Abstract

The current study explored the longitudinal relation between parental expressed emotion, a well-established predictor of symptom relapse in various other disorders (e.g., schizophrenia) with externalizing behaviors in 84 children, ages 8–18 (at Time 2), with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). It was found that parental expressed emotion, specifically criticism/hostility at Time 1, significantly related to a change in externalizing behaviors from Time 1 to Time 2, even after controlling for Time 1 family income, ASD symptom severity, parental distress, and parenting practices. That is, higher levels of parental criticism/hostility at Time 1 predicted higher levels of child externalizing behaviors at Time 2. However, the reverse was not found. This finding of a unidirectional relation has important clinical implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Families of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) experience unique challenges (e.g., how to manage maladaptive, dangerous, and aggressive behaviors; how to teach adaptive skills; Matson and Nebel-Schwalm 2007). Of interest to the current study are the externalizing behaviors exhibited by children and adolescents with ASD. These behaviors include tantrums (that may last hours), aggression (hitting, kicking, pinching, biting), property destruction, not following directions (noncompliance), and elopement (Mahan and Matson 2011; Totsika et al. 2011). The current study seeks to build off of previous studies examining the longitudinal relation between parental expressed emotion and externalizing behaviors in children and adolescents with ASD by examining outcomes approximately 2 years later for a subsample of participants from Bader et al. (2014)—a study that had originally examined these constructs cross-sectionally.

Expressed Emotion

According to Hooley and Gotlib (2000), expressed emotion is a measure of the extent that a family member of an individual with a disorder or disability talks about the individual in a critical or hostile way (criticism/hostility component) or in a way illustrating emotional over-concern or overinvolvement (emotional overinvolvement component). Thus, within the context of a family with a child with ASD, it is not a characteristic of the child with ASD, but rather a characteristic of the child’s family members. Whereas the construct of expressed emotion was initially established and explored within the schizophrenic population, it has also been explored in many other medical and clinical populations (e.g., those with depression, anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms, or behavior disorders). It has been consistently found that higher expressed emotion is linked to poorer outcomes (i.e., increases in problem behaviors, higher relapse rates, and smaller therapeutic gains while in treatment; Pharoah et al. 1999; Pitschel-Walz et al. 2001).

Parental Expressed Emotion and Externalizing Behaviors in Children and Adolescents with ASD

Bader et al. (2014) examined the relation between parental expressed emotion and externalizing behaviors in 111 children and adolescents with ASD, ages 6–18 years. To answer the question of whether the two components of parental expressed emotion (criticism/hostility and emotional overinvolvement) uniquely related to externalizing behaviors in children and adolescents with ASD, hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted, controlling for symptom severity of ASD, parental distress, positive parenting practices, negative parenting practices, and significantly-related demographic variables—which included child’s age, parent’s age, and total family income. The outcome variable was the externalizing behaviors composite scale from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach and Rescorla 2001). Results revealed that parental expressed emotion predicted significant unique variance in child externalizing behaviors (accounting for 18.7 % of the variance in child externalizing behaviors even after controlling for the demographics and other parenting variables). Furthermore, results indicated that parental criticism/hostility significantly and uniquely predicted child externalizing behaviors after controlling for all other variables (including parental emotional overinvolvement). However, parental emotional overinvolvement did not predict unique variance in child externalizing behaviors.

Overall, the results from Bader et al. (2014) indicated that parental expressed emotion—particularly the criticism/hostility component—relates to externalizing behaviors among children and adolescents with ASD. Establishing these relations, even when controlling for other parenting variables known to relate to child externalizing behaviors, provides a more rigorous test of the question of whether expressed emotion relates to externalizing behaviors among individuals with ASD and extends the findings to a more homogenous (ASD only) and younger population than much of the preceding research (i.e., Baker et al. 2011; Greenberg et al. 2006; Hastings et al. 2006).

Although the Bader et al. (2014) study, indicates a relation between parental expressed emotion and child externalizing behaviors in a homogeneous sample of children and adolescents with ASD, the question of the temporal sequencing of this relation remains unanswered. With the cross-sectional design of the study, it is not possible to conclude whether parental expressed emotion precedes child externalizing behaviors or whether child externalizing behaviors precedes parental expressed emotion. It also cannot be ascertained whether one can predict change in the other. Determining the temporal sequencing of these relations in a longitudinal design is imperative in an effort to provide further evidence for the theory that parental expressed emotion predicts child externalizing behaviors among children and adolescents with ASD. Because such knowledge has important causal implications, the necessary next step in this line of research is to examine these relations within a homogeneous sample of children and adolescents with ASD, in a longitudinal design, which was the purpose of the current study.

