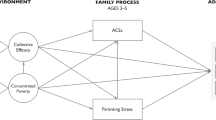

The theories that have been used as a basis for studies examining the link between neighborhood and parenting typically include the Family Stress Model (Conger et al. 2000) and/or Jencks and Mayer’s Resource Institutional Model (1990), both of which highlight the importance of available resources outside the family context and how such resources influence behavior. Empirical work on parenting utilized these theories by examining how the lack of community resources and the presence of safety concerns shape parenting (e.g., Chung and Steinberg 2006; Vieno et al. 2010). In addition, other studies drew from models such as the Social Disorganization Theory (e.g., Sampson 1992; Witherspoon and Ennett 2011) and Jencks and Mayer’s (1990) Collective Socialization and Epidemic Models, each of which highlights the importance of examining social processes (e.g., social control, modeling) linked to parenting behavior.

Although the relevance of these theoretical models should not be underestimated in terms of their contributions to the existing literature, the field lacks a common or unifying approach to interpreting existing research findings, which are seemingly contradictory at times. Whereas some research establishes a connection between neighborhood context and parenting, other work reports no association at all. Moreover, in the research that establishes a link, there are examples of different studies reporting opposite patterns of findings, even when they examine the same neighborhood and parenting constructs. In turn, the lack of a common and integrative framework makes it difficult to determine how to reconcile the current state-of-the-literature, particularly in light of variations in study design and quantitative methods as well. Accordingly, this review does not intend to propose a new theoretical model for understanding parenting in the neighborhood context, but rather to provide a common language and an organizing set of constructs that cut across existing theory and empirical research. Specifically, this review aims to organize and integrate the available literature utilizing a proposed common set of constructs, as well as to provide a common foundation and unifying language from which future work can evolve.

An Integrative Framework: Neighborhood Danger, Disadvantage, and Disengagement

Although terms are used somewhat inconsistently across research on neighborhoods in general and work on neighborhoods and parenting in particular, three overarching constructs emerge from both theoretical (Conger et al. 2000; Jencks and Mayer 1990; Sampson 1992) and empirical work (as described in the next sections) to date: Danger, Disadvantage, and Disengagement. For the purposes of this review, the construct of Neighborhood Danger encompasses the overall neighborhood condition with regard to the extent to which individuals feel unsafe in their neighborhood and/or objective data reveals a lack of safety (e.g., crime data). This aspect of the neighborhood context has been measured through social (e.g., presence of gangs, shootings, theft) and physical (e.g., the presence of insect-infested buildings, litter on the streets, abandoned buildings) aspects of the neighborhood that may pose harm or danger to residents living in the community.

The construct of Neighborhood Disadvantage is the most frequently examined neighborhood construct in the literature examining parenting behavior within the neighborhood context. It is used in the current framework to reflect the institutional and economic resources that are lacking in the community and is reflected through the demographic and economic climate within the neighborhood context. Constructs of Neighborhood Disadvantage have been measured through objective (e.g., US Census data on unemployment rates, percentage of households living below the poverty line, and percentage of female-headed households) and subjective (e.g., neighborhood income, appraisals of neighborhood schools, and police protection) reports. Although correlated with family income level (e.g., Alba et al. 1999; Charles 2003; McLoyd 1998), the construct of Neighborhood Disadvantage is unique from individual socioeconomic status such that it reflects larger institutional and economic need of the community and not necessarily the need of a particular family or caregiver. For example, prior research has shown members of some ethic/racial minority groups are more likely to live in disadvantaged neighborhoods, regardless of family income level (Alba et al. 1999; McLoyd 1998). This is of particular relevance, as the research examining parenting in the context of Neighborhood Disadvantage tends to focus on families from ethnic minority and low-income backgrounds. Additionally, it is highly possible for caregivers to live in neighborhoods where low and high-income areas are in close proximity to each other, particularly in urban areas of the country. In turn, this would increase the probability for caregivers to report on neighborhood elements that may reflect a different income level than their own.

Finally, the construct of Neighborhood Disengagement provides an overarching lens through which to organize research examining the social processes (e.g., social support, social control, emotional support) caregivers may or may not experience within their community context. It is the lack of these social processes that provides information regarding the level of social disengagement or lack of community involvement residents experience within the neighborhood. Most often, studies examining the link between Neighborhood Disengagement and parenting behavior use subjective measures to collect information about specific social processes. These include ratings on the level of emotional support (e.g., Dorsey and Forehand 2003; Gayles et al. 2009; Tendulkar et al. 2010), sense of belonging (e.g., Kohen et al. 2008; Tolan et al. 2003; Vieno et al. 2010), or level of social control present in the community (e.g., Dorsey and Forehand 2003; Law et al. 2002). In turn, neighborhoods in which caregivers report an absence of these positive social processes are considered in this review to have higher levels of Neighborhood Disengagement.

As already alluded to above, but worth highlighting again before proceeding, variables reflective of the aforementioned neighborhood constructs have been examined utilizing both objective and subjective approaches to measurement. Objective measures of neighborhood context are largely derived from national or local agencies, most typically the United States Census. These measures commonly include descriptive characteristics of the surrounding neighborhood, such as crime statistics (i.e., Neighborhood Danger in the current review; also see De Marco and De Marco 2010; Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2000 for reviews). Although subjective (e.g., maternal-report of perceived crime in the community) and objective (e.g., crime data) approaches are correlated, several researchers have highlighted that both types of measures convey important, albeit somewhat different, aspects of neighborhood context (e.g., Bass and Lambert 2004; Zalot et al. 2007, 2009). Whereas objective measurement may reduce common-reporter bias (i.e., a caregiver’s depressive symptomatology influencing her rating of her neighborhood context) and highlight factors that residents may not be aware of (e.g., drug trafficking, percentage of households living in poverty), subjective measures may better highlight relational aspects of neighborhood context most salient by residents in the neighborhood, such as sense of connection among community residents (e.g., Chung and Steinberg 2006; Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2000; Tolan et al. 2003).

On a final note before turning to the selection criteria for this review, it is important to highlight that although the proposed organizing neighborhood constructs are conceptualized here as distinct, they very likely overlap, at least to some extent. For example, prior research notes the higher incidence of Danger in more, rather than less, Disadvantaged communities (e.g., Caughy et al. 2001; Evans 2004; McLoyd 1998). With that point clarified, however, this review contends that each of the proposed neighborhood constructs has the potential to provide distinct information about the neighborhood context and, in turn, the capacity to enhance our understanding of parenting in the neighborhood context. Accordingly, the proposed constructs of Neighborhood Danger, Disadvantage, and Disengagement, whether examined individually or in combination, will be utilized in this review as a framework to organize and summarize existing research, as well as to extend the literature by highlighting directions for further study.

Method

Studies included in this review were selected by using search engine tools (e.g., PSYCINFO, PSYCARTICLES, Family & Society Studies Worldwide) and were also identified through citations in other research articles. In order to be included in the review, each article met the following selection criteria.

Selection of Studies

First, studies that quantitatively examined the link between neighborhood and parenting behavior were included in this review; however, qualitative studies were not. The large body of qualitative research that has examined the association between neighborhood context and parenting practices (see Jarrett 1999 for a review) has provided the opportunity for researchers to identify the factors most salient to caregivers in a particular community; however, it is difficult to disentangle the socioeconomic status of the families participating in these studies and the level of disadvantage in the neighborhood (see Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2000, for a review), which as highlighted above, may be critical for advancing this work.

