Abstract

Variation in the promoter region of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR) has been linked to various cognitive-affective indices of stress sensitivity hypothesized to underlie vulnerability to depression. The current study examined the association of 5-HTTLPR with appraisals of naturally occurring acute life stressors in a community sample of 384 youth at elevated risk for depression due to oversampling for maternal depression. Interview measures administered at youth age 20 were used to assess subjective and objective (assigned by an independent rating team) appraisals of the negative impact of recent acute stressful life events. The presence of at least one S allele was associated with elevated subjective appraisals of the negative impact of acute stressors (P = 0.03). Consistent with an endophenotype perspective, support was found for a 5-HTTLPR-stress appraisals-depression mediation model both concurrently and longitudinally. Results indicate that enhanced stress sensitivity may act as an intermediate phenotype through which 5-HTTLPR affects risk for depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

While the heritability of depression is supported by decades of family studies (Rice et al. 2002; Sullivan et al. 2000), the particular susceptibility genes contributing to depression liability are largely unknown. As for many other complex genetic disorders, replicable gene-disorder associations have proven to be disappointingly rare (Hamer 2002), and, as a result, there has been little consensus to date on the specific causal pathways mediating genetic risk for depression (Lau and Eley 2010).

The etiological complexity of depressive disorders is a key issue in the identification of disease-promoting genes. As with all multifactorial disorders, depression is the end product of a large number of genetic and environmental influences (Gotlib and Hammen 2008). In this context, only genetic association studies with many thousands of participants may be capable of detecting the small genetic signal attributable to any given polymorphism (Janssens and van Duijin 2008; Tabor et al. 2002).

Psychologists have begun to investigate cognitive and behavioral endophenotypes of depression as a means of magnifying theoretically important genetic effects that are empirically weak in magnitude (Hasler et al. 2004; Lau and Eley 2010). Stress sensitivity has emerged as a prominent depression endophenotype following a proliferation of studies implicating a polymorphism in the promoter region of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR) as a determinant of depressive reactivity to stressful contexts (Caspi et al. 2010; Uher and McGuffin 2010). Caspi et al. (2003) originally reported that individuals carrying at least one short (S) allele at 5-HTTLPR, relative to long (L) allele homozygotes, display elevated rates of depression in the face of stress. The robustness of this finding was questioned in a recent meta-analysis that found a negligible effect of 5-HTTLPR gene-environment interactions on depression risk (Risch et al. 2009). However, it has been observed that studies utilizing interview-based stress assessment procedures consistently report a positive association between the 5-HTTLPR S allele and depressive reactivity to stress (Monroe and Reid 2008; Uher and McGuffin 2010). In line with this behavioral evidence, seminal studies in the field of imaging genomics linked the 5-HTTLPR S allele to amygdala hyper-reactivity in response to emotional cues (Hariri et al. 2002, 2005) as well as impaired top–down control of activation in limbic regions by the prefrontal cortex (Heinz et al. 2005; Pezawas et al. 2005).

Similar associations have been established with more downstream (i.e., closer proximity to disorder), information-processing endophenotypes. Reporting results from an inpatient psychiatric sample, Beevers et al. (2007) showed that S allele carriers displayed selective allocation of attention to anxious words, relative to L allele homozygotes. In a group of healthy adults, these researchers found that S allele carriers also were slower to disengage attention from presentations of emotional facial expressions (Beevers et al. 2009). Similarly, in a non-clinical sample of young children, the S allele was associated with enhanced encoding of negative self-referent adjectives following a negative mood prime (Hayden et al. 2008). This evidence suggests that S allele carriers may be at heightened risk for depression as a result of exaggerated cognitive reactivity to stressful or emotional experiences (Hayden et al. 2008).

Building on this prior work, the current study examines an operationalization of stress sensitivity that has not been investigated previously in this literature: elevated appraisals of the negative impact of naturally occurring stressful life events. Subjective ratings of the negative impact of life stressors are consistently elevated among individuals with depression (e.g., Krackow and Rudolph 2008; Schless et al. 1974). Importantly, elevated appraisals of the stressfulness of acute events among depressed individuals are posited to reflect a dispositional vulnerability to the depressogenic effects of negative life events rather than an artifact of transient depressive states (Schless et al. 1974; Zimmerman 1983). Following existing research on cognitive-affective processing of threatening cues (e.g., Beevers et al. 2007; Hariri and Holmes 2006), we hypothesized that the presence of at least one S allele would predispose to higher ratings of the negative impact of stressful life events in a community sample of young adults at elevated risk for depression because they were oversampled for maternal history of depression.

