Abstract

Purpose

To analyse relationships between semen parameters, sperm chromatin integrity and frequencies of chromosomally unbalanced, disomic and diploid sperm in 13 Robertsonian and 37 reciprocal translocation carriers and to compare the results with data from 10 control donors.

Methods

Conventional semen analysis, Sperm Chromatin Structure Assay and FISH with probes for chromosomes involved in the individual translocations and for chromosomes X, Y, 7, 8, 13, 18 and 21.

Results

Normal semen parameters were found in 30.8 % of Robertsonian and 59.5 % of reciprocal translocation carriers. The rates of unbalanced sperm were 12.0 % in Robertsonian and 55.1 % in reciprocal translocation carriers with no difference between normospermic patients and those showing altered semen parameters. Significantly increased frequencies of spermatozoa showing defects in chromatin integrity and condensation, aneuploidy for chromosomes not involved in a translocation and diploidy were detected in translocation carriers with abnormal semen parameters. Normospermic reciprocal translocation carriers showed an increase in chromosome 13 disomy compared to the control group. There was no relationship between gametic and somatic aneuploidy in 12 translocation carriers studied by FISH on sperm and lymphocytes. The frequency of motile sperm was negatively correlated with the frequency of sperm showing disomy, diploidy and defective chromatin condensation.

Conclusions

Abnormal semen parameters can serve as indicators of an additional risk of forming spermatozoa with defective chromatin and aneuploidy in translocation carriers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Balanced chromosomal translocations are often found as a cause of infertility [25]. They are particularly frequent among couples experiencing recurrent miscarriages and among men showing altered semen quality [9, 11, 26, 45, 48]. Robertsonian translocations are created by a fusion of two acrocentric chromosomes after their breakage and loss of p-arms. Their incidence in the population is 1.23/1000 newborns and the most common combination is the fusion of chromosomes 13 and 14 [31]. The normal and translocated chromosomes form a trivalent by pairing in the first meiotic division (MI) and segregate by alternate (normal/balanced) or unbalanced mode. The frequencies of unbalanced spermatozoa ranging between 3.4 % and 40 % were detected in male carriers of Robertsonian translocations [38].

Reciprocal translocations are produced by breakage and exchange of distal segments between non-homologous chromosomes. The incidence in the population is 1/712 newborn children [31]. During meiotic pairing, the normal and translocated chromosomes form a quadrivalent. Unbalanced spermatozoa were detected in male carriers of balanced reciprocal translocations in frequency of 18.6 %–80.7 % [3]. They arise by adjacent I, adjacent II, 3:1 or 4:0 segregation mode in anaphase I and their relative proportions and viability of resulting embryos depend on the chromosomes involved, position of breaks and recombination sites [3, 7, 15].

The existence of a possible interchromosomal effect of translocations (ICE), i. e. formation of gametes with another chromosomal abnormality due to meiotic disturbances caused by interactions of the translocated chromosomes with other non-homologous chromosomes, has not been fully established yet [1, 12, 21]. Significantly higher aneuploidy frequencies were reported in sperm and embryos of some balanced translocation carriers, but not in others [1, 19, 23, 33, 35, 47]. A correlation between germinal and somatic aneuploidy was described in both normospermic men and men showing abnormal semen parameters [2, 18, 39] and the underlying role of genomic instability and mitotic checkpoint in development of germinal and somatic aneuploidy was discussed in this connection.

In genetic counselling for family planning purposes, the prenatal testing, and alternatively, preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) are recommended to balanced translocation carriers because these patients are at increased risk of conceiving chromosomally abnormal embryos, resulting in implantation failure, miscarriage or delivery of affected offspring [19, 28, 36]. Attempts were made to find a relationship between the frequency of unbalanced gametes, semen parameters and an outcome of PGD [8, 13, 54], but more comprehensive studies are needed. In addition to conventional semen analysis and sperm FISH, the Sperm Chromatin Structure Assay (SCSA) providing information on the frequency of spermatozoa showing DNA fragmentation (DFI–percentage of mature spermatozoa with increased chromatin damage) and high DNA stainability (HDS, immature cells) can be used as a predictor of reproduction outcome based on the comparison with threshold values for normal fertility, i. e. 30 % DFI and 15 % of HDS cells [6, 14, 20, 22, 44, 49].

