Abstract

Although children of depressed mothers are at an increased risk for suicidal thinking, little is known about the potential mechanisms by which this occurs. The present study is the first to our knowledge to utilize a prospective design with the goal of examining whether the impact of maternal depression on children’s risk for suicidal ideation is mediated by children’s levels of overt and relational peer victimization. Participants were 203 mother-child pairs recruited from the community. The age range of the children was 8 to 14 years old (50.2 % girls). Mothers either met criteria for a major depressive disorder (MDD) during their child’s lifetime (n = 96) or had no lifetime diagnosis of any DSM-IV mood disorder and no current Axis I diagnosis (n = 107). At the baseline assessment, diagnostic interviews were used to assess mothers’ and children’s histories of MDD and children completed a self-report measure of peer victimization. Follow-up assessments were conducted at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months after the initial assessment during which time interviewers assessed for the occurrence of suicidal ideation in the children. Utilizing a mediated moderation model, we found significant indirect pathways from maternal depression to children’s suicidal ideation through both relational and overt forms of peer victimization among girls, but not among boys. The current study suggests that peer victimization may constitute one of the potential mechanisms by which daughters of depressed mothers are at increased risk for suicidal thinking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The transition to adolescence is associated with a marked increase in the rate of self-harming thoughts and behaviors (e.g., Kessler et al. 2005). Suicide is the third leading cause of death for 10–14 year olds and the second leading cause of death for 15–19 year olds (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2012). Further, according to the data available from Youth Risk Behavior Survey, between 11.6 % (Delaware) and 24.5 % (Wyoming) of 6th through 8th grade students across 18 states reported having ever seriously thought about killing themselves (CDC 2013). Consequently, suicidality constitutes a major public health concern among children and adolescents.

One of the strongest risk factors for internalizing problems in youth is a family history of depression, particularly maternal depression (for a meta-analytic review, see Goodman et al. 2011). However, less is known about the risk for suicide in this at-risk population. Specifically, although children of depressed, compared to nondepressed, mothers are more likely to have seriously considered suicide by adolescence (Klimes-Dougan et al. 1999) and experience more persistent suicidality (Klimes-Dougan et al. 2008), the mechanisms by which this occurs are poorly understood.

One potentially important factor is peer victimization. Indeed, studies have shown that children of mothers with a history of depression in their child’s life experience more severe chronic peer stress and more episodic interpersonal stress than do children of mothers with no history of depression (Adrian and Hammen 1993; Carter and Garber 2011; Feurer et al. 2015; Gershon et al. 2011; Hammen and Brennan 2001). Two commonly studied forms of peer victimization are overt and relational victimization. The former involves overt, physical behaviors, such as pushing, hitting, or kicking. The latter form of victimization involves causing harm by utilizing relationally aggressive strategies aimed at negatively impacting the victim’s relationships or social status. Examples include spreading rumors about the victim with the goal of causing rejection from the peers, social exclusion from activities, or withdrawing friendship or affection (Crick et al. 2002). There is strong evidence that peer victimization is related to suicidal thinking (for a meta-analytic review, see van Geel et al. 2014), although it comes predominately from the cross-sectional studies, which precludes any conclusions about causal relations between peer victimization and the emergence of suicidal thinking. With regard to prospective research, one study found that peer victimization predicted increases in suicidal ideation over a 10-month follow-up (Kim et al. 2009); however, two other longitudinal studies (Klomek et al. 2008, 2011) failed to find such an association. Finally, in the only study of which we are aware to separately examine the prospective impact of overt versus relational victimization on suicidal ideation, Heilbron and Prinstein (2010) found that overt victimization was associated with increasing trajectories of suicidal ideation in girls, but not in boys. With regard to relational victimization, the authors failed to find either cross-sectional or longitudinal associations between relational victimization and suicidal ideation in either sex. Taken together, these studies suggest that peer victimization is related to suicidality in children and adolescents, but the strength and magnitude of this relation vary depending on children’s sex and the type of peer victimization examined.

