Abstract

Family processes and child development unfold in a physical context. Research suggests that housing quality, community services, and neighborhood characteristics shape parenting practices and child cognitive, emotional, and behavioral development. In the present chapter, main theoretical frameworks recognizing the influence of the environment on parenting and child development are presented. Among them, is the Ecological Systems Theory proposed by Urie Bronfenbrenner in 1979. Several empirical studies have also demonstrated that contextual factors, such as noise level, crowding, poverty levels, and residential stability, impact children and their families. In this chapter, this evidence is reviewed from a critical perspective, recognizing its strengths and limitations. The chapter finishes with a discussion on the directions for future research and the implications of current evidence for policy and practice. It is concluded that investing in the implementation of interventions to prompt adequate housing and positive networks in neighborhoods and communities is key for human development.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Human development unfolds in a physical environment. If this environment does not meet the necessary conditions, normal development is impeded. Children grow and spend the majority of their time in their house, and their social relations take place in a specific neighborhood and community. Although context influences development, effects are bidirectional and children also form and shape their context.

Bronfenbrenner (1979a) epitomizes the use of contextual frameworks to the study of child development and family processes. In his Ecological Systems Theory, he proposes that in order to understand human development, one must consider the entire ecological system in which growth occurs. Prior to Bronfenbrenner’s theory, developmental psychologists restricted the understanding of behavior to biological and psychological processes only within the individual. In Bronfenbrenner’s words, child psychology was a science of development-out-of-context (Bronfenbrenner, 1979b, p. 844), and researchers were studying variables that influence behavior in a decontextualized manner. For example, Belsky (1984) proposed one of the most often used models of parenting that considered the characteristics of the child (e.g., temperament), characteristics of the parent (e.g., psychological well-being), and characteristics of the family environment (e.g., stress and support) in the development of parenting practices. While this is considered a popular model among parenting researchers, it stopped short of including the broader social environment in which parents and children operate. Current models of parenting have extended their focus beyond factors in the family environment in order to consider how neighborhood or community impact the parent–child relationship. Researchers nowadays consider ecological factors, such as community context, socioeconomic status, neighborhood characteristics, and social support networks. Ten years after Belsky’s theoretical proposal, Luster and Okagaki (1993) provided a widely used model to conceptualize the ecology of parenting (Fig. 1).

Adaptation of the ecology of parenting by Luster and Okagaki (1993)

Wilson (1991) is one of the main authors emphasizing the critical importance of communities and systems external to the family in shaping parenting practices and child development. He specifically introduced neighborhoods as a topic for investigation, and his studies led to the development of the Chicago School of Sociologists. Wilson was one of the first to argue that families living in impoverished neighborhoods often struggle to protect their children and to promote positive development. Importantly, he proposed that poor neighborhoods stimulate family disorganization that leads to problematic child behavior.

The implications of considering the context in parenting and human development are profound. It involves shifting the focus from interventions directed specifically at the child, to broader programs considering various systems and their interaction. In particular, it has prompted a body of research examining the impact of housing quality, neighborhood characteristics and community systems on children’s behavioral and socio-emotional development. Although in the present chapter I specifically focus on environmental factors that affect child development and family processes, it is key to keep in mind that these environmental factors complement and interact with individual characteristics throughout the lifespan.

In this chapter, the main theoretical frameworks recognizing the influence of the environment on child and family processes are discussed, including Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979a). I then summarize research exploring the impact of housing, neighborhood quality and communities on child development and parenting practices. In terms of housing, I discuss studies exploring the impact of crowding, residential mobility and toxins/hazards on children’s academic, social, and emotional problems. Research on neighborhoods examines structural factors (such as poverty, residential instability, and ethnic heterogeneity), and their ability to promote neighborhood organization and maintain public order. Research on community factors, although related to neighborhood characteristics, focuses mainly on social support networks available to children and their families. In the final sections, the strengths and limitations of this research are discussed and the implications for policy and intervention are reviewed.

Theoretical Background

In developmental psychology, ecological models view the child and their family in the context of environments or ecological systems in which they reside—extended family, peer group, neighborhood, community, and institutions (such as the school or the workplace). The most widespread ecological model is that proposed by Bronfenbrenner (1979a), and known as the Ecological Systems Theory. According to this theory, human behavior takes place within a social context and mutual accommodation between organism and environment constantly occurs due to interactions between systems. The theory incorporates proximal settings in which the child directly interacts and more distal contexts that indirectly influence development, as well as the interactions between all the different systems.

The Ecological Systems Theory can be visualized as a set of various nested structures, each laid inside the other (see Fig. 2). The first structure known as the microsystem can be defined as the direct interpersonal relationships experienced by the person in a daily face-to-face setting. In other words, it is the direct environment in one person’s life. Most research on developmental psychology has focused on microsystems, such as the family and the school, and how these affect child behavior. The second system is the mesosystem defined as the relationships between the microsystems, such as the relations between home and school. A mesosystem is a system of microsystems. The third system is the exosystem , which includes links between two or more contexts, one that does not include the individual, but in which events occur that indirectly influence processes within the individual’s immediate setting. An example of an exosystem affecting child development is the parents’ workplace. Work-related stress has been associated with more hostile parenting practices (Repetti & Wood, 1997) and conflictive family relationships (Byron, 2005), both directly impacting the developing child. The macrosystem is the culture encompassing belief systems, bodies of knowledge, customs, heritage, lifestyles, and opportunity structures, all of which are embedded in each of the other systems. One aspect of the macrosystem commonly studied is socioeconomic status and how poverty impacts the developing child and family processes. Finally, the chronosystem refers to the passage of time and transitions over the life course, as well as sociohistorical changes. For example, changes in family structure, employment, and residence are all aspects of the chronosystem. Later in this chapter, I review empirical evidence suggesting that residential instability, an important factor that is part of the chronosystem, negatively affects child development and parenting.

Ecological systems theory by Bronfenbrenner (1979a)

Bronfenbrenner’s theory led to the development of other models that recognize the importance of the environment in shaping human development. For example, there are several theoretical frameworks intending to explain the impact of neighborhoods on child development, most of which come from the Chicago School of Sociologists. One of these is contagion theory , which focuses on the power of peer influences to spread problem behavior. Evidence suggests that children’s interactions with neighborhood peers are linked to increases in problem behavior, such as drug use, delinquency and violence (Brody et al., 2001). The rationale is that individuals in a confined geographical space are more likely to share common beliefs, attitudes and behaviors (Jencks & Mayer, 1989). Contagion theory proposes that peers transmit norms and ways of living. This influence process often occurs outside of awareness, or in other words, neighbors may not intend to influence others in their community but they engage in relationship behaviors that satisfy immediate needs for an audience or companionship, and these behaviors inadvertently influence others.