In this study, conventional semen analysis, SCSA and sperm FISH analysis of meiotic segregation of chromosomes involved in translocations and of aneuploidy for chromosomes X, Y, 7, 8, 13, 18 and 21 were performed in 50 translocation carriers and were compared with the results from 10 control donors. Relationships among the studied parameters were analysed by a correlation analysis. Finally, an association between sperm and somatic cell aneuploidy was tested on a subset of 12 translocation carriers.

Materials and methods

Patients and semen samples

Semen samples were obtained by masturbation from 13 carriers of Robertsonian and 37 carriers of reciprocal translocations and the control group of 10 men. For information on individual participants, see Tables 1 and 2. Samples were allowed to liquefy at room temperature, analyzed using standard techniques for semen analysis [56, 57], and stored frozen in liquid nitrogen without any cryopreservation until FISH and SCSA analysis. Samples were collected in a 6 year period (2006–2011). For the purpose of this study, the historical results of the semen analysis were compared with current reference values [57] to unify the classification of patients into groups (normal vs. abnormal). All participants gave their informed consent with the study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Brno, Czech Republic.

Sperm chromatin structure assay (SCSA)

The integrity of sperm chromatin was measured in 11 Robertsonian and 33 reciprocal translocation carriers and 10 control donors using SCSA method as described in Rybar et al. [42]. The DNA fragmentation index (DFI) and percentage of high density staining (HDS) cells were assessed using a flow cytometer (FACSCalibur flow cytometer; Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA, USA) operated by the CELLQuest software. Analysis of the data was performed using SCSA-Soft software (SCSA DIAGNOSTICS, INC, Multiplex Research & Technology Center, Brookings, USA).

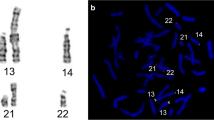

Sperm FISH

For the sperm FISH assay, semen samples were thawed at room temperature, smeared onto microscopic slides, and fixed by 3:1 solution of methanol:acetic acid. The sperm DNA was decondensed by incubation in DTT as described by Robbins et al. [37] and denatured in 50 % formamide at 72 °C for 4 min. The probe sets for FISH on sperm were selected for each individual translocation according to the position of breakpoints (Table 3). The multicolour FISH was performed according to the instructions of producers of probes (Oncor, Illkirch Cedex, France; Qbiogene, Illkirch Cedex, France; Vysis-Abbott, Abbott Park, IL, USA; Cytocell, Cambridge, UK; Kreatech, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Biotinylated probes used in some patients were detected by incubation with a 1:1 mixture of avidin-FITC (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and avidin-Cy3 (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, USA). In the interchromosomal effect study, α-satellite probes for chromosomes X, Y, 7, 8, and 18 (Vysis-Abbott) and locus specific probes for chromosomes 13 (Kreatech) and 21 (Vysis-Abbott) were used in combinations of two and three probes on three separate slides in each sample. The preparations were mounted using the antifade solution (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) containing 0.01 μg/ml DAPI (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA). The slides were examined using an Olympus BX60 fluorescence microscope equipped with necessary fluorescent filters and phase-contrast optics. Strict scoring criteria were used [40]. Briefly, only morphologically well defined, nonoverlapping spermatozoa were scored. The sperm was considered disomic for a chromosome when two fluorescence signals of the same colour, size, and intensity separated by a distance of at least one fluorescence domain diameter were observed inside the nucleus.

Somatic aneuploidy

Five patients (Rob4, Rob8, Rec5, Rec23, Rec24) showing a high frequency of disomy for chromosomes X, Y and 8, and seven patients (Rob7, Rec1, Rec2, Rec3, Rec20, Rec29, Rec35) showing a low frequency of disomy for these chromosomes in the sperm-FISH analysis were enrolled in the somatic aneuploidy study. Slides with phytohaemagglutinin stimulated cultured lymphocytes from venous blood samples obtained from each of the patients at the time of sperm collection for karyotype verification were used for the somatic aneuploidy analysis. FISH using the same X, Y, 8 probe mixture as in the sperm FISH was performed according to the manufacturers’ instructions and the preparations were finally mounted in the antifade solution containing 0.24 μg/ml DAPI.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by nonparametric Mann–Whitney exact tests, Pearson bivariate correlation and one-sample t-test for the ICE study using the SPSS software package, version 18 for Windows (SPSS, Inc. Chicago, IL, USA). The results were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Semen analysis

