Abstract

Some people with mental illness in China do not receive treatment. We explored how stigma and familial obligation influenced accessibility of social support for patients with depression in China and the potential acceptability of peer support programs. Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with five psychiatrists and 16 patients receiving care for depression from a large psychiatric hospital in Jining, Shandong Province of China. Patients with mental illness reported barriers that prevented them from (a) receiving treatment and (b) relying on informal social support from family members, including stigma, somatization, and community norms. Circumventing these barriers, peer support (i.e., support from others with depression) was viewed by patients as an acceptable means of exchanging information and relying on others for support. Formative research on peer support programs to examine programming and activities may help reduce the burden of unmet mental health care needs in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The true prevalence of mental illness in China is unknown. In the early 2000s, prevalence of mental illness was estimated to be 17% and as many as 92% of individuals with mental disorders in China had never sought any type of professional help for their disorder (Phillips et al. 2009). While more recent data are not available, the health care system, like many around the world, does not provide extensive mental health services. Less than 2.35% of the government’s health budget is spent on mental health, which has resulted in a shortage of specialized services, a limited number of physicians trained in mental health care, and inadequate insurance coverage for treatment of psychiatric disorders (Phillips et al. 2009; Yang et al. 2013). Moreover, because the current health system focuses mental health services on those with schizophrenia and organic disorders (not including dementia or Alzheimer’s), less attention is given to those with other psychological problems, such as depression, which still represent a major burden (Phillips et al. 2009). In addition to these structural barriers, stigma against those with mental illness in China and the rest of Asia is high (Lauber and Rössler 2007).

Instead of seeking treatment, those with mental illness often turn to support from family members in China (Chien et al. 2007). Social support has been associated with a number of positive outcomes across a variety of health conditions (Berkman and Glass 2000; Holt-Lunstad et al. 2010; House et al. 1988; Uchino 2004). However, studies have found that patients with mental illness in China may not receive as much familial support as those without mental illness (Wang and Zhao 2012). Support may be effortful or difficult for family members to provide. For instance, studies reveal that family members in China report a lowered quality of life as a result of their care-giving role (Li et al. 2007; Mak and Cheung 2008). Family members may also experience “affiliate stigma”, whereby they too experience stigma from others because of their connections with close loved ones with mental illness (Li et al. 2007; Mak and Cheung 2008). These factors may make individuals reluctant to burden others with mental health concerns and suggest that a diagnosis of depression has very real consequences on patient’s ability to access social support, especially within the family.

In recognition of the growing need for mental health services, the Chinese Ministry of Health partnered with other sectors of the government in 2002 to create the National Mental Health Project of China to enhance treatment of mental illness (Kelly 2007). One of the key goals of this initiative was to shift detection and care of mental illnesses from the inpatient hospital setting to a community health center based model of ongoing care, which mirrors current global goals in the mental health sector (Kelly 2007). While peer support interventions provided by community health workers (Chowdhary et al. 2016; Patel et al. 2007; Patel and Thornicroft 2009), “Lady Health Workers” in Pakistan (Rahman et al. 2008), or those with other names have demonstrated beneficial mental health effects in various countries and populations, it is unclear how such a model would work in China, given the unique features of the health care system and considerations surrounding social support and mental health.

Over the past decade, a growing number of peer support programs have been successfully implemented and evaluated in China. For instance, Zhong et al. developed a peer leader-support program for individuals with diabetes in Anhui Province. Qualitative evaluations from patients, peer leaders, clinical staff, and administrators indicated the program to be acceptable and feasible (Zhong et al. 2015). Findings also illustrated that in the two sites where the peer leaders were implemented, significant improvements occurred for patients’ knowledge, self-efficacy, body mass index, and other clinical indicators. Similarly, in Jingzhou, patients with diabetes who were randomly assigned to receive peer support achieved a more significant decrease in A1c compared to a control group (Deng et al. 2016). In addition to diabetes, other peer support programs have been developed in China to increase walking among older adults (Thomas et al. 2012) and decrease psychological distress among individuals with HIV (Molassiotis et al. 2002). Lastly, Tse et al. developed a training curriculum for peer support workers within the mental health system in Hong Kong (Tse et al. 2014). While these programs demonstrate the potential acceptability of peer support programs in China, no in-depth investigations, to our knowledge, have examined the acceptability or potential of peer support for individuals with mental illness, as well as the unique concerns of these individuals.

