Abstract

Children with autism often display differences in functional and symbolic play and may experience barriers to social inclusion with peers in preschool settings. Therefore, interventions supporting social play between children with autism and their peers that can be feasibly implemented by teachers in inclusive settings are needed. A teacher-implemented peer-mediated Stay Play Talk (SPT; Goldstein et al. in Top Lang Disord 27(2):182–199, 2007) intervention package targeting the type of play children with autism engage in with peers was implemented using a concurrent multiple baseline design across four participant/peer dyads. Using a cascading coaching model with behavioral skills training, a teacher was trained in intervention strategies and then taught and supported four peers to implement the intervention. In addition to visual analysis, to statistically analyze effects, we calculated effect sizes using the parametric measure standardized mean difference. A functional relation between the intervention and increases in interactive play and initiations and decreases in solitary play was demonstrated across all dyads. Results generalized to novel settings and maintained following withdrawal of teacher support. Results suggest that SPT can be effectively implemented by a teacher to support interactive play between children with and without autism in an inclusive classroom. Implications for future research and clinical practice are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

For typically developing (TD) children, play skills develop in a predictable sequence and hierarchy of increasingly complex skills often categorized into six stages: unoccupied play, solitary play, onlooker play, parallel play, associative play, and cooperative play (Howes & Matheson, 1992; Parten, 1932). Although play skills advance in a hierarchal manner in TD children, children with autism often show delays in the development of play skills and have difficulties with play-based activities which may create barriers to inclusion with peers in early childhood (Baron‐Cohen, 1987; Fedewa et al., 2022). Young children with autism spend less time in parallel and cooperative play with peers and display less diversity in play actions when compared to their TD classmates (Charlop et al., 2018). When in proximity to peers, some children with autism often have difficulties initiating, sustaining, and responding to peer play (Sigman et al., 1999; Wolfberg et al., 2012). When children with autism engage in play activities, it is often stereotyped and repetitive in nature and frequently focuses on their restricted interests, creating limited opportunities for engagement with peers in play (Jung & Sainato, 2015).

Given the importance of play and peer interaction for all children, strategies to support play skills and provide positive peer experiences for children both with and without autism in inclusive classrooms are necessary. Interventions in inclusive settings are especially important, as instruction in the natural environment may help skills maintain over time and generalize beyond the intervention context (Vincent et al., 2022). One evidence-based approach to teaching play skills to children with autism in inclusive settings is through peer-mediated interventions ([PMI], Steinbrenner et al., 2020; Watkins et al., 2015), which involves teaching TD peers to prompt, reinforce, and model target social skills to a partner with disabilities (Odom & Strain, 1984). PMI can increase play initiations, turn-taking behaviors, and engagement in social play in young children with autism (e.g., Ganz & Flores, 2008; Watkins et al., 2023) and offer many benefits in inclusive settings. Teaching peers to better interact with and support children with autism can place fewer instructional demands on teachers, while providing multiple opportunities for students with autism to interact and use social skills with a variety of peers, potentially increasing the likelihood of generalization of skills across novel peers and settings (Carr & Darcy, 1990; Hemmeter, 2000; Strain & Kohler, 1998; Watkins et al., 2015). Finally, teaching TD children to model appropriate social skills with classmates with disabilities can be mutually beneficial and potentially lead to more reciprocal relationships in the classroom environment (Bowman-Perrot et al., 2023).

Stay Play Talk (SPT) is a PMI strategy often implemented in inclusive early childhood settings in which peers are taught to stay in proximity to their partner, play with their partner, and talk to their partner (Goldstein et al., 2007). SPT is designed to be simple and requires few steps to allow for natural social interactions between peers and young children with disabilities in free-play contexts, which decreases demands for teacher support (Ledford & Pustejovsky, 2023). Although SPT has been successfully implemented with young children with autism and other disabilities and increased social skills such as initiations, responses, play skills, and language skills (Ledford & Pustejovsky, 2023), there is still a need for further exploration. A systematic review and meta-analysis examined nine single case experimental design (SCED) interventions using SPT as the main intervention method (Ledford & Pustejovsky, 2023). The majority of SPT interventions were implemented in preschool settings; yet, the review identified only two studies directly examining play skills, with most examining communicative behaviors such as initiations and responses. Milam (2018) employed a multiple probe design to examine peer buddies’ use of SPT strategies and found increases in the duration of play among socially isolated students in early childhood classrooms. This intervention successfully increased social play for all participants, and the results were maintained and generalized. Yet, this study did not include children with a diagnosed disability or autism. Severini et al. (2019) taught TD peers to use SPT strategies with two students with Down syndrome who used augmented and alternative communication devices and found increases in play behaviors for participants.

Although SPT has been successful in early childhood classrooms in previous studies, the majority of SPT interventions were implemented by researchers and did not involve practitioners in the peer training and implementation of the intervention (Ledford & Pustejovsky, 2023). Prior reviews and meta-analyses of school-based play and social skill interventions for children with autism found interventions implemented by teachers produced stronger effects than those implemented by researchers alone (Fedewa et al., 2022; Watkins et al., 2019a, 2019b). Yet, teachers report access to training and resources as a main barrier to implementing evidence-based practices for students with autism (Knight et al., 2019). As inclusive practices increase, there is a pressing need to develop training protocols to support teacher implementation of evidence-based practices such as PMIs with fidelity to reduce the research-to-practice gap (Guldberg, 2017).

Behavioral skills training (BST) is one such practice that can support improved teacher implementation of evidence-based practices. BST consists of instruction, modeling, rehearsal, and feedback (Leaf et al., 2015), and it has been widely used to train teachers and other service providers to implement interventions for children with disabilities (Slane & Lieberman-Betz, 2021), as well as effectively used to teach a variety of skills and behaviors to children with and without disabilities (e.g., Morosohk & Miltenberger, 2022; Young et al., 2016). The use of BST when used to train teachers to implement interventions has been associated with improved implementation fidelity (Brock & Huber, 2017) and improved child outcomes (Slane & Lieberman-Betz, 2021).

Yet few studies have examined the utility of BST in teaching teachers to train peers to act as intervention agents specifically in the context of PMI. Most of the research in this area has focused on training parents to teach siblings (e.g., Sheikh et al., 2019) or peers (e.g., Raulston et al., 2020) to implement intervention strategies in home settings. In one school-based example, Watkins et al. (2023) used a BST package to train a teacher how to teach TD peers to implement modified SPT strategies, which resulted in an increase in peer social interactions and cooperative play for three elementary school children with autism. However, more work is needed to improve the generality of these findings, especially with younger children. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to extend this research and assess the effects of a BST training package to train a classroom teacher to teach and support peers to implement SPT strategies and to examine the effects of the intervention on various social play outcomes for children with autism. The following research questions were examined:

- Research Question 1:

-

Is a BST package effective in training a teacher to teach and support young peers in the use of SPT procedures?

- Research Question 2:

-

Does the teacher-facilitated SPT intervention increase interactive play and social initiations between children with autism and TD peers?

- Research Question 3:

-

Can peers implement SPT strategies independently following the withdrawal of teacher support?

- Research Question 4:

-

Are potential treatment gains demonstrated during intervention generalized to novel settings and/or maintained post-treatment?

