Abstract

Self-assessments by respondents in surveys are often the only available measure of tax evasion in developing countries at the microeconomic level. However, they suffer from the reluctance of respondents to reveal their own illicit behavior. This paper evaluates whether this weakness of self-assessments can at least partially be overcome through a novel questioning method, the crosswise model, which allows estimating the prevalence of tax evasion, but not identifying whether the individual respondent engages in tax evasion or not. Using evidence from Serbia, we show that crosswise model-based estimates of the share of firms which significantly underreport sales exceed those obtained from conventional methods by around 10 % points or more. With respect to wage underreporting to evade payroll tax and social security contributions, we do not find differences. These results appear to be robust to a number of modifications, and we explore various potential causes that lead to these results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

While tax evasion is commonly believed to be widespread in developing countries, exact measures of its extent are difficult to obtain because, by definition, tax evasion is hidden. Nevertheless, such estimates are often critical from a policy perspective, for instance to assess the payoffs of costly countervailing measures. One obvious and potentially timely source of information is surveys. However, it has long been recognized that respondents in such surveys have strong incentives to answer dishonestly questions about whether and to what extent they are tax compliant due to the threat of disclosure and the negative consequences that this may entail.Footnote 1 As a result, survey estimates are likely to understate the true extent of tax evasion. The objective of this paper is to assess whether a novel questioning method referred to as the crosswise model yields higher and arguably more realistic estimates of tax evasion compared to conventional questioning methods.

Assessing the extent of tax evasion can be seen as a broader trend in economics to find evidence of hidden or illicit behavior in a variety of settings; see Zitzewitz (2012) for a general survey. In the context of measuring the extent of tax evasion, there exist at least two other approaches at the microeconomic level that are summarized by Gemmell and Hasseldine (2012) and Alm (2012) in greater detail. The first approach is the use of intensive taxpayer audits as for instance in Joulfaian and Rider (1998) that may well be the most obvious strategy to gain information about the extent of tax evasion. However, they are costly and, as Slemrod and Weber (2012) suggest, there is no guarantee that such tax audits detect all unreported income, especially in an environment with a high presence of non-tax filers, strong reliance on cash in business transactions and dishonest or insufficiently monitored tax inspectors.

The second approach infers tax evasion of self-employed individuals by comparing them to wage earners who, by assumption, have fewer—if any—opportunities to underreport income. For instance, Feldman and Slemrod (2007) compare the correlations between charitable contributions and reported income for both groups. In order to study tax evasion of the self-employed, they assume that differences in this relationship across income types are solely due to underreporting; see Pissarides and Weber (1989) for a similar approach. However, the assumption of this strategy, namely that wage earners report income truthfully contrary to the self-employed who do not, is often violated in developing countries where firms are likely to evade payroll tax and social security contributions by underreporting wages as well.Footnote 2

While both approaches, namely intensive taxpayer audits and inference through comparing different types of taxpayers, are compelling from a conceptual perspective, they may not always be applied in a developing countries’ context.Footnote 3 The approach taken in this paper is therefore different. We use self-assessments of tax evasion by managers of firms, which are often the only measure of tax evasion readily available at the microeconomic level in developing countries. Contrary to previous papers, we employ a novel questioning strategy, referred to as the crosswise model (CM), in order to take into account the possibility that managers answer dishonestly in surveys. CM has been originally proposed by Yu et al. (2008) and has only been applied by Jann et al. (2012) to study plagiarism. It protects the privacy of the individual responses by “bundling” sensitive and non-sensitive questions so that the interviewer does not know whether a particular respondent shows the illicit or sensitive behavior in question. At the same time, CM still allows for estimating the prevalence of the sensitive behavior across the whole sample of respondents.

CM is part of a broader class of randomization methods that dates back to Warner (1965) to study sensitive topics such as drug use and sexual behavior (see Appendix and Tourangeau and Yan 2007, for a summary). Although this class of methods has been frequently applied in social sciences, there are only few applications in economics, which differ, however, in terms of focus, type of data used and methodology from our paper. Houston and Tran (2001), Himmelfarb and Lickteig (1982) and Musch et al. (2001) among others compare the performance of the random response technique (RRT), which is the most widely used method of this class, compared to the case when respondents are directly asked. Using data from surveys among households in developed countries, they all find that the RRT response rates and/or estimates of tax evasion are higher. However, in all cases, the survey was self-administered which makes it harder to monitor whether individuals followed the RRT procedure, which is quite complex. In addition, while Houston and Tran (2001) survey (taxpaying) individuals, the latter two papers survey students and random individuals that are self-selected for participation who may not actually have to pay taxes.Footnote 4

Randomization methods other than CM are increasingly used in surveys among firms in developing countries to study topics which are unrelated to tax evasion. Azfar and Murrell (2009), Clarke (2011, (2012a), Clausen et al. (2011) and Jensen and Rahman (2011) for instance apply various versions of these methods to identify respondents who give knowingly false answers to questions about corruption and firm performance. In addition, Karlan and Zinman (2012) examine self-reported information about the use of loan proceeds by clients of microfinance institutions.

The contribution of this paper is to assess the merits of the crosswise model to study tax evasion in business surveys relative to the conventional approach used to analyze sensitive issues including tax evasion in the World Bank Enterprise Surveys. Under the conventional method, respondents are asked to refer to firms similar to their own (“other people” approach), and the questions are framed in a forgiving way such that the sensitive behavior is to some extent implicitly justified in order to encourage truthful answers (forgiving wording); see Barton (1958). Contrary to related papers, we focus on self-assessments of the extent of tax evasion by managers of firms in developing countries which remit the bulk of revenue to tax authorities. In addition, we make use of CM which is by far best suited in our context, because it does not offer an obvious self-protective strategy which we explain below. Finally, we differentiate between two types of tax evasion that are both common in developing countries, namely underreporting of sales to evade consumption and/or profit taxes and “envelope wages” to evade payroll tax and/or social security contributions. Envelope wages imply that employers top up the official wages using undeclared cash payments. From a policy perspective and to design strategies to increase tax compliance, distinguishing between the modes of tax evasion is important.

