Abstract

The tendency to engage in depressive rumination is typically measured with the Ruminative Response Styles (RRS) scale. Treynor et al. (2003) reported that this scale is composed of two 5-item factors, reflection and brooding, and that the brooding but not the reflection factor is associated with more severe depression over time. These two factors were derived using data from a randomly selected community sample, and it is not clear if these factors would be obtained in samples of currently depressed, formerly depressed, and never depressed individuals. We conducted factor analyses on scores on the RRS scale from three such samples. We found support for the distinction between reflection and brooding in never depressed and formerly depressed individuals; we did not obtain this distinct factor structure in the currently depressed sample. We did, however, find evidence of a second factor in the depressed sample that we labeled ‘intentional rumination.’ The results of this study also suggested that an item from the reflection factor should be replaced with another item from the RRS scale. These findings indicate that the distinction between brooding and reflection is blurred in currently depressed individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Depressive rumination is defined as repetitive thinking about the causes, symptoms, and implications of one’s sad mood, dysphoria or depression. Individuals who tend to ruminate have been found to experience more severe depressive symptoms, more episodes of clinical depression, more severe depressive episodes, and a slower recovery from depression than have nonruminators (see Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008). Most research examining the relation between ruminative tendency and depression has used the Ruminative Response Styles (RRS) scale (Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow 1991) to assess rumination. Findings of these studies suggest that the tendency to ruminate is trait-like, remaining stable over extended periods despite fluctuations in mood (see Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008).

Although the full version of the RRS scale was used for many years, it was often criticized for containing items that overlapped with items on scales measuring depressive symptomology (e.g., Conway et al. 2000; Roberts et al. 1998; Segerstrom et al. 2000). Consequently, Treynor et al. (2003) revised the scale; after eliminating items that overlapped significantly with symptoms of depression, they obtained scores on a 10-item version of the RRS scale from a large, randomly selected community sample (n = 1,328) and conducted a factor analysis to examine whether this shortened version of the RRS scale measured distinct subtypes of rumination. They found that the RRS scale assesses two types of rumination (each measured with five items), which they labeled brooding and reflection. Treynor et al. defined brooding as passive and judgmental pondering of one’s mood, and reflection as contemplative, intentional pondering of one’s mood with a focus on problem solving.

A critical finding of Treynor et al.’s (2003) study was that only the brooding factor was maladaptive. Specifically, higher scores on the brooding factor were related to higher levels of depressive symptoms and also predicted increases in depressive symptoms 1 year later. In contrast, even though reflection was also associated positively with concurrent symptoms of depression, it predicted lower levels of depression over time. Investigators have since depended on this distinction to explore factors that might affect the maladaptive nature of rumination. Indeed, over the past 7 years, almost 200 papers have referred to the brooding-reflection distinction of the RRS scale, and most have analyzed these two factors separately.

Given that Treynor et al. (2003) used a randomly selected community sample, their findings should generalize to a “normal” population. Investigators examining rumination, however, often assess brooding and reflection in such samples as individuals diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), formerly depressed individuals, and never depressed individuals (sometimes used as a control group); it is not clear if the factors of brooding and reflection would be obtained in factor analyses of data from these specific, “non-normal,” groups of participants. Indeed, some investigators have suggested that in individuals with MDD, brooding and reflection will exacerbate each other until it is difficult to distinguish between these two factors (e.g., Joormann et al. 2006).

The present study was designed to examine whether a factor analysis of scores on the RRS scale in currently, formerly, and never depressed individuals would yield the two factors of brooding and reflection. We hypothesized that we would replicate the factor structure of the RRS scale in the never depressed group, obtaining brooding and reflection factors in these participants. We hypothesized further, however, that brooding and reflection would not be clearly distinguished in the MDD group. Finally, we examined the factor structure of the RRS scale in the formerly depressed group to address the question of whether the potential lack of a clear distinction between brooding and reflection in the MDD group is a function of the “state” of depression (i.e., the two factors are found in both the never depressed and formerly depressed groups), or alternatively, is related to a vulnerability to depression (i.e., the two factors are obtained only in the never depressed group).

