Abstract

The general factor of psychopathology (GP, or p factor) and the Dysregulation Profile (DP) are two conceptually similar, but independently developed approaches to understand psychopathology. GP and DP models and their stability, antecedents and outcomes are studied in a longitudinal sample of 1073 children (49.8% female). GP and DP models were estimated at ages 8 and 14 years using the parent-reported Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and Youth Self Report (YSR). Early childhood antecedents and adolescent outcomes were derived using a multi-method multi-informant approach. Results showed that the general GP and DP had similar key symptoms and were similarly related to early-childhood antecedents (e.g., lower effortful control, higher maternal depression) and adolescent outcomes (e.g., reduced academic functioning, poorer mental health). This study demonstrates that GP and DP are highly similar constructs in middle childhood and adolescence, both describing a general vulnerability for psychopathology with (emotional) dysregulation at its core. Scientific integration of these approaches could lead to a better understanding of the structure, antecedents and outcomes of psychopathology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Traditionally, child and adolescent psychopathology has mainly been conceptualized in terms of a two-dimensional structure of externalizing (i.e., aggression, attention problems) and internalizing (i.e., anxiety, depression) problems. However, externalizing and internalizing problems are highly correlated in childhood, reciprocally influence each other and specific etiology and outcomes for either are still poorly understood [1,2,3]. Recently, studies using confirmatory factor analysis have documented a ‘general psychopathology factor’ (GP, or ‘p factor’) that underlies the externalizing and internalizing spectra [4, 5]. Other factor-analytic studies yield similar results, highlighting the Dysregulation Profile (DP), composed of the most common symptoms of psychopathology from both the externalizing and internalizing spectrum [6,7,8]. Scales from the widely-used Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and Youth Self Report are often used as indicators for both GP and DP in young people, although GP generally is measured with a broader range of scales.

Despite many conceptual as well as statistical similarities, research and thinking about GP and DP developed independently. Determining whether—and how—they similarly define co-occurring psychopathology is important to advance understanding of the structure and etiology of psychopathology. One study estimated both GP and DP models in a sample of clinically referred children and adolescents, showing that both models can be estimated and that both are clinically meaningful constructs linked to self-harm and suicidality [8]. However, more evidence is needed to determine the similarity of GP and DP models. Therefore, after describing the origins, similarities, and differences of GP and DP, we evaluate these approaches (as depicted in Fig. 1) conceptually and statistically, using parent- and youth-reported symptoms in middle childhood and adolescence. By comparing the two models on a broad range of early-childhood antecedents and adolescent outcomes that have been linked to GP and/or DP in previous research, we aim to explore the extent to which the meaning, predictive validity and developmental appropriateness of GP and DP overlap or differ.

Origins of the General Factor of Psychopathology and the Dysregulation Profile

Observations that different forms of adult psychopathology are highly interrelated stimulated recent investigations of the underlying transdiagnostic structure of psychopathology leading to the emergence of the GP. Using a factor-analytic approach, commonly observed patterns of comorbidity were best described by a bifactor model, indicating that common associations between different domains of psychopathology could be explained by GP as well as by domain-specific externalizing and internalizing factors [4, 5]. The bifactor GP model has been tested against alternative models, including correlated-factors and one-factor models, and was found to best describe the structure of adult psychopathology [4, 5] as well as child and adolescent psychopathology [8,9,10,11,12].

In contrast to GP, research on DP originated in the study of child psychopathology, specifically, in efforts to identify childhood precursors of bipolar disorder [13]. DP reflects a profile of elevated scores on the Anxious/Depressed, Aggressive Behavior and Attention Problems syndrome scales of the widely used CBCL. No longer considered a proxy for bipolar disorder [14, 15], DP is now conceptualized as a broad syndrome of difficulties in regulating affect, behavior, and cognition [16]. This claim is consistent with research showing that a bifactor model also best describes the structure of DP [6,7,8].

Thus, GP and DP are similarly derived using bifactor models, in which general factors (GP or DP) exist over and above specific factors of internalizing (INT) and externalizing (EXT) difficulties in the GP model or anxiety/depression (AD), aggression (AGG), and attention problems (AP) in the DP model (see Fig. 1). Previous studies have demonstrated significant homotypic continuity (e.g., GP predicting GP at a later time point) as well as hetero-typic continuity (e.g., GP predicting later EXT and vice versa) (e.g., [17, 18]). For DP however, only homotypic continuity has been examined (and established) [19, 20]. A comparison of the stability of GP and DP is needed to determine which one would be more susceptible to developmental change.