Our data come from a recent survey of small and medium firms in Serbia, where estimates by Krstić et al. (2013) suggest that the shadow economy is relatively large by regional standards.Footnote 5 We randomly split the sample into two subsamples which are almost identical in terms of their industry–size–region distribution. For both subsamples, we estimate the extent of sales and wage underreporting, in one case using CM and in the other case using the “conventional” approach described above which consists of using the “other people” approach in combination with the use of forgiving wording. We show that estimates about the share of firms which significantly underreports sales obtained from CM exceed those obtained from conventional methods by 10 % points or more. With respect to envelope wages, the difference is smaller and statistically mostly not significant. These results are robust to a number of modifications, and we explore various potential causes that lead to these findings. We conclude that CM—through fully protecting the privacy of respondents—provides more reliable (though possibly still not fully realistic) information about sales underreporting and should be increasingly used in business surveys.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the mechanics of CM and its advantages. Section 3 presents the survey design. Section 4 describes the data. Section 5 presents the results. Section 6 concludes.

2 Crosswise model

In this paper, we use a recently proposed method to study tax evasion, namely the crosswise model (CM), which is very well suited to study tax evasion (Yu et al. 2008). The mechanics of CM are basically similar to those of the randomized response technique (RRT) (Warner 1965) which protects the privacy of the responses to sensitive questions and which has often been applied, mostly in other social sciences. We describe RRT and other related techniques in more detail in the Supplementary Material.

Under CM, respondents are simultaneously asked two questions: one about a sensitive characteristic/activity (e.g., tax evasion) denoted by X with an unknown distribution and one about a non-sensitive characteristic (e.g., last digit of your best friend’s mobile phone number) denoted by Y with a known distribution.Footnote 6 In the survey, respondents are only allowed to jointly answer both questions (i.e., they do not answer each question individually) and face only the following two options: (1) “no to both questions, or yes to both questions”, or (2) “yes to one of the questions, and no to the other one.”

This particular feature of the design is very attractive for two reasons. First, there is a high level of protection of the privacy of the respondent. Irrespective of the answer chosen, there is no certainty for the interviewer about whether or not the respondent engages in the sensitive activity. For example, assume that a respondent engages in the sensitive activity, but that he/she does not share the innocuous characteristic. In that case, the truthful answer would be option (2). However, with a truthful answer, a “yes” could either imply that the respondent engages in the sensitive behavior or that the respondent simply shares the innocuous characteristic. This implies that from the answer of the respondent, the interviewer cannot draw any conclusions with respect to the sensitive behavior; in addition, the interviewer does not have access to any other information telling him/her whether or not the respondent engages in the sensitive behavior and/or shares the innocuous characteristic.

Second, this type of bundling of answers also ensures that CM does not provide respondents with an obvious self-protective strategy which they may resort to if they distrust the questioning strategy or the interviewer. In other words, neither option (1) nor option (2) unambiguously negates both the non-sensitive question and the sensitive question. This is the central advantage of CM compared to other related methods including RRT. Obviously, another self-protective strategy, namely not answering at all, is still feasible, but as we show later, this strategy was not chosen in our survey. One reason may be the possibility that respondents may think that non-response could raise the suspicion that they engage in the sensitive behavior; in this sense, responding is a “safer” strategy in the context of CM.

With the sensitive characteristic and the non-sensitive characteristic, X and Y, respondents may be divided into four different subgroups depending on whether they share one of these characteristics, none or both. Table 1 assigns different probabilities to each subgroup.

The parameter q is essentially set by the researcher through asking an appropriate non-sensitive question about a characteristic with known distribution. With \(q=1\), CM (like RRT) becomes identical to directly asking the respondents about whether they share the sensitive behavior (see Warner 1965). By contrast, the prevalence of the sensitive characteristic \(\pi \) is the unknown parameter of interest. As shown by Yu et al. (2008), it may be estimated using maximum likelihood based on the empirical distribution of the answers (see Appendix for details).

The study by Jann et al. (2012), which compares the estimated prevalence of plagiarism under CM and “direct questioning” (DQ), is the only application of this approach so far. Under direct questioning, respondents are directly asked whether they engage in the sensitive behavior in question. The students participating in the survey were asked about past instances of partial and severe plagiarism in assignments such as seminar and term papers. With respect to the unrelated question, Jann et al. (2012) asked whether the month of birth of a close family member (i.e., father in one case and mother in another case) is January, February or March. Assuming that months of births are equally distributed, the prevalence of Y in this case would be 0.25. For partial plagiarism, CM yielded a significantly higher prevalence estimate than DQ, with a difference amounting to 15 % points (7.3 vs. 22.3 %). In case of severe plagiarism, the estimates remained low for both approaches (1.0 % for DQ and 1.6 % for CM), and the difference was insignificant. The results therefore suggest that enhanced anonymity of CM is at least in some cases important for the results.

Obviously, the general drawback of CM is that it does not allow examining the determinants of tax evasion and tax morale; see Torgler (2011) for a survey of this literature which relies to some extent on data from the World Values Survey and Dabla-Norris et al. (2008) for an example using data from the World Bank Enterprise Surveys. The reason is that CM only allows estimating the prevalence of tax evasion across the whole sample of respondents.

3 Hypothesis and survey design

We compare estimates of both sales underreporting and envelope wages obtained through CM to those obtained through a conventional questioning strategy without privacy protection which serves as our benchmark. We hypothesize that the prevalence of tax evasion estimated using information from business surveys is higher under the CM approach compared to our benchmark approach and that these differences arise due to differences in privacy protection.