Method

Setting

This study took place in a private inclusive preschool program for children with autism in the Southeastern United States. The preschool classroom served a total of eight children ages four through 6 years old and was comprised of four students diagnosed with autism and four TD students. All data collection sessions took place in the classroom during a time in the daily schedule designated for free-play and/or sensory play activities. The teaching staff in the classroom included two registered behavior technicians (RBTs), and the lead special education teacher who served as the interventionist. In the front of the classroom, there was a small rug where all intervention sessions took place. All sessions across all phases were eight minutes in duration, and data were collected three to four times weekly as therapy and classroom schedules allowed. Institutional review board approval and informed parental consent and child participant assent were obtained for the study.

Participants

Interventionist

A community-based research partner and special education teacher served as the interventionist for this study. The special education teacher was in her third year of teaching and held a master’s degree in early childhood special education and completing coursework to become a Board-Certified Behavior Analysis (BCBA). The teacher served as the 4-year-old preschool classroom teacher. She expressed a need for training to learn how to better implement PMI in her classroom and further support social interactions and play between students with and without disabilities. Researchers met with the teacher to discuss the goals of this intervention to ensure alignment with the learning objectives of her students. The teacher gave feedback to the researchers in selecting the participants and peers included in the intervention and assured times for data collection aligned with the classroom-established schedule.

Participant and Peer Dyads

Four children with autism, hereafter referred to as participants, and four TD students, hereafter referred to as peers, were recruited to participate in the study. Children were included in this study if they (a) had an external medical diagnosis of autism, (b) were between ages four and 6 years of age, (c) had consistent school attendance, “(d) demonstrated low levels of peer interactions (e.g. did not initiate or respond to peers’ initiations to play) during free play activities as reported by the teacher, and (e) tended to spend the majority of free play time in solitary or parallel play as measured by one direct 10-min observation by the researcher. Three males and one female with autism participated in the intervention. Children were included as peers if they (a) had typical language development as reported by the classroom teacher, (b) maintained interest in play activities, (c) exhibited developmentally appropriate play skills as measured by direct observation and teacher report, (d) maintained consistent school attendance, (e) and had a history of positive relationships and interactions with classmates with autism. Four male children participated in the intervention in the role of peers. We paired a participant and peer based on teacher feedback and observations during free-play activities. Dyads 1, 2, and 3, were students in the special education teacher’s class. Dyad 4 students were in a neighboring classroom which followed the same daily schedule.

Dyad 1: Carson & Parker

Carson was a 6-year-old Black male with a diagnosis of autism established using the Autism Diagnostic Observation Scale-Second Edition (ADOS-2, Lord et al., 2012) and a mixed receptive-expressive language disorder. Carson received speech therapy and occupational therapy (OT) one time weekly. His teacher reported he had above-average reading and math skills when compared to same-age peers and had strong visual-spatial skills. Carson enjoyed playing with dinosaurs and superhero toys, building towers and puzzles. During free-play activities, Carson had difficulties initiating conversations and often only responded to peers’ direct questions. He was quiet around peers and struggled to gain friends’ attention and share his opinions or preferences during play. We paired Carson with Parker as a play partner. Parker was a 5-year-old White male who had a history of positive play interactions with Carson. Upon observation of the dyad before the intervention, Carson demonstrated functional play skills and appeared to enjoy participating in play activities, yet he was quiet and mostly observed Parker playing.

Dyad 2: Owen and Jack

Owen was a six-and-a-half-year-old White male with a diagnosis of autism established using the ADOS-2 and a diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Owen had advanced verbal language skills but difficulties with receptive communication and received speech therapy one time weekly. The teacher reported Owen had above-average reading skills when compared to same-age peers and enjoyed going to the park, jumping on the trampoline, and playing with trains or transformers. Owen was highly motivated by social interactions and praise from teachers. When engaging in play with peers, Owen struggled to attend to peers and would ignore his friends when they asked to play with the same toys. The teacher expressed concern about Owen’s ability to have reciprocal friendships, his insistence on leading play and being first, and shared Owen engaged in off-topic conversations with peers or adults. We paired Owen with Jack as a play partner. Jack was a four-and-a-half-year-old White male and had a history of positive play interactions with Owen. When we observed the pair before the intervention, Owen tried to direct the play activities and frequently interrupted Jack. When Owen did this, Jack would stop talking and play independently.

Dyad 3: Noah and Elliot

Noah was a five-and-a-half-year-old White male with a diagnosis of autism established using the ADOS-2. Noah also was diagnosed with a receptive-expressive language disorder and severe articulation disorder. Noah received applied behavior analysis (ABA) therapy three times weekly, speech therapy two times weekly, and OT one time weekly. The teacher reported Noah had strong visual perceptual and imitation skills. He enjoyed playing with character toys and a variety of sensory toys. When in the proximity of same-age peers, Noah had difficulties joining in play activities and engaging in reciprocal conversations. He often used inappropriate strategies to gain attention (i.e. yelling a friend’s name repeatedly or getting mad when he was not chosen first) and had difficulties with functional play behaviors like turn-taking, and appropriate game-playing behaviors. We paired Noah with Elliot as play partners. Elliot was a four-and-a-half-year-old White male who had a history of positive play interactions while on the playground with Noah. Upon initial observation of the dyad, Elliot would often initiate play toward the teacher or researcher but rarely with Noah. Noah spent the majority of time in solitary play and engaged in repetitive and self-stimulatory behaviors (i.e. spinning the wheel on a toy car repetitively). Elliot would observe Noah but appeared to find it difficult to interpret how to interact with him in play.

Dyad 4: Sara and Max

Sara was a 4-year-old White female with a diagnosis of autism established using the ADOS-2 and a diagnosed language impairment. Sara received ABA therapy three times per week, speech therapy two times per week, as well as OT and feeding therapy one time weekly. The teacher reported Sara had above-average reading and math skills when compared to same-age norms. She could read early learner emergent books and was highly motivated by verbal praise from her teachers. She played with a variety of toys in the classroom including Sesame Street characters, Paw Patrol characters, finger puppets, and baby dolls. Her teacher reported Sara had difficulties gaining peer attention, requesting from peers, and engaging in different play activities with peers. She spent the majority of her time in solitary play while in free-play settings in the classroom and on the playground. Sara spoke in two to three-word sentences. We paired Sara with Max as a peer play partner. Max was a 4-year-old White male with a history of positive play interactions with Sara. Upon initial observation of the dyad, we observed Sara engaged in solitary play and would stack two magnets on top of each other repeatedly. Max would observe Sara but he appeared to struggle to interpret Sara’s play behaviors and did not initiate engagement in play.

Materials

Play materials included in the study came from the classroom. Before the baseline phase, the researcher asked for teacher input on the participants’ and peers’ preferences of play materials and then conducted a 20-min free operant preference assessment where the play partners were instructed to play with any toys in the classroom they wanted while the researcher observed and recorded preferences (Roane et al., 1998). As identified during the preference assessment, toys used throughout intervention phases included: blocks and Legos, plastic dinosaurs and action figures, a play train set, and a variety of games and puzzles. A “play menu” was developed to provide a choice of materials to the dyad which consisted of an 8. 5′ × 11′ laminated visual with three Velcro squares where each session, the researcher presented the dyad with three pictures of toys to choose from. During intervention sessions, a personalized SPT visual support was developed and used in each intervention session to remind peers of the SPT strategies. The SPT visual was printed on 8. 5’ × 11’ card stock and laminated. Across the top of the visual were the words “stay, play, talk” and under each word was a photo of the dyad staying next to each other, playing with each other, and talking to each other. Below the photos, a blank space was provided for the teacher to add stickers after each intervention session if the peer successfully implemented each strategy.