In light of the considerations discussed above, the present study was conducted to determine (1) how stigma and affiliate stigma create barriers to social support for those with depression in China and (2) the potential acceptability of peer support programs to provide supportive care for individuals with depression.

Methods

Setting and Approach

Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with five psychiatrists and 16 patients with depression from several wards at Ankong Psychiatric Hospital in Jining, China over a 1-month period in 2011. Located in Shandong Province, which is on the eastern edge of the North China Plain, Jining has approximately eight million residents and is primarily an industrial city. SY conducted the interviews who was at the time a student in the MPH program in the Department of Health Behavior of the Gillings School of Global Public Health at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill (UNC). SY, GL, and EF designed the study as a qualitative descriptive study (Sandelowski 2000, 2010). These types of studies aim to develop a comprehensive summary of events that stays true to the data. Researchers using this type of approach seek descriptive validity (an accurate accounting of events that most people observing the event would agree is accurate) and interpretative validity (an accurate accounting of meanings participants attributed to those events). A number of researchers have used qualitative descriptive studies to understand and explore phenomena (Milne and Oberle 2005; Neergaard et al. 2009; Sullivan-Bolyai et al. 2005). Approval for this project was obtained from the UNC Institutional Review Board and consent was obtained from participants prior to enrollment in the study.

Interview Instrument

Semi-structured interviews were organized to cover specific topics but questions were asked in an open-ended and flexible manner in order to probe participants’ perspectives and experiences (Patton 2005). All interview guide questions were created and revised based on experts’ familiar with peer support and the Chinese context. Psychiatrists were interviewed about their perceptions of social support available to patients and the impacts of stigma on care received by patients. Patients were interviewed about their experiences with depression, support received from family, friends, and health care teams, barriers to seeking care, and acceptability of different support options, including peer support.

Data Collection

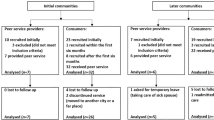

Psychiatrists and patients were recruited using informal snowball sampling. At the judgment of one of the authors (SY) and based on a few key informants with information about the topic who could then provide names of additional potential participants (Patton 1990), we identified a pool of psychiatrists and patients with depression. Of the five psychiatrists and 16 patients participating in this study, 12 were men, ranging in age from 16 to 64. All patients were receiving care for depression and had been hospitalized for care. All psychiatrists were employees of the hospital involved in direct patient care. Patient interviews were conducted in clinical offices without other patients present to ensure privacy. In addition to semi-structured interviews, observational data were collected at the inpatient wards and focused on patients’ interactions with each other, family members, and hospital staff.

Data Analysis

Each interview lasted approximately 30–60 min and was conducted in Chinese by the first-author, who was raised in the US by ethnic Chinese parents, acquiring near fluency in spoken Chinese. Principles from thematic analysis, which searches for important themes that emerge related to the phenomena of interest, were used to guide data analysis (Boyatzis 1998). A single member of the research team (SY) reviewed all interviews and field notes to create analytic memos and matrices on key concepts, phrases, questions, and patterns. Analytic memos became the basis for emergent themes identified in the data. To maximize precision, other members of the research team reviewed the notes and analytic memos and discussions were held to clarify ideas and refine themes. Data analysis occurred in an iterative fashion, in that data were analyzed while data collection was still ongoing in order to identify emergent themes to be explored in subsequent interviews. With an initial goal of 5–20 patient interviews, no new interviews were concluded after 16 had been completed and no new themes were emerging, indicative of saturation. We declare no conflict of interest and certify responsibility for the manuscript.

