Abstract

How do concentration and competition in the European banking sector affect lending relationships between small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) and their banks? Recent empirical evidence suggests that concentration and competition capture different characteristics of banking systems. Using a unique dataset on SMEs for selected European regions, we empirically investigate the impact of increasing concentration and competition on the number of lending relationships maintained by SMEs. We find that competition has a positive effect on the number of lending relationships, weak evidence that concentration reduces the number of banking relationships and weak persistent evidence that they tend to offset each other.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

An accelerating number of mergers and acquisitions (M&As) over the past decade, and changes in the regulatory and institutional environment financial institutions operate in have affected the structure and competitive nature of banking markets. As the industry continues to consolidate, relationships between banks and their customers may be altered, possibly impacting on the provision of banking services. This is of particular concern to small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in Europe,Footnote 1 since they predominately depend on bank financing.

Numerous studies focus on the nature of relationships established by different types of banks (Berger et al. 2008), the determinants of the role of banks (Elsas 2005; Harhoff and Körting 1998), the benefits of bank-borrower relationships (Berger and Udell 2006; Ongena and Smith 2001; Petersen and Rajan 1995), the effect of competition on bank orientation (Degryse and Ongena 2007), and the number of relationships maintained by large corporations (Ongena and Smith 2000). However, the literature has not yet investigated the determinants of the number of bank relationships maintained by SMEs. Moreover, how do bank market structure and bank conduct affect the number of bank relationships? Since the impact of banking competition and industry consolidation on the ability of SMEs to attract finance is one of the most important research and policy issues of our day, we seek to contribute to this discussion with this paper.

In Europe, 23 million SMEs account for 99% of all companies, employ around 75 million people, and generate one in every two new jobs.Footnote 2 Given their important role, institutional changes in banking systems give rise to major policy concerns. Our empirical enquiry focuses on SMEs since information-based intermediation theory (Diamond 1984; Stein 2002) suggests that SMEs are less likely to have as many bank relationships as have large corporations.

First, SMEs and their lenders frequently belong to the same socio-economic setting, which reduces information asymmetries, eases monitoring, and reduces costly information acquisition about borrowers. This implies that opaque firms like SMEs find it optimal to borrow from one bank. However, ‘hold up’ problems arise with repeated lending from only one bank if the relationship lender extracts rents from the firm (Sharpe 1990; Rajan 1992). Thus, having a limited number of bank relationships is optimal for SMEs, this also reduces the probability of being denied credit (Thakor 1996; von Thadden 1995). Second, empirical evidence indicates that the number of bank relationships is increasing in firm size (e.g., Petersen and Rajan 1994; Berger and Udell 1995; Ongena and Smith 2000). Third, another reason why SMEs are less likely to maintain many bank relationships is related to their typically rural locations. Sophisticated intermediaries are rarely available to finance SMEs in such areas because they do not demand diversified supplies of financial services (Ferri and Messori 2000). Finally, SMEs are less likely to maintain relationships with larger institutions as the lending technology required for processing ‘soft’ information is less well developed in larger banks (Williamson 1998; Stein 2002; Berger and Udell 2002; Berger et al. 2005). The latter two arguments indicate that SMEs have a smaller pool of banks to obtain financing from.

Our analysis is also related to the literature on financial system architecture. First, while Staikouras and Koutsomanoli-Fillipaki (2006) and Schaeck and Cihak (2007) report increasing degrees of competition in European banking systems, Goddard et al. (2007) observe a wave of consolidation across European banking systems resulting from increasing M&As. This raises fears that consolidation decreases the number of banks specialising in relationship banking with possibly detrimental welfare effects for local firms, especially SMEs, these firms’ access to credit, and, ultimately, economic growth.Footnote 3 As a result, positive effects for the provision of banking services arising from increased competition in banking systems may be offset by higher degrees of concentration.

As part of our investigation, we seek to answer this question because the literature on the effect of market structure and competition on SME financing offers two competing theories: Whereas proponents of the ‘market power’ notion (Elsas 2005; Boot and Thakor 2000, Ongena and Smith 2000) contend that concentration decreases firms access to credit, advocates of the ‘information hypothesis’ argue that less competition improves credit availability (Petersen and Rajan 1995). We propose that these findings are due to the way competition is determined in studies that proxy competition with concentration measures. This assertion places our paper into a growing body of work by Claessens and Laeven (2004), and Schaeck et al. (2009) indicating that concentration is a poor proxy for competition and that concentration and competition describe different characteristics of banking systems.

