Abstract

Despite the general expectation that ethical leadership fosters employees’ ethical behaviors, surprisingly little empirical effort has been made to verify this expected effect of ethical leadership. To address this research gap, we examine the role of ethical leadership in relation to a direct ethical outcome of employees: moral voice. Focusing on how and when ethical leadership motivates employees to speak up about ethical issues, we propose that moral efficacy serves as a psychological mechanism underlying the relationship, and that leader–follower value congruence serves as a boundary condition for the effect of ethical leadership on moral efficacy. We tested the proposed relationships with matched reports from 154 Korean white-collar employees and their immediate supervisors, collected at two different points in time. The results revealed that ethical leadership was positively related to moral voice, and moral efficacy mediated the relationship. Importantly, as the relationship between ethical leadership and moral efficacy depended on leader–follower value congruence, the mediated relationship was effective only under high leader–follower value congruence. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Following a series of major ethics scandals, not only in business organizations but also in government, non-profit, or even religious organizations, there has been increasing research efforts to understand the role of ethical leadership (Brown and Treviño 2006; Schaubroeck et al. 2012). Ethical leadership is defined as “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making” (Brown et al. 2005, p. 120). Ethical leadership, like other types of leadership (e.g., transformational and authentic leadership), has been related to generally desirable employee attitudes and behaviors, including job satisfaction, organizational commitment, organizational citizenship behavior, and job performance (Brown et al. 2005; Kacmar et al. 2011; Walumbwa et al. 2011).

Despite this progress, however, not much has been known about the effect of ethical leadership on more direct ethical outcomes, such as employee moral behaviors. This is unfortunate because, given its definition, the essence of ethical leadership that distinguishes itself from other types of leadership is in its unique contribution to foster ethical behaviors. Although a few recent studies have provided some evidence that ethical leadership is functional in reducing employees’ unethical behaviors (Mayer et al. 2012; Schaubroeck et al. 2012), ethical behaviors cannot be equated with the reverse of unethical behaviors. Reduced unethical behaviors do not necessarily mean increased ethical behaviors; instead, they can be independent of each other, albeit correlated (Hannah et al. 2011). Therefore, it seems warranted to examine whether ethical leadership is indeed effective in its essential function—promoting employees’ ethical behaviors. By doing so, we would build direct evidence that ethical leadership can be an active enabler of proactive ethical behaviors beyond simply being a suppressor of misconduct.

In an attempt to fill this knowledge gap, we extend the current literature in three ways. First, we examine an explicit ethical behavior of employees—moral voice—as the outcome of ethical leadership. Voice is defined as nonrequired behavior that emphasizes the expression of constructive challenges for improvement rather than mere criticism (Van Dyne and LePine 1998), and moral voice in this study refers to the act of speaking out against unethical issues, in particular. Voice behavior, in general, tends to create tension, discomfort, or damage to one’s public image and relationships with others, potentially putting his or her position in danger (Detert and Burris 2007; Liu et al. 2010; Milliken et al. 2003). For instance, challenging voice likely generates conflict with the status quo and implicit or explicit disagreement and confrontation with others, especially managers. When an employee suggests altering “the way things are” in the organization, the voice may conflict with the viewpoints of managers who are responsible for overseeing or sustaining such practices and routines. As a consequence, the employee can be labeled as a troublemaker or complainer, which may lead to a negative performance evaluation (Milliken et al. 2003; Morrison 2011). Moral voice, in particular, is likely to be accompanied by an even greater deal of personal risk and fear in that such a proactive reaction to injustice in the organization might entail a backlash or even an act of retaliation from the target of moral voice (Morrison 2011). As much as it is sensitive and difficult, moral voice should be given proper attention for the good of the organization because of its potential to keep the organization healthy and sustainable. We thus suggest that moral voice is a unique and important outcome to investigate in relation to ethical leadership.

Second, by considering employee moral efficacy as a cognitive mechanism underlying the relationship between ethical leadership and employee moral voice, we attempt to enrich our understanding of how ethical leadership promotes moral voice. Moral efficacy is defined as “an individual’s belief in his or her capabilities to organize and mobilize the motivation, cognitive resources, means, and courses of action needed to attain moral performance, within a given moral domain” (Hannah et al. 2011, p. 675). Although no study to our knowledge has examined its role in the relationship between ethical leadership and ethical behaviors, moral efficacy is proposed to be a significant psychological determinant regarding the levels of moral motivation and moral action (Hannah et al. 2011). We examine the extent to which ethical leadership works through moral efficacy to influence moral voice. Exploring moral efficacy as a proximal pathway to moral voice also facilitates our effort to identify an important boundary condition of the ethical leadership–moral efficacy–moral voice relationship, which we discuss next.

