Abstract

Youth with psychopathic traits are at risk of engaging in physical aggression and being exposed to victimization from peers, which, in turn, is associated with symptoms of depression. The mechanisms underlying the associations between psychopathic traits, peer victimization, and subsequent depression symptoms remain unclear. Using data from the Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development (n = 2,120 youth; 49.1% female) and path analyses, we tested whether peer victimization (at 10–12 years) mediated the associations between psychopathic traits in childhood (at 6–8 years) and depression symptoms in adolescence (at 15–17 years). We also examined if the association between psychopathic traits and peer victimization was moderated by child sex, anxiety symptoms, and physical aggression. Teachers assessed psychopathic traits and peer victimization in childhood. Participants reported on their depression symptoms in adolescence. Findings showed that the association between childhood psychopathic traits and depression symptoms in adolescence was mainly indirect and (partly) operated via peer victimization. This indirect association appeared to be particularly salient for children who manifested low levels of physical aggression. The association between psychopathic traits and later depression symptoms via peer victimization could be less typical of children with high levels of physical aggression. This study highlights the importance of the mediating role of peer victimization and the moderating role of physical aggression when examining the association between psychopathic traits and subsequent depression symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Psychopathic traits are conceptualized as a constellation of affective (e.g., callousness), interpersonal (e.g., narcissism), and behavioral (e.g., impulsivity) characteristics. Initially developed from empirical and clinical data in adult populations, the construct was later extended to children and adolescents. This expansion was based on the assumption that the precursors and early manifestations of these traits could be observed at younger ages. Since then, research has shown that youth with elevated levels of psychopathic traits are at risk of severe and persistent conduct problems, such as physically aggressive behavior (Frick et al., 2014; Salekin, 2017).

In addition, psychopathic traits may also place youth at risk of peer victimization (Fanti & Kimonis, 2012; Fontaine et al., 2018). In turn, peer victimization is associated with mental health problems, such as depression symptoms (Arseneault, 2018; Olweus, 2013). Psychopathic traits are more strongly associated with conduct problems than depression symptoms, potentially because they might act as a “protective factor” for the latter (Saunders et al., 2019). Still, data suggest that psychopathic traits can be linked to depression symptoms, at least for a number of youth (Bégin et al., 2023a; Craig et al., 2021).

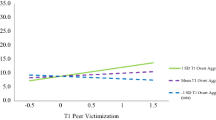

The mechanisms underlying the associations between psychopathic traits, peer victimization, and subsequent mental health problems in youth, such as depression symptoms, still need to be clarified. Using a large prospective longitudinal dataset, the main objective of the current study was to examine if peer victimization (at 10–12 years) mediated the association between psychopathic traits in childhood (at 6–8 years) and depression symptoms in adolescence (at 15–17 years) (see Fig. 1 for the baseline model). Additionally, with the aim of better understanding explanatory factors, we investigated the moderating role of child sex, anxiety symptoms and physical aggression.

Baseline model depicting the associations between psychopathic traits (6–8 years) and depression symptoms (15–17 years) via physical aggression (10–12 years) and peer victimization (10–12 years). Note. The interaction terms between psychopathic traits and (1) child sex, (2) anxiety symptoms, and (3) physical aggression were sequentially entered as predictors of peer victimization at ages 10–12 years and of depression symptoms at ages 15–17 years (see Methods and Results sections)

Sex Differences

It remains unclear if and how child sex interacts with psychopathic traits to predict peer victimization in youth. Males, compared to females, generally have in average higher levels of psychopathic traits, peer victimization and conduct problems, but lower levels of depression symptoms (Arseneault, 2018; Fanti & Kimonis, 2012; Fontaine et al., 2009). Still, although results from the few studies in which this interactive role has been formally tested suggest that child sex may not moderate the association between psychopathic traits and peer victimization (Fanti & Kimonis, 2012; Fontaine et al., 2018), replications remain needed to support this conclusion.

Variants of Psychopathic Traits

There is heterogeneity among youth with psychopathic traits. Two variants have been proposed, referred to as primary and secondary (see Craig et al., 2021). Given the relatively recent conceptualization of these variants in youth, knowledge regarding their identification, characteristics and distinct correlates is limited. The primary variant is hypothesized to be associated with genetic risk factors and to be underpinned by insufficient arousal to emotional cues and difficulty processing emotions. The secondary variant is thought to develop as a coping mechanism following exposure to adverse environmental risk factors (e.g., childhood maltreatment, family conflicts, and rejection). Psychopathic traits could therefore emerge as an adaptive process involving emotional numbing to cope with interpersonal trauma. The presence of high levels of anxiety symptoms, as a potential reaction to trauma, has been used in several past studies to distinguish the two variants. Individuals with primary and secondary variants are expected to present similar levels of psychopathic traits despite different etiologies (Craig et al., 2021). The secondary variant (characterized by high levels of psychopathic traits and anxiety symptoms) has been associated with higher levels of conduct problems and depression symptoms as well as greater exposure to adversity. However, similar levels of conduct problems across the two variants have also been reported (see Deskalo & Fontaine, 2021).

