Abstract

The present paper deals with the territorial movements of the mafia groups. After postulating that the concept of mafia refers to a form of organized crime with certain specific characteristics of its own, the paper presents: i) a repertory of the mechanisms underlying the processes whereby mafias expand beyond their home territories, and ii) a taxonomy of the forms that the mafia assumes in nontraditional territories. In a case study approach, the conceptual framework thus outlined is applied to the mafia’s presence in Germany, as reconstructed from documentary and judicial sources. Though this is an exploratory investigation, certain findings are clear: i) the ‘Ndrangheta is more active in Germany than the other traditional Italian mafias (Cosa Nostra and Camorra), and ii), even in “successful” expansions, the mafia does not reproduce the embeddedness it typically shows in its home territories, but chiefly concentrates on infiltrating the economy and dealing on illegal markets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The spatial mobility of mafia-type criminal organizations has become a topic of growing interest, for scholars as well as for public opinion and law enforcement. For some time now, judicial investigations have indicated that the mafia is no longer confined to certain areas of Southern Italy.Footnote 1 In both the scientific literature and the public debate,Footnote 2 it is emphasized that the territorial expansion of mafia organizations in non-traditional areas now affects broad swaths of Northern Italy, e.g., Piemonte and Lombardia, as well as areas outside the country. It is precisely these transnational movements of mafias that have sparked interest in recent years. In truth, this is nothing new, as witnessed by the debate concerning the genesis of the so-called American Cosa Nostra, which is often spoken of in terms of Southern Italian immigrants who brought the mafia “virus” with them [7, 26, 31, 49, 51, 52, 55, 58]. But it is equally true that the transnational presence of mafia groups has recently attracted growing attention.

One of the major reasons for this attention concerns the growing internationalization of socioeconomic phenomena. With an economy that is increasingly centered on international flows, the idea that mafias become more “liquid”—to echo Bauman—or less rooted in specific territory, more inherently transnational, has gained favor with many scholars [e.g. 15, 23, 77, 91,100].

In their extreme versions, these views hold that globalization implicitly fosters crime and fuels a sort of moral panic about migrations, which are seen as vehicles for the “ethnic-based” variants of organized crime groups [90]. Though there are obviously other visions that are less apocalyptic, better thought-out, there is still a need for closer scrutiny, both theoretical and empirical, of the mafia movements outside of their territory of origin. In particular, the article aims to contribute to a better understanding of an issue that has not yet been brought into sharp focus: the form that the mafia’s presence takes in areas outside those in which it originated. In this connection, our hypothesis is that the mafia takes on diversified configurations in its new territories which must be delineated in detail. These different forms depend on how the process of expansion takes place, or in other words on the generative mechanisms involved. The expansion processes originate from the interplay of many concatenated mechanisms [74, 90]. Not all of these mechanisms are always active at the same time or in the same combinations: different mixes of mechanisms will generate different types of mafia expansion.

The article proceeds as follows. First, we will clarify the concept of mafia (“Mafia: a possible ideal-type”). In an effort to move away from the increasingly evocative use of the term, we will argue that the mafia is a particular form of organized crime that is capable of infiltrating the legal economy and politics, of gaining a certain social acceptance and some measure of tolerance on the part of the authorities [52]. Subsequently, we will present a framework of the processes of mafia expansion, attempting to outline: i) a repertory of the mechanisms on which the mafia’s expansion is based (“Processes of expansion”), and ii) a taxonomy of the different types of expansion (“Types of expansion”). In the light of these analytical frameworks, we will then present empirical evidences regarding the spread of the Italian mafia in GermanyFootnote 3 (“The mafia in Germany”). From the time a number of mafia killings hit the headlines some years ago (see infra), this is an issue that has been followed closely by law enforcement and the judiciary in both Italy and Germany, and has to some extent entered public debate. We close by summing up the main findings and with some policy suggestion (“Conclusions”).

Mafia: a possible ideal-type

Defining mafia is no easy task: the term has systematically attracted stereotypes that tend to portray it as an elusive phenomenon, typical of backward societies. Stereotyped portrayals of the mafia have influenced perceptions of it, and have contributed—in the strict sense—to shaping it. From these depictions and the rhetoric employed to describe the mafia, in fact, mafiosi have gained ideas and stimuli for how to represent themselves and interact [see especially 40, 54]. In turn, certain commonplaces about organized crime are fueled and conveyed by the mafiosi themselves, who use them to build their reputation. This is the case of the myth of an older “good” mafia, whose aim was to preserve traditional values, as opposed to a new “bad” mafia, interested only in the pursuit of gain [35].

The term mafia is one of the few Italian words to be known worldwide, a catch-all concept embracing a wide range of phenomena associated with deviance, criminality, and violence, and which are found in different parts of the world [69]. In the common lexicon, moreover, the term mafia is used to refer metaphorically to situations marked more by particularism and clientelism than on universal or meritocratic dynamics. By contrast, we will use the concept of mafia in a more circumscribed sense: as a form of organized crime, with unique attributes of its own [e.g. 1, 36, 73, 97].

In general, defining a phenomenon entails identifying certain salient features and establishing its boundaries. In this respect, our subject throws another difficulty in our path: tracing the confines of the mafia is by no means straightforward. Scholars have often regarded the mafia as coinciding with the context in which it originally took root, interpreting it as a phenomenon arising from cultural codes that are widespread in mainstream society. This perspective loses sight of the distinction between what lies outside and inside the mafia. This is the case of the cultural interpretations, which hold that the mafia is a mentality stemming from the subculture of a given local society, marked by codes of omertà and patronage [46].

It should also be borne in mind that discussions of the mafia take shape in opposition to—and are in turned fueled by—those regarding the anti-mafia. Investigations of organized crime also contribute to providing a representation of it [e.g. 48, 72]. In short, the judiciary at times fosters the idea of the mafia as a criminal super-structure, a sort of holding company of crime, and at other times puts greater emphasis on its internal structure, its organization and violent methods. The first representation spotlights what is presumed to be the growing financialization of criminal power and its presence in a global economy. The second, conversely, stresses the mafia’s activities in its local area (primarily extortion and infiltration in competitive bidding) and in illegal markets, and especially in drug trafficking.

In this paper, we will use the term mafia (in the singular) to designate the phenomena in its ideal-typical features, bearing in mind that, in concrete reality, it will differ in space and time. In Italy, then, we can distinguish between several historical mafias (in the plural): Cosa Nostra, ‘Ndrangheta and Camorra, originally embedded in specific areas of the South (and respectively in certain zones of Sicilia, Calabria and Campania).Footnote 4

Within these mafias, the configurations that take shape vary according to the structure of the organization, which may be centralized to a greater or lesser extent, and the management of their activities, which may be coordinated or conflictual in character [4, 5, 19, 53, 59, 73, 75]. Traditionally, Cosa Nostra tends to have a pyramidal organization, where relationships of vertical integration and a relatively unitary structure predominate. The Camorra clans, by contrast, are more fragmented in structure, with many of the typical features of gangsterism, especially in the Naples metropolitan area, but with solid ties to other areas of the region and in the province of Caserta in particular. Lastly, the ‘Ndrangheta has a horizontal organizational structure, leaving more independence for individual groups, though coordination has recently become more centralized. In recent years, judicial investigations conducted not only in Calabria, but also in several Northern Italian regions—and specifically in Lombardia, Piemonte and Liguria [82–84, 86]—have shown that the main ‘Ndrangheta clans are connected by a superordinate body whose functions are to settle internal conflicts and recognize membership on the part of individuals and groups ([14: 322, see also [87]). This body, known as the crimine or provincia, is presided over by a member elected by the clans’ representatives for a limited period of time.Footnote 5 The capo-crimine is not a “boss of bosses” (as has often been portrayed in the press), but has a chiefly symbolic and representative role.Footnote 6

In all of the mafia formations, in any case, there is a tension between organizational centralization and diffusion, which assumes a network configuration.Footnote 7