We focus on Europe since EU banking systems have been undergoing significant changes following the launch of the Single Market Programme, and transition to the Euro. While these developments are aimed at creating a level playing field for competition, the banking landscape is still largely influenced by linguistic and cultural differences that thwart setting up banking relationships across national boundaries. Such impediments may be due to ‘exogenous economic borders’, i.e. legal origin and system, supervisory and corporate governance practices, language and culture, and ‘endogenous economic borders’. These are information-based, and arise from bank-firm relationships, adverse selection, and information sharing between intermediaries (Buch 2001).

The purpose of our paper is to extend the literature on bank relationships in two ways: First, this work is to the best of our knowledge the first analysis of the determinants of the number of SME-bank financing relationships based on European data. Second, to disentangle effects from competition and concentration, we simultaneously consider effects arising from competition and concentration for SME-bank relationships.

We obtain data from the Centre for Business Research of the University of Cambridge regarding scope and scale of the relationship between 361 SME borrowers and their banks from the south of Germany, and the south-east of the UK. These regions are traditionally characterised by areas rich in innovative SMEs as well as local and regional banks, which are the main source of financing for SMEs.Footnote 4 This dataset provides an excellent setting to conduct our empirical investigation as the survey data can be matched with local bank market data. This is beneficial since we anticipate socio-economic factors to be paralleled by local financial systems.

Three key findings emerge from our analysis: (1) Competition has a positive influence on the number of bank financing relationships maintained by SMEs. (2) Concentration has a weak negative influence on the number of banking relationships and weakly offsets the positive effects of competition on the number of banking relationships. (3) The number of relationships consistently increases in firm size. (4) Having a supportive and helpful main bank has a strong decreasing effect on the probability of maintaining multiple banking relationships.

We proceed as follows: In Section 2, we describe the dataset. We present empirical results in Section 3. Section 4 contains sensitivity checks. Section 5 concludes.

2 Data and variables

We explain in Section 2.1 the survey data. Section 2.2 presents the motivation and description for the choice of the firm, bank, and market-specific variables.

2.1 Survey data

Our primary source for firm information is the Survey of the Financing of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises in Western Europe conducted in 2001. This survey was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council and emphasises the transformation of regional and local banking systems in Europe. The survey initially focuses on the financing of SMEs in three different regions of Europe: Emilia-Romagna in Italy, Bavaria in Southern Germany, and the south-east of England. Since some of our key explanatory variables are, however, not reported for Italy, we hone in on the information provided for Germany and the UK.

The survey is based on a questionnaire that contains 191 questions.Footnote 5 The questionnaire yielded 247 responses for the UK and 114 for Germany. Questions from the survey cover a variety of topics including the main markets serviced, firm activities, the type and source of finance used, whether firms have used bank finance, the SME’s perception of how easy it is to obtain bank finance, and the bank’s attitude towards the firm. Moreover, the questionnaire also provides details about the nature of the SMEs’ type of business, size, and firm growth.

We present descriptive statistics in Table 1. In terms of the dependent variable, it is noteworthy to mention that our definition of banking relationship extends to financing that is intended for, inter alia, acquisition investment, cash-flow, tax payments, product development, purchases of fixed assets, funding of R&D, management buy-ins/buy-outs, and for enabling the SME to remain a going concern. It excludes SMEs having a relationship solely through having a checking or savings account with a bank. This definition reflects that the intermediation literature focuses on the role of banks as delegated monitors for lending activities (Diamond 1984).

The UK makes up 70% of the sample with Germany accounting for 30%. Table 1 suggests that firms in the UK tend to maintain a lower number of banking relationships than do SMEs in Germany. We can also see that German SMEs tend to rely more on bank finance than their UK counterparts. Finally, German SMEs are located nearer to their creditor banks and the German market seems less concentrated and also less competitive.

2.2 Explanatory variables Footnote 6

2.2.1 Bank market structure variables

To test our hypothesis that concentration and competition among banks have independent effects for the number of financing relationships, we use the Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI), calculated as the sum of the squared market shares. This index is widely used as a measure to describe concentration in banking markets (Alegria and Schaeck 2008).

