Abstract

Rejection sensitivity (RS) has been defined as the tendency to readily perceive and overreact to interpersonal rejection. The primary aim of this study was to test key propositions of RS theory, namely that rejecting experiences in relationships with parents are antecedents of early adolescents’ future RS and symptomatology. We also expanded this to consider autonomy-restrictive parenting, given the importance of autonomy in early adolescence. Participants were 601 early adolescents (age 9 to 13 years old, 51 % boys) from three schools in Australia. Students completed questionnaires at school about parent and peer relationships, RS, loneliness, social anxiety, and depression at two times with a 14-month lag between assessments. Parents also reported on adolescents’ difficulties at Time 1 (T1). It was anticipated that more experience of parental rejection, coercion, and psychological control would be associated with adolescents’ escalating RS and symptoms over time, even after accounting for peer victimisation, and that RS would mediate associations between parenting and symptoms. Structural equation modelling supported these hypotheses. Parent coercion was associated with adolescents’ increasing symptoms of social anxiety and RS over time, and parent psychological control was associated with increasing depressive symptoms over time. Indirect effects via RS were also found, with parent rejection and psychological control linked to higher T1 RS, which was then associated with increasing loneliness and RS. Lastly, in a separate model, peer victimisation and RS, but not parenting practices, were positively associated with concurrent parent reports of adolescents’ difficulties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Experiencing rejection by parents or by peers can have detrimental effects on child and adolescent socioemotional functioning, resulting in increased symptoms of depression, anxiety, and problem behaviours (Collins and Steinberg 2007; Marston, Hare, and Allen 2010; McCarty, Vander Stoep, and McCauley 2007; Zimmer-Gembeck, Hunter, and Pronk 2007). One explanation for why rejection experiences culminate in mental health problems is rejection sensitivity (RS), a social emotional processing style that involves the enhanced expectation of being rejected in future relationships and an overly negative emotional response to situations that involve any threat of rejection, relatedness, or lack of belonging (Downey, Bonica, and Rincon 1999; Downey and Feldman 1996; Zimmer-Gembeck and Nesdale 2013). Thus, RS theory suggests that experiences of rejection result in the development of symptoms of psychopathology via individuals’ development of a greater sensitivity to rejection, and the related negative social and emotional events that it precipitates (Downey et al. 1999).

This model of the development of mental health difficulties via rejection and RS has received empirical support. Yet, most studies have been focused on adolescent or adult RS and peer, romantic, or marital relationships. For example, multiple studies have found that peer rejection has detrimental effects on RS (Chango, McElhaney, Allen, Schad, and Marston 2012; Downey et al. 1999; Downey and Feldman 1996; London, Downey, Bonica, and Paltin 2007; McLachlan, Zimmer-Gembeck, and McGregor 2010; Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2014). In comparison, only four studies, three cross-sectional (McDonald et al. 2010; McLachlan et al. 2010; Rudolph and Zimmer-Gembeck 2014) and one longitudinal (Downey, Lebolt, and Rincon 1995) have been conducted focused on parenting and child or adolescent RS. In one cross-sectional study, negative parenting practices were associated with heightened RS, and RS mediated the association of negative parenting practices with depression and social anxiety symptoms (Rudolph and Zimmer-Gembeck 2014). In a second cross-sectional study, parental support mediated the effect of RS on depression symptoms in adolescents (McDonald et al. 2010). In the third cross-sectional study, positive parenting practices were shown to buffer the impact of peer rejection on increased RS (McLachlan et al. 2010). In the only longitudinal findings published to date, Downey et al. (1995) found that children who reported higher amounts of perceived parental rejection showed higher expectations of being rejected in social situations 1 year later. Finally, only one of these previous studies examined the unique roles of parental and peer rejection in RS. In this study of children age 9 to 13 years (McLachlan et al. 2010), parent and peer rejection each uniquely contributed to heightened RS. However, peer rejection was found to be a stronger predictor of RS than parental rejection. Taken together, no longitudinal study has examined RS as a mediator linking multiple parenting practices to changes in early adolescents’ symptoms of mental health problems over time.

It is surprising that so little study of parenting and RS in childhood and early adolescence exists given that the family has a strong socialising presence and parents are more important than peers for companionship and social support for this age group (see Collins and Steinberg 2007 for a review). Also, there is a very long history in psychology of theories that propose that children develop cognitive models about themselves and others based on early caregiving experiences (e.g., Bowlby 1969; Feldman and Downey 1994; Rohner 1975). In one of these theories, Feldman and Downey (1994) described RS as an “internalized legacy of early rejection experiences” (p. 232). Moreover, parents have been found to exhibit subtle messages of rejection or lack of acceptance through use of behaviours such as judging, devaluing, intruding, or showing indifference (Barber 1996; Skinner, Johnson, and Snyder 2005; Steinberg, Elmen, and Mounts 1989). All of these parent behaviours have been associated with children’s symptoms of disorder, including elevated symptoms of social anxiety and depression (e.g., Kerr 2001). Thus, the range of subtle and overt expressions of parental rejection may be as important as peer rejection to understanding RS and its symptoms in children.

The primary purpose of the current longitudinal study was to examine a range of negative parenting practices to determine the temporal influences on RS and symptomology among young people age 9 to 13 years. Symptoms of depression, social anxiety, problem behaviours, and loneliness were addressed in the current study. Evidence has suggested association between RS and all of these problems in past research (Chango et al. 2012; Downey et al. 1998a; London et al. 2007; McDonald et al. 2010; McLachlan et al. 2010; Rudolph and Zimmer-Gembeck 2014; Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2014). Thus, our study aim was to extend these findings to understand parenting, RS, and symptom changes over time. The parenting practices investigated were founded in the motivational theories of parenting practices and cover a range of overt and more subtle parenting behaviours that can undermine relatedness, belongingness, and feelings of acceptance (Connell and Wellborn 1991; Deci and Ryan 1985; McGregor, Zimmer-Gembeck, and Creed 2012a, b).

