Abstract

Understanding the dysregulation profile (DP) consisting of high scores in aggression, attention problems, and anxious/depressed problems is still limited. The aims of the present study were threefold: (a) to analyze developmental trajectories of DP (b) to identify predictors of these trajectories, and (c) to study the outcome of DP in terms of mental disorders and criminal offenses in young adulthood. A sample of 402 individuals aged 11–14 years at baseline was followed up during adolescence and young adulthood. Latent class growth analysis was used to identify DP based on the youth self-report and the young adult self-report. Self-related cognitions, perceived parental behavior, life events and coping served as predictors, psychiatric diagnoses and criminal convictions in young adulthood as outcomes. There were three developmental trajectories representing high, moderate, and low DP subgroups with 9.2% of participants represented by the high DP subgroup. Among predictors, self-esteem (negative), self-awareness (positive), and high numbers of life events had the most consistent effect on high DP. Affective and anxiety disorders and any mental disorder were significant outcomes of the high DP subgroup in both sexes at the time of young adulthood. This first report on DP based on longitudinal self-reports shows that DP is stable for a sizeable proportion of youth during adolescence and young adulthood. The predictors for DP share some similarity with those predicting psychopathology in general. However, so far there seems to be no heightened risk for the development of crime in the concerned individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Regulation ability relates to modulating physiological arousal caused by strong emotions, restraining approach and reward seeking when required, inhibiting frustration, focusing attention, and organizing goal-directed behaviors [1]. Learning to regulate emotional and behavioral impulses is crucial for an adequate development and successful social integration of children and adolescents into society.

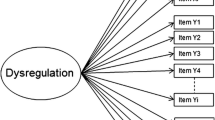

Dysregulation as a dimensional trait in children has been measured first by the use of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) syndrome scales labeled “aggression”, “attention problems” and “anxious/depressed” (CBCL-AAA-scales), and later by the corresponding youth self-report (YSR) scales. These three scales form the dysregulation profile (DP). Based on the cutoff score of T = 70, indicating the clinical range for all three CBCL-AAA-scales, some 1–3.5% of children with severe dysregulation problems have been identified in community surveys [2, 3].

Further studies have used empirical methods such as latent class analysis (LCA), latent profile analysis (LPA), or latent class growth analysis (LCGA) to identify children with severe DP either based on the parent reported CBCL [2, 4, 5] or on the corresponding YSR by adolescents in each of the 34 societies [6]. Previous longitudinal studies found three DP trajectories of low, moderate, and high DP profiles, respectively, with rather stable patterns over time [4, 7]. Both in community and in clinical studies, boys were overrepresented in high DP classes [2, 4, 7, 8]. Because all preceding studies were based on parent and teacher informants rating of child and early adolescent behavior, the validity of DP courses in older youth needs further confirmation by self-report measures.

Children with DP were clinically different from children with single disorders or problems only in that their comorbidity rates were much higher [2, 3] and findings from a Dutch twin study point to a strong genetic component in DP [9]. A recent review revealed a shortage of studies on predictors of DP [10]. The few existing studies were confined to parental information and identified pre-existing psychopathology, psychosocial adversity, and inadequate parenting as risk factors whereas a good quality of life was a protective factor for DP [4, 8, 11, 12].

In terms of the outcomes, there is clear evidence that the failure of regulation abilities increases the risk of mental disorders and maladaptive outcomes in late adolescence and young adulthood including persistent attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), disruptive behavior disorders, mood disorders, substance use disorders, and social problems [2, 13, 14]. In another study, children aged 8–14 with a CBCL-DP after a four year follow-up were also at risk for elevated scores on a wide range of DSM-5 personality pathology features, including higher scores on hostility, risk taking, deceitfulness, callousness, grandiosity, irresponsibility, impulsivity, and manipulativeness [15]. A cross-sectional study found that DP was associated with self-reported delinquency such as vandalism, property offenses and sexual offenses [16]. Although no previous study tested criminal outcomes of DP longitudinally, there is some indication that children and adolescents with mood dysregulation problems and irritability are at increased risk for later criminal outcomes in adolescence and adulthood [17, 18].

In summary, various studies have shown that valid DP trajectories can be identified based on ratings provided by different kinds of informants, including parents, teachers, and youth. DP is substantially heritable, is associated with high rates of comorbidity, and predicts adolescent personality abnormalities and diverse manifestations of adult mental disorders and crime. However, to understand the course of DP in older adolescents and young adults including predictors and outcomes, further studies based on self-report measures are needed.

The present study has three aims. Firstly, we intend to confirm and expand on previous findings from community samples of children and adolescents by measuring DP from age 11 to age 21 years based on the YSR-DP and the young adult self-report (YASR)-DP. In particular, we predict that we will find differing DP for males and females related to developmental trajectories. Based on previous findings of studies with younger cohorts and parent informants [2, 4, 5, 13, 14], we predict that we will identify at least three developmental trajectory subgroups with low, moderate, and severe DP.