Despite the differences that can be seen between the various mafia groups, they all share (as Wittgenstein would say) a certain “family resemblance”. We can thus attempt to construct an ideal-type of mafia, synthesizing certain particularly salient aspects that are present to a greater or lesser extent in actual mafia groupsFootnote 8:

-

The individuals belonging to mafia-type criminal organizations make up a secret society, with specific bonds of loyalty and a well-defined hierarchy of control, and act in pursuit of gain, reputation and security;

-

The mafia’s power is largely based on exercising violence, whether actual or threatened, and on exploiting traditional cultural codes and manipulating social relationships in order to establish mutual exchanges in political and economic circles [73]. Thus what distinguishes mafiosi is their capacity of accumulating social capital [21];

-

The mafia’s organizational structure is that of a network organization, with a certain degree of internal cohesion and an appreciable level of openness to the outside. Specifically, mafiosi are bound to each other by strong ties, and with outside social groups by weak ties [43].Footnote 9 In addition, the organizational relationships between the network’s members may be closer in some cases, looser in others, thus enabling parts of the organization to have more independenceFootnote 10;

-

The mafia’s organizational form includes two dimensions that are combined with each other in a variety of ways [11: 1] that of an “organization for illicit trafficking”, which makes it an “enterprise” that operates between the legal and illegal markets; and 2) that of an “organization for control of the territory” of the local societies in which it is embedded.Footnote 11 This dimension is cultivated by using the resources of violence and social capital discussed above, whereby the mafia can exercise protection-extortion.

Unlike the “ordinary” forms of organized crime for which “making a profit, through whatever means are considered necessary, is […] the primary goal” [36: 66], the mafia is not oriented exclusively towards profit-making, but also seeks power. The mafia has “political subjectivity”, i.e., exhibits several features of the Weberian political group: a system of rules and norms, an apparatus that ensures they are respected, and the ability to use physical coercion and to exert forms of domination over a specific territory [68].

The mafia has provided a concrete demonstration—by virtue of these features—that it has effective means for embedding itself in its territory. Nevertheless, it has also proven that it is able to expand into nontraditional areas, both in its home country (e.g., into Northern Italy) and internationally.

Processes of expansion

Though it may seem anachronistic today, many scholars long held that the mafia is a phenomena that cannot be exported. In this interpretation, the mafia can be formed only under exceptional contextual conditions that can be found only in the areas where it was born and grew. This view reduces the mafia to an expression of a traditional society with specific cultural codes and a backward economy [52]. More recently, faced with a bulk of empirical evidence, the idea that the mafia cannot be exported is no longer tenable. Its place has been taken by more nuanced interpretations that hold that the mafia is difficult to export—since it is heavily dependent on the resources and the environment of the society where it originated—but, given certain background conditions,Footnote 12 it can partially reproduce itself in different territories [39, 41, 63, 64].

A second interpretation can be expressed metaphorically with the idea of contagion. Here, the mafia’s expansion is seen as the unexpected outcome of demographic phenomena such as migratory movements from areas where the mafia has traditionally been present. There is a deterministic version of this view, viz., the presence of immigrants from Southern Italy automatically results in the mafia’s spread. This interpretation has stubbornly persisted despite a series of empirical findings: it is not true that mafia groups have formed wherever Southern Italian immigrants are to be found (for example, it has not occurred in South America). Conversely, Italian mafia groups are reported in areas where there has been no immigration from Southern Italy, such as the Costa del Sol in Spain [23, 28]. In countries where criminal groups of Southern Italian origin are present, moreover, these groups did not become active at the time of the great migratory waves, but only in more recent years, as witnessed by mafia penetration in Northern Italy [73] or the case of Germany which will be discussed below. Consequently, mafia expansion cannot be said to take place at the demographic level, given that the great mass migrations did not result in the generalized transplantation of mafia-type organizations as such.

The most recent work has underscored the difficulty of identifying a single determining cause of mafia expansion [56, 74, 90, 91]. It is a complex phenomenon, that in concrete cases takes shape through several concatenated mechanisms. Here, the significant factors underlying mafia expansion have been effectively categorized in a ‘push/pull’ framework. This grouping into push factors and pull factors, however, is an analytical dichotomy that runs the risk of conveying a hydraulic and mechanical view of the phenomenon. We propose a multilevel, dynamic framework, holding that it is more appropriate to construct a repertory of expansion mechanismsFootnote 13 by distinguishing between context factors and agency factors.

Context factors

Context Factors involve the structure of the opportunities existing in the contexts threatened by the entry of mafia actors. Here, we are dealing with the economic, cultural-relational and political-institutional spheres. As regards the legal economy, certain sectors are more vulnerable to mafia infiltration, in particular: i) those of the traditional production system, with their low technological level and predominance of small-scale enterprises that compete on the local market, like construction [50, 53]; ii) the sectors subject to public regulation (e.g., competitive bidding), where the mafia puts pressure on policy-makers and gains advantageous positions in accessing public resources. These are the areas where the mafia’s presence—and in some cases the protection it offers—are strongest, and where mafiosi can make best use of their “skills”: their use of violence to discourage competition and employ labor flexibly, their store of social capital. Nevertheless, it must be recognized that the attractiveness of these traditional sectors is by no means the only road to mafia expansion. Cases have recently emerged where mafiosi operating outside their home territories have been charged with crimes such as fraudulent bankruptcy, tax evasion, environmental violations and setting up dummy companies, often through intermediaries such as accountants, tax advisors and legal consultants [42].

One of the factors that can encourage the mafias’ expansion is the economic dynamism of local settings. These criminal groups are attracted by high-growth areas where they can make new investments or assume their traditional role as protectors and go-betweens, seeking to lubricate social relations and economic transactions. At the same time, the mafiosi are also able to benefit from situations of economic crisis, for instance by offering liquid capital and financial resources to entrepreneurs who have difficulty in accessing credit, or by taking over troubled businesses as fronts for money laundering [83].

Other context factors that make a territory more susceptible to mafia entrenchment involve intertwined cultural, political and institutional aspects. Where political institutions are ineffective in regulating economic processes and cushioning the effects of market failures, there may be a loss of institutional trust. This process can provide more scope for “mediators” to provide protection and sanction collusive exchanges. In addition, ineffective institutions foster corrupt practices and the private appropriation of public resources, and result more generally in a widespread lowering of the sense of legality [27]. This outcome can also be affected by the actors’ social circles, where social norms “circulate”, establishing the degree of approval/disapproval accorded to conduct. In this specific case, having dealings with a mafioso entails a certain degree of social disapproval and hence moral costs: if these costs are low, there will be less resistance to establishing contact. To summarize, then, in addition to depending on idiosyncratic propensities, the decision to enter into a relationship with a mafioso will hinge on two mutually interconnected components: i) the type of recognition and legitimacy enjoyed in one’s social circles, and ii) the system of social norms and obligations circulating in the institutional environment.

Again with regard to institutional aspects, it should be added that inadequate opposition on the part of law enforcement and the judiciary—either through a lack of experience or because there is no appropriate legislation—makes the mafia’s expansion easier.Footnote 14 Other facilitating factors include scant attention from public opinion, the mass media and civil society in general, and a tendency on the part of local political figures to underestimate the problem.

The success of the mafia’s expansion can be favored by situations in which other forms of illegality are already common: for example, covert deals and corruption in politics and local government. In this case, the mafia’s ability to offer illegal services can link up with other skills in illegality that already exist in the territory [22].Footnote 15

Lastly, it should be borne in mind that exogenous shocks can dislodge the economic and political actors who operate in an area, generating new opportunities for criminal infiltration. This is the case, for example, of the collapse of the planned economy countries, where the rapid transition to a market economy, with no political and bureaucratic institutions that can set up a credible system of constraints and incentives and guarantee a respected rule system, generates a demand for protection that can be offered by mafia groups [90].

