Abstract

Researchers and practitioners conduct multi-informant assessments of child and family behavior under the assumption that informants have unique perspectives on these behaviors. These unique perspectives stem, in part, from differences among informants in the settings in which they observe behaviors (e.g., home, school, peer interactions). These differences are assumed to contribute to the discrepancies commonly observed in the outcomes of multi-informant assessments. Although assessments often prompt informants to think about setting-specific behaviors when providing reports about child and family behavior, the notion that differences in setting-based behavioral observations contribute to discrepant reports has yet to be experimentally tested. We trained informants to use setting information as the basis for providing behavioral reports, with a focus on parental knowledge of children’s whereabouts and activities. Using a within-subjects controlled design, we randomly assigned 16 mothers and adolescents to the order in which they received a program that trains informants to use setting information when providing parental knowledge reports (Setting-Sensitive Assessment), and a control program involving no training on how to provide reports. Relative to the control program, the Setting-Sensitive Assessment training increased the differences between mother and adolescent reports of parental knowledge, suggesting that mothers and adolescents observe parental knowledge behaviors in different settings. This study provides the first experimental evidence to support the assumption that discrepancies arise because informants incorporate unique setting information into their reports.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A key component of best practices in psychological assessments of children and adolescents (i.e., children) and their families involves the use of multiple informants’ reports (e.g., parents, teachers, laboratory observers, children; Hunsley and Mash 2007). Nevertheless, inconsistencies often arise across these multiple reports (De Los Reyes 2011). Researchers and practitioners commonly observe these inconsistencies (i.e., informant discrepancies) across various assessment occasions, including identifying risk factors for psychopathology, screening and diagnosis, and treatment planning and evaluation (De Los Reyes and Kazdin 2005). Informant discrepancies often pose great challenges for making sense of research findings and assessment outcomes. For instance, it is common to observe inconsistencies in informants’ reports about the outcomes of controlled trials testing psychological interventions (e.g., De Los Reyes and Kazdin 2006; Koenig et al. 2009). Importantly, much of the evidence supporting the efficacy of treatments for children rests on multiple informants’ outcome reports (for a review, see Weisz et al. 2005). Thus, informant discrepancies create interpretive problems when determining the efficacy of children’s treatments.

Researchers often espouse the advantages of taking multi-informant approaches to assessment (e.g., Hunsley and Mash 2007; Pelham et al. 2005; Silverman and Ollendick 2005). The advantages largely center on two widely held assumptions about child and family psychological assessments. The first is that informants often vary in the settings within which they observe behavior (e.g., home, school, with peers; De Los Reyes 2011). The second is that the expression of behaviors measured in child and family assessments can vary substantially as a function of setting (see Achenbach et al. 1987; Mischel and Shoda 1995). These variations in what behaviors informants witness could translate into discrepant behavioral reports and, presumably, discrepancies that meaningfully relate to setting-based variations in the expressions of behaviors (Kraemer et al. 2003).

Despite widespread agreement on the benefits of collecting multi-informant reports, researchers and practitioners vary dramatically in how they handle informant discrepancies. Most often, informant discrepancies have been treated as measurement error or informant unreliability (De Los Reyes 2011; De Los Reyes et al. 2011a, b). In other cases, researchers have taken approaches to actively incorporate setting-specific information into informants’ reports. One approach is to explicitly ask informants to consider the settings where they observe a particular behavior; this strategy provides additional information about the settings where the behaviors are most likely to occur. For example, the Adjustment Scales for Children and Adolescents (ASCA; McDermott 1993) and the Adjustment Scales for Preschool Intervention (ASPI; Lutz et al. 2002) ask informants to rate children’s behaviors across over 20 different settings (e.g., with peers, in the classroom). Similarly, in light of the fact that rejected children differ in the settings in which their social skills are lacking, the Taxonomy of Problematic Social Situations for Children (TOPS) was designed to identify which situations should be targeted for intervention (Dodge et al. 1985).

More recently, researchers have empirically tested whether the discrepancies among informants’ reports systematically differ as a function of setting-based variations in children’s behavior. For instance, when a parent reports disruptive behavior symptoms in their child that the child’s teacher does not also report, that child tends to behave disruptively under controlled laboratory conditions during parent–child interactions but not interactions with non-parental adults (i.e., a clinical examiner; De Los Reyes et al. 2009). This finding suggests that the discrepancy between parent and teacher reports might be explained by the child’s different behaviors across settings. In another study, discrepancies between parent and teacher reports of children’s aggressive behavior related to informants’ perceptions of the environmental cues that elicited the behaviors (see Hartley et al. 2011). Stated another way, increased similarity in the environmental circumstances where informants observed aggressive behavior related to increased informant agreement on aggressive behavior reports.

In sum, recent evidence indicates that, overall, discrepancies among informants’ reports reflect setting-based differences among informants’ opportunities for observing the behaviors. Yet, do informants consistently use setting information when making their reports? This is an important question because assuming, for instance, that parent reports represent “home behaviors” and teacher reports represent “school behaviors” requires experimental evidence that discrepant reports across informants occur as a result of informants systematically and consistently incorporating unique setting information into their reports.

There is limited evidence available about whether informants consistently use setting information when making behavioral reports, yet some evidence suggests that informants do not consistently use setting information when making reports. For instance, in an experimental study a sample of experienced clinicians read vignettes describing the home, school, and peer settings of children expressing symptoms of conduct disorder (De Los Reyes and Marsh 2011). Researchers randomly varied the presentation of symptoms in the presence of consistent versus inconsistent setting characteristics (e.g., consistent settings: parents experiencing psychopathology, children with deviant peer associations; inconsistent settings: well-liked by friends’ parents, studies hard to get into college). Overall, clinicians rated children whose settings included known risk factors for conduct disorder as more likely to evidence symptoms of a conduct disorder diagnosis than children described within settings that posed no contextual risk factors. However, in this same study, clinicians varied widely on when they applied setting information to their clinical judgments. Further, clinicians largely disagreed with each other in terms of the actual symptoms to which they applied setting information (e.g., clinicians disagreed on whether they applied setting information to judging expressions of truancy and fire-setting). Thus, prior work indicates that trained judges use setting information to provide behavioral reports, but do so inconsistently. Along these lines, one question is whether informants, such as parents and children, can be trained to incorporate setting information systematically in their reports. Evidence of successful training in the use of setting information would provide experimental support for the notion that it is possible for informants to provide reports that align with the assumptions researchers and clinicians make as to the utility of multi-informant assessment approaches. In turn, this support would further justify attempts to, for instance, use informant discrepancies to understand the settings in which interventions exert their effects (De Los Reyes and Kazdin 2009).

