Abstract

Interest groups ‘caught’ influencing public policy solely for private gain risk public backlash. These risks can be diminished, and rent seeking efforts made more successful, when moral or social arguments are employed in pushing for changes to public policy. Following Yandle’s Bootlegger and Baptist model, we postulate this risk differential should manifest itself in regulatory output with social regulations being more responsive to political influence than economic regulations. We test, and confirm, our theory using data on economic and social regulations from the new RegData project matched with data on campaign contributions and lobbying activity at the industry level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Blatantly self-serving behavior rarely makes for good politics. The general public and news media are quick to take note when special interests take advantage of the political process in a way that’s clearly self-serving. Consider, for example, the American Insurance Group (AIG) bonus controversy at the height of the financial crisis.Footnote 1 When AIG executives decided to pay themselves previously contracted bonuses, after receiving public dollars through government bailouts, the public backlash was readily apparent. President Obama summed up voter frustration by asking corporate executives, “How do they justify this outrage to the taxpayers who are keeping the company afloat?” Public pressure rose to a point that executives agreed to give back their bonuses. This was not enough to stymie the public’s outrage. Indeed, public sentiment toward Wall Street bailouts stayed negative for years, as the later Occupy Wall Street movement demonstrated.Footnote 2

A similar outcry occurred in early 2010, when the Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling in the case of Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, stating that the Constitution prohibited the government from restricting independent political expenditures by corporations and unions. What followed was a political maelstrom of media, politicians, and citizen groups outraged at the prospect of the business community investing an unrestricted number of dollars to garner government favors through influencing campaigns and public policy. At the time of the ruling,Footnote 3 80 percent of Americans opposed the court’s decision with later polls showing no sign of this animosity abetting.Footnote 4 In the language of economics, people feared this ruling would give way to an expansion in rent-seeking activities by corporations for their private gain (see Tullock 1967). But as Issacharoff and Peterman (2013, p. 186) indicate, “Despite significant legal changes and the jarring influx of private money in the 2012 election, the influence of interest groups on campaigns changed less than might have been expected.”

Rent seeking is risky for those involved. Previous literature, such as Hillman and Katz (1984), has pointed out that rent seeking is risky in that expenditures may be undertaken that do not produce a payoff or results (for the party that doesn’t win the non-divisible rent).Footnote 5 Our main argument is that rent-seeking is risky in more ways than just losing the resources that go into rent seeking. More specifically, the risk of public scandal reduces the nominal return of political investment in a way that cannot be avoided without incurring non-trivial transaction costs. Rent seeking with no appeal to the public interest risks angering the public in a way that could more than offset any gains made through government support. Amazon’s recent cancellation of its plans to build a second headquarters in New York City due to public backlash at the local level over the $3 billion in public subsidies it secured through rent seeking would seem to be a case in point (see Soper 2019).

As was first noted by Yandle (1983, 1999) rent seekers can lower the risks associated with their activities if they can frame them in a manner that has social, rather than private, interest at heart. Yandle discovered through his experiences as an FTC regulator that supposed moral (aka ‘Baptist’) concerns put forward by special interest groups were more often than not accompanied by self-interested economic (aka ‘Bootlegger’) interest groups as well. These Bootlegger interest groups could be quite effective in redirecting policy towards their interests at the expense of their competitors when they can either frame their arguments in a Baptist manner, or form coalitions with Baptist groups. The framing and coalitions involved in the politics over protectionist trade policies provide a good example. For example, Hillman (2019, p. 469) discusses how protectionist trade policies are likely to be more successful when they are framed as protecting jobs from foreigners rather than improving the profitability of (i.e., rents obtained by) the domestic industry; while Hillman and Ursprung (1992, 1994) explore how coalitions with environmental groups also help secure special-interest trade policies.

Our unique contribution to the literature is examining the intersection of this political risk and different domains of regulation. Brito and Dudley (2012, p. 8–9) offer the following rationale for the dividing regulation into two domains:

“We often divide regulations into two main categories: social regulations and economic regulations. Social regulations address issues related to health, safety, security, and the environment. The EPA, Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the FDA, and the DHS are examples of agencies that administer social regulations. Their activities are generally limited to a specific issue, but they also have the power to regulate across industry boundaries… Economic regulations are often industry-specific. The SEC, the FCC, FERC, and the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) are examples of agencies that administer economic regulations. Economic regulation usually governs a broad base of activities in particular industries, using economic controls such as price ceilings or floors, production quantity restrictions, and service parameters.”

We argue that rent seeking is riskier in the domain of economic regulation, as opposed to social regulation where interest groups are more capable of creating moral cover. That is to say, assuming interest groups have a higher likelihood of avoiding public backlash within the domain of social regulation, this would imply that social regulation provides interest groups with greater opportunities to procure public support at the margin, at least up to the point where interest groups are no longer able to develop appropriate moral cover. More precisely and succinctly, empirically we expect to find that political action has a higher marginal influence on social regulations than economic regulations. Interestingly despite the large literature on rent seeking (see Congleton et al. 2008 or Congleton and Hillman 2015 for overviews) there has been a neglect of how the process, and its productivity, may differ between social and economic regulations.

To test our hypothesis, we employ data from the Center for Responsive Politics (OpenSecrets.org) on campaign contributions and direct lobbying efforts, which they report by industry from 1998–2012. We then match this data with data from the regulatory database, RegData, which provides an annual measure of the quantity of federal regulations that target specific industries, for the same years. We divide these regulations into “economic” and “social” categories, based on data from the George Washington University Regulatory Center, which previously assigned these labels according to the regulatory agency responsible for the promulgation of regulations. This allows us to test for the relative influence of each regulatory channel with the division being economic and social categories being pre-determined in advance for us. The paper proceeds by first giving additional background on the prior literature and building the logic of our empirical argument drawing on the Bootlegger & Baptist framework.

2 The risk of rent seeking

The term ‘rent-seeking’ most commonly refers to the expenditure of resources by groups or individuals (usually via special interest groups) to influence the outcomes of public policy in order to generate above-market returns, otherwise known as “rent” (see Tollison 1982). Public policy can greatly influence the rents earned by affecting costs, revenues, incomes, and/or profitability in the private sector. This is what Wagner (2016) refers to as the “peculiar business of politics,” one that alerts both political and market entrepreneurs to potential profit opportunities (even if profit is not always measurable in strictly pecuniary terms). Yet by all accounts, the measurable actions of groups to influence public policy, at least in pecuniary terms, is far less than the amount expected based on the level of government spending and involvement in the overall economy (see Stratmann 2005).

