Abstract

Children with autism face enormous struggles when attempting to interact with their typically developing peers. More children are educated in integrated settings; however, play skills usually need to be explicitly taught, and play environments must be carefully prepared to support effective social interactions. This study incorporated the motivational techniques of Pivotal Response Training through peer-mediated practice to improve social interactions for children with autism during recess activities. A multiple baseline design across subjects was used to assess social skills gains in two elementary school children. The results demonstrated an increase in important social skills, namely social initiations and turn taking, during recess.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Walking out onto a playground during recess at an elementary school one would expect to see a range of naturalistic activities that encourage communication and social skill development such as, children pretending to be their favorite super hero as they run and chase each other on the playground, taking turns shooting a basketball, kicking a ball around the field, sharing playground materials, or requesting to take a turn in order to engage in an activity with peers. On reflection of the various components of play on the playground, social skills are at the core of play skill acquisition that naturally occurs in typically developing children. For children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) the acquisition of social skills does not naturally occur. There is some promising literature demonstrating successfully acquisition of social skills for children with ASD. Several studies focused on teaching skills in a setting where children spend significant amounts of time, that of the school playground (e.g., Baker et al. 1998).

Social play may not be pleasurable nor intrinsically motivating for a child with autism (Brown and Murray 2001). Due to a desire for routine and predictability, a new play sequence may represent change thereby causing anxiety to the child with autism. It may be difficult for the child to engage in play due to interfering behaviors such as repetitive behaviors, impulsiveness, or compulsive tendencies that may be more motivating than play (Peeters 1997; Veale 1998). Libby et al. (1998) found that children with autism produced significantly more sensorimotor actions, supporting the view that this behavior may dominate play. Children with autism have been noted to use fewer toys, spend less time playing with toys and less time playing appropriately with toys compared to non-disabled peers (Stone et al. 1990) and demonstrated fewer functional play acts compared with their peers. Imitation skills were also significantly lower and children with autism engaged in functional and symbolic play less in comparison to their peers. Outcomes for preschoolers with ASD who socially avoided peers tended to continue to avoid peers and use less language as they aged compared to those who showed social interest and active engagement (Ingersoll et al. 2001).

Without interventions that focus directly on social and play skills within the context of the classroom, children with autism continue to exist in isolation even though they are within a rich social environment (Goldstein et al. 1992; Gresham 1984; Pierce and Schreibman 1997a). Even when placed in an integrated setting and without specific intervention to promote socialization, children with ASD are unlikely to attend to their peers as models or imitate their actions (DiSalvo and Oswald 2002). Children with autism may not act on play materials or imitate peer actions without a cue, external facilitation, or instruction; however, with prompting and instruction, play skills can improve (Attwood 1998; Brown and Murray, 2001; Koegel et al. 2001; Lewis and Boucher 1995). While social instructions remain lacking in many classrooms, suggestions for promoting social inclusion have become more widely used (Brown et al. 2001).

On a positive note, the results from studies that targeted social peer interactions document success when these programs have been in place. Interventions targeting social skills have been shown to increase peer interactions and enhance social play output in children and youths with ASD. Results from many studies have demonstrated the positive gains from directly addressing social interactions in school settings. These works provide support for a variety of strategies that have effectively increased class participation and social interaction for children with autism. In one study, assigning children into cooperative groups with typical peers and providing structured playgroups led to improved social interactions between the targeted children and peers improved (Frea et al. 1999). Others successfully increased social interaction of preschoolers with autism by teaching peer imitation (Garfinkle and Schwartz 2002). One study that took place on school playground demonstrated the positive effects of infusing high preference activities or obsessions of children with autism into appropriate playground games Baker et al. (1998). The results showed that children who initially isolated themselves during outdoor play began to interact with peers during the high preference activity. The target children then generalized improved interactions to other, non-targeted playground activities. This research shows us that with direct support and during typical classroom routines, many children with autism can learn important social skills to improve their peer interactions.

With the shift toward more inclusive opportunities for individuals with ASD there has been an increase in use of peer-mediated strategies to facilitate and encourage social interactions. Researchers have discovered peer-mediated interventions have produced longer exchanges (Strain et al. 1981) and result in better generalization and maintenance of social interactions than adult-mediated interventions (McEvoy et al. 1992; Strain and Fox 1981; Strain et al. 1981). A primary objective of including peers as intervention agents is to increase social participation in naturalistic settings without allowing the children to isolate themselves or rely on teachers for prompting (Strain and Kohler 1998). Peers have been valued contributors to the acquisition of social and play skills in children with autism. The ultimate goal of social skills training is for children to be able to interact within their natural social contexts, thus it is only natural to use typically developing peers as social skills trainers (Rogers 2000). With the classroom as the system, peers are included as important stakeholders in the behavior change of the target individual (Carr et al. 2002) leading to better generalization and long-term success.

To date naturalistic techniques have been studied and implemented within the classroom, home, or clinical setting where variables can be closely monitored and controlled (Koegel et al. 2006). Due to the emergence of standards based instruction typical elementary classroom interactions are now limited to large or small group core academic tasks. In addition, elementary general education teachers seldom address social or play skills within the classroom setting, often the most critically challenging deficit in autism and the most necessary to address. With the blending of inclusion and standards based instruction it is essential to teach play and social skills where they naturally occur, on the playground. This study is one of the few to train typically developing peers to implement naturalistic techniques to address social and play skills on the playground where play naturally occurs within the general education elementary school setting.

