Abstract

The Neotropical region has the greatest taxonomic and functional diversity of fish in the world. However, this biodiversity has been threatened by the introduction of non-native species. Therefore, we present a systematic review of the literature concerning the introduction of non-native fish species in Neotropical freshwaters. We examine the origins of non-native fish species, as well as the invaded ecoregions and introduction vectors. Oncorhynchus mykiss, Salmo trutta, Cichla kelberi, and Oreochromis niloticus were the most frequent introduced fish species and rivers and reservoirs were the most studied freshwater ecosystems. Impoundments, aquarium trade, sport fishing, and aquaculture were recorded as the main vectors for the introduction of non-native fish species. Most of the studies were conducted in Brazil. The Upper Parana ecoregion exhibited the largest number of non-native fish species, of which the majority originated from the Lower Parana ecoregion. We noticed that the origins of non-native fish species are linked to their introduction vectors, as several non-native fish species arrive from areas near to where they are introduced, mainly by impoundment and sport fishing. On the other hand, species from regions outside the Neotropics are especially introduced by aquarium trade and aquaculture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Neotropical region hosts the greatest taxonomic and functional diversity of freshwater fish on the planet (Toussaint et al., 2016), and more than 5,000 valid fish species have been recorded throughout this area (Albert & Reis, 2011; Reis et al., 2016; Eschmeyer & Fong, 2017). In addition, the number of new fish species recently studied or described has been increasing exponentially in the last years (Ota et al., 2015; Reis et al., 2016), while many others are still unknown to science (Vitule et al., 2017). The total number of described Neotropical freshwater fish species represents approximately one-tenth of the global diversity of vertebrates (Pelicice et al., 2017) and around one-third of the global diversity of freshwater fish (Reis et al., 2016; Pelicice et al., 2017). Despite the extensive richness and high contribution to global biodiversity, approximately 35% of Neotropical fish species are threatened with extinction (IUCN, 2017). Multiple stressors associated with anthropic activities, such as urbanization, water pollution, flow modification, habitat destruction, over-exploitation, and non-native species introduction, have impaired freshwater environments and have caused significant negative effects on freshwater fish biodiversity also to the global scale (Dudgeon et al., 2006; Pelicice et al., 2017).

The introduction of non-native fish species, both intentionally and unintentionally, has caused biodiversity loss around the world (Vitule et al., 2009; Clavero et al., 2013; Pelicice et al., 2014). The main negative effects are the reduction of native species diversity, habitat alteration, hybridization, competition, predation, and parasitism, as well as changes in the structure of community food webs, nutrient cycling, and, consequently, ecosystem function (Simberloff & Rejmánek, 2011). Despite these negative effects, fish species continue to be introduced in the Neotropical region (Magalhães & Jacobi, 2017; Ribeiro et al., 2017), especially for economic reasons such as aquaculture and sport fishing, neglecting the accompanying environmental and social issues (Azevedo-Santos et al., 2011; Lima et al., 2016; Padial et al., 2017; Ribeiro et al., 2017).

Once non-native fish species are introduced into a particular basin of a country, the effects can be propagated to other countries, seeing that many aquatic ecoregions cover more than one country. The dispersion and distribution of fish species are limited regionally by the surroundings of the watersheds and limited locally by natural barriers as falls, rapids, and pools (Jackson et al., 2001; Abell et al., 2008). In this way, fish species may be distributed throughout the drainage area of a river basin because there is no limitation locally. Thus, fish do not recognize the geopolitical limits of a country as limiting to dispersion. However, measures of conservation of the native fauna, as well as the control and management of invasions, are adopted at the level of geopolitical limits (states or countries each with its own legislation).

Several vectors of the introduction of non-native fish species to the Neotropical region have been recorded (Daga et al., 2015, 2016), but most studies have identified aquaculture (Orsi & Agostinho, 1999; Lima et al., 2016), aquarism (Padilla & Williams, 2004), sport fishing (Pixer & Petrere, 2009; Vitule et al., 2014; Ribeiro et al., 2017) and stocking (Agostinho et al., 2010) as the primary means of release, often intentional, of these species into the environment. In addition, the construction of dams, which may remove geographic barriers, has also been identified as an important vector for the introduction of fish species (Júlio et al., 2009; Daga & Gubiani, 2012; Vitule et al., 2012). Therefore, the knowledge and identification of the main pathways and vectors of introduction of non-native species can provide important information to help regulatory agencies detect invaders more quickly (Simberloff et al., 2013) and act to reduce the rate of their spread (Havel et al., 2015). Thus, it is important to address the knowledge gaps concerning the introduction vectors of non-native fish in the Neotropical region.

In most cases, the origin of an introduced species is linked to an introduction vector. Many fish species have been introduced as a result of globalization (Cambray, 2003), which has eased transport and transit by sea and air between continents, thus promoting the dispersal of species previously isolated on other continents to the Neotropics. In several regions of the world, African cichlids (tilapia, Zambrano et al., 2006; Britton & Orsi, 2012; Forneck et al., 2016), Asian and European cyprinids (carp, Zambrano et al., 2006; Singh & Lakra, 2011; Britton & Orsi, 2012) and North American salmonids (salmon, Fausch, 2007; Diana, 2009) are among the main species cultivated in aquaculture. Piscivorous species, including active translocated predators such as the Amazonian peacock bass, are among the main species that have been introduced for sport fishing in the upper Paraná River basin (Agostinho et al., 2005; Fugi et al., 2008).

