Abstract

Type 2 diabetes mellitus has been associated with an increased risk of a variety of cancers in observational studies, but few have reported the relationship between diabetes and cancer risk in men and women separately. The main goal of this retrospective cohort study was to evaluate the sex-specific risk of incident overall and site-specific cancer among people with DM compared with those without, who had no reported history of cancer at the start of the follow-up in January 2000. During an average of 8 years of follow-up (SD = 2.5), we documented 1,639 and 7,945 incident cases of cancer among 16,721 people with DM and 83,874 free of DM, respectively. In women, DM was associated with an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.96 (95% CI: 1.53–2.50) and 1.41 (95% CI: 1.20–1.66) for cancers of genital organs and digestive organs, respectively. A significantly reduced HR was observed for skin cancer (0.38; 95% CI: 0.22–0.66). In men with DM, there was no significant increase in overall risk of cancer. DM was related with a 47% reduction in the risk of prostate cancer. These findings suggest that the nature of the association between DM and cancer depends on sex and specific cancer site.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) is a leading cause of death [1], with nearly 200 million annual deaths worldwide [2], mainly due to its association with an increased mortality from cardiovascular diseases [3]. A number of studies have found that DM may alter the risk of a variety of cancers.

Several biological mechanisms have been suggested to explain the potentially causal relationship between DM and cancer. It was suggested [4] that abnormal immunologic, metabolic, and hormonal characteristics of DM may promote cancer development. Studies have also shown that DM patients have greater oxidative damage to DNA as measured by the concentration of 8-hydroxy deoxyguanosine in mononuclear cells [5]. In addition, insulin resistance, compensatory hyperinsulinemia, and elevated levels of bioactive insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) may result in enhanced cell proliferation and promote cancer development [6].

Although the exact biological mechanisms underlying the carcinogenic effects of DM are not fully understood, a specific epidemiological association between DM and pancreatic cancer is well-established [7, 8]. However, it is unclear whether DM is a risk factor for pancreatic cancer or a potential consequence of DM, or both [9–11]. In addition, there are a growing number of studies that suggest that DM patients have higher rates of several other types of cancer. For example, results from a large prospective mortality study in the USA suggest that DM may be an independent risk factor for death from cancers of the colon, liver, and female breast [12]. Smaller cohort and case–control studies also revealed positive associations between DM and cancers other than pancreatic cancer, such as colon cancer [13–17] and primary liver cancer [18–21]. The association of DM with other types of cancer, such as breast [19, 22–25], biliary tract [26], kidney [27–29], and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma [30], has not been fully established.

In women, several studies reported an elevated risk of ovarian cancer [19, 21, 24, 26, 31, 32] and endometrial cancer [33]. In contrast, in men, diabetes was associated with a reduced risk of prostate cancer [34–37]. This has been explained by hormone-related mechanisms including sex steroid hormones, insulin, and insulin-like growth factors. Previous studies reported a difference in the magnitude of cancer risk between men and women, such as liver, colon, and stomach cancer [38–40]. These sex-specific differences in the association between DM and cancer require more careful analyses.

Most previous epidemiologic studies on DM and cancer were limited due to the use of self-reported information about DM status, relatively small study populations, and limited follow-up periods. In addition, many studies examined cancer mortality, but not incidence. Since DM patients with cancer have a poorer survival rate [12, 41], independent of tumor stage and grade, cancer mortality may not represent true risk estimates, particularly for rarer cancers and cancers with low fatality rates.

The main goal of the current retrospective cohort study was to evaluate the risk for incident overall and site-specific cancer among men and women, with and without DM, in a large health maintenance organization (HMO) in Israel using its automated clinical databases.

Methods

Settings

The retrospective cohort study was conducted in Maccabi Healthcare Services (MHS), the second largest HMO in Israel, serving about 25% of the total population (1.8 million members) countrywide. According to the 1995 Israeli National Health Insurance Act, MHS may not bar any citizen who wishes to join it, and therefore every section in the Israeli population is represented in MHS. According to the most recent report of the Israel National Insurance [42], the mean age and proportion of women among MHS members (31.0 years, 48.6%) is similar to the general population (32.4 years, 48.9%); however, due to historical circumstances, MHS have a higher proportion of recent new immigrants (19.8%) and a lower coverage among the non-Jewish population.