Results

Emergent Themes

Four main themes emerged from the interviews: (1) stigma surrounding depression and mental illness, (2) the importance of family dynamics in seeking and receiving support for depression and mental illness, (3) misperceptions of depression and mental illness, and (4) the potential of alternative care models (e.g., peer support) in circumventing barriers to seeking mental health care. These themes are discussed below and illustrated through participants’ quotes.

Stigma- The Impact of Being Seen As “Bu Zheng Chang”

Stigma against the mentally ill has resulted in their exclusion from professional and social opportunities. According to patient interviews, people with depression and other mental illnesses are perceived as being “bu zheng chang” or abnormal by community members. When asked to describe this term, patients used words such as “incapable”, “crazy”, or “unfit”. These perceptions of the mentally ill have led to discrimination in the workplace and limited opportunities for marriage and other social relations.

Fear of Stigma

The repercussions of being labeled as “bu zheng chang” have led patients with depression to hide their mental health status from everyone but close family members. One patient revealed that no one knew that she was currently in a psychiatric hospital - not even her own son. She simply told friends and family members that she was going on vacation. This patient has been struggling with depression for the past 20 years in secret. As a business owner, she was fearful that customers and business associates would view her as an incapable entrepreneur if they learned of her mental health status.

Another reason this patient did not disclose her mental health status was that she was afraid of the impact of the stigma on her son’s future prospects. Although fear of being stigmatized is present in cultures around the world, it is complicated by kinship ties in Chinese culture. Stigmatization extends beyond the individual to include family members. Many community members see mental illness as a genetically transferrable trait. As a result, a family history of depression decreases the marriageability not only of the individual who is diagnosed but also the other members of their family. In this particular community, marriage is still handled in a very traditional manner in which matches (“dui xiang”) are made through a thorough evaluation of a potential mate and his or her family. Patients with depression, therefore, feel pressured to keep their mental health status a secret for their own sake and for the sake of their family members. This makes support seeking behaviors difficult and sometimes obstructs continued care upon discharge. For example, the parents of a young patient stopped giving her medication when she was discharged because they wished to hide her illness from parents and families of potential spouses.

Familial Dynamics and Their Impact on Patients’ Perceptions of Themselves

Mutual Obligation

The fear of burdening their families with the stigma of mental illness is illustrative of the kinship ties that bind patients with their families in a relationship of mutual obligation. Shielding their family members from the shame of stigmatization was the patients’ way of taking care of their family. Family members take care of the patients by staying by their bedside, bringing them food at the hospital, paying for the hospital bills, and accompanying them to office visits. Patients have cited all of these acts as forms of support provided by their family members. Interviews with psychiatrists revealed that family members play a very active role in patient care. They are the ones that answer questions about patients’ daily activities and are usually the first ones to spot that “something is wrong with the patient.”

These acts depict the relationship of reciprocity that underlies familial relations. Everyone has a role and duties that benefit the entire family. These roles shift throughout the life cycle, but each member’s duties are integral to the wellbeing and function of the family unit. These duties are evident in patients’ descriptions of themselves when prompted about their feelings towards their illness. They described feelings of guilt at being unable to fulfill their duties to their families, which included taking care of their parents or grandchildren or earning a steady income. One female patient with post-partum depression reported feelings of guilt at her lack of ability to fulfill her maternal duties and said she “wanted her husband to find her child a good mother”. Evidence of these familial obligations is also evident from reports from psychiatrists who encouraged patients towards recovery by reminding them of their obligations to family members or the toll that their illness was taking.

