Abstract

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been developed and modified to treat anxiety symptoms in youth with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders (ASD) but has yielded varying findings. The present report is a systematic review and meta-analysis examining the efficacy of CBT for anxiety among youth with ASD. A systematic search identified 14 studies involving 511 youth with high-functioning ASD. A random effects meta-analysis yielded a statistically significant pooled treatment effect size (g) estimate for CBT (g = −0.71, p < .001) with significant heterogeneity [Q (13) = 102.27, p < .001]. Removal of a study outlier yielded a statistically significant pooled treatment effect size, (g = −0.47, p < .001). Anxiety informant and treatment modality were not statistically significant moderators of treatment response. Findings suggest that CBT demonstrates robust efficacy in reducing anxiety symptoms in youth with high-functioning ASD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As many as 50 % of youth with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by social and/or communication deficits and restrictive/repetitive behaviors [1], experience clinically significant anxiety [2–5]. These youth appear more prone to experiencing anxiety symptoms than neurotypical youth, due to their significant communication and social deficits (e.g., difficulty understanding social cues) [6], heightened sensory sensitivity [7] and difficulty regulating emotions [6, 8]. In youth with ASD, clinically significant anxiety symptoms are associated with increased irritability, sleep disturbance, disruptive behaviors, inattentiveness and health problems (e.g., frequent gastrointestinal problems) [9–12] that significantly impair school, home, and family functioning above and beyond impairments associated with core ASD symptoms [9, 11, 13–15]. Consequently, cognitive-behavioral treatments that specifically target anxiety symptoms in youth with high-functioning ASD have been designed and evaluated.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety in Youth with ASD

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for anxiety targets cognitive (e.g., anxiogenic cognitive factors) and behavioral (e.g., avoidance, rituals) factors that contribute to the maintenance of anxiety symptoms [16]. Avoidance of feared stimuli is negatively reinforcing (i.e., the individual experiences a decrease in distress when the feared stimuli is removed) and reinforces future avoidant behaviors. Accordingly, CBT treats anxiety symptoms by exposing the individual to the feared stimuli in a gradual, progressive manner while preventing avoidant or ritualistic behaviors which allows the individual to naturally habituate to anxiety. Cognitive components of CBT can include emotion identification, challenging assumptions and schemas, and cognitive restructuring tasks to target distorted thoughts. Behavioral components beyond exposure to feared stimuli, include increasing pleasurable activities and behavioral management techniques such as rewards and reinforcements. When employed across disorders, CBT components can vary on the emphasis that is placed on cognitive or behavioral components and can be tailored to meet the individual’s unique abilities and symptom presentation.

Core components of CBT for the treatment of anxiety symptoms in typically developing youth and youth with high-functioning ASD include psychoeducation (e.g., the nature of the child’s anxiety and treatment rationale is explained by the therapist), cognitive therapy (e.g., worries are challenged and thoughts are restructured), creation of the fear hierarchy (i.e., feared stimuli are ranked according to how anxiety-provoking they are to the youth), and exposure and response prevention (i.e., the youth is repeatedly and gradually exposed to feared stimuli in an hierarchical manner and prevented from engaging in anxiety-reducing tactics until the anxiety has naturally decreased) [17–20]. The application of CBT in typically developing youth has been modified to be appropriate for youth with ASD. For example, youth with ASD often have difficulty understanding and recognizing the thoughts and feelings of others and within themselves. Consequently, CBT protocols have been modified to include social stories that explain the thoughts and feelings of others, social coaching to develop social skills, as well as visual aids and structured worksheets to employ CBT components [17, 18]. Efficacy of CBT in typically developing youth [21] and youth with ASD [18, 19] has been demonstrated across a number of studies. However, in youth with ASD, the magnitude of effects is more variable with some studies finding robust effects [22] while others have found more modest [23] or small effects [24].

To date, one systematic review [25] and one systematic review and meta-analysis [26] have examined the efficacy of CBT for clinically significant anxiety symptoms in youth with ASD. Sukhodolsky et al. [26] included 8 published randomized controlled clinical trials comparing CBT for anxiety in high-functioning youth with ASD with another treatment, no treatment control, or waitlist control. Moderate to large treatment effect sizes were reported: clinician (d = 1.19), parent (d = 1.21), and child (d = 0.68) with significant heterogeneity within groups. The authors concluded that CBT yielded significant treatment effects for youth with ASD and that clinician and parent reports were sensitive to treatment changes but that child reports were not.