Contrary to Jann et al. (2012), as a benchmark approach, we do not directly question respondents about tax evasion which has largely been discarded in the context of tax evasion and is likely to result in large biases. Instead, we choose the standard approach used to study illicit behavior including tax evasion in business surveys such as the World Bank Enterprise Surveys for instance, namely a combination of the “other people” approach and the use of forgiving wording. Under this approach, questions are framed in a way that justifies the sensitive behavior (forgiving wording) and/or asks respondents to refer to firms that are similar to theirs (“other people” approach). In the Supplementary Material, we report the exact question asked in the World Bank Enterprise Surveys. They are the most widely used source of standardized firm-level data from developing countries which is the reason why we choose this approach as our benchmark.

We expect that the respondents are likely to be aware that such an approach is imperfect and that the interviewer will make inferences about their own behavior based on their answers, which induces them to make false statements. This implies that estimates obtained from such an approach can be expected to be downward biased. Nevertheless, our benchmark approach is still more sophisticated than direct questioning which is used by Jann et al. (2012). This implies that our benchmark can be expected to yield higher estimates of the share of respondents showing the sensitive behavior and that the difference between the benchmark and CM estimates is smaller.

We distinguish two common modes of tax evasion, sales underreporting and envelope wages. Since CM only allows asking dichotomous questions, we estimate the share of firms that underreport at least 10 % of actual sales and wages, respectively. We chose the 10 % threshold because we consider underreporting above this threshold as significant from an economic point of view. Under the benchmark approach, the following question was asked to estimate the extent of sales underreporting (an analogous question was asked to estimate the extent of envelope wages):

Firms often struggle to meet all tax obligations which impose a significant burden on firms. According to your experience and judgment, do firms like this underreport at least annual 10 % of annual sales to STA for VAT and/or profit tax?Footnote 7

The respondents subject to the CM approach received an introduction to the crosswise model explaining that this questioning technique is designed to protect the privacy of their answers while acknowledging that this may seem strange to them. Interviewees are unlikely to understand the exact mechanism of inferring tax underreporting from the CM design; nevertheless, given the questions and the answer options, it does seem likely that they understand that the privacy of their particular answer is protected.

In the specific context of this survey, the non-sensitive characteristic used by Jann et al. (2012), namely the birth month of one parent, may be subject to the criticism that respondents do not know the birth months of the parents (e.g., if the respondent is an orphan or has been abandoned by one parent as a result of past armed conflicts in the region). Alternatively, respondents may be afraid that their parents’ month of birth can in principle be obtained by the interviewer through official records so that the privacy of the responses is no longer protected. In addition, we did not have access to statistics that could be used to estimate the distribution of birth months.

Therefore, contrary to Jann et al. (2012), we chose the last digit of the best friend’s mobile phone number as the non-sensitive characteristic and asked if it is “0 or 1” and “8 or 9”, respectively. Our assumption is that the distribution of the last digit of mobile phone numbers is uniform giving rise to \(q = 0.2\). Our results are robust to changes in the underlying distribution and in particular to higher prevalence rates which we discuss below, given that the allocation of mobile phone numbers by the operators is not known with certainty.

Nevertheless, we believe that the allocation of mobile phone numbers, in contrast to landline numbers, can be expected to be done in a rational and well-defined manner even in developing or emerging market economies which leads to a uniform distribution of the last digits.Footnote 8 The reason is that mobile phone operators that are well-run firms often owned by multinational enterprises are in charge of the number allocation in Serbia.Footnote 9 Two allocation principles are feasible. Under the first one, mobile numbers would be allocated in a piecemeal fashion, where a new phone number is simply the highest existing number plus 1. Under an alternative approach, mobile phone numbers are allocated randomly. Given the large number of mobile phone subscriptions, both approaches would imply a nearly equal distribution of the last digit.Footnote 10

Obviously, there may be preferred numbers allocated to special customers, for instance those where the last couple of digits are all identical, or customers may be given the possibility to choose numbers on their own. However, such occurrences can be expected to be rare and random as different mobile phone users prefer different last digits, thereby not significantly affecting the overall distribution of the last digits of the phone numbers.Footnote 11 To further empirically test the assumption, we used two datasets: (1) the last digits of 182 Serbian mobile phone numbers of firms in the Serbian Business Register and (2) the last digits of 166 Serbian mobile phone numbers from GIZ employees working in the area. In both instances, we did not find a statistically significant deviation from uniform distribution (\(\chi ^{2}\)-goodness-of-fit-tests: \(\chi ^{2}(9) = 3.49,\,p = 0.94\), and \(\chi ^{2}(9) = 6.05,\,p = 0.74\)), which strongly supports our hypothesis.

Under the crosswise model, we therefore asked the following two questions simultaneously to estimate the extent of sales underreporting:

Is the last digit of your best friend’s phone number / of the number of the person you call most often 0 or 1? Does your firm underreport at least 10% of your annual sales to STA for VAT and/or profit tax?

In order to estimate the extent of envelope wages, the following two questions were posed simultaneously:

Is the last digit of your best friend’s phone number / of the number of the person you call most often 8 or 9? Does your firm pay more than 10% of the total wage bill in cash to avoid wage tax and social security contributions?

The questionnaire is included in the Appendix. Obviously, differences in estimated tax evasion obtained from both approaches may also arise due to minor differences in the framing and/or the design of the questions, but here we argue that this is highly unlikely. On the one hand, one potential concern is that under the benchmark approach, respondents are asked to refer to firms similar to their own. These firms may, however, differ in terms of tax compliance behavior, or respondents do not use tax non-compliance of their own firm to estimate tax non-compliance of similar firms. However, in the pilot study preceding the actual survey, some respondents even told the interviewers that they understand that this question is used to infer their own tax non-compliance behavior, and their own behavior is a natural reference point to estimate the behavior of similar firms.Footnote 12

On the other hand, another potential concern is that under the benchmark approach, spontaneous non-response was permitted, either because the respondent refused to answer, or because the respondent states that she/he does not know; however, non-response was not read out by the interviewers as a possible answer option. We assume that non-responses are equivalent to “no” answers to the tax evasion questions, given that non-response is a common strategy to avoid admitting illicit or otherwise sensitive behavior in surveys. Overall, about 23 % of the respondents followed the self-protective strategy with respect to the underreporting of sales and about 22 % for the respective question on envelope wages. By contrast, for firms subject to the CM approach, spontaneous non-response was not permitted in the sense that interviewers “pushed harder” to obtain answers (but ultimately, non-response was still feasible). Here, non-response is more likely to result from “laziness to participate” in CM which may have seemed odd to respondents, rather than from the reluctance to answer the questions. Yet, no respondent chose to refrain from answering the sensitive questions asked under CM. In a robustness check, we test whether this minor difference in the survey design between both approaches on its own gives rise to differences in our estimates of tax evasion.

