Abstract

Mindfulness has been established as a critical psychosocial variable for the well-being of individuals; however, less is understood regarding the role of mindfulness within the family context of parents, coparents, and children. This study tested a model examining the process by which parent dispositional mindfulness relates to parenting and coparenting relationship quality through mindful parenting and coparenting. Participants were 485 parents (59.2 % mothers) from three community samples of families with youth across three developmental stages: young childhood (3–7 years; n = 164), middle childhood (8–12 years; n = 161), and adolescence (13–17 years; n = 160). Path analysis using maximum likelihood estimation was employed to test primary hypotheses. The proposed model demonstrated excellent fit. Findings across all three youth development stages indicated both direct effects of parent dispositional mindfulness as well as indirect effects through mindful parenting and mindful coparenting, with parenting and coparenting relationship quality. Implications for intervention and prevention efforts are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the last two decades, basic research grounded in family systems theory (e.g., Minuchin 1985; also see McHale and Lindahl 2011, for a review) is accumulating to document the importance of coparenting and the quality of the coparenting relationship in fully characterizing family life and its impact on parenting and child adjustment (Feinberg 2003). Conceptually, coparenting refers to the negotiation of a shared caregiving role between two adults as well as how the adults relate to one another in the context of childrearing (Feinberg 2003). From a family systems perspective (Cox and Paley 1997; Minuchin 1985; also see Cummings et al. 2000, for a review), family members are interdependent and their behaviors cannot be adequately understood by analyzing the individual or even a single dyad in isolation. Furthermore, family systems theory emphasizes the reciprocal influence that different family subsystems (e.g., individual, dyadic, family wide) potentially have on one another. One relevant exemplar of the multidirectional influences of different family subsystems is the “spillover hypothesis” (Erel and Burman 1995; see Krishnakumar and Buehler 2000, for a review), which posits that functioning in one subsystem (e.g., the parent individual subsystem) can impact functioning in another subsystem (e.g., the parent–child and/or the parent–coparent systems). One individual subsystem variable, parent dispositional mindfulness, can potentially spillover to affect the functioning of the parent–child and parent–coparent relationships; however, parent dispositional mindfulness has been understudied.

Mindfulness is defined as “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” (Kabat-Zinn 2003, p. 145). Further, dispositional mindfulness is defined as a person’s overall tendency to be mindful without the influence of mindfulness intervention or meditation practices. At the level of the individual, a vast body of research demonstrates that mindfulness is associated with improvements in physical and psychological health (e.g., Khoury et al. 2013) as well as greater self-efficacy, coping, emotion regulation, and motivation (e.g., Brown and Ryan 2003; Keng et al. 2011). Although mindfulness research to date primarily focuses on individual-level outcomes, theoretical and emerging empirical work suggests the importance of considering relational outcomes as well. For example, Kabat-Zinn (1991) proposed that mindfulness indirectly enhances interpersonal relationships via compassion for the self, which in turn leads to responsiveness to others. In fact, recent intervention research explores mindfulness within the context of the family. This research provides some preliminary support for positive effects of parental mindfulness on parent–child relationship quality (Coatsworth et al. 2010), parenting stress (Bazzano et al. 2015; Bögels et al. 2014; Haydicky et al. 2015), parenting practices (Bögels et al. 2014; Van der Oord et al. 2012), and coparenting relationship quality (Bögels et al. 2014).

Although still in its relative infancy, research is also beginning to demonstrate how dispositional mindfulness impacts parenting in a positive and powerful way. Mindful parenting, as described by Kabat-Zinn and Kabat-Zinn (1998) and conceptualized and measured by Duncan et al. (2009), extends the parenting literature by describing a constellation of behaviors characterized by intentionality in parental interactions with their children, which is evidenced by careful listening and attention, low reactivity, non-judgmental responses, emotional awareness, and compassion for the self and the child. Recent work has linked parent dispositional mindfulness to mindful parenting and, in turn, mindful parenting to the utilization of more adaptive parenting practices (Parent et al. 2015b).

Parent dispositional mindfulness is related to coparenting relationship quality (Bögels et al. 2014; Parent et al. 2014); however, mindfulness in coparenting has yet to be empirically investigated. Theoretically, individual mindfulness is conceptualized as enhanced coping (Kabat-Zinn 1991), when faced with managing stressful situations, such as parenting and coparenting. Thus, parents who are more mindful may be better able to approach their own and their coparent’s behaviors non-judgmentally and to effectively distance themselves from negative emotions (Dumas 2005); in turn, maladaptive emotional reactions may be diminished and promote consistent and intentional interactions between coparents. The mechanism for this action may be the reduction in habitual, or automatic, maladaptive reaction patterns, which in turn may reduce reliance on hostile and coercive interpersonal behaviors and increase positive patterns (e.g., expressions of warmth and clear communication) (Bögels and Resifo 2014; Dumas 2005; Duncan et al. 2009). Borrowing from the model of mindful parenting (Duncan et al. 2009), mindful coparenting involves parents’ skills in three areas: (1) maintenance of awareness and present-centered attention during coparenting interactions (e.g., not rushing through activities with the coparent without being really attentive to him/her), (2) demonstration of non-judgmental receptivity to their coparent’s articulation of thoughts and displays of emotion (e.g., listening carefully to the coparent’s ideas, even when they disagree with them), and (3) regulation of reactivity to the coparent’s behavior (e.g., when the parent is upset with the coparent, noticing how they are feeling before taking action). From this perspective, mindful coparenting sets the stage for an enhanced coparenting relationship through increasing the following behaviors: the likelihood and frequency of responding positively to coparenting relationship stress, empathy and acceptance toward one’s coparent, enhanced coparenting communication quality, and coparenting agreement, closeness, and support.