In addition, the studies had to include at least one neighborhood context variable (i.e., a variable captured by Neighborhood Danger, Disadvantage, and/or Disengagement) as at least one of the primary study predictors examined. For example, neighborhood context could be the primary study predictor or among a set of primary study predictors to be examined, as long as parenting was included in the model as a primary outcome or dependent variable as described next. As described earlier, both subjective and objective measures of neighborhood context have been utilized and both will be included in this review. The neighborhood variable could have consisted of a single factor (i.e., percentage of families living in poverty, perceived crime rates) or it could have examined a neighborhood latent variable (i.e., consisting of two or more manifest variables such as perception of crime rates, extent of neighborhood problems, and level of social control).

The third criterion for an article to be included in this review is that the study included a parenting variable reflective of the authoritative, or positive parenting approach, which has been shown in prior theory and research to promote positive child psychosocial outcomes (see McKee et al. 2013, for a review). To provide some context for this choice, an authoritative parenting style was first identified by Baumrind (1966) and also referred to as positive parenting style, particularly by those more typically conducting research targeting underserved groups (e.g., Brody and Flor 1998; Jones et al. 2003). This parenting style is characterized by a constellation of parenting behaviors such as balanced levels of warmth, support, monitoring of activities, and appropriate and consistent discipline and, in turn, has been linked to optimal child outcomes (McKee et al. 2013; Nelson et al. 2006; Newman et al. 2008). Given that the literature studying the links between neighborhood context and parenting tends to focus on parenting style, or individual parenting behaviors (e.g., monitoring), these individual parenting behaviors will be defined here briefly for clarity of terms.

In terms of parenting behavior, caregiver monitoring is the most commonly studied parenting construct in the neighborhood literature and often includes behaviors such as enrolling children in extra-curricular activities and programs, being aware of a child’s peer group, and knowing a child’s whereabouts and activities in the neighborhood (see Crouter and Head 2002 for a review). The extent to which caregiver knowledge about child activities is a function of monitoring, a distinct parenting construct, or some combination has been extensively discussed in the literature (e.g., Jones et al. 2002; Liu et al. 2009); however, studies of neighborhood context tend to include measures of caregiver knowledge about child activities as markers of monitoring. In turn, monitoring will be used to refer to both monitoring behaviors and knowledge regarding youth activities in this review. Caregiver warmth has also been thoroughly examined in the literature studying the relationship between neighborhoods and parenting as it has been closely linked to youth psychosocial outcomes (see Serbin and Karp 2004 for a review). Definitions of warmth vary to some extent across studies, but include such behaviors as providing positive verbal comments about the child’s behavior, physical reinforcement that conveys support (e.g., hugs, kisses) and engaging in active listening (DiBartolo and Helt 2007). The last parenting dimension highlighted in neighborhood context research is behavioral control (e.g., Gayles et al. 2009; Kohen et al. 2008) and is often referred to as appropriate and consistent discipline practices. This includes stating a consequence, explaining why a rule is enforced, and limit setting (Caron et al. 2006). Overall, these three parenting behaviors have been linked to a number of positive youth psychosocial outcomes including lower levels of externalizing and internalizing behaviors and higher levels of academic achievement and self-esteem (see Crouter and Head 2002; Serbin and Karp 2004; Spera 2005 for reviews).

By focusing on these particular positive parenting behaviors most often studied in the neighborhood literature, findings from this review may help to inform the development and utilization of future clinical prevention and intervention programs for parents by highlighting those positive parenting behaviors that may be vulnerable in certain contexts. Of note, studies that included latent variables consisting of more than one parenting behavior were included as long as at least one of the factors mapped onto the aforementioned parenting behaviors associated with positive child psychosocial adjustment and the other parenting behaviors were scored in a way that assesses a parenting as a protective factor. To achieve the goal of parsimony in our review, will refer collectively to these constructs as reflecting of positive parenting.

Finally, the review was limited to studies that examined parenting behaviors in adults identified as a primary caretaker. This includes biological or adopted mothers and fathers, as well as other individuals who may be the primary care provider (i.e., grandparents, aunts, uncles, etc.) to a child. It should also be noted that a few articles that did fit the aforementioned selection criteria were not included in this review due to substantive methodological concerns (e.g., inconsistent administration of study measures, use of measures with poor psychometrics, failure to examine or to report the association between neighborhood context and parenting although both variables were included in study).

Results

Findings from existing research examining the link between neighborhood context, defined as Neighborhood Danger, Disadvantage, and/or Disengagement, and specific parenting outcomes, either parenting style or behaviors reflective of positive parenting style, are summarized in Table 1. First, study findings about direct associations between neighborhood construct variables, Neighborhood Disengagement, Danger, or Disadvantage and positive parenting will be presented and explained through the contributing theoretical frameworks. Next, a discussion of potential moderators and mediators of the link between the neighborhood constructs and positive parenting will follow. Finally, studies that examined two or more neighborhood construct variables in a single model, whether as separate variables or a latent construct, will be reviewed.

Studies that Examined Direct Associations Between Neighborhood and Positive Parenting

As demonstrated in Table 1, the bulk of literature on neighborhood context and parenting examined the direct associations between one or more neighborhood context constructs, Neighborhood Disengagement, Disadvantage, or Danger, and positive parenting. Overall, the literature indicates the results are largely mixed in finding significant associations and/or the direction of the associations found to be significant. Study findings will be integrated and summarized here by neighborhood construct.

Neighborhood Danger

The current body of work indicates mixed results for the links between Neighborhood Danger and positive parenting style and behaviors. These studies reflect families with children across all age groups as well as income levels. Most studies indicate significant links; however, the direction of these associations varies. For example results from a number of studies examining low-income families indicate negative links between Neighborhood Danger and positive parenting style, warmth, and behavioral control (Chung and Steinberg 2006; Gayles et al. 2009; Gonzales et al. 2011; Pinderhughes et al. 2001; Tolan et al. 2003). This pattern of findings suggests that caregivers engage in lower levels of positive parenting style, warmth, and behavioral control when there are higher levels of Neighborhood Danger. Prior literature suggests that caregivers living in communities with higher levels of danger are experiencing chronic stressors (e.g., crime) that may impede their ability to engage in positive parenting behaviors (e.g., Hill and Herman-Stahl 2002; McLoyd 1990). Further, drawing from models such as Social Disorganization (Jencks and Mayer 1990) and literature indicating low-income and poor caregivers tend to be socially isolated (e.g., Ceballo and McLoyd 2002; Weinraub and Wolf 1983; Wilson 1987), perhaps to protect themselves and their families from potential harm, it could be that caregivers do not have the opportunity to observe and model positive parenting style, warm interactions with their children, or effective discipline strategies from other caregivers in their community.

Alternatively, other studies found positive associations between Neighborhood Danger and positive parenting style and behaviors such that caregivers engaged in higher levels of positive parenting, including both positive parenting style and maternal monitoring behavior in particular, in the context of greater Neighborhood Danger (Jones et al. 2005; Vieno et al. 2010). In other words, these studies suggest caregivers may ramp up, rather than experience a compromise in, their positive parenting to afford greater protection to their children in the context of the risks associated with Neighborhood Danger.