Although these reviews have provided an insightful narrative summary supporting the use of CBT and Sukhodolsky et al. [26] had included quantitative analyses to support these claims, these studies have two primary limitations. First, due to the limited number of studies included in these past meta-analyses, publication bias and moderator analyses could not be performed. Identification of moderators would help inform researchers and clinicians about whether treatment efficacy varies across specific study and treatment variables and aid in individualizing treatment plans. Second, since the publication of the most current review and meta-analysis [26], four randomized CBT trials and two open trials for anxiety in youth with ASD have been reported. The addition of these six studies to the literature warrants an updated meta-analysis and systematic review. Consequently, the present paper aims to update the previous systematic review and meta-analysis [26] and explore moderators of CBT response among youth with high-functioning ASD. Specifically, this meta-analysis aims to examine if treatment efficacy varies as a function of the reporter (child, parent, or clinician) and treatment modality (group versus individual sessions).

Potential Moderators of Response

Treatment Modality

In youth with high-functioning ASD, CBT has been administered in a group fashion [27], individually with family involvement [18, 19] or both [28]. Although a study has never been conducted to examine the differences in the effectiveness of these treatment modalities in youth with ASD, it has been suggested that individualized treatment of anxiety in youth with ASD may be more efficacious than group therapy [29, 30]. Individual treatment may offer greater flexibility and can be tailored to meet the specific needs of the youth such as adjusting treatment to meet the cognitive and communication skill level of the youth with ASD.

Anxiety Informant

Evidence suggests that children’s, parents’ and clinicians’ reports of treatment efficacy can differ significantly. In particular, the child’s report, when compared to the reports of the parent and clinician, is frequently discrepant [18, 27, 31]. This disparity may be the result of the child’s limited insight into his/her anxiety symptoms (e.g., lack of recognition that anxiety symptoms are clinically significant and/or are impairing) or comorbid conditions (e.g., attention difficulties, oppositional behaviors) [2, 5, 6, 15]. These results suggest that the perception of CBT efficacy at reducing anxiety may vary as a function of the informant.

Current Study

To facilitate evidence-based practice in the implementation of CBT in youth with high-functioning ASD, this study reviewed the current literature and examined the efficacy of CBT to reduce anxiety symptoms in youth with high-functioning ASD via meta-analytic methods. This study had the following aims: (1) describe and summarize the characteristics of the included studies; (2) examine the efficacy of CBT to reduce anxiety symptoms in youth with high-functioning ASD; and (3) explore if treatment efficacy varies as a function of who assesses the child’s anxiety (i.e., child, parent, or clinician) and treatment modality (i.e., group versus individual sessions). Based upon previous findings supporting the efficacy of CBT for anxiety in youth with ASD, it was hypothesized that CBT would yield an overall moderate treatment effect size.

Method

Literature Search

A systematic search of computerized databases (PsychInfo, Pubmed, Google Scholar, ProQuest Dissertation/Thesis Library) and abstracts and reference lists of published and unpublished work was conducted using the key words “ Autism”, “Autistic”, “Asperger”, “PDD”, “ASD” in various combinations with “anxiety”, “phobia”, “fear”, “OCD” and “cognitive behavioral therapy”. Thereafter, abstracts were reviewed by the first author and a research assistant for relevance.

Selection of Studies

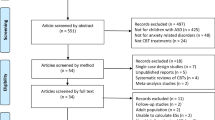

Studies were included in the meta-analysis if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) study must report on a randomized controlled trial or open trial of CBT for anxiety in youth with ASD; (2) study must involve a sample of youth with ASD aged 18 years or younger; (3) ASD diagnosis must be established through a reliable measure of ASD (e.g., the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R); [32], the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS); [33]) and/or through medical records; (4) reduction of anxiety symptoms must be the primary aim of the study; and (5) anxiety must be measured through a psychometrically sound instrument (i.e., reliability and validity of anxiety measure have been established in youth with or without ASD). Case studies, qualitative case reports and single case designs were not included in this meta-analysis. This search was not limited to a specific time period and included only studies published in English. The last search was run November 17th, 2013. See Fig. 1 for a flowchart diagram of the selected studies.

Selection of Treatment Outcome Measures

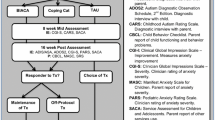

Based on the demonstrated psychometric properties and the use of common anxiety severity scales in youth with ASD, a preferred list of outcome measures was generated a priori. Preferred rating scales included Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule Clinical Severity Rating (ADIS-IV; [34]), Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory-4 Anxiety Scale (CASI-Anx; [15]), Clinical Global Impression-Severity scale (CGI-S; [35]), Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; [36]), Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS; [37]), Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; [38]), Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED; [39]), and Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS-P/C; [40]).