Since 1997, information on all members’ interactions (i.e., visits to outpatient clinics, hospitalizations, laboratory tests, and dispensed medications) are downloaded daily to a central computerized database. In addition, MHS has developed and validated computerized registries of patients suffering from major chronic diseases, including ischemic heart disease, hypertension, and DM [43].

Study population

The MHS registry of DM patients has been described in detail elsewhere [44]. Briefly, the registry was constructed in 1999 by an automated search in the MHS computerized databases using the disease criteria suggested by the American Diabetes Association [45]. Since the cohort included prevalent diabetes cases, who were already treated at baseline and have normal glucose concentrations, the MHS DM registry also included all patients who purchased two or more monthly packs of hypoglycemic medications (HG) or insulin during a six-month period, had a history of at least one HgA1c test of ≥7.25%, or a validated physician diagnosis of DM [43]. The registry is continuously validated by computerized feedbacks from practitioners [46].

Using the DM registry, we identified all prevalent DM cases aged 21 or older that were identified prior to index date and were continuously insured by MHS for a period of at least 3 years. The DM-free group was comprised of cancer-free members of the HMO, who had visited their family physicians prior to start of the follow-up but were never diagnosed with DM or laboratory tests suggestive of DM or glucose intolerance. DM-free patients were frequency matched to cases by age (±1 year) and gender in a ratio of 5–1 to insure comparable representation on these two important variables. The follow-up period was from 1 January 2000 (index date) to the date of incident cancer diagnosis, death, discontinuation of coverage by MHS, or 31 August 2008 (whichever occurred first).

Study outcome assessment and ascertainment

Data on cancer occurrence during study follow-up period were obtained from the Israel Cancer Register (ICR). The ICR was established in 1960, and it collects information of diagnosed cancer cases from all medical institutions in the country, covering above 90% of diagnosed cancer cases [47]. All cancer cases were classified according to the International classification of Diseases (ICD-9) and include histological findings. The MHS DM registry and the ICR were cross-linked by the members’ individual unique identifying number.

Other study variables

To allow for the correction for potential confounders, we obtained the following personal data: demographic variables: age, sex, marital status, place of residence, years of stay in Israel, and socioeconomic level defined according to the poverty index based on patient’s residence, according to the latest national census [48]. SES data were unavailable for 14.0% of the DM patients and 14.3% of the DM-free subjects. Severity of diabetes was measured by the median of HgA1C level during the follow-up period, use of hypoglycemic medication or insulin a year prior to index date. Smoking history at index date was available only for 15% of the study population. Earliest measurement of body mass index (BMI) prior to end of follow-up was obtained from medical records and categorized as follows: <25, 25–29.9, 30 kg/m2. The study has been approved by the MHS ethics committee.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using a standard statistical package (SPSS 15.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL). Cancer-free time-interval was calculated from index date until first study outcome using the Kaplan–Meier method. The log-rank test was used to test for differences in cumulative survival to cancer by DM status. Cox regression [49] was used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of overall and site-specific cancer incidence. To examine the potential reverse causality bias, we repeated the analyses limiting it to subjects with at least 5 years of follow-up.

Results

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics for the study population. For both the DM patients and non-DM subjects, the average age at index date was 62 years (SD = ±13 years), and 47% were women. At baseline, DM patients had a significantly higher number of visits to primary care clinics, hospitalizations, and surgical procedures in the year prior to index date. They were more likely to be married and to have lived in Israel for more years than non-DM patients.

During an average of 8 years (SD = 2.5) of follow-up, we documented 1,639 and 7,945 incident cases of cancer among 16,721 DM patients (128,419 Person-Years) and 83,874 DM-free patients (671,086 PY), respectively. The incidence density rates of cancer were, therefore, 13.09 (95% CI: 12.48–13.73) and 11.89 (11.59–12.15) per 1,000 PY in DM patients and DM-free subjects, respectively. In women and men, breast cancer and prostate cancer comprised 26.8% and 26.0% of all cancers, respectively. Cancers of the digestive system organs comprised 23.2% of all cancer in men and 24.6% of all cancer among women. Patients that were diagnosed with metastases or cancer of uncertain type (n = 695) were excluded from further analysis.