Still, other studies focusing on families across income levels found null associations between Neighborhood Danger and positive parenting style and behaviors (Dorsey and Forehand 2003; Gayles et al. 2009; Jones et al. 2003; Law and Barber 2006; Taylor 2000). For example, two studies did not find a link between Neighborhood Danger and behavioral control suggesting there may not be an association between these two variables (Gayles et al. 2009; Taylor 2000). Null findings could also suggest there are third variables that need to be considered to fully understand how Neighborhood Danger may be related to parenting. As these inconsistent patterns of findings are consistent across neighborhood constructs, a later portion of this review will address potential reasons for mixed or null findings in the literature.

Neighborhood Disadvantage

Studies that have examined the link between Neighborhood Disadvantage and positive parenting style or positive parenting behaviors also reveal mixed results. This pattern is mostly observed in studies focused on understanding the link between Neighborhood Disadvantage and positive parenting style, caregiver warmth, or caregiver monitoring. Many of the studies found no significant associations for this neighborhood domain (Chuang et al. 2005; Gonzales et al. 2011; Rankin and Quane 2002; Tendulkar et al. 2010), suggesting perhaps the lack of institutional and economic resources in a community may not be related, at least directly, to positive parenting behavior or style.

Other studies, however, primarily those focusing on low-income families found negative associations between Neighborhood Disadvantage and parenting style, caregiver warmth, and/or monitoring (Klebanov et al. 1994; Liu et al. 2009; Pinderhughes et al. 2001; Taylor 2000). That is, caregivers engaged in lower levels of positive parenting style, warmth, and/or monitoring in the context of fewer institutional and economic resources in the surrounding community. Drawing upon Cumulative Risk Theory (Sameroff 2000), the culmination of additional stressors related to having limited financial resources, rather than the presence of any particular stressor (e.g., Neighborhood Disadvantage), may impede the ability for low-income caregivers in particular to engage in a positive parenting style or behaviors. These stressors could include higher prevalence of health-related problems (National Center for Health Statistics 2013), having to rely on public modes of transportation due to decreased access to automobiles (Blumenberg 2004), and working multiple shifts to make money to provide for their families (Hsueh and Yoshikawa 2007).

Alternatively, Chuang et al. (2005) observed a positive association, instead of a negative association, between Neighborhood Disadvantage and caregiver monitoring, albeit for middle-income caregivers. These results indicated middle-income caregivers engaged in higher levels of monitoring behaviors when there were higher levels of Disadvantage in the community. Related to the discussion of the findings for Neighborhood Danger, it may be that caregivers may feel increased motivation to engage in positive parenting behaviors to buffer against the lack of resources in their community (Gonzales et al. 2011; Maton and Rappaport 1984). Mixed findings for the direction of the link between Neighborhood Disadvantage and caregiver monitoring may be due to differences in family income levels across study samples. A more thorough discussion of this possibility is discussed in a later portion of this review.

Finally, three studies examined the link between Neighborhood Disadvantage and behavioral control in particular; however, the studies did not find a significant association between these two variables (Pinderhughes et al. 2001; Rankin and Quane 2002; Taylor 2000). As noted for Neighborhood Danger, these mixed results, ranging from positive to negative to null associations may indicate that additional factors may be important to consider when examining the link between Neighborhood Disadvantage and parenting, factors that will be considered later in this review.

Neighborhood Disengagement

Neighborhood Disengagement, primarily reported in research to date via subjective measurement, was negatively associated with an overall positive parenting style (e.g., Chung and Steinberg 2006; Dorsey and Forehand 2003; Vieno et al. 2010) for three of the four studies examining this link. These findings were consistent across family income level, ethnicity, and geographic location. That is, caregivers who reported higher levels of Neighborhood Disengagement scored lower on measures assessing a positive parenting style. Why the consistent link across studies between Neighborhood Disengagement and compromises in positive parenting? In the context of higher levels of Neighborhood Disengagement, caregivers may not form trusting relationships with other members of the community who could help to ameliorate some of the stressors that are associated with parenting responsibilities (i.e., Collective Socialization as discussed by Brody et al. 2001 and others). The lack of this social support or collective socialization in the neighborhood means that caregivers are expected to handle parenting duties on their own or find these resources outside of their community. In turn, caregivers may feel increased levels of distress, which may impede their ability to engage in positive parenting. Additionally, consistent with theories such as Social Disorganization and an Epidemic Model of Behavior (Jencks and Mayer 1990; Sampson 1992), higher levels of Neighborhood Disengagement may mean less guidance for engaging in positive parenting through decreased opportunities to model specific parenting behaviors and receiving parenting advice from other residents in the neighborhood.

What is less clear in the studies examining the link between Neighborhood Disengagement and parenting, however, is how this neighborhood domain is linked to individual positive parenting behaviors (caregiver warmth, monitoring, and behavioral control). This may be due, in part, to the relatively limited literature in this area, particularly relative to parenting style (see Table 1). Yet, this small body of work provides mixed findings. One study did not find a significant association between Neighborhood Disengagement and behavioral control (Gayles et al. 2009). Findings from another cross-sectional study examining low-to-middle income African American caregivers also noted null associations with behavioral control and warmth but a significant negative association between Neighborhood Disengagement and caregiver monitoring (Rankin and Quane 2002). Still another study found a negative association between Disengagement and caregiver warmth (Tendulkar et al. 2010). Consistent with study findings related to positive parenting style, some of this work suggests caregivers may engage in lower levels of warmth and monitoring behavior in the context of lower levels of positive social processes in the community; however, more research should focus on the overall contexts in which these associations could be present and when they are not, which is discussed later.

Summary

Taken together, the findings for the examinations of the links between neighborhood context and positive parenting style as well as specific behaviors is mixed. Studies examining Neighborhood Disadvantage and Danger indicated significant relationships between neighborhood constructs and parenting; however, the direction of these associations seemed to differ among studies. Other study findings found no significant links between neighborhood constructs and positive parenting, suggesting perhaps the associations are more complex and require the consideration of additional variable to understand how neighborhood context is related to positive parenting style and behaviors. The next section explores potential third variables and indirect associations that may help clarify these associations.

Moderators and Mediators of the Link between Neighborhood Context and Parenting

As alluded to several times in the previous section, the literature also highlights important additional variables to consider when examining the relationship between the neighborhood context and positive parenting. These variables can provide a moderating role in which the association between the neighborhood construct and positive parenting depends on the level of the third variable. The presence of a third variable can be associated with a mediated or indirect link between neighborhood and parenting as well.

Potential Moderators

Primarily, family income, youth age and youth/caregiver gender, as well as a second neighborhood context variable, emerged as potential moderators (e.g., Liu et al. 2009; Simons et al. 1996; Tendulkar et al. 2010). Although not always explicitly examined in the studies in this review, evidence suggesting the potential moderating roles of family income, youth age and youth gender will be discussed in this section. Findings regarding interactions between two neighborhood constructs and their associations with positive parenting style and behaviors will be explored in the following section.