Research linking GP or DP models to external correlates indicates that both are associated with a myriad of etiological correlates (e.g., family history of psychiatric disorder) and developmental consequences (e.g., self-harm, psychosocial problems, poor academic functioning) [4, 6, 7, 11, 21]. These associations emerge even when specific psychopathology factors are controlled for, or different informants are used. The specific factors in the GP and DP models show differentiated associations. This underscores the major advantage of bifactor models being positioned to disentangle common and unique dimensions of psychopathology, along with their common and unique risk factors and outcomes.

Concerns expressed about bifactor models include their tendency to show superior goodness of fit in model comparison studies, and several authors have stressed the need for validation [22, 23]. Extensive evidence of the criterion validity of both models, and further evidence that they do not reflect evaluation bias [24] however, reveals GP and DP bifactor models as meaningful and parsimonious ways of examining the etiology and consequences of psychopathology. In sum, both GP and DP models capture general vulnerability for developing psychopathology. Work into the meaning and underlying factors of both has pointed mostly to constructs related to self- and emotion-regulation, e.g., effortful control and negative affectivity [25, 26], poor constraint over reactions to emotion [27], emotional reactivity and irritability [6], and negative emotionality [24].

Notwithstanding the highly similar ways in which GP and DP models are derived, there are key differences in how they are operationalized, especially with regard to the content of the item domains and specific factors in the models. The extent to which these differences in specification affect these models is unknown. First, a broader range of scales and instruments and often a far larger battery of items are included in GP models [9, 28], while the DP is usually assessed with only three scales of either the CBCL or the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire [19]. It is unknown whether the size of the item battery affects predictive validity or whether DP, as a more parsimonious measure, might be just as useful. Further, although both models include symptoms from the externalizing and internalizing domains, there is no consensus regarding whether, and how, to handle attention problems. Although modeled as a specific latent factor within the bifactor DP model, in GP models attention problems are not included at all (e.g., [4, 11]) or are included as a part of the externalizing domain (e.g., [9, 21]). In one recent study symptoms of attention problems loaded on the GP factor directly rather than being subsumed in the externalizing factor, although, notably, the authors did not consider modeling attention problems as a specific factor [28]. Finally, thought-problem symptoms are only included in GP models, generally not as a unique factor but rather contributing directly to the general GP factor (e.g., [4, 9]).

In the present study, we extend work on the two models, as their core components, stability, potential early-childhood etiological factors, and outcomes in adolescence are evaluated within one study. Our overarching goal is to determine whether GP and DP approaches on the structure of psychopathology can be integrated.

Method

Participants

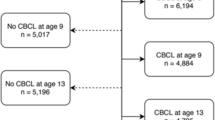

Participants were from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD), a diverse US longitudinal cohort study of children born in 1991. Parents were recruited through hospital visits, and 1364 participants with healthy newborns were enrolled in the study (for details see: https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/series/233). The SECCYD research protocol was approved by each of the 10 participating university’s ethical review boards. All participating families provided written informed consent at the start of the study. The current study included 1,073 participants (78.7% of the original sample) with psychopathology data available at age 8 or 14 years. Of this subsample, 49.8% (n = 534) were female, 81.6% (n = 875) were White, 8.2% of mothers did not complete high school and 19% were living in poverty.

Instruments and Measures

Symptoms of Psychopathology

The Achenbach System of Empirical Based Assessment (ASEBA; [29]) was used to assess symptoms of psychopathology with the parent-reported CBCL when children were 8 and 14 years of age and the YSR when the child was 14. The 1991-version of the CBCL was available for the 8-year old models, and the 2001-versions of the CBCL and YSR for the 14-year old models, but for all models the 2001-configuration was used to the extent possible. Mother-reported CBCL was available for 1026 participants at age 8 years and 975 at 14 years; 957 adolescents completed the YSR at age 14 years.

Antecedents and Outcomes

A range of antecedents pertaining to the child (e.g., temperament, executive functioning) and the family (e.g., parenting, maternal depression) from birth to 54 months was examined using mother- and teacher-reported questionnaires, observations, and laboratory tasks. Outcomes were assessed at age 15 and mainly youth-reported, and included measures of academic functioning, mental health, psychosocial outcomes and risk-taking. Given the large number of antecedents and outcomes included in this study, detailed information on the measurements as well as reliability measures in the current study are provided in Table A1 in the online supplements.

Statistical Analyses

Confirmatory Factor Analyses were conducted in Mplus 7.31 [30] using Weighted Least Squares Means and Variances adjusted estimator (WLSMV) with delta parameterization. Separate bifactor GP and DP models were estimated with the CBCL at ages 8 and 14 years and the YSR at age 14 years. Model fit was evaluated using the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). Values of RMSEA ≤ 0.06 and CFI and TLI ≥ 0.95 indicate very good model fit [31, 32].