In Brazil, which boasts one of the highest biodiversity levels in the Neotropical region (Myers et al., 2000; Lewinsohn & Prado, 2005; Reis et al., 2016), research has shown that several species of fish have been introduced (Júlio Jr. et al., 2009; Vitule et al., 2012; Frehse et al., 2016); however, the number of non-native fish species in the Neotropics is estimated to be much higher than that in Brazil alone (115 non-native fish species in the Supplementary Material in Frehse et al., 2016). Thus, knowing the distribution, origin, and vectors of introduction of non-native species is essential for implementing preventive measures and mitigating the deleterious effects of these species on the environments to which they are introduced.

Given the gaps highlighted above, the purpose of this paper was to explore and review the literature on non-native fish species to evaluate the main aspects related to the introduction of fish species in the Neotropical freshwaters. Specifically, we aimed to (a) verify the temporal trend in the publications on non-native freshwater fish species in Neotropics; (b) identify the journals with the largest number of articles published on non-native freshwater fish species; (c) evaluate which countries have both the highest number of articles published and non-native freshwater fish species introduced; (d) determine which freshwater habitats were the most studied and the number of non-native freshwater fish species per environment; (e) identify the number of non-native freshwater fish species introduced into the Neotropical aquatic ecoregions; and (f) identify the origin and vectors of non-native freshwater fish species introduction. The knowledge summarized in this review could be useful for describing general patterns of non-native fish species occurrence and guiding actions to prevent and manage invasions in this region.

Materials and methods

In March 2017, a systematic review was performed using the Thomson Reuters database [ISI Web of Knowledge (apps.isiknowledge.com)], searching for all publications that addressed the topic of “non-native fish species in freshwater environments in the Neotropical region.” For the purpose of this paper, any species that occurred outside its natural range was considered to be non-native. The search terms in the “Topic” field were as follows: (Neotropical) AND (fish*) AND (species) AND (inva* OR alien OR exotic OR non-native OR non-indigenous OR introduced) AND (aquatic OR freshwater OR reservoir OR lake OR stream OR river OR lagoon OR floodplain OR wetland), and the timespan included all years up to the date of the search. The search was then refined according to the following Research areas: Environmental Sciences, Ecology, Zoology, Freshwater Biology, Biodiversity, Conservation, and Fisheries and Water Resources. In addition, all articles including lists of fish species only from the Neotropical region and published in the journal Check List: Journal of Species Lists and Distributions, which is not indexed on the ISI Web of Science database, were also included in our review. For this, the search was carried out using the option “search for articles” at the journal website (http://www.checklist.org.br/search) and searching all categories and volumes.

Three criteria were required to be met for a study to be included in this systematic review: (i) the article recorded the occurrence of non-native fish species in its study area; (ii) the study was carried out in freshwater environments; and (iii) the study was performed in the Neotropical region. Non-related articles were excluded based on the title, abstract, or, if necessary, after a careful reading of the entire text. Previous reviews and meta-analysis were excluded. The articles that met the abovementioned criteria were selected and included in our analysis. The following data were extracted: (a) year of publication, which was used to determine the trend in the timing of publications; (b) journal, which was used to identify the journal with the most publications on non-native freshwater fish species in the Neotropical region; (c) country, which was used to identify both the highest number of articles published and the number of non-native fish species per country. We examined these data separately for country and ecoregion scales. For this, we calculated the total number of non-native fish species by country and classified them as proposed by Ellender & Weyl (2014) as alien species, which have been introduced from outside the geopolitical limits of a country and extralimital species, which have been translocated into areas in a same country where they did not naturally occur; (d) freshwater environment, which identified the most studied environment in terms of the occurrence of the non-native fish species and the number of species per environment; (e) non-native freshwater fish species introduced into the Neotropical region; (f) ecoregion, which represented the number of non-native fish species per freshwater ecoregion classified according to Abell et al. (2008); and (g) vector of introduction, which was defined in terms of propagule pressure and colonization. The last information was obtained, when available, using the paper itself or from other references about a particular species. For Brazil, for example, we used the I3N Brazil Invasive Alien Species Database (I3N, 2017). In addition, distribution information on non-native fish species was reviewed by experts. The vectors of introduction were divided into nine categories: (a) impoundment, species whose first records of occurrence followed shortly after the construction of a dam, especially when the natural barriers were removed; (b) aquarium trade, species introduced through the practice of fishkeeping; (c) aquaculture, species widely used in fish farms in the region; (d) sport fishing, species introduced for sport fishing; (e) baiting, species introduced because of their use as live baits in sport fishing; (f) biological control, species introduced mainly for the control of mosquitos and other organisms; (g) commercial fishing, species introduced through stocking to facilitate professional fishing; (h) river transposition, species introduced due to the construction of water transfer schemes, which connect a river to another river basin; and (i) unknown, species whose vector of introduction was not identified based on our criteria. We also identified species origin, which referred to the source of non-native fish species introduced into freshwater environments in the Neotropical region. We considered the aquatic ecoregion, as defined by Abell et al. (2008) as the ecoregion in which the species occurs naturally and where it is native, as their place of origin.

The presented data do not necessarily represent the number of papers, but rather the information included in the studies, because not all the articles presented all the information of interest, and beyond that, the numbers included in the analysis are not always the same, seeing that papers were counted multiple times when necessary (e.g., some studies were conducted in more than one country, freshwater environment, or ecoregion or one species can be considered to have been introduced by more than one vector) (see the total number of data per analysis in Table S1—Supplementary Material).