The secondary purpose of the present study was to determine whether the impact of parenting practices on RS and symptoms was unique after accounting for early adolescents’ reports of their peer victimisation. Victimisation has been identified as an aspect of peer relationship difficulties that is often strongly associated with reduced child and adolescent well-being (Crick and Nelson 2002; Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2014). For example, Crick and Nelson (2002) found that victimised children reported increased social difficulties and internalising and externalising symptoms following relational and/or physical victimisation that occurred within friendships. More recently, Zimmer-Gembeck and Duffy (2014) found relational victimisation by peers was the strongest correlate of higher self-reported RS in their study of relational and overt forms of victimisation and friendship problems. Given the links between victimisation and well-being reported in the literature, the association between relational peer victimisation and early adolescents’ socioemotional symptoms was also examined in the present study.

Parenting Practices and RS

Often considered the foundations of positive parenting, positive parenting practices such as parental support, warmth, and limit setting have been linked to children’s enhanced feelings of relatedness, a greater capacity for autonomous behaviour, and adaptive social and emotional functioning (Baumrind 1991; Masten and Garmezy 1985; Skinner et al. 2005; Steinberg and Silk 2002; Zimmer-Gembeck, Ducat, and Collins 2011). However, some parenting practices that imply or clearly demonstrate rejection have been linked to an increased likelihood of mental health symptoms in childhood and adolescence (as well as in adulthood). These are generally hostile parenting practices that imply or overtly display rejection, coercion, or psychological control (Skinner et al. 2005). All of these negative parenting practices have been linked to higher levels of internalising and externalising symptoms in adolescence (e.g., Barber 1996; Steinberg and Silk 2002) and adolescents’ less adaptive social functioning (Wood, McLeod, Sigman, Hwang, and Chu 2003).

Parental rejection includes overt and covert displays of disliking, dismissing, and disapproving of the child and his or her behaviour. Children can perceive parental rejection when they seek help and support from their parent and are instead met with criticism, harshness, or negative emotional reactions. Parental psychological control, as defined by Barber (1996), also has relevance to undermining autonomy but can be subtler in form. Psychological control refers to negative, intrusive attempts by the parent to emotionally and behaviourally control the autonomy or choice of the child. Lastly, coercive parenting practices are over-controlling and restrict the child’s attempts at autonomy and demand the child’s obedience to parental requests of control (Skinner et al. 2005). Together, these rejecting and controlling aspects of parenting can undermine and restrict adolescents’ strivings to have their needs for relatedness, undermine their feelings of competence, and restrict autonomous actions (Connell and Wellborn 1991; Deci and Ryan 1985; Skinner et al. 2005). In early adolescence and adolescence, a time when autonomy development is very salient (Zimmer-Gembeck and Collins 2003), such autonomy-restrictive parenting practices have been linked to depression and externalising behaviours (see Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2011 for a review). As the first social relationship, the parent–child relationship is an opportunity for children to learn competence, confidence, and optimism about future social relationships. However, in the face of negative parenting experiences, adolescents may develop expectations of social rejection, abandonment, and RS in regards to future social relationships.

The Current Study

In summary, the purpose of the present longitudinal, multi-informant study was to test components of the RS model, as proposed by Downey and Feldman (1996), by examining associations of early adolescents’ perceptions of rejection, coercion, and psychological control in the parent-adolescent relationship and their RS and socioemotional symptoms. Specifically, we were interested in the unique associations between autonomy-restricting and rejecting aspects of parenting and a range of socioemotional symptoms, and the role of RS in these associations. Thus, the three autonomy-restricting parenting practices were examined to identify unique associations of each with concurrently higher levels of and increasing RS and socioemotional symptoms over time. We had two general hypotheses. First, parental rejection, coercion, and psychological control were expected to be correlates of greater concurrent RS, as well as increased RS at T2 relative to T1 (Hypothesis 1). Second, autonomy-restrictive parenting practices and RS at T1 were expected to be associated with higher levels of emotional and behavioural symptoms, and greater increases in symptoms, over time (Hypothesis 2). The hypothesised effects were expected to be direct as well as through T1 and T2 RS. In addition, peer relational difficulties, specifically peer victimisation, were examined to account for the known effects of peer problems on elevated RS and symptoms (Downey et al. 1999; Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2014). Symptoms were assessed via both child and parent report.

Method

Participants

The participants were 601 early adolescents (age 9 to 13 years at T1, M age = 11, SD = 0.98, 51 % boys, 49 % girls) from three urban Australian public schools. Participants completed two surveys separated by 14 months. The sample was 90 % white Australian with 10 % indicating they were from other sociocultural backgrounds (e.g., Indigenous Australian people, Maori/Pacific Islander, Asia, Middle East). At T1, 649 students completed the survey, but 42 (7 %) did not participate at T2 because they could not be recontacted and six parents did not complete a survey, which collected demographic information and parents’ assessment of their children’s socioemotional functioning. Parents (86 % mothers, 14 % fathers) completed consent forms and a measure of child functioning at T1. At T1, the consent rate was just over 70 %.

Procedure

Once ethical approval was obtained from the University Human Subjects Review Committee, schools were approached to participate in the study. Parental consent was obtained for all participants. Before completing questionnaires students also gave consent to participate. Questionnaires were completed during class, while research assistants and teachers were present. At T1, questions were read aloud while children completed a paper booklet of questionnaires under the supervision of a research assistant. Children, teachers, and schools were provided with a small thank you gift following their participation. Participating children were recontacted via their school for follow-up 14 months later and were invited to participate again during class time.