One limitation of previous 5-HTTLPR endophenotype research is that no study has investigated whether intermediate traits on the causal chain from gene to disorder in fact statistically mediate the effect of 5-HTTLPR on depression outcomes. As a result, there remains no direct evidence to support the proposed causal pathway from 5-HTTLPR to depression via intermediate psychological systems. To provide such a test, we examined a mediation model wherein the influence of 5-HTTLPR on depression is transmitted through differential cognitive-affective sensitivity to stress. We hypothesized that S allele carriers, relative to L homozygotes, would report elevated ratings of the perceived negative impact of acute stressful life events, which would in turn be linked concurrently with increased rates of depressive symptoms and diagnoses and longitudinally with elevated depressive symptoms.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from the Mater-University Study of Pregnancy (MUSP) in Brisbane, Australia (Keeping et al. 1989), which followed a birth cohort of 7,223 mothers and their offspring born between 1981 and 1984 at the Mater Misericordiae Mother’s Hospital to study children’s health and development. Mothers were assessed for depression using the Delusions-Symptoms-States Inventory (DSSI; Bedford and Foulds 1978) during pregnancy, post-partum, 6 months after birth, and 5 years after birth. As described in detail elsewhere (Hammen and Brennan 2001), the present study selected and followed up 815 of the original families when the child reached age 15, oversampling for mothers with a putative history of depression based on the severity and chronicity of symptoms endorsed on the DSSI. Diagnoses of maternal depression were subsequently confirmed using structured clinical interviews, as described below. The sample studied at age 15 was 93% Caucasian and 7% minority (Asian, Pacific Islander, and Aboriginal), and median family income fell in the lower-middle class.Footnote 1 When youth reached age 20, all families were recontacted regarding participation in a second assessment, with 705 youth and mothers consenting to complete further interviews and questionnaires (see Keenan-Miller et al. 2007, for details).

Out of the 705 youth participating at the age 20 assessment, 512 provided DNA for genetic analyses between ages 22 and 25. Unavailable participants had either withdrawn from follow-ups, moved, could not be scheduled, had major medical problems, or were deceased. The 512 youth providing blood samples did not differ from the 193 participating at age 20 that did not provide blood with respect to youth depression history by age 20 or maternal history of depression by age 15, χ2 s < 1, Ps > 0.10, but were less likely to be male, χ2(1, 705) = 17.80, P < 0.01.

Current analyses were based on 384 randomly-selected DNA samples from the 512 youth who participated in the genotyping assessment. Due to economic and procedural constraints, only one 384-well genotyping plating was available. Three samples produced an invalid reading, resulting in a final sample of 149 males and 232 females, mean age 23.7 (SD = 0.89). The 381 youth genotyped for 5-HTTLPR did not differ from the 131 youth whose DNA samples were unanalyzed in terms of maternal depression status, χ2(1, 512) < 1, P > 0.10, although males were less likely to have their sample analyzed than females, χ2(1, 512) = 16.49, P < 0.01.

Procedure

When the youth turned 20, participants were interviewed and completed a battery of questionnaires in their homes. Two interviewers blind to the mother’s depression status conducted interviews with mothers and youth separately and independently. Youth were contacted in 2006 about participation in the genotyping study when they were between ages 22 and 25. The mean interval between assessments was 3.32 years (SD = 1.02). Participants who agreed to the blood collection study were mailed consent forms, a blood collection pack, and questionnaires, and were instructed to have the blood drawn at a local pathology lab. The blood samples were picked up by courier from the individual and transported to the Genetic Epidemiological Laboratory of the Queensland Institute of Medical Research, where the genotyping procedures were conducted. Procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Queensland; University of California, Los Angeles; and Emory University. Participants provided written informed consent and were compensated for their time.

Measures

Depression Symptoms and Diagnoses

Maternal diagnoses of major depression prior to offspring age 15 were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First et al. 1995) administered at youth age 15. Maternal depression up to youth age 15 was covaried in all analyses because it is a strong predictor of youth depression outcomes and new onsets of youth depression after age 15 are rarely associated with history of maternal depression by youth age 15 in the current sample (Hammen et al. 2008). Youth current depression diagnoses were also ascertained using the SCID at the age 20 follow up. At age 20, 30 (8%) youth were diagnosed as currently depressed. Based on ratings made by independent judges on recordings of 10% of the interviews, a kappa value of 0.83 was found for current depression, indicating adequate diagnostic reliability. Data on youth depression diagnoses after age 20 are not available.

Youth self-reported depressive symptoms at age 20 and ages 22–25 were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al. 1996), a continuous measure of the severity of depressive symptoms with excellent psychometric properties. In the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92 at both timepoints.

Neuroticism

Individual differences in neuroticism were assessed at the time of the blood sampling for genetic analyses using the 12-item short form of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire—Revised (EPQ-R; Eysenck and Eysenck 1975). This questionnaire has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties (Eysenck and Barrett 1985) and has been studied previously in the depression literature (e.g., Kendler et al. 2006). Internal consistency reliability in the current sample was 0.85.