To examine antecedents and outcomes, regression analyses were conducted with the derived factor scores from both sets of models. Both the antecedents and the future outcomes variables were standardized to allow for easier interpretation and comparison of the size of coefficients. A conservative alpha level of 0.01 was adopted to account for multiple testing. Overall missing cells of antecedents and outcomes were 10.7% of the total, with missingness varying from 0% for birth weight to 36.3% for school attendance. Little’s MCAR test indicated that data of the antecedents and outcomes were missing at random, χ2 (15278) = 7764.490, p = 1.000. Twenty sets of multiple imputation were conducted in STATA14 and all regression analyses were conducted in the imputed datasets.

Results

Model Fitting

Items with little (< 1% endorsement) or no variation were excluded, resulting in specific items being excluded from the rule-breaking and thought problems subscales (e.g., ‘Drinks alcohol without parents’ approval’ at age 8; ‘Sees things that aren’t there’, at age 14). For the GP bifactor model, items from the Anxious/Depressed (nitems = 13), Withdrawn/Depressed (nitems = 7–8) and Somatic Problems (nitems = 10-11) syndrome scales loaded on the specific Internalizing (INT) factor (total nitems = 31). Items from the Aggressive Behavior (nitems = 17–18) and Rule-breaking (nitems = 8–15) syndrome scales loaded on the Externalizing (EXT) specific factor (total nitems = 26–31). All items additionally loaded onto the GP factor, and items from the Thought Problems scale (nitems = 11–14) were estimated to load directly onto GP (and not on a specific thought problems factor, following [4], resulting in a total number of items for the GP models ranging from 71 to 76 for different measures at the different ages. For the DP bifactor model, items loaded both on the specific factors of either Anxious/Depressed (AD, nitems13), Aggressive Behavior (AGG, nitems= 17–18), or Attention Problems (AP, nitems = 8–10), as well as on DP (total nitems = 39–41).

Fit statistics of all factor models were adequate to good (see Table 1). Model fit was comparable for the GP and DP models. Fit indices for the YSR models were lower than for the CBCL models.

Parent-youth concurrent agreement at age 14 was modest (mean r = 0.26, range 0.17–0.36). All factor loadings for the general GP- and DP-factors were significant in all models (nearly all, p < 0.001), and loadings of the shared items were comparable. The items representing thought problems all loaded significantly on the GP factors (most > 0.40). Items that most consistently showed the highest factor loadings on the general GP and DP factors were ‘Stubborn, sullen, or irritable’, and ‘Sudden changes in mood or feelings’. In the CBCL models, ‘Sulks a lot’ also consistently showed high factor loadings (this item is not present in the YSR.) As these items also had nonsignificant or negative specific factor loadings, they seem to most directly contribute to GP and DP. To illustrate, the, factor loadings for the age 8 GP and DP models are presented in the online supplementary files (Table A2).

Stability

There were no apparent differences between the GP and DP models regarding homotypic stability. When mothers reported at age 8 and 14 years, the GP and DP general factors were moderately stable (r = 0.58/0.61, p < 0.001), and the specific factors were weakly to moderately stable (r range from 0.28 for AGG to 0.45 for EXT, p < 0.001). When mothers reported at age 8 and youth at age 14, stability was weaker for both the GP and DP general factors (r = 0.19/0.19, p < 0.001), and for the specific factors (r range 0.12–0.21, p < 0.01/0.001).

Evidence for heterotypic continuity was also present, both from the general (GP/DP) to specific factors (r range 0.09–0.22, only DP at age 8 to AD at age 14 n.s.) as from the specific to the general factors (r range 0.08–0.20, all significant). When mothers reported at age 8 and youth at age 14, only three out of ten correlations were significant. Heterotypic continuity seems slightly larger for the GP models. See Table 2 for all longitudinal correlations.

Antecedents

Demographic Predictors

Gender was not related to the GP or DP general factors, but being female was associated with more INT and AD and fewer EXT, AGG, and AP. Higher maternal education was associated with lower levels of GP and DP and EXT/AGG, while income disadvantage was only related to higher GP and DP at age 8. Later-born children had lower levels of GP, INT and AD at age 8, and GP and DP at age 14. In all subsequent analyses of antecedents, we controlled for socio-demographic factors (gender, ethnicity, income, maternal education, and birth order).