Measures

Total Difficulties

At T1 parents completed the 25-item Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire for 3- to 16-year-olds (SDQ; Goodman 1997) as a measure of their child’s difficulties. Items tapped emotional (“Has many worries”), conduct (“Often fights with other children”), and hyperactivity/inattention (“Easily distracted”) problems. To avoid overlap with peer victimisation, the subscale of peer difficulties was not used. All other subscale scores were averaged to construct a total difficulties score. The response options ranged from 1 (Not true) to 3 (Certainly true) for two schools, and from 1 (Not true) to 5 (Certainly true) for one school. Because of these different response options across schools, each item was standardised within school after items with positive valence were reversed, Cronbach’s α =. 77.

Depressive Symptoms

Adolescents completed the widely used Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs 1985) at T1 and T2 to assess depressive symptoms. The 10-item version of the CDI was used to assess the presence and severity of depressive symptoms. Respondents choose from three options which best describes them. For example: “I feel like crying every day, I feel like crying many days, I feel like crying once in a while”. Response options ranged from 1 to 3 for each item. Five items were reverse scored before all items were summed to create a total score for use in analyses, with higher scores reflecting more symptoms. Cronbach’s α’s in the present study were 0.82 at T1 and 0.83 at T2.

Social Anxiety

To measure social anxiety at T1 and T2, adolescents completed 14 items from the Social Anxiety Scale for Children – Revised (SASC-R; La Greca and Stone 1993). Response options ranged from 1 (Not at all true) to 5 (Very true). The items assess fear of negative evaluation (“I worry what other kids think of me”), inhibition in novel social contexts (“I get nervous when I talk to kids I don’t know very well”), and inhibition in known social contexts (“I feel shy even with kids I know very well”). Items were averaged within the three subscales and these three scores were averaged to produce a total score, α = 0.86 at T1, α = 0.88 at T2. The scale has shown to have sound psychometric properties including convergent and discriminant validity (La Greca and Stone 1993).

Loneliness

The Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Questionnaire (LSDQ; Cassidy and Asher 1992), completed by adolescents, was used to measure loneliness. The 13-item scale had response options ranging from 1 (Not at all true) to 5 (Very true). Example items include, “I feel alone”, “I feel left out”, and “I can find a friend when I need one”. Scores for nine items were reversed in order to ensure that higher scores reflected more loneliness. Items were then averaged to produce a total score for each participant. The LSDQ has shown to be an accurate measure of loneliness with children’s scores on the LSDQ correlating with other social behaviour measures and teachers reports of children’s loneliness (Cassidy and Asher 1992). Cronbach’s α’s in the present study 0.89 at T1 and 0.91 at T2.

RS

The Child Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire (CRSQ; Downey et al. 1998b) was used to measure RS at T1 and T2. A shortened version of the CRSQ was used with six written scenarios involving peers and teachers (e.g., “You had a really bad fight with a friend the other day. You wonder if your friend will want to talk to you today”). Following each vignette, participants responded to three questions. The first two questions for each scenario assessed anxious and angry responses by asking how nervous and how mad they would feel in the situation. Responses to these items ranged from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Extremely). The third question asked about expectation of acceptance, with responses from 1 (NO!) to 5 (YES!). As is standard practice for this measure (Downey et al. 1998b), a RS anxious score and a RS angry score were calculated for each scenario. These were computed by reversing the response to the expectation item then multiplying this by the item measuring the child’s degree of nervous/anxiety or mad/anger over its occurrence. An overall RS anxious score and an overall RS angry score was calculated by averaging the scores for each scenario. These two scores were correlated at r = 0.63 (T1) and r = 0.69 (T2), both p < 0.01. For analyses, these two subscales were summed to create a total RS score where higher scores indicated greater RS responses1. The CRSQ has been shown to be a valid measure of reactions to rejection with convergent and divergent validity previously demonstrated with measures of hostile intent and social competence (Downey et al. 1998b). In the current study, Cronbach’s α’s were 0.83 and 0.87 at T1 and T2, respectively.

Parenting Practices

At T1, adolescents completed the Parents as Social Context Questionnaire (PSCQ; Skinner et al. 2005) to measure their perceptions of negative parenting practices. The scale has previously shown to have good convergent validity between parent and child ratings of parenting practise (Skinner et al. 2005). Two subscales of the PSCQ, of four items each, were used to measure parental rejection (“Sometimes I wonder if my parents like me”, Cronbach’s α = 0.72) and coercion (“My parents are always telling me what to do” Cronbach's α = 0.76). Responses ranged from 1 (Not at all true) to 5 (Very true). Total scores were obtained by averaging items on each subscale.

To measure psychological control at T1, the Psychological Control Scale – Youth Self Report (PCS-YSR; Barber 1996) was utilised. An example item is: “My parents are always trying to change how I feel or think about things.” To match the response scale on the PSCQ, the PCS-YSR response format was adapted from a 3- to a 5-point scale of 1 (Not at all true) to 5 (Very true). Total scores were obtained by averaging the items. Previous studies have demonstrated the reliability of the scale across multiple samples of adolescents (Barber 1996). The scale showed acceptable reliability in the current sample, Cronbach's α = 0.72.

Peer Victimisation

To assess peer victimisation at T1, items from the Children’s Social Behaviour Scale (Crick and Grotpeter 1995) and modified by Zimmer-Gembeck and Pronk (2012) were used to measure overt and relational peer victimisation at T1. Overt victimisation (3 items) included items about harm through physical aggression, verbal threats, or instrumental intimidation. For example, “Kids threaten to or do push, shove or hit me”. Relational victimisation (4 items) includes items about harm through damage and manipulation of peer relationships. For example, “Kids leave me out on purpose”. Response options ranged from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (A lot). A total score was obtained by averaging the items for each type of victimisation and then summing the two scores. The scale has shown to be a reliable and valid measure of peer relationships with good convergent and discriminant validity (Crick and Grotpeter 1995; Zimmer-Gembeck and Pronk 2012), Cronbach’s α = 0.86.