Third, we further enhance our understanding of the role of ethical leadership in promoting moral efficacy and voice by probing the moderating effect of leader–follower value congruence. The term leader–follower value congruence is defined in this study as the perceived similarity between values held by a leader and a follower (Brown and Treviño 2009; Edwards and Cable 2009). Although ethical leadership may generally have a positive impact on followers’ moral efficacy and moral voice, the extent to which ethical leadership ultimately results in positive outcomes may depend on followers’ value-laden points-of-view regarding their leader’s behaviors. Therefore, we propose that leader–follower value congruence will act as a boundary condition of the predicted relationship between ethical leadership and moral efficacy, and thus moral voice.

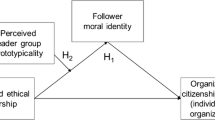

In summary, the purpose of this study is threefold to investigate (1) the ethical leadership–employee moral voice relationship; (2) the mediating role of moral efficacy in such a relationship; and (3) the moderating role of leader–follower value congruence in the ethical leadership–moral efficacy–moral voice relationship. The resulting integrative model of moderated mediation will help advance our knowledge regarding the role of ethical leadership in organizations by shedding light on how and when the ethical leadership effect operates to promote employee moral voice. Figure 1 summarizes the proposed relationships.

Theory and Hypotheses

Ethical Leadership and Moral Voice

According to Treviño and her colleagues (2000), in order to be (or to be perceived as) an ethical leader, one should be both a moral person and a moral manager. A moral person is typified by such characteristics as honesty, integrity, trustworthiness, and fairness. He or she presents concern for others with an open mind, does what is right, and sticks to ethical standards when making decisions. Although Brown, Treviño, and their colleagues (e.g., Brown et al. 2005; Brown and Mitchell 2010; Brown and Treviño 2006) acknowledge that normatively appropriate ethical standards may vary across social settings, they limit the variation to a matter of degree within the range of commonly accepted moral virtues and their behavioral manifestations. In other words, although some of these virtues (e.g., openness and integrity) in certain contexts may not be as important ethical standards as in other contexts, this relative standing does not imply that such virtues and behaviors are unethical in those social settings. Thus, the general content of ethical leadership (e.g., altruistic deeds and honesty) is broadly acknowledged while specific aspects of ethical leadership may be differently emphasized across contexts (Brown and Mitchell 2010). In fact, Resick et al. (2006) found that four aspects of ethical leadership (i.e., integrity, altruism, collective motivation, and encouragement) were commonly endorsed as crucial to ethical leadership across cultures, while the degree of endorsement for each aspect varied across cultures. As an ethical leader, he or she also needs to be a moral manager who uses the tools of his or her position to serve as a model. A moral manager coaches appropriate behaviors in the workplace and rewards and disciplines followers, depending on whether they respect or violate ethical standards. We propose that as leaders engage in ethical leadership, followers are likely to express moral voice.

Voice behavior is “target-sensitive” in general because the consequences of voice may be swayed by the individual to whom employees speak (Detert and Burris 2007; McCall 2001; Van Dyne and LePine 1998); in the case of moral voice particularly involving personal risk and fear, the issue becomes even more sensitive. Also, followers can simply support or echo their leader’s voice against unethical problems in public, a situation that may appear to be less risky on the surface. Even then, however, the moral voice is often directed toward other members or their organization, which may render the followers vulnerable to experiencing interpersonal conflict or disadvantage. Given its nature of entailing personal risk, moral voice shares some common ground with whistle-blowing. Whistle-blowing is defined as the act of disclosing illegal or immoral practices or incidents (Near and MiCeli 1985). Both behaviors are based on a moral motive and potentially lead to personal risk because they challenge the status quo. Recent developments in the voice literature, however, indicate that moral voice can be differentiated from whistle-blowing in an important way (Liang et al. 2012; Morrison, 2011; Van Dyne et al. 1995). While whistle-blowing typically involves an employee’s communication in an anonymous manner to parties outside of organizations, which can put the organization in danger, moral voice concerns open communication directed toward insiders rather than outsiders and is intended to improve one’s organization (Liang et al. 2012).