Method

Participants

All participants were adults recruited from the same communities as the participants in Treynor et al.’s (2003) study: Oakland, San Francisco, and San Jose, California. Participants were recruited through advertisements posted in numerous locations (e.g., internet bulletin boards, university kiosks, supermarkets, etc.). The Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID; First et al. 1995) was administered to all participants to assess current and lifetime diagnoses for anxiety, mood, psychotic, alcohol and substance use, somatoform, and eating disorders. The SCID has good reliability (e.g., Skre et al. 1991), and our team of trained interviewers has established excellent interrater reliability with this interview (κ = 0.92; e.g., Gotlib et al. 2004; Levens and Gotlib 2010). Participants who met DSM-IV criteria for MDD were included in the currently depressed group; participants with no current or past Axis I disorder were included in the never depressed group, and participants who met criteria for at least one episode of MDD in their lifetimes, but who were not diagnosable with MDD at the time of completing the RRS scale, were included in the formerly depressed group.

The MDD group consisted of 353 participants, the never depressed group of 377 participants, and the formerly depressed group of 70 participants. Whereas the sample sizes for the MDD and never depressed groups are above standard guidelines for conducting factor analyses, the ratio of sample size to items in the formerly depressed group is smaller but similar to that used in many other studies (e.g., Costello and Osborne 2005; Fabrigar et al. 1999)

Measures

Rumination

The RRS scale is a subscale of the 71-item Response Styles Questionnaire (RSQ; Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 1993). The RSQ measures individuals’ tendencies to ruminate (the RRS scale) and to self-distract when in a sad or depressed mood. A subset of the present sample (178 currently depressed, 251 never depressed, and 45 formerly depressed participants) completed the RRS scale items as part of completing the larger RSQ. Because we decided in our laboratory to focus on rumination, and not on distraction, the remaining 175 MDD, 126 never depressed, and 25 formerly depressed participants completed only the 25-item RRS subscale of the RSQ. We should note that Treynor et al. (2003) used a 22-item version of the RRS scale, and Bagby et al. (2004) used a 21-item version; it is not clear why there are different versions of the full RRS scale. Importantly, however, all of the participants in the present study completed the same 10 RRS scale items that were used by Treynor et al. (see Table 2 for these items). All participants were presented with the following instructions for completing the RRS scale:

People think and do many different things when they feel depressed. Please read each of the following items and indicate whether you almost never, sometimes, often, or almost always think or do each one when you feel down, sad, or depressed. Please indicate what you generally do, not what you think you should do.

Depressive Symptomatology

Participants in all three groups completed the 21-item Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI; Beck et al. 1996) assessing the severity of their depressive symptoms. Over the past several decades the BDI has been found to have high reliability and validity (e.g., Beck et al. 1996).

Results

Participant Characteristics

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. The three groups of participants did not differ significantly in the proportion of males and females, χ2(2) = 3.689, P = 0.158. The groups did differ, however, in age, F(2,723) = 8.801, ∂ = 0.024, P < 0.0001, and in BDI scores, F(2,770) = 1302.68, ∂ = 0.772, P < 0.0001. Follow-up tests indicated that the MDD participants were older than the never depressed participants, t(723) = 4.191, P < 0.0001, but not the formerly depressed participants, t(723) = 1.117, P = 0.264, who did not differ significantly from each other, t(723) = 1.403, P = 0.161. As expected, the currently depressed participants had significantly higher BDI scores than did the formerly depressed participants, t(770) = 25.822, P < 0.0001, who in turn had higher BDI scores than did the never depressed participants, t(770) = 3.773, P < 0.0001.

Factor Analyses

Treynor et al. (2003) conducted a principal components analysis with an orthogonal (varimax) rotation. These methods of factor extraction, once standard because of limited computational power, are now considered to be inappropriate for many purposes. A principal component analysis is appropriate for data reduction, but not for identifying latent variables (e.g., Costello and Osborne 2005; Fabrigar et al. 1999), which is the goal of the present study. The orthogonal rotation used by Treynor et al. also assumes that the extracted factors do not correlate, even though both theory and data suggest that subtypes of rumination are indeed intercorrelated. Because it is not clear that the factor structure was correctly defined in Treynor et al.’s study, we proceeded with exploratory instead of confirmatory factor analyses in the present study. Thus, we conducted exploratory factors analyses with maximum likelihood extraction and an oblique rotation (direct oblimin). Investigators typically use a factor loading cut-off between 0.3 and 0.4 to construct factors. Consistent with Fabrigar et al.’s (1999) recommendation, we used a factor loading of 0.3. This value is considered to be the minimum needed for a variable to have practical significance (e.g., Hair et al. 1998).