Family Income

Findings provide preliminary data to suggest that the direction of some of the associations between neighborhood context and positive parenting style or behaviors depends on family income. Specifically, lower-income parents may exhibit lower levels of positive parenting style and behaviors in the context of higher levels of Neighborhood Danger and Disadvantage (Chung and Steinberg 2006; Tolan et al. 2003), but middle-income parents may exhibit higher levels of positive parenting in this context (Vieno et al. 2010). As such, whereas relatively higher income parents may have the capacity to ramp up their positive parenting in response to the presence of Neighborhood Danger and Disadvantage, there may be more constraints on the capacity for low-income caregivers to do the same as noted in the discussion of findings above.

Similar to the case with Disengagement, which was discussed in the section above, it is likely that low-income caregivers in neighborhoods with higher levels of Danger and Disadvantage have fewer opportunities to observe other residents in the community engaging in high levels of positive parenting behavior compared to middle-income caregivers. That is, building on Social Disorganization theory and Epidemic Models of behavior (Sampson 1992; Jencks and Mayer 1990), it may be that other residents in the neighborhood are also of lower socioeconomic status and are experiencing the same financial and economic stressors (e.g., working multiple shifts, experiencing health problems) that impede their ability to engage in a positive parenting style as well. As a result, there are fewer reinforcing models for positive parenting in the community. Due to the small body of work in this area, it would be helpful for future studies to examine the moderating role of family income in associations between neighborhood context and positive parenting to determine the nature of these associations.

Youth/Caregiver Gender

Most studies in this review included mixed gender samples of youth (see Tolan et al. 2003 for an exception); however, gender was not consistently examined as a possible factor related to the association between neighborhood context and parenting (e.g., Chung and Steinberg 2006; Kohen et al. 2008; Kotchick et al. 2005). In contrast, studies conducted by Simons et al. (1996) and Vieno et al. (2010) explored possible differences based on child gender. While Vieno et al. (2010) found no differences based on youth gender within their sample of mostly two-parent families, results from the study conducted by Simons et al. (1996) found that the relationship between neighborhood and parenting varied depending on the gender of the target child among single-mother families. Specifically, they examined they found a significant association between Neighborhood Disadvantage and caregiver positive parenting style for single mothers of male adolescents, but not for single mothers of female adolescents. Consistent with the explanation offered by the authors of this study, the opposing results based on youth gender may be attributed to the differences in the nature of the relationships single-mothers tend to have with their daughters compared to their sons. It was suggested that single mothers and their daughters are likely to form close relationships with each other as a way to support one another in coping with the hardships single-mother households typically face (e.g., financial concerns). It could very well be that relationships between single mothers and their daughters provide support that provides protection against the detrimental effects of living in a disadvantaged neighborhood.

In addition, the significant association between Neighborhood Disadvantage and a positive parenting style for caregivers of boys also highlights the difference of youth externalizing behaviors across gender in the context of highly disadvantaged neighborhoods. Prior work notes that male youth from single-mother households tend to engage in higher levels of externalizing problems (e.g., delinquency and aggression) compared to their female counterparts (Griffin et al. 2000; Thomas et al. 1996). This is particularly observed in disadvantaged neighborhoods (Zalot et al. 2007). These elevations of externalizing problems in male youth may stem from increased opportunities to affiliate with deviant peers in more disadvantaged neighborhoods, which would facilitate the development of problem behaviors such as delinquency and aggression (Griffin et al. 2000; Thomas et al. 1996). It is possible that single mothers living in highly disadvantaged neighborhoods find it difficult to engage in positive parenting behaviors (e.g., showing love and affection, spending time together) with their sons who are already exhibiting externalizing problems since they are likely already feeling higher levels of distress and have limited time and energy to devote to their children. Taken together, single mothers may be more vulnerable to feeling frustrated by their sons’ problem behavior, and since their sons may be more likely to exhibit problem behavior due to neighborhood influences, mothers may be less motivated to engage in warm and monitoring interactions with them. It is, of course, important to note the likely bidirectional association between these elevations in problem behavior and lower levels of warm interaction between mothers and sons. Therefore, it will be important for future research to further explore the moderating roles of not only youth gender, but the level of youth externalizing behavior within this context, which may be contributing to the observed gender difference in this association.

Other study findings suggested the association between Neighborhood Danger and specific parenting behaviors such as warmth and behavioral control may differ between mothers and fathers (Law and Barber 2006; White et al. 2009). These studies did not find significant associations between Neighborhood Danger and parenting behaviors for mothers; however, significant or marginal associations were found between Neighborhood Danger and warmth for fathers and one study indicated a significant association with behavioral control (White et al. 2009). Study findings suggest that perhaps mothers and fathers may approach their parenting differently based on the risks presented in their community. It may also be that mothers and fathers perceive these risks differently which would in turn, lead to differences in interactions and rule setting with their children. Based on the findings suggested by these studies, further research examining potential gender differences among caregivers could help clarify the link between neighborhood constructs and positive parenting behaviors.

Youth Age

Finally, a review of the studies included in this paper also highlights the potentially important, but understudied role of youth age in the association between neighborhood and parenting. Although age was surprisingly not directly examined as a moderator in any of the studies of neighborhood domain and parenting, it is certainly conceivable based on related and relevant literatures that the neighborhood context plays different roles in determining positive parenting approaches for caregivers with children across different age groups. It may be that certain parenting behaviors are more important at different stages of youth development. For example, studies in this review examining caregivers of children under 5 years of age tended to examine associations between neighborhood context and specific parenting behaviors of warmth and behavioral control (Klebanov et al. 1994; Kohen et al. 2008; Pinderhughes et al. 2001). Alternatively, studies focusing on caregivers of older children tended to focus on monitoring behaviors and reported their links to the three neighborhood domains (e.g., Chuang et al. 2005; Jones et al. 2003). This could be because older children progressively spend more time outside of the home, which may require a shift in parenting to monitor their youth’s activities.

Social Support

Another study conducted by Ceballo and McLoyd (2002) highlighted the importance of considering social support as a moderating variable in the link between neighborhood context and caregiver warmth. This study suggests that social support provided by individuals outside the home moderated the negative link between neighborhood quality (a construct simultaneously capturing elements of Neighborhood Danger and Disadvantage) and caregiver warmth. In other words, caregivers who lived neighborhood with low levels of neighborhood quality engaged in higher levels of warmth if they reported receiving higher levels of social support. In addition to the Family Stress Model, these findings are consistent with Jencks & Mayer’s Social Disorganization and Collective Socialization models in that social support may not just allow caregivers to be supported by individuals in the community to alleviate some of the stressors related to parenting but it may also increase the opportunity to observe and model positive parenting style and behaviors from those that that are providing the support.

Potential Mediators or Indirect Effects

Neighborhood constructs were also found to be indirectly associated with parenting through mediating variables such as caregiver psychological distress and family functioning, as well as other neighborhood constructs (although the mediating role of one neighborhood construct via another will be discussed in the next section) (Kohen et al. 2008; Kotchick et al. 2005; White et al. 2009). For example, findings from a study conducted by Kohen et al. (2008) suggest maternal depression and family functioning are positively related with Neighborhood Disadvantage such that as Disadvantage increases, maternal depression and negative family functioning also increases. In turn, caregivers may feel more distressed and lack energy to provide behavioral control. Findings from another study suggest that parental psychological distress fully mediates the negative link between Neighborhood Danger and positive parenting style as well (Kotchick et al. 2005).