According to social cognitive theory (Bandura 1986, 1997), credible and attractive leaders may become a target of emulation by creating a fair work environment (Brown et al. 2005; Mayer et al. 2012). Ethical leaders provide the guidelines and support that shape social norms regarding the “right” actions and justice in the given contexts (Brown and Treviño 2006). Followers mimic ethical leaders’ socially justified actions and learn the types of behavior that are expected of them and the norms for behaving through both personal and vicarious experiences (Bandura 1977, 1986; Brown and Treviño 2006). In addition, by virtue of their position, leaders have the power to allocate rewards and punishments. As a result, followers are likely to engage in desired behaviors, as they are aware that their behaviors may be rewarded or disciplined, according to ethical standards. Thus, if, as a legitimate role model, an ethical leader creates a fair environment where ethical standards are clear and ethical behaviors are properly regarded, followers are likely to be inspired to make remarks about ethical issues. Moreover, when ethical leaders display their trustworthiness and impartiality by gathering followers’ opinions and reflecting on their suggestions in decision-making processes, followers are likely to reciprocate with beneficial work behaviors, such as moral voice (Brown and Mitchell 2010; Mayer et al. 2009). For example, without ethical leadership, it may not necessarily be perceived as unethical for followers to turn a blind eye to colleagues’ immoral conduct. When ethical leadership is present, however, it becomes unethical to do so, and thus, followers are more likely to speak out against such immoral deeds.

Although few studies have examined the relationship between ethical leadership and employee moral voice, prior research provides some support for our prediction. For example, it is suggested that if followers have confidence in the ethical nature of their leader, they will be willing to accept the potential risks of reporting problems to management (Brown et al. 2005; Graham 1986; Mayer et al. 1995; Schaubroeck et al. 2012). In a similar vein, Edmonson (2003) found that followers tend to feel less personal risk when engaging in honest communication with a transformational leader who pays attention to and initiates action based on followers’ opinions. Therefore, we propose that employees are likely to voice moral concerns when they perceive their leaders as being ethical.

Hypothesis 1

Ethical leadership is positively related to moral voice.

The Mediating Role of Moral Efficacy

The ethical leadership–moral voice relationship can be explained more fully by examining the mediating role of moral efficacy. That is, to the extent that followers’ perceptions of a leader’s ethicality produce a change in their follower’s moral efficacy, ethical leadership will exert a positive effect on moral voice. Efficacy belief, as a task-specific motivational construct, has been proposed to affect people’s choice of action and the amount and persistence of effort to execute the action (Bandura, 1997; Stajkovic 2006). There exists ample empirical evidence supporting the role of efficacy beliefs across levels of analysis (Gully et al. 2002; Stajkovic et al. 2009; Stajkovic and Luthans 1998). As a kind of efficacy belief specifically related to moral behavior, moral efficacy is expected to influence moral voice because one’s belief that he or she can effectively handle what is necessary to attain moral performance helps him/her to actually express his/her concerns about moral issues (Hannah et al. 2011).

At the same time, moral efficacy can be an important cognitive pathway mediating the effect of ethical leaders’ behaviors on followers’ moral voice. Ethical leaders may promote followers’ moral efficacy by acting as role models who represent integrity, ethical awareness, and a people orientation (Bandura 1986, 1997). As social cognitive theory suggests, once people learn the rules and strategies that their models use, they have the strengthened belief that they can execute those rules and strategies “to generate new instances of behavior that go beyond what they have seen or heard” (Bandura 1997, p. 93). By observing what is ethical from their leaders and by learning how to perform their jobs in ethical ways (Walumbwa et al. 2011), followers realize that they not only need to be sensitive to moral issues at work but also need to speak up when observing practices against established moral standards. Moreover, ethical leaders value the means as well as the outcomes (Walumbwa et al. 2011). Coupled with a genuine interest in followers’ welfare and development, such leadership can lead to a psychologically safe environment, in which a reduced psychological burden of producing maximum outcomes helps followers reserve their cognitive and affective resources to properly deal with moral issues whenever necessary. Too much anxiety and stress concerning only outcomes will likely drain employees’ psychological capacities, and as a consequence, some moral issues may go undetected, or even when detected, may not be critically addressed with timely action. Furthermore, an ethical leader not only asks, “What is the right thing to do?” to followers, but also considers their opinions when making decisions. Such experiences help followers to develop ethical decision-making skills by learning what ethical standards are and how to systematically apply the standards. As a result, this builds up followers’ “potential response repertoires” with such skills (Hannah and Avolio 2010, p. 28). In addition, realizing that their input is heard by their leader and is actually reflected in decisions is likely to serve as a significant persuasive process that increases followers’ moral efficacy (Bandura 1997).

While the ethical leadership–moral efficacy relationship has been subjected to little empirical examination, there is some evidence supporting the relationship. For example, Schaubroeck et al. (2012) found that ethical leadership was indirectly associated with followers’ moral efficacy through shaping ethical culture. In addition, feedback from credible sources (Eden and Aviram 1993) and empowering leadership (Resick et al. 2006), both of which are considered as the characteristics of ethical leaders, have been found to enhance followers’ self-efficacy. Given the above arguments and empirical findings, we expect moral efficacy to operate as a mediator in the relationship between ethical leadership and moral voice.