To disentangle the effects arising from concentration and competition, we include the Panzar and Rosse (1987) H-Statistic to gauge competition. Claessens and Laeven (2004) argue that H is a more appropriate measure for the degree of competition than previously used proxies of competition. This statistic is considered superior to other measures of competition since it is formally derived from profit-maximising equilibrium conditions. It overcomes criticism put forward against concentration ratios that are frequently used to infer competition as it does not require assumptions about the market.Footnote 7 The H-Statistic gauges market power by the extent to which changes in factor input prices translate into equilibrium revenues. Vesala (1995) has shown that higher of H signify more competition. We anticipate that concentration is inversely related to the number of relationships maintained by SMEs whereas the H-Statistic is expected to be positively related. Appendix II presents the detailed calculations for the H-Statistic, summary statistics for the H-Statistic and the HHI for each local market and details about the interrelation between H and HHI.

2.2.2 Control variables

To capture organisational form and distinguish between firm type, we include a dummy variable Firm Type that takes on the value one if the SME is private or zero otherwise. Public firms have better access to capital markets and this might impact the number of bank relationships. As in Degryse and van Cayseele (2000), we include this variable as the degree of informational asymmetry varies with organisational form due to agency conflicts between owners, managers, and creditors. We assume this variable enters with a negative sign.

We employ Size (employees) as a measure of firm size as we expect SMEs to maintain more financing relationships as they increase in size. Indeed, previous work highlights that size is positively correlated with the number of bank relationships (Petersen and Rajan 1994). Our survey data do not provide actual figures for firm size in terms of the number of employees. Rather, the SMEs are classified into five categories, whereby higher values indicate greater size. The descriptive statistics show that German firms tend to be larger than their British counterparts.

The Amount of bank finance used is employed to assess how much the SME depends on financing from banks. We expect this variable to enter with a positive sign because greater dependency on bank financing is likely to be reflected in a larger number of banking relationships.

Distance determines whether proximity between borrower and lender has any impact on the number of relationships. Given that SMEs are considered opaque and given that the collection of ‘soft’ information is facilitated by geographic proximity, we anticipate that distance will be positively related to the number of bank relationships.

The variable Growth aims to capture the dynamic development of the firm and we assume a growing SME to be more likely to diversify its lending relationships. Moreover, Detragiache et al. (2000) have shown that larger firms may have to rely on multiple banking to allow banks to diversify firm-specific credit risk.

Finally, we also exploit information in the survey about the firm’s perception of the main bank’s Attitude and how easy it is to obtain bank finance. We code the former variable as a dummy taking on the value one if the firm considers the main bank’s attitude as ‘supportive’ or ‘helpful’ and zero otherwise. We anticipate that this dummy variable enters with a negative sign as a helpful and supportive main bank decreases the probability of setting up multiple lending relationships. We use an index variable Easiness to obtain finance to account for the firm’s subjective perception of financing constraints. This index is increasing in the degree of difficulty to attract bank financing and we expect it to enter the regression model with a positive sign because a firm that perceives it difficult to request financing from its main bank is likely to turn to multiple institutions to meet its financing needs.

3 Results

We use multinomial logit regressions to examine the determinants of the number of bank relationships because our dependent variable takes on discrete values: We code the dependent variable as one if the SME maintains one lending relationship, two for two lending relationship, three for three lending relationships, and four for four different banking relationships. In our empirical setup, we exclude firms that maintain no lending relationship with banks because these firms are special cases that would never choose to establish bank lending relationships in the first place. We present the main regression results in Table 2. The reported coefficients are relative to the omitted category of maintaining one multiple lending relationships. That is, positive coefficients indicate higher probabilities of maintaining two, three, or four different relationships.

3.1 Concentration and competition

Model I in Table 2 is our canonical model. To examine the effects of concentration and competition, we include the HHI, and the H-Statistic in this specification. In Model II, we furthermore account explicitly for firm growth, and subsequently we also include an interaction term between HHI and the H-Statistic in Model III. The objective of these regressions is to establish whether concentration and competition capture the same characteristics of banking systems, or, if they independently affect the number of bank relationships. If so, this suggests that it is inappropriate to proxy competition in banking systems by looking at measures of market structure.

The HHI enters in Model I negatively and significantly for two of the three possible nodes. This finding is in line with previous work by Ongena and Smith (2000) in the sense that concentration reduces the number of financing relationships. Moreover, if the banking market is concentrated, and if an SME’s existing relationship is experiencing any difficulties, then it will be harder to obtain services when the number of players in the market is limited. To illustrate the economic significance of the marginal effects of increased market concentration on the number of lending relationships, we compute the effect of increasing the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) by one standard deviation across the three nodes with the other variables being evaluated at their mean. A one standard deviation increase (0.07) in the HHI reduces the estimated probability of having two or more relationships relative to having only one relationship by 2%. Similarly, the estimated probability of having three or four relationships, relative to having one, declines by 28 and 21% respectively.