Tullock (1972) originally brought attention to this discrepancy in a short comment on campaign finance entitled, “The Purchase of Politicians.” Tullock’s question was simple: given the enormous level of government spending, why is the corresponding level of investment in procuring government benefits trivial by any measurement?Footnote 6 Put more plainly, why are interest groups not investing more in this lucrative public enterprise (see Wagner 2007)? Many scholars in the Public Choice tradition have attempted to address Tullock’s puzzle. One important aspect explored by Ursprung (1990) and Hillman and Ursprung (2016), among others including Tullock himself, is that rent seeking is basically involves private provision and effort to produce a collective (public-good type) benefit, which results in ‘under’ investment due to free-riding type incentives; although the exact nature of the ‘under’ dissipation and the social losses depends on whether the rents are divisible (see Long and Vousden 1987) and the sharing rules employed by the groups (see Ursprung 2012).

There are, however, many other explanations such as high fixed costs of successful lobbying, consumptive preferences of donors, market power on the side of both rent-seekers and politicians, indirect costs such as providing policy analysis and marketing materials, not to mention the potential for rent extraction by government.Footnote 7 Even Tullock himself offered a variety of explanations including that firms may be forced to adopt inefficient technologies by the politicians with whom they are bargaining (see Tullock 1989). He discusses examples in agriculture, airlines, and dockyards where firms were forced to invest in inefficient technologies as part of the rent-seeking agreement.Footnote 8 Since this adoption increases the costs to these firms, Tullock surmises that this could potentially overwhelm any profit unique to rent seeing directly, which helps to explain why we do not see more of it.Footnote 9

While our argument involves the risk of public exposure and backlash in this relationship, the prior literature has also used risk aversion over the outcome to explain the lack of rent seeking. Hillman and Katz (1984, p. 104–105) argue “in the face of uncertainty rent seekers may quite reasonably be risk averse, and, if this is so, individual rent seekers will allocate less to a particular rent seeking quest than the expected value of the gain from the activity.” This general notion of risk can be reflected in the rent-seeking process itself.Footnote 10 Hillman and Riley (1989, p. 18–19) note groups may have different (asymmetric) valuations of the risk that can change how interest groups compete for rents as a “larger value assigned to the political prize by a rival is a barrier to entry for lower-valuation contenders.” By way of example, Aidt (2003) incorporates a non-trivial investment special interest groups must make in order to participate in the rent-seeking process. A novel result of this model is that greater competition among groups does not unequivocally reduce deadweight losses.Footnote 11 This non-intuitive outcome follows from the premise that there are certain forms of redistribution that are inherently unattractive to would-be beneficiaries (such as those that invite public scandal) and so do not warrant political investment by those that would challenge this arrangement. To be clear, what makes certain redistribution methods unattractive is not specified by their model, though it does draw out the relevance of public opposition to certain forms of redistribution.

The public backlash needed to expose rent seeking could itself, in theory, be subject to the same collective good problems. Nevertheless, the resources needed to publicly challenge policy outcomes are far less than the resources needed to mount a major lobbying effort. Denzau and Munger (1986) call attention to the possible antagonism of ‘unorganized interests’; that is, voters who have not organized into a formal interest group yet have an indelible impact on the decision-making of lawmakers. Political constituents can present grievances through readily accessible channels such as opinion polls, social media, and town hall meetings.Footnote 12 This threat of scandal carried out through unorganized opposition can create enough negative feedback to discourage a would-be rent seeker. The reason these unorganized interests are still effective is because “even if voters are currently ignorant of the activities of a legislator in serving an interest group, the legislator’s actions may be constrained by the knowledge that the media or a competitor will expend resources to make voters aware. That is, the legislator must consider not only the reaction of voters given their present knowledge, but also the expected reaction if voters were to find out” (p. 101).Footnote 13 With the rise of social media in particular, the cost of rallying and mounting negative public opinion has fallen dramatically and is a much easier route for the public to influence the political process and discipline rent seekers and politicians.

We argue below that a Baptist component may be necessary to avoid this public opposition; this constitutes a non-trivial transaction cost that would also limit the number of viable rent seekers. As Shogren (1990, p. 182) explains “Therefore, in regulatory episodes that are controversial, there is an incentive for the rent-seeking bootleggers to subsidize the actions of the public-interest Baptists. The subsidy would provide an indirect moral avenue for rent-seeking behavior, thereby lowering the political costs of supporting the regulation.” What makes the avoidance of public scandal special is that is that it cannot be remedied through resource allocation alone. That is to say, it requires a specific asset in the form of moral cover generated by the Baptist component. Without this resource, the threat of public backlash could overwhelm the gains procured through rent seeking.

In a sense, rent-seeking organizations that lack a readily available moral counterpart are constrained by the political process itself. As Congleton (1991, p. 66) explains, “In polities where voting matters, ideology is both a constraint on the rent-seeking domain and an element of that domain.”Footnote 14 Even if these groups are able to gain political influence and move their efforts through the legislative process, they still face the risk of arousing angry voters. Ursprung (1990, p. 130–131) partly captures this constraint when noting that “Underdissipation has been associated with public good characteristics of politically contestable rents. The analysis shows that in this case the Olsonian free-riding considerations of the individual rent-seekers give rise to an under-dissipation which is compatible with the observed facts.” He further suggests how voters that innately resist long-term public expenditures that provide privately appropriable rents by observing “societies endowed with a public image which renders these activities impossible are more likely to survive than societies indulging in rent-seeking for private goods.”

As Congleton et al. (2008, p. 55) observe “it bears noting that the public arguments of economic interest groups rarely directly mention their own economic stakes or those of voters. Rather, political campaigns tend to use arguments based on the interests that voters have in a more attractive society, which usually reflects implications of broadly shared norms and ideology.” What furnishes these norms is beyond the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, if moral arguments for the public interest must be provided, then it follows that some domains of regulation may be favorable to interest group influence than others.

3 Bootleggers, Baptists, and social regulation

To reiterate our central claim, interest groups that attempt to utilize the political process for the purpose of rent seeking face the added burden of packaging their efforts in a manner palatable to the public interest, which should manifest itself more readily in social regulations than economic regulations. Yandle (1999, p. 5) himself explains “[d]urable social regulation evolves when it is demanded by both of two distinctly different groups. ‘Baptists’ point to the moral high ground and give vital and vocal endorsement of laudable public benefits promised by a desired regulation. Baptists flourish when their moral message forms a visible foundation for political action. ‘Bootleggers’ are much less visible but no less vital. Bootleggers, who expect to profit from the very regulatory restrictions desired by Baptists, grease the political machinery with some of their expected proceeds.”