Experimental Design

We assessed intervention effects using a concurrent multiple baseline across participant design. (Kennedy, 2005). Conditions included baseline, SPT with teacher support, and SPT with teacher support withdrawn.

Dependent Variables and Data Collection

We collected data on three play behavior-related dependent variables: solitary play, parallel play with social awareness, and interactive play. We also measured verbal initiations for the participant and peer. The definitions for type of play were adapted from Parten (1938) and Howes and Matheson (1992) play hierarchies. Solitary play was operationally defined as the child playing independently without any social involvement with peers or not showing interest in what the peer was doing. If the participant was sitting on the carpet and playing with materials by themselves without observing their partner, the play type was coded as solitary. Parallel play with social awareness was defined as the child playing in proximity to a peer, with the same materials, and referencing or mimicking what the peer partner is doing, but play was not interactive and did not share a common goal. Parallel play was only coded if the participant was looking or talking to a peer but play interaction was not occurring. Interactive play was defined as the participant and peer playing with each other, sharing materials, and sharing a common goal within the play activity. The percentage of intervals the participant engaged in each type of play was measured using momentary time sampling (Ledford & Gast, 2018). Momentary time sampling has been found to closely match continuous data collection methods (i.e. duration recording) when estimating levels of behaviors (i.e., Radley et al., 2015). The 8-min play session was divided into 10-s intervals for a total of 48 intervals within each session. At each 10-s mark, the researcher recorded if the participant was engaged in solitary, parallel, or interactive play. Unoccupied behaviors where the participant was not engaging with materials, attempting to leave the play area, or participating in another activity did not occur. The researcher then calculated the percentage of increments spent in each type of play.

Vocal initiations for the participant and peer were measured using event recording to provide the number of initiations given in each session, and were defined as independently approaching the play partner and verbally attempting to gain a peer’s attention (Ledford & Gast, 2018) Table 1 provides definitions of dependent variables and examples.

Baseline

Before data collection began the teacher explained to the participant and peer they would have the opportunity to engage in play sessions together, introduced the researcher, and written assent was obtained. At the beginning of the baseline session, the teacher instructed the dyad to sit on the carpet and play together. The researcher presented the dyad with a “play menu” and the participant and peer discussed and selected which materials they wanted to play with. The teacher provided no further instructions outside of typical classroom instructions (e.g., instruction to stay on the carpet during playtime or to use appropriate inside level voices). The teacher or researcher did not prompt or reinforce the participant or peer for social or play interactions.

Teacher Training

We used a cascading coaching model in which the researcher used BST to train the teacher in SPT strategies, and the teacher then used BST to train and support the peers in the use of the SPT strategies (Watkins et al., 2023). Teacher training was conducted during the school day, in a single one-on-one 30-min session during the teacher’s planning period. Using a PowerPoint presentation to guide training, the researcher introduced the PMI strategy of SPT and provided an overview of previous research and potential benefits and the goals and targeted outcomes of the current intervention. At this time, we shared baseline data to show engagement in interactive play within the four dyads and discussed play behaviors observed by the participants and peers. This allowed the teacher to provide feedback if the behaviors observed during baseline sessions were consistent with play behaviors demonstrated by participants outside the study conditions, which she confirmed. Next, the researcher provided an overview of using BST to train peers in the SPT strategies and modeled the process. An overview of the training process is provided in Table 2.

Peer Training

After the teacher received training with the researcher, she individually trained each peer in a single one-on-one 40-min training session. The teacher used the steps provided by the researcher in the teacher training session and followed the same BST protocol to teach the peer how to use the SPT strategies to engage in interactive play with their play partner. The researcher provided the teacher with a written checklist of the training procedures. The teacher first praised the student for playing with their partner, introduced the strategy, and then provided information about their play partners’ unique characteristics and behaviors. For example, the teacher explained to Max, that sometimes Sara had a difficult time responding to his initiations to play or when he asked her questions. The teacher instructed Max to gently tap her on the shoulder, say her name, and then ask her a question or give her a toy to initiate play. Next, the teacher taught the peer each step of the SPT intervention using the BST teaching model. For example, for the “stay” step in the intervention, the teacher first explained why it is important to stay near their partner. Next, the teacher and researcher modeled staying together (e.g. the researcher would go to one side of the carpet with a toy train, and the teacher would follow). Next, the teacher and peer practiced staying together and as the teacher moved around the carpet playing with different materials, the peer followed and stayed near her playing with the same material. Finally, the teacher provided the peer with feedback and an opportunity to ask questions before moving to instruction on the “play” step of the intervention (e.g. “I liked how you followed me around the carpet and stayed with me”). The researcher observed each peer training session to measure the teacher’s fidelity of training procedures. The first teacher-supported play session with the participant occurred immediately following the peer training session for each dyad.

SPT with Teacher Support

After the peer received training in the SPT intervention, the dyad entered the SPT with teacher support phase of intervention. In this phase, the teacher prompted and supported the peer’s use of SPT strategies. During these sessions, if 30 consecutive seconds occurred without engagement in play interactions, the teacher prompted the peer using a least-to-most prompting hierarchy. For example, if the dyad was playing with materials but little language was occurring between the partners, the teacher gained the peer’s attention and pointed to “talk” on visual. If the peer did not respond, the teacher gained the peer’s attention again, pointed to the talk visual, and said “give your partner a choice.” Teacher support was withdrawn after two consecutive sessions were completed without the need for prompting and a positive, stable data trend was established. At the end of the play session, the teacher reviewed the strategies with the peer and provided feedback on the use of strategies (e.g.,“ you did a great job staying with your partner and playing with the same toys today, tomorrow try to ask your partner a question”). After providing feedback, the teacher used a self-management strategy to teach the peers to monitor and record their use of the SPT strategies. Using the SPT visual the teacher asked the peer “did you stay with your partner?”, “did you play with your partner?” etc., and the peer would place a sticker in the box below for each step they followed. No additional reinforcement was used.

For Dyad 4, a modification was required for the peer, Max, to successfully withdraw teacher support. Specifically, a token economy typically used in the classroom was introduced to the play session and used for the duration of the intervention. When the peer successfully used SPT strategies with his partner independently, he received a star. If he received five stars during the session, the peer received two minutes of free choice time following the play session.

SPT without Teacher Support

SPT sessions without teacher support followed the same format as the previous condition but teacher support was withdrawn. Before the session, the teacher continued to use the SPT visual to remind the peer of the strategies. During the play session, the teacher or researcher did not prompt or support the peer or participant to use SPT strategies. At the end of the session, the peer self-monitored their strategy use, and the teacher gave the peer a sticker on their SPT visual in the same manner as the previous phase.

Generalization and Maintenance

Generalization probes were conducted across all conditions to assess whether behavior generalized to a novel setting, the playground, and followed the same procedures for the baseline and intervention conditions as described previously. However, the play menu was not used, and the play partners could choose to play with anything on the playground. Maintenance probes were conducted at three- and six weeks post-intervention and followed the same procedures as the SPT without teacher support condition.