Secondly, based on these developmental trajectories, we are interested in studying the power of various psychological traits and constructs in predicting DP. By expanding previous studies based on parent information on predictors and outcomes, we include adolescent information on self-related cognitions, perceived parental behavior, life stress, and coping abilities as predictor variables in the analyses. These measures had already been selected for a developmental psychopathology model used in our own preceding research based on a large community-based sample [19, 20].

Thirdly, we aim to investigate the outcome of severe DP in terms of mental disorders and criminal convictions in young adulthood. The latter might be a consequence of both the attention problems and the aggression components in DP. The increased risk of crimes has been documented in a recent meta-analysis of follow-up studies in ADHD [21] and is well established for children with conduct problems and aggression [22, 23].

Methods

Participants

The present sample consisted of 402 participants from the Zurich Epidemiological Study of Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, which was performed in 1994 (T1) (ZESCAP) [24]. Later, the ZESCAP was continued with two follow-up assessments of adolescents in 1997 (T2) and 2001 (T3) and was labeled the Zurich Adolescent Psychology and Psychopathology Study (ZAPPS) [19, 20, 25, 26]. The original ZESCAP comprised a cohort of N = 1964 pupils aged 7–16 years and was a stratified randomized sample representative of the 12 counties of the canton including the metropolitan area of the city of Zurich and a number of smaller cities and rural areas, the school grades, the types of school, and sex distribution. Only youth age 11 years and older (N = 1110) were considered to report on various self-report questionnaires (see below). All assessments took place during ordinary school lessons.

Among the N = 1110 students aged 11–16 years of the ZESCAP sample, a sizeable number of participants dropped out over time due to changing class compositions, school leavings, or failure to respond to mailed questionnaires (n = 329 from T1 to T2, n = 188 from T2 to T3). The comparison of dropouts (n = 517) and participants of the longitudinal sample (n = 593) revealed that older adolescent males with predominantly more externalizing problems were more likely to drop out from the study. However, all differences were relatively small in magnitude (Cohen’s d < 0.32) [25]. The design of this study addressing DP course across aged 11–21 years was only feasible with sufficient numbers of participants at each time point. In the analyses, all probands should be assessed at all three time points. We could not consider youth aged 15–16 years as these youth were included in two waves only before age 21. Therefore, we focused only on youth aged 11–14 years at T1, leaving a total of 402 participants, including 184 males (mean age = 12.57 years, SD = 1.07 years) and 218 females (mean age = 12.74 years, SD = 1.04 years). The mean age of the sample was 12.67 years (SD = 1.04 years) at T1, 15.74 years (SD = 1.08 years) at T2, and 19.29 years (SD = 1.13 years) at T3.

Measures

The analyses were based on two age-appropriate questionnaires for obtaining the DP score, four questionnaires delivering scores for the inclusion as predictors, and two ascertainments of outcomes including a structured diagnostic interview arriving at psychiatric diagnoses and data from the Swiss National Crime Register collecting information on criminal convictions. Psychometric features of questionnaires were tested and findings are available on request. Internal consistency coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha) were calculated for predictors at baseline as well as DP variables and were all in an adequate range (α > 0.70) in the present sample (see supplemental Table S1).

In agreement with the Swiss Health Survey [53], the socio-economic status (SES) was based on education (untrained, some vocational training, completed vocational training, completed upper secondary education, completed university education with a master degree) and professional occupation (unemployed, simple employee with no managing responsibility, employed with at least some managerial responsibility, self-employed or a manager with extended responsibility) of the parents and was assigned to five ordinal levels (low, lower medium, medium, upper medium, and high). Because SES was not assessed in the 1994 study, data were obtained 3 years later from the second wave of the study. “Low SES” was defined as low or lower medium SES. Foreign nationality (non-Swiss citizen) and non-metropolitan (outside Zurich and Winterthur) was coded from self-reports.

Youth self-report

This questionnaire measures behavioral and emotional problems in adolescents aged 11–17 during the past six months [27]. In the present study, the Swiss–German version [28] was used at T1 and T2. Items are scored on a three-point rating scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat true, and 2 = very true) and lead to a total problem scale, two second-order scales (internalizing and externalizing problems) and eight empirically derived first-order syndrome scales (including the anxious/depressed, attention problems, aggression, and delinquent behaviors scales).

Young adult self-report

With the exception of the subscale measuring social problems and the inclusion of the subscale measuring intrusiveness, the YASR [29] consists of the same primary and secondary scales as the YSR. The YASR was used at T3 (2001).