Another framework is the collective socialization model that focuses on the role of community adults and role models, beyond the family, in promoting negative and positive behaviors in children. According to this model, all of these forms of monitoring systems in neighborhoods impact child socialization. On the other hand, when thinking about the development of maladaptive behavior, social disorganization theory recognizes the importance of neighborhood structure in managing social problems (Shaw & McKay, 1942). Community social disorganization is conceptualized as the inability of a community structure to create common values among its residents and maintain effective social control. Social control is understood as the capacity of a social unit, in this case the neighborhood, to regulate itself according to desired principles and to attain collective goals (Janowitz, 1975). The main premise of social disorganization theory is that structural neighborhood factors (such as poverty, residential instability, and ethnic heterogeneity) could compromise local social ties and impede the control of crime and other problem behaviors within a neighborhood. This theory has been mainly used to explain crime and violence rates within neighborhoods.

Another important theoretical framework is the eco-bio-developmental model (Shonkoff, 2010), which proposes that human development is an interaction between biology and ecology, this last defined as the social and physical environment in which growth takes place. It incorporates a lifelong perspective paying particular attention to the first years of life and the exposure to toxic stress. At the biological level, it recognizes the interactions between genes and environment during sensitive periods and the physiological adaptations that take place over time. At the ecological level, it identifies the importance of policies, community programs and the need for stable and responsive relationships for healthy development.

A common theme across all of these theories is their recognition of contextual factors as crucial for shaping individual behaviors, including parenting practices. These frameworks allow us to understand parenting in the context of a neighborhood, a community, and a culture. They have led to the systematic study of environmental factors and its impact on family processes, which will be reviewed in the following section.

Evidence for Determinants of Parenting

In this section, a body of empirical evidence addressing various environmental factors and their impact on child development and parenting practices is discussed. I will start by reviewing housing characteristics, including structural factors (such as crowding and noise) and processes (such as residential mobility and homeownership). I will then review the evidence linking neighborhood and community characteristics with family processes.

Housing Characteristics

There is a body of literature examining the association between housing quality (i.e., physical adequacy and safety of the unit) and child development. Firstly, contamination due to mold and lead paint has been linked to poor respiratory health and neurological damage in young children (Leighton, Klitzman, Sedlar, Matte, & Cohen, 2003), and to greater school absenteeism (Shaw, 2004). Older housing has been associated with more accidents in children (Shenassa, Stubbendick, & Brown, 2004), and limitations on activity (Sharfstein, Sandel, Kahn, & Bauchner, 2001). Children that grow up in high-rise dwellings also show more behavioral problems and restricted play opportunities. They also tend to have less socially supportive relationships with neighbors (Evans, 2003). The relationship between housing quality and child development is mediated by family and parenting practices. Poor housing limits opportunities for stimulation and creates stress and conflict among family members. In addition, studies have found that parents are less responsive and harsher in poor housing conditions (Evans, Maxwell, & Hart, 1999).

Crowding , defined as the number of people per room, is another aspect of housing that has been widely studied. Early studies intending to explore its effects on human development randomly exposed children to different levels of density (e.g., Liddell & Kruger, 1987). They found that children under crowded conditions show higher levels of social withdrawal (Evans, Rhee, Forbes, Allen, & Lepore, 2000), and more behavioral problems (Drazen, 2015; Maxwell, 2003). Social withdrawal has been explained as a mechanism for coping with too much unwanted social interaction. Children in overcrowded homes show physiological markers of stress, such as elevated skin conductance (Evans, Lepore, Shejwal, & Palsane, 1998). They also show cognitive delays on standardized cognitive assessments and tend to fall behind in reading acquisition in comparison with their low-density counterparts (Goux & Maurin, 2005). Most explanatory processes linking crowding with developmental outcomes focus on parent–child relationships. Family interactions are more negative in high-density homes (Bartlett, 1998) and there are more reports of child maltreatment (Zuravin, 1986). Research suggests that parents are less responsive to young children in more crowded homes (Evans & Ricciuti, 2010), and show reduced parental monitoring (Supplee, Unikel, & Shaw, 2007). Importantly, there is evidence of elevated conflict and hostility among parents and children in crowded homes. Parents report greater irritability and more corporal punishment (Youssef, Attia, & Kamel, 1998). In addition, weaker social ties among family members have been found (Lepore, Evans, & Schneider, 1991).

Studies suggest that noise exposure also has detrimental effects on children’s cognitive development. For example, children exposed to airport noise in their house show delays in reading (Klatte, Bergström, & Lachmann, 2013). Chronic noise exposure also seems to affect long term memory and attention (Haines, Stansfeld, Job, Berglund, & Head, 2001; Matsui, Stansfeld, Haines, & Head, 2004). Importantly, noise might affect adults around children, who as a consequence provide less supportive and affectionate caregiving. For example, teachers in noisy schools report greater fatigue and less patience than their counterparts in quiet schools (Kristiansen et al., 2014), while parents in noisier and more chaotic homes are less responsive to their children (Corapci & Wachs, 2002).

Chaos is another housing variable that has been widely studied. It is defined as unpredictability and confusion in the home (Coldwell, Pike, & Dunn, 2006). Research has found that chaotic homes are associated with psychological distress in children (Evans, Gonnella, Marcynyszyn, Gentile, & Salpekar, 2005), worse academic outcomes (Petrill, Pike, Price, & Plomin, 2004), and more behavioral adjustment problems (Fisher & Shirley, 1998). As with other housing characteristics, chaos affects child development through family and self-regulatory pathways. Families in chaotic homes are less cohesive and have more conflict, while parents are less responsive (Valiente, Lemery-Chalfant, & Reiser, 2007). Research also suggests that children have more difficulty self-regulating (Hardaway, Wilson, Shaw, & Dishion, 2012), which might be a process leading to behavioral problems and distress.

Another well-studied aspect associated with housing is residential mobility . Research suggests that residential mobility has a negative impact on school achievement (Pribesh & Downey, 1999), especially in children from single-parent families. Moving also has a detrimental impact on behavioral and emotional adjustment of children (Adam & Chase-Lansdale, 2002; Anderson & Leventhal, 2016; Gasper, DeLuca, & Estacion, 2010), with one study finding that children who moved often tend to start sexual behavior earlier in life (Stack, 1994). The adverse effects of residential mobility on child development seem to be cumulative, with additional moves being increasingly more negative than one or two moves. Parenting quality is a strong moderator of this relationship, with more supportive parenting diminishing the impact of residential mobility on children’s adjustment (Hagan, MacMillan, & Wheaton, 1996).