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to extend the literature on informant discrepancies in child and family behavioral assessments. In an ethnically diverse community sample of mothers and adolescents aged 13–17 years, we trained parents and adolescents to use setting information consistently when making behavioral reports (De Los Reyes and Weersing 2009). Briefly, we developed a protocol (i.e., Setting-Sensitive Assessment) that is administered by a trained interviewer who guides informants to identify settings that they perceive as personally relevant to where they observe behaviors being assessed (e.g., parental knowledge about what the adolescent does after school). Following identification of these settings, the interviewer trains informants how to provide item-by-item reports of parental knowledge behaviors based on the settings they feel are Great Examples of where the behavior being described in each specific item happens. Lastly, the interviewer administers instructions on how to precisely use setting information so that informants can make setting-based reports.

To illustrate use of the Setting-Sensitive Assessment, we focused on multi-informant assessments of what parents know about their adolescents’ whereabouts and activities (i.e., Parental Knowledge) in a sample of mothers and adolescents (Stattin and Kerr 2000). We chose to examine multi-informant reports of parental knowledge given that such reports commonly disagree (De Los Reyes et al. 2008). Therefore, informant discrepancies in parental knowledge reports are likely to be large enough to detect changes in the differences between reports when assessed across different conditions (e.g., reports completed after Setting-Sensitive Assessment training vs. reports completed without training).

We examined families with adolescents, rather than children, given that development of the Setting-Sensitive Assessment was informed by prior work on assessments of adolescent disclosure and perceived parental reactions to adolescent rule-breaking behaviors (see Darling et al. 2006; Luthar and Goldstein 2008). Further, testing a method to train mothers and adolescents to provide parental knowledge reports would inform both applied and basic research. For instance, interventions have been developed to change parental knowledge in order to prevent or reduce adolescent risk behaviors, and controlled trials of family-based interventions often focus on parental knowledge as a key outcome for testing efficacy (e.g., Pantin et al. 2009; Stanton et al. 2000, 2004; Wu et al. 2003). These interventions focus on parental knowledge because it robustly predicts the development of adolescent delinquency, risk-taking behaviors, and drug use (see Dishion and McMahon 1998; Smetana 2008). Thus, by understanding discrepant parental knowledge reports we might, in turn, increase our understanding of the outcomes of interventions targeting parental knowledge.

To address our study aims, we conducted a within-subjects controlled experiment in which we randomly assigned mothers and adolescents to the order in which they received the Setting-Sensitive Assessment and an interviewer-administered Control Assessment. The purpose of the Control Assessment was to equate the assessment conditions on exposure to settings prior to informants making behavioral reports. Thus, mothers and adolescents were exposed to and subsequently provided their impressions of the same settings to which they were exposed in the Setting-Sensitive Assessment, without receiving any training on how to use this setting information to provide parental knowledge reports. Mothers and adolescents completed behavioral reports immediately after each assessment protocol. We exposed all participants to both of these protocols as opposed to one of two protocols (i.e., a between-subjects design) because prior work indicates that informant discrepancies in parental knowledge reports are related to informants’ levels of depressed mood (De Los Reyes et al. 2008). Thus, our concern with using a between-subjects design is the likelihood that random assignment would nonetheless result in two groups of participants varying on a characteristic that accounts for variance in informant discrepancies. This would reduce power to detect between-group effects, making a within-subjects approach, in which informant characteristics are held constant across groups, the most appropriate of these two designs.

Hypotheses

Prior theoretical work suggests that parent and adolescent reports disagree, in part, because they observe behaviors in different settings and the behaviors themselves vary in their expressions across settings (Kraemer et al. 2003). In line with these ideas, the Setting-Sensitive Assessment should enhance the precision with which mothers and adolescents make reports. Importantly, mothers and adolescents can vary in the circumstances in which they observe parental knowledge behaviors. For example, mothers may notice their attempts to learn about adolescents’ activities during family conversations at dinner, whereas adolescents may not recognize these dinner conversations as instances of parents acquiring knowledge of their whereabouts and activities. Therefore, increased precision in use of setting information to provide reports should translate into mothers and adolescents providing diverging reports. Alternatively, if mothers and adolescents do not vary in use of setting information, then precise use of this information should in fact increase reporting agreement. Importantly, we held access to setting information constant across mother and adolescent reports, allowing each dyad equal opportunity to sample from settings they collectively deemed relevant to parental knowledge.

With regard to parental knowledge, we surmise that mothers and adolescents perceive parental knowledge behaviors in different settings, in line with prior work in child and family assessment generally (Achenbach et al. 1987; De Los Reyes and Kazdin 2005). Given this, if the Setting-Sensitive Assessment trains mothers and adolescents to base their reports on where they observe parental knowledge behaviors, then this training should increase the differences between mother and adolescent reports, relative to the Control Assessment. Further, these greater differences in mother-adolescent reports during the Setting-Sensitive Assessment should meaningfully reflect divergence between mother and adolescent views of parental knowledge as assessed on independent measures (i.e., increase validity of informant discrepancies in perceived parental knowledge). Thus, relative to the Control Assessment, we expected that differences between mother and adolescent reports about parental knowledge completed after the Setting-Sensitive Assessment would be consistent with differences observed between mother-adolescent parental knowledge reports completed pre-training.

Method

Participants

Participants included 16 mother-adolescent dyads. In order to participate in the current study, families had to: (a) speak English, (b) understand the consenting and interview process, (c) have an adolescent currently living in the home who the parent did not report as having a history of learning or developmental disabilities, and (d) have completed information on all constructs (in an original sample of 17 dyads, 1 dyad did not complete data on constructs used to test main hypotheses, leading to the final sample of 16). The sample included families with an adolescent aged 13–17 years (6 boys and 10 girls; M = 15.2 years; SD = 1.2) who lived in a large metropolitan area in the Mid-Atlantic United States. The parent identified family ethnicity/race as African American or Black (50%), White, Caucasian American, or European (37.5%), or Asian or Asian American (25.1%). The composition of family ethnicity/race totals above 100% because there was overlap among the ethnic/racial categories, resulting from participants having the option of selecting more than one ethnic/racial category.

Mothers were a mean age of 45.5 years (SD = 6.3, range of 33–61 years) (one participant did not provide proper age data). All mothers except one were the biological parents of the adolescent (the remaining mother was the adolescent’s adoptive parent). One quarter (25%) of the families had a weekly household income of $500 or less; 68.8% earned $901 or more per week. Regarding maternal education history, all mothers had completed high school and 87.6% had at least some degree-earning education beyond high school (e.g., associate’s, bachelor’s, or master’s degree). Maternal marital status varied, with 56.3% married or cohabitating, 25% divorced, 12.5% widowed, and 6.3% never married. Importantly, families exhibited significant variation in demographic characteristics that sometimes correlate with informant discrepancies (De Los Reyes and Kazdin 2005). Yet, prior work suggests that demographic characteristics and maternal relational status (i.e., biological vs. adoptive parent) do not relate to informant discrepancies in reports of parental knowledge behaviors (De Los Reyes et al. 2008, 2011c).

