Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the impact of tobacco smoking on specific histological subtypes of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder (TCC).

Methods

Between 2003 and 2009, we conducted a hospital-based case-control study in Italy, enrolling 531 incident TCC cases and 524 cancer-free matched patients. Odds ratios (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated through multiple logistic regression models.

Results

Compared to never smokers, TCC risk was threefold higher in former smokers (95% CI 2.07–4.18) and more than sixfold higher in current smokers (95% CI 4.54–9.85). TCC risk steadily increased with increasing intensity (OR for ≥25 cigarettes/day 8.75; 95% CI 3.40–22.55) and duration of smoking (OR for ≥50 years 5.46; 95% CI 2.60–11.49). No heterogeneity emerged between papillary and non-papillary TCCs for smoking intensity and duration, but the risk for those who had smoked for ≥50 years was twice for non-papillary TCC (OR 10.88) compared with papillary one (OR 4.76). Among current smokers, the risk for a 10-year increase in duration grew across strata of intensity (p-trend = 0.046). Conversely, the risk for a 5-cigarette/day increase in smoking intensity was quite steady across strata of duration (p-trend = 0.18).

Conclusions

Study results suggested that duration of smoking outweighs intensity in determining TCC risk, with limited differences across histological subtypes. Elimination of tobacco smoking may prevent about 65 % of TCCs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bladder cancer is the 4th most frequent cancer diagnosed in European men, accounting for approximately 105,000 new cases each year. This cancer is less frequent in women, with approximately 30,000 new cases each year [1]. Over 90 % of bladder cancers are transitional cell carcinomas (TCCs) [2], and the majority of them show papillary features, especially in the noninvasive types [3].

Tobacco smoking is recognized as a major risk factor for TCC [2, 4, 5], being responsible of about half cases in both men and women [5]. TCC risk is generally threefold to fivefold higher in heavy smokers compared with never smokers, with a clear dose–response relationship for intensity [4]. A plateau in risk at approximately 20 cigarettes/day has also been reported in a pooled analysis of 11 case–control studies conducted in Europe [6]. Smoking duration is also strongly associated with TCC risk [4], with risks more than fivefold higher in long-lasting smokers than in never smokers [4, 7, 8]. Although the majority of the studies focused on smoking intensity, rather than in duration [4], the results of a pooled analysis suggested that smoking duration is the over-riding factor in determining the risk of bladder cancer [6].

Tobacco smoking has been consistently associated to TCC invasiveness and grading [9–12]. These tumor characteristics strongly correlate with the papillary feature, which is crucial in the TNM classification to classify noninvasive TCCs into Ta or Tis. No previous studies investigated the impact of tobacco smoking on different TCC histological subtypes. Therefore, we analyzed the association between smoking habits and TCC risk using data from an Italian case–control study, focusing on papillary and non-papillary subtypes.

Materials and methods

Between 2003 and 2009, we conducted a case–control study on TCC within an established network of collaborating centers, including Aviano and Milan in northern Italy, and Naples and Catania in southern Italy [13]. Cases were 531 consecutive patients, aged 25–80 years (median age: 67 years), with incident TCC admitted to major general hospitals in the study areas. Nearly all TCCs (n = 528, 99.4 %) were confirmed by histological testing on tumor tissue specimen from biopsy or surgery: 391 (74.0 %) of them showing papillary features (Table 1). Three additional TCCs were confirmed by cytology only, thus excluded from the analyses by histological subtypes. Overall, 232 TCCs (43.7 %) were noninvasive (i.e., TNM pTis/Ta), and 261 (49.2 %) were well or moderately differentiated (Table 1).

The control group included 537 persons frequency-matched to cases by study center, sex, and 5-year age groups. Thirteen controls were excluded after enrollment because not fulfilling study criteria, thus leaving 524 eligible controls (median age: 65 years; range 26–83 years). They were patients admitted to the same network of hospitals of cases for a wide spectrum of acute, non-neoplastic conditions unrelated to tobacco and alcohol consumption, to known risk factors for bladder cancer, or to conditions associated with long-term diet modification. Overall, 31.5 % of controls were admitted for traumatic disorders, 26.7 % for non-traumatic orthopedic disorders, 29.8 % for acute surgical conditions, and 12.0 % for miscellaneous other illnesses. All study subjects signed an informed consent, according to the recommendations of the Board of Ethics of the study hospitals.