There is also evidence for sex differences in the impact of maternal depression on children, with girls of depressed mothers being at greater risk than boys. For example, a meta-analysis showed that maternal depression was more strongly associated with internalizing problems, including the symptoms of depression, anxiety, or social withdrawal, in girls than in boys (Goodman et al. 2011). Little is known, however, about the potential sex differences in emergence of suicidal thinking in children of depressed mothers.

The primary goal of the present study was to examine the impact of maternal depression on children’s risk for suicidal ideation using a prospective design and to determine whether children’s levels of overt or relational peer victimization mediate this relation. We hypothesized that mothers’ histories of major depressive disorder (MDD) would predict time to emergence of suicidal ideation in children over the course of a 2-year follow-up. We further predicted that reports of overt and relational peer victimization would mediate the link between maternal history of MDD and children’s thoughts of suicide. A secondary aim was to examine the potential moderating role of children’s sex in these relations. Given the dearth of relevant longitudinal research, lack of consensus in the literature with regard to the relations between each of the forms of peer victimization and suicidal thinking in children, and lack of agreement about whether these relations and the relation between maternal MDD and the emergence of suicidal thinking in children are moderated by children’s sex, we made no specific hypotheses for these analyses.

Method

Participants

Participants were 203 mother-child pairs recruited from the community. To qualify for the study, mothers were required to either meet criteria for MDD during the child’s lifetime (n = 96), according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association 2000), or have no lifetime diagnosis of any DSM-IV mood disorder and no current Axis I diagnosis (n = 107). Of the women with a lifetime history of MDD, 14 met criteria for current MDD at the baseline assessment. Exclusion criteria for both groups included symptoms of schizophrenia, organic mental disorder, alcohol or substance dependence within the last 6 months, or history of bipolar disorder. In addition, all children were between the ages of 8 and 14 at the baseline assessment and only one child per family could participate. If more than one child per family in this age range was available for participation, one child was chosen at random. The average age of the mothers at baseline in the present study was 40.66 years (SD = 6.80, Range = 24–55; 90.1 % Caucasian). The average age of the children at baseline in the present study was 11 years (SD = 1.89, Range = 8–14; 50.2 % girls; 85.2 % Caucasian). In our sample, 11 (5.4 %) reported a history of MDD, 22 (10.8 %) of children reported a history of an anxiety disorder, and 22 (10.8 %) reported a history of a behavioral disorder (i.e., ADHD, ODD, conduct disorder). The median annual family income was $50,001 to 55,000. See Table 1 for more details.

Measures

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I; First et al. 1995) and the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children – Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman et al. 1997) were used to assess for current DSM-IV Axis I disorders in mothers and their children, respectively. The interviews were administered by two trained interviewers (i.e., one interviewer administered SCID-I and the other interviewer administered K-SADS-PL). For the K-SADS-PL, mothers and children were interviewed separately. Interrater reliability was assessed by coding a subset of 20 SCID and K-SADS interviews by a second interviewer. Kappa coefficients for the diagnoses of MDD and anxiety disorders were excellent (k = 1.00). The SCID-I and K-SADS-L were administered at the baseline assessment and the K-SADS-L was administered again at each follow-up assessment.

As part of the K-SADS-PL interviews at each assessment, interviewers assessed for the presence of suicidal ideation in children. More specifically, suicidal ideation was assessed by asking the questions “Sometimes children who get upset or feel bad, wish they were dead or feel they’d be better off dead. Have you ever had these types of thoughts?” and “Sometimes children who get upset or feel bad think about dying or even killing themselves. Do you have these thoughts?” The initial assessment focused on children’s lifetime history of suicidal ideation and each follow-up assessment focused on any thoughts that had occurred since the previous interview. The current study focused only on children who did not report any current thoughts of suicide at the baseline assessment, though 17 did report a past history of these thoughts (11 of whom were children of depressed mothers). A total of 26 children (50 % girls) reported the emergence of suicidal thinking during the follow-up period.

