Abstract

Background

Open access colonoscopy (OAC) has gained widespread acceptance and has the potential to increase colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. However, there is little data evaluating its appropriateness for CRC prevention.

Aims

The aim of this study is to evaluate the appropriateness of OAC in CRC screening and polyp surveillance by comparing to procedures ordered by gastroenterologists (NOAC). As secondary outcomes, we compared the quality of bowel preparation and adenoma detection rate (ADR) between OAC and NOAC.

Methods

It is retrospective single-center study. Inclusion criteria included patients > 50 years of age undergoing a colonoscopy for CRC screening and surveillance. Appropriateness was defined as those colonoscopies performed within 12 months of the recommended 2012 consensus guidelines. Secondary outcomes included the quality of bowel preparation and ADR.

Results

5211 colonoscopies met inclusion criteria, and 64.9% were OAC. Screening OAC was appropriately 91.6% and NOAC 92.9% of the time (p = 0.179). Surveillance NOAC were inappropriate in 26.4% of cases, and surveillance OAC was 32.6% (p = 0.008). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that OAC did not influence ADR (OR for NOAC 0.97; 95% CI 0.86–1.1; p = 0.644) or an adequate bowel preparation (OR for NOAC 1.11; 95% CI 0.91–1.36; p = 0.306).

Conclusion

OAC performed similarly to NOAC for screening indications, quality of bowel preparation, and ADR. However, more surveillance procedures were inappropriate in the OAC group although both groups had a high number of inappropriate indications. Although OAC can be efficiently performed for screening indications, measures to decrease inappropriate surveillance colonoscopies are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening was introduced in the 1970s [1], and its introduction has coincided with a decrease in CRC incidence and mortality. Since the first guidelines addressing CRC screening were published by the American College of Gastroenterology in 2000 [2], there has been heightened awareness among the medical community and the general population with regard to the importance of timely CRC screening. Despite this increased awareness, a 2013 Center for Disease Control (CDC) report estimated that a third of US adults aged 50–75 years had not undergone screening for CRC [3]. In order to augment screening and have a meaningful impact on CRC incidence and mortality, a multifaceted approach to address awareness and decrease barriers in a timely and cost-effective manner is necessary.

Over the past several decades, the onus for ensuring the general population is appropriately screened for CRC has fallen on primary care physicians and the most commonly employed methods of screening involve colonoscopy or a fecal test for occult blood. After identifying a suitable patient for CRC screening by colonoscopy, the primary care provider will either refer the patient to a gastroenterologist for an office visit and subsequent procedure or directly order this procedure through open access colonoscopy (OAC), whereby the colonoscopy is performed without a prior office visit with a gastroenterologist [4]. OAC has the potential to remove barriers and ensure increased screening by eliminating unnecessary office visits and associated costs [5] and thus allow for screening procedures to be performed in a timely and efficient manner. While over the past two decades the use of OAC has become increasingly widespread [6], recent estimates still suggest that 30% of screening colonoscopies are preceded by an office visit with a gastroenterologist [5].

In 2012, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), ACG, American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and American Gastroenterology Association (AGA) published consensus guidelines that addressed CRC screening and prevention [7]. As OAC has gained widespread acceptance, there is a paucity of data on OAC for CRC screening and polyp surveillance and no studies have used the 2012 consensus guidelines to determine the appropriateness. While there is a potential to increase CRC screening through the use of OAC, ensuring that procedures are performed appropriately by adhering to guidelines set forth by various societies is critical.

The aim of this study is to evaluate the appropriateness of OAC in CRC screening and polyp surveillance by comparing to procedures requested by gastroenterologists or non-open access colonoscopy. As secondary outcomes, we compared the quality of bowel preparation and adenoma detection rate (ADR) between OAC and NOAC.

