Abstract

Retrieving personal memories may provoke different emotions and a need for emotion regulation. Emotional responses have been studied scarcely in relation to autobiographical memory retrieval. We examined the emotional response to everyday involuntary (spontaneously arising) and voluntary (strategically retrieved) memories, and how this response may be different during dysphoria. Participants (20 dysphoric and 23 non-depressed) completed a structured diary where the intensity of basic emotions and regulation strategies employed upon retrieval of memories were rated. Brooding, memory suppression, and emotional suppression were higher for all individuals’ involuntary memories than voluntary memories. Negative emotions and regulation strategies were greater for dysphoric individuals for both involuntary and voluntary memories after controlling for the valence of the remembered events. The results provide new insights into the understudied topic of emotional responses to everyday memories and suggest a novel interpretation of the intrusive nature of memories in psychological disorders, such as depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Memories can make us laugh, smile or cry and even color our mood for an extended period of time. Such emotional responses to everyday personal memories are important in order to understand depression and other affective disorders (e.g., Joormann and D’Avanzato 2010; Philippe et al. 2011) as well as for understanding the complex interplay between emotion, emotion regulation, and autobiographical remembering more broadly (Berntsen 2015). However, little research has been conducted on emotional responses to everyday autobiographical memories, both when such memories are retrieved voluntarily (i.e., strategically and controlled), and when they come to mind involuntarily, that is, with no preceding retrieval attempt (Berntsen 1996). The aim of the present study is to examine emotion regulation processes in response to everyday memories and how they are affected by dysphoria.

In a number of studies, involuntary memories sampled in diary studies have been compared with voluntary memories recalled in response to word cues as part of the same diary study. Two differences have consistently been found. First, involuntary autobiographical memories more often than their voluntary counterparts refer to memories of specific episodes—that is, experiences that took place at a specific time and place in the participant’s life (e.g., Berntsen 1998; Berntsen and Hall 2004; Johannessen and Berntsen 2010; Mace 2004; Schlagman and Kvavilashvili 2008; Schlagman et al. 2009; Watson et al. 2013, but see; Rubin et al. 2008, 2011). Second, involuntary autobiographical memories more often than their voluntary counterparts are accompanied by an identifiable emotional impact at the time of retrieval (Berntsen and Hall 2004; Finnbogadottir and Berntsen 2011; Rubin et al. 2008, 2011; Watson et al. 2012), although this effect is, in some cases, found only for negative mood impact (Berntsen and Jacobsen 2008; Johannessen and Berntsen 2010).

According to Berntsen (2009, 2010), this greater emotional impact of involuntary memories may reflect that the unplanned and uncontrolled nature of involuntary retrieval leaves little room for antecedent-focused emotion regulation strategies, such as reappraisal, but instead places the emphasis on response-focused strategies, such as the suppression of the emotional expression (Gross 1998). However, this proposal has not been examined. Thus far, the emotional response to autobiographical memory at retrieval has been assessed via single-item ratings of the global emotional impact or mood change accompanying the autobiographical memory (e.g., Berntsen 2001; Berntsen and Hall 2004; Rubin et al. 2008); thus, more fine-grained analyses of components of the emotional response are lacking.

According to the process model of emotion (Gross 1998; Gross and Barrett 2011; Rottenberg and Gross 2007), at least two components of the emotional response can be distinguished. The first component is the generation of discrete emotions, and the second component is emotional regulatory processes. First, the generation of emotions starts with the evaluation of external or internal cues. The ensuing emotional reaction is then represented across behavioral, experiential, and physiological dimensions which vary in intensity (Gross 1998). Second, emotion regulation refers to a set of processes or strategies that are employed to increase, maintain, decrease, or prevent the launching of an emotion, such as emotion suppression or reappraisal (Gross 1998; Gross and Barrett 2011). In the present study, we aim to examine both components in response to involuntary versus voluntary remembering. In addition, our goal is to examine whether these processes are affected during dysphoria.

Several studies have shown that the relationship between autobiographical remembering and emotion vary with depressive symptomatology (Joormann and D’Avanzato 2010; Kvavilashvili and Schlagman 2011; Plimpton et al. 2015; Walker et al. 2003). This is consistent with evidence that individuals with depression show various deficits in their emotional response, such as diminished positive affect (Barlow et al. 2004), more intense negative emotions (Karreman et al. 2013), and poor emotion regulation skills (Berking et al. 2014). In other words, individuals with depression show emotional dysregulation, broadly speaking (Aldao et al. 2010; Hofmann et al. 2012; Mennin et al. 2007). However, only few studies have investigated specific components of the emotional response to autobiographical memory during depression.

Rottenberg et al. (2005) examined emotion regulation in written memory narratives in individuals with depression and found that the individuals who expressed greater sadness in their writing experienced a more benign course of the disorder. This agrees with evidence that emotional suppression correlates positively with symptom severity, whereas greater acceptance of the emotion predicts positive outcomes (Campbell-Sills et al. 2006; Ehring et al. 2008).

Newby and Moulds (2012) found that helplessness, sadness, anxiety, shame, guilt, and disgust, in that order, were the most intense emotions accompanying involuntary intrusive memories in a sample of depressed patients. Other emotions assessed were anger, fear, detachment, numbness, surprise, and happiness, all of which were rated at a lower level of intensity. Reynolds and Brewin (1998) compared the intensity of emotions associated with the most prominent intrusion reported by patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and healthy controls, respectively. They found no differences between the PTSD and depression groups, but both clinical groups reported more intense depression, anxiety, and guilt associated with their intrusions, compared with healthy controls. These pioneering studies focused exclusively on the most distressing intrusive memory and did not examine the emotions associated with other (non-intrusive) involuntary memories.

Addressing such a gap in the literature, Watson et al. (2012) examined everyday involuntary (and voluntary) memories in depression. They showed that everyday involuntary memories had a greater mood impact than voluntary memories upon retrieval among both depressed and never depressed individuals. Compared with controls, depressed individuals reported a greater negative mood change in response to the memories. There were no significant interactions between retrieval mode and group, suggesting that the greater negative mood change in the depressed group was present in response to both involuntary and voluntary memories.