Early Childhood Antecedents of the General GP and DP Factors

GP and DP based on maternal reports at age 8 (Table 3) and age 14 (Table 4) were similarly associated with child and family characteristics. Regarding child attributes, higher negative affectivity, lower cognitive ability, and less self-control were associated with more general problems (higher GP and DP). With regard to family factors, similarly, higher maternal depression, lower positive maternal parenting and poorer quality of the home environment were associated with higher GP and DP. Notably, GP and DP based on youth reports at age 14 were unrelated to all antecedents (see Table 5).

Early Childhood Antecedents of Specific Factors

Greater EXT and AGG were associated with lower effortful control and self-control and lower quality of the home environment. Greater INT and AD were associated with higher child negative affectivity and maternal depression. AP was associated with lower effortful control and poorer executive functioning (e.g., delay of gratification). Again, all measured antecedents proved unrelated to youth reported specific factors.

In summary, the general factors from the GP and DP bifactor models were associated similarly with early childhood antecedents. Conceptually similar specific syndromes (e.g., EXT and AGG) showed comparable associations with early childhood antecedents, while the AP factor was uniquely related to measures of executive functioning.

Developmental Outcomes

Outcomes of the General GP and DP Factors

Table 6 presents the outcomes of GP and DP based on maternal reports at age 8, indicating that higher GP and DP bifactor scores at age 8, were similarly associated with impaired academic functioning (i.e., lower average grade), more mental health issues (i.e., higher levels depression and sleep problems), poorer psychosocial functioning (i.e., more loneliness, less psychosocial maturity), and greater risk-taking. GP and DP based on maternal-reports at age 14 (Table 7) also predicted less school days attended, and higher instrumental and reactive aggression. Youth-reported GP and DP at age 14 (see Table 8), additionally predicted higher relational aggression, psychopathy and risk-taking propensity, and lower friendship quality psychosocial maturity (but not less school days attended). When not taking into account the specific factors (i.e., when antecedents predicted the GP or DP general factors only), results were similar.

Outcomes of Specific Factors

Tables 6, 7 and 8 present coefficients of regression analysis using the specific factors as predictors of outcomes over and above the general GP and DP factors. The EXT (GP) and AGG (DP) factors were mainly associated with higher levels of aggression, risk-taking, psychopathy and lower average grade. EXT at age 14 was more strongly associated with age-15 outcomes than AGG at the same age and predicted more outcomes such as lower school days attendance. The INT (GP) and AD (DP) factors were mainly associated with more depression and less psychopathy at age 15. Although they significantly predicted a few different outcomes, coefficients of these effects were similar. Finally, AP was most consistently related with a lower average grade and less psychosocial maturity.

In sum, the general GP and DP factors similarly predicted a range of negative outcomes in adolescence, even when controlling for the specific factors. Conceptually comparable syndromes again were similar in their predictions.

Discussion

This study examined conceptual and statistical similarities between two recently, but independently developed approaches which concern the structure of (child and adolescent) psychopathology: general psychopathology (GP, or p factor) and the Dysregulation Profile (DP). Our conceptual analysis revealed that GP and DP are described and derived very similarly and are similarly associated with a broad range of early-childhood antecedents and adolescent outcomes. The ways in which the models differ—mainly via inclusion of an Attention Problems factor in the DP model and that of thought and rule-breaking problems in the GP model—apparently does not have a large bearing on relations with antecedents and outcomes, suggesting that both operationalizations result in similar formulations of general vulnerability for psychopathology. Interestingly, it has been suggested that a GP factor without thought problems can be better referred to as a “general behavioural/emotional dysregulation dimension” [33]. Future research needs to examine both GP and DP models in relation to measures and indicators of thought problems to further establish whether thought problems are key to general vulnerability of psychopathology [34].

Inspection of factor loadings indicates that mood regulation difficulties and irritability lie at the core of both GP and DP, as items such as ‘Stubborn, sullen, or irritable’ and ‘Sudden changes in mood or feelings’ most directly contributed to the general factors. Emotion dysregulation is central to many clinical conditions, and difficulties in emotion regulation (e.g., with selecting and implementing regulatory strategies) can underlie various forms of psychopathology [35]. Many ways of thinking about psychopathology have long had emotion dysregulation at its core and the central role of emotional dysregulation in GP and DP has been previously highlighted [4, 36]. It is noteworthy that the abovementioned items together with ‘Temper tantrums or hot temper’ (that especially had high loadings on DP) have been used together previously as an index of irritability [37].