Methods

Study Design

This is a retrospective chart review of outpatients undergoing colonoscopies at an academic medical center between January 1, 2013, and June 15, 2016. This protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Cohort

Individuals greater than the age of 50 years who underwent a colonoscopy for CRC screening or polyp surveillance were identified from the Cleveland Clinic database (eResearch Cleveland, OH). Colonoscopies that included the diagnosis code of either “screening” or “surveillance” were identified and verified to ensure inclusion criteria. Colonoscopies performed in patients with a known history of hereditary cancer syndromes, such as familial adenomatous polyposis or hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer, were not included. Screening colonoscopy is a colonoscopy performed in a patient with no prior history of polyps with the purpose of CRC detection and prevention. Surveillance colonoscopy is a colonoscopy performed in a patient with a prior history of polyps. Colonoscopies performed for other indications were excluded. All colonoscopies were performed by staff gastroenterologists or by a gastroenterology fellow under the direct supervision of an attending gastroenterologist. Each attending physician had performed a minimum of 2000 colonoscopies. All colonoscopies were performed using high-definition colonoscopes and anesthesiology provided anesthesia with propofol.

Factors Examined

Patient demographics including age, gender, body mass index (BMI), and race were collected after review of the patient’s electronic medical record. The indication for the colonoscopy was categorized as either screening or surveillance as defined previously. Review of the medical record was used to determine whether the procedure was an OAC, which was defined as a colonoscopy in which the non-gastroenterology provider evaluates and places the order for the procedure without a prior gastroenterology consultation [4]. A colonoscopy ordered by a gastroenterologist for the purpose of CRC prevention was defined as a NOAC.

Definition of Primary Outcome—Appropriateness

The primary outcome was appropriateness of colonoscopy based on the 2012 consensus guidelines for CRC screening and surveillance as illustrated in Table 1 [7]. These guidelines were in effect 1 year prior to our initial start date. Inappropriate colonoscopies were defined as those that were performed more than 12 months before or after the interval determined by the 2012 guidelines. The appropriate interval was determined after review of the medical chart and evaluating the patient’s family history of CRC and prior colonoscopy findings. For cases in which the index colonoscopy was available, the colonoscopy and pathology reports were reviewed to determine the presence, number, size, and pathology of polyps and the quality of bowel preparation. If the preparation was sub-optimal, then the interval that was recommended by the performing endoscopist was taken as the appropriate interval. For cases in which the index colonoscopy was not available, appropriateness was based on review of the history charted in the medical record. If the initial colonoscopy was performed late and the patient had not been previously seen by a health care provider, the procedure was determined as appropriate as this was not the responsibility of the ordering provider. All inappropriate colonoscopies, and any additional colonoscopies where there were doubts about classification, were reviewed by a second author.

Adherence to guidelines for OAC was compared to those colonoscopies ordered by gastroenterologists (NOAC). At the Cleveland Clinic Florida, all colonoscopies are ordered by a physician as patients do not receive reminders to schedule the initial or follow-up colonoscopies. Inappropriate colonoscopies were further categorized as either late or early, and the number of months by which a colonoscopy was inappropriate was calculated.

Definition of Secondary Outcomes

Secondary outcomes included the quality of bowel preparation, ADR, and rate of detection of high-risk adenomas (HRA). The bowel preparation agent used was at the discretion of the physician ordering the colonoscopy and comprised predominantly of polyethylene glycol based-regimens. After the encounter with the ordering physician, patients were given a standard set of instructions to follow that are identical for all providers in the institution. Several days prior to their colonoscopy, an attempt was made to contact all patients by phone to confirm their appointment; however, the preparation instructions were not discussed. The quality of the bowel preparation was determined by the performing endoscopist using the modified Aronchick scale [8, 9]. Bowel preparation was classified as either excellent, good, and fair or poor. Adequate bowel preparation was defined as either an excellent or a good preparation, and inadequate preparation was defined as either fair or poor. Documentation of the preparation quality is required by the reporting software for completion of the procedure report. Adenomas included tubular adenomas, adenomas with villous histology or high-grade dysplasia, sessile serrated adenomas, and traditional serrated adenomas. HRA’s were defined as a tubular adenoma ≥ 1 cm, three or more adenomas, or an adenoma with villous histology or high-grade dysplasia.

Statistical Analysis

Data were checked for normality, and descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables. Chi-square tests were used to examine categorical variables, and Student’s t-tests were used to examine continuous variables to assess patient differences between OAC and NOAC procedures and to compare adherence to AGA guidelines for ordering colonoscopies. Unadjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed to determine associations between patient characteristics, adenoma detection, and adequate bowel preparation. Patient variables that were associated with adenoma detection or adequate bowel preparation at p < 0.15 in the bivariate analyses were considered for inclusion in multivariate logistic regression models. Model building proceeded via backward stepwise selection and interaction terms were assessed. In the final multivariate models, only variables that remained significant at p < 0.05 were retained. Statistical tests were performed using SPSS version 23 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a p value of < 0.05 was used to determine significance.