The Present Study

Previous studies have suggested that autobiographical memories are associated with greater negative emotional impact upon memory retrieval when individuals experience dysphoria and depression than during low or no depressive symptomatology. However, these studies did not examine the intensity of specific emotions as well as specific emotion regulation strategies directed at the recalled memory. Here, we aimed to obtain a more detailed representation of how individuals respond emotionally to everyday memories. We focused on two components of the emotional response, intensity and regulation strategies. Disruptions of these two emotional components have been implicated in the development and maintenance of emotional disorders (Barlow et al. 2004; Mennin et al. 2007). We studied emotional intensity and regulation in relation to involuntary and voluntary autobiographical memory and their possible interactions with dysphoria (i.e., elevated depressive symptoms). Specifically, we examined the intensity of fear, sadness, anger, and happiness, considered as basic emotions according to prominent theories (Ekman 1992) in response to the retrieval of involuntary and voluntary autobiographical memories. We examined five emotion regulation strategies (brooding, reflection, thought suppression, emotional expression suppression, and reappraisal) selected from the emotion regulation literature (e.g., Gross and John 2003; Newby and Moulds 2012; Whitmer and Gotlib 2011) in response to memory retrieval.

To that end, we employed a structured diary method, which is a well-established method extensively employed in autobiographical memory research (e.g., Berntsen and Hall 2004). Participants rated questions concerning their emotional response to the autobiographical memories in addition to other memory characteristics. All the ratings relevant to the key measures were completed immediately after the memories were retrieved to avoid bias from retrospective assessment (Ericsson and Simon 1980; Nisbett and Wilson 1977). We conducted a systematic comparison between involuntary and voluntary (word-cued) memories, and conducted between group-comparisons of dysphoric and non-depressed individuals.

The following hypotheses motivated the study. First, previous findings indicate that involuntary memories provoke a greater physical reaction and mood change (see Berntsen 2009, 2015, for reviews). We assumed that this reaction would also be captured in the intensity and regulation of discrete emotions accompanying the memories. Therefore, we hypothesized intensity would be greater for all four emotions in response to involuntary, compared with voluntary, memory retrieval. Second, following the idea that involuntary recall leaves little room for antecedent-focused emotion regulation, due to its uncontrolled nature, we expected greater engagement in response-focused emotion regulation strategies (i.e., when an emotion has been already launched), including reflection, brooding, memory and emotional suppression, when retrieving involuntary memories relative to voluntary memories. However, we did not expect the use of reappraisal (i.e., an antecedent-focused strategy) to be greater for involuntary memories. The unexpected nature of involuntary memories leaves little opportunity to reappraise the content of a memory before an emotion is generated (Berntsen 2009).

Third, in an extension of cognitive-affective models of depression (e.g., Karreman et al. 2013; Mennin et al. 2007; Whitmer and Gotlib 2011), and from research on intrusive memories (e.g., Williams and Moulds 2007), we predicted that dysphoric individuals would rate negative, but not positive, emotions as more intense (i.e., no difference in the intensity of happiness was expected). Fourth, we expected greater employment of brooding, memory suppression, and emotional expression suppression among the dysphoric than the non-depressed individuals in response to the memories. No between-group differences in the ratings of reflection were expected as evidence from correlational studies indicates that greater reflection is problematic only at more severe levels of depressive symptoms (Whitmer and Gotlib 2011). Lower reappraisal use was expected during dysphoria (Aldao et al. 2010). Finally, the greater emotional intensity and greater emotion regulation in the dysphoric group was expected to apply to both involuntary and voluntary memories. Thus, only significant main effects (e.g., effects of retrieval mode and dysphoria group) were predicted, whereas no interactions were expected.

Method

Participants

The final sample consisted of 20 dysphoric (two men) and 23 non-depressed (two men) participants. The groups were determined on the basis of the participants’ BDI-II (Beck Depression Inventory—II; Beck et al. 1996) scores both prior to the beginning of the diary (T1) and after completing the diary (T2). A BDI-II score equal to or greater than 11 represents the lower end of the range correlating with mild depressed mood (i.e., dysphoria) among young adults (Sprinkle et al. 2002). Thus, a score of 10 was selected as the cut-off score for maintaining distinct groups. The BDI-II scores of the non-depressed participants ranged from 1 to 6 at T1, and from 0 to 10 at T2, whereas the BDI-II ranges of the dysphoric group were 16–49 at T1, and 11 to 47 at T2. As a group, the non-depressed individuals were in the non-clinical range of depressive symptoms at both T1 and T2, whereas the dysphoric group presented symptoms of moderate severity (Beck et al. 1996) at both T1 and T2 (See Table 1 for the means).

These participants were selected for the main analyses from a sample of 31 initially (T1) dysphoric individuals and 26 initially non-dysphoric individuals.Footnote 1 Of the initially dysphoric participants, eight participants improved to a non-clinical level of depressive symptoms by T2 (BDI ≤ 10), and three dropped out. Of the initial 26 non-dysphoric individuals, one participant moved to a dysphoric range by T2 (BDI = 18), and two dropped out.

Participants in the final sample (N = 43) were 22.83 years old (SD = 1.73) and all were university students. Ninety-three percent of the participants were Caucasian (n = 40), 4.65% of other ethnic group (n = 2), and 2.32% of Asian origin (n = 1). Significantly fewer participants in the non-depressed group (n = 2, 8.69%) than in the dysphoric group (n = 8, 40%) were receiving professional help for emotional problems at the beginning of the study (e.g., counseling, pharmacotherapy), χ2(43) = 5.87, p = .015. Thus, the groups were statistically and clinically different during the entire duration of the memory diary (see Table 1).

Materials

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al. 1996)

The BDI-II is a self-report questionnaire assessing depressive symptoms. Each of the 21 symptom items has four corresponding response options that reflect increasing symptom frequency or severity. The BDI-II correlates strongly (r = .83) with the number of depressive symptoms assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) (Huprich and Roberts 2012; Sprinkle et al. 2002). (See Table 1 for the BDI-II internal consistency).

