Abstract

This review provides an overview of an important aspect of early childhood home visiting research: understanding how parents are involved in program services and activities. Involvement is defined as the process of the parent connecting with and using the services of a program to the best of the client’s and the program’s ability. The term includes two broad dimensions: participation, or the quantity of intervention a family receives; and engagement, or the emotional quality of the family’s interaction with the program. Research that includes examination of parent involvement is reviewed, including examples from the Early Head Start Research and Evaluation Project. Factors that influence involvement are noted, including parent characteristics, qualities of the home visitor, and program features. The need for further measurement development and implications of these findings for home visiting programs are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Over the past three decades, many early childhood interventions have attempted to strengthen parents’ resources for nurturing the development of their young children and enhancing overall family functioning, particularly in families with multiple risk factors (Brooks-Gunn 2003; Roberts et al. 1996). Although they vary considerably in scope and theory, most of these programs acknowledge that children’s early years are critical, that child development is optimized within the context of loving and supportive relationships, and that it is important to meet families “where they are” in arranging services (Gomby et al. 1999; Shonkoff and Phillips 2000).

One way many programs literally meet families “where they are” is providing services via home visiting. Spending time with families in their own homes often appears to be an ideal way to understand families’ unique circumstances and interests and to individualize services to maximize available resources. Over 500,000 families are estimated to be involved in the most popular early childhood program models that use primarily home visiting (Gomby et al. 1999).

The concept of home visiting, however, has been the focus of controversy in recent years, with some reviews critical of the effectiveness of home visiting programs (Gomby 2005; Chaffin 2004). The term “home visiting” itself can be confusing, because it refers to a mechanism of service delivery but not to any particular program model or content. One may argue the difficulty in discussing “home visiting” in general when the particulars of home visiting can vary greatly by program context, population, philosophy, staff, and curriculum. Nevertheless, a number of reviews and meta-analyses report on the positive outcomes of early childhood home visiting programs (Daro 2006; Sweet and Appelbaum 2004). Furthermore, logic models of popular early childhood home visiting programs (e.g., Early Head Start, Nurse Family Partnership, Healthy Families America, Parents as Teachers) show many similarities in underlying assumptions, goals, and approaches (Guskin and O’Brien 2006). These commonalities in empirical outcomes and conceptual philosophies support the viability of home visiting, both as a method of service delivery and as an area of research.

This review is focused on an important aspect of early childhood home visiting programs: parents’ involvement in program services and activities. As home visiting programs go about delivering services to families with young children, some parentsFootnote 1 enthusiastically receive these services and commit to a working partnership with staff, while others never get past the initial enrollment meeting. Between these two extremes is a vast range of involvement largely ignored in the early childhood program evaluation literature. There has been little attempt to present a comprehensive overview of parent involvement in home visiting, even though policy-makers and service providers increasingly view it as a central piece of effective intervention to young children and their families (Weiss et al. 2006; US Department of Education 2006).

Early Head Start, a federal initiative currently serving low-income families from pregnancy to child age three, uses home visiting as one of its primary methods of service delivery (Administration for Children, Families 1998; Head Start Bureau 2007). The current authors, as local research partners in the Early Head Start Research and Evaluation Project (Administration for Children and Families 2002; Love et al. 2005), have all grappled with how best to understand parents’ involvement in home visiting programs. Our aim here is to present an organizational model of parent involvement, using illustrative examples from early childhood intervention research. We then discuss features of parents, home visitors, and programs related to parent involvement and provide suggestions for research and practice.

What is Parent Involvement?

There are multiple ways to examine parent involvement and many different terms to describe this concept. Preschool and school programs, focused on the home-school connection, typically define parent involvement by such activities as the parent’s participation in school activities, working with their child on academics, and attending parent-teacher meetings (e.g., Castro et al. 2004; Fantuzzo et al. 2000). But early childhood home visiting programs are different. Services come to the family, and parents (typically mothers) are essential to the entire intervention process; they are the gatekeeper and very often the focus of program services. Under these circumstances, involvement is best understood as the process of the parent connecting with and using the services of a program to the best of the parent’s and the program’s ability.

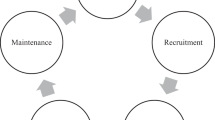

There are certain assumptions in our definition, represented in Fig. 1. One assumption is that involvement is a multi-dimensional construct. No one term or variable adequately describes the complex interactions that make-up the way families experience services. At a minimum, however, involvement includes two broad dimensions. Participation refers to the quantity of intervention, or how much of an intervention a family receives, such as the frequency of home visits or the duration of staff-family contact. Engagement refers to the emotional quality of interactions with the program, or how family members feel about or consider the services they receive, such as the strength of the relationship between family and program staff or the amount of conflict families have with the information presented. These dimensions can be, but are not necessarily, related to each other. For example, length of time in a program, a participation variable, is often used as a proxy for client satisfaction with services, an engagement variable. Table 1 lists the dimensions that are described in more detail in this article.

The second assumption comes from use of the word “process” in the definition. Involvement is not static, and a parent’s connection to their home visitor may be very different from one time point to the next. For most families, participation and engagement in program services will change over time due to a variety of factors, although the dynamic trajectory of service use has not been well examined.

The third assumption is that aspects of the parent or their situation will influence their involvement in services. People bring certain characteristics into an intervention—demographic, socio-emotional, or interpersonal—which influence their connection to services. While some interventions may not expect willing participation (e.g., child protective services), most early childhood home visiting services are voluntary. We assume that people enter into home visiting services wanting to participate, but who parents are will influence the extent to which they involve themselves in the services offered.

The final, and related, assumption is that aspects of the program and staff will influence a parent’s involvement in services. For example, home visitors bring program content to and interact with families in a way that may or may not be a good match for the family’s wishes or needs. Although the term parent involvement implies an intrinsic characteristic of the parent, involvement in services is ultimately a partnership with that program, co-constructed by parent and program staff. The notion of someone being at “fault” when a parent and program do not connect, however, is powerful, and it is important to guard against unduly blaming either the parent or the program when parent involvement is limited.

Why Study Involvement?

There are two primary reasons for studying parent involvement in early childhood home visiting programs. First, it helps us understand the complexity of these programs. Almost 30 years ago, Gray and Wandersman (1980) suggested that instead of asking whether programs are effective, the question should be what characteristics of interventions “are effective in facilitating which areas of competence for which members of the families in which social contexts?” (p. 995). This suggestion has been echoed in more recent calls for researchers to conduct studies that examine which intervention processes are related to specific outcomes for children and families (Guralnick 1997; Gomby et al. 1999; Powell 2005). The stakes for these evaluations are high. When evaluations of home visiting programs show modest or conflicting results, home visiting has been questioned as an effective means of service delivery in early childhood (Gomby et al. 1999; Chaffin 2004).

Unfortunately, most evaluation efforts undertaken to date have focused heavily on documenting intervention outcomes and have rarely provided information on how or why children and families experienced those outcomes. When program process data are reported, they often come in broad strokes. For example, a national evaluation of the Comprehensive Child Development Program (CCDP) reported no implementation data beyond length of program enrollment, despite the fact that a comprehensive study of program processes had been undertaken (St. Pierre and Layzer 1999). This can make it difficult to explain confusing, contradictory, or (in the case of CCDP) the absence of positive findings. Data on the quantity and quality of parent involvement would help clarify the meaning of varying outcomes of home visiting programs and the meaning that families place in these types of services.