A statistically significant increase in the risk of total cancer incidence was observed in women with DM, but not in men (Table 2). In women, DM was associated with an adjusted hazard of 1.52 (95% CI: 1.28–1.80) and 1.96 (95% CI: 1.53–2.50) for cancers of digestive organs and genital organs, respectively. Significantly reduced HRs were calculated for skin cancer (0.38; 95% CI: 0.22–0.66) in women and for prostate cancer (0.53; 95% CI: 0.56–0.74) in men.

A more specific analysis of female genital cancer cases indicate that DM was associated with increased risk of cancer of most relevant organs including uterus and ovaries (Table 3). When cancers of the digestive organs were examined by specific site (Table 4), higher HRs were observed for colon cancer (1.52; 95% CI: 1.19–1.95), pancreas (1.89; 95% CI: 1.16–3.07), and gallbladder (4.05; 95% CI: 1.88–8.69) among women with DM in comparison with non-DM women. None of the HRs for these cancers was elevated among men with DM. To investigate whether the increased risk of colon cancer among patients with DM is confounded by higher rate of screening, we included data regarding colonoscopies performed during a period of 5 years prior to index date in the multivariable model. Although performing colonoscopy was positively associated with higher risk of colon cancer with HR of 1.30 (95% CI: 0.71–2.38) and 1.58 (95% CI: 0.78–3.20) among men and women, respectively, it did not affect the association between DM status and colon cancer.

When analyses were limited to DM patients with at least 5 years of follow-up (13,664 and 71,718 in patients with and without DM, respectively), results were similar to the initial analysis. Among men, the HR for Kaposi’s sarcoma reached 6.44 (95% CI: 1.62–25.61), substantially higher compared with the initial analysis (Table 5).

In women, DM was associated with a significantly elevated adjusted-HR for the following cancers of digestive organs: esophagus (16.70; 95% CI: 2.72–102.68), pancreas (2.05; 95% CI: 0.89–4.74), and gallbladder (8.08; 95% CI: 1.52–43.07). The HR for colon cancer was 1.16 (95% CI: 0.76–1.76). None of these cancers was significantly higher among men with DM. The adjusted HRs for uterine cancer and ovarian cancer associated with DM were 2.61 (95% CI: 1.48–4.60) and 1.83 (95% CI: 0.72–4.63), respectively.

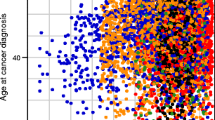

When analyses were stratified by age groups and gender categories, there was no significant (p > 0.1) heterogeneity for any type of cancer. However, the increased HR of digestive organs cancer in DM women has been attenuated with increasing age (Fig. 1).

Discussion

Results of this large, population-based retrospective cohort study suggest that diabetes mellitus in women may be an independent risk factor for cancer of digestive system organs (i.e., pancreas, colon, liver, and gallbladder) and genital organs (i.e., uterus and ovaries). Our findings also indicate that unlike in women, men with diabetes do not have a significantly increased risk to develop digestive system cancers and are also less likely to develop prostate cancer. The findings from the current study suggest that the nature of the association between DM and cancer depends greatly on sex, age, and specific cancer site and should be discussed separately.

A large meta-analysis that included 25 studies published between 1996 and 2005 has found a 33% increase in the risk of colorectal cancers among DM patients [50]. Interestingly, the summary RR from seven studies for colon cancer alone was 1.43, a result which is comparable to our estimates for women. However, most studies described in the above-mentioned meta-analysis did not find a difference in cancer incidence between DM men and women, and only one found a significant increase of cancer in DM women, but not in men [40]. Nilsen and Vattern (2001) suggested that the difference in the magnitude of risk between genders was due to an increased medical surveillance in women [40]. However, in our study, adjustments for history of colonoscopy did not change the risk estimates for colon cancer.

Our findings are in contrast to the Nurses’ Health Study in which women suffering from DM for a long period of time had a reduced risk of colon cancer [51]. This discrepancy can be explained by the fact that in the Nurses’ Health Study the risk attenuation was observed only after 15 years, when pancreatic failure leading to reduced secretion of insulin ensued. The present analysis was limited to a follow-up period of less than 10 years, which was probably insufficient to investigate long-term effects.

