Abstract

Despite the evidence and investment in evidence-based federally funded maternal, infant, and early childhood home visiting, substantial challenges persist with parent involvement: enrolling, engaging, and retaining participants. We present an integrative review and synthesis of recent evidence regarding the influence of multi-level factors on parent involvement in evidence-based home visiting programs. We conducted a search for original research studies published from January 2007 to March 2018 using PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, and CINAHL databases. Twenty-two studies met criteria for inclusion. Parent and family characteristics were the most commonly studied influencing factor; however, consistent evidence for its role in involvement was scarce. Attributes of the home visitor and quality of the relationship between home visitor and participant were found to promote parent involvement. Staff turnover was found to be a barrier to parent involvement. A limited number of influencing factors have been adequately investigated, and those that have reveal inconsistent findings regarding factors that promote parent involvement in home visiting. Future research should move beyond the study of parent- and family-level characteristics and focus on program- and home visitor–level characteristics which, although still limited, have demonstrated some consistent association with parent involvement. Neighborhood characteristics have not been well studied and warrant future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) program was authorized by the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act to implement evidence-based home visiting for pregnant women and children up to age 5 living in at-risk communities across the country. Since then, approximately $2 billion has been invested in these programs (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS] 2019). Currently, eighteen evidence-based home visiting models are eligible for MIECHV funding (Sama-Miller et al. 2017) and programs are being implemented across the country. Their goal is to improve maternal and child health, prevent maltreatment, promote school readiness, and strengthen parenting among pregnant women and families with infants and young children (HHS, 2019). This significant and widespread investment in evidence-based home visiting is based on literature supporting their effectiveness in low-income populations. Home visiting has been associated with reductions in maternal smoking (Kramer 1987; Wakschlag et al. 2002), prenatal hypertensive disorders (Olds et al. 1986), and child injuries and maltreatment (Howard and Brooks-Gunn 2009). It has also been linked to increased birth spacing (Olds et al. 1986, 2002) and improved school readiness (Olds et al. 2004). A recent national randomized trial of the four most widely implemented home visiting models found only modest effects on program outcomes (Michalopoulos et al. 2019); however, this same study found that families participated for less time and received fewer visits than the models prescribed.

Community-wide implementation of evidence-based home visiting has faced challenges enrolling, engaging, and retaining participants (Duggan et al. 2018). Estimates suggest that 40% of families invited to enroll do not do so. Of those families who do enroll, 80% receive less than the intended number of visits; up to half of them drop out prior to completion (Sparr et al. 2017). The success of home visitation programs depends, at least in part, on the extent to which parents participate and are engaged in services (Michalopoulos et al. 2019; Raikes et al. 2006a, b). As a result, parent involvement in home visiting programs has been identified as a top priority for home visiting research (Home Visiting Research Network 2013; Wilson et al. 2018) and quality improvement (Mackrain 2017).

Parent involvement in home visiting has been defined as “the process of the parent connecting with and using the services of a program to the best of the parent’s and the program’s ability” (Korfmacher et al. 2008, p. 171). As this definition suggests, the concept of parent involvement is multi-dimensional and is influenced by multiple factors. In 2001, McCurdy and Daro introduced the Integrated Theory of Parent Involvement, which identifies three dimensions of involvement: intent to enroll, enrollment (i.e., receipt of services), and retention. These dimensions focus on the quantity of contact and are typically operationalized by indicators of the home visiting dose, i.e., amount, frequency, visit length, and duration of family participation. In 2008, Korfmacher and colleagues expanded on this model and described “engagement” as an additional dimension of parent involvement which captures the quality of the home visiting experience (i.e., parent satisfaction) and relationship between family and program staff. Both Korfmacher et al. (2008) and McCurdy and Daro (2001) describe a set of multi-level factors that influence these dimensions of parent involvement, including characteristics of the parent and family, the home visitor, the home visiting program, and neighborhood-level characteristics.

Early research on parent involvement in home visiting has focused largely on understanding the influence of parent and home visitor characteristics; however, findings were mixed. Some studies found that families with higher sociodemographic and psychosocial risk were more likely to enroll or remain in home visiting (Daro et al. 2003; Duggan et al. 2000; McCurdy et al. 2003); other studies found that families at higher sociodemographic and psychosocial risk were less likely to enroll or remain in home visiting (Ammerman et al. 2006; Daro et al. 2003; Josten et al. 2002; McGuigan et al. 2003; Raikes et al. 2006a, b).

Home visitor characteristics such as empathy (Olds and Korfmacher 1998), young age (Daro et al. 2003), and being a parent (McCurdy and Daro 2001) were positively associated with parent involvement in single studies; however, they were not examined across multiple studies. Just one early study examined the role of neighborhood characteristics and found poor community health to be associated with lower levels of involvement (McGuigan et al. 2003). Overall, early research did not provide a shared understanding of parent involvement, meaningful metrics for its estimate, or consistent findings regarding the influencing factors relevant to parent involvement in home visiting. To date, there has not been a review of parent involvement research across evidence-based home visiting programs.

Earlier studies provided an important starting point for understanding parent involvement in home visiting; however, much has changed in the past decade. The most significant changes occurred following the 2010 authorization of MIECHV, which led to wide-scale dissemination of evidence-based home visiting programs. MIECHV regulations changed home visiting practices through stipulations for evidence to inform practice and the use of performance indicators to demonstrate measurable outcomes (Adirim and Supplee 2013; Sama-Miller et al. 2017). Additionally, as described earlier, the conceptualization of parent involvement in home visiting has evolved to include dimensions of quality as well as quantity. These changes may impact parent involvement and the way it is studied. This review is intended to describe what is known about parent involvement in evidence-based home visiting programs over the past decade and to inform the next steps for programs of research to ensure that families who can most benefit will participate.