Children’s experiences of peer victimization were assessed via the Social Experiences Questionnaire-Self-Report (SEQ-SR; Crick and Grotpeter 1996) administered at the baseline assessment. The SEQ-SR includes two five-item victimization subscales: overt (e.g., “How often do you get hit by another kid?”) and relational (e.g., “How often do other kids leave you out on purpose when it is time to play or do an activity?”). The children were asked to indicate the frequency of being victimized by their peers by responding to these questions on a 5-point Likert-type scale, with a score of 1 corresponding to never and a score of 5 corresponding to all the time. In the current sample, internal consistency was α = .82 for the overt victimization subscale and α = .82 for the relational victimization subscale.

Procedure

Potential participants were recruited from the community through a variety of means (e.g., television, newspaper and bus ads, flyers). Participants responding to the recruitment advertisements were initially screened over the phone to determine potential eligibility. Upon arrival at the laboratory, participants were asked to provide informed consent. Next, the child completed questionnaires including the SEQ-SR and the mother was administered the K-SADS-PL by a trained interviewer. After completing the K-SADS-PL with the mother, the same interviewer then administered the K-SADS-PL to the child. While the child was administered the K-SADS-PL, the mother was administered the SCID-I by a separate interviewer. Following this baseline assessment, participants completed follow-up appointments, which occurred 6, 12, 18, and 24 months after the initial assessment. At each of these assessments, a trained interviewer assessed for the presence of suicidal ideation in the children during the previous 6 months. SCID-I and SEQ-SR were administered at baseline assessment and K-SADS-PL were administered at baseline and each of the follow-up assessments. Each family was compensated with $75 at baseline assessment and with $50 at each of the follow-up assessments for their participation. After the baseline assessment, the mother-child dyads were invited to come back to the lab for 6, 12, 18, and 24 months follow-up assessments. Each assessment took about 3 h to complete. All study procedures were approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board.

Analytic Plan

Our hypotheses in this study were that children of depressed mothers would be at elevated risk for suicidal ideation during the course of the study and that this relation would be mediated by experiences of peer victimization. That is, we predicted that one mechanism by which children of depressed mothers are at increased risk for suicidal ideation is because they experience higher levels of peer victimization than other children. We were also interested in examining the potential moderating role of children’s sex in these relations. We used a multi-step approach to test these hypotheses. First, we used Cox proportional hazard regression analysis to determine whether mothers’ histories of MDD would predict time to emergence of suicidal ideation in children over the course of a 2-year follow-up and whether this effect would be moderated by children’s sex. Second, we utilized two separate 2 (mother MDD history: yes, no) x 2 (child sex: girl, boy) ANOVAs to examine the links between mother MDD and both overt and relational peer victimization in children and to evaluate the potential moderating role of child sex. Third, we used Cox proportional hazard regression analyses to determine whether levels of overt and relational victimization assessed at the baseline assessment predicted time to onset of suicidal thinking in children during the follow up. Fourth, we tested the full mediated moderation model using model 8 in the SPSS macro PROCESS (Hayes 2013). Finally, to test the robustness of our findings and determine whether the effects are at least partially independent of children’s own history of MDD, we examined whether the results would be maintained even if children with a lifetime history of MDD at baseline were excluded from the analyses. As an additional test of robustness, we also re-conducted the analyses excluding dyads in which the mother met criteria for current MDD at the baseline assessment.

Results

A preliminary inspection of the data revealed that the two victimization variables exhibited significant positive skew (p < .001). Therefore, these variables were transformed (inverse) prior to further analysis to satisfy assumptions of normality, which resulted in nonsignificant skew (p > .05). The two peer victimization variables were significantly correlated (r = .72, p < .01).

Next, as a first step in evaluating our proposed mediational model, we used a Cox proportional hazard regression analysis to examine the impact of maternal depression on time to occurrence of children’s suicidal ideation during the follow-up. The between subjects factors in this analysis were mother MDD history (yes, no) and child sex (girl, boy). We found that although there were no significant main effects of mother MDD, Wald = 0.06, p = .82, OR = 0.91, there was a significant main effect of child sex, Wald = 3.94, p = .05, OR = 0.34, and a significant mother MDD × child sex interaction, Wald = 7.18, p < .01, OR = 5.99. To examine the form of this interaction, we examined the effect of mother MDD separately in girls and boys. We found that mother’s history of MDD significantly predicted time to suicidal ideation in girls, Wald = 10.28, p < .01, OR = 5.18, but not in boys, Wald = 0.08, p = .78, OR = .89. The survival curve for girls is shown in Fig. 1.