Data Analysis Plan

We first examined Ms, SDs, and zero-order correlations between all variables. Following this, the hypothesised cross-sectional and longitudinal paths between autonomy-restrictive parenting practices, RS, and early adolescent symptoms were tested with structural equation modelling (SEM). Models were estimated using AMOS software with maximum likelihood estimation (Arbuckle 2012). Model fit was assessed with commonly used indices, including the χ2-test and associated level of significance, and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) (Bentler and Bonett 1980). The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) (Browne and Cudeck 1993) provided an estimate of error due to approximate fit of the models. In order to test the unique associations between parenting and adolescents’ symptomology, parent rejection, coercion, and psychological control were included as separate constructs in the model. All constructs in the models were indicated by a single measured variable. Because parents reported on their children's symptoms only at T1, this was not included in the SEM models. Instead, associations of T1 parenting practices, RS, and parent reported difficulties of their children were investigated using hierarchical regression modelling.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

Before testing the study hypotheses, variable distributions were examined. All distributions significantly departed from normality, but no outliers were identified. To address the non-normal distributions, variables were log transformed, which corrected the skew to some extent. However, the transformed variables showed highly similar intercorrelations when compared to the correlations between untransformed variables, with a maximum difference of 0.05. Due to this similarity, the large sample size, and the robustness of estimations provided in SEM (Byrne 2009; McDonald and Ringo Ho 2002), untransformed variables were utilised in the analysis reported here, but results from bootstrapping are also provided. Bootstrapping has been found to increase power and accuracy by not depending on normal theory assumptions but, instead, drawing estimates from the data (Shrout and Bolger 2002). Bootstrapping was implemented using AMOS (Byrne 2009; Zimmer-Gembeck, Chipuer, Hanisch, Creed, and McGregor 2006) to estimate direct, indirect, and total effects.

Correlations

Table 1 provides Ms, SDs, and correlations between all measures. As expected, all measures were intercorrelated in a positive direction, all p < 0.01. Adolescents’ perceptions of autonomy-restrictive and rejecting parenting practices and their peer victimisation were associated with their heightened levels of depressive and social anxiety symptoms, and loneliness. Further, parenting measures were moderately intercorrelated, r’s ranged from 0.47 to 0.54, suggesting that they do capture somewhat different aspects of problem parent-adolescent relationships. All parenting practices were associated with heightened RS. RS was significantly associated with all other measures, as well. Lastly, RS and symptoms were moderately stable over the 14 months of the study, r’s ranged from 0.42 to 0.57.

The correlations of age and gender with other measures were also examined (see Table 1). Younger relative to older participants reported more parent rejection, but no other significant association with age was found. Gender had numerous associations with the primary study variables (Table 1). Girls reported more peer victimisation and RS (at T2) than boys and parents reported that their girls had less total difficulties than boys. Finally, girls were higher in social anxiety at T1 and at T2, and they were higher in depressive symptoms at T2. Given these associations, gender was accounted for in the regression and SEM analyses. Age was not included in subsequent analyses, as it showed only one significant correlation with other measures.

Parent Reported Socioemotional Symptoms and Parent-Adolescent Relationships

To examine whether negative parenting practices and RS were concurrently associated with parent reported adolescent difficulties, and whether RS mediated the association of parenting practices with concurrent parent reported difficulties, hierarchical linear regression was used. Parent reported SDQ symptoms collected at T1 were regressed on T1 parenting measures, RS, peer victimisation, and gender (see Table 2). Gender was entered in Step 1, followed by parental rejection, coercion, and psychological control in Step 2. In Step 3, RS was added to the model before peer victimisation was added in Step 4.

Overall, the model was significant, F (7, 600) = 11.53, p < 0.01 (see Table 2). In Step 2, parental rejection was associated with more parent reported difficulties and in Step 3 adolescents who were higher in RS were higher in parent-reported difficulties. After Step 4, however, the association between parent rejection and adolescents’ difficulties was no longer significant. Instead, RS and peer victimisation were the only two measures that were significantly associated with higher levels of parent reported difficulties of their children.

Structural Model of Parenting Practices, RS, and Socioemotional Symptoms

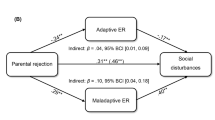

Next, we fit SEM models in order to test all expected associations of parenting, RS, and adolescent-reported symptoms. After fitting a saturated model to test all possible associations, we trimmed the model. In this trimmed model, we removed the nonsignificant correlations within each time of measurement, and all nonsignificant paths from gender to T2 measures. This model had an adequate fit to the data, χ2(14) = 85.26, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.092 (90 % CI = 0.074 to 0.111) p < 0.001. All significant standardised direct paths are displayed in Fig. 1.

Significant standardised path coefficients between autonomy-restricting parenting practices, rejection sensitivity, and measures of adolescents’ socioemotional symptoms at Time 1 (T1) and Time 2 (T2) (N = 601). Model Fit: χ2(14) = 85.26, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.092 (90 % CI = 0.074 to 0.111) p < 0.001. For clarity, only significant paths are shown. However, all significant covariances between T1 measures and between T2 measures, and all other directional paths, were estimated; nonsignificant coefficients ranged from -0.01 to 0.08. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

In regards to concurrent associations between T1 parenting practices and T1 RS, adolescents who reported more parent psychological control and rejection were higher in RS at T1, as predicted. Parent coercion was not significantly associated with concurrent RS. Of the T1 symptom measures, only social anxiety was associated with a higher concurrent level of RS.

