Abstract

The coparenting relationship has been linked to parenting stress, parenting self-efficacy and many other concerns associated with the development of children with ASD. Parents of children with ASD (N = 22) were interviewed to explore three domains of their coparenting relationship; (1) adaptation to the emergence of their child’s autism, (2) parenting their child with ASD, (3) expectations for their child’s developmental outcomes. The concept of coparenting competence, developed during analysis, describes collective perceptions of parenting efficacy. Parents linked perceptions of coparenting competence to their, ability to cope with diagnosis and parenting, motivation to do what they could for their child, and hopes for their child’s development. The concept of coparenting competence could play an important role in future research and intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Theorists and family researchers have adopted the term coparenting to describe unique relationships that operate in the family’s parenting executive; the coparenting relationship refers to aspects of the parents’ relationship that are tied to the raising of children (Feinberg 2003; McHale and Kuersten-Hogan 2004; Van Egeren 2004). While there is interplay between the coparenting partnership and the parents’ romantic relationship, the coparenting partnership remains a substantially independent construct which can stay strong and supportive when other facets of the parent relationship are not performing well (Feinberg 2003; Feinberg et al. 2012; Morrill et al. 2010). The coparenting partnership therefore forms a distinct entity within family systems and children have different relationships with this entity than they do with either of their parents. The present paper reports on an investigation of parents’ reflections on the adaptation and importance of their parenting partnership during the emergence of their child’s autism, for their current parenting, and for their expectations of their child’s future development.

The relationship that children have with their parenting partnership plays an important role in children’s social and emotional development. Multiple studies in families of typically developing children, using different methodologies, have found that coparenting quality is predictive of both parent and teacher reports of children’s externalising behaviours, not explained by factors such as nurturance, responsiveness and consistency in parenting style, in families of infants, young school aged children and adolescents (Karreman et al. 2008; Feinberg et al. 2007; Schoppe-Sullivan et al. 2009; Teubert and Pinquart 2010). Support for the reciprocal nature of this complex relation has also been found in longitudinal studies. McHale et al. (2004) found, in a mixed-method longitudinal study on married couples, that coparenting cohesion—an indicator of coparenting quality—was predictive of parental assessments of children’s reactivity and, in another longitudinal mixed-method study on intact parenting couples, Fivas-Depeursinge et al. (2009) found that toddlers’ styles of interaction with their parents predicted patterns of cohesion and disunity in the parenting partnership.

However, the importance of coparenting quality may be influenced by the context in which the parenting partnership operates. Coparenting quality may be particularly important in families where there are children whose development is characterised by challenging behaviours such as those with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Children with an ASD are more likely than other children to develop externalising behaviour problems, impaired social development, and a limited capacity to participate in symbolic play (Jarrold et al. 1993; Levy et al. 2009).

Coparenting quality has also been associated with a range of developmental concerns commonly found in children with an ASD. In a study with typically developing children Groenendyk and Volling (2007) found a significant positive correlation between coparenting quality and conscience development, an important component of social behaviour in children with an ASD. Keren et al. (2005) found that a coparenting style marked by cooperation and autonomy predicted higher levels of symbolic play during triadic interactions in children with an ASD. Therefore, in addition to behavioural concerns, specific developmental concerns and behavioural characteristics associated with an ASD may be influenced by the quality of the parents’ coparenting relationship.

The quality of the coparenting relationship may also determine how parents cope with the experience of parenting a child with an ASD. Parents of children with an ASD are likely to experience high and damaging levels of parenting stress which predict both child and parent negative outcomes (Hayes and Watson 2013). Parenting stress has been found to share important relations with coparenting quality in both mothers and fathers of children with an ASD (May et al. 2014). Although many studies have reported that fathers of typically developing children report lower levels of parenting stress than mothers this is unlikely to be the experience in families with a child with an ASD. May et al. (2014) demonstrated support for Keen et al. (2010) finding that that mothers and fathers of children with an ASD are likely to experience high and similar levels of parenting stress. This is important because the association between cumulative tensions and child behaviour problems is thought to be amplified when both parents are experiencing chronic parenting stress (Belsky et al. 1995). High and similar levels of parenting stress experienced by parents of children with an ASD could serve to augment negative interactions between child behaviour and coparenting quality.

Another indicator of the link between coparenting quality and the parenting of a child with an ASD is found in research exploring connections between coparenting and marital quality. Complex interactive pathways have been reported between coparenting quality, parenting practices, marital adjustment, marital warmth, and overall marital health (Bonds and Gondoli 2007; Morrill et al. 2010). Marital conflict, which has been linked to competitive coparenting, is thought to be more common in parents of children with an ASD (McHale 1995), associated with elevated levels of disruptive and difficult behaviour in typically developing children (McHale and Kuersten-Hogan 2004), and predictive of higher levels of perceived symptomatology in children with autism (Kelly et al. 2008). The interconnected nature of relationships within family systems suggests that alterations in marital quality associated with the parenting of a child with an ASD could influence the support that parents receive through their parenting partnership.