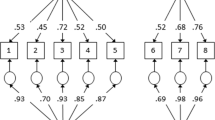

The factor analysis of the data from the control group replicated Treynor et al.’s (2003) findings. A parallel analysis (Horn 1965), considered to be superior to the scree test and the Kaiser criterion (Fabrigar et al. 1999; O’Conner 2000) used by Treynor et al. (2003), was used to determine the number of factors to extract. This analysis indicated retaining two factors. All five “reflection” items loaded on the first factor and all five “brooding” items loaded on the second factor (see Table 2). The eigenvalues for the factors were 3.713 and 1.562, respectively, together accounting for 52.753% of the variance. The correlation between these factors was 0.436. These values are strikingly similar to those obtained by Treynor et al., who found their reflection and brooding factors to have eigenvalues of 3.41 and 1.64, respectively, and to account for 50.5% of the variance (see Table 2 for factor loadings). Thus, these findings suggest that in never depressed participants, the RRS scale is composed of reflection and brooding factors.

In contrast, the factor analysis of the data from the MDD participants did not replicate Treynor et al.’s (2003) results. A parallel analysis again suggested a two-factor model, but the items did not separate into reflection and brooding factors as they did in the never depressed group (see Table 2). In particular, the item, “write down what you are thinking and analyze it,” from Treynor et al.’s reflection subscale had poor initial communality with the other items (0.131) and did not load on either factor. In addition, two other “reflection” items loaded most strongly on the factor containing the five “brooding” items, with the factor structure suggesting that these two items also cross-loaded on the other factor. The correlation between the two factors was 0.482. In sum, these findings suggest that the distinction between reflection and brooding is blurred in individuals with MDD.

The factor analysis conducted on the RRS scale scores of the formerly depressed participants yielded evidence of reflection and brooding factors similar to those obtained in the never depressed group and in the unselected community sample assessed by Treynor et al. (2003). A parallel analysis again indicated that two factors should be extracted. All five “brooding” items loaded on the first factor and four of the five “reflection” items loaded on the second factor (see Table 2). The eigenvalues for the factors were 3.567 and 2.159, respectively, and together accounted for 57.266% of the variance. The correlation between the two factors was 0.193. As was the case for the MDD sample, the single item that did not load on either factor was “write down what you are thinking and analyze it,” which also had a low initial communality of 0.111 in this sample.

Replacing the “Write down what you are thinking and analyze it” Item

Overall, the results of these three factor analyses suggest that the item, “write down what you are thinking and analyze it,” should be eliminated from the RRS scale. It had extremely small initial communality in the MDD, formerly, and never depressed groups (0.131, 0.111, 0.218, respectively), suggesting that it does not measure the same latent variable as the other items do; moreover, it did not load on either factor in the MDD or formerly depressed groups. Consequently, we examined whether this item could be replaced with a psychometrically stronger item from the larger RRS scale. A stronger item should have a larger initial communality and should load on one of the two factors in all three samples.

We replaced the “write down” item with the item, “isolate yourself and think about the reasons why you feel sad.” Treynor et al. (2003) used a 22-item version of the RRS scale that did not include this item; therefore, this item was not one of the items excluded from their study as being confounded with depressive symptoms. We chose this item as a substitute because it is similar to the two items that loaded on factor two in the MDD group and, if it loaded with these two items, it would increase the number of items loading on this factor to the minimum of three recommended by Costello and Osborne (2005). This item was also similar to the items that load on the reflection factor in the never depressed and formerly depressed groups and, therefore, may be an acceptable substitute for the “write down” item. Finally, this item does not appear to be confounded with depressive symptoms to any greater extent than are the other items included by Treynor et al.