Data Collection and Coding of Study Variables

Each study was independently coded using specific coding sheets by the study’s first and second authors for the following information: sample size, gender distribution, mean age of the sample (years), mean intelligence quotient (IQ) or study IQ requirement (e.g., full scale, verbal), ASD diagnosis, distribution of anxiety diagnoses, medication usage, study design, treatment modality (i.e., group versus individual CBT sessions) and duration, treatment fidelity, anxiety measures used, and anxiety informant (i.e., child, parent, and clinician) and corresponding effect size (g) (see Table 1). Inter-rater agreement for study characteristics was excellent for categorical (k = 1.0) and continuous variables (ICC = 0.99). Any disagreements between the authors were resolved through discussion. The author made unsuccessful attempts to contact study authors who had missing information. All authors of studies with missing data (k = 9) were contacted for additional information.

Statistical Analyses

All study analyses were completed in the statistical program Comprehensive Meta-analysis (CMA; [41]).

Cohen’s d and Hedges’ g

Standardized mean differences of anxiety scores at post-treatment were used to determine the effect size of studies that reported a comparison group. Standardized mean difference was used because the studies included in the meta-analysis did not consistently use the same anxiety scale. In studies where there was an absence of a comparison group, mean change scores were used to determine effect sizes. In the case where more than one reporter or more than one measure was reported in the study, effect sizes were combined and averaged. Cohen’s d was calculated using the available data. Then, all effect sizes were converted to Hedges’ g and a 95 % confidence interval was calculated using CMA. Hedges’ g was used, as it corrects for biases due to small sample sizes which is not assumed under Cohen’s d. Hedges’ g < .5 indicate a small effect size, g = 0.5–0.8 indicate moderate effect size and g > 0.8 indicate a large effect size [42]. Inverse variance weights were used to weigh each study.

Random-Effects Model and Moderator Analyses

Under the random effects model, the true effect size is assumed to vary from study to study and the summary effect is the estimate of the mean of the distribution of effect sizes. Data were analyzed using a random effects model for two primary reasons. First, it was expected that the studies included in this meta-analysis would differ on their study characteristics, resulting in varying true effect sizes. Second, the random effects model allowed the findings of the meta-analysis to be generalized beyond the studies included in the analysis. In other words, the use of a random effects model would allow findings to be extrapolated to studies not included in the present meta-analysis. Heterogeneity was assessed using visual inspection of the forest plots and the Q statistic. Publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot. Orwin’s Fail Safe N was used to determine the number of un-retrieved trials required to reduce the overall effect size to a low treatment effect size. Categorical moderators were analyzed by examining overlap in confidence intervals.

Power Calculations

Using the random effects model of 14 studies with an average of 22 participants in the CBT intervention condition, and 20 participants in the control condition, there was a power of 0.99 to detect a large treatment effect size of 0.8.

Results

Included and Excluded Trials

A total of 430 references was identified through electronic searches of “Google Scholar”, “PubMed”, and “PsychInfo”. After inspection of titles and abstracts, 410 references were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria and/or were duplicates (see Fig. 1). The remaining 20 references were retrieved for further review, from which six more manuscripts were excluded because they were studies that included adults, reduction of anxiety was not their primary aim and/or effect sizes could not be calculated based upon the information provided.

Eight of the 14 studies were randomized controlled trials comparing CBT to a waitlist [18, 22, 24, 27, 28, 44–46]. Three of the 14 studies were randomized controlled trials comparing CBT to treatment as usual [19, 23, 47]. One of the 14 studies represented a randomized controlled trial comparing CBT to a control group that received a non-CBT treatment, the Social Recreational Program [48]. Two of the 14 studies were open trials [49, 50].

Participants

Collectively, the 14 studies had a total of 511 participants. Two hundred eighty-three participants received CBT and 228 received the following: treatment as usual (n = 52), waitlisted (n = 172), or enrolled in the Social Recreational Program (n = 34). The sample size of the studies ranged from 6 to 71 participants. Of the studies that reported gender distribution, most of the participants were male (n = 422, 83.6 %) and the remaining participants were female (n = 83; 16.4 %). The ages of the participants varied from 7 to 17 years (M = 11.10 years). Of the studies that reported ASD diagnosis distribution among its participants, 191 (41.4 %) participants were diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, 150 (32.5 %) participants were diagnosed with autistic disorder, 81 (17.6 %) participants were diagnosed with PDD-NOS, and 39 (8.5 %) participants were labeled as “high functioning ASD”. Of the studies that reported anxiety diagnoses among its participants, the following anxiety disorders were reported: social phobia (SP) (n = 160; 33.5 %), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (n = 133; 27.8 %), separation anxiety disorder (SAD) (n = 79; 16.5 %), specific phobia (Specific) (n = 51; 10.7 %), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) (n = 42; 8.8 %), agoraphobia with or without panic (n = 6; 1.3 %), panic disorder (PD) (n = 3; 0.6 %), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (n = 3; 0.6 %), and anxiety disorder not otherwise specified (n = 1; 0.2 %).Footnote 1 Of the studies that reported medication usage among its participants, the following medications were reported: anti-anxiety/anti-depressant (n = 66; 31.7 %), stimulant, atomoxetine, or guanfacine (n = 48; 23.1 %), anti-psychotics (n = 34; 16.3 %), alpha blockers (n = 6; 2.9 %), anticonvulsants (n = 4; 1.9 %), mood stabilizers (n = 1; 0.5 %), anxiolytic medications (n = 1; 0.5 %) and other psychotropic or non-psychotropic medication that were not specified (n = 48; 23.1 %). See Table 1 for study and participant characteristics.