Partner support, a key characteristic of coparenting quality, is likely to play a particularly important role in determining parent outcomes in families where there is a child with an ASD. Parents of typically developing children usually identify their marital partner as their main source of parenting support (Kersh et al. 2006; Cowan and Cowan 2010), and the social isolation experienced by parents of children with an ASD could therefore make this aspect of their coparenting partnership particularly important (Gray 2003). Studies investigating partner support in parents of children with an ASD have found that fathers in these families are more likely to use avoidant coping than other fathers, while mothers in these families tend to take on a stronger central role in their child’s care (Brobst et al. 2009; Gray 2003; Higgins et al. 2005; Hastings et al. 2005; Pozo et al. 2014). These alterations in roles and responsibilities often occur alongside a loss of support from extended family and social networks.

The accumulated evidence therefore suggests that the coparenting relationship could play an important role in determining both child and parent outcomes in families where there is a child with an ASD. However, there has been very little research exploring the adaptation of parenting partnerships to the parenting of a child with an ASD. A recent grounded theory exploration of coparenting in families where there is a child with an ASD found that parents made adaptive alterations in parenting roles and responsibilities in response to the emergence of their child’s ASD (Hock et al. 2012). These included an increase in “tag team parenting” which inflated parents’ sense of isolation by reducing opportunities for the support and connection that they might receive during joint parenting activities (Hock et al. 2012). The present study makes a contribution to this area of enquiry by exploring key aspects of the adaptation of coparenting partnerships to the parenting of a child with an ASD. The investigation explored this adaptation by asking parents to reflect on relations between their parenting partnership and their experiences of the emergence of their child’s autism, their current parenting, and future expectations for this child’s development.

Method

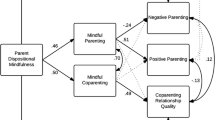

The sequential explanatory mixed-methodology of the larger study consisted of two distinct but related phases of data collection and analysis wherein data from the initial quantitative analysis (May et al. 2014) was used to inform the selection of participants in a qualitative enquiry designed to explore and explain the quantitative outcomes (Creswell et al. 2008). These processes served to link two arms of a substantially segregated investigation (Creswell et al. 2008).

The qualitative arm of the study, presented in this paper, explored three domains of the coparenting experience. The first domain concerned how coparenting relationships adapted to the emergence of autism in the child. The second explored how coparenting relationships functioned in the parenting of a child with an ASD. The third concerned parents’ expectations of the influence that their parenting relationship would have on their child’s developmental outcomes.

A guided interview schedule (Table 1) was designed to bring out participants’ views concerning a few general topics (Marshall and Rossman 2011). Questions were designed with knowledge acquired from the literature, the quantitative arm of the study, and expert consultation. The interview schedule contained 17 questions with four being either administrative or icebreaking while the others were designed to provoke responses in relation to key concepts such as coparenting quality and parenting self-efficacy (Roulston 2010). Questions were designed to elicit parent responses in relation to the underlying factors represented by these latent variables. For example, when exploring coparenting quality, questions were asked about parenting conflict and partner strengths. Some questions were designed to tease out specific responses about issues such as parenting teamwork, while others were designed to provoke discussion on broader topics such as support and helpfulness. Many questions were also designed to encourage parents to bring information into the interview that was within the study’s area of interest but not confined by the theoretical bias of the investigation (Roulston 2010). The interview was piloted on a small sample of parents and modifications were made before applying the schedule in the broader cohort of participants.

The Interview Sample

The recruitment of parenting couples contributed to methodological challenges of the study. The recruitment of fathers can be particularly challenging but they are more likely to participate in research that is less intrusive and adaptable to their scheduling needs (Mitchell et al. 2007). Recruitment was further complicated by the difficulty that parents of children with an ASD often experience in leaving their children with other carers and attending out of home activities (Gray 1997). Parents were therefore offered phone interviews at a time and day of their choice.

Participants (N = 11 couples) in this arm of the study were biological, cohabitating mothers and fathers parenting couples (Table 2). To ensure heterogeneous sampling in regard to parenting stress, couples with the highest (N = 5) and lowest (N = 6) aggregated PSI scores were invited to participate.

Sample Size and Data Saturation

Data saturation in qualitative enquiry occurs when it becomes apparent that further data collection and analysis will be unlikely to alter the outcomes of an investigation. Data saturation often occurs after interviewing approximately ten participants (Guest et al. 2006; Smith and Smith 2003). A theoretical lack of independence between participants in a parenting partnership required that parenting couples were counted as individuals in sample size calculations. The investigation interviewed ten couples before making an interim assessment, which determined that saturation had been achieved. Data saturation was determined to be achieved when data from the final interviews did not make a meaningful contribution to complexity.

Piloting the Interview Schedule

Pilot interviews were conducted with three couples to assess the efficacy of the interview schedule, process, and suitability of the thematic coding framework. Parents’ satisfaction with the process was evidenced by their completion of the interview and desire to provide extra information. Only minor alterations to the interview schedule were required following the analysis of pilot data. The first was to remove the question “How would you describe the teamwork between you both in regard to parenting (name of child/n)?” This question tended to elicit a short and uninformative response such as “good” or “great” and did not contribute to the quality or quantity of the data. The second modification was to remove the question “Has having a child like (name of child with an ASD) changed the way that you work together as a parenting team?” because parents had provided this information elsewhere in the interview. Minimal change to the schedule meant that pilot data, when participants met the eligibility criteria, was eligible for use in the final analysis.