Hypothesis 2

Moral efficacy mediates the ethical leadership–moral voice relationship.

The Moderating Role of Value Congruence

We further suggest that leader–follower value congruence will act as a boundary condition of the relationship between ethical leadership and moral efficacy. Research suggests that considering personal values will facilitate our understanding of the relationship between leaders and followers (Brown and Treviño 2009). As relatively enduring beliefs that form guiding principles for attitudes, behaviors, and decisions (Rokeach 1968; Suar and Khuntia 2010), personal values have profound implications on individuals’ lives in general. When it comes to leader–follower relationships, value congruence between a follower and a leader becomes immediately salient (Erdogan et al. 2004).

Congruent values between a follower and an ethical leader can facilitate the development of the follower’s moral efficacy through role modeling. Two parties with high value congruence tend to share some aspects of information processing in common, resulting in smoother communication between each other (Meglino and Ravlin 1998). High value congruence between the leader and the follower may imply that the follower’s moral decision criterion is similar to that of the leader. As a result, the follower can promptly adapt to the leader’s ethical behaviors (Ostroff et al. 2005), which in turn helps the follower to develop confident beliefs in moral performance. Also, value congruence functions as a criterion in evaluating the leader’s ethical behavior and in taking actions or reactions after observing the leader’s ethical behavior. With high value congruence, the follower is more likely to pay attention to the leader’s behaviors with a positive point-of-view. Moreover, when two parties’ interests and characteristics are well matched, they tend to be more attracted to, committed to, and attached to each other (Amodio and Showers 2005; Zhang and Bloemer 2011). Thus, when observing the ethical behaviors of leaders whose values are congruent with those of followers, the followers are more likely to believe that they are well aware of the ethical standards and to feel confident regarding their own ethical behaviors.

In contrast, we expect value incongruence to obstruct the follower’s perception of the leader’s ethical behavior from being translated into the follower’s moral efficacy. Leader–follower value incongruence means that there is significant discrepancy in the interests, goals, and guiding principles involving decisions and actions (Brown and Treviño 2009). Value incongruence thus may lead to ethical leadership being considered as simply dogmatic or impractical. Moreover, while followers know what to expect from their leaders when their values are well matched, the increased uncertainty of the work environment due to value incongruence may engender the idea that they cannot manage future events (Jehn et al. 1997; Suar and Khuntia 2010). Such a perception negatively influences followers’ moral efficacy. The above lines of reasoning suggest the following:

Hypothesis 3

Leader–follower value congruence moderates the ethical leadership–moral efficacy relationship, such that a positive relationship is stronger when value congruence is high.

Integrative Model: Moderated Mediation

Considered together with the previous hypotheses, the above-hypothesized pattern of moderation implies moderated mediation, whereby a mediated effect varies as a function of a third variable (Edwards and Lambert 2007). Specifically, when value congruence is high, the desirable effect of ethical leadership on moral efficacy is augmented, thereby strengthening the role of moral efficacy in mediating the relationship between ethical leadership and moral voice. On the contrary, when value congruence is low, the positive effect of ethical leadership on moral efficacy is weakened, thereby neutralizing the mediating effect of moral efficacy. Therefore, we expect value congruence to moderate the indirect effect of ethical leadership on moral voice through moral efficacy. Accordingly, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 4

The strength of the mediated relationship between ethical leadership and moral voice via moral efficacy varies, depending on the extent of leader–follower value congruence: the indirect effect of ethical leadership via moral efficacy on moral voice is stronger when value congruence is high.

Method

Sample and Procedure

The participants of this study were 154 employees and their immediate supervisors from 12 organizations in South Korea. We identified potential study participants through a local human resource forum, comprising corporate human resource directors. We explained the research purpose and data collection procedure, and all 12 directors agreed to participate and provided the email addresses of 240 employees and their direct supervisors. All potential respondents were white-collar employees working in the headquarter sites from diverse functional areas (e.g., human resources, accounting, marketing, and strategic planning).