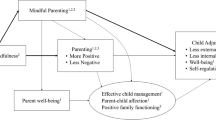

Based on conceptualizations by Bögels and Restifo (2014), Dumas (2005), Duncan et al. (2009), and Kabat-Zinn and Kabat-Zinn (1998), higher levels of parental dispositional mindfulness may facilitate positive family health through incorporating mindful awareness into parenting and coparenting interactions. In turn, these interactions can promote adaptive parenting behaviors (e.g., reductions in parental reactivity within parent–child interactions, increasing positive parenting practices) and coparenting relationship quality (e.g., increased coparenting agreement, closeness, and support and decreased coparenting conflict and undermining). Of note, facets of such a model have previously been examined and serve as preliminary data providing initial support for the paths in the extended model proposed here. For example, parental dispositional mindfulness is directly associated with mindful parenting (de Bruin et al. 2014; Parent et al. 2015b) and coparenting relationship quality (Parent et al. 2014). In turn, mindful parenting is linked with higher levels of positive (e.g., expressions of warmth and affection, facilitating supportive parent–child communication) and negative (e.g., reactive parenting, ineffective discipline) parenting practices (Duncan et al. 2015; Parent et al. 2015b). Further, parental dispositional mindfulness is indirectly associated with positive and negative parenting practices (e.g., Parent et al. 2010, 2015b).

The current investigation builds upon these individual studies, as well as the conceptualization noted previously (e.g., Dumas 2005), by investigating proposed associations in a single model: Higher levels of parent dispositional mindfulness are associated with higher levels of positive parenting and coparenting relationship quality and lower levels of negative parenting through mindful parenting and coparenting. The model is first examined in the full sample and subsequently by comparing subgroups of families with children at different developmental stages: young childhood (3–7 years), middle childhood (8–12 years), and adolescence (13–17 years). These age groups were chosen a priori based on typical age divisions of prevention and intervention programs that involve parenting as a primary component (e.g., McMahon and Forehand 2003; Kazdin 2005; Patterson and Forgatch 2005). Based on previous research (Parent et al. 2015a, b), we hypothesize and test that the paths in the current model would be equivalent for families regardless of youth developmental stage.

Method

Participants

Parents were recruited online through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) as part of a larger study on the assessment of parenting (N = 615). MTurk is currently the dominant crowdsourcing application in social sciences (Chandler et al. 2014), and prior research has convincingly demonstrated that data obtained via crowdsourcing methods are as reliable as those obtained via more traditional data collection methods (e.g., Buhrmester et al. 2011; Casler et al. 2013; Paolacci and Chandler 2014; Shapiro et al. 2013). For the current study, 488 parents who identified a coparent were included in the analyses. A coparent was defined as another adult (relative or non-relative, family member or not) who is integrally involved in sharing and coordinating daily childrearing activities for the target child.

Parents were, on average, 36.3 years old (SD = 7.8) with 59.2 % being mothers. Participants were predominately White (79.5 %) with an additional 10 % who identified as Black, 5.3 % as Latino, 3.9 % as Asian, and 1.2 % as American Indian, Alaska Native, or other Pacific Islanders. Parents’ education level ranged from no high school (HS) degree (.4 %), obtaining a HS degree or GED (12.7 %), attending some college (29.7 %), earning a college degree (41.6 %), to attending at least some graduate school (15.6 %). Reported family income ranged from under $5000 a year to over $100,000 a year with 19.5 % making less than $30,000 per year, 16 % making between $30,000 and $40,000, 12.5 % making between $40,000 and $50,000, 10 % making between $50,000 and $60,000, 27.7 % making between $60,000 and $100,000, and 14.3 % making at least $100,000. Parent marital status was organized into three categories with 6 % reporting being single (not living with a romantic partner), 74 % being married, and 20 % being in a cohabiting relationship (living with a romantic partner but not married). Most identified coparents lived in the home (92 %) and were a biological or stepparent (95.5 %) with a little over half being male (57.2 %). Other coparents included grandparents (2.5 %), aunts or uncles (1.2 %), and female (.6 %) or male (.2 %) family friends. Target youth was, on average, 9.53 years old [young childhood (3–7 years; n = 164), middle childhood (8–12 years; n = 161), and adolescence (13–17 years; n = 163)], and nearly half of youth was female (44.1 %).