The Interview Process

Interviews were conducted at a time when both parents were available to ensure each parent was interviewed before they could discuss the experience with their partner. Parents were asked to move to an isolated part of their home so that responses could not be overheard by their children or parenting partner. All parents said they were complying with this request; a claim supported by an absence of background noise during the interviews. Parents were advised that they could withdraw from the interview at any time and the interviewer monitored for signs of distress by asking parents ‘… if the interview was going OK’ and if they were ‘happy to continue’ at a predetermined halfway point in the schedule. None of the parents reported distress and all continued to the end of the interview. Initial interviews were conducted alternately with mothers and fathers to reduce risk of a gender bias. Interviews were digitally recorded and later transcribed by the investigator.

The Analytic Program

The analysis of qualitative data has been described by Marshall and Rossman (2011) as a “search for general statements about relationships and underlying themes” (p. 207). The methodology for the qualitative arm of this investigation was underpinned by a theoretically driven and an interpretive process in which the researcher, using the current state of knowledge about coparenting quality in this and other contexts, was overtly seeking information on specific issues related to the coparenting partnership (Roulston 2010). A neo-positivist approach, as compared to more post-modern phenomenological approaches, was utilised, where external and objectively verifiable reality was assumed to exist within parents’ reports of their experiences (Sandelowski and Barroso 2003).

The interview questions were designed to generate data that could be differentiated into a set of a priori themes related to each of the three domains. However, the investigation allowed for the possibility that other factors, not identified in literature review, would influence the adaptation of coparenting partnerships to the parenting of a child with an ASD. The investigation therefore employed a thematic analysis in which a priori themes were theoretically derived and then reorganised to fit the data while new themes were developed as required by the evidence (Braun and Clarke 2006; Morse 2003). Themes were reorganised and redefined several times, using an iterative process, until an array of sufficiently delineated, logically coherent and relevant themes had emerged. NVivo 9 was used to organise and code the data (QSR International 2006).

Results

The themes below describe the three domains of, first, parents’ adaption to the emergence of their child’s ASD, second, the sense of partnership that they were experiencing in parenting their child with an ASD, and third, their expectations of how the quality of their parenting partnership would influence their child’s ability to reach their developmental potential. Through analysis of the data, relying on both a priori and interpretive themes, one central concept emerged as integral to parents’ experience in these three domains: a sense of coparenting competence. This sense of coparenting competence first appeared in descriptions of how parents coped with the emergence of their child’s ASD but was present across all domains of the enquiry. Parents described how their sense of coparenting competence helped them to cope with the adaptation to the parenting of their child with an ASD, helped them to manage their individual and collective roles in the parenting of this child, and how they expected this would go on to influence the developmental outcomes of this child.

The analytic commentary is supported by quotations from parent interviews (ID codes used and names changed to protect identity). Although quotations presented in the original doctoral dissertation were reasonably distributed [mother quotations (M) N = 55, range 3–9, M = 5.0; father quotations (F): N = 42, range 1–7, M = 3.81], only relevant quotations are shown in the present paper. The presentation of results is also supported by code frequencies indicating prevalence or singularity of particular categories. The report begins in the first analytic domain, with an exploration of how the parenting partnership adapted to the emergence of a child’s ASD.

Domain One: Adaptation of the Coparenting Relationship to the Emergence of a Child with an ASD

In response to questions about how having a child with an ASD had changed the parenting experience and parenting expectations participants described how the emergence of their child’s ASD influenced parenting expectations, roles, and responsibilities—through adjusting, changing, and adapting—as they worked together to deal with the job at hand.

An intense period of change was associated with the emergence of children’s autism as “… having a child with autism has pretty much turned everything upside down, changed all the expectations, changed what you thought about your life.” In response to this change the parents described how a collective responsibility to deal with an unexpected and difficult task developed between them. Parents described how it was their duty to care for the child, how they needed to “get their act together” to deal with the challenge of parenting their child, and how they worked at their parenting relationship to help their child achieve optimal developmental outcomes. The importance of their parenting partnership in adapting to their unique circumstances is exemplified by this quote … “The books didn’t help so we had to work it out together.”

Consistent with previous research almost all of the parents (19/22) described changes in their parenting roles as they began to understand that their child had an ASD (Hock et al. 2012). For example one mother stated “Whether you like it or not you have to change what you know and what you do and how you understand what is going on with your child”, and these changes tended to occur without negotiation “… we never actually formally agreed on what our roles would be but, ah, I suppose I trudge off to work and earn the money and Tess has really sacrificed her career to assist Toby …”.

Periods of change and uncertainty, fuelled by dissonance between expectations and reality, are likely to stimulate a process of self-evaluation that can result in a redefining of role identities and role relationships within the family (Stryker 1968). Some parents provided explicit descriptions of how the demands of parenting a child with an ASD had created pressure on them to alter the way that they worked with their parenting partner.

“… learning that you can’t do it all on your own. Yeah, you have to learn to communicate with your partner with your family … learning how to be more flexible took a lot of patience and caused a lot of stress because I am a control freak, I like things to be done in a certain way. So that journey was quite stressful” and “You can’t get out of the game so you have to make the game work.”