By contrast, our measure of competition, the H-Statistic, exhibits a consistently positive and significant effect on the number of bank relationships. This finding indicates that SMEs maintain more bank relationships in more competitive systems. Greater competition widens the spectrum of banks to choose from. Moreover, SMEs that might be experiencing difficulties could potentially find it easier to develop new bank relationships in more competitive environments. Likewise, banks might also start providing better terms to clients in a bid to attract further business in a competitive environment. Our results concerning HHI and the H-Statistic are intuitive: Firms operating in concentrated markets can only choose between a few providers of financing and therefore have fewer bank relationships, whereas competition increases the number of bank relationships. This result provides evidence that independent effects arise from market structure and competition. Our finding suggests that competition should not be proxied by the degree of concentration.

We can evaluate the marginal effects of increasing the H-Statistic by one standard deviation on the three nodes whilst holding the other variables constant at their mean. Increasing the H-Statistic by one standard deviation (0.08) increases the probability of having two lending relationships relative to having just one by 3%. This effect is greater when we look at the probability of having three or four lending relationships relative to having just one. The probability of having three or four relationships increases to 24% and 31% respectively when we increase the H-Statistic by one standard deviation.

To explicitly account for the growth potential of the firms in the survey, we control in Model II for this important factor as suggested in previous work by Detragiache et al. (2000). The inclusion of this additional factor does not substantially alter our inferences with respect to the effects of HHI and H-Statistic while the growth variable itself remains insignificant. We therefore drop this variable in our subsequent regressions.

Model III incorporates an interaction term between the H-Statistic and the HHI to investigate possible nonlinearities arising from these two effects. For instance, a negative coefficient for the interaction term indicates that the higher the degree of competition, the lower the effect of concentration on the number of bank relationships (and vice versa). Model III shows that the H-Statistic retains its sign and significance when the interaction term is included. The interaction term enters negatively and significantly for the decision to maintain different banking relationships with two different banks, implying that the effect of H on the number of relationships is greater in less concentrated markets. Thus, our results suggest that increased concentration can dampen the positive effects of competition, and the marginal impact of this dampening is strongest in more highly competitive markets. However, this effect is no longer significant beyond the establishment of the second different banking relationship. Moreover, there is no evidence for a decline in credit supply in the long run to small firms after banking consolidation, suggesting that small and medium sized borrowers manage to increase their lending relationships after bank mergers (Bonaccorsi di Patti and Gobbi 2007).

3.2 Control variables

Among the control variables in Table 2, we find that being a private firm as indicated by the Firm Type variable significantly decreases the number of bank relationships, whereas we observe a significantly positive effect of firm Size on the number of lending relationships. Both results are in line with our expectations. Among the two bank variables we find that a helpful and supportive attitude of the main bank reduces the likelihood of maintaining banking relationships with multiple banks and there is also some evidence that difficulties to obtain bank financing translate into an increased probability of approaching multiple lenders.

4 Sensitivity tests

We report on robustness tests in Table 3 and 4. Here, we investigate sample selectivity, if our results are affected by the way competition is measured, and if the estimation method affects our inferences. In a further test we examine if endogeneity of some of our explanatory variables drives our results. In these regressions, we only report and discuss the results for the H-Statistic and the HHI for space constraints.Footnote 8

In Panel A of Table 3, we firstly constrain the sample to German firms to examine sample selectivity, and especially the possibility that our results are driven by firms from the UK which dominate the sample. Whereas in Model I we constrain the sample to German firms, in Model II we constrain the sample to UK firms only. This test confirms the inferences from our canonical model. We consistently find a negative and highly significant effect of the concentration index and a consistently positive and highly significant effect of competition on the number of bank lending relationships.Footnote 9

Since our inferences critically depend on the way competition is measured, we use an alternative method to compute the H-Statistic in Table 4 Panel B Model III. This H-Statistic is calculated using the ratio of total revenue to total assets instead of the ratio of interest revenue to total assets as dependent variable. The alternative H-Statistic enters again positively and significantly for two of the three nodes, suggesting that the way H is calculated does not materially affect the inferences. In this setup, market structure as measured by the HHI ceases to enter with a significant sign, indicating that concentration plays a less important role for the decision to set up multiple lending relationships.

In Model IV we remove all control variables to examine potential sources of endogeneity. For example, maintaining a larger number of banking relationships may increase the Distance between the bank and the firm and thus give rise to reverse causality. Model IV shows that when the alternative H statistic based on total revenue is used and all control variables are removed we still observe a negative and highly significant effect of the concentration index coupled with a positive and highly significant effect of competition on the number of bank lending relationships.