Interobserver Agreement

To ensure the reliability of the data, a trained graduate student conducted interobserver agreement (IOA) for 30% of sessions in each condition across all dyads. The primary and secondary observers established 90% agreement on independently coded videos before collecting IOA data for this study. While conducting IOA, the graduate student was naïve to the condition they were observing. IOA was calculated for play type dependent variables using a point-by-point agreement for interval-based recording systems approach (Ledford & Gast, 2018). IOA for initiations was calculated using a percentage agreement approach (Ledford & Gast, 2018). Following one session in which IOA dropped below 80%, the secondary observer was retrained. Results for IOA across all dyads are found in Table 3.

Fidelity

Fidelity was assessed at multiple points during the teacher and peer trainings and during the implementation of the intervention. A co-author rated the fidelity of the implementation of the teacher training session by the first author by observing the entirety of the training session and rating against a predetermined checklist. Procedural fidelity was 100% for the teaching training session. The first author observed 100% of peer training sessions and rated the fidelity of implementation of the teacher against a predetermined checklist of the steps of training (i.e., introducing the strategy, providing examples, modeling the strategies, providing time for roleplay and practice until fidelity was reached). Procedural fidelity was determined by dividing the checklist items scored as correct by the total number of checklist items and multiplying by 100%. Procedural fidelity was 100% for all peer training sessions. In addition, the first author observed 100% of data collection sessions and rated the fidelity of implementation of the intervention protocol of the teacher at the end of data collection sessions against a predetermined checklist of steps depending on the phase (i.e. during the teacher-supported SPT phase, the teacher reminded peers of the strategy using the SPT visual, if no interaction occurred for 30 s the teacher prompted the peer using the least to most prompt hierarchy, etc.) The procedural fidelity of the teacher was calculated at 100% for all sessions.

Social Validity

Social validity was considered in the development of the intervention and in the assessment of its procedures and outcomes. Before the study, the researcher met with the teacher to discuss the children’s goals and collaborated to ensure the procedures of intervention were feasibly designed to work with the schedule of the classroom without interrupting routines. Social validity was also measured after the study. The teacher provided feedback on the feasibility of the treatment package using a researcher-made survey. In addition, the teacher used the Teacher Impression Scale ([TIS], McConnell & Odom, 1999) to rate the social play behaviors of the children by viewing two-minute video clips for dyads 2, 3, and 4 (i.e., for those whose caregivers provided consent to view videos for social validity purposes). The video clips contained (a) a segment of the dyad during baseline and (b) a segment of the dyad during a SPT without teacher support session. The videos were viewed in a randomized order. Using a five-point Likert scale, the teacher rated the degree to which the statement described the child’s behavior in the video. If the behavior or particular skill did not occur in the video the teacher was instructed to circle 1, indicating the behavior never occurred. If the child frequently performed the described skill or behavior, the teacher was instructed to circle 5, indicating the behavior occurred frequently. If the child performed the behavior in between these two extremes, the teacher was instructed to circle 2, 3, or 4 indicating their best estimate of the rate of occurrence of the skill or behavior. Mean and standard deviation were calculated for each item across all participants.

Analysis

We used visual analysis to evaluate the trend, variability, and consistency of the data pattern between phases. Visual analysis is the most commonly used data analysis method in SCED research and allows the researcher to continuously evaluate the effectiveness of intervention and demonstrate experimental control (Ledford & Gast, 2018). To statistically analyze effects, we also calculated effect sizes using standardized mean difference (SMD), a parametric measure appropriate for SCED research (Barnard-Brak et al., 2021; Pustejovsky, 2018). To calculate SMD effect sizes we used a web-based tool (Pustejovsky et al., 2023).

Results

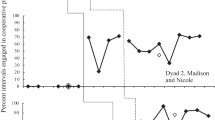

Figure 1 displays the percentage of intervals the dyads engaged in interactive play during baseline, teacher-supported SPT, and independent SPT sessions. Improvements in interactive play and initiations from baseline to intervention were demonstrated in all four dyads, and visual analysis indicated a functional relation between the intervention and interactive play. Interactive play during generalization probes showed a more modest increase across all dyads.

Dyad 1: Carson & Parker

During baseline, low levels of interactive play with a decreasing trend were observed for Carson and Parker (M = 9%, range 4–17%). Following peer training, interactive play immediately increased. Over the six teacher-supported sessions, interactive play continued to increase well above baseline levels (M = 52%, range 29–69%). After teacher support was removed, observations of interactive play remained at high and relatively stable levels (M = 81%, range 54–100%). SMD equaled 2.78. Increases in interactive play were also observed during generalization probes. During baseline, interactive play was measured at 4% of play sessions. Following peer training, increases were observed (M = 50%, range 44–69%).

Dyad 2: Owen and Jack

During baseline, low levels of interactive play with a decreasing trend were observed from the first to the second session for Owen and Jack, and then relatively stable low levels remained throughout baseline (M = 7%, range 0–25%). Following training, interactive play immediately increased (M = 75%, range 48–98%). Dyad 2 reached the criterion for teacher support to be removed after five sessions. After support was removed, interactive play remained high and relatively stable throughout intervention (M = 86%, range 63–96%). SMD equaled 5.62. Increases in interactive play were also observed during generalization probes as a result of intervention. During baseline, interactive play was not observed on the playground. Following peer training, increases were observed (M = 71%, range 51–85%).

Dyad 3: Noah and Elliot

During baseline, low levels of interactive play were observed for Noah and Elliot engaged (M = 6%, range 0–22%). After the teacher implemented peer training with Elliot, observations of interactive play increased from 8% in session 9 to 64% in session 10. Data collection for this intervention took place while COVID-19 isolation protocols were in effect at the school. Per the school’s policy, students were required to stay home for 10 days following a known exposure to COVID-19. Due to this protocol, the participant and peer from Dyad 3 missed a total of three weeks of data collection while in the teacher-supported SPT phase of intervention. When the peer returned to school and returned to the teacher-supported SPT phase, data indicated that he did not require additional training, and teacher support was withdrawn after two data collection sessions. Throughout the teacher-supported phase of intervention, observations of interactive play continued well above baseline levels until the dyad reached the criterion for teacher support to be withdrawn (M = 67%, range 45–92%). After teacher support was removed, increases in interactive play continued (M = 81%, range 54–96%). At maintenance probes levels of interactive play observed remained above baseline levels (M = 64%, range 63–65%). SMD equaled 4.89. Increases in interactive play were also observed during generalization probes. During baseline, observations of interactive play on the playground averaged 16% of the play session (range 4–28%). Following peer training, increases were observed (M = 68%, range 58–81%).

Dyad 4: Sara and Max

During baseline, interactive play was not observed for Sara and Max (M = 0%). Following peer training, interactive play immediately increased during the first session and continued to increase through the fifth teacher-supported session. During the sixth and seventh teacher-supported sessions, decreases were observed in engagement in interactive play between the dyad. When the token economy system was implemented for the peer, interactive play increased and the criterion to withdraw teacher support was met (M = 57%, range 21–85%). After teacher support was withdrawn, the token economy remained, and interactive play remained at levels above baseline with some variability (M = 59%, range 34–71%). At maintenance sessions, relatively, high stable levels of interactive play were observed (M = 70%, range 69–71%). SMD equaled 3.53. Small increases in interactive play were also observed during generalization probes following peer training. During baseline, the dyad did not engage in interactive play on the playground. Following peer training, small increases were observed (M = 25%, range 17–35%).