Regarding longitudinal associations between parenting practices and symptoms, parent psychological control and coercion, but not rejection, were associated with increased symptoms by T2. Adolescents who reported more psychological control at T1 showed an increase in depressive symptoms at T2 relative to T1. Adolescents who reported more parent coercion reported an increase in social anxiety and RS at T2 relative to T1. Finally, adolescents higher in RS at T1 reported more loneliness at T2 relative to T1. Peer victimisation at T1 was associated with greater depression by T2 relative to T1.

Bootstrapped estimates of the direct, indirect (via T1 RS) and total effects of negative parenting practices on T2 depressive symptoms, social anxiety symptoms, loneliness, and RS are shown in Table 3. As can be seen, there were three significant indirect effects, whereby parent psychological control and rejection were associated with T2 loneliness via T1 RS, and parent rejection was associated with T2 RS via T1 RS. However, one of these indirect effects was only marginally significant, p = 0.06. Overall, there were four significant (and one marginally significant) total effects of T1 parenting on T2 symptoms or RS. Parental psychological control was associated with adolescents’ increased depression by T2, parental coercion was associated with increased social anxiety and RS by T2, and parental rejection was associated with increased loneliness by T2. Also, there was a marginally significant association of parental coercion with increased depression by T2.

Discussion

Theory suggests that parenting practices can have long-lasting effects on children’s well-being because they are foundations of their internalised views of relationships and generalised expectations of whether they will be accepted, rejected, supported, or dismissed by others (Barber 1996; Bowlby 1969; Downey et al. 1998a; Rapee 1997; Rudolph and Zimmer-Gembeck 2014; Skinner et al. 2005). In the current study, we considered how early adolescents’ self-reported experiences of rejecting and controlling parenting practices would be associated with a socioemotional bias toward expecting rejection and reacting with heightened negative emotion when it is anticipated, referred to as RS (Downey and Feldman 1996). We also investigated whether RS and rejecting and autonomy-restrictive parenting practices were associated with adolescents’ elevated symptoms of loneliness, depression, social anxiety, and parent-reported adolescent difficulties. These associations were examined concurrently and 14-months-later while accounting for peer victimisation, in order to better isolate the specific effects of negative parenting practices on adolescents’ RS and symptoms. The current findings are some of the first to support the RS model when applied to a range of overt and subtle negative parenting practices and one of the first to show that these associations hold even after peer relationship problems are considered.

Parenting and Increases in Early Adolescents’ RS Over Time

Overall, Hypothesis 1 was supported in that adolescents’ reports of autonomy-restrictive parenting practices uniquely contributed to their heightened RS both concurrently and over time. This finding supports theoretical links between parenting and adolescent’s internal expectations of social relationships and hypothesised links in the RS model between adolescents’ perceptions of parental rejection and increased RS (Feldman and Downey 1994). In one of the only other previous studies to test the association between parental rejection and RS, McLachlan and colleagues (2010) also found an association between reported parent rejection and heightened RS in early adolescents. In the present study, although adolescents’ who perceived greater parent rejection and psychological control concurrently reported heightened RS, only parent coercion was found to have a significant direct effect on RS at T2. The defensive reactions seen in RS have been described as the result of exposure to situations in which rejection is implied by important others (Levy, Ayduk, and Downey 2001). Coercive parenting practices which are autonomy-restricting may be a more subtle form of rejection as they involve constraint of individual self-development and may communicate disapproval and dismissal of the adolescents’ psychological autonomy by demanding obedience and conformity at a time when autonomous functioning is desired and emerging (Wood et al. 2003; Zimmer-Gembeck and Collins 2003). Thus, as suggested by the findings of the current study, the effect of parental coercion on children’s RS may become more apparent over time and as children attempt to exert more autonomy during the developmental period of adolescence. For example, if adolescents’ attempts to exert autonomy are met with parental coercion and subsequent restriction of these autonomous behaviours, adolescents may develop the social-cognitive processing style associated with RS and expect to be rejected in future social relationships.

This conclusion is consistent with previous findings that experiences of parental coercion lead to angry, submissive, oppositional, or withdrawn reactions to interpersonal interactions and a resistance to socialisation, all traits associated with RS (Skinner et al. 2005). Rubin, Nelson, Hastings, and Asendorpf (1999) described how children who exhibited shyness or social withdrawal can influence their parent’s behaviour by potentially eliciting over-controlling parenting practices, suggesting a potential link between coercive parenting and social anxiety in adolescents. However, few studies have isolated parental coercion from rejection or psychological control when examining contributions of parenting to children’s RS. Thus, this finding identifies a particular parenting quality that seems important to identifying why RS increases over time during early adolescence, above and beyond the high stability that was found in RS for most children in the present study and in past research (Downey and Feldman 1996; London et al. 2007; Marston et al. 2010).

Autonomy-Restrictive Parenting, RS, and Early Adolescents’ Socioemotional Functioning

Overall, associations were found between negative parenting practices, RS, and emotional and behavioural functioning of early adolescents, supporting Hypothesis 2. Negative parenting experiences were related to elevations in adolescents’ symptoms; however different parenting practices were associated with different difficulties. The parenting practices correlated with increasing symptoms over time were those that are autonomy-restrictive, rather than overt rejection. First, parental coercion at T1 was directly associated with increases in social anxiety symptoms over time. This finding is consistent with the literature on negative parenting and the impact that early parent–child experiences can have on adolescent social functioning (e.g., Anhalt and Morris 2008; Campos et al. 2013). Few studies have measured parental coercion specifically, although previous studies have shown links between autonomy-restrictive parenting and adolescents’ social anxiety (see Wood et al. 2003). In further support of the importance of autonomy-restrictive parenting during adolescence, we also found parent psychological control was associated with increases in depression symptoms over time.