After replacing the “write down” item with the “isolate yourself” item, we again conducted factor analyses and found support for a two-factor model in both the never depressed and formerly depressed groups. In the never depressed group, the item, “isolate yourself,” loaded on the reflection factor and the remaining items loaded on the brooding factor (see Table 2). The eigenvalues were 3.882 and 1.585, respectively, and accounted for 54.671% of the variance. The communality of the item, “isolate yourself,” was 0.474 (compared to 0.218 of the item, “write down”), and the alpha coefficient of the reflection factor including this item was 0.838 (compared to 0.816 with the “write down” item). The alpha coefficient of the brooding factor in the present study was 0.694, compared with 0.77 in Treynor et al.’s (2003) study. The correlation between these two factors was 0.437.

In the formerly depressed group, the “isolate yourself” item also loaded on the reflection factor (see Table 2). The eigenvalues for the brooding and reflection factors were 3.932 and 2.277, respectively, and accounted for 62.09% of the variance. The communality of the “isolate yourself” item was 0.589 (compared to 0.127 of the “write down” item), and the alpha coefficient of the reflection factor was 0.804 (compared to 0.709 with the “write down” item). The alpha coefficient of the brooding factor was 0.868. The correlation between these two factors was 0.291. In sum, the item, “isolate yourself” has good communality (unlike the item, “write down,”) and loads on factors in both the formerly depressed and never depressed groups. These findings suggest that the item, “isolate yourself,” is a psychometrically strong substitute for the item, “write down,” in both these groups.

In the MDD group, the factor analysis including the “isolate yourself” item yielded a similar result as the analysis with the “write down” item, with the exceptions that the “isolate yourself” item loaded with the “go away” and “go someplace” items on factor 2. As before, two items from the “reflection” subscale cross-loaded on both factors, with the loadings being stronger on the factor that contains the brooding items. The eigenvalues for factors 1 and 2 were 4.000 and 1.393, respectively, and together accounted for 53.928% of the variance. The “isolate yourself” item also had a better communality with the other items (0.323) than did the “write down” item. The correlation between these two factors was 0.482. Thus, as was the case for the formerly depressed and never depressed groups, the “isolate yourself” item is psychometrically stronger than the “write down” item in the MDD group.

The finding that the two “analyze” items from the reflection subscale cross-loaded on both factors supports the hypothesis that the distinction between reflection and brooding is blurred in depressed individuals. Because statisticians recommend removing cross-loading items (e.g., Costello and Osborne 2005; Ferguson and Cox 1993), we removed these two items from further analysis. Thus, we labeled factor 1 brooding because it contains only the same five brooding items found in the nondepressed groups. In contrast, only three items cleanly loaded on factor 2 (only two items from Treynor et al.’s 2003, “reflection” subscale”); given that these three items measure a tendency to self-isolate with the intention to ruminate, we call this factor ‘intentional rumination.’ The alpha coefficient of the brooding factor was 0.760, and the alpha coefficient of the intentional reflection factor was 0.757.

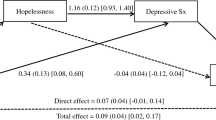

Finally, we examined the relation between BDI scores and the factors obtained in the three groups of participants. In the MDD group, depressive severity, as measured with the BDI, was associated with both brooding, r(330) = 0.470, P < 0.0001, and intentional rumination, r(330) = 0.121, P = 0.022. However, brooding was more strongly associated with depressive severity than was intentional rumination, t(330) = 6.71, P < 0.001. In addition, regressing both brooding and intentional rumination on depressive severity in the same model left only general rumination significantly associated with depressive severity, suggesting that the variance unique to intentional rumination is not related to depressed mood. In the formerly depressed group, higher BDI scores were positively related to higher scores on the brooding factor, r(67) = 0.256, P = 0.04, but not on the reflection factor (i.e., the average of 5 items, including the “isolate yourself” item), r(67) = 0.084, P = 0.497. In the control group, higher BDI scores were related to higher scores on both the reflection factor (the average of 5 items including the “isolate yourself” item), r(364) = 0.12, P = 0.022, and the brooding factor, r(364) = 0.34, P < 0.0001. The brooding factor was more strongly associated with BDI scores was than the reflection factor, t(365) = 4.25, P < 0.001. In both the formerly depressed and the never depressed groups, regressing both factors on depressive severity in the same model left only the brooding factor significantly associated with depressive severity, suggesting that the variance unique to the reflection factor is not related to current depressed mood.