The second reason to study parent involvement is to guide program improvement. For example, evaluations of home visiting programs that do include parent involvement data have shown that attrition among participating families is often high and that families rarely receive the intensity of intervention a program is designed to provide (e.g., Gomby et al. 1999). This suggests a need to strengthen program design and to provide technical assistance for program staff to find out why families do not participate more fully and what to do about this reduced participation. Those who are designing home visiting intervention programs for families with young children need information about which program services are valued by which families, which variations in service delivery may be more effective for certain families, and which approaches and techniques used by program staff may more successfully involve families. Research focused on how home visiting programs work and how they involve parents can contribute useful information for practical programmatic decisions (e.g., Daro and Harding 1999; Green et al. 1999; Connell and Kubisch 1998). This seems particularly important for home visiting programs in that providers makes outreach to the families where they live, rather than waiting for parents to come to them. This provides for a broader range of involvement than other service models, as the burden of follow-through is not solely on the family.

What are The Major Dimensions of Involvement?

We define involvement using two broad dimensions (see Table 1). The first, participation, refers to the quantity of contact families have with programs. The second, engagement, refers to the quality of that contact.

Participation

Participation is perhaps the most visible measure of involvement, as receiving contact from a home visitor is a readily observable sign of a parent’s connection to a program. It is the most frequently reported indicator of involvement, although programs will sometimes report participation in terms of program design, or expectations of contact for all families, rather than in actual measured quantity of services received by each family. Participation can be defined in various ways—by amount, frequency, average length, duration, or ratio of contact. We will consider each of these in turn.

Amount of Contact

Amount of contact can be measured simply by the number of contacts that home visitors have with families. However, given the variation in length of visits (see below), the total minutes or hours, summed across contacts, provides a more complete description of the “dose” of services received. Contact between home visitors and parents may not always happen in the home. Visitors may connect with families in other familiar settings (such as parks, laundromats, or clinics) or find that they spend large portions of time with some parents on the phone (Wasik and Bryant 2001). In fact, some programs may exchange face-to-face contact for telephone contact over time as program participants become more independent and self-reliant (Fuddy 1992), or simply because of parent preference, but whether phone contact is the equivalent of in-person contact is not known.

Some programs use a multi-disciplinary approach in which families receive different types of home visits with specific providers. For example, one provider may focus on child development issues, and the other may focus on parent or family support (Luze et al. 2002). Each of these visits represents a separate component of the intervention even when they overlap or are provided concurrently. Home visits may also happen in the context of other services (such as center-based programming) and it is unclear to what extent these services should be viewed separately or in accumulation (Rector-Staerkel 2002).

This suggests that measuring amount is not as simple as it may first appear, necessitating the development of rubrics to deal with different permutations of service contact. For example, the Infant Health and Development Program, a trial of comprehensive services for premature infants and their families, developed an “index of participation” that combined contacts with different elements of the program model, including home visit contacts with families, child attendance in center-based programming, and parent use of support groups (Ramey et al. 1992).

Frequency

Programs vary dramatically in expected schedule of contact. Early Head Start, for example, has weekly home visits as a performance standard, while other programs emphasize bi-weekly or less frequent contact. The participation parameters of many home visiting programs are prescriptive; families are expected to participate at a specified frequency (such as with EHS). Other programs offer more flexible participation options based on the home visitor’s perception of family needs (Fuddy 1992; Daro and Harding 1999; Wagner and Clayton 1999). Other programs may design different kinds of visits made at different frequencies. For example, in one EHS program nurse home visitors were expected to visit monthly, child development home visitors were expected to visit weekly, and family advocate home visitors were expected to visit quarterly (Rector-Staerkel 2002).

There are few studies that have examined variation in frequency of home visits for families with young children. In one report of two studies where Jamaican families were assigned to different visitation schedules for a home-based program to promote child development, some families received weekly home visits, others biweekly visits, and others monthly home visits (Powell and Grantham-McGregor 1989). The actual adherence to the visitation schedule, however, was not assessed. This study also could not disentangle the influence of spacing of contact from amount of contact. For example, how would the experience differ for a family who receives 12 visits over 12 months, compared to one who receives 12 visits over 12 weeks?

Average Length of Contact

As noted above, visits can vary in length as well as frequency. While programs may specify how long each visit should last (for example, 90 min is suggested in Head Start performance standards for each home visit), parents and visitors likely regulate the length of a visit based on family needs or interests. In one EHS program, for example, although the average number of minutes per home visit was 72 min, visits ranged from as short as 30 min to as long as 3 h (Rector-Staerkel 2002). Accumulated, this can make quite a difference in total amount of contact. It is unknown to what extent length of contact matters for home visits. Intuitively it makes sense that longer contact provides greater opportunity for intervention and guidance to families. It is equally plausible, however, that a family might feel supported by brief contact from a home visitor to check up on the family. There may also be negative implications for home visits that run too long (e.g., professional boundary issues).

Duration

Another aspect of participation is the duration of enrollment in the program; that is, how long family members remain active in a program. Although many home visiting programs are designed to provide several years of prevention and early intervention services, the majority of families do not remain enrolled for these extended time periods. For example, Gomby et al. (1999) found in their review of six large home visiting programs that 20%–67% of families left before receiving the full duration of services. In home visiting programs that were part of the EHS national evaluation, from 1/3 to over 1/2 of families dropped out of services before completion, depending on the definition used (Roggman et al. in press).

Duration of enrollment is a fairly imprecise measure of program contact, as families differ in the amount of program contact within the same enrollment period. Also, determining the actual start and stop dates for program participation is not always simple. Families in home visiting programs may remain on home visitor caseloads even if they are not actively participating in services (Wasik and Bryant 2001), often because the home visitor is hoping that the family will reconnect with services. Families may also maintain some form of contact with their home visitor even after program services have officially ended.

Duration can be a categorical variable when families are classified as either completing some threshold of service or as having prematurely dropped out of program services. In an examination of program retention in a Healthy Families America home visiting model in Oregon, families were classified as having “received the program” if they had home visits for at least 1 year (McGuigan et al. 2003). This 1-year cut-off was a meaningful program-specific time point, based on both the average length of stay in the program and the belief that the first year of a child’s life is the key focus for program intervention, even though the Healthy Families model allows families to participate up to 5 years.

Ratio: Completed to Expected Contact

A meta-variable of program participation is the ratio of completed to expected amounts of contact. That is, how much program contact does each family actually receive in relation to the amount of contact specified in a program’s protocol? This type of reporting is not possible for programs that allow great flexibility in visitation schedules. But for programs that provide a standard for frequency of contact (weekly EHS visits, for example), a ratio score provides a comparable rubric for participation across families enrolled for varying lengths of time. If a program’s protocol specifies the expected length of each visit as well, and if home visitors record the length of each contact, then an even more fine-grained statistic for the ratio of total amount to expected amount of contact can be generated.