In writing on the deluge of social regulations that emerged in the 1960 s and 1970 s in the United States, Vogel (1988, p. 569) notes, “Economic regulatory agencies govern prices, output, terms of competition, and entry exit. Social regulations are concerned with the externalities and social impact of economic activity.” Or as Aidt (2016, p. 147) puts it, “Un-internalised and socially harmful externalities provide a prima facie case for government intervention and a benevolent government would want to impose a correction.”Footnote 15 Regulation in areas such as health care, environment, civil rights, and poverty reduction are more clearly tied to the public interest compared to areas like export subsidies, corporate taxes, and securities trading.Footnote 16 And most voters surely support making life easier for the poor or improving the environment.Footnote 17 This isn’t to say that there are no controversies or debates with social regulations, only that moral appeal to public interest is more salient to voters (and associated scholars) in this domain of regulation.Footnote 18

Because social regulation provides this moral smokescreen, the ‘Bootleggers and Baptists’ framework implies that political influence will be easier to attain at the margin. That is to say, acquiring moral cover should be easier when talking about the environment, for example, than corporate finance reform.Footnote 19 Furthermore, because economic regulations are more likely to generate private gain (or at least be perceived as such), they are in turn subject to greater risk of exposure for rent seekers.Footnote 20 By comparison, social regulations that more obviously generate both private and social gains are less risky for would-be rent seekers. The appearance of social gains in particular makes it difficult for opposition to effectively assign self-interested motives to the would-be rent seeker.

Consider the data on constant dollar outlays for the two categories of regulation for selected years from 1960 to 2010 shown in Table 1, from Dudley and Warren (2011, p. 5).

The decade-over-decade growth of expenditures for social regulation outstripped economic regulation expenditures in all but one decade (see also Lipford and Slice 2007 for a useful comparison of these categories). Note that total social regulation spending increased more than 19 times from 1960 to 2010, while spending on economic regulation increased less than 7 times. By 2010 the spending of social regulation agencies was five times the size of economic regulation agencies. Total government spending for all federal activities increased nearly four-fold across the same 50 years (Office of Management & Budget 2011, p. 26).

This historical trend of a larger increase in social regulation relative to economic regulation has been addressed in prior literature most notably Weidenbaum (1977), Lilly and Miller (1977), and Miller and Yandle (1979) who pioneered the study of the “new” social regulation that occurred in this era. Empirically, Williams and Matheny (1984) provide several explanations for this growth in social regulations including the possibility of market failure, capture by special interest group, symbolic political entrepreneurship, and bureaucratic mission creep. Their empirical results in the case of hazardous waste removal suggests political influence in reducing the private costs involved in the waste removal process but weak empirical support for industry capture overall in influence regulation at the state level. In addition, the costs and benefits of social regulation are often harder to measure (or estimate) than for economic regulation, which may result in their being more easily distorted in the political process in ways to support their implementation.

Despite the large literature on rent seeking and the prior work on the expansion in social regulation relative to economic regulation, our conjecture that rent seeking may fundamentally be a different process for social regulation than economic regulation has not been formally recognized in prior literature on the subject. Our hypothesis is that because of the risks of rent seeking in regard to private gain, political action may impact these two types of regulation differently. If our hypothesis that social regulation expands more easily with regard to political activities than economic regulations, it may also help to explain why over the past 5 decades with the rising amount of lobbying activity that the growth of social regulation has outpaced economic regulation. We now turn to examining this hypothesis directly.

4 Model and empirical framework

Politicians who supply political favors and the rent seekers who demand it face significant risk without moral cover to hide their self-serving efforts. When it comes to assessing the value of rent seeking to the firm, we must consider not only the production costs of pursuing this activity, which itself would depend on the objective of the regulatory activity,Footnote 21 but the implicit costs that reflect the risk should the public become alerted. Together, these costs form the overall cost structure of gaining rents through the political process. It is our argument that social regulation has lower implicit costs (a far lower potential hazard for the firm and for the politician supplying the favors) and so will be the more effective form of rent seeking at the margin. Restated for succinctness, once these implicit costs are incorporated into the analysis, we would predict that the relative gains from social regulation increase.Footnote 22

It is possible to more formally model the impact this has on the political marketplace, as we have shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1 contains two supply curves and two demand curves. Supply curve S1 represents the political cost for delivering units of regulation when there is no moral story that can be used to justify the action, such as with economic regulation. Politicians can obviously make deals with their colleagues to get the votes for a special bill, but it takes more logrolling effort when the bill is simply about a raw transfer of wealth from consumers to producers (see Peltzman 1976). Once moral cover is provided, though, the supply curve increases from S1 to S2, reflecting the fact that it is easier to pacify the public, reducing the expected risk-adjusted political cost.

The figure also contains two demand curves. Demand curve D1 represents a Bootlegger firm’s demand for regulation with no moral cover such as with economic regulation. Again, the curve is less elastic than the demand for social regulation as represented by D2, because the former type of regulation is accompanied by the risk of alerting the public to blatant attempts at rent seeking. Anticipation of these implicit costs makes demand for these types of regulation less elastic to production costs alone (as represented on the y-axis). The figure thus shows two equilibrium levels of regulation produced. Q1 obtains when economic regulation alone is available, and firms are unable to take the moral high ground. Q2 obtains when the politician can package the deal in a socially conscious manner while distributing wealth from consumers to producers.

Shogren (1990) provides a similar model in which Bootleggers and Baptists interact in a way that allows for Bootleggers to directly subsidize Baptist activity. According to his model, “measuring rent-seeking behavior may be impossible since all activities are directly funneled through the Baptists” (p. 185). To be sure, rent seeking can be obstreperous to observe and quantify in practice (see Del Rosal 2011). The trouble with measuring rent seeking, beyond agreeing on what activities are inherently wasteful see (Lopez and Pagoulatos 1994), is that influencing political outcomes by use of economic resources is not a wholly public (or always legal) enterprise and so is not subject to rigorous documentation.Footnote 23 As a consequence, any empirical attempt to measure rent seeking must assume certain structural parameters with respect to the nature of the political process.Footnote 24,Footnote 25

In our case, we use both campaign contributions and lobbying expenditures. This allows us to examine whether social regulations as a group respond differently to these political activities when compared with economic regulations, which we assume is due to the greater amount of Baptist protection available to them.Footnote 26 Demand elasticities of regulation with respect to rent-seeking efforts offer direct measures of this responsiveness, a fact which allows us to set up our estimations.