Memory Diary (Berntsen and Hall 2004)

A well-established method to collect involuntary and word-cued autobiographical memories was employed in the current study. This method has been used previously with clinical groups, such as individuals diagnosed with depression (Watson et al. 2012) or PTSD (Rubin et al. 2011). Participants were instructed to record 10 involuntary and 10 word-cued memories (i.e., voluntary) over the course of several days by following the three steps described below. Participants carried a small notebook with them for the duration of the study in which they were to record a maximum of two involuntary memories per day and immediately rate them along different dimensions. The involuntary memories had to be the first two that took place during a given day to avoid a selection bias for certain memories. In order to ensure that only actually spontaneous memories were recorded, there was no requirement that involuntary memories had to be recorded every day. The diaries were complete once every participant had 10 involuntary and 10 voluntary memories, with the recording period being self-paced. Because the participants may have recorded none, one, or two involuntary memories per day, the completion time varied from person to person.

As a first step for completing the diary, participants rated their mood before the involuntary memory entered into consciousness (−2 = Very Negative to +2 = Very positive), then they rated the emotional intensity associated with each memory on a scale from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (A great deal) for fear, anger, sadness, and happiness when the memory popped up. Five items then assessed the emotion regulation strategies. These items were taken from well-established inventories assessing trait-like emotion regulation strategies (Ruminative Responses Scales [RRS], Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow 1991; Emotion Regulation Questionnaire [ERQ]; Gross and John 2003; White Bear Suppression Inventory [WBSI]; Wegner and Zanakos 1994) and were slightly adjusted for the context of the memory diary: Brooding (I thought: “Why do I always react this way?”), reflection (I analyzed the event to understand my feelings), memory/thought suppression (I tried not to think about the memory), emotional expression suppression (I controlled my emotion by not expressing it), and reappraisal (I changed the way I was thinking about the situation). These items had large factorial loadings (rs > 0.59) in their original inventory and were also judged to have good face validity. The items on emotion regulation strategies were rated on a 1 to 5-point scale indicating the extent to which individuals employed different strategies to regulate their emotions in response to the memory. Finally, questions were included about the age of the memory (How long ago did the event happen?), the centrality of the event for the person’s identity (The event is an important part of my identity, and The event has become a central part of my life story; each item rated from 1 = Not at all to 5 = A great deal), whether the memory referred to a specific event happening at a particular point in time or whether it was a non-specific, general event representation (1 = specific or 0 = non-specific), the overall valence of the event when it took place (How positive or negative were your emotions at the time of the event? Very negative = −2 to Very positive = +2), and subjective memory frequency (Have you previously thought about this memory? Never = 1 to Very often = 5). In the second step of the memory diary participants were instructed to transfer by the end of each day the in-vivo notebook ratings to a structured diary that had been provided to them by the experimenter.

Third, after transferring the involuntary memory ratings and answering the additional questions described above, participants uncovered a cue word in their diaries for which they generated a voluntary memory. The cues provided were taken from Watson et al. (2012) and Berntsen and Hall (2004). The cues are a balanced mixture of objects, emotions, places, and events (e.g., flowers, sad, happy, school, divorce). These cues generated by Berntsen and Hall (2004) are comparable to natural cues for involuntary memories. In employing these cues, we aimed to elicit memories that were similar in content (Berntsen 1998), but different in cognitive effort (i.e., employment of a top-down search strategy) required to retrieve the memory. Participants then answered the same series of questions they had completed for the involuntary memories (cf. above) but this time for the voluntary memories.

Participants were told that it was acceptable to exclude very personal or distressing memories that they did not want the experimenter to read. Important advantages of this memory diary method include reporting and rating memories immediately rather than retrospectively, not taxing participants by reporting numerous memories on the same day and minimizing a bias in the selection of the memories to report by including only the first two memories of the day (e.g., Berntsen 2009).

Procedure

Prior to the commencement of the memory diary, participants had completed a battery of questionnaires for a larger online survey study (n = 220; Del Palacio-Gonzalez and Berntsen 2017) including the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Blevins et al. 2015), the Involuntary Autobiographical Memory Inventory (IAMI; Berntsen et al. 2015), the Centrality of Event Scale (CES; Berntsen and Rubin 2006), the RRS (Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow 1991), the ERQ (Gross and John 2003), the WBSI (Wegner and Zanakos 1994), and a recent life event checklist. The materials were given in Danish. The BDI-II, ERQ, CES, and WBSI had been translated and back-translated (following standard procedures), and employed in published studies (Christensen et al. 2009; Finnbogadottir and Berntsen 2011; Harris et al. 2014; Hesse 2006; Rasmussen and Berntsen 2010). The PCL-5 and the RRS were translated (and back-translated) in relation to the online study by both bilingual Danish and English native speakers. The internal consistency of all the questionnaires employed in the present study (n = 43) ranged from good to excellent (see Table 1). In the current study, the data from these questionnaires were only employed to characterize differences between groups, however, more detailed analyses of those data are found elsewhere (Del Palacio-Gonzalez and Berntsen 2017).

The majority of the participants were recruited from the online study. A smaller portion of participants were recruited from local psychological services for university students across the city. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Participants who had scored either BDI ≤ 6 or BDI ≥ 16 in the online study, and who had provided consent to be contacted for future studies, were invited for the present study within a few days. Participants met individually with an experimenter blind to the participant’s BDI-II score. Key definitions (e.g., involuntary memory, specific memory) and all the steps for completing the memory diary were thoroughly explained to the participants following standardized instructions. Participants were provided with a kit including a notebook for immediate recording, the structured memory diary booklet, and the written instructions of how to complete the memory diary, which were used to complement the oral instructions provided at the meeting. Participants received a reminder email about the study every two weeks, unless they had completed the diary between reminders. Upon finishing the memory diary, participants completed another BDI-II to re-assess symptom severity. Participants met again with an experimenter or the first author to return the memory diary. Participants were asked if they had purposefully left out any memories. Six participants in the dysphoric group, and seven in the non-depressed group left out memories because they were too personal or stressful, χ2(32) = 0.24, p = .28. Lastly, participants were fully debriefed and compensated for their participation with 150 DKK (US$22).