Measures

Parental Knowledge

We assessed perceptions of mothers’ knowledge of the adolescent’s whereabouts and activities (e.g., “Does your mother know what you do during your free time?”) using a widely used 9-item parental knowledge scale (Stattin and Kerr 2000). Mothers and adolescents answered parallel items, with minor word changes as needed to frame the questions appropriately for the respondent. Mothers and adolescents responded to all items with a response scale ranging from 1 (no, never) to 5 (yes, always). These scales have been studied extensively in relation to understanding discrepancies between mother and adolescent reports of adolescent and family behaviors (De Los Reyes et al. 2008, 2010).

In addition to Parental Knowledge, we collected information on mother and adolescent reports of Child Disclosure (5 items assessing how often adolescents spontaneously disclosed information to their mothers as well as efforts to conceal information) and Parental Solicitation (5 items assessing mothers’ efforts to gather information about the adolescent’s whereabouts and activities). Mothers and adolescents completed these two scales for the Control Assessment (four scales total across both informants) and the Setting-Sensitive Assessment (four scales total across both informants), resulting in a total of 8 scale reports. However, we observed low internal consistency estimates for 6 of the 8 scales (i.e., α below .70 on 6 of 8 scales). Importantly, the only two internal consistency estimates that we observed above .70 were estimates from reports completed after the Setting-Sensitive Assessment (i.e., α for mother report of Child Disclosure = .72; α for adolescent report of Parental Solicitation = .88). Further, for no two parallel report scales (i.e., same domain completed by mother and adolescent) did we observe acceptable levels of internal consistency. Importantly, internally consistent informants’ reports are necessary for reliably assessing the differences between such reports (see De Los Reyes et al. 2011c). We surmise that these low internal consistency estimates were likely due to the few opportunities (i.e., low number of mother-adolescent dyads) to demonstrate variability in scores on the scales, relative to the nine items comprising the parental knowledge scales (Tabachnick and Fidell 2001). In any event, for these reasons we do not report findings based on these scales.

Poor Parental Monitoring/Supervision

Mothers and adolescents provided independent reports of the extent to which mothers were poor monitors or supervisors of their adolescents using the 10-item Poor Monitoring/Supervision scale (e.g., “You go out without a set time to be home”) of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ; Shelton et al. 1996). The Poor Monitoring/Supervision scale was administered as part of the larger 42-item APQ, which assesses additional domains including involvement in the adolescent’s life, positive parenting, corporeal punishment, and inconsistent discipline. Mothers and adolescents reported on items using a five-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). In the present study, we excluded one item from the measure (“You hit your child with a belt, switch, or other object when he/she has done something wrong” for parent report; “Your parents hit you with a belt, switch, or other object when you have done something wrong” for adolescent report). In the current sample, the internal consistency alphas on the Poor Monitoring/Supervision scale were .86 for mothers and .89 for adolescents. Extensive evidence attests to the reliability and validity of the APQ (e.g., Essau et al. 2006; Frick et al. 1999).

Adolescent and Family Demographics

Demographic data were obtained through mother reports of adolescent age and gender, family/ethnicity/race, maternal age, maternal relationship to the adolescent, marital status, education, and family income.

Parental Knowledge Training Protocols

All mother-adolescent dyads were administered two parental knowledge training protocols. Specifically, using a within-subjects design, all dyads were randomly assigned (via random number generators created by the first author) to the order in which they received two training protocols focused on understanding settings that mothers and adolescents perceived to be relevant to where they observe parental knowledge behaviors (manuals are available from the first author). Each of these protocols was administered to all participants immediately preceding their completion of Stattin and Kerr’s (2000) parental knowledge scale. Descriptions of both of the assessment protocols, along with graphical depictions of the difference between the protocols and components held constant across protocols, are presented in Table 1 and Fig. 1a, b.

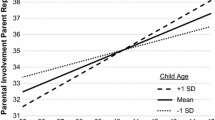

a is a graphical representation of key differences between the Setting-Sensitive Assessment (left) and Control Assessment (right). b includes (from left to right) examples of items on the parental knowledge measure, settings used to respond to parental knowledge items, and the response options upon which informants applied setting information to provide parental knowledge reports. All examples were taken from the adolescent version of the protocol and survey materials. In the original materials to which we exposed participants, the term “situation” was used in place of “setting”

Setting-Sensitive Assessment

All mother-adolescent dyads were administered a 30-min training protocol developed to increase the interpretability of parent-youth reporting discrepancies about parental knowledge (De Los Reyes and Weersing 2009). Each mother-adolescent dyad was administered the protocol in the same room and by a single interviewer. The Setting-Sensitive Assessment began with a structured discussion in which the interviewer discussed with mother-adolescent dyads the notion that different people often perceive the same object or behavior differently. Specifically, by asking dyads to estimate how many marbles are in a bowl directly in front of them, the interviewer demonstrated concretely to dyads that it is normal for two people to observe the same thing differently (i.e., by highlighting the differences between their independent responses to the marbles). The protocol began in this way, in line with prior work suggesting that discrepancies between informants’ perceptions of the same behavior pose risk for increased poor adolescent and family outcomes (De Los Reyes 2011). That is, our concern was that openly discussing perceptions of the same behaviors may promote aversive behaviors (e.g., conflict) between informants during the assessment, thus hindering progress during training. Therefore, by discussing discrepant perceptions at the beginning of the protocol, our intent was to normalize the process for mothers and adolescents, and reduce the likelihood of negative reactions in the event of widely discrepant views.

Following the introduction to the Setting-Sensitive Assessment, the interviewer guided dyads toward identifying settings in which they typically observe parental knowledge behaviors, and settings in which they do not typically observe such behaviors (for examples of settings see Fig. 1b). The interviewer guided dyads to select from a list of among 49 settings relevant to the expression of parental knowledge behaviors. Construction of the list of 49 settings was informed by prior work on assessments of adolescent disclosure and perceived parental reactions to adolescent rule-breaking behaviors (e.g., going to a friend’s house, going to parties, and who you/your child can date; see Darling et al. 2006; Luthar and Goldstein 2008). The complete list of settings is available from the first author.

For the current study, mothers and adolescents were instructed to select from the 49-setting list those settings considered Great Examples and those considered Lousy Examples of where behaviors described in parental knowledge items happen. Informants selected both Great Examples and Lousy Examples, in line with cognitive research indicating that one’s retrieval of memories of source information of, for instance, settings relevant to behaviors described in items assessing parental knowledge, is most reliable when based on processes that result in retrieval of memories both consistent and inconsistent with source information of related settings (e.g., settings relevant to behaviors indicative of parental monitoring generally; De Los Reyes and Kazdin 2005; Johnson et al. 1993).