We start by modeling social regulations (RS) and economic regulations (RE) as functions of political activities—lobbying (L) and campaign contributions (C)—and all other factors (A):

We are agnostic about the direction of effect of political activities on economic regulation; special interest groups or lobbyists could, in our view, be working against or for the creation of new economic regulations. While rent-seekers could lobby for the creation of regulations that deliver rents to themselves, more generally any firm could lobby against the creation of regulations that are proposed by politicians (or other firms) that might harm them. Social regulation, alternatively, has a clearer direction as the moral cover is almost universally in favor of expanded social regulations, suggesting this effect should be positive, and show a higher elasticity than economic regulation.

We are forthright about the possibility of reverse causality, particularly with respect to lobbying. As Congleton (2018, p. 3) explains “politicians may threaten to reduce a monopolists’ profits by allowing other firms to enter the market, raising taxes, or increasing regulatory costs unless campaign contributions are made or kickbacks are paid.” Or as Murphy et al. (1993, p. 409) succinctly puts it, “rent-seeking may be self-generating in that offense creates a demand for defense.” That is to say, lobbyists could be working to prevent regulation, and by extension reduce or eliminate existing regulation. In either case, we would expect the creation (or threat of creation) of new regulations to lead to more lobbying. Furthermore, should a rent-seeker succeed in lobbying for new regulations, she may need to continue lobbying in future years in order to prevent the elimination of those rent-producing regulations. In short, several plausible arguments for reverse causality exist. Absent any plausible instrumental variable, we proceed with an exploratory analysis of the data and rely on the examination of long-term trends to attempt to rule out possible reverse causality.

In addition, note that our theory is not entirely dependent on the direction of causality. Our arguments hold in part even if the causality is reversed. Rent extraction shows that the threat of regulation encourages political influence to counteract it; therefore, if groups want to reduce the risk of public backlash, they may feel obligated to put pressure on government to reduce future regulatory burden. Thus, even if our results are subject to reverse causality, the correlation is what matters in either direction to substantiate the presence of risk. Also note that our utilization of campaign contributions as one measure of political activities engaged in by rent-seekers is much less likely to suffer from this causal uncertainty as campaigns go in cycles, and it is unlikely that the regulation would precede the campaign contribution meant to influence it.

5 Data, results, and robustness checks

To gauge the level of rent-seeking pursued by individual industries, we use data from The Center for Responsive Politics (OpenSecrets.org) on lobbying expenditures from 1998 to 2012 and campaign contributions from 1995 to 2012. To determine how these measures relate to regulations, we use the regulation index provided in the Mercatus Center’s RegData database. RegData 2.2 provides a panel dataset measuring regulation by industry and year from the period 1975 to 2012. We categorize each regulatory agency’s regulations into “economic” and “social” categories, based on Regulators’ Budget data from the George Washington University Regulatory Studies Center, which assigns these labels according to the regulatory agency responsible for regulations’ promulgation.

Unfortunately, the industry breakdown offered by The Center for Responsive Politics (OpenSecrets.org) does not follow the breakdowns provided by the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), which is a standard division of industries and also the one used by RegData. Their industry breakdown is described as follows:

The Center uses a hierarchical coding system to classify contributions by industry and interest group. At the top level are 13 sectors—ten covering business groups and one each for ‘labor,’ ‘ideological/single-issues,’ and ‘other.’ At the middle level are about 100 industries, more detailed than the broad sectors. At the most detailed level are more than 400 categories.”Footnote 27

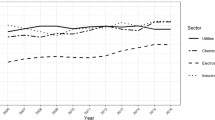

We thus relied on industry descriptions to map the industries between the two data sets. We focus on the middle level (or industry level) for political activities in our study because this is the most detailed level for which we have corresponding industries to match RegData. Our data permit a decomposition into political-action-by-industry and regulation-by-industry variables, yielding a panel dataset of 29 industries annually from 1998 to 2012. Because the attempt to influence the political and regulatory process is a long term game, we consider the cumulative effects of political activities—that is, we consider the running total of these activities. These political activities are denoted as cumulative_lobbying_expenditures and -cumulative_campaign_contributions in our tables and discussion. Figures 2 and 3 show the time series of cumulative_lobbying_expenditures and cumulative_campaign_contributions for all industries in our dataset.

For our regulation-by-industry variables, we first collected the total number of restrictions produced by each agency in each year from RegData 2.2. Second, we also collected the probability that each agency’s regulatory text in each year was relevant to each industry in our Opensecrets data. Following a probabilistic risk assessment approach suggested by Al-Ubaydli and McLaughlin (2017), we consider the risk of a regulation having consequences to an industry to be the probability that an agency’s regulatory text is targeting an industry (denoted as agency_industry_probability) multiplied by the consequence of that targeting, which for which use the proxy, regulatory restrictions (denoted as agency_restrictions). Finally, we combined agency_restrictions and agency_industry_probability by multiplying the two for each unique agency-industry combination in each year. Thus, an observation is an agency’s industry-specific regulations in a year; in other words, regulation is observed at the agency-industry-year level. We denote this variable as regulation.

All variables are logged in order to produce elasticity estimates. We performed Levin-Lin-Chu tests for panel data unit root processes on our measure of regulation and our political action variables (ln_cumulative_lobbying_expenditures and ln_cumulative_campaign_contributions) and are all found to be stationary. However, tests for autocorrelation reveal the presence of serial correlation. Other tests showed some heteroscedasticity issues. Neither of these revelations is particularly surprising, because we are working with panel data. We can estimate standard errors that are robust to both autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity, a procedure that we describe later. Table 2 gives descriptive statistics for our variables.

Our primary interest lies in the difference in responsiveness to political activities between different types of regulators. The Regulators’ Budget categorizes several (but not all) agencies into a narrow set of groups. Two of these groups are economic regulators and social regulators. An agency cannot be both economic and social in their categorization. We therefore include in our analysis all agencies that were categorized as either economic or social, and because they are mutually exclusive, we code these two groups into a single dummy variable, economic. In other words, in our data, economic is a dummy variable where a value of 1 indicates that the regulator is an economic regulatory, and a value of 0 indicates that the regulator is a social regulator.

Table 4 lists the regulators included in our data and the number of observations we have for each regulator. Each observation is the year-to-year difference in the Regulation Index from RegData 2.2 for a specific agency-industry pair.