Related to residential mobility is home ownership . Children that grow up in an owned rather than in a rented home tend to do better on a variety of outcomes. For instance, they show better health (Ortiz & Zimmerman, 2013), fewer behavioral problems (Boyle, 2002; Haurin, Parcel, & Haurin, 2000), higher achievement in school (Li, 2016), and lower school dropout rates (Aaronson, 1999). Haurin, Parcel, and Haurin (2002) found that owning a home rather than renting leads to a 13% to 23% better quality home environment and greater cognitive abilities in children, with reading achievement being up to 7% higher (Haurin et al., 2002). There are several explanations for why children of homeowners have better developmental outcomes. Firstly, homeowners are less mobile than those who rent, thus being able to establish support networks in a particular neighborhood and having greater stability (Dietz & Haurin, 2003). Second, it is possible they are better at maintaining their dwelling and thus the structural quality of their housing might be better. However, not all studies have found an association between home ownership and positive child outcomes, with some suggesting that the effects vanish after controlling for variables that affect both home ownership and family stability, such as residential stability (Barker & Miller, 2009; Galster, Marcotte, Mandell, Wolman, & Augustine, 2007).

Parenting practices seem to be an important mediating factor for most features of housing linked to child outcomes. Poor housing quality, overcrowding, noise, chaos, renting, and residential instability seem to affect the parent–child relationship and increase family conflict, leading to poorer child outcomes. Interventions to support parents might be particularly necessary for those struggling with decent housing conditions.

Neighborhood Characteristics

Families interact with neighbors and neighborhood services, and this is the unit where children receive social, health, and educational services. Children also develop a sense of belonging and safety in neighborhoods. There are several ways to define neighborhoods. Some studies use local knowledge of boundaries in cities, while others use health districts, police districts, school districts, or census information.

Theories describing the impact of neighborhood on child development often differentiate between those characteristics that are structural and those that have to do with their social organization. Structural characteristics most often studied are (1) income or neighborhood poverty levels; (2) racial/ethnic diversity; and (3) residential instability. Social organizational aspects include (1) social control; (2) social cohesion; and (3) collective efficacy.

Poverty levels or neighborhood income level could affect children and families in several ways. Firstly, they are strongly linked to the quality of public and private services, including schools, police protection and recreational areas. In accordance with the collective socialization model described in the previous section, neighborhood poverty levels also determine the type of available role models and monitoring systems for child behavior. For example, it has been suggested that deprived neighborhoods have a higher concentration of male joblessness and female-headed households, which might lead to social isolation and a shift in cultural norms and beliefs (Wilson, 1991). Some of these family cultural norms include a focus on the present rather than the future, poor planning and organization, little sense of personal control over events, and a lack of emphasis on school or job-related skills, all of which affect the parent–child relationship. Research shows that children that grow up in poorer neighborhoods have more internalizing and externalizing problems (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). This influence is more powerful during late childhood and early adolescence. Neighborhood deprivation also impacts children’s cognitive ability (McCulloch & Joshi, 2001), and is associated with higher rates of drop out from high school and teenage parenthood (Brooks-Gunn, Duncan, & Aber, 1997). These outcomes seem to be mediated by the physical environment at home and by parental responsiveness. There is also some evidence that living in a poorer neighborhood is associated with less maternal warmth toward the children and poorer quality of the home environment (Klebanov, Brooks-Gunn, & Duncan, 1994). In addition, families living in poor neighborhoods have to deal with a greater number of daily stressors which could weaken their psychological functioning and lead to impaired parenting behavior. Finally, living in impoverished neighborhoods has also been associated with more restrictive parenting practices and more control (Cleland et al., 2010). Although overprotection and control are often not considered effective parenting practices, they might be considered evolutionarily advantageous in neighborhoods with high levels of poverty and crime. It seems logical that parents prefer to closely manage where their children spend unsupervised time to minimize the risk of them being involved in crime or illegal activities (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000).

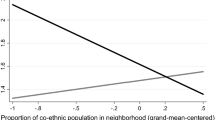

Racial/ethnic diversity is often measured as the proportion of immigrant residents in the neighborhood. Researchers propose that racial/ethnic diversity reduces contact and prevents interaction among groups of people coming from different ethnic backgrounds, and that this diminishes the capacity to build trust and implement strategies to keep the neighborhood safe and healthy (Browning & Cagney, 2002). Thus, racial/ethnic diversity is strongly related to a neighborhood’s social cohesion and prejudice. Sociologists propose that diverse social environments might induce a feeling of threat and anxiety between majority and minority groups, particularly arising out of real or perceived competition over scarce resources and relative positions in power (Pennant, 2005). For example, Alesina and Ferrara (2002) refer to a pattern they call natural aversion to heterogeneity, proposing that individuals prefer to interact with others who are similar to themselves in terms of income, race, or ethnicity. This pattern has to do with the dominant group fearing to lose economic and social privileges. Importantly, research suggests that those living in areas where there is lower concentration of ethnic/racial diversity are better off than those living in areas with a higher concentration (Lleras, 2017; Williams & Collins, 2001). Thus, poverty is another characteristic of highly diverse neighborhoods. Concentration of ethnic minorities in a neighborhood is often associated with health disadvantage for children and youth; specifically, they tend to show higher rates of depression. Some argue that worse psychosocial outcomes might be related to the stress of social stigma and a lack of social affiliations within the majority community (Pickett & Wilkinson, 2008). Moreover, racial/ethnic diversity is linked to governmental underinvestment, limiting the development of health, educational and recreational services in the neighborhood (Montalvo & Reynol-Querol, 2005; Williams & Collins, 2001).

Another neighborhood characteristic often studied is residential instability , which has to do with the proportion of residents who have moved within a certain number of years, the proportion of households who have lived in the same home for less than 10 years, or the proportion of homeowners. Higher levels of residential instability within a neighborhood have been linked to child maltreatment (Coulton, Korbin, Su, & Chow, 1995), alcohol and drug use in children (Ennett, Flewelling, Lindrooth, & Norton, 1997), and mental health difficulties in adolescents (Aneshensel & Sucoff, 1996). A potential pathway through which residential instability leads to poorer psychosocial outcomes has to do with social organization of neighborhoods. High rates of residential mobility might result in fewer social ties in a particular environment and less investment on collective projects to improve services. However, some studies have found the opposite and reported that residential instability might have positive health effects (Ross, Reynolds, & Geis, 2000). In a study by Drukker, Kaplan, and Os (2005), residential instability appeared to protect against the negative effects of neighborhood poverty and was beneficial to residents’ quality of life. In other words, families in poor neighborhoods could perceive residential stability as being trapped and powerless in a dangerous and frightening place.

