Abstract

The present study examined whether the sex difference in depression could be accounted for within the framework of the hopelessness theory of depression. Specifically, we tested whether young adults’ negative inferential styles mediated the sex difference in depressive symptoms or whether sex moderated the cognitive vulnerability-stress effects on depressive symptoms in a multi-wave longitudinal study. In doing so, we examined the different forms of negative inferential styles separately (causes, consequences, self-characteristics, composite, weakest link). Results did not support the mediation hypothesis. In terms of the moderation hypothesis, we found significant sex × inferential style × stress interactions predicting depressive symptoms across the follow-up, with the vulnerability-stress effects significant for men but not women. Among women, negative inferential styles and life events were independent predictors of depressive symptoms. In these moderation analyses, each of the inferential styles exhibited similar predictive validity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One of the most consistent findings in depression research is that women are twice as likely as men to experience depression (Nolen-Hoeksema 2002). This sex difference emerges in late adolescence (Hankin et al. 1998) and continues across the lifespan (Kessler et al. 2003; Weissman et al. 1996). However, the reasons for this sex difference remain unclear. Building from cognitive vulnerability-stress theories of depression, several models have been proposed to account for the emergence of sex differences in depression (e.g., Hankin and Abramson 2001; Hyde et al. 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema and Girgus 1994). Common to each of these models is the hypothesis that cognitive vulnerabilities and/or negative life events may mediate and/or moderate the sex differences in depression.

According to the mediation hypothesis, although the same factors predict vulnerability to depression in both sexes, starting in adolescence females exhibit greater levels of these risk factors than males. Specifically, females may be more likely to exhibit a cognitive vulnerability, or experience more negative life events, particularly negative interpersonal events. According to the meditational hypothesis, therefore, although cognitive vulnerability and/or negative life events are equally likely to increase risk for depression in women and men, women are more likely to exhibit these risk factors. On the other hand, according to the moderation hypothesis, cognitive vulnerability-stress effects may be more likely or more pronounced in females than in males. Therefore, according to the moderation hypothesis, women exhibiting cognitive vulnerability may be more likely to develop depression following negative events than men.

The goal of this study was to test these two hypotheses to determine whether the vulnerabilities featured in the hopelessness theory of depression (Abramson et al. 1989) may help to explain the sex difference in depression. In so doing, we chose to focus on a young adult sample because the sex difference in depression has been found to emerge during adolescence and reach the prototypical 2:1 ratio by age 18 (Hankin et al. 1998). Therefore, by early adulthood, the sex difference in depression, as well as any potential sex differences in vulnerability factors, should be present.

In the hopelessness theory of depression (Abramson et al. 1989), cognitive vulnerability is defined as the tendency to attribute negative events to stable, global causes and to infer negative consequences and negative self-characteristics following the occurrence of negative life events. For example, a cognitively vulnerable person may explain the break-up of a relationship by saying “I’m worthless and no one will ever love me” (stable, global causal attribution implying negative consequences and negative self-characteristics), while a person without this cognitive vulnerability may think, “That person just was not right for me and I’m sure to find a better partner in the future”. These three inferential styles (causes, consequences, and self-characteristics) are hypothesized to contribute vulnerability to depression in the presence, but not absence, of negative life events. Although the three inferential styles are described as separate vulnerabilities, the majority of research has focused on an overall inferential style composite, representing one’s average level of vulnerability across the three inferential styles (for a review, see Haeffel et al. 2008). Using this inferential style composite, studies have provided strong support for the hopelessness theory’s vulnerability-stress hypothesis in predicting the development of symptoms and diagnoses of depression (for reviews see Gibb and Coles 2005; Haeffel et al. 2008; Hankin and Abela 2005).

However, it remains unclear whether the three inferential styles may contribute differentially to the sex difference in depression. Also, more recently, theorists (Abela and Sarin 2002) have suggested that one’s level of cognitive vulnerability to depression may be best characterized by the most negative of the three inferential styles (i.e., one’s “weakest link”) rather than by any single inferential style or the overall composite. For example, an individual may have an extremely negative inferential style for self-characteristics, but positive inferential styles for the causes and consequences of negative life events. The traditional composite approach would average the three inferential styles, implying a relatively neutral (or slightly positive) inferential style. In contrast, according to the weakest link hypothesis, the person would be predicted to be as vulnerable as his/her most negative inferential style (self-characteristics) regardless of how positive the other two inferential styles were. The composite approach would lead to the prediction that the individual is at low risk for depression, while the weakest link method would predict high risk. To more fully evaluate the potential differential predictive validity of each of these inferential styles, in the current study, we examined each of the three inferential styles separately as well the overall inferential style composite and each person’s weakest link.