4 Data

In order to test this hypothesis, we make use of novel information from a rich survey among small- and medium-sized firms in Serbia carried out in November and December 2012 on behalf of the GIZ Public Finance Reform Project. The survey focuses on the perceived efficiency and customer orientation of the Serbian tax system and administration and on different aspects of firms’ tax compliance behavior, as well as on firms’ attitudes towards paying taxes. It was implemented by a professional survey company, using face-to-face interviews with firm representatives, typically either with the owner or with a manager. In the survey, the interviewees were told that that the privacy of their responses was guaranteed by GIZ. In addition, the survey company is not associated as having any connection with the Serbian government or the Serbian revenue administration. In the beginning of the interview, firms were also told that the objective of the survey is to better understand the problems and obstacles that small and medium firms face, in particular in the area of taxation to make tax policy and tax administration more business friendly.

The survey covers 422 firm-level observations, and the sample was drawn from the Serbian Business Register (2011). It is representative of micro-, small- and medium-sized Serbian firms with 1 up to 99 employees operating in manufacturing and service sectors.Footnote 13 In line with standard practice in business surveys, we excluded agriculture and fishing. Given the focus on taxation, we also excluded firms operating in the mining and quarrying sectors, in financial intermediation as well as real estate and renting because the nature of these firms and/or the tax regime they are subject to differs from other firms, complicating comparisons. We also excluded firms operating in various business service sectors (NACE 73 and NACE 74), again, because the nature of these firms may differ significantly from other firms in our sample. This exclusion restriction covers for instance accounting and tax advisory firms, among others. The views on taxation of managers of these types of firms are likely to differ fundamentally from other firms, and their managers may answer more strategically in questions about tax evasion, reflecting the “self-interest” of these sectors. Finally, given that we are interested in private sector firms, we exclude Section L (public administration and defense, compulsory social security), Section M (education), Section N (health and social work) and Section O (other community, social and personal service activities), as these activities are likely to be carried out to a significant extent by public entities or state-owned enterprises. Table 2 provides a summary of the sample.

The sample of firms was split into two subsamples. Both subsamples contain an almost equal number of firms; in addition, there are no significant differences in terms of the sector–size–region distribution of the firms between both subsamples (see Table 2).Footnote 14 In order to achieve this, within each size–sector–region strata, firms were randomly allocated to each of the subsamples. By contrast, in Houston and Tran (2001), Himmelfarb and Lickteig (1982) and Musch et al. (2001) for instance, respondents were drawn randomly across the whole sample to form subsamples for comparison.

Tax evasion within the first subsample, referred to as the “benchmark group,” was then estimated using the conventional approach (the “other people” approach in combination with forgiving wording), whereas tax evasion in the second subsample, referred to as the “treatment group,” was estimated using the CM approach. This allows assessing whether the use of the CM encourages truth-telling and thereby results in higher estimated levels of tax evasion relative to estimates obtained through the conventional method applied to the benchmark group. The similarity of both subsamples ensures that any estimated differences in tax evasion between both subsamples are very likely to be caused by differences in whether or not firms report tax evasion truthfully and are very unlikely to be driven by differences in actual tax compliance behavior.Footnote 15

5 Results

5.1 Baseline results

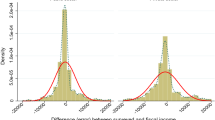

The baseline results are presented in Table 3. Tax evasion is estimated using sampling weights to ensure that the results are representative. The CM estimates are obtained using Eq. (3) in the Appendix. We also constructed confidence intervals using Eq. (5) in the Appendix to check the significance of the estimates. None of the 99 % confidence intervals includes zero which means that the results are highly significant.

The CM results in Table 3 show that 34 % of the firms in our sample underreported at least 10 % of sales, and 30 % paid at least 10 % of employees’ salaries in cash. The same shares for the benchmark group estimated using the conventional method are lower and amount to 24 % and 27 %, respectively.

To further evaluate the statistical significance of the differences between the estimates, we apply two-sample proportion tests as Jann et al. (2012). The difference of 10 % points for the underreporting of sales is marginally significant (p value = 0.06). By contrast, we find no significant differences for estimates of the prevalence of envelope wages (p value = 0.167). Our results therefore partially confirm our hypothesis, namely that tax evasion estimates are higher under the CM approach given that it is designed in a way that the privacy of individual responses is protected.

Nevertheless, the fact that the difference between the CM and benchmark estimates of wage underreporting is not significant requires interpretation. The statistical interpretation is that the increase in anonymity through the introduction of the second non-sensitive question under the CM approach also increases the variance of the CM estimator. The non-sensitive question introduces an additional source of error through the probability q. To compensate for this, a larger sample size or a lower level of privacy protection (through changing the prevalence of the non-sensitive behavior) would be necessary. However, large samples in business surveys are usually expensive, especially for face-to-face interviews. Lowering the level of privacy protection to compensate for the higher variance due to the size of the sample decreases chances that respondents answer truthfully or participate at all. Obviously, one can only speculate whether a larger sample size or lower levels of anonymity would have rendered the estimated difference of the prevalence of wage underreporting between the benchmark and CM approaches significantly.