Given the significant financial investment of public dollars into evidence-based home visiting programs, understanding the factors that contribute to parent involvement is essential. The purpose of this integrative review is to synthesize recent evidence regarding the influence of multi-level factors on parent involvement in evidence-based home visiting programs. Consistent with the frameworks advanced by McCurdy and Daro (2001) and Korfmacher et al. (2008), this review is organized along four dimensions of parent involvement: (a) enrollment (i.e., parent agreeing to or completing an initial home visit), (b) participation (i.e., the quantity of home visiting intervention received by parent based on number, frequency, length, and duration of home visits and the intensity of services, relative to time in program or expected number of visits), (c) retention/attrition (i.e., parent remaining in the program through completion or dropping out prior to program completion, as defined by the program), and (d) engagement (i.e., indicators of the quality of the contact, based on the interaction and relationship between the parent/family and program staff, and the emotional response or feelings of the parent towards the services). It should be noted that these terms are often used interchangeably in the literature. For purposes of this paper, parent involvement is used as an umbrella term referring to one of these four dimensions.

Within each dimension, we review the extent to which the following factors were studied and associated with that dimension of parent involvement: (1) parent/family characteristics (e.g., demographics, socioeconomics (SES), motivation, physical and psychological health of the family), (2) home visitor characteristics (e.g., education and training, personal attributes, quality of relationship with parent/family), (3) program characteristics (e.g., structure, content, staffing, flexibility), and (4) neighborhood characteristics (e.g., social capital, physical resources, social disadvantage). Although evidence-based home visiting models vary in eligibility requirements, service length, home visitor qualifications, and focus, they share the same goals and expectations for meeting MIECHV performance indicators. Therefore, this review synthesizes research findings across the different home visiting models in order to describe what we know about this complex phenomenon and what requires further study.

Method

We selected an integrative review as our approach because it employs a systematic approach to the search for relevant literature, and it allows for the inclusion of articles with diverse methodologies, both experimental and non-experimental (Broome 1993). Additionally, integrative reviews discuss not only research implications but also implications for policy and practice, which is relevant for home visiting (Whittemore and Knafl 2005). With the assistance of a medical library informationist, we used Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms to guide the search, such as “home visit,” “perinatal care,” and “patient participation.” We also searched keyword equivalents to the terms and their synonyms. PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, and CINAHL databases were searched (see Supplemental Fig. 1 for the search strategy used in PubMed). We limited the search to literature published between March 2007 and March 2018. The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) approach were used for generating, systematically reviewing, and analyzing original research on parent involvement in evidence-based maternal, infant, and early childhood home visiting programs.

We used the following inclusion criteria to evaluate articles: (a) original quantitative or qualitative research study, (b) study systematically examined parent involvement in home visiting (as previously defined), (c) sample drew from at least one of the 17 home visiting models that were eligible for federal funding at the time of the search (see Table 1; note, one model has been added since March 2018), (d) study was conducted in the USA, and (e) study was published in an English language peer-reviewed journal. Studies were excluded if parent involvement was used exclusively as an independent variable to predict home visiting program outcomes. The process began with two reviewers who applied the inclusion criteria to each article title and abstract. For those in question, the full-text article was reviewed. A third reviewer made a final determination for any articles that were still in question. Reference lists from selected articles were reviewed to identify additional articles for potential inclusion.

The final sample for this integrative review included a wide variety of research methodologies. Due to this diverse representation of methods, we organized studies broadly according to their use of quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods so the information could be used in the analysis stage. Categories of data were extracted from each study including: design, sample, home visiting model, study purpose, measure of parent involvement, and summary of findings. A table was developed to display the information by category and was iteratively compared and synthesized by study team members.

Results

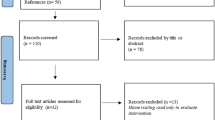

The search resulted in retrieval of 5663 articles. Duplicates were removed leaving 3640 studies that were reviewed for inclusion. The application of inclusion criteria yielded 21 articles; additional four articles meeting inclusion criteria were identified from the reference lists, yielding 25 published studies meeting eligibility criteria (see Fig. 1). Table 2 summarizes the study design, sample, home visiting model, purpose, measure of involvement, and findings from the 25 studies.

Study Design, Sample, and Setting

Fourteen (56%) articles used exclusively quantitative methods (Alonso-Marsden et al. 2013; Cho et al. 2017; Cluxton-Keller et al. 2014; Damashek et al. 2012; Damashek et al. 2011; Daro et al. 2008; Folger et al. 2016; Goyal et al. 2014; Holland et al. 2014b; Ingoldsby et al. 2013; Latimore et al. 2017; Roggman et al. 2016; Roggman et al. 2008; Tandon et al. 2008). Eight (32%) articles used qualitative methods, such as interviews (Beasley et al. 2018; Beasley et al. 2014; Holland, Christensen, Shone, Kearney, and Kitzman, 2014; Hubel et al. 2017; Krysik et al. 2008; Sadler et al. 2018; Shanti 2017; Vaughn et al. 2009) and focus groups (Beasley et al. 2014) with participants and/or home visitors. Three (12%) articles used mixed methods designs (O’Brien et al. 2012; Olds et al. 2015; Rostad et al. 2017). Qualitative sample sizes varied (range 6–49) with three articles including ten or fewer participants (Hubel et al. 2017; Sadler et al. 2018; Vaughn et al. 2009). Quantitative and mixed methods studies used cross-sectional, longitudinal, and experimental and quasi-experimental designs. Sample size ranged from 71 to 10,367 home visiting program participants. Studies drew their samples from six of the 17 eligible evidence-based maternal, infant, and early childhood home visiting models. Seven studies centered on Nurse Family Partnership programs (Beasley et al. 2018; Holland et al. 2014a, b; Ingoldsby et al. 2013; O’Brien et al. 2012; Olds et al. 2015), seven on Healthy Families America (Cluxton-Keller et al. 2014; Daro et al. 2008; Folger et al. 2016; Goyal et al. 2014; Krysik et al. 2008; Tandon et al. 2008; Vaughn et al. 2009), four on Early Head Start (Hubel et al. 2017; Roggman et al. 2008, 2016; Shanti 2017), four on SafeCare® (Beasley et al. 2014; Damashek et al. 2011, 2012; Rostad et al. 2017), one on Family Connects (Alonso-Marsden et al. 2013), and one on Minding the Baby® (Sadler et al. 2018). Two studies drew their samples from both Nurse Family Partnership and Healthy Families America (Cho et al. 2017; Latimore et al. 2017).