Returning to sex differences in depression, research to date has provided mixed support for both the mediation and moderation models. In the hopelessness theory, a mediation account requires females to report more negative life events or more negative inferential styles, which in turn mediate the sex difference in depression. Consistent with this model, there is evidence that adolescent girls report experiencing more negative life events than boys, particularly in the interpersonal domain (e.g., Ge et al. 1994; Hankin et al. 2007; Rose and Rudolph 2006; Schraedley et al. 1999; Schwartz and Koenig 1996). Further, these differences in negative life events have been found to partially mediate the sex difference in adolescents’ depressive symptoms (Hankin et al. 2007; Rudolph 2002; Rudolph and Hammen 1999). We should note, however, that similar sex differences in negative events have generally not been found in adult samples (Davis et al. 1999; Kendler et al. 2001; for a review, see Hammen 2005).

There is also mixed evidence for sex differences in inferential styles. For example, although a few studies have found that females report more negative inferential styles than males in adolescence and adulthood (Abela 2001, Hankin 2006; Boggiano and Barrett 1991; Hankin and Abramson 2002; Schwartz and Koenig 1996; for review see Mezulis et al. 2004), the majority of studies have failed to find evidence of significant sex differences in inferential styles (e.g., Abela 2002; Abela and Seligman 2000; Gibb et al. 2003; Gladstone et al. 1997; Hankin et al. 2004, 2001; Haeffel et al. 2007). This said, there is evidence from one study that inferential styles (for causes and self-characteristics) do mediate the sex difference in depressive symptoms among adolescents (Hankin and Abramson 2002), suggesting that meditational effects may be stronger for some inferential styles than others.

Previous research has also provided mixed support for the moderation hypothesis. For example, whereas, some studies among adolescents have suggested that inferential styles are more likely to moderate the relation between negative life events and depressive symptoms in girls than boys (Abela 2001; Abela and McGirr 2007), other studies have found the reverse pattern (Hankin et al. 2001; Morris et al. 2008). In contrast, the few other studies examining sex moderation have not yielded significant effects in adolescents (Abela 2002; Hankin 2008) or college students (Abela and Seligman 2000). The present study builds upon prior work by providing a more thorough test of whether sex moderates the vulnerability-stress component in the hopelessness theory in young adults. Specifically, the only study of which we are aware of to have compared the utility of the three separate inferential styles against the composite and weakest link measures in an adult sample did not explore the effects of participants’ sex (Abela et al. 2006). In the proposed, study, therefore, we sought to provide a more comprehensive test of mediation and moderation hypotheses regarding sex differences in depression within the context of the hopelessness theory by examining the different forms of negative inferential style (causes, consequences, self-characteristics, composite, weakest link) separately in a relatively large sample of young adults.

The goal of the current study was to determine whether aspects of the hopelessness theory of depression may help to explain the sex difference in depression. In so doing, we tested both mediation and moderation models of risk. According to the mediation model, the sex difference in depressive symptoms should be mediated by women’s higher levels of negative inferential styles and/or negative events. According to the moderation model, sex should moderate the cognitive vulnerability-stress effects upon depressive symptoms such that cognitively vulnerable women should be more likely than men with similar levels of cognitive vulnerability to exhibit depressive reactions to negative events. In each of these analyses, we examined the different inferential styles separately (causes, consequences, self-characteristics, composite, weakest link) to determine whether they exhibited similar versus differential predictive validity.

Method

Participants

Participants were 458 freshmen recruited from the general student population of a state university. Of the 458 participants, 284 (62%) were female, and the mean age at baseline was 18.14 years (SD = 0.45). In terms of race, 66% were Caucasian, 20% were Asian/Asian–American, 6% were African–American, 4% were Biracial, <1% were either Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander or American Indian/Alaska Native, and 3% failed to report their race. Further, of those reporting their ethnicity, 10% were Hispanic, and 90% were Non-Hispanic (7% did not report their ethnicity). There were no exclusion criteria.

Measures

Inferential Styles

The Cognitive Style Questionnaire (CSQ; Haeffel et al. 2008) was used to assess cognitive vulnerability to depression as defined by the hopelessness theory (Abramson et al. 1989). The CSQ contains 24 hypothetical events (12 positive and 12 negative). In the current study, only the negative events were used because previous studies have shown that inferences for negative events are more strongly related to depressive symptoms than are inferences for positive events (e.g., Alloy et al. 2000). In response to each of the hypothetical events (e.g., “You want to be in an intimate, romantic relationship, but aren’t.”), the participant is asked to indicate what he or she believes would be the major cause of the event if it happened to him or her. In addition, the participant is asked to answer a series of questions about the cause and consequences of each event, as well as what the occurrence of the event would mean for his or her self-concept. Composite scores for each inferential style are created by averaging responses to the relevant questions, with higher scores indicating a more negative inferential style. A number of studies have supported the reliability and validity of the CSQ (for a review, see Haeffel et al. 2008). For the current study, we focused individually on participants’ inferential styles for causes (average of stability and globality ratings; α = .92), consequences (α = .90), and self-characteristics (α = .92). We also examined the overall composite, which is created by averaging participants’ inferences regarding causes, consequences, and self-characteristics (α = .96). Finally, we calculated each participant’s “weakest link”, or most negative of the three inferential styles. In this study, inferential styles for the causes of negative events were weakest for 59% of the sample, inferential styles for consequences were weakest for 16%, inferential styles for self-characteristics were weakest for 21% of the sample, and two or more inferential styles were “weakest” for 4% of the sample.