The challenges faced by youth with the secondary variant are likely to extend beyond the individual and family levels, affecting their relationships with peers. Focusing on callous-unemotional (CU) traits, the affective dimension of psychopathic traits, Bégin et al. (2021) reported that children with conduct problems who also manifested high levels of CU traits and anxiety symptoms (secondary variant) had higher initial levels of peer victimization compared to their counterparts with high levels of CU traits only (primary variant). However, the variants did not differ in terms of the mean levels of change in peer victimization over time. Similarly, Michielsen and colleagues (2022) reported that adolescents with intermediate levels of CU traits combined with high levels of anxiety/depression symptoms scored significantly higher on peer victimization than their counterparts with high levels of CU traits only.

Because exposure to adversity and trauma appears central to the etiology of secondary psychopathic traits and places youth at risk of repeated victimization (Craig et al., 2021), combined high levels of psychopathic traits and anxiety symptoms could be associated with increased levels of peer victimization, and in turn, subsequent high levels of depression symptoms. It could also be possible that the interplay between high psychopathic traits and symptoms of anxiety directly contributes to elevated levels of depression symptoms. The potential mediating role of peer victimization in the association between psychopathic traits and depression symptoms might be more evident for the secondary variant than for the primary variant.

Comorbid High Levels of Psychopathic Traits and Physical Aggression

Psychopathic traits appear more strongly linked to aggressive/bullying behavior than to exposure to peer victimization. Previous research suggests that psychopathic traits (especially CU traits) are weakly to moderately associated with peer victimization in youth cross-sectionally as well as longitudinally (Fontaine et al., 2018; Zych et al., 2019). In some cases, non-significant or negative associations were even reported (Fanti et al., 2009; Golmaryami et al., 2016). Still, youth with psychopathic traits may be likely to engage in aggressive/bullying behavior and to be victimized by others (i.e., bully-victims; Fanti et al., 2009). The associations between psychopathic traits and peer victimization may depend on the levels of conduct problems, such as aggressive/bullying behavior. Different processes could be at play and explain, at least partially, the inconsistent findings.

On one hand, youth with psychopathic traits may not be prone to experience peer victimization. They may communicate to others that they should not be taken lightly, as they may be inclined to use aggressive behavior and experience reduced feelings of guilt and empathy when causing harm. Consequently, instead of fostering victimization, these traits may act as a deterrent to potential aggressors (Pellegrini et al., 1999). This process may particularly apply to youth with combined high levels of psychopathic traits and aggressive behavior. Thus, the connection between psychopathic traits and later depression symptoms mediated by peer victimization might be less relevant for these young individuals. On the other hand, youth with high levels of psychopathic traits could engage in conduct problems (such as physically aggressive behavior toward their peers) and would therefore be likely to experience peer victimization (i.e., retaliation victimization; Fontaine et al., 2018; Pellegrini et al., 1999). Therefore, the pathway linking psychopathic traits to subsequent depression symptoms through peer victimization might be applicable for these young individuals.

Moreover, the associations between psychopathic traits and peer victimization could be explained by an additional mechanism where psychopathic traits may lead to subsequent aggressive behavior (Frick et al., 2014), which could then contribute to elevated levels of depression symptoms (Van der Giessen et al., 2013). Because hetero-aggressive behavior, such as bullying, often correlates with peer victimization (e.g., as a defensive mechanism, a mean to gain control and power, or conversely, as targets of retaliatory victimization), examining this mediation pathway alongside the previously described peer victimization pathway could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics at play.

Research Hypotheses

Although we did not rule out the possibility that psychopathic traits could be directly linked to subsequent symptoms of depression, particularly for youth with high levels of anxiety symptoms, we proposed a different hypothesis. We suggested that the association between psychopathic traits in childhood and depression symptoms in adolescence would be, at least partially, indirect, operating through exposure to peer victimization. We also expected that the association between psychopathic traits and peer victimization would not be moderated by child sex. However, we anticipated that anxiety symptoms would moderate the association between psychopathic traits and peer victimization, such that combined high levels of psychopathic traits and anxiety symptoms would be associated with elevated levels of peer victimization, and in turn, increased scores of depression symptoms. In addition, we postulated that physical aggression would moderate the association between psychopathic traits and peer victimization, such that psychopathic traits would be less strongly associated with peer victimization in children with high levels of physical aggression. The association between psychopathic traits and later depression symptoms via peer victimization would therefore be expected to be less typical of children with high levels of psychopathic traits and physical aggression.