Agency factors

Context factors alone are not sufficient to illustrate the mechanisms underlying the processes of mafia expansion across territories. It is also necessary to consider the active role of the actors who concretely pursue these processes: their strategies for action, their ability to understand and take advantage of the opportunity structure, i.e., the agency factors [74]. From this standpoint, it is useful to make a distinction between intentional and unintentional choices [74, 90]. In the first instance, expansion is an independent decision, taken on the basis of an assessment of costs and benefits, and to a certain extent subject to instrumental and strategic considerations.Footnote 16 In the second instance, by contrast, expansion is a decision influenced by external variables, less sought out and planned, and made more in response to an adaptation mechanism. Basically, unintentional processes of expansion stem from the decision to look for a new territory as a result of three processes: 1) a crackdown by law enforcement; 2) a mafia war, which upsets the balance of power between rival clans in a given territory, reducing the opportunities and dealings available to the losing clan, which decides to turn its attentions elsewhere; 3) the perverse outcomes of efforts to quash organized crime, which force mafiosi out of their home territories (in Italy, this is the case of soggiorno obbligato or forced resettlementFootnote 17). In greater detail, we can say that these factors can explain mafia members’ exit from a territory in which they were entrenched, after which a true process of expansion can begin. In the case of soggiorno obbligato, for example, the mafiosi may find their new territory to be promising and thus decide to prolong their stay beyond the time mandated by the court [e.g. 22, 74, 90]. In the case of conflict between warring groups and/or an effective crackdown, the criterion used to select the destination is important, and is likely to be based on an estimate of the opportunities provided by different areas. In these cases, even if there is no explicit plan for colonizing new territories, the move is not made at random, but is founded—at least as regards the choice of place—in strategic considerations.

As for intentional movements, the basic mechanism involves finding a territory for doing business and increasing gains. The decision may often reflect the need to invest, in the legal or illegal economy, money made in the original territory. The latter, in fact, may not offer sufficient investment opportunities because of tight markets or in view of the higher risks associated with money laundering. Secondly, attempts to extend the range of action in illicit trafficking, and especially in drug dealing, are important. For a mafioso, the move to another area may be dictated by hopes of “getting ahead”, i.e., by the desire to improve his standing in the criminal organization: in a setting with less internal competition, the chances of rising in “rank” are better.Footnote 18

For both intentional and unintentional factors alike, the process of expansion may be mediated by relational resources. The prior presence of fellow countrymen, acquaintances, friends, relatives and other gang members in the new location can help the new arrival establish himself economically and socially, providing assistance and information about the area and acting as brokers. Having a dense network of contacts is an opportunity structure that can be leveraged by criminal groups pursuing a strategy of extending the territorial scope of their operations (Fig. 1).

Types of expansion

The concrete cases of mafia expansion are not distinguished only by their outcome, by whether the movement to a new area succeeds or fails, but also by the forms they take in a specific territory. Given this heterogeneity, it is important to build up a taxonomy of the different processes of expansion. As a preliminary step, we suggest two main forms that can be identified on the basis of the type of connection with the home territory:

-

1)

A spread of the mafia phenomenon in which connections are maintained with the original mafia groups and areas, i.e., the relationship is one of subordination to and dependence from the “mother house”;

-

2)

An emergence of the mafia phenomenon in an area that was formerly immune which takes place endogenously or is substantially independent of the original territories.

The first form of expansion has two variants. On the one hand, there may be a fully-fledged settlement, of the mafia in a formerly immune territory. This is the case of those situations where, starting from a given original setting, the mafia is able to reproduce itself elsewhere (viz., it is able to reproduce the characteristics outlined in paragraph 1), colonizing its new location and becoming fully embedded in it. On the other hand, we have the situations that reflect a more or less intense form of infiltration. In these cases, we will see only certain features of the mafia organizations in the new territories, reproduced by the presence of individual mafia members or groups, who operate in the new setting. At the lowest level of an infiltration, the mafiosi in the new territory will operate in purely predatory fashion, as do ordinary criminals, whereas settlement, which entails a greater degree of embeddedness, also involves forms of territorial control. Settlement is obviously harder to achieve: striking root necessarily calls for more time than simply infiltrating, and the combined action of a series of factors, both context and agency.Footnote 19

We can also distinguish between two ideal-typical cases for the second form of expansion process in which—as we have seen—mafia groups which are independent of the organizations in the home area establish themselves in previously uncontaminated territories. The first involves a process of formation in which the link with the original groups and setting is chiefly “symbolic”: here, a mafia is produced through imitation. This occurs when criminal groups and individuals pattern their conduct and organization after the traditional mafias, though without having structural ties with the original areas. Another situation is that in which locally-grown criminal groups adopt an organizational structure and symbolic apparatus (initiation rituals, for example), inspired by and imitated from traditional mafia models.

In the other ideal-typical case, the rise of a mafia is linked to the original home territory in “material” or “instrumental” terms (e.g., to do specific types of business), but only at the initial stages of the expansion process. In other words, there is a sort of “contamination” of the new territory by mafia groups, which leads, however, to a situation of hybridization, which results—over time—in the emergence of a full-scale new mafia, or a criminal group that maintains affinities with the original group but cannot be considered as a direct outgrowth, as it gradually distances itself by adopting an independent model of action and organization.Footnote 20 Though there may be connections and links between the “new” and original mafias, they take the form of predominately structural relationships (business deals and exchanges of services) between two independent entities, without giving rise to a single, unitary organizational configuration (Fig. 2).

Clearly, this analytical framework, which is dynamic and ideal-typical in nature, is chiefly valuable for exploratory purposes. In reality, concrete cases of mafia expansion show a mixture of the four types we have described, where it is likely that one predominates. It is also plausible that the mafia’s approach to taking over a given territory, combined with the latter’s characteristics, give rise to configurations that change over time.Footnote 21 The initial infiltration in the legal or illegal economy can later lead to a more stable territorial entrenchment on the part of the mafia organization, and thus appear to be a settlement. In the new territory, this means that the mafia will have a greater capacity for networking, i.e., to establish relationships of complicity and collusion with economic and political actors. This does not proceed, however, along a unilateral and evolutionary route: some processes of expansion reach maturity without ever going beyond infiltration, and there are cases where mafia expansion recedes after an initial success.

Lastly, it should be noted that the mechanisms underlying the processes of mafia expansion discussed in the preceding paragraph are not neutral with respect to the type of expansion. A mafia presence resulting from the infiltration model is more sensitive to contextual mechanisms regarding the economic sphere, while a situation that is more similar to a settlement usually requires a greater determination on the part of the mafiosi to seize control over the newly entered territory, which can be facilitated by cultural, political and institutional factors (lack of authority on the part of state institutions and of legitimation on the part of local authorities, slow response by civil society, weak legality, etc.).

The mafia in Germany

In the town of Duisburg on August 15, 2007, six young men belonging to a ‘Ndrangheta group were gunned down by hitmen from a rival group in front of an Italian restaurant where the victims had passed the evening. Though it took place in Germany, the massacre was the culmination of a feud originating in San Luca, a village in Calabria regarded as one of the most important centers of the ‘Ndrangheta, and the scene of bloody conflict between two mafia families.

The ferocity of the massacre, which was reported in the worldwide press, the fact that it propelled a conflict rooted in a small Southern Italian village into another country, and the risk that the mafia and its violence could insinuate itself into the European Union’s richest nation all pointed to the need for a clearer picture of the Italian mafias’ presence in Germany, not least because of the intense economic exchanges and history of immigration that link the two countries.Footnote 22

The mafia’s main activities in Germany are illicit trafficking, in particular drug dealing, counterfeiting, automobile smuggling and money laundering, with investments in various areas of the economy, including real estate, tourism, construction, textile industry, retail businesses and restaurants. The commercial enterprises also provide a logistics network for transporting drugs and for the arms traffic [2, 10, 15, 38]. However, there is no lack of evidence that these mafia groups are even capable of infiltrating other spheres of the upperworld: for example, certain mafia cells have bought large blocks of stock in energy companies, including Gasprom, on the Frankfurt exchange [23].