Procedure

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Vermont. All parents consented online before beginning the survey in accordance with the approved IRB procedures. Parents were compensated $4.00 for participation. For families with multiple children in the target age range, one child was randomly selected through a computer algorithm while parents were taking the survey and measures were asked in reference to parenting practices specific to the identified child. Participants were recruited from MTurk under the restriction that they were US residents and had at least a 95 % task approval rate for their previous tasks. Ten attention check items were placed throughout the online survey. These questions asked participants to enter a specific response such as “Please select the Almost Never response option” that changed throughout the survey appearing in random order within other survey items. Participants (N = 2) were not included in the study (i.e., their data removed from the dataset) if they had more than one incorrect response to these 10 check items to ensure that responses were not random or automated.

Measures

Demographic Information

Parents responded to demographic questions about themselves (e.g., parental age, education), their families (e.g., household income), and the target child (e.g., gender, age).

Parent Dispositional Mindfulness

Parents completed the 15-item Mindfulness Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown and Ryan 2003). The MAAS is a scale that reflects a respondent’s global experience of mindfulness in addition to specific daily experiences that include “…awareness of and attention to actions, interpersonal communication, thoughts, emotions, and physical states” (Brown and Ryan 2003, p. 825). Participants indicated how frequently they had the experience described in each statement (e.g., “I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present”). Statements were scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost always) to 6 (almost never). Higher scores reflect higher levels of mindfulness. Mean levels of the MAAS in the current sample were comparable to those in the community samples without prior mindfulness training (e.g., Mackillop and Anderson 2007) and higher than those obtained in a sample of parents with a history of depression (Parent et al. 2010). The MAAS has demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .80–.90) as well as convergent and discriminant validity (Brown and Ryan 2003). The alpha coefficient in the current sample was .92.

Mindful Parenting

The Interpersonal Mindfulness in Parenting Scale (IMPS; Duncan, Assessment of mindful parenting among parents of early adolescents: Development and validation of the interpersonal mindfulness in parenting scale, unpublished dissertation) consisted of 8 items reflecting parents’ ability to maintain (1) awareness and present-centered attention during parent–child interactions (e.g., reversely coded: “I rush through activities with my child without being really attentive to him/her”), (2) non-judgmental receptivity to their child’s articulation of thoughts and displays of emotion (e.g., “I listen carefully to my child’s ideas, even when I disagree with them”), and (3) the ability to regulate their reactivity to their children’s behavior (e.g., “When I’m upset with my child, I notice how I am feeling before I take action”). Parents responded to each item on a 5-point Likert rating scale with higher scores reflecting higher levels of mindful parenting. Previous studies have demonstrated the concurrent and discriminant validity of the IMPS (e.g., de Bruin et al. 2014; Coatsworth et al. 2010). Mean levels of the IMPS in the current sample were comparable to those in the community sample from the original validation sample (Duncan, unpublished dissertation). The reliability for this scale in the current study was .79. The 2-week test–retest reliability in the current sample was strong (r = .74, p < .001).

Mindful Coparenting

The Interpersonal Mindfulness in Coparenting Scale (IMCS) was created for this study and consisted of 8 items adapted from the original IMPS (Duncan, unpublished dissertation) reflecting parents’ ability to maintain (1) awareness and present-centered attention during coparenting interactions (e.g., reversely coded: “I rush through activities with my coparent without being really attentive to him/her”), (2) non-judgmental receptivity to their coparent’s articulation of thoughts and displays of emotion (e.g., “I listen carefully to my coparent’s ideas, even when I disagree with them”), and (3) the ability to regulate reactivity to their coparents’ behavior (e.g., “When I’m upset with my coparent, I notice how I am feeling before I take action”). Parents responded to each item on a 5-point Likert rating scale with higher scores reflecting higher levels of mindful coparenting. A confirmatory factor analytic measurement model for the IMCS was estimated prior to estimating structural models in order to test the fit of the factor structure of the IMCS and to determine the factor loadings for each item. A single-factor model demonstrated acceptable fit [χ 2 (18, N = 488) = 70.3, p < .01, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .08, 95 % confidence interval (CI) .06–.10, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = .94, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = .05]. Item loadings were all significant (p < .001) and ranged from .38 to .80. The reliability for total score in the current study was good (α = .83). The 2-week test–retest reliability in the current sample was strong (r = .76, p < .001). See Table 3 in the Appendix for the complete scale.