Coparenting Competence

Like many other parents of children with special needs, the parents in this sample described both reactive and pragmatic decisions regarding distribution of their parenting roles and responsibilities to make the parenting relationship work (Burton et al. 2008; Curran et al. 2001; Mason and Pavia 2006). The notion of making the relationship ‘work’ emerged as a significant process as parents went on to describe how the diagnosis served as a catalyst for them to place greater value on their coparenting partnership and encouraged them to make this relationship work effectively. In this, they were illustrating a belief that their parenting partnership was able to achieve its purpose in a variety of contexts. Collective perceptions of efficacy are a “group’s shared beliefs in its conjoint capability to organize and execute the course of action required to produce given levels of attainments” (Bandura 1997). As evidence of parents’ perceptions of their collective parenting efficacy emerged in the analysis, the concept of coparenting competence was developed to capture these perceptions and the surfacing of this capability. Coparenting competence was subsequently defined by the investigators as: a parent’s sense of a collective parenting efficacy generated from their coparenting partnership and only existing in association with that relationship. The following sections demonstrate the relevance and pervasive nature of coparenting competence and elaborate on how this concept developed.

Domain Two: Parenting in Partnership

Data in this domain was initially organised into sub-themes derived from coparenting theory, such as coparenting solidarity, cooperation, communication, co-ordination, partner support, shared parenting, and managing conflict and antagonism (Feinberg 2003; Van Egeren and Hawkins 2004). This framework of subthemes proved to be a useful means of organising the data. However, the analysis revealed perceptions of coparenting competence permeating each of these constituents of the coparenting relationship as parents used examples of coparenting competence to illustrate how and why they went about the work of parenting their child with an ASD.

A Sense of Solidarity

A sense of solidarity was experienced by parents when they felt they were on a ‘shared journey’ that involved appreciation, camaraderie and compromise. When illustrating how their relationship worked, the parents often described their parenting partner’s complementary qualities and how their collective skills and abilities created an environment that would meet their child’s developing needs. Fathers tended to talk about their partners’ parenting strengths in broad terms such as “… she will just do whatever he needs, not worrying about money or anything; just focusing on his needs.” Whereas mothers tended to focus on specific things that fathers contributed to the relationship “Yeah he is good at engaging him and entertaining him but he is also good at thinking about how we can use this to do something more for his development.”

Parents linked this ability to find and accommodate their partner’s strengths to making their parenting partnership work: “I understand where his [the father’s] strengths are and where mine are … he helps me deal with him as well … we complement each other.” In doing so they linked a collective sense of parenting purpose to their ability to keep their parenting relationship working “… we both want what’s best for our children so at the end of the day that’s the thing that keeps it working” … or protected their partnership from not working: “You’ve got to be on the same wavelength otherwise it would just be like chaos I think. There would be no real structure or plan or goals. There would be no strength to what you were doing.”

Parents employed a variety of metaphors to express a sense of sharing a difficult parenting journey.

So the two of us are really the ones that are making things happen and taking turns and so, yeah, it is just the motorbike has two wheels and with the other wheel it is pretty hard without it.

This sense of “both trying to head in the same direction” was an important factor in determining perceptions of coparenting competence by linking a sense of purpose and shared direction to their ability to keep their relationship working.

Other parents described how experiences of compromise and camaraderie on their parenting journey enhanced perceptions of solidarity: “We are closer because of Kevin. We work more closely together because of Kevin.” By relating their shared journey to parenting achievements the participants described a developing sense of coparenting competence “… we have come out as a better couple and I think that too has led to Arthur being probably a lot more passive, relaxed, so there is not as much stress in the family unit.”

Parents associated their sense of solidarity in their parenting partnership with perceptions of being on a shared parenting journey. They linked the sense of solidarity that they achieved through this shared journey to a developing perception of coparenting competence by describing connections between a sense of solidarity and their ability to make their parenting partnership work.

Communication, Cooperation and Coordination

Parents were motivated to cooperate in the coordination of their parenting activities in order to make their parenting partnership work, thereby enhancing their sense of coparenting competence. They described proactively cooperating to coordinate their parenting thinking and behaviours through communication: “We might discuss different views on something but we generally come to an agreement … we discuss it together and make sure we are both in agreement”.

However, participants also coordinated their parenting reactively, when it became apparent that either poor parental coordination was causing a problem, or a situation had arisen that required a coordinated response: “We kind of look at how we are going with respect [to] the children. … If they are not doing alright then we sit down and talk with each other about what we can do to help.”

These processes helped parents to understand each other’s thinking and find agreement about the distribution of parenting roles and responsibilities; a process that resulted in a specialisation and differentiation of parenting tasks that helped parents to achieve their parenting goals “… it can’t work here unless we share and differentiate the work.”

Communication, cooperation and coordination therefore helped to make the coparenting partnership “work” or prevented it from not working “… if we didn’t have those conversations to try and sort stuff out … then I think there would be a lot of conflict” and “We talk about it, that’s how we find out that we disagree.”

Communication played an important role in the coparenting partnership by enabling the differentiation and specialisation of parenting roles, the coordination of parenting thoughts and behaviours, an understanding of where disagreement existed, the ability to find agreement, and the capacity to come up with solutions to parenting problems. By linking their ability to cooperatively coordinate their parenting work through effective communication the participants provided further evidence of the pervasive nature of coparenting competence by describing how these factors contributed to their ability to make their parenting partnership work.

Managing Conflict and Antagonism

Although similar to the theme of communication, cooperation and coordination, conflict and antagonism are differentiated from other factors in coparenting models due to their negative influence on the quality of parenting partnerships. Data was referenced to this theme when parents described behaviours and thinking that helped them to manage discord and animosity that was likely to negatively impact on the quality of their parenting partnerships. Parents described the importance of respecting each other’s point of view, talking through disagreements when they were calm, avoiding disagreement in front of the children, and resisting the inclination to say hurtful things. They also spoke about the importance of accepting that there could be unresolved disagreement, and how valuable it was to have at least one partner who demonstrated the ability to yield and thereby minimise the risk of antagonism.