In Model V we make use of country dummy variables. A dummy for SMEs in the UK is included and we omit the dummy for Germany to avoid perfect collinearity. We use this procedure to account for country-specific factors such as the regulatory and institutional environment. This is an important robustness test. For example, if inclusion of these dummy variables renders the competition and concentration variables insignificant, this could be a sign that these variables capture country-specific rather than regional bank market characteristics. However, the results for the H-Statistic are again confirmed in this setup, while the effect of the HHI is only significant in one of the three possible outcomes.

Next, the number of banking relationships may affect the Amount of bank finance used.Footnote 10 We therefore remove this variable in Model VI to examine the potential source of endogeneity. We continue to find a positive and significant effect of competition on the number of lending relationships for all of the three outcomes. However, market structure is rendered insignificant in this setup. Throughout our analysis the H-Statistic, in stark contrast to the HHI, is the more consistently significant variable. This suggests that the effect of competition is more important than the effect of concentration.

In a final test, we use a linear probability model to assess the robustness of our inferences towards our estimation method. The key findings from our canonical model above are again corroborated in Model VII, and we continue to find a negative and significant effect of the HHI and a positive and significant effect of the H-Statistic.

In sum, we consistently observe a positive and significant effect of local banking competition on the number of lending relationships maintained by SMEs in Germany and in the UK. At the same time, we also find some evidence for a negative effect of concentration in local banking markets on the number of lending relationships. These findings lend support to our key hypothesis that market structure and competition are different characteristics of banking systems and that competition cannot appropriately be captured by looking at measures of concentration such as the HHI.

5 Concluding remarks

Against a background of increasing concentration and competition in European banking systems, we seeks to establish the effect of such changes on the determinants of the number of SME bank financing relationships in two European regions.

Employing a unique dataset from a cross-sectional survey of SMEs, we uncover independent effects arising from competition and concentration on the number of lending relationships maintained by SMEs in Germany and in the UK. These enterprises maintain more financing relationships in more competitive banking systems, a result that is consistent with the ‘market power’ hypothesis in the literature.

Our results substantiate the assertion in recent empirical work that competition and concentration describe different characteristics of banking systems. Firstly, the findings underscore that the number of bank relationships increases with more competition, secondly that the number of bank relationships decreases with more concentration and finally competition and concentration have offsetting effects on the number of banking relationships maintained by SMEs. In that sense, our results support the inferences in recent work by Schaeck et al. (2009) that national and local measures of market structure and competition may not necessarily yield identical outcomes.

These findings bear important policy implications: The results imply that measures of market structure such as the HHI may be inappropriate proxies for the degree of competition in banking as we show that both structure and conduct tend to affect SMEs’ financing relationships in opposite directions. Whereas, policymakers are concerned about the adverse ramifications arising from consolidation in banking concerning the provision of banking services to SMEs, our results underscore the fact that competition in the banking system has a strong positive effect. Finally, removing barriers and obstacles that hamper setting up multiple bank relationships imposed on banks will enable SMEs to develop and mature by making use of more sophisticated financial services, thus ultimately promoting economic growth.

Data limitations concerning the comparatively small sample size suggest that our results have to be taken with a note of caution. Nonetheless, our findings complement a growing body of empirical work in the banking literature suggesting that concentration and competition describe different characteristics of banking systems.

Notes

The EU defines SMEs as enterprises that employ fewer than 250 people, have an annual turnover not exceeding €50 million, and/or annual balance sheet total not exceeding €43 million.

Observatory for European SMEs, Enterprise Directorate-General of the European Commission, (2004), Brussels.

Such developments have been extensively studied for the US, see, for instance, Berger and Udell (2002).

Further details regarding composition of these regions are provided in Martin et al. (2001).

The questionnaire is available from the authors on request.

We present definitions for the explanatory variables in Appendix I.

The definition of a banking market is likely to affect inferences regarding competition, when competition is inferred from concentration ratios. This is due to the fact that banking markets in small countries are likely to extend beyond a single nation’s borders and because large banks operate globally.

The full set of results including all control variables can be obtained from the authors upon request.

To investigate the large size of our coefficients in Panel A we re-ran our analysis with outliers for Germany and the UK removed. For a German sample of 39 and UK sample of 101 firms we obtain more normal sized coefficients and still obtain highly significant and same sign coefficients as reported here. Available on request from the authors.

We thank the editor and an anonymous referee for pointing this out.