Retention/Attrition

Retention/attrition was the most frequently studied dimension of involvement (n = 12; 48%). Studies operationalized retention as either the completion of a specific number of visits or the remaining enrolled in services until a specified age of the child or for a specified length of time.

Parent and Family Characteristics (n = 10 Studies)

Parent’s subjective experience of the program was the only parent/family factor consistently found to be associated with retention. Program satisfaction (Damashek et al. 2011) and the perception that the program helped (Hubel et al. 2017) were reasons for retention, whereas expectation not being met was a reason for attrition (Holland et al. 2014a).

Findings were mixed from studies that examined parent/family demographic and psychosocial characteristics, revealing no consistent demographic predictors of retention or attrition. There were no consistent findings for an association with parent age (Damashek et al. 2011; Folger et al. 2016; O’Brien et al. 2012; Roggman et al. 2008; Rostad et al. 2017), marital status (O’Brien et al. 2012; Roggman et al. 2008; Rostad et al. 2017), living arrangements (O’Brien et al. 2012; Roggman et al. 2008), language and race/ethnicity (Damashek et al. 2011; O’Brien et al. 2012; Roggman et al. 2008), education (Damashek et al. 2011; Roggman et al. 2008; Rostad et al. 2017), employment (O’Brien et al. 2012; Roggman et al. 2008; Rostad et al. 2017), income (Damashek et al. 2011; Rostad et al. 2017), or infant characteristics (O’Brien et al. 2012; Roggman et al. 2008). Findings from studies examining parent psychosocial characteristics, including mental health (Cluxton-Keller et al. 2014; Damashek et al. 2011; Folger et al. 2016; Roggman et al. 2008) and substance use (Damashek et al. 2011; Rostad et al. 2017), were also inconsistent. Only single studies examined the relationships between retention/attrition and parenting stress (Roggman et al. 2008), relationship security (Cluxton-Keller et al. 2014), and intimate partner violence (Damashek et al. 2011). Moving was the only parent/family demographic characteristic found to be associated with attrition but in only two studies (Holland et al. 2014a; Roggman et al. 2008).

The role of family context and needs were examined in several studies of retention. Busy schedules and family life were consistently described as barriers to retention in four qualitative studies (Beasley et al. 2018; Holland et al. 2014a; Hubel et al. 2017; Krysik et al. 2008; Roggman et al. 2008). Parents reported attrition due to a decreased need for support after they felt more comfortable caring for their babies (Krysik et al. 2008) and when they had other adequate support (Holland et al. 2014a). In contrast, one quantitative study found that families’ initial reasons for enrolling were not associated with retention at 6 months (Tandon et al. 2008).

Home Visitor Characteristics (n = 5 Studies)

The nature and quality of the relationship between participant and home visitor were consistently found to be important to retention across four studies: three qualitative (Beasley et al. 2018; Holland et al. 2014a; O’Brien et al. 2012) and one quantitative (Roggman et al. 2008). Four factors were described as contributing to drop out: not knowing how to contact the visitor, reluctance to be open with the home visitor, occasional “lack of fit” between participant and home visitor, participants not having enough control and flexibility over the relationship (Holland et al. 2014a), and not effectively engaging the parent during visits (Roggman et al. 2008). Four factors were cited as facilitating retention: a therapeutic and trusting relationship; characteristics such as being friendly, flexible, supportive, personable, and having experience with children (Beasley et al. 2018); and considering parent unresponsiveness a sign of parent stress rather than as a lack of interest in home visiting was also identified as an important (O’Brien et al. 2012). One study found variability participants description of visitors’ efforts to retain or re-enroll them, either too pushy or not doing enough (Holland et al. 2014a).

Program Characteristics (n = 7)

Home visitor turnover was the only program characteristic consistently found to predict retention/attrition but in just two studies, one qualitative (Holland et al. 2014a) and one quantitative (O’Brien et al. 2012). Other program characteristics, such as type of educational materials (Beasley et al. 2018; Roggman et al. 2008), length of home visits (Roggman et al. 2008), and father engagement (Beasley et al. 2018), were examined in single studies; therefore, conclusions cannot be made. Findings from three intervention studies to improve retention were mixed. An intervention to increased program flexibility demonstrated mixed results for the impact on retention (Ingoldsby et al. 2013; Olds et al. 2015). A single study of a community-based engagement (CBE-HV) intervention was associated with improved retention (Folger et al. 2016).

Participation

Participation was the second most commonly studied dimension of involvement (n = 11, 44.0%). Studies operationalized participation as duration of participation, number of visits, and intensity of visits.