Current Study

The current study sought to replicate previous studies, which have found a unidirectional relation of parental expressed emotion predicting increased externalizing behaviors over time (i.e., Baker et al. 2011; Greenberg et al. 2006; Hastings et al. 2006), in a more homogeneous sample. More directly, the current study sought to build on the Bader et al. (2014) study, which established a relation between parental expressed emotion and externalizing behaviors in children and adolescents with ASD, by adding a second time point of data collection to examine the longitudinal relations and temporal sequencing of the constructs. It was hypothesized that parental expressed emotion, specifically criticism/hostility at Time 1, would significantly relate to a change in externalizing behaviors from Time 1 to Time 2, even after controlling for Time 1 severity of ASD symptoms, parental distress, parenting practices, and any demographic variables (e.g., child’s age) found to relate to Time 2 externalizing behaviors (i.e., the outcome). This relation was not predicted to hold in the opposite direction (i.e., when examining externalizing behaviors at Time 1 predicting change in parental expressed emotion at Time 2). In other words, it was hypothesized that children and adolescents with ASD living in family environments characterized by higher parental expressed emotion would display increasingly more severe externalizing behaviors over time than children living in lower expressed emotion families. Such a finding would establish the temporal sequencing of the relation found between parental expressed emotion and child externalizing behaviors in Bader et al. while taking into account other pertinent parenting variables (parental distress and parenting practices) that were not considered in previous longitudinal studies.

Method

Participants

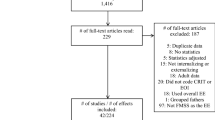

Data for the current study were collected from 84 parents of a child with ASD. These 84 parents were recruited from the sample of 111 parents who participated in the Bader et al. (2014) study, which was used as Time 1 for the current study. Time 2 data collection occurred from 1.34 to 2.28 years later (M = 2.12, SD = .13). Out of the 111 parents who participated in the study at Time 1, seven were not recruited for Time 2 data collection because their child was older than 18 years at the Time 2 data collection point, which was deemed too old for inclusion because of the norms available for the study measures. All families that participated at Time 1 consented to being contacted again for future studies and provided their contact information, and 100 % of the families targeted for recruitment at Time 2 were able to be reached to inform them of the Time 2 data collection. Of the 104 parents who were contacted for Time 2 data collection, one parent expressed that she did not wish to participate, 15 parents agreed to participate when contacted but did not begin the questionnaires, and four parents began the study but did not complete the questionnaires.

To qualify for the study, the child or adolescent with ASD had to be currently living in the home with the family (i.e., did not live in a group home or residential facility). Using the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 2000) diagnostic criteria, a diagnosis of ASD was confirmed through parental data provided on the Demographic and Diagnostic Information Questionnaire, and 37 % were diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, 39 % with autism, and 24 % with pervasive developmental disorder—not otherwise specified (PDD–NOS). Children were diagnosed between the ages of one and 14 years, with a mean age of diagnosis of 5 years old (SD = 3.21). Over 60 % were diagnosed before the age of five, with 80 % being diagnosed by the age of eight. The modal age of diagnosis was from 2 to 4 years. Of the ASD diagnoses, 43 % were made by a psychologist, 25 % by a neurologist, 17 % by a psychiatrist, 13 % by a pediatrician, and 2 % by another professional.

At Time 2, the 84 children and adolescents with ASD ranged in age from 8 to 18 years (M = 13, SD = 3.27). Of the 84 children, 87 % were male and 13 % were female; 88 % were White, 5 % were Black, 4 % were Latino, and 3 % were Mixed or Other ethnicity. At Time 1, the participants were originally sampled from autism listservs, websites, and support groups across the country. At the Time 2 data collection, the participants lived in 23 different states, with the majority coming from New York (23 %), Missouri (19 %), and Mississippi (18 %).

Of the 84 parents completing the questionnaires, 96 % were mothers of the child and 4 % were fathers. Parental ages at Time 2 ranged from 32 to 58 years (M = 45, SD = 6.35); 82 % of the current sample was married, 11 % divorced, 5 % never married and living alone, and 2 % separated. When asked about the total family income at Time 2, it was reported that 38 % made $100,000 and above, 19 % made between $75,000 and $99,999, 20 % made between $50,000 and $74,999, 10 % made between $35,000 and $49,999, 5 % made between $25,000 and $34,999, 6 % made between $15,000 and $24,999, 1 % made between $10,000 and $14,999, and 1 % made less than $4,999.

Measures

Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 6–18 (CBCL; Achenbach and Rescorla 2001)

The CBCL, administered at Time 1 and Time 2, is a broadband measure of child psychopathology that consists of 113 items pertaining to behavior and emotional problems. All items are scored on a 3-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 2, with 0 being Not True (as far as you know), 1 being Somewhat or Sometimes True, and 2 being Very True or Often True. The focus of the current study was on the Externalizing Behaviors score, which is a composite of the Rule-Breaking Behavior and Aggressive Behavior scales. Examples of items on this composite score include, “argues a lot,” “disobedient at home,” “doesn’t seem to feel guilty after misbehaving,” and “threatens people” (Achenbach and Rescorla). The Externalizing Behaviors composite score has demonstrated strong test–retest reliability, internal consistency, and construct validity when correlated with other measures of externalizing behaviors (Achenbach and Rescorla). The CBCL has been used widely in other studies to measure behavioral functioning among children and adolescents with ASD (e.g., Ozonoff et al. 2005; Sikora et al. 2008). In the current sample, the Externalizing Behaviors composite score also showed good internal consistency, α = .90 (Time 1) and α = .87 (Time 2).