Building on previous research, we also hypothesized that psychopathic traits in childhood would be associated with subsequent physical aggression behavior, and thereby would be linked to increased symptoms of depression in adolescence. Including this pathway also facilitated the examination of the mediating role of peer victimization, while accounting for its association with aggressive behavior. We investigated the associations between factors assessed across three important developmental periods: individual factors (e.g., psychopathic traits) during the school transition and first elementary school years (ages 6–8 years), physical aggression and peer victimization at the end of elementary school (ages 10–12 years) when relationships with peers take on new importance (Berndt, 2004) and depression symptoms in adolescence (ages 15–17 years), a time frame characterized by an elevated risk for developing clinical depression (Shorey et al., 2022).

Methods

Participants

Participants were drawn from the Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development (QLSCD), a representative sample of 2,120 youths born in the province of Quebec (Canada) in 1997 and 1998 (Orri et al., 2021). Participants were recruited through a stratified procedure based on living area and birth rate using the Quebec Birth Registry and were followed-up longitudinally. The majority of the participants was White. Informed consent was obtained from all participants at each assessment. The research protocol was approved by the Quebec Institute of Statistics and the Sainte-Justine Hospital Research Centre ethics committees.

Although all participants were included in the analyses of the current study, it should be noted that a total of 1,425 participants (n = 759 female, 53.3%) had available data on all study variables. Participants with available data on all study variables did not differ from those with at least one missing data (n = 695) in terms of the main independent study variables at ages 6–8 years (psychopathic traits, t(1,565) = 0.65, p = 0.516; peer victimization, t(161.26) = 0.70, p = 0.485, physical aggression, t(159.65) = 0.80, p = 0.426; depression symptoms, t(162.72) = 0.76, p = 0.447). However, the participants with complete data compared to the ones with at least one missing data were girls in a higher proportion (53.3% versus 40.4%; χ2(1) = 30.78, p < 0.001) and had higher socioeconomic status (t(1,265.11) = -3.94, p < 0.001).

Measures

Psychopathic Traits (6, 7, and 8 years old)

Psychopathic traits were assessed using 10 teacher-rated items based on the Social Behavior Questionnaire (SBQ; Tremblay et al., 1991; e.g., ‘Was unconcerned about the feelings of others’) when the children were aged 6, 7 and 8 years. Each item was assessed using a 3-point scale ranging from ‘never or not true’ to ‘often or very true.’ Previous investigation showed that the scale has good psychometric qualities in terms of validity and reliability indices, as well as measurement invariance across childhood (Bégin et al., 2023b). At each assessment, a scale was computed by averaging the 10 items. In the current study sample, ordinal alphas (Gaderman et al., 2012) at ages 6, 7, and 8 years were 0.94, 0.94, and 0.93, respectively. The scores across the three assessments were averaged to create the measure of psychopathic traits in childhood (rs = 0.58, 0.43, and 0.53, ps < 0.001).

Physical Aggression (6, 7, and 8 years old, and 10 and 12 years old)

Physical aggression was assessed using 9 teacher-rated items based on the SBQ (Tremblay et al., 1991; e.g., ‘Has physically attacked other people’) at 6, 7, 8, 10, and 12 years old. Each item was assessed using a 3-point scale ranging from ‘never or not true’ to ‘often or very true.’ At each assessment, a scale was created by averaging the 9 items. Ordinal alphas at ages 6, 7, 8, 10, and 12 years old were 0.96, 0.96, 0.95, 0.96, and 0.96, respectively. A baseline measure of physical aggression was computed by averaging the scores at ages 6, 7, and 8 years old (rs = 0.58, 0.44, and 0.55, ps < 0.001). This composite measure was used as a potential moderator. In addition, a putative mediator was created by averaging the scores at 10 and 12 years old (r = 0.41, p < 0.001).

Depression Symptoms (6, 7, and 8 years old)

Depression symptoms were assessed using 5 teacher-rated items based on the SBQ (Tremblay et al., 1991; e.g., ‘Has seemed unhappy or sad’) at 6, 7, and 8 years old. Each item was assessed using a 3-point scale ranging from ‘never or not true’ to ‘often or very true.’ At each assessment, a scale was created by averaging the 5 items. Ordinal alphas at ages 6, 7, and 8 years old were 0.86, 0.84, and 0.85, respectively. Baseline levels were assessed by averaging scores at the ages of 6, 7, and 8 years old (rs = 0.36, 0.31, and 0.41, ps < 0.001).