Ratio statistics are rarely reported for home visiting programs, although they have been incorporated into program implementation reports for the Nurse Family Partnership Program (Korfmacher et al. 1999), Early Head Start (Raikes et al. 2006), and Healthy Start Hawaii/Healthy Families Programs across at least two different trials (Duggan et al. 2004, 2007). One issue is that it can be difficult to distinguish between participants with lower ratios due to early termination or those due to infrequency of contact. In the recent statewide trial of Healthy Families in Alaska, however, Duggan et al. (2007) combined both duration (enrollment at least 24 months) and ratio (receipt of at least 75% of expected visits) to create a more precise measure of whether or not families received “adequate services”.

Documenting Participation

Although participation may seem to be a relatively straightforward quantitative dimension of parent involvement, the many different ways that it can be measured suggest a greater level of complexity. Recent studies have begun examining participation beyond single variables. For example, both duration and amount of contact were used in different Healthy Families programs when examining parent and program factors in client retention (Daro et al. 2003) or program outcomes (Duggan et al. 2007). An examination of the relation between involvement and outcomes in home visiting programs of the Early Head Start Research and Evaluation Project (Raikes et al. 2006) included four measures of participation in its analyses: number of visits, duration of enrollment, intensity of contacts (a ratio indicator), and average length of visits. Although these were reported as separate variables, it is also possible to consider combining different features of participation analytically, whether through creating an index of participation, as was done in the IHDP (Ramey et al. 1992), or through person-centered approaches, such as using multi-stage clustering approaches (e.g., McDermott 1998) to identify subgroups of parents who show similar patterns of participation.

Most home visiting evaluations, however, provide only superficial detail regarding quantity of participation in the description of program methods (Sweet and Appelbaum 2004), making such analyses difficult to undertake. This is likely due to a variety of factors, including space limitations in reports and professional journals and a relative indifference to participation statistics when describing program methods. But adequate documentation of participation in home visitor record-keeping from the beginning is also essential. There are many ways to record participation, and programs will need to decide on a common rubric that makes sense for their activities and does not over-burden home visitors with paperwork. Ideally, management information systems can generate regular reports back to home visitors and their supervisors to track participation over time. This process can be labor-intensive and expensive, requiring dedicated staff time to input and track this information and maintain system integrity. We suggest, however, that collecting this data can help programs target resources to particular clients, as well as provide information useful for program evaluation.

Engagement

The previous section focused on the quantity of parent involvement. Parent involvement also includes qualitative response to a program’s activities and services, which we term engagement (Kazdin and Wassell 1999; Littell et al. 2001; Brookes et al. 2006). Similar to what has been noted by others (e.g., Littell et al. 2001), we view engagement as having both a positive and negative valence. We also discuss engagement within the context of the helping relationship that forms between parent and home visitor.

Positive Engagement

Although simply being available for home visits is a necessary aspect of parent involvement, some level of positive engagement by participants is also needed for program outcomes to be achieved. Attempts to measure this positive engagement have been sporadically attempted over the years, usually employing measures developed specifically for a particular study, often with unknown reliability or validity. This can be seen in the different terms that have been used to describe this concept. Besides using the term engagement (e.g., Belsky 1986), early childhood intervention projects have measured program “taking” (Osofsky et al. 1988), achievement of treatment goals (Barnard et al. 1988), commitment (Korfmacher et al. 1997), ability to work with the home visitor (Heinicke et al. 2000), and program receptivity (Rauh et al. 1988). Program engagement may also be reflected in the level of satisfaction that a parent feels with a program.

The differences among these constructs are unclear. For example, although both satisfaction and commitment suggest an underlying positive reaction to the program, how does the perception that a program is personally valuable (satisfaction) contribute to the internal motivation to invest in the program (commitment)? It is possible that parents could be satisfied about services even if they never fully committed themselves, or feel an obligation to follow through on suggested activities even if the experience is not satisfying. It is a reasonable assumption that parents should like program services in order to get something out of them. We do not, however, have a good sense of what that liking really looks like. A focused attention to delineating these different aspects of positive engagement and the development of reliable and valid measures of engagement would be of considerable benefit to both program and research.

Negative Engagement

Parents do not always have a positive experience in early childhood programs (LeLaurin 1992) and may experience conflict with program staff or dissatisfaction with services they receive. Because most early childhood home visiting programs are voluntary, negative engagement is often viewed in terms of participation: families will ‘talk with their feet’ and leave service prematurely, a particular problem for home visiting services (Gomby et al. 1999). Dropping out, however, is not necessarily due to negative engagement. Families may move out of the program’s catchment area, or simply feel they do not have the time for visits, even if interested (e.g., Kitzman et al. 1997a, b). Many families will also stop receiving services for undefined reasons, becoming unavailable or hard to find (e.g, Korfmacher et al. 1999; Wagner et al. 2000). This suggests that negative engagement should not be defined simply by lack of participation.

Nor is negative engagement merely the lack of positive engagement in home visits, such the parent appearing disinterested or not following through with activities between visits. Negatively engaged families are still actively (albeit unhappily) connected to services. Home visitors sometimes upset or anger a parent, such as by calling child protective services or challenging the parent regarding parenting decisions or life choices (Korfmacher and Marchi 2002). But there is little systematic documentation of these conflicts. Because prevention or support programs typically are promoted as strength-based, such interactions may be viewed as rare, but they are especially important to document in the context of voluntary programs if they lead to a decrease in participation.

Negative engagement may also stem from disappointment that the services families thought they would receive—transportation, books and materials, or child care—are not the services they actually receive (Wagner et al. 2000). Home visitors, in turn, may be disappointed that parents are interested in the program for the “wrong” reasons. In EHS, where performance standards encourage a focus on child development, home visitors may want to spend more time on child-related issues, while mothers may want to talk about personal or family problems that are to them more central. Home visitors in one EHS study described this as a mother’s “gimme attitude” (Brookes et al. 2006), a phrase that connotes a negative engagement, although it is unlikely that parents would view it this way. Thus the valence of engagement can depend on whose perspective is used; providers may view a parent’s actions as resistance even if parents feel they are merely advocating for themselves (Littell et al. 2001). In short, parents may be engaged in home visits, but not reacting in the way that program designers or home visitors expected.

Helping Relationship

Noting the differences in perspectives also underscores the importance of examining the helping relationship. Studies of early childhood services often operationalize engagement within the parent, even though it is more accurate to consider engagement as mutually developed between family and home visitor. Early childhood interventions typically emphasize relationship development between families and program staff members, especially in home visiting programs (Olds et al. 1998; Wasik and Bryant 2001). Despite this, specific conceptualization or measurement of the home visitor-parent relationship is rather limited. Although there are some quantitative self-report measures that have been used, these measures often load onto a single factor of positive feelings and are subject to restricted ranges at the high end of the scale, limiting the measure’s psychometric and programmatic utility (Korfmacher et al. 2007). The few examples of research that focus specifically on how the relationship is described by parents or home visitors (using in-depth interviews or rank-ordering techniques) reveal an emphasis on empathy and friendship (e.g., Korfmacher 2002), and having “someone to talk to who really cares” (Pharis and Levin 1991).