The Family Questionnaire (FQ; Wiedemann et al. 2002)

The FQ, administered at Time 1 and Time 2, is a brief scale assessing expressed emotion. The family member rates how each of 20 statements relates to their feelings about their child on a 4-point Likert scale (Never/Very Rarely, Rarely, Often, Very Often). Ten items pertain to criticism/hostility (e.g., “He/she irritates me;” “I have to try not to criticize him/her”), whereas the other ten items pertain to emotional overinvolvement (e.g., “I often think about what is to become of him/her;” “I have given up important things in order to be able to help him/her;” Wiedemann et al.).

The FQ is well validated with the Camberwell Family Interview (CFI; Vaughn and Leff 1976) among patients diagnosed with schizophrenia (Wiedemann et al. 2002) and appears to be a time-efficient alternative to the standard interview for tapping the construct of expressed emotion. In the current sample, both scales also showed good internal consistency with α = .88 (Time 1) and α = .87 (Time 2) for the criticism/hostility scale and α = .82 (Time 1) and α = .80 (Time 2) for the emotional overinvolvement scale. To note, although no a priori hypotheses were made regarding parental emotional overinvolvement, it was included as a control in assessing the unique properties of parental criticism/hostility in predicting child externalizing behaviors.

Children’s Social Behavior Questionnaire (CSBQ; Hartman et al. 2006; Luteijn et al. 2000)

The CSBQ, administered at Time 1, is a measure of ASD symptom severity (based on DSM-IV criteria) for children and adolescents, ages 3–18 years. Parents rate their children, on each of the 49 items from 0 to 2, with 0 being “it does not describe the child,” 1 being “infrequently describes the child,” and 2 being “clearly applies to the child” (Luteijin et al.). The CSBQ contains five scales as well as an overall severity scale.

The CSBQ Total score was used for descriptive purposes. Although no known studies have evaluated a cutoff total score as a measure of diagnostically categorizing children, descriptive statistics for various ASD groups are available (Hartman et al. 2006). Scores of 18 points or higher are within a standard deviation of the average score of at least one of the ASD groups and can serve as a proxy for a significant score. A more conservative score of 20 has previously been used as a target score for inclusion in an ASD group for research purposes (i.e., in comparison to a control group; Henderson et al. 2011). Individual scores from the current sample ranged from 14 to 82 (median = 45.5, mode = 42), with only five of 84 participants with a score below the more conservative score of 20. On average, the current sample demonstrated high levels of ASD symptom severity (M = 46.42, SD = 16.46) based on the original CSBQ Total score.

For the current study and consistent with Bader et al. (2014), a revised CSBQ Total score was created that excluded 5 items (items 30, 31, 32, 37, and 44, which focused on changes in mood, anger, disobedience, and stubbornness) due to overlap in content with the outcome variable (CBCL Externalizing Behaviors composite). This was important given that the CSBQ Total score would be used as a control variable in analyses with this outcome variable. Internal consistency within the current sample was very good with α = .91 for the revised total scale and α = .92 for the original total scale.

Parenting Stress Index: Short Form (PSI; Abidin 1995)

The PSI, administered at Time 1, is a 36-item measure designed to assess stable patterns of parental distress that are commonly linked to dysfunctional parenting. Parents rate their perceptions on a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 being “Strongly Agree,” and 5 being “Strongly Disagree,” on items such as “My child is not able to do as much as I expected” and “I feel alone and without friends.” Items load onto three scales, Parental Distress, Parent–Child Dysfunctional Interaction, and Difficult Child as well as an overall Total Stress score.

For the current study, the Parental Distress scale was used as a control variable in the analyses examining the relation between parental expressed emotion and child externalizing behavior and vice versa. The scales from the short form of the PSI, including the Parental Distress score, have shown strong test–retest reliability, internal consistency, and correlation with the full-length PSI (Abidin 1995). The PSI has been used in other studies with samples of parents of children and adolescents with ASD (e.g., Dumas et al. 1991; Hoffman et al. 2009; Tomanik et al. 2004). Internal consistency for the current sample was also good, with α = .88 for the Parental Distress scale.

Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ; Frick 1991; Shelton et al. 1996)

On the APQ, administered at Time 1, parents rate how well each of 42 items describes their parenting practices on a 5-point Likert scale (Shelton et al.). Examples of items include “You have a friendly talk with your child” and “You feel that getting your child to obey you is more trouble than it’s worth” (Shelton et al.). Although the APQ is not normed to use as a clinical measure of parenting practices, it has a strong empirical base supporting its use in research (e.g., De Los Reyes et al. 2013; Shaffer et al. 2013) and has fairly recently updated psychometric information (including with translated versions of the measure) that reconfirms its factor structure (e.g., Essau et al. 2006). Scales from the APQ have also been used previously in research with ASD samples (e.g., Brookman-Frazee et al. 2010).