To facilitate their setting selections, mothers and adolescents were provided lists of the individual items on three of the parental monitoring scales developed by Stattin and Kerr (2000) and based on previous work (De Los Reyes et al. 2008, 2010): nine items about what a parent knows about his/her child’s whereabouts (Parental Knowledge), five items about how he/she gains access to information about his/her child’s whereabouts (Parental Solicitation), and five items about what information a child willingly discloses about his/her whereabouts (Child Disclosure). We chose methods for setting selection based on prior research indicating that the domains represented by the scales used in this study (i.e., Parental Knowledge, Child Disclosure, and Parental Solicitation) form core components of the larger parental monitoring construct (Smetana 2008). Thus, participants provided setting information based on their perceptions of setting relevance for the three parental monitoring scales. For application across all items in a given domain (e.g., Parental Knowledge), the interviewer instructed mothers and adolescents to each select four Great Example settings and four Lousy Example settings. Thus, mothers and adolescents viewed items comprising the parental knowledge domain and selected settings for use across reports of these items.

Mothers and adolescents were free to choose any settings they wished were relevant to the items (i.e., interviewers did not require mothers and adolescents to agree that a given setting selected was a Great Example or Lousy Example setting). The one exception is that the interviewer instructed mothers and adolescents to select unique settings (i.e., no repeat settings; 16 total settings) for use in responses to items. Interviewers were trained to provide these instructions because the instructions ensured that all mothers and adolescents in the sample always had the same number of settings (16) available on which to base their parental knowledge reports. In this way, variation in scores between dyads would not be confounded by between-dyad differences in how many unique settings were used for making parental knowledge reports. Nevertheless, interviewers told mothers and adolescents that they were free to choose from among all 16 pieces of setting information when making their parental knowledge reports, regardless of who provided the information (i.e., mother or adolescent). In the current study, mothers and adolescents took turns selecting settings (i.e., mother selected a setting, followed by adolescent or vice versa). We counterbalanced each family to the order in which mothers and adolescents chose settings during the protocol.

Lastly, the interviewer trained mothers and adolescents to use setting information systematically when providing reports. As depicted in Table 1, the interviewer provided mothers and adolescents with concrete instructions for providing reports on each item of the scale (for an example of response options, see also Fig. 1b). These instructions were based on the number of settings that mother and adolescent endorsed as Great Examples of where the behaviors described in parental knowledge questions happen. The interviewer trained mothers and adolescents by going through each of the steps on how to apply setting information when providing their responses, using an example statement that was not on the parental knowledge measure that they completed (i.e., we eat meals or snacks at home). At the end of the protocol, the interviewer questioned mothers and adolescents about how to use setting information to answer scale items. Through these questions, we sought to ensure that participants attended to the instructions and understood the protocol.

After being administered the Setting-Sensitive Assessment, mothers and adolescents separately completed items with modified response options, an example of which is presented in Table 1. Also embedded into these items were the Great Example and Lousy Example settings that the mother and adolescent selected during the Setting-Sensitive Assessment. Mothers and adolescents responded to each item based on the settings they identified as Great Example settings for that particular item. Thus, consistent with administration of the Setting-Sensitive Assessment, mothers and adolescents responded to items using scale labels within which we assigned concrete definitions for providing responses, based on their Great Example endorsements for the item.

Control Assessment

In the Control Assessment, all mother-adolescent dyads were administered a structured interview in which a trained interviewer discussed the idea that parental knowledge behaviors often occur in specific settings. With this protocol, mothers and adolescents used the same materials that were given to mothers and adolescents during the Setting-Sensitive Assessment: (a) list of 49 settings and (b) list of items in the parental knowledge measures. Mothers and adolescents were asked which settings were relevant or irrelevant to their experiences with parental knowledge. Further, we developed the Control Assessment to compare against the Setting-Sensitive Assessment. Along these lines, below we report manipulation check tests that examined whether dyads only used setting information when completing reports after the Setting-Sensitive Assessment. As mentioned previously, in the Setting-Sensitive Assessment each mother-adolescent dyad produced a fixed set of 16 settings. In order to perform a manipulation check on the Control Assessment and mother-adolescent usage of setting information when completing post-protocol reports, we left free to vary the number of Great Example and Lousy Example settings that mothers and adolescents could select during the Control Assessment.

Differences Between the Assessment Protocols

To be clear, in both assessment protocols, we exposed all mothers and adolescents to the exact same parental knowledge items and settings, as graphically depicted in Fig. 1a. However, only when mothers and adolescents were administered the Setting-Sensitive Assessment were they trained on how to use this information to provide reports. These differences between the protocols are graphically depicted in Fig. 1a using a solid arrow connecting the Parental Knowledge Settings and Parental Knowledge Responses boxes for the Setting-Sensitive Assessment graphic but not the Control Assessment. In the current study, these instructions, provided only in the Setting-Sensitive Assessment, were what we surmised would be the active ingredient in changing mother and adolescent reports. That is, in the absence of training, we expected that mothers and adolescents would provide reports after the Control Assessment similar to what would be expected under routine assessment conditions. Like the Setting-Sensitive Assessment, mothers and adolescents completed reports after the Control Assessment. However, reports were completed in their standard format without setting information included (see Fig. 1a).

Procedure

All procedures were approved by the Internal Review Board of the large Mid-Atlantic university in which the study was conducted. Participants were recruited through community agencies and events and via advertisements posted online (e.g., Craigslist) in qualifying neighborhoods (i.e., neighborhoods targeted because of demographic and income variability).

Research assistants completed extensive training before being approved to assess families, including training on research protocols and general assessment techniques. Research assistant training consisted of didactic sessions with the first author and practice sessions with other research assistants. Further, to ensure the integrity of assessment administrations, research assistants practiced administering the two assessment protocols to each other multiple times (i.e., approximately 4-6 practice administrations) and videotaped these practices. At weekly supervision meetings, the first author met with trained assessors to review their practices and determine their readiness to administer the protocols. Additionally, periodically we implemented reviews of videotaped participant assessments to ensure that research assistants continued to administer the interview as trained.

After the mothers provided written consent and the adolescents provided assent, we administered their assessments via individual computer-based questionnaires. Specifically, for all assessments participants provided computer-based responses to items that were recorded using IBM SPSS Data Collection survey administration software (Version 5.6; IBM Corporation 2009). Further, all assessments were video and audio recorded using Noldus Observer XT software (Jansen et al. 2003).