Semen characteristics of the study participants are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. The translocation carriers were divided into four groups (Group A–D) according to their translocation type and results of the semen analysis. The concentration at least 15 mil/ml, more than 40 % of motile sperm and more than 4 % of morphologically normal sperm were considered normal. Normal semen parameters were observed in 30.8 % of the Robertsonian and 59.5 % of the reciprocal translocation carriers. Asthenozoospermia was the most common abnormality (32 % of the translocation carriers). The control donors were normospermic.

SCSA

At least 5,000 sperm cells were measured by SCSA in each sample. Results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. There were significant differences in the percentage of HDS cells between normospermic translocation carriers and those showing abnormal semen parameters in both Robertsonian (P = 0.024) and reciprocal (P = 0.001) translocation carriers. When compared with control donors, significantly increased DFI and percentage of HDS cells were detected in patients with abnormal semen parameters (Group B, DFI and HDS both P < 0.001; Group D, DFI: P = 0.003, HDS: P < 0.001) but not in the normospermic translocation carriers (Groups A and C). Still, the 30 % DFI threshold value for normal fertility [14, 49] was exceeded in 28 % of the normospermic translocation carriers and in 63.2 % of the carriers with abnormal semen parameters. Concerning the percentage of HDS cells, the 15 % threshold value [49] was exceeded in 12 % of the normospermic carriers and in 84.2 % of the carriers with abnormal semen parameters.

Meiotic segregation of translocations

At least 3000 spermatozoa were scored from each Robertsonian translocation carrier (range 3001–3058) and the frequencies of chromosomally unbalanced gametes ranged from 5.8 % to 23.5 %. Concerning reciprocal translocation carriers ~1,000 spermatozoa (range 887–1111) were scored and the unbalanced gametes were observed in frequencies from 40.1 % to 69.2 %. Results are summarized in Table 3. Most of the gametes resulted from alternate segregation. Unbalanced gametes in reciprocal translocation carriers were most frequently formed through adjacent 1 segregation, while the adjacent 2 and 3:1 segregation modes were less abundant and comparably frequent. Other segregants were rare. The frequencies of chromosomally unbalanced gametes were not significantly different in normospermic translocation carriers and those showing abnormal semen parameters.

Interchromosomal effect

At least 10,000 spermatozoa (range 10,002 to 10,511) were scored from each of the men by sperm-FISH for each probe combination in the interchromosomal effect (ICE) study. The results are summarized in Table 4. Only disomic and diploid sperm were considered for the statistical evaluation as it is generally accepted in sperm aneuploidy studies [46]. The frequencies of diploidy observed in the ICE study corresponded to the diploidy/3:0 and diploidy/4:0 rates in the meiotic segregation study.

Concerning the interchromosomal effect, 62.0 % (31/50) of all translocation carriers (61.5 % of Robertsonian and 62.2 % of reciprocal translocation carriers) showed significantly increased frequencies of total disomic and diploid gametes compared with the control group. More men showing increased disomy and diploidy frequencies were among patients with abnormal semen parameters (18/23 vs. 13/27 in normospermic patients; see Table 4).

The normospermic translocation carriers did not show any increase in sperm disomy and diploidy compared with the control donors with the exception of a higher level of disomy 13 (P = 0.019) in normospermic reciprocal translocation carriers (Group C). There were no significant differences between Groups A and B of Robertsonian translocation carriers. However, significantly higher frequency of disomy 18 (P = 0.001) and 21 (P = 0.034) was detected in Group B with abnormal semen parameters than in the control donors. Concerning reciprocal translocation carriers, patients with abnormal semen parameters (Group D) showed significantly higher frequencies of disomy XY, disomy 18 and 21 and diploidy than normospermic carriers (P = 0.042, P = 0.021, P = 0.011 and P = 0.006) and control donors (P = 0.004, P = 0.01, P = 0.023 and P = 0.023).