Anxiety Symptoms (6, 7, and 8 years old)

Anxiety symptoms were assessed using 4 teacher-rated items based on the SBQ (Tremblay et al., 1991; e.g., ‘Worries a lot’) at 6, 7, and 8 years old. Each item was assessed using a 3-point scale ranging from ‘never or not true’ to ‘often or very true’. At each assessment, a scale was created by averaging the 4 items. Ordinal alphas at ages 6, 7, and 8 years old were 0.86 0.85, and 0.85, respectively. The scores at the ages of 6, 7, and 8 years old were averaged to create a measure of anxiety symptoms in childhood, which was used as a putative moderator (rs = 0.29, 0.24, and 0.28, ps < 0.001).

Peer Victimization (6, 7, and 8 years old, and 10 and 12 years old)

Peer victimization was assessed by the teachers with 3 items using a 3-point scale ranging from ‘never or not true’ to ‘often or very true’ (‘Was laughed at by other children’, ‘Was hit or pushed by other children’, and ‘Was called out names by other children’). At each assessment, a scale was created by averaging the 3 items. Ordinal alphas at ages 6, 7, 8, 10, and 12 years old were 0.82, 0.82, 0.87, 0.88, and 0.91, respectively. Scores at the ages of 6, 7, and 8 years old were averaged to create the baseline measure of peer victimization (rs = 0.21, 0.21, and 0.35, ps < 0.001), and a putative mediator was created by averaging the scores at 10 and 12 years old (r = 0.31, p < 0.001).

Depression Symptoms (15 and 17 years old)

Depression symptoms were assessed using 8 self-rated items from the Mental Health and Social Inadaptation Assessment for Adolescents (MIA; Côté et al., 2017) at ages 15 and 17 years (e.g., ‘I felt sad and unhappy’). Each item was assessed using a 3-point scale ranging from ‘never true’ to ‘always true.’ Previous research showed adequate internal validity and reliability of the MIA (Côté et al., 2017). At each assessment, a scale was created by averaging the 8 items (which was converted on a 0 to 10 scale; see Côté et al., 2017). Ordinal alphas at ages 10 and 12 years old were 0.90 and 0.90, respectively. The scores from the two assessments were averaged to create the measure of depression symptoms in adolescence (outcome measure; r = 0.59, p < 0.001).

Covariates

Child sex and family socioeconomic status (SES) were included as covariates. Family SES was assessed using a standardized composite measure based on education levels of the parents, prestige levels of their occupations, and the total household income at study intake (Willms & Shields, 1996). Child sex (coded 1 = female, 0 = male) was also used as a potential moderator.

Data Analysis

We conducted path analyses with robust estimation of standard errors accounting for non-normality of study variables using Mplus version 8.10 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998). The indirect associations between psychopathic traits during childhood (6–8 years old) and depression in adolescence (15–17 years old) via peer victimization and physical aggression (10–12 years old) were assessed using a parallel two-mediator model. In this model, all variables assessed at study intake or at ages 6–8 years (i.e., sex, SES, baseline levels of depression symptoms, peer victimization, and physical aggression, as well as psychopathic traits) were used as predictors, peer victimization and physical aggression at ages 10–12 years were used as the mediators, and the measure of depression symptoms at ages 15–17 years was used as the outcome. We controlled for the direct influences of all predictors on the outcome. We also examined whether the following interaction terms were significant in the prediction of peer victimization at ages 10–12 years and in the prediction of depression symptoms at 15–17 years: (1) psychopathic traits at 6–8 years old X child sex, (2) psychopathic traits X anxiety symptoms (both at 6–8 years old) and (3) psychopathic traits X physical aggression (both at 6–8 years old). In the case of a significant moderation at p < 0.05 involving a continuous moderator (e.g., physical aggression), simple slopes were computed at low (-1 standard deviation), mean, and high (+ 1 standard deviation) values of the moderator. All continuous variables were standardized prior to analyses for interpretation purposes, but descriptive statistics are provided using unstandardized scores.

Results

Table 1 presents the mean, standard deviation and range of all variables in the study sample as a whole as well as separately for males and females. Most scores were higher in males, with effect sizes ranging from small (e.g., anxiety symptoms at baseline) to moderate-to-large (e.g., physical aggression at ages 10–12 years), but females scored higher on depression symptoms at ages 15–17 years, with a large effect size.