Economic regulators | Obs. | Social regulators | Obs. |

|---|---|---|---|

Agricultural marketing service (standards, inspections, marketing practices), department of agriculture | 1127 | Animal and plant health inspection service, department of agriculture | 1127 |

Board of governors of the federal reserve system | 1127 | Architectural and transportation barriers compliance board | 1126 |

Bureau of consumer financial protection | 61 | Bureau of alcohol, tobacco and firearms, department of the treasury | 1127 |

Bureau of export administration, department of commerce | 1122 | Bureau of alcohol, tobacco, firearms, and explosives, department of justice | 592 |

Commodity futures trading commission | 1127 | Bureau of customs and border protection, department of homeland security; department of the treasury | 592 |

Comptroller of the currency, department of the treasury | 1127 | Bureau of safety and environmental enforcement, department of the interior | 120 |

Copyright office, library of congress | 1127 | Chemical safety and hazard investigation board | 710 |

Farm credit administration | 1127 | Coast guard, department of homeland security | 592 |

Federal communications commission | 1127 | Coast guard, department of transportation | 1127 |

Federal deposit insurance corporation | 1127 | Consumer product safety commission | 1127 |

Federal election commission | 1127 | Corps of engineers, department of the army | 1127 |

Federal financial institutions examination council | 1126 | Council on environmental quality | 1127 |

Federal housing finance board | 1121 | Defense nuclear facilities safety board | 1111 |

Federal maritime commission | 1127 | Department of homeland security (immigration and naturalization) | 533 |

Federal trade commission | 1127 | Department of homeland security, homeland security acquisition regulation (hsar) | 533 |

Financial crimes enforcement network, department of the treasury | 120 | Drug enforcement administration, department of justice | 1127 |

International trade administration, department of commerce | 1126 | Employment standards administration, department of labor | 948 |

National credit union administration | 1127 | Environmental protection agency | 1127 |

National indian gaming commission, department of the interior | 1111 | Equal employment opportunity commission | 1127 |

National telecommunications and information administration, department of commerce | 1122 | Federal aviation administration, department of transportation | 1127 |

Office of thrift supervision, department of the treasury | 1121 | Federal emergency management agency, department of homeland security | 592 |

Patent and trademark office, department of commerce | 1127 | Federal highway administration, department of transportation | 1127 |

Securities and exchange commission | 1127 | Federal mine safety and health review commission | 1126 |

United states international trade commission | 1127 | Federal motor carrier safety administration, department of transportation | 828 |

Federal railroad administration, department of transportation | 1127 | ||

Food and drug administration, department of health and human services | 1127 | ||

Food safety and inspection service, department of agriculture | 1126 | ||

Forest service, department of agriculture | 1127 | ||

geological survey, department of the interior | 1127 | ||

Grain inspection, packers and stockyards administration (federal grain inspection service), department of agriculture | 1127 | ||

Mine safety and health administration, department of labor | 1127 | ||

Minerals management service, department of the interior | 1067 | ||

National highway traffic safety administration and federal highway administration, department of transportation | 1127 | ||

National labor relations board | 1127 | ||

National transportation safety board | 1127 | ||

Nuclear regulatory commission | 1127 | ||

Occupational safety and health Administration, department of labor | 1127 | ||

Occupational safety and health review commission | 1127 | ||

Office of federal contract compliance programs, equal employment opportunity, department of labor | 1127 | ||

Office of surface mining reclamation and enforcement, department of the interior | 1126 | ||

Office of workersÂ’ compensation programs, department of labor | 122 | ||

Pension and welfare benefits administration, department of labor | 1127 | ||

Research and special programs administration, department of transportation | 1127 | ||

Surface transportation board, department of transportation | 1005 | ||

Transportation security administration, department of homeland security | 177 | ||

United states fish and wildlife service, department of the interior | 1127 | ||

Total observations of economic regulators: | 24,935 | Total observations of social regulators: | 44,455 |

As hinted at earlier, we took precautions against heteroscedasticity and serial correlation affecting our variance estimates. In all regressions reported, we implemented heteroscedasticity-and-autocorrelation robust estimators using the ivreg2 command in Stata (Baum et al. 2007). This command implements the Newey-West (Bartlett kernel function) estimator to correct the effects of correlation in the error terms caused by either autocorrelation or heteroscedasticity in panel data (Newey and West 1987). The bandwidth on the kernel function was chosen optimally using the selection criterion of Newey and West (1994).

Once again, our primary hypothesis is that social regulations will be more positively responsive to lobbying activities and campaign contributions than other regulations. We examine the relationship between the year-to-year changes in political activities by an industry (i.e., the first-difference of cumulative lobbying expenditures or cumulative campaign contributions) and the level of regulation of the industry. We estimate the elasticities on political activities by including an interaction term indicating whether the observed regulations are from a social regulatory agency and a vector of control variables, X. Because regulations take up to 1 year from their promulgation to be formally published in the Code of Federal Regulations, we lag our political activity variables by 1 year:

and:

where Δ indicates a first-differencing operator, X is a vector of control variables, and \( b_{0} , \;b_{1} , \)\( b_{2} , \) and \( \varvec{\gamma} \) are all parameters to be estimated.

We consider these relationships in five separate models. The models progressively include more control variables in the vector X. The first model is the simplest, where we include no controls and simply estimate the coefficients b0, b1, and b2. In the second model, we introduce real GDP as a control variable. The third model includes industry fixed effects as well as real GDP, while the fourth model includes year dummy variables on top of industry fixed effects and real GDP. Finally, in the fifth model, we include real GDP, industry fixed effects, year dummy variables, and agency fixed effects.

Table 3 gives our results for Eq. (2), where, where cumulative lobbying expenditures is the primary variable of interest. Table 3 shows the results of each of the five different models in separate columns.

In all five models shown in Table 3, the coefficient on the interaction term, socialXln_cumulative_lobbying_exp, is positive and significant, indicating that social regulations are more positively responsive to lobbying expenditures than economic regulators. Because these are elasticities, one can conclude that, ceteris paribus, for an equal sized increase in lobbying expenditures by an industry, the activities of social regulatory agencies expand by 17.8 to 22.0 percentage points greater than for economic regulatory agencies. One possible way to look at this result is that garnering influence with social regulatory agencies is roughly 80 percent the cost of garnering the same level of influence with economic regulatory agencies.

The positive coefficients on the ‘social’ dummy shows that social regulation is larger in each year and industry independent of political activities, while the negative coefficient on ln_cumulative_lobbying_exp by itself, because of the interaction term, really reflects the impact of lobbying on economic regulatory agencies alone. Consistent with the idea of rent extraction, lobbying efforts seem to be associated with a lower level of economic regulation for an industry. While this result has implications for the direction of causality, again our hypothesis of sensitivity to risk is confirmed regardless of the direction of the causality if the elasticity coefficients are greater for economic than social regulation as is illustrated by the interaction term.

Table 4 examines the same set of models, except that campaign contributions are the political activity variable, rather than lobbying expenditures. Because the data on campaign contributions dates back to 1994, we have more observations in our regressions than we had in those shown in Table 3.