Patients have explained that the guilt they feel is a result of having to be taken care of, draining resources from the family, and being incapable of contributing by fulfilling their duties. The combination of these factors leads patients to view themselves as burdens to their family or as “can fei” (invalids). The term “can fei” refers to a person who is incapable of contributing and is closely tied with another term- “fan tong,” which literally translates to a rice bucket and figuratively refers to someone who is lazy. There are many cultural taboos and stigma against being perceived as lazy. Therefore, patients in China are struggling against two very distinct stigmatizations- that of being mentally ill and that of being perceived as “can fei”. The fear of being seen as a “can fei” by family and community members leads patients to minimize their symptoms. A male patient with depression spoke of how his father’s care for him “broke his [father’s] heart” because it caused him so much worry. The female patient who was a business woman and a mother described the painstaking efforts she took to hide her illness from her son so that he would not be burdened by the knowledge.

Misperceptions of Mental Illness

The fear of becoming a “can fei” is the result of misperceptions about the nature of mental illness in the community. Specifically, it is a widely held belief that depression and mental illness are solely the result of an individual’s “bad thinking” and “dwelling on bad thoughts” rather than a problem resulting from complex interactions among genetic, psychological, and social influences. When asked about how community and family members have shown their support, patients responded that they were encouraged to “think right” and “not dwell on bad thoughts.” This illustrates the popular opinion, even among patients themselves, that mental illness can be controlled through willpower alone. The inability to recover, therefore, is due to personal flaws and weaknesses. This thought contributes to the conception of the mentally ill as “can fei” and “fan tong”- burdens to society due to their laziness. Again, this leads patients to minimize their psychological symptoms. It was not uncommon for patients to deny feelings of depression and focus, instead, on somatic symptoms such as fatigue and generalized pain because these were more acceptable and legitimate. Often patients seek care from general hospitals or traditional Chinese clinics and are referred to professional care at these points.

Talking with Other Patients: A Different Kind of Conversation

When asked about how they spent their time in the hospital, patients said they talked to each other. While the topics of these conversations varied, the feeling behind them remained constant. Specifically, patients said that they felt “wu shuo wei” or that it “didn’t matter”. While it may sound negative, this expression actually conveys a level of comfort. One patient said of conversing with other patients, “We are all sick, so it really doesn’t matter. There are no feelings of ‘oh, he is better than me’, or feelings of shame. We are all patients.” This statement is remarkable in comparison to the usual hesitancy that patients express about communicating with other people, especially about their illness. Disclosures about medications, moods, and symptoms are discussed casually throughout the ward among patients. The usual reserve that patients have about discussing such matters seems to have evaporated in an atmosphere where they perceive others to be like themselves and with whom there is not a sense of obligation as exists among family members. When asked about information that they would like to give to others like themselves, patients responded that they wanted to share their stories and demonstrate that the illness can be overcome, that it is “not their fault”, and that “normal” people can become sick. These responses illustrate the unique role that peer support might play. While some of this information can be obtained elsewhere, patients also wanted to hear it from their peers.

Interest in Peer Support Programs

It should be noted that “tong ban zi ci,” literal translation of “peer support,” is a formal term that sounds intimidating to lay persons. In all interviews, the term had to be first explained to patients. Patients often expressed a hesitancy to engage in “tong ban zi ci” or peer support activities, especially outside of the hospital because they were afraid community members would find out about their mental illness. However, when asked if they would participate in activities such as exercising or playing cards with one another, patients were open to the concept. This suggests that it is the formality of the term itself as well as the idea of discussing their problems in an environment outside of the safety of the hospital that cause patients hesitation. When the activity was shifted from discussions about illness to more common or general activities and outings, patients were eager to suggest ideas for the types of activities that might be developed, including shopping, going to the park, and playing card games. Moreover, since patients were already more comfortable disclosing, engaging, and interacting with other patients with mental illness than family members, friends, or community members, our findings suggest the further acceptability of peer support.

Discussion

Qualitative interviews with and observations of patients and psychiatrists at a psychiatric hospital in China indicated that substantial barriers prevented patients from (a) receiving medical treatment for depression and (b) relying on informal social support from family members. Specifically, these barriers included stigma associated with mental illness, the importance of family obligations and concern about burdening family members with problems and misperceptions of mental illness as the result of individual’s actions and beliefs. Circumventing these barriers, peer support was viewed by patients as a way of speaking about their mental illness and receiving support from others without fear of repercussion on support systems. Implications for research and practice for mental illness in China are discussed below.