A meta-analysis of 17 case–control and 19 cohort or nested case–control studies found that in women DM is associated with a RR of 1.57 for developing pancreatic cancer [52]. This risk estimate is well within the 95% CI calculated in our analysis. However, in men, the significant summary RR reported in the above meta-analysis does not agree with the weak and insignificant association found in our study. When analyses were limited for patients with more than 5 years of follow-up, the association between DM status and pancreatic cancer in women remained high, supporting a causal relationship between diabetes and pancreatic cancer and not the idea of reverse causality.

In agreement with previous studies [51, 53–55], we found that women with DM are at increased risk of colon cancer, but not rectal cancer. Furthermore, in these studies the risk of colon (proximal or distal) cancer and rectal cancer were comparable with our risk estimates. Because tumors in the colon and rectum differ with respect to their risk factors, these findings may hint at potential etiologies. For example, the higher susceptibility of the colon rather than the rectum to the effects of insulin [56] may explain the protective effects of physical activity which reduces insulin levels, against colon cancer but not rectal cancer.

A major limitation of the current study was lack of information on important risk factors for colon cancer such as physical activity or visceral adiposity. However, previous large prospective studies in DM patients that examined the risk of colorectal cancer in men and women separately [38, 57] indicated that these potential confounders had little effect on the calculated risk estimates. BMI during follow-up period was available only for 55% of the DM cases and 66% of the DM-free participants. Our analyses indicated that BMI was negatively associated with cancer of digestive organs. Therefore, since DM patients had higher BMI compared with DM-free subjects, the calculated association between DM and cancer of digestive organs could be underestimated. There was no significant effect on other types of cancer.

A meta-analysis including 19 studies published through 2005 showed that men with diabetes have a ~16% lower risk of developing prostate carcinoma. Sub-analysis of ten studies that controlled for at least three potential confounders yielded an overall HR of 0.73 (95% CI: 0.65–0.85) that is within the 95% CI of our risk estimates. Similar results were found in a recently published population-based cohort study [58]. The biological mechanism by which DM may reduce the risk of prostate cancer is unclear. A hypothetical explanation is that serum levels of insulin correlate negatively with circulating levels of testosterone providing an environment that is protective against proliferation of prostate tumor cells [58]. Others have hypothesized that the negative association between DM and prostate cancer across many populations may relate to a common variant in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 b gene (HNF1b) that was associated with an elevated risk of prostate cancer and a decreased risk of type 2 diabetes [59].

Previously published case series analysis from Israel [60] and a case–control study from Italy [61] suggested that DM was strongly related with Kaposi’s sarcoma in both men and women. However, since DM patients are more likely to have careful and frequent clinical inspection of the lower limbs, where lesions often initiate, the observed association could be the result of detection bias. Nonetheless, in a previous study the increased risk of classical Kaposi sarcoma was calculated also among patients in whom the initial lesion was not detected on legs or feet [61].

The association between DM and gallbladder cancer has be examined in few studies [62–65], yet none of them found a significant association between the two. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to report a strong and statistically significant association between DM and gallbladder cancer in women, but not in men.

We observed no significant association between DM and female breast cancer. A meta-analysis of 26 studies that was published in 2007 found a pooled odds ratio of 1.15 for breast cancer in DM patients (95% CI: 1.12–1.19) [66]. Although similar point estimate (RR = 1.16) was calculated when analyses were limited to cohort studies, the authors reported on considerable heterogeneity in results, where none of seven cohort studies with less than 500 breast cancer cases could demonstrate significant results. Hence, our insignificant results can be explained by insufficient statistical study power due to relatively small increase in risk and lack of information on important confounders such as nutrition and family history.

Several limitations of our analysis must be noted. First, the potential for inaccurate coding and limited clinical information from electronic records that exists for any study using automated database compared to careful chart review [67]. Also, although the present study was one of the largest undertaken to determine the relationship between DM and cancer, it still had a limited statistical power to detect a small increase in risk of rare cancers. Since the exposed study population included prevalent DM cases rather than incident DM cases, we had limited information on patients who died soon after diagnosis with diabetes. This duration ratio bias that can be thought of as a type of differential selection bias could have resulted in underestimation of the true association [68].

The findings of the present study, and particularly, the discrepancy between genders in the risk associated with DM, may help to better understand the underlying pathways for the development of specific tumors. It may also support the development of primary and secondary prevention programs aimed at women with diabetes and increased awareness of DM patients and healthcare personnel to the importance of cancer prevention efforts.