Results

In total, 885 articles were found and examined, and 292 papers satisfied the selection criteria and constituted the final list for this review (Table S2—Supplementary Material). The first available paper according to the established criteria was published in 1985 (Fig. 1), but the number of articles recording the occurrence of non-native freshwater fish species in the Neotropical region has significantly increased over the years (non-linear fit; r = 0.81; P < 0.01; Fig. 1), especially after 2005, with a peak of 43 published articles in 2015 (Fig. 1). Ninety-nine journals published papers with records of non-native fish species in the Neotropical region (Table S2—Supplementary Material, Fig. 2). Most articles have been published in journals in the fields of ecology, biodiversity and conservation, limnology and fisheries, and 67% have been published in 22 journals (Fig. 2). Check List: Journal of Species Lists and Distributions and the Brazilian Journal of Biology were the journals with the highest numbers of publications (9%, n = 26 and 6%, n = 18 articles, respectively, Fig. 2). More than half of the studies on the occurrence of non-native fish species in freshwater environments in the Neotropical region were conducted in Brazil (56%, n = 164 articles, Fig. 3a). Furthermore, one hundred sixty-three non-native fish species occurred in Brazil (Fig. 3b). Of this total, 131 non-native fish species were classified as extralimital and 32 as aliens (Fig. 3b). For most of the countries, the proportion of non-native fish species classified as aliens was higher than the extralimitals, except for Brazil. In addition, in the US Virgin Islands and Peru, only alien species were recorded (Fig. 3b).

The most studied freshwater environments in terms of occurrences of non-native fish species in the Neotropical region were rivers (35%, n = 104 articles), reservoirs (23%, n = 67 articles) and lakes (17%, n = 49 articles), and the fewest number of articles addressed floodplains and lagoons (6%, n = 17 and 4%, n = 13 articles, respectively, Fig. 4a). In addition, rivers and reservoirs also presented the highest number of non-native fish species, 117 and 95, respectively (Fig. 4b). The most-recorded non-native fish species in Neotropical rivers were Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum, 1792) (58 records), Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758) (35 records) and Salmo trutta Linnaeus, 1758 (28 records), whereas Cichla kelberi Kullander & Ferreira, 2006 (68 records), Plagioscion squamosissimus (Heckel, 1840) (40 records), and O. niloticus (36 records) were the species with the highest levels of occurrence in reservoirs.

Altogether, 192 non-native fish species (Table S3—Supplementary Material) were recorded in some type of freshwater environment in the Neotropical region, and they were distributed among 14 orders and 49 families (Table S3—Supplementary Material). The orders with the greatest non-native fish species richness were Characiformes (29%, n = 55 species), Siluriformes (21%, n = 41 species), and Perciformes (19%, n = 37 species) (Table S3—Supplementary Material). Cichlidae (23 species, 12%), Cyprinidae (15 species, 8%), and Loricariidae (14 species, 7%) were the families with the highest numbers of non-native fish species. Oncorhynchus mykiss (207 occurrences), O. niloticus (105 occurrences), and S. trutta (100 occurrences) were the most frequent species recorded in Neotropical freshwater environments.

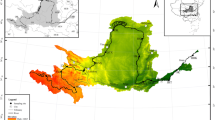

Non-native fish species occurred in 43 ecoregions in the Neotropics (Fig. 5, ca. 48% of the ecoregions in the Neotropics, total number of ecoregions in the Neotropics: ca. 90, sensu Abell et al., 2008). The Upper Parana ecoregion presented the largest number of non-native fish species (105 species, Fig. 5), but three other important ecoregions, Iguassu, Paraiba do Sul, and Northeastern Mata Atlantica, also presented high numbers of non-native fish species (27, 22, and 21 non-native fish species, respectively, Fig. 5).

Distribution of the number of non-native fish species in freshwater environments in the Neotropical region per ecoregion. Ecoregions are shown according to Abell et al. (2008)

The main vector of introduction in the Neotropical region was impoundment (88 species, 27%, n = 324, Fig. 6), especially due to the construction of the Itaipu Dam (60 species, 69% of the non-native fish species introduced by impoundment, Table S2—Supplementary Material). In addition, the aquarium trade (16%, n = 324), sport fishing (14%, n = 324), and aquaculture (12% of the non-native fish species, n = 324) were important vectors of the introduction of non-native fish species in the Neotropical region; they, along with impoundment, were collectively responsible for 70% (n = 324, Table S2—Supplementary Material) of the introductions. The most non-native fish species introduced by impoundment were classified as extralimital, especially due to Itaipu dam. In addition, non-native fish species introduced by baiting were only extralimitals (Fig. 6). For aquarium trade and aquaculture, the most of non-native fish species introduced by these vectors were alien species (Fig. 6).

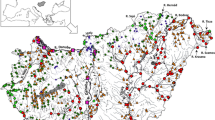

Aquaculture, sport fishing, aquarium trade and biological control showed widespread spatial occurrences of introductions of non-native fish species in the Neotropical region (Fig. 7), while impoundment, baiting, commercial fishing, and river transposition showed concentrated spatial occurrence, being responsible for local species introductions (Fig. 7). Non-native fish species originated from 55 of the 426 ecoregions described by Abell et al. (2008).

Extralimital non-native fish species originated in South American ecoregions (70% of the introduced fish species, n = 206, Table S2—Supplementary Material). Lower Parana (41%, n = 144) and Amazonas Lowlands (16%, n = 144) were the ecoregions that most contributed to the origin of non-native fish species (Fig. 8a, Table S2—Supplementary Material). The most alien non-native fish species originated in Nearctic region (Fig. 8b, 24%, n = 62). Alaska and Canada Pacific Coastal was the ecoregion that most contributed to the non-native alien fish species (four salmonids non-native fish species). In addition, important species such as cichlids and cyprinids originated in African and Asian ecoregions, respectively.

