Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to describe effective methods of developing pretend play that is intrinsically motivating for young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) using the topic of circumscribed interests. Children with ASD often develop very specialized interests, known as Circumscribed Interests (CI). However, their limited and intense interests are often perceived by others, especially by parents, as interfering with their learning and social interactions with others. This paper reports how one parent fostered pretend play in her preschool child with autism based on his CI in “trains.” Four steps for promoting pretend play for preschool children with autism using their topic of interest are presented. These include (1) Creating a web, (2) Modeling pretend play through use of divergent materials, (3) Modeling verbal interaction in pretend play, and (4) Providing theme boxes and field trips/excursions. The author concludes that the four steps are useful for not only fostering their active involvement in pretend play, but also in helping their topic of special interest expand into a wide range of pretend play. In addition, creating webs based on CI may enable caregivers or teachers to intentionally provide meaningful experience with specific outcomes in mind for children with autism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Our son Tom, who has a diagnosis of autism, developed an intense interest in trains at around age 2. This intense level of interest caused some friction in our family. For example, whenever we visited a local zoo, he was only interested in riding on the zoo trains. At first, this “obsession” seemed typical until we found ourselves planning all of our family vacations around opportunities to see or ride on trains. At the age of 3, he had only 14 vocabulary words and “train” was one of them. Any conversation we held revolved around trains, and this interfered with his relationships with peers, and even his sister. He wouldn’t play with or talk about anything else.

Introduction

According to a report by the Autism Society (2007), individuals receiving the diagnosis of autism are increasing worldwide, such as United Kingdom (1 in 100), United States (1 in 100), and India (1 in 250). Among the challenges children with autism experience, repetitive and restrictive behavior and interest often draw the attention of caregivers and teachers (American Psychiatric Association 2000; Attwood 2007). This unusual level of intensity and/or focus of interest or preoccupation is defined as Circumscribed Interest (CI) (Boyd et al. 2007). Examples of CI for children with autism are objects, machines, and dinosaurs (Attwood 2003; South et al. 2005). CI is often interchangeably used with restricted interests, special interests or obsession (Mancil and Pearl 2008).

CI in children with autism in social situations is often regarded as problem behavior. These restrictive interests can limit the ability of these children to learn and to fit in with peers (National Research Council 2001). According to a recent study based on a survey completed by parents, about 75% of preschool children with autism and 88% of elementary school children with autism display special interest in a particular topic (Klin et al. 2007). In addition, the parents perceive their children’s CI as interfering with their learning and interactions with others. Likewise another study targeting children and adolescents (mean age = 14) indicated that 85% of children/adolescents with high-functioning autism (HFA) and 79% of children/adolescents with Asperger syndrome (AS) demonstrate “repetitive talk about one topic” according to the interview of their parents (South et al. 2005). Further, a majority of the parents report that their children demonstrate “abnormally obsessional interest” (HFA = 76%, AS = 63%). If CI is the norm for children with autism, in what way can caregivers or parents direct their children’s CI to produce meaningful outcomes?

Circumscribed Interests as Motivator

Recently a growing numbers of studies conducted in various countries indicate that children’s CI may be used as an effective tool in developing social skills or appropriate behavior (e.g., Attwood 2007; Boyd et al. 2007; Ito 2004; Mercier et al. 2000; Ogilvie 2011). Spencer et al. (2008), for example, used the special interests of children with autism to encourage appropriate social skills. This strategy, called the Power Card Strategy, combines a story about a social situation with an illustration from the individual’s special interest to teach a target behavior. Children’s CI may also be used as a reward to motivate engagement in appropriate behavior or non-preferred activities (Mancil and Pearl 2008). For example, a child who has difficulty eating a variety of foods might be more motivated to taste a new food if contingent upon a 30 s clip of her favorite video.

Although recent research was carried out in regard to the use of CI as a strategy to motivate children with autism to engage in target behavior, there are only a few studies focusing on the use of CI to develop play skills for young children with autism. Play is essential for growth and development for all children, including individuals with autism.

Understanding Types of Play for Children with Autism

In typically developing children, play is defined as (a) voluntary and intrinsically motivated, (b) symbolic, meaningful, and transformational, (c) active, (d) rule-bound, and (e) pleasurable (Isenberg and Jalongo 2009). However, children with autism tend not to develop play in the same way that typically developing children do, especially with regard to the symbolic aspects of play (Baron-Cohen 1987; Sherratt 2002). Previous research suggests impoverished pretend play in children with autism in terms of frequency, complexity, spontaneity, and playfulness (Hobson et al. 2009; Rutherford et al. 2007). In fact, impairments in pretend play are part of the diagnostic criteria for Autistic Disorder (American Psychiatric Association 2000).