Table 2Footnote 1 presents the intercorrelations between the study variables (for the study sample as a whole as well as for males and females separately). Three main findings are noticeable from this table. First, for both males and females, psychopathic traits were positively associated with depression and anxiety symptoms at ages 6–8 years and physical aggression and peer victimization at ages 6–8 years and 10–12 years. Second, also for both males and females, peer victimization at ages 10–12 was concurrently positively associated with physical aggression, which supports the importance of including both variables simultaneously in the subsequent models. Third, there were slight differences across sexes in the patterns of associations with depression symptoms at ages 15–17 years: baseline depression symptoms, peer victimisation, and physical aggression, as well as peer victimization at ages 10–12 years, were associated with this outcome for males, and socioeconomic status, psychopathic traits at baseline and physical aggression at ages 10–12 years were associated with this outcome for females.

Table 3 presents results from the path analysis model estimating the indirect associations between psychopathic traits (6–8 years) and depression symptoms (15–17 years) via peer victimization (10–12 years) and physical aggression (10–12 years). As can be seen in these results, psychopathic traits in childhood were not directly associated with depression symptoms in adolescence. Rather, the association between psychopathic traits in childhood and depression symptoms in adolescence was mainly indirect and (partly) operated via peer victimization; higher levels of psychopathic traits were associated with higher levels of peer victimization, which, in turn, were associated with higher levels of depression symptoms. This association did not, however, operate via physical aggression levels at ages 10–12 years.

Including the interaction term between psychopathic traits and child sex in the prediction of peer victimization (10–12 years) in this model suggested that, despite the previously noted sex differences in most study variables, psychopathic traits increased the levels of depression symptoms via peer victimization similarly for females and males (interaction term b = 0.03, p = 0.460). Further, incorporating the interaction term between psychopathic traits and anxiety symptoms in the prediction of peer victimization (10–12 years) indicated that psychopathic traits increased the levels of depression symptoms via peer victimization regardless of the levels of anxiety symptoms (interaction term b = 0.05, p = 0.741). Finally, including the interaction term between psychopathic traits and physical aggression (6–8 years) in the prediction of peer victimization (10–12 years) suggested that the indirect association between psychopathic traits in childhood and depression symptoms in adolescence was particularly salient for children who experienced low levels of physical aggression. The interaction term between psychopathic traits and physical aggression was statistically significant (b = -0.09, p < 0.001). A breakdown of this interaction term showed that as the scores of psychopathic traits increased, the levels of peer victimization increased further when the scores of physical aggression were low (b = 0.19, p < 0.05), compared to when they were average (b = 0.10, p = 0.193) or high (b = 0.03, p = 0.964).

All interaction terms predicting depression symptoms in adolescence were not statistically significant. Child sex (b = 0.05, p = 0.382), anxiety symptoms (at ages 6–8 years; b = -0.01, p = 0.613), and physical aggression (at ages 6–8 years; b = -0.02, p = 0.313) did not moderate the association between psychopathic traits (at ages 6–8 years) and subsequent depression symptoms (at ages 15–17 years).

Discussion

The current study on the mediating role of peer victimization in the association between psychopathic traits in childhood and depression symptoms in adolescence extends previous knowledge in three keyways. First, we showed that the association between psychopathic traits (6–8 years) and later depression symptoms (15–17 years) was mainly indirect with peer victimization (10–12 years) playing a mediating role. This mechanism was tested while taking into account baseline levels (i.e., 6–8 years) of peer victimization, physical aggression, and depression symptoms, the correlation between physical aggression and peer victimization at 10–12 years, as well as child sex and family SES. Nevertheless, this indirect association appeared to be particularly salient for children who experienced low levels of physical aggression at 6–8 years. Youth with high levels of psychopathic traits but not high levels of physical aggression may face victimization from their peers as a result of retaliation or reactions to their traits or behavior (Fontaine et al., 2018; Pellegrini et al., 1999)—in this case, not because they engage in physically aggressive behavior, but potentially due to other characteristics, such as manipulative behavior or other forms of aggression (e.g., verbal or indirect aggression). For instance, psychopathic traits encompass interpersonal functioning characteristics associated with indirect aggression (Boutin et al., 2023), and the use of indirect aggression in childhood can be linked to peer victimization (Frey & Higheagle Strong, 2018). Subsequently, exposure to peer victimization in these children could be associated with an increase in their symptoms of depression during adolescence.

In contrast, the findings suggest that youth with high levels of psychopathic traits and physical aggression do not tend to experience peer victimization. This is consistent with the process suggesting that the presence of these combined characteristics could discourage potential aggressors. Hence, the association between psychopathic traits and later depression symptoms via peer victimization could be less typical of children with combined high levels of psychopathic traits and physical aggression.