In the current study, as in Bader et al. (2014), positive and negative parenting composite scores were created by summing the z-scores of the respective scales. The Parental Involvement and Positive Parenting scales loaded onto the positive parenting composite. The Poor Monitoring/Supervision, Inconsistent Discipline, and Corporal Punishment scales loaded onto the negative parenting composite. Within the current sample, both composite scores showed adequate internal consistency: α = .85, for the positive parenting composite and α = .66 for the negative parenting composite. For the current study, the positive parenting composite and negative parenting composite were used as control variables in the analyses examining the relation between parental expressed emotion and child externalizing behavior and vice versa.

Demographic and Diagnostic Information Questionnaire

This extensive questionnaire, administered at Time 1 (Bader et al. 2014) and Time 2 obtained the following information: socioeconomic, socio-cultural, diagnostic, and assessment information about the child and family. It also included confirmation of a diagnosis of ASD; specifically, parents reported on diagnostic classification, age of diagnosis, professional and affiliation making diagnosis (i.e., to rule-out parents merely self-reporting that they think the child has the diagnosis), medication history, current medication type/dosage, family history of ASD diagnoses, and history and details of diagnoses of other psychological/behavioral disorders for the child (if applicable).

Procedure

The 104 parents who participated in Time 1 (Bader et al. 2014) whose child with ASD was still under the age of 18 years old at the time of Time 2 data collection were eligible for the study. These parents had consented to be contacted via email or a phone call to participate in further studies. The researcher used internet resources to locate new contact information for parents in the event that they could no longer be reached with the original contact information. Once consent to participate in Time 2 of the data collection had been obtained, the parents were emailed their own unique link to a survey site, where they were able to complete the questionnaires online. The participants were also given an option to have a paper copy of the measures mailed to them if preferred. Only one participant opted for this format, in which case the measures, along with a self-addressed stamped envelope were mailed to the participant. The set of questionnaires took approximately an hour to complete. Participants were asked to complete all questionnaires at one time, but were able to return to the questionnaires at a later time if that was not possible.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Descriptive Statistics for Variables of Interest

Descriptive statistics for the variables of interest are displayed in Table 1. As noted earlier, the current sample demonstrated high levels of ASD symptom severity at Time 1 (M = 46.42, SD = 16.46) based on the original CSBQ, which is consistent with a clinically significant score on the CSBQ.

Zero-Order Correlations Among Variables of Interest

Zero-order correlations were performed among the variables of interest to determine how they were interrelated prior to conducting the regression analyses. Variables included Time 1 ASD symptom severity and Time 1 parenting variables (i.e., all a priori control variables), both Time 1 and Time 2 parental expressed emotion variables (i.e., criticism/hostility and emotional overinvolvement), and both Time 1 and Time 2 child externalizing behaviors. Results of the correlations among the variables of interest are presented in Table 2. Given the longitudinal hypothesis regarding parental expressed emotion as a predictor of increases in child externalizing behaviors over time, it is important to note that the main predictor variables of interest—Time 1 criticism/hostility and Time 1 emotional overinvolvement—were significantly positively correlated with Time 2 child externalizing behaviors, r = .62, p < .001 and, r = .33, p = .002, respectively. Also, because of the planned analyses to examine the alternative direction of temporal sequencing (i.e., child behaviors as a predictor of increases in parental expressed emotion over time), it is noteworthy that Time 1 child externalizing behaviors significantly positively related to Time 2 criticism/hostility, r = .48, p < .001, but not Time 2 emotional overinvolvement, r = .16, p = .15. These correlational findings provided support for further examining the relation among these variables in the planned regression analyses.

Results in Table 2 also indicate the stability of the current study’s key variables (parental expressed emotion and child externalizing behaviors). Time 1 variables were significantly positively correlated with their Time 2 counterpart for child externalizing behaviors, r = .67, p < .001, parental criticism/hostility, r = .66, p < .001, and parental emotional overinvolvement, r = .68, p < .001. Thus, all were positively correlated and the magnitude of their relation indicated a large effect size (Cohen 1992). However, because they were not perfectly correlated, there was some variability in scores at Time 2 relative to Time 1. Such a finding underscores the importance of identifying predictors of such change.

Zero-Order Correlations Among Demographic and Time 2 Outcome Variables

Zero-order correlations were also performed among demographic variables and the variables used as Time 2 outcome variables [i.e., Time 2 child externalizing behaviors and Time 2 parental expressed emotion variables (criticism/hostility and emotional overinvolvement)] to examine whether any demographic variables significantly related to the Time 2 outcome variables and thus needed to be controlled for in the analyses. Categorical variables were dichotomized (e.g., race was coded as White or Non-White) before calculating correlation coefficients. Results are presented in Table 3. The only significant correlation was between total family income and Time 2 child externalizing behaviors, r = −.23, p = .04. Thus, total family income was used as a demographic control variable in the analysis examining Time 1 parental expressed emotion predicting Time 2 child externalizing behaviors. No demographic variables were significantly related to Time 2 criticism/hostility or Time 2 emotional overinvolvement; therefore, no demographic control variables were entered in the analyses examining either of the Time 2 parental expressed emotion variables as the outcome.