Alternatively, there may be economic factors as well which explain why CM does not yield higher and statistically different results compared to the benchmark approach. First, respondents may believe, at least to some extent, that wage underreporting attracts less severe penalties in case it is revealed to authorities, irrespective of whether this is the case. In the survey, respondents were also asked to rate the severity of penalties associated with different taxes and social contributions. Indeed, 28.67 % of the respondents consider penalties for VAT evasion as most severe, which is larger than the corresponding shares of respondents for all other taxes and social contributions. Punishment may also be seen as less likely because the agencies in Serbia in charge of investigating informal work practices are sometimes believed by some to be subject to various types of capacity constraints. This, in turn, is sometimes considered as a reason why tackling informal labor remains challenging (International Labour Office 2009; Krstić et al. 2013).

Second, respondents from the benchmark group may have believed that information on wage underreporting is less useful for the authorities if it was revealed by the interviewer. In the latter case, in order to impose penalties, the tax administration would probably have to start a formal investigation, rather than imposing penalties simply based on the information provided through the survey. Contrary to sales underreporting, which can be detected relatively easily by the tax authorities, for instance through checking whether customers of a particular firm were given correct invoices, investigating whether a particular firm pays envelope wages is more demanding. The reason is that both, employers and employees, may have strong incentives to hide this practice as they may both benefit. In contrast to this, customers are likely to be indifferent. Both factors imply that protecting the privacy of the individual responses is more important for questions addressing the extent of sales underreporting compared to questions addressing the extent of envelope wages.

5.2 Robustness checks

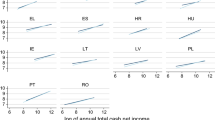

We test the robustness of our results in several ways. First, given that most other papers that apply RRT and CM approaches do not use sampling weights, we re-assess the difference between benchmark and CM estimates using no weights (specification 1 in Table 4). The difference for estimated sales underreporting remains positive and significant, although it slightly decreases.

Second, we only include microfirms with up to 4 employees in our sample (specification 2 in Table 4) which almost halves the sample (in total, there are 222 firms left). While we recognize that further limiting the sample size increases the variance of the CM estimates, it is still insightful to exclude larger firms. The latter are likely to have access to sophisticated, legal tax avoidance strategies, and they are often monitored more intensively by the authorities, especially in developing or emerging market economies, so that estimates of tax evasion that exclude large firms are likely to be larger. This also implies that the protection of the privacy of the answers of the managers of these firms is less important. The difference between the benchmark and CM estimates of sales underreporting indeed increases to 0.17 and is significant at the 5 % level even though the sample size decreases. By contrast, the results hardly change with respect to wage underreporting, perhaps because legal tax avoidance strategies of large firms do not help them to lower the burden from payroll taxes and social security contributions.

Third, we check whether allowing for spontaneous non-response affects the results (specification 3 in Table 4). Our benchmark question differs in the sense that interviewers accepted spontaneous non-response and push respondents “less hard” to provide an answer compared to the treatment group, where respondents were “pushed harder” to answer. In this specification, we use an alternative question to estimate the extent of tax evasion firms under the benchmark approach. This question was posed immediately after the questions on sales and wage underreporting used in the baseline specification. With respect to sales underreporting, the question is: “According to your experience and judgment, on average, what percent of total annual sales do firms like this one underreport to STA for VAT and/or profit tax?” With respect to wage underreporting, the question is: “On average, what share of wages do firms like this one typically pay in cash?” The questions do not use forgiving wording, but the questions preceding each of these questions implicitly justify tax evasion.

For both questions, respondents could select one of the following options: (1) 0 %, (2) 1–10 %, (3) 11–25 % or (4) more than 25 %. While for simplification, this scale was chosen to be not continuous in the survey, we still assume that the combined share of respondents selecting options (3) and (4) corresponds to the share of respondents that underreport at least 10 % of wages and sales, respectively. Contrary to the questions asked to the benchmark group firms in the remaining specifications, this question did not allow for spontaneous non-response, similarly to the questions asked under the CM approach, where interviewers did not accept spontaneous non-response, but pushed harder to obtain a response. Interestingly, the difference between the benchmark and the CM estimates of sales underreporting is again much higher compared to the baseline specification and highly significant at the 1 % level, and the difference between the benchmark and CM estimates of wage underreporting also increases and is likewise significant at the 5 % level.

Fourth, another important concern may be related to our assumption about the distribution of the last digits of mobile phone numbers in Serbia. In particular, the results of CM also depend on the ex ante chosen probability that the last digit of the best friend’s mobile phone number is 0 or 1 (and 8 or 9, respectively). So far, we have assumed a uniform distribution of the last digits. However, it could be argued that in fact, the probability that the last digit is “0” or “1” is higher than 20 % and that the probability that the last digit is “8” or “9” is below 20 %.

To address this, in specification 4 of Table 4, we re-evaluate the difference between the benchmark and CM estimates of sales and wage underreporting where we assume that the probability is 10 % higher (lower) that the last digits are “0” or “1” (“8” or “9”). The difference between the benchmark and the CM estimate (0.09) is only marginally smaller than under our baseline specification in Table 4 when it comes to sales underreporting, and it remains significant at the 10 % level even if we assume that the probability increases to \(p=0.22\). We likewise find no evidence that a lower probability that the last digits are “8” or “9” (\(p=0.18\)) affects the estimates for wage cash payments.

Fifth and finally, in specification 5 of Table 4, we exclude those firms whose responses throughout the entire survey are considered as unreliable by the interviewer. While we do not know the reason of why the interviewer considered the responses to all questions in the survey of a particular firm manager as dishonest in general, this may imply that the firm manager in question also answered the crosswise model questions randomly. However, our results remain robust even when we exclude these firms.

6 Conclusions

This paper revisits the merits of assessing the extent of tax evasion through business surveys. Obviously, respondents in such surveys can be expected to have strong incentives to not answer truthfully questions about sensitive topics. We therefore employ a new survey method, referred to as the crosswise model, which has been successfully applied elsewhere in the social sciences. This approach does not generate data that allow studying the determinants of tax evasion at the individual level. However, its key strength is that it potentially provides more credible estimates about the extent of tax evasion by protecting the privacy of respondents through bundling of sensitive questions about tax compliance behavior and about “harmless” topics. Contrary to other surveys that examine tax evasion, we differentiate between two types of tax evasion, namely underreporting of sales and envelope wages.