Both GP and DP were moderately stable from 8 to 14 years, in line with previous research on GP [17, 18, 28, 38] and DP [20, 39]. The specific factors showed only weak to moderate stability, however. This suggests that while general psychopathology remains fairly stable, specific problems (or symptom presentations) are more susceptible to change. Furthermore, evidence for both homotypic and heterotypic continuity was found, suggesting that general vulnerability for psychopathology predicts specific symptom presentations as well as vice versa. One recent study that, to the best of our knowledge, is the only study that examined stability of the GP model in adults, examined three- to four-year stability of a general psychopathology bifactor model in in a large (n = 43.093) sample of adults, using an DSM-IV interview schedule [40]. Stability was high for both the GP factor (β = 0.67) and specific factors of Fear, Externalizing. And Distress (βs ranged from 0.53 to 0.87). It thus might be that while specific symptom profiles are (relatively) susceptible to change in childhood and adolescence, they become more stable in adulthood. No studies yet however have examined developmental stability of DP/GP from childhood into adulthood, which would be needed to examine this hypothesis.

The general GP and DP factors were similarly associated with early childhood antecedents. Socio-demographic precursors were consistent with previous research as follows [4, 11]. General risk for the development of psychopathology, operationalized as either the general GP or DP factors, did not differ for boys and girls. Specific INT and AD were higher for girls, whereas EXT, AGG and AP were higher for boys. Furthermore, greater economic disadvantage and lower maternal education were most strongly related to higher scores on the general GP and DP factors. Stable child factors, such as temperament and lower cognitive ability, as well as family factors, such as maternal depression, proved to be similarly associated with the general GP and DP factors. Child and family antecedents of conceptually comparable specific syndromes (EXT and AGG, and INT and AD) yielded similar associations. Generally, lower effortful control, lower self-control and a lesser quality home environment predicted higher EXT or AGG, while higher child negative affectivity and maternal depression predicted more INT. This result makes clear that the specific and general factors should be distinguished, and it also demonstrates the unique utility of bifactor models to do so.

As research on childhood antecedents of GP and DP is scarce, several findings are discussed in more detail. First, early temperamental factors of negative affectivity and effortful control showed strongest (albeit still weak) longitudinal associations with GP and DP and showed incremental predictive validity for specific factors. Negative affectivity, or negative emotionality, and effortful control have been described in DeLisi and Vaughn’s temperament-based theory of antisocial behavioral and criminal justice system involvement [41, 42] as being significantly predictive of self-regulatory deficits throughout development. Especially for youth in disadvantages communities, these temperamental characteristics can put youth at risk for adverse development. DeLisi and Vaughn [41] describe a developmental pathway of regulatory difficulties in infancy, through difficult (early) childhood temperament, to low self-control in adulthood. Such a pathway is in line with previous studies showing links between infant and toddler regulatory problems and DP [43], between aspects of temperament and personality (pathology) and DP [39, 44], and between DP and GP, on one hand and adult outcomes of low self-control such as antisocial behavior on the other hand [19]. Exploring developmental pathways of early temperamental risk, through (dysregulated) general psychopathology, to antisocial involvement later in life could be an avenue for future research, especially in higher risk samples rather than the current population-based study.

Second, executive functioning measures were not related to GP and DP, which is surprising given that EF has widespread associations with psychopathology and his been linked to general psychopathology as well as dysregulation in previous research [6, 45, 46]. This could be a consequence of the measures used in the present study, which mostly tapped into non-emotional (“cool”) executive functioning. As EF measures did show associations with AP it could be that AP drives the link between EF and psychopathology. Attachment problems, which also have been associated with a general vulnerability for psychopathology [47], neither emerged as a significant predictor.

Third, surprisingly, no early-childhood antecedents were associated with youth-reported symptoms. As most early-childhood antecedents were parent-reported (e.g., temperament, maternal depression), shared method variance might partly explain the presence of associations with parent-reported symptoms and lack of associations with youth-reported psychopathology. Other studies have also documented a lack of associations between early antecedents such as socio-economic deprivation and cognitive ability and youth-reported, but not parent-reported, mental health [48, 49]. Given that youth-reported GP and DP were good predictors of many adolescent outcomes, and parent-youth agreement was in line with what is generally reported [50] these findings are unlikely to reflect peculiarities of youth reported symptoms in this dataset. This failure to detect potential determinants of youth-reported symptoms merits attention in future research.

