Abstract

Externalising behaviours such as substance misuse (SM) and conduct disorder (CD) symptoms highly co-ocurr in adolescence. While disinhibited personality traits have been consistently linked to externalising behaviours there is evidence that these traits may relate differentially to SM and CD. The current study aimed to assess whether this was the case, after examining the nature of the relationship between SM and CD symptoms in an adolescent sample (N = 392), using structural equation modelling. Similar to those found in adults (Krueger et al. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 116: 645–666, 2007), results showed that CD and SM symptoms were organized hierarchically, with symptoms explaining a single broad, coherent construct of externalising behaviour, but also explaining specific factors of SM and CD that vary independently from the general externalising factor. Furthermore, disinhibited personality traits related differentially to these factors, with results showing that, even controlling for inhibited personality traits, impulsivity was associated with CD and the common variance shared by CD and SM, while sensation seeking was specifically associated with SM only. Hopelessness was also associated with the common variance shared by SM and CD. Results confirm impulsivity, hopelessness and sensation seeking as key correlates of externalising behaviour problems in adolescence, identifying them as clear targets for intervention and prevention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Externalising behaviours such as substance misuse and conduct disorder have been shown to be highly comorbid in adolescence (Armstrong and Costello 2002; Costello et al. 2003; Fergusson et al. 1993). For example, Wells et al. (2007) found that binge drinking co-occurs with adolescent reports of anti-social behaviour and aggression, while Roberts et al. (2007), who looked at prevalence and associations of a large number of psychiatric disorders with different forms of substance misuse in adolescence, showed that the strongest associations were found for disruptive behaviours, including conduct disorder symptoms and substance misuse, regardless of severity or substance being used.

For some, the high rates of co-ocurrence between substance misuse and antisocial behaviours highlights the need for careful assessment of confounding substance misuse when studying antisocial behaviours and vice versa (e.g. Sher and Trull 1994). For others, this highlights the need to study both the unique and common variance shared among externalising behaviours (e.g. Krueger 1999; Krueger et al. 2002). Indeed, there are several models that attempt to explain the high rates of co-occurrence between these disorders (see Conrod and Stewart 2005; Klein and Riso 1993; Neale and Kendler 1995; and Thombs 2006 for reviews). Among models that attempt to explain the high rate of comorbidity between substance misuse and conduct disorder, causation models (i.e. one disorder operates as a risk factor for the subsequent onset of the other disorder) and reciprocal causation models (i.e. each disorder may have a distinct aetiology, but may have common or overlapping courses of illness that exacerbate each other over time) receive some support (e.g. Brook et al. 2000; Pardini, et al. 2007; White et al. 2001). However, most current research findings support common factor or correlated liability models, which posit that one or multiple common risk factors between two disorders give rise to comorbidity (e.g. Agrawal et al. 2004; Conrod and Stewart 2005; Krueger et al. 1998; Neale and Kendler 1995). Amongst a number of potential “common” aetiologic factors between comorbid disorders, genetic (Jang et al. 2000; Slutske et al. 1998), neuro-cognitive (Cantrell et al. 2008; Petry 2002), temperament and personality traits (Caspi et al. 1997; Krueger et al. 1998; Kwapil 1996) feature strongly. For example, in a meta-analysis of twin and epidemiological studies, Krueger and Markon (2006) showed that the covariance among all types of substance misuse and different components of antisocial behaviour (including conduct disorder symptoms as well as antisocial behaviour with age of onset after the age of 15) could be modelled by a single underlying externalising factor, which could, in turn, best be modelled as a quantitative continuum. Several recent studies have supported this model (e.g. Hicks et al. 2007; Krueger et al. 2007; Patrick 2008).

It is important to highlight that while much support is found for this highly heritable externalising factor (e.g. Hicks et al. 2007; McGue et al. 2006), support has also been found for specific genetic and environmental contributions to each of the subfactors (i.e. substance misuse and conduct disorder) that compose the externalising factor (Agrawal et al. 2004; Grant et al. 2006; Kendler et al. 2003; Krueger et al. 2002; McGue et al. 2006; Young et al. 2000), with recent evidence showing that distinct substance use disorders are associated with distinct genetic factors (Kendler et al. 2003, 2007). Consistent with this, are findings from Krueger et al. (2007) showing that while indicators (variables) of antisocial behaviour and substance misuse, as well as disinhibited personality, both measured a general externalising factor well, they also measured more specific sub-factors of antisocial behaviour (i.e. more severe aggressive behaviour) and substance misuse (i.e. drug use) that are not correlated with the general factor. The authors concluded that while substance misuse and antisocial behaviours can be expressions of the same underlying liability to an externalising spectrum, individual variability exists within these behaviours that is not associated with variability in the other set of symptoms, which suggests, in turn, multiple pathways to specific clinical outcomes (Krueger et al. 2007). Although Krueger and colleagues provide novel methods of studying these nosological issues, studies on child psychopathology going as far back as the 60s and 70s have been interested in the commonalities (variance shared) among specific disorders (e.g. “narrow-band syndromes”, i.e. aggressive, delinquent, hyperactive) to identify “broad-band syndromes”, such as “under-controlled syndrome” (for reviews, see Achenbach and Edelbrock 1978, 1984). In line with this work, it is important to question not only what makes substance misuse and conduct disorder comorbid, but also whether there is anything truly unique about those who are only using substances versus those who are antisocial substance users (i.e. those that are also engaging in shoplifting/vandalism), or even those who are only engaging in antisocial behaviours other than substance use. While this line of research helps explain why substance misuse and other externalising symptoms frequently co-occur and, in the case of Krueger and colleagues’ work, illustrates how disinhibited traits are closely linked to externalising behaviour problems, it also leaves open the possibility that multiple disinhibited personality traits contribute to these latent constructs in different ways.

Certainly, disinhibited personality traits have been consistently linked to antisocial behaviour (Sher and Trull 1994; Krueger et al. 2002; Tremblay et al. 1994), as well as substance misuse (Conrod et al. 2000, 2006; Masse and Tremblay 1997), and even to the comorbidity of these disorders (Kahn et al. 2005; Slutske et al. 2002). However, although general factor models of personality typically identify only one factor for disinhibition, extensive research has been carried out on the differentiation between different dimensions of disinhibited personality (Eysenck et al. 1985; Patton et al. 1995), as well as the differentiation between different behavioural/ cognitive measures of disinhibition (Lane et al. 2003; Olson et al. 1999; Reynolds et al. 2006). Reviewing studies on both self-report and behavioural measures of disinhibition, there seems to be consensus that there are at least two distinct subfactors of disinhibition or impulsivity (e.g. Dawe and Loxton 2004; Eysenck and Eysenck 1992; Lane et al. 2003; Reynolds et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2007; Zuckerman and Kuhlman 2000). There is evidence that these two subfactors make reference to distinct disinhibited tendencies or behaviours, with one, generally referred to as impulsivity, conceptualized as a deficit in reflectiveness and planning, rapid decision-making and action, and a failure to inhibit a behaviour that is likely to result in negative consequences (e.g. Baumeister and Vohs 2004; Schalling 1978). In contrast, the second, referred to in this study as sensation seeking, is generally defined as a strong need for stimulation, a low tolerance to boredom, and a willingness to take risks for the sake of having novel and varied experiences (Arnett 1994; Zuckerman 1979). This subdivision is similar to that made by others which identify two factors reflecting cognitive disinhibition/ impulsivity on the one hand, and approach tendencies/ reward sensitivity on the other (Dawe and Loxton 2004; De Wit and Richards 2004; Quilty and Oakman 2004).