Positive and Negative Parenting Practices

The positive parenting subscale of the Multidimensional Assessment of Parenting Scale (MAPS; Parent and Forehand 2015) was used for the current study. MAPS items were selected and adapted from several well-established parenting scales: the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ; Frick 1991), the Parenting Practices Questionnaire (PPQ; Block 1965; Robinson et al. 1995), the Parenting Scale (PS; Arnold et al. 1993), the Management of Children’s Behavior Inventory (MCBS; Pereppletchikova and Kazdin 2004), the parent report version of the Children’s Report of Parenting Behavior Inventory (CRPBI; Schaefer 1965; Schludermann, and Schludermann 1988), the Parent Behavior Inventory (PBI; Lovejoy et al. 1999), the Parenting Young Children scale (PARYC; McEachern et al. 2012), and the Parental Monitoring scale (PM; Stattin and Kerr 2000). Initial reliability and validity data for the MAPS are favorable (Parent et al. 2015a, b).

The 11-item positive parenting subscale included items representing expressions of warmth and affection (e.g., “I express affection by hugging, kissing, and holding my child”), use of positive reinforcement (e.g., “If I give my child a request and she/he carries out the request, I praise her/him for listening and complying”), use of clear instructions [e.g., “I give reasons for my requests” (such as “We must leave in five minutes, so it’s time to clean up”)], and facilitation of supportive parent–child communication (e.g., “I encourage my child to talk about her/his troubles”). The 7-item negative parenting subscale included items representing reactive (e.g., “I lose my temper when my child doesn’t do something I ask him/her to do”) or intrusive parenting (e.g., “When I am upset or under stress, I am picky and on my child’s back”), coercive disciplinary tactics (e.g., “I yell or shout when my child misbehaves”), ineffective discipline (e.g., “I use threats as punishment with little or no justification”), and high levels of expressed hostility (e.g., “I explode in anger toward my child”). The positive and negative parenting subscales had an alpha coefficient of .88 and .84, respectively.

Coparenting Relationship Quality

The brief version of the Coparenting Relationship Scale (CRS; Feinberg et al. 2012) assessed coparenting relationship quality. The CRS assesses five domains of coparenting based on theory and prior research (Feinberg 2003): (1) coparenting agreement, (2) coparenting support/undermining, (3) coparenting conflict in front of the child, (4) division of labor, and (5) coparenting closeness. The brief CRS scale is an excellent approximation of the full CRS scale, with a correlation of .97 for mothers and .94 for fathers, and has good reliability (Feinberg et al. 2012). Item content was adjusted from referring to a partner to referring to a coparent to allow the measure to be applicable to parents who did not identify their romantic partner as the primary coparent. The alpha coefficient for the full scale in the current study was .78.

Data Analytic Plan

Preliminary Analysis of Demographic and Study Variables

The effect of categorical (e.g., youth gender) and continuous demographic (e.g., parent age) variables on the primary outcomes was examined using bivariate correlations. If significant associations emerged between demographic variables and primary model variables, those demographic variables were further examined in multiple-indicator, multiple-cause (MIMIC) models (see the next section).

Evaluation of the Structural Model

In order to test the hypothesized structural model, a path analysis was conducted with Mplus 6.0 software (Muthen and Muthen 2010). To account for skewed data, maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR) was used. The following fit statistics were employed to evaluate model fit [chi-square (χ 2): p > .05 excellent, CFI (>.90 acceptable, >.95 excellent), RMSEA (<.08 acceptable, <.05 excellent), SRMR (<.08 acceptable, <.05 excellent)] (Hu and Bentler 1999). As missing data were less than 1 % overall for all core variables, the mechanism of missingness was treated as ignorable (missing at random) and full information maximum likelihood estimation techniques were used for inclusion of all available data. Multiple-group path analysis was employed to examine and test whether differences in the structural parameters across the three developmental stages were statistically significant. Testing for cross-group invariance involved comparing two nested models: (1) a baseline model wherein no constraints were specified and (2) a second model where all paths were constrained to be invariant between the three developmental stages. The use of the MLR estimator required the use of a scaled chi-square difference test (Satorra 2000) for making key comparisons among nested models.

Given that the authors did not theorize that the proposed associations would vary based on demographics of the family (i.e., parent gender, race/ethnicity), these variables were not included in the conceptual model or study hypotheses. To confirm the appropriateness of this approach, however, the effects of these variables on the model were examined by running a MIMIC (Muthen 1989) model in which all major constructs of the final structural model were regressed on the covariates separately. If paths in the structural model remained significant with the inclusion of these covariates, it was concluded that the control variables did not influence the relationships among the variables in the model. Additionally, to test the significance of the indirect effect, the model indirect command in Mplus was used to calculate a standardized indirect effect parameter and bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals. Additionally, the indirect effect-to-the total effect ratio (ab/c; Preacher and Kelley 2011) for each significant indirect effect test was calculated.

Results

All bivariate correlations among study variables were significant and in the expected directions (see Table 1). Prior to analyses, three demographic variables were dichotomized based on sample size in groups and inspection of the means. Race was dichotomized to White (1) or person of color (2), marital status was dichotomized to single (1) or in a relationship (2), and parent education was dichotomized to some college or less (1) or college degree or more (2).