Higher general GP and DP bifactor scores predicted adolescent outcomes similarly, irrespective of age of measurement and reporter, including poorer academic functioning, mental health, psychosocial functioning, and greater risky behavior and susceptibility to peer influence. Notably, most associations remained significant even when controlling for the specific factors. Again, the specific factors from the GP and DP models were more differentiated in their associations with adolescent outcomes. EXT and AGG generally predicted higher levels of different forms of aggression, while INT and AD mostly predicted higher depression and (lower levels of) psychopathy. AP uniquely predicted lower average grade and lower psychosocial maturity, indicating that difficulties in attention (cognition) regulation specifically, negatively impact adolescent’s academic achievement, as well as capacity for responsible self-management.

Earlier GP and DP predicted different forms of subsequent aggression as well as risk-taking, in line with previous studies showing associations of DP with antisocial behavior and disciplinary measures such as being expelled from school [19]. These links have been explained by shared deficits in dimensions of emotion and self-regulation in general psychopathology and antisocial behaviors, especially reactive (i.e. emotionally driven and impulsive) aggression [19, 41, 51]. However, especially specific Externalizing and Aggressive Behavior are thought to predict antisocial outcomes (e.g. [4]), independently of GP. Future research could examine whether GP and DP and/or specific Externalizing and Aggressive Behavior predict development of antisocial involvement over time, and thus act as risk factors for such impairing behaviors.

In the past decade, great progress has been made in understanding the nature of psychopathology, and it has become clear that substantial overlap exists between different psychiatric symptoms or disorders, at both behavioral and genetic levels [52, 53]. Our study adds to a growing body of research which provides support for the conceptualization of GP and DP as general syndromes, ones which exist over and above more specific syndromes of psychopathology. The GP and DP bifactor models provide an elegant way to explain interrelatedness between different forms of psychopathology and offer a refined way to parse out shared and common etiologies and outcomes and are thus highly useful in psychopathology research [23, 34, 54, 55]. Alternative emerging classifications, such as the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP; [56]) and the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC; National Institute of Mental Health), also view psychological disorders as dimensions of underlying cognitive and neurophysiological systems instead of separate and categorical entities. More research is needed to better define what GP and DP reflect [12].

The DP model proved more parsimonious than the GP, as it required a much smaller set of items. The GP model thus requires larger samples, which makes the DP model more practical for research purposes. The DP bifactor model was further differentiated from the GP bifactor model by the unique role of the AP factor. One of the main differences between the GP and DP models is that only in the DP model symptoms of Attention Problems are modeled as a specific factor. In the research reported and the practices implemented in adult studies on GP [4, 5], symptoms of attention problems were not included in the GP model. AP and EXT were at best weakly associated in the current report, and AP was uniquely predicted by early-childhood measurements, especially of executive functioning, and uniquely predicted adolescent functioning (e.g., average grade). The specific AP factor demonstrated clear additional value and we thus recommend researchers, especially in youth psychopathology, to model attention problems as a unique factor. Given the high occurrence of attention problems in childhood, its inclusion would be developmentally appropriate. Including a specific attention problems in GP models, as has been done recently in [17] is therefore highly recommended.

Lastly, there is robust evidence for GP and DP as broad developmental risk-markers, given the broad range of maladaptive outcomes reported in this and other studies. Future research should prioritize examining antecedents and neurobiological underpinnings as well as potentially malleable environmental factors (e.g., parenting) that are related to GP and DP, to identify possible targets for treatment and prevention.

Summary

This study examined the general factor of psychopathology (GP) and the Dysregulation Profile (DP), two conceptually similar, but independently developed approaches to understand comorbidity between externalizing and internalizing forms of psychopathology in children and adolescents. Specifically, this study examined the stability, antecedents and outcomes of GP and DP in a longitudinal community sample of 1073 children (49.8% female). GP and DP models were estimated at ages 8 and 14 years using the parent-reported CBCL and Youth Self Report (YSR), two widely used instruments for child and adolescent emotional and behavioral problems. GP and DP could be similarly derived using bifactor models, in which general factors (GP or DP) exist over and above specific factors of INT and EXT difficulties in the GP model or AD, AGG, and AP in the DP model. Results showed that the GP and DP factors were similarly stable and associated in very similar ways to putative antecedents and outcomes, derived in this multi-method multi-informant study. GP and DP areas of research that have been developing independently so far, would thus benefit from integration. Integrating research on the included syndromes, statistical approaches and findings will help increase our understanding of the relevance of a general psychopathology dimension, likely contributing to understanding the neurological correlates, biomarkers and environmental factors that predict greater risk of mental disorders through the life course.