Intervention Characteristics

The duration of CBT sessions ranged from 60 to 120 min and trial periods lasted from 6 to 32 weeks (M = 14.79 weeks). Therapy was conducted by graduate students, individuals who held postgraduate degrees in psychology, clinical psychologists, and/or highly trained therapists. Seven studies conducted CBT in individual child sessions with or without parents [18, 19, 24, 43, 45, 46, 49]. Six studies conducted CBT in group sessions with or without parents [22, 23, 27, 44, 47, 48] and one study conducted CBT in individual and group sessions [28]. Common CBT components reported included: psychoeducation (e.g., recognition of anxious feelings in oneself and others, recognition of anxiety triggers, recognition of somatic reactions to anxiety), cognitive restructuring, relaxation techniques, creation of the fear hierarchy, exposures to feared stimuli, and social skill development. Sessions were often taught through role play, visual aids, structured worksheets, social stories, and video modeling and a variety of reinforcement strategies was used (e.g., token system, engaging in child’s restricted interest). Treatment protocols were based on manuals and/or books that modified CBT to be appropriate for youth with high-functioning ASD. These protocols included Cool Kids [50], Facing Your Fears [23], Behavioral Interventions for Anxiety in Children with Autism (BIACA; [17]), Coping Cat [51], Multimodal Anxiety and Social Skill Intervention for Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder (MASSI; [20]), Exploring Feelings [52], and Building Confidence [46]. See Table 2 for the treatment manuals and treatment components reported by each study.

Dependent Variables

The primary anxiety outcome measures that were used included: Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule Clinical Severity Rating (ADIS-IV CSR; [34]) (k = 9), Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory-4 Anxiety Scale (CASI-Anx; [15]) (k = 1), Clinical Global Impression-Severity scale (CGI-S; [35]) (k = 2), Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; [36]) (k = 3), Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS; [37]) (k = 4), Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale-Total Anxiety (RCADS; [53]) (k = 1), Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; [38]) (k = 1), Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED; [39]) (k = 1), and Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS-P/C; [40]) (k = 6).

CBT Treatment Efficacy

A random-effects meta-analysis revealed a statistically significant treatment effect for CBT for anxiety in youth with high-functioning ASD (g = −0.71, 95 % confidence interval [CI] −1.10, −0.33, z = −3.67, p < .001) with significant heterogeneity [Q (13) = 102.27, p < .001, I2 = 87.29 %]. See Fig. 2 for treatment effect sizes.

Visual inspection of the funnel plot identified one study as an outlier [22]. When the study was removed, the treatment effect was lower (g = −0.47, 95 % CI −0.66, −0.28, z = −4.84, p < .001), but was still statistically significant.

Moderators of Response

Anxiety Informant

Effect sizes did not significantly differ across anxiety informants: child (g = −0.60, 95 % CI −1.17, −0.03, z = −2.05, p < .05), parent (g = −0.82, 95 % CI −1.34, −0.30, z = −3.11, p < .01), and clinician (g = −1.23, 95 % CI −1.19, −0.55, z = −5.29, p < .001). See Fig. 3 for the forest plot of effect sizes by anxiety informant. Removal of the outlier did not yield significant differences in effect sizes across anxiety informants.

Treatment Modality

Effect sizes did not significantly differ across treatment modalities: group sessions with or without parents (g = −0.75, 95 % CI −1.50, −0.003, z = −1.97, p = .05) and individual sessions with or without parents (g = −0.62, 95 % CI −0.92, −0.36, z = −4.44, p < .01). See Fig. 4 for the forest plot of effect sizes by treatment modality. Removal of the outlier did not yield significant differences in effect sizes across treatment modality.

Assessment of Publication Bias

Visual inspection of the funnel plot with and without the outlier suggested no evidence for publication bias. See Figs. 5, 6 for the funnel plots.