The distinction between facets of disinhibition is supported by studies showing that not only are impulsivity and sensation seeking associated with distinct facets of substance misuse, but also with distinct motivational profiles/predispositions to these behaviours. For example, Smith et al. (2007) found that sensation seeking is a distinct disinhibited factor that only mildly correlates with other disinhibited traits like urgency—described as a tendency to act rashly when distressed—and lack of planning—tendency not to think or plan before acting—, but also that sensation seeking is related to the frequency of substance misuse and other risky behaviours, while urgency is associated with problematic measures of substance misuse and risky behaviours, including antisocial behaviours. Similarly, Conrod and colleagues found that sensation seeking was not only associated crossectionally with binge drinking (Conrod et al. 2006) but also predicted increased binge drinking rates across adolescence (Conrod et al. 2008). Impulsivity did not predict drinking, but a subsequent study on a larger sample of adolescents showed a specific relationship between impulsivity and illicit substance use (Conrod et al. 2010). Evidence that disinhibited personality traits relate to different patterns of substance misuse and other problem behaviours, is consistent with research highlighting that impulsivity and sensation seeking map on to different motivational processes (Conrod et al. 2000, 2006; Finn et al. 2002; Woicik et al. 2009). While sensation seeking has been shown to be associated with substance misuse through a drive for increased stimulation and positive emotions (Comeau et al. 2001), impulsivity appears to be associated with substance misuse through a motivationally undefined pattern of use (Simons et al. 2005; Woicik et al. 2009), possibly reflecting a general inability to inhibit behaviours (e.g. Finn et al. 2002) rather than a motivational need to regulate an affective state. Consistent with this, Finn et al. (2000) suggested that impulsivity (as measured by a social deviance score) and sensation seeking (as measured by the disinhibition and boredom susceptibility subscales of Zuckerman’s Sensation Seeking Scale) represented two separate biopsychosocial pathways that led to alcohol problems in individuals with a family history of alcoholism. They described impulsivity as being associated with deficits in self regulation (as measured by commission errors on a go no-go task), while the sensation-seeking pathway was described as involving traits associated with Gray’s Behavioural Activation System functioning, mesolimbic dopamine circuitry, and sensitivity to pleasurable activities (Finn et al. 2000). Furthermore, other studies have provided support for the involvement of independent neural mechanisms and genetic influences in these two personality-mediated pathways to substance misuse (e.g. Belin et al. 2008; Mustanski et al. 2003).

Although the main focus of this paper was to explore how two distinct disinhibited traits are associated to the unique and common variance shared among externalising behaviours in adolescence, it is important to mention that inhibited traits, particularly those related to neuroticism and negative affect, have also been implicated in externalising behaviours (e.g. Benning et al. 2003; Conrod et al. 2000; Frick and Morris 2004; Hicks et al. 2004; Lynam et al. 2005). Neuroticism is a broad personality construct that reflects negative emotionality, behavioural inhibition and anxiety (Barlow 2000), and as with disinhibited personality traits, can be subdivided in to sub-dimensions. Research on the structure of neurotic personality generally identifies “negative affect” representing a higher order factor common to all neurotic traits, and two lower order factors, associated with low positive affect (similar to what is referred to as hopelessness in this study) and fear (similar to what is referred to anxiety sensitivity in this study), accounting for unique variance in specific sets of traits and disorders (Clark and Watson 1991). These sub-dimensions have also been shown to relate differentially to substance misuse and other externalising behaviours. For example, while the higher order dimension of neuroticism appears to be inconsistently related to risk for substance use disorders (e.g., Zimmermann et al. 2003), the lower order facet of hopelessness has been consistently shown to be associated with particular aspects of substance use in adolescents (e.g. Conrod et al. 2006; Woicik et al. 2009) and adults (e.g. Conrod et al. 2000; Stewart et al. 2001). Negative affect and hopelessness have also been associated with other externalising behaviours and antisocial behaviours (e.g. Hicks, et al. 2004; Lynam et al. 2005; Mackie et al., in press). On the other hand, while anxiety sensitivity has been linked to substance use in adulthood (e.g. Conrod et al. 2000; Stewart et al. 2001), no studies have shown a significant association between this trait and other externalising behaviour problems. Indeed, there is some evidence showing that low levels, as opposed to high levels, of anxiety or fear are associated with antisocial behaviours (Fowles 1980; Walker et al. 1991). Finally, a number of studies have also suggested that impulsivity or low levels of reactive control predict externalising behaviours only in combination or interaction with negative emotionality (e.g. Eisenberg et al. 2000, 2001). Thus it is deemed important to include inhibited traits in models assessing externalising behaviours, not only to assess how both inhibited and disinhibited traits related to each other, but to assess whether the effects of disinhibited personality traits are independent of the effects of inhibited traits on these behaviours.

The Current Study

There is substantial and growing support for common factor models of comorbidity, especially the “externalising spectrum” model, but also some support for the differentiation between behaviours which form part of the externalising factor. Within this context, this study had two main objectives. The first objective was to examine the nature of the relationship between substance misuse and conduct disorder symptoms in adolescence, by testing several models of comorbidity. These models, based mainly on the work of Krueger et al. (2007), were evaluated using structural equation modelling. The second main objective of this study was to examine how two disinhibited personality traits—impulsivity (IMP) and sensation seeking (SS)—differentially relate to substance misuse, conduct disorder, and their comorbidity. In order to assess how inhibited traits are associated with externalising behaviours in adolescence as well as to assess the effects of disinhibited traits on externalising behaviours, independent of the effects of inhibited traits, measures of hopelessness and anxiety sensitivity were entered as covariates.