Individuals, small groups, and classrooms of peers have learned a variety of teaching techniques and consequently have assisted children with ASD in learning a variety of social skills through their involvement in the intervention process. These methods have increased the social skills of the target children and also the quality of social interactions between their non-disabled peers. Trained peers accurately initiated, gained attention, acknowledged, and provided opportunities for social communication. When these skills were learned, social interactions, including joint attention, between children with autism and typical peers were improved during free play activities (Goldstein et al. 1992; Pierce and Schreibman 1995). Parents have been assisted in teaching peers and children with autism to share, play, and spend time together (Kohler et al. 2005). Using scripts, visual support and reinforcement small kindergarten and first grade peer groups were trained to greet, imitate, follow instructions, share, take turns, and request assistance (Gonzalez-Lopez and Kamps 1997). Interventions including disability awareness and peer training have shown effective in improving interactions between children with autism and their non-disabled classmates (Laushey and Heflin 2000).

While there have been successful, documented cases addressing social skills of children with autism in classrooms, the majority of this work has been done for young children in preschool and kindergarten. Less effort has been seen to support students with ASD in the upper grades, beginning with elementary school. As children become older academic instruction becomes a central focus and less time is spent in free play. In higher grades, social skills instruction is not a focus and needs to be explicitly taught. With the change in curriculum and class schedule, many of the strategies described in previous works may not be conducive to implement in higher grade levels due to the lack of play opportunities within the context of a primary classroom, unless it was a part of the child’s Individualized Education Program (IEP) and the instruction took place outside of classroom instruction time.

Pivotal Response Training (PRT) is one method that has shown to be feasible to implement during naturally occurring routines and settings to improve social communication (Koegel et al. 1989; Koegel et al. 2006; Pierce and Schreibman 1995, 1997a, b). PRT, which is based in Applied Behavior Analysis and incorporates motivational procedures to improve responding, has been used to significantly increase language use and promote positive exchanges between the target children with autism and peers (Pierce and Schreibman 1995, 1997a, b). Social initiations have been considered a pivotal skill and a prognostic indicator for favorable outcomes (Fredeen and Koegel 2006; Koegel et al. 1999). An emerging body of research highlights the importance of teaching initiations to children with autism to facilitate independence. Another important area of focus has been on improving play skills for children with ASD through the use of naturalistic teaching methods (PRT). Stahmer (1995) has shown the positive affects when PRT techniques were applied to play behaviors. Improving communication and teaching appropriate play behaviors may result in better peer interactions. High-functioning children with autism learned to initiate social interactions with peers which led to increased play and decreased disruptive behaviors (Oke and Schreibman 1990); however, most of the previous work targeted increasing appropriate play interactions with peers by training peers to initiate play interactions with the target individuals where as the present study focused on peer-mediated strategies to increase play initiations between children with ASD and their non-disabled peers.

The current study investigated the use of PRT strategies as a social skills intervention package for elementary aged children with autism. The purpose of this study was to examine what happens when typically developing peers are trained to use naturalistic strategies associated with motivating children with autism in the context of play. This study expands the research base on peer implemented naturalistic strategies in several ways. First, the participants in this study were elementary aged students with and without disabilities whereas previous work focused on younger aged groups. Second, this study addressed a time of the school day when children with ASD are often isolated and removed from the structured activities, namely recess. Recess involves unstructured free play, direct instruction does not occur and instructional aides often take breaks leaving the student with autism alone on the playground without support. The intervention in this project combined the use of naturalistic strategies with peer implementation during a time that social intervention is necessary. It was expected that a group of peers without disabilities could learn the components of PRT and apply them into interactions with classmates with autism during unstructured recess activities. It was hypothesized that the participant children with autism would increase social play, specifically, initiating play, and take more appropriate turns with their typically developing peers as a result of teaching the peers to utilize naturalistic techniques associated with increasing motivation.

Methods

Participants

The participants for this study were two fully included third grade students each with a diagnosis of autism from an agency that was not associated with this research. Criteria for participant selection included a diagnosis of autism, educational placement in an inclusive setting, and an existing educational program with goals of social skill development. Both participants attended a kindergarten through sixth grade elementary school within a diverse urban school district outside of Los Angeles, California. They attended school 6 h a day and were fully included within a general education third grade classroom. During the school day the children were involved in academic tasks along with the general education third graders and participated in recess three times a day. The children received instruction from one classroom teacher, a resource special education teacher. Participant two received additional support from a one-on-one instructional aide to provide instructional and behavioral support throughout the school day.

Participant 1

Brian was an 8-year 6 month-old Vietnamese boy whose family spoke English at home. Brian spoke in simple sentences and produced some delayed echolalia. He received academic support from the resource special education teacher and inclusion support from the K-6 teacher. Academically Brian was working on grade level within the core content areas of math, social science, and science. He engaged in some self-stimulatory behavior including vocalizations and body movements during class. Socially Brian infrequently and inappropriately interacted with peers. During recess Brian typically wandered around the playground alone, watched other children play, and engaged in self-talk. He was able to engage in brief conversations with adults or peers although this occurred infrequently. To initiate he would sometimes follow adults or peers on the playground. When he did initiate social interactions, his behaviors were inappropriate. For instance, he would walk up behind an adult or peer with his arms extended and put his arms under the person’s armpits. When he became upset, he growled at peers to avoid social interactions. With adult prompting, Brian would join peers in parallel play or engage in a playground activity for a brief duration. At other times, Brian refused to share equipment and engaged in aggressive behavior (e.g., screaming, hitting) if peers were in close proximity.