Regression Analyses

To examine the temporal sequencing of the relation between parental expressed emotion and child externalizing behaviors—including whether one can predict change in the other—hierarchical regression analyses were conducted using Time 1 and Time 2 data. In addition to total family income being controlled in the analysis examining child externalizing behaviors as an outcome variable, based on an a priori decision (and consistent with Bader et al. 2014), ASD symptom severity (revised score), parental distress, positive parenting practices, and negative parenting practices were used as control variables in all of the regression analyses. These control variables were included to ensure that the findings of the regression analyses were the unique relation between the variable of interest and the outcome variable and not due to one of these control variables (possible confounds). Also, Time 1 of the outcome variable in each regression was controlled for to allow examination of the change from one time point to another, rather than just the Time 2 level, of that outcome variable.

Time 1 Parental Expressed Emotion Predicting Change in Time 2 Child Externalizing Behaviors

The first analysis tested whether Time 1 parental expressed emotion predicted change in Time 2 child externalizing behaviors (to test our overall hypothesis). Time 2 child externalizing behaviors were examined as the outcome variable. Step 1 predictors included the following Time 1 variables: total family income, ASD symptom severity (revised score), parental distress, positive parenting practices, negative parenting practices, and child externalizing behaviors. Step 2 predictors included Time 1 parental criticism/hostility and Time 1 emotional overinvolvement. These two variables were significantly positively correlated with one another, r = .59, p < .001 (Table 2); however, both components of expressed emotion were entered simultaneously so that the total amount of variance accounted for by Time 1 parental expressed emotion could be evaluated (i.e., through an examination of R 2∆ at step 2) and so that the unique contribution of each component of Time 1 parental expressed emotion could be evaluated (i.e., through an examination of the β-weights).

Results revealed that step 2 predicted significant additional variance (above and beyond the control variables) in the Time 2 CBCL externalizing composite, F∆ (2, 75) = 4.99, p = .009; R 2∆ = .06. Table 4 displays R 2∆ for each step and the standardized regression coefficients (β) for each variable. After controlling for the other demographic and parenting variables (as well as Time 1 child externalizing behaviors) parental expressed emotion accounted for 5.8 % of the variance in the change in child externalizing behaviors from Time 1 to Time 2. An examination of the beta-weights indicated that Time 1 criticism/hostility significantly predicted Time 2 child externalizing behaviors, β = .33, p = .02, even when controlling for Time 1 child externalizing behaviors and all other variables in the model. Specifically, higher levels of Time 1 criticism/hostility related to increases in child externalizing behaviors at Time 2, whereas emotional overinvolvement did not, β = .06, p = .61. [Notably, the same pattern held when examining only control variables determined a priori in the model as well as when examining Time 1 parental expressed emotion predicting Time 2 child externalizing behaviors controlling only for Time 1 child externalizing behaviors. In both of those analyses, Time 1 parental criticism/hostility was a significant unique predictor of Time 2 child externalizing behaviors.]

Time 1 Externalizing Behaviors Predicting Change in Time 2 Parental Expressed Emotion

Next, parental criticism/hostility and emotional overinvolvement at Time 2 were examined as outcomes in two separate analyses to test whether child externalizing behaviors at Time 1 predicted change in parental expressed emotion at Time 2. Step 1 predictors included the following Time 1 variables: ASD symptom severity (revised score), parental distress, positive parenting practices, negative parenting practices, and criticism/hostility or emotional overinvolvement (depending on the analysis). Time 1 child externalizing behaviors were entered as the predictor on the second step of each regression analysis. Results revealed that Time 1 child externalizing behaviors did not predict additional variance (above and beyond parenting variables) in the change in Time 2 criticism/hostility or Time 2 emotional overinvolvement, F∆ (1, 77) = .20, p = .65; R 2∆ = .001 and F∆ (1, 77) = .19, p = .67; R 2∆ = .001, respectively. Tables 5 and 6 display R 2∆ for each step and the standardized regression coefficients (β) for each variable for these two analyses. [Notably, the same pattern held when examining Time 1 child externalizing behaviors predicting each of the Time 2 parental expressed emotion domains controlling only for Time 1 of the respective domain. In both of those analyses, Time 1 child externalizing behaviors did not significantly predict either Time 2 parental expressed emotion domain.]

Discussion

The findings of the current study supported the overall a priori hypothesis. It was found that parental expressed emotion, specifically Time 1 criticism/hostility, significantly predicted a change in externalizing behaviors from Time 1 to Time 2, even after controlling for Time 1 severity of ASD symptoms, parental distress, parenting practices, and total family income. Thus, children and adolescents with ASD living in family environments characterized by higher parental expressed emotion, specifically parental criticism/hostility, displayed increasingly more severe externalizing behaviors over time than children living in lower expressed emotion families. Consistent with the Greenberg et al. (2006) findings, this relation was not found to hold in the opposite direction; externalizing behaviors at Time 1 did not significantly predict a change in parental expressed emotion (neither criticism/hostility nor emotional overinvolvement) at Time 2. In other words, high parental criticism/hostility at Time 1 predicted a significant change (increase) in child externalizing behaviors 2 years later, but high child externalizing behaviors at Time 1 did not predict a significant change in either parental criticism/hostility or parental emotional overinvolvement 2 years later. Notably, 5.8 % of the variance in the change in child externalizing behaviors over the two-year period was accounted for by parental criticism/hostility after controlling for the other variables of interest. Moreover, these findings provide further support for the unidirectional relation between parental expressed emotion and externalizing behaviors in children and adolescents with ASD found by Greenberg et al. and both extends it to a younger ASD sample and demonstrates that the findings hold even when controlling for other parenting variables that may impact child externalizing behaviors.