Next, we examined the links between mother MDD and both overt and relational peer victimization. In these analyses, we also tested for the potential moderating role of child sex. Focusing first on the link between mother MDD and levels of children’s overt victimization, we conducted a 2 (mother MDD: yes, no) × 2 (sex: boy, girl) ANOVA separately for each form of peer victimization. For overt victimization, although the main effects of mother MDD, F(1, 199) = 1.04, p = .31, and child sex, F(1, 199) = 2.27, p = .13, were not significant, there was a significant mother MDD × child sex interaction, F(1, 199) = 3.79, p = .05. Examining the form of this interaction, we found that MDD was significantly associated with higher levels of overt victimization in girls, F(1, 100) = 4.61, p < .05, but not in boys, F(1, 99) = 0.41, p = .52. Focusing next on relational victimization, we found that the main effect of mother MDD, F(1, 199) = 6.87, p < .01, but not child sex, F(1, 199) = 0.06, p = .82, was significantly related to children’s levels of relational victimization. In addition, we found a significant mother MDD × child sex interaction, F(1, 199) = 6.01, p < .05. Examining the form of this interaction, we found that MDD was significantly associated with higher levels of relational victimization in girls, F(1, 100) = 14.92, p < .01, but not in boys, F(1, 99) = 0.01, p = .91.Footnote 1

Third, we used a Cox proportional hazard regression analysis to examine the links between both forms of peer victimization and children’s time to onset of suicidal ideation, statistically controlling for the influence of mother’s history of MDD (yes, no). We found significant effects for both relational victimization, Wald = 6.74, p < .01, OR = 5.87, and overt victimization, Wald = 8.87, p < .01, OR = 7.31. However, neither of these effects was moderated by children’s sex (both ps > .60) suggesting that both forms of peer victimization were associated with the emergence of suicidal thinking in both girls and boys (even after statistically controlling for the influence of mothers’ histories of MDD).

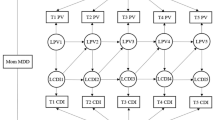

We then tested the full mediated moderation model by using model 8 in the SPSS macro PROCESS (Hayes 2013; see Fig. 2). Specifically, using a bias-corrected 95 % bootstrap confidence interval with 1,000 bootstrap samples, we evaluated the indirect effect of mother MDD on the presence of suicidal ideation in children during the follow-up (yes/no) through levels of peer victimization. Child sex was entered as a moderator of the pathways between mother MDD and relational/overt victimization and between mother MDD and child thoughts of suicide. Separate models were run for relational and overt victimization. We found a significant indirect pathway from maternal MDD to children’s suicidal ideation through overt victimization among girls, beta = 0.21, 95 % CIs = 0.02, .58, but not among boys, beta = − 0.07, 95 % CIs = −0.36, 0.12. Similarly, we found a significant indirect pathway from maternal MDD to children’s suicidal ideation through relational victimization among girls, beta = 0.29, 95 % CIs = 0.02, 0.74, but not among boys, beta = 0.01, 95 % CIs = −0.19, 0.27.Footnote 2

Diagrams of the mediated moderation models examined (PROCESS model 8 used). A significant indirect interaction between mother MDD and child sex, on the onset of suicidal ideation in children, through relational and overt forms of peer victimization. The path coefficients are unstandardized betas (see Hayes 2013). *p ≤ .05

Finally, two sets of analyses were conducted to examine the robustness of the obtained findings. First, to determine if the effects were due solely to children’s own history of depression, we re-conducted the analyses excluding children with lifetime history of MDD at baseline (n = 11). All of the significant findings were maintained. Footnote 3 Second, to determine if the effects were due to children of mothers with current depression rather than to a more trait-like vulnerability in these children, we re-conducted the analyses excluding dyads in which the mother met criteria for current MDD at the baseline assessment. In these analyses, all of the significant findings were maintained except one. In this analysis, the indirect pathway among girls from maternal MDD to suicidal ideation through relational victimization was no longer significant, beta = 0.29, 95 % CIs = −0.004, 0.92; however, the indirect pathway through overt victimization was maintained, beta = 0.32, 95 % CIs = 0.07, 0.71.