In terms of organizational aspects of neighborhoods, social cohesion and social control have been widely studied, especially by the Chicago School of Sociologists. Social cohesion has been defined as the absence of social conflict and the presence of strong social bonds and mutual trust between neighbors (Putnam, 1993). Studies have reported the beneficial effects of social cohesion on parenting practices. For example, it has been suggested that perceptions of neighborhood cohesion are associated with less hostile parenting practices and fewer externalizing problems in children (Byrnes & Miller, 2012; Silk, Sessa, Morris, Steinberg, & Avenevoli, 2004). Interestingly, the relationship between social cohesion and child maltreatment has also been explored. It has been found that neighborhood social cohesion has a protective role in some acts of neglect such as in parents’ ability to meet the child’s basic needs (Maguire-Jack & Showalter, 2016). Increased access to social support might be why parenting practices are more effective in neighborhoods with high social cohesion. Neighborhoods with low social cohesion tend to have neighbors who are less likely to assist with childcare or engage in exchanges. Social disorganization theory, on the other hand, suggests that distressed neighborhoods with low cohesion might put parents at additional risk for maltreatment and ineffective parenting because of the multiple stressors surrounding them and the lack of social norms that encourage a supportive environment for positive parenting (Groves & Sampson, 1989).

Social control is another neighborhood characteristic often related to parenting practices. It refers to the norms of a community and the willingness to intervene when such norms are being violated. Parents might be more likely to avoid maltreating behaviors in neighborhoods with high levels of social control for fear of being accused and reprimanded. Garbarino and Crouter (1978) have extensively reviewed the ecology of child maltreatment, and have described how high-risk neighborhoods defined as those with more stressors, less support, and less control, can lead to social impoverishment and higher rates of maltreatment.

Collective efficacy is another organizational aspect of neighborhoods widely studied. The concept of collective efficacy links both social cohesion and social control. It is defined as social cohesion among neighbors, combined with shared values, mutual trust, and their willingness to intervene on behalf of the public good (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997). Collective efficacy is measured by summing scales that assess social cohesion and social control. Research suggests that higher collective efficacy in a neighborhood is associated with more authoritative parenting (Simons, Simons, Burt, Brody, & Cutrona, 2005). This makes sense, given that both collective efficacy and authoritative parenting incorporate elements of support with control or monitoring. Research also suggests that neighborhoods with higher collective efficacy have lower rates of externalizing difficulties in children and youth, such as criminal and antisocial behavior (Odgers et al., 2009). This can be partially explained by authoritative parenting which tends to be associated with better adjustment in children.

Collective efficacy has also been associated with psychological adjustment in children and lower rates of suicide (Maimon, Browning, & Brooks-Gunn, 2010). The reduced probability that youth will attempt suicide seems to be explained by the existence of social ties between parents and youth, and expectations for intergenerational support and supervision in neighborhoods with higher collective efficacy. Neighborhoods with high collective efficacy tend to reinforce family expectations and norms, which protect children and youth from mental health difficulties.

Research reviewed in this section focused on the interactive relationship between neighborhood characteristics and family processes, and how it impacts child development. Children are nested within families, and families are nested within neighborhoods that have organizational and structural aspects influencing micro-level processes. Any behavior should be seen from a multilevel lens considering the interactions between multiple systems. In the next section, research on communities, or in other words, social networks, and how they impact family processes and child development is reviewed.

Community Characteristics

There is a common premise in sociology that social units are more than the sum of their members. Social units involve a set of complex interactions that lead to the development of communities. While neighborhoods are defined by physical boundaries and tend to refer to structural environmental aspects, communities do not. They are often defined as a group of people who are related to each other in some way and have established support mechanisms. In other words, communities are networks of relationships. These networks often share culture, social norms and traditions. Cohesive and well-functioning local communities are the backbone of civil society. They exist at work, at school, in neighborhoods and among people with shared interests, and they can be understood along a number of different dimensions, such as size, proximity, stability, frequency of contact between members and density.

Communities that provide social support have consistently been found to be associated with positive outcomes in children and families. For example, mothers who have a close adult who supports them in raising young children report greater well-being and more effective parenting practices (Armstrong, Birnie-Lefcovitch, & Ungar, 2005). On the other hand, social isolation has been found to be a key feature of families in which child maltreatment occurs (Gracia & Musitu, 2003). Research suggests that neglectful parents tend to perceive their community as a non-supportive environment and isolate themselves from any type of social contact (Polansky, Gaudin, Ammons, & Davis, 1985). This social deprivation increases the risk of a deteriorated family environment, given that social networks and support provide an important protection from child maltreatment (Korbin, 1995). Individual or personality factors might explain social isolation in neglectful parents. For example, neglectful or abusive parents might avoid others given their troubled developmental history that taught them not to get too close to others for fear of being emotionally hurt. Also, they might have had few opportunities to develop social skills needed to be effective neighbors.

Parents living in poverty are likely to have fewer social, emotional and tangible sources of support. As stated by Wilson (1991), parents living in poor neighborhoods experience social isolation due to their lack of employment and the experience of community violence that have a detrimental impact on building social relationships. Thus, support networks may work differently for disadvantaged families. Some authors report that social support might be less effective for poor parents because of the number of stressors they face and the tendencies for other members in their networks to be experiencing similar stressful events (Ceballo & McLoyd, 2002). In other words, poor families might have social networks with fewer resources and without the necessary capacity to provide appropriate and effective support. Other authors suggest the opposite: that social support is even more important for families living in poverty (Taylor, Casten, & Flickinger, 1993). Kotchick, Dorsey, and Heller (2005) reported that social support buffered the impact of neighborhood stressors and psychological distress on parenting practices of African American single mothers living in poor neighborhoods. Izzo, Weiss, Shanahan, and Rodriguez-Brown (2000) reported similar findings in their study with Mexican immigrant parents in the US. Social support had a positive influence on parenting practices, and these effects were stronger for more stressed families.

In sum, having a supportive community seems to positively impact parenting. However, highly stressed and at-risk populations might benefit differently from social support. Chronic stress and lack of resources in their social networks might weaken the impact that support could have on parenting behavior. Conversely, in other families, ongoing stress may activate the need for social support, and this will have a positive impact on parenting practices. Regardless of the impact that support networks have on impoverished families, most studies are consistent in finding that socialization with neighbors is relatively uncommon in dangerous neighborhoods. In these neighborhoods, families tend to keep to themselves and monitor their children more closely.