Results

Time to Completion and Differences between Groups

Participants took 21.68 days (SD = 14.18) to complete the memory diary. No differences were found in time-to-completion between the non-depressed (M = 22.6 days, SD = 13.8) and the dysphoric groups (M = 19.8, SD = 14.9), t(41) = 0.64, p = .526. Table 1 shows that, as a group, the dysphoric individuals reported a moderate range of depressive symptoms (BDI-II > 20; Beck et al. 1996) both at T1 and T2. Further, the non-depressed and dysphoric groups were statistically different across all trait-like emotion regulation strategies in the expected direction (e.g., higher brooding among dysphoric participants).

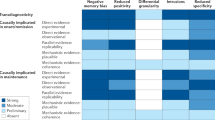

Data Analysis Strategy

A series of 2 (Retrieval: Involuntary versus Voluntary) by 2 (Group: Non-depressed versus Dysphoric) mixed ANOVAs were conducted to examine within-subject differences in emotional intensity and regulation of autobiographical memories retrieved involuntarily and voluntarily (i.e., word-cued), and between-subject differences by dysphoria group. A Bonferroni correction for nine comparisons (p < .005) was applied to interpret the main analyses presented in Table 2. Results with p < .05 but greater than 0.005 are treated as trends.

Emotional Intensity of Autobiographical Memories

The effect of Group was significant for fear, sadness, and anger but not for happiness. Thus, the hypothesis that dysphoric individuals would experience more intense negative emotions compared with the non-depressed individuals when recalling autobiographical memories was supported. Contrary to expectation, the effect of Retrieval on emotional intensity was not significant. However, there were trends for a Retrieval effect on fear (p = .015) and anger (p = .011), for which involuntary memories were more intense than voluntary memories, consistent with predictions. All the interactions were non-significant (ps > 0.13), thus suggesting that the emotional intensity pattern of the dysphoric individuals for involuntary and voluntary memories was not statistically different from that of the non-depressed participants. Means, SDs, and confidence intervals (CI 95%) are presented in Table 2.

Emotion Regulation of Autobiographical Memories

The effect of Group was significant for brooding, suppression of emotional expression, and memory suppression. Dysphoric individuals reported a greater use of these strategies than non-depressed individuals upon retrieving autobiographical memories. There was a trend for higher reflection in dysphoria (p = .013). No significant differences in reappraisal by dysphoria group were found. These results supported the hypothesis for greater brooding, memory suppression, and emotional suppression in dysphoria in response to everyday autobiographical remembering. There was a significant effect of Retrieval on brooding, suppression of emotional expression, and memory suppression, and a trend for a difference in reappraisal by retrieval mode (p = .015). For these strategies, participants reported greater use associated with involuntary memories than with voluntary memories. There were no significant differences in reflection by retrieval mode. These findings partially supported our hypotheses regarding emotion regulation and retrieval mode. The interactions were all non-significant (ps > 0.38), thus showing that the differences between dysphoric and non-depressed individuals in their use of regulation strategies were consistent across the two retrieval modes, consistent with our predictions (see Table 2).

Pre-Retrieval Mood and Valence of the Event

It might be suggested that the participants’ mood before the retrieval of memories led dysphoric individuals to retrieve mood-congruent (and thus negative) memories. However, mood immediately preceding the retrieval of both involuntary and voluntary memories was not statistically different between groups (see Table 3).

There were significant differences in the valence of the remembered events reported by dysphoric versus non-depressed individuals. As presented in Table 3, dysphoric individuals reported, not surprisingly, more memories of negative events than the non-depressed group (no differences were found by retrieval mode, which is consistent with previous work). Therefore, a series of supplementary ANCOVAs were conducted, contrasting emotional intensity and emotion regulation between groups while controlling for the average valence ratings. The valence ratings of the remembered events was covaried separately for involuntary and voluntary memories, thus resulting in 18 contrasts (four emotions and five emotion regulation strategies for involuntary memories, and four emotions and five strategies for voluntary memories).

Consistent with the findings reported in Table 2, group differences for the emotional intensity of sadness (ps < 0.001), anger (ps < 0.003), and fear (ps < 0.05) were significant. Happiness intensity remained non-significant (ps > 0.05). Similarly, the group differences for brooding (ps < 0.001), emotional suppression (ps < 0.005), memory suppression (ps < 0.03), and reflection (ps < 0.05) were significant. Reappraisal remained non-significant (ps > 0.05). Note that applying a Bonferroni correction for 18 contrasts (p = .003) would turn some of the ANCOVA findings into trends. However, such conservative criterion might result in rejecting actual differences (Type II error; Perneger 1998). Importantly, the pattern of group differences in emotional intensity and emotion regulation presented after controlling for valence is remarkably similar to that of Table 2. This consistency between the main and the additional analyses supports the validity of our findings.

Specificity, Age, Frequency, and Centrality of Event

Consistent with previous work, there was a greater proportion of specific involuntary memories than voluntary memories (See Table 3; see Berntsen 2009, for a review). The effect of Group and the Retrieval x Group interaction were not significant for memory specificity. We conducted supplementary analyses to explore whether memory specificity could explain some of the differences found between retrieval modes regarding emotional intensity and emotion regulation. Specificity had been coded by the participant as either specific or non-specific. Following Berntsen and Hall (2004), mean ratings on intensity and emotion regulation were computed for specific involuntary, specific voluntary, non-specific involuntary, and non-specific voluntary memories, respectively, and compared in a 2 (retrieval: involuntary versus voluntary) x 2 (specificity: specific versus non-specific) repeated measures ANOVA.

A significant effect of Retrieval emerged for fear, brooding, memory suppression, and emotional suppression with greater scores for involuntary memories regardless of specificity (ps < 0.04). Further, Specificity had a significant effect on fear, memory suppression, emotional suppression, and reappraisal, with higher ratings in response to the retrieval of specific memories (ps < 0.007). Specificity was also significant for happiness, the direction being opposite however; non-specific memories were rated as more intensely happy (p = .002). The interactions were all non-significant. The results suggest that the effects of specificity and retrieval are independent from each other. However, the higher proportion of specific memories among the involuntary memories may help to explain the heightened emotional response observed for involuntary memories, in addition to the effects of retrieval form.