The Poor Monitoring/Supervision scale of the APQ and demographic surveys were administered immediately after mothers and adolescents provided consent/assent, as part of a pre-protocol assessment battery. Participants were then administered (in a block-randomized within-subjects controlled design) the two assessment protocols. Immediately after each protocol, participants were taken to a room where they independently completed assessments as described previously. For reports completed after the Setting-Sensitive Assessment, trained research assistants observed the interview from a centralized control room, identified mothers’ and adolescents’ setting selections, and prepared their measures while the interviewer explained the measure instructions to participants. To facilitate research assistants’ reliably recording settings endorsed during the Setting-Sensitive Assessment, the interviewer instructed participants to identify settings by number (i.e., 1–49). Further, the interviewer placed numbered magnets representing settings endorsed by participants on a large magnetic dry erase board. This board was clearly visible to research assistants from video monitors located in the control room. Following the protocols and measures, participants were debriefed as to the overall goals of the study and monetarily compensated for their time. Families received a total of $80 in monetary compensation (mothers and adolescents each received $40). At the outset, families received $50 in monetary compensation (mother = $25 and adolescent = $25; n = 3 families) for an advertised 90-min study. We subsequently revised the study duration to 2–3 h, and thus increased monetary compensation to $80.

Data-Analytic Plan

Tests of our hypotheses focused specifically on mother and adolescent reports of parental knowledge. We conducted preliminary analyses to detect deviations from normality and subsequently excluded outlier cases. We then calculated internal consistency (i.e., coefficient alpha) estimates for mother and adolescent parental knowledge reports for the Setting-Sensitive Assessment and Control Assessment conditions. Further, it was important to conduct a manipulation check of our protocol conditions. Specifically, mothers and adolescents all chose 16 settings during the Setting-Sensitive Assessment protocol. However, we expected individual differences in how many Great Example situations were used by mothers and adolescents when making responses for each parental knowledge item. Therefore, we were interested in knowing whether informants used Great Example endorsements during the Setting-Sensitive Assessment to make their parental knowledge reports. Thus, we calculated correlations between informants’ Great Example endorsements and their parental knowledge reports. Here, we expected that informants’ Great Example endorsements would relate to parental knowledge reports completed after the Setting-Sensitive Assessment but not the Control Assessment.

The study’s aims and hypotheses involved examining multiple informants’ (mother, adolescent) parallel reports completed about the same construct (parental knowledge) multiple times (after receiving two different assessment protocols). Our repeated measures data were correlated, which precluded our use of general linear model (GLM) approaches to data analysis. Thus, in addition to preliminary analyses in the form of paired t-tests (these analyses do not account for correlated data structures), we tested our hypotheses using generalized estimating equations (GEE): an extension of the GLM that assumes correlated observations of dependent and/or independent variables (Hanley et al. 2003). Using GEE, we statistically modeled the four parental knowledge measures (i.e., two measures completed per informant, per assessment condition) per dyadic case as a nested (within families) repeated-measures (within dyadic subjects) dependent variable, varying as a function of three factors: (a) Condition (coded Setting-Sensitive Assessment [1] and Control Assessment [2]), (b) Informant (coded mother [1] and adolescent [2]), and (c) Condition × Informant interaction. We tested main and interaction effects. Further, we conducted planned comparisons testing differences between mother and adolescent reports within each assessment condition. Lastly, as a test corroborating reporting discrepancies observed on parental knowledge reports completed after the Setting-Sensitive Assessment, we conducted paired t-test comparisons of mother and adolescent pre-protocol reports of poor monitoring/supervision as assessed on the APQ.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Frequency distributions for all variables were examined before conducting primary analyses, to detect deviations from normality. For tests of the main hypotheses and manipulation checks for the Setting-Sensitive Assessment, we detected no deviations from normality (i.e., skewness on all variables < ± 1.0). However, we identified one dyad whose Control Assessment responses revealed extreme data in which the adolescent provided a Great Example report that was over three standard deviations from the sample mean of adolescent reports completed after the Control Assessment. After excluding this dyad from analyses of the Control Assessment data we detected no deviations from normality on Great Example report scores taken from the Control Assessment (i.e., skewness ≈ 1.0). Thus, all manipulation check analyses for the Setting-Sensitive Assessment were based on data from 16 mothers and adolescents. Manipulation check analyses for the Control Assessment were based on data from 15 mothers and adolescents. Because all tests of our main hypotheses were based on summary scores of the parental knowledge scale and preliminary analyses of this scale for both protocol conditions did not reveal deviations from normality, hypotheses tests were based on 16 dyads.

Internal Consistency of Reports Completed After the Two Assessment Protocols

We conducted tests of the internal consistency of mother and adolescent parental knowledge reports completed after the two assessment protocols. After completing the Setting-Sensitive Assessment, both mothers (α = .74) and adolescents (α = .80) provided internally consistent reports. Both mothers (α = .97) and adolescents (α = .91) also provided internally consistent parental knowledge reports after completing the Control Assessment.

For the Setting-Sensitive Assessment, it was also important to test the internal consistency of the number of Great Example settings mothers and adolescents identified for the nine parental knowledge items. This is because we developed the Setting-Sensitive Assessment with the idea that informants would use these settings to provide parental knowledge reports. Thus, mothers and adolescents should have also been able to consistently apply this setting information to individual items. This was indeed the case, as tests of the internal consistency of Great Example reports indicated for both mother (α = .79) and adolescent (α = .90) reports.

Manipulation Check on Use of Setting Information to Provide Reports

As a manipulation check, we were interested in whether mothers and adolescents based parental knowledge reports completed after the Setting-Sensitive Assessment on settings they identified as Great Examples during the Setting-Sensitive Assessment. To test this, we calculated correlations between the mean number of Great Example settings that mothers (M = 6.34; SD = 2.60) and adolescents (M = 4.64; SD = 1.93) identified for parental knowledge items completed after the Setting-Sensitive Assessment, and the total scores of parental knowledge reports that mothers and adolescents completed after the Setting-Sensitive Assessment. For both mothers and adolescents, the mean number of Great Example settings endorsed in response to parental knowledge items was significantly related to their own total parental knowledge scores, rs = .72 and .95, respectively, both ps < .01. We also calculated correlations between the number of Great Example settings endorsed by mothers (M = 10.9; SD = 6.5) and adolescents (M = 6.6; SD = 3.5) during the Control Assessment and their parental knowledge total scores completed immediately after the protocol. Importantly, we identified non-significant relations between Great Example setting reports and total parental knowledge scores for both mothers and adolescents, rs = .02 and .01, respectively, both ps > .90. Therefore, mothers and adolescents used setting information to provide parental knowledge reports after being administered the Setting-Sensitive Assessment and did not use this information after the Control Assessment.