Strengths and Limitations of the Evidence Base

Although there has been an increasing interest in understanding environmental factors that shape parenting behaviors and child development, this body of work is still scarce. As pointed out by Kotchick and Forehand (2002), there is evidence that contextual factors shape parenting, but more work needs to be done to identify how these variables interact together. In other words, it is difficult to disaggregate the effects of different community and neighborhood variables on family outcomes in order to establish what matters most. Importantly, a comprehensive model of parenting that includes the context (i.e., housing, communities and neighborhoods) is still needed in order to design interventions that target a broader range of influences.

There is little doubt that housing, neighborhoods and communities have a strong effect on parenting, family processes and child development, but more research is needed to understand the causal mechanisms that produce them, under which circumstances and where these effects are important. Simply put, one of the main challenges in this field of research is the identification of true causal effects. Most studies just show correlations between individual outcomes (i.e., parenting practices, family processes) and neighborhood characteristics.

Methodologically, most studies in this field are cross-sectional, thus it is difficult to establish how these variables relate across time, and whether one is a consequence of the other. The evidence in this field comes largely from non-experimental studies of non-representative samples of low-income families. Much of the research is descriptive and its generalizability is therefore unknown. In addition, many studies underestimate variation across and within neighborhoods, making wide assumptions in very complex presentations. That is to say, it is often assumed that poverty is homogeneously distributed across a neighborhood, when in reality neighborhoods are characterized by heterogeneous presentations and diverse levels of risk.

Although most studies exploring the impact of housing, neighborhoods and communities provide useful information, relatively little attention has been paid to the time frame necessary for these conditions to affect parenting and child development. To put it differently, exposure to adverse environmental conditions may need to accumulate over time to affect development, or might only affect development after a lag period. The relevant timeframe may differ for different outcomes. However, current studies are unable to explore these timeframes of exposure as they often explore effects cross-sectionally.

Another limitation widely recognized among scholars in the field is the selection bias, also known as the omitted variable bias. This refers to the fact that unmeasured characteristics associated with neighborhood residence might really account for observed neighborhood effects. For example, families that move into poor neighborhoods might differ in a variety of ways from those who, even though equally poor, make different choices. These differences could actually account for reported neighborhood effects, leading to an overestimation of these effects.

A final limitation in the field is that it is difficult to measure the impact of interventions directed at improving wider contexts such as neighborhoods and communities. Building strong communities takes considerable time and impacts might be visible after a whole generation. As some authors have suggested, it is easier to show that disorganized communities are not good for children than to demonstrate the opposite through evaluation of interventions (Samson, 2008). Intervention studies in communities and neighborhoods become more complicated when considering that families tend to move, making interactions and structural characteristics dynamic and changeable across time. Nevertheless, there are some experiments, such as the Moving to Opportunity Experiment in the US (Chetty, Hendren, & Katz, 2016; Raver, Blair, & Garrett-Peters, 2015) that allowed systematic observation of different environments on family processes. Results from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment consistently suggest that parenting practices are sensitive to the outer world, and that by improving this outer world it is possible to achieve better family and child outcomes (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2003).

Future Directions for Research

There are important questions in the field that remain unanswered. Firstly, it is key to explore the specific processes through which housing and neighborhood characteristics affect family processes. Most research has found associations between poor environmental conditions, inadequate parenting practices and suboptimal child development. However, the mechanisms or pathways through which poor housing and neighborhood conditions lead to these negative outcomes are unclear. Conceptual models of the specific processes are needed, as these models are crucial to developing operational hypotheses to be tested.

Future research should also aim to answer whether intentional changes in environmental conditions, such as housing and neighborhood, produce an effect on health and family processes. The ideal approach for answering this question is to conduct randomized controlled trials (RCTs). RCTs in this field are virtually nonexistent, except for one frequently cited example—Moving to Opportunities in the US (Chetty et al., 2016; Ludwig et al., 2013). However, in this RCT families were randomized to moving or not moving to non-poor areas and a neighborhood-level intervention was not directly examined. The main challenge for conducting RCTs in this field is the lack of a clear understanding of what the intervention should be. Designing housing and neighborhood interventions requires further elucidation into the processes and mechanisms through which these environmental factors affect the child and the family. Some authors have suggested that emotional dysregulation and negative emotions (such as frustration and irritability due to the myriad of hassles associated with substandard living conditions) are a potential mechanism that can be targeted through psychological interventions (Kim et al., 2013; Raver et al., 2015). Another underlying mechanism that could be targeted is stimulus overload and chaos through neighborhood redesign and reshaping initiatives. In sum, better theory is needed in order to design interventions and build a stronger research base.

In terms of measurement, there is a need to develop housing and neighborhood measures that are relevant to child development. Measurement of key dimensions varies widely across studies and some suggest the need to reach a consensus on the physical, financial, and psychological aspects of the home that should be included. Finally, it is important that longitudinal and cohort studies of children include reliable and valid measures of housing and neighborhood characteristics. Environmental and physical factors surrounding children and families should be measured more often and incorporated into future studies.

Implications for Policy and Practice

While some parenting programs consider the broader context by incorporating a population health framework, other programs operate as if families live in a vacuum, or in other words, as if they exist without social relationships beyond their immediate circle. Research suggests that macro-level systems, such as the neighborhood and the community, have a powerful impact on parenting practices and the way families relate. Thus, it is important to consider the broader context in which parenting occurs when designing and implementing parenting interventions.

It is clear from the research reviewed so far that housing, neighborhoods and communities contribute to the decisions parents make about how to raise their children. Interventions need to be developed taking into account this evidence. In terms of housing, public policies should focus on offering parents of young children the necessary stability to reduce psychological distress and coercive practices that put child development at risk. Importantly, research suggests that parents in poor neighborhoods tend to isolate from others and engage in more restrictive parenting practices. Interventions should focus on building community networks and reducing this sense of isolation, thus also contributing to increasing collective efficacy, social cohesion, and social control within a particular setting.

Governments should make consistent efforts to strengthen communities. This starts by investing in those local institutions that affect children the most: child care and school services, as well as after school programs. Importantly, community systems should identify those parents that are positive, capable role models and connect them with other parents who might be able to learn from their experience. Families should also be empowered to search for support and agitate for better services. If interventions to increase parental agency are targeted to leaders within a community it is possible to increase community agency through a snowballing effect. Housing design can facilitate or inhibit the formation and maintenance of support networks. Therefore, housing should include spaces to support informal contact with neighbors and adequate safe play spaces for children.