Acute Stressful Life Events

At age 20, youth were administered a version of the UCLA Life Stress Interview (LSI) modified for adolescents (Hammen et al. 2000). Modeled after the contextual threat interview of George Brown and colleagues (Brown and Harris 1978), the LSI used standard general probes and follow-up queries to elicit specific life events occurring in the past 12 months. The number of acute events reported per participant ranged from 0 to 11 (M = 3.22, SD = 1.95). Fourteen participants reported no events in the past 12 months and were excluded from the present analyses. The interviewer established precise dating of each event and gathered information regarding the nature of the event and the circumstances surrounding its occurrence. Written narratives of each event were then presented to a rating team blind to youths’ actual responses to the event. For each event, the team then assigned a severity rating representing the impact this event would be expected to have on an average person in identical circumstances. Severity ratings ranged from 1 (no negative impact) to 5 (extremely severe negative impact). Reliability and validity data for the UCLA Life Stress Interview have been reported in other studies of adolescents and young adults (e.g., Hammen et al. 1995; Shih et al. 2006). In the present sample, the interrater reliability analyses for 89 cases yielded a kappa of 0.92 for severity ratings.

Appraisals of Acute Stressful Life Events

Immediately following the elicitation of an acute event during LSI administration, participants were asked to rate their perception of the negative impact associated with the stressor (“How would you rate the overall negative impact of this event?”). Participants provided a subjective severity rating ranging from 1 (no negative impact) to 5 (extremely severe negative impact). The test–retest reliability of the subjective ratings has previously been demonstrated to be adequate in a similarly-aged sample (Espejo et al. 2010).

Mean subjective and objective impact ratings were calculated for each participant. To compute an index of subjective perceptions of stressfulness that adjusts for differences in the objective severity of events, mean subjective rating scores were regressed on mean objective rating scores. The standardized residuals from this analysis constituted the dependent variable in the present analyses, with higher scores reflecting greater estimations of negative impact. This approach of calculating standardized residuals is an established method for comparing subjective and objective scores (e.g., Krackow and Rudolph 2008; Cole et al. 1998; De Los Reyes and Prinstein 2004).Footnote 2

Chronic Stress

Youth were administered the UCLA Chronic Stress Interview, which is a semi-structured interview probing ongoing problems from the past 12 months in a variety of domains (best friendships, intimate partner relations, relationships with family members, finances, health, academic performance). Each domain is then assigned a rating by the interviewer based on behaviorally specific anchors at each value. Ratings ranged from 1 (no stress; superior circumstances) to 5 (severe stress; major difficulties). Intraclass correlations based on ratings of independent interviewers ranged from 0.76 to 0.82. Validity data for the Chronic Stress Interview has been reported elsewhere (Hammen et al. 2008). The sum of chronic stress scores over the 1 year period prior to the age 20 interview was controlled statistically in all analyses to account for its potentially confounding effects on stress appraisals and depression outcomes.

Genotyping

The 43 bp deletion polymorphism was genotyped by agarose gel analysis of PCR products spanning the central portion of the repeats in the 5HTTLPR. PCR employed Qiagen enzyme and buffer except for the use of 30% deazaguanine and with ten cycles of Touchdown protocol beginning at 67°C and finishing at 62°C with a further 32 cycles. Samples were subject to independent duplicate PCR with primer set 1 (acgttggatgTCCTGCATCCCCCAT, acgttggatgGCAGGGGGGATACTGCGA, lower case sequence is non-templated) that gave products of 198 and 154 bp for Long and Short versions respectively and primer set 2 (acgttggatgTCCTGCATCCCCCAT, acgttggatgGGGGATGCTGGAAGGGC) for products of 127 and 83 bp (Wray et al. 2009). Most samples were subject to triplicate gel analysis. A minimum of two independent results in agreement was required for inclusion which gave a final call rate of 96.4%. To estimate accuracy duplicate samples were genotyped for 764 individuals in a different study using these procedures, with discordance rates of 0.45%. In the present sample the genotype frequencies were LL = 122, LS = 178, and SS = 81, and in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, χ2 (1, 381) = 1.61, P = 0.20.

The minor allele of the rs25531 SNP in the L allele has been reported to render the L allele functionally equivalent to S (Wendland et al. 2006). This SNP was assayed using the protocol of Wray et al. (2009), and the current analyses were performed reclassifying 21 LG alleles as S (LL = 101, SL = 189, SS = 91). Recoding 5-HTTLPR genotype according to rs25531 variation did not alter the current results.

Statistical Analysis

Mediation analyses were carried out using three regression equations as described by MacKinnon et al. (2002). This involved estimating the total effect of 5-HTTLPR on depression (c) and stress appraisals (α), the effect of appraisals on depression controlling for genotype (β), and the direct effect of genotype on depression controlling for appraisals (c′). Separate mediation analyses were conducted for depressive symptoms at age 20 and depression diagnoses at age 20. In these models, individual differences on the stress appraisals phenotype were assumed to precede current depression symptoms and diagnoses because, as noted above, appraisal scores are theorized to act as a dispositional vulnerability (Schless et al. 1974; Zimmerman 1983). Thus, the temporal precedence of the mediator relative to the outcome was assumed for the current analyses but impossible to prove. However, to better resolve the temporal precedence of stress appraisals relative to depression outcomes, one further set of mediation analyses was conducted with depressive symptoms at ages 22–25 as the dependent variable.

