Abstract

Affinity chromatography is one of the most common techniques employed at the industrial-scale for antibody purification. In particular, the purification of human immunoglobulin G (hIgG) has gained relevance with the immobilization of its natural binding counterpart—Staphylococcus aureus Protein A (SpA) or with the recent development of biomimetic affinity ligands, namely triazine-based ligands. These ligands have been developed in order to overcome economic and leaching issues associated to SpA. The most recent triazine-based ligand—TPN-BM, came up as an analogue of 2-(3-amino-phenol)-6-(4-amino-1-naphthol)-4-chloro-sym-triazine ligand also known as ligand 22/8 with improved physico-chemical properties and a greener synthetic route. This work intends to evaluate the potential of TPN-BM as an alternative affinity ligand towards antibody recognition and binding, namely IgG, at an atomic level, since it has already been tested, after immobilization onto chitosan-based monoliths and demonstrated interesting affinity behaviour for this purpose. Herein, combining automated molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations it was predicted that TPN-BM has high propensity to bind IgG through the same binding site found in the crystallographic structure of SpA_IgG complex, as well as theoretically predicted for ligand 22/8_IgG complex. Furthermore, it was found that TPN-BM established preferential interactions with aromatic residues at the Fab domain (Trp 50, Tyr 53, Tyr 98 and Trp 100), while in the Fc domain the main interactions are based on hydrogen bonds with pH sensitive residues at operational regime for binding and elution like histidines (His 460, His 464, His 466). Moreover, the pH dependence of TPN-BM_IgG complex formation was more evident for the Fc domain, where at pH 3 the protonation state and consequently the charge alteration of histidine residues located at the IgG binding site induced ligand detachment which explains the optimal elution condition at this pH observed experimentally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Antibodies (Ab) are the main drivers of the biopharmaceutical industry and their global market has grown exponentially due to the increasing applications in research, diagnostics and therapy [1, 2].

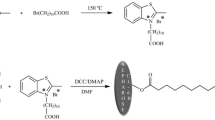

Therefore, effective Ab purification systems are needed to obtain high titers of pure Ab preparations as imposed by restricted legislation [3]. Since the most critical and expensive step of an Ab downstream process is the purification using natural SpA adsorbents, alternative solutions to improve economic and leaching issues associated to this process have been advanced [4]. Thus, over the last decades an extensive effort to develop alternative synthetic affinity ligands have been pursued which resulted in an improvement of chemical stability, and similar selectivity profile in comparison to the natural counterparts, at lower cost [5]. Affinity ligands based on triazine scaffold are interesting alternatives for Ab purification both at industrial and research levels, since they are inexpensive, chemically defined, nontoxic, resistant to both chemical and biological degradation, sterilizable and cleanable in situ [6]. Ligand 22/8 or 2-(3-amino-phenol)-6-(4-amino-1-naphthol)-4-chloro-sym-triazine is an example of such a synthetic ligand with potential for the purification of hIgG and monoclonal antibodies at research level from simple and complex mediums [5, 6]. When immobilized onto different chromatographic supports such as, agarose, [6] magnetic nanoparticles, [7] cellulose membranes [8] and chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol) (CP) monoliths, [9] ligand 22/8 exhibited great selectivity towards IgG purification. Moreover, after a theoretical evaluation through extensive molecular dynamics studies, ligand 22/8 revealed to be an excellent Protein A biomimetic ligand, regarding the similar molecular interactions found in this affinity pair, in comparison to the natural complex formed with Protein A [10–12]. Furthermore, the pH dependence that is required for the affinity chromatography elution was also rationalized for ligand 22/8 in complex with IgG. Despite its high performance for antibody purification, this ligand presents very low solubility in common solvents which makes it difficult to use, handling and accurate quantification. In order to overcome these limitations, an alternative synthetic ligand with improved solubility properties was designed and led to the synthesis of ligand 4-((4-chloro-6-(3-hydroxyphenoxy)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-oxy)-naphthalen-1-ol (TPN-BM), where the amino groups attached to the triazine core were switched by ether groups [13]. Moreover, this synthetic route modification was encouraged by the principles of green chemistry, which in recent years has been gradually adopted at industrial levels [14, 15]. Such a sustainable strategy minimizes inherent cost, atom waste, and the use of hazardous compounds and solvents during ligand production and process implementation. The new TPN-BM ligand has already shown an interesting selectivity profile for IgG purification when immobilized onto CP monoliths [13]. However, the molecular recognition and binding mechanism between TPN-BM and IgG affinity pair remains unveiled. Therefore, it is important to characterise the potential binding sites between the ligand and IgG, as well as to understand at atomic level the main intramolecular interactions responsible for the binding/unbinding molecular mechanism both at physiological (pH 7) and elution conditions (pH 3) [11]. Herein, based on previous experimental knowledge and for an easier comparison with Protein A and ligand 22/8, [10] automated molecular docking followed by MD simulations, [16] were performed with TPN-BM and human IgG fragments, Fab and Fc, at pH 7 and 3, in order to better understand the potential of this affinity pair for chromatographic purposes.