Discussion

The first goal of the present study was to conduct a longitudinal examination exploring which children of depressed mothers are at greatest risk for suicidal thoughts. We found that mothers’ history of MDD predicted time to emergence of suicidal ideation over the course of 2-year follow-up in girls, but not in boys, suggesting that maternal depression might have a stronger relation to the emergence of suicidal thinking in girls than in boys. Our second goal was to examine the potential mechanisms by which maternal depression may increase risk for suicidal thoughts in children of depressed mothers. We found that overt and relational peer victimization mediated the relation between maternal history of MDD and children’s thoughts of suicide in girls, but not in boys.

Our findings are in line with a longitudinal study conducted in a nonclinical adolescent sample that found a positive relation between overt peer victimization and an increase in suicidal ideation in girls only (Heilbron and Prinstein 2010) and extend it by suggesting that both overt and relational peer victimization in daughters of depressed mothers might partially explain the emergence of suicidal thinking in these girls. Interestingly, upon excluding the mothers with current MDD from the analyses, relational peer victimization no longer mediated the relation between maternal history of MDD and children’s thoughts of suicide in girls. This suggests that, in line with Heilbron and Prinstein’s (2010) findings, overt peer victimization might be more strongly related to suicidal thinking in daughters of depressed mothers, compared to relational peer victimization.

Although the precise mechanisms of these effects remain unclear, research confirms that adolescent girls generally experience more interpersonal stressors than boys (e.g., Hankin et al. 2007). In addition, research suggests some potential explanations of why daughters of depressed mothers might be more likely to be victimized by their peers, compared to sons of depressed mothers. For example, higher social withdrawal in girls whose mothers are depressed, compared to boys (Goodman et al. 2011), along with a range of additional interpersonal functioning problems generally experienced by children of depressed mothers (e.g., Cummings et al. 2005) might result in higher levels of victimization from peers. More research is needed to uncover potential mediators of the relation between maternal depression and levels of peer victimization in their daughters.

Similarly, although the precise mechanisms by which peer victimization increases risk for suicidal ideation are not clear, research suggests some hypotheses with regard to why daughters of depressed mothers who are victimized by their peers might be at risk for suicidal ideation. For example, studies show that children of depressed mothers, especially daughters, demonstrate impairments in various domains of emotion regulation (e.g., Silk et al. 2006). These emotion regulation difficulties might be attributed to the coping suggestions depressed mothers make to their daughters who experience interpersonal peer stress. Indeed, a recent study found that depressed mothers provided fewer cognitive restructuring and more cognitive avoidance suggestions to their children who were dealing with peer victimization (Monti et al. 2014). In addition, some studies suggest that girls demonstrate higher reactivity to similar interpersonal stressors than boys (e.g., Hankin et al. 2007). Consequently, it is possible that daughters of depressed mothers might experience suicidal thoughts as a result of their heightened reactivity to peer victimization along with poor ability to regulate these strong emotions. Future research is needed, however, in order to empirically test this hypothesis.

The present study exhibited a number of strengths, including the prospective design and the use of interviews in the assessment of diagnoses and presence of suicidal ideation. In addition, multiple informants (i.e., parent and child reports) were used in evaluating the presence of suicidal ideation at multiple assessment time-points. Further, to our knowledge, this is the first study to integrate several lines of research that have largely been kept disparate, including the sex-moderated intergenerational transmission of suicidality and the detrimental effects of peer victimization as one potential mechanism of this transmission. It is also important to note that all of our findings were maintained even when the children with the lifetime history of MDD at baseline were excluded from the analyses, suggesting that the effects do not simply stem from children’s pre-existing depression.