Dysregulation profile (DP)

Only items that were equivalent in both the YSR and YASR were considered for the present analyses. A dysregulation profile score (0–6) was calculated based on the sum of the average mean scores of the YSR/YASR anxious/depressed scale (12 items), the attention problems scale (4 items), and the aggression scale (9 items). Each scale had a possible range from 0 to 2. Hence, all three AAA-scales had the same weight when forming the DP score [2, 3]. The lists of the items of the YSR scales that were included in the analyses of DP are shown in the online supplement (supplemental information 01–03). Based on the current sample, the cutoff scores of T = 70 for clinical relevance (e.g., need for further detailed assessments) were calculated leading to values of 2.27 in boys and 2.44 in girls (averaged over T1–T3).

Self-related cognitions (SRC)

The ten-item scale for the measurement of self-esteem by Rosenberg [30] supplemented by two additional items from the Berlin Youth Cross-Sectional Study [31] was used as measure of self-esteem. Furthermore, the 20-item scale from a German questionnaire assessing self-awareness [32] was included in the analyses. The latter scale assesses introspective capacities for one’s feelings, actions, and past.

Perceived parental behavior (PPB)

This YSR instrument was developed for the ZAPPS and consists of 32 items [33]. Based on factor analysis, three identical scales that are highly correlated for maternal and paternal behavior were formed measuring parental acceptance, rejection, and control.

Life event scale (LES)

The scale covers 36 items based on pre-existing questionnaires on life events. The time frame was defined as the preceding 12 months. Besides frequencies of life events, a total life event impact score was calculated. This was based on a scale attached to each item ranging from – 2 to + 2, indicating how unpleasant or pleasant the respective event was [20]. The LES was used at T1, T2, and T3.

Coping Capacities Questionnaire (CCQ)

Our modified version of the German Coping Across Situations Questionnaire [34] addresses coping in situations at school, with parents, and with peers. Factor analysis resulted in two scales measuring active coping and avoidant behavior. The CCQ was used at T1 and T2.

Composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI)

Psychiatric assessments in young adulthood were based on the Computer-Assisted Personal Interview (CAPI) version of the Munich-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI) [35] covering DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria. Diagnostic findings reported in this paper are based on the CIDI/DSM-IV without using the DSM-IV hierarchy rules. The M-CIDI is a fully structured interview that covers 13 diagnoses and an additional indicator of any diagnosis. For the present study, we considered only diagnoses including functional impairment. Undergraduate psychology students were trained by a certified interviewer (CW) in a series of five interviews to perform the CAPI with the participants.

For the present study, diagnostic data were available for n = 356 participants. A total of n = 238 participants, including 113 males and 125 females, had one or more psychiatric diagnoses. This subsample was representative for the longitudinal sample in terms of age, sex, and urban/rural residence distributions. The reduction in sample size was due to the overall strategy of the ZAPPS using a two-step procedure with screening based on multiple measures in the first phase and consecutive personal interviews. A full description of the multi-screen procedure is available on request.

Criminal convictions (CC)

We obtained information on recorded criminal convictions in adulthood (age 18 + ) from the Swiss National Crime Register in 2009 and 2018. In particular, anonymized data on the following convictions were made available for the present study: Violent offenses (e.g., manslaughter, robbery, sexual coercion), property offenses (e.g., theft, burglary), traffic and drunk driving offenses, drug related offenses, and other offenses (including all offenses that did not fit into the above mentioned categories such as damage to property, breach of domestic peace, etc.). In the analyses, we differentiated between any crime and violent offenses. Misdemeanours and minor offenses with fines of less than 5000 Swiss Francs were not included in the official data set. Furthermore, due to official regulations, the records of convictions with punishments of less than 1-year imprisonment were no longer available after 10 years. Data were available for a total of N = 164 males and N = 199 females. The missing data on N = 39 participants were due to missing identification of names and birth dates.

Statistical analyses

Differences in the course of DP scores from age 11 to 21 years were examined by the use of person-centered latent class growth analysis (LCGA). This semi-parametric, group-based modeling strategy helps to determine whether there are different developmental subgroups in the population [36]. Also, this strategy identifies heterogeneous trajectories that differ in terms of intercept (initial level), slope (average growth) and curve (quadratic term). LCGA is a special type of growth mixture modeling (GMM), whereby the variance and covariance estimates for the growth factors within each class are assumed to be fixed to zero instead of being freely estimated [37]. Therefore, LCGA reduces computational burden and avoids problems of convergence. To examine the sex differences in DP scores, we conducted separate analyses for males and females to capture the unique sex characteristic in DP development. The analytical approach was based on an accelerated longitudinal design, in which age, rather than wave of assessment, was the time unit [4, 38, 39]. In this design, each adolescent had ten DP scores from age 11 to 21 years, including three values that represented true responses from wave 1–3 and 7 missing values that represented years with no assessments. Missing values were dealt with the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) method. This approach allows comparing age-specific rather than cohort-specific trajectories in males and females.