Comparing Reports Completed After the Two Assessment Conditions

Means and standard deviations of mother and adolescent parental knowledge reports completed after the two training protocols are reported in Table 2. We conducted a preliminary test of our hypotheses by calculating paired t-tests comparing parental knowledge reports completed after the Setting-Sensitive Assessment and the same tests for reports completed after the Control Assessment. As seen in Table 2, these tests revealed that for reports completed after the Setting-Sensitive Assessment, mothers reported significantly greater levels of parental knowledge relative to adolescents. However, for reports completed after the Control Assessment, we observed non-significant differences between mother and adolescent reports. Thus, these preliminary tests supported the hypothesis that relative to no training, training mothers and adolescents to use setting information to provide parental knowledge reports results in greater discrepancies between mother and adolescent reports.

Results of GEE models testing our main hypotheses are presented in Table 3. We observed non-significant main effects of Condition and Informant and a significant Condition × Informant interaction. Consistent with our hypotheses, follow-up planned contrasts revealed significant differences between mother and adolescent parental knowledge reports completed after receiving the Setting-Sensitive Assessment and non-significant differences between mother and adolescent reports completed after receiving the Control Assessment. Thus, the findings suggest that, relative to the Control Assessment, the Setting-Sensitive Assessment increased the differences between informants’ reports.

Relating Post-Protocol Parental Knowledge Reports to Pre-Protocol Poor Monitoring/Supervision Reports

We demonstrated that training informants to use setting information to provide parental knowledge reports, relative to no training, resulted in increased differences between informants’ reports. However, it was important for us to further demonstrate that these changes yield meaningful information. One way to highlight this increase in meaningful information is to show that the direction of the differences between mother and adolescent reports after the Setting-Sensitive Assessment matched the direction of the differences between mother and adolescent reports when provided on independent poor parental monitoring/supervision measures. Thus, we calculated paired t-test comparisons of the means of mother (M = 18.50; SD = 5.24) and adolescent (M = 23.12; SD = 7.59) reports on the APQ Poor Monitoring/Supervision total scores, which as mentioned previously was completed before administration of the two assessment protocols. We chose to conduct paired t-test comparisons, given that the correlated nature of mother and adolescent reports in the sample (i.e., mother and adolescent provided reports in relation to themselves both before and after administration of the assessment protocols) precluded our use of independent samples t-test comparisons (see also De Los Reyes et al. 2011c). Consistent with the mother-adolescent differences in parental knowledge reports taken after the Setting-Sensitive Assessment, adolescents reported significantly higher values of poor monitoring/supervision, relative to mother reports, t (15) = −3.35, p < .01, d = −.71.

Discussion

Main Findings

This study extended the literature on informant discrepancies in reports of child and family behavior. In an ethnically diverse sample of mothers and adolescents, there were three main findings. First, we successfully trained mothers and adolescents to incorporate relevant setting information into their reports about parental knowledge. Second, such training resulted in increased differences between mother and adolescent parental knowledge reports. Third, of particular interest is that these differences in reports were corroborated by the differences observed between mother and adolescent reports on disparate measures of poor parental monitoring/supervision behaviors completed before training began. Therefore, these findings provide the first experimental support for the notion that informants can meaningfully and consistently use setting information to report about child and family behaviors.

One interesting observation we made warrants further commentary. Specifically, we observed non-significant mean differences between mother and adolescent reports of parental knowledge completed after receiving the Control Assessment (see Tables 2 and 3). Given the consistent finding of overall discrepancies between informants’ reports (Achenbach et al. 1987; De Los Reyes 2011), why did we observe this lack of differences between mother and adolescent reports? Interestingly, recent work may shed light on these observations. Specifically, in the absence of training, a recent study of a sample demographically similar to our own and using the same parental knowledge measures found that two small subsets of mother-youth dyads evidenced consistent, directional disagreements between reports (i.e., mother reporting greater parental knowledge behaviors relative to youth and vice versa) (De Los Reyes et al. 2010). Yet, a large segment of mother-youth dyads’ reports of parental knowledge (approximately 64% of sample) did not yield consistent, directional disagreements between reports. That is, sometimes for these dyads, mothers might report greater levels of parental knowledge than youths on one measure, youths greater than mothers on another, and no differences may be apparent on another measure. Given our sample size, it may be that most (if not all) of our participants came from this subset of mother-adolescent dyads that, without training, did not evidence robust, directional disagreements between their reports. If true, then it would lend further credence to the potency of our Setting-Sensitive Assessment approach that a program can make these informants use setting information in a way that results in meaningfully discrepant parental knowledge reports. Clearly, these issues merit further study.

A key strength of the present study is that we observed measurable effects of our Setting-Sensitive Assessment using a within-subjects randomized experimental design. That is, all informants received the two training protocols tested in the study. Presumably, this is quite a conservative test of our hypotheses because informants essentially completed parental knowledge reports twice and in the same assessment session (i.e., with no significant time lapse between parental knowledge measurement occasions). If it were the case that the two assessment protocols yielded the same information about informants’ perceptions of parental knowledge, then it logically follows that reports completed after one protocol would essentially be redundant with the other. This was not the case. Indeed, we observed quite distinct patterns of differences between mother and adolescent reports between the two training protocols. Notably, only the findings from reports taken after the Setting-Sensitive Assessment converged with findings taken from poor parental monitoring/supervision reports completed before training. Most crucially, we performed manipulation checks to test the extent to which mothers and adolescents used setting information during the Setting-Sensitive Assessment and not the Control Assessment, which included observations of significant correlations between setting reports and parental knowledge reports for reports made after the Setting-Sensitive Assessment and not the Control Assessment. Therefore, the manner in which we tested the training protocols raises confidence in the veracity of our findings.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

There were limitations to this study. First, we reported findings specific only to reports of parental knowledge, in part, because we observed low internal consistency estimates for reports on other parental monitoring domains (i.e., child disclosure, parental solicitation). This raises questions as to whether it is possible to train informants to provide reports on parental monitoring domains other than parental knowledge. At the same time, we reported previously that the only times in which we observed internal consistencies higher than an alpha of .70 were when we calculated alpha for reports completed after the Setting-Sensitive Assessment. Further, the Child Disclosure and Parental Solicitation domains were assessed on five-item scales, almost half the size of the nine-item scales used to assess parental knowledge. It is possible that the reduced scale length, coupled with low sample size, reduced the opportunity for mothers and adolescents to provide consistent reports. We encourage future research to replicate our findings using larger samples and across parental monitoring domains. Relatedly, participants provided setting information based on their perceptions of three scales (i.e., Parental Knowledge, Child Disclosure, and Parental Solicitation), but we tested participant reports about parental knowledge only. We used methods for setting selection based on prior research indicating that the domains represented by these scales form core components of the parental monitoring construct (Smetana 2008). Future research should examine whether mothers and adolescents make setting selections that are differentially related to their perceptions of the individual parental monitoring scales.