In the past, research has focused on play intervention for children with autism. While some have focused on functional play, others have focused on developing pretend play, which children with autism often find challenging (Bigham 2008). According to a meta-analysis conducted by Lang et al. (2009), play intervention studies for children with autism are generally categorized into three components; modeling, pretending with contingent reinforcement, and child directed or “naturalistic” instruction. Among those interventions, modeling was the most common intervention component for both functional and pretend play. However, as Lang et al. pointed out, the use of modeling to increase pretend play has limitations. The use of modeling as the sole means of targeting play may not lead to generalization of skills. A potentially more effective method of developing pretend play that is intrinsically motivating for children with autism may be to conduct intervention based on the topic of these children’s CI.

The present report describes how a mother fostered the pretend play of her preschool child with autism named Tom based on his CI in “trains.” As found in many intervention programs for young children with autism—such as Greenspan’s The Developmental, Individual Difference, Relationship-based (DIR)/Floortime Model and Gutstein’s Relationship Development Intervention (RDI)—parents play a critical role because of the importance of this emotional relationship (Greenspan and Wieder 2001; Gutstein and Sheely 2002; National Research Council 2001). Affective relationship building between child and caregiver is essential for a child to achieve greater mastery of social, emotional, and intellectual skills (Greenspan and Wieder).

Tom was diagnosed as speech impaired and developmentally delayed (functioning level of a 17-month-old) when he was age 3. This opened the door to enroll him in a public preschool school program for young children with disabilities. At age 5 Tom received a diagnosis of PDD (pervasive developmental disorders) from a developmental pediatric physician at a children’s hospital. In addition, the results of a psychometric assessment (e.g., the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale: 4th Edition) placed him on the borderline of the low average range of intelligence with significant deficits of language development. His mother, an experienced early childhood educator for 20 years, implemented play interventions in the home setting for 3 years.

As guiding strategies to facilitate pretend play in preschool children with autism through the use of their CI, there are four steps introduced in this paper: Creating a web based on the child’s CI, Modeling pretend play by use of divergent materials, Modeling verbal interaction in pretend play, and Providing theme boxes and field trips/excursions to promote pretend play.

Strategies to facilitate pretend play for children with autism

Step 1

Create a web based on the child’s CI

Step 2

Model pretend play by use of divergent materials

Step 3

Model verbal interactions in pretend play

Step 4

Provide theme boxes and field trips/excursions to promote pretend play

Strategies to Facilitate Pretend Play for Children with Autism

Step 1: Creating the Web Based on the Child’s CI

Contemporary intervention programs for children with autism are often child-directed in the sense that they are initiated by the child and focus on the child’s interests (Greenspan and Wieder 2001; National Research Council 2001; Prizant et al. 2001). This type of approach encourages children’s initiation and spontaneity in communication. The current study is also based on this premise that the child’s special interest is a key ingredient, not only in facilitating the child’s participation, but also in building affective relationship, which leads to greater mastery of skills.

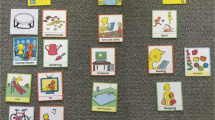

In order to expand Tom’s play experience based on his interest, his mother first created a topic web (concept map), which visually represents concepts and subconcepts that he already knew or he might be interested in. Children with autism tend to interact with play materials with repetitive identical acts (Schuler and Wolfberg 2001). Creating webs provides a wide range of possibilities to develop activities based on the topic. This strategy was inspired by the Project Approach, which is an in-depth investigation of a real world topic that children are interested (Katz and Chard 2000). Yet, it is important to make sure that the topic is concrete, age-appropriate, and relevant to the curriculum goals. In a Project Approach, children and teachers typically discuss what they know and what they would like to know in order to create a topic web. However, in this case, due to Tom’s limited language skills, his mother created a web through observation of his interests (Fig. 1).