To find the optimal latent class growth model with the best goodness of fit, models with different numbers of classes were compared with a combination of different model selection criteria in a first series of analyses. Firstly, the Lo–Mendell–Rubin test (LMRT) and the bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT) were used to compare the k–1 and the k class models. A significant p value in LMRT and BLRT represents a statistically significant improvement in model fit with the inclusion of one more class. Secondly, we examined the Akaike information criterion (AIC), the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and the sample size-adjusted BIC (aBIC) in which a lower (i.e., closer to 0) value indicates a better model fit. Thirdly, we examined the entropy index that ranges from 0 to 1. Entropy closer to 1 represents a more accurate classification.

In the second series of analyses, we examined the predictive value of T1 risk factors for DP development by use of sex-specific multinomial logistic regression analyses with T1 risk factors as predictors and DP trajectory group membership as the outcome. Both univariate models considering only the variables of interest and multivariate models considering also the other predictors were performed. Given multiple testing, significance levels for the nine univariate analyses were corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg method (BH) [40].

The final series of analyses addressed the predictive validity of the DP trajectory groups in determining psychiatric disorders at T3 in a series of logistic regression analyses and criminal convictions by Fisher’s exact tests. In both analyses, significance levels were adjusted according to BH. The LCGA was performed using Mplus version 7.3.[41]. All other analyses were carried out using SPSS version 25. Individuals with missing data on outcome variables were dealt with using the FIML method in Mplus [41].

Results

Identification of DP trajectories

Model fit for the LCGA is shown in supplementary Table S2 and indicates that a three-class solution provided the best fit of the data both in males and females. As Fig. 1 displays, the three developmental trajectories represent high, moderate, and low DP profiles (because not all probands had data for all ages, we defined five age ranges representing youth aged 11–12, 13–14, 15–16, 17–18 and 19–21 years). There were n = 70 (38%) males in the low, n = 91 (49.5%) males in the moderate, and n = 23 (12.5%) males in the high DP subgroup. The corresponding numbers for females were n = 137 (62.8%) in the low, n = 67 (30.7%) in the moderate, and n = 14 (6.4%) in the high DP subgroup. The comparison of these three trajectories is presented in Table 1. These findings indicate that the three subgroups, both for males and females, did not show any significant differences in the proportion of participants from low socioeconomic status, foreign (migrant) populations, or non-metropolitan residence.

Furthermore, Table 1 documents that there were the expected significant differences in DP scores across the three trajectory subgroups at each time of the three assessments. General linear models with repeated measures showed that DP scores significantly varied across the three assessment points in male and female low, moderate, and high DP trajectories but partial eta squared effect sizes were only small (<0.20) for all groups. The single exception was the female high DP trajectory which showed a significant increase of DP scores between T1 and T2 and between T1 and T3 (F = 14.411 p < 0.000, partial eta square = 0.526, post-hoc test with Bonferroni correction: T1 vs. T2 DP score, p < 0.001, T1 vs. T3 DP score, p = 0.003).

Univariate and multivariate predictors of DP in males

The predictor analyses considered a total of nine variables and analyzed a low vs. moderate, a low vs. high, and a moderate vs. high contrast. The comparisons revealed a number of significant associations as shown for males in Table 2. Univariate analyses revealed high self-esteem as a protective factor for moderate and high DP and high self-awareness as a risk factor for moderate and high DP (compared to low DP). Parental acceptance was a protective factor against high DP whereas parental rejection was a risk factor for high DP (compared to low DP). Life event score, life event impact score, and avoidant coping were risk factors for high DP (compared to low DP). Further analyses revealed differences between moderate and high DP: self-esteem, parental rejection and life impact were risk factors for high DP (compared to moderate DP). Some of these significant associations on the univariate level were replicated on the multivariate level (entering all predictors simultaneously). High self-esteem was a protective factor for moderate DP, whereas high self-awareness and a high number of life events were risk factors for moderate DP (compared to low DP). Among all predictors, only high self-esteem was a significant protective factor for high DP in the corresponding multivariate analysis (compared to low DP). Furthermore, parental rejection was a significant risk factor for high DP in the corresponding multivariate analysis (compared to moderate DP).

Univariate and multivariate predictors of DP in females

The corresponding findings for females are shown in Table 3. Univariate analyses revealed high self-esteem as a protective factor for moderate and high DP (compared to low DP). High self-awareness was a risk factor for moderate DP but not for high DP (compared to low DP). Parental acceptance was a protective factor for high DP and parental rejection was a risk factor for moderate/high DP (compared to low DP). Life event score, life event impact score, and avoidant coping were risk factors for moderate/high DP (compared to low DP). Further analyses revealed no significant differences between moderate and high DP. In multivariate analyses, only self-esteem remained significant as a protective factor and parental rejection remained as a risk factor for moderate DP (compared to low DP). Finally, only parental rejection remained a significant risk factor predicting high DP in multivariate analyses (compared to low DP). Multivariate analyses revealed no significant discrepancies between moderate and high DP.