Second, contrary to our expectations, anxiety symptoms did not moderate the association between psychopathic traits and peer victimization. This suggests that increased levels of psychopathic traits were associated with higher levels of depression symptoms via peer victimization irrespectively of the levels of anxiety symptoms. These findings are therefore not in line with previous studies in which researchers reported that youth from the secondary variant (i.e., psychopathic traits combined with anxiety symptoms) had higher levels of peer victimization (Bégin et al., 2021; Michielsen et al., 2022). A few methodological and developmental considerations may explain these divergent findings. To begin, the studies we reviewed on the association between variants of psychopathic traits and peer victimization in youth (i.e., Bégin et al., 2021; Michielsen et al., 2022) were based on latent profile analysis or latent class growth analysis (i.e., person-centered approaches). In the current study, we relied on a variable-centered approach (i.e., interaction between psychopathic traits and anxiety symptoms). In addition, our measure of anxiety symptoms may have been too broad of a construct to clearly examine the different presentations of psychopathic traits (Craig et al., 2021). Finally, the developmental period in which we examined psychopathic traits (6–8 years old) could account for the result. This period may potentially be too early to clearly investigate how different presentations of psychopathic traits may relate to mental health outcomes. It is still unclear when secondary psychopathic traits may emerge—it may take several years of exposure to adversity for at least some children to emotionally detach and develop secondary psychopathic traits and related mental health outcomes (Craig et al., 2021). Additional research will be crucial to further our understanding about secondary psychopathic traits, including how to define and assess them.

Third, the current findings suggest that despite sex differences in the average levels of psychopathic traits, physical aggression, and peer victimization, child sex did not moderate the association between psychopathic traits in the early elementary school years and peer victimization at the end of elementary school. This is consistent with previous research, which showed little support for a moderating role of child sex in the association between psychopathic traits and peer victimization (Fanti & Kimonis, 2012; Fontaine et al., 2018). Child sex also did not moderate the association between psychopathic traits in the early elementary school years and symptoms of depression in adolescence. Despite that the indirect mechanism we tested (psychopathic traits – peer victimization – depression symptoms) may be applicable to both males and females, future research is still warranted to investigate potential sex and gender differences. For instance, examining gender diversity beyond the binary framework could be particularly informative when studying the associations between psychopathic traits (including potential variants), peer victimization, and depression symptoms.

Strengths, Limitations, and Practical Implications

This study has several important strengths, including the use of data gathered from a large population-based sample of youth followed longitudinally and the inclusion of data collected from different sources of information across assessments (e.g., different teachers across childhood and youth’s reports during adolescence). Limitations should also be noted. First, the scale of peer victimization included only three items capturing physical victimization (one item) and relational victimization (two items). Thus, while past research showed that psychopathic traits could be more related to physical victimization than other forms of peer victimization (Fontaine et al., 2018), this general measure did not allow to conduct analyses across specific forms of peer victimization (e.g., physical versus verbal). Second, we relied on a global measure of psychopathic traits. Previous research also showed that dimensions of psychopathic traits (e.g., CU traits, narcissism, impulsivity) could relate differently to peer victimization (Despoti et al., 2021). Third, the measure of psychopathic traits in childhood was created by averaging scores from three assessments (6, 7, and 8 years old). This procedure did not allow for the consideration of potential unstable (i.e., increasing or decreasing) trajectories of psychopathic traits throughout childhood (Bégin et al., 2023b). Fourth, we relied on only one informant at each time point of assessment (i.e., teachers or self-reports). Future research using multi-informant assessments at each time point would allow verification of whether this approach incrementally contributes valuable information in explaining relevant criterion variables (e.g., depression symptoms; De Los Reyes et al., 2015). Fifth, although the statistical approach used in the current study provided a strong framework to test our hypotheses, it is not without limitations (e.g., potential confounding by unobserved variables). Alternative statistical approaches, such as fixed effects models, could be considered in future research to address these limitations. Finally, our study was based on a population-based sample of youth from the province of Quebec (Canada). Replications are needed with youth from diverse backgrounds to examine the generalizability of the findings, including from clinical populations.

In sum, this study is among the first to address the mediating role of peer victimization in the association between psychopathic traits in childhood and depression symptoms in adolescence. The findings suggest that youth with high levels of psychopathic traits and physical aggression may not be prone to peer victimization, and therefore may be less inclined to develop depression symptoms. However, these young individuals are likely to engage in aggressive behavior and to cause harm to others. Peer victimization is associated with long-term negative consequences, such as depression symptoms as showed in the current study.