Distribution of the number of non-native fish species in freshwater environments in the Neotropical region per (a) fish species originated from Neotropical ecoregions; and per (b) fish species originated from different biogeographic regions. Sites of origin defined by the ecoregions described in Abell et al. (2008)

Discussion

In general, our results that the origins of non-native fish species are linked to their introduction vectors. The large majority of non-native fish species in Neotropical freshwaters was recorded in Brazil, and it is from other Neotropical aquatic ecoregions, and it is introduced, especially by impoundment and sport fishing. In contrast, a smaller number of non-native fish species are from other ecoregions, outside the Neotropics, and are mainly introduced by aquarium trade and aquaculture.

Studies on non-native fish species occurrence in the Neotropical freshwaters have increased exponentially in the last years, possibly in conjunction with the evolution of scientific production in the Neotropics, especially on Brazil in the 2000s (Regalado, 2010). The number of published articles mainly began to increase in the late 1990s and early 2000s when most journals became available online. In addition, biological invasions began to draw the attention of ecologists (Richardson & Pyšek, 2008; Pelicice et al., 2017) so much that important journals addressing the patterns and processes of invasion such as Biological Invasions and Aquatic Invasions emerged during this period, contributing to the increase in the number of publications on non-native fish species in the Neotropics.

The number of non-native fish species established in the world’s main river basins is related to increased human activities in the drainage areas, especially dam construction, which modifies the waterflow. Our results showed the highest occurrence of non-native fish species to be in rivers and reservoirs. Rivers play a fundamental role in the maintenance of aquatic biodiversity and ecosystem services in the Neotropical region (Agostinho et al., 2004, 2005), but rivers are more susceptible to biological invasions than other freshwater environments since water flow facilitates species dispersal (Biagioni et al., 2013). Additionally, reservoirs are man-made environments that are known to facilitate invasions where they are formed (Johnson et al., 2008; Vitule et al., 2012), as they act as stepping-stones for the dispersal of non-native species across landscapes (Havel et al., 2010). In Brazil, for example, hydrographic basins with a large number of reservoirs (e.g., Paraná River basin, Agostinho et al., 2008, 2016) also contain a large number of non-native fish species (Vitule et al., 2012; Ortega et al., 2015). It is important to report that most of the articles focused on Brazil, for which the greatest number of non-native fish species (163; 131 extralimital, 32 alien) was recorded. Brazil has continental dimensions, which make it the largest contributor in terms of area to the Neotropical region, and Brazil has the largest human population in the Neotropical region as well. As widely reported, there is a positive correlation between non-native fish introductions and human population density (Taylor & Irwin, 2004; Agostinho et al., 2005; Daga et al., 2015).

According to our results, Oncorhynchus mykiss, Oreochromis niloticus, and Salmo trutta were the species with the highest number of records in the Neotropical aquatic ecoregions. Salmonids were initially introduced in the South America for recreational purposes in the early 1900s, and additional introductions occurred during the 1970s when they were farmed for aquaculture purposes (Pascual et al., 2001; Sepúlveda et al., 2013). Oncorhynchus mykiss, for example, have become the most conspicuous freshwater fish in Patagonia, inhabiting every basin in the region (Pascual et al., 2001). Our study also indicated a lot of cichlids species introduced in Neotropical freshwaters, such as peacock bass (Cichla spp.) and Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), which were the most common non-native fish species in Neotropical reservoirs. In addition, we reported that Cichla kelberi was introduced mainly for sport fishing, while O. niloticus was introduced for aquaculture. According to Agostinho et al. (2008, 2016), the practice of stocking reservoirs with non-native fish species, especially the peacock bass, South American silver croaker and Nile tilapia, to mitigate the impacts of dams, began in the Brazilian northeast and later became widespread in the south and southeast of Brazil. In addition, some fish species, mainly those considered to be extremely dangerous for recipient environments, including top predators such as peacock bass (Cichla spp.), the dorado (Salminus brasiliensis) (Vitule et al., 2014; Ribeiro et al., 2017), and black bass (Micropterus spp.) (Kerr & Kamke, 2003; Arlinghaus et al., 2007) have been introduced by sport fishing.

The Neotropical region contains approximately 12% of all ecoregions described by Abell et al. (2008), but these ecoregions contain some of the highest levels of fish biodiversity on the planet (Toussaint et al., 2016; Reis et al., 2016; Eschmeyer & Fong, 2017). However, the presence of non-native fish species can caused the loss of biodiversity (Vitule et al., 2009; Clavero et al., 2013; Ruaro et al., 2018), and a high degree of endemism may indicate an increased risk of global extinction (Gubiani et al., 2010; Daga & Gubiani, 2012; Daga et al., 2016). According to our results, the Upper Parana, Iguassu, Paraiba do Sul, and Northeastern Mata Atlantica ecoregions showed high numbers of non-native fish species, which can be seen as a warning sign for conservation. One hundred five non-native fish species were recorded in the Upper Parana ecoregion, which has the highest number of dams in the Neotropics (Nilsson et al., 2005; Agostinho et al., 2016). In the specific case of the upper Paraná basin, the high number of records of non-native species may be associated with the high number of studies in this region (see Table S2 in Supplementary Material), as well as the Itaipu Dam, because the formation of the Itaipu Reservoir suppressed Sete Quedas Falls, an effective natural barrier separating two ichthyofaunistic provinces, the Lower and Upper Paraná (Bonetto, 1986; Vitule et al., 2012). Thus, the removal of this barrier allowed that 60 fish species previously separated effectively colonize and disperse throughout the upper Paraná River basin (see Júlio Jr. et al., 2009 and Vitule et al., 2012 for more details). In this way, impoundment seems to be responsible for a great number of local introductions, especially in Brazil.

Others vectors of introduction were identified in our study, such as aquarium trade, sport fishing, and aquaculture, which contributed to the introduction of the greatest number of non-native fish species. These vectors were responsible for the more widespread spatial occurrence of introductions in the Neotropical region, presenting a lot of records of non-native fish species occurrences in several ecoregions. Moreover, these vectors are associated with the highest number of aliens’ occurrences. The aquarism is one of the five top vectors of introduction of non-native fish species (Ruiz et al., 1997). In North America, for example, among fish species intentionally transported, the majority were introduced in association with the ornamental fish industry (Rahel, 2007). In Neotropical region, the lack of regulations for the establishment and operation of ornamental fish farm, as well as for the aquarium trade has increased the invasion risks by ornamental freshwater fish (Magalhães & Jacobi, 2013; Mendoza et al., 2015).

Aquaculture has increased around the world to meet the food demand of the growing human population (e.g., Bartley, 2011). However, this activity is noted as one of the main vectors of introduction of non-native fish species in natural ecosystems (Casal, 2006; Ortega et al., 2015; Pelicice et al., 2017). We observed that aquaculture was an important vector of introduction of tilapias, rainbow trouts, and sea trouts in the Neotropical freshwaters. In Brazil, tilapias are the main species farmed by aquaculture (Lima et al., 2016), and recently, tilapia farming has been going through rapid expansion due to the Federal Government’s creation of aquaculture parks in public waters, mainly in reservoirs that allow the rearing of tilapias in cages (Lima et al., 2016). In addition, many studies have reported that O. niloticus, O. mykiss, and S. trutta are the most cultivated fish species in regional aquaculture south of the Neotropical region (Vitule et al., 2009; Benavente et al., 2015; Tagliaferro et al., 2015; Forneck et al., 2016) and are consequently more frequently introduced by this vector (Daga et al., 2016; Lima et al., 2016; Pelicice et al., 2017), especially by escapes from fish farms due to netpen or farm failure increase (Arismendi et al., 2009; Sepúlveda et al., 2013). Escapes from fish farms have been identified as an important contributor to the colonization of Neotropical freshwaters by invasive species (Orsi & Agostinho, 1999; Magalhães & Jacobi, 2013; Pelicice et al., 2017), because as the number of individuals released increases, the propagule pressure also increases (Lockwood et al., 2005), and thus, increases the probability of species establishment in the invaded environment (Lockwood et al., 2005; Simberloff, 2009).

In summary, studies of non-native freshwater fish species in the Neotropics have increased significantly in recent decades and are likely to continue to follow this trend in the coming years. In this sense, Brazil plays a fundamental role given its great importance to global biodiversity and the occurrence of several non-native fish species in its watersheds. Hence, countries in the Neotropics, especially Brazil, must adopt measures, such as restriction and control for some species with high potential for invasion and investment in technologies to avoid escapes, in order to control the introduction of non-native fish species (Lima Junior et al., 2015; Azevedo-Santos et al., 2017; Padial et al., 2017). In addition, we emphasize that the construction of dams, when natural barriers are removed, and sport fishing are the main vectors for introduction of extralimital species, while the aquarium trade and aquaculture were important vectors for introduction of alien species, mainly associated with widespread spatial. We expect that the knowledge summarized in this study may contribute to preventing new introductions and help curb the further spread of established non-native fish species.

References

Abell, R., M. L. Thieme, C. Revenga, M. Bryer, M. Kottelat, N. Bogutskaya, B. Coad, N. Mandrak, S. C. Balderas, W. Bussing, M. L. J. Stiassny, P. Skelton, G. R. Allen, P. Unmack, A. Naseka, R. Ng, N. Sindorf, J. Robertson, E. Armijo, J. V. Higgins, T. J. Heibel, E. Wikramanayake, D. Olson, H. L. López, R. E. Reis, J. G. Lundberg, M. H. S. Pérez & P. Petry, 2008. Freshwater ecoregions of the world: a new map of biogeographic units for freshwater biodiversity conservation. BioScience 58: 403–414.

Agostinho, A. A., L. Rodrigues, L. C. Gomes, S. M. Thomaz & L. E. Miranda, 2004. Structure and functioning of the Paraná River and its floodplain: LTER-Site 6-(PELD-Sítio 6). EDUEM, Maringá.

Agostinho, A. A., S. M. Thomaz & L. C. Gomes, 2005. Conservation of the biodiversity of Brazil’s inland waters. Conservation Biology 19: 646–652.

Agostinho, A. A., F. M. Pelicice & L. C. Gomes, 2008. Dams and the fish fauna of the Neotropical region: impacts and management related to diversity and fisheries. Brazilian Journal of Biology 68: 1119–1132.

Agostinho, A. A., F. M. Pelicice, L. C. Gomes & H. F. Júlio Jr., 2010. Reservoir fish stocking: when one plus one may be less than two. Natureza & Conservação 8: 103–111.

Agostinho, A. A., L. C. Gomes, N. C. L. Santos, J. C. G. Ortega & F. M. Pelicice, 2016. Fish assemblages in Neotropical reservoirs: colonization patterns, impacts and management. Fisheries Research 173: 26–36.

Albert, J. S. & R. E. Reis, 2011. Historical Biogeography of Neotropical Freshwater Fishes. University of California Press, Los Angeles.

Arismendi, I., D. Soto, B. Penaluna, C. Jara, C. Leal & J. León-Muñoz, 2009. Aquaculture, non-native salmonid invasions and associated declines of native fishes in Northern Patagonian lakes. Freshwater Biology 54: 1135–1147.

Arlinghaus, R., S. J. Cooke, J. Lyman, D. Policansky, A. Schwab, C. Suski, S. G. Sutton & E. B. Thorstad, 2007. Understanding the complexity of catch-and-release in recreational fishing: an integrative synthesis of global knowledge from historical, ethical, social, and biological perspectives. Reviews in Fisheries Science 15: 75–167.

Azevedo-Santos, V. M., O. Rigolin-Sá & F. M. Pelicice, 2011. Growing, losing or introducing? Cage aquaculture as a vector for the introduction of non-native fish in Furnas Reservoir, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Neotropical Ichthyology 9: 915–919.

Azevedo-Santos, V. M., P. M. Fearnside, C. S. Oliveira, A. A. Padial, F. M. Pelicice, D. P. Lima Jr., D. Simberloff, T. E. Lovejoy, A. L. B. Magalhães, M. L. Orsi, A. A. Agostinho, F. A. Esteves, P. S. Pompeu, W. F. Laurance, M. Petrere Jr., R. P. Mormul & J. R. S. Vitule, 2017. Removing the abyss between conservation science and policy decisions in Brazil. Biodiversity and Conservation 26: 1745–1752.

Bartley, D. M., 2011. Aquaculture. In Simberloff, D. & M. Rejmánek (eds), Encyclopedia of Biological Invasions. University of California Press, Led. London: 27–32.

Benavente, J. N., L. W. Seeb, J. E. Seeb, I. Arismendi, C. E. Hernández, G. Gajardo, R. Galleguillo, M. I. Cádiz, S. S. Musleh & D. Gomez-Uchida, 2015. Temporal genetic variance and propagule-driven genetic structure characterize naturalized rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) from a Patagonian Lake impacted by trout farming. PLoS ONE 10: e0142040.

Biagioni, R. C., A. R. Ribeiro & W. S. Smith, 2013. Checklist of non-native fish species of Sorocaba River Basin, in the State of São Paulo, Brazil. Check List 9: 235–239.

Bonetto, A. A., 1986. The Paraná river system. In Davies, B. R. & K. F. Walker (eds), The ecology of river systems. Dr. W. Junk Publishers, Dordrecht: 541–555.

Britton, J. R. & M. L. Orsi, 2012. Non-native fish in aquaculture and sport fishing in Brazil: economic benefits versus risks to fish diversity in the upper River Paraná Basin. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 22: 555–565.

Cambray, J. A., 2003. Impacton indigenus species biodiversity caused by the globalisation of alien recreatinal freshwater fisheries. Hydrobiologia 500: 217–230.

Casal, C. M. V., 2006. Global documentation of fish introductions: the growing crisis and recommendations for action. Biological Invasions 8: 3–11.

Clavero, M., V. Hermoso, E. Aparicio & F. N. Godinho, 2013. Biodiversity in heavily modified waterbodies: native and introduced fish in Iberian reservoirs. Freshwater Biology 58: 1190–1201.

Daga, V. S. & É. A. Gubiani, 2012. Variations in the endemic fish assemblage of a global freshwater ecoregion: associations with introduced species in cascading reservoirs. Acta Oecologica 41: 95–105.

Daga, V. S., F. Skóra, A. A. Padial, V. Abilhoa, É. A. Gubiani & J. R. S. Vitule, 2015. Homogenization dynamics of the fishassemblages in Neotropical reservoirs: comparing the roles of introduced species and their vectors. Hydrobiologia 746: 327–347.

Daga, V. S., T. Debona, V. Abilhoa, É. A. Gubiani & J. R. S. Vitule, 2016. Non-native fish invasions of a Neotropical ecoregion with high endemism: a review of the Iguaçu River. Aquatic Invasions 11: 209–223.

Diana, J., 2009. Aquaculture production and biodiversity conservation. BioScience 59: 27–38.

Dudgeon, D., A. H. Arthington, M. O. Gessner, Z. Kawabata, D. J. Knowler, C. Lévêque, R. J. Naiman, A. H. Prieur-Richard, D. Soto, M. L. Stiassny & C. A. Sullivan, 2006. Freshwater biodiversity: importance, threats, status and conservation challenges. Biological Reviews 81: 163–182.

Ellender, B. R. & O. L. F. Weyl, 2014. A review of current knowledge, risk and ecological impacts associated with non-native freshwater fish introductions in South Africa. Aquatic Invasions 9: 117–132.

Eschemeyer, W. N. & J. Fong, 2017. Species by family/subfamily in the catalog of fishes. California Academy of sciences, San Francisco. [electronic version: http://researcharchive.calacademy.org/research/ichthyology/catalog/SpeciesByFamily.asp]. Accessed 31 Jan 2017.

Fausch, K. D., 2007. Introduction, establishment and effects of non-native salmonids: considering the risk of rainbow trout invasion in the United Kingdom. Journal of Fish Biology 71: 1–32.

Forneck, S. C., F. M. Dutra, C. E. Zacarkim & A. M. Cunico, 2016. Invasion risks by non-native freshwater fishes due to aquaculture activity in a Neotropical stream. Hydrobiologia 773: 193–205.

Frehse, F. A., R. R. Braga, G. A. Nocera & J. R. S. Vitule, 2016. Non-native species and invasion biology in a megadiverse country: scientometric analysis and ecological interactions in Brazil. Biological Invasions 18: 3713–3725.

Fugi, R., K. D. G. Luz-Agostinho & A. A. Agostinho, 2008. Trophic interaction between an introduced (peacock bass) and a native (dogfish) piscivorous fish in a Neotropical impounded river. Hydrobiologia 607: 143–150.

