Abstract

Background

Despite lack of evidence, use of a stylet during endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) is assumed to improve the quality and diagnostic yield of specimens.

Aim

The purpose of this study was to compare EUS-FNA specimens obtained with stylet (S+) and without stylet (S−) for: (i) cellularity, contamination, adequacy, and amount of blood and (ii) diagnostic yield of malignancy.

Methods

Patients who underwent EUS-FNA of solid lesions by two experienced endosonographers at a tertiary referral center using a 22-gauge FNA needle with suction were included. Stylet was used for all EUS-FNA procedures performed between January 2006 and September 2007 and no stylet was used between October 2007 and April 2009 allowing comparison between the two techniques. Cytology slides were retrieved, de-identified and evaluated by two experienced cytopathologists blinded to FNA technique. Slides were evaluated for cellularity, degree of contamination, adequacy, amount of blood and cytologic diagnosis. Fisher’s exact and unpaired t-test were used for comparative analysis.

Results

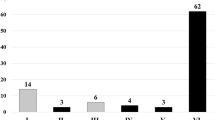

A total of 162 patients with 228 lesions were included. FNA of 106 and 122 lesions each was performed in the S+ and S− groups, respectively. FNA sites included pancreas [41 (18%)], lymph node [125 (55%)], liver [20 (9%)], adrenal [21 (9%)] and others [21 (9%)]. No significant differences in the cellularity (P = 0.37), contamination (P = 0.18), significant blood (P = 0.42) and adequacy of specimen (P = 0.45) were found between S+ and S− specimens. There was no statistically significant difference in the diagnostic yield of malignant lesions (P = 0.48).

Conclusions

The use of stylet during FNA does not appear to confer any advantage with regards to the adequacy of specimen or diagnostic yield of malignancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) has become widely accepted as an effective modality in the diagnostic evaluation of lesions in the gastrointestinal tract and mediastinum as well as other adjacent organ sites [1]. FNA under EUS guidance provides clinically important diagnostic and prognostic information–pathologic confirmation of the presence (or absence) of malignancy and/or metastasis to secondary sites (‘histologic staging’) [2, 3].

The most common indications of EUS-FNA include evaluation of pancreatic masses, mediastinal and intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy, liver masses, left adrenal masses and gastrointestinal submucosal lesions [4–7]. The strongest support for EUS-FNA has been documented in cases in which other biopsy techniques such as computerized tomographic (CT) guided biopsy or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) have failed [1]. EUS-FNA has been reported to provide a diagnostic yield of 80–95% after other diagnostic attempts have failed [5, 8]. Thus, EUS-FNA is fast becoming an indispensable tool for gastroenterologists that can have a tremendous impact on patient management.

Various techniques have been described to optimize accuracy, efficiency, and quality of EUS-FNA specimens. FNA is typically performed using a 22- or 25-gauge needle with a stylet under EUS guidance [9–15]. There are several variables that impact the overall diagnostic yield of EUS-FNA such as skill and experience of the endosonographer and cytopathologist, type and diameter of the needle, ability to puncture the lesion, use of aspiration/suction as opposed to reliance on the capillary and shearing action of the needle, number of passes performed, sample preparation, immediate cytologic evaluation in the procedure room, and pathologic interpretation [10, 16–23].

All commercially available EUS-FNA systems include a removable stylet. It is currently believed that the use of a stylet during EUS-FNA helps prevent clogging of the lumen of the needle by gut wall tissue (as the needle traverses it) which could limit the ability to aspirate cells from the target lesion. Use of stylet is thought to improve the quality of specimens and hence enhance the diagnostic yield of specimens obtained. Although this is a logical assumption, there are no data demonstrating clearly that the use of a stylet increases the diagnostic yield or improves the quality of specimens obtained by EUS-FNA.

The specific aims of this study were to compare specimens obtained by EUS-FNA with and without stylet for (i) the degree of cellularity, adequacy, contamination, and amount of blood and (ii) the diagnostic yield of malignancy.

Methods

Study Design

This was a retrospective, case–control study that was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Kansas City Veterans Administration Medical Center. A waiver of informed consent was obtained through the IRB.

Patients

Using the pathology electronic medical record system at the Kansas City Veterans Administration Medical Center, all patients undergoing EUS-FNA for evaluation of solid lesions (pancreatic mass, liver mass, left adrenal mass, gastrointestinal submucosal lesions, lymph nodes, mediastinal mass) from January 2006 to April 2009 were identified. Only patients with at least 6 months of radiologic or clinical follow-up post-EUS-FNA were included in this study. The computerized patient record system was reviewed to obtain patient demographics, site of lesion, EUS characteristics of the lesion, and radiologic, endoscopic and clinical follow-up information by one of two investigators (NG, SW).

EUS-FNA Technique

EUS was performed with a curved linear array echoendoscope (GF-UC30P or GF-UCT30, Olympus, America, Inc.) by two experienced (>500 cases) endosonographers (AR, MO). The procedures were carried out with the patients in the left lateral position under moderate sedation with intravenous midazolam and intravenous meperidine or fentanyl. FNA was performed with a 22-gauge needle (Cook Medical, Inc., Winston Salem, NC) under EUS guidance with continuous suction using a 10-mL syringe. All EUS-FNA procedures performed from January 2006 to September 2007 were with the stylet while all those from October 2007 until April 2009 were without the stylet. It is routine practice at this tertiary referral center to have a cytopathologist in the room at the time of EUS-FNA.

Assessment of Cytology and Final Diagnosis

All cytology slides prepared from the EUS-FNA procedures were retrieved and de-identified. These slides were then randomly allocated to two experienced cytopathologists (MR, OU) who were blinded to the FNA technique (with or without stylet). All the slides from one patient were allocated to one cytopathologist. The distribution of patients undergoing EUS-FNA with and without stylet was equal between the two cytopathologists. All slides were evaluated for five criteria—cellularity, contamination, amount of blood, adequacy of specimen and final diagnosis (Table 1). An overall impression for these criteria was based on review of all slides and results were entered in a case report form followed by creation of an ACCESS database. Final interpretation for every lesion was provided based on review of all the on-site slides [stained with Romanowsky’s stain (DiffQuik)], slides prepared on-site and stained later (Papanicolaou stain), and examination of thin-layer cytology or cytospin/cell block material prepared from the cellular material placed in the Saccomano or cytolyte solution.

The ideal benchmark for EUS-FNA performance requires a criterion standard of either surgical pathology or long-term follow-up [10]. The composite criterion standard for each lesion was based on the EUS-FNA cytology report, surgical pathology (if available), repeat radiological imaging, and clinical follow-up. A final diagnosis of a benign lesion was made if the cytologic specimen was not definite for malignancy (normal, atypical, suspicious) and confirmed by surgical pathology, stable follow-up imaging, or stable clinical course for at least 6 months follow-up. Lesions were considered malignant if the EUS-FNA cytology or subsequent surgical histologic specimen from the lesion was definite for malignancy, or if there was clinical deterioration over 6 months of follow-up or increasing size of the lesion on radiological imaging during follow-up. The final diagnoses were made by consensus review of the patients’ electronic medical records by two investigators.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata/IC Version 10.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Direct comparisons were made between the stylet group and the without stylet group. All lesions were treated as independent observations even if more than one lesion was sampled in a single patient. The Wilcoxon-rank sum test was used for continuous variables including age and lesion size. Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables including gender, race, lesion location, cellularity, contamination, amount of blood, adequacy of specimen and diagnosis. Results were considered statistically significant if P value <0.05.

Results

A total of 162 patients [mean age 64.7 years (SD 11.2), 97.5% males, 78.7% Caucasians] with 228 lesions met the study inclusion criteria. Lesion sites included pancreas [41 (18%)], lymph nodes [125 (54.8%)], liver [20 (8.8%)], adrenal [21 (9.2%)], and others [21 (9.2%)]. The mean number of passes in the entire cohort was 3.7 (SD 1.3); in the pancreas 4.6 (SD 1.3) and lymph nodes 3.6 (SD 1.2). Overall, cytologic diagnoses were malignant 85 (27.2%), atypical 18 (7.9%), suspicious 8 (3.5%), benign 99 (43.4%), and inadequate 18 (7.9%) in the entire cohort. A total of 72 patients with 106 lesions underwent EUS-FNA with a stylet and 90 patients with 122 lesions underwent EUS-FNA without a stylet.

The baseline patient and lesion characteristics between the two groups have been highlighted in Table 2. Although there was a higher proportion of Caucasians in the no stylet group, there was no statistically significant difference in mean age, gender, site and mean size of lesion between the groups. The number of lesions in both groups was equally distributed between the two cytopathologists (OU 114, MO 114). No significant differences in the cellularity (P = 0.37), contamination (P = 0.18), significant blood (P = 0.42), and adequacy of specimen (P = 0.45) were found between with and without stylet specimens (Table 3). EUS-FNA with stylet group had a higher proportion of specimens with only a minimal amount of blood compared to EUS-FNA without stylet [20 (18.9%) vs. 9 (7.4%), P = 0.02]. There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of specimens with a moderate [43 (40.6%) vs. 57 (46.7%), P = 0.42] or significant [43 (40.6%) vs. 56 (45.9%), P = 0.42] amount of blood between the two groups. There was no statistically significant difference in the diagnostic yield of malignant lesions [with stylet: 41/106 (38.7%) vs. without stylet: 44/122 (36.1%), P = 0.48]. Similarly, on a patient based analysis, there was no difference between the two groups [with stylet: 36/72 (50%) vs. without stylet: 40/90 (44.4%), P = 0.48].

The final diagnosis of malignancy was designated to 94 patients and 116 lesions. The diagnostic yield of EUS-FNA for malignancy in pancreatic lesions was 61% (68.3% if suspicious lesions are included in the malignant category). Based on the final diagnosis, the accuracy of EUS-FNA for pancreatic lesions was 85.7% (96.4% if suspicious lesions are included in the malignant category). The diagnostic yield of EUS-FNA for malignancy in lymph nodes was 25.6% (28.8% if suspicious lesions are included in the malignant category). Based on the final diagnosis, the accuracy of EUS-FNA for lymph nodes was 62.7% (70.5% if suspicious lesions are included in the malignant category). In the stylet group 43 patients and 58 lesions had a final diagnosis of malignancy, whereas 51 patients and 58 lesions had a final diagnosis of malignancy in the no stylet group (P = 0.69). Of the malignant lesions, S+ passes were positive in 41/58 (71%) vs. 43/58 (74%) for S− passes (P = 0.29). If suspicious lesions are included in the malignant category, S+ passes were positive in 47/58 (81%) vs. 45/58 (77.5%) for S− passes (P = 0.82).

Discussion

EUS-FNA has emerged as an accurate and safe method for diagnosing and staging gastrointestinal and some non-gastrointestinal malignancies [24]. Despite the lack of evidence, use of stylet during EUS-FNA is assumed to improve the quality of specimen obtained and the diagnostic yield. At the present time, it is common practice to re-insert the stylet back into the needle prior to each FNA pass. However, the use of stylet during EUS-FNA procedure is cumbersome, labor intensive, prolongs procedure time and administered dosage of sedation. Use of stylet also increases the cost of EUS-FNA needle systems. In some circumstances, the stylet may actually make EUS-FNA more difficult as it may be hard to advance or remove the stylet once the target lesion has been punctured. This tends to occur when the echoendoscope is looped or the needle is bent while accessing the lesion and a larger bore (19 gauge) needle is being used. In addition, reinserting the stylet back into the needle for the next pass can be difficult and sometimes impossible especially if there is a kink or bend in the needle sheath. On the other hand, the stylet may be needed to stiffen the needle to allow puncture into a fibrotic lesion. The stylet is also useful for carefully expressing the material in a controlled manner onto the slides rather than blowing the material onto the slides with air.

This retrospective study compared specimens obtained by EUS-FNA with and without stylet for the diagnostic yield of malignancy and cytologic characteristics such as cellularity, contamination, amount of blood and specimen adequacy. These cytologic characteristics were compared by using well-defined criteria. This study demonstrates that comparison of EUS-FNA technique with and without stylet yielded no significant differences in cellularity (P = 0.37), contamination (P = 0.18), or adequacy of specimen (P = 0.45). EUS-FNA without stylet group had a lower proportion of specimens with minimal amount of blood (P = 0.02); however, there was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of specimens with a moderate/significant amount of blood. There was no difference in the diagnostic yield of malignancy (EUS-FNA with stylet: 50% vs. EUS-FNA without stylet: 44.4%, P = 0.48) between the two techniques.

The data comparing the effectiveness of EUS-FNA with stylet to FNA without stylet is limited. In a prospective, randomized controlled trial of EUS-FNA with and without a stylet, Sahai et al. compared the adequacy, the bloodiness, and the yield of FNA samples obtained with a stylet to FNA without a stylet. A total of 111 patients undergoing EUS-FNA of solid lesions performed with a 22-guage needle by a single experienced endosonographer were included. Passes were performed with or without stylet in a 1:2 ratio. From a total of 309 needle passes (mean 2.3 passes/lesion), there were 118 (38%) passes in the stylet arm and 191 (62%) in the without stylet group. In this study, the use of stylet for EUS-FNA was associated with a reduced specimen adequacy (75% vs. 87%, P = 0.013) and more bloody specimen (75% vs. 52%, P < 0.0001) [25]. Similarly, another retrospective study compared the yield and number of passes required to obtain adequate samples among cases with and without stylet in 47 consecutive patients and 54 sites (pancreas 55%, lymph nodes 14%, liver/biliary 13%, and gastric or others 17%) with the predominant use of 25-gauge needles. No difference in cellularity, contamination and diagnostic yield was reported between the two techniques [26].

A few limitations of this study merit consideration. The main limitation of this study was the retrospective design and comparison of the two techniques in two separate time-frames. Although predefined criteria were used to compare the cytologic characteristics of the specimens, there is still a certain amount of subjectivity in their assessment by cytopathologists. However, the cytopathologist were blinded to the technique used to obtain the specimens in order to obviate any bias in reporting. This study did not assess the interobserver agreement among pathologists in the assessment of EUS-FNA specimens. Variability in the diagnosis of malignancy among pathologists and its impact on the results cannot be excluded. Only 22-gauge EUS-FNA needles were used in this study, and hence these results may not be generalizable to other needle sizes. Suction was used in all patients which may have increased the amount of blood. More than half of the lesions in this study were lymph nodes with a relatively smaller number of lesions from the pancreas. The relatively small sample size may have prevented the detection of difference in cytologic characteristics and diagnostic yield between the two techniques for specific lesion sites. The follow-up period for patients with no surgical pathology was relatively short. Given the longitudinal nature of the study, the impact of increasing experience of the endosonographer with time on the tissue acquisition by EUS-FNA cannot be excluded.

Thus the practice of using a stylet during EUS-FNA is questionable in as to whether it improves the quality of the specimen obtained. Results of this study challenge the current belief that the use of a stylet during EUS-FNA helps prevent clogging of the lumen of the needle by gut wall tissue. The diagnostic yield, adequacy and quality of specimens obtained by EUS-FNA without a stylet were found to be equivalent to that with a stylet. If these results are confirmed by prospective multicenter randomized controlled trials, it would be reasonable not to use a stylet during EUS-FNA. This would make the procedure easier, less labor intensive, as well as more time- and cost-efficient.

References

Erickson RA. EUS-guided FNA. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:267–279.

Kulesza P, Eltoum IA. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration: sampling, pitfalls, and quality management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1248–1254.