Parenting behaviours, such as coercion and control, which reduce children’s independence and provide fewer opportunities for children to develop mastery, may increase children’s anxiety about being able to manage situations alone. Further, subtle parenting behaviours such as intrusion, control, and demandingness have been theoretically linked to increased social fearfulness in children and difficulty navigating social relationships (e.g., Rapee 1997; Rubin et al. 1999; Wood et al. 2003). For example, Rapee (1997) suggests that parents, who take control when their children encounter stressful situations, may increase children’s fears about their environment, resulting in excessive dependence on parents and heightened anxiety about social encounters. Our findings highlight the need for further investigation on autonomy-relevant parenting and developmental outcomes in order to better understand the links between these parenting behaviours and socioemotional symptoms in adolescence.

According to the Self-system Model of Motivational Development (Connell and Wellborn 1991; Deci and Ryan 1985; Grolnick 2002) a parent–child relationship that is coercive and controlling can disrupt children’s development of the self-system processes required for socialisation and can affect their strivings towards relatedness, competence, and autonomy. Therefore, negative parenting experiences can affect adolescents’ self-efficacy, their psychological agency, and promotes difficulty in their social relationships such as their ability to relate to others. The findings of the present study support the conclusion that parenting, which is characterised by coercion and psychological control, may disrupt adolescents’ opportunities to develop confidence and competence, having negative effects on both conceptions of the self and emotionality. Self-concept and emotional responding are aspects of depressive symptoms, as well as being linked to greater fears of negative evaluation and wariness of novel and familiar social situations, which are aspects of social anxiety symptoms.

Longitudinal effects indicated that parental rejection was associated with higher levels of loneliness at T2, indirectly through RS at T1. This finding provides support for Hypothesis 2 of the current study, and extends the findings of a previous cross-sectional study reporting that RS was associated with greater loneliness in adolescents (London et al. 2007). More specifically, in the present study, parent rejection was associated with greater loneliness only indirectly via increased RS. It is surprising that similar indirect associations were not found for depressive or social anxiety symptoms over time, however. Previous research has found support for increased cognitive, emotional, and behavioural difficulties associated with the cognitive processing style of RS (London et al. 2007; Zimmer-Gembeck and Nesdale 2013). However, in contrast to these previous studies, negative parenting practices were associated with increasing social anxiety and depressive symptoms directly, but not indirectly via RS.

Parents’ Reports of Their Adolescents’ Difficulties

Parents’ reports of their adolescents’ overall difficulty, including difficult behaviour, emotionality, and hyperactivity, was the only measure of adolescent functioning that was not associated with negative parenting practices. Instead, it was relational peer victimisation and expectation of being rejected that significantly predicted parents reports of behavioural difficulties and emotionality. We found that peer victimisation was the largest contributor to parents reporting of greater difficulties, a finding similar to that of McLachlan et al. (2010). Since parent-report of difficulties was the only measure that focused on behavioural problems in addition to emotional problems, this suggests that it may be that peer victimisation is more closely associated with behavioural problems, whereas negative parenting practices may be relevant to understanding children’s self-perceived social and emotional problems in the early adolescent years. Moreover, because we only collected parent reports at T1, it was adolescents who reported more victimisation and RS who had parents who reported that they had more difficulties. It is possibly, and indeed likely, that difficulties assessed by parents, including aggression, hyperactivity and emotionality, may be as much a precursor as they are outcomes of peer victimisation and RS. Indeed, Downey and Feldman’s (1996) model of RS and previous research (Downey et al. 1998a) suggests a looping effect between the overly negative response to perceived rejection seen in individuals high in RS and the increase occurrence of rejection as a result of such behavioural and emotional reactions in social situations.

The cross-sectional association found here does not rule out this alternative association or the likelihood of bidirectional associations. Previous research has found bidirectional associations between adolescents’ socioemotional symptoms and adolescents’ perceptions of parent practices (see Crouter and Booth 2003; Van Zalk and Kerr 2011). Further, multiple previous studies have shown that peer victimisation can predict increasing behaviour or emotional problems at the same time that problems can predict increased peer victimisation over time (Crick and Nelson 2002; Downey et al. 1998a; Graham, Bellmore, and Juvonen 2003; Zimmer-Gembeck and Duffy 2014; Zimmer-Gembeck, Hunter, Waters, and Pronk 2009).

Peer Victimisation

It should also be mentioned that peer victimisation was a consistent correlate of early adolescent socioemotional functioning, with adolescents’ reporting of peer victimisation being directly associated with depressive symptoms over 1 year later. This finding is consistent with the adolescent literature, which indicates that at this age peer victimisation is associated with overall difficulties and difficulties in peer relationships, the most important social relationship during adolescence (see Collins and Steinberg 2007 for a review). Yet, the findings also show that negative parenting practices still account for elevations in adolescents’ symptoms even after accounting for peer victimisation.

Study Limitations, Future Research, and Conclusion

In summary, the present findings demonstrated the roles of RS and negative parenting practices, particularly autonomy-restrictive parenting, above and beyond peer victimisation, in accounting for adolescents’ loneliness, social anxiety, and depressive symptoms. Although parents’ reports of the difficulties of their children were also considered, one notable limitation of the study is the reliance on mostly youth self-report. Second, the theories on which this study was founded emphasise the role of parenting practices in children’s development of patterns of social-cognitive processing and the development of symptoms over time. Future research could examine the likely bidirectional associations between children’s symptomology and parenting practices. Such a study would benefit by having three waves of data but also measuring parents’ RS as a mediator that may explain when adolescents’ symptoms are associated with changes in parenting practices (Crouter and Booth 2003; Van Zalk and Kerr 2011). Another study extension might be to measure positive, autonomy supportive parenting, as well as the negative autonomy-restrictive parenting practices of coercion and psychological control, in order to determine parenting strategies that may protect against RS and symptoms.