From the territorial standpoint, we can say that the mafia is scattered in clusters across Germany. Hotbeds can be found in the industrial basin of North Rhine-Westphalia, long settled by the Italian mafia: members of Cosa Nostra are active in Cologne and Wuppertal, and there are Camorra clans in Dortmund and Düsseldorf [38, 65]. An operation by the Italian judiciary, moreover, found offshoots of the ‘Ndrangheta in numerous towns in Baden-Württemberg and Hesse: specifically in Stuttgart, Mannheim—where groups from Africo, Bova Marina and Marina di Gioiosa Ionica are active—and Frankfurt, where clans originating from the Catanzaro area operate [25, 30, 84]. Nor should we forget that starting chiefly in the ‘90s—from the time when the Italian mafia’s presence had become clear—it appears to have established a firm foothold in several cities of the former German Democratic Republic: Berlin, Chemnitz, Dresden, Leipzig, Magdeburg and Erfurt [30, 32: 142]. In general, however, the presence that can be regarded as most significant is that of the ‘Ndrangheta from the areas of Locri and San Luca, which established itself mostly around Duisburg and spread thence to other parts of the country. We will return to this group in the following pages.

Empirical evidence thus does not bear out the naive interpretations of the contagion metaphor: there are relatively few Italian immigrants in the eastern portion of the Federal Republic of Germany.Footnote 23 Even in the Länder with highest Italian population, organized crime began to make itself felt when mass immigration from Italy had already come to an end. The available data suggest that organized crime infiltrated later, attracted by the local economy’s growing potential.Footnote 24 This means that the prior presence of Italian immigrants became important only in relation to mafia clans’ expansion strategies.

The infiltration of Italian mafias in the east also indicates how important the opportunity structure can be. A few of the elements of this structure that proved favorable to infiltration include the fall of the Berlin Wall, the transition to the market economy on the part of the former DDR Länder, the reduction in border controls on trade mandated by the Schengen Agreements, Germany’s special geopolitical position as a bridge to Eastern European countries, where markets are also expanding, and the vicinity of the Netherlands, a major port of transshipment for the drug traffic with South America. These factors have made the country, and the easternmost parts in particular, attractive to mafia organizations [44].

Another interesting point concerns the pronounced tendency to maintain contacts with the place of origin: when necessary, the businesses run by mafiosi in Germany have harbored mafia members who have fled from the law, or are looking for work and a place to stay while doing so.Footnote 25 These aspects testify to organized crime’s ability to put social networks of their immigrant compatriots to effective use. Noteworthy in this connection is a recent and particularly alarming incident involving the former senator Nicola Di Girolamo. Elected as the representative of Italians abroad for the European electoral district, Di Girolamo was involved in the early months of 2010 in an extensive investigation, as a result of which he was forced to resign and was subsequently found guilty. According to the prosecutors, he owed his election to vote-rigging by the ‘Ndrangheta. The mafiosi to whom the senator was allegedly close had involved the groups in Germany, asking them to support the campaign. The affair signals the networking abilities of mafia groups, who have shown that they can contribute significantly to delivering elections through vote-buying and patronage [76].

Another form of link with the home area is symbolic in character: take, for example, the initiation rite. In this connection, it should be recalled that after the Duisburg massacre, it was found that “the wallet of one of the victims, Tommaso Venturi, contained a charred picture card of St. Michael, clearly indicating that an initiation had been held shortly before”. It is no accident that the killings, like other similar episodes in Calabria, took place “always in a symbolic and ritual perspective, in a day of celebration” [23: 13]. Further signs of these symbolic links emerge from an investigation conducted by the Reggio Calabria judiciary, which used electronic surveillance to reconstruct the process of setting up an ‘Ndrangheta unit (a so-called locale) in the city of Singen, which faithfully retraces the rituals of forming a locale in Calabria: sacralizing, through a sort of baptism, the place where the members meet and making the ties between them official [84]. For the purposes of our analysis, this investigation touches on several other interesting points, which help delimit the Calabrian mafia’s international movement. It would seem from the investigation that the formation of ‘Ndrangheta units in Germania requires recognition by the mother house, from which the affiliates abroad continue to “depend”, and to which they are answerable as regards the activities they intend to pursue, their organization,Footnote 26 members’ “promotions” and the disputes between different groups [37]. This concept is clearly expressed by a high ranking member of the ‘Ndrangheta Locale in Singen, Bruno Nesci, who was recorded in a wiretap as saying: “when I go down there [to Calabria], I talk about what I have to talk about, and when I come here [to Germany], I say what they say to me down there” [84: 1842]. Nesci traveled to Calabria to receive instructions on how to resolve conflicts between the different groups in Germany [84]. These findings appear to confirm a (partial, at least) “unity of the ‘Ndrangheta in its transnational arrangements” [84: 1910]. More specifically, the affiliates in Germany are accorded a certain independence in their economic dealings (illegal activities and investments in formally legal activities), but are answerable to the ‘Ndrangheta organization in Calabria—as the police wiretaps of mafiosi indicate [84: 1812]—as regards the “recognition” of the units operating in Germany and the criminal careers of their members (for example, ranks and roles must be assigned with the consent of the Calabrian groups).Footnote 27 And it is in Calabria that attempts are made to resolve the tensions and conflicts that can arise between different groups laying claim to the same area in Germany.Footnote 28 Controversies of this kind are thus discussed in Calabria, where each group’s territorial sway, sphere of action and chain of command are established. As an affiliate of the Singen Locale remarked: “Without orders from down there, nobody can do anything” [84: 1862]. In these “power games”, what counts are not only the relationships of force that have been established in the new locations, but also the ties with the groups in Calabria. Being linked with a powerful cosca in Calabria also confers greater power in the newly occupied area.

Another emblematic case is that of the ‘Ndrangheta locale of Cirò, a small town in the province of Crotone. Following an internal conflict in the 1970s, control over this clan was wrested by a group of mafiosi headed by Giuseppe Farao. Intent on expanding, Farao was able to set up an organization with branches in Lombardia and Germany [81]. The role of regent for the unit in Germany was assumed by Cataldo Grisafi and Mario Lavorato, who centered the cosca’s operations around Kassel and Stuttgart, in Baden-Würtenberg. The case is a further demonstration of the complexity of relationships between the home territories and the newly penetrated areas: the mafiosi in Germany, in fact, receive money from Calabria that they often invest in the management of restaurants [81, vol. 4: 42]. At the same time, they send part of their profits back to Calabria, in what could almost be thought of as a system of “rotating payments”. In addition, they share a portion of their takings with the organization, which—if necessary—can resort to intimidation in support of relatives and friends jailed by the German police. Equally important is the clan’s bridging function in the drug traffic: it can procure drugs on the Dutch market and then distribute them in Germany and, at times, in Italy as well. As is often true with the ‘Ndrangheta, not all of the mafiosi’s activities are on behalf of the clan: the more enterprising individuals build up a reservoir of resources as part of their own personal endowment. This is the case of Lavorato, who in a few short months was able to open five pizzerias in Stuttgart, and also showed his remarkable stock of social capital through ties with a number of prominent local CDU members [81: 21–22].

The Italian mafia has also shown an ability to establish connections with organized crime groups originating in other countries: evidence has been found of dealings between ‘Ndrangheta members and the Russian mafia around Thüringen and in Leipzig [62, 92]. In Hamburg, it would appear that Italians and Albanians have forged strong ties in the prostitution market. Here, there is a difference in the spectrum of the mafia’s activities in the home areas and those into which it has expanded: in the former, mafia groups are not traditionally involved in prostitution.