Psychopathological and criminal outcomes of DP in males and females

Associations of various major mental disorders with DP trajectories are documented in Table 4 (corrected for multiple testing by BH with either low DP or high DP as reference). In males, any mental disorder showed a significant association with the high DP, but not with the moderate DP trajectory (with low DP as reference category). Taking the high DP as reference category, the risk of any disorders was lower in both moderate and low DP. In females, the respective associations were even stronger than in males as evidenced by the higher odds ratios and the consistency across all diagnostic groups in the high DP subgroup (compared to low DP). This trend was noticeable for females already in the moderate DP subgroup for substance use disorders (compared to low DP). Taking high DP as reference category, the risk for affective, anxiety and other disorders was lower in moderate DP. Finally, the associations between the various DP subgroups with criminal convictions were not significant for either any crime or violent crimes as shown in Table S3.

Discussion

The present study addressed three major issues using a novel approach. In the first part of the analyses, the LCGA method was used to arrive at a classification of DP in terms of developmental trajectories based on longitudinal data with assessments during adolescence and young adulthood. As expected, three different classes with high, moderate, and low developmental trajectories of DP were identified indicating that some 9% of the entire participants displayed persistent DP problems across time. The established cutoff scores of clinical relevance amounting to 2.27 for boys and 2.44 for girls on the scale running from 0 to 6 indicate that a sizeable number of youths with high DP show limited psychosocial functioning in daily life and, therefore, may be in need of further assessment and consideration of clinical intervention.

Other than previous similar classificatory approaches based on parent-reported data [2, 4, 5], the analyses in the present study were based on YSRs . To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on DP trajectories based on self-reports by adolescents and young adults. The international comparison study of the DP in youth was based on cross-sectional data and thus does not fit for direct comparison of findings [6]. Furthermore, the only minimal sex differences in the international comparison study, which were also apparent in one of the CBCL-based studies [2], are not matched by the findings of the present study.

With 12.5% of males and 6.4% of females in the high DP subgroup, there was a markedly stronger vulnerability in males to show persistent DP problems across age 11–21. It could well be that this higher vulnerability in males was driven by the ADHD and aggression components in the DP, since both domains are more prevalent in adolescent and young adult males [42, 43]. However, more insight into the construct of DP and, in particular, the question whether DP is more than the sum of its component may not be gained from the present study with different objectives. Most DP trajectories were rather stable and showed only minimal variations across time. The only exception was the female high DP trajectory that increased between late childhood and early adolescence. This finding is concordant with the parent reported courses of high DP in girls, reported by Kunze et al. [4], that showed some increase on a descriptive level without reaching statistical significance. It matches the finding of higher vulnerability of female youth for affective disorders as shown in a recent large population study [44]. Furthermore, the increasing developmental trajectories of both depressive and anxious symptoms in adolescent girls have been found to be related to a negative cognitive style and stressor interaction [45], which may also explain the present finding of the female high DP trajectory increasing over time. Our trajectory findings further suggest that DP continues into young adulthood at least for some youth of both sexes. Most previous studies limit their analyses of DP profiles to childhood and adolescence and then separately examine later risk for adult outcomes. Thus, the observed continuity of a DP profile into adulthood represents a novel finding.

In the second part of the analyses, various psychological constructs were tested for their power to predict membership in the three different DP subgroups and high DP in particular. A total of nine constructs representing self-related cognitions, perceived parental behavior, life events and coping capacities were included in the analyses. Although the findings were not fully identical to the two sexes, there were trends with low self-esteem, high self-awareness (particularly in males), and high number of life events having the most consistent associations with high DP in the two contrasts (low/moderate and low/high DP) and in both univariate and multivariate analyses. In addition, parental acceptance was a protective factor against high DP only in univariate analyses but not in multivariate analyses. Perceived parental rejection was a risk factor, particularly in females. Furthermore, parental rejection was increased in high compared to moderate DP in males, whereas in females no significant predictors differed significantly between moderate and high DP.

These findings are in line with previous findings testing CBCL-DP in younger children and reporting that parenting and social stressors are associated with DP [12]. Furthermore, these findings are very much in accordance with other findings from the overarching ZAPPS, which the present study is a part of. In this project, high self-esteem was shown to be a compensatory factor in terms of reducing the likelihood of developing internalizing or externalizing problems [19, 20], while low self-esteem in cross-lagged panel analyses was a risk factor for internalizing problems and a stronger predictor of these problems in comparison to coping behavior, efficiency of social networks and impact of life events [25]. These various findings once again emphasize the relevance of the principle of multifinality with same risks contributing to various outcomes. The finding of high self-awareness as a predictor of moderate DP was rather unexpected. However, previous research has indicated that high self-awareness was related to dysfunctional cognitive processes in anxiety disorders [46]. Hence, in the present study high self-awareness may have been related to the anxiety component in the DP profile of males with moderate DP.