The results in Table 4 are virtually identical to those in Table 3 with regard to our main variable of interest. There is again a positive and significant interaction term showing a higher elasticity of social regulation to political activity than for economic regulation. The coefficient is smaller, suggesting a marginal difference in elasticity of 3.96 to 5.04 percentage points, but it remains positive. Thus a given increase in campaign contributions by an industry, again controlling for industry fixed effect, year effects, and agency effects, results in a greater political impact on social regulations than on economic regulations.

As a final empirical test, we pooled all the data into one sample this time using a dummy variable to separate differences in the relationship between the lobbying and campaign spending variables and social regulations compared to their relationship with economic and other regulations. These results are presented in Table 5.

Because of the high degree of multicollinearity between lobbying and campaign contributions at the industry level, we are less confident in these results as the two measures of political activity contain some similar, but not identical, information. Across all specifications the coefficients on both interactions remain positive, although the significance levels disappear in some of the specifications that do not include the fixed effects to control for industry, year, or agency differences. However, in the fully specified model in the final column, the results remain consistent with our prior findings—social regulations show a higher elasticity with respect to political activity than do economic regulations, for both measures of political activity.

To summarize our overall findings, we hypothesized that social regulations would be more responsive to political influence than economic regulations; this was based on the assumption that risk is reduced in the domain of social regulations due greater access to ‘moral’ Baptist cover. We found this framework indeed aids us in describing our empirical results as social regulations are more responsive to political influence than economic regulations (or total regulations). We also found political influence in general to have a negative influence on economic regulation, which is consistent with the notion of rent extraction in that lobbying is undertaken by groups who wish to avoid regulation.

6 Conclusion

Shogren (1990, p. 188) claims the Baptist factor makes “it difficult to empirically identify rent seeking from public interest behavior. Consequently, the true extent of rent-seeking in the regulatory arena may well be underestimated.” We agree. By calling attention to the implicit risk of rent-seeking, we maintain that government influence can be quite dangerous to groups (and politicians) caught in the act of procuring private benefits without sufficient moral cover. Interest groups that openly attempt to hijack the political process face the risk of being awarded with public outcry and condemnation.

To test our argument on the necessity of moral cover and the easier path to political influence it provides, we compared the relationship between influence and regulatory outcome across two categories of regulation. While the two categories of ‘economic’ and ‘social’ regulations at best approximate the different propensities for special interest groups to acquire moral cover, at the margin we expect this to be more readily available in the domain of social regulation. This is where the public is least likely to suspect self-interested machinations, which makes it a doubly pernicious form of rent-seeking, and therefore most likely to elicit Bootlegger/Baptists activity. Our results confirm this, indicating that political influence is most effective at generating social regulations.

By wrapping self-interested machinations in moral trappings, interest groups increase the viability of their attempts at influence. Still, moral cover doesn’t come cheap. Our argument can be extended to show the precarious nature of government influence in general. As far as we can tell, there is no ‘standard’ manner in which to acquire moral cover. Smith and Yandle (2014) explore a range of dynamics between Bootlegger/Baptist interactions, with the only general conclusion being that having sufficient moral cover increases the chances of political influence. Put another way, the ‘Baptist’ component serves as a peculiar sort of political transaction cost that groups must pay to gain political influence. Further attention to the moral dimension of political influence is surely warranted. It may be that access to moral cover is constrained by non-pecuniary factors. After all, if Baptists could be simply bought and sold, they wouldn’t really be Baptists, would they?

Notes

See Smith et al. (2011) for a more detailed account of this episode.

This is not to say that Occupy Wall Street was universally supported, only that enough lingering animosity remained to generate a notable political movement almost a full 2 years after the initial event.

Langer (2010). Citizens United Poll: 80 Percent Of Americans Oppose Supreme Court Decision. The Huffington Post (Apr 19) http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/02/17/citizens-united-poll-80-p_n_465396.html. Accessed April 5, 2019.

Seitz-Wald (2012). "Everyone Hates Citizens United." Salon. http://www.salon.com/2012/10/25/people_really_hate_citizens_united/. Accessed April 5, 2019.

Long and Vousden (1987) explain how this risk may be overcome through sharing rents.

The estimated total for campaign spending when Tullock wrote the article in 1972 was around $200 million, while simultaneously hundreds of billions of dollars were available through public expenditures and anti-regulatory efforts (see Ansolabehere et al. 2003, p. 110).

The idea that government may pressure firms to spend money fighting regulatory influence is discussed below. If true, this would only deepen the conundrum as firms should be even more willing to spend money towards political influence in order to avoid public backlash.

In a common example of adopting inefficient technologies at the local level, the NC Board of Governors “discussed a ‘buy local’ resolution that would require UNC colleges to favor North Carolina venders and products for capital projects, like new building construction and renovating existing ones” (see Hennan 2018).

Hillman and Ursprung (2016, p. 130) expand upon this point in the context of manipulating voters, noting that “because of requisites of political accountability, governments engage in purposefully inefficient income redistribution to take advantage of voter ignorance.” The resulting deadweight losses incurred represent the costs associated with keeping voters docile and ignorant of rent seeking. This is consistent with our claim below that there is an implicit moral (or ‘Baptist’) dimension to rent seeking that must be addressed if legislative efforts are to be successful. .

For example, Godwin et al. (2006, p. 40) model this element by having policymakers face a cost N of providing the rent, itself informed by the policy environment. They argue, “Public perception may help to determine N if it involves a policy that would attract substantial negative media attention to the policymakers.” Their model indicates that firms will seek out policymakers with a low enough N in order to entice an otherwise reluctant policymaker into the fold. However, greater pressure from other would-be competitors can reduce the marginal investment in political influence.

Long and Vousden (1987) arrive at a similar conclusion when rents are shared across groups. Mitigation of risk in particular can increase overall lobbying efforts.

As Hopenhayn and Lohmann (1996, p. 208) explain “A political principal who suffers an informational disadvantage vis-a-vis a regulatory agency can nevertheless use information supplied by the media, interest groups, and constituents to monitor whether the agency is acting in her best interests.”

Mixon et al. (1994, p. 172) further expand upon this fear of public backlash, noting “overt bribes attract attention and invited regulation, although rent seeking investments will take place even where cash bribes are costly.”.

He further adds, “Political ideologies normally include a notion of the good society towards which the actual, naturally imperfect, society should move.”.

Aidt (2016, p. 150) notes that “the degree of rent dissipation is much larger with private than with public-good rents.”.

Smith and Yandle (2014) discuss at length both types of rent seeking, focusing on social regulation in areas such as alcohol, tobacco, environmental, and health care. They find abundant evidence of rent seeking through social regulation where firms utilize Bootlegger/Baptist coalitions to avoid public outcry.