References

Achenbach TM, Ivanova MY, Rescorla LA, Turner LV, Althoff RR (2016) Internalizing/externalizing problems: review and recommendations for clinical and research applications. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 55(8):647–656

Patalay P, Moulton V, Goodman A, Ploubidis GB (2017) Cross-domain symptom development typologies and their antecedents: results from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 56(9):765–776

Rhee SH, Lahey BB, Waldman ID (2015) Comorbidity among dimensions of childhood psychopathology: converging evidence from behavior genetics. Child Dev Perspect 9(1):26–31

Caspi A et al (2014) The p factor: one general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clin Psychol Sci 2(2):119–137

Lahey BB et al (2012) Is there a general factor of prevalent psychopathology during adulthood? J Abnorm Psychol 121(4):971–977

Geeraerts SB et al (2015) The child behavior checklist dysregulation profile in preschool children: a broad dysregulation syndrome. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 54(7):595–602

Deutz MHF, Geeraerts SB, van Baar AL, Deković M, Prinzie P (2016) The dysregulation profile in middle childhood and adolescence across reporters: factor structure, measurement invariance, and links with self-harm and suicidal ideation. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 25(4):431–442

Haltigan JD et al (2018) “P” and “DP:” examining symptom-level bifactor models of psychopathology and dysregulation in clinically referred children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 57(6):384–396

Laceulle OM, Vollebergh WAM, Ormel J (2015) The structure of psychopathology in adolescence. Clin Psychol Sci 3(6):850–860

Olino TM, Dougherty LR, Bufferd SJ, Carlson GA, Klein DN (2014) Testing models of psychopathology in preschool-aged children using a structured interview-based assessment. J Abnorm Child Psychol 42(7):1201–1211

Patalay P et al (2015) A general psychopathology factor in early adolescence. Br J Psychiatry 207(1):15–22

Tackett JL et al (2013) Common genetic influences on negative emotionality and a general psychopathology factor in childhood and adolescence. J Abnorm Psychol 122(4):1142–1153

Biederman J et al (1995) CBCL clinical scales discriminate prepubertal children with structured interview—derived diagnosis of mania from those with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34(4):464–471

Diler RS et al (2009) The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and the CBCL-bipolar phenotype are not useful in diagnosing pediatric bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 19(1):23–30

Holtmann M, Goth K, Wockel L, Poustka F, Bolte S (2008) CBCL-pediatric bipolar disorder phenotype: severe ADHD or bipolar disorder? J Neural Transm 115(2):155–161

Althoff RR, Verhulst FC, Rettew DC, Hudziak JJ, van der Ende J (2010) Adult outcomes of childhood dysregulation: a 14-year follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49(11):1105–1116

McElroy E, Belsky J, Carragher N, Fearon P, Patalay P (2018) Developmental stability of general and specific factors of psychopathology from early childhood to adolescence: dynamic mutualism or p-differentiation? J Child Psychol Psychiatry 59(6):667–675

Olino TM et al (2018) The development of latent dimensions of psychopathology across early childhood: stability of dimensions and moderators of change. J Abnorm Child Psychol 46(7):1373–1383

Deutz MHF et al (2018) Evaluation of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire-dysregulation profile (SDQ-DP). Psychol Assess 30(9):1174

Boomsma DI et al (2006) Longitudinal stability of the CBCL-juvenile bipolar disorder phenotype: a study in Dutch twins. Biol Psychiatry 60(9):912–920

Lahey BB et al (2015) Criterion validity of the general factor of psychopathology in a prospective study of girls. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 56(4):415–422

Bonifay W, Lane SP, Reise SP (2017) Three concerns with applying a bifactor model as a structure of psychopathology. Clin Psychol Sci 5(1):184–186

Snyder HR, Hankin BL (2017) All models are wrong, but the p factor model is useful: reply to Widiger and Oltmanns (2017) and Bonifay, Lane, and Reise (2017). Clin Psychol Sci 5(1):187–189

Tackett JL et al (2013) Common genetic influences on negative emotionality and a general psychopathology factor in childhood and adolescence. J Abnorm Psychol 122(4):1142

Hankin BL et al (2017) Temperament factors and dimensional, latent bifactor models of child psychopathology: transdiagnostic and specific associations in two youth samples. Psychiatry Res 252:139–146

Neumann A et al (2016) Single nucleotide polymorphism heritability of a general psychopathology factor in children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 55(12):1038–1045

Carver CS, Johnson SL, Timpano KR (2017) Toward a functional view of the p factor in psychopathology. Clin Psychol Sci 5(5):880–889

Snyder HR, Young JF, Hankin BL (2017) Strong homotypic continuity in common psychopathology-, internalizing-, and externalizing-specific factors over time in adolescents. Clin Psychol Sci 5(1):98–110

Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA (2001) Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families, Burlington