Somatic aneuploidy

At least 5000 interphase lymphocytes per patient were scored in two groups of patients differing significantly (P = 0.003) in disomy frequency of chromosomes X, Y and 8 in sperm. The results are summarized in Fig. 1. No significant differences in the frequency of somatic aneuploidy were observed between the two groups. The aneuploidy rates were significantly higher (P = 0.008) in spermatozoa than in lymphocytes in the group of patients with high sperm aneuploidy frequencies.

Distributions of frequencies of sperm and lymfocytes aneuploid for chromosomes X, Y and 8 in the studied subgroups. The frequency of aneuploid sperm (Sample 1) and lymphocytes (Sample 2) in the group of patients showing high sperm aneuploidy was compared with the frequency of aneuploid sperm (Sample 3) and lymphocytes (Sample 4) in the group of patients with low sperm aneuploidy. The height of each box represents the 25 %–75 % data range, the horizontal line within each box represents the median value, and the upper and lower extensions represent the largest and smallest values. The donor Rob8 was considered a simple outlier (o), because his frequency of aneuploid sperm fell more than 1.5 box-lengths from the 25th percentile of the distribution for the ten donors

Correlations

Correlation and regression analyses, including available data from conventional semen analysis, SCSA, meiotic segregation and interchromosomal effect studies, were carried out. The frequency of motile sperm was found to be correlated with sperm concentration, total autosomal and sex disomies, diploidy and the frequency of HDS cells. The frequency of HDS cells was further correlated with DFI and diploidy. The results are displayed in Fig. 2. No other significant correlations were detected.

Discussion

Most of the patients included in this study were ascertained as translocation carriers while attending assisted reproduction centres for primary infertility. As the treatment by in vitro fertilization (IVF) was unsuccessful in most of them, a study combining conventional semen analysis, SCSA and sperm FISH analysis for meiotic segregation of translocations and aneuploidy was initiated to improve reproductive counselling. The value of this study lies primarily in the complex analysis of data on high numbers of sperm, obtained from a large group of patients, performed in the same laboratory by highly experienced scorers.

Conventional semen analysis is the first approach taken when searching for the cause of male infertility. In this study, normal semen parameters were found in 30.8 % of Robertsonian and 59.5 % of reciprocal translocation carriers. These rates are most likely lower than in a normal population, because semen samples from 226 donors were recently analyzed in our laboratory and normal semen parameters were observed in 82 % of them (unpublished results). In this study, all control donors were normospermic.

Among other methods of sperm analysis, SCSA provides useful data for predicting reproductive success. Virro et al. [49] reported a correlation of high DFI and increased frequency of immature (HDS) cells with a reduction of fertilization rates. Significantly higher DFI and frequency of HDS cells than in the control donors were described in translocation carriers previously studied by SCSA or TUNEL analyses [5, 34, 53]. In this study, a significant increase in DFI and HDS cells levels was detected only in Groups B and D (patients with abnormal semen characteristics). Still, the DFI and percentage of HDS cells exceeded the threshold values in 28 % and 12 %, respectively, of all normospermic translocation carriers. A correlation of the percentage of HDS cells with the frequencies of diploid cells was found in accordance with previously published papers [44, 53].

The sperm FISH method was adopted for analysis of chromosomes in sperm. The frequencies of gametes unbalanced for chromosomes involved in translocations were 5.8 %–23.5 % and 40.1 %–69.2 % in Robertsonian and reciprocal translocation carriers, respectively, which is within the range of previously published results [3, 27, 38]. The results were more heterogenous in reciprocal translocation carriers, which can be attributed to different meiotic configurations dependent on the character of individual translocations. There were no differences in the frequency of chromosomally unbalanced gametes between normospermic translocation carriers and carriers with abnormal semen parameters.