Step 2 Modeling Pretend Play by Use of Divergent Materials

It is often challenging for children with autism to use divergent play materials that invite multiple uses and open-ended activities because of their preference toward “sameness.” This is because children with autism tend to develop static intelligence (a thinking process toward a specific, predictable, and either correct or wrong solution) rather than dynamic intelligence (a thinking process geared toward multiple strategies, perspectives and meaningful solutions) (Gutstein 2006). Isenberg and Jalongo (2009) categorized materials that children use into two types; convergent and divergent play materials. Convergent materials are those which lead to single, correct, or prescribed uses, and which do not provide much opportunity for creativity (e.g., coloring books, talking dolls, and wind-up toys). By contrast, divergent materials are open-ended and lead to a wide variety of uses such as blocks, sand, and water. For example, a block can be used as food, a figure, a car, and a building in pretend play. Here are some examples of divergent materials:

-

Blocks of various colors, sizes, shapes and materials (e.g., nature blocks, LEGO)

-

Modeling dough (e.g., play dough, home-made salt dough)

-

Sand and water

-

Recycling materials (e.g., empty cardboard boxes, toilet paper rolls)

Tom was not exceptional in showing hesitancy toward divergent play materials such as blocks. Using his interest in trains, his mother brainstormed a list of divergent or open-ended materials that could be used to create train themed pretend play. She equipped Tom’s playroom with different types of blocks (e.g., color, shape, materials, and size) and put them in separate colored toy bins. In the beginning she lined up the rectangle shaped blocks to make trains and moved them forward on the floor saying “choo choo.” Tom seemed to like this idea and within a few months he started doing the same activity but more intensively, lining up the blocks from one side of the room to another and creating different types of trains by sorting the blocks by colors, shapes, materials, and sizes.

Sometimes Tom’s mother added new open-ended materials into his pretend play on the train theme, such as sand and play-do. For example, she hid several miniature train cars inside a sandbox so that he had to dig through to find them. As often seen in children with autism, he demonstrated tactile defensiveness such as avoiding the touch of messy or wet materials. Introducing new materials through train themed pretend play appeared to expand his comfort zone.

As with the planning web (Fig. 1), Tom’s mother gradually introduced various sub-themes related to trains (e.g., conductors, passengers, tunnels, stations, and railroad crossings) through pretend play. She started adding recycling materials, such as an empty tissue box for a train station, a toilet roll for a passenger or a building, a trash bag for a river, and an old chair for a tunnel. Not only did Tom learn to collaborate with an experienced player like his mother, but he also started spontaneously using divergent materials to create his set-up. In Fig. 2, he used a blue chair as a tunnel and also made a trestle with Lego blocks to support his train roads. Putting the various materials together to make his own train system was an investigation, which required a complex understanding of weights, space, heights, and gravity. Thus, using divergent materials for pretend play based on CI produces the following opportunities:

-

Enable children with autism to use their imaginations.

-

Help children with autism to interact with new materials in non-threatening ways.

-

Create opportunities for manipulating and experimenting for children with autism.

-

Encourage children with autism to work cooperatively with others.

Step 3 Modeling Verbal Interaction in Pretend Play

Social communication skills are also identified as a primary challenge for children with autism (American Psychiatric Association 2000; Baron-Cohen et al. 1999). Although some children with autism are verbal, they often demonstrate impairment in conversational skills (Charlop-Christy and Kelso 2003). Some researchers suggest using pre-determined scripts to teach children with autism conversational speech skills in play settings (Goldstein and Cisar 1992).

As an intervention, Tom’s mother initiated conversations in pretend play by introducing short pre-determined scripts related to the train theme. She modeled short and simple scripts, such as “All aboard,” “Train is leaving,” “Next stop is …..” and “Ticket, please.” In order to provide context for the conversations, she added little people figures and small stuffed animals to his train play. Tom and his mother pretended that some of the figures were their family members and the train conductor, spending numerous hours moving those figures on and off the trains.

In addition, presenting visual media, such as children’s books and DVDs on the topic of trains, led to spontaneous conversation; Tom acted as a main character in the story. For example, after watching Thomas the Tank Engine videos many times, he started pretending to be Thomas saying things such as “Hurry! Hurry!” and “I’m going to stop!” Because children with ASD are often preoccupied with a favorite TV show or video (Ogilvie 2011), this media can intrinsically motivate them to imitate behaviors, in this case, conversations. His mother equipped the play room with plenty of children’s books, DVDs and PC software, which were directly or indirectly related to the theme of trains (Table 1).

After reading The little engine that could by Watty Piper, Tom and his mother pretended to be a little railroad engine climbing up a hill while moving their arms in a circular motion like train wheels and saying “I think I can, I think I can, I think I can.” After they finally got up to the top of the hill, they congratulated each other by saying, “I thought I could, I thought I could.”

Using the topic of interest for children with autism as a motivator, teachers or parents can facilitate conversation skills in pretend play. Here are some key strategies:

-

Introduce short and simple phrases that are easy to imitate.

-

Introduce phrases that require a response from others, which in turn facilitate interaction among participants (e.g., “Ticket, please”).