Theoretical Implications of the Findings

The current study broadens support for the overall utility of expressed emotion’s relation to behavior by showing that this unidirectional relation generalizes to children and adolescents with ASD. It is important to note that these findings indicate a directionality of the relation, and not a causal relationship. The findings of the current study show that higher parental expressed emotion predicts an increase in externalizing behaviors in children and adolescents with ASD 2 years later, which provides some initial support for the theory that change in behavior of children and adolescents with ASD, may, in part, be due to their parent’s emotional valence. Parents who exhibit higher levels of criticism/hostility likely exhibit more emotional valence than those with lower expressed emotion. This emotional valence, when exhibited in the context of externalizing behaviors, could reinforce the behavior, as it would provide a great deal of attention to the externalizing behavior, which could then contribute to the increase in both the frequency and intensity of the children’s externalizing behaviors.

A parent with high expressed emotion, who demonstrates high levels of emotional valence, may display stronger, more intense reactions to negative behaviors and more mild reactions to the positive behaviors. The intensity of the reactions could serve to maintain—or even increase—the negative behaviors, while, at the same time, it would not provide enough support to increase the positive behaviors, thus contributing to the increase in the frequency and intensity of negative behaviors over time, causing a negative cycle. These possible explanations of the mechanism of this relation require further studies, preferably involving actual behavioral observations, to be fully supported. The current study, however, provides the empirical support and a theoretical basis to begin examining the exact mechanism by which the relation is expressed.

Clinical Implications of the Findings

The current study not only adds to the expressed emotion and ASD literature but also has important clinical implications. Decreasing expressed emotion in family members has been seen to be an integral component of treatments for many other disorders, specifically schizophrenia (Pharoah et al. 1999; Pitschel-Walz et al. 2001), but also including depression, anxiety, bipolar, health, and behavior disorders (Butzlaff and Hooley 1998; Eisner and Johnson 2008; Hooley and Gotlib 2000; Stubbe et al. 1993; Wearden et al. 2000). The unidirectional findings of the current study provide support for adding a component aimed at decreasing parental expressed emotion when treating children and adolescents with ASD. Further studies examining the benefits of adding this treatment component to the overall treatment package for children and adolescents with ASD, especially those children demonstrating high levels of associated externalizing behaviors, are warranted.

As suggested by the findings of the current study, as well as those in Bader et al. (2014), Baker et al. (2011), Greenberg et al. (2006), and Hastings et al. (2006), a possible point of intervention in treating externalizing behaviors in children and adolescents with ASD is parental expressed emotion, specifically criticism/hostility. The current findings, that this relation is unidirectional with high parental expressed emotion predicting an increase in externalizing behaviors over time, provides further support that this parental factor needs to be explored and addressed as a possible point of intervention in addressing externalizing behaviors in children and adolescents with ASD. One possible method of decreasing expressed emotion is incorporating components of mindfulness and acceptance in the overall treatment package (e.g., Dumas 2005). For example, parent training could include such skills as facilitative listening (a form of communication that fosters an understanding and nonjudgmental acceptance of thoughts, feelings and actions both in themselves and their children), distancing (placing a psychological barrier between one’s thoughts and feelings about a particular situation and the way one feels he or she must act in that situation, which helps to decrease the emotional reactions expressed by parents), and motivated action plans (specific maps, scripts, or steps of actions to accomplish a desired outcome; Dumas).

Limitations

Several limitations of the current study should be mentioned. First, the current study relied on single informant, parent-report data, which could result in a rater response set. However, parent ratings of child behavior are widely used and clinically meaningful. Likewise, parent self-report was appropriate given the nature of the parent constructs. Future studies should attempt to replicate these finding with other methods.

Second, there may be something unique or distinct about the parents and children who agreed to participate in Time 2 of the study, relative to those who did not. To minimize attrition, multiple attempts were made via phone calls, messages, emails, and in some cases letters, to contact participants from Time 1 who were still eligible. Still, the rate of attrition was less than 20 %, which is acceptable for a longitudinal study spanning over 2 years (Fischer et al. 2001). Therefore, there did not appear to be an excessive rate of refusal at Time 2.

Third, the child’s diagnosis was not corroborated with assessment measures or standardized format and assessment protocol (e.g., Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised; Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule) beyond the CSBQ. Nevertheless, the Demographic and Diagnostic Information Questionnaire at both Time 1 and Time 2 provided extensive information, which allowed us to establish that a diagnosis had been made by an independent practitioner. Likewise, the current sample’s mean fell within the diagnostic range for ASD on the CSBQ Total (Hartman et al. 2006).