Discussion

Treynor et al.’s (2003) identification of brooding and reflection components of the RRS scale in a randomly selected community sample has had a significant influence on research focused on rumination. It is unclear, however, whether these components would also be found in other populations, such as individuals who are currently depressed, who were formerly depressed, or have never been depressed. The present results support the distinction between brooding and reflection in never depressed and in formerly depressed individuals, with the exception that the “write down what you are thinking and analyze it” item from the reflection subscale did not load on either factor in the formerly depressed group. A two-factor solution was also found in the MDD group, but it did not support a distinction between brooding and reflection. Instead, two “reflection” items cross-loaded on both factors, with larger loadings on the factor with the “brooding” items. In this sample, the “write down” item did not load on either factor. Thus, only two of the five items from Treynor et al.’s reflection scale cleanly loaded on a separate factor, and two ‘reflection’ items loaded with the brooding items. These findings suggest that brooding and reflection are distinct in individuals who are not currently depressed (i.e., never depressed and formerly depressed persons), but not in individuals who are currently depressed (i.e., the MDD group).

The pattern of findings obtained in this study suggests that the “state” of depression, and not a vulnerability to the disorder, is associated with the blurring of reflection and brooding. It appears, therefore, that in individuals who are not in a depressed state, brooding and reflection may occur independently, and brooding may still be a unique predictor of increases in depression over time, as found by Treynor et al. (2003). Once an individual becomes depressed, however, brooding and reflection, and in particular, the self-analytical style measured by the two cross-loading items, may exacerbate each other, making it difficult to distinguish between these two constructs. It is possible that this self-analytical style of rumination will also become more maladaptive, like brooding, as an individual becomes more depressed. These findings suggest that investigators should not use the RRS reflection subscale in clinically depressed samples and, further, that findings from the reflection subscale in nonclinical samples may not generalize to clinical populations.

The present results also suggest that the item, “write down what you are thinking and analyze it,” should be eliminated from the short version of the RRS scale and replaced with the item, “isolate yourself and think about the reasons why you feel sad.” The “write down” item had extremely small communality with the other items in all three groups and did not load on either factor in the formerly depressed and MDD groups. This finding may not be surprising, given that only a small subset of individuals who ruminate are likely to write about their ruminations. In contrast, the “isolate yourself” item had better initial communality in all three groups and loaded on a factor with “reflection” items in all three groups. Moreover, this item loaded with the two items forming the intentional rumination factor in the MDD group, increasing the strength and stability of this factor (Costello and Osborne 2005).

The intentional rumination factor appears to be distinct from the reflection factor found by Treynor et al. (2003), in that it only contains two of the original five items. After replacing the “write down” item with the “isolate yourself” item, three items loaded on this factor, all measure the tendency to self-isolate with the intention to rumination. Although we labeled this factor “intentional rumination,” it is not clear whether it is the self-isolation associated with the rumination or the intentionality or purposefulness of the rumination that makes this form of rumination distinct from that measured by the brooding factor. Unfortunately, because the items of the RRS scale were not designed to examine this distinction, it is difficult to draw strong conclusions concerning these explanations.

Nevertheless, these two accounts make distinct and testable predictions about mood. If this factor primarily represents a normal form of rumination with the exception that it occurs in isolation, then it should be associated with a higher level of depressed mood than the rumination measured by the brooding factor, given that isolation will decrease opportunities to engage in rewarding activity and to be distracted from rumination, which should lead to more severe levels of depressive symptoms (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008). Similarly, if this factor reflects an intentional and purposeful form of rumination, then it may be associated with less severe depressed mood than is the brooding factor, given that intentional rumination may represent a purposeful attempt to engage in problem solving about one’s mood and, thereby, lead to stronger insights about one’s problems than would passive repetition of sad thoughts (Treynor et al. 2003). Intentional rumination may also be less distressing than are more automatic forms of rumination because it is less intrusive. The present data support an intentional rumination interpretation of this factor. This factor was related to significantly lower severity of depression than the brooding factor. Therefore, we think the name of this factor, intentional rumination, is acceptable for now. Further research is required, however, to examine more systematically whether there might be a more appropriate label for this factor.