Concerning numerical aberrations of chromosomes not involved in translocations, 62.0 % of all translocation carriers showed increased frequencies of disomic and diploid gametes compared to the control group, indicating the interchromosomal effect of translocations (ICE). Anton et al. [1] reviewed previously published data on ICE and reported an increase in chromosomal disomy in about half of the 110 studied translocation carriers (54.5 % of Robertsonian and 43.9 % of reciprocal translocation carriers). The situation is complicated by the fact that individual chromosomes seem to be differentially affected and there are significant differences among individual translocation carriers. Moreover, a relationship between aneuploidy and poor semen parameters observed previously even in men with normal karyotype must not be neglected [16, 21, 33, 41, 47]. Also in this study, significantly increased frequencies of total sperm disomy and diploidy were observed more frequently among translocation carriers with abnormal semen parameters. Groups B and D of translocation carriers with abnormal semen parameters showed increased frequencies of disomy 18 and 21 compared to control donors. Additionally, frequencies of sperm showing XY disomy and diploidy were significantly higher in reciprocal translocation carriers with abnormal semen parameters than in the control group. These data, as well as the results of SCSA showed relationships between the spermatogenic outcome detectable by conventional techniques and internal sperm anomalies and indicated an increased reproductive genetic risk in translocation carriers with abnormal semen parameters.

However, the disomy of chromosome 13 was significantly increased in the group of normospermic reciprocal translocation carriers compared to control. This implies that the presence of a balanced translocation might affect segregation of other chromosomes (ICE) in some carriers without any abnormality detectable by spermatological examinations. The phenomenon of ICE is most probably based on interactions of the asynapsed regions of chromosomes involved in trivalent and quadrivalent structures with other partially asynapsed bivalents, especially with acrocentric and sex chromosomes, which might affect their equal segregation [29, 32, 43]. A considerable interindividual variability in disomy and diploidy rates observed in our group of translocation carriers might be explained by differences in meiotic configurations [4] and unique spatial proximity of non-homologous chromosomal pairs, which was previously shown to be non-random [24] and altered in translocation carriers [55]. The meiotic disturbances, if recognized by control mechanisms, lead to meiotic arrest and production of semen with altered conventional parameters [32]. This might be the case of Robertsonian translocation carriers in our group, as only 30.8 % of them were normospermic.

Associations between germinal and somatic aneuploidy were described previously in men showing abnormal semen parameters and in normospermic men [18, 39]. The underlying role of the genomic instability, altered function of the spindle apparatus and mitotic checkpoint control, as well as the individual susceptibility to the exposure to genotoxic agents was discussed in this context [2, 10, 18, 39]. In this study, no difference in somatic aneuploidy was detected between two subgroups of patients showing a significant difference in the frequency of sperm disomy (chromosomes X, Y and 8). This assumes a different mechanism of aneuploidy formation in gametes of chromosomal translocation carriers.

From a practical point of view, it has to be mentioned that in translocation carriers, most of the sperm with chromosomal abnormalities are sperm with unbalanced karyotypes arising from meiotic segregation of translocations. Frequencies of aneuploid sperm are low despite their statistically significant increase in some patients. However, in some Robertsonian translocation carriers, total aneuploidy rates can thus reach or even exceed the frequency of gametes with unbalanced karyotype. The information about the frequency of abnormal sperm, including internal anomalies detected by sperm FISH and sperm DNA fragmentation analysis, if implemented in genetic counselling preceding assisted reproduction, helps to specify the additional reproductive risk and predict the outcome of IVF cycle [13, 20, 22, 30, 41]. The results of preimplantation genetic diagnosis for translocations and preimplantation aneuploidy screening in embryos from translocation carriers were demonstrated by Gianaroli et al. [19], Pujol et al. [35] and Fiorentino et al. [17].

In this study, a relationship between sperm motility and frequencies of spermatozoa showing disomy, diploidy and defective chromatin condensation is reported. Translocation carriers with altered semen parameters were shown to be at increased risk of forming gametes aneuploid for chromosomes not involved in the translocation. This should be considered for reproductive genetic counselling and planning of preimplantation embryo testing in such patients.

References

Anton E, Vidal F, Blanco J. Interchromosomal effect analyses by sperm FISH: incidence and distribution among reorganization carriers. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2011;57:268–78.

Aston KI, Carrell DT. Emerging evidence for the role of genomic instability in male factor infertility. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2012;58:71–80.

Benet J, Oliver-Bonet M, Cifuentes P, Templado C, Navarro J. Segregation of chromosomes in sperm of reciprocal translocation carriers: a review. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;111:281–90.

Blanco J, Egozcue J, Vidal F. Interchromosomal effects for chromosome 21 in carriers of structural chromosome reorganizations determined by fluorescence in situ hybridization on sperm nuclei. Hum Genet. 2000;106:500–5.