Stigma and Mental Health

Mehta and Thornicroft (2013) summarized the global character of stigma surrounding mental illness as follows: “There are few countries, societies, or cultures in which people with mental illness are considered to have the same value as people who do not have mental illness. Consistent findings describing the existence of stigma have emerged from evaluating stigma in Africa, Asia, South America, North America, in Islamic countries of North Africa and the Near East, Australasia, and Europe” (p. 406). Mehta and Thornicroft go on to identify three principle components of stigma: ignorance (e.g., 63% in a population survey thought fewer than 10% of people experience mental illness during their lives), prejudice, and discrimination (including policies that directly or indirectly limit opportunities and access to care) (Mehta and Thornicroft 2013). Clearly all three apply to the mental health research in China. Previous research has shown that stigma and misperceptions of the origins of mental illness in China can cause individuals to minimize psychological concerns and prevent them from receiving formal care (Ip et al. 2015; Yang 2007). Indeed, in different areas of China, mental illness has been considered a punishment for an ancestors’ misbehavior, a result of malevolent spiritual forces, and a consequence of a breakdown in family relationships (Phillips et al. 2002). The result is that the symptoms of many with mental illness may present as physical concerns, such as generalized pain or fatigue, and go unrecognized and untreated. Work by Kleinman and colleagues have documented that somatization is more prevalent in Chinese culture than other settings, such as the United States, so that in one study, as many as 70% of patients presenting at clinic with somatic complains were found to suffer from mental illness (Katon et al. 1984; Kleinman 1977). The result is a high burden of mental illness in China that is not addressed by the current mental health care system.

Barriers to Seeking Informal Familial Support

In addition to barriers that prevent individuals from seeking professional help, patients also expressed concerns about burdening family members with their illness. These barriers have been well documented in previous research. In a review on culture and social support, researchers found that Asian and Asian Americans are more reluctant to ask for support than European Americans because they are afraid of burdening others with problems or concerns (Kim et al. 2008). The authors hypothesized that this pattern of not wanting to burden family members results from the collectivist culture in Asia, where the cultural assumption is that individuals “should not burden their social networks and that others share the same sense of social obligation” (Kim et al. 2008, p. 519). Moreover, not only do Asians seek less social support (than for instance European Americans), they may also seek support in qualitatively different ways (e.g., seeking emotional comfort from one’s social network, referred to as “implicit support”, rather than disclosing stressful events and asking for help, known as “explicit support”) (Kim et al. 2008). Empirical evidence supports these observations. For instance, in a study of Chinese individuals living with HIV, researchers found that implicit support positively predicted mental health, not explicit support (Yang et al. 2015). The result has been lower documented social support and family functioning among individuals with mental illness in China compared to individuals without mental illness (Wang and Zhao 2012). Thus, despite the fact that families are an important source of support for mental illness, the high burden placed on family members to support patients with mental illness coupled with patients’ fears of burdening those with their illness may leave patients without adequate support systems.

Acceptability of Peer Support

Often implemented in community-based settings, peer support programs have been shown to be effective in improving depressive symptoms compared to usual care (Pfeiffer et al. 2011) and useful for individuals with mental health conditions (Rebeiro Gruhl et al. 2016). “Peer support” refers to support provided by non-professionals familiar with a patient’s disease condition and community. Although patients were initially wary to engage in “tong ban zi ci” or peer support activities because they were afraid community members would find out about their mental illness, they were open to informal support activities, such as exercising or playing cards with one another. This suggests that peer support may be an important source of support for this population for two reasons.