Participant 2

Gaven was a 9-year 1-month old Caucasian boy, and was described by teachers and family as having an emerging social awareness. He spoke in simple one to four word phrases and produced immediate and delayed echolalia. He engaged in self-stimulatory behavior including repetitive vocalizations and hand movements. Gaven could not engage in a reciprocal conversation with adults or peers. Academically, Gaven was working approximately three to four years below his chronological age and he received academic support from the resource special education teacher, one-on-one aides, and inclusion support from the K-6 teacher. Within the classroom environment Gaven often imitated peers; however, at recess, he played on the swings or ran around the playground alone. The types of initiations he attempted were inappropriate and consisted of hugging peers. With adult prompting, he engaged in playground routines such as, kickball or basketball for brief periods of time. When frustrated or if his routines were disrupted Gaven engaged in aggressive or non-compliant behavior.

Peer Trainers

Typically developing third grade students served as peer trainers in this study. The peer buddies were classmates of the target participants who were identified by their teachers as students who had regular attendance, were proficient in English, had excellent social and communication skills, and a history of volunteering to help. Six third grade students were selected to participate in the study with a ratio of two peers to one participant and two alternates. The two alternates were available in the event that one of the peer trainers was to drop out of the study or a peer was absent. There were four girls and two boys ranging in ages from eight to nine years old. The peers did not have disabilities, and had similar language and ethnic backgrounds as the participants. Ethnic backgrounds of the peers included Caucasian, Vietnamese, and Indian and all of the peers lived in the same neighborhood as the target students.

Settings and Materials

The study took place in two locations on the school campus including inside a classroom and on the recess playground. The initial social skills peer training sessions took place inside a classroom. Certain play materials provided during these initial trainings inside the classroom were selected so the classroom furniture, wall decorations, and materials would not be damaged. These games included a beanbag toss game, a NerfTM basketball hoop and ball, a ring toss game, and a Velcro ball catch game. Baseline, intervention, and generalization sessions occurred on the playground. Playground play materials consisted of common playground toys and apparatus that were readily available on the school campus such as, a playground ball, basketball, jump rope, basketball hoop and court, and swing set. These playground games were selected based on observations of the students before baseline. Specifically, the target students showed interest in them and they were popular recess games/activities for many of the students.

Training materials provided during the initial training sessions included training cards, and cue cards to help facilitate and structure peer training. The training cards were used to define and clarify each naturalistic technique in child friendly terms. Cue cards were developed for each strategy. The cue cards were used as a tool to help facilitate peers in gaining the attention of their peers with autism and to aid in varying activities and /or choice making. The strategies were represented to the peers pictorially on cue cards, play routine cards, and in simple sentences the children could read.

Experimental Design

A concurrent multiple baseline design across two subjects was used to evaluate the effects of peer mediated naturalistic strategies during play sessions on the number of social behaviors (turn-taking and initiations or gaining attention) produced by the students with autism. This design involved exposing Brian and Gaven to identical baseline procedures then to matching treatment conditions. Baseline data were collected daily until levels stabilized. Intervention data were collected after peers were trained. The intervention phase began when the levels of social behaviors stabilized and when peer buddies mastered the use of the naturalistic strategies. Ten-minute observation and data recording probes were collected from each twenty-minute play period, taken during the first ten minutes of the recess time. During the training phase, the probe began as soon as the adult prompted the peers to play with the target child. During all other phases, the probe began as soon as the recess period began.

Procedures

Baseline

Before naturalistic strategies were presented to the peers, baseline data were collected during recess time on the primary playground. During baseline the participants played on the playground as they typically did during recess periods. No additional prompts or directions were provided. The children could play on all the equipment on the playground (bars, swings, basketball court, handball court, field, etc.). Play duration was timed using a digital timer or stopwatch for 10-min probes. Data were collected for Brian for 13 days and for Gaven for 18 days until data showed a stable pattern for each participant.

Peer Training

Peer training occurred during recess with the first author. There were seven training sessions across seven consecutive school days that lasted 20 min each. The first five sessions took place in a classroom during morning recess without the target child present. For each of the first five days of training, the peers were introduced to one of five teaching strategies that are components of Pivotal Response Training (PRT). These strategies (i.e., gaining attention, varying activities, narrating play, reinforcing attempts, and turn-taking) have been previously used to teach peers to improve social play with children with autism (Pierce and Schreibman 1997b). With each PRT strategy a visual training card and cue card was presented to assist the students in learning the strategy. Training and cue cards are described below. The previously learned strategies were also reinforced during the sessions on the days that followed. So, by the fifth day of training, all five strategies were presented and were reinforced during the training session. The specific PRT strategies presented to the peer trainers included the following:

Gaining Attention

The peers were taught to gain the attention of the child with autism before giving a direction or offering a choice. For example, in an attempt to gain the child’s attention the peers were taught to say the child’s name and then to give the prompts look and listen while making eye contact with the child with autism. Varying activities. The peers were taught to offer the child with autism different play options on the playground using cue cards or by verbally giving the child choices of preferred activities. Narrating play. Peers were shown how to model their own play by commenting and narrating play. They were shown to provide examples of appropriate play with play materials and/or describe what he/she is doing with materials (i.e. “let’s bounce the ball,” or “swinging is fun, lets swing higher”). Reinforcing attempts. Peers were taught to enthusiastically praise the child with autism for any attempt at functional play (i.e. “great dribbling,” “give me five”). Turn-taking. The peers were taught to offer turns within the playground activity or to demonstrate sharing by using the material concurrently with the target children.