These analyses were considered important for a number of reasons. This study would provide confirmation of Krueger et al.’s (2007) model of externalising behaviour in an adolescent sample. This would not only validate their model of externalising behaviour at a different developmental period, but would also allow one to control for some of the confounding issues implicated in studying these behaviours in adulthood, namely issues related to prolonged or continued substance use. Studies have shown that increased and persistent substance misuse may result in higher levels of antisocial behaviours (e.g. Johnson et al. 1995), but also deficits in response inhibition and decision-making (e.g. Ersche et al. 2006; Verdejo et al. 2005) and even increased levels of trait impulsivity (e.g. de Win et al. 2007). Thus, it is important that substance misuse and its comorbidity with other symptoms is studied before severe substance misuse has started. This study assessed adolescents across a period of time which is considered not only as a crucial developmental period for the initiation of substance use, but also represents the limited window of time when the comorbidity between substance misuse and conduct disorder, as well as vulnerability to both these disorders, can truly be examined. That is, although conduct disorder is typically assessed in childhood, substance misuse cannot be evaluated in childhood as, generally, it has yet to be initiated. In this study, adolescents were assessed from ages 13 to 16 years, which are considered by many to be peak years for substance use initiation (D’Amico and McCarthy 2006; Patton et al. 2004), but because of the short substance misuse history of this young sample and the relatively infrequent binge drinking and drug use reported in substance users, it is more likely that findings on the association between disinhibition and substance misuse are indicative of disinhibition conferring risk for substance misuse, rather than disinhibition as a neuro-toxic consequence of severe substance use. Furthermore, the longitudinal nature of this study allowed the link between disinhibited personality variables assessed at age 14 and externalising behaviour symptoms across early adolescence to be assessed. Thus, the aim was to establish whether personality traits can explain the unique and/or common variance shared between substance misuse (SM) and conduct disorder (CD) symptoms in adolescence. These models would then allow general and unique risk factors for these behaviours to be identified, which could then inform more refined investigations into the underlying mechanisms involved in these behaviours.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants, aged 13–16 years, were recruited from a study called Preventure (for details on the recruitment strategy used, see Conrod et al. 2008, 2010; Castellanos and Conrod 2006). In brief, participants were recruited from secondary schools in London. Participants were asked to complete a questionnaire during class time, which included measures on personality, alcohol and substance use, reckless and antisocial behaviour. The Preventure sample was created (N = 787) by selecting those students who scored high (1 standard deviation above the mean) in at least one of four personality risk profiles (hopelessness, anxiety sensitivity, impulsivity and sensation seeking—based on the Substance Use Risk Profile Scale—see below for details), and a random normative group of students, who scored low (below 1 standard deviation above the mean) on all personality risk subscales. As part of the Preventure study, participants were randomly assigned to either a CBT intervention condition group (n = 395) or a non-intervention control group (n = 392), and were then followed up twice a year, for 2 years. For the most part, analyses in this article included data from the first three time points only: baseline, 6 months and 12 months follow up. However, three measures assessed at 24 months follow up, when adolescents were 16 years on average, were included (drinking problems, conduct problems and drinking quantity by frequency) for clinical validity purposes (see “Measures and Results” section). Also, as previous research has shown that the Preventure personality-matched CBT interventions were effective in reducing substance misuse and some aspects of antisocial behaviour at 6 months post-intervention (Castellanos and Conrod 2006; Conrod et al. 2008), analyses focused only on participants who did not receive an intervention as part of the Preventure study (N = 392).

Participants in the sample included in this study (N = 392) were initially assessed at age 13–15 years (mean age of 14.03), while attending year 9 (53%) or 10 (47%) at secondary school. They came from a variety of ethnic backgrounds (37% white British/ other, 12% south Asian, 32% Black, 19% other or mixed), and more than half were girls (67%).

Measures

Data was gathered through self-reports, mostly in group assessments with self-administered questionnaires. All measures were administered at baseline, 6 month and 12 month follow-up assessments, which included:

Demographics

This questionnaire is based on a questionnaire compiled by Stewart and Devine (2000). Participants are asked to provide their age, gender, current grade level in school, and their ethnicity according to a forced-choice answering procedure.

Personality Traits

Personality traits were assessed with the Substance Use Risk Profile Scale (SURPS), which is a 23 item questionnaire which assesses several personality risk factors for substance abuse/dependence including hopelessness (H), anxiety sensitivity (AS), impulsivity (IMP) and sensation seeking (SS; Woicik et al. 2009). In the present sample, each of the subscales appeared to have good internal reliability for short scales (α = 0.77 for H (seven items), α = 0.67 for AS (five items), α = 0.67 for IMP (five items), and α = 0.69 for SS (six items)), and good 6 month test-retest reliability (as measured by intra-class correlations between baseline and T2 scores; 0.74 for H, 0.72 for AS, 0.69 for IMP, and 0.68 for SS). Several studies have shown that the SURPS possesses good psychometric properties—internal reliability, convergent and discriminant validity, as well as 2-month test-retest reliability—when used in adult and adolescent samples (Krank et al. 2011; Woicik et al. 2009). However, because one of the SS items (“I am interested in experience for its own sake, even if it is illegal”) has been shown to cross-load on to the impulsivity factor in a factor analyses of the SURPS carried out in this sample (Castellanos 2009) and a young adolescent Canadian sample (Krank et al. 2011), a revised SS score was used for the analyses in this study, which did not include this item.

Substance Misuse (SM) Symptoms

Binge Drinking Frequency

Binge drinking was determined by asking adolescents to report how often (i.e. never, less than monthly, monthly, weekly or daily) they consumed five or more alcoholic beverages (more than four for girls) on one occasion in the past 6 months.

Drug Use Frequency

Drug use frequency was determined by asking students at each time point to report how many times (i.e. never, 1time, 2–5 times, 6–10 times or more than ten times) they used marijuana, cocaine or other drugs in the past 6 months. These drug use items were taken from the Reckless Behaviour Questionnaire (RBQ, Shaw et al. 1992), which is a ten item measure that asked participants to report how often (scale ranged from none to more than ten times) they engaged in risky behaviour in the past 6 months. The RBQ includes items on drug-taking, speeding, risky sexual behaviour and antisocial behaviour (see section below on vandalism and shoplifting).

Conduct Disorder (CD) Symptoms

Vandalism and Shoplifting

Vandalism and shoplifting were assessed by asking participants to report how often (scale ranged from none to more than ten times) they engaged in these behaviours in the past 6 months. The question assessing vandal-type behaviour was phrased “how many times in the last 6 months have you damaged or destroyed public or private property”, and the one assessing shoplifting was “how many times in the last 6 months have you shoplifted”. Both these items were taken from the Reckless Behaviour Questionnaire (Shaw et al. 1992).

Bullying and Aggressive Behaviour

Bullying and aggressive behaviour was assessed by asking participants: “how many times have you been involved in bullying another in the last 6 months” and “how many times have you been involved in a physical fight in the last 6 months?” Participants had to report how often they engaged in bullying by selecting from options on a likert-type scale ranging from none (1) to several times a week (5). They reported how often they engaged in physical fighting by selecting options on a scale ranging from none (1) to four times or more (5). These item are derived from a questionnaire used in a large international study entitled Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), and are originally taken from the revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire (Olweus 1996), and the Youth Risky Behaviour Survey (Brener et al. 1995).

Truancy

The last item used to assess CD symptoms was an item referring to how many days—ranging from none to seven or more—participants “had missed school without permission in the last 6 months”. This item was placed in the demographic section of the questionnaire following a question on how many days they had missed school because of illness.

Measures at 24 Month Follow-up

Three further measures of externalising behaviours were included in analyses only for the purposes of providing clinical validity to the latent factors obtained through the structural modelling of the data. These measures were:

Conduct problems was assessed using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ, Goodman et al. 1998), which is an internationally validated measure for adolescents aged 11–16 assessing emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and pro social behaviour. The SDQ is made up of five subscales and a total of 25 items (five items per subscale), which can be marked as “not true” (scored as 0), “somewhat true” (scored as 1) and “certainly true” (scored as 2). Scores for the conduct problems subscale, which can range from 0 to 10, was calculated by summing the score of the relevant five subscale items. This SDQ subscale has good internal reliability, with a reported Crombach’s alpha coefficient of 0.72 (Goodman et al. 1998).

Alcohol problems were assessed using the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI, White and Labouvie 1989), which is a 23-item self-report measure that assesses symptoms of adolescent problem drinking. Respondents are required to indicate on a five point scale (1 = never, to 5 = more than six times) how many times they have experienced negative consequences due to their alcohol use in the past 6 months. Responses were summed across the 23 items to yield a composite score.

Drinking quantity by frequency was determined by asking adolescents to report how often they drank (i.e. never, less than monthly, monthly, weekly or daily) and how many drinks containing alcohol they had on a typical day when they were drinking (ranging from none to 10 or more). These two variables were multiplied to create a composite drinking quantity by frequency score.