References

Roglic G, Unwin N, Bennett P, Mathers C, Tuomilehto J, Nag S et al (2005) The burden of mortality attributable to diabetes: realistic estimates for the year 2000. Diabetes Care 28:2130–2135

World Health Organization (2008) Diabetes programme. Fact sheet no 312 cited. Available from: http://www.who.int/diabetes/facts/world_figures/en/

Stamler J, Vaccaro O, Neaton J, Wentworth D (1993) Diabetes, other risk factors, and 12 years cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the multiple risk factor intervention trial. Diabetes Care 16:434–444

Adami HO, McLaughlin J, Ekbom A, Berne C, Silverman D, Hacker D et al (1996) Cancer risk in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Natl Cancer Inst 88:307–314

Shin C, Moon B, Park K, Kim S, Park S, Chung M et al (2001) Serum 8-Hydroxy-Guanine levels are increased in diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 24:733–737

Bach L, Rechler M (1992) Insulin-like growth factors and diabetes. Diabetes Metab Rev 8:229–257

Calle EE, Murphy TK, Rodriguez C, Thun MJ, Heath CW Jr (1998) Diabetes mellitus and pancreatic cancer mortality in a prospective cohort of United States adults. Cancer Causes Control 9(4):403–410

Everhart J, Wright D (1995) Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for pancreatic cancer. A meta-analysis. JAMA 273(20):1605–1609

Gapstur S, Gann P, Lowe W, Liu K, Colangelo L, Dyer A (2000) Abnormal glucose metabolism and pancreatic cancer mortality. JAMA 283:2552–2558

Silverman DT, Schiffman M, Everhart J, Goldstein A, Lillemoe KD, Swanson GM et al (1999) Diabetes mellitus, other medical conditions and familial history of cancer as risk factors for pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 80(11):1830–1837

Smith GD, Egger M, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG (1992) Post-challenge glucose concentration, impaired glucose tolerance, diabetes, and cancer mortality in men. Am J Epidemiol 136(9):1110–1114

Coughlin SS, Calle EE, Teras LR, Petrelli J, Thun MJ (2004) Diabetes mellitus as a predictor of cancer mortality in a large cohort of US adults. Am J Epidemiol 159(12):1160–1167

Hardell L, Fredrikson M, Axelson O (1996) Case-control study on colon cancer regarding previous disease and drug intake. Int J Oncol 8:439–444

Kune G, Kune S, Watson L (1988) Colorectal cancer risk, chronic illnesses, operations, and medications: case-control results from the Melbourne colorectal cancer study. Cancer Res 48:4399–4404

La Vecchia C, D’Avanzo B, Negri E, Franceschi S (1991) History of selected diseases and the risk of colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 27:582–586

La Vecchia C, Negri E, Decarli A, Franceschi S (1997) Diabetes mellitus and colorectal cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 6(12):1007–1010

Will JC, Galuska DA, Vinicor F, Calle EE (1998) Colorectal cancer: another complication of diabetes mellitus? Am J Epidemiol 147(9):816–825

Adami HO, Chow WH, Nyren O, Berne C, Linet MS, Ekbom A et al (1996) Excess risk of primary liver cancer in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Natl Cancer Inst 88(20):1472–1477

Adami HO, McLaughlin J, Ekbom A, Berne C, Silverman D, Hacker D et al (1991) Cancer risk in patients with diabetes mellitus. Cancer Causes Control 2(5):307–314

La Vecchia C, Negri E, Decarli A, Franceschi S (1997) Diabetes mellitus and the risk of primary liver cancer. Int J Cancer 73(2):204–207

La Vecchia C, Negri E, Franceschi S, D’Avanzo B, Boyle P (1994) A case-control study of diabetes mellitus and cancer risk. Br J Cancer 70(5):950–953

Goodman M, Cologne J, Moriwaki H, Vaeth M, Mabuchi K (1997) Risk factors for primary breast cancer in Japan: 8 year follow-up of atomic bomb survivors. Prev Med 26:144–153

Moseson M, Koenig K, Shore R, Pasternack B (1993) The influence of medical conditions associated with hormones on the risk of breast cancer. Int J Epidemiol 22:1000–1009