This study is the first attempt to obtain credible and more detailed estimates about the extent of tax evasion from businesses themselves, which, from a revenue perspective, are the most important taxpayers as they remit the bulk of taxes to revenue authorities. We show that a significantly higher share of managers of small- and medium-sized firms admits considerable underreporting of sales compared to the case when conventional approaches are used. While we cannot rule out that our results are still downward biased, our results obtained through CM are at least less likely to be affected by any bias relating to the reluctance to answer truthfully. We therefore conclude that such an approach delivers a more, though possibly not fully, realistic picture of tax evasion. The result is robust to a number of alternative specifications. Obviously, even though the respondents were carefully explained the purpose of the crosswise model, they may still have doubted that the privacy of their responses is protected. However, apart from non-response which was low in the survey, CM does not offer a self-protective strategy which is the main advantage relative to other methods of this class.

Future research could extend our work in two ways. First, given that CM only allows obtaining dichotomous information about tax evasion, which makes it difficult to compare our results with estimates of tax evasion obtained by macroeconomic methods, future research could therefore amend CM methodologically to obtain this type of quantitative information as well, for instance through asking several dichotomous questions. Unlike topics such as cheating in exams or drug abuse where a dichotomous answer is revealing and informative, from a tax policy perspective, it is also important to obtain more precise estimates about the extent of tax evasion in quantitative terms and hence of foregone revenue. Second, it would be ideal to test the robustness of our findings within a larger sample, in particular since we had to split the sample to study the relative merits of the crosswise model compared to our benchmark. However, in the light of inevitable budget constraints and given that our data come from a detailed face-to-face business survey about tax issues, the size of our overall sample is appropriate and comparable to other business surveys.

Notes

See for instance Long and Swingen (1991). In his paper, Slemrod (2007, p. 25) asks the reader provocatively: “Would you answer survey questions about tax evasion honestly?” Hessing et al. (1988) compare self-reported non-compliance with findings of intensive audits and find no correlation between both which is likely the result of dishonest survey responses.

There are also macroeconomic approaches often referred to as indirect strategies which are used to estimate the size of the overall shadow economy which is broader than the concept of tax evasion; see Schneider and Enste (2000) for a survey of the literature. Henderson et al. (2012) is one of the more innovative papers: they use luminosity as measured from outer space as an indicator of “true” economic activity. Ahmed and Rider (2013) estimate the tax gap by tax type using yet another approach, namely by calculating potential revenue using measures of the tax base that are less likely subject to intentional misreporting.

A related strand of the literature studies the effects of enforcement and audit threats on tax compliance behavior. Almunia and Lopez-Rodriguez (2012) exploit a discontinuity in enforcement in Spain that arises as taxes from firms above a certain size threshold are collected by a large taxpayer unit which also monitors firms more intensively. By contrast, Slemrod et al. (2001) studies the effects of threat letters randomly sent to taxpayers.

Harwood et al. (1993) review randomization techniques used elsewhere in the social sciences with a view to facilitate application in the context of tax compliance.

In Serbia, a high proportion of workers are paid exactly the minimum wage which is sometimes seen to suggest that envelope wages are also common. Employers and employees may benefit from envelope wages and may therefore jointly agree on this practice; see Schmidt and Vaughan-Whitehead (2011) for a discussion of envelope wages in Serbia and other countries of the region.

We basically follow the notation of Yu et al. (2008). To avoid confusion with significance levels, we chose the letter “q” instead of “p” standing for the probability to observe the non-sensitive item.

STA stands for ‘Serbian Tax Administration’

This implies that Benford’s law which we discuss in the Supplementary Material and which would distort our estimates does not apply.

The Republic Agency for Electronic Communications in Serbia (RATEL) allocates the entire range of subscriber numbers which follow the network code to the mobile phone operator. This implies that the mobile phone operator is also in charge of allocating the last digit of mobile phone numbers to the individual subscribers. See Serbian Numbering Plan for more details (http://www.ratel.rs/upload/documents/Regulativa/Plan_numeracije/Numbering_plan.pdf). In addition, we also requested and received information from Telenor, which is the second largest mobile phone operator serving about one-third of the Serbian mobile phone customers according to RATEL (2013) that mobile phone numbers are indeed allocated in a piecemeal fashion.

By 2012, there were 9.14 million active mobile users in Serbia, resulting in an overall mobile penetration rate of 126.2 % (RATEL 2013).

Obviously, there may be other factors that potentially confound this randomization mechanism. Some participants may only know the landline number or imperfectly remember the mobile number, even though participants were asked to look up the number in their phone. However, these factors are unlikely to be systematic and/or of significance.

We recognize, however, that in other settings and contexts, this assumption is questioned; see for instance Clarke (2012b).

The survey is based on the NACE Rev. 1.1 industry classification.

One reason for the small difference in terms of subsample size relates to differences in participation rates in the survey. However, participation in the interview did not depend on whether firms were assigned to the benchmark group or the treatment group as this information was only revealed to them in the course of the interview.

We also compared the subsamples by other variables not reported in this paper that were potentially correlated with tax evasion such as perceptions about corruption among tax officials and the perceived probability of tax audits. Again, the subsamples turned out to be nearly identical.

References

Ahmed, R. A., & Rider, M. (2013). Using microdata to estimate pakistan’s tax gap by type of tax. Public Finance Review, 41(3), 334–359.

Alm, J. (2012). Measuring, explaining, and controlling tax evasion: Lessons from theory, experiments, and field studies. International Tax and Public Finance, 19(1), 54–77.

Alm, J., & McClellan, C. (2012). Tax morale and tax compliance from the firm’s perspective. Kyklos, 65(1), 1–17.

Almunia, M., & Lopez-Rodriguez, D. (2012). The efficiency cost of tax enforcement: Evidence from a panel of spanish firms. unpublished manuscript.

Azfar, O., & Murrell, P. (2009). Identifying reticent respondents: Assessing the quality of survey data on corruption and values. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 57(2), 387–411.