Methods

Molecular modelling

The Fab fragment (Chains L and H with 214 and 230 amino acids, respectively) and Fc fragment (Chains H and K with 239 and 236 amino acids, respectively), were retrieved from the crystallographic structure of human IgG, with the Protein Data Bank (PDB) code 1HZH, [17] and used as target proteins in this study. Ligand TPN-BM (4-((4-chloro-6-(3-hydroxyphenoxy)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-oxy)-naphthalen-1-ol) was used as the synthetic affinity ligand. The 4-chloro position of the triazine ring was substituted by a HN–CH3 moiety, to model the chemical effect of the spacer arm used experimentally for the immobilisation of the ligand on a solid support afterwards (Fig. 1).

Molecular docking

The Gasteiger partial charges and AutoDock atom types were automatically assigned to the receptor and ligand coordinate files through the AutoDock 4.2 python scripts. A blind docking using a grid map with 78 Å side (comprising 100 grid points in each orthogonal x, y and z axis, with a grid spacing of 0.78 Å), covering entirely the special volume occupied by each IgG fragment, was setup around the receptor’s centre of using the AutoDock 4.2 tool package [18]. A sigmoidal distance-dependent dielectric function was used for the dielectric continuum solvent with a constant value of −0.1465 by default [19]. A total of 256 independent solutions were evaluated during conformational search using a Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA) with the following parameters set: an initial population of 150 conformations, a maximum number of 2,500.000 energy evaluations, a maximum number of 27,000 generations, a mutation rate of 0.02, and a crossover rate of 0.8. Non-specified settings were assumed by default. A RMSD cutoff value of 2.0 Å was used in the automated cluster analysis. The total number of torsional degrees of freedom on the TPN-BM (TORSDOF) was 4. Docking results were interpreted taking into account two criteria: (i) energy criteria—the top-scoring docking solutions with the best estimated binding free energy were selected; (ii) geometry criteria—as the affinity ligands are used for purification purposes, docking solutions leading to ligand interactions in the target receptor inner cavities were discarded. Additionally, only solutions where the anchoring point of TPN-BM affinity ligand to the solid support was exposed to the solvent were selected, taking into account the constraints imposed by the solid support on the conformational space available for ligand to explore [20].