First, patients may feel more comfortable sharing with peer supporters than family members or other professionals. Indeed, some studies have found that peer support is beneficial when patients are reluctant to ask for support for fear of burdening others with problems or concerns (Fisher et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2006). Second, peer support allows patients to engage in “implicit support” activities whereby they can receive emotional comfort from their peers without explicitly discussing stressful events or discussing problems. Studies have demonstrated that the desire and utility of implicit vs. explicit support depends on context (Kowitt et al. 2015) and that implicit support may be especially protective for mental health among individuals in China (Yang et al. 2015).

Implications for Further Research on Peer Support Programs

The findings from the present study suggest that peer support may be able to circumvent some of the barriers preventing patients with mental illness from seeking support from health care professionals and family members. Indeed, a demonstration study of mutual support groups for patients with schizophrenia and their families in China has shown promising results (Chien et al. 2007) and some community-based mental health pilot programs are currently underway (Zhao et al. 2015). However, recommendations for program development go beyond the data presented here. We therefore offer considerations for further formative evaluation when designing and implementing peer programs in China. Importantly, these considerations are merely suggested topics for further research; any organization or group seeking to develop a peer support program should tailor their own formative evaluation and/or needs assessment to their own context, setting, and population.

-

Formative evaluation could assess the degree to which informal activities and implicit support strategies, such exercise groups, playing cards, or other outings, should be incorporated into peer support programs. A model for this is a peer support program for diabetes in Anhui province in China that included these kinds of informal activities among participants (Zhong et al. 2015).

-

Formative evaluation could assess the ideal setting for peer support programs (e.g., community-based or not) and facilitators of such programs (e.g., peer leaders or health care professionals), taking into consideration patients’ reluctance and hesitancy to seek professional care and treatment for mental health concerns and because of the stigma associated with receiving care for mental illness. Importantly, regardless of setting, additional research could examine how best to protect participants’ identities and reasons for engaging with peer support, given patients’ concerns that other community members may find out about their mental illnesses.

-

Relatedly, researchers or practitioners could examine if or how participants would like to disclose their experiences with mental illness with other participants (e.g., should this emerge organically in conversation or through some other means?)

-

Formative evaluation could examine how to structure peer support programs (e.g., by age, sex, or other affinity characteristics, such as shared interests, neighborhood, etc.). Although not explored in these interviews, it is possible that patients’ comfort levels of participating in peer support programs may be maximized when they are surrounded by others with whom they share characteristics.

-

Formative evaluation could help determine the role of family members for all participants and settings. While it is undeniable that family members are a great source of support for patients, their inclusion and the degree of participation in peer support activities should be examined in future studies. As this study demonstrates, patients often feel guilty for being ill and minimize their symptoms. The presence of family members at peer support activities, therefore, could inhibit open discussions about mental illness.

Conclusions

While the findings of this formative study suggest that peer support programs could be beneficial to patients with depression, it was conducted with a small sample of patients in a rural region of China. Nevertheless, the current findings provide a base for initial studies of peer support interventions that might emphasize implicit support through shared activities in community settings. Specifically, patients and psychiatrists from different wards of an inpatient hospital in the Shandong Province spoke of barriers to receiving treatment for depression, concerns about burdening family members and affiliate stigma, and willingness to speak with peers about mental illness. These findings suggest that formative research could be conducted for peer support programs for depression in China examining (1) the setting (i.e., non-clinical, community-based), (2) the extent of informal activities and implicit support as a means of showing care and building supportive networks, and (3) the importance of confidentiality to protect against stigma.

Change history

04 January 2018

The original version of this article unfortunately contained a mistake in “Funding” section. The funding information for Dr. Li is missing in the original publication. The corrected Funding section is given below:

References

Berkman, L. F., & Glass, T. (2000). Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. Social Epidemiology, 1, 137–173.

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage

Chien, W. T., Chan, S. W., & Morrissey, J. (2007). The perceived burden among Chinese family caregivers of people with schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16(6), 1151–1161.

Chowdhary, N., Anand, A., Dimidjian, S., Shinde, S., Weobong, B., Balaji, M., … Patel, V. (2016). The Healthy Activity Program lay counsellor delivered treatment for severe depression in India: systematic development and randomised evaluation. British Journal of Psychiatry, 208(4), 381–388. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.161075.