None of the study variables significantly differed by parent race, parent education, or youth gender. Therefore, these variables were not controlled for in the primary analyses. Parent gender was negatively correlated with positive parenting (p < .001) and positively correlated with coparenting (p < .05) such that mothers reported lower levels of positive parenting and higher levels of coparenting relationship quality than fathers. Marital status was positively correlated with parent dispositional mindfulness, mindful coparenting, and coparenting relationship quality (all ps < .05) such that single parents reported lower levels on all constructs. Thus, for the primary analyses, parent gender and marital status served as covariates in MIMIC models.

The first step of the primary analyses involved testing a model with zero degrees of freedom. Given the findings of prior work (Parent et al. 2010, 2015b), a link between parent dispositional mindfulness and positive parenting was not predicted and was not obtained here. Thus, that path was dropped from the model in order to ascertain model fit. The final model demonstrated excellent fit [χ 2 (1, N = 488) = .06, p > .15, RMSEA = .00, 95 % CI .00–.075, CFI = 1.0, SRMR = .002] and is displayed in Fig. 1. The standardized estimates of direct and indirect effects are presented in Table 2 along with bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals for all effects in the model. Next, multiple-group path analysis was employed to examine and test whether differences in the structural parameters across the three developmental stages were statistically significant. Model fit did not significantly deteriorate when all paths were constrained to be invariant across the three developmental stages [∆ χ 2 (30) = 34.75, p > .10], which suggests that the more parsimonious single-group model is preferred (i.e., associations in the model were equivalent across the three developmental stages). MIMIC models tested the demographic effects of parent gender and marital status on the associations in the final model. All the major constructs of the final model were regressed on the control variables simultaneously. All paths in the structural model were largely unaffected by the inclusion of these control variables (i.e., no change in significant, direction, and only minor changes in effect size); thus, it was concluded that the control variables did not influence the original relationships among variables in the model.

As predicted, higher levels of parental dispositional mindfulness were associated with higher levels of mindful parenting, mindful coparenting, negative parenting, and coparenting relationship quality. Next, consistent with hypotheses, higher levels of mindful parenting were related to higher levels of positive parenting practices and lower levels of negative parenting practices. Contrary to hypotheses, higher levels of mindful parenting were not related to coparenting relationship quality. As predicted, higher levels of mindful coparenting related to higher levels of coparenting relationship quality.

With regard to indirect effects, parental dispositional mindfulness was indirectly related to positive and negative parenting practices through mindful parenting, but not through mindful coparenting. The indirect effect-to-the total effect ratio for parent dispositional mindfulness on positive and negative parenting was 96 and 24 %, respectively. Furthermore, parent dispositional mindfulness was indirectly related to coparenting relationship quality through mindful coparenting, but not through mindful parenting. The indirect effect-to-the total effect ratio for parent dispositional mindfulness on coparenting relationship quality was 65 %. All indirect effects were statistically significant.

Discussion

This study extended the previous mindful parenting literature to additional facets of the family system. In doing so, we tested a theoretical model informed by the spillover hypothesis, investigating the process by which parent dispositional mindfulness relates to positive and negative parenting practices and adaptive coparenting relationship quality through mindful interactions with children (i.e., mindful parenting) and coparents (i.e., mindful coparenting). The hypothesized model was largely supported. Parental dispositional mindfulness was indirectly related to both parenting and coparenting, but to each through a unique process.

Also, parent dispositional mindfulness was directly associated with negative, but not positive, parenting which is a finding congruent with past investigations with different samples (e.g., Parent et al. 2010, 2014, 2015b). Further, in line with previous research (Parent et al. 2015b), higher levels of dispositional parental mindfulness were indirectly related to higher levels of positive parenting practices and lower levels of negative parenting practices through higher levels of mindful parenting. A consistent picture is emerging that suggests that the process by which parent attunement and attention to the present moment in general aspects of daily life impacts parenting is through compassion, reduced reactivity, and increased awareness specifically in the context of the parent–child relationship. It is possible that without this transfer of a mindful disposition to the context of the parent–child interaction, the impact of the disposition on parenting may be lost.

As in prior research (Parent et al. 2014), higher levels of parent dispositional mindfulness were directly related to coparenting relationship quality (e.g., higher levels of coparenting agreement, coparenting support/undermining, coparenting closeness and lower levels of coparenting conflict). Novel to the current investigation, higher levels of dispositional parent dispositional mindfulness were indirectly related to coparenting relationship quality through mindful coparenting. Spillover effects (i.e., mindful parenting to coparenting relationship quality and mindful coparenting to parenting) were not supported for either domain, although there was a significant correlation between mindful parenting and coparenting. The absence of these associations may suggest that mindful parenting and mindful coparenting are unique family subsystems that are linked to different outcomes. Future research on mindfulness and family systems should include both constructs and examine their associations with multiple outcomes longitudinally in order to better capture potential spillover effects. Finally, using multiple-group models, we found that the above processes were equivalent across youth developmental stages. This finding suggests universal applicability and generalizability of our model across the development of children and adolescents (i.e., ages ranging from 3 to 17).