Because each of the target participants engaged in challenging behaviors, the peers received training on how to deal with aggressive behavior from target participants. Specifically, the peers were taught that if a peer with autism were to get aggressive they were to back away and to ask for help from an adult. During the study, an adult was always within close proximity to the children and throughout all phases of the study, the target participants did not engage in any challenging (aggressive) behavior.

Opportunities to use these strategies during play were first modeled and described by the researcher. Next, peer trainers were instructed to explain each of the strategies to the researcher; this was followed by role-playing with the researcher and role-playing with the other peer trainers. At the end of each training session, peers were asked to provide the name of each strategy they learned, and answer several questions to ensure understanding and clarity. Criterion level was reached when each peer could demonstrate using the five strategies with at least 80% accuracy and correctly demonstrate providing play opportunities and using the strategies with a classmate who was not involved in the study during the playground training days. Once the first set of peers were trained to criterion then the second set of peers started training. After the peers were trained in all five strategies then an additional two days of training were spent outside on the playground to generalize the skills to the playground setting using the outside play materials and various training cards.

Intervention

Triads were developed comprised of two-third grade peers and one target participant with autism. An alternate was available if a peer was absent or dropped out of the study. Everyday for seven consecutive school days before recess the trainer and/or aides asked the peers to identify and explain the strategies they were to use during play. The peers were also given rings with cue cards on it to remind them of the strategies while they played. During intervention the peers utilized the naturalistic strategies to initiate and maintain play with the target participants, Brian or Gaven, during the morning recess period.

Generalization

Ten-minute generalization probes were taken for 4–5 sessions on the playground in the same manner they had been during baseline, and play sessions resumed under identical physical conditions as baseline. Participants were not given prompts or directions to use the PRT strategies that were taught.

Data Collection

Dependent Variables

The dependent variables measured for the participants were individualized due to their differing abilities and needs. For each participant, the dependent variables were determined through direct observation, teacher input, and individualized social goals. For Participant 1, Brian, the dependent variables were the number of attempts at gaining attention of peers and the number of turn-taking interactions. Gaining attention of peers was defined as independently approaching a peer physically or verbally in a socially appropriate manner (approaching a peer from the front, saying a peer’s name, making eye contact) to gain their attention. Prompted responses of gaining attention were not included. Turn-taking was defined as a social exchange within a play activity (kicking the ball back and forth or taking turns shooting the ball on the basketball court). Each time the target child independently took his turn, or waited and observed while the peer partner took a turn, it was counted as one occurrence. Prompted responses of taking a turn were not included.

The dependent variables measured for Participant 2, Gaven, included the number of initiations to play and the number of turn-taking exchanges. An initiation to play was defined as any appropriate verbal or non-verbal attempt to gain a peer’s attention to initiate or engage in a play activity. Examples included eye contact, showing of toys, verbal bids and sharing materials. Turn-taking was defined for Participant 2 in the same way as for Participant 1.

For each participant, initiation and turn-taking data were collected through event recording of 10-min probes during the morning recess period. Data were recorded and coded in-vivo.

Inter-observer Agreement

During each phase of the study, two observers independently and simultaneously scored each occurrence of the target behaviors exhibited by each child with autism. The first author served as the reliability coder for each participant. An agreement was defined as both observers recording the occurrence of the target behavior. A disagreement was defined as one observer recording an occurrence and the other observer not recording an occurrence of the target behavior. Inter-rater reliability was calculated for at least one third of sessions across experimental phases for each participant. Inter-rater reliability was calculated using the formula of agreements divided by the number of agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100.

For Participant 1, Brian, the inter-observer agreement of gaining peer attention was 94% with a range from 83% to 100% and for turn-taking was 92% with a range from 81% to 100%. Inter-observer reliability data were collected during 12 sessions over the course of all phases of intervention. For Participant 2, Gaven, the inter-observer agreement of initiations to play was 93% with a range of 78–100% and for turn taking was 92% with a range of 80–100%. Inter-observer reliability data were collected on 13 sessions over the course of all phases of intervention.

Fidelity of Implementation

To ensure that the intervention was appropriately administered, fidelity of implementation on the peers’ use of strategies was taken throughout the intervention phase. During peer training sessions fidelity of implementation of naturalistic strategies were measured by the peer trainer. As mentioned, training sessions occurred until peers were able to perform four of the five naturalistic strategies (turn-taking, paying attention, narrating play, reinforcing attempts) with at least 80% mastery out of 10 opportunities. An opportunity was defined by each turn with the play materials the peer had. With each turn, the peer had control over the stimulus items and opportunities for the use of social interaction and initiations were present. For the fifth strategy, varying activities, correct implementation was considered if the peer varied the activity twice during the probe. This criterion was established due to the number of opportunities (approximately 2) that naturally occurred during 10-min observations of recess play.