In addition to the present study’s strengths, there were also several limitations that provide the areas for future research. For example, the study relied on children’s self-reports when assessing overt and relational victimization, thus only reflecting perceived peer victimization. Consequently, it is important for future longitudinal research to replicate our findings by utilizing more objective and comprehensive measures of various forms of peer victimization (e.g., peer nominations, multiple informants, observational studies, laboratory paradigms). In addition, our sample was racially/ethnically homogenous, which, although reflective of the recruitment area’s demographic make-up, might limit the generalizability of our results to other populations. Further, over the course of the study, we only assessed for the presence or absence of suicidal ideation in children. It is important for future research to also examine the relations between the experiences of peer victimization and characteristic of suicidal ideation, including its frequency and severity. More work is also needed to elucidate the precise mechanisms through which relational and overt peer victimization increase the risk for suicidal thinking in daughters of depressed mothers. Importantly, additional levels of analysis should be implemented in order to uncover biological and contextual differences that might account for the disparate developmental pathways to suicide risk in girls versus boys. Finally, whereas the present study proposes one of the potential mechanisms by which maternal history of MDD might increase risk for suicidal thinking in their daughters, the process of the intergenerational transmission of suicide risk is complex and multi-faceted. Consequently, future studies should work on elucidating additional mechanisms by which this risk might be transmitted from generation to generation.

In summary, despite some limitations, the current study contributes to the understanding of risk for the emergence of suicidal thinking in children of depressed mothers, including one of the mechanisms through which this risk might be transmitted. Our findings extend previous research by suggesting that peer victimization may be one mechanism by which daughters of depressed mothers are at increased risk for suicidal thinking. The findings also highlight the importance of considering and integrating multiple contextual risk factors, including familial risk, peer relationships, and sex, in order to examine how they interact to influence developmental outcomes. Importantly, these relations appear to be at least partially independent of children’s own pre-existing depression. Our findings might also have some important clinical implications for early suicide prevention in the daughters of mothers with a history of MDD. For example, since our findings suggest that the daughters of depressed mothers experience higher levels of peer victimization, which increase their risk for developing suicidal thinking, interventions focused on promoting positive peer relationships in these at-risk girls might be effective in decreasing their future suicide risk. In addition, given our findings that the experiences of peer victimization are linked with an increased risk for suicidal thinking among daughters of depressed mothers, teaching these girls more adaptive coping strategies, including emotion regulation, might attenuate their risk for suicidality by providing these girls with better tools to cope with the experiences of peer victimization.

Notes

For the interested reader, we should note that mother MDD was significantly more strongly related to girls’ levels of relational victimization than overt victimization, z = 1.96, p = .025.

When both forms of peer victimization were entered into the model, neither was significant in predicting the emergence of suicidal thinking in children, suggesting that the effects were due to peer victimization generally rather than overt or relational victimization, specifically.

Details of these analyses are available from the first author.

References

Adrian, C., & Hammen, C. (1993). Stress exposure and stress generation in children of depressed mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61, 354–359.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

Carter, J. S., & Garber, J. (2011). Predictors of the first onset of a major depressive episode and changes in depressive symptoms across adolescence: stress and negative cognitions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120, 779–796.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012). Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [Online]. (2003). National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (producer). Available from: URL: www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars. Accessed 28 Dec 2014.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013). Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Available at: www.cdc.gov/yrbs. Accessed 15 Jan 2015.

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1996). Children’s treatment by peers: victims of relational and overt aggression. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 367–380.

Crick, N. R., Casas, J. F., & Nelson, D. A. (2002). Toward a more comprehensive understanding of peer maltreatment: studies of relational victimization. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11, 98–101.

Cummings, E. M., Keller, P. S., & Davies, P. T. (2005). Towards a family process model of maternal and paternal depressive symptoms: exploring multiple relations with child and family functioning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 479–489.

Feurer, C., Hammen, C. L., & Gibb, B. (2015). Chronic and episodic stress in children of depressed mothers. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.963859.