The retrieval effect was not significant for other memory characteristics, including valence, age of memory, and centrality, suggesting that involuntary and voluntary memories were comparable across different indicators of memory content. Similarly, there were no significant group effects for age, subjective memory frequency, and centrality of the events (see Table 3). That is, all participants (dysphoric and non-depressed) rated their memories (both involuntary and voluntary) similarly in terms of age, frequency, and identity centrality.

Discussion

The present study examined emotional responses to the retrieval of everyday involuntary versus voluntary autobiographical memories in dysphoric versus non-depressed individuals. Consistent with our predictions, a number of key differences were found between involuntary and voluntary memories. First, involuntary memories were associated with greater brooding, memory suppression, and suppression of emotional expression for all individuals. There were trends in the expected direction towards more intense fear and anger when retrieving involuntary memories compared with voluntary memories. Second, consistent with hypotheses, dysphoric individuals reported more intense fear, sadness, and anger when retrieving everyday autobiographical memories relative to non-depressed individuals. Dysphoric individuals also engaged in greater brooding, memory suppression, and suppression of emotional expression when retrieving autobiographical memories. This pattern was consistently found for both involuntary and voluntary memories. Neither mood preceding the retrieval of memories, nor the valence of the remembered events, accounted for these differences.

The overall differences between involuntary and voluntary retrieval modes are consistent with the heightened emotional impact previously documented for involuntary memories (e.g., Berntsen and Hall 2004; Watson et al. 2012; Berntsen 2009, 2015, for reviews). Berntsen and colleagues have suggested that the greater emotional impact of involuntary memories may be related to a greater need for regulating emotions in response to involuntary memories due to their uncontrolled nature (Berntsen 2015; Berntsen and Watson 2014), and that the uncontrollable nature of involuntary memories leaves little opportunity for antecedent-focused emotion regulation (e.g., reappraising the memory before it is fully retrieved). Thus, response-focused emotion regulation would be expected to dominate (Gross 1998). The finding that brooding, memory suppression, and emotional suppression were greater for involuntary memories than for voluntary memories is supportive of this suggestion. Given that involuntary memories are unexpected and may arise in a variety of contexts (i.e., both in public settings and in privacy), individuals may feel a greater need to exert control over the memories both cognitively (e.g., memory suppression) and behaviorally (e.g., emotional suppression), so that they do not interfere with, or interrupt, any activities being performed at the time of recall. Reappraisal showed a non-significant trend in the same direction.

In contrast to the present findings, Watson et al. (2012) found that rumination did not differ for involuntary and voluntary memories. However, methodological differences between Watson et al. (2012) and the present study may account for this inconsistency. First, here we used differentiated measures for brooding and reflection as opposed to measuring rumination as a single construct (Whitmer and Gotlib 2011). Second, the employment of these strategies was assessed immediately after the memory came to mind, as opposed to obtaining retrospective estimates of how much the participants generally had ruminated about this memory.

Despite these positive findings, the hypotheses for emotional intensity and emotion regulation of involuntary memories were only partially supported, as significant differences were not identified for each and every emotion or emotion regulation strategy assessed. Involuntary memories were not associated with a more intense experience of happiness or a greater involvement of reflection at the time of retrieval.

Our hypotheses relating to emotional intensity and regulation of involuntary memories were formulated by inferring that the greater emotional impact of involuntary memories found in previous studies (e.g., Berntsen 2001; Berntsen and Hall 2004; Watson et al. 2012), would be reflected in a greater intensity of all emotions and regulation strategies at the time of retrieval. However, this was not the case. When individuals have been asked to rate the global emotional impact of involuntary memories in past studies (e.g., Berntsen 2001; Berntsen and Hall 2004; Rubin et al. 2008), they have possibly made a heuristic evaluation encompassing both the intensity of various discrete emotions, perceived physical reactions, and the effort required to regulate the emotions associated with the memory. Thus, a general evaluation of mood impact may not capture the conceptualization and operationalization of emotional intensity for specific emotions and emotion regulation across various strategies employed in the present study (Gross 1998; Rottenberg and Gross 2007). In light of the current findings, we speculate that this heuristic evaluation of the emotional impact of memories found in previous work may be associated with the intensity of some (e.g., anger and fear), but not all, emotions and some, but not all, emotion regulation strategies.

Although the present results require replication, a preliminary conclusion is that involuntary memories are associated with greater employment of memory suppression, emotional suppression, brooding, and possibly with experiencing greater intensity of some negative emotions upon retrieval. The present work therefore provides a conceptual replication and important extension of previous research on emotional responses to involuntary and voluntary memories.

The current findings also have implications for theories of autobiographical memory and depression. The hypotheses for greater intensity of fear, sadness, and anger, and greater engagement in brooding, memory suppression, and emotional suppression among dysphoric individuals compared with the non-depressed individuals were supported. No significant interactions between group and retrieval mode were identified, suggesting an overall heightened emotional response to everyday memories in the dysphoric group.

More intense negative emotions associated with autobiographical memories during dysphoria may at least partly be explained by the weaker fading affect bias described by Walker et al. (2003). In their study, dysphoric individuals reported overall more intense negative emotions when recalling selected voluntary memories than non-depressed individuals even after controlling for the age of events. Our findings suggest that the weaker fading of negative emotions during dysphoria may be extended to involuntary memories and a variety of voluntary memories. Alternatively, individuals with dysphoria may simply have higher levels of neuroticism (Karreman et al. 2013), which in turn affects their appraisal of all autobiographical memories and their emotion regulation strategies. Obviously, these two explanations are not mutually exclusive.