Solitary and Parallel Play

Figure 2 displays the percentage of intervals the dyads engaged in solitary and parallel play across study conditions. Overall, solitary play decreased across all dyads as engagement in interactive play increased.

Percent intervals engaged in solitary and parallel play. Solitary Play is shown by the solid black line and circle markers. Parallel play is shown by the dotted line and square markers. Open markers represent generalization probes. Tick mark on x-axis of dyad 3 indicates 3-week gap in data collection. The down arrow displayed in Dyad 4 indicates the introduction of the peer’s token economy

Dyad 1: Carson & Parker

During baseline, solitary and parallel play were observed in the majority of sessions. A decreasing trend in solitary play was observed during baseline (M = 50%, range 38–71%). Following peer training, solitary play immediately decreased to 10% in session 4. During the teacher-supported phase, decreases in solitary play remained (M = 7%, range 0–13%). After teacher support was removed, engagement in solitary play remained low and relatively stable (M = 2%, range 0–8%). During baseline for Carson and Parker, observations of parallel play increased (M = 42%, range 15–58%). During this time, Carson would often engage in onlooker play where he would pay close attention to what Parker was playing with, but he would not join in play or play cooperatively with his partner. Following peer training, a slight increase was observed from session 3 to session 4 (from 58 to 61%) and then a relatively stable decreases in parallel play were observed throughout the teacher-supported phase as engagement in more interactive play increased (M = 41%, range 30–61%). After teacher support was withdrawn, parallel play continued to decrease (M = 17%, range 0–44%).

Dyad 2: Owen and Jack

During baseline, high levels of solitary play and parallel play were observed during Owen and Jack’s play sessions. Engagement in solitary play increased from session 2 to session 3, and then a decreasing trend (M = 26%, range 8–52%) was observed. Following peer training, solitary play remained at zero during the teacher-supported SPT phase of intervention. After support is removed, observations of solitary play remained low for the remainder of intervention (M = 1%, range 0–4%). The play partners engaged in high levels of parallel play during baseline (M = 67%, range 42–90%). After the intervention was implemented, observations of parallel play showed a decreasing trend through the teacher-supported phase (M = 25%, range 2–52%). Following the removal of teacher support, parallel play remained well below baseline levels throughout the remainder of the intervention (M = 13%, 4–37% range).

Dyad 3: Noah and Elliot

During baseline, solitary play was observed for the majority of the sessions (M = 69%, range 32–90%). Following peer training, solitary play immediately decreased and remained relatively stable across the teacher-supported sessions (M = 10%, range 0–17%). After teacher support was withdrawn, levels of solitary play remained well below baseline levels and relatively stable for the remainder of the intervention (M = 8%, range 0–21%). At maintenance probes measured at three- and six-weeks post-intervention, engagement in solitary play remained at low levels demonstrating maintenance of targeted skills (M = 14%, range 6–21%). Noah and Eliot engaged in parallel play 25% of the session during baseline (range 10–46%). During the teacher-supported sessions, parallel play remained at levels similar to baseline until the fourth teacher-supported session where parallel play decreased as interactive play increased (M = 23%, range 6–38%). Following the removal of teacher support, engagement in parallel play remained below baseline levels (M = 16%, range 4–29%).

Dyad 4: Sara and Max

High levels of solitary play were observed during the baseline phase (M = 98%, range 92–100%). Following peer training, solitary play immediately lowered to 54% of the session. Through the first eight teacher-supported sessions, solitary play remained lower than baseline, yet displayed high variability. After the peer reinforcement system was implemented, observations of solitary play continued at levels well below baseline with less variability between sessions for the remainder of the intervention. Teacher support was withdrawn and solitary play remained low (M = 15%, range 0–38%). At maintenance probes measured at three- and six-weeks post-intervention, observations of solitary play remained below baseline (M = 1%, range 0–2%). Dyad 4 engaged in low levels of parallel play during baseline (M = 2%, range 2–8%). Engagement in parallel play increased following peer training, suggesting Sara began to show an interest in the play materials and the play activities of her partner. Parallel play remained above baseline levels throughout the teacher-supported sessions (M = 18%, range 6–31%) and after teacher support was withdrawn (M = 25%, range 15–33%).

Peer and Participant Initiations

The frequency of peer and participant initiations can be found in Fig. 3. Visual analysis indicated a functional relation between the intervention and peer/participant responses. In addition, SMD indicated large to very large effects across all dyads. Participant initiations in generalization sessions for dyads 1, 3, and 4 showed similar increases in intervention compared to baseline. Increases in peer initiations during generalization probes were also observed across all dyads in the intervention phase.

Participant and peer initiations. Participant initiations are shown by the solid black line. Peer initiations are shown by the dotted line. Open characters indicate generalization probes. Tick mark on x-axis of dyad 3 indicates 3-week gap in data collection. The down arrow displayed in Dyad 4 indicates the introduction of the peer’s token economy

Dyad 1: Carson & Parker

During baseline, Parker initiated to Carson an average of 5 times per session (range 4–6), and Carson initiated to Parker an average of 7 times per session (range 4–10). In the teacher-supported sessions, peer initiations increased (M = 11, range 5–18) and continued to increase after teacher support was withdrawn (M = 17, range 4–30). In turn, a similar increase was observed in participant initiations between Carson and Parker during the teacher-supported sessions (M = 10, range 0–19), and after teacher support was withdrawn, initiations continued to increase (M = 20, range 12–35). SMD equaled 1. 17 for participant initiations and 1. 24 for peer initiations. Similar increases were observed in generalization probes. During baseline, Parker initiated to Carson 4 times on the playground, and following SPT training, initiations increased to an average of 10 times per playground session (range 6–13). Mirroring a similar trend, Carson initiated play to Parker four times during the baseline generalization session. And following peer training, Carson also initiated to Parker an average of 10 times per session (range 7–15).

Dyad 2: Owen and Jack

During baseline, Jack initiated to Owen an average of 9 times per session (range 3–15). Owen initiated to Jack an average of 13 times per session (range 3–21). Initiations were not reciprocal, and often Owen initiated to Jack and Jack did not respond. Following peer training, initiations from Jack increased to an average of 19 times during the teacher-supported sessions (range 8–26), and in turn, Owen’s initiations continued to increase to an average of 26 initiations (range 11–42) during the teacher-supported sessions, with initiations becoming more matched in frequency between the dyad. After support was withdrawn, participant and peer initiations were maintained for an average of 18 initiations per session from Jack (range 13–22) and 20 initiations per session from Owen (range 10–32). SMD equaled 0. 99 for participant initiations and 1. 81 for peer initiations. Large increases in initiations between baseline and intervention were not observed during generalization probes. During baseline, Jack initiated to Owen 13 times and Owen initiated to Jack 9 times. Following peer training, Jack averaged 12 initiations to Owen (range 11–12), and Owen averaged 14 initiations to Jack (range 11–16).