In sum, public policies so far have mainly focused on the design and implementation of micro-level interventions to support parents and provide them with the necessary skills for relating with their children. However, this relationship does not occur in isolation. The parent–child relationship is shaped by the context in which it occurs. For positive human development, it is key to implement interventions that prompt the development of support and community networks, and assist families in having adequate housing and living conditions.

Conclusions

Purely individual-based explanations for parenting and family processes are insufficient and fail to capture important contextual and social determinants. A body of research suggests that housing, neighborhoods and communities have an important effect on parenting practices and child development. Specifically, poor quality and unstable housing is associated with harsh and ineffective parenting practices which contribute to poorer cognitive, emotional, and behavioral outcomes for children. Neighborhood structural characteristics (such as high levels of poverty and ethnic diversity) lead to family isolation and fewer opportunities for social support, which in turns affects parents and children. Poor neighborhoods are also characterized by lower social control and less social cohesion. These organizational aspects of neighborhoods impact the development of community networks, which are important to prevent child maltreatment. Parents who have community support report less psychological stress and more effective parenting practices.

Research in this field is growing. Nevertheless, scholars still need to disentangle causal pathways through which these environmental factors impact family processes, and develop conceptual models that will allow the design of interventions. RCTs testing the effectiveness of macro-level interventions, such as the Moving to Opportunities Experiment in the US, are few. Although changing communities might take several generations, impact evaluations are needed in order to improve the lives of those living in suboptimal environmental conditions.

References

Aaronson, D. (1999). A note on the benefits of homeownership. Chicago, IL: Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Working paper series no. WP-99-23. Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/p/fip/fedhwp/wp-99-23.html

Adam, E. K., & Chase-Lansdale, P. L. (2002). Home sweet home(s): Parental separations, residential moves, and adjustment problems in low-income adolescent girls. Developmental Psychology, 38(5), 792–805. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.38.5.792

Alesina, A., & Ferrara, E. L. (2002). Who trusts others? Journal of Public Economics, 85(2), 207–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(01)00084-6

Anderson, S., & Leventhal, T. (2016). Residential mobility and adolescent achievement and behavior: Understanding timing and extent of mobility. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 27(2), 328–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12288

Aneshensel, C. S., & Sucoff, C. A. (1996). The neighborhood context of adolescent mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 37(4), 293–310. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137258

Armstrong, M. I., Birnie-Lefcovitch, S., & Ungar, M. T. (2005). Pathways between social support, family well being, quality of parenting, and child resilience: What we know. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 14(2), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-005-5054-4

Barker, D., & Miller, E. (2009). Homeownership and child welfare. Real Estate Economics, 37(2), 279–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6229.2009.00243.x

Bartlett, S. (1998). Does inadequate housing perpetuate children’s poverty? Childhood, 5(4), 403–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568298005004004

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55(1), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x

Boyle, M. H. (2002). Home ownership and the emotional and behavioral problems of children and youth. Child Development, 73(3), 883–892. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00445

Brody, G. H., Ge, X., Conger, R., Gibbons, F. X., Murry, V. M., Gerrard, M., & Simons, R. L. (2001). The influence of neighborhood disadvantage, collective socialization, and parenting on African American children’s affiliation with deviant peers. Child Development, 72(4), 1231–1246. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00344

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979a). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979b). Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. American Psychologist, 34(10), 844–850. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.844

Brooks-Gunn, J., Duncan, G. J., & Aber, J. L. (1997). Neighborhood poverty, volume 1: Context and consequences for children. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7758/9781610440844

Browning, C. R., & Cagney, K. A. (2002). Neighborhood structural disadvantage, collective efficacy, and self-rated physical health in an urban setting. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(4), 383–399. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090233

Byrnes, H. F., & Miller, B. A. (2012). The relationship between neighborhood characteristics and effective parenting behaviors: The role of social support. Journal of Family Issues, 33(1), 1658–1687. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X12437693

Byron, K. (2005). A meta-analytic review of work–family conflict and its antecedents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 169–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.08.009

Ceballo, R., & McLoyd, V. C. (2002). Social support and parenting in poor, dangerous neighborhoods. Child Development, 73(4), 1310–1321. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00473

Chetty, R., Hendren, N., & Katz, L. F. (2016). The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: New evidence from the Moving to Opportunity experiment. American Economic Review, 106(4), 855–902. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20150572

Cleland, V., Timperio, A., Salmon, J., Hume, C., Baur, L. A., & Crawford, D. (2010). Predictors of time spent outdoors among children: 5-Year longitudinal findings. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 64(5), 400–406. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2009.087460

Coldwell, J., Pike, A., & Dunn, J. (2006). Household chaos: Links with parenting and child behaviour. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 47(11), 1116–1122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01655.x

Corapci, F., & Wachs, T. D. (2002). Does parental mood or efficacy mediate the influence of environmental chaos upon parenting behavior? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 48(2), 182–201. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.2002.0006

Coulton, C. J., Korbin, J. E., Su, M., & Chow, J. (1995). Community level factors and child maltreatment rates. Child Development, 66(5), 1262–1276. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00934.x

Dietz, R. D., & Haurin, D. R. (2003). The social and private micro-level consequences of homeownership. Journal of Urban Economics, 54(3), 401–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0094-1190(03)00080-9

Drazen, Y. N. (2015). Child behavior and the home environment: Are crowding and doubling-up bad for kids? Presented at the Society for Social Work and Research 19th Annual Conference: The Social and Behavioral Importance of Increased Longevity, SSWR. Retrieved from https://sswr.confex.com/sswr/2015/webprogram/Paper23510.html

Drukker, M., Kaplan, C., & Os, J. V. (2005). Residential instability in socioeconomically deprived neighbourhoods, good or bad? Health and Place, 11(2), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.02.002

Ennett, S. T., Flewelling, R. L., Lindrooth, R. C., & Norton, E. C. (1997). School and neighborhood characteristics associated with school rates of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38(1), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.2307/2955361

Evans, G. W. (2003). A multimethodological analysis of cumulative risk and allostatic load among rural children. Developmental Psychology, 39(5), 924–933. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.39.5.924

Evans, G. W., & Ricciuti, A. (2010). Crowding and cognitive development: The mediating role of maternal responsiveness among 36-month-old children. Environment and Behavior, 42(1), 135–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916509333509

Evans, G. W., Gonnella, C., Marcynyszyn, L. A., Gentile, L., & Salpekar, N. (2005). The role of chaos in poverty and children’s socioemotional adjustment. Psychological Science, 16(7), 560–565. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01575.x