However, the greatest difference between the mafia’s workings in Germany and in its home areas lies in the lower level of outside networking: as the BKA notes, no cases have been reported in which extended segments of political administrations at the local level have been suspected of a real form of collusion with mafia groups [8, 10]. In short, the Italian mafia in Germany does not operate as a secret society and an organization with political subjectivity. The mafiosi in Germany operate in the formal or informal economy; they do not exercise forms of “territorial signoria”Footnote 29 or control like that practiced at home, and they are less oriented towards building social capital resources in German society. This does not mean that certain portions of the territory may not be infiltrated by criminal groups with more social capital resources, a more stable organizational structure, greater internal solidarity and more power to intimidate outsiders: this could be the case of Duisburg [38]. A BKA report, made available to the Italian investigative authorities (BKA, The ‘Ndrangheta in Germany. Analysis of the activities in Germany of the clans originating in San Luca, SO 51–3, April 2008), indicated that around 200 Italian citizens in Germany are linked, directly or indirectly, to mafia families originating from the area of Calabria between San Luca and Locri. The report confirms that the city with the highest concentration of presumed members of these criminal groups is Duisburg, but that there is also a significant presence in Bochum, Essen, Erfurt, Neukirchen-Vluyn, Munich, Germering, Leipzig, Dresden, Eisenach, Weimar and Völklingen/Bous.Footnote 30

Most of the investigated individuals are involved in drug trafficking, as well as in money laundering and in formally legal investments, especially in the restaurant business and real estate.Footnote 31 In many cases, it was found that the money needed to open pizzerias or buy properties came from Calabria. The investments are made through trusted intermediaries who are asked to handle the purchase negotiations: “To acquire real estate, companies are sometimes set up and the stakes held in them are established. The titular owners are usually nothing more than front men in the lower ranks of the organization’s hierarchy, and are almost invariably relatives of the main organizers. The latter are careful to stay behind the scenes. The money invested is of dubious provenance, and is clearly at odds with the buying power of the people who are the restaurant’s ostensible owners” [9: 78].

At times, these are businesses that attract a high status clientele (“patronized by people in the public eye or politicians”, as the investigators note [9: 97]), and there is no lack of cases in which the alleged mafiosi built up a respectable reputation. In the Erfurt area, for example, one of these individuals strives to appear in public as a “benefactor”, and also sponsors a soccer team and the golf club: the investigators describe him as “an influential figure, not just in typically Italian settings” [9: 97]. German law enforcement has also focused attention on other individuals who have become successful businessmen in a short period. One such case is that of a well-known entrepreneur in the textile and clothing businesses, who is said to have invested large sums in Dresden that are difficult to explain. The investigators add that this businessman “has excellent contacts in economic and political circles, to the extent that it is questionable whether further checks in Germany would be possible” [9: 110].

To summarize, we can organize our analysis around three dimensions: the first is spatial in nature, the second temporal, and the third concerns the different mafia groups. From the spatial standpoint, it can be maintained that the spread of the Italian mafia in German follows a pattern that chiefly involves capturing territorial niches. This is quite clear in the eastern part of the Federal Republic. It would appear that these areas, after the events that followed reunification, were the target of an expansion that resulted from a deliberate strategy fielded by the mafia, who sought fresh profit opportunities by entering the “newborn” Eastern markets. For the moment, this is limited to an extension of illegal trafficking and the infiltration of specific spheres of the formal economy.Footnote 32 It remains to be seen whether this will be followed by an attempt to colonize, partially or otherwise, certain areas. The Eastern European countries’ sudden transition to the market economy was often not accompanied by an ability to “clearly define and protect property rights”, a situation that generated a demand for “alternative forms of protection” [90: 227], offered by violent mafia-type groups. As regards these phenomena, the move away from the planned economy in the eastern Länder was in some ways exceptional, as it was “guided” by West Germany. Its outcome was thus less traumatic in terms of the respect of property rights. The empirical data, in fact, provide no evidence for an expansion process that can be regarded as a settlement. It is more realistic to see the mafia presence as reflecting the infiltration model: the rapid—and perhaps poorly coordinated, as well as imperfect—market transition generated investment opportunities that the mafiosi did not fail to seize.

By contrast, in the western areas with a longstanding Italian immigrant presence, the mafia diffusion may at times have occurred as a partially unintended consequence. As they were able to rely on relatives or friends who had emigrated before them, it is possible that members of mafia clans arrived from Italy and, finding a favorable opportunity structure, decided to enter the types of illicit traffic that existed in the area before their arrival, or to start new ones by taking advantage of their skills, reputation and social capital resources.

In the final analysis, we can confirm that the mafia’s spread into non-traditional areas is not the result of a one-shot process, but is dynamic and complex. Over time, it is thus possible that the regionalized features of the Italian mafia’s entrenchment in Germany will be accentuated, giving rise to different local profiles, some more involved in organizing illicit traffic, others—we can assume—in controlling the territory. At the moment, in any case, empirical evidence and judicial findings confirm that the presence of mafia outposts in Germany meets the need to invest and gain entry to certain illegal sectors, rather than to find new markets for exercising protection-extortion.

The temporal dimension is obviously interwoven with the spatial. It can be maintained that the Italian mafias’ eastward expansion is more recent than that in the western parts of the country. Once again, however, it should be pointed out that even in the west, the mafia’s spread did not take place at the same time as the migratory flows, but only—as we have attempted to show—at a later stage.

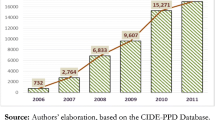

As Italy’s antimafia investigation bureau recently reiterated [28], the mafia’s transnational expansion in Germany involved all of the groups historically present in Italy: Cosa Nostra, Camorra and ‘Ndrangheta. Undeniably, however, the latter group has recently shown itself more adept at moving into international trafficking—as the case of the Federal Republic witnesses—than the other two: a recent report by the Berlin police (LKA-Berlin) maintains that 56.5 % of the Italian organized crime groups under investigation are part of the ‘Ndrangheta, followed by the Camorra with 24.5 %, Cosa Nostra with 13.5 % and the formations originating in Puglia with 5.5 % [37, 66]. Thus, what is regarded as the most archaic of the mafias has been the most successful at rising to the challenges of globalization, joining strong local roots with national and supranational expansion.Footnote 33 In particular, the ‘Ndrangheta has deployed a process of expansion on two levels, that of the individual mafiosi who move to another area, and the organizational level, given its ability to reproduce the Locali structure in new territories. One question, however, remains open: whether there is another, interorganizational level, or in other words a superordinate body that manages the relationships between Locali. Sufficient evidence to postulate that such a body also exists in Germany is not yet available.

Conclusions

The paper presented a framework for analyzing the combination of mechanisms underlying the processes whereby mafia groups expand. Through a taxonomy, we then outlined the configurations assumed by the mafia’s presence in areas outside those in which it originated. The paper helps clarify the process-driven nature of expansion processes: they are complex phenomena that change with time in a given territory.

The case of the mafia in Germany, reconstructed from documentary and judicial sources, was analyzed through this analytical approach. Our main findings show how difficult it is for mafia groups to create a settlement in a new territory. Instead of reproducing themselves fully on foreign territory, mafia groups engage in a process of infiltration, using cells of the organization operating in Germany to pursue a series of activities, both legal and illegal, that are chiefly economic in nature. Essentially, we see: i) a difference in the mafia presence in the home country and the new territory, and ii) a connection between the mafia groups in Germany and the mother house in Southern Italy. Here, it is important to emphasize that, at least for now, the process of reproducing mafia groups starts from the home territory: no affiliates have been identified who did not have Italian nationality and who did not come from the area in which their mafia group is historically entrenched. For example, the findings that emerged from investigations of the German offshoots of the ‘Ndrangheta all involve people from restricted areas of Calabria, i.e., the areas surrounding Crotone and Reggio Calabria. These considerations underscore the need for further empirical work on case studies that can be investigated through diachronic or longitudinal comparisons carried out in a limited territorial context affected by a mafia movement and observed over different intervals of time. Through such an analytical approach that we will be able to understand whether the mafia groups will acquire greater independence from the mother house and take on a more local character (like the hybridization model), as has occurred elsewhere. Likewise, it will be necessary to see whether a non-negligible mafia presence will spur processes of imitation by other organized crime groups—either local or made up of immigrants from countries other than Italy—which have still not appeared in Germany.