Barton, A. H. (1958). Asking the embarrassing question. Public Opinion Quarterly, 22(1), 67.

Becker, R., & Günther, R. (2004). Selektives Antwortverhalten bei Fragen zum delinquenten Handeln: eine empirische Studie über die Wirksamkeit der “sealed envelope technique” bei selbst berichteter Delinquenz mit Daten des ALLBUS 2000. ZUMA Nachrichten, 28(54), 39–59.

Boruch, R. F. (1971). Assuring confidentiality of responses in social research: A note on strategies. The American Sociologist, 6(4), 308–311.

Chaudhuri, A., & Christofides, T. C. (2007). Item count technique in estimating the proportion of people with a sensitive feature. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference, 137(2), 589–593.

Clarke, G. (2011). Lying about firm performance: Evidence from a survey in Nigeria. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=1971575

Clarke, G. (2012a). Do reticent managers lie during firm surveys? Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=2028725

Clarke, G. (2012b). What do managers mean when they say “firms like theirs” pay bribes? International Journal of Economics and Finance, 4(10), 1–9.

Clausen, B., Kraay, A., & Murrell, P. (2011). Does respondent reticence affect the results of corruption surveys? Evidence from the World Bank Enterprise Survey for Nigeria. In S. Rose-Ackerman & T. Søreide (Eds.), International handbook on the economics of corruption (Vol. 2, pp. 428–450). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Coutts, E., & Jann, B. (2011). Sensitive questions in online surveys: Experimental results for the randomized response technique (RRT) and the unmatched count technique (UCT). Sociological Methods & Research, 40(1), 169–193.

Dabla-Norris, E., Gradstein, M., & Inchauste, G. (2008). What causes firms to hide output? The determinants of informality. Journal of Development Economics, 85(1–2), 1–27.

Diekmann, A. (2012). Making use of “Benford’s Law” for the randomized response technique. Sociological Methods & Research, 41(2), 325–334.

Droitcour, J., Caspar, R. A., Hubbard, M. L., Parsley, T. L., Visscher, W., & Ezzati, T. M. (1991). The item count technique as a method of indirect questioning: A review of its development and a case study application. Measurement Errors in Surveys, 11, 185–210.

Edgell, S. E., Himmelfarb, S., & Duchan, K. L. (1982). Validity of forced responses in a randomized response model. Sociological Methods & Research, 11(1), 89–100.

Feldman, N. E., & Slemrod, J. (2007). Estimating tax noncompliance with evidence from unaudited tax returns. The Economic Journal, 117(518), 327–352.

Gemmell, N., & Hasseldine, J. (2012). The tax gap: A methodological review. Advances in Taxation, 20, 203–231.

Gërxhani, K. (2007). “Did you pay your taxes?” How (not) to conduct tax evasion surveys in transition countries. Social Indicators Research, 80(3), 555–581.

Greenberg, B. G., Abul-Ela, A.-L. A., Simmons, W. R., & Horvitz, D. G. (1969). The unrelated question randomized response model: Theoretical framework. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 64(326), 520–539.

Harwood, G., Larkins, E., & Martinez-Vazquez, J. (1993). Using a randomized response methodology to collect data for tax compliance research. Journal of the American Taxation Association, 15(2), 79–92.

Henderson, J. V., Storeygard, A., & Weil, D. N. (2012). Measuring economic growth from outer space. American Economic Review, 102(2), 994–1028.

Hessing, D. J., Elffers, H., & Weigel, R. H. (1988). Exploring the limits of self-reports and reasoned action: An investigation of the psychology of tax evasion behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(3), 405–413.

Himmelfarb, S., & Lickteig, C. (1982). Social desirability and the randomized response technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(4), 710–717.

Houston, J., & Tran, A. (2001). A survey of tax evasion using the randomized response technique. Advances in Taxation, 13, 69–94.

International Labour Office. (2009). Labour inspection and labour administration in the face of undeclared work and related issues of migration and trafficking in persons: Practices, challenges and improvement in Europe towards a labour inspection policy. In National Workshop on labour inspection and undeclared work. Budapest, October 2009.

Jann, B., Jerke, J., & Krumpal, I. (2012). Asking sensitive questions using the crosswise model: An experimental survey measuring plagiarism. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(1), 32–49.

Jensen, N. M., & Rahman, A. (2011). The silence of corruption: Identifying underreporting of business corruption through randomized response techniques. World Bank policy research working paper 5696.

Joulfaian, D., & Rider, M. (1998). Differential taxation and tax evasion by small business. National Tax Journal, 51(4), 676–687.

Karlan, D. S., & Zinman, J. (2012). List randomization for sensitive behavior: An application for measuring use of loan proceeds. Journal of Development Economics, 98(1), 71–75.

Krstić, G., Schneider, F., Arandarenko, M., Arsić, M., Radulović, B., Ranđelović, S., et al. (2013). The shadow economy in Serbia. USAID Serbia and Foundation for the Advancement of Economics: New Findings and Recommendations for Reform.

Kuha, J., & Jackson, J. (2014). The item count method for sensitive survey questions: Modelling criminal behaviour. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C (Applied Statistics), 63(2), 321–341.

Lensvelt-Mulders, G. J. L. M. (2005). Meta-analysis of randomized response research: Thirty-five years of validation. Sociological Methods & Research, 33(3), 319–348.

Long, S. B., & Swingen, J. A. (1991). Taxpayer compliance: Setting new agendas for research. Law & Society Review, 25(3), 637–683.

Musch, J., Bröder, A., & Klauer, K. C. (2001). Improving survey research on the World-Wide Web using the randomized response technique. In U.-D. Reips & M. Bosnjak (Eds.), Dimensions of internet science (pp. 179–192). Lengerich: Pabst.

Näher, A.-F., & Krumpal, I. (2012). Asking sensitive questions: The impact of forgiving wording and question context on social desirability bias. Quality & Quantity, 46(5), 1601–1616.