Second, the version of the Setting-Sensitive Assessment we tested included settings developed for application to adolescent and family assessments and based on previous research in the adolescent development literature (Darling et al. 2006; Luthar and Goldstein 2008). It remains unclear whether training effects through this particular assessment protocol and thus our findings would generalize to assessments with younger children. This is an important issue as the research pointing to mother–child discrepancies in perceived parental knowledge behaviors longitudinally predicting poor child delinquency outcomes was based on a sample with a large proportion of pre-adolescent children (De Los Reyes et al. 2010). We recommend future research on identifying and examining settings relevant to providing reports on parental knowledge behaviors for use with younger children.

Third, our sample size limited our ability to detect interaction effects. This has important implications for interpreting our results in light of the multitude of informant characteristics that often correlate with informant discrepancies (De Los Reyes and Kazdin 2005). We were encouraged to observe large-magnitude effects of the Setting-Sensitive Assessment relative to the Control Assessment (Table 3). At the same time, it is important that future research seek to identify the moderating effects of this and similar setting-sensitive assessment protocols, along with the mechanisms by which they exact effects on informants’ behavioral reports.

Fourth, the assessment administered for the present study was of approximately 2–3 h total duration. This raises questions as to whether the Setting-Assessment Assessment can be feasibly administered in its present form in research and clinic settings. Granted, participants were administered both the Setting-Sensitive Assessment and a control condition, and this partially accounted for the length of assessment administrations. At the same time, clinical child and family assessments typically assess multiple behavioral domains and focusing this amount of time on a single set of behaviors (e.g., parental knowledge) may not ultimately be feasible.

In line with these issues, it is important to keep in mind that a key aim of the present study was to provide experimental support for the idea that informants can consistently use setting information when providing behavioral reports. Whether the techniques we applied to test this basic question generalize to applied assessment settings awaits further study. Indeed, perhaps the techniques learned by informants during the Setting-Sensitive Assessment require practice on a single set of behaviors (e.g., parental knowledge), and the protocol, if implemented, would be of some benefit to informants’ reports across other domains assessed in a battery. That is, it is an empirical question whether, after training, the techniques generalize such that informants consistently use setting information to provide reports about domains other than the focus of the Setting-Sensitive Assessment. We welcome future research on these issues.

Research and Theoretical Implications

Training Informants to Provide Reports Increases Informant Discrepancies

Our findings have important research and theoretical implications for future work on the use of multi-informant assessments in child and family research and practice. First, our findings demonstrate an important proof of concept, in that they provide experimental support for the idea that one can train informants to make behavioral reports that are sensitive to the settings in which informants observe the behaviors being assessed. Indeed, our Setting-Sensitive Assessment equated informants on the decision rules they used to make behavioral reports, and these rules were based on meaningful variations in the settings in which behaviors are expressed. Thus, these rules produced an unambiguous interpretation of the discrepancies between informants’ reports, and in fact served to increase the differences between informants’ reports on the same scale. This increase in differences between reports is consistent with the idea that setting-based differences in informants’ behavioral observations partially account for informant discrepancies in behavioral reports (Achenbach et al. 1987; De Los Reyes 2011; Kraemer et al. 2003).

Training Informants to Provide Reports May Improve Interpretations of the Outcomes of Intervention Studies

Second, our findings suggest that if informants can be trained to use setting information when making behavioral reports, then this training can be used to further elucidate the circumstances in which interventions developed to target the behaviors being assessed exert their intended effects. That is, researchers can use setting-sensitive assessments to understand the settings in which interventions work.

Indeed, as mentioned previously, researchers rely on multiple informants’ reports to assess outcomes in controlled trials and their reports commonly disagree. We reviewed recent work indicating that informant discrepancies reveal important patterns of information on the settings in which assessed behaviors are expressed (e.g., home vs. school settings). Future work should examine whether the Setting-Sensitive Assessment can be used in intervention outcome assessments to incorporate setting information in real time. In this way, when informant discrepancies arise in outcome assessments, investigators can understand the setting-based differences for why these discrepancies arose. Subsequent to understanding discrepant reports, interventions can be modified to specifically target those settings in which informants observed changes in the behaviors targeted for intervention (see De Los Reyes and Kazdin 2008).

For instance, consider a controlled trial of a preventive intervention targeting changes in parental knowledge to prevent adolescent risk behaviors, in which outcomes supporting the effectiveness of the intervention were primarily found in mother reports and not adolescent reports. In the absence of setting information about informants’ parental knowledge reports, it would be unclear why these discrepancies in outcomes arose. However, setting information linked to the parental knowledge assessments could yield valuable insight as to why the controlled trial yielded discrepant outcomes. For example, the discrepant outcomes might have arisen because mothers perceived the intervention as effectively changing their knowledge of their adolescent’s whereabouts with neighborhood children on the weekend. In contrast, the lack of effects observed based on adolescent reports may have occurred because adolescents did not observe any change in their mother’s knowledge of what they do with friends on weekdays after school. Therefore, training informants to use setting information when making behavioral reports may serve to clarify research findings in controlled trials and developmental psychopathology research. We encourage researchers to conduct further tests of this training approach.

References

Achenbach, T. M., McConaughy, S. H., & Howell, C. T. (1987). Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 213–232.

Darling, N., Cumsille, P., Caldwell, L. L., & Dowdy, B. (2006). Predictors of adolescents’ disclosure to parents and perceived parental knowledge: Between- and within-person differences. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 667–678.

De Los Reyes, A. (2011). Introduction to the special section. More than measurement error: Discovering meaning behind informant discrepancies in clinical assessments of children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40, 1–9.

De Los Reyes, A., Goodman, K. L., Kliewer, W., & Reid-Quiñones, K. R. (2008). Whose depression relates to discrepancies? Testing relations between informant characteristics and informant discrepancies from both informants’ perspectives. Psychological Assessment, 20, 139–149.

De Los Reyes, A., Goodman, K. L., Kliewer, W., & Reid-Quiñones, K. R. (2010). The longitudinal consistency of mother-child reporting discrepancies of parental monitoring and their ability to predict child delinquent behaviors two years later. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 1417–1430.

De Los Reyes, A., Henry, D. B., Tolan, P. H., & Wakschlag, L. S. (2009). Linking informant discrepancies to observed variations in young children’s disruptive behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 637–652.

De Los Reyes, A., & Kazdin, A. E. (2005). Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 483–509.

De Los Reyes, A., & Kazdin, A. E. (2006). Conceptualizing changes in behavior in intervention research: The range of possible changes model. Psychological Review, 113, 554–583.