Depressive Symptoms

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al. 1996) was used to assess participants’ levels of depressive symptoms. The BDI-II consists of 21 self-report items, each rated on a four point Likert-type scale. Total scores on the BDI-II range from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating more severe levels of depressive symptoms. Studies have supported the reliability and validity of the BDI-II in both clinical and nonclinical samples (Beck et al. 1996). In the current study, BDI-II scores exhibited excellent internal consistency (α ranged between .90 and .92 across the four time points).

Negative Life Events

Negative life events were assessed using the Life Experiences Survey (LES; Sarason et al. 1978). The LES is a 60-item survey that assesses whether adults have experienced a variety of life events within the previous 6 months. Individuals note whether each individual event occurred, then rated the impact of those events on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from extremely positive (+3) to extremely negative (−3). The LES has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity in previous research (e.g., Sarason et al. 1978). To reduce the potential for response bias associated with depressive symptoms, we focused on the number of negative events endorsed (i.e., the number of events rated as having an impact of −1 to −3) rather than the impact ratings themselves. In addition to the total number of negative events, we also examined negative interpersonal events, specifically. Negative interpersonal events within the LES were identified by having 10 advanced graduate students categorize each event as either interpersonal or non-interpersonal. The 37 items categorized by at least eight of the ten graduate students as being interpersonal or social in nature were then used to calculate the total number of negative interpersonal events.

Procedure

Participants completed self-report questionnaires at four time-points approximately 2 months apart: baseline, 2, 4, and 6 months, respectively. At baseline, participants completed surveys on cognitive style, depressive symptoms, and life events in addition to other measures not included in the current study. Measures of depressive symptoms and negative life events were also administered at each of the follow-up assessments. The baseline and final assessments were completed in person, while the 2 and 4 month assessments were completed via a secure project website. Of the 458 participants, 417 (91%) completed all four assessments, 435 (95%) completed at least three assessments, and 444 (97%) completed at least two assessments. Participants were compensated for their time with $10 for both the initial and final assessments, and $5 for each of the online follow-ups. Individuals who completed all four assessments received an additional $10 bonus.

Results

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations among each of the study variables are presented in Table 1. Before testing the mediation and moderation models, confirmatory factor analyses were conducted using AMOS 7 (Arbuckle 2006) to determine whether participants’ inferential styles for causes, consequences, and self-characteristics were indeed differentiable in this sample. Specifically, we tested two models in which the three inferential styles were included as observed variables. In the first, the correlations among the three inferential styles were allowed to freely vary. In the second, nested, model, the correlations among the three inferential styles were constrained to be 1.00. Because the model with freely varying correlations was fully saturated, overall fit indices could not be computed. However, we could compare the two models to determine relative fit using a nested model comparison. In these analyses, if the constrained model fit significantly worse than the model in which the correlations were free to vary, it would suggest that the three inferential styles are differentiable in this sample. Indeed, the constrained model was found to fit significantly worse, χ 2(3) = 40.81, P < .001, suggesting that the three inferential styles are better conceptualized as distinct than as reflecting a single, unitary construct. Nested model comparisons were also used to determine whether these results differed for women versus men, and the fit of the correlated inferential styles model did not differ based on sex, χ 2(3) = 2.83, P = .42. Therefore, although highly correlated (rs = .76–.82; see Table 1), the three inferential styles are differentiable in this sample for both women and men.

Tests of the Mediation Hypothesis

Before formally testing the mediational models, we first tested for potential sex differences in participants’ inferential styles and trajectories in negative life events and depressive symptoms. There were no sex differences in any of the inferential style variables (largest r effectsize = .07, lowest P = .13). Because the meditation hypothesis rests on the assumption of sex differences in inferential styles, the hypothesis was not supported. This said, additional analyses were conducted to test for potential sex differences in trajectories of negative events or depressive symptoms across the follow-up using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM; Raudenbush and Byrk 2002; Raudenbush et al. 2004). There are a number of benefits of HLM over more traditional data analytic approaches such as hierarchical linear regression including (a) the ability to account for the nested structure of the data (repeated assessments of negative events and depressive symptoms for each participant), (b) the focus on ideographic relations between negative events and depressive symptoms for each participant rather than the more traditional nomothetic approach of comparing each participant to the group mean, and (c) the ability to obtain maximum likelihood estimates of missing data, thereby allowing us to retain all participants for the analyses (cf. Schafer and Graham 2002). The Level 1 model for these HLM analyses was:

where Outcome ij represents the negative events or BDI-II score (examined in separate analyses) on week i for participant j, π 0j is the intercept, π 1j is the slope of the linear trajectory in negative events or depressive symptoms across the follow up for participant j (coded as the number of weeks since the initial assessment), and e ij represents the error term.