Youth presenting with higher levels of psychopathic but with low levels of aggressive behavior could benefit from interventions aimed at preventing or reducing peer victimization (e.g., implementing strategies that modify the school environment to reduce opportunities and rewards for bullying; Olweus & Limber, 2010). These young people, if exposed to peer victimization, could also benefit from interventions aimed at addressing depression symptomatology (e.g., mental health preventive interventions provided by school psychologists). At the same time, youth exhibiting high levels of both psychopathic traits and physically aggressive behavior could also be selected for targeted bullying intervention programs to deter them from engaging in such behaviors. For instance, interventions focusing on close supervision by adults or peer mentors preventing physically aggressive behavior being rewarded combined with a system of rewards for prosocial behavior may be promising (Viding et al., 2009).

Data Availability

Data used in this study are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Notes

Table 2 also shows a high bivariate correlation between psychopathic traits and physical aggression at ages 6-8 years (i.e., r = .87 in the total sample). This strong correlation was anticipated (Frick et al., 2014). To ensure that this issue did not result in collinearity problems in the subsequent path analyses, we conducted sensitivity analyses where we re-ran the main analytical model, each time excluding one of the two highly correlated predictors. As detailed in Table S1 of the supplementary materials, most associations remained unchanged when each predictor was removed, including the association between psychopathic traits (at 6-8 years) and peer victimization (at 10-12 years). In the sensitivity models, the main differences observed were: (1) stronger associations between psychopathic traits/physical aggression (at 6-8 years) and physical aggression (at 10-12 years), and (2) a significant association between physical aggression (at 6-8 years) and peer victimization (at 10-12 years). These exceptions are likely attributable to the shared variance between psychopathic traits (at 6-8 years) and physical aggression (at 6-8 years). When examining their unique contribution after partialing out their commonality, psychopathic traits, but not physical aggression at ages 6-8 years, remained significantly associated with peer victimization at ages 10-12 years. Hence, these sensitivity analyses suggest that the strong correlation between these predictors did not introduce collinearity issues in the main analyses.

References

Arseneault, L. (2018). Annual research review: The persistent and pervasive impact of being bullied in childhood and adolescence: Implications for policy and practice. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(4), 405–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12841

Bégin, V., Déry, M., & Le Corff, Y. (2021). Variant of psychopathic traits follow distinct trajectories of clinical features among children with conduct problems. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 49, 775–788. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-021-00775-3

Bégin, V., Fontaine, N. M. G., Vitaro, F., Boivin, M., Tremblay, R. E., & Côté, S. M. (2023a). Childhood psychopathic traits and mental health outcomes in adolescence: Compensatory and protective effects of positive relationships with parents and teachers. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 32(8), 1403–1413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-01955-2

Bégin, V., Fontaine, N. M. G., Vitaro, F., Boivin, M., Tremblay, R. E., & Côté, S. M. (2023b). Perinatal and early-life factors associated with stable and unstable trajectories of psychopathic traits across childhood. Psychological Medicine, 53, 379–387. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721001586

Berndt, T. J. (2004). Children’s friendships: Shifts over a half-century in perspectives on their development and their effects. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 50(3), 206–223. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.2004.0014

Boutin, S., Bégin, V., & Déry, M. (2023). Impacts of psychopathic traits dimensions on the development of indirect aggression from childhood to adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 59(9), 1716–1726. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001582

Côté, S. M., Orri, M., Brendgen, M., Vitaro, F., Boivin, M., Japel, C., Séguin, J. R., Geoffroy, M.-C., Rouquette, A., Falissard, B., & Tremblay, R. E. (2017). Psychometric properties of the Mental Health and Social Inadaptation Assessment for Adolescents (MIA) in a population-based sample. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 26(4), e1566. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1566

Craig, S. G., Goulter, N., & Moretti, M. M. (2021). A systematic review of primary and secondary callous-unemotional traits and psychopathy variants in youth. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 24, 65–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-020-00329-x

De Los Reyes, A., Augenstein, T. M., Wang, M., Thomas, S. A., Drabick, D. A. G., Burgers, D. E., & Rabinowitz, J. (2015). The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 141(4), 858–900. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038498

Deskalo, A., & Fontaine, N. M. G. (2021). Examining callous-unemotional traits and anxiety in a sample of incarcerated adolescent females. Juvenile and Family Court Journal, 72(1), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfcj.12193

Despoti, G., Constantinos, M. K., & Franti, K. A. (2021). Bullying, victimization, and psychopathy in early adolescents: The moderating role of social support. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 18(5), 747–764. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2020.1858787

Fanti, K. A., Frick, P. J., & Georgiou, S. (2009). Linking callous-unemotional traits to instrumental and non-instrumental forms of aggression. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 31, 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-008-9111-3

Fanti, K. A., & Kimonis, E. R. (2012). Bullying and victimization: The role of conduct problems and psychopathic traits. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22(4), 617–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00809.x