Results

Patient Characteristics

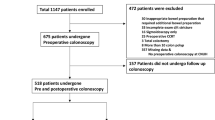

A total of 5211 patients underwent a screening or surveillance colonoscopy with a majority (68.4%) performed for CRC screening. OAC was the source of referral for 64.9% of the procedures. The baseline characteristics for the cohort are included in Table 2. Although there were statistical differences between both groups in respect to age, BMI, and ethnicity, these differences were not clinically significant. However, more OAC’s were performed in the morning.

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome of adherence to the 2012 guidelines within 12 months is represented in Fig. 1. Among all OAC’s, 84.6% were appropriate, while in the NOAC group, 85.9% were appropriate (p = 0.21). Evaluating only screening colonoscopies, both groups performed similarly with 91.6% of the OAC’s classified as appropriate and 92.9% in the NOAC group (p = 0.179). However, there were more inappropriate surveillance OAC’s compared to NOAC’s (32.6% vs. 26.4%, p = 0.008).

Upon evaluating those procedures that were inappropriate by more than 12 months, a significant majority were performed earlier than recommended although there were no differences between OAC and NOAC (Fig. 2). Inappropriately early colonoscopies were on average 41.6 and 42.6 months early for NOAC and OAC, respectively. Those colonoscopies that were inappropriately late were on average 47.2 and 40.2 months late for NOAC and OAC, respectively.

Secondary Outcomes

Bowel preparation was determined as being adequate in 91.6% of NOAC and 90.8% of OAC (p = 0.354). The results of univariate and multivariate analyses on the likelihood of having an adequate bowel preparation are shown in Table 3. The likelihood of having an adequate bowel preparation was similar between the two groups, with an OR for NOAC of 1.11 (95% CI 0.91–1.36; p = 0.306).

Both groups performed similarly in detecting the presence of adenomas. Adenomas were noted in 39.7% of NOAC’s and in 38.6% of OAC’s (p = 0.438). HRA’s were found in 8.8% of OAC’s and 8.9% of NOAC’s (p = 0.879). As performed for bowel preparation, variables that influence ADR were evaluated in univariate analysis and those reaching statistical significance in our patient population were included in multivariate analysis. The results of univariate and multivariate analysis on the likelihood of detecting adenomas are shown in Table 4. There was a similar likelihood of detecting adenomas between the two cohorts with an OR for NOAC of 0.97 (95% CI 0.86–1.1; p = 0.644).

Furthermore, the appropriateness of colonoscopy, regardless of provider, did not influence the quality of bowel preparation or ADR. Both appropriate and inappropriate colonoscopies had a similar likelihood of adequate bowel preparation with an OR of 0.90 (95% CI 0.74–1.08; p = 0.249). Similarly, both appropriate and inappropriate colonoscopies had a comparable ADR with an OR of 0.94 (95% CI 0.8–1.11; p = 0.485).

Discussion

In the most recent ASGE guidelines on the use of open access endoscopy, several issues were introduced, including patient acceptance and preparedness for endoscopy, diagnostic yield of the endoscopy, and appropriateness of the referral [4]. OAC appropriateness has been assessed utilizing the ASGE guidelines on “Appropriate Use of GI Endoscopy”; however, these are general guidelines that are not specific to CRC prevention. These studies observed that approximately 80% of open access endoscopies, ordered for a variety of indications, were appropriate [10, 11]. Another study, using their institutional guidelines to evaluate the appropriateness, reported that 28% of colonoscopy referrals to an open access unit were inappropriate, and of those inappropriate referrals, 35% were for surveillance and 17% were for screening [12]. Others have described a significant number of inappropriately early surveillance colonoscopies; however, they did not consider the ordering provider [13,14,15]. Our study is the first that focuses solely on those colonoscopies performed for CRC prevention in a large outpatient population using the 2012 consensus guidelines to assess the appropriateness.

Our results show that both gastroenterology and open access providers performed similarly and well when ordering screening colonoscopies. These numbers, however, contrast to those for surveillance colonoscopies where both gastroenterology and open access procedures were inappropriate more than 25% of the time.