Data were collected through a time-lagged web-based survey using two different sources. Research suggests that it is difficult to obtain valid, unbiased self-ratings of leadership and moral behaviors (Harris and Schaubroeck 1988). Moreover, given the causal associations assumed in our research model, incorporating sufficient time intervals between measurement of the predictor, moderator and mediator, and criterion variables is essential for stronger causal inferences. Specifically, data on ethical leadership, leader–follower value congruence, and moral efficacy were collected from individual employees in the first survey. 172 employees returned completed surveys, for a response rate of 72 %. One month later, employees’ moral voice behavior was rated by their immediate supervisors. A total of 143 supervisors (matched for 172 employees) were contacted, and 160 ratings from 138 supervisors were obtained. Of those received, 6 ratings from 4 supervisors were unusable because of incomplete responses. This process yielded a final sample consisting of 154 employees with 134 supervisors. Eight of 134 supervisors rated more than one subordinate; the other 126 rated only one subordinate each. No systematic difference in the ratings was found between the eight supervisors who rated multiple subordinates and the other supervisors. Of the sampled subordinates, 44 % were female, and 69 % had a baccalaureate or higher level of education. The average age and organizational tenure of the subordinate participants were 33.53 and 5.65 years, respectively. The average period of the leader–follower relationships was 2.23 years.

Measures

Surveys were translated into Korean, following Brislin’s (1980) translation-back-translation procedure. We measured ethical leadership with Brown et al.’s (2005) ten-item scale. A sample item is “My leader sets an example of how to do things the right way in terms of ethics.” Responses were made on a 1–5 scale (“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) (α = 0.93). Moral voice was measured with three items adopted from the moral courage scale developed by Hannah and Avolio (2010). The supervisors were asked to rate their subordinates’ moral voice on a five-point response scale ranging from 1, “strongly disagree,” to 5, “strongly agree.” The three items are “This person confronts his or her peers when they commit an unethical act,” “This person goes against the group’s decision whenever it violates the ethical standards,” and “This person always states his or her views about ethical issues to me” (α = 0.90). We measured moral efficacy with five items developed by Hannah and Avolio (2010). A sample item is “I am confident that I can determine what needs to be done when I face a moral/ethical decision.” The items used a 1–5 response scale (“not at all confident” to “totally confident”) (α = 0.94). Leader–follower value congruence was measured by adapting the three items of Cable and Derue’s (2002) value congruence scale. A sample item is “My personal values match my supervisor’s values and ideals.” The items used a 1–7 response scale (“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) (α = 0.92).

Although it is not plausible to obtain a bias-free measurement of our study variables, research has provided some evidence that others’ ratings of ethical leadership and voice behavior can be robust to various perceptual errors. For example, Brown et al. (2005) demonstrated that subordinates’ perceptions of ethical leadership were not associated with their age, gender, demographic similarities with the supervisor, social desirability, and cynicism about human nature. They also found substantial within-group agreement in the ratings of ethical leadership among work group members, which would have been unlikely if the ratings had significantly represented a projection of individual subordinates’ implicit leadership theories or response tendencies. As a result, perceptual measures have been widely used in prior studies to examine various forms of leadership and employee behaviors (e.g., Liden et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2012; Mayer et al. 2012; Piccolo and Colquitt 2006; Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009).

In addition, we controlled for employees’ organizational tenure and time with the leader, as well as their age, gender, and education level. As an employee’s tenure increases, he or she may be able to address morally sensitive issues more freely. Given that the leader–follower relationship develops over time, time with the leader might also affect the leader’s rating of the follower’s discretionary behavior (Judge & Ferris, 1993).

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations. As the study participants were from multiple organizations, we assessed whether the responses differ across organizations. The ANOVA resulted in no significant difference in the four main study variables; thus, organizational membership was not included in the subsequent analyses.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on the measures of the study variables to verify their factor structure and construct validity. Specifically, we modeled four correlated factors: correspondence to ethical leadership, leader–follower value congruence, moral efficacy, and moral voice. This theoretical 4-factor model provided a reasonable fit to the data (χ 2 = 435.26, df = 183, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.08). All factor loadings were significant, ranging from 0.74 to 0.83 for ethical leadership, 0.85 to 0.93 for leader–follower value congruence, 0.84 to 0.89 for moral efficacy, and 0.79 to 0.98 for moral voice. Also, a series of Chi square difference tests revealed that the 4-factor model fits the data significantly better than several alternative measurement models (Table 2). In all comparisons, alternative models yielded a significantly poorer fit. Taken together, these results favor the theoretical 4-factor model, thus supporting discriminant validity among the measures.