Dyad 3: Noah and Elliot

During baseline, a decreasing trend of peer initiations was observed, and Elliot initiated to Noah an average of 5 times (range 2–11) per session. A similar decreasing trend was observed in Noah’s initiations toward Elliot during baseline with an average of 5 initiations occurring per play session (range 1–14). Following peer training, an immediate increase in Elliot’s initiations was observed, and during the teacher-supported sessions, he averaged 21 initiations per session (range 19–24). After support was withdrawn, increases in peer initiations were maintained (M = 17, range 10–22). In response, similar increases were observed in participant initiations. During teacher-supported sessions, Noah initiated to Elliot an average of 17 times (range 9–25) per play session, and after teacher support was withdrawn, Noah continued to initiate to Elliot at an increased frequency (M = 14, range 6–19). SMD equaled 1.96 for participant initiations and 3.59 for peer initiations. A similar trend was observed in generalization sessions from baseline to intervention. During baseline, Elliot initiated play toward Owen an average of 5 times (range 3–6) per session, and Owen initiated toward Elliot an average of 7 times (range 6–7) per session. Following peer training, peer initiations increased (M = 18, range 13–20) and participant (M = 15, range 12–19) initiations increased.

Dyad 4: Sara and Max

During baseline, Max initiated to Sara an average of 0. 5 times per session (range 0–2), and Sara initiated to Max one time in all of baseline sessions. Following peer training, peer initiations immediately increased (M = 16, range 8–25) and remained at elevated levels throughout the remainder of intervention (M = 16, range 7–28). Sara’s initiations also increased during the teacher-supported sessions (M = 6, range 2–14), and frequency of initiations remained above baseline levels after teacher support was withdrawn (M = 8, range 3–15). SMD equaled 1.94 for participant initiations and 3.10 for peer initiations. During baseline generalization probes, Max initiated to Sara an average of 2 times, and Sara did not initiate play toward Max. Following peer training, increases in initiations were observed in peer initiations (M = 14, range 12–21) and participant initiations (M = 3, range 1–5).

Social Validity Findings

The teacher provided feedback on the feasibility of intervention using a 5-point Likert scale and responding to open-ended questions. She strongly agreed that the SPT intervention targeted a socially important behavior or skill for students with autism, was easily implemented in a classroom setting, was time and cost-effective, was beneficial to both the participants and peers, and was enjoyed by the students participating in the intervention. She also strongly agreed that the training improved her ability to implement SPT in her classroom, that the training procedures were feasible to teach peers SPT strategies, and that she felt confident using SPT strategies in her classroom post-intervention. She reported role-playing to be the most beneficial aspect of the training the researcher provided to the teacher. She also reported that the visual aids with the child-specific pictures helped the students understand each step of the protocol.

Table 4 displays the results of the TIS (McConnell & Odom, 1999). For each dyad, the teacher rated two videos from baseline and two videos from intervention. For each dyad, the teacher recorded increases from baseline (M = 1.65, range 1.2–2.23) to intervention (M = 3.28, range 2.2–4.23) of the occurrence of play behaviors described on the TIS. For three of the four dyads, the teacher rated two videos from baseline and two videos from intervention.

Discussion

The results from this intervention further support the use of SPT to improve play and social interactions between young children with and without autism and demonstrates that a teacher can successfully train and support peers to implement this PMI in an inclusive preschool setting. These results provide additional support that BST is effective in training natural intervention agents to implement evidence-based practices with children with autism. Increases in interactive play and decreases in solitary play were observed across all dyads post-training, and these results maintained after the teacher withdrew direct support during the play session.

One aim of this study was to measure and assess the type of play in which the dyads engaged. This allowed for a nuanced analysis of play behaviors during baseline without adult support or facilitation, during intervention with teacher support, and after teacher support was withdrawn. During baseline, participants mostly engaged in solitary or parallel play near their partner. For example, children sat next to each other and each built their own tower out of blocks. The participants in this study had received therapies that often included peers in sessions, yet we observed that interactive play was low or absent without other supports in place across all dyads during baseline. This highlights the importance of not only involving peers in interventions but also directly teaching strategies to better interact in play and be responsive to classmates with autism (Fedewa et al., 2022). After training, peers learned strategies to initiate play with their partner and the play interactions became more cooperative. It should be noted that the goal of this intervention was not engagement in interactive play for the entirety of the play sessions. Solitary and parallel play are important for emotional regulation, especially for neurodiverse children. This intervention was child rather than adult-led and designed to allow children with autism to interact with the environment in a way that aligns with their individual preferences and interests (Schuck et al., 2021). Therefore, the researchers and teachers did not direct play activities and play partners were free to choose and interact with materials however they felt was appropriate.

Although increases in interactive play were observed across dyads, modest, yet clinically significant, increases were observed in Dyad 4. However, specific to this dyad, increases in parallel play were also observed. During baseline, Dyad 4 were observed engaging in solitary play and minimal parallel play, which aligns with previous theories suggesting play skills develop in a hierarchal way (Parten, 1932). Sara was the youngest participant and had the least developed spoken language. Following peer training, Sara was observed engaging in more “onlooker play,” often mimicking what her partner was doing (e.g., building the same structure out of blocks next to her partner). Parallel play represents an immediate step or bridge between solitary play and engaging in more social play behaviors (Luckey & Fabes, 2005). The results from Dyad 4 support this interpretation, further suggesting that parallel play is an important measure of play development and may be an important foundational skill for children with autism to engage in before targeting more cooperative forms of play.

As found in previous SPT studies, increases in peer initiations were also observed following peer training, which maintained when teacher support was withdrawn. Notably, increases in participant initiations were also observed. This is important, as participant initiations were not directly targeted in intervention, and evoking initiations from children with autism are more difficult than responses to peer prompts (Pierce & Schreibman, 1997). This aligns with previous literature suggesting targeting increases in peer initiations can increase initiations in participants with autism, potentially resulting in more balanced and reciprocal interactions (Watkins et al., 2023). In this intervention, the majority of participants had well-developed language abilities similar to their TD partners. Yet, during the baseline phase, the participants and peers showed low levels of initiations, and verbal interactions were not reciprocal, confirming the need for direct teaching of strategies.

Some variability was observed for the participants’ and peers’ initiations across all dyads. As this intervention was child-led, the peer and participant selected the toys used in each session from a play menu before the data collection sessions. However, some toys were potentially more conducive to interactive play and initiations than others. For example, completing a puzzle together allowed for clearer turn-taking behaviors and interactions compared to playing with action figures or dinosaurs where the play activity was not as clearly structured and cooperative. Although the same materials were offered as choices in baseline and intervention, the materials chosen by each dyad could potentially affect the behaviors observed. During peer training, the teacher taught the peer to select and encourage their partner to choose play materials from the choice menu which encouraged cooperation. When practitioners target interactive play in a classroom environment, it may be important to select materials that are preferred and motivating to the students and designed to be more interactive (Fedewa et al., 2023).