Gubiani, É. A., V. A. Frana, A. L. Maciel & D. Baumgartner, 2010. Occurrence of the non-native fish Salminus brasiliensis (Cuvier, 1816), in a global biodiversity ecoregion, Iguaçu River, Paraná River basin, Brazil. Aquatic Invasions 5: 223–227.

Havel, J. E., C. E. Lee & J. M. Z. Zanden, 2010. Do reservoirs facilitate invasions into landscapes? BioScience 55(6): 518–525.

Havel, J. E., K. E. Kovalenko, S. M. Thomaz, S. Amalfitano & L. B. Kats, 2015. Aquatic invasive species: challenges for the future. Hydrobiologia 750: 147–170.

I3N Brazil Invasive Alien Species Database, 2017. http://i3n.institutohorus.org.br/www. The Horus Institute for Environmental Conservation and Development. Accessed 06 Sep 2017.

International Union for Conservation of Nature-IUCN, 2017. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.1 [http://www.iucnredlist.org]. Accessed 02 Feb 2017.

Jackson, D. A., P. R. Peres-Neto & J. D. Olden, 2001. What controls who is where in freshwater fish communities – the roles of biotic, abiotic, and spatial factors. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 58: 157–170.

Johnson, P. T. J., J. D. Olden & M. J. V. Zanden, 2008. Dam invaders: impoundments facilitate biological invasions into freshwaters. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 6: 357–363.

Júlio Jr., H. F., C. Dei Tós, A. A. Agostinho & C. S. Pavanelli, 2009. A massive invasion of fish species after eliminating a natural barrier in the upper rio Paraná basin. Neotropical Ichthyology 7: 709–718.

Kerr, S. J. & K. K. Kamke, 2003. Competitive fishing in freshwaters of North America: a survey of Canadian and U. S. jurisdictions. Fisheries 28: 26–31.

Lewinsohn, T. M. & P. I. Prado, 2005. Quantas espécies há no Brasil? Megadiversidade 1: 36–42.

Lima Junior, D. P., A. L. B. Magalhães & J. R. S. Vitule, 2015. Dams, politics and drought threat: the march of folly in Brazilian freshwaters ecosystems. Natureza & Conservação 13: 196–198.

Lima, L. B., F. J. Oliveira, H. C. Giacomini & D. P. Lima Jr., 2016. Expansion of aquaculture parks and the increasing risk of non-native species invasions in Brazil. Reviews in Aquaculture. https://doi.org/10.1111/raq.12150.

Lockwood, J. L., P. Cassey & T. Blackburn, 2005. The role of propagule pressure in explaining species invasions. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 20: 223–28 Magalhães, A. L. B. & C. M. Jacobi, 2013. Invasion risks posed by ornamental freshwater fish trade to southeastern Brazilian rivers. Neotropical Ichthyology 11: 433–441.

Magalhães, A. L. B. & C. M. Jacobi, 2013. Invasion risks posed by ornamental freshwater fish trade to southeastern Brazilian rivers. Neotropical Ichthyology 11: 433–441.

Magalhães, A. L. B. & C. M. Jacobi, 2017. Colorful invasion in permissive Neotropical ecosystems: establishment of ornamental non-native poeciliids of the genera Poecilia/Xiphophorus (Cyprinodontiformes: Poeciliidae) and management alternatives. Neotropical Ichthyology 15: e160094.

Mendoza, R., S. Luna & C. Aguilera, 2015. Risk assessment of the ornamental fish trade in Mexico: analysis of freshwater species and effectiveness of the FISK (Fish Invasiveness Screening Kit). Biological Invasions 17: 3491–3502.

Myers, N., R. A. Mittermeier, C. G. Mittermeier, G. A. B. da Fonseca & J. Kent, 2000. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403: 853–858.

Nilsson, C., C. A. Reidy, M. Dynesius & C. Revenga, 2005. Fragmentation and flow regulation of the world’s large river systems. Science 308: 405–408.

Orsi, M. L. & A. A. Agostinho, 1999. Introdução de peixes por escape acidental de tanques de cultura em rios da bacia do Rio Paraná. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 16: 557–560.

Ortega, J. C. G., H. F. Júlio Jr., L. C. Gomes & A. A. Agostinho, 2015. Fish farming as the main driver of fish introductions in Neotropical reservoirs. Hydrobiologia 746: 147–158.

Ota, R. R., H. J. Message, W. J. da Graça & C. S. Pavanelli, 2015. Neotropical Siluriformes as a model for insights on determining biodiversity of animal groups. PLoS ONE 10: e0132913.

Padial, A. A., A. A. Agostinho, V. M. Azevedo-Santos, F. A. Frehse, D. P. Lima Jr., A. L. B. Magalhães, R. P. Mormul, F. M. Pelicice, L. A. V. Bezerra, M. L. Orsi, M. Petrere Jr. & J. R. S. Vitule, 2017. The ‘‘Tilapia Law’’ encouraging non-native fish threatens Amazonian River basins. Biodiversity and Conservation 26: 243–246.

Padilla, D. K. & S. L. Williams, 2004. Beyond ballast water: aquarium and ornamental trades as sources of invasive species in aquatic ecosystems. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2: 131–138.

Pascual, M. A., P. Bentzen, C. R. Riva, G. Mackey, M. T. Kinnison & R. Walker, 2001. First documented case of anadromy in a population of introduced rainbow trout in Patagonia, Argentina. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 130: 53–67.

Peixer, J. & M. Petrere Jr., 2009. Sport fishing in Cachoeira de Emas in Mogi-Guaçu River, State of São Paulo, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Biology 69: 1081–1090.

Pelicice, F. M., J. R. S. Vitule, D. P. Lima Jr., M. L. Orsi & A. A. Agostinho, 2014. A serious new threat to Brazilian freshwater ecosystems: the naturalization of nonnative fish by decree. Conservation Letters 7: 55–60.