Therefore, the magnitude of the H-Statistic can serve as a measure for the degree of competition, assuming that the bank faces a demand with constant elasticity and a Cobb-Douglas production technology (Vesala, 1995).

We are particularly indebted to Anna Bullock, Survey and Database Manager at the Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge for providing us with this data.

References

Alegria C, Schaeck K (2008) On measuring concentration in banking systems. Finance Res Lett 5:59–67. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2007.12.001

Berger AN, Udell G (1995) Relationship lending and lines of credit in small firm finance. J Bus 68:351–382. doi:10.1086/296668

Berger AN, Udell GF (2002) Small business credit availability and relationship lending: the importance of bank organisational structure. Econ J 112:F32–F53

Berger AN, Udell G (2006) A more complete conceptual framework for SME finance. J Bank Finance 30:2945–2966. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2006.05.008

Berger A, Miller NH, Petersen MA, Rajan RG, Stein J (2005) Does function follow organizational form? Evidence from the lending practices of large and small banks. J Financ Econ 76:237–269. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2004.06.003

Berger A, Klapper NLF, Martinez Peria MS, Zaidi R (2008) Bank ownership type and banking relationships. J Financ Intermed 17:37–62. doi:10.1016/j.jfi.2006.11.001

Bonaccorsi di Patti E, Gobbi G (2007) Winners or losers? The effects of banking consolidation on corporate borrowers. J Finance 62:669–695. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2007.01220.x

Boot AWA, Thakor AV (2000) Can relationship banking survive competition? J Finance 55:679–713

Buch CM (2001) Distance and international banking. Institute of World Economics WP, no. 1043, Kiel, Germany

Claessens S, Laeven L (2004) What drives bank competition? Some international evidence. J Money Credit Bank 36(3):563–583. doi:10.1353/mcb.2004.0044

Degryse H, Ongena S (2007) The impact of competition on bank orientation. J Financ Intermed 16:399–424. doi:10.1016/j.jfi.2007.03.002

Degryse H, van Cayseele P (2000) Relationship lending within a bank-based system: evidence from European small business data. J Financ Intermed 9:90–109. doi:10.1006/jfin.1999.0278

Detragiache E, Garella P, Guiso L (2000) Multiple versus single banking relationships: theory and evidence. J Finance 55:1133–1161. doi:10.1111/0022-1082.00243

Diamond D (1984) Financial Intermediation and delegated monitoring. Rev Econ Stud 51:393–414. doi:10.2307/2297430

Elsas R (2005) Empirical determinants of relationship lending. J Financ Intermed 14:32–57. doi:10.1016/j.jfi.2003.11.004

European Commission (2004) Observatory for European SMEs, Enterprise Directorate-General of the European Commission. Brussels

Ferri G, Messori M (2000) Bank-firm relationships and allocative efficiency in Northeastern and Central Italy and in the South. J Bank Finance 24:1067–1095. doi:10.1016/S0378-4266(99)00118-1

Goddard J, Molyneux P, Wilson OSJ, Tavakoli M (2007) European banking: an overview. J Bank Finance 31:1911–1935. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2007.01.002

Harhoff D, Körting T (1998) Lending relationships in Germany—empirical evidence from survey data. J Bank Finance 22:1317–1353. doi:10.1016/S0378-4266(98)00061-2

Martin R, Sunley D, Turner D (2001) The restructuring of local banking systems across Europe: Implications for regional business development. Cambridge Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge

Molyneux P, Lloyd-Williams DM, Thornton J (1994) Competitive conditions in European banking. J Bank Finance 18:445–459. doi:10.1016/0378-4266(94)90003-5

Ongena S, Smith DC (2000) What determines the number of Bank relationships? Cross country evidence. J Financ Intermed 9:25–56. doi:10.1006/jfin.1999.0273

Ongena S, Smith DC (2001) The duration of bank relationships. J Financ Econ 61:449–475. doi:10.1016/S0304-405X(01)00069-1

Panzar JC, Rosse JN (1987) Testing for monopoly equilibrium. J Ind Econ 35:443–456. doi:10.2307/2098582

Petersen MA, Rajan RG (1994) The benefits of firm-creditor relationships: evidence from small business data. J Finance 49:3–37. doi:10.2307/2329133

Petersen MA, Rajan RG (1995) The effect of credit market competition on lending relationships. Q J Econ 110:406–443. doi:10.2307/2118445

Rajan RG (1992) Insiders and outsiders: the choice between informed and arm’s-length debt. J Finance 47:1367–1400. doi:10.2307/2328944

Schaeck K, Cihak M (2007) Banking competition and capital ratios. IMF Working Paper 07/216, Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund

Schaeck K, Cihak M, Wolfe S (2009) Are competitive banking systems more stable? J Money Credit Bank (forthcoming).