Missing Data

Retention rates were 82% for the 6-month follow up and 76% for the 12-month follow up. A logistic regression revealed that demographic variables or personality scores were not significant predictors of missing outcome data, except for gender, Wald’s X 2 (1, N = 392) = 6.61, p < 0.05, showing that there was more missing data for boys than for girls. However, results did not show an interaction between gender and behavioural symptoms. Given these results, we relied on full information maximum likelihood estimation under the assumption of data missing at random (MAR) for all continuous variables (using SPSS v.15).

Statistical Analysis

First, in order to clarify the nature of the association between SM and CD symptoms in this sample of young adolescents, several structural equation models of the SM and CD symptom measures were analysed using AMOS 7 (Arbuckle 2006). As a way to investigate the nature of comorbidity between these sets of symptoms, three different models based on the work by Krueger et al. (2007) were fitted: a one-factor model, a higher order two sub-factors model, and a general-specific factor model (referred to as a hierarchical model in Krueger et al’s paper; see below for description). For model estimation, maximum likelihood was used on log-transformed variables. Although most observed variables entered in to the models were ordinal in nature, once log-transformed, all variables approached normality and had acceptable levels of skewness and kurtosis for the use of maximum likelihood estimation (lower than 2 and 7, respectively; Curran et al. 1996). Furthermore, all ordinal variables had five categories. Several studies have shown that when the number of categories is large (e.g. equal or higher than four) in ordinal variables and they are normally distributed, continuous methods like maximum likelihood estimation can be used (Bentler and Chou 1987; Muthén and Kaplan 1985). Tests of goodness of fit included the CFI (Bentler 1990), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation, RMSEA (Browne and Cudeck 1993) and its corresponding p of close fit (PCLOSE). Traditionally, CFI >0.90, RMSEA <=0.05, and PCLOSE ≥0.05, are considered as indicative of a good fit. Models were compared using Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), frequently used to compare non-nested models. Smaller values on both these measures indicate the model that best balances fit and parsimony. Once the best fitting model of “comorbidity” was established, measures of personality were entered as predictors in the model, in order to establish whether personality measures were common to or uniquely associated with externalising behaviour, CD and SM symptoms.

Results

Structural Equation Models Assessing the Comorbidity Between Conduct Disorder and Substance Misuse Symptoms

A series of structural equation models were carried out to assess the nature of SM and CD symptoms and their comorbidity in this adolescent sample. These models included all the log-transformed symptom variables across three time points: frequency measures of truancy, vandalism, shoplifting, bullying, physical fighting, binge drinking, and composite drug use (marijuana, cocaine and other drug use frequency were combined in to a composite score because of low variability on cocaine and other drug use measures). First-order latent variables were modelled for each of the behaviours using indicator variables at each time point, i.e. T1 vandalism frequency, T2 vandalism frequency and T3 vandalism frequency served as indicators for the latent variable of vandalism. As is typical in structural models using longitudinal data, error variances for each measure were allowed to covary within time points (see Hoyle and Smith 1994), but not within each measure.

As mentioned, three different “comorbidity” models based on models assessed in an adult sample by Krueger et al. (2007), were evaluated: a one-factor model (assessing whether all symptom variables explain one externalising behaviour construct), a higher order two subfactors model (assessing whether all symptoms explain one single coherent construct (externalising behaviour) that then can be subdivided in two lower order CD and SM factors), and a general-specific factor model (assessing whether symptom variables explain an externalising behaviour construct, but also CD and SM constructs which are independent from the externalising behaviour construct). In the first, one-factor model, a single second-order “externalising behaviour” factor was modelled as having loadings on all first-order symptom subscales (truancy, vandalism, shoplifting, bullying and fighting, binge drinking and drug use frequency). Although related, the following two models, the higher order model and general-specific factor model, represent two empirically and conceptually distinct accounts of the relationship between factors in a multilevel factor model (Krueger et al. 2007). A sample of the higher order and general-specific models are portrayed in Fig. 1a and b, respectively. Both models involve seven latent variables for each symptom score, and three factors, but the higher order model conceptualizes a domain in terms of a general factor (externalising behaviour) that diverges into two distinct factors (CD and SM symptoms). In this model the correlations between latent symptom variables are accounted for by the two higher order factors (CD and SM) and the correlation between these two factors is accounted for by the general externalising behaviour factor. If this model provides superior fit to the data, it indicates that the domain or data being modelled consists of a single broad, coherent construct which can be subdivided into increasingly specific factors. The general-specific factor model, on the other hand, although it still includes an overarching “externalising behaviour” factor, symptom variables are saturated with both this “externalising behaviour” variable and the other more specific “CD symptoms” and “SM” factors. If this model provides the best fit to the data, it indicates that the symptom variables explain a single broad, coherent construct but that specific symptom variables also explain other, more specific factors (SM and CD symptoms) that vary independently from the general factor.

For all three models, variances of second-order latent variables (i.e. externalising behaviour factor in the first model) were constrained to 1, which permitted the path coefficients from the second-order latent factors to the first-order latent symptom variables (i.e. drug use) to be freely estimated. The one factor model fit the data acceptably (X2 = 276.36, df = 119, p = 0.00, X2/df = 2.32, CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.06, pclose = 0.06, AIC = 500.36, BIC = 945.14), with results showing that all path loadings from the externalising behaviour factor to all symptoms variables were significant (all p < 0.001) and ranged from 0.55 (for bullying) to 0.81 (for vandalism).

As additional constraints were required for identification of the higher order and general-specific factor models, critical ratios for difference were requested when this first one-factor model was estimated. Critical ratios for difference allow appropriate parameter candidates for the imposition of equality constraints to be identified (Byrne 2001). Results identified two candidates for the imposition of equality constraints, with the estimated values for the residual errors for vandalism and drug use being almost identical (variances equalled 0.0021 and 0.0020 and critical ratios equalled 5.23 and 5.65, respectively). The critical ratio of difference for these residual errors confirmed that there was no significant difference between these values as it was below 1.96 (i.e. 0.18) and thus were constrained to be equal in the following two models.

Model fit statistics for the one-factor (once the equality constraint for residuals of drug use and vandalism was imposed), higher order two-subfactor, and hierarchical two-subfactor models are given in Table 1. As shown in the table, according to all fit criteria, the best fitting model was the general-specific factor model (i.e. CFI and PClose was highest, and X2/df, RMSEA were all lowest for this model), suggesting that although the different variables explain a single general externalising behaviour factor well (capturing the shared variance of all CD and SM symptoms), specific variables also measure the independently varying SM and CD latent variables well (capturing the specific variance of SM and CD symptoms, respectively).

Standardized model parameter estimates for the general-specific factor model are presented in Table 2. The largest loadings for the externalising behaviour factor were on vandalism, shoplifting, drug use and physical fighting variables, while the largest loadings for the CD and SM subfactors were on vandalism and drug use, respectively. Indeed, for the CD factor, even though the loadings for vandalism, shoplifting and bullying were significant, the loadings were small for shoplifting and bullying. Thus it is important to note that the CD factor is really for the most part representing vandalism.