Clinically, the findings of the study signify the importance of considering overt, subtle, and implied forms of rejection by both parents and peers when working with adolescents who are exhibiting difficulties with emotion regulation, social relationships, and behaviour. However, the non-clinical nature of the sample and the low average levels of symptomology reported by adolescents in the current study should be considered when drawing clinical implications from this study. The findings of the current study indicate that RS, even by adolescence, is a socioemotional cognitive processing style that is related to both negative parenting practices and socioemotional difficulties. Thus, these findings uniquely contribute to the knowledge of the influences that overt and covert parental rejection and control can have on early adolescents’ expectations in future relationships.

References

Anhalt, K., & Morris, T. L. (2008). Parenting characteristics associated with anxiety and depression: a multivariate approach. Journal of Early and Intensive Behaviour Intervention, 5, 122–137. Retrieved from http://www.jeibi.com/.

Arbuckle, J. L. (2012). Amos (Version 21.0). Chicago: IBM Corporation.

Barber, B. K. (1996). Parental psychological control: revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development, 67, 3296–3319. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01915.x.

Baumrind, D. (1991). The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. Journal of Early Adolescence, 11, 56–95. Retrieved from http://www. http://mltei.org.com

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588–606. Retrieved from http://www.cob.unt.edu/slides/paswan/busi6280/Bentler_Bonnett_1980.pdf.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sage Focus Editions, 154, 136–136. doi:10.1037//1082-989X.7.4.403.

Byrne, B. M. (2009). Structural equation modelling with Amos: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

Campos, R. C., Besser, A., & Blatt, S. J. (2013). Recollections of parental rejection, self-criticism and depression in suicidality. Archives of Suicide Research, 17, 58–74. doi:10.1080/13811118.2013.748416.

Cassidy, J., & Asher, S. R. (1992). Loneliness and peer relations in young children. Child Development, 63, 350–365. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01632.x.

Chango, J. M., McElhaney, K., Allen, J. P., Schad, M. M., & Marston, E. (2012). Relational stressors and depressive symptoms in late adolescence: rejection sensitivity as a vulnerability. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 369–379. doi:10.1007/s10802-011-9570-y.

Collins, W. A., & Steinberg, L. (2007). Adolescent development in interpersonal context. In R. M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology. New York: Wiley.

Connell, J. P., & Wellborn, J. G. (1991). Competence, autonomy and relatedness: A motivational analysis of self-system processes. In M. Gunnar & L. A. Sroufe (Eds.), Minnesota symposium on child psychology (Self processes in development, Vol. 23, pp. 43–77). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development, 66, 710–722. doi:10.1111/j.1467624.1995.tb00900.x.

Crick, N. R., & Nelson, D. A. (2002). Relational and physical victimisation within friendships: nobody told me there’d be friends like these. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30, 599–607. Retrieved from http://springerlink.bibliotecabuap.elogim.com/.

Crouter, A. C., & Booth, A. (Eds.). (2003). Children’s influence on family dynamics: The neglected side of family relationships. Mahwah, NJ; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.

Downey, G., & Feldman, S. I. (1996). Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 1327–1343. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1327.

Downey, G., Lebolt, A., & Rincon, C. (1995). The development of a measure of rejection sensitivity for children. Unpublished manuscript.

Downey, G., Freitas, A. L., Michaelis, B., & Khouri, H. (1998a). The self-fulfilling prophecy in close relationships: rejection sensitivity and rejection by romantic partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 545–560. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.2.545.

Downey, G., Lebolt, A., Rincón, C., & Freitas, A. L. (1998b). Rejection sensitivity and children’s interpersonal difficulties. Child Development, 69, 1074–1091. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06161.x.

Downey, G., Bonica, C., & Rincon, C. (1999). Rejection sensitivity and adolescent romantic relationships. In W. Furman, B. Bradford Brown, & C. Feiring (Eds.), The development of romantic relationships in adolescence (pp. 148–174). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Feldman, S., & Downey, G. (1994). Rejection sensitivity as a mediator of the impact of childhood exposure to family violence on adult attachment behaviour. Development and Psychopathology, 6, 231–247. doi:10.1017/S0954579400005976.

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 581–586. doi:10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015.

Graham, S., Bellmore, A., & Juvonen, J. (2003). Peer victimisation in middle school. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 19, 117–137. doi:10.1300/J008v19no2_08.

Grolnick, W. S. (2002). The psychology of parental control: How well-meant parenting backfires. New York: Psychology Press.

Kerr, M. (2001). Culture as a context for temperament: Suggestions from the life courses of shy Swedes and Americans. In T. D. Wachs & G. A. Kohnstamm (Eds.), Temperament in context (pp. 139–152). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kovacs, M. (1985). The children’s depression inventory (CDI). Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 21, 995–998.

La Greca, A. M., & Stone, W. L. (1993). Social anxiety scale for children – revised: factor structure and concurrent validity. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 22, 17–27. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp2201_2.

Levy, S. R., Ayduk, O., & Downey, G. (2001). The role of rejection sensitivity in people’s relationships with significant others and valued social groups. In M. R. Leary (Ed.), Interpersonal rejection (pp. 251–289). New York: Oxford University Press.

London, B., Downey, G., Bonica, C., & Paltin, I. (2007). Social causes and consequences of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17, 481–506. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00531.x.

Marston, E. G., Hare, A., & Allen, P. (2010). Rejection sensitivity in late adolescence: social and emotional sequelae. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20, 959–982. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00675.x.

Masten, A., & Garmezy, N. (1985). Risk, vulnerability, and protective factors in developmental psychopathology. In B. Lahey & A. Kazdin (Eds.), Advances in Clinical Child Psychology (Vol. 8, pp. 1–52): New York: Springer.