Hypothesis Tests

We tested Hypotheses 1–3 by performing a series of hierarchical regression analyses. The results appear in Table 3. Supporting Hypothesis 1, followers’ ratings on ethical leadership were positively related to leaders’ reports on the followers’ moral voice behavior (β = 0.24, p < 0.05) after controlling for age, gender, education level, organizational tenure, and time with the leader in Model 5. To test Hypothesis 2 regarding the mediational role of moral efficacy in the ethical leadership–moral voice relationship, we followed the procedure established by Baron and Kenny (1986). First, by testing Hypothesis 1, we already verified the positive effect of ethical leadership on moral voice. Next, in Model 2, ethical leadership evaluated by followers was positively related to their own moral efficacy (β = 0.49, p < 0.01). Finally, in Model 6, moral efficacy was positively related to moral voice (β = 0.20, p < 0.05), explaining significant additional variance in moral voice (ΔR 2 = 0.03, p < 0.05). The effect of ethical leadership on moral voice became weaker but was still significant (β = 0.18, p < 0.05), suggesting partial mediation. To further substantiate this result, we applied Preacher and Hayes’s (2004) test for an indirect effect, which utilizes the bootstrap method for more reliable estimates. The bootstrap results confirmed a significant indirect effect (indirect effect = 0.14, SE = 0.06, 95 % CI [0.04, 0.24]). Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported. Regarding the moderating role of followers’ perceptions of leader–follower value congruence, the interaction term of ethical leadership and value congruence significantly predicted moral efficacy (β = 0.22, p < 0.01; ∆R 2 = 0.09, p < 0.01) in Model 3. To facilitate an interpretation of the interaction pattern, we plotted two simple slopes at one SD above and below the mean value of leader–follower value congruence (Aiken and West 1991). As shown in Fig. 2, the positive relationship between ethical leadership and moral efficacy was stronger when leader–follower value congruence was high (simple slope = 0.60, t = 4.82, p < 0.01) than when it was low (simple slope = 0.18, t = 1.53, ns). This significant interaction effect and the interaction pattern supported Hypothesis 3.

To test Hypothesis 4 regarding integrative moderated mediation, we examined whether the indirect effect of ethical leadership on moral voice via moral efficacy was moderated by leader–follower value congruence (i.e., conditional indirect effect). To test the conditional indirect effect, we utilized Hayes’ (2012) PROCESS program. The indirect effect of ethical leadership on moral voice via moral efficacy was estimated at high (+1 SD) and low levels (−1 SD) of leader–follower value congruence with the bootstrap method. The results indicated that the indirect effect was significant for high value congruence (conditional indirect effect = 0.12, SE = 0.05, 95 % CI [0.04, 0.24]) but was not significant for low value congruence (conditional indirect effect = 0.03, SE = 0.04, 95 % CI [−0.02, 0.15]), thus supporting Hypothesis 4.

Discussion

The present study represents a first time that the role of ethical leadership has been examined in relation to an explicit employee moral behavior, moral voice. We developed and tested a moderated mediation model to simultaneously examine the mediating effect of moral efficacy and the moderating effect of leader–follower value congruence in the relationship between ethical leadership and moral voice.

This study contributes to the existing literature in the following ways. First, this study illuminates the essential role of ethical leadership—promoting followers’ ethical behaviors. While much previous research has treated ethical leadership simply as a means to suppress misconduct or to increase prosocial behaviors, this study empirically demonstrates that ethical leadership is an active civilizing force that encourages employees’ ethical actions, such as moral voice. Unlike the ethical judgment of one’s own behavior, moral voice is a particularly unique and useful outcome variable for research on the role of ethical leadership because moral voice inherently confronts unethical problems, which involves a great deal of potential personal risk. With direct evidence that ethical leadership is indeed effective in motivating employees to express morally courageous opinions, this study enhances our understanding of the essential benefits of the perception of ethical leadership on the leader.

Second, this study extends the research on ethical leadership by adding a substantive mediator to explicate how ethical leaders promote employees’ moral voice. In doing so, this study provides the insight that moral efficacy is a key psychological conduit through which ethical leaders motivate employees to take moral action in spite of fears and concerns about expressing sensitive ethical opinions. In addition, moral efficacy may be a causal mechanism that is relatively general across various types of moral behaviors. By identifying employees’ moral efficacy as a proximal psychological pathway influencing moral action, this study facilitates future research seeking interventions that might prove effective in ultimately promoting ethical behaviors in organizations.

Third, this study suggests that value congruence with leaders is an important moderator of the effect of ethical leadership. By identifying such a boundary condition, this study facilitates a more precise understanding of the role that ethical leadership plays in organizations. Moreover, the finding of the conditional indirect effect of ethical leadership on moral voice via moral efficacy further extends prior piecemeal approaches that investigated either psychological mediators or boundary conditions of the relationship between ethical leadership and ethical performance. As a result, this study captures a more holistic view concerning the roles and functions of ethical leadership in promoting employees’ moral actions.