In an attempt to provide further clinical validity for these latent constructs, three measures of externalising problems assessed when adolescents were an average of 16 years (at 24 month follow up), were entered in to the model as outcomes, with the latent factors for EXT, CD and SM as predictors. The three new measures entered were conduct problems, as measures by the SDQ, alcohol problems, as measured by the RAPI, and a measure of drinking quantity by frequency. This model fit the data well, X2 = 315.68, df = 171, p = 0.00, X2/df = 1.85, CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.05, pclose = 0.44, and showed that while the EXT factor significantly predicted all outcomes a year later (SDQ conduct problems, 0.36, alcohol problems, 0.66, drinking QxF, 0.56, all at p < 0.001), the CD factor significantly predicted conduct problems (0.19, p = 0.002), marginally predicted drinking problems (0.13, p = 0.045), but did not predict drinking QxF (0.06, p = 0.319). Finally, the SM factor significantly predicted drinking problems (0.38, p < 0.001) and drinking QxF (0.73, p < 0.001), but not conduct problems (0.08, p = 0.234) a year later. Although not comprehensive, these associations provide some validity to these latent constructs, especially to those capturing unique variance of CD and SM, suggesting that the SM factor is associated mainly with a more normative, less severe form of substance misuse that does not co-occur with other externalising problems, while the CD factor is associated with conduct problems that do not, or only marginally co-occur with substance use problems.

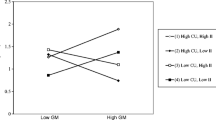

Do Personality Traits Explain the Common and/or Unique Variance Between Conduct Disorder and Substance Misuse Symptoms?

In order to establish how personality measures were associated with externalising behaviour, CD and SM severity, impulsivity, sensation seeking, hopelessness and anxiety sensitivity variables were included as predictors in the general-specific factor model described above (see Fig. 2). This model fit the data well, X2 = 354.24, df = 186, p = 0.00, X2/df = 1.91, CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.05, pclose = 0.65.

Regression coefficients from personality measures to behavioural constructs showed that impulsivity was significantly associated with the externalising behaviour (0.34, p < 0.001) and the CD (0.19, p < 0.05) constructs, but not the SM construct (0.01, p = 0.93). Inversely, sensation seeking was significantly associated with the SM construct (0.29, p < 0.05), but not the externalising behaviour (0.11, p = 0.10) or CD (0.07, p = 0.40) constructs. Hopelessness was significantly associated with externalising behaviour (0.27, p < 0.001), but not the CD (−0.05, p = 0.59) or SM (0.08, p = 0.34) factors. Anxiety sensitivity was negatively associated with the CD factor (−0.18, p < 0.05), but was not associated with the SM (−0.03, p = 0.72) or externalising behaviour (−0.11, p = 0.09) factors.

Discussion

The first aim of this study was to examine the nature of the relationship between substance misuse and conduct disorder symptoms in adolescence, by testing several models of comorbidity. Structural equation models confirmed that there are both common and specific components of substance misuse and conduct disorder symptoms. Results showed that a general-specific model of comorbidity provided the best fit to the data, which indicated that while substance misuse and conduct disorder symptoms explain a single broad, coherent construct of externalising behaviour, providing support for the externalising spectrum model, these symptoms also explained specific factors of substance misuse and conduct disorder symptoms that vary independently from the general externalising factor. In this sample, the symptoms that varied independently from the rest of the externalising behaviours, were vandalism for CD symptoms, and, mostly, drug use for substance use. Although the specific factor for conduct disorder differs from that modelled by Krueger et al. (2007), which captured more aggressive behaviours rather than vandalism or destructive behaviours, these results are consistent with their findings. Both studies show that externalising symptoms are organised hierarchically, explaining one general and coherent externalising factor, as well as two sub-factors that vary independently from the externalising factor. Because of the different measures used, developmental periods studied, and sample characteristics (Krueger et al. assessed externalising behaviours in young adults recruited from College as well as state prisons), differences in results from those reported by Krueger et al. (2007) were expected. Behaviours that served as indicators for the CD factors in both studies might reflect the more severe end of the continuum for antisocial symptoms at the particular developmental stages studied. So, while Krueger’s model appears to suggest that aggression might be the most extreme manifestation of antisocial symptoms within that sample, it is vandalism, shoplifting and bullying that are the most extreme manifestations of antisocial tendencies in the current sample. This hypothesis is partly supported by our data, which shows that vandalism, shoplifting and bullying were less prevalent than truancy and fighting, and although having acceptable levels of skewness for ML estimation, were the most skewed of the CD indicators. Although indicators for the specific factors differ, both studies suggest that diverse externalising problem behaviours may share a common set of underlying causes, but also have specific underlying causes that are important determinants of involvement in these behaviours.

The second aim of this study was to examine whether two facets of disinhibition, impulsivity and sensation seeking, were associated specifically with substance misuse and/or conduct disorder symptoms, or generally with externalising behaviour, and thus with their comorbidity. Findings suggested impulsivity as a common underlying factor to externalising behaviours in general, by showing that impulsivity was robustly associated with the common variance shared among all externalising behaviours (as well as with unique variance of conduct disorder symptoms, i.e. once the variance accounted for by substance use was removed). Sensation seeking, on the other hand, was associated with the substance misuse factor only, identifying it as a specific underlying factor in the development of substance use. Results from the general-specific factor model confirmed that once the association between impulsivity and the common externalising behaviour construct was accounted for, its association with SM symptoms was no longer significant. These findings are consistent with research showing that while sensation seeking is specifically associated with drinking and substance use but not anti-social behaviours (e.g. Castellanos-Ryan et al. 2010; Smith et al. 2007), impulsive personality traits are robustly linked with a range of anti-social behaviour (Cooper et al. 2003; Krueger et al. 2002; Sher and Trull 1994; Tremblay et al. 1994), and suggest that the overlap between substance misuse and conduct disorder symptoms, and thus their comorbidity, is related to impulsivity. What is more, these effects are independent of those of inhibited personality traits, which have also been linked with externalising behaviours, especially those related to negative affect (e.g. Hicks, et al. 2004; Lynam et al. 2005). Indeed, results showed that while low levels of anxiety sensitivity were associated with the unique variance of conduct disorder symptoms, supporting previous findings showing that low levels of anxiety or fear are associated with antisocial behaviours (Fowles 1980; Walker, et al. 1991), high levels of hopelessness were associated with externalising behaviours in general. Thus, these finding also identify hopelessness as a common underlying factor for engaging in externalising behaviours in general, which is consistent with a previous finding by Cooper et al. (2003) showing that avoidance coping, which is correlated with hopelessness (O’Connor and O’Connor 2003), was associated with a general risk for involvement in a wide range of risky and problem behaviours in adolescence.

One of the strengths of this study is that the sample included both male and female adolescents from varied ethnic backgrounds, which would allow the resulting models of comorbidity and vulnerability to these problem behaviours to be applicable to a wide range of adolescents. Moreover, as mentioned in the introduction, adolescents were tested across a period of time which is considered a crucial developmental period and represents a limited window of time when the comorbidity between substance misuse and conduct disorder symptoms, as well as vulnerability to both these disorders, can truly be examined before the effects of chronic substance misuse have their impact and have reciprocal effects on personality and behaviour. Establishing risk factors in adolescents is particularly important not only because adolescent substance use is associated with risky sexual behaviour, injuries and other negative consequences in adolescence, but also because it strongly predicts substance misuse disorders and other social and mental health issues in adulthood (e.g. Grant and Dawson 1998; Odgers et al. 2008). Thus, targeted prevention and intervention efforts during adolescence may have beneficial effects that endure into later life.