The significant number of inappropriate surveillance colonoscopies is likely due to a variety of factors. Primary care providers may lack awareness of the differences in surveillance intervals for patients with hyperplastic polyps, adenomas, and high-risk polyps. A survey conducted of 568 primary care physicians found that when presented with hypothetical vignettes, they were more likely to recommend surveillance colonoscopies earlier than the recommended guidelines at the time [16]. Additionally, gastroenterologists may not be aware of the recommended surveillance intervals or they may disagree with the guidelines based on their personal experience. A survey of 192 gastroenterologists demonstrated that approximately 25% of respondents were unaware of recommended screening intervals for hyperplastic polyps and nearly 20% failed to identify the correct surveillance interval for HRA’s [17]. Another survey of 116 gastroenterologists saw that they often disagreed with the guidelines and preferred to perform surveillance colonoscopies earlier than recommended [18]. Another significant determinant of surveillance interval is the quality of bowel preparation that is documented in the colonoscopy report. In a busy primary care practice, providers may not have the time, or the knowledge, to interpret these findings and determine optimal surveillance intervals. Although adequate post-procedure communication by the gastroenterologist to the patient and referring physician on colonoscopy findings and recommendations could improve inappropriate surveillance intervals, it still falls back on the gastroenterologist to follow the guidelines.

Few studies have assessed OAC’s performance in various quality metrics, such as ADR and quality of bowel preparation. Unlike other studies that evaluated appropriateness of OAC, we used multivariate analyses to assess associations for these quality metrics. Prior studies have shown that the diagnostic yield of OAC, when adhering to the ASGE guidelines for appropriateness, is similar to NOAC [19]. In our study, we observed comparable rates of adenoma detection among the two groups regardless of appropriateness. Adenomas were detected in 39.7% of patients undergoing NOAC and in 38.6% of patients undergoing OAC, with no differences between the groups on multivariate analysis. HRA’s were also detected at similar rates when comparing the two groups. In contrast to prior studies, there was no difference in ADR [20] and quality of bowel preparation when comparing appropriate and inappropriate colonoscopies, regardless of ordering provider.

The introduction of open access procedures raised the question of adequacy of bowel preparation. As the initial visit is with a non-gastroenterologist, there is a concern that patients would receive insufficient information, especially with regard to bowel preparation, and therefore, quality of the bowel preparation may be inadequate to allow for a complete examination [21]. Multivariate analysis, however, did not demonstrate any difference in quality of bowel preparation between the OAC and NOAC groups.

Our study had several limitations. While this is a single-center study, it included 35 primary care physicians and 12 gastroenterologists and, therefore, is the largest study to date to evaluate the appropriateness of OAC. Additionally, as mentioned in the methods, there is no recall system at our center and this allows for an accurate evaluation of the appropriateness between OAC and NOAC. Although the study was retrospective, determination of appropriateness was made after thorough review of the medical record including previous colonoscopies if applicable.

In addition, this study only evaluated colonoscopies that were ordered and performed, not missed opportunities to order a colonoscopy or other screening modality. Quality of bowel preparation was assessed by the modified Aronchick scale, which has not been thoroughly validated but used in multiple studies to differentiate between adequate and inadequate bowel preparations [22,23,24].

Methods to improve CRC screening by adhering to guidelines is a topic that deserves further evaluation. Interventions have been proposed to increase CRC screening rates that may translate to improved adherence to the guidelines. These interventions include utilizing the electronic medical record to alert the health care provider on the appropriate timing of a colonoscopy [25] and the use of a medical assistant to review appropriateness when ordering colonoscopies for CRC prevention [26].

This is the largest study to look at the appropriateness of OAC for CRC prevention, and it is also the only study to review appropriateness using the 2012 consensus guidelines. Furthermore, prior studies have not used multivariate analysis to assess quality metrics when assessing OAC. We observed that screening OAC and NOAC performs similarly and well and that there was no difference in the quality of preparation or ADR between both cohorts. On the contrary, more inappropriate surveillance colonoscopies were performed in the OAC group; however, the number of inappropriate procedures in the NOAC cohort was also unacceptably high. Therefore, although screening OAC can be appropriately performed without the need for a gastroenterology consultation, interventions are needed to decrease the number of inappropriate surveillance colonoscopies ordered by gastroenterologists and primary care providers.