De Los Reyes, A., & Kazdin, A. E. (2008). When the evidence says, “yes, no, and maybe so”: Attending to and interpreting inconsistent findings among evidence-based interventions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, 47–51.

De Los Reyes, A., & Kazdin, A. E. (2009). Identifying evidence-based interventions for children and adolescents using the range of possible changes model: A meta-analytic illustration. Behavior Modification, 33, 583–617.

De Los Reyes, A., & Marsh, J. K. (2011). Patients’ contexts and their effects on clinicians’ impressions of conduct disorder symptoms. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40, 479–485.

De Los Reyes, A., & Weersing, V. R. (2009). A brief manual of an Attribution Bias Context Model assessment paradigm for parent-youth discrepancies on questionnaire ratings of parental monitoring. Unpublished manual. University of Maryland at College Park.

De Los Reyes, A., Alfano, C. A., & Beidel, D. C. (2011a). Are clinicians’ assessments of improvements in children’s functioning “global”? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40, 281–294.

De Los Reyes, A., Youngstrom, E. A., Pabón, S. C., Youngstrom, J. K., Feeny, N. C., & Findling, R. L. (2011b). Internal consistency and associated characteristics of informant discrepancies in clinic referred youths age 11 to 17 years. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40, 36–53.

De Los Reyes, A., Youngstrom, E. A., Swan, A. J., Youngstrom, J. K., Feeny, N. C., & Findling, R. L. (2011c). Informant discrepancies in clinical reports of youths and interviewers’ impressions of the reliability of informants. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 21, 417–424.

Dishion, T. J., & McMahon, R. J. (1998). Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 1, 61–75.

Dodge, K. A., McClaskey, C. L., & Feldman, E. (1985). Situational approach to the assessment of social competence in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 344–353.

Essau, C. A., Sasagawa, S., & Frick, P. J. (2006). Psychometric properties of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15, 597–616.

Frick, P. J., Christian, R. E., & Wootton, J. M. (1999). Age trends in the association between parenting practices and conduct problems. Behavior Modification, 23, 106–128.

Hanley, J. A., Negassa, A., Edwardes, D. B., & Forrester, J. E. (2003). Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: An orientation. American Journal of Epidemiology, 157, 364–375.

Hartley, A. G., Zakriski, A. L., & Wright, J. C. (2011). Probing the depths of informant discrepancies: Contextual influences on divergence and convergence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40, 54–66.

Hunsley, J., & Mash, E. J. (2007). Evidence-based assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 29–51.

IBM Corporation. (2009). IBM SPSS Data Collection (version 5.6) [computer software]. Somers, NY: IBM Corporation.

Jansen, R. G., Wiertz, L. F., Meyer, E. S., & Noldus, L. P. J. J. (2003). Reliability analysis of observational data: Problems, solutions, and software implementation. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 35, 391–399.

Johnson, M. K., Hashtroudi, S., & Lindsay, D. S. (1993). Source monitoring. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 3–28.

Koenig, K., De Los Reyes, A., Cicchetti, D., Scahill, L., & Klin, A. (2009). Group intervention to promote social skills in school-age children with pervasive developmental disorders: Reconsidering efficacy. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 1163–1172.

Kraemer, H. C., Measelle, J. R., Ablow, J. C., Essex, M. J., Boyce, W. T., & Kupfer, D. J. (2003). A new approach to integrating data from multiple informants in psychiatric assessment and research: Mixing and matching contexts and perspectives. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 1566–1577.

Luthar, S. S., & Goldstein, A. S. (2008). Substance use and related behaviors among suburban late adolescents: The importance of perceived parent containment. Development and Psychopathology, 20, 591–614.

Lutz, M. N., Fantuzzo, J. F., & McDermott, P. A. (2002). Contextually relevant assessment of the emotional and behavioral adjustment of low-income preschool children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 17, 338–355.

McDermott, P. A. (1993). National standardization of uniform multisituational measures of child and adolescent behavior pathology. Psychological Assessment, 5, 413–424.

Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (1995). A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychological Review, 102, 246–268.

Pantin, H., Prado, G., Lopez, B., Huang, S., Tapia, M. I., Schwartz, S. J., et al. (2009). A randomized controlled trial of Familias Unidas for Hispanic adolescents with behavior problems. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71, 987–995.

Pelham, W. E., Fabiano, G. A., & Massetti, G. M. (2005). Evidence-based assessment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 449–476.

Shelton, K. K., Frick, P. J., & Wootton, J. M. (1996). Assessment of parenting practices in families of elementary school-age children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25, 317–329.

Silverman, W. K., & Ollendick, T. H. (2005). Evidence-based assessment of anxiety and its disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 380–411.

Smetana, J. G. (2008). ‘‘It’s 10 o’clock: Do you know where your children are?’’ Recent advances in understanding parental monitoring and adolescents’ information management. Child Development Perspectives, 2, 19–25.

Stanton, B., Cole, M., Galbraith, J., Li, X., Pendleton, S., Cottrel, L., et al. (2004). Randomized trial of a parent intervention: Parents can make a difference in long-term adolescent risk behaviors, perceptions, and knowledge. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 158, 947–955.

Stanton, B. F., Li, X., Galbraith, J., Cornick, G., Feigelman, S., Kaljee, L., et al. (2000). Parental underestimates of adolescent risk behavior: A randomized, controlled trial of a parental monitoring intervention. Journal of Adolescent Health, 26, 18–26.

Stattin, H., & Kerr, M. (2000). Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development, 71, 1072–1085.

Tabachnick, B., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Weisz, J. R., Jensen Doss, A., & Hawley, K. M. (2005). Youth psychotherapy outcome research: A review and critique of the evidence base. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 337–363.

Wu, Y., Stanton, B. F., Galbraith, J., Kaljee, L., Cottrell, L., Li, X., et al. (2003). Sustaining and broadening intervention impact: A longitudinal randomized trial of 3 adolescent risk reduction approaches. Pediatrics, 111, e32–e38.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by an internal grant from the University of Maryland (General Research Board Summer Award Program) awarded to Andres De Los Reyes and an NRSA Predoctoral Award (F31 DA027365) awarded to Katherine B. Ehrlich. Portions of this paper’s findings were presented at the Council on Undergraduate Research’s Posters on the Hill Event (April 2011; Washington, DC) and the biennial meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence (March 2012; Vancouver, BC). We are grateful to Ho-Man Yeung for his assistance with data collection and administration of training protocols for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

De Los Reyes, A., Ehrlich, K.B., Swan, A.J. et al. An Experimental Test of Whether Informants can Report About Child and Family Behavior Based on Settings of Behavioral Expression. J Child Fam Stud 22, 177–191 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9567-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9567-3