Other intervention fields demonstrate the vitality of the helping relationship and often include both an emotional component and a goal-oriented component. For example, in early intervention for children with identified delays or disabilities there is an emphasis on collaborative partnerships between families and providers. Such partnerships are a hallmark of family-centered services and typically include dimensions of trust, positive communication, and shared responsibility (e.g., Blue-Banning et al. 2004; Dunst and Paget 1991). As another example, psychotherapy relationships have been conceptualized as a working alliance, composed of an emotional bond, agreement on tasks, and expectations for outcomes (Bordin 1979). Research suggests that the quality of the working alliance is a strong predictor of psychotherapy outcome (Horvath and Bedi 2002), particularly when the rating comes from the client, rather than the therapist or an outside observer (Horvath 2000). This is noteworthy, since early childhood home visiting research has generally not emphasized parent reports of program experience, relying instead on ratings of the parent made by the service provider (e.g., Belsky 1986; Heinicke et al. 2000; Rauh et al. 1988), or by an observer reviewing videotapes (Roggman et al. 2001), or through archived case notes (Korfmacher et al. 1997; Osofsky et al. 1988).

There are, of course, important differences between early childhood home visiting, psychotherapy, and early intervention. In psychotherapy or early intervention, clients typically seek out program services because of particular concerns, such as emotional distress or identified delays or disabilities in their child. Often there is a payment or fee for services rendered. Home visiting programs, in contrast, tend to be freely given community services that (in many research trials) seek out and recruit families and offer more general forms of family support. These differences, in turn, lead to probable differences in expectations for services and in the relationships that are formed between parents and program staff.

Still, these and other treatment fields provide useful starting points in further exploring the helping relationship in early childhood home visiting. For example, the extent to which service goals are mutually developed between home visitor and family may vary meaningfully across families, providers, and program models. Helping home visitors conceptualize the partnership between parent and home visitor as involving both an emotional component (being listened to and cared about) and a working component (agreeing on what needs to happen) could also enrich program practice.

Documenting Engagement

The first and most obvious suggestion that emerges from our review is that programs should actually record parent engagement, in addition to documentation of participation, as part of their ongoing tracking of enrolled families. One way is through periodic ratings made by home visitors. But we also suggest that programs bring in alternate perspectives on parent engagement beyond the home visitor. Home visiting research has relied to great extent on the visitor to provide information on client involvement, both for participation and engagement. A justification for this approach is that providers have a bank of experiences (in their current and past caseloads) against which to compare the current family’s involvement, while clients typically have not had previous home visiting experiences.

The few examples examining the relations between parent and visitor report of program involvement show either a non-significant or a weak correlation (Roggman et al. 2001; Raikes et al. 2006). This may be because of reduced variance due to restricted range, a problem with many engagement measures. But it may be that parents and providers simply have different points of view, as has been shown in reports on program content covered in home visits (Luze et al. 2002). As Powell (2005) has noted, staff reports of parent engagements in parent training sessions do not necessarily relate to parent follow-through on program activities between sessions.

Having multiple perspectives also includes allowing outside observers to view home visits, either in-person or through recordings. Only a few studies of early childhood home visiting have used direct observation (e.g., McBride and Peterson 1997; Roggman et al. 2001; Luze et al. 2002), despite improvements in technology that increase the ease of this data collection. Although there may be some resistance to direct observation on the part of the program providers, there are ways to resolve staff concerns. Roggman et al. (2001), for example, demonstrate how videotapes of home visits developed for research purposes can become important tools for home visitors to use in their own supervision to identify challenging or difficult moments or interchanges that elicit positive engagement.

Finally, there is a strong need for measurement development. Defining common terms and developing items that accurately capture and differentiate engagement constructs would be a welcome advance, such as been done with parent involvement measures used in preschool settings (e.g., Fantuzzo et al. 2000). The measures used in home visiting have not been adequately tested across different program models. They also appear to have difficulty in capturing the full valence of engagement, with both parent and staff ratings producing positively biased scores. Although these measures may still have some criterion and predictive validity (Korfmacher et al. 2007), the restricted range in their scores limits their usefulness both empirically and clinically. This suggests the need to also develop items sensitive enough to pick up ambivalent or negative feelings that may otherwise go unexpressed. This is not just an issue with empirically based measures. Programs, as part of their information-gathering process, may find it easier or more convenient to use positively involved parents to give them program feedback (such as those parents who serve on policy councils). Gathering information from those families who are less involved (including families who have withdrawn from services, such as through exit interviews) or who have had negative experiences would provide a more complete picture of program operations that could be used to improve program practice.

Relations Between Participation and Engagement

Although we have so far considered participation and engagement as different dimensions of involvement, it is worth considering how they are related to each other. Achieving regularity and stability in on-going contact between provider and parent is often a sign that the relationship has reached a new level of functioning (Greenspan et al. 1987). In this way, participation may demonstrate a parent’s engagement or commitment to services. For example, the duration of family enrollment in EHS programs was related to the quality of parents’ engagement in home visits (rated by staff) (Roggman et al. in press). The sheer amount of participation also likely influences perceptions when participants or providers make retrospective reports of family engagement over the length of a service period (see Raikes et al. 2006).

But it also is reasonable to view participation and engagement as separate constructs. Parents may be available for home visits without being very engaged. In a study of the HIPPY program, researchers found considerable variation in engagement among families who remained enrolled in their program; some families allowed visits to continue even though they were no longer enthusiastic about the program (Baker et al. 1999). And likewise, parents may have high enthusiasm about the program even if they only manage to participate for brief periods of time (McAllister and Green 2000). In the national evaluation of EHS, measures of participation were only weakly related to home visitor ratings of the parent engagement during home visits (Raikes et al. 2006).

A study of one particular EHS program that used home visiting created a model that dichotomized participation and engagement (reported by staff) into high and low levels, creating four categories of involvement: highly involved (high participation and engagement), uninvolved (low participation and engagement), superficially involved (high participation but low engagement), and sporadically involved (low participation but high engagement). An examination of families who fell into these four categories showed that they differed in meaningful ways. Superficially involved parents, for example, were a particularly high-risk group, with low feelings of personal mastery and high life stress (Robinson et al. 2002). These mothers were available for home visits, but this availability did not seem to represent an enthusiasm or acceptance of the program.

This study suggests that engagement and participation are separate, but linked constructs. Programs may find it helpful to consider them together in order to identify families who are highly involved and those who are not. This identification could help program staff see patterns in the involvement of families and develop plans for providing extra support or new strategies where needed, such as with the higher-risk families as identified by Robinson et al. (2002).

Involvement as a Dynamic Construct

One complication in considering parent involvement, both for research and practice, is that participation and engagement vary over time, and these variations may have important effects on program outcomes. Case studies and training materials certainly demonstrate this (Wasik and Bryant 2001; Kitzman et al. 1997a, b; Brookes et al. 2006), but it is not clear the extent to which this change over time is predictable and understandable. The emphasis in empirical home visiting research is on stasis, using single variables to sum up entire intervention time periods. There is little examination of longitudinal patterns of parent involvement in early childhood home visiting services.