Deng, K., Ren, Y., Luo, Z., Du, K., Zhang, X., & Zhang, Q. (2016). Peer Support training improved the glycemic control, insulin management, and diabetic behaviors of patients with Type 2 diabetes in rural communities of central China: A randomized controlled trial. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research, 22, 267–275.

Fisher, E. B., Ballesteros, J., Bhushan, N., Coufal, M. M., Kowitt, S. D., McDnough, M., … Sokol, R. (2015). Key Features of Peer Support in Chronic Disease Prevention and Management. Health Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0365.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316.

House, J. S., Landis, K. R., & Umberson, D. (1988). Social relationships and health. Science, 241(4865), 540–545.

Ip, V., Chan, F., Chan, J. Y., Lee, J. K., Sung, C., & Wilson, E. H. (2015). Factors influencing Chinese college students’ preferences for mental health professionals. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England). https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2015.1057328.

Katon, W., Ries, R. K., & Kleinman, A. (1984). The prevalence of somatization in primary care. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 25(2), 208–215.

Kelly, T. A. (2007). Transforming China’s mental health system: Principles and recommendations. International Journal of Mental Health, 36(2), 50–64.

Kim, H. S., Sherman, D. K., Ko, D., & Taylor, S. E. (2006). Pursuit of comfort and pursuit of harmony: Culture, relationships, and social support seeking. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(12), 1595–1607.

Kim, H. S., Sherman, D. K., & Taylor, S. E. (2008). Culture and social support. The American psychologist, 63(6), 518–526. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.

Kleinman, A. M. (1977). Depression, somatization and the “new cross-cultural psychiatry”. Social Science and Medicine (1967), 11(1), 3–9.

Kowitt, S. D., Urlaub, D., Guzman-Corrales, L., Mayer, M., Ballesteros, J., Graffy, J., … Fisher, E. B. (2015). Emotional support for diabetes management: An international cross-cultural study. The Diabetes Educator, 41(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721715574729.

Lauber, C., & Rössler, W. (2007). Stigma towards people with mental illness in developing countries in Asia. International Review of Psychiatry (Abingdon, England), 19(2), 157–178.

Li, J., Lambert, C. E., & Lambert, V. A. (2007). Predictors of family caregivers’ burden and quality of life when providing care for a family member with schizophrenia in the People’s Republic of China. Nursing and Health Science, 9(3), 192–198.

Mak, W. W., & Cheung, R. Y. (2008). Affiliate stigma among caregivers of people with intellectual disability or mental illness. Journal of applied research in intellectual disabilities, 21(6), 532–545.

Mehta, N., & Thornicroft, G. (2013). Stigma, discrimination, and promoting human rights. In V. Patel, H. Minas, A. Cohen & M. J. Prince (Eds.), Global mental health: Principles and practice (pp. 401–424). New York: Oxford.

Milne, J., & Oberle, K. (2005). Enhancing rigor in qualitative description. Journal of Wound Ostomy and Continence Nursing, 32(6), 413–420.

Molassiotis, A., Callaghan, P., Twinn, S. F., Lam, S. W., Chung, W. Y., & Li, C. K. (2002). A pilot study of the effects of cognitive-behavioral group therapy and peer support/counseling in decreasing psychologic distress and improving quality of life in Chinese patients with symptomatic HIV disease. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 16(2), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1089/10872910252806135.

Neergaard, M. A., Olesen, F., Andersen, R. S., & Sondergaard, J. (2009). Qualitative description–the poor cousin of health research? BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9(1), 52.

Patel, V., Flisher, A. J., Hetrick, S., & McGorry, P. (2007). Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. Lancet, 369(9569), 1302–1313.

Patel, V., & Thornicroft, G. (2009). Packages of care for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in low-and middle-income countries. PLoS Medicine, 6(10), e1000160.

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd edn.). Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications, inc.