O’Mara BA, Byers T, Schoenfeld E (1985) Diabetes mellitus and cancer risk: a multisite case-control study. Journal of chronic diseases 38(5):435–441

Ragozzino M, Melton L, Chu C, Palumbo P (1982) Subsequent cancer risk in the incidence cohort of Rochester, Minnesota, residents with diabetes mellitus. Journal of chronic diseases 35:13–19

Wideroff L, Gridley G, Mellemkjaer L, Chow WH, Linet M, Keehn S et al (1997) Cancer incidence in a population-based cohort of patients hospitalized with diabetes mellitus in Denmark. J Natl Cancer Inst 89(18):1360–1365

Kreiger N, Marrett L, Dodds L, Hilditch S, Darlington G (1993) Risk factors for renal cell carcinoma: results of a population-based case-control study. Cancer Causes Control 4:101–110

Mellemgaard A, Niwa S, Mehl E, Engholm G, McLaughlin J, Olsen J (1994) Risk factors for renal cell carcinoma in Denmark: role of medication and medical history. Int J Epidemiol 23:923–930

Schlehofer B, Pommer W, Mellemgaard A, Stewart J, McCredie M, Niwa S et al (1996) International renal-cell-cancer study. VI. The role of medical and family history. Int J Cancer 66:723–726

Cerhan J, Wallace R, Folsom A, Potter J, Sellers T, Zheng W et al (1997) Medical history risk factors for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in older women. J Natl Cancer Inst 89:314–318

Shoff SM, Newcomb PA (1998) Diabetes, body size, and risk of endometrial cancer. Am J Epidemiol 148(3):234–240

Weiderpass E, Persson I, Adami HO, Magnusson C, Lindgren A, Baron JA (2000) Body size in different periods of life, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and risk of postmenopausal endometrial cancer (Sweden). Cancer Causes Control 11(2):185–192

Adler AI, Weiss NS, Kamb ML, Lyon JL (1996) Is diabetes mellitus a risk factor for ovarian cancer? A case-control study in Utah and Washington (United States). Cancer Causes Control 7(4):475–478

Adami H, McLaughlin J, Ekbom A, Berne C, Silverman D, Hacker D et al (1991) Cancer risk in patients with diabetes mellitus. Cancer Causes Control 2:307–314

Adler A, Weiss N, Kamb M, Lyon J (1996) Is diabetes mellitus a risk factor for ovarian cancer? A case-control study in Utah and Washington (United States). Cancer Causes Control 7:475–478

Coughlin S, Calle E, Teras L, Petrelli J, Thun M (2004) Diabetes mellitus as a predictor of cancer mortality in a large cohort of US adults. Am J Epidemiol 159:1160–1167

Giovannucci E, Michaud D (2007) The role of obesity and related metabolic disturbances in cancers of the colon, prostate, and pancreas. Gastroenterology 132:2208–2225

Inoue M, Iwasaki M, Otani T, Sasazuki S, Noda M, Tsugane S (2006) Diabetes mellitus and the risk of cancer: results from a large-scale population-based cohort study in Japan. Arch Intern Med 166:1871–1877

Kuriki K, Hirose K, Tajima K (2007) Diabetes and cancer risk for all and specific sites among Japanese men and women. Eur J Cancer Prev 16:83–89

Nilsen T, Vatten L (2001) Prospective study of colorectal cancer risk and physical activity, diabetes, blood glucose and BMI: exploring the hyperinsulinaemia hypothesis. Br J Cancer 84:417–422

Folsom AR, Anderson KE, Sweeney C, Jacobs DR Jr (2004) Diabetes as a risk factor for death following endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 94(3):740–745

Bendelac J (2009) Membership in sick funds 2008. Israel National Insurance Institute, Jerusalem

Chodick G, Heymann A, Shalev V, Kookia E (2003) The epidemiology of diabetes in a large Israeli HMO. Eur J Epidemiol 18:1143–1146

Heymann A, Chodick G, Halkin H, Karasik A, Shalev V, Shemer J et al (2006) The implementation of managed care for diabetes using medical informatics in a large preferred provider organization. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 71:290–298

American Diabetes Association (2002) Management of dyslipidemia in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 25(Suppl. 1):S74–S77

Heymann A, Chodick G, Halkin H, Kokia E, Shalev V (2007) Description of a diabetes disease register extracted from a central database. Harefuah 146:15–79

Israel Center for Disease Control (1999) Health status in Israel 1999. Tel-Hashomer: Israel ministry of health. Report no.: 209

Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (1998) 1995 Census of population and housing Jerusalem

Cox DR (1972) Regression models and life tables (with discussion). J R Stat Soc B 32:187–220

Larsson S, Orsini N, Wolk A (2005) Diabetes mellitus and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 97:1679–1687

Hu F, Manson J, Liu S, Hunter D, Colditz G, Michels K (1999) Prospective study of adult onset diabetes mellitus (type 2) and risk of colorectal cancer in women. J Natl Cancer Inst 91:542–547

Huxley R, Ansary-Moghaddam A, Berrington de González A, Barzi F, Woodward M (2005) Type-II diabetes and pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of 36 studies. Br J Cancer 92:2076–2083

Le Marchand L, Wilkens L, Kolonel L, Hankin J, Lyu L (1997) Associations of sedentary lifestyle, obesity, smoking, alcohol use, and diabetes with the risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 57:4787–4794

Limburg P, Anderson K, Johnson T, Jacobs D Jr, Lazovich D, Hong C (2005) Diabetes mellitus and subsite-specific colorectal cancer risks in the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14:133–137

O’Mara B, Byers T, Schoenfeld E (1985) Diabetes mellitus and cancer risk: a multisite case-control study. J Chronic Dis 38:435–441

Wei E, Ma J, Pollak M, Rifai N, Fuchs C, Hankinson S et al (2005) A prospective study of C-Peptide, insulin-like growth Factor-I, insulin-like growth factor binding Protein-1, and the risk of colorectal cancer in women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14:850–855

Khaw K, Wareham N, Bingham S, Luben R, Welch A, Day N (2004) Preliminary communication: glycated hemoglobin, diabetes, and incident colorectal cancer in men and women: a prospective analysis from the European prospective investigation into cancer-Norfolk study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13:915–919

Kasper J, Liu Y, Giovannucci E (2009) Diabetes mellitus and risk of prostate cancer in the health professionals follow-up study. Int J Cancer 124:1398–1403

Waters K, Henderson B, Stram D, Wan P (2009) LN. K, Haiman C. Association of Diabetes With Prostate Cancer Risk in the Multiethnic Cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 169:937–945

Weissmann A, Linn S, Weltfriend S, Friedman-Birnbaum R (2000) Epidemiological study of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma: a retrospective review of 125 cases from northern Israel. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 14:91–95

Anderson L, Lauria C, Romano N, Brown E, Whitby D, Graubard B et al (2008) Risk factors for classical Kaposi sarcoma in a population-based case-control study in Sicily. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17:3435–3443

Scott T, Carroll M, Cogliano F, Smith B, Lamorte W (1999) A case-control assessment of risk factors for gallbladder carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci 44:1619–1625

Strom B, Soloway R, Rios-Dalenz J, Rodriguez-Martinez H, West S, Kinman J et al (1995) Risk factors for gallbladder cancer. An international collaborative case-control study. Cancer 76:1747–1756

Yagyu K, Lin Y, Obata Y, Kikuchi S, Ishibashi T, Kurosawa M et al (2004) Bowel movement frequency, medical history and the risk of gallbladder cancer death: a cohort study in Japan. Cancer Sci 95:674–678

Zatonski W, Lowenfels A, Boyle P, Maisonneuve P, Bueno de Mesquita H, Ghadirian P et al (1997) Epidemiologic aspects of gallbladder cancer: a case-control study of the SEARCH program of the international agency for research on cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 89:1132–1138

Xue F, Michels K (2007) Diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and breast cancer: a review of the current evidence. Am J Clin Nutr 86:s823–s835

Iezzoni L (1997) Assessing quality using administrative data. Ann Intern Med 127:666–674

Szklo M, Javier Nieto F (2007) Epidemiology: beyond the basics Sudbury, mass. Aspen, Gaithersburg, MD

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Gabriel Chodick had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chodick, G., Heymann, A.D., Rosenmann, L. et al. Diabetes and risk of incident cancer: a large population-based cohort study in Israel. Cancer Causes Control 21, 879–887 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-010-9515-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-010-9515-8