Evans, G. W., Lepore, S. J., Shejwal, B. R., & Palsane, M. N. (1998). Chronic residential crowding and children’s well-being: An ecological perspective. Child Development, 69(6), 1514–1523. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06174.x

Evans, G. W., Maxwell, L. E., & Hart, B. (1999). Parental language and verbal responsiveness to children in crowded homes. Developmental Psychology, 35(4), 1020–1023. https://doi.org/10.1037//0012-1649.35.4.1020

Evans, G. W., Rhee, E., Forbes, C., Allen, K., & Lepore, S. J. (2000). The meaning and efficacy of social withdrawal as a strategy for coping with chronic residential crowding. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 20(4), 335–342. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.1999.0174

Fisher, L., & Shirley, S. (1998). Familial antecedents of young adult health risk behavior: A longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology, 12(1), 66–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.12.1.66

Galster, G., Marcotte, D. E., Mandell, M., Wolman, H., & Augustine, N. (2007). The influence of neighborhood poverty during childhood on fertility, education, and earnings outcomes. Housing Studies, 22(5), 723–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030701474669

Garbarino, J., & Crouter, A. (1978). Defining the community context for parent-child relations: The correlates of child maltreatment. Child Development, 49(3), 604–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1978.tb02360.x

Gasper, J., DeLuca, S., & Estacion, A. (2010). Coming and going: Explaining the effects of residential and school mobility on adolescent delinquency. Social Science Research, 39(3), 459–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.08.009

Goux, D., & Maurin, E. (2005). The effect of overcrowded housing on children’s performance at school. Journal of Public Economics, 89(5–6), 797–819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.06.005

Gracia, E., & Musitu, G. (2003). Social isolation from communities and child maltreatment: A cross-cultural comparison. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27(2), 153–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00538-0

Groves, W. B., & Sampson, R. (1989). Community structure and crime: Testing social-disorganization theory. American Journal of Sociology, 94(4), 774–802. https://doi.org/10.1086/229068

Hagan, J., MacMillan, R., & Wheaton, B. (1996). New kid in town: Social capital and the life course effects of family migration on children. American Sociological Review, 61(3), 368–385. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096354

Haines, M. M., Stansfeld, S. A., Job, R. F., Berglund, B., & Head, J. (2001). Chronic aircraft noise exposure, stress responses, mental health and cognitive performance in school children. Psychological Medicine, 31(2), 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291701003282

Hardaway, C. R., Wilson, M. N., Shaw, D. S., & Dishion, T. J. (2012). Family functioning and externalizing behaviour among low-income children: Self-regulation as a mediator. Infant and Child Development, 21(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.765

Haurin, D. R., Parcel, T. L., & Haurin, R. J. (2000). The impact of home ownership on child outcomes. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network SSRN scholarly paper no. ID 218969. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=218969

Haurin, D. R., Parcel, T. L., & Haurin, R. J. (2002). Does homeownership affect child outcomes? Real Estate Economics, 30(4), 635–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6229.t01-2-00053

Izzo, C., Weiss, L., Shanahan, T., & Rodriguez-Brown, F. (2000). Parental self-efficacy and social support as predictors of parenting practices and children’s socioemotional adjustment in Mexican immigrant families. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community, 20(1–2), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1300/J005v20n01_13

Janowitz, M. (1975). Sociological theory and social control. American Journal of Sociology, 81(1), 82–108.

Jencks, C., & Mayer, S. E. (1989). The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighborhood: A review. Evanston, IL: Center for Urban Affairs and Policy Research, Northwestern University Retrieved from https://www.nap.edu/read/1539/chapter/6

Kim, P., Evans, G. W., Angstadt, M., Shaun Ho, S., Sripada, C. S., Swain, J. E., … Luan Phan, K. (2013). Effects of childhood poverty and chronic stress on emotion regulatory brain function in adulthood. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(46), 18442–18447. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1308240110

Klatte, M., Bergström, K., & Lachmann, T. (2013). Does noise affect learning? A short review on noise effects on cognitive performance in children. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 578. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00578

Klebanov, P. K., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Duncan, G. J. (1994). Does neighborhood and family poverty affect mothers’ parenting, mental health, and social support? Journal of Marriage and Family, 56(2), 441–455. https://doi.org/10.2307/353111

Korbin, J. E. (1995). Social networks and family violence in cross-cultural perspective. In G. B. Melton (Ed.), The individual, the family, and social good: Personal fulfillment in times of change (Vol. 42, pp. 107–134). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Kotchick, B. A., Dorsey, S., & Heller, L. (2005). Predictors of parenting among African American single mothers: Personal and contextual factors. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(2), 448–460. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00127

Kotchick, B. A., & Forehand, R. (2002). Putting parenting in perspective: A discussion of the contextual factors that shape parenting practices. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 11(3), 255–269. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016863921662

Kristiansen, J., Lund, S. P., Persson, R., Shibuya, H., Nielsen, P. M., & Scholz, M. (2014). A study of classroom acoustics and school teachers’ noise exposure, voice load and speaking time during teaching, and the effects on vocal and mental fatigue development. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 87(8), 851–860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-014-0927-8

Leighton, J., Klitzman, S., Sedlar, S., Matte, T., & Cohen, N. L. (2003). The effect of lead-based paint hazard remediation on blood lead levels of lead poisoned children in New York City. Environmental Research, 92(3), 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0013-9351(03)00036-7

Lepore, S. J., Evans, G. W., & Schneider, M. L. (1991). Dynamic role of social support in the link between chronic stress and psychological distress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(6), 899–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0013-9351(03)00036-7

Leventhal, T., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2003). Moving to opportunity: An experimental study of neighborhood effects on mental health. American Journal of Public Health, 93(9), 1576–1582. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.9.1576

Leventhal, T., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2000). The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 309–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309

Li, L. H. (2016). Impacts of homeownership and residential stability on children’s academic performance in Hong Kong. Social Indicators Research, 126(2), 595–616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0915-8

Liddell, C., & Kruger, P. (1987). Activity and social behavior in a South African township nursery: Some effects of crowding. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 33(2), 195–211.