Publication bias was also assessed using a conservative and meaningful analysis, Fail-safe N [53] which reflects the number of unretrieved studies required to reduce the overall effect size to a specified effect size. In this study, the specified effect size was 0.4 signaling a low treatment effect size. Orwin’s Fail Safe N identified 118 unretrieved studies with the outlier included and 78 unretrieved studies with the outlier removed suggesting that effect sizes observed in the present study are likely to be robust.

Sensitivity Analyses

Using CMA, overall treatment effect size was calculated after removal of each study listed. Removal of each study yielded statistically significant moderate to large overall treatment effect sizes (g range −0.66 to −0.77) with the exception of Chalfant et al. [22]. See Fig. 7 for the forest plot of this sensitivity analysis. Removal of the two open trial studies [48, 49] yielded a moderate effect size (g = −0.76). Removal of child reports which reported the lowest effect sizes revealed that the overall effect size increased from a moderate effect size (g = 0.71) to a large treatment effect (g = −0.84, 95 % CI −1.26, −0.42, z = −3.95, p < .001).

Discussion

The present study builds on Sukhodolsky et al. [26] by providing an updated assessment of CBT for anxiety in youth with high-functioning ASD using meta-analytic methods, as well as explores possible moderators of treatment response. This study identified 14 studies involving 511 participants with high-functioning ASD. All studies used in Sukhodolsky et al. [26] were included in the current meta-analysis. As hypothesized, CBT had a moderate treatment effect size (g = −0.71). Inspection of the funnel plot revealed no evidence of publication bias. In randomized controlled trials, CBT was superior to control conditions (e.g., wait-list, treatment as usual) and had a moderate treatment effect (g = −0.76, 95 % CI −1.20, −0.31). Based on a visual inspection of the forest plot and Q statistics, the observed heterogeneity was largely attributed to the inclusion of two studies [22, 46], which reported greater treatment effect sizes than the other studies included in the meta-analysis (g = −3.48 and g = −2.06, respectively). Removal of the study’s outlier [22] yielded a significant but lower effect size, reducing the overall effect size from a moderate to small effect. Although this outlier contributed substantially to the overall effect size, the removal of this outlier and the remaining statistically significant effect size suggests that the efficacy of CBT for anxiety in youth with ASD remained fairly robust. Unlike the other studies included in this study, in Chalfant et al. [22], each session lasted an average of 2 h over a 12 week period and had group sessions that included a large number of youth per group (6–8 per group). Other factors not explored in this meta-analysis or other factors not reported by the study may explain this large effect size (e.g., treatment fidelity, medication usage, homework compliance). Unlike the other studies included in this study, in Fujii et al. [46], CBT was administered over 32 weeks, which is notably longer than the usual 12–16 weeks commonly reported by the other studies. It is possible that the extended period of CBT sessions was associated with more robust effects, as participants may have had more time to practice skills learned in treatment sessions than in the other studies included in this meta-analysis. However, the relationship between treatment length and treatment outcomes has not been systematically examined in youth with high-functioning ASD and co-occurring anxiety. Due to the limited number of studies included in this meta-analysis, treatment length was not explored as a moderator of treatment outcomes.

With one exception, treatment effects were positive across studies. Unlike the majority of the studies included in this meta-analysis, Ooi et al. [48] reported that youth with ASD reported a decrease in overall anxiety symptoms and parents reported an increase in overall anxiety symptoms at post treatment. As advised by the authors, these results should be interpreted with caution because of the study’s small sample size of participants (n = 6) and open trial nature in which multiple other factors may contribute to findings (e.g., individual differences among patients).

The secondary aim of this study was to evaluate whether the observed variability in effect sizes was the result of anxiety informant and treatment modality. Moderator analyses revealed that anxiety informant (i.e., child, parent and clinician) and treatment modality (i.e., group sessions with or without parents versus individual sessions with or without parents) were not significant moderators of treatment response. Group administration of CBT with or without parents yielded a large treatment effect (g = −0.75, k = 7) and individual administration of CBT with or without parents yielded a moderate treatment effect size (g = −0.62, k = 7) but overlap in confidence intervals revealed that they were not statistically significantly different. These findings suggest that individual and group administration of CBT for anxiety in youth with high-functioning ASD are similarly efficacious. Group administration of CBT can have several benefits including improving treatment access, normalization of anxiety symptoms, peer and social support, and increased motivation, acceptability, accountability, and self-efficacy [54]. Individual administration of CBT can also have several benefits including the ability to tailor to the needs of the youth and family members (e.g., modifying treatment protocol to incorporate comorbid symptoms), increase in confidentiality and likelihood of patient disclosure, and personalized exposures and feedback which may contribute to increased acceptability. Individual child and family characteristics should be considered when determining which treatment approach is most beneficial for a particular youngster.

Sensitivity analyses revealed that removal of child reports, which yielded a majority of the lowest effect sizes reported (g range −0.03 to −2.97), resulted in a larger effect size than when these effects sizes were included in the analyses (g = −0.84 vs. g = −0.71). In six of the eight studies that included child reports, the child reported low treatment effect sizes (i.e., g < .50). In five of the seven studies that included child, parent and/or clinician reports, the child reported lower treatment effect sizes compared to parent and/or clinician reports. Thus, the true effects of CBT may in fact be higher when reducing potential variability in reporter. A previous meta-analysis of CBT trials for anxiety in typically developing youth found that youth often reported lower treatment effect sizes than their parents’ reports [54]. These results are concordant with previous studies that have reported poor parent/clinician and child diagnostic agreement on anxiety measures in typically developing youth (e.g., ADIS; [55]) and youth with ASD (e.g., ADIS; [31]). It may be that children with ASD have difficulty reporting on their symptoms due to limited insight into symptoms and/or treatment effects, difficulty reporting on internal states, and secondary to the effects of comorbidity (e.g., inattentive youth may have difficulty participating in evaluations).

The current findings of moderate to large effect sizes are in line with the findings of current meta-analyses examining the efficacy of CBT in youth without ASD [21]. The increase in the number of CBT trials for anxiety in youth with ASD suggests growing popularity among clinicians and researchers in using this approach to decrease anxiety. Treatment components tailored to meet the needs of youth with ASD reported by this meta-analysis were similar to the components reported by the previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses (e.g., introspection, social skill development, use of visual aids, systematic reinforcement, creation of fear hierarchy, and exposure to feared stimuli) suggesting that these CBT components are still commonly used to decrease anxiety in youth with high-functioning ASD. Notably, the inclusion of social skill training (e.g. maintaining eye contact, initiating and maintaining conversations, awareness of social boundaries) in CBT protocols for anxiety in youth with ASD may be incorporated to address the social impairments which are commonly present in individuals with ASD. Moreover, social skills training may be particularly beneficial at building self-confidence and social competence [17] and relieving social anxiety symptoms which is common in youth with ASD [4].

The conclusion drawn by past systematic review and meta-analyses [25, 26] that CBT is effective at reducing anxiety in youth with high-functioning ASD was also supported by this study. Families and clinicians who use CBT as a treatment option should expect—on average—moderate treatment gains. Although anxiety informant and treatment modality were not statistically significant moderators of treatment effect, other factors not explored in this report may be and thus, are highlighted for future research (e.g., child and parents’ level of motivation, child’s and parents’ level of insight, child’s comorbid symptoms, treatment homework compliance, and child, parent and clinician rapport).

Limitations

This study should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. This meta-analysis included a limited number of studies with significant heterogeneity in treatment effect sizes that could not be explained by the proposed moderators. Due to the limited number of studies and data provided by the studies included in this analysis, moderator analyses should be interpreted with caution, while other potentially moderating variables should be explored. For example, in this meta-analysis, the inclusion of parents in CBT sessions and its effects on CBT efficacy could not be explored, as has been investigated by a previous meta-analysis in typically developing youth [54]. Furthermore, due to inconsistent reporting of participant characteristics across trials and the lack of information provided by some studies examined in this systematic review and meta-analysis, the ability to examine additional moderators coded in this study (e.g., anxiety diagnoses, medication usage) was restricted.

Summary

In light of the critical need for evidence-based treatments for anxiety in youth with ASD, understanding the efficacy of CBT is important to provide treatment guidance. Consequently, this study updated past systematic reviews and meta-analyses by describing and summarizing the characteristics of randomized controlled trials and open trials of CBT for anxiety in youth with high-functioning ASD, examining the efficacy of CBT for reducing anxiety symptoms in youth with high-functioning ASD and examining if CBT efficacy varied as a function of anxiety informant and treatment modality. A moderate overall effect size and significant heterogeneity were found; however, explored moderators did not explain this heterogeneity suggesting that others factors not explored in this study may explain the variability in treatment effect sizes (e.g., homework compliance). Furthermore, removal of child reports improved overall treatment effect size suggesting that youth with high-functioning ASD may report differently from clinicians and parents. Although further research is needed to explore the efficacy of CBT for anxiety in youth with ASD and other possible moderators of this effect, results of this meta-analysis support CBT as an effective treatment at reducing anxiety in youth with ASD. Therapists treating youth with ASD and anxiety can continue to substantiate their choice of CBT in the treatment of anxiety and expect significant albeit moderate improvements.

Notes

Autism Spectrum Disorder diagnoses and anxiety diagnoses were based upon the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th, edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR).

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn (DSM 5). American Psychiatric Press, Washington

Gillott A, Furniss F, Walter A (2001) Anxiety in high-functioning children with autism. Autism 5:277–286

Simonoff E, Pickles A, Charman T, Chandler S, Loucas T, Baird G (2008) Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr 47:921–929

Ung D, Wood JJ, Ehrenreich-May J, Arnold EB, Fujii C, Renno P et al (2013) Clinical characteristics of high-functioning youth with autism spectrum disorder and anxiety. Neuropsychiatry 3:147–157

van Steensel FJA, Bogels SM, Perrin S (2011) Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis. Clin Child Family Psychol Rev 14:302–317

Wood JJ, Gadow KD (2010) Exploring the nature and function of anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorder. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 17:281–292

Green SA, Ben-Sasson A, Soto TW, Carter AS (2012) Anxiety and sensory over-responsivity in toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: bidirectional effects across time. J Autism Dev Disord 42:1112–1119

Scarpa A, Reyes NM (2011) Improving emotion regulation with CBT in young children with high functioning autism spectrum disorders: a pilot study. Behav Cognit Psychother 39:495–500

Bellini S (2004) Social skill deficits and anxiety in high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 19:78–86

Farrugia S, Hudson J (2006) Anxiety in adolescents with Asperger syndrome: negative thoughts, behaviorial problems, and life interference. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 21:25–35

Kim JA, Szatmari P, Bryson SE, Streiner DL, Wilson FJ (2000) The prevalence of anxiety and mood problems among children with autism and Asperger syndrome. Autism 4:117–132

Weisbrot DM, Gadow KD, DeVincent CJ, Pomeroy J (2005) The presentation of anxiety in children with pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 15:477–496

Chamberlin B, Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E (2007) Involvement or isolation? The social networks of children with autism in regular classrooms. J Autism Dev Disord 37:230–242

Muris P, Steerneman P, Merckelbach H, Holdrinet I, Meesters C (1998) Comorbid anxiety symptoms in children with pervasive developmental disorders. J Anxiety Disord 12:387–393

Sukhodolsky DG, Scahill L, Gadow KD, Arnold LE, Aman MG, McDougle CJ et al (2008) Parent-rated anxiety symptoms in children with pervasive developmental disorders: frequency and association with core autism symptoms and cognitive functioning. J Abnorm Child Psychol 36:117–128

McKay D, Storch E (2009) Cognitive behavior therapy for children: treating complex and refractory cases. Springer, New York

Wood JJ, Drahota A (2005) Behavioral interventions for anxiety in children with autism. University of California-Los Angeles, Los Angeles

Wood JJ, Drahota A, Sze K, Har K, Chiu K, Langer DA (2009) Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized, controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50:224–234

Storch EA, Arnold EB, Lewin AB, Nadeau J, Jones AM, De Nadai AS et al (2013) The effect of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus treatment as usual for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52:132–142

White SW, Albano AM, Johnson CR, Kasari C, Ollendick T, Klin A et al (2010) Development of a cognitive-behavioral intervention program to treat anxiety and social deficits in teens with high-functioning autism. Clin Child Family Psychol Rev 13:77–90

Reynolds S, Wilson C, Austin J, Hooper L (2012) Effects of psychotherapy for anxiety in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev 32:251–262

Chalfant AM, Rapee R, Carroll L (2007) Treating anxiety disorders in child with high functioning autism spectrum disorders: a controlled trial. J Autism Dev Disord 37:1842–1857

Reaven J, Blakeley-Smith A, Culhane-Shelburne K, Hepburn S (2012) Group cognitive behavior therapy for children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders and anxiety: a randomized trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 53:410–419

Sofronoff K, Attwood T, Hinton S (2005) A randomized controlled trial of a CBT intervention for anxiety in children with Asperger syndrome. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 46:1152–1160

Lang R, Regester A, Lauderdale S, Ashbaugh K, Haring A (2010) Treatment of anxiety in autism spectrum disorders using cognitive behavior therapy: a systematic review. Dev Neurorehabilitation 13:53–63

Sukhodolosky DG, Bloch MH, Panza KE, Reichow B (2013) Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with high-functioning autism: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 132:1341–1350

Reaven J, Blakeley-Smith A, Nichols S, Dasari M, Flanigan E, Hepburn S (2009) Cognitive-behavioral group treatment for anxiety symptoms in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 24:27–37

White SW, Ollendick T, Albano AM, Oswald D, Johnson C, Southam-Gerow MA et al (2013) Randomized controlled trial: multimodal anxiety and social skill intervention for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 43:382–394