Time can be measured within a series of distinct periods. We could measure each individual’s participation over multiple points in time: P1, P2, P3 (and so on), with each point representing a time period. We could also measure engagement over multiple points in time: E1, E2, E3, and so on (see Fig. 1). Dynamic processes are captured through repeated measurements that are related using longitudinal and time-series analysis methods. The primary advantage and challenge of using dynamic methods is that it forces us to think about how the repeated measurements of a single individual are related to one another within a dimension; for example, how are P1, P2, and P3 related to each other? It also forces us to think about how the repeated measures are related between dimensions across time. For example, does negative engagement measured at one time point, E1, relate to decreased participation at a later time point, P2?

There is need for analytic paradigms that identify patterns of change over time (Collins and Sayer 2001). Analytic techniques that examine the individual, longitudinal trajectories of children or parents are being used in early intervention research, but typically only for examining outcomes. These techniques have not been applied to examining involvement in interventions over time. On the one hand, implementation data seem well suited to these statistical approaches, given that implementation studies often capture data at multiple time points, in some cases on a visit-by-visit basis. On the other hand, variability between time points, as well as the sheer number of observations, can create modeling challenges. Qualitative research methods are also a possibility for examining parent involvement over time. Ethnographies and case studies, for example, have illuminated many of the intricacies of caregivers’ relationships with service providers (Brookes et al. 2006; Greenspan et al. 1987).

Another important temporal consideration is the use of prospective and retrospective reports. That is, we might query families and home visitors concurrently to their visits (e.g., asking home visitors to rate mothers and record participation after very visit and asking parents to rate how much they liked the visit), or we might ask participants to recollect their experience during a circumscribed period of time. Retrospective ratings are easier to collect than session-by-session ratings, although they rely on the recall ability of staff and participants and may be subject to attribution bias (see below). They also allow respondents to consider in toto participation and engagement for the particular service period. For example, clients who are highly engaged and participate for multiple sessions could be seen as more involved than clients who are highly engaged but seen only one time. In their analysis of involvement in EHS home visiting programs, Raikes et al. (2006) found a significant but weak correlation between staff engagement ratings on weekly encounter forms and staff ratings of global engagement taken at the end of the program. The association was much stronger, however, between the global rating and different participation measures, such as number of visits or duration in program, suggesting these retrospective ratings were strongly influenced by amount of contact.

What Influences Involvement?

So far, we have defined the elements of involvement in home visiting early childhood services. The following section describes factors that influence involvement (see Fig. 1). We focus in particular on features of the participating parties in these services—the home visitor and the parent, before considering programmatic elements that may influence involvement.

Features of the Home Visitor

Home visitors represent the program to the family. They are typically the ones who spend time with families, and they are responsible for interpreting and conveying the program content or curriculum to the participants. In spite of this, there is little research focused on qualities of the home visitors. We highlight four features of home visitors that, in particular, affect family involvement in the program: background, program match, client match, and supervision.

Background of the Home Visitor

Because early childhood interventions can be implemented across many disciplines, service providers represent a wide range of professional orientations, although home visitors in early childhood programs are often paraprofessionals. The term paraprofessional generally refers to service providers who do not have degrees or formal training in a professional service, such as counseling, social work, nursing, medicine, psychology, or child development. Some programs may use “paraprofessionals” with college education or degrees from a non-social service field (see Wasik and Bryant 2001, for review). Paraprofessionals tend to come from the same community or have similar life circumstances as the program participants, so that they, too, have experienced the struggles associated with living in similar conditions.

There is little empirical evidence regarding how professional training status influences parent involvement in intervention services, including home visiting programs (see Hans and Korfmacher 2002). This is striking given how central the “social distance” rationale is to the use of community-level workers. Although paraprofessionals are typically hired because of their strong connections to the community and their ability to connect with those distrustful of formal services, rarely has the influence of these characteristics been tested. There are a few, albeit contrasting, exceptions. A study of the implementation of the Nurse Family Partnership model by nurse or paraprofessional home visitors showed that although nurses and paraprofessionals did not differ in how their clients rated the quality of the helping relationship, families visited by paraprofessionals had less contact with the program and dropped out sooner and in greater numbers (Korfmacher et al. 1999). In contrast, analysis of program participation in Healthy Families America suggested that the educational level of the visitor did not influence participation but experience did: Experienced home visitors had more contact and retained more families than those with less experience, regardless of professional background (Daro et al. 2003).

As the above study by Daro and colleagues suggest, experience may be a more important variable to examine than professional degree as a contributor to parent involvement (see also Gomby 2007). Professional background is likely a proxy for other variations among service providers, such as client-provider “match,” agreement with program model, or relationship development skills. None of these have received the attention or study they deserve, especially in examining a family’s emotional engagement, where it is reasonable to expect that a home visitor’s skill and personal qualities have strong influence in the context of relationship-based program models.

Match with Program

The home visitor’s background exists in the context of the program itself. For example, in the Nurse Family Partnership study noted above, it is possible that the lesser participation of families with paraprofessional home visitors was due to the home visitors using a program model that was not well suited to their abilities and strengths. Supervisors of the paraprofessionals in this particular trial reported that the home visitors were not comfortable with some of the program’s parenting curriculum (Hiatt et al. 1997). Other studies also show that a service provider’s lack of acceptance of their program model’s theory of change can influence how services are implemented (Nauta and Hewett 1988; Hebbeler and Gerlach-Downie 2002), which may also affect parents’ enthusiasm and ultimate involvement.

Match with Clients

As noted above, a close similarity in background with program families is a key rationale in the hiring of community members as home visitors in early childhood programs. There are many other dimensions on which home visitors and parents may be matched. Most home visitors, for example, are women, partly because of conventional belief that mothers (the primary adult participant in early childhood programs) would be more comfortable relating to and accepting parenting information from another woman (see Wasik and Bryant 2001, for discussion), especially if that woman were a mother herself. A qualitative study of two EHS programs suggested that mothers appreciated it when home visitors had backgrounds similar to themselves, including motherhood (Brookes et al. 2006). A quantitative analysis of Healthy Families America home visiting programs suggested that a shared parenting background led to increased participation for Latina mothers but not African-American or European-American mothers (McCurdy et al. 2003).

It is also possible that mothers may feel more comfortable being visited by someone with whom they share an ethnicity or culture. The only study that has systematically examined this issue in early childhood home visiting found that match predicted participation, but only for African-American participants (McCurdy et al. 2003). Cultural sensitivity may be more important than a strict cultural match, given the diverse populations that home visitors often serve (Slaughter-Defoe 1993). There is some evidence that parents who view their home visitor as being more culturally competent show higher program involvement (Green et al. 2004), although it can also be argued that an intensive emphasis on cultural differences may interfere with appropriate delivery of services. In one qualitative study, for example, nurse home visitors serving a largely African-American population were more hesitant to suggest program interventions, even those they considered helpful, for fear of seeming culturally insensitive (Kitzman et al. 1997a, b).

Supervision and Training

The on-going support that home visitors receive in terms of supervision and training is crucial in the ability of the provider to engage and retain families in home-based programs (Parlakian 2001; Wasik and Bryant 2001). The most significant predictor of families staying in Oregon Healthy Families programs, more than any other measured characteristic of home visitors or families, was the hours per month of supervision received by the family’s home visitor (McGuigan et al. 2003). To the extent that home visiting programs rely on paraprofessional or inexperienced staff for service delivery, supervision and on-going professional development are especially important.