First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M., & Williams, J. B. W. (1995). Structured clinical interview for Axis I DSM-IV disorders—Patient edition (SCID-I/P). New York: Biometrics Research Department, NY State Psychiatric Institute.

Gershon, A., Hayward, C., Schraedley-Desmond, P., Rudolph, K. D., Booster, G. D., & Gotlib, I. H. (2011). Life stress and first onset of psychiatric disorders in daughters of depressed mothers. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45, 855–862.

Goodman, S. H., Rouse, M. H., Connell, A. M., Broth, M., Hall, C. M., & Heyward, D. (2011). Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 1–27.

Hammen, C., & Brennan, P. A. (2001). Depressed adolescents of depressed and nondepressed mothers: tests of an interpersonal impairment hypothesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 284–294.

Hankin, B. L., Mermelstein, R., & Roesch, L. (2007). Sex differences in adolescent depression: stress exposure and reactivity models. Child Development, 78, 279–295.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

Heilbron, N., & Prinstein, M. J. (2010). Adolescent peer victimization, peer status, suicidal ideation, and nonsuicidal self-injury: examining concurrent and longitudinal associations. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 56, 388–419.

Kaufman, J., Birmaher, B., Brent, D., Rao, U., Flynn, C., Moreci, P., & Ryan, N. (1997). Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children - present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 980–988.

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Borges, G., Nock, M., & Wang, P. S. (2005). Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts in the United States, 1990–1992 to 2001–2003. Journal of the American Medical Association, 293, 2487–2495.

Kim, Y. S., Leventhal, B. L., Koh, Y. J., & Boyce, W. T. (2009). Bullying increased suicide risk: prospective study of Korean adolescents. Archives of Suicide Research, 13, 15–30.

Klimes-Dougan, B., Free, K., Ronsaville, D., Stilwell, J., Welsh, C. J., & Radke-Yarrow, M. (1999). Suicidal ideation and attempts: a longitudinal investigation of children of depressed and well mothers. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 651–659.

Klimes-Dougan, B., Lee, C., Ronsaville, D., & Martinez, P. (2008). Suicidal risk in young adult offspring of mothers with bipolar or major depressive disorder: a longitudinal family risk study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64, 531–540.

Klomek, A. B., Sourander, A., Kumpulainen, K., Piha, J., Tamminen, T., Moilanen, I., & Gould, M. S. (2008). Childhood bullying as a risk for later depression and suicidal ideation among Finnish males. Journal of Affective Disorders, 109, 47–55.

Klomek, A. B., Kleinman, M., Altschuler, E., Marocco, F., Amakawa, L., & Gould, M. S. (2011). High school bullying as a risk for later depression and suicidality. Suicide and Life Threatening Behaviors, 41, 501–516.

Monti, J. D., Rudolph, K. D., & Abaied, J. L. (2014). Contributions of maternal emotional functioning to socialization of coping. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 31, 247–269.

Silk, J. S., Shaw, D. S., Skuban, E. M., Oland, A. A., & Kovacs, M. (2006). Emotion regulation strategies in offspring of childhood-onset depressed mothers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 69–78.

van Geel, M., Vedder, P., & Tanilon, J. (2014). Relationship between peer victimization, cyberbullying, and suicide in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 168, 435–442.

Acknowledgments

The project was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant HD057066 and National Institute of Mental Health grant MH098060 awarded to B. E. Gibb and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. 1120674 awarded to A. Tsypes. Any opinion, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the National Science Foundation.

We would like to thank Ashley Johnson, Lindsey Stone, Sydney Meadows, Michael Van Wie, Andrea Hanley, Katie Burkhouse, Mary Woody, Anastacia Kudinova, Effua Sosoo, Erik Funk, and Cope Feurer for their help in conducting assessments for this project.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

ᅟ

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tsypes, A., Gibb, B.E. Peer Victimization Mediates the Impact of Maternal Depression on Risk for Suicidal Ideation in Girls but not Boys: A Prospective Study. J Abnorm Child Psychol 43, 1439–1445 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-0025-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-0025-8