Conversely, it is important to note a number of limitations to this study. First, personality traits were assessed with the Substance Use Risk profile scale only, which is not a widely known personality measure, and does not allow a broader range of related traits to be assessed. In particular, it does not allow a number of other disinhibited traits identified, for example, by Smith et al. (2007) and Whiteside and Lynam (2001) to be assessed, that could possibly have also been able to explain some of the unique and common variance shared by the behaviours studied. Second, all data were gathered through self-report, which is susceptible to bias and may limit the experimental validity of the data. Although using self-reports is common and considered reliable when assessing substance misuse (Clark and Winters 2002), a number of researchers believe that assessing conduct disorder symptoms through self-report is not. These researchers believe that, as lying is considered a symptom of conduct disorder, these youths will not answer questions truthfully (e.g. Brown et al. 1996). Still, several studies have found that adolescent self-reports of both conduct disorder and substance use disorder symptoms have excellent discriminant validity (Crowley et al. 2001) and predictive validity (Crowley et al. 1998), and hence are useful for treatment and research. This, together with guaranteed confidentiality to participants, should contribute to the reliability of these data. Future studies may more fully address this limitation by using parent/teacher ratings of behaviour, as well as clinician semi-structured interviews.

Overall, it is clear from the results in this study that personality traits, especially impulsivity and hopelessness, play an important role in the onset and maintenance of substance misuse and antisocial behaviour in adolescence, and therefore should be a clear target for intervention and/or prevention strategies. Most prevention strategies target behaviours directly, like drinking and drug use, but findings from this and other studies (e.g. Conrod et al. 2000, 2006, 2010; Smith et al. 2007) seem to indicate that interventions would logically want to target liability factors rather than behaviour. Prevention and treatment models that target liability, like a tendency to impulsivity or negative affect, rather than behaviour are relevant to those engaging in different kinds of externalising behaviours. Furthermore, findings showing that sensation seeking was associated with unique variance in substance misuse symptoms suggest that there are individuals prone to substance misuse for reasons other than impulsivity or negative affect. Therefore, prevention and interventions for substance misuse should target sensation seeking aspects of personality. In this vein, it is clear that a personality-targeted approach in the prevention or early intervention of substance misuse and conduct disorder, which focuses on specific personality risk factors and differential motivations for engaging in these behaviours will improve current efforts in tackling both these disorders so prevalent in adolescence.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. S. (1978). The classification of child psychopathology: a review and analysis of empirical efforts. Psychological Bulletin, 85, 1275–1301.

Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. S. (1984). Psychopathology of childhood. Annual Review of Psychology, 35, 227–256.

Agrawal, A., Neale, M. C., Prescott, C. A., & Kendler, K. S. (2004). A twin study of early cannabis use and subsequent use and abuse/dependence of other illicit drugs. Psychological Medicine, 34, 1227–1237.

Arbuckle, J. L. (2006). AMOS Version 7. Chicago: Smallwaters.

Armstrong, T. D., & Costello, E. J. (2002). Community studies on adolescent substance use, abuse, or dependence and psychiatric comorbidity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 1224–1239.

Arnett, J. (1994). Sensation seeking: a new conceptualization and a new scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 16, 289–296.

Barlow, D. H. (2000). Unravelling the mysteries of anxiety and its disorders from the perspective of emotion theory. American Psychologist, 55, 1247–1263.

Baumeister, R. F., & Vohs, K. D. (2004). Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications. New York: The Guilford.

Belin, D., Mar, A. C., Dalley, J. W., Robbins, T. W., & Everitt, B. J. (2008). High impulsivity predicts the switch to compulsive cocaine-taking. Science, 320, 1352–1355.

Benning, S. D., Patrick, C. J., Hicks, B. M., Blonigen, D. M., & Krueger, R. F. (2003). Factor structure of the psychopathic personality inventory: validity and implications for clinical assessment. Psychological Assessment, 15, 340–350.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246.

Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C.-P. (1987). Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research, 16(1), 78–117.

Brener, N., Collins, J., Kann, L., Warren, C., & Williams, B. (1995). Reliability of the youth risk behavior survey questionnaire. American Journal of Epidemiology, 141, 575–580.

Brook, J. S., Richter, L., & Rubenston, E. (2000). Consequences of adolescent drug use on psychiatric disorders in early adulthood. Annals of Medicine, 32, 401–407.

Brown, K., Atkins, M. S., Osbome, M. L., & Milnamow, M. (1996). A revised teacher rating scale for reactive and proactive aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 24, 473–480.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation modeling (pp. 136–162). CA: Sage.

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Cantrell, H., Finn, P. R., Rickert, M. E., & Lucas, J. (2008). Decision making in alcohol dependence: Insensitivity to future consequences and comorbid disinhibitory psychopathology. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 32, 1398–1407.

Caspi, A., Begg, D., Dickson, N., Harrington, H., Langley, J., Moffitt, T. E., et al. (1997). Personality differences predict health-risk behaviors in young adulthood: evidence from a longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 1052–1063.

Castellanos, N. (2009). Substance misuse and conduct disorder in adolescence: the role of disinhibition in the onset of behavioural problems and their comorbidity. (Doctoral dissertation, King’s College London, 2009).

Castellanos, N., & Conrod, P. J. (2006). Brief interventions targeting personality risk factors for adolescent substance misuse reduce depression, panic and risk taking behaviours. Journal of Mental Health, 15, 645–658.

Castellanos-Ryan, N., Rubia, K., & Conrod, P. J. (2010). Response inhibition and reward response bias mediate the predictive relationships between impulsivity and sensation seeking and common and unique variance in conduct disorder and substance misuse. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 35, 140–155.

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1991). Tripartate model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 316–336.

Clark, D. B., & Winters, K. C. (2002). Measuring risks and outcomes in substance use disorders prevention research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 1207–1223.

Comeau, M. N., Stewart, S. H., & Loba, P. (2001). The relations of trait anxiety, anxiety sensitivity, and sensation seeking to adolescents’ motivations for alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use. Addictive Behaviors, 26, 803–825.

Conrod, P. J., & Stewart, S. H. (2005). A critical look at dual-focused cognitive-behavioural treatments for comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders: strengths, limitations, and future directions. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 19, 261–284.

Conrod, P. J., Pihl, R. O., Stewart, S. H., & Dongier, M. (2000). Validation of a system of classifying female substance abusers on the basis of personality and motivational risk factors for substance abuse. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 14, 243–256.

Conrod, P. J., Stewart, S. H., Comeau, N., & Maclean, A. M. (2006). Preventative efficacy of cognitive behavioral strategies matched to the motivational bases of alcohol misuse in at-risk youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35, 550–563.

Conrod, P. J., Castellanos, N., & Mackie, C. (2008). Personality-targeted interventions delay the growth of adolescent drinking and binge drinking. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 181–190.

Conrod, P. J., Castellanos-Ryan, N., & Strang, J. (2010). Brief, personality-targeted coping skills interventions prolong survival as a non-drug user over a two-year period during adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67, 85–93.

Cooper, M. L., Wood, P. K., Orcutt, H. K., & Albino, A. (2003). Personality and the predisposition to engage in risky or problem behaviours during adolescence. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 84, 390–410.