The level 2 model was:

where β 01 and β 11 are the cross-level interaction terms representing the effects of sex on the respective level 1 effects. In these equations, β 00 and β10 represent the intercepts of their respective equations and r 0j and r 1j represent the error terms. In these analyses, we found no significant sex differences in initial levels (intercepts), t(456) = 1.48, P = .14, r effectsize = .07, or trajectories, t(456) = −0.84, P = .40, r effectsize = .04, of negative life events over the follow-up. Similar results were obtained when we focused specifically on negative interpersonal events (largest r effectsize = .06, lowest P = .24). In contrast, there were significant sex differences in depressive symptom trajectories over time. Specifically, women reported higher depressive symptom levels at the initial assessment (significant intercept effect), t(456) = 3.25, P = .002, r effectsize = .15. In addition, although there was a nonsignificant trend for depressive symptom levels to decrease across the follow-up, t(456) = −1.92, P = .06, r effectsize = .09, sex did not significantly moderate this trend, t(456) = 0.22, P = .83, r effectsize = .01, indicating that the sex difference in depressive symptoms observed at the initial assessment was maintained across the follow-up. The current results, therefore, provided no support for the mediation hypothesis. Specifically, although we found sex differences in depressive symptom trajectories, there were no significant differences in inferential styles or trajectories in negative life events.

Tests of the Moderation Hypothesis

Next, we tested the cognitive vulnerability-stress hypothesis for each of the inferential style variables, as well as whether participant sex moderated any of these relations. Given the number of tests conducted, the critical alpha level was adjusted to reduce the likelihood of Type I errors. To also reduce the likelihood of Type II errors, we conducted a Bonferonni correction for the number of families of tests (i.e., the number of inferential style variables examined; n = 5) rather than the number of overall tests conducted. This gave us a critical alpha level of .01 (.05/5).

The level 1 model in these HLM analyses was:

where BDI-II ij represents the BDI-II score on week i for participant j, π 0j is the BDI-II intercept, π 1j is the slope of the linear trajectory in depressive symptoms across the follow up for participant j, π 2j is the slope of the relation between LES and BDI-II scores at each assessment, and e ij represents the error term.

The level 2 model was:

The primary effects of interest in these analyses are β 22, which represents the cross-level inferential styles × events interaction predicting depressive symptom levels and β 23, which represents the sex × cognitive vulnerability × stress interaction.

The results of these analyses are presented in Table 2. As can be seen in the table, there were significant sex × inferential style interactions for the BDI-II intercept for each of the measures of inferential style (all Ps < .001), reflecting the fact that inferential styles were differentially related to depressive symptom levels among women versus men, in the absence of negative life events (LES scores of zero). Specifically, each of the inferential styles was significantly more strongly related to the depressive symptom intercept among women (r effectsizes = .42 to .47, all Ps < .001) than among men (r effectsizes = .14 to .16, Ps = .08–.04). In terms of the vulnerability-stress hypothesis, there were significant sex × inferential style × negative events interactions for each of the inferential styles except for consequences. We should note, however, that the 3-way interaction for consequences was marginally significant (P = .02) using our adjusted critical alpha level and the size of this effect (r effectsize = −.11) was virtually identical to those observed for the other sex × inferential style × negative events interactions.

To explore the forms of these interactions, the inferential style × negative events interactions were examined separately in women and men. Although we also explored the form of the interaction for the consequences dimension, these analyses should be interpreted with caution given the nonsignificant trend noted above. Contrary to expectation, these analyses revealed significant vulnerability-stress effects for men, but not women. Specifically, among men, the inferential styles significantly moderated the slope of the relation between levels of negative life events and depressive symptoms for causes, t(171) = 2.65, P = .009, r effectsize = .20, consequences, t(171) = 2.64, P = .01, r effectsize = .20, self-characteristics, t(171) = 2.69, P = .008, r effectsize = .20, composite scores, t(171) = 3.07, P = .003, r effectsize = .23, and weakest link, t(171) = 2.74, P = .007, r effectsize = .21.

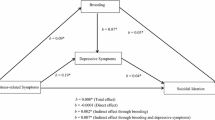

In contrast, among women, the vulnerability-stress relation was not significant for any of the inferential styles (lowest P = .80). The pattern of these results is depicted in Fig. 1, created by solving the HLM equations substituting values one standard deviation above and below the mean for each measure of inferential style (cf. Aiken and West 1991). As can be seen in the figure, among men, each of the negative inferential styles (causes, consequences, self-characteristics, composite, and weakest link) were related to depressive symptom elevations at high, but not low, levels of negative life events. Among women, inferential styles and negative life events were independent predictors of depressive symptom elevations (i.e., the main effects were significant but the interactions were not). Exploratory analyses were also conducted to examine the unique predictive validity of the three individual inferential styles (causes, consequences, self-characteristics) among men. Specifically, all three inferential styles were entered simultaneously in level 2 of the HLM analysis. Statistically controlling for the overlap among the three inferential styles, none of the vulnerability-stress relations remained significant (lowest P = .25).