-

Use visual cues such as picture books or toy figures so that they understand the play contexts.

Step 4 Providing Theme Boxes and Field Trips/Excursions to Promote Pretend Play

In order to promote pretend play for children with autism through the use of their CI, the following guiding strategies, themes boxes and field trips/excursions, are introduced.

Theme Boxes

Theme boxes stimulate pretend scenarios for children with autism by providing a wide variety of materials that can be used in certain play contexts. In the classroom or home environment, adults can prepare a wide range of the related accessories and props based on a theme. Using the train web (Fig. 1) as a reference, Tom’s mother gradually added the following props and stored them in a big container: train sets (e.g., trains, railroad tracks, railroad crossings, stations, tunnels, trestles, and signs), little people figures, flags, conductor’s and engineer’s hats, a whistle, tickets, a suitcase, plastic coins, toy houses/buildings, and maps.

Tom’s favorite prop was a suitcase. When he was about age four and a half, his mother bought him a suitcase to use in real trip as well as in his train themed play. He packed his clothes and toys in his suitcase and pretended to be a passenger who travels various locations with his map and suitcase. His sister sometimes joined his make believe by bringing her own backpack and stuffed animals. As Tom’s pretend play expanded in various directions, it opened up opportunities for collaboration with his sister.

Field Trips and Excursions

Field trips and excursions provide a meaningful context for children with autism through gaining knowledge and expanding experience related to their interests. In order to maximize the benefit from outings, adults and children can research information about their visit in advance from libraries, websites or maps. Ensuring predictability, knowing what will happen during the visit, will decrease the chance of a problem behavior and increase active participation for children with autism. Tom’s mother often showed the website of the place that they would visit ahead of time to promote his interest. Tom and his family visited various locations to ride or observe trains, such as subway stations, train museums, the zoo, and the airport. After coming back from an outing, Tom’s mother invited him to revisit the experience by engaging in pretend play.

After visiting a subway station, Tom seemed to be fascinated with the whole process of how one has to buy a ticket from a machine to go through the entrance gate and board a train. His mother created a ticket machine with an empty cardboard box. Tom assisted his mother by making tickets by cutting pieces of paper. Tom’s mother added a place in the box in which they could put toy coins into exchange for a ticket. Then he and his mother pretended a couch in the living room was a passenger train. Tom, his sister, and his mother played numerous hours, taking turns playing the role of a passenger, ticket machine assistant, and a conductor.

Thus, providing theme boxes and field trips/excursions for pretend play based on CI produces the following opportunities:

-

Engage in pretend play with a variety of materials related to a topic.

-

Extend the interest, knowledge and experience of children with autism in various directions.

-

Provide opportunities for successful field trips and excursions for children with autism based on their topic of interest.

Discussion

The purpose of using CI as a guiding strategy is to intrinsically motivate children with autism to engage in pretend play activities. The four steps that promote pretend play skills using children’s CI can not only foster their active involvement in pretend play, but also become a useful tool in expanding their restricted interest into a wider range of pretend play. Tom’s passion for trains seemed to eventually spread out into different themes of interest, such as travel and airplanes, by introducing him to a wide variety of pretend play related to trains.

Although this paper represents a small sample of one child, it does add to the increasing body of knowledge for developing special interests for children with autism at home and in school settings. Examples indicated in this paper suggest that organizing pretend play activities based on a child’s CI foster various play skills, such as collaborating with other children or utilizing a wide range of materials into play, including divergent materials. In addition, creating webs based on the CI of a child may enable caregivers or teachers to intentionally provide meaningful experiences with specific outcomes in mind for children with autism.

Whether the special interest of individuals with autism remain a barrier or are transformed into a talent will largely depend upon the intervention of people who interact with them. Although the topic of interest might change over time, the tendency toward restricted interests will perhaps remain. It is clear that there are some potential positive consequences of CI in children with autism. These interests can be keys to building friendships with someone who has the same interest or in securing gainful employment (Attwood 2003). The success will largely depend upon the teaching and parenting strategies that systematically incorporate these interests into meaningful activities and specific goals.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text revision, DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: Author.

Attwood, T. (2003). Understanding and managing circumscribed interest. In M. Prior (Ed.), Learning and behavior problems in Asperger syndrome (pp. 126–147). New York: The Guilford Press.

Attwood, T. (2007). The complete guide to Asperger’s syndrome. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Autism Society. (2007). Autism spectrum disorders. http://support.autism-society.org/site/PageServer?pagename=research_envirohealth_101_02. Accessed 24 December 2011.

Baron-Cohen, S. (1987). Autism and symbolic play. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 5, 139–148.