It is important to note here that we did not expect to detect a significant bivariate (i.e., direct) association between 5-HTTLPR and depression outcomes (Munafó et al. 2009). We considered it consistent with an endophenotype approach to test for indirect effects despite the absence of an overall association between 5-HTTLPR and depression. Modern guidelines for evaluating mediation, departing somewhat from the classic Baron and Kenny (1986) procedures, suggest that mediation of distal processes may be tested in the absence of a significant bivariate association between predictor and outcome if theoretical arguments indicate that the predictor-mediator and mediator-outcome associations are strong relative to the predictor-outcome association (see Collins et al. 1998; MacKinnon 2000).

An estimate of the indirect effect was computed as the product of α and β (αβ). The PRODCLIN program (MacKinnon et al. 2007) was used to obtain a 95% confidence interval (CI) around the indirect effect. Gender, maternal depression history, and chronic stress were covaried in all equations to control for their influences on stress appraisals and depression outcomes. Additionally, youth lifetime history of major depression was controlled in the regression of stress appraisals on 5-HTTLPR in all models to ensure that genetic effects are not attributable to the link between 5-HTTLPR and depression. Lifetime history of major depression was also covaried in the regression of age 22–25 BDI score on stress appraisals in the longitudinal model to isolate the unique effect of appraisals on subsequent depressive symptoms after accounting for current depression vulnerability. Finally, neuroticism scores were entered as a covariate in the regression of age 22–25 BDI on stress appraisals due to established relations of neuroticism with both 5-HTTLPR and depression (Kendler et al. 2006; Munafó et al. 2009). For all analyses, the same pattern of statistical significance for the mediation pathways was found when regardless of whether covariates were included in the models.

One dummy variable was created to represent the comparison between L homozygotes and S allele carriers, consistent with past stress sensitivity research demonstrating the phenotypic equivalence of SL and SS groups (Beevers et al. 2007; Hariri and Holmes 2006; Thomason et al. 2010). In a secondary analysis, genotype was recoded according to number of S alleles present (i.e., 0, 1, 2) to examine whether results were consistent across additive and dominant models of genetic action.

Results

Descriptive statistics of main study variables, presented separately for each 5-HTTLPR group, are shown in Table 1. Genotype groups did not differ with respect to gender (χ2(2, 381) = 1.20, P = 0.55) or the proportion of mothers reporting a history of depression prior to offspring age 15 (χ2(2, 381) = 1.89, P = 0.39). There were also no differences across groups regarding exposure to acute (F(2, 379) = 1.00, P = 0.37) or chronic (F(2, 379) = 1.36, P = 0.26) stress.

Cross-Sectional Mediation Analyses

Depressive Symptoms

First, the total effect (i.e., the c path) of 5-HTTLPR on depressive symptomatology was estimated. After partialling out the influence of all covariates, 5-HTTLPR had a small and nonsignificant main effect on BDI score (b = −0.23, SE = 0.86, P = 0.79). This result suggests that if 5-HTTLPR exerts any influence on depression, its effects are almost completely mediated by intervening variables (Shrout and Bolger 2002).

Next, genetic influences on stress appraisals were assessed by regressing the proposed mediator on 5-HTTLPR genotype. Consistent with viewing the stress appraisal construct as an endophenotype, analyses revealed a significant effect of 5-HTTLPR (b = 0.24, SE = 0.11, P = 0.03, ΔR 2 = 0.021), indicating that S allele carriers, relative to L homozygotes, displayed higher ratings of the negative impact of stressors.

In supplementary analyses, 5-HTTLPR genotype was recoded according to the number of S alleles present. After controlling for all covariates, genotype remained a significant predictor of appraisals (b = 0.15, SE = 0.07, P = 0.03), with increasing S allele load associated with elevated appraisals of negative impact. Planned pairwise comparisons revealed that the SS group did not differ from the SL group (b = 0.02, SE = 0.13, P = 0.87), whereas the LL group reported significantly lower ratings than both the SL (b = 0.27, SE = 0.11, P = 0.01) and the SS (b = 0.29, SE = 0.14, P = 0.04) groups. These results are consistent with the dominant model of the 5-HTTLPR S allele adopted initially. Therefore, results from regression equations representing genotype with one dummy variable (i.e., grouping SS and SL genotypes and contrasting them with the LL genotype) were used in the test of the indirect effect (see Table 2).

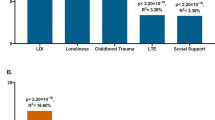

In a final equation, depressive symptoms were regressed on both 5-HTTLPR and appraisals of acute stressful life events. Controlling for 5-HTTLPR genotype, higher stress appraisal scores were associated with elevated BDI scores (b = 1.26, SE = 0.48, P = 0.01, ΔR 2 = 0.026). In contrast, after partialling out the effect of appraisals, the direct effect of 5-HTTLPR on BDI (c′) remained not reliably different from 0 (b = −0.43, SE = 0.97, P = 0.65). Figure 1 summarizes the results of the foregoing regression equations. The point estimate of the indirect effect (αβ) was 0.30, and the 95% CI around this value ranged from 0.02 to 0.72, indicating that results are consistent with a 5-HTTLPR—stress appraisals—depressive symptoms pathway of mediation.