Intentional rumination was only weakly related to severity of depression in the MDD group; indeed, controlling for scores on the brooding factor rendered nonsignificant the correlation between intentional rumination and depression severity. This finding suggests that intentional rumination is not as maladaptive as the form of rumination measured by the brooding factor. Prospective research is needed, however, to examine whether intentional rumination predicts a decrease in depressive symptoms and, therefore, could be an adaptive form of rumination. Future research might also examine reasons why intentional rumination appears to be more adaptive than brooding. For example, although Nolen-Hoeksema’s Response Styles Theory postulates that rumination does not typically lead to constructive problem solving (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008), it is possible that intentionally engaging in a period of rumination about one’s problems will lead to improved problem solving.

The results of this study suggest that brooding is a more stable subscale than is reflection because all five items of this scale load together in all three groups. However, again, caution should be taken before assuming that “brooding” in nondepressed individuals is the same as “brooding” in depressed individuals. Two “reflection” items actually loaded more strongly with the “brooding” items than with the other “reflection” items in the depressed group. Therefore, it is possible that the latent variable measured by the “brooding” items also changes when individuals become depressed.

Treynor et al. (2003) concluded that the brooding factor is maladaptive and the reflection factor, adaptive. Importantly, however, this finding has not been corroborated consistently in subsequent research (e.g., Johnson et al. 2008; Surrence et al. 2009). For example, Miranda and Nolen-Hoeksema (2007) found that both brooding and reflection predicted increased suicidal ideation at a one-year follow up in a large, unselected community sample, even when controlling for baseline suicide ideation. The present results may explain some of these equivocal findings. For example, only the more severely depressed individuals in Miranda and Nolen-Hoeksema’s unselected sample are likely to exhibit suicide ideation, and the present study suggests that in depressed individuals, some of the items in the reflection scale measure a similar form of rumination as the items in the brooding subscale. Therefore, the overlap of reflection items with brooding items may account for its association with suicide ideation; Miranda and Nolen-Hoeksema may not have found this association if they had examined scores on the intentional rumination subscale instead of on the reflection subscale.

The present results may also explain why some studies have found a relation between specific dependent variables and brooding but not reflection (e.g., Jones et al. 2008; Joormann et al. 2006). Null results may have been obtained with the reflection subscale because the items in this scale are not stable markers of a latent variable. Indeed, two of the five items do not load reliably on only one latent variable as depressed mood fluctuates, and one item that was included in the reflection subscale has little in common with the other items in the subscale. In contrast, all five items from the brooding subscale load together on the same factor in all groups. Thus, investigators may wish to reconsider whether such null results are veridical or, instead, if they are due to noise in the reflection subscale.

One potential limitation to this study is that the ratio of sample size to items in the formerly depressed sample is small (7 to 1). Nevertheless, a ratio of this size is common in studies using factor analysis (Costello and Osborne 2005), and the factor analyses on this sample yielded clear results, suggesting that the findings are reliable. Future research, however, should be conducted to confirm the factor structure in the formerly depressed group.

Future research is also needed to examine several other issues raised in the present study. The number of items that load on the intentional rumination factor should be increased to at least five so that this factor can be compared with the brooding factor. In the meantime, we suggest that researchers both continue to report the average of all 10 RRS items and, when examining the subscales, report scores from the three-item intentional rumination subscale separately from the two “analyze” items even in nondepressed groups in order to compare scores on this subscale across groups. Researchers should also be aware that the intentional rumination scale is less reliable than the brooding scale because it contains fewer items. It is not yet clear why the two “analyze” items loaded cleanly with the reflection items in nondepressed samples but cross-loaded with brooding items in a depressed sample. Although we eliminated these items from further analysis, they are clearly of theoretical importance. Future research should examine how this analytical form of rumination changes and becomes more like the rumination measured by the brooding items when individuals become clinically depressed. The change may indicate ways in which rumination can become more maladaptive when a person becomes depressed. For example, Kwon and Olson (2007) noted that reflection might be adaptive only if it is reality-based and constructive. It is possible that when individuals become depressed, increased negative biases make self-analysis less constructive and realistic and, therefore, as maladaptive as the type of rumination measured by the Brooding items. Future research should also examine whether these “analyze” items cross-load in dysphoric participants, a population frequently examined by researchers interested in rumination.