As with all research, this study has limitations. First, the data are cross-sectional, raising questions about the direction of effects and temporal precedence that are better addressed by longitudinal designs. Caution is warranted when interpreting causal pathways in the current model, and future research examining similar questions should use longitudinal and/or experimental designs. Second, due to the crowdsourcing methodology, all variables in the model were from a single reporter. As this potentially introduces the issue of shared method variance, the use of multiple reporters on constructs of interest could strengthen confidence of findings in future work. Third, the current sample was primarily White, educated, and middle or upper income, leaving open to question the generalizability of the findings to more diverse families. Fourth, the current investigation assessed only one facet of mindfulness. Future work should examine the influence of multiple facets of mindfulness (e.g., observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience, and non-reactivity to inner experience) on parenting and coparenting. Lastly, we did not explicitly assess mindfulness practices (i.e., meditation) or prior mindfulness training. Future research should examine whether experimentally increasing parents’ mindfulness results in enhanced parenting and coparenting. An interesting question for future research is whether individual programs such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (Segal et al. 2002) or mindfulness-based stress reduction (Kabat-Zinn 1991) indirectly result in improvements in parenting and coparenting or if a specific mindfulness-based family program is necessary to generate such effects.

The current study also had several significant strengths that should be noted. First, we examined the proposed model across children in three distinct developmental stages and the findings were replicated across stages. Furthermore, the sample was constituted by over 45 % father participants, a group which is most often underrepresented in clinical child and adolescent research (Phares 1992; Phares et al. 2005). Such a developmentally informed approach with a large sample of mothers and fathers enhances the confidence in our findings regarding potential mechanisms of interest and extends their generalizability to broader family contexts and child developmental stages. Finally, the current study is the first to examine the construct of mindful coparenting and we hope that this initial investigation prompts further inquiry and conceptualization of this novel construct.

Although basic research has begun to examine the role of coparents in both the relationship quality and parenting, the applied literature has lagged behind, with most interventions targeting one or the other, but not both (Sanders et al. 1997; for an exception, see Zemp et al. 2015). Feinberg (2003) proposed that one barrier to integrating both into interventions was the absence of a conceptualization that clearly linked the two areas. Both his conceptual model and the current empirical model highlight parental adjustment (e.g., mindfulness), child characteristics (e.g., age), the interparental relationship, coparenting, and parenting, all of which provide a solid foundation for linking relationship quality and parenting interventions.

In regard to clinical implications, programs targeting mindful parenting demonstrate improvements in mindful parenting, the parent–youth relationship, the coparenting relationship, and parenting practices (e.g., Bögels et al. 2014; Coatsworth et al. 2010). Our findings provide support for the importance of such interventions by demonstrating the significant associations between potential intervention targets, like parent mindfulness, and important outcomes like parenting and coparent across children at distinct developmental stages. In addition, our findings suggest that such therapeutic approaches may benefit families by also teaching mindful parenting and mindful coparenting specifically, as they are associated with differential outcomes. For example, mindful parenting programs might benefit from including coparents into the intervention and using interparental mindfulness exercises. These exercises can be implemented to support relationship satisfaction (e.g., mindful listening) and improve parenting interactions (e.g., practicing interpersonal mindfulness skills during a difficult parenting conversation or conflict). Finally, future research will strengthen our understanding of mindfulness in the family context by extending the extant framework to include additional variables and processes such as parental psychopathology, child adjustment, and extrafamilial influences (e.g., economic stress) as well as how child evocative practices impact mindful parenting.

References

Arnold, D. S., O’Leary, S. G., Wolff, L. S., & Acker, M. M. (1993). The Parenting Scale: a measure of dysfunctional parenting in discipline situations. Psychological Assessment, 5(2), 137–144. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.137.

Bazzano, A., Wolfe, C., Zylowska, L., Wang, S., Schuster, E., Barrett, C., & Lehrer, D. (2015). Mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) for parents and caregivers of individuals with developmental disabilities: a community-based approach. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(2), 298–308. doi:10.1007/s10826-013-9836-9.

Block, J. H. (1965). The child-rearing practices report (CRPR): a set of Q items for the description of parental socialization attitudes and values. Unpublished Manuscript, Institute of Human Development, University of California, Berkeley.

Bögels, S. M., Hellemans, J., van Deursen, S., Römer, M., & van der Meulen, R. (2014). Mindful parenting in mental health care: effects on parental and child psychopathology, parental stress, parenting, coparenting, and marital functioning. Mindfulness, 5(5), 536–551. doi:10.1007/s12671-013-0209-7.