Furthermore, stress resulting from a high number of life events as a well-established risk factor [47] was also evident in the present study, though the associations with DP were not strong enough to survive multivariate adjustments for other risk factors. Finally, perceived parental rejection was a strong and consistent risk factor for DP in both contrasts and even in multivariate analyses, but only in females. Thus, this finding points to a rather specific vulnerability in females which in a similar way has also been shown for females with lifetime suicidal attempts who experienced parental rejection during childhood [48]. In summary, the findings on predictors and risks of DP in the present study are not only novel in this area of research, but also point to an ensemble of risk factors shared with other forms of adolescent and young adult psychopathology.

Finally, in the present study the associations of DP with two major outcomes, namely mental disorders and crime in young adulthood, were analyzed. The approach of the present study was novel again insofar as self-reports of DP were analyzed while previous attempts of studying psychiatric outcomes had been based on parent-reported DP only [2, 13, 14]. The respective associations were strongest in both sexes between high DP and affective disorders, anxiety disorders, and any psychiatric disorder, and were also evident between high DP and substance use disorders in females but not in males.

The lack of associations between ADHD or disruptive disorders and high DP, which has been observed in the above-mentioned studies based on parent reports, is noteworthy. It may in part be explained by informant discrepancies with male adolescents, in particular, disclosing externalizing disorders including their harmful effects on others less frequently [for a detailed discussion see 49]. However, this study’s novel finding of no association between DP and later criminal outcomes in young adulthood supports the conclusion that the developmental trajectories of DP in youth do not show an association with externalizing disorders and are more confined to the domain of internalizing disorders as represented by affective and anxiety disorders.

Strengths and limitations

The present study was based on a community sample followed up during an important developmental period with three follow-up assessments using reliable and valid indicators of mental functioning. The approach of studying DP trajectories by repeated self-reports is novel as is the focus on predictors and outcomes. Limitations include the loss in sample size of participants who were diagnosed with the CIDI due to the two-step procedure of the study design. We cannot exclude that a possible bias by dropout may have influenced the current findings. This may result in a DP score that is more driven by the anxious/depressed syndrome scale than by aggressive behaviors and attention problems/behavioral impulsivity. Furthermore, the statistical approach of LCGA based on age-specific dysregulation measures led to missing values. Therefore, the validity of the trajectories may be limited and developmental trends should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, the current definition of DP is based on equivalent items in the YSR- and YASR-AAA-scales and differs from the original DP construct based on full information on the CBCL- or YSR-AAA-scales [e.g., 6, 9, 14]. In addition, the time window of assessment between ages 11 and 21 may still be too narrow to get a full picture of the adult outcomes in terms of mental disorders and criminal offenses. Finally, official records of criminal convictions in adulthood are limited to crimes that were reported to the police and were considered in the Swiss National Crime Register.

Conclusions

This study provides further evidence that the construct of DP is a valid psychopathological entity with remarkable stability across adolescence and young adulthood that there exist similar risks of developing DP like in other mental problems of this age period and that there is a heightened risk of DP resulting in mostly internalizing disorders in young adulthood. While identification of individuals at risk for DP is feasible, the question whether the affected individuals need specific tailor-made interventions or may better profit from well-established interventions for mental disorders still needs to be evaluated.

References

McQuillan ME, Kultur EC, Bates JE, O'Reilly LM, Dodge KA, Lansford JE, Pettit GS (2018) Dysregulation in children: origins and implications from age 5 to age 28. Dev Psychopathol 30(2):695–713. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579417001572

Althoff RR, Verhulst FC, Rettew DC, Hudziak JJ, van der Ende J (2010) Adult outcomes of childhood dysregulation: a 14-year follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49(11):1105–1116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.08.006

Hudziak JJ, Althoff RR, Derks EM, Faraone SV, Boomsma DI (2005) Prevalence and genetic architecture of child behavior checklist–juvenile bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 58(7):562–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.024

B Kunze, B Wang, C Isensee, R Schlack, U Ravens-Sieberer, F Klasen, A Rothenberger, A Becker, group BE-s (2018) Gender associated developmental trajectories of SDQ-dysregulation profile and its predictors in children. Psychol Med 48(3): 404–415 doi: 10.1017/S0033291717001714

B Wang LG, Brueni C, Isensee T, Meyer N, Bock U, Ravens-Sieberer F, Klasen, R Schlack, A Becker, A Rothenberger, group Bs (2018) Predictive value of dysregulation profile trajectories in childhood for symptoms of ADHD, anxiety and depression in late adolescence Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27 6 767–774 doi: 10.1007/s00787-017-1059-y