Brugnon F, Van Assche E, Verheyen G, Sion B, Boucher D, Pouly JL, Janny L, Devroey P, Liebaers I, Van Steirteghem A. Study of two markers of apoptosis and meiotic segregation in ejaculated sperm of chromosomal translocation carrier patients. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:685–93.

Bungum M, Humaidan P, Spano M, Jepson K, Bungum L, Giwercman A. The predictive value of sperm chromatin structure assay (SCSA) parameters for the outcome of intrauterine insemination, IVF and ICSI. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1401–8.

Cans C, Cohen O, Lavergne C, Mermet MA, Demongeot J, Jalbert P. Logistic regression model to estimate the risk of unbalanced offspring in reciprocal translocations. Hum Genet. 1993;92:598–604.

Cassuto NG, Le Foll N, Chantot-Bastaraud S, Balet R, Bouret D, Rouen A, Bhouri R, Hyon C, Siffroi JP. Sperm fluorescence in situ hybridization study in nine men carrying a Robertsonian or a reciprocal translocation: relationship between segregation modes and high-magnification sperm morphology examination. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:826–32.

De Braekeleer M, Dao TN. Cytogenetic studies in male infertility: a review. Hum Reprod. 1991;6:245–50.

De Palma A, Burrello N, Barone N, D'Agata R, Vicari E, Calogero AE. Patients with abnormal sperm parameters have an increased sex chromosome aneuploidy rate in peripheral leukocytes. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:2153–6.

Dohle GR, Halley DJ, Van Hemel JO, van den Ouwel AM, Pieters MH, Weber RF, Govaerts LC. Genetic risk factors in infertile men with severe oligozoospermia and azoospermia. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:13–6.

Douet-Guilbert N, Bris MJ, Amice V, Marchetti C, Delobel B, Amice J, Braekeleer MD, Morel F. Interchromosomal effect in sperm of males with translocations: report of 6 cases and review of the literature. Int J Androl. 2005;28:372–9.

Escudero T, Abdelhadi I, Sandalinas M, Munne S. Predictive value of sperm fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis on the outcome of preimplantation genetic diagnosis for translocations. Fertil Steril. 2003;79 Suppl 3:1528–34.

Evenson D, Wixon R. Meta-analysis of sperm DNA fragmentation using the sperm chromatin structure assay. Reprod Biomed Online. 2006;12:466–72.

Faraut T, Mermet MA, Demongeot J, Cohen O. Cooperation of selection and meiotic mechanisms in the production of imbalances in reciprocal translocations. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2000;88:15–21.

Ferfouri F, Selva J, Boitrelle F, Gomes DM, Torre A, Albert M, Bailly M, Clement P, Vialard F. The chromosomal risk in sperm from heterozygous Robertsonian translocation carriers is related to the sperm count and the translocation type. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:1337–43.

Fiorentino F, Spizzichino L, Bono S, Biricik A, Kokkali G, Rienzi L, Ubaldi FM, Iammarrone E, Gordon A, Pantos K. PGD for reciprocal and Robertsonian translocations using array comparative genomic hybridization. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:1925–35.

Gazvani MR, Wilson ED, Richmond DH, Howard PJ, Kingsland CR, Lewis-Jones DI. Role of mitotic control in spermatogenesis. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:251–6.

Gianaroli L, Magli MC, Ferraretti AP, Munné S, Balicchia B, Escudero T, Crippa A. Possible interchromosomal effect in embryos generated by gametes from translocation carriers. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:3201–7.

Kennedy C, Ahlering P, Rodriguez H, Levy S, Sutovsky P. Sperm chromatin structure correlates with spontaneous abortion and multiple pregnancy rates in assisted reproduction. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;22:272–6.

Kirkpatrick G, Ferguson KA, Gao H, Tang S, Chow V, Yuen BH, Ma S. A comparison of sperm aneuploidy rates between infertile men with normal and abnormal karyotypes. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:1679–83.

Larson-Cook KL, Brannian JD, Hansen KA, Kasperson KM, Aamold ET, Evenson DP. Relationship between the outcomes of assisted reproductive techniques and sperm DNA fragmentation as measured by the sperm chromatin structure assay. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:895–902.