The empirical findings, moreover, suggest that the idea of transnational organized crime—as briefly discussed in the introduction—is not entirely convincing. It is an umbrella concept which is too generic to account for a many-faceted phenomenon [16]. Rather, the complex blend of embeddedness and expansion that marks mafia groups calls for the development of taxonomies such as that presented here, which can be tested empirically and progressively revised through appropriate case studies. Some empirical evidence suggests that mafia groups who expand into new territories can enter into cooperation with other forms of organized crime that are already present in the area. These synergies, however, are circumscribed from a functional, spatial and temporal standpoint. The phenomenon cannot be likened to the idea of systematic and organic transnational alliances between criminal organizations generated by the processes of globalization [see especially 18].

In addition, our analysis makes it possible to advance several theses that contradict certain positions that have been taken in the German public debate regarding the presence of the Italian mafia. The German institutions have long underestimated the scope of the problem, essentially denying that the offshoots of the Italian mafia in Germany could last [65]. This kind of reductive stance has also been reflected in the public debate. It springs both from the lack of a specific competence in combating the mafia, and from the idea that the mafia is only a remnant of the past, and is thus incapable of insinuating itself, if not transiently and superficially, in an advanced economy such as Germany’s. The climate has changed significantly after the Duisburg killings, shaped in part by a media frenzy that fueled a certain collective hysteria by conveying an overblown idea of the mafia presence and a series of ethnic stereotypes [3, 61, 80, 93]. In other words, the silence of the first stage was followed by empirically imprecise views that linked the presence of Italian mafia with the lack of integration and the strong sense of family that characterizes Italian immigrants.Footnote 34 Some of the data concerning Italians in Germany undoubtedly suggest a lack of integration: low levels of education, persistent difficulties in learning the language, high rates of unemployment [45]. However, thinking that this depends exclusively on Italian immigrants’ particularist orientation means assuming a essentialist and reified conception of culture. Such an attempt at explanation is even more unsatisfactory when it claims to interpret the mafia presence on the basis of poor integration: this, in fact, would amount to equating the mafia with the culture from which it springs, which would in turn produce difficulties in assimilating into the host society. Brought to extremes, this is tantamount to saying that Southern Italian immigrants are carriers of a latent tendency to mafia-type crime which manifests itself if integration is unsuccessful. It is clear that this proposition, markedly fallacious from the empirical standpoint, is supported by a stereotyped portrayal of the mafia, whose critical aspects were discussed in the opening paragraphs of this article.

A number of policy suggestions can be drawn from these considerations. The spread of the mafia does not reflect migratory processes, as is sometimes maintained in the political arena. Positions of this kind, which betray a sort of overarching obsession that sees the mafia striking root everywhere,Footnote 35 stand in the way of formulating effective crime-fighting measures. The fact that strong ties persist between the mafia in its traditional territories and its offspring in new areas calls for internationally coordinated action: it is encouraging that an Italo-German task force was set up between the DIA and the BKA after the Duisburg massacre. Legislative action on Germany’s part is also to be hoped for: ever more frequently, the judiciary points to the need to introduce the specific offense of criminal association in German law, and to develop the concept of mafia-type criminal association [10, 23, 28, 30]. In addition, it might also be useful to introduce measures for preventing the flow of mafia capital into the legal economy, such as the regulations requiring traceability of funds. As for the presence of businesses in collusion with the mafia, or actually run by the mafia, in the legal economy, strong anti-trust authorities could be beneficial in overseeing how contracts are awarded and the forms of competition. Such authorities could establish uniform criteria for drawing up white lists, i.e., lists of firms that meet specific requirements and can thus receive positive incentives and be granted preferential access to public contracts.

Notes

The Mafia is traditionally present in several areas of Southern Italy, where it is concentrated in the west of Sicily, with an epicenter in the cities of Palermo and Trapani; in the southern part of Calabria, the province of Reggio Calabria in particular, and in the provinces of Caserta, Napoli and Salerno in the Campania region [19, 29, 52].

See the work of the Antimafia Parliamentary Commission (Commissione Parlamentare Antimafia, CPA), the Antimafia Investigation Bureau (Dipartimento Investigativo Antimafia, DIA) and several recent judicial investigations, e.g., those regarding the mafia’s presence in the regions of Piemonte and Lombardia [84, 86]. In addition, starting with Saviano’s best-selling book [70], there has been a flurry of publications—mostly journalistic in nature—that have been enormously successful in attracting the public’s attention. As for scholarly publications, it should be recalled that the expansion of organized crime was addressed in a special issue of the journal Global Crime (3, 2011), with noteworthy discussions of the national and international spread of the Italian mafias [15, 91].

The analysis is based on judiciary material and institutional documents from a variety of sources, including the Antimafia Investigation Bureau (Dipartimento Investigativo Antimafia), the Antimafia Parliamentary Commission (Commissione Parlamentare Antimafia), the Antimafia National Judiciary Department (Direzione Nazionale Antimafia) and the Criminal Office of the German Republic (Bundes Kriminal Amt). This is material of a particular kind, as it is produced for judiciary, rather than scientific, purposes. However, information from such sources—handed with due analytical and methodological precautions—is the main dataset for the empirical studies of mafia-type organized crime in the leading international literature [see especially 89].

An Other criminal group is active in Italy which shares certain mafia feature: the Sacra Corona Unita (SCU), a criminal organization active in Puglia, an area which has historically been immune from the mafia presence. The SCU arose in this area between the late 1970s and early ‘80s, mainly as a result of the expansion of traditional mafia clans belonging to the Camorra and to the ‘Ndrangheta who were intent on controlling illegal trafficking, e.g., cigarette smuggling [74].

According to the investigators, similar structures also exist in Australia and Canada. Their function is both to provide internal coordination and to act as an interface with the “mother house” [33: 94].

It is a role of primus inter pares [33: 94]. Recent judicial investigations found that it had been assigned to the 80-year old Domenico Oppedisano, who despite his many years of belonging to the ‘Ndrangheta would not appear to have had a particularly distinguished criminal career [85]. The cosche seem not to give this position to a strongman, but to someone who is regarded as wise, capable of upholding tradition and mediating between criminal groups and thus of preventing conflicts [60: 6–7].

The mafia has resources of both bonding social capital, which connects the members of an organization to each other, and bridging social capital, as it is also able to establish outside ties [78]. Much of the mafiosi’s power stems from their ability to occupy structural holes [13] that separate different social networks.

The mafia is an example of a loosely coupled organization [99]. For example, Cosa Nostra’s so-called “Cupola”, or ruling commission, was active only in the Seventies and Eighties. Both before and afterwards, there was less coordination between the clans of the Sicilian mafia and more independent action [52, 53].

The mafia’s embeddedness in a given local society is not just relational. It also involves invoking traditional symbols, values and cultural codes [see 102].

Significant background conditions include, for example, uncertainty and lack of systemic trust [39].

In this section of the paper, we attempt to enumerate the large number of mechanisms that can foster mafia expansion processes. However, which of them are at work—and how—in concrete cases of expansion is mainly an empirical question.

This took place in Italy’s Liguria region, where the judiciary long underestimated the presence of mafia organizations, regarding them as fairly unstructured criminal groups, and thus did not apply the measures contemplated by antimafia legislation [24].

Several judicial investigations have revealed, for example, that corrupt practices in healthcare have made it easier for members of mafia groups to gain entry. These mafiosi take part in covert dealings, acting as “enforcers” for illegal deals thanks to their ability to hold the parties to the terms [23, 28, 84].

This interpretation does not mean that the mafia has a central expansion strategy. The idea that the mafia is a sort of holding company that can formulate a strategic overall plan for penetrating the most disparate national and supranational territories is unfounded [53].

Soggiorno obbligato or forced resettlement is a policy of court-ordered obligatory relocation in a specific place, usually far from the original residence, for a period of time, which may be quite long. The purpose of the policy is to oblige mafia bosses to move away from the territories in which they are entrenched. It is based on the assumption that the mafioso can be neutralized if his ties with the original setting are severed, thus underestimating mafia members’ ability to adapt to new environments.