While these two studies focused on links between neighborhood context and maternal positive parenting behaviors, one study examined paternal behaviors in relation to perceived Neighborhood Danger as well (White et al. 2009). This study found that paternal depression significantly mediated the association between Neighborhood Danger and paternal behavioral control and only marginally mediated the association between Danger and paternal warmth. Findings from the three studies examining indirect associations between neighborhood constructs and positive parenting are consistent with Ecological and Family Stress Models, highlighting the importance of considering more proximal stressors (e.g., caregiver psychological functioning, family functioning, caregiver depression) in understanding how the surrounding neighborhood and parenting may be linked.

Summary

Although this work should be considered preliminary due to the relative dearth of work in this area, findings on third variables suggest that the interrelationship of neighborhood context and positive parenting may vary depending on family income, as well as youth age and gender. Moreover, neighborhood context may operate through other family variables to influence positive parenting, particularly parental distress. One neighborhood construct may also operate through or in combination with another neighborhood construct in relation to positive parenting. This will be the focus of the next section.

Studies that Examined the Combined Association of Neighborhood Constructs on Positive Parenting

As noted earlier, the majority of work examined the direct and indirect associations of one or more unique neighborhood constructs (e.g., Chung and Steinberg 2006; Dorsey and Forehand 2003; Kohen et al. 2008) on positive parenting, while one study formed a latent neighborhood construct to examine the link between overall neighborhood context and caregiver warmth (Ceballo and McLoyd 2002). Still, others examined the potential moderating role of one neighborhood construct on the link between another neighborhood construct and positive parenting, as well as indirect associations between a particular neighborhood domain (e.g. Disadvantage) and parenting through the pathway of another neighborhood construct of interest (e.g., Danger, Disengagement). For example, both longitudinal and cross-sectional analyses examining low-income caregivers noted that greater Neighborhood Disadvantage was associated with higher levels of caregiver-reported Danger and Disengagement, which in turn, was linked to lower levels of positive parenting style (Chung and Steinberg 2006; Tolan et al. 2003). That is, caregivers living in Neighborhoods with higher levels of Disadvantage (defined by a combination of census tract data often including percentage of families living in poverty and percentage of single mother-headed families) were more likely to endorse higher levels of Neighborhood Danger and Disengagement, which in turn, resulted in lower levels of positive parenting behavior. These findings note how objective elements of the neighborhood (e.g., Neighborhood Disadvantage) can be linked with subjective components of the community (e.g., Neighborhood Danger and Disengagement) to influence parenting outcomes.

Apart from examining the indirect associations between neighborhood and parenting through another neighborhood domain, Neighborhood Disengagement was highlighted as a moderating variable between Danger and parenting behavior (e.g., Jones et al. 2005). Through cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses, Jones et al. (2005) found that the link between Neighborhood Danger and maternal monitoring was moderated by Neighborhood Disengagement, such that mothers from higher risk neighborhoods engaged in higher levels of monitoring behaviors when they felt lower levels of Neighborhood Disengagement (defined as lower levels of received social support from coparents and neighbors). As noted in the previous section, it may be that the social support caregivers receive from others could aid in preserving time and energy for engaging in higher levels of a positive parenting style which may be of particular importance for low-income caregivers who are already expending increased efforts in attaining resources for their families. Furthermore, this type of support may even take form of providing models for engaging in positive parenting behaviors (e.g., assisting in discipline practices or monitoring the child’s behavior by asking about the child’s activities).

Yet another study highlights the interactive relationship between perceived Neighborhood Disadvantage and Danger and their link between and caregiver warmth (Gonzales et al. 2011). In other words, mothers and fathers of Mexican-American youth engaged in the highest levels of warmth in the context of higher levels of Neighborhood Danger and Disadvantage. According to the study authors and prior discussions in this review, it could be that caregivers are more motivated to engage in positive parenting behaviors with their children to keep them safe and to buffer against the potentially negative influences in the surrounding community (Gonzales et al. 2011; Maton and Rappaport 1984). Taken together, these four studies highlight the ways in which the neighborhood domains discussed in this review not only have direct associations with positive parenting but can also influence each other to determine caregivers’ engagement in parenting behavior.

Discussion

The purpose of this review was to organize the existing literature on neighborhood context and positive parenting, utilizing proposed unifying neighborhood constructs, with particular attention to third variables that may begin to help to reconcile what may at first seem like largely contradictory findings across studies. Three over-arching neighborhood domains were suggested as a way of organizing the research linking neighborhood context to parenting behavior: Neighborhood Danger, Neighborhood Disadvantage, and Neighborhood Disengagement. A general “take home” message for this review could be that there is evidence for an association between neighborhood context and positive parenting (e.g., Jones et al. 2005; Pinderhughes et al. 2001; Simons et al. 1996), yet findings appear to vary, at least to some extent, depending on which neighborhood construct is examined (e.g., Chung and Steinberg 2006; Law and Barber 2006; Vieno et al. 2010), the way positive parenting is assessed (i.e., parenting style vs. parenting behavior vs. which parenting behavior) (e.g., Pinderhughes et al. 2001; Tolan et al. 2003), and the nature of the sample (e.g., family income) (e.g., Chuang et al. 2005; Liu et al. 2009; Vieno et al. 2010).

In turn, this review highlights how the impact of neighborhood on parenting may vary depending on other aspects of the family’s ecological system (i.e., moderators) and/or may operate indirectly through a third variable (i.e., mediation). This is further supported by the concept of multifinality within the developmental psychopathology framework, such that the presence or absence of these variables can lead to very different outcomes for individuals within the same neighborhood context (Cummings et al. 2002). As such, the consideration of these variables allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the link between neighborhood and parenting within the broader ecological system of the parent and family. These variables include demographic characteristics of the family (i.e., income) and child (i.e., age and gender), psychosocial characteristics of the caregiver and family (i.e., caregiver psychological well-being, family functioning) as well as the interrelationship of multiple domains of the neighborhood. Yet, potential limitations pertaining to methodological approaches also emerged, which may not only help to contextualize some of the inconsistent study findings, but also inform future research.

Study Design

Over half of the studies examined the association between neighborhood context and parenting style and/or behavior utilizing cross-sectional study designs (e.g., Gayles et al. 2009; Rankin and Quane 2002; Taylor 2000). Importantly, it is these cross-sectional studies that yielded the most inconsistent findings across the proposed neighborhood constructs and studies reviewed (e.g., Chuang et al. 2005; Chung and Steinberg 2006; Vieno et al. 2010). Further, the studies that did incorporate longitudinal designs, were limited to short-term longitudinal models (e.g., 1–3 years; Kotchick et al. 2005; Pinderhughes et al. 2001; Tolan et al. 2003). In order to understand the long-term associations and the effects of neighborhood factors on parenting practices, longitudinal studies with more assessments over time will be critical. For example, perhaps it is particularly important to understand the influence of neighborhood context during critical transitional developmental periods when parenting is known to be especially important and protective (e.g., middle childhood, adolescence) (e.g., Baumrind 1991; Combs-Ronto et al. 2009; Dishion et al. 1995). Moreover, it may be more chronic or cumulative exposure to the proposed neighborhood constructs that influence and modify parenting behavior, rather than snapshots of neighborhood characteristics either through subjective or objective measures at one particular point in time.