Patton, M. Q. (2005). Qualitative research. Hoboken: Wiley Online Library.

Pfeiffer, P. N., Heisler, M., Piette, J. D., Rogers, M. A., & Valenstein, M. (2011). Efficacy of peer support interventions for depression: A meta-analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 33(1), 29–36.

Phillips, M. R., Pearson, V., Li, F., Xu, M., & Yang, L. (2002). Stigma and expressed emotion: A study of people with schizophrenia and their family members in China. British Journal of Psychiatry, 181, 488–493.

Phillips, M. R., Zhang, J., Shi, Q., Song, Z., Ding, Z., Pang, S., … Wang, Z. (2009). Prevalence, treatment, and associated disability of mental disorders in four provinces in China during 2001–05: An epidemiological survey. Lancet, 373(9680), 2041–2053.

Rahman, A., Malik, A., Sikander, S., Roberts, C., & Creed, F. (2008). Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 372(9642), 902–909.

Rebeiro Gruhl, K. L., LaCarte, S., & Calixte, S. (2016). Authentic peer support work: challenges and opportunities for an evolving occupation. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 25(1), 78–86. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2015.1057322.

Sandelowski, M. (2000). Focus on research methods-whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health, 23(4), 334–340.

Sandelowski, M. (2010). What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in Nursing and Health, 33(1), 77–84.

Sullivan-Bolyai, S., Bova, C., & Harper, D. (2005). Developing and refining interventions in persons with health disparities: The use of qualitative description. Nursing Outlook, 53(3), 127–133.

Thomas, G. N., Macfarlane, D. J., Guo, B., Cheung, B. M., McGhee, S. M., Chou, K. L., … Tomlinson, B. (2012). Health promotion in older Chinese: a 12-month cluster randomized controlled trial of pedometry and “peer support”. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 44(6), 1157–1166. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318244314a.

Tse, S., Tsoi, E. W., Wong, S., Kan, A., & Kwok, C. F. (2014). Training of mental health peer support workers in a non-western high-income city: preliminary evaluation and experience. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 60(3), 211–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764013481427.

Uchino, B. N. (2004). Social support and physical health: Understanding the health consequences of relationships. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Wang, J., & Zhao, X. (2012). Family functioning and social support for older patients with depression in an urban area of Shanghai, China. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics, 55(3), 574–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2012.06.011.

Yang, G., Wang, Y., Zeng, Y., Gao, G. F., Liang, X., Zhou, M., … Naghavi, M. (2013). Rapid health transition in China, 1990–2010: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet, 381(9882), 1987–2015.

Yang, J. P., Leu, J., Simoni, J. M., Chen, W. T., Shiu, C. S., & Zhao, H. (2015). “Please Don’t Make Me Ask for Help”: Implicit Social Support and Mental Health in Chinese Individuals Living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1041-y.

Yang, L. (2007). Application of mental illness stigma theory to Chinese societies: synthesis and new directions. Singapore Medical Journal, 48(11), 977–985.

Zhao, W., Law, S., Luo, X., Chow, W., Zhang, J., Zhu, Y., … Wang, X. (2015). First adaptation of a family-based ACT model in Mainland China: A pilot project. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D. C.), 66(4), 438–441. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400087.

Zhong, X., Wang, Z., Fisher, E. B., & Tanasugarn, C. (2015). Peer support for diabetes management in primary care and community settings in Anhui Province, China. The Annals of Family Medicine, 13(Suppl 1), S50–S58.

Funding

Ms. Kowitt, Ms. Yu and Dr. Fisher were supported by Peers for Progress at the Gillings School of Global Public Health at the University of North Carolina. At the time the research was conducted, it was a program of the American Academy of Family Physicians Foundation, supported by the Eli Lilly and Company Foundation and the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, S., Kowitt, S.D., Fisher, E.B. et al. Mental Health in China: Stigma, Family Obligations, and the Potential of Peer Support. Community Ment Health J 54, 757–764 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-017-0182-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-017-0182-z