Vulnerability-stress relations for each of the inferential style variables for women and men. Top row presents results for inferential styles for causes (left), consequences (middle), and self-characteristics (right). Bottom row presents results for the inferential style overall composite (left) and weakest link (right). BDI-II = Beck depression inventory-II

The cognitive vulnerability-stress hypothesis was retested with only the interpersonal events from the LES. Using our adjusted critical alpha level, none of the vulnerability-stress interactions were significant (lowest P = .02), nor were any of the sex × inferential style × negative event interactions (lowest P = .03).Footnote 1

Discussion

In this study, we tested mediation and moderation models of sex differences in depression (Hankin and Abramson 2001; Hyde et al. 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema and Girgus 1994) in the context of the hopelessness theory (Abramson et al. 1989) using data from a prospective multi-wave study of young adults. The results did not support the mediation model. Specifically, although we found sex differences in depressive symptoms, with women exhibiting higher depressive symptom levels across the follow-up than men, there were no significant sex differences in any of the inferential styles (causes, consequences, self-characteristics, composite, or weakest link) nor were there significant sex differences in trajectories of negative events over the follow-up. The results were also not consistent with our moderation hypothesis. Specifically, although we found significant sex × inferential style × negative event interactions predicting depressive symptoms across the follow-ups, the cognitive vulnerability-stress hypothesis was supported in men, not women. In contrast, among women, inferential styles and negative events were independent risk factors for depressive symptoms. Therefore, whereas, among men, negative inferential styles were only associated with elevated depressive symptoms in the presence of high levels of negative life events, among women, negative inferential styles were associated with depressive symptom elevations even at low levels of negative events.

In addition to replicating the well-established sex difference in depression (for a review, see Nolen-Hoeksema 2002), the current study adds to a growing body of research suggesting that there may be no consistent sex difference in levels of negative inferential styles (e.g., Abela and Seligman 2000; Gibb et al. 2003; Hankin et al. 2004; Haeffel et al. 2007). Although inferential styles do not appear to play a mediating role, studies have found consistent evidence for sex differences in other cognitive vulnerabilities such as rumination and there is evidence that rumination mediates the sex difference in depression (for a review, see Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008). In combination with the current results, these findings suggest the potential for specificity in terms of the mediation hypothesis. That is, a comparison of the various cognitive vulnerabilities featured in cognitive models of depression may help tease apart more likely mechanisms that help explain the sex difference in depression. Future research would benefit from the inclusion of measures assessing various forms of cognitive vulnerability (e.g., rumination, inferential style, dysfunctional attitudes) to more systematically test this hypothesis.

In contrast to studies on adolescents (e.g., Ge et al. 1994; Hankin et al. 2007; Rose and Rudolph 2006; Schraedley et al. 1999; Schwartz and Koenig 1996), we found no sex difference in trajectories of negative life events between young men and women, even when we limited our analyses to negative interpersonal events. There are several plausible explanations for the results in the present study. First, it may be that the LES does not provide a sensitive enough measure of the types of negative life events young women in particular may experience (e.g., arguments or difficulties with peers, sexual abuse). That said, these results are consistent with prior research suggesting that sex differences in adults’ experiences with episodic negative events may be limited to specific types of events (for review see Hammen 2005) rather than negative (interpersonal) events more generally. For example, adult women appear more likely than men to experience housing problems, loss of confidants, or difficulties with individuals in their social network (Kendler et al. 2001).

A second possibility is that young women may report fewer negative events compared to adolescents, although researchers have not proposed a rationale for why females would encounter fewer obstacles as adults. Finally, a third possibility is that young men, particularly college freshmen, may experience more negative life events than during adolescence, making rates comparable to women’s report as adults. This possibility is supported by research suggesting that the transition to college is a difficult period of adjustment for both men and women (e.g., Larose and Boivin 1998; Mounts et al. 2006; White et al. 2006). Overall results are consistent with prior research suggesting that adult men and women experience similar rates of acute negative events. Future work may continue to explore whether women are more sensitive or reactive to specific negative events (Hammen 2005).

As noted above, the cognitive vulnerability-stress hypothesis was supported for men, but not women, in this study. Specifically, among men, increasing numbers of negative life events were associated with higher depressive symptom levels among those exhibiting more negative inferential styles (causes, self-characteristics, composite, and weakest link). In contrast, among women, inferential styles and negative life events appeared to be independent predictors of depressive symptoms. In fact, women with negative inferential styles experienced higher levels of depressive symptoms than men, regardless of their level of negative life events. This pattern of sex moderation in the present study may have been due to a number of factors. First, it is possible that the hopelessness theory’s vulnerability-stress hypothesis is less applicable to women than men. This is consistent with research among adolescents in which the cognitive vulnerability-stress hypothesis was significant among boys, but not girls (Hankin et al. 2001; see also Morris et al. 2008). However, other studies have found stronger support for the cognitive vulnerability-stress interaction in adolescent girls than boys (Abela 2001; Abela and McGirr 2007). Finally, we are aware of only two studies to test sex moderation of the cognitive vulnerability-stress hypothesis among young adults (Abela 2002; Abela and Seligman 2000). Although these studies failed to find sex moderation effects, this may have been due in part, to the relatively small sample sizes (ns = 67–149), which may have limited statistical power to detect these effects.