For example, “In a Pew Research Center survey conducted last year, about three-quarters of U.S. adults (74%) said ‘the country should do whatever it takes to protect the environment,’ compared with 23% who said “the country has gone too far in its efforts to protect the environment.” (see Anderson 2017). .

Hillman and Ursprung (2016, p. 127) distinguish Tullock’s contributions from Becker (1983, 1985) in modeling the costs of rent seeking noting “Becker’s conclusion was more favorable to an ideology that sees merit in extensive income redistribution.” As a further example MacKenzie (2017, p. 145) explains “In the mainstream environmental economics literature, the objective of regulation has been specified as the maximization of social welfare.”.

More recent regulatory activity originating with the efforts of Senator Elizabeth Warren (see Bar-gill and Warren 2008) and culminating in the founding of the Consumer Protection Financial Bureau would seem to belie this assumption. It’s certainly true that Senator Warren has brought greater public scrutiny to an otherwise obscure section of the regulatory landscape. See Smith and Zywicki (2015) for an analysis of the somewhat unique regulatory structure of the CFPB.

And as Tullock (1983, p. 165) explains within the context of farm special privileges “An asset that is held at risk is one in which one must put considerable resources into defending.”.

For example, it may be that activity meant to influence social regulation is less expensive to produce as it relies more heavily on voluntary efforts. This would only increase the relevant returns to the Bootlegger rent-seeking organization and accordingly make social regulations more worth securing (see Lipford and Yandle 2009).

Eventually, of course, gains from social regulation would diminish too as more firms utilize this type of rent seeking. Indeed, in theory, at the margin, the returns should equalize across economic and social regulatory capture, at least as a long-term equilibrium state. This assumes though that the total level of regulation is itself fixed. While we do not test this hypothesis, our reading of the background literature suggests that the size and scope of government is itself a potential variable of influence by special interest groups (see Olson 1982).

Congleton (2018, p. 10) notes “The direct sale of public policies is often illegal, because it tends to harm or violate social norms important to voters or other critical supporters.” Hillman and Long (2018, p. 7) reinforce this argument explaining “The resources used in a contest are not generally observable. Moreover, successful rent seekers will in general attribute their rents to their effort and competence, rather than to their success in rent seeking.”.

For example, Mixon et al. (1994) attempt to locate rent seeking by comparing the number of sit-down restaurants and public golf courses located in state capitals to other cities with similar income characteristics. Sobel and Garrett (2002) follow this thread by comparing a number of industries that would be necessary to generate rent-seeking activity such as printing services, billboard advertising, radio and television broadcasting, and policy institutes. The trouble in is that “other reasonable factors such as the administrative costs of government and its agencies” would also account for the presence of these industries (p. 130).

Aidt (2016, p. 143) describes this as ‘the invertibility hypothesis’ in that by “applying contest theory and assumptions about the behavior of rent seekers, the size of the social cost can be inferred from the value of the contestability rent.”.

Our framework also implies that production costs are equal across the two regulatory fronts. If social regulation is less expensive to pursue as we suggested in the above footnote, then its empirical presence would only serve to further validate our overarching hypothesis.

The Center for Responsive Politics. (2017). Opensecrets RSS. Combined Federal Campaign of the National Capital Area. http://www.opensecrets.org/industries/slist.php. Visited August 5, 2017.

References

Aidt, T. S. (2003). Redistribution and deadweight cost: the role of political competition. European Journal of Political Economy, 19(2), 205–226.

Aidt, T. S. (2016). Rent seeking and the economics of corruption. Constitutional Political Economy, 27(2), 142–157.

Al-Ubaydli, O., & McLaughlin, P. A. (2017). RegData: A numerical database on industry-specific regulations for all United States industries and federal regulations, 1997–2012. Regulation & Governance, 11(1), 109–123.

Anderson, M. 2017. For Earth Day, here’s how Americans view environmental issues. Pew Research Center http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/04/20/for-earth-day-heres-how-americans-view-environmental-issues/. Accessed April 5, 2019.

Ansolabehere, S., de Figueiredo, J. M., & Snyder, J. M. (2003). Why is there so little money in US politics? The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17, 105–130.

Bar-Gill, O., & Warren, E. (2008). Making credit safer. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 157, 1–101.

Baum, C. F., Schaffer, M. E., & Stillman, S. (2007). Enhanced routines for instrumental variables/generalized method of moments estimation and testing. The Stata Journal, 7(4), 465–506.

Becker, G. S. (1983). A theory of competition among pressure groups for political influence. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 98, 371–400.

Becker, G. S. (1985). Public policies, pressure groups, and dead weight costs. Journal of public economics, 28, 329–347.

Brito, J., & Dudley, S. E. (2012). Regulation: A primer. Arlington: Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

Congleton, R. D. (1991). Ideological conviction and persuasion in the rent-seeking society. Journal of Public Economics, 44(1), 65–86.

Congleton, R. D. (2018). The Political Economy of Rent Creation and Rent Extraction. In R. D. Congleton, B. N. Grofman, & S. Voigt (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of public choice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Congleton, R. D., & Hillman, A. L. (2015). Companion to the political economy of rent seeking. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Congleton, R. D., Hillman, A. L., & Konrad, K. A. (2008). Forty years of research on rent seeking: fan overview. The Theory of Rent Seeking: Forty Years of Research, 1, 1–42.

Del Rosal, I. (2011). The empirical measurement of rent? Seeking costs. Journal of Economic Surveys, 25(2), 298–325.

Denzau, A. T., & Munger, M. C. (1986). Legislators and interest groups: How unorganized interests get represented. The American Political Science Review, 80, 89–106.

Dudley, S., & Warren, M. (2011). Fiscal statement reflected in regulators’ budget: An analysis of the U.S. budget for fiscal years 2011 and 2012. Wiedenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy. St. Louis: Washington University.

Godwin, R. K., López, E. J., & Seldon, B. J. (2006). Incorporating policymaker costs and political competition into rent-seeking games. Southern Economic Journal, 73, 37–54.

Hennan, A. 2018. The Quizzical Case of UNC’s “Buy Local” Resolution. The James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal: https://www.jamesgmartin.center/2018/03/quizzical-case-uncs-buy-local-resolution/. Accessed April 15, 2018.

Hillman, A. L. (2019). Public finance and public policy: responsibilities and limitations of government (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hillman, A. L., & Katz, E. (1984). Risk-averse rent seekers and the social cost of monopoly power. The Economic Journal, 94(373), 104–110.