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (2012) Mplus Version 7 user’s guide. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles

Lt Hu, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 6(1):1–55

Cheung GW, Rensvold RB (2002) Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct Equ Model 9(2):233–255

Castellanos-Ryan N et al (2016) The structure of psychopathology in adolescence and its common personality and cognitive correlates. J Abnorm Psychol 125(8):1039–1052

Caspi A, Moffitt TE (2018) All for one and one for all: mental disorders in one dimension. Am J Psychiatry 17(5):831–844

Sheppes G, Suri G, Gross JJ (2015) Emotion regulation and psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 11:379–405

Masi G, Muratori P, Manfredi A, Pisano S, Milone A (2015) Child behaviour checklist emotional dysregulation profiles in youth with disruptive behaviour disorders: clinical correlates and treatment implications. Psychiatry Res 225(1–2):191–196

Stringaris A, Zavos H, Leibenluft E, Maughan B, Eley TC (2012) Adolescent irritability: phenotypic associations and genetic links with depressed mood. Am J Psychiatry 169(1):47–54

Murray AL, Eisner M, Ribeaud D (2016) The development of the general factor of psychopathology ‘p factor’ through childhood and adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol 44(8):1573–1586

Deutz MHF et al (2018) Normative development of the child behavior checklist dysregulation profile from early childhood to adolescence: associations with personality pathology. Dev Psychopathol 30(2):437–447

Greene AL, Eaton NR (2017) The temporal stability of the bifactor model of comorbidity: an examination of moderated continuity pathways. Compr Psychiatry 72:74–82

DeLisi M, Vaughn MG (2014) Foundation for a temperament-based theory of antisocial behavior and criminal justice system involvement. J Crim Justice 42:10–25

DeLisi M, Fox BH, Fully M, Vaughn MG (2018) The effects of temperament, psychopathy, and childhood trauma among delinquent youth: a test of DeLisi and Vaughn’s temperament-based theory of crime. Int J Law Psychiatry 57:53–60

Winsper C, Wolke D (2014) Infant and toddler crying, sleeping and feeding problems and trajectories of dysregulated behavior across childhood. J Abnorm Child Psychol 42:831–843

Althoff RR et al (2012) Temperamental profiles of dysregulated children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 43:511–522

Bloemen A et al (2018) The association between executive functioning and psychopathology: general or specific? Psychol Med 48(11):1787–1794

Martel MM et al (2017) A general psychopathology factor (P factor) in children: structural model analysis and external validation through familial risk and child global executive function. J Abnorm Psychol 126(1):137–148

Ein-Dor T, Viglin D, Doron G (2016) Extending the transdiagnostic model of attachment and psychopathology. Front Psychol 7:484

Johnston DW, Propper C, Pudney SE, Shields MA (2014) The income gradient in childhood mental health: all in the eye of the beholder? J R Stat Soc 177(4):807–827

Patalay P, Fitzsimons E (2016) Correlates of mental illness and wellbeing in children: are they the same? Results from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 55(9):771–783

Rescorla LA et al (2013) Cross-informant agreement between parent-reported and adolescent self-reported problems in 25 societies. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 42(2):262–273

Hyde LW, Shaw DS, Harri AR (2013) Understanding youth antisocial behavior using neuroscience through a developmental psychopathology lens: review, integration and directions for research. Biol Psychiatry 58:562568

Pettersson E, Larsson H, Lichtenstein P (2016) Common psychiatric disorders share the same genetic origin: a multivariate sibling study of the Swedish population. Mol Psychiatry 21(5):717

Pettersson E, Anckarsäter H, Gillberg C, Lichtenstein P (2013) Different neurodevelopmental symptoms have a common genetic etiology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 54(12):1356–1365

Reise SP (2012) The rediscovery of bifactor measurement models. Multivar Behav Res 47(5):667–696

Lahey BB, Krueger RF, Rathouz PJ, Waldman ID, Zald DH (2017) A hierarchical causal taxonomy of psychopathology across the life span. Psychol Bull 143(2):142–186

Kotov R et al (2017) The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): a dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. J Abnorm Psychol 126(4):454–477

Acknowledgements

Sanne Geeraerts is affiliated with the Consortium on Individual Development (CID), which is funded through the Gravitation program of the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture, and Science and the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO Grant Number 024.001.003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Deutz, M.H.F., Geeraerts, S.B., Belsky, J. et al. General Psychopathology and Dysregulation Profile in a Longitudinal Community Sample: Stability, Antecedents and Outcomes. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 51, 114–126 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-019-00916-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-019-00916-2