In summary, we found support for a distinction between brooding and reflection in two groups of currently nondepressed individuals, but not in a group of individuals diagnosed with MDD. Our results also suggest that the “write down” item from the original short version of the RRS scale should be replaced with the “isolate yourself” item. This item loads with the four other reflection items in the nondepressed groups, and with two other items in the depressed group to create a new subscale we labeled “intentional rumination.” Given the stability of this subscale across groups in the present study, future research might profitably focus on further elucidating its characteristics.

References

Bagby, R. M., Rector, N. A., Bacchiochi, J. R., & McBride, C. (2004). The stability of the response styles questionnaire rumination scale in a sample of patients with major depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 28, 527–538.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory - II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Conway, M., Csank, P. A. R., Holm, S. L., & Blake, C. K. (2000). On individual differences in rumination on sadness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 75, 404–425.

Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. W. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment Research and Evaluation, 10(7), 1–9.

Fabrigar, L. R., Wegener, D. T., MacCallum, R. C., & Strahan, E. J. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 4(3), 272–299.

Ferguson, E., & Cox, T. (1993). Exploratory factor analysis: A user’s guide. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 1, 84–94.

First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M., & Williams, J. B. W. (1995). The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IIIR Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Part I: Description. Journal of Personality Disorders, 9, 83–91.

Gotlib, I. H., Krasnoperova, E., Neubauer, D. L., & Joormann, J. (2004). Attentional biases for negative interpersonal stimuli in clinical depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113, 127–135.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Horn, J. L. (1965). A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 30, 179–185.

Johnson, S. L., McKenzie, G., & McMurrich, S. (2008). Ruminative responses to negative and positive affect among students diagnosed with bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32, 702–713.

Jones, N. P., Siegle, G. J., & Thase, M. E. (2008). Effects of rumination and initial severity on remission to cognitive therapy for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32, 591–604.

Joormann, J., Dkane, M., & Gotlib, I. H. (2006). Adaptive and maladaptive components of rumination? Diagnostic specificity and relation to cognitive biases. Behavior Therapy, 37, 269–280.

Kwon, P., & Olson, M. L. (2007). Rumination and depressive symptoms: Moderating role of defense style immaturity. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 715–724.

Levens, S., & Gotlib, I. H. (2010). Updating positive and negative stimuli in working memory in depression. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 139, 654–664.

Miranda, R., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2007). Brooding and reflection: Rumination predicts suicidal ideation at 1-year follow-up in a community sample. Behavior Research and Therapy, 45, 3088–3095.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 115–121.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Morrow, J., & Fredrickson, B. L. (1993). Response styles and the duration of episodes of depressed mood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102, 20–28.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 400–424.

O’Conner, B. P. (2000). SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and Velicer’s MAP test. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers, 3, 396–402.

Roberts, J. E., Gilboa, E., & Gotlib, I. H. (1998). Ruminative response style and vulnerability to episodes of dysphoria: Gender, neuroticism, and episode duration. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 22, 401–423.

Segerstrom, S. C., Tsao, J. C. I., Alden, L. E., & Craske, M. G. (2000). Worry and rumination: Repetitive thought as a concomitant and predictor of negative mood. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24, 671–688.

Skre, I., Onstad, S., Torgersen, S., & Kringlen, E. (1991). High interrater reliability for the structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R Axis I (SCID–I). Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 84, 167–173.

Surrence, K., Miranda, R., Marroquin, B. M., & Chan, S. (2009). Brooding and reflective rumination among suicide attempters: Cognitive vulnerability to suicidal ideation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47, 803–808.

Treynor, W., Gonzalez, R., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2003). Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27, 247–259.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Whitmer, A., Gotlib, I.H. Brooding and Reflection Reconsidered: A Factor Analytic Examination of Rumination in Currently Depressed, Formerly Depressed, and Never Depressed Individuals. Cogn Ther Res 35, 99–107 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-011-9361-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-011-9361-3