MD simulations

Molecular dynamics were performed using the GROMACS 4.5 simulation package [21] running in parallel on the in-house Sun Grid Engine (SGE) high performance computing cluster. The top-ranked docking solutions of ligand TPN-BM with Fab and Fc fragments of IgG were taken as starting structures for the MD simulation runs. Amino acids protonated state was adjusted according to their pKa values, at specific pH condition. The topology and force field parameterisation of the ligand TPN-BM were derived from the Dundee PRODRG web server (force field and topology parameters of the ligand are accessible in Supplementary Table S1) [22]. The TPN-BM_IgG complex was solvated in a truncated octahedral box with explicit SPC water model, keeping a buffer distance between the protein and the box edges of 12 Å due to the periodic boundary simulation conditions. The electro neutrality of the box was ensured by the addition of a correspondent number of Na+ or Cl− counter ions, depending on the global charge of the protein system (Table 1). The complex was simulated using the GROMOS 53A6 force field [23]. The simulation protocol comprised three phases: (1) potential atomic clashes were removed through a steepest descent minimisation algorithm in 2,000 steps followed by 1,000 steps using the conjugate gradient algorithm, (2) TPN-BM_IgG complex system was equilibrated in three consecutive steps of 100 ps each, reducing gradually the force constant for positional restraint of heavy atoms from 1,000, 100 to 10 kJ/mol and (3) total relaxation of the system during production phase. All simulations ran under periodic boundary conditions in an isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble, coupled to the Berendsen barostat with a reference pressure of 1.0 bar and a coupling time constant of 0.6 ps, [24] as well as to the V-rescale thermostat with a reference temperature 300 K and a coupling time constant of 0.1 ps [25]. A simulation time step of 2 fs was used. The LINKS algorithm was applied to constrain all H-bonds [26] and the electrostatic term was described by using the particle mesh Ewald algorithm for long-range electrostatics, as implemented in GROMACS software. Finally, in the production phase all atomic force constraints were removed and each system was simulated during 20 ns. The particle composition of MD simulation boxes are summarized in Table 1. The sequence numbering further referred to in this manuscript was based on the numbering of the crystallographic structure PDB code 1HZH. The visualisation software PyMol 1.2 [27] and VMD 1.9 [28] were used to generate the graphical artwork.

Results and discussion

The main interactions of SpA and ligand 22/8 with Fab and Fc fragments from human immunoglobulin G (hIgG) are very well studied in the literature [10–12]. It was found that SpA binds to hIgG at a consensus binding site (CBS) located in the hinge between the CH2 and CH3 regions of Fc domain and composed by the residues: Met 252, Ile 253, Gln 330, His 464, Asn 465, His 466 and Tyr 467, according to the 1HZH protein sequence numbering [12]. The binding site predicted for the interaction of ligand 22/8 with the Fc domain comprised the following amino acids: Leu 333, Asn 334, Gln 330, His 329, Glu 461, Ala 462, Leu 463, His 464, Asn 465 and His 466 which correspond to the CBS predicted for the biological interaction with SpA [10]. Moreover, also Zamolo et al. [20] found out a similar set of molecular interactions for the small biomimetic ligand—A2P. In this work, docking studies were firstly performed to evaluate preferential binding sites between ligand TPN-BM and IgG fragments separately and to estimate the binding free energy, as a first theoretical level assessment. The top-ranked docking solutions, e.g. the ones with the higher estimated binding free energy in module, were evaluated in terms of the population size of each cluster of solutions and filtered according to the geometrical constraints criteria defined for any potential protein binding site in the “Methods” section. The semiempirical force field implemented in Autodock4 to predict binding free energies of the complexes is based on a comprehensive thermodynamic model that takes into account the intramolecular energies by evaluating both the bound and unbound states into the prediction of the free energy of binding. Additionally, the force field has a satisfying formulation for the charge-based desolvation terms for all atoms without requiring any charges placement assumption [29]. It has successfully been calibrated on a diverse protein–ligand set of 188 complexes and docking results compared with correspondent experimentally derived structures and binding energies, showing a standard deviation of 2–3 kcal/mol for the estimated binding free energy in cross-validation theoretical studies [30]. Despite, a significant improvement in the accuracy of the calculated binding free energy from docking methodology, there is still considerable uncertainty derived from the approximations of the system in order to make it tractable, computationally speaking. These assumptions include (1) the implicit representation of solvent effect by a dielectric continuum; (2) the treatment of the protein receptor as a rigid-body; and (3) the truncation of the system in two independent IgG fragments that were treated separately in pure ideal conditions. These considerations might be taken into account for the comparison of docking predictions with experimental results, even when they are within the standard error of the method. In this respect, more accurate molecular mechanics methods like generalized Born surface area (MM/GBSA), Poisson Boltzmann surface area (MM/PBSA), or linear interaction energy (LIE) have been used to estimate the binding free energy between the native complex of SpA with IgG, [12] that might be considered in the future for the refinement of estimated binding free energy predicted here as a first proof-of-concept.