This emerges from the testimony of a number of mafia members turned state witness, whose criminal career took off when they moved to nontraditional areas, especially when they showed particular skills in illicit trafficking [73]. In addition, reputations can be amplified in new mafia settings, so that saying that someone is a boss may be a self-fulfilling prophecy, turning him into a boss even if he was not one before [73: 166].

Cases of settlement can be seen, for example, in Southern Italy. As was pointed out earlier, the mafias occupy certain areas of the South, without pervading the entire region. In this part of the country there are historically uncontaminated areas that have more recently been involved in processes of expansion from neighboring territories, and where the settlement model has come into play. Examples include the ‘Ndrangheta’s move into the province of Cosenza in northern Calabria, where mafia were formerly unknown. Signs of settlement processes can also be recognized in circumscribed areas of Northern Italy, such as Piemonte and Lombardia [42, 74, 91].

This is the model followed by the American mafia. It would be misleading to think that the Sicilian model was transplanted into the United States, as if the American group were an outgrowth of the Italian. Indeed, the relationships between the mafias in the old and new continents are bidirectional. Action strategies and criminal organizational models are developed in the two settings through interaction and influence, by means of processes of hybridization [51].

An interesting case is that of the SCU in Puglia (see note 4), where the initial infiltration and transplantation of Camorra and ‘Ndrangheta groups was followed by a process of imitation by local criminals. They adopted methods and types of organization taken from the traditional mafias, thus resulting in the formation of a new mafia.

During the Fordist emigrations in the’60s and’70s, Germany hosted over a million Italian immigrants, most of whom were from the Southern regions [79].

There are around 623,000 Italians currently living in Germany. Of these, slightly over 3 % reside in the eastern Länder. The majority of Italian residents are concentrated in the southwestern part of the country and in the Rhineland, the heart of industrial Germany. Approximately 97 % of the Italians who have immigrated to Germany live in and around Stuttgart in Baden-Württemberg, in the Munich region in Bavaria, in North Rhine-Westphalia and in Hesse [45].

References to fugitive mafiosi who were tracked down and arrested in Germany can be found in [23].

The reproduction of the Calabrian mafia’s organizational structure in Germany is particularly significant, as it has assumed a configuration—as regards hierarchies, ranks and roles—that goes well beyond family ties [84].

It is interesting to note that both the rituals and the ranks and appointments in the Locali operating in Germany are similar to those found in the original Calabrian Locali.

An example of these tensions is furnished by the Singen Locale, whose territorial dominance was challenged by another Locale from a town a short way across the border in Switzerland [84: 1908 ff.]. As a member of the German Locale was recorded as saying of the rival group’s head in a wire-tap, “He thinks he can call the shots here in Singen, but he can forget it, I told him, he can have control in Switzerland if he wants” [84: 1848].

This concept, which has been applied to the mafia most notably by Santino [67], refers to the control over the territory that criminal groups exercise in the areas where they are entrenched. It chiefly takes the form of providing protection in various types of economic transaction, extending lucrative criminal activities to a number of settings, establishing a dense network of relationships in different institutional areas, and exerting power over the local community as a whole, thus influencing the operation of political and administrative institutions and the distribution of resources.

The German investigators note that a large number of young men from the small Calabrian town of San Luca have moved to these German cities in recent years: “Checks on certain of these individuals in Italy indicated that although these are men with no criminal record, their fathers or brothers often have prior indictments for serious offenses—participation in a mafia-type criminal association, murder, kidnapping and violation of arms and drug laws” [9: 166].

Over 60 restaurants and pizzerias have raised the investigators’ suspicions [9: 162–164].

As we have indicated, the sectors of the economy with strong local ties and a low technological level are more susceptible to penetration by organized crime [50]. It is thus possible that the massive real estate investments made in the eastern Länder after reunification made these areas more vulnerable to mafia entrenchment.

It should be emphasized that regarding the ‘Ndrangheta as archaic is to some extent the result of perspective bias. The German case is not the only, or even the first, instance of the ‘Ndrangheta’s international mobility. Suffice it to say that Calabrian organizations have long been entrenched in Canada and Australia, where the so-called “Siderno Group” specializes in the drug traffic. Originally from Siderno, a small town in the province of Reggio Calabria, the group’s members maintain contacts with the mother house and are related by blood or marriage. In Australia, the ‘Ndrangheta has reached dangerous heights, and has come into open conflict with the country’s institutions, as witnessed by the murders of a member of Parliament in 1977 and of the assistant commissioner of the Australian Federal Police in 1989 [20, 84: 1916].

In addition to appearing in sensationalist tabloids such as Bild Zeitung, articles expressing alarmist positions linking the spread of the mafia to the presence of Italian immigrants were also published in more analytical weeklies such as Der Spiegel [12]. For a reconstruction of the German debate on organized crime, see also [94, 96].

Italian organized crime groups in Germany are less numerous than those from other countries such as Turkey, Poland, Russia, Nigeria and Romania. Despite this limited quantitative spread, however, the Italian mafia scores high on the organized crime potential scale [8: 20–21].

References

Alach, Z. J. (2011). An incipient taxonomy of organised crime. Trends in Organized Crime, 56, 56–72.

Allum, F., & Sands, J. (2004). Explaining organized crime in Europe: are economists always right? Crime, Law & Social Change, 41, 133–160.

Allum, F., & Young, A. B. K. (2012). A comparative Study of British and German Press articles on ‘organised crime’ (1999–2009). Crime, Law & Social Change, 58, 139–157.

Arlacchi, P. (1993). Men of dishonor: Inside the Sicilian mafia: An account of Antonino Calderone. New York: Morrow.

Arlacchi, P. (2009). Mafia, peasants and great estates. Society in traditional Calabria. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barbagli, M. (2008). Immigrazione e sicurezza in Italia [Migration and Security in Italy]. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Bell, D. (1964). The end of ideologies. Glencoe: Free Press.

BKA (2007). Organisierte Kriminalität. Bundeslagebild 2007 [Organized Crime. German Overview]. http://www.bka.de/nn_193360/DE/Publikationen/JahresberichteUndLagebilder/OrganisierteKriminalitaet/organisierteKriminalitaet__node.html?__nnn=true. Accessed June 2008.

BKA (2008). La ‘Ndrangheta in Germania. Analisi sulle attività in Germania dei clan originari di San Luca [‘Ndrangheta in Germany. Analysis of the Activities of San luca Clans], SO 51–3, April 2008, Berlin.

BKA (2011). Organisierte Kriminalität. Bundeslagebild 2011 [Organized Crime. German Overview]. http://www.bka.de/nn_193360/DE/Publikationen/JahresberichteUndLagebilder/OrganisierteKriminalitaet/organisierteKriminalitaet__node.html?__nnn=true. Accessed May 2012.

Block, A. (1980). East Side West Side. Organizing crime in New York 1930–1950. Cardiff: University College Cardiff.

Brandt, A., Kaiser, S., Kleinhubbert, G., Ulrich, A., & Weinzierl, A. (2007). Weise Weste fur die Parallelwelt [No Guilt for the parallel World]. Der Spiegel, 50.

Burt, R. (1992). Structural holes. The social structure of competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Calderoni, F. (2012). The structure of drug trafficking mafias: the ‘Ndrangheta and cocaine. Crime, Law and Social change, 58, 321–349.

Campana, P. (2011). Assessing the movement of criminal groups: some analytical remarks. Global Crime, 12, 207–217.

Campana, P. (2011). Eavesdropping on the mob: the functional diversification of mafia activities across territories. European Journal of Criminology, 8, 213–228.

Campana, P., & Varese, F. (2011). Listening to the wire: criteria and techniques for the quantitative analysis of phone intercepts. Trends in Organized Crime, 15, 13–30.

Castels, M. (2000). End of millenium. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Catanzaro, R. (1992). Men of respect: A social history of the Sicilian mafia. New York: The Free Press.

Ciconte, E. (1996). Processo alla ‘Ndrangheta [A Process to ‘Ndrangheta]. Roma-Bari: Laterza.