Costello, E. J., Mustillo, S., Erkanli, A., Keeler, G., & Angold, A. (2003). Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 837–844.

Crowley, T. J., Mikulich, S. K., Macdonald, M., Young, S. E., & Zerbe, G. O. (1998). Substance-dependent, conduct-disordered adolescent males: severity of diagnosis predicts 2-year outcome. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 40, 225–237.

Crowley, T. J., Mikulich, S. K., Ehlers, K. M., Whitmore, A. E., & Macdonald, M. J. (2001). Validity of structured clinical evaluations in adolescents with conduct and substance problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 265–273.

Curran, P. J., West, S. G., & Finch, J. F. (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1, 16–29.

D’Amico, E. J., & McCarthy, D. M. (2006). Escalation and initiation of younger adolescents’ substance use: the impact of perceived peer use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39, 481–487.

Dawe, S., & Loxton, N. J. (2004). The role of impulsivity in the development of substance use and eating disorders. Neuroscience and Biobehavioural Reviews, 28, 343–351.

de Win, M. M., Reneman, L., Jager, G., Vlieger, E. J., Olabarriaga, S. D., Lavini, C., et al. (2007). A prospective cohort study on sustained effects of low-dose ecstasy use on the brain in new ecstasy users. Neuropsychopharmacology, 32, 458–470.

de Wit, H., & Richards, J. B. (2004). Dual determinants of drug use in humans: Reward and Impulsivity. In R. A. Bevins & M. T. Bardo (Eds.), Motivational factors in the etiology of drug abuse (pp. 19–55). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Eisenberg, N., Guthrie, I. K., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S., Losoya, S., Murphy, B. C., et al. (2000). Prediction of elementary school children’s externalizing problem behaviors from attentional and behavioral regulation and negative emotionality. Child Development, 71, 1367–1382.

Eisenberg, N., Cumberland, A., Spinrad, T. L., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S., Reiser, M., et al. (2001). The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development, 72, 1112–1134.

Ersche, K. D., Clark, L., London, M., Robbins, T. W., & Sahakian, B. J. (2006). Profile of executive and memory function associated with amphetamine and opiate dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology, 31, 1036–1047.

Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, S. B. G. (1992). Manual of the EPQ-R and the impulsiveness, venturesomeness and empathy scales. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Eysenck, B. G., Pearson, P. R., Easting, G., & Allsop, J. F. (1985). Age norms for impulsiveness, venturesomeness and empathy in adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 6, 613–619.

Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., & Lynskey, M. T. (1993). Prevalence and comorbidity of DSM-III_R diagnoses in a birth cohort of 15 year olds. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 32, 1127–1134.

Finn, P. R., Sharkansky, E. J., Brandt, K. M., & Turcotte, N. (2000). The effects of familial risk, personality, and expectancies on alcohol use and abuse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 122–133.

Finn, P. R., Mazas, C., Justus, A., & Steinmetz, J. E. (2002). Early-onset alcoholism with conduct disorder: go/no-go learning deficits, working memory capacity, and personality. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 26, 186–206.

Fowles, D. C. (1980). The three arousal model: implications of gray’s two-factor learning theory for heart rate, electrodermal activity, and psychopathy. Psychophysiology, 17, 87–104.

Frick, P. J., & Morris, A. S. (2004). Temperament and developmental pathways to conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 54–68.

Goodman, R., Meltzer, H., & Bailey, V. (1998). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 17, 125–130.

Grant, B. F., & Dawson, D. A. (1998). Age at onset of drug use and its association with DSM–IV drug abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse, 10, 163–173.

Grant, J. D., Scherrer, J. F., Lynskey, M. T., Lyons, M. J., Eisen, S. A., Tsuang, M. T., et al. (2006). Adolescent alcohol use is a risk factor for adult alcohol and drug dependence: evidence from a twin design. Psychological Medicine, 36, 109–118.

Hicks, B. M., Markon, K. E., Patrick, C. J., Krueger, R. F., & Newman, J. P. (2004). Identifying psychopathic subtypes on the basis of personality structure. Psychological Assessment, 165, 276–288.

Hicks, B. M., Bernat, E., Malone, S. M., Iacono, W. G., Patrick, C. J., Krueger, R. F., et al. (2007). Genes mediate the association between P3 amplitude and externalising disorders. Psychophysiology, 44, 98–105.

Hoyle, R. H., & Smith, G. T. (1994). Formulating clinical research hypotheses as structural equation models: a conceptual overview. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 429–440.

Jang, K. L., Vernon, P. A., & Livesley, W. J. (2000). Personality disorder traits, family environment, and alcohol misuse: a multivariate behavioural genetic analysis. Addiction, 95, 873–888.

Johnson, E. O., Arria, A. M., Borges, G., Ialongo, N., & Anthony, J. C. (1995). The growth of conduct problem behaviors from middle childhood to early adolescence: sex differences and the suspected influence of early alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 56, 661–671.

Kahn, A. M., Jacobson, K. C., Gardner, C. O., Prescott, C. A., & Kendler, K. S. (2005). Personality and comorbidity of common psychiatric disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry, 186, 190–196.

Kendler, K. S., Prescott, C. A., Myers, J., & Neale, M. C. (2003). The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 929–937.

Kendler, K. S., Myers, J., & Prescott, C. A. (2007). Specificity of genetic and environmental risk factors for symptoms of cannabis, cocaine, alcohol, caffeine, and nicotine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 1313–1320.

Klein, D. N., & Riso, L. P. (1993). Psychiatric disorders: Problems of boundaries and comorbidity. In C. G. Costello (Ed.), Basic issues in psychopathology (pp. 19–66). New York: The Guilford.

Krank, M., Stewart, S. H., O’Connor, R., Woicik, P., Wall, A. M., & Conrod, P. J. (2011). Structural, concurrent and predictive validity of the Substance Use Risk Profile Scale in early adolescence. Addictive Behaviours, 36, 37–46.

Krueger, R. F. (1999). The structure of common mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 921–926.

Krueger, R. F., & Markon, K. E. (2006). Reinterpreting comorbidity: a model-based approach to understanding and classifying psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 2, 111–133.

Krueger, R. F., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., & Silva, P. A. (1998). The structure and stability of common mental disorders (DSM–III–R): a longitudinal-epidemiological study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107, 216–227.

Krueger, R. F., Hicks, B. M., Patrick, C. J., Carlson, S. R., Iacono, W. G., & McGue, M. (2002). Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior, and personality: modeling the externalising spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111, 411–424.

Krueger, R. F., Markon, K. E., Patrick, C. J., Benning, S. D., & Kramer, M. D. (2007). Linking antisocial behaviour, substance misuse, and personality: an integrative quantitative model of the adult externalising spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116, 645–666.

Kwapil, T. R. (1996). A longitudinal study of drug and alcohol use by psychosis-prone and impulsive-nonconforming individuals. Journal of Abnormal Psychiatry, 105, 114–123.

Lane, S., Cherek, D. R., Rhodes, H. M., Pietras, C. J., & Techeremissine, O. V. (2003). Relationships among laboratory and psychometric measures of impulsivity: implications in substance abuse and dependence. Addictive Disorders & Their Treatment, 2, 33–40.

Lynam, D. R., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Raine, A., Lober, R., & Stouthoemer-Loeber, M. (2005). Adolescent psychopathy and the big five: results from two samples. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 431–443.