Fontaine, N., Carbonneau, R., Vitaro, F., Barker, E. D., & Tremblay, R. E. (2009). Research review: A critical review of studies on the developmental trajectories of antisocial behavior in females. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(4), 363–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01949.x

Fontaine, N. M. G., Hanscombe, K. B., Berg, M. T., McCrory, E. J. P., & Viding, E. (2018). Trajectories of callous-unemotional traits in childhood predict different forms of peer victimization in adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 47(3), 458–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1105139

Frey, K. S., & Higheagle Strong, Z. (2018). Aggression predicts changes in peer victimization that vary by form and function. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46, 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-017-0306-5

Frick, P. J., Ray, J. V., Thornton, L. C., & Khan, R. E. (2014). Can callous-unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 1–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033076

Gaderman, A. M., Guhn, M., & Zumbo, B. D. (2012). Estimating ordinal reliability for likert-type and ordinal item response data: A conceptual, empirical, and practical guide. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 17(3), 2–13. https://doi.org/10.7275/n560-j767

Golmaryami, F. N., Frick, P. J., Hemphill, S. A., Kahn, R. E., Crapanzano, A. M., & Terranova, A. M. (2016). The social, behavioral, and emotional correlates of bullying and victimization in a school-based sample. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-9994-x

Michielsen, P. J. S., Habra, M. M. J., Endendijk, J. J., Bouter, D. C., Grootendorst-van Mil, N. H., Hoogendijk, W. J. G., & Roza, S. J. (2022). Callous-unemotional traits and anxiety in adolescents: A latent profile analysis to identify different types of antisocial behavior in a high-risk community sample. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 16(58), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-022-00493-8

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus User’s Guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Olweus, D. (2013). School bullying: Development and some important challenges. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 751–780. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516

Olweus, D., & Limber, S. P. (2010). Bullying in school: Evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80(1), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01015.x

Orri, M., Boivin, M., Chen, C., Ahun, M. N., Geoffroy, M.-C., Ouellet-Morin, I., Tremblay, R. E., & Côté, S. M. (2021). Cohort profile: Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development (QLSCD). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(5), 883–894. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01972-z

Pellegrini, A. D., Bartini, M., & Brooks, F. (1999). School bullies, victims, and aggressive victims: Factors relating to group affiliation and victimization in early adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(2), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.91.2.216

Salekin, R. T. (2017). Research review: What do we know about psychopathic traits in children? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(11), 1180–1200. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12738

Saunders, M. C., Anckarsäter, H., Lundström, S., Hellner, C., Lichtenstein, P., & Fontaine, N. M. G. (2019). The associations between callous-unemotional traits and symptoms of conduct problems, hyperactivity and emotional problems: A study of adolescent twins screened for neurodevelopmental problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(3), 447–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-018-0439-1

Shorey, S., Ng, E. D., & Wong, C. H. J. (2022). Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Cinical Psychology, 61(2), 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12333

Tremblay, R. E., Loeber, R., Gagnon, P., Charlebois, P., Larivée, S., & LeBlanc, M. (1991). Disruptive boys with stable and unstable high behavior patterns during junior elementary school. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 19(3), 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00911232

Van der Giessen, D., Branje, S., Overbeek, G., Frijns, T., van Lier, P. A. C., Koot, H. M., & Meeus, W. (2013). Co-occurrence of aggressive behavior and depressive symptoms in early adolescence: A longitudinal multi-informant study. Revue Européenne De Psychologie Appliquée, 63, 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2013.03.001

Viding, E., Simmonds, E., Petrides, K. V., & Frederickson, N. (2009). The contribution of callous-unemotional traits and conduct problems to bullying in early adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(4), 471–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02012.x

Willms, D. J., & Shields, M. (1996). A measure of socioeconomic status for the National Longitudinal Study of Children (No. 9607). Fredericton, NB: Atlantic Center or Policy Research in Education, University of New Brunswick and Statistics Canada.

Zych, I., Ttofi, M. M., & Farrington, D. P. (2019). Empathy and callous-unemotional traits in different bullying roles: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 20(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380166834

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the participants. We thank Alain Girard for support with the statistical analyses. This work, as part of the Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development (QLSCD), was supported by the Quebec Government’s Ministry of Health and Ministry of Family Affaires, the Lucie and André Chagnon Foundation, the Quebec Research Funds – Society & Culture, the Quebec Research Funds – Health, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Nathalie M. G. Fontaine is a Research Scholar, Junior 2, Quebec Research Funds – Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Fontaine, N.M.G., Bégin, V., Vitaro, F. et al. Psychopathic Traits in Childhood and Depression Symptoms in Adolescence: the Mediating Role of Peer Victimization. J Dev Life Course Criminology (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-024-00259-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-024-00259-0