The contributions of this research should be interpreted in light of its limitations. The first limitation pertains to potential common method variance (i.e., respondents’ perception-based survey method). Although the criterion variable was rated by a different source (i.e., supervisors) at a different point in time, the predictor, mediator, and moderator were assessed by subordinates at the same time. To reduce this potential method bias, we assured anonymity and counterbalanced the item order in developing the questionnaires (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Also, as reported with the CFA result, the measures of the variables were distinguishable from one another among the respondents, implying that the potential effect of common method variance might be minimal. Nevertheless, future research may benefit from an experimental and/or longitudinal research design to minimize potential common method bias. Moreover, to measure our study constructs, this study relied on respondents’ perceptual ratings with Likert-type scales. While these perceptions may not perfectly capture the focal constructs we intended to measure, they are a commonly accepted way of measuring leadership and employee behaviors. Nonetheless, using alternative measurement methods (e.g., behaviorally anchored ratings with frequency scales in assessing ethical leadership and moral voice) might help reduce potential perceptual bias in ratings.

Second, although we found that employees’ fit perceptions of personal values with their supervisors were an important boundary condition of the ethical leadership effect, we did not specifically measure moral value congruence. Overall, personal value congruence may not necessarily entail congruent moral values between two persons. Thus, even when one perceives value congruence with the leader in general, he or she may still find the leader’s moral values in particular to be different from his or hers. Future research should seek a more nuanced understanding of the moderating role of fit perception by directly capturing the specific nature of value congruence.

Third, this study found that ethical leadership had an important and meaningful impact on morally courageous voice behavior. This finding, however, may not attest to the unique effect of ethical leadership beyond the contribution of other related leadership constructs (e.g., transformational leadership and authentic leadership). Also, leaders’ individual characteristics such as agreeableness, conscientiousness, and moral identity have been directly or indirectly related to followers’ behavioral outcomes (e.g., Mayer et al. 2012; Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009). Furthermore, the partial mediation of moral efficacy in the ethical leadership–moral voice relationship suggests the possibility of additional mediating routes through which ethical leadership fosters followers’ moral voice. Considering voice behavior as intentional conduct involving potential tension or damage to one’s public image and relationships with others (Liu et al. 2010), various psychological factors may influence the enactment of such planned behavior (Ajzen 1991). For example, along with moral efficacy (i.e., perceived behavioral control), felt responsibility for fulfilling normatively appropriate ethical codes (i.e., subjective norms) and psychological safety for risky moral voice (i.e., a positive attitude) may also serve as additional mediating mechanisms (Liang et al. 2012). Future research may enhance the internal validity of our findings by including some of these variables, thereby more accurately evaluating the contribution of ethical leadership to employee ethical performance.

This study offers a number of practical implications. First, given the increasing demand for ethical decisions and actions imposed on all levels of organizational members, the present study suggests that ethical leadership can play a pivotal role in motivating employees to engage in moral voice behaviors about ethical issues. Thus, organizations should pay more attention to ways in which levels of ethical leadership among managers can be enhanced in the first place. For example, organizations need to develop selection tools that can assess the ethicality of leaders. After selecting leaders with ethical potential, organizations should provide them with leadership training to further reinforce their ethical skills needed for moral decisions and actions. At the same time, such efforts at the organizational level will be conducive to fostering an ethical culture and ensuring trickle-down effects of ethical leadership across hierarchical levels (Schaubroeck et al. 2012). As a result, employees will be better able to recognize that the organization does value morally courageous behaviors and will reciprocate by following the social norms for appropriate ethical behaviors.

Second, by demonstrating that moral efficacy acts as a vital cognitive mechanism in moral voice, this study is able to pinpoint a more proximal target antecedent of moral behaviors that ethical leadership training can promote. When designing such training programs, primary efforts may concentrate on ways to raise employees’ confidence about ethical behaviors instead of more distal behavioral outcomes for the sake of efficiency. For example, leaders may be trained to enhance moral efficacy through effective social persuasion and enactive or vicarious moral experiences using case studies and scenarios. As a result, better-equipped ethical leaders will become more skillful at instilling a “can do” belief in the morally courageous behaviors of their subordinates.

Third, this study also suggests that ethical leadership becomes more salient and more effective for employees whose values are consistent with those of their leaders. In order to facilitate followers’ moral decisions and actions, organizations need to pay attention not only to leaders’ ethicality but also to value congruence between leaders and followers. It may be a worthwhile effort for a leader to often check the extent to which followers understand and accept his or her values and ideals. No matter how ethical a leader is as a person, it is often possible that followers may not even know their leader’s values. This study therefore suggests that leaders actively share their personal ethical values with their followers. When followers find their leader’s values as acceptable and agree with them, the translation process of ethical leadership into employee moral behaviors will be streamlined and accelerated.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Amodio, D. M., & Showers, C. J. (2005). ‘Similarity breeds liking’ revisited: The moderating role of commitment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22, 817–836.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 389–444). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Brown, M. E., & Mitchell, M. S. (2010). Ethical and unethical leadership. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20, 583–616.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17, 595–616.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2009). Leader–follower values congruence: Are socialized charismatic leaders better able to achieve it? Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 478–490.