Parents described how they were able to talk through parenting disagreements to either reduce the risk that unresolved conflict would damage their parenting partnership or to “get it out in the open” so that they could understand each other “… they are good productive arguments so to speak. But it is more about trying to get it out in the open … and trying to understand where each other is coming from.”

Gender differences were evident when it came to behaviours associated with the management of conflict and disagreement. When asked, the greater majority (80%) of the parents indicated that one partner, almost always the mother, usually won in parenting disputes. Fathers, as previously found in Cowan and Cowan’s (2000) analysis of families with typically developing children, were more likely to acquiesce in order to reduce the frequency and intensity of conflict: “Look, even sometimes if I disagree, I just accept and move on so that there is no more argument.”

Further evidence of an ever-present sense of coparenting competence was provided by these descriptions of complimentary behaviours, where parents recognised the need to accept disagreement or the other’s authority, “I think when you disagree there is always someone that’s got to be the right person in the situation, someone whose decision you have to go with.” As well as regulating their own emotions to avoid or ameliorate conflict and antagonism so they could get on with the business of parenting. “Everyone has arguments and disagreements but we both want what’s best for our children, at the end of the day that’s the thing that keeps it working …”.

Partner Support

Partner Support is another key factor in multifactorial coparenting models. Data was referenced to partner support when parents described links between the supportive actions and behaviours of their partner and their own sense of parenting self-efficacy or their collective sense of coparenting competence.

When asked about her most important source of support, one mother simply said: “The Clive [her partner], definitely the Clive …” and this father linked the support that he received from his parenting partner to a global sense of competence “… there is a lot of trust between us and that helps in everything in life; parenting, your own relationship.”

More specifically the following parents described links between the support they received from their partner and their ability to parent well … “I could not do it without his support, or not do it well.” And “… he helps me and supports me in being a better mother.”

Perceptions of support were also related to parenting self-efficacy as parents illustrated how support kept them “on the right track” (F3) or how they “back[ed] each other up, no matter what” (M1). The confidence that these parents had in their partner’s support helped them to cope with the parenting of their child with an ASD: “Definitely knowing that you’re not in it alone. I have always had Michael to back me up or go to when I’ve been at that point where I just can’t cope.”

By linking perceptions of partner support to a sense of parenting self-efficacy, the parents in this sample were explicitly illustrating a reliance on partner support to fuel their parenting capability. By linking their sense of parenting self-efficacy to partner support these parents were implicitly referring to a sense of parenting competence that was driven by a collective contribution and could not exist outside of that relationship.

Shared Parenting

Shared parenting refers to a parent’s sense of equity (justness and fairness) in the way that parenting responsibilities are distributed in their parenting relationship (Van Egeren and Hawkins 2004). Data was coded to this theme when parents explicitly or implicitly indicated that parenting responsibilities were shared fairly or equitably.

Parents often described a parenting experience in which they were taking shared responsibility for their children when they were able to do so. Although the division of roles and responsibilities usually resulted in mothers doing most of the direct childcare, almost all parents in the sample described satisfaction with their partner’s parenting contribution. This satisfaction suggests that parents take factors, other than direct involvement, into account when making assessments of fairness and equity.

Despite doing the majority of direct care, mothers variously described their situation as “continuous teamwork”; their partner as doing an “excellent job” in his parenting role; or that their partner knew what needed to happen so that “the house runs effectively”. One mother gave an example of how her partner’s parenting support was ever-present, even though he was working elsewhere:

I think it’s great that he’s so supportive … sometimes like they’ll carry on at home and I’ll say look I’m going to ring Dad in a minute if you keep it up, and then I’ll ring him and he’ll talk to them on the phone.

This mother articulated a belief, as did others, that it was her specialist role to manage the children, that this was the natural order of things, and described how this role contributed to her authority in their parenting partnership:

“You know day to day women are the ones who run the families—so, mostly, like, men help and they’re great but … I am the one who has the most time with them and I know them better than anybody else” and “Arthur is now my area of expertise and … he [husband] kind of looks at it as though, well, yeah, ‘she is the kind of expert on our son’.”

Mothers and fathers illustrated the importance of both specialisation and accessibility in which parenting partners developed “area[s] of expertise” and helped each other out when they were best equipped to do so. They linked this complementary relationship to a sense of coparenting competence because these distributions of responsibility helped to make their parenting relationships work:

We do work well as a team and if I can’t cope any more I tend to go and have a shower and say to Pete ‘can you put Greg into bed tonight’ or ‘can you deal with the kids’ … So, yeah, we do work well as a team

I think we have a good balance … we’ve slipped into roles, for better or for worse, but they seem to work so that’s the way it will stay unless something pushes us out of those roles.

The links that parents made between their satisfaction with the way in which parenting was shared and the functionality of their partnership, provided further evidence of the pervasive presence of a sense of coparenting competence across factors used in models of coparenting quality.