Baron-Cohen, S., Ring, H. A., Wheelright, S., Bullmore, E. T., Brammer, M. J., Simmons, A., et al. (1999). Social intelligence in the normal and autistic brain: An fMRI study. European Journal of Neuroscience, 11, 1891–1898.

Bigham, S. (2008). Comprehension of pretence in children with autism. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 26, 265–280.

Boyd, B. A., Conroy, M. A., Mancil, G. R., Nakao, T., & Alter, P. J. (2007). Effects of circumscribed interests on the social behaviors of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder, 37, 1550–1561.

Charlop-Christy, M. H., & Kelso, S. E. (2003). Teaching children with autism conversational speech using a cue card/written script program. Education and Treatment of Children, 26, 108–127.

Goldstein, H., & Cisar, C. L. (1992). Promoting interaction during socio-dramatic play: Teaching scripts to typical preschoolers and classmates with disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25, 265–280.

Greenspan, S. I., & Wieder, S. (2001). A developmental approach to difficulties in relating and communicating in autism spectrum disorder. In B. Prizant & A. Wetherby (Eds.), Autism spectrum disorders: A transactional developmental perspective (Vol. 9, pp. 279–306). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Gutstein, S. (2006). Introduction to RDI. Denver, CO: Workshop.

Gutstein, S. E., & Sheely, R. K. (2002). Relationship development intervention with young children: Social and emotional development activities for Asperger syndrome, autism, PDD and NLD. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Hobson, R. P., Lee, A., & Hobson, J. A. (2009). Quality of symbolic play among children with autism: A social-developmental perspective. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 12–22.

Isenberg, J. P., & Jalongo, M. R. (2009). Creative thinking and arts-based learning: Preschool through fourth grade (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Ito, K. (2004). A preschool teacher who guided a child’s interests from letters to his friends: The role of a preschool teacher working with autistic children as “the human environment” (Japanese). Research on Early Childhood Care and Education in Japan, 42, 29–41.

Katz, L. G., & Chard, S. C. (2000). Engaging children’s minds: The project approach (2nd ed.). Stamford, CT: Ablex Publishing.

Klin, A., Danovitch, J. H., Merz, A. B., & Volkmar, F. R. (2007). Circumscribed interests in higher functioning individuals with autism spectrum disorders: An exploratory study. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 32, 89–100.

Lang, R., O’Reilly, M., Rispoli, M., Shogren, K., Machalicek, W., Sigafoos, J., et al. (2009). Review of interventions to increase functional and symbolic play in children with autism. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 44, 481–492.

Mancil, G. R., & Pearl, C. E. (2008). Restricted interests as motivators: Improving academic engagement and outcomes of children on the autism spectrum. Teaching Exceptional Children Plus, 4, 2–15.

Mercier, C., Mottron, L., & Belleville, S. (2000). A psychosocial study on restricted interests in high functioning persons with pervasive developmental disorders. Autism, 4, 406–425.

National Research Council. (2001). Educating children with autism. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Ogilvie, C. R. (2011). Step by step: Social skills instruction for students with autism spectrum disorder using video models and peer mentors. Teaching Exceptional Children, 43, 20–26.

Prizant, B. M., Wetherby, A. M., & Rydell, P. J. (2001). Communication intervention issues for young children with autism spectrum disorders. In B. Prizant & A. Wetherby (Eds.), Autism spectrum disorders: A transactional developmental perspective (Vol. 9, pp. 193–224). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Rutherford, M. D., Young, G. S., Hepburn, S., & Rogers, S. J. (2007). A longitudinal study of pretend play in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1024–1039.

Schuler, A. L., & Wolfberg, P. J. (2001). Promoting peer play and socialization: The art of scaffolding. In B. Prizant & A. Wetherby (Eds.), Autism spectrum disorders: A transactional developmental perspective (Vol. 9, pp. 225–249). Baltimore, MD: Paul H Brookes.

Sherratt, D. (2002). Developing pretend play in children with autism: A case study. Autism, 23, 169–179.

South, M., Ozonoff, S., & McMahon, W. M. (2005). Repetitive behavior profiles in Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35, 145–158.

Spencer, V., Simpson, C. G., Day, M., & Buster, E. (2008). Using the power card strategy to teach social skills to a child with autism. Teaching Exceptional Children Plus, 5, 2–10.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Porter, N. Promotion of Pretend Play for Children with High-Functioning Autism Through the Use of Circumscribed Interests. Early Childhood Educ J 40, 161–167 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-012-0505-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-012-0505-1