Measurement of Primary Study Constructs

Neighborhood constructs were, for the most part, measured similarly across studies in this review. The majority of the studies used multiple indicators and rating scales offering several possible responses to participants in order to examine each of the neighborhood constructs (e.g., Chuang et al. 2005; Liu et al. 2009; Simons et al. 1996). One study, however, exhibited a more limited approach to measurement (Pinderhughes et al. 2001). For example, this study that found a null association between Neighborhood Disengagement and both caregiver warmth and behavioral control used a measure to capture this neighborhood construct that consisted of only two items regarding social organization: (1) the frequency of informal socializing among residents in the neighborhood and (2) a binary report (yes/no) on the existence of formal community groups in the neighborhood (Pinderhughes et al. 2001). The variable used in this study differs from more comprehensive measures of Disengagement typically utilized in other studies in which two or more domains of Disengagement were reported on (e.g., composite of Level and Availability of Support, Social Control, Cohesion and Trust in the neighborhood: Dorsey and Forehand 2003). In turn, the variable may fail to adequately capture variability in this aspect of neighborhood context.

In addition to considering the elements that accurately reflect Neighborhood Disengagement, the literature also highlights the importance of capturing the types of Neighborhood Danger that are most relevant to neighborhood geographic location and family income level. Almost half of the studies that examined the link between parenting and Neighborhood Danger included low-income families living in rural areas (e.g., Jones et al. 2003; Law and Barber 2006; Pinderhughes et al. 2001). The measures used to examine the level of Neighborhood Danger within these communities, however, included elements that are more likely to be present in urban, underprivileged neighborhoods (e.g., graffiti, burglaries), rather than in rural communities, even if the rural communities are lower income. As such, research on Neighborhood Danger in rural areas would benefit from assessing specific aspects of danger more common to such areas, such as drowning in unsecured water sources (e.g., ponds, ditches, and canals), proximity to hunting areas which increase exposure to guns and gunshots, farm equipment hazards, vehicle accidents due to poor road conditions, injury due to lower levels of seat belt use and/or riding in the beds of pick-up trucks (e.g., Moore et al. 2010; National Safe Kids Campaign 2004). Alternatively, parents in higher income, suburban neighborhoods may deal with more acute, rather than chronic, danger (e.g., random house or car break-ins). This also includes increased opportunity for dangers afforded by wealth, such as youth access to alcohol and illegal substances, which have been shown to be associated with more adjustment difficulties among higher income youth (Luthar and Latendresse 2005; Melotti et al. 2011) and increased access to technology based modes of communication, such as texting and social networking sites, which pose greater risks for poorer adolescent outcomes (e.g., alcohol use, risky sexual behavior, suicidal ideation; Frank et al. 2010).

Such recommendations with regard to the measurement of Neighborhood Danger, in particular, however, are made with the caveat that boundaries between low and high danger areas may be blurred by proximity in urban areas which would in turn, make it difficult to separate and measure high- and low-income living spaces. This is particularly true in a study conducted by Vieno et al. (2010) such that their sample included families with higher incomes residing in an urban area where a range of levels of safety was likely represented. While higher-income caregivers may themselves reside in very low danger areas in the city, their homes may be in relatively close proximity to higher crime areas and this awareness may also prompt a ramping up of positive parenting. Future studies should take these factors into account when they are interpreting findings for urban-based higher income caregivers in particular.

Measurement considerations should also be taken with the assessment of parenting behavior in studies of neighborhood and parenting. Currently, a large portion of the literature focuses on one or more of the proposed neighborhood constructs and parenting style (e.g., Chung and Steinberg 2006; Simons et al. 2004; Tolan et al. 2003), while less is known about the specific associations between each of the neighborhood domains and specific positive parenting behaviors. This gap in the literature is due, in part, to fewer studies focused on examining these associations. It is also the case, however, that the findings of studies examining parenting behavior as the outcome were less consistent than those examining overall parenting style (e.g., refs). In part, such inconsistencies could be due to other aspects of measurement in these studies, including the way in which the information about parenting is achieved. Studies in this review commonly used caregiver- or youth-report on multiple measures to form a composite measure of parenting style (e.g., Chung and Steinberg 2006; Kotchick et al. 2005). Other studies that examined the relationships between neighborhood domains and specific parenting behaviors typically used observational or caregiver-reported measures that examined each of the parenting behaviors individually (e.g., Gayles et al. 2009; Klebanov et al. 1994). Although these measures are considered valid and reliable, attention must be given to how the information obtained may vary depending on reporter. For example, the studies in this review that asked youth to report on caregiver parenting behaviors observed non-significant findings between neighborhood and parenting (Law and Barber 2006; Rankin and Quane, 2002). Prior literature noted that these reports may not be accurate depictions of the actual parenting behavior caregivers are engaging in for a number of reasons (see Taber 2010 for a review). For example, youth have more difficulty in accurately reporting on more subjective concepts of parenting from the parent’s perspective (e.g., whether the caregiver enjoys joint activities with child, the caregiver knowledge about the child’s activities). Furthermore, many of the measures used to gather information from child reports include items that inquire about both objective and subjective aspects of parenting which makes it more difficult to ascertain the accuracy of the child-reported parenting behavior (Taber 2010).

Alternatively, it could also be the case that caregivers’ report on both neighborhood context and parenting behaviors inflates the link between the two constructs; however, others contend that caregiver reports on neighborhood context are actually better markers because the neighborhood factors to which a child is exposed depend on what the caregiver allows the child to experience (e.g., Simons et al. 2004). Indeed, studies in this review often included maternal reports of neighborhood context and parenting behaviors. This could be because the studies were specifically examining maternal parenting practices in their projects or, it was most often the caregiver who participated in the study. Since studies tended to gather data from primary caregivers, few included paternal or other caregiver responses (e.g., Vieno et al. 2010; Chuang et al. 2005) and only three sought to collect data on both maternal and paternal parenting practices (Gonzales et al. 2011; Law and Barber 2006, White et al. 2009). Many of the studies included a high number of single parent homes; however, prior research has indicated that single parents often have the assistance other adults who assist with childrearing (e.g., Jones et al. 2005). Could it be that neighborhood context is uniquely or differently associated with fathers’ parenting practices or other coparents’ parenting? Such issues speak not only to inflation of the potential for significant findings in studies that utilize mother reports of both neighborhood and parenting, but also the generalizability of findings.

Generalizability of Findings

Upon examination of the studies in this review, there are a few commonly used methodological approaches that limit the ability to generalize the findings in the research. These approaches include a focus on samples consisting of caregivers of ethnic minority backgrounds and caregivers of older children, as well as a failure to report effect sizes for the associations between neighborhood and parenting and inconsistent use of control variables.

Ethnic minority families were over-represented in the studies in this review (e.g., Chuang et al. 2005; Gayles et al. 2009). This may be attributed to the overall focus of examining underprivileged populations in the examination of neighborhood context. Although the general findings of the review suggest that similar trends in findings would hold true for Caucasian caregivers, it would be important for future research to extend the examination of link between neighborhood context and parenting to include more Caucasian samples. These studies would then be able to better tease apart the patterns of associations that are due to other variables, mainly family income, that are typically confounded with ethnicity.