White SW, Ollendick T, Scahill L, Oswald D, Albano AM (2009) Preliminary efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral treatment program for youth with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 39:1652–1662

White SW, Oswald D, Ollendick T, Scahill L (2009) Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Clin Psychol Rev 29:216–229

Storch EA, May JE, Wood JJ, Jones AM, De Nadai AS, Lewin AB et al (2012) Multiple informant agreement on the anxiety disorders interview schedule in youth with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 22:292–299

Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A (1994) Autism diagnostic interview-revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 24:659–685

Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S (2000) Autism diagnostic observation schedule. Western Psychological Services, Los Angeles

Silverman WK, Albano AM (1996) The anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV—child and parent versions. Psychological Corporation, San Antonio

Guy W (1976) Clinical global impressions, in ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. National Institute for Mental Health, Rockville

March J (1998) Manual for the multidimensional anxiety scale for children. Mult-Health Systems, Toronto

RUPP (2002) The pediatric anxiety rating scale: development and psychometric properties. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41:1061–1069

Reynolds CR, Richmond BO (1978) What I think and feel: a revised measure of child’s manifest anxiety. J Abnorm Child Psychol 6:271–280

Birmaher B, Brent D, Chiapetta L, Bridge J, Monga S, Baugher M (1999) Psychometric properties of the Screen For Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38:1230–1236

Spence SH (1998) A measure of anxiety symptoms among children. Behav Res Therapy 36:545–566

Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H (2005) Comprehensive meta-analysis version 2. Biostat., Englewood

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale

McNally Keehn RH, Lincoln AJ, Brown MZ, Chavira DA (2013) The coping cat program for children with anxiety and autism spectrum disorder: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Autism Dev Disord 43:57–67

McConachie H, McLaughlin E, Grahame V, Taylor H, Honey E, Tavernor L et al (2013) Group therapy for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. doi:10.1177/1362361313488839

Wood JJ, Ehrenreich-May J, Alessandri M, Fujii C, Renno P, Laugeson E et al (2014) Cognitive behavioral therapy for early adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and clinical anxiety: a randomized, controlled trial. Behav Therapy. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2014.01.002

Fujii C, Renno P, McLeod D, Lin CE, Decker K, Zielinski K et al (2013) Intensive cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in school-age children with autism: a preliminary comparison with treatment-as-usual. School Mental Health 5:25–37

Sung M, Ooi YP, Goh TJ, Pathy P, Fung DSS, Ang RP et al (2011) Effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 42:634–649

Ooi YP, Lam CM, Sung M, Tan WT, Goh TJ, Fung DSS et al (2008) Effects of cognitive-behavioural therapy on anxiety for children with high-functioning autistic spectrum disorders. Singap Med J 49:215–220

Ehrenreich-May J, Storch EA, Queen AH, et al (2014) An open trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in early adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabil. doi:10.1177/1088357614533381

Lyneham HJ, Abbott MJ, Wignall A, Rapee RM (2003) The cool kids family program: therapist manual. Macquarie University, Sydney

Kendall PC, Hedtke KA (2006) Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxious youth: therapist manual, 3rd edn. Workbook Publishing, Ardmore

Attwood T (2004) Exploring feelings: cognitive behaviour therapy to manage anxiety. Future Horizons, Arlington

Chorpita BF, Yim L, Moffitt CE, Umemoto LA, Francis SE (2000) Assessment of symptoms of DSM-IV anxiety and depression in children: a revised child anxiety and depression scale. Behav Res Therapy 38:835–855

Ishikawa S, Okajima I, Matsuoka H, Sakano Y (2007) Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Child Adolesc Mental Health 12:164–172

Grills AE, Ollendick TH (2003) Multiple informant agreement and the anxiety disorders schedule for parents and children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 42:30–40

Acknowledgments

The authors of this paper would like to acknowledge the support of Drs. Vicky Phares, Ph.D., and Jack Darkes. Dr. Eric Storch has received grant funding in the last 3 years from the National Institutes of Health, All Children’s Hospital Research Foundation, Centers for Disease Control, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Affective Disorders, International OCD Foundation, Tourette Syndrome Association, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Foundation for Research on Prader-Willi Syndrome. He receives textbook honorarium from Springer publishers, American Psychological Association, and Lawrence Erlbaum. Dr. Storch has been an educational consultant for Rogers Memorial Hospital. He is a consultant for Prophase, Inc. and CroNos, Inc., and is on the Speaker’s Bureau and Scientific Advisory Board for the International OCD Foundation. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicting interests to report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ung, D., Selles, R., Small, B.J. et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety in Youth with High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 46, 533–547 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-014-0494-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-014-0494-y