Peer partners were evaluated on fidelity of implementation throughout the intervention phase for more than one third of all sessions for each participant. Fidelity was recorded using a checklist of each of the five motivational strategies. While the children were engaged in play, opportunities to incorporate the naturalistic teaching techniques were noted and, the peer received a correct score if he or she incorporated the naturalistic teaching technique, and an incorrect score was received if the peer did not incorporate the technique. A total of ten opportunities or missed opportunities were scored. If the peer did not provide opportunities, respond to, or interact with the target participant, it was considered incorrect. The total fidelity of implementation score was calculated by summing the number of correct scores divided by the number of naturalistic strategies and then multiplying by 100. The average fidelity score was calculated for each peer trained play partner by summing the percent scores across each day of assessment and dividing by the number of fidelity probes collected. Table 1 presents the fidelity of implementation scores across sessions for each participant peer. Average scores would show that all peers mastered all of the techniques with the exception of one peer who scored just below criterion on narrating play.

Results

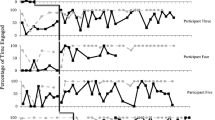

The results indicate that both participants improved their social peer interactions during recess following a peer mediated, naturalistic intervention program with Participant 1, Brian showing greater gains than Participant 2, Gaven. Figure 1 presents the data for the social initiations for each participant. Specifically, the upper graph depicts the data collected for the target behavior of gaining peer attention for Brian and the lower graph depicts the data collected for the target behavior of initiations to play for Gaven. During baseline both participants engaged in social interactions of the target behaviors at low levels. They each demonstrated improved skills during intervention and maintained the skills during the generalization phase.

For Brian, he initiated to gain peer attention never or once during each baseline probe. After peer training intervention program, his social behavior of gaining peer attention rapidly increased to a mean of 4.8 occurrences per 10-min probe during the intervention phase. For example, when his peers walked out toward the playground, Brian approached them, asked what they were going to play, and walked with them to the activity. These improvements maintained during the generalization phase with a mean score of 4.6 occurrences with no zero occurrences as in the baseline period. During the generalization probes, Brian approached peers to join in activities that peers were already engaged in. For instance, he stood in the line, waited for his turn, and played handball. Everyday, he was independently seeking out play opportunities.

During baseline, Gaven demonstrated some variability in his social skills with peers ranging from zero initiations to several with an average of less than one per probe. After the peer mediated intervention program, his social behaviors doubled and steadily increased throughout the intervention probes. Before intervention Gaven did not use peer names when interacting with peers. After intervention Gaven approached peers and referred to them by name, and then initiated interaction (e.g., “Brian, chase me”). Gaven showed continued improvement during the generalization probes. The mean for initiations to play was 3.25 and there were no probes in which Gaven did not initiate to play with peers as there were during baseline. While his improvements were minimal, he demonstrated gains in the core social deficit of autism and pivotal area of initiations.

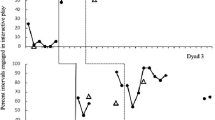

Figure 2 presents the data on turn-taking behavior for both participants with the upper graph representing the data for Brian and the lower graph representing the data for Gaven. Both participants increased their turn taking play skills with peers across the phases of the study.

Baseline results indicate that Brian was not taking any turns independently across all baseline probes. After the peer mediated intervention his level of turn taking dramatically increased to a mean of 12.5 acts per 10-min session. According to the generalization data Brian’s mean score for turn taking remained well above baseline at10.2 acts per 10-min session.

Baseline results indicated that like Brian, Gaven was not taking any turns with peers during recess across all baseline probes. Following the peer mediated intervention he took at least one turn independently with peers and increased to an average of 1.5 acts per 10-min probe. Gaven showed additional gains during generalization probes with a mean score of 2.5 turn-taking acts per 10-min probe. Gains for Gaven were small in this skill, as they were with initiations; however, he showed small and gradual improvement across experimental phases.

In addition to the quantitative data, social validation was considered through anecdotal reports for each participant. Following the peer-mediated interventions, Brian engaged in appropriate recess activities that he had not been observed during the baseline phase nor prior to participation in the study. These behaviors included independently initiated asking peers to play, waiting in line to play organized games (i.e., handball). Additionally, after the intervention, Brian learned appropriate means of refusing social interactions by verbally rejecting peer bids rather than his previous behavior of growling at peers when he did not want to interact.

For Gaven, anecdotal reports showed that his interests during recess play expanded following the intervention program. Whereas prior to intervention, he was only observed to swing or to play chase games, after intervention he would play these games and also would play handball, kickball, and basketball which were more age appropriate and popular on the play ground.