Domain Three: Linking Coparenting Quality to Present and Future Developmental Outcomes

In this final domain of the analysis, parents revealed how important their parenting partnership was likely to be in determining developmental outcomes of their child with an ASD. Almost all of the parents (19/22) thought that the way that they worked together in their parenting partnership would have important influences on their child’s outcomes; with the remaining parents being unsure. Many parents described their experience and expectations of this association in broad terms such as:

“It is huge, it is everything” or “I don’t think he would have excelled as much as he has without the both of us; having both of us there. Yeah, parenting together … If we didn’t agree on what our goals were, and … have that understanding of roles … I don’t think Toby would have the opportunities to, um, develop.

While other parents described more specific expectations of the influence that their ability to work together would have on their child’s social and emotional development: “I think, seeing the relationship and the parenting partnership that we have has got to be a positive for him. It will help him to get a good job, help him to have normal relationships …” and another saying “You both need to be doing the same things with him at the same time. Otherwise he gets very confused.”

This link between parenting and social outcomes finds support in research on the development of emotion regulation; where parenting behaviours have been associated with the quality of children’s social and emotional development (Calkins and Hill 2007; Gross and Thompson 2007). One parent summarised this association by saying that “… having the knowledge, yeah, you’ve got to have the knowledge how to do it, but if you don’t have the teamwork then it is not going to work very well.”

Parents in this sample described perceptions of the association between their children’s present and future developmental achievements to the quality of their parenting partnership. By linking perceptions of collective parenting capability to their children’s development outcomes these parents have explicitly illustrated a sense of coparenting competence.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated evidence of a sense of coparenting competence in mothers and fathers of children with an ASD across the three domains of the coparenting experience: adapting to the emergence of autism in the child, the functioning of the coparenting relationships, and parents’ expectations of the influence that their parenting relationship would have on their child’s developmental outcomes.

In the first domain, it was found that the emergence of a child with an ASD served as a catalyst for parents to place greater value on the importance of their coparenting relationship and that this sense of value encouraged them to make their parenting partnership work. In the second domain, where parents talked about how their partnership was currently working, a sense of coparenting competence was found across communication, support, and conflict; factors that coparenting theorists have used to model the quality of coparenting relationships. In the third domain, parents described expectations that their coparenting competence would have a positive effect on their children’s developmental outcomes. The parents in this sample have therefore described a pervasive sense of coparenting competence that has influenced how they have coped in the past, how they are parenting now and how their parenting is likely to influence their children’s future development.

The concept of coparenting competence developed from this study is founded on Bandura’s (1977) theoretical analysis of human motivation in which he proposed that a common cognitive mechanism, perceptions of efficacy, serve as an important driver of human behaviour. Bandura hypothesised that expectations of efficacy will determine whether coping behaviours are initiated, how much effort will be expended in trying to cope, and how sustained the effort to cope will be. These hypotheses have now found support in systematic reviews of patient outcomes (e.g., Korpershoek et al. 2011) and more specifically in the arena of parenting self-efficacy (PSE) where Jones and Prinz (2005) found evidence of strong links between perceptions of PSE and actual parenting competence. These links between perceptions of efficacy and outcomes have spurred the development of a wide array of measures to assess the influence that intervention can have on both individual self-efficacy and collective efficacy in a range of contexts. Although Bandura (Bandura et al. 2011) developed a measure of marital efficacy this work has not yet been extended into the arena of coparenting.

The present study therefore plays an important role in describing a potential link between the collective sense of efficacy that parents feel in their parenting partnership, their ability to cope with adversity, and potential parenting outcomes. The analysis struck agreement with Hock’s et al. (2012) finding that parents re-evaluate and redistribute parenting roles and responsibilities in response to the emergence of their child’s ASD and that they also rely heavily on their coparenting relationship when adapting to the parenting of this child. Both mothers and fathers in the present study described pragmatic, business-like decisions about the distribution of parenting roles and responsibilities in order to make best use of their parenting resources. Participants also described how important their parenting relationship was and how they strived to make this relationship work in order to cope with the parenting of a child with an ASD and to help their child achieve optimal developmental outcomes. These adaptations and realisations may have particular implications for understanding and supporting parenting relationships in families trying to manage unforeseen parenting challenges such as the emergence of a child with an ASD.

The present study also found that perceptions of competence may be more salient than attempts to break the parenting partnership down into its constituent parts. For example, mothers and fathers in this study described satisfaction—another motivator of human behaviour—with the balance of parenting roles and responsibilities despite their evidence that one parent, usually the child’s mother, often took on primary responsibility for care of the child (Herzberg et al. 1966). This insight into expectations and fairness shows that parents take a range of subtle factors into account when assessing the quality of their parenting partnership. Previous reports have identified that discussions of equity and fairness in parenting relationships focusing on direct participation in care do not take into account other parenting activities—such as engagement, accessibility and responsibility—which an absent parent will often contribute (Hawkins and Palkovitz 1999). However, parents in the present study also described how they developed responsibility for different and specialised parenting roles in the manner that McHale et al. (2004) described as the ‘business of family commerce’; an adaptation that may have been enhanced by the demands of parenting a child with an ASD. The analysis found that a sense of coparenting competence sustained both maternal and paternal satisfaction despite disparities in involvement, knowledge and authority in their parenting partnerships.

Relations that parents in the present study illustrated between their sense of coparenting competence and key parenting indicators such as; their ability to cope, their capacity to manage parenting challenges, their satisfaction with parenting roles and responsibilities, and their hope for the future indicate that coparenting competence could be an important marker of coparenting quality. The pervasive presence of coparenting competence across the domains of this enquiry along with the importance that parents placed on this previously undescribed factor suggests that assessments of coparenting competence could play an important role in future coparenting research. Future studies should explore how coparenting competence can be effectively assessed to support a better understanding of relations between this factor and family outcomes.