Hillman, A. L., & Long, N. V. (2018). Rent seeking: the social cost of contestable benefits. In R. D. Congleton, B. N. Grofman, & S. Voigt (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of public choice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hillman, A. L., & Riley, J. G. (1989). Politically contestable rents and transfers. Economics and Politics, 1(1), 17–39.

Hillman, A.L. & Ursprung, H.W. (1992). The influence of environmental concerns on the political determination of trade policy. The greening of world trade issues, p. 195–220.

Hillman, A. L., & Ursprung, H. W. (1994). Greens, supergreens, and international trade policy: Environmental concerns and protectionism. In C. Carraro (Ed.), Trade, innovation, environment (pp. 75–108). Dordrecht: Springer.

Hillman, A. L., & Ursprung, H. W. (2016). Where are the rent seekers? Constitutional Political Economy, 27(2), 124–141.

Hopenhayn, H., & Lohmann, S. (1996). Fire-alarm signals and the political oversight of regulatory agencies. The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 12(1), 196–213.

Issacharoff, S., & Peterman, J. (2013). Special interests after citizens united: Access, replacement, and interest group response to legal change. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 9, 185–205.

Langer, G. 2010. Citizens united poll: 80 percent of Americans oppose supreme court decision. The Huffington Post http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/02/17/citizens-united-poll-80-p_n_465396.html. Accessed April 5, 2019.

Lilly, W., & Miller, J. C. (1977). The new social regulation. The Public Interest, 47, 28–36.

Lipford, J. W., & Slice, J. (2007). Adam Smith’s roles for government and contemporary US government roles. The Independent Review, 11(4), 485–501.

Lipford, J. W., & Yandle, B. (2009). The determinants of purposeful voluntarism. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 38(1), 72–79.

Long, N. V., & Vousden, N. (1987). Risk-averse rent seeking with shared rents. The Economic Journal, 97, 971–985.

Lopez, R. A., & Pagoulatos, E. (1994). Rent seeking and the welfare cost of trade barriers. Public Choice, 79(1), 149–160.

MacKenzie, I. A. (2017). Rent creation and rent seeking in environmental policy. Public Choice, 171(1–2), 145–166.

Miller, J. C., & Yandle, B. (Eds.). (1979). Benefit-cost analyses of social regulation: Case studies from the council on wage and price stability (Vol. 231). Washington: American Enterprise Institute Press.

Mixon, F. G., Laband, D. N., & Ekelund, R. B. (1994). Rent seeking and hidden in-kind resource distortion: some empirical evidence. Public Choice, 78(2), 171–185.

Murphy, K. M., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1993). Why is rent-seeking so costly to growth? The American Economic Review, 83(2), 409–414.

Newey, W. K., & West, K. D. (1987). A simple, positive semi-definite, heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent covariance matrix. Econometrica, 55, 703–708.

Newey, W. K., & West, K. D. (1994). Automatic lag selection in covariance matrix estimation. Review of Economic Studies, 61, 631–653.

Office of Management & Budget. 2011. Fiscal year 2012 historical tables, budget of the United States. http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2012/assets/hist.pdf. Accessed May 27, 2011.

Olson, M. (1982). The rise and decline of nations: Economic growth, stagflation, and social rigidities. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Peltzman, S. (1976). Toward a more general theory of regulation. Journal of Law and Economics, 19, 211–240.

Seitz-Wald, A. 2012. “Everyone hates citizens united.” Salon. http://www.salon.com/2012/10/25/people_really_hate_citizens_united/. Accessed April 5, 2019.

Shogren, J. F. (1990). The optimal subsidization of Baptists by Bootleggers. Public Choice, 67(2), 181–189.

Smith, A. C., Wagner, R. E., & Yandle, B. (2011). A theory of entangled political economy, with application to TARP and NRA. Public Choice, 148, 45–66.

Smith, A. C., & Yandle, B. (2014). Bootleggers and Baptists: How economic forces and moral persuasion interact to shape regulatory politics. Washington: Cato Institute Press.

Smith, A. C., & Zywicki, T. (2015). Behavior, paternalism, and policy: evaluating consumer financial protection. NYUJL & Liberty, 9, 201.

Sobel, R. S., & Garrett, T. A. (2002). On the measurement of rent seeking and its social opportunity cost. Public Choice, 112(1), 115–136.

Soper, S. 2019. Amazon scraps plan to build a headquarters in New York City. Bloomberg https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-02-14/amazon-says-it-won-t-build-a-headquarters-in-new-york-city. Accessed March 24, 2019.

Stratmann, T. 2005. Some talk: Money in politics. A (partial) review of the literature. In Policy challenges and political responses (pp. 135–156). Springer, New York.

The Center for Responsive Politics. 2017. Opensecrets RSS. Combined Federal Campaign of the National Capital Area. http://www.opensecrets.org/industries/slist.php Accessed January 27, 2017.

Tollison, R. D. (1982). Rent seeking: A survey. Kyklos, 35(4), 575–602.

Tullock, G. (1967). The welfare costs of tariffs, monopolies, and theft. Economic Inquiry, 5(3), 224–232.

Tullock, G. (1972). The purchase of politicians. Western Economic Journal [Economic Inquiry], 10, 354–355.

Tullock, G. (1983). Economics of income redistribution. Berlin: Springer.

Tullock, G. (1989). The economics of special privilege and rent seeking. Alphen aan den Rijn: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Ursprung, H. W. (1990). Public goods, rent dissipation, and candidate competition. Economics and Politics, 2(2), 115–132.

Ursprung, H. W. (2012). The evolution of sharing rules in rent seeking contests: incentives crowd out cooperation. Public Choice, 153(1–2), 149–161.

Vogel, D. (1988). The ‘new’ social regulation in historical and comparative perspective (p. 431). American Law and the Constitutional Order: Historical Perspectives.

Wagner, R. E. (2007). Fiscal sociology and the theory of public finance: An exploratory essay. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Wagner, R. E. (2016). Politics as a peculiar business: Insights from a theory of entangled political economy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Weidenbaum, M. L. (1977). Business, government and the public. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Williams, B. A., & Matheny, A. R. (1984). Testing theories of social regulation: Hazardous waste regulation in the American states. The Journal of Politics, 46(2), 428–458.

Yandle, B. (1983). Bootleggers and Baptists—The education of a regulatory economist. Regulation, 7, 12.

Yandle, B. (1999). Bootleggers and Baptists in retrospect. Regulation, 22, 5.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McLaughlin, P.A., Smith, A.C. & Sobel, R.S. Bootleggers, Baptists, and the risks of rent seeking. Const Polit Econ 30, 211–234 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-019-09278-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-019-09278-2