Major Depression Diagnoses

Whereas the α path remains the same across symptom- and diagnosis-level analyses, an additional logistic regression equation with depression diagnoses as the outcome was estimated to determine β. As displayed in Table 3, appraisals were significantly associated with depression diagnoses at age 20 (P = 0.05), whereas 5-HTTLPR genotype had no effect on depression risk. Because coefficients from linear (α) and logistic (β) regressions are on different scales, each coefficient was standardized by multiplying by the standard deviation of the predictor and dividing by the standard deviation of the criterion before calculating αβ (MacKinnon and Dwyer 1993). The point estimate of αβ was 0.08 (95% CI: 0.01–0.19), indicating a significant indirect effect of 5-HTTLPR on depression diagnoses.

Longitudinal Mediation Analyses

A new β path for the longitudinal effect of appraisals on age 22–25 depressive symptoms was estimated, whereas the α path from previous analyses was retained. As noted above, youth neuroticism and lifetime history of depression were controlled in the β equation for a conservative estimate of the prospective effect of stress appraisals on depressive symptoms. Zero-order correlations revealed a small but significant association between appraisals and neuroticism (r = 0.11, P = 0.04), as compared to a negligible relation between 5-HTTLPR and neuroticism (r = 0.02, P = 0.70). As shown in Table 4, after entering all covariates, appraisals were significantly linked with future depressive symptoms (P = 0.03, ΔR 2 = 0.023), whereas 5-HTTLPR continued to have no relationship with age 22–25 BDI.Footnote 3 The indirect effect of 0.19 (95% CI: 0.01–0.48) was again significantly different from 0, providing further support for the proposed mediation model.

Discussion

The current study examined the association of 5-HTTLPR with appraisals of naturally occurring stressors and evaluated a mediational model incorporating this proposed endophenotype as an intermediary link on the causal chain from 5-HTTLPR genotype to depressive symptoms and diagnoses. In accordance with previous research documenting a link between 5-HTTLPR and varied indices of stress sensitivity, possession of the S allele was found to be associated with higher subjective ratings of the negative impact of acute stressful life events. Further, elevated appraisals of the negative impact of stressful life events were significantly linked to depression outcomes. Tests of the indirect effect of 5-HTTLPR on both depressive symptoms and diagnoses revealed significant mediation of this relationship by stress appraisals.

Lower ratings of negative event impact among L homozygotes are consistent with prior research demonstrating a buffering effect of the 5-HTTLPR LL genotype on neurobiological, neuroendocrine, and cognitive-affective reactivity to threatening cues (Beevers et al. 2009; Gotlib et al. 2008; Munafó et al. 2008). This attenuated sensitivity to threatening and emotional contexts has been hypothesized to confer resilience to depression in the face of stress (Drabant et al. 2006; Hariri and Holmes 2006; Hayden et al. 2008). Indeed, L homozygosity has been shown to provide a protective influence in the G × E literature, in which L homozygotes display only limited increments in risk for depressive symptoms and diagnoses in response to increasing stress (Caspi et al. 2010). The current results suggest that a predisposition to perceive life stressors as less threatening may be one mechanism accounting for lower rates of depressive reactions to stress among L homozygotes.

Although previous studies have hypothesized that individual differences in stress sensitivity serve as an intermediary on the path from 5-HTTLPR to depression, to our knowledge there have been no prior tests of mediational models in 5-HTTLPR endophenotype research. These findings provide direct evidence of a putative intermediate phenotype mediating the association between 5-HTTLPR and depression. Consistency of results across depressive symptoms and diagnoses suggests that the effect of 5-HTTLPR on stress appraisals is important to understanding vulnerability to major depressive disorder and not simply higher levels of general distress. Further, stress appraisals appear to predict future depressive symptoms even after accounting for current depression history and trait neuroticism. Thus, the longitudinal mediation results indicate that the influence of appraisals on depressive outcomes is not likely to be a spurious effect caused by shared variance with neuroticism. Although the stress appraisals construct appears to have a unique effect on depression, it is important to bear in mind that it constitutes only one of several biological and psychological systems predisposing to depression that are theorized to be influenced by 5-HTTLPR (Carver et al. 2008). This point is highlighted by the relatively modest effect sizes for both gene-appraisal and appraisal-symptom associations, with 5-HTTLPR explaining roughly 2% of the variation in appraisals and, in turn, appraisals accounting for 2% of the variation in current and future depressive symptoms. Future models incorporating multiple mediators acting on risk for depression are likely to provide a more complete approximation of the causal system through which 5-HTTLPR affects disease vulnerability.