The majority of the studies in this review also examined caregivers of pre-adolescent and adolescent youth (see Klebanov et al. 1994; Kohen et al. 2008; Pinderhughes et al. 2001 for exceptions). In turn, less is known about the link between neighborhood and parenting for caregivers of younger children, particularly those less than 7 years of age. This is particularly important to note as caregivers of young children may have fewer opportunities to interact with the greater community compared to other caregivers of older children who have more opportunities to get involved in school and community activities (e.g., community athletic teams, church youth groups, youth music groups) (Mahoney and Eccles 2008). In turn, caregivers of young children may have less exposure to models of positive parenting behavior as well as fewer opportunities to receive social support from other members of the community regarding parenting. This is consistent with the theory of Social Disorganization and the models of Collective Socialization that emphasize the role of social control within a community in determining individual behavior such as positive parenting. While the trends in the current work suggest the same associations between neighborhood Disengagement and parenting should be similar for caregivers with younger children, understanding the level of disengagement amongst this particular caregiver group would be important to explore as it could help identify important areas of early intervention behavioral training programs to increase positive parenting behavior.

Clinical Implications

Parenting is a primary focus of family-based programs targeting youth adjustment, yet relatively little is understood about how parenting style in general or specific parenting behaviors evolve within the context in which families live and interact. The findings of this review suggest that the neighborhood context, defined as Neighborhood Danger, Disadvantage, and Disengagement, likely shapes parenting, at least to some extent; however, clarifying the specific nature of these associations depends on further work as discussed above. That said, the current state of the literature suggests that family-focused, parenting interventions may benefit from contextualizing the content and process of intervention programming. This is achieved by considering the neighborhood context in which the caregiver resides and will be applying the parenting skills that are taught (McMahon and Wells 1998). For example, two existing programs, Family Growth Center and Family Connections, developed program components in which they provided community events to foster social support amongst families living in high-risk communities in addition to providing individualized parent training services to develop positive parenting practices (Akers and Mince 2008; DePanfilis and Dubowitz 2005). Research conducted on these programs indicate that the incorporation of these components contribute to overall positive family, parent, and youth adjustment. These findings provide preliminary support for the added value of tailoring parent-based programming particularly focused on Neighborhood Disadvantage. Other research suggests the potential clinical utility of interventions that contextualize parenting within the construct of Neighborhood Disengagement as well. For example, interventions founded upon principles of peer education and peer-led intervention groups have been successful in parent-focused intervention approaches targeting youth outcomes (Miller-Johnson and Costanzo 2004). Of course, concurrent lines of both basic and applied research examining the interrelationship of neighborhood context and parenting is ideal. Such future work must continue if this literature is to make a substantive contribution to our understanding of family functioning or family-focused intervention programming.

References

Akers, D. D., & Mince, J. (2008). Family growth center: A community-based social support program for teen mothers and their families. In T. A. Benner (Ed.), Model programs for adolescent sexual health: Evidence-based HIV, STI, and pregnancy prevention interventions (pp. 143–154). New York, NY: Springer.

Alba, R. D., Logan, J. R., Marzan, G., Stults, B. J., & Zhang, W. (1999). Immigrant groups in the suburbs: A reexamination of suburbanization and spatial assimilation. American Sociological Review, 64(3), 446–460.

Al-Hassan, S. (2009). Evaluation of the better parenting programme. Amman: UNICEF.

Bass, J. K., & Lambert, S. F. (2004). Urban adolescents’ perceptions of their neighborhoods: An examination of spatial dependence. Journal of Community Psychology, 32(3), 277–293. doi:10.1002/jcop.20005.

Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative control on child behavior. Child Development, 37(4), 887–907. doi:10.2307/1126611.

Baumrind, D. (1991). Effective parenting during the early adolescent transition. Family transitions, 111-163.

Blumenberg, E. (2004). Engendering effective planning—Spatial mismatch, low-income women, and transportation policy. Journal of the American Planning Association, 70(3), 269–281. doi:10.1080/01944360408976378.

Brody, G. H., & Flor, D. L. (1998). Maternal resources, parenting practices, and child competence in rural, single-parent African American families. Child Development, 69(3), 803–816. doi:10.2307/1132205.

Brody, G. H., Ge, X., Conger, R., Gibbons, F. X., McBride Murry, V., Gerrard, M., et al. (2001). The influence of neighborhood disadvantage, collective socialization, and parenting on African American children’s affiliation with deviant peers. Child Development, 72(4), 1231–1246. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00344.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. American Psychologist, 34(10), 844–850.

Caron, A., Weiss, B., Harris, V., & Catron, T. (2006). Parenting behavior dimensions and child psychopathology: Specificity, task dependency, and interactive relations. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35(1), 34–45. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_4.

Caughy, M. O., O’Campo, P. J., & Patterson, J. (2001). A brief observational measure for urban neighborhoods. Health & Place, 7(3), 225–236.

Ceballo, R., & McLoyd, V. C. (2002). Social support and parenting in poor, dangerous neighborhoods. Child Development, 73(4), 1310–1321. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00473.

Charles, C. (2003). The dynamics of racial residential segregation. Annual Review of Sociology, 29(1), 167–207.

Chuang, Y., Ennett, S. T., Bauman, K. E., & Foshee, V. A. (2005). Neighborhood influences on adolescent cigarette and alcohol use: Mediating effects through parent and peer behaviors. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46(2), 187–204. doi:10.1177/002214650504600205.

Chung, H. L., & Steinberg, L. (2006). Relations between neighborhood factors, parenting behaviors, peer deviance, and delinquency among serious juvenile offenders. Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 319–331. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.319.

Combs-Ronto, L. A., Olson, S. L., Lunkenheimer, E. S., & Sameroff, A. J. (2009). Interactions between maternal parenting and children’s early disruptive behavior: Bidirectional associations across the transition from preschool to school entry. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(8), 1151–1163. doi:10.1007/s10802-009-9332-2.

Conger, K. J., Rueter, M. A., & Conger, R. D. (2000). The role of economic pressure in the lives of parents and their adolescents: The family stress model. In R. K. Silbereisen (Ed.), Negotiating adolescence in times of social change (pp. 201–223). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Crouter, A. C., & Head, M. R. (2002). Parental monitoring and knowledge of children. In M. H. Bornstein & M. H. Bornstein (Eds.), Handbook of parenting: Being and becoming a parent (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 461–483). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cummings, E. M., Davies, P. T., & Campbell, S. B. (2002). Developmental psychopathology and family process: Theory, research, and clinical implications. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(7), 886.

De Marco, A., & De Marco, M. (2010). Conceptualization and measurement of the neighborhood in rural settings: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Community Psychology, 38(1), 99–114. doi:10.1002/jcop.20354.

DePanfilis, D., & Dubowitz, H. (2005). Family connections: A program for preventing child neglect. Child Maltreatment, 10(2), 108–123. doi:10.1177/1077559505275252.

DiBartolo, P., & Helt, M. (2007). Theoretical models of affectionate versus affectionless control in anxious families: A critical examination based on observations of parent–child interactions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 10(3), 253–274. doi:10.1007/s10567-007-0017-5.

Dishion, T. J., Capaldi, D., Spracklen, K. M., & Li, F. (1995). Peer ecology of male adolescent drug use. Development and Psychopathology, 7(4), 803–824. doi:10.1017/S0954579400006854.