Trained interviewers administered a structured questionnaire to both cases and controls during their hospital stay, thus keeping the refusal rate below 5 %. The questionnaire collected information on socio-demographic factors, lifestyle habits, diet in the 2 years before diagnosis/interview, anthropometric measures 1 year prior to diagnosis/interview and at 30 and 50 years of age, problem-oriented medical history, and family history of cancer. Two-specific sections investigated lifetime occupational exposure and exposure to chemicals known (or suspected) to be related to bladder cancer, including the use of hair dyes. Information on smoking included lifetime status (i.e., never, former, or current smoker), daily number of cigarettes/cigars and grams of tobacco pipe smoked, age at starting, duration of the habit, and age at stopping for former smokers. In our computations, 1 g of pipe-smoked tobacco corresponded to one cigarette, and one cigar to three cigarettes. We considered smokers those who had smoked at least one cigarette/day for at least 1 year. Former smokers were defined as smokers who had abstained from cigarette smoking for at least 12 months before interview. The validity and reproducibility of questions on self-reported smoking habits were satisfactory [14].

Odds ratios (ORs) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by means of unconditional logistic regression models, including terms for study center, sex, 5-year age groups, and years of education (i.e., <7, 7–11, ≥12) [15]. ORs for smoking intensity were adjusted for duration, and ORs for duration, age at starting, and time since quitting were adjusted for intensity. Further adjustments for main occupation, body mass index 1 year prior to diagnosis/interview, or alcohol drinking habits did not substantially modify the results. The test for trend was based on the likelihood-ratio test between the models with and without the linear term reporting the median values in each strata of the variable of interest. Percent attributable risks (PAR) were computed using the distribution of risk factors among TCC cases [16].

Results

Cigarette smoking was more frequent among TCC patients (87.4 %) than among controls (64.9 %; Table 2). Compared to never smokers, the risk of TCC was increased by approximately threefolds (95% CI 2.07–4.18) in former smokers and more than sixfolds (95% CI 4.54–9.85) in current smokers. No heterogeneity emerged between men (ORs 2.92 for former smokers and 6.91 for current smokers) and women (ORs 3.73 and 6.19, respectively—data not shown). Compared to controls, TCC cases reported to have smoked more cigarettes/day (median intensity: 20.0 and 16.8 among cases and controls, respectively; p < 0.01) and for longer periods (median duration: 39 and 31 years, respectively; p < 0.01). Conversely, there was no difference in the age at starting smoking (median age: 18 among both cases and controls; p = 0.48).

Among current smokers (Table 2), a steady increase in TCC risk was seen with increasing smoking intensity up to an OR of 8.75 (95% CI 3.40–22.55) for ≥25 cigarettes/day. TCC risk was also positively associated with smoking duration, with OR 5.46 (95% CI 2.60–11.49) for smokers of ≥50 years compared with never smokers. No heterogeneity in risk between papillary and non-papillary TCCs emerged for intensity (p-heterogeneity = 0.77) and duration (p-heterogeneity = 0.40). Nonetheless, the risk for smokers of ≥50 years was doubled for non-papillary TCCs (OR 10.88; 95% CI 3.31–35.79) compared with papillary one (OR 4.76; 95% CI 2.19–10.34). Conversely, age at starting smoking showed an inverse trend in risk for non-papillary TCCs only (p-heterogeneity = 0.06).

Duration of smoking, but not intensity, was significantly associated with TCC risk also in former smokers (Table 3). Time since quitting smoking was inversely associated with TCC risk, with ORs equal to 3.08 (95% CI 1.89–5.03) for those who had stopped smoking <20 years prior to interview and 2.09 (95% CI 1.25–3.51; p = 0.05) for those who had quit for a longer time. No clear differences emerged between the papillary and non-papillary subtypes (p-heterogeneity >0.05 for all exposures). Overall, 65.6 % of TCC cases (95% CI 56.6–74.5 %) were attributable to tobacco smoking, and the fraction was higher for the non-papillary (PAR = 71.4 %) than for the papillary subtype (PAR = 63.6 %).

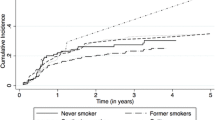

To evaluate the interaction between smoking duration and intensity, we calculated the risk for an increase of 10 years in duration in separate strata of smoking intensity (Fig. 1a). Among current smokers, the risk for duration increased across strata of intensity, from 1.43 (95% CI 1.18–1.75) for <10 cigarettes/day up to 1.64 (95% CI 1.45–1.86) for ≥20 cigarettes/day (p = 0.046). An increase in risk was seen among former smokers, but the trend was less pronounced (p = 0.09). Likewise, we calculated the OR for an increase of 5 cigarettes/day in intensity in separate strata of smoking duration (Fig. 1b). Among current smokers, the risk for intensity increased after 30 years of smoking from 1.30 (95% CI 1.09–1.56) for <30 years up to 1.62 (95% CI 1.34–1.95) for duration 30–39 years, remaining stable thereafter (p = 0.18). A similar trend was observed among former smokers, but ORs were lower in magnitude (p = 0.14).

Odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) for smoking duration in strata of intensity and for intensity in strata of duration. ORs were computed using never smokers as reference, and they were adjusted for sex, age, study center, and years of education. For each category, the OR was plotted at the median point

Finally, we evaluated among current smokers whether intensity and duration of tobacco smoking were associated with tumor characteristics (Supplementary Table 1). On average, smoking for longer periods was significantly associated with cancer invasiveness (mean duration: 40.5 years in stage 0a/0is and 44.1 years in stages I–IV; p = 0.03); similar results also emerged among former smokers (mean duration: 31.0 years and 35.0, respectively; p = 0.01). Likewise, longer smoking duration was associated with poorly differentiated/undifferentiated TCC (p < 0.01). Differences in smoking duration between tumor stages and grading were consistent in 5-year age groups, suggesting that the observed association might not have been confounded by age (data not shown). Conversely, no clear patterns emerged for smoking intensity.

Discussion

The results of the present study confirmed and further quantified the association between tobacco smoking and bladder cancer risk, with approximately two-thirds of TCC cases attributable to this exposure. More interestingly, our study suggested that duration of tobacco smoking is a major determinant of clinical features, with limited differences between papillary and non-papillary subtypes.

In the present study, the association between tobacco smoking and TCC risk was investigated separately for former and current smokers, showing that current smokers had a twofold higher TCC risk than patients who had quit. Although this difference was consistently reported by previous studies [4, 5, 17, 18], few of them investigated intensity and duration separately for former and current smokers [5, 12, 17–20]. Generally, these previous studies showed milder associations between TCC risk and intensity among current smokers than the present study, with risks twofold-to-fivefold higher among smokers of >20 cigarettes/day compared with never smokers. Study populations could, however, have differed in several aspects of smoking habits which may have impacted on TCC risk, including duration of the smoking, age at beginning, tar yield, and use of filters.

In our investigation, age at starting smoking and, possibly, long duration seemed to have had a greater impact among current smokers on the non-papillary TCCs than on the papillary ones. Papillary features have been scarcely investigated in etiological studies on TCC, focusing on other clinical tumor characteristics [10]. A previous study by Jiang and colleagues [11] reported that muscle-invasive bladder cancer had a twofold stronger association than the low-grade superficial one with smoking intensity and duration. Our results are somewhat overlapping considering that 57.2 % of non-papillary TCCs were muscle invasive and 60.0 % of papillary TCCs were low-grade superficial tumors. Similarly, an early SEER study [12] reported a significant association between smoking intensity and cancer invasiveness.

In the present study, TCC risk for duration of smoking increased across strata of intensity, whereas risks for intensity were stable across strata of duration. Consistent with previous studies, these results suggest that duration of smoking had a prominent role compared with intensity in TCC etiology. In previous studies, results on combined exposure to smoking intensity and duration generally showed a marked increase for duration in strata of intensity but not for intensity in strata of duration [6–8, 21, 22], supporting the hypothesis that duration is the predominant risk factor for TCC. More recently, a case–control study in the USA. [8] reported that for an equivalent total exposure (as measured by pack-years), smoking at a lower intensity for a longer period is more harmful than smoking at higher intensity for a shorter period. This effect was seen also for other tobacco-related cancers, including those of lung, oral cavity, and pancreas [23].

These results couple with the well-known model of tobacco-related carcinogenesis in lung cancer [4, 24], which could be applied to other tobacco-related cancers with adaptation in specific details [25]. In this model, the key aspect is the long-lasting exposure of DNA to tobacco carcinogens. These can be metabolized to produce intermediates that react with DNA-forming DNA adducts. Chronic tobacco exposure facilitates the persistence of DNA adducts to reparation by cellular repair enzymes as well as the escape of mutated DNA to removal by apoptosis [25]. In our study, TCC cases smoked, on average, for 37.2 years and longer smoking duration, but not higher intensity, was associated with cancer invasiveness. These results are in accordance with the model proposed by Hecht [24], which hypothesizes that cancer development needs approximately 30 years of chronic exposure to tobacco smoking.

The lack of biological samples to investigate genetic susceptibility is a potential limitation of the present study. Several studies demonstrated that polymorphisms in N-acetyltransferases and in DNA repair genes interact with tobacco smoking on bladder cancer carcinogenesis [26, 27]. Some of these gene polymorphisms have been reported to interact with both smoking intensity and duration [27]. Their effect in tobacco smokers is generally limited in magnitude (<1.5 fold between favorable and unfavorable genotypes) and the frequency of mutated genes is below 15 % [26, 27]. The lack of these data, however, had limited impact on study findings. The results of this study, indeed, were likely average estimates between the effect in smokers with and without the unfavorable genotype. Other potential limitations of this study design comprise recall bias. Although cases may have recalled their smoking habits differently than controls, awareness of any particular smoking and alcohol consumption hypothesis in bladder cancer etiology was limited in the Italian population, at the time of the study. Furthermore, the questionnaire was administered to cases and controls by the same interviewers under similar conditions in a hospital setting, thus minimizing information bias. The possible presence of selection bias may hinder results. However, cases and controls were enrolled from the same hospitals catchment areas, and careful attention was paid to exclude from the control group subjects admitted for any condition related to the exposures under study, including tobacco smoking. On the other hand, our findings were strengthened by the nearly complete participation of identified cases and controls and by the use of a validated questionnaire [14]. Finally a drawback related to the sample size should be stressed as it may have not guaranteed sufficient power for the evaluation of heterogeneity of associations across strata.

The findings from the present study on TCC risk further support the conclusions from previous studies [6, 8, 23], showing that duration of smoking predominates on intensity in determining TCC risk, with limited differences across histological subtypes. These results suggest that the reduction of the amount of cigarettes smoked is not sufficient to prevent cancer onset, but smoking cessation should be the goal of anti-smoking interventions.

References

Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM (2010) GLOBOCAN 2008 v2.0. Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10. International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr, accessed on 13/01/2014

Silverman BT, Devesa SS, Moore LE, Rothman N (2006) Bladder cancer. Cancer epidemiology and prevention, 3rd edn. Oxford Univ Press, New York

Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Sesterhenn IAD (eds) (2004) World health organization classification of tumours. Tumours of the urinary system and genital male organs. IARC Press, Lyon

IARC (2004) IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to Humans, Vol 83. Tobacco smoke and involuntary smoking. IARC Sci Publ. Lyon: IARC

Freedman ND, Silverman DT, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A, Abnet CC (2011) Association between smoking and risk of bladder cancer among men and women. JAMA 306:737–745

Brennan P, Bogilot O, Cordier S et al (2000) Cigarette smoking and bladder cancer in men: a pooled analysis of 11 case–control studies. Int J Cancer 86:289–294

Samanic C, Kogevinas M, Dosemici M et al (2006) Smoking and bladder cancer in Spain: effects of tobacco type, timing, environmental tobacco smoke, and gender. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 15:1348–1354

Baris D, Karagas MR, Verrill C et al (2009) A case–control study of smoking and bladder cancer risk: emergent patterns over time. J Natl Cancer Inst 101:1553–1561

Hinotsu S, Akaza H, Miki T et al (2009) Bladder cancer develops 6 years earlier in current smokers: analysis of bladder cancer registry data by the cancer registration committee of the Japanese urological association. Int J Urol 16:64–69

Pietzak EJ, Malkowicz (2014) Does quantification of smoking history correlate with initial bladder tumor grade and stage? Curr Urol Rep. 15:416. doi: 10.1007/s11934-014-0416-3

Jiang X, Castelao JE, Yuan JM et al (2012) Cigarette smoking and subtype of bladder cancer. Int J Cancer 130:896–901

Sturgeon SR, Hartge P, Silverman DT et al (1994) Association between bladder cancer risk factors and tumor stage and grade at diagnosis. Epidemiology 5:218–225

Polesel J, Gheit T, Talamini R et al (2012) Urinary human polyomavirus and papillomavirus infection and bladder cancer risk. Br J Cancer 106:222–226

D’Avanzo B, La Vecchia C, Katsouyanni K, Negri E, Trichopoulos D (1996) Reliability of information on cigarette smoking and beverage consumption provided by hospital controls. Epidemiology 7:312–315

Breslow NE, Day NE (1980) Statistical methods in cancer research, vol 1. The analysis of case–control studies. IARC Sci Publ No. 32. IARC: Lyon

Benichou J (1991) Methods of adjustment for estimating the attributable risk in case–control studies: a review. Stat Med 10:1753–1773

Bjerregaard BK, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Sørensen M et al (2006) Tobacco smoke and bladder cancer—in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Int J Cancer 119:2412–2416

Augustine A, Hebert JR, Kabat GC, Wynder EL (1988) Bladder cancer in relation to cigarette smoking. Cancer Res 48:4405–4408

Hartge P, Silverman DT, Schairer C, Hoover RN (1993) Smoking and bladder cancer risk in blacks and whites in the United States. Cancer Cause Control 4:391–394

Chiu BCH, Lynch CF, Cerhan JR, Cantor KP (2001) Cigarette smoking and risk of bladder, pancreas, kidney, and colorectal cancer in Iowa. Ann Epidemiol 11:28–37

Castelao JE, Yuan JM, Skipper PL et al (2001) Gender- and smoking-related bladder cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst 93:538–545

Puente D, Hartge P, Greiser E et al (2006) A pooled analysis of bladder cancer case–control studies evaluating smoking in men and women. Cancer Causes Control 17:71–79

Lubin JH, Alavanja MC, Caporaso N et al (2007) Cigarette smoking and cancer risk: modelling total exposure and intensity. Am J Epidemiol 166:479–489

Hecht SS (2002) Cigarette smoking and lung cancer: chemical mechanisms and approaches to prevention. Lancet Oncol 3:461–469

Hecht SS (2003) Tobacco carcinogens, their biomarkers and tobacco-induced cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 3:733–744

Sanderson S, Salanti G, Higgins J (2007) Joint effects of the N-Acetyltransferase 1 and 2 (NAT1 and NAT2) genes and smoking on bladder carcinogenesis. A literature-based systemic huge review and evidence synthesis. Am J Epidemiol 166:741–751

Stern MC, Lin J, Figueroa JD et al (2009) Polymorphisms in DNA repair gene, smoking, and bladder cancer risk: findings from the International Consortium of Bladder Cancer. Cancer Res 69:6857–6864

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Mrs O. Volpato and M. Grimaldi for coordination of data collection and L. Mei for editorial assistance. We are also deeply grateful to Drs G. Chiara (1st General Surgery Dept, General Hospital, Pordenone), G. Tosolini (2nd General Surgery Dept, General Hospital, Pordenone), L. Forner (Eye Diseases Dept, General Hospital, Pordenone), A. Mele (Hand Surgery and Microsurgery Dept, General Hospital, Pordenone), and E. Trevisanutto (Dermatology Dept, General Hospital, Pordenone) for helping in enrollment of subjects. This work was partially supported by the Italian Association for Research on Cancer (AIRC), Grant number 1468. M. Di Maso was supported by a Grant from Fondazione Umberto Veronesi. F. Turati was supported by a fellowship from the Italian Foundation for Cancer Research (FIRC).

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Polesel, J., Bosetti, C., di Maso, M. et al. Duration and intensity of tobacco smoking and the risk of papillary and non-papillary transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Cancer Causes Control 25, 1151–1158 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-014-0416-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-014-0416-0