The relatively small sample available for the genetic analyses requires that these results be considered tentative until large-scale replications confirm the findings. Although adopting an endophenotype approach likely enhanced our ability to detect genetic effects, it does not solve the problem of statistical power in candidate gene research (e.g., Munafó et al. 2009). Thus, while 5-HTTLPR was linked with stress sensitivity in the hypothesized direction, it is important to consider the possibility that this result was a false positive.

Several other limitations of the current study should be noted. First, although the genetic architecture of stress appraisals is purported to be simpler than that of syndromal depression, multiple genes almost certainly co-participate in causing individual differences in stress reactivity (e.g., Conway et al. 2010; Jabbi et al. 2007; Wells et al. 2010). Future studies with sufficiently large samples should examine potential gene–gene interactions involving 5-HTTLPR in predicting stress sensitivity outcomes. Second, it was beyond the scope of the current study to validate the stress appraisal construct as a depression endophenotype (see Bearden and Freimer 2006, for proposed criteria). Future work using genetically-informed designs (e.g., twin studies) is needed to support its status as an endophenotype. Further, although the results in the whole sample were identical to those in a Caucasian-only sample, it is still possible that population heterogeneity artificially inflated the genetic association with stress appraisals. Future studies would benefit form employing genomic control methods to more thoroughly account for the potentially confounding effects of population stratification (Devlin et al. 2001) Finally, computation of the stress appraisal phenotype was based on a limited number of stressful events for some participants (M = 3.22, SD = 1.95 in the current study). Future work is needed to demonstrate the reliability of this measure over time and investigate its associations with behavioral indices of stress sensitivity.

In sum, our results provide initial evidence of an association of the S allele with systematically elevated appraisals of naturally occurring stressors, consistent with prior neuroimaging and cognitive research linking 5-HTTLPR and indicators of stress reactivity. Further, the finding of an indirect effect of 5-HTTLPR on depression via variation in stress appraisals further supports the possibility that enhanced stress sensitivity acts an intermediate phenotype through which 5-HTTLPR affects risk for depression. Following the recommendation of Caspi and Moffitt (2006), this study represents a preliminary effort to integrate genetic and endophenotypic variation into psychological models of complex multifactorial disorders.

Notes

In an attempt to minimize the confounding influences of population stratification, analyses were conducted among Caucasians only (i.e., 93% of the genotyped sample). The significance and overall pattern of results were unaltered.

Preliminary analyses were conducted in which subjective negative impact ratings were the dependent variable in a linear regression model and objective ratings were entered as a covariate. This method is similar analytically to the standardized residual approach employed here (Cole et al. 1998) and the pattern of results was equivalent across analyses. Thus, for ease of presentation, only results from analyses using residuals as the dependent variable are reported.

We examined potential confounding effects of variability in the time elapsed between data collection points. Analyses showed that the length of the interval between assessments did not moderate the influence of appraisals (b = 0.02, SE = 0.05, P = 0.80) or 5-HTTLPR (b = 0.03, SE = 0.11, P = 0.82) on BDI. These results suggested that the varying length of time between assessments of the mediator and outcome was unlikely to bias parameter estimates.

References

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Bearden, C. E., & Freimer, N. B. (2006). Endophenotypes for psychiatric disorders: Ready for primetime? Trends in Genetics, 22, 306–313.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). The beck depression inventory (2nd ed.). San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

Bedford, A., & Foulds, G. (1978). Delusions-symptoms-states inventory of anxiety and depression. Windsor, England: NFER.

Beevers, C. G., Gibb, B. E., McGeary, J. E., & Miller, I. W. (2007). Serotonin transporter genetic variation and biased attention for emotional word stimuli among psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116, 208–212.

Beevers, C. G., Wells, T. T., Ellis, A. J., & McGeary, J. E. (2009). Association of the serotonin transporter gene promoter region (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism with biased attention for emotional stimuli. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 670–681.

Brown, G. W., & Harris, T. O. (1978). Social origins of depression: A study of psychiatric disorder in women. New York: Free Press.

Carver, C. S., Johnson, S. L., & Joormann, J. (2008). Serotonergic function, two-mode models of self-regulation, and vulnerability to depression: What depression has in common with impulsive aggression. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 912–943.

Caspi, A., Hariri, A. R., Holmes, A., Uher, R., & Moffitt, T. E. (2010). Genetic sensitivity to the environment: The case of the serotonin transporter gene and its implications for studying complex diseases and traits. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 509–527.

Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2006). Gene-environment interactions in psychiatry: Joining forces with neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 7, 583–590.

Caspi, A., Sugden, K., Moffitt, T. E., Taylor, A., Craig, I. W., Harrington, H., et al. (2003). Influence of life stress on depression: Moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science, 301, 386–389.

Cole, D. A., Martin, J. M., Peake, L. G., Seroczynski, A. D., & Hoffman, K. (1998). Are cognitive errors of underestimation predictive or reflective of depressive symptoms in children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107, 481–496.

Collins, L. M., Graham, J. W., & Flaherty, B. P. (1998). An alternative framework for defining mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 33, 295–312.