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97, 117–134.

Cable, D. M., & DeRue, S. (2002). The construct, convergent, and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 875–884.

Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50, 869–884.

Eden, D., & Aviram, A. (1993). Self-efficacy training to speed reemployment: Helping people to help themselves. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 352–360.

Edmondson, A. C. (2003). Speaking up in the operating room: How team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 1419–1452.

Edwards, J. R., & Cable, D. M. (2009). The value of value congruence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 654–677.

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12, 1–22.

Erdogan, B., Kraimer, M. L., & Liden, R. C. (2004). Work value congruence and intrinsic career success: The compensatory roles of leader-member exchange and perceived organizational support. Personnel Psychology, 57, 305–332.

Graham, J. W. (1986). Principled organizational dissent: A theoretical essay. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 8, pp. 1–52). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Gully, S. M., Incalcaterra, K. A., Joshi, A., & Beaubien, J. M. (2002). A meta-analysis of team-efficacy, potency, and performance: Interdependence and level of analysis as moderators of observed relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 819–832.

Hannah, S. T., & Avolio, B. J. (2010). Moral potency: Building the capacity for character-based leadership. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 62, 291–310.

Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., & May, D. R. (2011). Moral maturation and moral conation: A capacity approach to explaining moral thought and action. Academy of Management Review, 36, 663–685.

Harris, M. M., & Schaubroeck, J. (1988). A meta-analysis of self-supervisor, self-peer, and peer-supervisor ratings. Personnel Psychology, 41, 43–62.

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable moderation, mediation, and conditional process modeling. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com.

Jehn, K. A., Chadwick, C., & Thatcher, S. M. (1997). To agree or not to agree: The effects of value congruence, individual demographic dissimilarity, and conflict on workgroup outcomes. International Journal of Conflict Management, 8, 287–305.

Judge, T. A., & Ferris, G. R. (1993). Social context in performance evaluations. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 80–105.

Kacmar, K. M., Bachrach, D. G., Harris, K. J., & Zivnuska, S. (2011). Fostering good citizenship through ethical leadership: Exploring the moderating role of gender and organizational politics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 633–642.

Liang, J., Farh, C. I. C., & Farh, J. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 71–92.

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Liao, C., & Meuser, J. D. (2014). Servant leadership and serving culture: Influence on individual and unit performance. Academy of Management Journal, 57, 1434–1452.

Liu, D., Liao, H., & Loi, R. (2012). The dark side of leadership: A three-level investigation of the cascading effect of abusive supervision on employee creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 1187–1212.

Liu, W., Zhu, R., & Yang, Y. (2010). I warn you because I like you: Voice behavior, employee identifications, and transformational leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 21, 189–202.

Mayer, D. M., Aquino, K., Greenbaum, R. L., & Kuenzi, M. (2012). Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 151–171.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20, 709–734.

Mayer, D. M., Kuenzi, M., Greenbaum, R., Bardes, M., & Salvador, R. B. (2009). How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108, 1–13.

McCall, J. J. (2001). Employee voice in corporate governance: A defense of strong participation rights. Business Ethics Quarterly, 11, 195–213.

Meglino, B., & Ravlin, E. (1998). Individual values in organizations: Concepts, controversies, and research. Journal of Management, 24, 351–389.

Milliken, F. J., Morrison, E. W., & Hewlin, P. F. (2003). An exploratory study of employee silence: Issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 1453–1476.

Morrison, E. W. (2011). Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 5, 373–412.

Near, J. P., & Miceli, M. P. (1985). Organizational dissidence: The case of whistle-blowing. Journal of Business Ethics, 4, 1–16.

Ostroff, C., Shin, Y., & Kinicki, A. J. (2005). Multiple perspectives of congruence: Relationships between value congruence and employee attitudes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 591–623.

Piccolo, R. F., & Colquitt, J. A. (2006). Transformational leadership and job behaviors: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 327–340.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers, 36, 717–731.

Resick, C. J., Hanges, P. J., Dickson, M. W., & Mitchelson, J. K. (2006). A cross-cultural examination of the endorsement of ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 63, 345–359.

Rokeach, M. (1968). Beliefs, attitudes, and values: A theory of organization and change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Schaubroeck, J. M., Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., Kozlowski, S. W., Lord, R. G., Treviño, L. K., et al. (2012). