Abstract

Osteoclasts are multinucleated cells that play a crucial role in bone resorption, and are formed by the fusion of mononuclear osteoclasts derived from osteoclast precursors of the macrophage lineage. Compounds that specifically target functional osteoclasts would be ideal candidates for anti-resorptive agents for clinical applications. In the present study, we investigated the effects of luteolin, a flavonoid, on the regulation of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL)-induced osteoclastogenesis, functions and signaling pathway. Addition of luteolin to a coculture system of mouse bone marrow cells and ST2 cells in the presence of 10−8 M 1α,25(OH)2D3 caused significant inhibition of osteoclastogenesis. Luteolin had no effects on the 1α,25(OH)2D3-induced expressions of RANKL, osteoprotegerin and macrophage colony-stimulating factor mRNAs. Next, we examined the direct effects of luteolin on osteoclast precursors using bone marrow macrophages and RAW264.7 cells. Luteolin completely inhibited RANKL-induced osteoclast formation. Moreover, luteolin inhibited the bone resorption by mature osteoclasts accompanied by the disruption of their actin rings, and these effects were reversely induced by the disruption of the actin rings in mature osteoclasts. Finally, we found that luteolin inhibited RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis through the suppression of ATF2, downstream of p38 MAPK and nuclear factor of activated T-cells, cytoplasmic, calcineurin-dependent 1 (NFATc1) expression, respectively. Taken together, the present results indicate that naturally occurring luteolin has inhibitory activities toward both osteoclast differentiation and functions through inhibition of RANKL-induced signaling pathway as well as actin ring disruption, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bone is a dynamic tissue that is constantly destroyed or resorbed by osteoclasts and then replaced by osteoblasts in a physiological process referred to as bone remodeling. Osteoclasts originate from hematopoietic precursor cells of the phagocyte lineage and differentiate into multinucleated cells by the fusion of mononuclear progenitors (Suda et al. 1991). This process consists of multiple steps, including differentiation of osteoclast precursors into mononuclear osteoclasts, fusion of mononuclear preosteoclasts into mature multinucleated osteoclasts and activation of osteoclasts to resorb bone (Boyle et al. 2003; Rodan and Martin 2000; Teitlebaum 2000; Chambers 2000). Therefore, natural compounds that specifically inhibit these steps could be developed as anti-resorptive drugs for the treatment of metabolic bone disorders characterized by excessive osteoclastic bone resorption.

Receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) is a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily that is expressed in osteoblasts (Darnay and Aggarwal 1999). It interacts with the osteoclast cell surface receptor RANK, which in turn recruits TNFR-associated factors (TRAFs) (Darnay et al. 1998; Wong et al. 1998), and plays a crucial role in the osteoclast differentiation axis. The downstream intracellular signaling mediated by RANK in osteoclast progenitor cells includes TRAF6-dependent activation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB via the inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB) kinase (IKK)-IκB pathway and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) such as extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), p38 MAPK and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) (Boyle et al. 2003; Lerner 2004; Teitelbaum and Ross 2003). In addition, immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif-mediated costimulatory signals have been shown to be required for expression of nuclear factor of activated T-cells, cytoplasmic, calcineurin-dependent 1 (NFATc1), the transcription factor believed to be crucial for osteoclast differentiation (Koga et al. 2004; Mocasi et al. 2004).

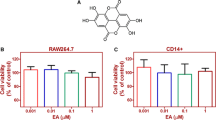

Flavonoids are naturally occurring polyphenolic compounds that are present in many plants and plant-based foods and possess potent antioxidant, anticarcinogenic, immunomodulatory and antibacterial activities (De Smet 2002; Gohil and Packer 2002; Birt et al. 2001; Ross and Kasum 2002). In particular, luteolin (Fig. 1a), a common dietary flavonoid compound, has been found in various herbal extracts including celery, green pepper, perilla leaf, perilla seed and chamomile extracts, and is widely known to exert various biological activities including anti-inflammatory and anticancer effects. Oral administration of luteolin to mice was found to suppress inflammatory responses in animal models of acute and chronic inflammation (Ziyan et al. 2007). Moreover, luteolin directly inhibits lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced IKK activity and decreases TNF-α gene expression in intestinal epithelial cells and bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (Kim and Jobin 2005). Despite these various activities, the beneficial effects of luteolin on bone metabolism have not been scientifically evaluated in previous reports.

Luteolin inhibits 1α,25(OH)2D3-induced osteoclastogenesis in co-cultures but does not affect osteoblasts. a Sturucture of luteolin. b ST2 cells and BMCs were cocultured in 24-well plates for 5 days in the presence of 1α,25(OH)2D3 and luteolin. After 5 days, the cells were fixed and stained for TRAP (left panels). c Effects of luteolin on cell viability of ST2 cell. Cell viability was determined by MTT assays (left panels). ST2 cells were cultured for 24 h in the presence of 1α,25(OH)2D3 (10−8 M) and luteolin (0, 1, 3 or 10 μM). Total RNA was extracted from the cells, and the expressions of RANKL, OPG and M-CSF mRNAs were analyzed by RT–PCR (right panels). *p < 0.01, **p < 0.05

In the screening for anti-resorptive agents from food bioactive components, we found that luteolin inhibits osteoclast differentiation. In the present study, we investigated the effects of luteolin on RANKL-induced signaling pathways and bone resorption of mature osteoclasts.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Male Std ddY mice (6–9 weeks of age) were purchased from Japan SLC Co. (Hamamatsu, Japan). The animal protocols and procedures used in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chubu University. Recombinant soluble RANKL (sRANKL) was purchased from PeproTech EC Ltd. (London, UK). PD98059 was obtained from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1α,25-(OH)2D3] and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). Anti-JNK, anti-phospho-JNK, anti-p38 MAPK, anti-phospho-p38 MAPK and anti-IκB rabbit polyclonal antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology Inc. (Beverly, MA). An anti-NFATc1 mouse polyclonal antibody was purchased from Affinity Bio Reagents Co. Ltd. (Rockford, IL). An ATF2, GAPDH mouse polyclonal antibody, SB203580 and SB202190 was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Specific PCR primers for mouse RANKL, osteoprotegerin (OPG), macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were synthesized by Life Technologies Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). All other chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade.

Cell culture

The murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 and mouse clonal stromal cells from bone marrow (ST2) were obtained from the RIKEN Cell Bank (Tsukuba, Japan). The cells were maintained in α-MEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS).

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was measured by the MTT assay. Bone marrow macrophages (BMMs) and RAW264.7 cells were cultured under the same conditions used for osteoclastogenesis experiments, and MTT reagent was added at 3 h before the end of the culture. The supernatants were carefully removed, dissolved in DMSO and measured for their absorbances at 570 nm using a microplate reader.

Mouse BMMs and cocultures

Bone marrow cells (BMCs) were obtained from the long bones of 4–6-week-old ddY male mice. In the coculture system, BMCs were cocultured with ST2 cells on 24-well plates in the presence of 10−8 M 1α,25-(OH)2D3 for 5 days. After the coculture, some of the cells were fixed and stained for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), a marker enzyme for osteoclasts. To obtain mature osteoclasts, BMCs (1 × 107 cells) and ST2 cells (1 × 106 cells) were co-cultured in collagen gel-coated 100 mm plates for 5–6 days in α-MEM containing 10% FBS, 10−8 M 1α,25(OH)2D3 and 10−6 M PGE2. The plates were treated with collagenase and whole cells were harvested for use in subsequent experiments.

PCR amplification of reverse-transcribed mRNA

For RT–PCR analyses, ST2 cells were cultured in α-MEM containing 10% FBS and 10−8 M 1α,25(OH)2D3 in 60 mm dishes. After culture for 24 h, total cellular RNA was extracted from ST2 cells using TRIzol solution (Life Technologies Inc.). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from the total RNA with random primers and subjected to PCR amplification with Ex Taq polymerase (Takara Biochemicals, Shiga, Japan) using the following specific PCR primers: mouse RANKL, 5′-CGC TCT GTT CCT GTA CTT TCG AGC G-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCG TGC TCC CTC CTT TCA TCA GGT T-3’ (reverse); mouse OPG, 5’-TGG AGA TCG AAT TCT GCT TG-3’ (forward) and 5′-TCA AGT GCT TGA GGG CAT AC-3′ (reverse); mouse M-CSF, 5′-GAG AAG ACT GAT GGT ACA TCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTA TAC TGG CAG TTC CAC C-3′ (reverse); mouse GAPDH, 5′-ACC ACA GTC CAT GCC ATC AC-3′ (forward) and 5′- TCC ACC ACC CTG TTG CTG TA-3′ (reverse). The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in 2% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining under UV light illumination. The sizes of the PCR products for mouse RANKL, OPG, M-CSF and GAPDH were 587, 720, 516 and 452 bp, respectively.

Osteoclast differentiation

RAW264.7 cells were seeded in 96-well plates (3 × 103 cells/well) and cultured in the presence of RANKL (50 ng/mL) for 3 days. Mature osteoclasts were formed in RAW264.7 cell cultures in the presence of RANKL and PD98059 (20 μM) for 4 days. To obtain BMMs, BMCs were cultured for 3 days in α-MEM containing 10% FBS and M-CSF (50 ng/mL) in 60 mm dishes. After culture for 1 day, non-attached cells in the culture plates were collected and used as BMMs. In the BMM culture system, BMMs were cultured in 96-well plates in the presence of M-CSF (50 ng/mL) for 3 days, treated with RANKL (100 ng/mL) and cultured for a further 3 days. The cells were then sequentially fixed with 10% formalin for 10 min and ethanol for 1 min, and dried. Measurement of TRAP activity and staining for TRAP were performed. TRAP-positive multinucleated cells containing more than 5 nuclei were counted.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed with RIPA buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1% NP-40, 1 mM Na3VO4 and 1 × protease inhibitor cocktail). The extracted proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE and electrotransferred onto PVDF membranes. The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against JNK, phospho-JNK, p38 MAPK, phospho-p38 MAPK, IκB, ATF2, phosphor-ATF2, NFATc1 and GAPDH, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. Immunocomplexes were visualized by a chemiluminescence reaction using ECL reagents from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Buckinghamshire, UK).

Pit formation and actin ring formation assays

Mature osteoclasts were obtained from mouse cocultures on collagen gel-coated dishes as described above. For resorption pit assays, aliquots of the crude mature osteoclast preparations were placed on dentin slices in 96-well plates (Suda et al. 1997). After preincubation for 2 h, the dentin slices were transferred to 48-well plates (1 dentin slice/well) containing 0.3 mL of α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, and further cultured with or without luteolin for 48 h. Resorption pits on the dentin slices were visualized by staining with toluidine blue. The number of resorption pits on each slice was counted. Actin rings of osteoclasts were detected by staining actin filaments with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin. Osteoclasts were formed from RAW cell cultures in the presence of RANKL (100 ng/mL) and PD98059 (20 μM) and treated with luteolin for 24 h. At the end of incubation, osteoclasts were stained for TRAP activity and TRAP-positive osteoclasts were stained with rhodamin-conjugated phalloidin in the dark. The distribution of actin rings was visualized and detected under a fluorescence microscope.

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed by an unpaired two-tailed Student`s t-test assuming unequal variances. Values of p < 0.01 were considered to indicated statistical significance.

Results

Luteolin inhibits 1α,25(OH)2D3-induced differentiation of osteoclasts but not osteoblasts

To clarify the effects of luteolin on osteoclastogenesis, firstly we examined that the effect of luteolin on coculture of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. BMCs were cocultured with ST2 cells in the presence of 1α,25(OH)2D3. Many TRAP-positive osteoclasts were formed in the cocultures within 5 days in response to 1α,25(OH)2D3 (Fig. 1b). We found that luteolin dose-dependently decreased the numbers of osteoclasts remaining on the culture plates without affecting the numbers of osteoblasts. Complete inhibition of osteoclast formation was observed in the cocultures treated with luteolin at 10 μM. To clarify the effect of luteolin on osteoblasts, ST2 cells were stimulated with 1α,25(OH)2D3. ST2 cells cultured with the increasing concentration of luteolin and cell growth of osteoblasts was examined by MTT assay (Fig. 1c). The cell viability was not affected by luteolin at 10 μM. Next, we examined its effects on the expressions of RANKL, OPG (a decoy receptor of RANKL) and M-CSF in osteoblasts treated with 1α,25(OH)2D3 at 10−8 M. Treatment of osteoblasts with 1α,25(OH)2D3 enhanced the expression of RANKL, suppressed the expression of OPG and sustained the expression of M-CSF. Luteolin had no effects on the upregulation of RANKL mRNA expression and also had no effects on the OPG and M-CSF mRNA expression levels in osteoblasts. These results suggest that luteolin suppressed osteoclast formation through direct inhibition of osteoclasts but had no effect on osteoblasts.

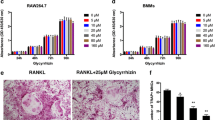

Luteolin inhibits the RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation from osteoclast precursors

To determine the effects of luteolin on osteoclast formation from osteoclast progenitor cells in the absence of osteoblasts, we used BMMs and RAW264.7 cells. Mouse BMMs and RAW264.7 cells were incubated with luteolin in the presence of RANKL and M-CSF, and sRANKL and PD98059, respectively, and allowed to grow and differentiate into osteoclasts. (PD98059 is known to increase TRAP-positive cell formation induced by RANKL in RAW264.7 cell culture (Hotokezaka et al. 2002); thus we used PD98059 to rapidly prepare a high number of mature osteoclasts). As shown in Fig. 2, RANKL dramatically induced osteoclast formation in both cell types. Luteolin inhibited the osteoclast formation induced by RANKL at concentrations of 3–10 μM in a dose-dependent manner. However, as detected by MTT assays, the viabilities of BMMs and RAW264.7 cells were not affected by luteolin at concentrations below 10 μM. These results suggest that luteolin directly acts on osteoclast progenitors, and subsequently inhibits osteoclast formation.

Luteolin inhibits RANKL-induced osteoclast formation in mouse BMMs and RAW264.7 cells. a RAW264.7 cells and BMMs were cultured with RANKL (100 ng/mL) and M-CSF (50 ng/mL) in the presence of luteolin for 72 h in 96-well plates. After culture for 3 days, the cells were fixed and determined for TRAP (black bar; ■). The numbers of TRAP-positive multinucleated cells containing more than 5 nuclei were counted as osteoclasts. Cell viability was determined by MTT assays (white bar; □). b BMMs in 96-well plates were stained for TRAP. **p < 0.05

Luteolin does not affect RANKL-induced signal cascades but does affect NFATc1 expression

To elucidate the inhibitory mechanism and pathway influenced by luteolin, RAW264.7 cells were treated with luteolin and simultaneously stimulated with RANKL for 0–30 min. A key signaling event induced by the binding of RANKL to RANK was the activation of MAPKs and IκB signaling. The phosphorylation levels reached their maximal levels within 15 min and then returned to the basal levels in response to RANKL (Fig. 3a). Activation of p38 MAPK, JNK and IκB was not impaired after treatment with luteolin. We examined the effects of luteolin on ATF2, downstream of p38 MAPK, signaling pathway and compared with SB203580 and SB202190, p38 specific inhibitor (Fig. 3b). RANKL stimulated phosphorylation of ATF2 and addition of luteolin inhibited its phosphorylation. Furthermore, we examined the effects of luteolin on NFATc1 signaling pathway (Fig. 3c). NFATc1 is a terminal transcription factor that plays a critical and fundamental role in osteoclast development, and a lack of this factor leads to arrest of osteoclastogenesis (Teitelbaum 2004). Luteolin strongly impaired the RANKL-stimulated expression of NFATc1 protein. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that luteolin inhibits osteoclast formation through downregulation of NFATc1.

Effect of luteolin on RANKL-induced signaling pathways. a RAW264.7 cells were preincubated in the presence of luteolin (10 μM) for 30 min and then treated with RANKL (100 ng/mL) for indicated times. The levels of phosphorylated or non-phosphorylated p38, JNK, and IκB were determined. b RAW264.7 cells were incubated with luteolin (10 μM) and p38 inhibitor 10 μM. The cells were stimulated with RANKL (100 ng/mL) for 15 min and assessed for the phosphorylation of ATF2. c RAW264.7 cells were incubated with luteolin (10 μM). The cells were stimulated with RANKL (100 ng/mL) for 4 days. The level of NFATc1 was determined by Western blotting for indicated times. Cell lysates were collected and separated by 10% SDS–PAGE. The results are representative of three independent experiments

Luteolin suppresses pit formation on bone slices and reversibly disrupts actin rings

To investigate the inhibitory effects of luteolin on bone function, we examined the effects of luteolin on the bone resorption induced by 1α,25(OH)2D3 and PGE2 in the mouse co-culture system. Osteoclasts formed by co-cultures with bone marrow cells and ST2 cells readily created resorption pits on dentine slices. Luteolin inhibited pit formation on the dentin slices in a dose-dependent manner. At 10 μM, luteolin inhibited the pit formation by approximately 90% (Fig. 4). Actin ring formation in mature osteoclasts is essential for the expression of their bone resorption activity. Next, we examined the effects of actin rings by staining with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin. When osteoclasts with actin rings were treated with luteolin for 24 h, the size was constricted and the actin rings were disrupted (Fig. 5a). In addition, when luteolin was removed after a 12 h treatment, the number of osteoclasts with actin rings was rescued to 90% of the control levels by 24 h (Fig. 5b). These suppressive effects of luteolin on bone resorption were correlated with its disruptive effects on actin rings in osteoclasts.

Effect of luteolin on osteoclast function using pit formation assay. Osteoclasts collected from co-cultures were placed on dentin slices in the presence of luteolin for 24 h. Resorption pits on the slices were stained with toluidine blue solution. Resorption was quantified on the number of pits (upper panels) and resorption areas were observed under a microscope (lower panels). *p < 0.01, **p < 0.05

Effects of luteolin on the survival of mature osteoclasts. a RAW264.7 cells in 96-well plates were cultured with PD98059 (20 μM) in the presence of RANKL (100 ng/mL) for 4 days. Osteoclasts with actin rings were treated with luteolin (10 μM) in the presence of RANKL (100 ng/mL) and PD98059 (20 μM) for 24 h. After the cultures, the cells were fixed and stained for TRAP (upper panels), followed by staining of actin with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (lower panels). b Mature osteoclasts were incubated with or without luteolin for 12 h in the presence of RANKL (100 ng/mL) and PD98059 (20 μM) (control group was described as “C”). After incubation, the luteolin was washed out and the osteoclasts were cultured in fresh medium with or without luteolin for an additional 12 h. After the cultures, the cells were fixed and stained for TRAP. The numbers of TRAP-positive multinucleated cells containing more than 5 nuclei were counted as osteoclasts. **p < 0.05

Discussion

Flavonoids possess several biological and pharmacological activities including anticancer, antimicrobial, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory and antioxidant activities (Middleton et al. 2000). One of the flavonoids, luteolin (3′,4′,5,7-tetrahydroxyflanone), is found in many herbal extracts including celery, green pepper, perilla leaf, perilla seed and chamomile extracts (Ziyan et al. 2007). Although numerous studies have indicated the efficacy of luteolin, including its anti-inflammatory and anticancer effects, its targets and the mechanism of its action related to bone have not been evaluated. Therefore, the aims of this study were to evaluate the effects of luteolin on osteoclasts differentiation and function.

In the present study, we examined 1α,25-(OH)2D3-induced osteoclastogenesis using a coculture system of ST2 cells and BMCs, as well as RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis with BMMs, to define the direct effects of luteolin. We found that luteolin effectively inhibited osteoclast formation in mouse cocultures, and that RANKL-induced osteoclast formation in mouse BMM and RAW264.7 cell cultures was also inhibited by luteolin at 10 μM. However, RT–PCR analyses showed that luteolin failed to affect the expressions of RANKL, OPG and M-CSF mRNAs in osteoblasts regardless of the presence or absence of 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment. These results suggest that luteolin has direct inhibitory effects on osteoclast progenitor cells but not on osteoblasts.

During the osteoclast differentiation process, the expressions of several genes, including MAPKs, are specifically stimulated, and IκB signals. And costimulatory immunoreceptors lead to the robust induction of NFATc1, which is a necessary and sufficient factor for osteoclast differentiation (Takayanagi 2007; Walsh et al. 2006; Takayanagi 2005, 2002; Asagiri et al. 2005). We examined whether luteolin could modulate the expressions of these genes. Luteolin did not affect RANKL-induced MAPK expression and activation. With respect to innate signaling, several in vitro studies have investigated the inhibitory activities of luteolin against anti-inflammatory actions (Xagorari et al. 2001; Kim et al. 2003). According to Comalada et al. (2006), luteolin is able to stimulate the expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. In addition, luteolin inhibits LPS-induced IκB phosphorylation and TNF-α secretion by macrophages in vitro and has anti-inflammatory activities in mice (Kim and Jobin 2005; Kotanidou et al. 2002). In contrast to these findings, our results showed that luteolin had no inhibitory effects on IκB signal expression. These discrepancy may be explained by differences in the cell types and developmental stages, and the receptor subtype specificities differ among ligands. But luteolin affects the phosphorylation of ATF2, downstream of p38 MAPK signaling pathway. Activated p38 MAPK phosphorylates transcription factor ATF2, which, in turn, induces transcription of the target genes (Cobb and Goldsmith 1995; Whitmarsh and Davis 1996). It was shown that the expression of dominant-negative forms of p38 MAPK and MKK6 in RAW264.7 cells inhibited RANKL-induced differentiation of RAW264.7 cells into osteoclasts (Matsumoto et al. 2000). Moreover, addition of luteolin to osteoclast cultures strongly inhibited the expression of NFATc1, which is a key transcription factor for the expressions of TRAP and other osteoclastogenesis-associated genes (Ikeda et al. 2004; Kim et al. 2005; Matsumoto et al. 2004; Sharma et al. 2007). Therefore, the effects of luteolin on osteoclastogenesis are probably mediated by ATF2, downstream of p38 MAPK pathway.

Osteoclasts have unique properties for resorbing bone. The most characteristic features of osteoclasts are the presence of ruffled borders and sealing zones. The sealing zones serve to attach osteoclasts to the bone surface and isolate the resorption areas from the surrounding areas (Chambers and Magnus 1982; Väänänen et al. 2000). It has been reported that disruption of the sealing zones suppresses the bone-resorbing activities of osteoclasts (Lakkakorpi and Väänänen 2004; Nakamura et al. 1991; Suzuki et al. 1996). In the present study, we have demonstrated that luteolin inhibits osteoclastic bone resorption. We examined whether the effects of luteolin were reversible based on the actin ring formation in mature osteoclasts. In our study, a 12 h treatment with luteolin at 10 μM induced disruption of the actin rings, which are essential for the expression of the bone resorption function, in mature osteoclasts by 80%. Furthermore, removal of luteolin after the 12 h treatment led to restoration of the actin rings in osteoclasts to 90% of the levels in the control cultures. These results indicated that the luteolin-treated non-functional osteoclasts with disrupted actin rings were still alive. These facts suggest that the inhibitory effects of luteolin on pit formation mainly result from its disruptive effect on actin rings.

Several lines of evidence indicate that modulation of osteoclastogenesis through RANKL/RANK signaling can be an effective therapeutic strategy for bone disorders. The results of the present study suggest that dietary phytochemicals have beneficial effects on bone disorders, including osteoporosis and rheumatoid arthritis, which are mediated through the inhibition of osteoclast function. Although our findings are preliminary and have limitations, further studies on luteolin may provide new insights toward understanding the mechanisms of osteoclast differentiation and functions.

References

Asagiri M, Sato K, Usami T et al (2005) Autoamplification of NFATc1 expression determines its essential role in bone homeostasis. J Exp Med 202:1261–1269

Birt DF, Hendrich S, Wang W (2001) Dietary agents in cancer prevention: flavonoids and isoflavonoids. Phamacol Ther 90:157–177

Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Laccey DL (2003) Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature 423:337–342

Chambers TJ (2000) Regulation of the differentiation and function of osteoclasts. J Pathol 192:4–13

Chambers TJ, Magnus CJ (1982) Calcitonin alters behavior of isolated osteoclasts. J Pathol 136:27–39

Cobb MH, Goldsmith EJ (1995) How MAP kinase are regulated. J Biol Chem 270:14843–14846

Comalada Mònica, Ballester Isabel, Bailòn Elvira et al (2006) Inhibition of pro-inflammatory markers in primary bone marrow-derived mouse macrophages by naturally occurring flavonoids: analysis of the structure-activity relationship. Biochem Pharmacol 72:1010–1021

Darnay BG, Aggarwal BB (1999) Signal transduction by tumor necrosis factor and tumor necrosis factor related ligands and their receptors. Ann Rheum Dis 58:I2–I13

Darnay BG, Haridas V, Ni J et al (1998) Characterization of the intracellular domain of receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK): interaction with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors and activation of NF-κB and c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J Biol Chem 273:20551–20555

De Smet PA (2002) Herbal remedies. N Engl J Med 347:2046–2056

Gohil K, Packer L (2002) Bioflavonoid-rich botanical extracts show antioxidant and gene regulatory activity. Ann N Y Acad Sci 957:70–77

Hotokezaka H, Sakai E, Kanaoka K et al (2002) U0126 and PD98059, specific inhibitors of MEK, accelerate differentiation of RAW264.7 cells into osteoclast-like cells. J Biol Chem 277:47366–47372

Ikeda F, Nishimura R, Matsubara T et al (2004) Critical roles of c-Jun signaling in regulation of NFAT family and RANKL-regulated osteoclast differentiation. J Clin Invest 114:475–484

Kim JS, Jobin C (2005) The flavonoid luteolin prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced NF-κB signaling and gene expression by blocking IκB kinase activity in intestinal epithelial cells and bone-marrow derived dendritic cells. Immunology 115:375–387

Kim SH, Shin KJ, Kim D et al (2003) Luteolin inhibits the nuclear factor-κB transcriptional activity in Rat-1 fibroblasts. Biochem Pharmacol 66:955–963

Kim K, Kim JH, Lee J et al (2005) Nuclear factor of activated T cells c1 induces osteoclast-associated receptor gene expression during tumor necrosis factor-related activation-induced cytokine-mediated osteoclastogenesis. J Biol Chem 208:35209–35216

Koga T, Inuli M, Inoue K (2004) Costimulatory signals mediated by the ITAM motif cooperate with RANKL for bone homeostasis. Nature 428:758–763

Kotanidou A, Xagorari A, Bagli E (2002) Luteolin reduces lipopolysaccharide-induced lethal toxicity and expression of proinflammatory molecules in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165:818–823

Lakkakorpi PT, Väänänen HK (2004) Calcitonin, prostaglandin E2, and dibuturyl cyclic adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate disperse the specific microfilament structure in resorbing osteoclasts. J Histochem Cytochem 38:1487–1493

Lerner UH (2004) New molecules in the tumor necrosis factor ligand and receptor super families with importance for physiological and pathological bone resorption. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 15:64–81

Matsumoto M, Sudo T, Saito T, Osada H, Tsujimoto M (2000) Involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in osteoclastogenesis mediated by receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL). J Biol Chem 275:31155–31161

Matsumoto M, Kogawa M, Wada S (2004) Essential role of p38 mitogene-activated protein kinase in cathepsin K gene expression during osteoclastogenesis through association of NFATc1 and PU.1. J Biol Chem 279:45969–45979

Middleton E Jr, Kandaswami C, Theoharides TC (2000) The effects of plant flavonoids on mammalian cells: implications for inflammation, heart disease, and cancer. Pharmacol Rev 52:673–751

Mocasi A, Humphrey MB, van Ziffle JA et al (2004) The immunomodulatory adapter proteins DAP12 and Fc receptor gamma chain (FcRgamma) regulate development of functional osteoclasts through the Syk tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:6158–6163

Nakamura I, Takahashi N, Sasaki T et al (1991) Wortmannin, a specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase, blocks osteoclastic bone resorption. FEBS Lett 361:79–84

Rodan GA, Martin TJ (2000) Therapeutic approaches to bone diseases. Science 289:1508–1514

Ross JA, Kasum CM (2002) Dietary flavonoids, bioavailability, metabolic effects, and safety. Annu Rev Nutr 22:19–34

Sharma SM, Bronisz A, Hu R et al (2007) MITF and PU.1 recruit p38 MAPK and NFATc1 to target genes during osteoclast differentiation. J Biol Chem 282:15921–15929

Suda T, Takahashi N, Martin TJ (1991) Modulation of osteoclast differentiation. Endocr Rev 13:66–80

Suda T, Jimi E, Nakamura I et al (1997) Role of 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitaminD3 in osteoclast differentiation and function. Methods Enzymol 282:223–235

Suzuki H, Nakamura I, Takahashi N et al (1996) Calcitonin-induced changes in the cytoskeleton are mediated by a signal pathway associated with protein kinase A in osteoclasts. Endocrinology 137:4685–4690

Takayanagi H (2002) Induction and activation of the transcription factor NFATc1 (NFAT2) integrate RANKL signaling in terminal differentiation of osteoclasts. Dev Cell 3:889–901

Takayanagi H (2005) Mechanistic insight into osteoclast differentiation in osteoimmunology. J Mol Med 83:170–179

Takayanagi H (2007) Osteoimmunology: Shared mechanisms and crosstalk between the immune and bone systems. Nat Rev Immunol 7:292–304

Teitlebaum SL (2000) Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science 289:1504–1508

Teitelbaum SL (2004) RANKing c-jun in osteoclast development. J Clin Invest 114:463–465

Teitelbaum SL, Ross FP (2003) Genetic regulation of osteoclast development and function. Nat Rev Genet 4:638–649

Väänänen HK, Zhao H, Mulari M et al (2000) The cell biology of osteoclast function. J Cell Sci 113:377–381

Walsh MC, Kim N, Kadono Y et al (2006) Osteoimmunology: interplay between the immune system and bone metabolism. Annu Rev Immunol 24:33–63

Whitmarsh AJ, Davis RJ (1996) Transcription factor AP-1 regulation by mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway. J Mol Med 74:589–607

Wong BR, Josein R, Lee SY et al (1998) The TRAF family of sigal transducers mediates NF-κB activation by the TRANCE receptor. J Biol Chem 273:28355–28359

Xagorari A, Papapetropoulos A, Mauromatis A et al (2001) Luteolin inhibits an endotoxi-stimulated phosphorylation cascade and proinflammatory cytokine production in macrophage. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 296:181–187

Ziyan L, Yongmei Z, Nan Z et al (2007) Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory activity of luteolin in experimental animal models. Planta Med 73:221–226

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by an endowment from Erina Co. Inc. and partially funded by a grant for Biodefense Programs of the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology of the Republic of Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, JW., Ahn, JY., Hasegawa, Si. et al. Inhibitory effect of luteolin on osteoclast differentiation and function. Cytotechnology 61, 125–134 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10616-010-9253-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10616-010-9253-5