Conway, C. C., Hammen, C., Brennan, P. A., Lind, P. A., & Najman, J. M. (2010). Interaction of chronic stress with serotonin transporter and catechol-O-methyltransferase polymorphisms in predicting youth depression. Depression and Anxiety, 27, 737–745.

De Los Reyes, A., & Prinstein, M. J. (2004). Applying depression distortion hypotheses to the assessment of peer victimization in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 325–335.

Devlin, B., Roeder, K., & Wasserman, L. (2001). Genomic control, a new approach to genetic-based association studies. Theoretical Population Biology, 60, 155–166.

Drabant, E. M., Hariri, A. R., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., Munoz, K. E., Mattay, V. S., Kolachana, B. S., et al. (2006). Catechol O-methyltransferase val158met genotype and neural mechanisms related to affective arousal and regulation. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 1396–1406.

Espejo, E. P., Ferriter, C. T., Hazel, N. A., Keenan-Miller, D., Hoffmann, L. R., & Hammen, C. (2010). Predictors of subjective ratings of stressor severity: The effects of current mood and neuroticism. Stress and Health Epub ahead of print, doi:10.1002/smi.1315.

Eysenck, S. B. G., & Barrett, P. (1985). A revised version of the psychoticism scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 6, 21–29.

Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, S. B. G. (1975). Manual of the Eysenck personality questionnaire. London, England: Hodder & Stoughton.

First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M., & Williams, J. B. W. (1995). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I DISORDERS. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press.

Gotlib, I., & Hammen, C. (Eds.). (2008). Handbook of depression (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Gotlib, I. H., Joormann, J., Minor, K. L., & Hallmayer, J. (2008). HPA axis reactivity: A mechanism underlying the associations among 5-HTTLPR, stress, and depression. Biological Psychiatry, 63, 847–851.

Hamer, D. (2002). Rethinking behavior genetics. Science, 298, 71–72.

Hammen, C., & Brennan, P. A. (2001). Depressed adolescents of depressed and nondepressed mothers: Tests of an interpersonal impairment hypothesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 284–294.

Hammen, C., Brennan, P., & Keenan-Miller, D. (2008). Patterns of adolescent depression to age 20: The role of maternal depression and youth interpersonal dysfunction. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 1189–1198.

Hammen, C. L., Burge, D., Daley, S. E., Davila, J., Paley, B., & Rudolph, K. D. (1995). Interpersonal attachment cognitions and prediction of symptomatic responses to interpersonal stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104, 436–443.

Hammen, C., Henry, R., & Daley, S. E. (2000). Depression and sensitization to stressors among young women as a function of childhood adversity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 782–787.

Hariri, A. R., Drabant, E. M., Munoz, K. E., Kolachana, B. S., Mattay, V. S., Egan, M. F., et al. (2005). A susceptibility gene for affective disorders and the response of the human amygdala. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 146–152.

Hariri, A. R., & Holmes, A. (2006). Genetics of emotional regulation: The role of the serotonin transporter in neural function. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10, 182–191.

Hariri, A. R., Mattay, V. S., Tessitore, A., Kolachana, B., Fera, F., Goldman, D., et al. (2002). Serotonin transporter genetic variation and the response of the human amygdala. Science, 297, 400–403.

Hasler, G., Drevets, W. C., Manji, H. K., & Charney, D. S. (2004). Discovering endophenotypes for major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology, 29, 1765–1781.

Hayden, E. P., Dougherty, L. R., Maloney, B., Olino, T. M., Sheikh, H., Durbin, C. E., et al. (2008). Early-emerging cognitive vulnerability to depression and the serotonin transporter gene promoter region polymorphsm. Journal of Affective Disorders, 107, 227–230.

Heinz, A., Braus, D. F., Smolka, M. N., Wrase, J., Puls, I., & Hermann, D. (2005). Amygdala-prefrontal coupling depends on a genetic variation of the serotonin transporter. Nature Neuroscience, 8, 20–21.

Jabbi, M., Korf, J., Kema, I. P., Hartman, C., van der Pompe, G., Minderaa, R. B., et al. (2007). Convergent genetic modulation of the endocrine stress response involves polymorphic variations of 5-HTT, COMT and MAOA. Molecular Psychiatry, 12, 483–490.

Janssens, A. C., & van Duijin, C. M. (2008). Genome-based prediction of common diseases: Advances and prospects. Human Molecular Genetics, 17, 166–173.

Keenan-Miller, D., Hammen, C. L., & Brennan, P. A. (2007). Health outcomes related to early adolescent depression. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, 256–262.

Keeping, J. D., Najman, J. M., Morrison, J., Western, J. S., Andersen, M. J., & Williams, G. M. (1989). A prospective longitudinal study of social, psychological, and obstetrical factors in pregnancy: Response rates and demographic characteristics of the 8, 556 respondents. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 96, 289–297.

Kendler, K. S., Gatz, M., Gardner, C. O., & Pedersen, N. L. (2006). Personality and major depression: A Swedish longitudinal, population-based twin study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 1113–1120.