Bögels, S., & Restifo, K. (2014). Mindful parenting. New York: Springer.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822.

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: a new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–5. doi:10.1177/1745691610393980.

Casler, K., Bickel, L., & Hackett, E. (2013). Separate but equal? A comparison of participants and data gathered via Amazon’s MTurk, social media, and face-to-face behavioral testing. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2156–2160. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.05.009.

Chandler, J., Mueller, P., & Paolacci, G. (2014). Nonnaïveté among Amazon Mechanical Turk workers: consequences and solutions for behavioral researchers. Behavior Research Methods, 46(1), 112–130. doi:10.3758/s13428-013-0365-7.

Coatsworth, J. D., Duncan, L. G., Greenberg, M. T., & Nix, R. L. (2010). Changing parent’s mindfulness, child management skills and relationship quality with their youth: results from a randomized pilot intervention trial. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(2), 203–217. doi:10.1007/s10826-009-9304-8.

Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (1997). Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 243–267. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243.

Cummings, E. M., Davies, P. T., & Campbell, S. B. (2000). Developmental psychopathology and family process: theory, research, and clinical implications. New York: Guilford.

De Bruin, E. I., Zijlstra, B. J. H., Geurtzen, N., van Zundert, R. M. P., van de Weijer-Bergsma, E., Hartman, E. E., & Bögels, S. M. (2014). Mindful parenting assessed further: psychometric properties of the Dutch version of the Interpersonal Mindfulness in Parenting Scale (IM-P). Mindfulness, 5(2), 200–212. doi:10.1007/s12671-012-0168-4.

Dumas, J. E. (2005). Mindfulness-based parent training: strategies to lessen the grip of automaticity in families with disruptive children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 34(4), 779–791. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3404_20.

Duncan, L. G., Coatsworth, J. D., Gayles, J. G., Geier, M. H., & Greenberg, M. T. (2015). Can mindful parenting be observed? Relations between observational ratings of mother–youth interactions and mothers’ self-report of mindful parenting. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(2), 276–282. doi:10.1037/a0038857.

Duncan, L. G., Coatsworth, J. D., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). A model of mindful parenting: implications for parent–child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12(3), 255–270. doi:10.1007/s10567-009-0046-3.

Erel, O., & Burman, B. (1995). Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 118(1), 108–132. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108.

Feinberg, M. E. (2003). The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: a framework for research and intervention. Parenting: Science and Practice, 3(2), 95–131. doi:10.1207/S15327922PAR0302_01.

Feinberg, M. E., Brown, L. D., & Kan, M. L. (2012). A multi-domain self-report measure of coparenting. Parenting: Science and Practice, 12(1), 1–21. doi:10.1080/15295192.2012.638870.

Frick, P. J. (1991). The Alabama parenting questionnaire. Unpublished rating scale, University of Alabama.

Haydicky, J., Shecter, C., Wiener, J., & Ducharme, J. M. (2015). Evaluation of MBCT for adolescents with ADHD and their parents: impact on individual and family functioning. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(1), 76–94. doi:10.1007/s10826-013-9815-1.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1991). Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Bantam Dell.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bpg016.

Kabat-Zinn, M., & Kabat-Zinn, J. (1998). Everyday blessings: the inner work of mindful parenting. Hyperion.

Kazdin, A. E. (2005). Parent management training: treatment for oppositional, aggressive, and antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. New York: Oxford University Press.

Keng, S.-L., Smoski, M. J., & Robins, C. J. (2011). Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: a review of empirical studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 1041–1056. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006.

Khoury, B., Lecomte, T., Fortin, G., Masse, M., Therien, P., Bouchard, V., & Hofmann, S. G. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(6), 763–771. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005.

Krishnakumar, A., & Buehler, C. (2000). Interparental conflict and parenting behaviors: a meta-analytic review. Family Relations, 49(1), 25–44. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2000.00025.x.

Lovejoy, M. C., Weis, R., O’Hare, E., & Rubin, E. C. (1999). Development and initial validation of the Parent Behavior Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 11(4), 534–545. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.11.4.534.

MacKillop, J., & Anderson, E. J. (2007). Further psychometric validation of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 29(4), 289–293. doi:10.1007/s10862-007-9045-1.

McEachern, A. D., Dishion, T. J., Weaver, C. M., Shaw, D. S., Wilson, M. N., & Gardner, F. (2012). Parenting Young Children (PARYC): validation of a self-report parenting measure. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(3), 498–511. doi:10.1007/s10826-011-9503-y.

McHale, J. P., & Lindahl, K. M. (2011). Coparenting: a conceptual and clinical examination of family systems. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

McMahon, R. J., & Forehand, R. (2003). Helping the noncompliant child (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

Minuchin, P. (1985). Families and individual development: provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Development, 56(2), 289–302. doi:10.2307/1129720.

Muthén, B. O. (1989). Latent variable modeling in heterogeneous populations. Psychometrika, 54(4), 557–585. doi:10.1007/BF02296397.