Limitations

There are several limitations to consider regarding the implications of this study. The participants were generally well educated, reasonably prosperous parents and they were all biological, mixed gender, cohabitating parents of the child with an ASD. It is possible that parents from other socioeconomic circumstances or with different relationships with their children would describe their relationships in ways that did not link to perceptions of coparenting competence. While interviews asked about current experiences, for which recollections could be expected to be reasonably accurate, they also asked about memories of the past and expectations for the future. While expectations for the future are present day experiences the parents’ reflections on the past could be particularly unreliable, particularly for those experiencing high levels of distress associated with their child’s diagnosis. Although the code categories and eventual coding framework were discussed by the research team at regular time-points during the analysis data, gathered by phone, was coded by a single author. Future research could address these limitations with face-to-face interviews, use of multiple coders and applying the methodology in a larger sample. Alternatively, future studies could aim to gain a better understanding of coparenting competence by using longitudinal methods that explore the importance and relevance of this factor at key time points in the parents’ experience and how perceptions of coparenting competence change as children with ASD age into adulthood. Finally, parents in this study were asked about the experiences individually for fear that they may not feel free to express their opinions in their partner’s presence. Future studies could look to explore perceptions of coparenting competence in couple interviews to see if collective memories provide different insights.

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Bandura, A., Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Regalia, C., & Scabini, E. (2011). Impact of family efficacy beliefs on quality of family functioning and satisfaction with family life. Applied Psychology, 60(3), 421–448.

Belsky, J., Crnic, K., & Gable, S. (1995). The determinants of coparenting in families with toddler boys: Spousal differences and daily hassles. Child Development, 66(3), 629–642.

Bonds, D. D., & Gondoli, D. M. (2007). Examining the process by which marital adjustment affects maternal warmth: The role of coparenting support as a mediator. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(2), 288.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Brobst, J. B., Clopton, J. R., & Hendrick, S. S. (2009). Parenting children with autism spectrum disorders: The couple’s relationship. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24(1), 38–49.

Burton, P., Lethbridge, L., & Phipps, S. (2008). Children with disabilities and chronic conditions and longer-term parental health. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 37(3), 1168–1186.

Calkins, S. D., & Hill, A. (2007). Caregiver influences on emerging emotion regulation. Handbook of Emotion Regulation, 229248.

Cowan, C. P., & Cowan, P. A. (2000). When partners become parents: The big life change for couples. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Cowan, P. A., & Cowan, C. P. (2010). How working with couples fosters children’s development: From prevention science to public policy. In Strengthening family relationships for optimal child development: Lessons from research and intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Creswell, J. W., Plano Clark, V. L., & Garrett, A. L. (2008). Methodological issues in conducting mixed methods research designs. In E. M. M. Bergman (Ed.), Advances in mixed methods research (pp. 66–84). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Curran, A., Sharples, P., White, C., & Knapp, M. (2001). Time costs of caring for children with severe disabilities compared with caring for children without disabilities. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 43(8), 529–533.

Feinberg, M. E. (2003). The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting: Science and Practice, 3(2), 95–131.

Feinberg, M. E., Brown, L. D., & Kan, M. L. (2012). A multi-domain self-report measure of coparenting. Parenting, 12(1), 1–21.

Feinberg, M. E., Kan, M. L., & Hetherington, E. M. (2007). The longitudinal influence of coparenting conflict on parental negativity and adolescent maladjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(3), 687–702.

Fivas-Depeursinge, E., Lopes, F., Python, M., & Favez, N. (2009). Coparenting and toddler’s interactive styles in family coalitions. Family Process, 48(4), 500–516.

Gray, D. E. (1997). High functioning autistic children and the construction of “normal family life”. Social Science and Medicine, 44(8), 1097–1106.

Gray, D. E. (2003). Gender and coping: The parents of children with high functioning autism. Social Science and Medicine, 56(3), 631–642.

Groenendyk, A. E., & Volling, B. L. (2007). Coparenting and early conscience development in the family. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 168(2), 201–224.

Gross, J. J. & Thompson, R. A. (2007). Emotion regulation: Conceptual and empirical foundations. In J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of Emotion Regualtion (pp. 3–26). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82.

Hastings, R. P., Kovshoff, H., Ward, N. J., Degli Espinosa, F., Brown, T., & Remington, B. (2005). Systems analysis of stress and positive perceptions in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35(5), 635.

Hawkins, A. J., & Palkovitz, R. (1999). Beyond ticks and clicks: The need for more diverse and broader conceptualizations and measures of father involvement. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 8(1), 11–32.

Hayes, S. A., & Watson, S. L. (2013). The impact of parenting stress: A meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(3), 629–642.

Herzberg, F., Snyderman, B. B., & Mausner, B. (1966). The motivation to work (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Wiley.

Higgins, D. J., Bailey, S. R., & Pearce, J. C. (2005). Factors associated with functioning style and coping strategies of families with a child with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 9(2), 125–137.

Hock, R. M., Timm, T. M., & Ramisch, J. L. (2012). Parenting children with autism spectrum disorders: A crucible for couple relationships. Child and Family Social Work, 17(4), 406–415.