Jordan P, Rescorla LA, Althoff R, Achenbach TM (2016) International comparisons of the youth self-report dysregulation profile: latent class analyses in 34 societies. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 12(55):1046–1053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.08.012

Boomsma DI, Rebollo I, Derks EM, van Beijsterveldt TC, Althoff RR, Rettew DC, Hudziak JJ (2006) Longitudinal stability of the CBCL-juvenile bipolar disorder phenotype: a study in Dutch twins. Biol Psychiatry 60(9):912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.028

Jucksch V, Salbach-Andrae H, Lenz K, Goth K, Dopfner M, Poustka F, Freitag CM, Lehmkuhl G, Lehmkuhl U, Holtmann M (2011) Severe affective and behavioural dysregulation is associated with significant psychosocial adversity and impairment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 52(6):686–695. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02322.x

Althoff RR, Rettew DC, Faraone SV, Boomsma DI, Hudziak JJ (2006) Latent class analysis shows strong heritability of the child behavior checklist–juvenile bipolar phenotype. Biol Psychiatry 9(60):903–911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.025

Caro-Canizares I, Garcia-Nieto R, Carballo JJ (2015) Biological and environmental predictors of the dysregulation profile in children and adolescents: the story so far. Int J Adolesc Med Health 27(2):135–141. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2015-5004

Dougherty LR, Smith VC, Bufferd SJ, Carlson GA, Stringaris A, Leibenluft E, Klein DN (2014) DSM-5 disruptive mood dysregulation disorder: correlates and predictors in young children. Psychol Med 44(11):2339–2350. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713003115

Kim J, Carlson GA, Meyer SE, Bufferd SJ, Dougherty LR, Dyson MW, Laptook RS, Olino TM, Klein DN (2012) Correlates of the CBCL-dysregulation profile in preschool-aged children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 53(9):918–926. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02546.x

Biederman J, Spencer TJ, Petty C, Hyder LL, O’Connor KB, Surman CB, Faraone SV (2012) Longitudinal course of deficient emotional self-regulation CBCL profile in youth with ADHD: prospective controlled study. Neuropsych Dis Treat 8:267. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S29670

Holtmann M, Buchmann AF, Esser G, Schmidt MH, Banaschewski T, Laucht M (2011) The Child Behavior checklist-dysregulation profile predicts substance use, suicidality, and functional impairment: a longitudinal analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 52(2):139–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02309.x

De Caluwé E, Decuyper M, De Clercq B (2013) The child behavior checklist dysregulation profile predicts adolescent DSM-5 pathological personality traits 4 years later. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 22(7):401–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0379-9

Dolitzsch C, Kolch M, Fegert JM, Schmeck K, Schmid M (2016) Ability of the child behavior checklist-dysregulation profile and the youth self report-dysregulation profile to identify serious psychopathology and association with correlated problems in high-risk children and adolescents. J Affect Disord 205:327–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.010

Aebi M, Barra S, Bessler C, Steinhausen HC, Walitza S, Plattner B (2016) Oppositional defiant disorder dimensions and subtypes among detained male adolescent offenders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 57(6):729–736. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12473

Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Egger H, Angold A, Costello EJ (2014) Adult diagnostic and functional outcomes of DSM-5 disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Am J Psychiatry 171(6):668–674. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13091213

Steinhausen HC, Bosiger R, Metzke CW (2006) Stability, correlates, and outcome of adolescent suicidal risk. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 47(7):713–722. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01569.x

Steinhausen HC, Winkler Metzke C (2001) Risk, Compensatory, vulnerability, and protective factors influencing mental health in adolescence. J Youth Adolesc 30(3):259–280. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010471210790

Mohr-Jensen C, Steinhausen HC (2016) A meta-analysis and systematic review of the risks associated with childhood attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder on long-term outcome of arrests, convictions, and incarcerations. Clin Psychol Rev 48:32–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.002

Aebi M, Giger J, Plattner B, Metzke CW, Steinhausen HC (2014) Problem coping skills, psychosocial adversities and mental health problems in children and adolescents as predictors of criminal outcomes in young adulthood. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 23(5):283–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0458-y

Erskine HE, Norman RE, Ferrari AJ, Chan GC, Copeland WE, Whiteford HA, Scott JG (2016) Long-term outcomes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 55(10):841–850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.06.016

Steinhausen HC, Metzke CW, Meier M, Kannenberg R (1998) Prevalence of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: the Zürich epidemiological study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 98(4):262–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb10082.x

In-Albon T, Meyer AH, Winkler Metzke C, Steinhausen HC (2017) A Cross-lag panel analysis of low self-esteem as a predictor of adolescent internalizing symptoms in a prospective longitudinal study. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 48(3):411–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-016-0668-x

Steinhausen HC, Winkler Metzke C (2003) Prevalence of affective disorders in children and adolescents: findings from the Zurich epidemiological studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 418:20–23. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.108.s418.5.x