Sharpe SA (1990) Asymmetric information, bank lending and implicit contracts: a stylized model of customer relationships. J Finance 45:1069–1087. doi:10.2307/2328715

Staikouras C, Koutsomanoli-Fillipaki A (2006) Competition and concentration in the new European banking landscape. Eur Financ Manag 12:443–482. doi:10.1111/j.1354-7798.2006.00327.x

Stein JC (2002) Information production and capital allocation: decentralized versus hierarchical firms. J Finance 57:1891–1921. doi:10.1111/0022-1082.00483

Thakor AV (1996) Capital requirements, monetary policy, and aggregate bank lending: Theory and empirical evidence. J Finance 51:279–324. doi:10.2307/2329310

Vesala J (1995) Testing for competition in banking: Behavioural evidence from Finland. Bank of Finland, Helsinki

von Thadden EL (1995) Long-term investments, short-term investment and monitoring. Rev Econ Stud 62:557–575. doi:10.2307/2298077

Williamson O (1998) Corporate finance and corporate governance. J Finance 43:567–591. doi:10.2307/2328184

Acknowledgements

We thank Bob DeYoung (the editor), an anonymous referee, Allen Berger (the discussant), Carlos Ramirez, and conference participants at the conference on “Mergers and Acquisitions of Financial Institutions” in Arlington, VA, for valuable comments and suggestions that considerably helped improve the paper. We also thank seminar and conference participants at the University of Southampton, and at the conference on “Small business banking and financing: a global perspective” in Cagliari, Italy. We are greatly indebted to Anna Bullock from the Centre for Business Research at University of Cambridge who provided us with additional data. Thanh Van Nguyen and Watcharee Corkill provided outstanding research assistance. All remaining errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix I: Definitions of explanatory variables

Variable | Description | Source |

Multi-banking relationships | Whether SME has 1,2, 3, or 4 bank relationship | Cambridge SME Survey |

Firm Type | Whether the SME is public or private company (1 = private, 0 otherwise). | Cambridge SME Survey |

Size (employees) | Firm size measured as an index variable that is increasing in the number of employees. The index takes the value of 1 if there are 1–9 employees; 2 if there are 10–19 employees; 3 if there are 20–49 employees; 4 if there are 50–99 employees and 5 if there are more than 100 employees. | Cambridge SME Survey |

Amount of bank finance used | This is an index variable that is increasing in the volume of bank financing. It takes on the value 1 if the firm used up to GBP99,999 (DEM337,999); 2 if GBP 100,000–249,999 (DEM338,000–843,999); 3 if GBP250,000–499,999 (844,0000–1,687,999); 4 if GBP 500,000–999,999 (DEM1,688,000–3,374,999); and 5 if GBP 1 m and over (DEM 3,375,000 and over). | Cambridge SME Survey |

Easiness to obtain finance | This index is increasing in the degree of difficulty to attract bank financing. It takes on the value 1 if the firm considers obtaining financing ‘very easy’; 2 if the firm considers it ‘fairly easy’; 3 if the firm considers it ‘fairly difficult’; or 4 if the firm considers obtaining financing ‘very difficult’. | Cambridge SME Survey |

Distance | Distance of bank from firm. Variable takes value of 1 if <10 miles; value of 2 if between 10–49 miles; value of 3 if >= 50 miles. | Cambridge SME Survey |

Firm Growth | Firm growth in terms of changes in the number of employees over 5 years. | Cambridge SME Survey |

Attitude | Dummy variable that takes on the value 1 if the firm considers the main bank’s attitude as ‘supportive’ or ‘helpful’ and zero otherwise. | Cambridge SME Survey |

Herfindahl-Hirschman index | Sum of the squared market shares in terms of total assets | BankScope and authors’ calculations |

H-Statistic (1) | Measure of the degree of competition, dependent variable is interest revenue | BankScope and authors’ calculations |

H-Statistic (2) | Measure of the degree of competition, dependent variable is total revenue | BankScope and authors’ calculations |

Appendix II: Computation of the H-Statistic and of the HHI

We present in this appendix a brief overview of the Panzar and Rosse (1987) H-Statistic that we utilise to gauge competition. This statistic is widely used to test for banking competition (e.g., Molyneux et al. 1994; Claessens and Laeven 2004; Schaeck et al. 2009). Subsequently, we also briefly discuss the way we compute the HHI.