Dorsey, S., & Forehand, R. (2003). The relation of social capital to child psychosocial adjustment difficulties: The role of positive parenting and neighborhood dangerousness. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 25(1), 11–23. doi:10.1023/A:1022295802449.

Evans, G. W. (2004). The environment of childhood poverty. American Psychologist, 59(2), 77–92. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.77.

Frank, S., Dahler, L., Santurri, L. E., & Knight, K. (2010). Hyper-texting and hyper-networking pose new health risks for teens. Case Western Reserve School of Medicine, news release, November 9, 2010.

Gayles, J. G., Coatsworth, J. D., Pantin, H. M., & Szapocznik, J. (2009). Parenting and neighborhood predictors of youth problem behaviors within Hispanic families: The moderating role of family structure. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 31(3), 277–296. doi:10.1177/0739986309338891.

Gonzales, N. A., Coxe, S., Roosa, M. W., White, R. B., Knight, G. P., Zeiders, K. H., et al. (2011). Economic hardship, neighborhood context, and parenting: Prospective effects on Mexican-American adolescent’s mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47(1–2), 98–113. doi:10.1007/s10464-010-9366-1.

Griffin, K. W., Botvin, G. J., Scheier, L. M., Diaz, T., & Miller, N. L. (2000). Parenting practices as predictors of substance use, delinquency, and aggression among urban minority youth: Moderating effects of family structure and gender. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 14(2), 174–184. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.14.2.174.

Henggeler, S. W., & Sheidow, A. J. (2011). Empirically supported family-based treatments for conduct disorder and delinquency in adolescents. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 38(1), 38–50. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00244.x.

Hill, N. E., & Herman-Stahl, M. A. (2002). Neighborhood safety and social involvement: Associations with parenting behaviors and depressive symptoms among African-American and Euro-American mothers. Journal of Family Psychology, 16(2), 209–219. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.16.2.209.

Hsueh, J., & Yoshikawa, H. (2007). Working nonstandard schedules and variable shifts in low-income families: Associations with parental psychological well-being, family functioning, and child well-being. Developmental Psychology, 43(3), 620–632. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.620.

Jarrett, R. L. (1999). Successful parenting in high-risk neighborhoods. The Future of Children, 9(2), 45–50. doi:10.2307/1602704.

Jencks, C., & Mayer, E. (1990). The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighborhood. In L. E. Lynn Jr. & M. G. H. McGeary (Eds.), Inner-city poverty in the United States (pp. 111–186). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Jones, D. J., Forehand, R., Brody, G., & Armistead, L. (2002). Psychosocial adjustment of African American children in single-mother families: A test of three risk models. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(1), 105–115. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00105.x.

Jones, D. J., Forehand, R., Brody, G., & Armistead, L. (2003). Parental monitoring in African American, single mother-headed families: An ecological approach to the identification of predictors. Behavior Modification, 27(4), 435–457. doi:10.1177/0145445503255432.

Jones, D. J., Forehand, R., O’Connell, C., Armistead, L., & Brody, G. (2005). Mothers’ perceptions of neighborhood violence and mother-reported monitoring of african american children: An examination of the moderating role of perceived support. Behavior Therapy, 36(1), 25–34. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80051-6.

Klebanov, P. K., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Duncan, G. J. (1994). Does neighborhood and family poverty affect mothers’ parenting, mental health, and social support? Journal of Marriage and the Family, 56(2), 441–455. doi:10.2307/353111.

Kohen, D. E., Leventhal, T., Dahinten, V. S., & McIntosh, C. N. (2008). Neighborhood disadvantage: Pathways of effects for young children. Child Development, 79(1), 156–169. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01117.x.

Kotchick, B. A., Dorsey, S., & Heller, L. (2005). Predictors of parenting among African American single mothers: Personal and contextual factors. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(2), 448–460. doi:10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00127.x.

Law, J. H. J., & Barber, B. K. (2006). Neighborhood conditions, parenting, and adolescent functioning. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 14(4), 91–118. Retrieved from https://auth.lib.unc.edu/ezproxy_auth.php?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=flh&AN=MRB-GAN070830-009&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Leventhal, T., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2000). The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 309–337. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309.

Liu, L. L., Lau, A. S., Chen, A. C., Dinh, K. T., & Kim, S. Y. (2009). The influence of maternal acculturation, neighborhood disadvantage, and parenting on Chinese American adolescents’ conduct problems: Testing the segmented assimilation hypothesis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(5), 691–702. doi:10.1007/s10964-008-9275-x.

Luthar, S. S., & Latendresse, S. J. (2005). Comparable ‘risks’ at the socioeconomic status extremes: Preadolescents’ perceptions of parenting. Development and Psychopathology, 17(1), 207–230. doi:10.1017/S095457940505011X.

Mahoney, J., & Eccles, J. (2008). Organized activity participation for children from low- and middle-income families. In A. Booth, A. C. Crouter, A. Booth, & A. C. Crouter (Eds.), Disparities in school readiness: How families contribute to transitions in school (pp. 207–222). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Maton, K. I., & Rappaport, J. (1984). Empowerment in a religious setting: A multivariate investigation. In J. Rappaport & R. Hess (Eds.), Studies in empowerment: Steps toward understanding action (pp. 37–72). New York: Haworth.

McKee, L., Jones, D. J., Forehand, R., & Cuellar, J. (2013). Assessment of parenting style, parenting relationships, and other parent variables in child assessment. In Oxford handbook of psychological assessment of children and adolescents. New York: Oxford.

McLoyd, V. C. (1990). The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioeconomic development. Child Development, 61, 311–346.

McLoyd, V. C. (1998). Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist, 53(2), 185–204. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.53.2.185.

McMahon, R. J., & Wells, K. C. (1998). Conduct problems. In R. A. Barkley (Ed.), Treatment of childhood disorders (2nd ed., pp. 111–207). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Melotti, R., Heron, J., Hickman, M., Macleod, J., Araya, R., & Lewis, G. (2011). Adolescent alcohol and tobacco use and early socioeconomic position: The ALSPAC birth cohort. Pediatrics, 127(4), 948–955. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-3450.

Miller-Johnson, S., & Costanzo, P. (2004). If you can’t beat ‘em…induce them to join you: Peer-based interventions during adolescence. In J. B. Kupersmidt, K. A. Dodge, J. B. Kupersmidt, & K. A. Dodge (Eds.), Children’s peer relations: From development to intervention (pp. 209–222). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/10653-011.

Moore, J. B., Jilcott, S. B., Shores, K. A., Evenson, K. R., Brownson, R. C., & Novick, L. F. (2010). A qualitative examination of perceived barriers and facilitators of physical activity for urban and rural youth. Health Education Research, 25(2), 355–367. doi:10.1093/her/cyq004.

National Center for Health Statistics. (2013). Health, United States, 2012. With Special Feature on Emergency Care. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

National SAFE KIDS Campaign (NSKC). (2004). Rural injury fact sheet. Washington, DC: NSKC.

Nelson, D. A., Nelson, L. J., Hart, C. H., Yang, C., & Jin, S. (2006). Parenting and peer-group behavior in cultural context. In X. Chen, D. C. French, B. H. Schneider, X. Chen, D. C. French, & B. H. Schneider (Eds.), Peer relationships in cultural context (pp. 213–246). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511499739.010.