References

Lieberman D, Ladabaum U, Cruz-Correa M, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer and evolving issues for physicians and patients: a review. JAMA. 2016;316:2135–2145.

Rex DK, Johnson DA, Lieberman DA, et al. Colorectal cancer prevention 2000: screening recommendations of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:868–877.

Center for Diseases Control and Prevention. Colorectal cancer screening rates remain low. CDC Newsroom. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2013/p1105-colorectal-cancer-screening.html. Accessed 15 May 2018.

Chandrasekhara V, Eloubeidi MA, Bruning DH, et al. Open-access Endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:1–8.

Riggs KR, Shin EJ, Segal JB. Office visits prior to screening colonoscopy. JAMA. 2016;315:514–515.

Hadlock S, Rabeneck L, Paszat LF, et al. Open-access colonoscopy in Ontario: associated factors and quality. Can J Gastroenterol. 2013;27:341–346.

Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:844–857.

Aronchick CA, Lipshutz WH, Wright SH, et al. Validation of an instrument to assess colon cleansing (abstr). Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2667.

Aronchick CA, Lipshutz WH, Wright SH, et al. A novel tableted purgative for colonoscopic preparation: efficacy and safety comparisons with Colyte and Fleet Phospho-soda. Gastointest Endosc. 2000;52:346–352.

Mahajan RJ, Barthel JS, Marshall JB. Appropriateness of referrals for open-access endoscopy. How do physicians in different medical specialties do? Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2065–2069.

Minoli G, Meucci G, Bortoli A, et al. The ASGE guidelines for the appropriate use of colonoscopy in an open access system. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:39–44.

Baron TH, Kimery BD, Sorbi D, et al. Strategies to address increased demand for colonoscopy: guidelines in an open endoscopy practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:178–182.

Schreuders E, Sint Nicolaas J, de Jonge V, et al. The appropriateness of surveillance colonoscopy intervals after polypectomy. Can J Gastroenterol. 2013;27:33–38.

Heijningen E-MB, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Steyerberg EW, et al. Adherence to surveillance guidelines after removal of colorectal adenomas: a large, community-based study. Gut. 2015;64:1–9.

Anderson JC, Baron JA, Ahnen DJ, et al. Factors associated with shorter colonoscopy surveillance intervals for patients with low-risk colorectal adenomas and effects on outcome. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1933–1943.

Boolchand V, Olds G, Singh J, et al. Colorectal screening after polypectomy: a national survey study of primary care physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:654–659.

Shah TU, Voils CI, McNeil R, et al. Understanding gastroenterologist adherence to polyp surveillance guidelines. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1283–1287.

Saini SD, Nayak RS, Kuhn L, et al. Why don’t gastroenterologists follow colon polyp surveillance guidelines? Results of a national survey. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:554–558.

Ghaoui R, Ramdass S, Friderici J, et al. Open access colonoscopy: critical appraisal of indications, quality metrics and outcomes. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:940–944.

Balaguer F, Llach J, Castells A, et al. The European panel on the appropriateness of gastrointestinal endoscopy guidelines colonoscopy in an open-access endoscopy unit: a prospective study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:609–613.

Staff DM, Saeian K, Rochling F, et al. Does open access endoscopy close the door to an adequately informed patient? Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:212–217.

Gurudu S, Ratuapli S, Heigh R, et al. Quality of bowel cleansing for afternoon colonoscopy is influenced by time of administration. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2318–2322.

Fayad NF, Kahi CJ, Abd El-Jawad KH, et al. Association between body mass index and quality of split bowel preparation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1478–1485.

Anklesaria, Ava B, Chudy-Onwugaje KO, et al. The effect of obesity on the quality of bowel preparation for colonoscopy: results from a large observational study. J Clin Gastroenterol 2018. (Epub ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1097/mcg.0000000000001045.

Printz C. New electronic health record use boosts colon cancer screening. Cancer. 2013;119:2949.

Baker AN, Parsons M, Donnelly SM, et al. Improving colon cancer screening rates in primary care: a pilot study emphasizing the role of the medical assistant. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:355–359.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Molly Moor, Meaghan McMahon, Dr. Hong Liang.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kapila, N., Singh, H., Kandragunta, K. et al. Open Access Colonoscopy for Colorectal Cancer Prevention: An Evaluation of Appropriateness and Quality. Dig Dis Sci 64, 2798–2805 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-019-05612-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-019-05612-8