Bardales RH, Stelow EB, Mallery S, et al. Review of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34:140–175.

Chen VK, Eloubeidi MA. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration is superior to lymph node echofeatures: a prospective evaluation of mediastinal and peri-intestinal lymphadenopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:628–633.

Harewood GC, Wiersema MJ. Endosonography-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy in the evaluation of pancreatic masses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1386–1391.

Vander Noot MR III, Eloubeidi MA, Chen VK, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal tract lesions by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Cancer. 2004;102:157–163.

DeWitt J, LeBlanc J, McHenry L, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology of solid liver lesions: a large single-center experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1976–1981.

Gress F, Gottlieb K, Sherman S, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy of suspected pancreatic cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:459–464.

Siddiqui UD, Rossi F, Rosenthal LS, et al. EUS-guided FNA of solid pancreatic masses: a prospective, randomized trial comparing 22-gauge and 25-gauge needles. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1093–1097.

Savides TJ, Donohue M, Hunt G, et al. EUS-guided FNA diagnostic yield of malignancy in solid pancreatic masses: a benchmark for quality performance measurement. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:277–282.

Eloubeidi MA, Chen VK, Eltoum IA, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of patients with suspected pancreatic cancer: diagnostic accuracy and acute and 30-day complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2663–2668.

Chang KJ, Nguyen P, Erickson RA, et al. The clinical utility of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis and staging of pancreatic carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:387–393.

Gress FG, Hawes RH, Savides TJ, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy using linear array and radial scanning endosonography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:243–250.

Gress FG, Savides TJ, Sandler A, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography, fine-needle aspiration biopsy guided by endoscopic ultrasonography, and computed tomography in the preoperative staging of non-small-cell lung cancer: a comparison study. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:604–612.

Yusuf TE, Ho S, Pavey DA, et al. Retrospective analysis of the utility of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) in pancreatic masses, using a 22-gauge or 25-gauge needle system: a multicenter experience. Endoscopy. 2009;41:445–448.

Fritscher-Ravens A, Topalidis T, Bobrowski C, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in focal pancreatic lesions: a prospective intraindividual comparison of two needle assemblies. Endoscopy. 2001;33:484–490.

Mertz H, Gautam S. The learning curve for EUS-guided FNA of pancreatic cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:33–37.

Jhala NC, Jhala D, Eltoum I, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy: a powerful tool to obtain samples from small lesions. Cancer. 2004;102:239–246.

Puri R, Vilmann P, Saftoiu A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle sampling with or without suction for better cytological diagnosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:499–504.

Wallace MB, Kennedy T, Durkalski V, et al. Randomized controlled trial of EUS-guided fine needle aspiration techniques for the detection of malignant lymphadenopathy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:441–447.

Klapman JB, Logrono R, Dye CE, et al. Clinical impact of on-site cytopathology interpretation on endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1289–1294.

Erickson RA, Sayage-Rabie L, Beissner RS. Factors predicting the number of EUS-guided fine-needle passes for diagnosis of pancreatic malignancies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:184–190.

Eltoum IA, Chen VK, Chhieng DC, et al. Probabilistic reporting of EUS-FNA cytology: Toward improved communication and better clinical decisions. Cancer. 2006;108:93–101.

Adler DG, Jacobson BC, Davila RE, et al. ASGE guideline: complications of EUS. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:8–12.

Sahai AV, Paquin S, Gariepy G. A prospective comparison of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration results obtained in the same lesion, with and without the needle stylet. Endoscopy. 2010;42(11):900–903.

Devicente N, Hawes R, Hoffman B et al. The yield of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) is not affected by leaving out the stylet. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:AB335.

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Sachin Wani and Neil Gupta contributed equally.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wani, S., Gupta, N., Gaddam, S. et al. A Comparative Study of Endoscopic Ultrasound Guided Fine Needle Aspiration With and Without a Stylet. Dig Dis Sci 56, 2409–2414 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-011-1608-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-011-1608-z