According to the selection criteria, the chosen docking solution were further investigated through MD simulations. Since the affinity purification of antibody fragments by adsorption/desorption mechanisms is known to be pH dependent, [11] the evaluation of ligand–protein interactions at the commonly used experimental conditions for chromatographic loading and elution of antibody (pH 7 and 3, respectively) was also simulated.

Interactions of ligand TPB-BM with IgG fragments

The top-ranked docking solution of ligand TPN-BM at the Fab domain of IgG presented an estimated binding free energy of −7.3 kcal mol−1 and a cluster population of 4 docking solutions. Additionally, the second and third top-ranked clusters with an estimated binding free energies ranging between −6.8 and −7.3 kcal mol−1 and with a significant population of 8 and 13 solutions each were also filtered and further analysed, according to energetic and geometrical criteria described in the “Methods” section. The remaining clusters were discarded because they exhibited either lower estimated binding energies or represented unreachable inner binding cavity solutions, which from a practical point of view could never take place in a real situation for an immobilized ligand onto a support. Remarkably, 3 out of 5 docking solutions showed a clear preference to interact with the Fab domain in a specific aromatic region located in the heavy chain H and establishing main interactions with residues: Trp 50, Tyr 53 and Tyr 98. The 3 similar cluster solutions reinforce the preference of ligand binding to Fab fragment, with a docking-derived associated affinity constant (K a ) of 2.1 × 105 M−1 (−7.1 kcal mol−1, average of estimated binding free energies). This value is in agreement with previous docking predictions, since it is within the range of the affinity constants theoretically predicted for SpA_Fab (4.6 × 107 M−1) and ligand 22/8_Fab systems (7.0 × 103 M−1) (Table 2) [10].

Regarding the docking of ligand TPN-BM at the Fc fragment, the maximum estimated binding free energy was −7.8 kcal mol−1. After applying the same filtering criteria as for Fab domain, only 4 out of 31 top-ranked docking cluster solutions were considered with estimated binding free energies of −6.8, −6.7, −6.7 and −6.7 kcal mol−1 with 7, 2, 3 and 1 elements, respectively. The first 2 cluster solutions were selected, considering the highest affinity constant of K a = 8.6 × 104 M−1 (Table 2). The K a obtained is one order of magnitude inferior when compared with the one estimated for Protein A and ligand 22/8, 8.1 × 105 and 1.5 × 105 M−1, respectively. However, a range 103–109 M−1 for K a corresponds to a median affinity value [31] thus, the estimated K a value obtained for the complex between Fc fragment and ligand TPN-BM is significant. Moreover, comparing theoretical and experimental K a ’s obtained for chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol) (CP) monolith functionalized with ligand TPN-BM (K a = 4.5 × 104 M−1) shown that values are in the same order of magnitude, even though these apparent agreement between theoretical predictions and experimental results might only be indicative of the quality of the affinity ligand for specific binding, due to the high biological complexity of a real chromatographic purification of a crude extract that is known to affect the separation process.

Therefore, an extensive MD characterization of predicted TPN-BM_IgG complexes over 120 ns was carried out. Then, the main intermolecular contributions for the affinity ligand binding were evaluated and quantified in order to understand better the recognition and binding mechanism behind.

From the MD simulations of TPN-BM_Fab complexes, it was notorious a high preference of ligand TPN-BM to bind to a narrow aromatic pocket defined by the side chains of Trp 50, Tyr 53, Tyr 98 and Trp 100 residues at the surface of heavy chain H. In fact, TPN-BM is stabilized by the π–π* stacking interaction established between the phenolic group of the ligand, and the side chains of Tyr 53 and Tyr 50, representing ca. 34 % of total simulation time. Furthermore, an H-bond interaction between OAW and OAV, oxygen atoms from the ligand and Tyr 53 hydroxyl group respectively, act as driving forces by positioning the ligand toward additional H-bond interactions. These interactions induce the repositioning of the ligand, which become entrapped by the naphtol ring between Trp100 and Tyr 98 through a typical π–π* stacking interaction, both with the two ligand substituents at the opposite side of the binding pocket, as depicted in Fig. 2. These interactions prevail during 24 % of the simulation time (Table 3). Moreover, Tyr 96, Tyr 91 and Trp 50 side chains also exhibit a considerable influence on the capture of TPN-BM by this hydrophobic binding site, considering a threshold distance of 5 Å between TPN-BM atoms and IgG residues as well as bellow 3 Å between heavy atoms for a strong interaction. The persistence of the main aromatic interactions that drive the complex formation between the ligand TPN-BM and Fab fragment, over the simulation time, are well supported by previous and independent theoretical studies [10–12].

Considering the dynamical behaviour of TPN-BM when complexed with the Fc fragment of IgG, two binding poses from docking were further evaluated through MD. The first one, in the CBS, was also reported by Branco et al. [10] and Huang et al. [12] located in the hinge region between the CH2 and CH3 domains of Fc fragment. The main CBS’s amino acids involved are His 460, His 464, Asn 465, His 466 and Tyr 467 (Fig. 3a). In bold are amino acids reported in the literature as anchoring points for the natural binding domain SpA, or affinity ligands as 22/8 or A2P to the Fc domain [10, 11, 20]. Particularly, Tyr 467 has a pivotal behaviour by anchoring the TPN-BM ligand and exposing it to a histidine rich environment (His 460, His 464, His 466), which will have a key role in the pH-dependent behaviour at elution conditions. The His 466 side chain establishes a close contact (≤5 Å distance) with the naphtol OAV group of the ligand during 80 % of the simulation time (Fig. 3b). Moreover, His 464 and His 460 side chains also have a significant contribution for the ligand binding at a short distance between 3 and 5 Å. Therefore, the CBS site for the Fc_TPN-BM system is maintained mostly by histidine residues. An alternative binding site to the CBS located in the heavy chain K was also investigated. The main residues involved in this binding site are His 302, Thr 306, Asn 303 and Lys 287 (Fig. 3a). However, His 302:HAZ and Thr 306:OAV at the naphtol side play the most important role to anchor the TPN-BM bound to the Fc domain during 24 and 56 % of the simulation time, respectively (see Table 2). Smaller contributions from Asn 303 (interaction during 5 % of the simulation time with OAZ from the naphtol ring) and Lys 287 (interaction during 10 % of the simulation time with OAW from the phenol ring) also contribute to the stabilization of the ligand (see Table 3).

pH dependence on the affinity between TPN-BM and IgG

The natural ligand SpA as well as the biomimetic affinity ligands 22/8 and A2P have shown a considerable pH dependence on IgG binding, both at experimental and theoretical levels. This dependence is of crucial importance for the capture and recovery of antibodies, as the elution process is trigger by a drastic change in the pH. In order to rationalize the experimental evidence that TPN-BM affinity ligand binds and elutes IgG efficiently at pH 7 and 3, respectively, MD simulations of the previously selected best docking complexes of TPN-BM with IgG fragments were simulated in parallel runs also at pH 3, for structural comparison.

Regarding the Fab domain, the key intermolecular interactions observed at pH 7 were conserved at pH 3, however with a weaker contribution, namely with the Trp 50, Tyr 53, Tyr 98 and Trp 100 residues (see Table 3). It is not surprising that the main interactions are still maintained at pH 3, since these amino acids have essentially an aromatic character and an invariant protonation state over the simulated pH range covered here between 7 and 3. Then, the adjustment of the ligand position at pH 3 only implied a slight decrease of interactions with Tyr 53, Tyr 98 and Trp 100 side chains and the formation of four new ones. These new interactions were established between OAW and OAV from the backbone of TPN-BM ligand and Asn 31 and Asn 34 of IgG, respectively, as well as the interaction between the OAZ atom from the naphtol ring and OAW from the phenol ring and Arg 106 and Leu 104 side chains of IgG, respectively, which account for 23–43 % of the total simulation time (see Table 3). These MD predictions highlighted the tendency of triazine-based ligands to be recognized preferentially by aromatic rich binding sites at the Fab domain, despite the fact that the precise location of the TPN-BM binding site does not coincide with the ones described previously for analogue ligands [10, 20]. The pH dependence results are consistent with the different amino acid nature of IgG fragment domains, since the amino acid composition of Fab binding site recognized by TPN-BM, in contrast to the His rich binding site found in Fc, is not sensitive to drastic changes in pH, in accordance with previous works [10–12]. In a marked contrast, the pH dependence of CBS at the Fc binding domain was found significant. At pH 3, the His and Glu residues at the CBS become protonated and the formal charge of the protein system and in particular at the Fc binding site increase, inducing the ligand to detach from the former tightly bound pocket as observed experimentally [13] (see Fig. 4). In MD trajectories simulated at pH 3, the ligand moved away from the Fc binding site (up to 8 Å displacement) and loosed interactions with IgG residues at the surface. The second TPN-BM binding site found at the Fc domain involved the His 302 and Thr 306 side chains which reduced the binding interaction in 3 and 15 % of simulation time at pH 3, respectively. However, special attention should be paid not only to the percentages of interactions in time, but mainly to the histidine profile at both pH’s (Fig. 5). At lower pH the ligand is still bound through the hydrophilic interaction of Thr 467, accounting for 56 % of the simulation time, however the tendency for the interaction disruption is notorious. At pH 3, the ligand moved away from a closer distance between 3 and 5 to 15 Å from the Fc domain along the simulation trajectory. These observations suggest that, the affinity of the TPN-BM ligand to the Fc domain become weaker at lower pH, which seems to be directly related to the highly His content surrounding the Fc binding site. Also, Branco et al. [10] found that for SpA_IgG and ligand 22/8_IgG systems the complex dissociation was reached at lower pH due to the repulsive interactions developed at the binding site. Another aspect that should be taken into account concerning the pH dependence rationalization was addressed by Huang et al. [11] on the influence of pH on the affinity of SpA_hIgG complex formation. It was concluded that SpA always binds the surface of hIgG during the simulation but slides slowly on the surface of hIgG and moves away from the binding site at pH 3. They understood, based on the calculation of binding free energies of electrostatic and non-polar interactions, that the dissociation at pH 3 is mainly driven by the electrostatic interactions, since the majority of SpA and IgG residues at pH 3 were positively charged, becoming favourable the electrostatic repulsion, as highlighted by our present results. Moreover, they also pointed out the important role of His 137 of SpA. They observed that His 137 contributed for a high association to IgG at pH 7 and to a high dissociation at pH 3 due to the charge of the residue at both pH. Herein a similar effect was observed between the imidazole rings from His and phenolic substituents of the ligand. Thus, we strongly believe that histidines present in Fc domain are the main responsible residues for the pH dependence of affinity ligand_IgG complexes in a more general view.

pH dependence of ligand binding to the Fc fragment of IgG (PDB code 1HZH). Protonation state of the protein residues adjusted to pH 7 (a) where the naphtol ring of the ligand is anchored within 5 Å to the polar and hydrogen bonding interaction with the Fc domain; and pH 3 (b), where main hydrogen bond interactions were disrupted forcing the ligand to drift away from the receptor (distances above 8 Å). Both regions of interactions are colored by hydrophobicity of the correspondent residues. (Software used: Pymol 1.3 and VMD 1.9.1)

Conclusions

Automated molecular docking coupled with MD simulations constitutes a powerful set of modelling tools to predict and evaluate the most energetically favourable binding modes of ligand TPN-BM to the Fab and Fc domains of IgG. The dynamical behaviour of the best docking hits were further characterized and compared with other SpA biomimetic analogues affinity systems, already described in the literature.

It should be noted that the predictability of the binding poses and correspondent binding free energy of a given complex formation is always limited by the accuracy of the semiempirical force field used for docking scoring and ranking, and by the model approximations considered in the methodological approach. Being aware of that, it was possible to explore the dynamical and binding behaviour of 3 putative binding sites on the Fab domain identified by a docking approach, with an estimated affinity constant in the range of K a ≅ 105 M−1. This value is comparable with previous theoretical predictions for the SpA_IgG complex (K a = 4.64 × 107 M−1), and also for the analogue ligand 22/8_IgG complex (K a = 7.00 × 103 M−1). Moreover, MD simulations shed some light on the mechanism of recognition and binding of the ligand TPN-BM with the Fab domain, mainly based on aromatic interactions, through amino acids Trp 50, Tyr 53, Tyr 98 and Trp 100. This cavity is similar in nature to the ones reported also for SpA_IgG and ligand 22/8-IgG complexes, despite the fact that these residues location does not coincide. Regarding the Fc domain, two top-ranked cluster solutions with a docking-estimated affinity constant of 8.60 × 104 M−1 were further investigated through MD. Interesting enough, the estimated affinity constant is in the same order of magnitude as to the one measured experimentally, using CP monoliths functionalized with TPN-BM which should be interpreted as a qualitative indicator of the binding capacity of the ligand and not as an absolute value, due to the modelling approximations of the simulated system. Conversely to the Fab fragment, in the Fc domain the TPN-BM preferentially binds in two histidine rich binding regions involving His 460, His 464, Asn 465 and His 466 residues. MD simulations suggest that the binding site found in the crystallographic structure of the systems SpA_IgG and in the simulations of the ligand 22/8-IgG complex, was also identified in the TPN-BM_IgG complex, which is localized at the hinge between CH2 and CH3 regions of Fc fragment and involving His 464, Asn 465 and His 466 as the key amino acid players.

Moreover, the pH dependence of TPN-BM_Fc complex was also tested at pH 3. Due to the high density of histidines at the Fc binding site, the on/off binding mechanism was supported by the simulation at lower pH conditions, which determined the protonation state of histidine and glutamic acid residues and consequently induced repulsive interactions between the ligand and the protein target upon an increase in the protein surface charge. This dynamical on/off binding behaviour shown by the TPN-BM_IgG complex help us to rationalize the required operating conditions during a binding/elution chromatographic purification process.

All the information presented in this work, seems to be in agreement with the obtained experimental data, involving the use of a “greener chromatographic approach” (TPB-BM ligand immobilized onto CP monoliths for IgG purification), and help us to understand better the recognition and binding mechanism behind this affinity pair formation at atomic level. Additionally, all these findings can also contribute to the molecular design of novel affinity ligands towards antibody purification as well as to evaluate their potential as a sustainable affinity chromatographic solution.

References

Elvin JG, Couston RG, van der Walle CF (2013) Therapeutic antibodies: market considerations, disease targets and bioprocessing. Int J Pharm 440:83–98. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.12.039

Hübner K, Sahle S, Kummer U (2011) Applications and trends in systems biology in biochemistry. FEBS 278:2767–2857. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08217.x

Gill DS, Damle NK (2006) Biopharmaceutical drug discovery using novel protein scaffolds. Curr Opin Biotech 17:653–658. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2006.10.003

Ayyar BV, Arora S, Murphy C, O’Kennedy R (2012) Affinity chromatography as a tool for antibody purification. Methods 56:116–129. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.10.007

Roque ACA, Silva CSO, Taipa MA (2007) Affinity-based methodologies and ligands for antibody purification: advances and perspectives. J Chromatogr A 1160:44–55. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2007.05.109

Teng SF, Sproule K, Husain A, Lowe CR (2000) Affinity chromatography on immobilized “biomimetic” ligands synthesis, immobilization and chromatographic assessment of an immunoglobulin G-binding ligand. J Chromatogr B 740:1–15

Batalha IL, Hussain A, Roque ACA (2010) Gum Arabic coated magnetic nanoparticles with affinity ligands specific for antibodies. J Mol Recognit 23:462–471. doi:10.1002/jmr.1013

Barroso T, Temtem M, Hussain A et al (2010) Preparation and characterization of a cellulose affinity membrane for human immunoglobulin G (IgG) purification. J Memb Sci 348:224–230

Barroso T, Roque ACA, Aguiar-Ricardo A (2012) Bioinspired and sustainable chitosan-based monoliths for antibody capture and release. RSC Adv 2:11285–11294. doi:10.1039/c2ra21687f

Branco RJF, Dias AMGC, Roque ACA (2012) Understanding the molecular recognition between antibody fragments and Protein A biomimetic ligand. J Chromatogr A 1244:106–115. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2012.04.071

Huang B, Liu F-F, Dong X-Y, Sun Y (2012) Molecular mechanism of the effects of salt and pH on the affinity between protein A and human immunoglobulin G1 revealed by molecular simulations. J Phys Chem B 116:424–433. doi:10.1021/jp205770p

Huang B, Liu F-F, Dong X-Y, Sun Y (2011) Molecular mechanism of the affinity interactions between protein A and human immunoglobulin G1 revealed by molecular simulations. J Phys Chem B 115:4168–4176. doi:10.1021/jp111216g

Barroso T, Lourenço A, Araújo M et al (2013) A green approach toward antibody purification: a sustainable biomimetic ligand for direct immobilization on (bio)polymeric supports. J Mol Recognit 26:662–671. doi:10.1002/jmr.2309

Sheldon RA (2012) Fundamentals of green chemistry: efficiency in reaction design. Chem Soc Rev 41:1437–1451. doi:10.1039/c1cs15219j

Dunn PJ (2012) The importance of green chemistry in process research and development. Chem Soc Rev 41:1452–1461. doi:10.1039/c1cs15041c

Salvalaglio M, Zamolo L, Busini V (2009) Molecular modeling of Protein A affinity chromatography. J Chromatogr A 1216:8678–8686

Saphire EO, Parren PW, Pantophlet R et al (2001) Crystal structure of a neutralizing human IGG against HIV-1: a template for vaccine design. Science 293:1155–1159. doi:10.1126/science.1061692

Morris G, Goodsell D (1998) Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J Comput Chem 19:1639–1662

Mehler EL, Solmajer T (1991) Electrostatic effects in proteins: comparison of dielectric and charge models. Protein Eng 4:903–910

Zamolo L, Busini V, Moiani D (2008) Molecular dynamic investigation of the interaction of supported affinity ligands with monoclonal antibodies. BiotechnolProgr 24:527–539

Hess B, Kutzner C (2008) GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J Chem Theor Comput 4:435–447

Schüttelkopf AW, Van Aalten DMF (2004) PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein-ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr D 60:1355–1363

Oostenbrink C, Villa A, Mark AE, van Gunsteren WF (2004) A biomolecular force field based on the free enthalpy of hydration and solvation: the GROMOS force-field parameter sets 53A5 and 53A6. J Comput Chem 25:1656–1676. doi:10.1002/jcc.20090

Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, van Gunsteren WF et al (1984) Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J Chem Phys 81:3684–3690. doi:10.1063/1.448118

Bussi G, Donadio D, Parrinello M (2007) Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J Chem Phys 126:014101–014107. doi:10.1063/1.2408420

Hess B, Bekker H, Berendsen HJC, Fraaije JGEM (1997) LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J Comput Chem 18:1463–1472. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199709)18:12<1463:AID-JCC4>3.0.CO;2-H

DeLano WL (2002) DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA

Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K (1996) VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph 14:33–38

Huey R, Morris G (2007) A semiempirical free energy force field with charge-based desolvation. J Comput Chem 28:1145–1152. doi:10.1002/jcc

Morris G, Huey R (2009) AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem 30:2785–2791. doi:10.1002/jcc

Winzor D (2001) Quantitative affinity chromatography. J Biochem Bioph Meth 49:99–121

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the financial support from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) through contracts PEst-C/EQB/LA0006/2011, MIT-Pt/BS-CTRM/0051/2008, PTDC/EBB-BIO/102163/2008, PTDC/EBB-BIO/098961/2008 and PTDC/EBB-BIO/118317/2010 and doctoral grants SFRH/BD/62475/2009 (T. B.) and SFRH/BPD/69163/2010 (R. B.), Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, FEDER.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barroso, T., Branco, R.J.F., Aguiar-Ricardo, A. et al. Structural evaluation of an alternative Protein A biomimetic ligand for antibody purification. J Comput Aided Mol Des 28, 25–34 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10822-013-9703-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10822-013-9703-1