In terms of emotion regulation, the current findings showed remarkable similarities between emotion regulation upon retrieval of autobiographical memories and trait-like emotion regulation (i.e., dispositional tendencies to respond to emotions irrespective of the trigger of such emotions) during depression in general (Ehring et al. 2008; Whitmer and Gotlib 2011), and emotional responses in relation to intrusive memories in particular (Newby and Moulds 2010; Williams and Moulds 2007). That is, dysphoric individuals engaged in greater brooding, emotional suppression, and memory suppression for both involuntary and voluntary memories than did non-dysphoric participants. These findings raise at least two important questions for clinical theories of emotion and depression. First, to what extent is the regulation of everyday autobiographical memory different from trait-like regulation strategies? There is emerging evidence that emotion regulation of intrusive memories (Williams and Moulds 2007) and regulation of emotions associated with single events (Del Palacio-Gonzalez and Berntsen 2017) explains variance in depressive symptoms beyond trait-like emotion regulation. Therefore, we believe that the emotional response to autobiographical memories may constitute a facet of the broader relationship between cognition and emotion relevant for advancing the understanding of depression and other psychopathologies (see Rubin et al. 2008 for a similar discussion regarding intrusive memories in PTSD).

A second question raised by current findings pertains to the similarities of the emotions and regulation strategies associated with intrusive memories and everyday involuntary memories when experiencing depressive symptoms. The emotional response to everyday involuntary memories during dysphoria showed a similar pattern to that of intrusive memories found in other studies (e.g., intense sadness, higher brooding, and suppression of memories; e.g., Newby and Moulds 2010, 2012). When considered in the context of the current findings, it would seem that the “intrusiveness” of intrusive memories may at least partly be explained by a combination of a normative heightened emotional response to involuntary memories in conjunction with a heightened dispositional emotional response to all everyday memories by dysphoric individuals (e.g., Berntsen and Watson 2014).

The current findings should be interpreted with some limitations in mind. The sample was composed primarily of young women, thus raising issues of generalizability. Specifically, there are documented age and gender differences in the employment of specific regulation strategies. For example, women ruminate more, whereas men employ more thought suppression (Brummer et al. 2014; Zimmermann and Iwanski 2014). Similarly, there are some gender differences in the physiological and neurological aspects of the emotional response to autobiographical memories (albeit to a lesser extent in self-reports; Labouvie-Vief et al. 2003; Jacques et al. 2011). The sample size was comparable to other diary studies on autobiographical memory (e.g., Watson et al. 2012), but still relatively small. As a consequence, we were able to detect only relatively large effects.

In addition, because we restricted our study to basic emotions, we included happiness as the only positive emotion. Therefore, the positive side of emotional responses to everyday autobiographical memories was under-explored in the current study. Relatedly, assessing complex emotions, such as guilt and hostility, may be particularly important in the context of depressive symptoms (Philippe et al. 2011). Similarly, we restricted our analyses to five regulation strategies commonly investigated to understand emotion regulation deficits among clinical populations (Aldao et al. 2010). In doing so, we have expanded from intrusive memory research, which typically focuses on thought suppression and rumination. However, other emotion regulation strategies, such as acceptance and distraction, were not included and should be considered in future research.

Another limitation pertains to the word-cued paradigm employed to sample voluntary memories, which may be less representative of the day-to-day experience of voluntary memories than more naturalistically sampled voluntary memories (Rasmussen et al. 2014). On the other hand, more naturalistically sampled voluntary memories may be harder for participants to distinguish from involuntary memories, thus blurring the differences. Here, we used the cue word method, for which we can be certain that retrieval is intentionally initiated and which is the most common technique for sampling voluntarily retrieved autobiographical memories (Crovitz and Shiffman 1974). To ensure comparability with the involuntary memories, the cue words we used were selected to match types of cues found to activate everyday involuntary memories.

Lastly, although our groups were formed on the basis of differences in depressive symptoms, some of the differences in the emotional response may be related to elevations in other symptoms, particularly anxiety (see Hofmann et al. 2012). Therefore, claims for the specificity of the emotional response to autobiographical memory in dysphoria cannot be made.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the present study suggests important lines of future research. First, future research should examine whether emotional intensity may influence emotion regulation strategies in response to autobiographical remembering. Some existing evidence suggests that the correlation between emotional intensity and regulation in general is low (Mennin et al. 2007), but more research is needed to examine this relation in the context of autobiographical memory retrieval specifically. Second, future research may assess individual differences regarding both emotion regulation strategies and executive functions, such as inhibition, set-shifting, and attention biases. These variables may have an impact on different facets of the emotional response. For instance, deficits in emotional set-shifting may affect the individuals’ ability to disengage from thinking of the negative past, leading to, or maintaining, rumination (De Lissnyder et al. 2010; MacLeod and Bucks 2011). Lastly, exploratory findings suggested that memory specificity may have a role in the emotional response to autobiographical memories. This relationship should be examined further to understand the mechanisms behind it.

Conclusions

We expanded upon previous studies on the emotional impact of autobiographical memories and upon emotion regulation of intrusive memories by assessing the intensity of a selection of emotions and regulation strategies upon the retrieval of everyday autobiographical memories. Such systematic examination of emotions and regulation in relation to autobiographical remembering is unique in the literature, and adds to our understanding of the emotional response to both everyday memories and intrusive memories. There were greater memory and emotional suppression, greater brooding, as well as trends for more intense negative emotions upon the retrieval of involuntary memories compared with that of voluntary memories among all participants. However, dysphoric individuals differed from non-depressed individuals in how they responded to their memories in both retrieval modes. Across both retrieval modes, dysphoria was associated with greater brooding, memory suppression, and emotional suppression. This is similar to what has been found for trait measures of emotion regulation. Dysphoric individuals also reported greater negative emotions associated with their memories. The valence of the remembered events did not account for the differences found. Taken together, these findings may suggest new ways of understanding the emotionality associated with intrusive memories in depression based on a more general response pattern to everyday involuntary and voluntary memories.