Parent and Family Characteristics (n = 6)

Having a younger child at enrollment (Cho et al. 2017; O’Brien et al. 2012) and a higher infant health risk (Daro et al. 2008; Holland, Xia, et al., 2014) were the only parent/family characteristics consistently found to facilitate participation but in only two studies each. And one multi-level analysis found that differences in family characteristics explained most of the variation in participation in the Nurse Family Partnership but not in Healthy Families America (Latimore et al. 2017). Findings related to other specific parent/family demographic and health characteristics were mixed. Associations were inconsistent between retention/attrition and age (Latimore et al. 2017; O’Brien et al. 2012) (Cho et al. 2017; Holland et al. 2014b), education (Cho et al. 2017; Daro et al. 2008; Holland et al. 2014b), race (Cho et al. 2017; Daro et al. 2008; Holland et al. 2014b; O’Brien et al. 2012), income (Cho et al. 2017; Daro et al. 2008; Holland et al. 2014b), living arrangements (Cho et al. 2017; Holland et al. 2014b; O’Brien et al. 2012), marital status (Holland et al. 2014b), language (Cho et al. 2017), and behavioral health (Holland et al. 2014b; Latimore et al. 2017). Additionally, parent motivation (Beasley et al. 2014), self-identification of need (Daro et al. 2008), schedules/family lives (Beasley et al. 2014), fear (Beasley et al. 2014), needs (O’Brien et al. 2012), and subjective program experience (Daro et al. 2008) were each examined in single studies.

Home Visitor Characteristics (n = 4 Studies)

Across studies, home visitor characteristics were consistently reported as influencing participation; however, the specific qualities varied. Factors positively influencing participation included a home visitor that was supportive, reliable, friendly, non-judgmental, respectful, and flexible (Beasley et al. 2014); had an ability to identify family needs and develop a case plan (Daro et al. 2008); and one that had high job commitment, job satisfaction, and at least a bachelor’s degree (Latimore et al. 2017). Being forceful or pushy was described as a barrier to participation (Beasley et al. 2014). No association was found with parent-home visitor race concordance (Latimore et al. 2017). And one multi-level analysis found that home visitor characteristics explained most of the variation in participation for Healthy Families America but not for Nurse Family Partnership (Latimore et al. 2017).

Program Characteristics (n = 9)

Program content was consistently found to be important to participation across four, primarily qualitative, studies. Positively associated with participation was home visit content that focused on provision of educational materials and community referrals, parenting (Beasley et al. 2014), and child’s developmental milestones (Hubel et al. 2017); provision of free goods (e.g., children’s books or self-care items; Vaughn et al. 2009); as well as programs with more structured processes (Latimore et al. 2017). Barriers to participation included staff turnover (O’Brien et al. 2012), the time-consuming nature of the program (Beasley et al. 2014), and limited opportunities to network with other participants (Vaughn et al. 2009). Three studies tested interventions to improve participation found mixed results. In two studies, participants were given greater flexibility and control over dosage and content of home visits—one study found improved participation (Ingoldsby et al. 2013), whereas the other study found no association (Olds et al. 2015). A third study tested a community-based enrichment intervention that focused on structural changes to the program and found it to be associated with higher levels of participation (Folger et al. 2016).

Neighborhood Characteristics (n = 4 Studies)

Four studies examined associations between participation and neighborhood disadvantage and findings were mixed, showing positive (Daro et al. 2008), negative (Cho et al. 2017), and no associations (Holland et al. 2014b; Latimore et al. 2017). However, all of the studies operationalized neighborhood disadvantage differently, including the following: neighborhood unemployment, race, income, and education (Daro et al. 2008), seven indicators of community economic deprivation and child health risk (Cho et al. 2017), a single measure of neighborhood poverty (Holland et al. 2014b), and the number of SNAP-authorized food stores (Latimore et al. 2017).

Engagement

Engagement in home visiting services was examined in seven studies (28%). Engagement was operationalized as either the quality of relationship with the home visitor or client satisfaction with the program.

Parent and Family Characteristics (n = 2)

Studies of parent/family characteristics and engagement each examined a different dimension of engagement. Individual studies showed that participants with severe depressive symptoms and relationship insecurity gave home visitors lower ratings on trust and quality of the education (Cluxton-Keller et al. 2014), and that participants who were married and those who felt more self-sufficient caring for the baby were less committed to program involvement (Krysik et al. 2008).

Home Visitor Characteristics (n = 3)

All home visitor characteristics were examined in single studies. Higher home visitor cultural competence was associated with greater client satisfaction (Damashek et al. 2012). Participants characterized their relationship with their home visitor as that of a friend with a close emotional bond and valued the home visitor’s personal qualities, such as being nice, caring, someone to count on, a good listener, and a non-judgmental approach (Krysik et al. 2008). One study identified steps for a home visitor to establish a close relationship with parents: (1) form the relationship, learn the culture, build trust and communicate respectfully; (2) program activities, letting parent guide; and (3) maintain active relationship (Shanti 2017).

Program Characteristics (n = 5)

Program characteristics were examined in single studies. Home visitor turnover was found to contribute to difficulties with the home visitor-client relationship (Krysik et al. 2008). Strategies found to support family engagement included a partnership with a diaper bank (Sadler et al. 2018) and home visit time focused on child development (Roggman et al. 2016). Mothers were found to be most satisfied with program efforts to address prenatal health and parenting (Tandon et al. 2008). And one study found non-Caucasian participants who received a more manualized and less flexible program rated home visitor cultural competence as higher (Damashek et al. 2012).

Enrollment

Factors associated with enrollment were the least commonly studied (N = 6, 24.0%). Studies operationalized enrollment as either agreeing to services, scheduling a first visit, completing a first visit, or motivation to enroll.

Parent and Family Characteristics (n = 6 Studies)

Studies revealed no consistent association between parent/family characteristics and enrollment. Findings were mixed in studies that examined demographic risk (Alonso-Marsden et al. 2013; Damashek et al. 2011; Goyal et al. 2014). Single studies looked at maternal depression, substance use, intimate partner violence (Damashek et al. 2011); timing of referral (prenatal versus postpartum) (Goyal et al. 2014); pregnancy complications (Goyal et al. 2014); and poor infant health (Alonso-Marsden et al. 2013), making it difficult to draw conclusions about the relationships.