Mackie, C., Castellanos-Ryan, N., & Conrod, P. J. (in press). Personality moderates the longitudinal relationship between psychological symptoms and alcohol use in adolescents. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research.

Masse, L. C., & Tremblay, R. E. (1997). Behavior of boys in kindergarten and the onset of substance use during adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54, 62–68.

McGue, M., Iacono, W. G., & Krueger, R. (2006). The association of early adolescent problem behaviour and adult psychopathology: a multivariate behavioral genetic perspective. Behavior Genetics, 36, 591–602.

Mustanski, B. S., Viken, R. J., Kapprio, J., & Rose, R. J. (2003). Genetic influences on the association between personality risk factors and alcohol use and abuse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 282–289.

Muthén, B., & Kaplan, D. (1985). A comparison of some methodologies for the factor analysis of non-normal Likert variables. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 38, 171–189.

Neale, M. C., & Kendler, K. S. (1995). Models of comorbidity for multifactorial disorders. American Journal of Human Genetics, 57, 935–953.

O’Connor, R. C., & O’Connor, D. C. (2003). Predicting hopelessness and psychological distress: the role of perfectionism and coping. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 50, 362–372.

Odgers, C. L., Caspi, A., Nagin, D., Piquero, A. R., Slutske, W. S., Milne, B., et al. (2008). Is it important to prevent early exposure to drugs and alcohol among adolescents? Psychological Science, 19, 1037–1044.

Olson, S. L., Schilling, E. M., & Bates, J. E. (1999). Measurement of impulsivity: construct coherence, longitudinal stability, and relationship with externalising problems in middle childhood and adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27, 151–165.

Olweus, D. (1996). Bully/victim problems at school: facts and effective intervention. National Education Service, 5, 15–22.

Pardini, D., Raskin White, H., & Stouthamer-Loeber, M. (2007). Early adolescent psychopathology as a predictor of alcohol use disorders by young adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88S, S38–S49.

Patrick, C. J. (2008). Psychophysiological correlates of aggression and violence: an integrative review. Philosophical Transaction of the Royal Society B, 363, 2543–2555.

Patton, J. H., Stanford, M. S., & Barratt, E. S. (1995). Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51, 768–774.

Patton, G. C., McMorris, B. J., Toumbourou, J. W., Hemphill, S. A., Donath, S., & Catalano, R. F. (2004). Puberty and onset of substance use and abuse. Pediatrics, 114, e300–e306.

Petry, N. M. (2002). Discounting of delayed rewards in substance abusers: relationship to antisocial personality disorder. Psychopharmacology, 162, 425–432.

Quilty, L. C., & Oakman, J. M. (2004). The assessment of behavioral activation—the relationship between impulsivity and behavioral activation. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 429–442.

Reynolds, B., Ortengren, A., Richards, J. B., & de Wit, H. (2006). Dimensions of impulsive behavior: personality and behavioural measures. Personality and Individual Differences, 40, 305–315.

Roberts, R. E., Roberts, C. R., & Xing, Y. (2007). Comorbidity of substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders among adolescents: evidence from an epidemiologic survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88S, S4–S13.

Schalling, D. (1978). Psychopathy-related personality variables and the psychophysiology of socialization. In R. D. Hare & D. Schalling (Eds.), Psychopathic behaviour: Approaches to research (pp. 85–105). New York: Wiley.

Shaw, D. S., Wagner, E. F., Arnett, J., & Aber, M. S. (1992). The factor structure of the reckless behavior questionnaire. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 21, 305–323.

Sher, K. J., & Trull, T. J. (1994). Personality and disinhibited psychopathology: alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103, 92–102.

Simons, J. S., Gaher, R. M., Correlia, C. J., Hansen, C. L., & Christopher, M. S. (2005). An affective-motivational model of marijuana and alcohol problems among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviours, 19, 326–334.

Slutske, W. S., Heath, A. C., Dinwiddie, S. H., Madden, P. A. F., Bucholz, K. K., Dunne, M. P., et al. (1998). Common genetic risk factors for conduct disorder and alcohol dependence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107, 363–374.

Slutske, W. S., Heath, A. C., Madden, P. A., Bucholz, K. K., Statham, D. J., & Martin, N. G. (2002). Personality and the genetic risk for alcohol dependence. Journal of Abnormal Psychological, 111, 124–133.

Smith, G. T., Fisher, S., Cyders, M. A., Annus, A. M., Spillane, N. S., & McCarthy, D. M. (2007). On the validity and utility of discriminating among impulsivity-like traits. Assessment, 14, 155–170.

Stewart, S. H., & Devine, H. (2000). Relations between personality and drinking motives in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 29, 495–511.

Stewart, S. H., Zvolensky, M. J., & Eifert, G. H. (2001). Negative-reinforcement drinking motives mediate the relation between anxiety sensitivity and increased drinking behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 31, 157–171.

Thombs, T. L. (2006). Introduction to addictive behaviors (3rd ed.). New York: The Guilford.

Tremblay, R. E., Pihl, R. O., Vitaro, F., & Dobkin, P. L. (1994). Predicting early onset of male antisocial behavior from preschool behavior. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51, 732–739.

Verdejo, A., Toribio, I., Orozco, C., Puente, K. L., & Perez-Garcia, M. (2005). Neuropsychological functioning in methadone maintenance patients versus abstinent heroin abusers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 78, 283–288.

Walker, J. L., Lahey, B. B., Russo, M. R., Frick, P. J., Christ, M. A. G., McBurnett, K., et al. (1991). Anxiety, inhibition, and conduct disorder in children: I. Relations to social impairment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30, 187–191.

Wells, S., Speechly, M., Koval, J. J., & Graham, K. (2007). Gender differences in the relationship between heavy episodic drinking, social roles, and alcohol related aggression in a U.S. sample of late adolescent and young adult drinkers. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 33, 21–29.

White, H. R., & Labouvie, E. W. (1989). Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 50, 30–37.

White, H. L., Xie, M., Thompson, W., Loeber, R., & Stouthamer-Loeber, M. (2001). Psychopathology as a predictor of adolescent drug use trajectories. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 15, 210–218.

Whiteside, S. P., & Lynam, D. R. (2001). The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 669–689.

Woicik, P., Stewart, S., Pihl, R. O., & Conrod, P. J. (2009). The substance use risk profile scale: a scale measuring traits linked to reinforcement-specific substance use profiles. Addictive Behaviours, 34, 1042–1055.

Young, S. E., Stallings, M. C., Corley, R. P., Krauter, K. S., & Hewitt, J. K. (2000). Genetic and environmental influences on behavioral disinhibition. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 96, 684–695.

Zimmermann, P., Wittchen, H., Hofler, M., Pfister, H., Kessler, R., & Lieb, R. (2003). Primary anxiety disorders and the development of subsequent alcohol use disorders: a 4-year community study of adolescents and young adults. Psychological Medicine, 33, 1211–1222.

Zuckerman, M. (1979). Sensation seeking: Beyond the optimal level of arousal. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Zuckerman, M., & Kuhlman, D. (2000). Personality and risk-taking: common biosocial factors. Journal of Personality, 68, 999–1029.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Castellanos-Ryan, N., Conrod, P.J. Personality Correlates of the Common and Unique Variance Across Conduct Disorder and Substance Misuse Symptoms in Adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol 39, 563–576 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9481-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9481-3