Notes

Supplementary analyses were conducted with the original sample of all diary completers (n = 24 non-depressed, and n = 28 dysphoric individuals, N = 52). The pattern of results for the emotional regulation strategies was exactly the same as that presented on Table 2 (but with the expected variations in effect size and significance level). There were significant differences for brooding, emotional suppression, and memory suppression for both Retrieval mode (ps < 0.004; with involuntary memories associated with higher ratings) and Group (ps < 0.005; with dysphoric individuals reporting higher ratings). Reflection remained as a trend. The pattern for emotional intensity was the same for Group differences (dysphoria was associated with greater fear, sadness, and anger, ps < 0.002) and no differences were identified for happiness. The Retrieval effect pattern was slightly different. There were trends for greater fear (p = .05), sadness (p = .03), and happiness (p = .04), for involuntary memories, and no differences for anger (p = .13). Overall, these results support our final conclusions. There were higher ratings for brooding, memory suppression, and emotional suppression for involuntary memories and dysphoric individuals, higher ratings for negative emotions in dysphoria for both retrieval modes, and trends for greater intensity of various emotions in association with involuntary memories.

References

Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 217–237.

Barlow, D. H., Allen, L. B., & Choate, M. L. (2004). Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders. Behavior Therapy, 35, 205–230.

Beck, A.T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation.

Berking, M., Wirtz, C. M., Svaldi, J., & Hofmann, S. G. (2014). Emotion regulation predicts symptoms of depression over five years. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 57, 13–20.

Berntsen, D. (1996). Involuntary autobiographical memories. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 10, 435–454.

Berntsen, D. (1998). Voluntary and involuntary access to autobiographical memory. Memory, 6, 113–141.

Berntsen, D. (2001). Involuntary memories of emotional events: Do memories of traumas and extremely happy events differ? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 15, S135–S158.

Berntsen, D. (2009). Involuntary autobiographical memories: An introduction to the unbidden past. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Berntsen, D. (2010). The unbidden past: Involuntary autobiographical memories as a basic mode of remembering. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19, 138–142.

Berntsen, D. (2015). From everyday life to trauma: Research on everyday involuntary memories advances our understanding of intrusive memories of trauma. Clinical perspectives on autobiographical memory (pp. 172–196). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Berntsen, D., & Hall, N. M. (2004). The episodic nature of involuntary autobiographical memories. Memory & Cognition, 32, 789–803.

Berntsen, D., & Jacobsen, A. S. (2008). Involuntary (spontaneous) mental time travel into the past and future. Consciousness and Cognition: An International Journal, 17, 1093–1104.

Berntsen, D., & Rubin, D. C. (2006). The centrality of event scale: A measure of integrating a trauma into one’s identity and its relation to post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 219–231.

Berntsen, D., Rubin, D. C., & Salgado, S. (2015). The frequency of involuntary autobiographical memories and future thoughts in relation to daydreaming, emotional distress, and age. Consciousness and Cognition: An International Journal, 36, 352–372.

Berntsen, D., & Watson, L. (2014). Involuntary autobiographical memories in daily life and in clinical disorders. In T. Perfect & D. Lindsay (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of applied memory (pp. 501–520). London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498.

Brummer, L., Stopa, L., & Bucks, R. (2014). The influence of age on emotion regulation strategies and psychological distress. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 42, 668–681.

Campbell-Sills, L., Barlow, D. H., Brown, T. A., & Hofmann, S. G. (2006). Acceptability and suppression of negative emotion in anxiety and mood disorders. Emotion, 6, 587–595.

Christensen, S., Zachariae, R., Jensen, A. B., Væth, M., Møller, S., Ravnsbæk, J., & von der Maase, H. (2009). Prevalence and risk of depressive symptoms 3–4 months post-surgery in a nationwide cohort study of Danish women treated for early stage breast-cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 113, 339–355.

Crovitz, H. F., & Schiffman, H. (1974). Frequency of episodic memories as a function of their age. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 4, 517–518.

De Lissnyder, E., Koster, E. H. W., Derakshan, N., & De Raedt, R. (2010). The association between depressive symptoms and executive control impairments in response to emotional and non-emotional information. Cognition and Emotion, 24, 264–280.

Del Palacio-Gonzalez, A. & Berntsen, D. (2017). Brooding over Events Central to Identity Predicts Concurrent and Prospective Depressive Symptoms. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Ehring, T., Fischer, S., Schnülle, J., Bösterling, A., & Tuschen-Caffier, B. (2008). Characteristics of emotion regulation in recovered depressed versus never depressed individuals. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 1574–1584.

Ekman, P. (1992). Are there basic emotions? Psychological Review, 99, 550–553.

Ericsson, K. A., & Simon, H. A. (1980). Verbal reports as data. Psychological Review, 87, 215–251.

Finnbogadottir, H., & Berntsen, D. (2011). Involuntary and voluntary mental time travel in high and low worriers. Memory, 19, 625–640.

Gross, J. J. (1998). Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 224–237.

Gross, J. J., & Barrett, L. F. (2011). Emotion generation and emotion regulation: One or two depends on your point of view. Emotion Review, 3, 8–16.

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 348–362.

Harris, C. B., Rasmussen, A. S., & Berntsen, D. (2014). The functions of autobiographical memory: An integrative approach. Memory, 22, 559–581.

Hesse, M. (2006). The Beck Depression Inventory in patients undergoing opiate agonist maintenance treatment. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45, 417–426.

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Fang, A., & Asnaani, A. (2012). Emotion dysregulation model of mood and anxiety disorders. Depression and Anxiety, 29, 409–416.

Huprich, S. K., & Roberts, C. R. D. (2012). The two-week and five-week dependability and stability of the depressive personality disorder inventory and its association with current depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality Assessment, 94, 205–209.

St. Jacques, P, L., Conway, M, A., &, Cabeza, R (2011). Gender differences in autobiographical memory for everyday events: Retrieval elicited by SenseCam images versus verbal cues. Memory, 19, 723–732.

Johannessen, K. B., & Berntsen, D. (2010). Current Concerns in involuntary and voluntary autobiographical memories. Consciousness and Cognition, 19, 847–860.

Joormann, J., & D’Avanzato, C. (2010). Emotion regulation in depression: Examining the role of cognitive processes. Cognition and Emotion, 24, 913–939.

Karreman, A., van Assen, Marcel A. L. M., & Bekker, M. H. J. (2013). Intensity of positive and negative emotions: Explaining the association between personality and depressive symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences, 54, 214–220.

Kvavilashvili, L., & Schlagman, S. (2011). Involuntary autobiographical memories in dysphoric mood: A laboratory study. Memory, 19, 331–345.