Given this, it is noteworthy how few studies have examined the training and supervision of home visitors, both in terms of promoting skill development (see Kelly et al. 2000, for an exception) and in terms of maintaining ongoing relationships with families. Both access and type of supervision received are relevant, in that the importance of self-awareness and reflective capacity in providers has been emphasized for ongoing work with families (Heffron et al. 2005; Parlakian 2001). Nevertheless, it is empirically unknown to what extent reflective supervision provides value over administrative or didactic supervision. This is an area where a carefully designed study could have a strong influence on future program design.

Features of the Parent

Although the weight of involvement does not rest entirely on their shoulders, parents obviously are central in their own participation and engagement in home visiting services. Family context, demographic features and psychological functioning of the parent have been studied in relation to program involvement. We suggest, however, that two additional intentional features—need and motivation—are important to consider as well.

Family Context

The primary caregiver (whom we have been calling the parent) is not the only client in a home visiting intervention. Other, non-primary caregivers, such as non-custodial fathers or grandparents, as well as the young child and his or her siblings, may be the focus of support, depending on the nature of the program, its goals and objectives, and its implementation strategies. The development of a positive and healthy working relationship with important members of the family’s network may facilitate the target member’s participation in the program and keep her or him connected to home visiting services (Cole et al. 1998; Wasik and Bryant 2001; Brookes et al. 2006). Even if other family members are not actively involved in visits, they may still influence the involvement of another family member who is. Fathers’ or grandmothers’ attitudes about an intervention program, even if not overtly expressed, may affect how much a mother engages or participates in the program. For example, Parents As Teachers mothers and home visitors noted in focus groups the challenges faced when child development information ran counter to family beliefs or traditions (Wagner et al. 2000).

Demographic Features

There has been a broad list of demographic features studied in relation to involvement, including age, education, employment, marital status, and income, but the characteristics affecting parent involvement vary across studies. Teen and single parent status, education, and ethnicity were all associated with different indicators of participation and engagement in the national EHS evaluation (Raikes et al. 2006). Parents who spent long hours at work had less time to participate in a local EHS program (e.g., Roggman et al. 2002), but parents with higher aspirations for education or employment reported higher involvement in the HIPPY program (Baker et al. 1999).

Age of the mothers was important to their program participation in Healthy Families America, as reported in a multi-site evaluation (Daro and Harding 1999); however, at some program sites teenage mothers were more likely to drop out than older mothers, while at other sites younger mothers were perceived by staff as easier to engage than older mothers. Although there is some research to suggest that teen mothers show less participation and engagement (Osofsky et al. 1988; Wagner et al. 2001), it is not always clear if this is due to their maturity level or if other features of their lives (such as poverty or single parenthood) decrease their ability or interest to connect to services. As these examples suggest, demographic characteristics may predict program involvement, but they are likely proxies for variables more directly relevant to participation and engagement in home visiting services, such as life circumstances or personal characteristics of the parents.

Psychological Characteristics

Personal features will affect involvement, particularly engagement, in an intervention program. For example, parents who are functioning better psychologically, with fewer symptoms of depression and more feelings of security in close relationships, are generally more likely to use emotional and instrumental support (Florian et al. 1995; Wallace and Vaux 1993). They may more readily form collaborative partnerships with staff in early childhood intervention programs (King 1995; Brookes et al. 2006). In a study of one relationship-based home visiting intervention, a risk factor for low parent engagement was an insecure working model regarding attachment relationships (Korfmacher et al. 1997). Others studies have shown that mothers rated by home visitors as more difficult to engage in services had high levels of unresolved and difficult memories of their early caregivers (Spieker et al. 2000) or more relationship insecurity (Heinicke et al. 2000). Similar results were also shown for fathers in one Early Head Start program (Roggman et al. 2002).

Need

Demographic features and personal functioning are often expressed in terms of risk. There is some evidence that families with more risk factors for negative developmental outcomes (e.g., less education, younger, more impoverished, fewer personal resources) tend to benefit more from home visiting and early childhood intervention programs (see Gomby et al. 1999), possibly because there is greater opportunity to show change. But a greater opportunity to benefit does not necessarily translate into increased involvement. Families with risk factors such as extreme poverty, family violence, or housing struggles may find it difficult to be involved in an early childhood intervention program.

Although some studies do find a direct link between risk status and involvement (Green et al. 1999), it does not appear to be a simple linear correlate. In the evaluation of Hawaii’s Healthy Start program, family participation in a threshold of visits (12 or more) was predicted by a constellation of factors measured at intake, including fathers being judged to be “extremely high-risk”, and mothers judged to be less than extremely high-risk (Duggan et al. 1999). Thus, it was neither simply high-risk nor low-risk parents who were more involved, a finding consistent across all three of the participating Healthy Start administering agencies. Data from two different trials of the Nurse Family Partnership program showed a curvilinear relationship between psychological resources and number of home visits (Olds and Korfmacher 1998). Mothers with very low and very high psychological resources had more visits than those with a medium amount. One interpretation is that this curve reflected both that the nurses perceived an increased need in low resource mothers (and thus visited more), and that high resource mothers were better organized (and thus more available for visits).

This suggests that risk by itself is limited in helping us understand parent involvement. Instead, a parent’s need for services may influence their involvement. Greater risk is a sign of greater need, as families with more indicators of negative outcomes likely need services more than those without these risk factors. But is need internally or externally perceived? Some programs, such as Healthy Families, use family risk screeners to determine eligibility for services. Home visitors may also perceive increased need and reach out more to these families, as did the nurses in the study reported by Olds and Korfmacher (1998). We argue, however, that involvement is more closely tied to the parents’ internal perceptions that they need the services, more so than an externally derived signifier of risk.

Motivation

Related to need and risk is motivation: the client’s desire to seek, accept, and continue program services. It may seem obvious that more motivated parents will be more involved, but understanding why parents agree to participate and what underlies their motivation to stay involved is critical to understanding their involvement. Many programs (especially those that are part of randomized trials) actively recruit parents into voluntary services; that is, the program “comes to them” rather than being pursued by the parent. This makes understanding motivation somewhat different than in the context of treatment programs that are either mandated (e.g., by the court or child welfare system) or sought out by parents who have an initial interest in the program and what it has to offer (such as early intervention services or treatments for children with behavior problems).

McCurdy and Daro (2001) have applied a “readiness to change” model to understanding parents’ intention to enroll in voluntary family support services. They suggest that parents who feel a need to focus on parenting and who therefore have a higher “readiness to change” their parenting behavior, are more likely to enroll in services. For example, parents with a specific issue or challenge (e.g., a premature or low birth weight baby) may be more likely to accept services related to parenting. Parents who expect a program to offer resources (e.g., food, help with housing, baby supplies) and instead find themselves with weekly home visits focused on supporting parent–child interactions may not engage fully in these services, or they may be involved at first but then disengage after their initial goal is attained (McAllister and Green 2000), even if the home visitor believes they need support in other areas.

Motivation for home visiting services can be a “moving target,” because parents may not have precisely articulated goals for what they want to achieve from a home visiting program, especially without previous participation in services of this sort. They will not know what their experience will be like until they are in the process of receiving home visits. Like elements of parent involvement discussed above, it is important to recognize the dynamic aspect of a parent’s desire for home visiting services.

This suggests that programs should seriously consider why families enroll in and stay in their services. Why do families seek out home visiting services (a service delivery mechanism that they likely have not previously experienced), and how do their reasons influence their involvement after they are enrolled? This is particularly important for services conducted in the context of a randomized trial, where families agree to participate in services without any guarantee that they will be assigned to the condition that best fits their needs. We also suggest the importance of capturing motivation at different points of time beyond enrollment or baseline. Many programs, including EHS programs, develop family partnership agreements, periodically documenting family needs in order to establish service goals. Assessing parent expectations for services along with these needs, and linking these to on-going involvement, would give a more complete picture of a family’s motivation and progress.

Features of the Program

Beyond home visitor or parent factors, there are program factors that influence involvement. As noted in the Fig. 1, we theorize that program factors influence parent involvement indirectly through the home visitor, as the visitor is ultimately responsible for bringing the program to the family. Home visitors are typically guided by some kind of program model, describing specific information or curricula to be shared with families, structure of home visits, or areas of assessment. These models may be in the form of session-by-session protocols or manuals—such as the Nurse Family Partnership Program—or may work within a framework of a set of principles or performance standards, such as EHS or Healthy Families America.

Both program structure and program content likely affect parent involvement. Program structure refers to details of how a program is supposed to be implemented, such as home visitor caseloads, the prescribed amount of visiting that is expected to happen, and the flexibility allowed for home visitors in establishing contact with families or responding to their needs. For example, families enrolled in Healthy Families America programs participate for a longer duration and have greater contact when their home visitors have smaller caseloads (Daro et al. 2003). Program content refers to what actually is provided during a home visit. Program content influences parent involvement in a program when, for example, families leave a program when it does not match their interests and needs (McAllister and Green 2000). Data from the EHS national evaluation suggested that maintaining a child focus in the content of home visits (an important element of Head Start performance standards) was related to both greater parent engagement during these visits and longer enrollment (Raikes et al. 2006; see also Peterson et al. 2007).

What a home visitor actually talks about and advocates for should, of course, be one of the most central aspects of a family deciding whether or not to stick with the program. Program content, however, has not been a prominent feature of home visiting evaluations. A popular school of thought in early childhood intervention is that the emotional acceptance a home visitor conveys to the family is just as central as the actual content or information conveyed. This orientation, often associated with principles of infant mental health, is summed up by Jeree Pawl’s statement that “how you are is as important as what you do” (Pawl and St. John 1998). Although Pawl has used this statement to draw attention to the importance of the provider’s way of being with families, from an evaluation perspective, both sides of the equation are important. Just as this review has emphasized the need to study how home visitors are with families, we must also focus serious attention on what home visitors do.

Understanding the Relation Between Involvement and Outcome

It is both logically and empirically evident that outcomes are stronger when participants are more involved in an intervention program. Logically, it makes sense that involvement would function as “dosage,” with those who participate more and who are more highly engaged receiving a stronger “dose” of the services offered by a program. There is also empirical evidence supporting this general conclusion. Although there are exceptions (e.g., St. Pierre and Layzer 1999; Duggan et al. 2007), multiple reports have demonstrated that different features of participation (Ramey et al. 1992; Olds et al. 1999; Wagner et al. 2001) or engagement (Heinicke et al. 2000; Lieberman et al. 1991; Korfmacher et al. 1998) or both (Raikes et al. 2006) relate to program outcomes in a variety of home visiting approaches across multiple parent and child outcome domains.Footnote 2

There is a need for caution, however, when making simple interpretations. More involved participants may show more positive outcomes because they were more competent from the beginning. In other words, higher-functioning families may be better able to participate and engage in intervention services, and they may then appear to have stronger outcomes. Another concern is an attribution bias (Littell et al. 2001), in that staff may view higher-functioning families as more involved. In one EHS program, parents with high ratings of parent involvement during their home visits were also rated by staff as improving more during the time they were enrolled in the program (Roggman et al. 2001).

Almost all research that examines the relation between parent involvement and program outcome is correlational, looking within the intervention group. Except for isolated studies (e.g., Powell and Grantham-McGregor 1989), families are not randomized to conditions that vary in their level of expected involvement. This makes it difficult to rule out the influence of level of functioning or other client characteristics when examining the association of involvement and outcome. Although baseline variables are typically entered into analyses as covariates to control for possible bias, this does not eliminate this threat to validity. Randomizing families into different conditions of involvement, however, is a difficult undertaking, especially for programs that pride themselves in being responsive to parent needs.

This suggests that other analytic models need to be considered. One technique to examine this issue in randomized trials is propensity analysis (Rosenbaum and Rubin 1983), matching comparison families on background characteristics to families in the program group with high and low levels of participation. This procedure essentially creates a model to identify families in the comparison group who would have received higher and lower “dosages” of intervention had they actually been assigned to the intervention group. There are a few examples of propensity analysis in early childhood programs, with mixed results. Although researchers with the Infant Health and Development Program reported a positive relation between dosage and child cognitive outcomes using this method (Hill et al. 2003), the EHS Research and Evaluation Project—despite a large sample size and a fairly extensive collection of baseline sociodemographic variables—could not create an appropriate model (Administration for Children and Families 2002).

Summary and Conclusion

This review has highlighted parent involvement in early childhood home visiting services, making a distinction between program participation (quantity) and program engagement (quality), but also suggesting the need to consider these two factors together. We have suggested that there needs to be both an increased empirical and programmatic focus on how involvement is conceptualized and measured, including the study of how it changes over time. Involvement is influenced by features of the parents, of the home visitor, and of the program itself. In turn, there are research findings to suggest its influence on program outcomes, although the evidence is, to date, mostly correlational and suggestive.

It is important to emphasize that a focus on parent involvement should not assign too much influence to either parents or to programs. It may be tempting to assume that parents who do not connect with a no-cost program staffed by dedicated home visitors are resistant, difficult to work with, or too disorganized to make use of a valuable service. Programs need to recognize, however, that the most dedicated families will not be involved in services that are unresponsive to their needs, beliefs, and interests. Parent involvement exists within the alignment of what a program is able to provide and what a parent is able to accept. Others have noted considerable racial and ethnic disparities in social and mental health service delivery, by forces both distal and proximal to the families and programs they serve (e.g., United States Public Health Service 2000). Ultimately parent involvement goes beyond the personal and program level to include cultural and community-based values in recognizing services as helpful and in programs being integrated into the communities they serve (Daro et al. 2003; Green et al. 2004).

There is a strong need to move from the simple question of whether or not home visiting works to more complex questions exploring what occurs inside and around home visiting interventions (Gomby et al. 1999). Understanding parent involvement is central to this exploration. How a program is accepted and used by parents should be examined as carefully as any other factor when evaluating home visiting programs. Such explorations will be beneficial to a field that is feeling its own growing pains as it finds its place within the continuum of services offered across the lifespan. Although the study of parent involvement may not simplify research on home visiting, having a better understanding of why and how families choose to spend their time in home visiting services will guide home visitors to identify strategies that keep parents participating and engaged in services that help them support their young children’s development.

Notes

The term parent is used to represent the primary adult caregiver for the target child, although others besides the parent (such as grandparents) may be in this role (see also the later section on family context).