The results of this intervention contribute to the growing body of SPT literature showing that young children can be trained in SPT and implement it with their classmates with autism (Ledford & Pustejovsky, 2023). In addition, adult support and prompting were removed and the peer partners continued the use of the strategies and gains in interactive play and initiations were maintained. The teacher used a BST approach to train the peers to use the intervention strategies with their partner. One step in our peer training procedures was to increase the peer’s understanding of the unique play, social interaction, and behavioral characteristics of their play partner. For example, Noah exhibited some behaviors in baseline that interrupted play sessions and needed direct teaching for his partner to better support play interactions. Noah often engaged in perseverative and self-stimulatory behaviors by holding one block or magnet to his face for an extended amount of time. During peer training, the teacher taught Elliot to say Noah’s name, tap lightly on his shoulder, and initiate play by offering Noah a choice of play materials. After Elliot learned these strategies and was provided with the necessary tools to gain Noah’s attention, the play became more coordinated and Elliot interacted and initiated to his partner regularly. As classmates are often interested in engaging with classmates with autism but may find it challenging to interpret their verbal and non-verbal behaviors (Sasson et al., 2017), directly teaching Elliot to initiate play while Noah was engaging in self-stimulatory behaviors further increased Noah’s interactions and engagement in play activities. In addition, as play is naturally reinforcing, the peers likely were able to maintain the use of strategies after more direct teacher support and reinforcement was withdrawn. To successfully fade teacher prompts, Max in Dyad 4 did need additional reinforcement and during the teacher-supported phase, we incorporated a teacher-delivered token economy system. Following a similar procedure from a previous SPT study (i.e., Serverini et al., 2019), the introduction of the token economy led to an increase in Max’s independent use of SPT procedures and teacher prompts were successfully withdrawn.

Finally, in assessing the social validity results, the teacher reported the intervention was easily implemented within the daily classroom routine, and the intervention training improved her ability to facilitate SPT and PMIs. We trained the teacher in one 30-min session, and the teacher proceeded to train the peers to implement the intervention with fidelity. Teachers have reported a main barrier to implementing evidence-based practices in inclusive settings is a lack of training and resources (Knight et al., 2019). The teacher also reported benefits from the intervention for the peers and the participants with autism. The peers who participated in the intervention made significant social gains and were observed using SPT strategies to engage in play with all students in the classroom and free-play class times became more interactive. This observation adds to the literature supporting the mutual benefits of PMIs to participants as well as peers in inclusive settings (Travers & Carter, 2022).

Limitations and Future Research

Although we did not directly measure symbolic play behaviors in this study, we anecdotally observed Dyad 1 and Dyad 2 begin to engage in symbolic play as the intervention progressed. For example, the partners would enact different character roles with trains and pretend to run away from a monster on the track. As previous SPT interventions have also reported the potential intervention influences on the development of pretend play behaviors (e.g., Barber et al., 2016), these anecdotal observations warrant future research. As data were collected during free-play time for all students, the classroom could be loud, and the noise was sometimes distracting for participants, which could have potentially influenced responding. Although this study aimed to conduct the intervention in the usual classroom context, minimizing distractions may be necessary for some children. In addition, no adverse events, challenging behaviors, or resistance towards participation in the play sessions occurred from the participants or peers. As this intervention was child-led and the dyad was allowed to engage with play materials of their choice and in a way that met their preferences, potential adverse events were minimized. Yet, learning when peers with autism do not want to engage in play activities with classmates is equally important, therefore including this in training protocols is important in applied settings or future research.

Data collection also occurred while COVID-19 exposure isolation protocols were enforced, and this resulted in a gap in data collection for Dyad 3 during the teacher-supported phase due to a mandatory quarantine period. Scheduling difficulties also affected our generalization probes and resulted in inconsistencies in data collection. Although the teacher did anecdotally report the peers’ use of SPT strategies outside of intervention sessions, future research more closely examining generalization effects on play behaviors in different settings is warranted. Similarly, only two dyads were available for maintenance probes, so further information is needed to examine the durability of the effects. In addition, due to scheduling issues, we did not collect social validity feedback from the participants post-intervention. Finally, the participants included in this intervention had well-developed language, had received extensive therapies, and were from families with higher socioeconomic backgrounds. In addition, the teacher who served as the interventionist had extensive training in behavior analytic principles, had previous knowledge of BST protocols and was currently enrolled in coursework to complete BCBA certification, and possibly required less direct training from the researcher due to previous training and knowledge. Although this intervention has shown to be effective in less well-resourced settings (see Watkins et al., 2023), future research of SPT interventions that include participants from more diverse backgrounds and characteristics of autism in a setting with fewer resources available (e.g., time, therapies, staff support), is warranted. In addition, the teacher trained each peer individually to fidelity in one 40-min training session, which may have limited feasibility in some settings. Therefore, further research of SPT training in groups in applied settings seems warranted.

Despite these limitations, the findings of this study add to the robust body of research supporting the use of PMI to improve social interaction in inclusive early childhood settings and extends the literature by demonstrating that teachers can successfully train peers to implement strategies with fidelity. Importantly, this study extends the SPT literature by examining not only social initiations but also the type of play the participants and peers engaged in, with results suggesting that this strategy can produce changes in interactive play between children with and without autism.

References

Barber, A. B., Saffo, R. W., Gilpin, A. T., Craft, L. D., & Goldstein, H. (2016). Peers as clinicians: Examining the impact of Stay Play Talk on social communication in young preschoolers with autism. Journal of Communication Disorders, 59, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjcomdis.2015.06.009

Barnard-Brak, L., Watkins, L., & Richman, D. M. (2021). Autocorrelation and estimates of treatment effect size for single-case experimental design data. Behavioral Interventions, 36(3), 595–605. https://doi.org/10.1002/bin.1783

Bowman-Perrott, L., Gilson, C., Boon, R. T., & Ingles, K. E. (2023). Peer-mediated interventions for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A systematic review of reviews of social and behavioral outcomes. Developmental Neurorehabilitation,. https://doi.org/10.1080/17518423.2023.2169878

Brock, M. E., Cannella-Malone, H. I., Seaman, R. L., Andzik, N. R., Schaefer, J. M., Page, E. J., Barczak, M. A., & Dueker, S. A. (2017). Findings across practitioner training studies in special education: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Exceptional Children, 84(1), 7–26.

Carr, E. G., & Darcy, M. (1990). Setting generality of peer modeling in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 20(1), 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02206856

Charlop, M. H., Lang, R., & Rispoli, M. (2018). Play and social skills for children with autism spectrum disorder (pp. 71–94). New York: Springer International Publishing.

Fedewa, M., Watkins, L., Barnard-Brak, L., & Akemoglu, Y. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of single case experimental design play interventions for children with autism and their peers. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-022-00343-5

Fedewa, M., Watkins, L., Barber, A., & Baggett, J. (2023). Supporting social play of preschoolers with and without Autism: A collaborative approach for special Educators and speech language pathologists. Early Childhood Education Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-023-01488-6

Ganz, J. B., & Flores, M. M. (2008). Effects of the use of visual strategies in play groups for children with autism spectrum disorders and their peers. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(5), 926–940. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0463-4

Goldstein, H., Schneider, N., & Thiemann, K. (2007). Peer-mediated social communication intervention: When clinical expertise informs treatment development and evaluation. Topics in Language Disorders, 27(2), 182–199. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.TLD.0000269932.26504.a8

Guldberg, K. (2017). Evidence-based practice in autism educational research: can we bridge the research and practice gap. Oxford Review of Education, 43(2), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2016.1248818

Hemmeter, M. L. (2000). Classroom-based interventions evaluating the past and looking toward the future. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 20(1), 56–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/027112140002000110

Howes, C., & Matheson, C. C. (1992). Sequences in the development of competent play with peers: Social and social pretend play. Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 961. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.28.5.961

Jung, S., & Sainato, D. M. (2015). Teaching games to young children with autism spectrum disorder using special interests and video modelling. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 40(2), 198–212. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2015.1027674

Kennedy, C. H. (2005). Single-case designs for educational research. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Knight, V. F., Huber, H. B., Kuntz, E. M., Carter, E. W., & Juarez, A. P. (2019). Instructional practices, priorities, and preparedness for educating students with autism and intellectual disability. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 34(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357618755694

Leaf, J. B., Townley-Cochran, D., Taubman, M., Cihon, J. H., Oppenheim- Leaf, M. L., Kassardjian, A., & Pentz, T. G. (2015). The teaching interaction procedure and behavioral skills training for individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder: A review and commentary. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2(4), 402–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-015-0060-y

Ledford, J. R., Gast, D. L. (Eds.). (2018). Single case research methodology. Routledge.