Although conclusions must remain tentative pending replication in other large samples, the hopelessness theory’s vulnerability-stress hypothesis may be more applicable for men than women. Importantly, we found similar effects for inferential styles regarding causes, consequences, and self-characteristics, as well as the overall composite and weakest link suggesting that sex moderation effects are not limited to any one inferential style in young adults. Given this, future studies examining cognitive models of increased rates of depression among women may wish to focus on other forms of cognitive vulnerability (e.g., rumination; see Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008).

Finally, we should highlight the results of our analyses comparing the different inferential styles. Specifically, we compared the predictive validity of the inferential style composite with each of the three inferential styles individually and each person’s “weakest link” or most negative inferential style. Focusing on the vulnerability-stress hypothesis, each of the inferential styles yielded the same pattern of results.Footnote 2 On a pragmatic level, this challenges the necessity of measures of cognitive vulnerability that require assessing all three inferential styles, such as the composite score and weakest link approach, and suggests that assessing any of the three individual inferential styles may suffice. In this light, the current results replicate other recent findings with adolescents (Calvete et al. 2008) and adults (Abela et al. 2006), which suggest that individual inferential styles perform at least as well as the overall composite or weakest link. Given the discrepancy between these results and those obtained in child samples (see Abela and Hankin 2008, for a review), additional research is needed to determine more precisely the developmental differences in the predictive validity of the different inferential styles, weakest link, and overall composite. Theorists have hypothesized that the different inferential styles may develop independently during childhood and consolidate into a single, higher-order vulnerability by early adulthood (see Abela and Hankin 2008). Our results are consistent with this hypothesis in that each of the measures of inferential style exhibited similar predictive validity. The ideal test of this developmental hypothesis, would involve longitudinal research in which the correlations among the inferential styles are compared as children transition through adolescence.

Strengths of this study included its large sample and prospective, multi-wave design. However, there were limitations as well. First, only self-report measures were utilized and it is possible that shared method variance inflated the relations among study variables. Also, it is possible that participants’ reports of negative events were subject to recall or response biases based on participants’ current depressive symptoms. Although we sought to minimize the potential for this type of bias by focusing on event counts rather than subjective severity ratings, future research would benefit from the inclusion of interviewer-administered contextual threat interviews to assess negative events (e.g., Duggal et al. 2000). Further, stress interviews allow for the assessment of chronic forms of stress that women may be more prone to encounter (for review see Hammen 2005). A second limitation was our focus on college students who, on average, exhibited fairly low levels of depression. Future research is needed to determine whether the current results will generalize to more severe levels of depressive symptoms and to the prediction of depression episode onset.

In summary, although we found sex differences in levels of depressive symptoms in this sample of young adults, none of the components of the hopelessness theory’s cognitive vulnerability-stress model explained this difference. Specifically, there were no sex differences in any of the inferential styles, nor were there sex differences in trajectories of negative events across the follow-up. We did find the predicted sex × inferential style × negative event interaction; however, the form of this interaction was such that the cognitive vulnerability-stress hypothesis was supported for men, not women. Future studies should seek to determine whether the hopelessness theory’s cognitive vulnerability-stress hypothesis is a stronger predictor of depression in men than women. Future research is also needed in which multiple forms of cognitive vulnerability are assessed in the same study (e.g., inferential styles and rumination) to more definitively determine whether certain forms of the cognitive vulnerability-stress relations are more applicable to women versus men. The current results also indicate the various inferential styles—causes, consequences, self-characteristics, composite, weakest link—perform similarly in terms of predictive validity for depressive symptoms in young adults. Given evidence of differential predictive validity in children (for a review, see Abela and Hankin 2008), future research is needed to examine developmental trends in the differential predictive validity of the individual inferential styles versus the overall composite and weakest link.

Notes

Although the vulnerability-stress interactions specific to negative interpersonal events did not reach significance according to our adjusted critical alpha level (α crit = .01), the pattern is virtually identical to the sex × inferential style × events interaction with overall negative events. Specifically, among the men, negative inferential styles were related to depressive symptom elevations at high, but not low, levels of negative interpersonal events. In contrast, among women, inferential styles and negative interpersonal events were independent predictors of depressive symptom elevations.

Although the sex × consequences inferential style × events interaction was a nonsignificant trend (P = .02) using our adjusted critical alpha level (α crit = .01), the effect size for this three-way interaction (r effectsize = .11) was virtually to that obtained for the other inferential styles (r effectsize = .12 to .13) and the consequences × negative events interaction was significant among men but not women, just as for the other inferential styles.