Pissarides, C. A., & Weber, G. (1989). An expenditure-based estimate of Britain’s black economy. Journal of Public Economics, 39(1), 17–32.

Raghavarao, D., & Federer, W. T. (1979). Block total response as an alternative to the randomized response method in surveys. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 41(1), 40–45.

Republic Agency for Electronic Communications, Serbia (RATEL) (2013). An Overview of Telecom Market in the Republic of Serbia in 2012. Retrieved from http://www.ratel.rs/upload/documents/Pregled_trzista/An_Overview_of_Telecom_Market_in_the_Republic_of_Serbia_in_2012.pdf.

Schmidt, V., & Vaughan-Whitehead, D. (2011). Wage trends and wage policies in South-East Europe: What impact of the crisis? In V. Schmidt & D. Vaughan-Whitehead (Eds.), The impact of the crisis on wages in South-East Europe (pp. 1–26). Geneva: International Labour Organization.

Schneider, F., & Enste, D. H. (2000). Shadow economies: Size, causes, and consequences. Journal of Economic Literature, 38, 77–114.

Slemrod, J. (2007). Cheating ourselves: The economics of tax evasion. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(1), 25–48.

Slemrod, J., Blumenthal, M., & Christian, C. (2001). Taxpayer response to an increased probability of audit: Evidence from a controlled experiment in Minnesota. Journal of Public Economics, 79(3), 455–483.

Slemrod, J., & Weber, C. (2012). Evidence of the invisible: Toward a credibility revolution in the empirical analysis of tax evasion and the informal economy. International Tax and Public Finance, 19(1), 25–53.

Torgler, B. (2011). Tax morale and compliance? Review of evidence and case studies for Europe. World Bank policy research working paper series 5922.

Tourangeau, R., & Yan, T. (2007). Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychological Bulletin, 133(5), 859–883.

Warner, S. (1965). Randomized response: A survey technique for eliminating evasive answer bias. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 60(309), 63–69.

Yu, J.-W., Tian, G.-L., & Tang, M.-L. (2008). Two new models for survey sampling with sensitive characteristic: Design and analysis. Metrika, 67(3), 251–263.

Zitzewitz, E. (2012). Forensic economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 50(3), 731–769.

Acknowledgments

We thank Aleksandar Dragojlović, Friedrich Heinemann, Anders D. Jensen, Lars Kunze, Friedrich Schneider and participants of the 2013 Shadow Economy conference and of 69th IIPF Annual Congress for excellent comments. The views expressed in this paper are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, a German aid agency, and those of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation (Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung, BMZ). The views expressed in this paper should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management. The survey underlying this paper was carried out by the “Public finance reform project in Serbia” which is implemented by GIZ on behalf of BMZ. We also thank Mark Trappmann who implicitly suggested applying the crosswise model to study tax evasion in his presentation at the 1st Friedrich-Alexander University Nuremberg-Erlangen (FAU) Workshop on Tax Compliance 2012.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Estimation of the unknown prevalence of the sensitive characteristic

In this Appendix, we reproduce the derivation of CM as presented in Yu et al. (2008). Table 5 (second row) illustrates how the four different respondent categories map into answer options (1) and (2). It shows that the respondents can always be sure that interviewer does not know the true answer on the sensitive question, irrespective of whether the respondents choose answer option (1) or (2) because the corresponding subgroups are all non-sensitive. The third row contains the unobserved probability of each answer category. The observed number of respondents choosing option (1) \(n_1 \) follows a binomial distribution with \(E(n_1 )=n\lambda \) and \(\mathrm{Var}(n_1 )=n\lambda (1-\lambda )\).

The log likelihood function is given by

which is analogous to the likelihood function in CM presented by Yu et al. (2008) and similar to those under RRT presented by Warner (1965). The first-order condition is

Solving for \(\pi \) yields the unbiased maximum likelihood estimator for the sensitive characteristic

where \(q\ne 0.5\) and where \(\hat{{\lambda }}=\frac{n_1}{n}\) is the maximum likelihood estimate of \(\lambda \) from (2) and thus equal to the observed share of respondents choosing answer option (1), i.e., the respondents who either share both characteristics or no characteristics.

The variance of \(\hat{{\pi }}\) can be written as

In order to obtain an unbiased estimate of (4), we have to multiply (4) by \(\frac{n}{n-1}\), given that the mean of the distribution function is unknown (Bessel’s correction):

As Eq. (5) demonstrates, increasing the level of privacy protection lowers the efficiency of the estimate, as increasing q raises the variance as well. With \(n\rightarrow \infty \), (5) allows constructing confidence intervals for \(\hat{{\pi }}\):

where \(Z_{\alpha /2}\) denotes the \(((1-\alpha /2)\times 100)th\) percentile of the standard normal variable Z.

Appendix 2: English translation of questionnaire

1.1 Introductory statement

Good morning/day/evening, my name is __________________. I am an interviewer in the research agency [name of survey company] which carries out various types of research on different topics, and I would appreciate if you agreed to answer some questions for me. The survey is carried out on behalf of Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), a publically owned German organization for international development cooperation. GIZ supports the Serbian government in implementing reforms that strengthen the Serbian economy. For this reason, GIZ uses this survey to better understand the problems and obstacles that small and medium firms face, in particular in the area of taxation to make tax policy and tax administration more business friendly.

Your firm has been selected for this survey, and your views are very important to GIZ. Participating will offer you the unique opportunity that your views and problems will feed into the policy advice that GIZ gives to the Serbian government. This advice improves the conditions of firms like yours.

Confidentiality is very important for [name of survey company] and GIZ. As a German publically owned company, GIZ generally obeys strict international data protection standards. All obtained answers will be treated as group data and will be used solely for the purpose of this survey and not passed onto third parties.

1.2 Benchmark questions

1.3 Crosswise model questions

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kundt, T.C., Misch, F. & Nerré, B. Re-assessing the merits of measuring tax evasion through business surveys: an application of the crosswise model. Int Tax Public Finance 24, 112–133 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-015-9373-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-015-9373-0