One prominent meta-analysis of home visiting programs provides mixed support for a link between parent involvement and program outcomes, in that it demonstrated a relation between amount of home visiting and child cognitive outcomes, but no relation between other measures of participation and any other program outcomes (Sweet and Appelbaum 2004).

References

Administration for Children, Families. (1998). Head Start Program performance measures: Second progress report. Washington, DC: DHHS.

Administration for Children, Families. (2002). Making a difference in the lives of children and families: The impacts of Early Head Start Programs on young children and their families. Summary report. Washington, DC: DHHS.

Baker, A. J. L., Piotrkowski, C. S., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (1999). The home instruction program for preschool youngsters (HIPPY). The Future of Children, 9, 116–133. doi:10.2307/1602724.

Barnard, K. E., Magyary, D., Sumner, G., Booth, C. L., Mitchell, S. K., & Spieker, S. (1988). Prevention of parenting alterations for women of low social support. Psychiatry, 51, 248–253.

Belsky, J. (1986). A tale of two variances: Between and within. Child Development, 57, 1301–1305. doi:10.2307/1130453.

Blue-Banning, M., Summers, J. A., Frankland, C., Nelson, L. G., & Beegle, G. (2004). Dimensions of family and professional partnerships: Constructive guidelines for collaboration. Exceptional Children, 70, 167–184.

Bordin, E. S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 16(3), 252–260.

Brookes, S., Summers, J. A., Thornburg, K. R., Ispa, J. M., & Lane, V. J. (2006). Building successful home visitor-mother relationships and reaching program goals in two Early Head Start Programs: A qualitative look at contributing factors. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21, 25–45. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.01.005.

Brooks-Gunn, J. (2003). Do you believe in magic? What we can expect from early childhood intervention programs. SRCD Social Policy Report, 17(1).

Castro, D. C., Bryant, D. M., Peisner-Feinberg, E. S., & Skinner, M. L. (2004). Parent involvement in Head Start Programs: the role of parent, teacher and classroom characteristics. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 19, 413–431. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2004.07.005.

Chaffin, M. (2004). Is it time to rethink healthy start/healthy families? Child Abuse & Neglect, 28, 589–595. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.04.004.

Cole, R., Kitzman, H., Olds, D., & Sidora, K. (1998). Family context as a moderator of program effects in prenatal and early childhood home visitation. Journal of Community Psychology, 26, 37–48. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6629(199801)26:1<37::AID-JCOP4>3.0.CO;2-Z.

Collins, L. M., & Sayer, A. G. (2001). New methods for the analysis of Change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Connell, J. P., & Kubisch, A. C. (1998). Applying a theories of change approach to the design and evaluation of comprehensive community initiatives: Progress, prospects, and problems. Washington, DC: The Aspen Institute.

Daro, D. (2006). Home visitation: Assessing progress, managing expectations. Chicago: Chapin Hall Center for Children. Retrieved November 21, 2006, at http://www.chapinhall.org/article_abstract.aspx?ar=1438&L2=61&L3=129.

Daro, D. A., & Harding, K. A. (1999). Healthy families America: Using research to enhance practice. The Future of Children, 9, 152–176. doi:10.2307/1602726.

Daro, D., McCurdy, K., Falconnier, L., & Stojanovic, D. (2003). Sustaining new parents in home visitation services: key participant and program factors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27, 1101–1125. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.007.

Duggan, A., Caldera, D., Rodriguez, K., Burrell, L., Rohde, C., & Crowne, S. S. (2007). Impact of a statewide home visiting program to prevent child abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 801–827. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.011.

Duggan, A., Fuddy, L., Burrell, L., Higman, S. M., McFarlane, E., Windham, A., et al. (2004). Randomized trial of a statewide home visiting program to prevent child abuse: impact in reducing parental risk factors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28, 623–643.

Duggan, A. K., McFarlan, E. C., Windham, A. M., Rhode, C. A., Salkever, D. S., Fuddy, L., et al. (1999). Evaluation of Hawaii’s Healthy Start Program. The Future of Children, 9, 66–90. doi:10.2307/1602722.

Dunst, C. J., & Paget, K. D. (1991). Parent-professional partnerships and family empowerment. In M. Fine (Ed.), Collaborative involvement with parents of exceptional children (pp. 25–44). BrandonVT: Clinical Psychology Publishing Company, Inc.

Fantuzzo, J., Tighe, E., & Childs, S. (2000). Family involvement questionnaire: A multivariate assessment of family participation in early childhood education. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 367–376. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.92.2.367.

Florian, V., Mikulincer, M., & Bucholtz, I. (1995). Effects of adult attachment style on the perception and search for social support. Journal of Psychology, 129, 665–676.

Fuddy, L. J. (1992). Healthy start data & evaluation: What have we learned along the road to success. Paper presented at the Hawaii Healthy Start Conference, Honolulu, HI.

Gomby, D. (2005). Home visitation in 2005: Outcomes for children and parents. Invest in Kids Working Paper No. 7. Committee for Economic Development: Invest in Kids Working Group. www.ced.org/projects/kids.shtml. Accessed 30 Aug 2006

Gomby, D. S. (2007). The promise and limitations of home visiting: Implementing effective programs. Child Abuse and Neglect, 31, 793–799. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.07.001.

Gomby, D. S., Culross, P. L., & Behrman, R. E. (1999). Home visiting: Recent program evaluations-analysis and recommendations. The Future of Children, 9, 4–26. doi:10.2307/1602719.

Gray, S. W., & Wandersman, L. P. (1980). The methodology of home-based intervention studies: Problems and promising solutions. Child Development, 51, 993–1009. doi:10.2307/1129537.

Green, B. L., Johnson, S. A., & Rodgers, A. (1999). Understanding patterns of service delivery and participation in community-based family support programs. Children’s Services: Social Policy, Research, and Practice, 2, 1–22. doi:10.1207/s15326918cs0201_1.

Green, B. L., McAllister, C. A., & Tarte, J. (2004). The strengths-based practices inventory: A measure of strengths-based practices for social service programs. Families in Society, 85, 326–335.

Greenspan, S., Wieder, S., Lieberman, A. F., Nover, R., Robinson, M., & Lourie, R. (Eds.). (1987). Infants in multirisk families. Madison, CT: International Universities Press.

Guralnick, M. J. (1997). Second-generation research in the field of early intervention. In M. J. Guarlnick (Ed.), The Effectiveness of Early Intervention (pp. 3–20). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Guskin, K. A., & O’Brien, R. A. (2006). Using logic models to strengthen implementation and outcome evaluation: Collaborations among early childhood home visitation programs. Poster presented at the Head Start Eighth National Research Conference. Washington, DC.

Hans, S., & Korfmacher, J. (2002). The professional development of paraprofessionals. Zero To Three, 23(2), 4–8.

Head Start Bureau (2007). Head Start Program fact sheet: Fiscal Year 2007. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/hsb/about/fy2007.html. Accessed 1 Nov 2007.

Hebbeler, K. M., & Gerlach-Downie, S. G. (2002). Inside the black box of home visiting: A qualitative analysis of why intended outcomes were not achieved. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 17, 28–51. doi:10.1016/S0885-2006(02) 00128-X.