Parent motivations and concerns about enrollment were explored in three studies; two of the three found that parents’ desire for information and support was a reason for enrollment, including the following: desire for educational and job training, information related to healthy pregnancy and infant care (Tandon et al. 2008), learning parenting skills (Rostad et al. 2017), and getting help for family members related to mental health, intimate partner violence, and substance use (Tandon et al. 2008). In the third qualitative study, most participants expressed an interest and need for services, yet others were skeptical as to whether they needed the program and expressed concerns about being asked sensitive questions (Krysik et al. 2008).

Program Characteristics (n = 1 Study)

In a single study, participants that offered an enhanced home visiting service (tangible goods and financial support, bachelor’s level home visitors, structured skills-based intervention) were more likely to enroll than those offered home visiting as usual (Damashek et al. 2011).

Discussion

The present study synthesized the existing body of research that explores factors influencing parent involvement in evidence-based home visiting. Very few influencing factors have been adequately investigated; therefore, few conclusions can be drawn about what factors promote parent involvement in home visiting. Parent/family characteristics were the most commonly studied influencing factors, but there was little consistent evidence for their role in involvement. Busy schedules and family lives were consistently reported as a barrier to retention, evidence that came primarily from qualitative studies. Home visitor and program characteristics have been studied less often; however, evidence suggests that these factors are important and deserve consideration and focus in future research and in practice and may be more amenable to intervention than parent/family characteristics. For instance, Latimore et al. (2017) found that home visitor characteristics explained most of the variation in participation among Healthy Families America participants.

The attributes of the home visitor and the quality of the relationship between home visitor and participant were consistently found to promote participation, retention, and engagement, evidence that comes primarily from qualitative studies. A strong body of conceptual and empirical literature in home visiting and other helping professions highlights the essential nature of family-centered relationships built on strong communication skills, on shared decision-making, on realistic and strength-focused beliefs and attitudes about families, and on flexibility and responsivity to families’ needs and preferences (Dunst et al. 2002; Korfmacher et al. 2007; West et al. 2018).

Attributes of the program were also found to be associated with involvement. Staff turnover was found to be a barrier to participation, retention, and engagement in several qualitative studies. Home visitor turnover interrupts relationship-based work with families (Gomby 2007) and may lead to higher stress and financial costs for organizations (Maslach and Leiter 1997). A small but growing body of research documents occupational stressors that may lead to turnover in home visiting, such as high levels of paperwork, lack of resources, and dangerous work environments (Alitz et al. 2018; West et al. 2018). To improve staff retention, programs should closely examine how they support home visitors to develop and maintain strong relationships with families and manage occupational stress. Program content and structure were also found to be associated with involvement. In particular, emphasis on child-focused content, provision of tangible goods, structured sessions, and flexibility in visit delivery delivered emerged as influential characteristics. The importance of flexibility in when and how visits are delivered is especially noteworthy; one of the challenges inherent in scaling up evidence-based models concerns how to balance program fidelity with a family-centered approach that takes into account families’ unique needs and preferences.

Research Implications

Future research should move beyond parent factors and shift focus to home visitor, program, and neighborhood factors. More studies are needed that quantitatively test the association between program factors and involvement and that test program-level interventions to enhance involvement. There is promising evidence supporting the effectiveness of interventions that allow for more flexibility in visit timing, frequency, duration, and content interventions; however, it requires further testing due to mixed findings. Conceptually, interventions that allow for greater flexibility make sense. For example, qualitative research has shown that, for some mothers, perceived need for home visiting declines after the immediate postpartum period (Holland et al. 2014a; Krysik et al. 2008). More research is needed to determine “what works for whom” in terms of frequency and duration of visits.

Studies also found that the nature of the helping relationship is important to parent involvement; however, more studies using quantitative methods to examine the relationship would strengthen the finding. A related and highly relevant line of research is testing program- and system-level interventions to strengthen the home visiting workforce, such as training and supervision to support motivational communication skills (Biggs et al. 2018; West et al. 2018) and reflective practice (Gilkerson and Imberger 2016; Watson et al. 2016). More research is needed to demonstrate linkages between these strategies and parent involvement. Supervision and training and on emotional intelligence or mindfulness (Becker et al. 2016) may also be promising strategies for strengthening helping relationships between home visitors and parents.

Few studies have examined the impact of neighborhood characteristics on involvement, despite identification in the Integrated Theory of Parent Involvement as an influencing factor (McCurdy and Daro 2001). Neighborhood disadvantage was the only neighborhood characteristic studied and found to be associated with increased participation. Due to the complexity of relationships, future research should set clear a priori hypotheses for the testing of relationships. For instance, access to concrete resources could increase or decrease retention; access to daycare may allow parents to work and therefore drop out of the program (Daro et al. 2008). In contrast, for families living in food deserts, providing access to healthy foods may increase involvement (Latimore et al. 2017). Relationships between neighborhood characteristics and involvement may also vary depending on population density, concentration of poverty, and region of the country; therefore, researchers should carefully consider their measures of neighborhood characteristics. For instance, all of the studies in this review included objective measures of neighborhoods; however, a parent’s subjective experience of the neighborhood may influence involvement in home visiting differently than objective measures.

There were two primary methodological limitations to this body of research. The first was the populations sampled across studies. None of the studies included families who were offered but opted not to enroll in home visiting. It was possible that parents who did not enroll were different from those who did enroll, even from those who dropped out or had low levels of participation. Future studies should examine reasons why families decline the service when offered. Additionally, studies drew samples from only a third of the evidence-based programs; most samples drew from either the Nurse Family Partnership or Healthy Families America. This limits the ability to generalize findings to other evidence-based home visiting models. The second methodological limitation was the measurement and operationalization of parent involvement. Researchers were inconsistent in how they measured the dimensions of parent involvement, making it difficult to compare findings across studies. The field would benefit from the development of an agreed-upon framework and indicators of involvement so that future research could use standardized terms and measures. Additionally, few studies considered the dimensions of enrollment and engagement and none included indicators of all four dimensions of parent involvement. Expanding the conceptualization of participation to be multi-dimensional and allow for exploration of how dimensions are interrelated would enhance precision in understanding of the complex relationships between the various factors and dimensions (Holland et al. 2018).

There are several important limitations to note in this integrative review. First, we did not use “retention” as a MESH search term due to its widespread use in the medical literature for conditions such as “urinary retention” and the large number of irrelevant articles it would have yielded. As a result, we could have missed articles examining participant retention in evidence-based home visiting programs. However, we did search the reference list of all articles identified in the search, which likely helped to ensure that we did not miss relevant articles. Another limitation was that we restricted the review to articles addressing parent involvement in one of the 17 evidence-based home visiting models that were eligible for MIECHV funding at the time of the search. There is likely more to be learned from the parent involvement literature examining other home visiting models and other types of early childhood services. Finally, as previously noted, we synthesized results across home visiting models despite the fact that there are likely model-specific differences in the factors that influence parent involvement that may have been missed by this review. For instance, Latimore et al. (2017) sampled from both Healthy Families America and Nurse Family Partnership and conducted the same analysis among participants from each program separately. While the authors found several family, home visitor, program, and neighborhood characteristics to be associated with participation, the characteristics associated with parent involvement were different across the two programs.

Conclusions

Understanding parent involvement will help guide the improvement of home visiting programs, contextualize our understanding of program outcomes, and enhance our understanding of “the meaning the families place in these” (Korfmacher et al. 2008, p. 175). However, there is a great deal of complexity to understanding how each of influencing factor and characteristic is associated with each dimension of involvement. While the conclusions that can be drawn from the existing research are limited, the findings do suggest that future home visiting research and practice should focus on meeting individual needs of families instead of using a one-size-fits-all approach to improving parent involvement. This aligns with the national movement towards precision home visiting (Wilson et al. 2018), which asserts that programs should “seek to determine the elements of home visiting that work best for particular types of families in particular contexts” (Wilson et al. 2018). Thus, research should aim to identify the combination of program, home visitor, neighborhood, social, and community factors that work best to involve particular types of families in particular contexts.

References

Adirim, T., & Supplee, L. (2013). Overview of the federal home visiting program. Pediatrics, 132(Supplement 2), S59–S64. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-1021C.

Alitz, P. J., Geary, S., Birriel, P. C., Sayi, T., Ramakrishnan, R., Balogun, O., et al. (2018). Work-related stressors among Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) home visitors: A qualitative study. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 22(Supplement 1), 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2536-8.

Alonso-Marsden, S., Dodge, K. A., O’Donnell, K. J., Murphy, R. A., Sato, J. M., & Christopoulos, C. (2013). Family risk as a predictor of initial engagement and follow-through in a universal nurse home visiting program to prevent child maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect, 37(8), 555–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.012.

Ammerman, R. T., Stevens, J., Putnam, F. W., Altaye, M., Hulsmann, J. E., Lehmkuhl, H. D., et al. (2006). Predictors of early engagement in home visitation. Journal of Family Violence, 21(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-005-9009-8.

Beasley, L. O., Ridings, L. E., Smith, T. J., Shields, J. D., Silovsky, J. F., Beasley, W., & Bard, D. (2018). A qualitative evaluation of engagement and attrition in a nurse home visiting program: From the participant and provider perspective. Prevention Science, 19(4), 528–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-017-0846-5.

Beasley, L. O., Silovsky, J. F., Ridings, L. E., Smith, T. J., & Owora, A. (2014). Understanding program engagement and attrition in child abuse prevention. Journal of Family Strengths, 14(1).

Becker, B. D., Patterson, F., Fagan, J. S., & Whitaker, R. C. (2016). Mindfulness among home visitors in Head Start and the quality of their working alliance with parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(6), 1969–1979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0352-y.

Biggs, J., Sprague-Jones, J., Garstka, T., & Richardson, D. (2018). Brief motivational interviewing training for home visitors: Results for caregiver retention and referral engagement. Children and Youth Services Review, 94(May), 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.09.021.

Broome, M. E. (1993). Integrative literature reviews for the development of concepts. In B. L. Rodgers & K. A. Knafl (Eds.), Concept development in nursing (2nd ed., pp. 231–250). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co..

Cho, J., Terris, D. D., Glisson, R. E., Bae, D., & Brown, A. (2017). Beyond family demographics, community risk influences maternal engagement in home visiting. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(11), 3203–3213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0803-8.

Cluxton-Keller, F., Burrell, L., Crowne, S. S., McFarlane, E., Tandon, S. D., Leaf, P. J., & Duggan, A. K. (2014). Maternal relationship insecurity and depressive symptoms as moderators of home visiting impacts on child outcomes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(8), 1430–1443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9799-x.

Damashek, A., Bard, D., & Hecht, D. (2012). Provider cultural competency, client satisfaction, and engagement in home-based programs to treat child abuse and neglect. Child Maltreatment, 17(1), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559511423570.

Damashek, A., Doughty, D., Ware, L., & Silovsky, J. (2011). Predictors of client engagement and attrition in home-based child maltreatment prevention services. Child Maltreatment, 16(1), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559510388507.

Daro, D., McCurdy, K., Falconnier, L., & Stojanovic, D. (2003). Sustaining new parents in home visitation services: Key participant and program factors. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27(10), 1101–1125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.007.

Daro, D., Mccurdy, K., Falconnier, L., Winje, C., Katzev, A., Keim, A., et al. (2008). The role of community in facilitating service utilization. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 34(1–2), 181–204. https://doi.org/10.1300/J005v34n01.

Duggan, A., Portilla, X. A., Filene, J. H., Crowne, S. S., Hill, C. J., Lee, H., & Knox, V. (2018). Implementation of evidence-based early childhood home visiting. New York.

Duggan, A., Windham, A., McFarlane, E., Fuddy, L., Rohde, C., Buchbinder, S., & Sia, C. (2000). Hawaii’s healthy start program of home visiting for at-risk families: Evaluation of family identification, family engagement, and service delivery. Pediatrics, 105(1), 250–259. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.105.1.S2.250.

Dunst, C. J., Hawks, O., & Carolina, N. (2002). Family-centered practices: Birth through high school. The Journal of Special Education, 36(3), 139–147.

Folger, A. T., Brentley, A. L., Goyal, N. K., Hall, E. S., Sa, T., Peugh, J. L., et al. (2016). Evaluation of a community-based approach to strengthen retention in rarly childhood home visiting. Prevention Science, 17(1), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-015-0600-9.

Gilkerson, L., & Imberger, J. (2016). Strengthening reflective capacity in skilled home visitors. Zero to Three, 37(2), 46–53.

Gomby, D. S. (2007). The promise and limitations of home visiting: Implementing effective programs. Child Abuse and Neglect, 31(8), 793–799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.07.001.

Goyal, N. K., Hall, E. S., Jones, D. E., Meinzen-derr, J. K., & Short, J. A. (2014). Association of maternal and community factors with enrollment in home visiting among at-risk, first-time mothers., 104, 144–151. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301488.

Holland, M. L., Christensen, J. J., Shone, L. P., Kearney, M. H., & Kitzman, H. J. (2014a). Women’s reasons for attrition from a nurse home visiting program. JOGNN - Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 43(1), 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/1552-6909.12263.

Holland, M. L., Olds, D. L., Dozier, A. M., & Kitzman, H. J. (2018). Visit attendance patterns in nurse-family partnership community sites. Prevention Science, 19(4), 516–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-017-0829-6.

Holland, M. L., Xia, Y., Kitzman, H. J., Dozier, A. M., & Olds, D. L. (2014b). Patterns of visit attendance in the nurse-family partnership program. American Journal of Public Health, 104(10), e58–e65. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302115.

Home Visiting Research Network. (2013) Home visiting research agenda. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2010.11.028.

Howard, K. S., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2009). The role of home-visiting programs in preventing child abuse and neglect. The Future of Children, 19(2), 119–146.

Hubel, G. S., Schreier, A., Wilcox, B. L., Flood, M. F., & Hansen, D. J. (2017). Increasing participation and improving engagement in home visitation: A qualitative study of early head start parent perspectives. Infants and Young Children, 30(1), 94–107. https://doi.org/10.1097/IYC.0000000000000078.

Ingoldsby, E. M., Baca, P., McClatchey, M. W., Luckey, D. W., Ramsey, M. O., Loch, J. M., et al. (2013). Quasi-experimental pilot study of intervention to increase participant retention and completed home visits in the Nurse-Family Partnership. Prevention Science, 14(6), 525–534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-013-0410-x.

Josten, L. E., Ph, D., Savik, K., Anderson, M. R., Benedetto, L. L., Chabot, C. R., et al. (2002). Dropping out of maternal and child home visits. Public Health Nursing, 19(1), 3–10.

Korfmacher, J., Green, B., Spellmann, M., & Thornburg, K. R. (2007). The helping relationship and program participation in early childhood home visiting. Infant Mental Health Journal, 28(5), 459–480. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.

Korfmacher, J., Green, B., Staerkel, F., Peterson, C., Cook, G., Roggman, L., et al. (2008). Parent involvement in early childhood home visiting. Child & Youth Care Forum, 37(4), 171–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-008-9057-3.

Kramer, M. S. (1987). Determinants of low birth weight: Methodological assessment and meta-analysis. Bull WHO, 65(5), 663–737. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005542.pub2.

Krysik, J., LeCroy, C. W., & Ashford, J. B. (2008). Participants’ perceptions of healthy families: A home visitation program to prevent child abuse and neglect. Children and Youth Services Review, 30(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.06.004.

Latimore, A. D., Burrell, L., Crowne, S., Ojo, K., Cluxton-Keller, F., Gustin, S., et al. (2017). Exploring multilevel factors for family engagement in home visiting across two national models. Prevention Science, 18(5), 577–589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-017-0767-3.

Mackrain, M. (2017). Home visiting collaborative improvement and innovation network. Retrieved from http://hv-coiin.edc.org/sites/hv-coiin.edc.org/files/HVCoIIN Information Resource 2017_0.pdf%0A. Accessed 3 Oct 2019.

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (1997). The truth about burnout: How organizations cause personal stress and what to do about it. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

McCurdy, K., & Daro, D. (2001). Parent involvement in family support programs: An integrated theory. Family Relations, 50(2), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2001.00113.x.

McCurdy, K., Gannon, R. A., & Daro, D. (2003). Participation patterns in home-based family support programs: Ethnic variations. Family Relations, 52(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2003.00003.x.

McGuigan, W. M., Katzev, A. R., & Pratt, C. C. (2003). Multi-level determinants of retention in a home-visiting child abuse prevention program. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27(4), 363–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00024-3.

Michalopoulos, C., Faucetta, K., Hill, C. J., Portilla, X. A., Burrell, L., Lee, H., … Directors, P. (2019). Impacts on family outcomes of evidence-based early childhood home visiting: Results from the mother and infant home visiting program evaluation. Retrieved from www.mdrc.org.