Coleman, J. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

CPA (1994). Insediamenti e infiltrazioni di soggetti ed organizzazioni di stampo mafioso in aree non tradizionali [Mafia presence in non traditional areas]. Roma: XI Legislatura.

CPA (2008). Relazione annuale sulla ‘Ndrangheta [Annual report on the ‘Ndrangheta]. XV Legislatura, Doc. XXIII, 5.

CPA (2010). Relazione annuale [Annual report]. XV Legislatura.

CPA (2012). Audizione Sostituto Procuratore Nazionale Antimafia, Procuratore Carlo Caponcello [Audition of Carlo Capponcello, Antimafia National Judiciary Department], 31 Luglio, XVI Legislatura, Roma.

Cressey, D. R. (1969). Theft of the Nation. The structure and operations of organized crime in America. New York: Harper & Ron.

della Porta, D., & Vannucci, A. (2011). The governance of corruption. London: Ashgate.

DIA (2008). Relazione semestrale [Annual Report], Roma.

Dickie, J. (2004). Cosa Nostra. A history of the Sicilian mafia. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

DNA (2008). Relazione annuale sulle attività svolte dal Procuratore nazionale antimafia e dalla Direzione nazionale antimafia, nonché sulle dinamiche e strategie della criminalità organizzata di tipo mafioso nel periodo 1° luglio 2007–30 luglio 2008 [Annual Report of the Antimafia National Judiciary Department 2007–2008], Roma.

DNA (2009). Relazione annuale sulle attività svolte dal Procuratore nazionale antimafia e dalla Direzione nazionale antimafia, nonché sulle dinamiche e strategie della criminalità organizzata di tipo mafioso nel periodo 1° luglio 2008–30 luglio 2009 [Annual Report of the Antimafia National Judiciary Department 2008–2009], Roma.

DNA (2011). Relazione annuale sulle attività svolte dal Procuratore nazionale antimafia e dalla Direzione nazionale antimafia, nonché sulle dinamiche e strategie della criminalità organizzata di tipo mafioso nel periodo 1° luglio 2010–30 luglio 2011 [Annual Report of the Antimafia National Judiciary Department 2010–2011], Roma.

DNA (2012). Relazione annuale sulle attività svolte dal Procuratore nazionale antimafia e dalla Direzione nazionale antimafia, nonché sulle dinamiche e strategie della criminalità organizzata di tipo mafioso nel periodo 1° luglio 2011–30 luglio 2012 [Annual Report of the Antimafia National Judiciary Department 2011–2012], Roma.

Easton, E., & Karaivanov, A. (2009). Understanding optimal criminal networks. Global Crime, 1–2, 41–65.

Falcone, G., & Padovani, M. (1992). Men of honour. The truth about the Mafia. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Finckenauer, J. O. (2005). Problems of definition: what is organized crime? Trends in Organized Crime, 8, 63–83.

Finger, B. (2012). ‘Ndrangheta in Deutschland: Versuch eines ÜberBlicks [‘Ndrangheta in Germany. An Overview], Berlin, Unpublished Manuscript.

Forgione, F. (2009). Mafia export: Come ‘ndrangheta, cosa nostra e camorra hanno colonizzato il mondo [Mafia Export: How ‘Ndrangheta, Cosa Nostra and Camorra colonize the world]. Milano: Baldini Castoldi Dalai Editore.

Gambetta, D. (1993). The Sicilian mafia: The business of private protection. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gambetta, D. (2009). Codes of the underworld. How criminals communicate. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gambetta, D. (2012). “The Sicilian mafia” twenty years after publication. Sociologica, 2, 1–11. doi:10.2383/35869.

Gennari, G. (2013). Le fondamenta della città [The foundation of the city]. Milano: Mondadori.

Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78, 1360–1380.

Gratteri, N. (2011). La Malapianta [The bad tree]. Milano: Mondadori.

Haug, S. (2011). Die Integration der Italiener in Deutschland zu begin des 21. Jahrhenderts [Italian integration in Germany at the beginning of the 21st century]. In O. Janz, & R. Sala (Eds.), Dolce Vita? (pp. 177–198). Frankfurt am Main: Campus.

Hess, H. (1998). Mafia & Mafiosi: Origin, power and myth. New York: New York University Press.

Hill, P. (2003). The Japanese Mafia: Yakuza, Law, and the State. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jamieson, A. (2000). The Antimafia. Italy’s fight against organized crime. London: Macmillan Press.

Kelly, R. J. (1997). Trapped in the folds of discourse. Theorizing about the underworld. In P. J. Ryan & G. E. Rush (Eds.), Understanding organized crime in global perspective (pp. 39–51). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Lavezzi, A. M. (2008). Economic structure and vulnerability to organised crime: Evidence from Sicily. Global Crime, 9, 198–220.

Lupo, S. (2008). Quando la mafia trovò l’America. Storia di un intreccio intercontinentale, 1888–2008 [When the mafia found America. History of an intercontinental plot, 1888–2008]. Torino: Einaudi.

Lupo, S. (2009). History of the mafia. New York: Columbia University Press.

Lupo, S. (2010). Potere criminale. Intervista sulla storia della mafia [Criminal power. Interview on the history of the mafia]. Roma-Bari: Laterza.

Moe, N. (2002). The view from Vesuvius. Italian culture and the southern question. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Moore, W. H. (1974). The Kefauver Committee and the politics of crime (1950–1952). Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

Morselli, C. (2009). Inside criminal networks. New York: Springer.

Morselli, C., Turcotte, M., & Renti, V. (2011). The mobility of criminal groups. Global Crime, 13, 165–188.

Nelly, H. S. (1969). Italians and crime in Chicago: the formative years, 1890–1920. American Journal of Sociology, 74, 373–391.

Paoli, L. (2003). Mafia brotherhoods: Organized crime, Italian style. New York: Oxford University Press.

Pignatone, G. & Prestipino, M. (2012). Il contagio. Come la ‘Ndrangheta ha infettato l’Italia [The countagios: how ‘Ndrangheta infected Italy]. Roma-Bari: Laterza.

Prinzing, M. (2008). La pistola è ancora nel piatto di spaghetti? La strage di Duisburg nella stampa tedesca di qualità [Is the gun still in the spaghetti? The Duisburg Massacre in the German quality press]. Problemi dell’informazione, 33, 88–107.

Reski, P. (2008). Mafia. Vom Paten, Pizzerien und Falschen Priesten [Mafia. Padrini, pizzerias and false priests]. München: Droemer Knaur.

Reuter, P. (1985). The organization of illegal markets: An economic analysis. New York: U.S. National Institute of Justice.

Reuter, P. (1987). Racketeering in legitimate industries. A study in the economics of intimidation. Santa Monica: The RAND Corporation.

Roth, J. (2009). Mafialand Deutschland [Mafialand Germany]. München: Wilhelm Heine.

Roth, J. (2011). L’economia criminale e la mafia in Germania [Criminal economy and mafia in Germany]. In C. La Camera (Ed.), Vincere la ‘Ndrangheta (pp. 57–63). Roma: Aracne.

Santino, U. (2006). Dalla mafia alle mafie [From Mafia to Mafias]. Soveria Mannelli: Rubettino.

Santino, U. (2012). Studying mafias in Sicily. Sociologica, 2, 1–18. doi:10.2383/35872.

Santoro, M. (2012). Introduction. The mafia and the sociological imagination. Sociologica, 2, 1–36. doi:10.2383/35868.

Saviano, R. (2007). Gomorrah. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Scaglione, A. (2011). Reti mafiose. Cosa Nostra e Camorra: organizzazioni criminali a confronto [Mafia Networks. Cosa Nostra and Camorra: Criminal Organizations in Comparison]. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Schneider, J., & Schneider, P. T. (2003). Reversible destiny: Mafia, antimafia, and the struggle for Palermo. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sciarrone, R. (2006). Passaggio di frontiera: La difficile via d’uscita dalla mafia calabrese [Border crossing. The difficulty of leaving the Calabrian Mafia]. In A. Dino, (Ed.), Pentiti (pp. 129–162). Roma: Donzelli.