Machev N, Gosset P, Warter S, Treger M, Schillinger M, Viville S. Fluorescence in situ hybridization sperm analysis of six translocation carriers provides evidence of an interchromosomal effect. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:365–73.

Manvelyan M, Hunstig F, Bhatt S, Mrasek K, Pellestor F, Weise A, Simonyan I, Aroutiounian R, Liehr T. Chromosome distribution in human sperm—a 3D multicolor banding-study. Mol Cytogenet. 2008;1:25.

Martin RH. Cytogenetic determinants of male fertility. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14:379–90.

Morel F, Douet-Guilbert N, Le Bris MJ, Amice V, Le Martelot MT, Roche S, Valéri A, Derrien V, Amice J, De Braekeleer M. Chromosomal abnormalities in couples undergoing intracytoplasmic sperm injection. A study of 370 couples and review of the literature. Int J Androl. 2004;27:178–82.

Morel F, Douet-Guilbert N, Le Bris MJ, Herry A, Amice V, Amice J, De Braekeleer M. Meiotic segregation of translocations during male gametogenesis. Int J Androl. 2004;27:200–12.

Munné S. Analysis of chromosome segregation during preimplantation genetic diagnosis in both male and female translocation heterozygotes. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;111:305–9.

Navarro J, Vidal F, Benet J, Templado C, Marina S, Egozcue J. XY-trivalent association and synaptic anomalies in a male carrier of a Robertsonian t(13;14) translocation. Hum Reprod. 1991;6:376–81.

Nicopoullos JD, Gilling-Smith C, Almeida PA, Homa S, Nice L, Tempest H, Ramsay JW. The role of sperm aneuploidy as a predictor of the success of intracytoplasmic sperm injection? Hum Reprod. 2008;23:240–50.

Nielsen J, Wohlert M. Chromosome abnormalities found among 34,910 newborn children: results from a 13-year incidence study in Arhus, Denmark. Hum Genet. 1991;87:81–3.

Oliver-Bonet M, Benet J, Sun F, Navarro J, Abad C, Liehr T, Starke H, Greene C, Ko E, Martin RH. Meiotic studies in two human reciprocal translocations and their association with spermatogenic failure. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:683–8.

Pellestor F, Imbert I, Andréo B, Lefort G. Study of the occurrence of interchromosomal effect in spermatozoa of chromosomal rearrangement carriers by fluorescence in-situ hybridization and primed in-situ labelling techniques. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1155–64.

Perrin A, Caer E, Oliver-Bonet M, Navarro J, Benet J, Amice V, De Braekeleer M, Morel F. DNA fragmentation and meiotic segregation in sperm of carriers of a chromosomal structural abnormality. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:583–9.

Pujol A, Benet J, Staessen C, Van Assche E, Campillo M, Egozcue J, Navarro J. The importance of aneuploidy screening in reciprocal translocation carriers. Reproduction. 2006;131:1025–35.

Rius M, Obradors A, Daina G, Ramos L, Pujol A, Martínez-Passarell O, Marquès L, Oliver-Bonet M, Benet J, Navarro J. Detection of unbalanced chromosome segregations in preimplantation genetic diagnosis of translocations by short comparative genomic hibridization. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:134–42.

Robbins WA, Segraves R, Pinkel D, Wyrobek AJ. Detection of aneuploid human sperm by fluorescence in situ hybridization–evidence for a donor difference in frequency of sperm disomic for chromosomes-I and chromosomes-Y. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;52:799–807.

Roux C, Tripogney C, Morel F, Joanne C, Fellmann F, Clavequin MC, Bresson JL. Segregation of chromosomes in sperm of Robertsonian translocation carriers. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;111:291–6.

Rubes J, Vozdova M, Robbins WA, Rezacova O, Perreault SD, Wyrobek AJ. Stable variants of sperm aneuploidy among healthy men show associations between germinal and somatic aneuploidy. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:1507–19.

Rubes J, Vozdova M, Oracova E, Perreault SD. Individual variation in the frequency of sperm aneuploidy in humans. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;111:229–36.

Rubio C, Gil-Salom M, Simón C, Vidal F, Rodrigo L, Mínguez Y, Remohí J, Pellicer A. Incidence of sperm chromosomal abnormalities in a risk population: relationship with sperm quality and ICSI outcome. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:2084–92.