O’Brien, R. A., Moritz, P., Luckey, D. W., McClatchey, M. W., Ingoldsby, E. M., & Olds, D. L. (2012). Mixed methods analysis of participant attrition in the nurse-family partnership. Prevention Science, 13(3), 219–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-012-0287-0.

Olds, D., & Korfmacher, J. (1998). Maternal psychological characteristics as influences on home visitation contact. Journal of Community Psychology, 26(1), 23–36.

Olds, D. L., Baca, P., McClatchey, M., Ingoldsby, E. M., Luckey, D. W., Knudtson, M. D., et al. (2015). Cluster randomized controlled trial of intervention to increase participant retention and completed home visits in the Nurse-Family Partnership. Prevention Science, 16(6), 778–788. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-015-0563-x.

Olds, D. L., Henderson, C. R., Tatelbaum, R., & Chamberlin, R. (1986). Improving the delivery of prenatal care and outcomes of pregnancy: A randomized trial of nurse home visitation. Pediatrics, 77(1), 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.240.

Olds, D. L., Kitzman, H., Hanks, C., Cole, R., Anson, E., Sidora-Arcoleo, K., et al. (2004). Effects of nurse home visiting on maternal and child functioning: Age-9 follow-up of a randomized trial. Pediatrics, 114(6), 1150–1559. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-2111.

Olds, D. L., Robinson, J., O’Brien, R., Luckey, D. W., Pettitt, L. M., Henderson, C. R., et al. (2002). Home visiting by paraprofessionals and by nurses: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 110(3), 486–496. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004703-200302000-00025.

Raikes, H., Green, B. L., Atwater, J., Kisker, E., Constantine, J., & Chazan-Cohen, R. (2006a). Involvement in Early Head Start home visiting services: Demographic predictors and relations to child and parent outcomes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.01.006.

Raikes, H. H., Pan, B. A., Luze, G., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Brooks-Gunn, J., Constantine, J., et al. (2006b). Mother-child bookreading in low-income families: Correlates and outcomes during the first three years of life. Child Development, 77(4), 924–953. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00911.x.

Roggman, L. A., Cook, G. A., Innocenti, M. S., Norman, V. J., Boyce, L. K., & Peterson, C. A. (2016). Home visit quality variations in two early head start programs in relation to parenting and child vocabulary outcomes., 37(3), 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.

Roggman, L. A., Cook, G. A., Peterson, C. A., & Raikes, H. H. (2008). Who drops out of early head start home visiting programs? Early Education and Development, 19(4), 574–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409280701681870.

Rostad, W. L., Self-Brown, S., Boyd, C., Osborne, M., & Patterson, A. (2017). Exploration of factors predictive of at-risk fathers’ participation in a pilot study of an augmented evidence-based parent training program: A mixed methods approach. Children and Youth Services Review, 79(June), 485–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.07.001.

Sadler, L., Condon, E., Deng, S., Ordway, M., Marchesseault, C., Miller, A., et al. (2018). A diaper bank and home visiting partnership: Initial exploration of research and policy questions. Public Health Nursing, 35(2), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3575.Systems.

Sama-Miller, E., Akers, L., Mraz-Esposito, A., Zukiewicz, M., Avellar, S., Paulsell, D., & Del Grosso, P. (2017). Home visiting evidence of effectiveness review: Executive summary. Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2013.12.063.

Shanti, C. (2017). Engaging parents in early head start home-based programs: How do home visitors do this? Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 14(5), 329–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/23761407.2017.1302858.

Sparr, M., Zaid, S., Filene, J., & Denmark, N. (2017). State-led evaluations of family engagement: the maternal, infant, and early childhood home visiting program what is family engagement and what questions are awardees. Washington, DC.

Tandon, S. D., Parillo, K., Mercer, C., Keefer, M., & Duggan, A. K. (2008). Engagement in paraprofessional home visitation. Families’ reasons for enrollment and program tesponse to identified reasons. Women's Health Issues, 18(2), 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2007.10.005.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2019). Home visiting. Retrieved from https://mchb.hrsa.gov/maternal-child-health-initiatives/home-visiting-overview

Vaughn, L. M., Forbes, J. R., & Howell, B. (2009). Enhancing home visitation programs. Infants & Young Children, 22(2), 132–145.

Wakschlag, L. S., Pickett, K. E., Cook, E., Benowitz, N. L., & Leventhal, B. L. (2002). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and severe antisocial behavior in offspring: A review. American Journal of Public Health, 92(6), 966–974. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.92.6.966.

Watson, C., Bailey, A., & Storm, K. (2016). Building capacity in reflective practice: A tiered model of statewide supports for local home-visiting programs. Infant Mental Health Journal, 37(6), 640–652. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.

West, A., Gagliardi, L., Gatewood, A., Higman, S., Daniels, J., O’Neill, K., & Duggan, A. (2018). Randomized trial of a training program to improve home visitor communication around sensitive topics. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 22(1), 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2531-0.

Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.5001/omj.2009.40.

Wilson, A., Kane, M., Supplee, L., Schindler, A., Poes, M., Filene, J., & Zaid, S. (2018). Introduction to precision home visiting.

Acknowledgments

We thank Johns Hopkins University Informationists, Stella Seal, and Rachel Lebo for their systematic search of the literature for this manuscript. We thank Jennifer Kim, MSN, RN, for her assistance reviewing articles for this publication.

Funding

Funding for this project was provided by Grant Number KL2TR001077 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclaimer

The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the Johns Hopkins ICTR, NCATS, or NIH.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approvals

This study is a systematic review of the literature and did not involve human subjects.

Informed Consent

Due to the fact that this study did not involve human subjects, informed consent was not obtained.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 21 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bower, K.M., Nimer, M., West, A.L. et al. Parent Involvement in Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Programs: an Integrative Review. Prev Sci 21, 728–747 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01129-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01129-z