1.1 Computation of the H-Statistic

The H-Statistic is derived from reduced-form revenue equations and measures market power by the extent to which changes in factor input prices are reflected in revenue. Assuming long-run equilibrium, a proportional increase in factor prices will be mirrored by an equiproportional increase in revenue under perfect competition. Under monopolistic competition, however, revenues increase less than proportionally to changes in input prices. In the monopoly case, increases in factor input prices will be either not reflected in revenue, or will tend to decrease revenue.Footnote 11 The magnitude of H can be interpreted in the following way:

- H ≤ 0 :

-

indicates monopoly equilibrium

- 0 < H < 1 :

-

indicates monopolistic competition

- H = 1 :

-

indicates perfect competition

To calculate H-Statistics for local banking markets in which the SMEs in the survey operate in, we proceed as follows. In the first step, we obtain additional information from the Survey of the Financing of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises in Western Europe about the first three digits of the postcodes where the SME’s are located.Footnote 12 This allows us to ascertain exactly in which regions of Bavaria and the South-East of England the firms operate. Next, we obtain bank data from BankScope and download all savings, co-operative, and commercial banks operating in these regions that we identify with the postcodes. This exercise allows us to manually match firms with banks operating in these regions. We retrieve BankScope data for the years 1998–2001 to be able to capture competitive dynamics when calculating H-Statistics. We impose the criterion that we need at least 15 bank-year observations in each region to obtain reasonable estimates of the H-Statistic.

For the German data, we are then able to establish four regional banking markets in Bavaria based on the survey data. All these markets are located in the south of Bavaria and closely match administrative districts, the so-called “Landkreise” to which the operations of small and regional banks are typically constrained. For the UK, we identify six regional banking markets based on postcodes, these markets overlap with “counties”.

Using a fixed effects panel data estimator we estimate the following reduced-form revenue equation for each one of the local banking markets as follows

where P it is the ratio of interest revenue to total assets (proxy for output price), W 1,it is the ratio of interest expenses to total deposits and money market funding (to proxy for the input price of deposits), W 2 , it is the ratio of personnel expense to total assets (proxy for the price of labour) and W 3,it is the ratio of other operating and administrative expenses to total assets (proxy for price of fixed capital), with i denoting bank i and t denoting time t. Y 1,it is a control variable for the ratio of equity to total assets, Y 2,it controls for the ratio of net loans to total assets and Y 3,it is the log of total assets to capture size effects. All variables enter the equation in logs. H is calculated as β 1 + β 2 + β 3. For a subsequent sensitivity test reported in Section 4 we re-run Eq. (A.1) with the ratio of total revenue to total assets as dependent variable.

Since the H-Statistic assumes long-run equilibrium, we perform the following equilibrium test and estimate Eq. (A.1) with the pre-tax return on assets as dependent variable.

The modified H-Statistic is the equilibrium statistic and it is again calculated as β 1 + β 2 + β 3. We test if the equilibrium statistic E = 0, using an F-test. This test aims to establish whether input prices are uncorrelated with industry returns since a competitive system will equalise risk-adjusted rates of return across banks in equilibrium. If this hypothesis is rejected, the market is assumed to be in disequilibrium. The results from our equilibrium test indicate that the markets under consideration are in long run equilibrium.

1.2 Computation of the Herfindahl-Hirschman index

Whereas the panel data estimator yields exactly one observation for each one of the ten different local markets, we proceed as follows to compute HHIs that can be used for the estimation in our cross-sectional regression models. First, we calculate annual HHIs for the local markets for each year. Second, we then take the average of the annual HHIs for the local markets to use them in our subsequent estimations.

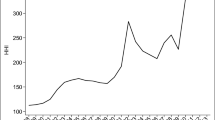

We present an overview of the two different H-Statistics and the HHIs for the local banking markets in Table 5. To explore the interrelationships, we have also explored further the relation between HHI and the H-Statistic. Our visual inspection already suggests a positive relationship between the two variables. We also examine the correlation and find that they are significantly positively correlated (correlation coefficient 0.64***). This finding is in line with the results presented in Claessens and Laeven (2004), and further challenges the predominant view that concentration and competition are inversely related. Fig. 1

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mercieca, S., Schaeck, K. & Wolfe, S. Bank Market Structure, Competition, and SME Financing Relationships in European Regions. J Financ Serv Res 36, 137–155 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-009-0060-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-009-0060-0