Achenbach TM (1991) Manual für the youth self report and 1991 profile. University of Vermont, Burlington, VT, Department of Psychiatry

Steinhausen HC, Winkler Metzke C, Kannenberg R (1999) A questionnaire for adolescents: the Zurich results of the youth self report. University of Zurich Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Zürich

Achenbach TM (1997) Young adult self report. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry, Burlington (VT)

Rosenberg M (1965) Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). Acceptance Commitment Therapy Measures Package 61:52

Silbereisen RK, Eyferth K, Rudinger G (1986) Development as action in context. Springer, Berlin

Filipp S-H, Freudenberg E (1989) Der Fragebogen zur erfassung dispositionaler selbstaufmerksamkeit:(SAM-Fragebogen) [questionnaire for the assessment of dispositional self—awareness]. Hogrefe, Göttingen

Reitzle M, Winkler Metzke C, Steinhausen H-C (2001) Eltern und Kinder: der zürcher kurzfragebogen zum erziehungsverhalten (ZKE) [parents and children: the Zurich short questionnaire on parental rearing behavour (ZKE)]. Diagnostica 47(4):196–207. https://doi.org/10.1026//0012-1924.47.4.196

Seiffge-Krenke I (1989) Bewältigung alltäglicher problemsituationen: ein coping-fragebogen für jugendliche [a coping questionnaire for adolescents]. Zeitschrift Differentielle Diagnostische Psychol 10(4):201–220. https://doi.org/10.1026//0049-8637.34.4.216

Wittchen H-U, Pfister H (1997) DIA-X-Interviews: manual for screening-procedure and interview. Swets & Zeitlinger, Frankfurt

Nagin DS (1999) Analyzing developmental trajectories: a semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychol Methods 4(2):139. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.4.2.139

Jung T, Wickrama K (2008) An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 2(1):302–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00054.x

Duncan SC, Duncan TE, Hops H (1996) Analysis of longitudinal data within accelerated longitudinal designs. Psychol Methods 1(3):236. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.3.236

Duncan SC, Duncan TE, Strycker LA (2001) Qualitative and quantitative shifts in adolescent problem behavior development: a cohort-sequential multivariate latent growth modeling approach. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 23(1):43–50. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011091523808

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol 57(1):289–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x

Muthen B, Muthen L (2012) Mplus user’s guide, 7th edn. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles

Odgers CL, Moffitt TE, Broadbent JM, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Poulton R, Sears MR, Thomson WM, Caspi A (2008) Female and male antisocial trajectories: from childhood origins to adult outcomes. Dev Psychopathol 20(2):673–716. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579408000333

Polanczyk GV, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA (2007) The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry 164(6):942–948. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.942

Hyland P, Shevlin M, Elklit A, Christoffersen M, Murphy J (2016) Social, familial and psychological risk factors for mood and anxiety disorders in childhood and early adulthood: a birth cohort study using the Danish Registry System. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 51(3):331–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1171-1

Hankin BL (2009) Development of sex differences in depressive and co-occurring anxious symptoms during adolescence: descriptive trajectories and potential explanations in a multiwave prospective study. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 38(4):460–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410902976288

Schwarzer R, Wicklund RA (2015) Anxiety and self-focused attention. Routledge, Abingdon

Goodyer IM (1990) Family relationships, life events and childhood psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 31(1):161–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1990.tb02277.x

Ehnvall A, Parker G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Malhi G (2008) Perception of rejecting and neglectful parenting in childhood relates to lifetime suicide attempts for females–but not for males. Acta Psychiatr Scand 117(1):50–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01124.x

Dirks MA, De Los RA, Briggs-Gowan M, Cella D, Wakschlag LS (2012) Annual research review: embracing not erasing contextual variability in children’s behavior–theory and utility in the selection and use of methods and informants in developmental psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 53(5):558–574. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02537.x

Funding

Data collections for the present study were supported by grants provided by the Johan Jacobs Foundation and the Swiss National Science Foundation awarded to Professor Steinhausen. The funding sources had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, the writing of the article, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Drs. Aebi, Winkler Metzke, and Steinhausen report no potential conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

An ethics committee did not exist at the study center (based at the University of Zurich) or in the canton of Zurich, Switzerland, to give approval at the time the data collection started in the 1990s. The original study by the principal investigator had been approved and supported by the local Department of Education (a governmental institution of the canton of Zurich) and the informed consent of the parents of all participating students had been obtained. The use of anonymized data on crime outcomes was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Canton of Zurich and data were delivered by a government institution, namely, the Swiss Federal Office of Justice. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aebi, M., Winkler Metzke, C. & Steinhausen, HC. Predictors and outcomes of self-reported dysregulation profiles in youth from age 11 to 21 years. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 29, 1349–1361 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01444-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01444-z