Discussion

The results of this study showed that peer implemented naturalistic strategies were effective at increasing social interactions for children with autism during recess play activities. Both participants improved their social contact with typical peers and in particular, increased their social initiations to play from baseline levels to intervention. These findings add to the growing research bases of peer mediated (DiSalvo and Oswald 2002; Goldstein et al. 1992; Kohler et al. 2005; Kamps et al. 2002; Strain and Kohler 1998) and naturalistic strategies (Brown and Odom 1995; Pierce and Schreibman 1997a, b) to increase children’s social play behaviors. The results also pointed toward the beginning of a sustainable outcome. After the intervention and training components were withdrawn, the target children maintained their increased levels of initiating and responding during generalization probes. These findings fit with previous studies suggesting how formation of social interactions and development of friendships begin (Guralnick 1990; Hurley-Geffner 1995; Kennedy et al. 1997; Kennedy and Itkonen 1996; Rogers and Lewis 1989). Specifically, the current study provided several of the components including proximity, mutually reinforcing events, and reciprocity that have been identified as those that can ultimately lead to friendships (Hurley-Geffner 1995; Kennedy and Itkonen 1996; Rogers and Lewis 1989). The targeted social skills, initiations and turn-taking, are behaviors that may have provided the participants with skills leading to equal roles or reciprocal interactions which have been found to be important aspects of social competence (Guralnick 1990; Kennedy and Itkonen 1996).

Kohler et al. (2005), in a recent study of peer-mediated techniques mentioned characteristics that may positively affect the success of peer-mediated procedures in inclusive settings. The results from the present work incorporated several of those mentioned, namely large-scale application and practical application for teachers. Although the intervention did not apply to the entire school, the initial steps toward this goal were in place. The inclusion of multiple peers as opposed to a single trained peer is one component of the intervention that likely contributed to the positive findings. Inclusion of peers creates buy-in and also divides the responsibility of integration across many individuals. Buy-in refers to the engaged participation and contribution of the peers who were directly involved in the intervention. By learning how to create interactive play opportunities, the peers were stakeholders in aiding the students with autism to be active participants within the recess period. Having a group of students supporting one classmate with autism may provide a better ratio and enhance the motivation for the typical peers. In a group, the peer partners may enjoy working together to support the individual with autism more than if they were playing with the target child alone. Additionally, for the age of the participants and considering the types of games that are popular at recess, children on the playground are often seen playing together in small groups.

With regard to the practical application for teachers, this information was noted anecdotally through interactions with the teachers. In less than two weeks, the training was completed and the activities fit in well with the natural structure of the school routines. The relative ease of training peers within a brief period of time is a strength of the present study. Using peer groups as a model of service delivery could expand the existing resources and reduce the need for costly and possibly stigmatizing individualized adult support during certain times of the school day. Future studies should consider assessing the costs and benefits of implementing peer-implemented techniques to increase social relationships for students with ASD. Additionally, peer interactions are more naturalistic and allow for better generalization of social relations than adult mediated support. Results from a body of literature suggests that individualized assistants often hover over the target children reducing their opportunities for natural social interactions with peers. On the other hand, peer mediated strategies may enhance and increase the opportunities for children with ASD and those without disabilities to interact together (Giangreco 1997; Koegel 2006).

To explain the positive results obtained from the generalization probes we are directed at the use of peer groups, the use of naturalistic techniques, and the natural play context. According to Terpstra et al. (2002) the more naturalistic the training situation the more likely generalization and maintenance will occur, which was evidenced within this study. In a school setting, having peers implement procedures is more naturalistic and more motivating then if adults would have implemented the same procedures. Rather than teaching social skills in an artificial setting or using artificial reinforcers, this study taught social skills in the setting in which the skills were to be performed and with social reinforcement. It may be easier for students with autism to generalize the skills if they are implemented in a naturalistic environment with individuals who are natural to the environment and through activities they enjoy.

On a broader note, the use of peers as intervention delivery agents could have a significant impact on the implementation and delivery of services to children with autism within inclusive settings. Peer-implemented procedures enable students with autism to be a part of the natural school climate. They also foster greater independence. The responsibility for teaching social play shifts away from adult support and transfers to the peer group as well as to the target child with autism.

As with any applied research study, there are several limitations. First, the ability to generalize the findings to a wide population is limited due to the small sample size of only two participants. Only two participants were included as a result of recruitment efforts for the study. This study took place on a school campus and during typical play activities and only two participants fit with the selection criteria for the proposed study. Application of these strategies to a diverse population of students with ASD may allow for wider generalization of the techniques.

Although both target children responded positively to the intervention, for one participant the gains were greater. Participant 1, Brian, showed greater and more rapid improvement over baseline levels compared to Participant 2, Gaven. It is possible that for students with higher cognitive abilities or verbal skills, like Brian, these skills may enhance the effects of the intervention whereas for children with lower cognitive and language skills additional time or intervention strategies may be required. Future studies could assess whether this type of intervention may be more suitable for individuals with certain prerequisite skills, interests, or abilities. Future studies may also include several students who are lower functioning and may include additional support for the participants. Second, when conducting research in a natural setting such as on the school play yard many external variables exist which are difficult to control. In this study examples of extraneous factors included other peers wanting to join in the play activities and difficulty in unobtrusive data collection. Social affect ratings were not collected because the data were conducted in-vivo in a school setting and use of video cameras was not possible on the school campus to obtain consent from the students. The external variables can account for some moderately unstable baseline data and implementation data for Participant 2. The third limitation of the study was the lack of long-term generalization data due to the termination of the school year. In order to assess the lasting effects one would need to collect additional generalization probes, at times further removed from the training. On a positive note, the results indicated that both students maintained gains under generalized conditions and their skills continued to improve after the intervention one month following the peer-training program. Even the slight gains across phases made by participant two are those that address the core issues and challenges of autism. Learning to initiate and take turns with peers are key skills in social skills.