References

Abela, J. R. Z. (2001). The hopelessness theory of depression: A test of the diathesis-stress and causal mediation components in third and seventh grade children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29, 241–254. doi:10.1023/A:1010333815728.

Abela, J. R. Z. (2002). Depressive mood reactions to failure in the achievement domain: A test of the integration of the hopelessness and self-esteem theories of depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 26, 531–552. doi:10.1023/A:1016236018858.

Abela, J. R. Z., Aydin, C., & Auerbach, R. P. (2006). Operationalizing the “vulnerability” and “stress” components f the hopelessness theory of depression: A multi-wave longitudinal study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 1565–1583. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.11.010.

Abela, J. R. Z., & Hankin, B. L. (2008). Cognitive vulnerability to depression in children and adolescents: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In J. R. Z. Abela & B. L. Hankin (Eds.), Handbook of depression in children and adolescents (pp. 35–78). New York: Guilford.

Abela, J. R. Z., & McGirr, A. (2007). Operationalizing cognitive vulnerability and stress from the perspective of the hopelessness theory: A multi-wave longitudinal study of children of affectively ill parents. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 46, 377–395. doi:10.1348/014466507X192023.

Abela, J. R. Z., & Sarin, S. (2002). Cognitive vulnerability to hopelessness depression: A chain is only as strong as its weakest link. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 26, 811–829. doi:10.1023/A:1021245618183.

Abela, J. R. Z., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2000). The hopelessness of depression: A test of the diathesis-tress component in the interpersonal and achievement domains. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24, 361–378. doi:10.1023/A:1005571518032.

Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., & Alloy, L. B. (1989). Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review, 96, 358–372. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.96.2.358.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Hogan, M. E., Whitehouse, W. G., Rose, D. T., Robinson, M. S., et al. (2000). The temple-wisconsin cognitive vulnerability to depression project: Lifetime history of axis I psychopathology in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 403–418. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.403.

Arbuckle, J. L. (2006). Amos 7.0 user’s guide. Chicago: SPSS.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Boggiano, A. K., & Barrett, M. (1991). Gender differences in depression in college students. Sex Roles, 25, 595–605. doi:10.1007/BF00289566.

Calvete, E., Villardón, L., & Estévez, A. (2008). Attributional style and depressive symptoms in adolescents: An examination of the role of various indicators of cognitive vulnerability. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 944–953. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2008.04.010.

Davis, M. C., Matthews, K. A., & Twamley, E. W. (1999). Is life more difficult on mars of Venus? A meta-analytic review of sex differences in major and minor life events. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 21, 83–97. doi:10.1007/BF02895038.

Duggal, S., Malkoff-Schwartz, S., Birmaher, B., Anderson, B. P., Matty, M. K., Houck, P. R., et al. (2000). Assessment of life stress in adolescents: Self-report versus interview methods. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 445–452. doi:10.1097/00004583-200004000-00013.

Ge, X., Lorenz, F. O., Conger, R. D., Elder, G. H., & Simons, R. L. (1994). Trajectories of stressful life events and depressive symptoms during adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 30, 467–483. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.30.4.467.

Gibb, B. E., Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., & Marx, B. P. (2003). Childhood maltreatment and maltreatment-specific inferences: A test of Rose and Abramson’s (1992) extension of the hopelessness theory. Cognition and Emotion, 17, 917–931.

Gibb, B. E., & Coles, M. E. (2005). Cognitive vulnerability-stress models of psychopathology: A developmental perspective. In B. L. Hankin & J. R. Z. Abela (Eds.), Development of psychopathology: A vulnerability-stress perspective (pp. 104–135). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gladstone, T. R. G., Kaslow, N. J., Seeley, J. R., & Lewinsohn, P. M. (1997). Sex differences, attributional style, and depressive symptoms among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 25, 297–305. doi:10.1023/A:1025712419436.

Haeffel, G. J., Abramson, L. Y., Brazy, P. C., Shah, J. Y., Teachman, B. A., & Nosek, B. A. (2007). Explicit and implicit cognition: A preliminary test of a dual-process theory of cognitive vulnerability to depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 1155–1167. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2006.09.003.

Haeffel, G. J., Gibb, B. E., Metalsky, G. I., Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Hankin, B. L., et al. (2008). Measuring cognitive vulnerability to depression: Development and validation of the cognitive style questionnaire. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 824–836. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2007.12.001.

Hammen, C. (2005). Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 293–319. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938.

Hankin, B. L. (2006). Adolescent depression: Description, causes, and interventions. Epilepsy & Behavior, 8, 102–114. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.10.012.

Hankin, B. L. (2008). Cognitive vulnerability-stress model of depression during adolescence: Investigating symptom specificity in a multi-wave prospective study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 999–1014. doi:10.1007/s10802-008-9228-6.

Hankin, B. L., & Abela, J. R. Z. (2005). Depression from childhood through adolescence and adulthood: A developmental vulnerability and stress perspective. In B. L. Hankin & J. R. Z. Abela (Eds.), Development of psychopathology: A vulnerability-stress perspective (pp. 104–135). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hankin, B. L., & Abramson, L. Y. (2001). Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 773–796. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773.