Jarrold, C., Boucher, J., & Smith, P. (1993). Symbolic play in autism: A review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 23(2), 281–307.

Jones, T. L., & Prinz, R. J. (2005). Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(3), 341–363.

Karreman, A., Van Tuijl, C., Van Aken, M. A., & Deković, M. (2008). Parenting, coparenting, and effortful control in preschoolers. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(1), 30.

Keen, D., Couzens, D., Muspratt, S., & Rodger, S. (2010). The effects of a parent-focused intervention for children with a recent diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder on parenting stress and competence. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(2), 229–241.

Kelly, A. B., Garnett, M. S., Attwood, T., & Peterson, C. (2008). Autism spectrum symptomatology in children: The impact of family and peer relationships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(7), 1069.

Keren, M., Feldman, R., Namdari-Weinbaum, I., Spitzer, S., & Tyano, S. (2005). Relations between parents’ interactive style in dyadic and triadic play and toddlers’ symbolic capacity. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 75(4), 599.

Kersh, J., Hedvat, T. T., Hauser-Cram, P., & Warfield, M. E. (2006). The contribution of marital quality to the well-being of parents of children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(12), 883–893.

Korpershoek, C., van der Bijl, J., & Hafsteinsdóttir, T. B. (2011). Self-efficacy and its influence on recovery of patients with stroke: A systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67(9), 1876–1894.

Levy, S., Mandell, D., & Schultz, R. (2009). Autism. The Lancet, 374, 1627–1638. doi:10.1016/S01406736(09)61376-3.

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2011). Designing qualitative research. Los Angeles: Sage.

Mason, M., & Pavia, T. (2006). When the family system includes disability: Adaptation in the marketplace, roles and identity. Journal of Marketing Management, 22(9–10), 1009–1030.

May, C., Fletcher, R., Dempsey, I., & Newman, L. (2014). The importance of coparenting quality when parenting a child with an autism spectrum disorder: A mixed method investigation. http://hdl.handle.net/1959.13/1049158.

McHale, J. P., & Kuersten-Hogan, R. (2004). Introduction: The dynamics of raising children together. New York: Springer.

McHale, J. P. (1995). Coparenting and triadic interactions during infancy: The roles of marital distress and child gender. Developmental Psychology, 31(6), 985.

McHale, J. P., Kuersten-Hogan, R., & Rao, N. (2004). Growing points for coparenting theory and research. Journal of Adult Development, 11(3), 221–234.

Mitchell, S. J., See, H. M., Tarkow, A. K., Cabrera, N., McFadden, K. E., & Shannon, J. D. (2007). Conducting studies with fathers: Challenges and opportunities. Applied Development Science, 11(4), 239–244.

Morrill, M., Hines, D. A., Mahmood, S., & Cordova, J. V. (2010). Pathways between marriage and parenting for wives and husbands: The role of coparenting. Family Process, 49(1), 59–73.

Morse, J. M. (2003). Principles of mixed methods and multimethod research design. Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research, 1, 189–208.

Pozo, P., Sarriá, E., & Brioso, A. (2014). Family quality of life and psychological well-being in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: A double ABCX model. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58(5), 442–458.

QSR International Pty Ltd. (2006). NVivo, Qualitative data analysis software. Version 7.

Roulston, K. (2010). Reflective interviewing: A guide to theory and practice. Los Angeles: Sage.

Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2003). Writing the proposal for a qualitative research methodology project. Qualitative Health Research, 13(6), 781–820.

Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Weldon, A. H., Claire Cook, J., Davis, E. F., & Buckley, C. K. (2009). Coparenting behavior moderates longitudinal relations between effortful control and preschool children’s externalizing behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(6), 698–706.

Smith, J. A., & Smith, J. (2003). Validity and qualitative psychology. In Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 232–235). Los Angeles: Sage.

Stryker, S. (1968). Identity salience and role performance: The relevance of symbolic interaction theory for family research. Journal of Marriage and The Family, 30(4), 558–564.

Teubert, D., & Pinquart, M. (2010). The association between coparenting and child adjustment: A meta-analysis. Parenting: Science and Practice, 10(4), 286–307.

Van Egeren, L. A. (2004). The development of the coparenting relationship over the transition to parenthood. Infant Mental Health Journal, 25(5), 453–477.

Van Egeren, L. A., & Hawkins, D. P. (2004). Coming to terms with coparenting: Implications of definition and measurement. Journal of Adult Development, 11(3), 165–178.

Author Contributions

CDM conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination and drafted the manuscript. JMSG participated in the design, interpretation of the data and preparation of the manuscript. RJF, ID and LKN participated in the design of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Implications for Clinical Practice

The development and application of measures to assess and monitor coparenting competence could have important implications for clinical practice. Applying measures of coparenting competence in clinical practice could lead to an understanding, founded in theory, of relations between coparenting competence and modes of intervention in families where parents are faced with the care of children with challenging developmental needs. This understanding could play an important role in guiding practice that helps parenting partnerships, regardless of their structure, to; make best use of their resources, cope with their child’s diagnosis, parent effectively, and sustain hope that their parenting will have a positive influence on their child’s developmental outcomes.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

May, C.D., St George, J.M., Fletcher, R.J. et al. Coparenting Competence in Parents of Children with ASD: A Marker of Coparenting Quality. J Autism Dev Disord 47, 2969–2980 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3208-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3208-z