Labouvie-Vief, G., Lumley, M. A., Jain, E., & Heinze, H. (2003). Age and gender differences in cardiac reactivity and subjective emotion responses to emotional autobiographical memories. Emotion, 3, 115–126.

Mace, J. H. (2004). Involuntary autobiographical memories are highly dependent on abstract cuing: The proustian view is incorrect. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 18, 893–899.

MacLeod, C., & Bucks, R. S. (2011). Emotion regulation and the cognitive-experimental approach to emotional dysfunction. Emotion Review, 3, 62–73.

Mennin, D. S., Holaway, R. M., Fresco, D. M., Moore, M. T., & Heimberg, R. G. (2007). Delineating components of emotion and its dysregulation in anxiety and mood psychopathology. Behavior Therapy, 38, 284–302.

Newby, J. M., & Moulds, M. L. (2010). Negative intrusive memories in depression: The role of maladaptive appraisals and safety behaviours. Journal of Affective Disorders, 126, 147–154.

Newby, J. M., & Moulds, M. L. (2012). A comparison of the content, themes, and features of intrusive memories and rumination in major depressive disorder. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51, 197–205.

Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review, 84, 231–259.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 115–121.

Perneger, T. V. (1998). What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. British Medical Journal, 316, 1236–1238.

Philippe, F. L., Koestner, R., Lecours, S., Beaulieu-Pelletier, G., & Bois, K. (2011). The role of autobiographical memory networks in the experience of negative emotions: How our remembered past elicits our current feelings. Emotion, 11, 1279–1290.

Plimpton, B., Patel, P., & Kvavilashvili, L. (2015). Role of triggers and dysphoria in mind-wandering about past, present and future: A laboratory study. Consciousness and Cognition, 33, 261–276.

Rasmussen, A. S., & Berntsen, D. (2010). Personality traits and autobiographical memory: Openness is positively related to the experience and usage of recollections. Memory, 18, 774–786.

Rasmussen, A. S., & Berntsen, D. (2011). The unpredictable past: Spontaneous autobiographical memories outnumber memories retrieved strategically. Consciousness and Cognition, 20, 1842–1846.

Rasmussen, A. S., Johannessen, K. B., & Berntsen, D. (2014). Ways of sampling voluntary and involuntary autobiographical memories in daily life. Consciousness and Cognition, 30, 156–168.

Reynolds, M., & Brewin, C. R. (1998). Intrusive cognitions, coping strategies and emotional responses in depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and a non-clinical population. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36, 135–147.

Rottenberg, J., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Emotion and emotion regulation: A map for psychotherapy researchers. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 14, 323–328.

Rottenberg, J., Joormann, J., Brozovich, F., & Gotlib, I. H. (2005). Emotional intensity of idiographic sad memories in depression predicts symptom levels 1 year later. Emotion, 5, 238–242.

Rubin, D. C., Boals, A., & Berntsen, D. (2008). Memory in posttraumatic stress disorder: Properties of voluntary and involuntary, traumatic and nontraumatic autobiographical memories in people with and without posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 137, 591–614.

Rubin, D. C., Dennis, M. F., & Beckham, J. C. (2011). Autobiographical memory for stressful events: The role of autobiographical memory in posttraumatic stress disorder. Consciousness and Cognition, 20, 840–856.

Schlagman, S., Kliegel, M., Schulz, J., & Kvavilashvili, L. (2009). Differential effects of age on involuntary and voluntary autobiographical memory. Psychology and Aging, 24, 397–411.

Schlagman, S., & Kvavilashvili, L. (2008). Involuntary autobiographical memories in and outside the laboratory: How different are they from voluntary autobiographical memories? Memory & Cognition, 36, 920–932.

Sprinkle, S. D., Lurie, D., Insko, S. L., Atkinson, G., Jones, G. L., Logan, A. R., & Bissada, N. N. (2002). Criterion validity, severity cut scores, and test-retest reliability of the beck depression inventory-II in a university counseling center sample. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 49, 381–385.

Walker, W. R., Skowronski, J. J., Gibbons, J. A., Vogl, R. J., & Thompson, C. P. (2003). On the emotions that accompany autobiographical memories: Dysphoria disrupts the fading affect bias. Cognition and Emotion, 17, 703–723.

Watson, L. A., Berntsen, D., Kuyken, W., & Watkins, E. R. (2012). The characteristics of involuntary and voluntary autobiographical memories in depressed and never depressed individuals. Consciousness and Cognition: An International Journal, 21, 1382–1392.

Watson, L. A., Berntsen, D., Kuyken, W., & Watkins, E. R. (2013). Involuntary and voluntary autobiographical memory specificity as a function of depression. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 44, 7–13.

Wegner, D. M., & Zanakos, S. (1994). Chronic thought suppression. Journal of Personality, 62, 615–640.

Whitmer, A., & Gotlib, I. H. (2011). Brooding and reflection reconsidered: A factor analytic examination of rumination in currently depressed, formerly depressed, and never depressed individuals. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 35, 99–107.

Williams, A. D., & Moulds, M. L. (2007). An investigation of the cognitive and experiential features of intrusive memories in depression. Memory, 15, 912–920.

Zimmermann, P., & Iwanski, A. (2014). Emotion regulation from early adolescence to emerging adulthood and middle adulthood: Age differences, gender differences, and emotion-specific developmental variations. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 38, 182–194.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Maike Bohn, Anne Sofie Jakobsen, and Tanne Hundahl for their assistance in data collection and data entry. We also thank Ole Karkov Østergård and Studenterrådgivningen (Aarhus) for their help with recruiting participants. The authors were supported by the Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF) under Grant DNRF89 for conducting this study. The DNRF had no involvement in the design or the interpretation of the results of the current study. All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Adriana del Palacio-Gonzalez, Dorthe Berntsen and Lynn A. Watson declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

del Palacio-Gonzalez, A., Berntsen, D. & Watson, L.A. Emotional Intensity and Emotion Regulation in Response to Autobiographical Memories During Dysphoria. Cogn Ther Res 41, 530–542 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-017-9841-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-017-9841-1