Lleras, C. (2017). Race, racial concentration, and the dynamics of educational inequality across urban and suburban schools. American Educational Research Journal, 45(4), 886–912. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831208316323

Ludwig, J., Duncan, G. J., Gennetian, L. A., Katz, L. F., Kessler, R. C., Kling, J. R., & Sanbonmatsu, L. (2013). Long-term neighborhood effects on low-income families: Evidence from moving to opportunity. American Economic Review, 103(3), 226–231. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1224648

Luster, T., & Okagaki, L. (1993). Multiple influences on parenting: Ecological and life-course perspectives. In T. Luster & L. Okagaki (Eds.), Parenting: An ecological perspective (pp. 227–250). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Maguire-Jack, K., & Showalter, K. (2016). The protective effect of neighborhood social cohesion in child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse and Neglect, 52, 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.12.011

Maimon, D., Browning, C. R., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2010). Collective efficacy, family attachment, and urban adolescent suicide attempts. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(3), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510377878

Matsui, T., Stansfeld, S., Haines, M., & Head, J. (2004). Children’s cognition and aircraft noise exposure at home: The West London schools study. Noise and Health, 7(25), 49–58 Retrieved from: http://www.noiseandhealth.org/text.asp?2004/7/25/49/31647

Maxwell, L. E. (2003). Home and school density effects on elementary school children: The role of spatial density. Environment and Behavior, 35(4), 566–578. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916503035004007

McCulloch, A., & Joshi, H. E. (2001). Neighbourhood and family influences on the cognitive ability of children in the British National Child Development Study. Social Science and Medicine (1982), 53(5), 579–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00362-2

Montalvo, J. G., & Reynol-Querol, M. (2005). Ethnic diversity and economic development. Journal of Development Economics, 76(2), 293–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2004.01.002

Odgers, C. L., Moffitt, T. E., Tach, L. M., Sampson, R. J., Taylor, A., Matthews, C. L., & Caspi, A. (2009). The protective effects of neighborhood collective efficacy on British children growing up in deprivation: A developmental analysis. Developmental Psychology, 45(4), 942–957. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016162

Ortiz, S. E., & Zimmerman, F. J. (2013). Race/ethnicity and the relationship between homeownership and health. American Journal of Public Health, 103(4), e122–e129. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300944

Pennant, R. (2005). Diversity, trust and community participation in England. London: Home Office.

Petrill, S. A., Pike, A., Price, T., & Plomin, R. (2004). Chaos in the home and socioeconomic status are associated with cognitive development in early childhood: Environmental mediators identified in a genetic design. Intelligence, 32(5), 445–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2004.06.010

Pickett, K. E., & Wilkinson, R. G. (2008). People like us: Ethnic group density effects on health. Ethnicity and Health, 13(4), 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557850701882928

Polansky, N. A., Gaudin, J. M., Ammons, P. W., & Davis, K. B. (1985). The psychological ecology of the neglectful mother. Child Abuse and Neglect, 9, 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(85)90019-5

Pribesh, S., & Downey, D. B. (1999). Why are residential and school moves associated with poor school performance? Demography, 36(4), 521–534. https://doi.org/10.2307/2648088

Putnam, R. (1993). The prosperous community. The American Prospect, 4(13), 35–42.

Raver, C. C., Blair, C., & Garrett-Peters, P. (2015). Poverty, household chaos, and interparental aggression predict children’s ability to recognize and modulate negative emotions. Development and Psychopathology, 27(3), 695–708. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579414000935

Repetti, R. L., & Wood, J. (1997). Effects of daily stress at work on mothers’ interactions with preschoolers. Journal of Family Psychology, 11(1), 90–108. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.11.1.90

Ross, C. E., Reynolds, J. R., & Geis, K. J. (2000). The contingent meaning of neighborhood stability for residents’ psychological wellbeing. American Sociological Review, 65(4), 581–597. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657384

Samson, R. J. (2008). Moving to inequality: Neighborhood effects and experiments meet structure. American Journal of Sociology, 114(11), 189–231. https://doi.org/10.1086/589843

Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 15(5328), 918–924. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.277.5328.918

Sharfstein, J., Sandel, M., Kahn, R., & Bauchner, H. (2001). Is child health at risk while families wait for housing vouchers? American Journal of Public Health, 91(8), 1191–1192. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.91.8.1191

Shaw, C. R., & McKay, H. D. (1942). Juvenile delinquency and urban areas (Vol. xxxii). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Shaw, M. (2004). Housing and public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 25(1), 397–418. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123036

Shenassa, E. D., Stubbendick, A., & Brown, M. J. (2004). Social disparities in housing and related pediatric injury: A multilevel study. American Journal of Public Health, 94(4), 633–639. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.4.633

Shonkoff, J. P. (2010). Building a new biodevelopmental framework to guide the future of early childhood policy. Child Development, 81(1), 357–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01399.x

Silk, J. S., Sessa, F. M., Morris, A. S., Steinberg, L., & Avenevoli, S. (2004). Neighbourhood cohesion as a buffer against hostile maternal parenting. Journal of Family Psychology, 18, 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.135

Simons, R. L., Simons, L. G., Burt, C. H., Brody, G. H., & Cutrona, C. (2005). Collective efficacy, authoritative parenting and delinquency: A longitudinal test of a model integrating community-and family-level processes. Criminology, 43(4), 989–1029. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2005.00031.x

Stack, S. (1994). The effect of geographic mobility on premarital sex. Journal of Marriage and Family, 56(1), 204–208. https://doi.org/10.2307/352714

Supplee, L. H., Unikel, E. B., & Shaw, D. S. (2007). Physical environmental adversity and the protective role of maternal monitoring in relation to early child conduct problems. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 28(2), 166–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2006.12.001

Taylor, R. D., Casten, R., & Flickinger, S. M. (1993). Influence of kinship social support on the parenting experiences and psychosocial adjustment of African-American adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 29(2), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.29.2.382

Valiente, C., Lemery-Chalfant, K., & Reiser, M. (2007). Pathways to problem behaviors: Chaotic homes, parent and child effortful control, and parenting. Social Development, 16(2), 249–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00383.x

Williams, D. R., & Collins, C. (2001). Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports, 116(5), 404–416. https://doi.org/10.1093/phr/116.5.404

Wilson, W. J. (1991). Studying inner-city social dislocations: The challenge of public agenda research: 1990 Presidential address. American Sociological Review, 56(1), 1–14.

Youssef, R. M., Attia, M. S.-E.-D., & Kamel, M. I. (1998). Children experiencing violence I: Parental use of corporal punishment. Child Abuse and Neglect, 22(10), 959–973. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(98)00077-5

Zuravin, S. J. (1986). Residential density and urban child maltreatment: An aggregate analysis. Journal of Family Violence, 1(4), 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00978275

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no disclosure.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Mejia, A. (2018). Communities, Neighborhoods, and Housing. In: Sanders, M., Morawska, A. (eds) Handbook of Parenting and Child Development Across the Lifespan . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94598-9_23

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94598-9_23

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-94597-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-94598-9

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)