Hankin, B. L., & Abramson, L. Y. (2002). Measuring cognitive vulnerability to depression in adolescence: Reliability, validity, and gender differences. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31, 491–504.

Hankin, B. L., Abramson, L. Y., Miller, N., & Haeffel, G. J. (2004). Cognitive vulnerability-stress theories of depression: Examining affective specificity in the prediction of depression versus anxiety in three prospective studies. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 28, 309–345. doi:10.1023/B:COTR.0000031805.60529.0d.

Hankin, B. L., Abramson, L. Y., Moffitt, T. E., McGee, R., Silva, P. A., & Angell, K. E. (1998). Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107, 128–140. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.107.1.128.

Hankin, B. L., Abramson, L. Y., & Siler, M. (2001). A prospective test of the hopelessness theory of depression in adolescence. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 25, 607–632. doi:10.1023/A:1005561616506.

Hankin, B. L., Mermelstein, R., & Roesch, L. (2007). Sex differences in adolescent depression: Stress exposure and reactivity models. Child Development, 78(1), 279–295. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00997.x.

Hyde, S. H., Mezulis, A. H., & Abramson, L. Y. (2008). The ABCs of depression: Integrating affective, biological, and cognitive models to explain the emergence of gender differences in depression. Psychological Review, 115, 291–313. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.291.

Kendler, K. S., Thornton, L. M., & Prescott, C. A. (2001). Gender differences in the rates of exposure to stressful life events and sensitivity to their depressogenic effects. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 587–593. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.587.

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Koretz, D., Merikangas, K. R., et al. (2003). The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R). Journal of the American Medical Association, 289, 3095–3105. doi:10.1001/jama.289.23.3095.

Larose, S., & Boivin, M. (1998). Attachment to parents, social support expectations, and socioemotional adjustment during the high school-college transition. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 8, 1–27. doi:10.1207/s15327795jra0801_1.

Mezulis, A. H., Abramson, L. Y., Hyde, J. S., & Hankin, B. L. (2004). Is there a universal polarity bias in attributions? A meta-analytic review of individual, developmental, and cultural differences in the self-serving attributional bias. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 711–747. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.711.

Morris, M. C., Ciesla, J. A., & Garber, J. (2008). A prospective study of the cognitive-stress model of prospective symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117, 719–734. doi:10.1037/a0013741.

Mounts, N. S., Valentiner, D. P., Anderson, K. L., & Boswell, M. K. (2006). Shyness, sociability, and parental support for the college transition: Relation to adolescent’s adjustment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 71–80. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-9002-9.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2002). Gender differences in depression. In I. H. Gotlib & C. L. Hammen (Eds.), Handbook of depression (pp. 492–509). New York: Guilford Press.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Girgus, J. (1994). The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 424–443. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.115.3.424.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 400–424. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x.

Raudenbush, S. W., Bryk, A. S., Cheong, Y. F., & Congdon, R. (2004). HLM 6: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Byrk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rose, A. J., & Rudolph, K. D. (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 98–131. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98.

Rudolph, K. (2002). Gender differences in emotional responses to interpersonal stress during adolescence. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 30, 3–13. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00383-4.

Rudolph, K. D., & Hammen, C. (1999). Age and gender as determinants of stress exposure, generation, and reactions in youngsters: A transactional perspective. Child Development, 70, 660–677. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00048.

Sarason, I. G., Johnson, J. H., & Siegel, J. M. (1978). Assessing the impact of life changes: Development of the life experiences survey. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 46, 932–946. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.46.5.932.

Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of art. Psychological Methods, 7, 147–177. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147.

Schraedley, P. K., Gotlib, I. H., & Hayward, C. (1999). Gender differences in correlates of depressive symptoms in adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 25, 98–108. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00038-5.

Schwartz, J. A. J., & Koenig, L. J. (1996). Response styles & negative affect among adolescents. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 20, 13–36. doi:10.1007/BF02229241.

Weissman, M. W., Bland, R. C., Canino, G. J., Faravelli, C., Greenwald, S., Hwu, H., et al. (1996). Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. Journal of the American Medical Association, 276, 293–299. doi:10.1001/jama.276.4.293.

White, H. R., McMorris, B. J., Catalano, R. F., Fleming, C. B., Haggerty, K. P., & Abbott, R. D. (2006). Increases in alcohol and marijuana use during the transition out of high school into emerging adulthood: The effects of leaving home, going to college, and high school protective factors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67, 810–822.

Acknowledgment

Support for this research was provided by NIMH Award 1 R03 MH074790-01A1 awarded to the final author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stone, L.B., Gibb, B.E. & Coles, M.E. Does the Hopelessness Theory Account for Sex Differences in Depressive Symptoms Among Young Adults?. Cogn Ther Res 34, 177–187 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-009-9241-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-009-9241-2