In spite of the limitations, this study offers promising results about the potential to increase social opportunities, improve the quality of peer interactions, and foster independence for students with ASD. In addition, this study addressed recess, a routine that exists at all schools and often times presents explicit challenges for students with ASD and their team members to create social opportunities during unstructured play. This project provides a feasible intervention plan to train a group of peers within a relatively short period of time. The findings add to a valuable body of literature assessing the benefits of providing instruction with general education classmates and within the general education setting. These participants were included throughout the day in classrooms with students without disabilities and the positive results may have been affected through the familiarity that the classmates had with each other. The inclusion of peer groups may also build sustainability within the system of support for the target students. In cases of students who are not included in general education and only share space with non-disabled peers during non-academic periods, like recess, it is unknown whether the results would be as promising. Additional work in other educational settings may answer that question.

This quantitative analysis showed that both participant children improved their social interactions during unstructured recess times when they had previously spent the majority of recess time alone. Future research using qualitative evaluation should examine the effects of peer-implemented procedures on peer perceptions of classmates with autism, as well as, peer benefits. To understand the variables that were most responsible for the positive change, further research should also evaluate the effects of naturalistic peer-implemented interventions on the playground alone versus the combination of this treatment with adult implemented interventions. It may be found that a combination intervention may be more suitable for students with more severe autism where as the present study showed that peer-implemented strategies were successful for both target children. Considering that socialization with peers may be the most challenging aspect of life for children with autism and the greatest concern for families, this is an important area of research. While a primary goal of education is to learn the core curriculum, social skills are necessary to achieve a productive place in a community. After all, when looking back on one’s school years, perhaps the greatest memories are those that were made and shared with friends on the play yard.

References

Attwood, T. (1998). Asperger’s Syndrome: A guide for parents and professionals. Great Britain: Athenaeum.

Baker, M. J., Koegel, R. L., & Koegel, L. K., (1998). Increasing the social behavior of young children with autism using their obsessive behaviors. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 23(4), 300–308.

Brown, J., & Murray, D. (2001). Strategies for enhancing play skills for children with autism spectrum disorder. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 36(3), 312–317.

Brown, W., & Odom, S. L. (1995). Naturalistic peer interventions for promoting preschool children’s social interactions. Preventing School Failure, 39(4), 38–43.

Brown, W. H., Odom, S. L., & Conroy, M. A. (2001). An intervention hierarchy for promoting young children's peer interactions in natural environments. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 21(3), 162–175.

Carr, E. G., Dunlap, G., Horner, R. H., Koegel, R. L., Turnbull, A. P., Sailor, W., Anderson, J. L., Albin, R. W., Koegel, L. K., & Fox, L. (2002). Positive behavior support: Evolution of an applied science. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 4(1), 4–16.

DiSalvo, C., & Oswald, D. (2002). Peer-mediated interventions to increase social interaction of children with autism: Consideration of peer expectancies. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 17(4), 198–207.

Frea, W., Craig-Unkefer, L., Odom, S. L., & Johnson, D. (1999). Differential effects of structured social integration and group friendship activities for promoting social interactions with peers. Journal of Early Intervention, 22(3), 230–242.

Fredeen, R. M., & Koegel, R. L. (2006). The pivotal role of initiations in habilitation. In R. L. Koegel & L. K. Koegel (Eds.), Pivotal response treatments for autism: Communication, social, and academic development (pp. 165–186). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Garfinkle, A., & Schwartz, I. (2002). Peer imitation: Increasing social interactions in children with autism and other developmental disabilities in inclusive preschool classrooms. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 22(1), 26–38.

Giangreco, M. F., Edelman, S. W., Luiselli, T. E., & MacFarland, S. Z. C. (1997). Heping or Hovering? Effects of instructional assistant proximity on students with disabilities. Exceptional Children, 64(1), 7–18.

Goldstein, H., Kaczmarek, L., Pennington, R., & Shafer, K. (1992). Peer-mediated intervention: Attending to, commenting on, and acknowledging the behavior of preschoolers with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25(2), 289–305.

Gonzalez-Lopez, A., & Kamps, D. (1997). Social skills training to increase social interactions between children with autism and their typical peers. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 12(1), 2–14.

Gresham, F. M., (1984). Social skills and self-efficacy for exceptional children. Exceptional Children, 51, 253–261.

Guralnick, M. J. (1990). Social competence and early intervention. Journal of Early Intervention, 14(1), 3–14.

Hurley-Geffner, C. M., (1995). Friendships between children with and without developmental disabilities. In R. L. Koegel & L. K. Koegel (Eds.), Teaching children with autism: Strategies for initiating positive interactions and improving learning opportunities (pp. 105–125). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Ingersoll, B., Schreibman, L., & Stahmer, A. (2001). Brief report: Differential treatment outcomes for children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder based on level of peer social avoidance. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(3), 343–349.

Kamps, D., Royer, J., Dugan, E., Kravits, T., Gonzalez-Lopez, A., Garcia, J., Carnazzo, K., Morrison, L., & Kane, L. G. (2002). Peer training to facilitate social interactions for elementary students with autism and their peers. Exceptional Children, 68(2), 173–187.

Kennedy, C. H., Cushing, L., & Itkonen, T. (1997). General education participation improves social contacts and friendship networks of students with severe disabilities. Journal of Behavior Education, 7(2), 167–189.