Rybar R, Markova P, Veznik Z, Faldikova L, Kunetkova M, Zajicova A, Kopecka V, Rubes J. Sperm chromatin integrity in young men with no experiences of infertility and men from idiopathic infertility couples. Andrologia. 2009;41:141–9.

Sciurano RB, Rahn MI, Rey-Valzacchi G, Coco R, Solari AJ. The role of asynapsis in human spermatocyte failure. Int J Androl. 2012;35:541–9.

Sills ES, Fryman JT, Perloe M, Michels KB, Tucker MJ. Chromatin fluorescence characteristics and standard semen analysis parameters: correlations observed in andrology testing among 136 males referred for infertility evaluation. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24:74–7.

Stern C, Pertile M, Norris H, Hale L, Baker HW. Chromosome translocations in couples with in-vitro fertilization implantation failure. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:2097–101.

Templado C, Bosch M, Benet J. Frequency and distribution of chromosome abnormalities in human spermatozoa. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;111:199–205.

Vegetti W, Van Assche E, Frias A, Verheyen G, Bianchi MM, Bonduelle M, Liebaers I, Van Steirteghem A. Correlation between semen parameters and sperm aneuploidy rates investigated by fluorescence in-situ hybridization in infertile men. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:351–65.

Vincent MC, Daudin M, De MP, Massat G, Mieusset R, Pontonnier F, Calvas P, Bujan L, Bourrouillout G. Cytogenetic investigations of infertile men with low sperm counts: a 25-year experience. J Androl. 2002;23:18–22.

Virro MR, Larson-Cook KL, Evenson DP. Sperm chromatin structure assay (SCSA) parameters are related to fertilization, blastocyst development, and ongoing pregnancy in in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycles. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:1289–95.

Vozdova M, Oracova E, Horinova V, Rubes J. Sperm fluorescence in situ hybridization study of meiotic segregation and an interchromosomal effect in carriers of t(11;18). Hum Reprod. 2008;23:581–8.

Vozdova M, Oracova E, Gaillyova R, Rubes J. Sperm meiotic segregation and aneuploidy in a 46,X,inv(Y),t(10;15) carrier: case report. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1748.e9–1748.e13.

Vozdova M, Oracova E, Musilova P, Kasikova K, Prinosilova P, Gaillyova R, Rubes J. Sperm and embryo analysis of similar t(7;10) translocations transmitted in two families. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:e66–70.

Vozdova M, Kasikova K, Oracova E, Prinosilova P, Rybar R, Horinova V, Gaillyova R, Rubes J. The effect of the swim-up and hyaluronan-binding methods on the frequency of abnormal spermatozoa detected by FISH and SCSA in carriers of balanced chromosomal translocations. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:930–7.

Wiland E, Midro AT, Panasiuk B, Kurpisz M. The analysis of meiotic segregation patterns and aneuploidy in the spermatozoa of father and son with translocation t(4;5)(p15.1;p12) and the prediction of the individual probability rate for unbalanced progeny at birth. J Androl. 2007;28:262–72.

Wiland E, Zegało M, Kurpisz M. Interindividual differences and alterations in the topology of chromosomes in human sperm nuclei of fertile donors and carriers of reciprocal translocations. Chromosome Res. 2008;16:291–305.

World Health Organization (1999) WHO laboratory manual for the examination of human semen and semen-cervical mucus interaction, 4th edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. ISBN 9780521645997

World Health Organization (2010) WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen, 5th edn. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. ISBN 978 92 4 154778 9

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients for their participation in the study. We wish to thank Mr. Paul Veater (Bristol, United Kingdom) for proofreading the translated manuscript. Supported by the Grant Agency of the Czech Ministry of Health, grant No. NS9842-4/2008 and CEITEC–Central European Institute of Technology (ED1.1.00/02.0068) from the European Regional Development Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Capsule

Translocation carriers showing abnormal semen parameters are at increased risk of forming gametes with additional numerical chromosomal aberrations and defective chromatin condensation.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vozdova, M., Oracova, E., Kasikova, K. et al. Balanced chromosomal translocations in men: relationships among semen parameters, chromatin integrity, sperm meiotic segregation and aneuploidy. J Assist Reprod Genet 30, 391–405 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-012-9921-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-012-9921-9