Fourth, although support groups, listservs, and websites were used to sample in both rural and urban settings throughout the country, the majority of the sample included White, middle to upper-class, married parents whom are active in autism support groups. Thus, the findings may not generalize to the overall population of children and adolescents with ASD. Interestingly, the fact that total family income still related, in some of the analyses, to externalizing behaviors in this relatively homogeneous, middle to upper middle class sample, indicates how strong of a predictor family income may be in a more heterogeneous sample. This possibility is certainly worth further exploring. It is also noteworthy that the sample consisted of 87 % males. Although ASD is a male-dominated disorder, the ratio of males to females in the current sample (6:1) was still somewhat higher than the base rates among the ASD population (approximately 4 males to every 1 female; American Psychiatric Association 2013). Because of the limited number of females in the current sample, it is unclear how well these findings apply to girls with ASD.

Finally, the conclusions that can be drawn are further limited by the quasi-experimental design of the current study. Whereas the current study examined the direction of the relation of these constructs and whether the relation was uni- or bi-directional, the only assertion that can be made is that the findings imply a causal relation in that high parental criticism/hostility predicts increasing levels of externalizing behaviors in children and adolescents with ASD over time (whereas the reverse was not found). The longitudinal design is more robust and provides a great deal more support for this possible causal relation than a cross-sectional design as was conducted by Bader et al. (2014). Furthermore, the longitudinal design addressed an issue raised by Bader et al. in that a cross-sectional relation does not determine which variable precedes the other. It also adds to the longitudinal unidirectional findings by Greenberg et al. (2006) by using a more homogenous sample and controlling for other parenting variables that relate to child and adolescent externalizing behaviors.

Directions for Future Research

Future treatment outcome studies could be conducted looking at the utility of adding a treatment component addressing parental expressed emotion to the overall treatment package for externalizing behaviors in children and adolescents with ASD. It would be important to establish whether parental expressed emotion at the beginning of a treatment affects the outcome of the treatment (i.e., treatments for children and adolescents with ASD in a high expressed emotion household may be less effective than for those in a low expressed emotion household). Such research should focus on the exact mechanism of change and benefits (if any) of focusing on reducing parental expressed emotion among parents of children and adolescents with ASD. Studies could also examine expressed emotion among the staff of inpatient and residential facilities to determine if this robust relation holds in those settings as well as with caregivers who are not family members; again, there would be important treatment implications if a significant relation were found.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current study adds to both the autism and expressed emotion literature, as it is the first known study examining the longitudinal relation between parental expressed emotion and externalizing behaviors in a homogeneous sample of children, ages 8–18, with ASD, controlling for a variety of other parenting variables in an effort to examine the unique relation of parental expressed emotion. Given a unidirectional relation between parental expressed emotion and externalizing behaviors in children and adolescents with ASD has been established, further research should determine if parental expressed emotion moderates treatment efficacy for children and adolescents with ASD who are referred due to externalizing behaviors. If so, lowering parental expressed emotion could become an important point of intervention as a component of a larger treatment package aimed at decreasing externalizing behaviors in children and adolescents with ASD. It may also be beneficial for further studies to explore the relation between parental expressed emotion and other child variables such as internalizing symptoms and social skills. Such research can foster a deeper understanding of assessment, diagnostic, and treatment issues for children and adolescents with ASD in an effort to minimize the impairments associated with it.

References

Abidin, R. (1995). Parenting stress index, third edition; professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition-text revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Bader, S. H. Barry, T. D., & Hann, J. H. (2014). The relation between parental expressed emotion and externalizing behaviors in children and adolescents with an autism spectrum disorder. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. doi:10.1177/1088357614523065.

Baker, J. K., Smith, L. E., Greenberg, J. S., Seltzer, M., & Taylor, J. (2011). Change in maternal criticism and behavior problems in adolescents and adults with autism across a 7-year period. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120, 465–475.

Brookman-Frazee, L. I., Taylor, R., & Garland, A. F. (2010). Characterizing community-based mental health services for children with autism spectrum disorders and disruptive behavior problems. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 1188–1201.

Butzlaff, R. L., & Hooley, J. M. (1998). Expressed emotion and psychiatric relapse: A meta-analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55, 547–552.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155–159.

De Los Reyes, A., Ehrlich, K. B., Swan, A. J., Luo, T. J., Van Wie, M., & Pabon, S. C. (2013). An experimental test of whether informants can report about child and family behavior based on settings of behavioral expression. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22, 177–191.

Dumas, J. E. (2005). Mindfulness-based parent training: Strategies to lessen the grip of automaticity in families with disruptive children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 779–791.

Dumas, J. E., Wolf, L. C., Fisman, S. N., & Culligan, A. (1991). Parenting stress, child behavior problems, and dysphoria in parents of children with autism, down syndrome, behavior disorders, and normal development. Exceptionality, 2, 97–110.