Muthen, L. K., & Muthen, B. O. (2010). Mplus user’s guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen.

Paolacci, G., & Chandler, J. (2014). Inside the Turk: understanding Mechanical Turk as a participant pool. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(3), 184–188. doi:10.1177/0963721414531598.

Parent, J., Clifton, J., Forehand, R., Golub, A., Reid, M., & Pichler, E. R. (2014). Parental mindfulness and dyadic relationship quality in low-income cohabiting black stepfamilies: associations with parenting experienced by adolescents. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 3(2), 67–82. doi:10.1037/cfp0000020.

Parent, J., Forehand, R. L. (2015). Multidimensional Assessment of Parenting Scale (MAPS). Unpublished rating scale, University of Vermont.

Parent, J., Garai, E., Forehand, R., Roland, E., Potts, J., Haker, K., & Compas, B. E. (2010). Parent mindfulness and child outcome: the roles of parent depressive symptoms and parenting. Mindfulness, 1(4), 254–264. doi:10.1007/s12671-010-0034-1.

Parent, J., McKee, L. G., & Forehand, R. (2015a). Seesaw discipline: the interactive effect of harsh and lax discipline on youth psychological adjustment. Journal of Child and Family Studies. doi:10.1007/s10826-015-0244-1.

Parent, J., McKee, L. G. N., Rough, J., & Forehand, R. (2015b). The association of parent mindfulness with parenting and youth psychopathology across three developmental stages. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. doi:10.1007/s10802-015-9978-x.

Patterson, G. R., & Forgatch, M. S. (2005). Parents and adolescents living together: family problem solving. Eugene: Research.

Perepletchikova, F., & Kazdin, A. E. (2004). Assessment of parenting practices related to conduct problems: development and validation of the Management of Children’s Behavior Scale. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 13(4), 385–403. doi:10.1023/B:JCFS.0000044723.45902.70.

Phares, V. (1992). Where’s poppa? The relative lack of attention to the role of fathers in child and adolescent psychopathology. American Psychologist, 47(5), 656–664. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.47.5.656.

Phares, V., Fields, S., Kamboukos, D., & Lopez, E. (2005). Still looking for Poppa. American Psychologist, 60(7), 735–736. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.7.735.

Preacher, K. J., & Kelley, K. (2011). Effect size measures for mediation models: quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological Methods, 16(2), 93–115. doi:10.1037/a0022658.

Robinson, C. C., Mandleco, B., Olsen, S. F., & Hart, C. H. (1995). Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: development of a new measure. Psychological Reports, 77(3), 819–830. doi:10.2466/pr0.1995.77.3.819.

Sanders, M. R., Nicholson, J. M., & Floyd, F. J. (1997). Couples’ relationships and children. In W. K. Halford & H. J. Markman (Eds.), Clinical handbook of marriage and couples interventions (pp. 225–253). Hoboken: Wiley.

Satorra, A. (2000). Scaled and adjusted restricted tests in multi-sample analysis of moment structures. In R. D. H. Heijmans, D. S. G. Pollock, & A. Satorra (Eds.), Innovations in multivariate statistical analysis (pp. 233–247). USA: Springer.

Schaefer, E. S. (1965). Children’s reports of parental behavior: an inventory. Child Development, 36(2), 413. doi:10.2307/1126465.

Schludermann, S., Schludermann, E. (1988). Questionnaire for children and youth (CRPBI-30). Unpublished manuscript, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg

Segal, Z., Williams, M., & Teasdale, J. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: a new approach to preventing relapse: book review. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 31(4), 193–194.

Shapiro, D. N., Chandler, J., & Mueller, P. A. (2013). Using Mechanical Turk to study clinical populations. Clinical Psychological Science, 1(2), 213–220. doi:10.1177/2167702612469015.

Stattin, H., & Kerr, M. (2000). Parental monitoring: a reinterpretation. Child Development, 71(4), 1072–1085. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00210.

Van der Oord, S., Bögels, S. M., & Peijnenburg, D. (2012). The effectiveness of mindfulness training for children with ADHD and mindful parenting for their parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(1), 139–147. doi:10.1007/s10826-011-9457-0.

Zemp, M., Milek, A., Cummings, E. M., Cina, A., & Bodenmann, G. (2015). How couple- and parenting-focused programs affect child behavioral problems: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child and Family Studies. doi:10.1007/s10826-015-0260-1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This research was supported by the Child and Adolescent Psychology Training and Research, Inc. (CAPTR). The first author is supported by the NICHD (F31HD082858). The fourth author is supported by the NIMH (R01MH100377-S1). The third, fifth, and sixth authors are supported by the NIMH (R01MH100377). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Parent, J., McKee, L.G., Anton, M. et al. Mindfulness in Parenting and Coparenting. Mindfulness 7, 504–513 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0485-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0485-5