McCarty, C. A., Vander Stoep, A., & McCauley, E. (2007). Cognitive features associated with depressive symptoms in adolescence: directionality and specificity. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 36, 147–158. doi:10.1080/15374410701274926.

McDonald, R. P., & Ringo Ho, M.-H. (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 7, 64–82. doi:10.1037//1082-989X.7.1.64.

McDonald, K., Bowker, J. C., Rubin, K. H., & Laursen, B. (2010). Interactions between rejection sensitivity and supportive relationships in the prediction of adolescent internalizing difficulties. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 563–574. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9519-4.

McGregor, L., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Creed, P. A. (2012a). Family structure, interparental conflict and parenting as correlates of children’s relationship expectations. Journal of Relationships Research, 3, 44–56. doi:10.1017/jrr.2012.6.

McGregor, L., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Creed, P. A. (2012b). Development and validation of the children’s optimistic and pessimistic expectations of relationships scale. Australian Psychologist, 47, 58–66. doi:10.1111/j.1742-9544.2011.00053.x.

McLachlan, J., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & McGregor, L. (2010). Rejection sensitivity in childhood and early adolescence: peer rejection and protective effects of parents and friends. Journal of Relationships Research, 1, 31–40. doi:10.1375/jrr.1.1.31.

Rapee, R. M. (1997). Potential role of childrearing practices in the development of anxiety and depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 17, 47–67. doi:10.1016/S02727358(96)00040-2.

Rohner, R. P. (1975). They love me, they love me not: A worldwide study of the effects of parental acceptance and rejection. New Haven, CT: HRAF Press.

Rubin, K. H., Nelson, L. J., Hastings, P., & Asendorpf, J. (1999). The transaction between parents’ perceptions of their children’s shyness and their parenting styles. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 23, 937–957. doi:10.1080/016502599383612.

Rudolph, J., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2014). Parent relationships and adolescents’ depression and social anxiety: indirect associations via emotional sensitivity to rejection threat. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66, 1–13. doi:10.1111/ajpy.12042.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445. doi:10.1037//1082-989X.7.4.422.

Skinner, E., Johnson, S., & Snyder, T. (2005). Six dimensions of parenting: a motivational model. Parenting: Science and Practice, 5, 175–235. doi:10.1207/s15327922par0502_3.

Steinberg, L., & Silk, J. S. (2002). Parenting adolescents. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting (Vol. 1, pp. 103–133). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Steinberg, L., Elmen, J. D., & Mounts, N. S. (1989). Authoritative parenting, psychosocial maturity, and academic success in adolescents. Child Development, 60, 1424–1436.

Van Zalk, N., & Kerr, M. (2011). Shy adolescents’ perceptions of parents’ psychological control and emotional warmth: examining bidirectional links. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 57, 375–401. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.

Wood, J. J., McLeod, B. D., Sigman, M., Hwang, W. C., & Chu, B. C. (2003). Parenting and childhood anxiety: theory, empirical findings, and future directions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44, 134–151. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.0010.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Collins, W. A. (2003). Autonomy development during adolescence. In G. R. Adams & M. Berzonsky (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of adolescence (pp. 175–204). Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Duffy, A. L. (2014). Heightened emotional sensitivity intensifies associations between relational aggression and victimization among girls but not boys: a longitudinal study. Developmental Psychopathology, 26, 661–673. doi:10.1017/S0954579414000303.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Nesdale, D. (2013). Anxious and angry rejection sensitivity, social withdrawal, and retribution in high and low ambiguous situation. Journal of Personality, 81, 29–38. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2012.00792.x.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Pronk, R. E. (2012). Relation of depression and anxiety to self-and peer-reported relational aggression: associations with peer group status and differences between boys and girls. Sex Roles, 68, 363–377. doi:10.1007/s11199-012-0239-y.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Chipuer, H. M., Hanisch, M., Creed, P. A., & McGregor, L. (2006). Relationships at school and environmental fit as resources for adolescent engagement and achievement. Journal of Adolescence, 29, 911–933. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.008.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Hunter, T. A., & Pronk, R. (2007). A model of behaviours, peer relations and depression: perceived social acceptance as a mediator and the divergence of perceptions. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26, 273–302. doi:10.1521/jscp.2007.26.3.273.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Hunter, T. A., Waters, A. M., & Pronk, R. (2009). Depression as a longitudinal outcome and antecedent of preadolescents’ peer relationships and peer-relevant cognitive. Developmental Psychopathology, 21, 555–577. doi:10.1017/S0954579409000303.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Ducat, W., & Collins, W. A. (2011). Autonomy development during adolescence. In B. B. Brown & M. Prinstein (Eds.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 66–76). New York: Academic Press.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Trevaskis, S., Nesdale, D., & Downey, G. A. (2014). Relational victimisation, loneliness and depressive symptoms: Indirect associations via self and peer reports of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 568–582. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-9993-6.

Acknowledgments

The research was conducted in accordance with APA guidelines for ethical conduct of research. All authors have agreed to the content and submission of this paper along with the order of authors. We acknowledge that this study was supported by a grant from the Australian Research Council, grant number DP1096183. The authors wish to thank Professor Geraldine Downey for her early contribution to this work. We also thank Leanne McGregor, Haley Webb, Belinda Goodwin, Shawna Mastro and a large number of staff and volunteers who managed and assisted with data collection. Finally, we acknowledge the approval provided by Education Queensland and the school and student participation; without this support, this project would not have been possible.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rowe, S.L., Gembeck, M.J.Z., Rudolph, J. et al. A Longitudinal Study of Rejecting and Autonomy-Restrictive Parenting, Rejection Sensitivity, and Socioemotional Symptoms in Early Adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol 43, 1107–1118 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9966-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9966-6