Ledford, J. R., & Pustejovsky, J. E. (2023). Systematic review and meta-analysis of stay-play-talk interventions for improving social behaviors of young children. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 25(1), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300720983521

Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P., Risi, S., Gotham, K., & Bishop, S. (2012). Autism diagnostic observation schedule–2nd edition (ADOS-2). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Corporation. https://doi.org/10.1037/t17256-000

Luckey, A. J., & Fabes, R. A. (2005). Understanding nonsocial play in early childhood. Early Childhood Education Journal, 33, 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-006-0054-6

Milam, M. E. (2018). Stay-play-talk with preschoolers: Programming for generalization. Nashville: Vanderbilt University.

Morosohk, E., & Miltenberger, R. (2022). Using generalization-enhanced behavioral skills training to teach poison safety skills to children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52, 283–290.

Odom, S. L., & Strain, P. S. (1984). Peer-mediated approaches to promoting children’s social interaction: A review. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 54(4), 544. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.1984.tb01525.x

Parten, M. B. (1932). Social participation among pre-school children. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 27(3), 243–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0074524

Pustejovsky, J. E. (2018). Procedural sensitivities of effect sizes for single-case designs with behavioral outcome. PsychologicalMethods. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000179

Pustejovsky, J.E, Chen, M., Grekov, P., & Swan, D. M. (2023). Single-case effect size calculator (Version 0. 7. 1) https://jepusto.shinyapps.io/SCD-effect-sizes

Radley, K. C., O’Handley, R. D., & Labrot, Z. C. (2015). A comparison of momentary time sampling and partial-interval recording for assessment of effects of social skills training. Psychology in the Schools, 52(4), 363–378.

Raulston, T. J., Hansen, S. G., Frantz, R., Machalicek, W., & Bhana, N. (2020). A parent-implemented playdate intervention for young children with autism and their peers. Journal of Early Intervention, 42(4), 303–320.

Roane, H. S., Vollmer, T. R., Ringdahl, J. E., & Marcus, B. A. (1998). Evaluation of a brief stimulus preference assessment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 31(4), 605–620.

Sasson, N. J., Faso, D. J., Nugent, J., Lovell, S., Kennedy, D. P., & Grossman, R. B. (2017). Neurotypical peers are less willing to interact with those with autism based on thin slice judgments. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 40700–40700. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep40700

Schuck, R. K., Tagavi, D. M., Baiden, K. M., Dwyer, P., Williams, Z. J., Osuna, A., & Vernon, T. W. (2021). Neurodiversity and autism intervention: Reconciling perspectives through a naturalistic developmental behavioral intervention framework. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05316-x

Severini, K. E., Ledford, J. R., Barton, E. E., & Osborne, K. (2019). Implementing stay-play-talk with children who use AAC. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 38, 220–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121418776091

Sheikh, R., Patino, V., Cengher, M., Fiani, T., & Jones, E. A. (2019). Augmenting sibling support with parent-sibling training in familiesof children with autism. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 22(8), 542–552.

Sigman, M., Ruskin, E., Arbelle, S., Corona, R., Dissanayake, C., Espinosa, M., Kim, N., López, A., Zierhut, C., & Mervis, C. B. (1999). Continuity and change in the social competence of children with autism, down syndrome, and developmental delays. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 12, 1–139.

Slane, M., & Lieberman-Betz, R. G. (2021). Using behavioral skills training to teach implementation of behavioral interventions to teachers and other professionals: A systematic review. Behavioral Interventions, 36(4), 984–1002.

Steinbrenner, J. R., Hume, K., Odom, S. L., Morin, K. L., Nowell, S. W., Tomaszewski, B., Szendrey, S., McIntyre, N. S., Yücesoy-Özkan, S., & Savage, M. N. (2020). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism. Chapel Hill: FPG Child Development Institute.

Strain, P. S., & Kohler, F. (1998). Peer-mediated social intervention for young children with autism. In Seminars in Speech and Language (Vol. 19, No. 04, pp. 391–405). Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc. New York

Travers, H. E., & Carter, E. W. (2022). A portrait of peers within peer-mediated interventions: A literature review. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 37(2), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/10883576211073698

Vincent, L. B., Asmus, J. M., Lyons, G. L., Born, T., Leamon, M., DenBleyker, E., & McIntire, H. (2022). Evaluating the effectiveness of a reverse inclusion Social Skills intervention for children on the Autism Spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 5, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05513-2

Watkins, L., Ledbetter-Cho, K., O’reilly, M., Barnard-Brak, L., & Garcia-Grau, P. (2019a). Interventions for students with autism in inclusive settings: A best-evidence synthesis and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 145(5), 490. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000190

Watkins, L., Fedewa, M., Hu, X., & Ledbetter-Cho, K. (2023). A teacher-facilitated peer-mediated intervention to support interaction between students with and without autism. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 7(2), 252–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-022-00299-x

Watkins, L., O’Reilly, M., Kuhn, M., Gevarter, C., Lancioni, G. E., Sigafoos, J., & Lang, R. (2015). A review of peer-mediated social interaction interventions for students with autism in inclusive settings. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 1070–1083. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2264-x

Watkins, L., O’Reilly, M., Kuhn, M., & Ledbetter-Cho, K. (2019b). An interest-based intervention package to increase peer social interaction in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 52(1), 132–149. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.514

Wolfberg, P., Bottema-Beutel, K., & DeWitt, M. (2012). Including children with autism in social and imaginary play with typical peers: Integrated play groups model. American Journal of Play, 5(1), 55–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/e669652011-001

Young, K. R., Radley, K. C., Jenson, W. R., West, R. P., & Clare, S. K. (2016). Peer-facilitated discrete trial training for children with autism spectrum disorder. School Psychology Quarterly, 31(4), 507.

Funding

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Megan P. Fedewa: conceptualized and designed study, facilitated the implementation of study procedures, conducted data collection and analysis, wrote and revised the manuscript. Laci Watkins: conceptualized and designed study, supported the implementation of study procedures, analyzed data, wrote and revised the manuscript. Kameron Carden: conducted data collection and analysis, provided feedback on manuscript. Glenda Grbac: provided feedback on study aims, procedures, and outcomes; supported data collection.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All coauthors declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Fedewa, M.P., Watkins, L., Carden, K. et al. Effects of a Teacher-Facilitated Peer-Mediated Intervention on Social Play of Preschoolers with Autism. J Autism Dev Disord (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-024-06320-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-024-06320-7