Pelicice, F. M., V. M. Azevedo-Santos, J. R. S. Vitule, M. L. Orsi, D. P. Lima Jr., A. L. B. Magalhães, P. S. Pompeu, M. Petrere Jr. & A. A. Agostinho, 2017. Neotropical freshwater fishes imperilled by unsustainable policies. Fish and Fisheries 18(6): 1119–1133.

Rahel, F. J., 2007. Biogeographic barriers, connectivity and homogenization of freshwater faunas: it’s a small world after all. Freshwater Biology 52: 696–710.

Regalado, A., 2010. Brazilian science: riding a gusher. Science 330: 1306–1312.

Reis, R. E., J. S. Albert, F. Di Dario, M. M. Mincarone, P. Petry & L. A. Rocha, 2016. Fish biodiversity and conservation in South America. Journal of Fish Biology 89: 12–47.

Ribeiro, V. R., P. R. L. da Silva, É. A. Gubiani, L. Faria, V. S. Daga & J. R. S. Vitule, 2017. Imminent threat of the predator fish invasion Salminus brasiliensis in a Neotropical ecoregion: eco-vandalism masked as an environmental project. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation 15: 132–135.

Richardson, D. M. & P. Pyšek, 2008. Fifty years of invasion ecology – the legacy of Charles Elton. Diversity and Distributions 14: 161–168.

Ruaro, R., R. P. Mormul, É. A. Gubiani, P. A. Piana, A. M. Cunico & W. J. da Graça, 2018. Non-native fish species are related to the loss of ecological integrity in Neotropical streams: a multimetric approach. Hydrobiologia. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-018-3542-y.

Ruiz, G., J. Carlton, E. Grosholz & A. H. Hines, 1997. Global invasions of marine and estuarine habitats by non-indigenous species: mechanisms, extent and consequences. Integrative and Comparative Biology 37: 621–632.

Sepúlveda, M., I. Arismendi, D. Soto, F. Jara & F. Farias, 2013. Escaped farmed salmon and trout in Chile: incidence, impacts, and the need for an ecosystem view. Aquaculture Environment Interactions 4: 273–283.

Simberloff, D., 2009. The role of propagule pressure in biological invasions. Annual Reviews in Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 40: 91–102.

Simberloff, D. & M. Rejmánek, 2011. Encyclopedia of biological invasions. University of California Press, California.

Simberloff, D., J. L. Martin, P. Genovesi, V. Maris, D. A. Wardle, J. Aronson, F. Courchamp, B. Galil, E. García-Berthou, M. Pascal, P. Pyšek, R. Sousa, E. Tabacchi & M. Vilá, 2013. Impacts of biological invasions: what’s what and the way forward. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 28: 58–66.

Singh, A. K. & W. S. Lakra, 2011. Risk and benefit assessment of alien fish species of the aquaculture and aquarium trade into India. Reviews in Aquaculture 3: 3–18.

Tagliaferro, M., I. Arismendi, J. Lancelotti & M. Pascual, 2015. A natural experiment of dietary overlap between introduced Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and native Puyen (Galaxias maculatus) in the Santa Cruz River, Patagonia. Environmental Biology of Fishes 98: 1311–1325.

Taylor, B. W. & R. E. Irwin, 2004. Linking economic activities to the distribution of exotic plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101: 17725–17730.

Toussaint, A., N. Charpin, S. Brosse & S. Villéger, 2016. Global functional diversity of freshwater fish is concentrated in the Neotropics while functional vulnerability is widespread. Scientific Reports 6: 1–9.

Vitule, J. R. S., C. A. Freire & D. Simberloff, 2009. Introduction of non-native can certainly be bad. Fish and Fisheries 10: 98–108.

Vitule, J. R. S., F. Skóra & V. Abilhoa, 2012. Homogenization of freshwater fish faunas after the elimination of a natural barrier by a dam in Neotropics. Diversity and Distributions 18: 111–120.

Vitule, J. R. S., H. Bornatowski & C. A. Freire, 2014. Extralimital introductions of Salminus brasiliensis (Cuvier, 1816) (Teleostei, Characidae) for sport fishing purposes: a growing challenge for the conservation of biodiversity in Neotropical aquatic ecosystems. BioInvasions Records 3: 291–296.

Vitule, J. R. S., A. P. L. da Costa, F. A. Frehse, L. A. V. Bezerra, T. V. T. Occhi, V. S. Daga, A. A. Padial, et al., 2017. Comments on ‘Fish biodiversity and conservation in South America by Reis et al. (2016)’. Journal of Fish Biology 90: 1182–1190.

Zambrano, L., E. Martínez-Meyer, N. Menezes & A. T. Peterson, 2006. Invasive potential of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) and Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) in American freshwater systems. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 63: 1903–1910.

Acknowledgements

We thank Augusto Frota (PEA/UEM) for making the maps. R. Ruaro and D. Cavalli are grateful to the “Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico” (CNPq/Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia, Inovações e Comunicações) for their scholarships. A.C.A. Eichelberger, R.F. Bogoni, and A.D. Lira are grateful to the “Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior” (CAPES/Ministério da Educação) for their scholarships.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Guest editors: John E. Havel, Sidinei M. Thomaz, Lee B. Kats, Katya E. Kovalenko & Luciano N. Santos / Aquatic Invasive Species II

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gubiani, É.A., Ruaro, R., Ribeiro, V.R. et al. Non-native fish species in Neotropical freshwaters: how did they arrive, and where did they come from?. Hydrobiologia 817, 57–69 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-018-3617-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-018-3617-9