Kennedy, C. H., & Itkonen, T. (1996). Social relationships, influential variables, and change across the life span. In L. K. Koegel, R. L. Koegel, & G. Dunlap (Eds.), Positive behavioral support: Including people with difficult behavior in the community (pp. 287–304). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Koegel, R. L., Klein, E. F., Koegel, L. K., Boettcher, M. A., Brookman-Frazee, L., & Openden, D. (2006). Working with paraprofessionals to improve socialization in inclusive settings. In R. L. Koegel & L. K. Koegel (Eds.) Pivotal response treatments for autism: Communication, social, and academic development (pp. 189–198). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Koegel, L. K., Koegel, R. L., Frea, W. D., & Fredeen, R. M. (2001). Identifying early intervention targets for children with autism in inclusive school settings. Behavior Modification, 25, 745–761.

Koegel, L. K., Koegel, R. L., Shoshan, Y., & Mcnerney, E. M. (1999). Pivotal response intervention II: Preliminary long-term outcomes data. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 24(3), 186–198.

Koegel, R. L., Openden, D., Fredeen, R. M., & Koegel, L. K. (2006). The basics of pivotal reponse treatment. In R. L. Koegel & L. K. Koegel (Eds.), Pivotal response treatments for autism: Communication, social, and academic development (pp. 3–30). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Koegel, R. L., Schreibman, L., Good, A., Cerniglia, L., Murphy, C., & Koegel, L. K. (1989). How to teach pivotal behaviors to children with autism: A training manual. Santa Barbara: University of California.

Kohler, F. W., Strain, P. S., & Goldstein, H. (2005). Learning Experiences . . . An alternative program for preschools and parents: Peer-mediated interventions for young children with autism. In E. D. Hibbs & P. S. Jensen (Eds.), Psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent disorders: Empirically based strategies for clinical practice (2nd ed., pp. 659–687). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Laushey, K., & Heflin, J. (2000). Enhancing social skills of kindergarten children with autism through the training of multiple peers as tutors. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(3), 183–193.

Lewis, V., & Boucher, J. (1995). Generativity in the play of young people with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 25(2), 105–121.

Libby, S., Powell, S., Messer, D., & Jordan, R. (1998). Spontaneous play in children with autism: A reappraisal. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 28(6), 487–497.

McEvoy, M. A., Odom, S. L., & McConnell, S. R. (1992). Peer social competence intervention for young children with disabilities. In S. L. Odom, S. R. McConnell, & M. A. McEvoy (Eds.), Social competence of young children with disabilities: Issues and strategies for intervention (pp. 113–134). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Oke, N. J., & Schreibman, L. (1990). Training social initiations to a high-functioning autistic child: Assessment of collateral behavior change and generalization in a case study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 20(4), 479–497.

Peeters, T. (1997). Autism: From theoretical understanding to educational intervention. San Diego: Singular Publishing Group.

Pierce, K., & Schreibman, L. (1995). Increasing complex social behaviors in children with autism: Effects of peer-implemented pivotal response training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 28(3), 285–295.

Pierce, K., & Schreibman, L. (1997a). Using peer trainers to promote social behavior in autism: Are they effective at enhancing multiple social modalities? Focus on Autism & Other Developmental Disabilities, 12(4), 207–218.

Pierce, K., & Schreibman, L. (1997b). Multiple peer use of pivotal response training to increase social behaviors of classmates with autism: Results from trained and untrained peers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 30(1), 157–160.

Rogers, S. (2000). Interventions that facilitate socialization in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(5), 399–409.

Rogers, S. J., & Lewis, H. (1989). An effective day treatment model for children with pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 28(2), 207–214.

Stahmer, A. (1995). Teaching symbolic play skills to children with autism using pivotal response training. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 25(2), 123–141.

Stone, W., Lemanek, K., Fishel, P., Fernandez, M., & Altemeier, W. (1990). Play imitation skills in the diagnosis of autism in young children. Pediatrics, 86(2), 267–272.

Strain, P. S., & Fox, J. J. (1981). Peers as behavior change agents for withdrawn classmates. In B. B. Lahey & A. E. Kazdin (Eds.), Advances in clinical child psychology (pp. 167–198). New York: Academic Press.

Strain, P. S., Kerr, M. M., & Ragland, E. U. (1981). The use of peer social initiations in the treatment of social withdrawal. In P. S. Strain (Ed.), The utilization of classroom peers as behavior change agents (pp. 101–128). New York: Plenum Press.

Strain, P. S., & Kohler, F. (1998). Peer-mediated social intervention for young children with autism. Seminars in Speech and Language, 19(4), 391–405.

Terpstra, J., Higgins, K., & Pierce, T. (2002). Can I play? Classroom-based interventions for teaching play skills to children with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 17(2), 119–126.

Veale, T. (1998). May I have your attention please? Language and learning lessons from one child with autism. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Cincinnati.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the school, teachers, children and their families for their participation in this study. We are grateful for your dedication to improve the lives of all children at school. This article is based on a thesis completed by the first author for the degree of Master of Arts in Special Education with an emphasis in Autism at California State University, Los Angeles.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harper, C.B., Symon, J.B.G. & Frea, W.D. Recess is Time-in: Using Peers to Improve Social Skills of Children with Autism. J Autism Dev Disord 38, 815–826 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0449-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0449-2