Krackow, E., & Rudolph, K. D. (2008). Life stress and the accuracy of cognitive appraisals in depressed youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 376–385.

Lau, J. Y. F., & Eley, T. C. (2010). The genetics of mood disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 313–337.

MacKinnon, D. P. (2000). Contrasts in multiple mediator models. In J. S. Rose, L. Chassin, C. C. Presson, & S. J. Sherman (Eds.), Multivariate applications in substance use research: New methods for new questions (pp. 141–160). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

MacKinnon, D. P., & Dwyer, J. H. (1993). Estimation of mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation Review, 17, 144–158.

MacKinnon, D. P., Fritz, M. S., Williams, J., & Lockwood, C. M. (2007). Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavioral Research Methods, 39, 384–389.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7, 83–104.

Monroe, S. M., & Reid, M. W. (2008). Gene-environment interactions in depression: Genetic polymorphisms and life stress polyprocedures. Psychological Science, 19, 947–956.

Munafó, M. R., Brown, S. M., & Hariri, A. R. (2008). Serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR) genotype and amygdala activation: A meta-analysis. Biological Psychiatry, 63, 852–857.

Munafó, M. R., Durrant, C., Lewis, G., & Flint, J. (2009). Gene × environment interactions at the serotonin transporter locus. Biological Psychiatry, 65, 211–219.

Pezawas, L., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., Drabant, E. M., Verchinski, B. A., Munoz, K. E., Kolachana, B. S., et al. (2005). 5-HTTLPR polymorphism impacts human cingulate-amygdala interactions: A genetic susceptibility mechanism for depression. Nature Neuroscience, 8, 828–834.

Rice, F., Harold, G. T., & Thapar, A. (2002). Assessing the effects of age, sex and shared environment on the genetic etiology of depression in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43, 1039–1051.

Risch, N., Herrell, R., Lehner, T., Liang, K.-Y., Eaves, L., Hoh, J., et al. (2009). Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events, and risk of depression. Journal of the American Medical Association, 301, 2462–2471.

Schless, A. P., Schwartz, L., Goetz, C., & Mendels, J. (1974). How depressives view the significance of life events. British Journal of Psychiatry, 125, 406–410.

Shih, J. H., Eberhart, N. K., Hammen, C. L., & Brennan, P. A. (2006). Differential exposure and reactivity to interpersonal stress predict stress differences in adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35, 103–115.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445.

Sullivan, P. F., Neale, M. C., & Kendler, K. S. (2000). Genetic epidemiology of major depression: Review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1552–1562.

Tabor, H. K., Risch, N. J., & Myers, R. M. (2002). Candidate-gene approaches for studying complex genetic traits: Practical considerations. Nature Reviews Genetics, 3, 391–397.

Thomason, M. E., Henry, M. L., Hamilton, P., Joormann, J., Pine, D., Ernst, M., et al. (2010). Neural and behavioral responses to threatening emotion faces in children as a function of the short allele of the serotonin transporter gene. Biological Psychology, 85, 38–44.

Uher, R., & McGuffin, P. (2010). The moderation by the serotonin transporter gene of environmental adversity in the etiology of depression: 2009 update. Molecular Psychiatry, 15, 18–22.

Wells, T. T., Beevers, C. G., & McGeary, J. E. (2010). Serotonin transporter and BDNF genetic variants interact to predict cognitive reactivity in healthy adults. Journal of Affective Disorders, 126, 223–229.

Wendland, J. R., Martin, B. J., Kruse, M. R., Lesch, K.-P., & Murphy, D. L. (2006). Simultaneous genotyping of four functional loci of human SLC6A4, with a reappraisal of 5-HTTLPR and rs25531. Molecular Psychiatry, 11, 224–226.

Wray, N. R., James, M. R., Gordon, S. D., Dumenil, T., Ryan, L., & Coventry, W. L. (2009). Accurate, large-scale genotyping of 5HTTLPR and flanking single nucleotide polyomrphisms in an association study of depression, anxiety, and personality measures. Biological Psychiatry, 66, 468–476.

Zimmerman, M. (1983). Using personal scalings on life event inventories to predict dysphoria. Journal of Human Stress, 9, 32–38.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate the assistance of Robyne LeBrocque, Cheri Dalton Comber, and Sascha Hardwicke (project coordinators) and their interview staff. We also thank staff of the Genetic Epidemiological Laboratory of the Queensland Institute of Medical Research: Professor Nick Martin (Head) for cooperation and access, Michael James and Leanne Ryan for 5-HTTLPR and rs25531 genotyping, and Megan Campbell and Dixie Statham who coordinated genetic data collection and analysis. Thanks also to the original MUSP principals, William Bor, MD, Michael O’Callaghan, MD, and Professor Gail Williams.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Conway, C.C., Hammen, C., Espejo, E.P. et al. Appraisals of Stressful Life Events as a Genetically-Linked Mechanism in the Stress–Depression Relationship. Cogn Ther Res 36, 338–347 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-011-9368-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-011-9368-9