Eisner, L. R., & Johnson, S. L. (2008). An acceptance-based psychoeducation intervention to reduce expressed emotion in relatives of bipolar patients. Behavior Therapy, 39, 375–385.

Essau, C. A., Sasagawa, S., & Frick, P. J. (2006). Psychometric properties of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15, 597–614.

Fischer, E. H., Dornelas, E. A., & Goethe, J. W. (2001). Characteristics of people lost to attrition in psychiatric follow-up studies. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 189, 49–55.

Frick, P. J. (1991). The Alabama Parenting Questionnaire. Unpublished instrument. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama.

Greenberg, J. S., Seltzer, M. M., Hong, J., & Orsmond, G. I. (2006). Bidirectional effects of expressed emotion and behavior problems and symptoms in adolescents and adults with autism. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 111, 229–249.

Hartman, C. A., Luteijn, E., Serra, M., & Minderaa, R. (2006). Refinement of the Children’s Social Behavior Questionnaire (CSBQ): An instrument that describes the diverse problems seen in milder forms of PDD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 6, 325–342.

Hastings, R. P., Daley, D., Burns, C., & Beck, A. (2006). Maternal distress and expressed emotion: Cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships with behavior problems of children with intellectual disabilities. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 111, 48–61.

Henderson, J. A., Barry, T. D., Bader, S. H., & Jordan, S. S. (2011). The relation among sleep, routines, and externalizing behavior in children with an autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 758–767.

Hoffman, C. D., Sweeney, D. P., Hodge, D., Lopez-Wagner, M. C., & Looney, L. (2009). Parenting stress and closeness: Mothers of typically developing children and mothers of children with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24, 178–187.

Hooley, J. M., & Gotlib, I. H. (2000). A diathesis-stress conceptualization of expressed emotion and clinical outcome. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 9, 135–151.

Luteijn, E. F., Luteijn, F., Jackson, A. E., Volkmar, F. R., & Minderaa, R. B. (2000). The Children’s Social Behavior Questionnaire for milder variants of PDD problems: Evaluation of the psychometric characteristics. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 317–330.

Mahan, S., & Matson, J. L. (2011). Children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders compared to typically developing controls on the Behavioral Assessment System for Children, Second Edition (BASC-2). Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 119–125.

Matson, J. L., & Nebel-Schwalm, M. (2007). Assessing challenging behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorder: A review. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 28, 567–579.

Ozonoff, S., Goodlin-Jones, B. L., & Solomon, M. (2005). Evidence-based assessment of autism spectrum disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 523–540.

Pharoah, F. M., Mari, J. J., & Streiner, D. L. (1999). Family intervention for people with schizophrenia (Cochrane review). The Cochrane library, 4.Oxford, UK: Update Software.

Pitschel-Walz, G., Leucht, S., Bauml, J., Kissling, W., & Engel, R. R. (2001). The effect of family interventions on relapse and rehospitalisation in schizophrenia—a meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 27, 73–92.

Shaffer, A., Lindheim, O., Kolko, D. J., & Trentacosta, C. J. (2013). Bidirectional relations between parenting practices and child externalizing behavior: A cross-lagged panel analysis in the context of a psychosocial treatment and 3-year follow-up. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 199–210.

Shelton, K. K., Frick, P. J., & Wootton, J. (1996). Assessment of parenting practices in families of elementary school-age children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25, 317–329.

Sikora, D. M., Hall, T. A., Hartley, S. L., Gerrard-Morris, A. E., & Cagle, S. (2008). Does parent report of behavior differ across ADOS-G classifications: Analysis of scores from the CBCL and GARS. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 440–448.

Stubbe, D. E., Zahner, G. E., Goldstein, M. J., & Leckman, J. F. (1993). Diagnostic specificity of a brief measure of expressed emotion: A community sample of children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 34, 139–154.

Tomanik, S., Harris, G. E., & Hawkins, J. (2004). The relationship between behaviours exhibited by children with autism and maternal stress. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 29, 16–26.

Totsika, V., Hastings, R. P., Emerson, E., Lancaster, G. A., & Berridge, D. M. (2011). A population-based investigation of behavioural and emotional problems and maternal health. Associations with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 91–99.

Vaughn, C. E., & Leff, J. P. (1976). The influence of family and social factors on the course of psychiatric illness: a comparison of schizophrenic and depressed neurotic patients. British Journal of Psychiatry, 129, 125–137.

Wearden, A. J., Tarrier, N., Barrowclough, C., Zastowny, T. R., & Rahill, A. A. (2000). A review of expressed emotion research in health care. Clinical Psychology Review, 20, 633–666.

Wiedemann, G., Rayki, O., Feinstein, E., & Hahlweg, K. (2002). The family questionnaire: Development and validation of a new self-report scale for assessing expressed emotion. Psychiatric Research, 109, 265–279.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bader, S.H., Barry, T.D. A Longitudinal Examination of the Relation Between Parental Expressed Emotion and Externalizing Behaviors in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 44, 2820–2831 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2142-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2142-6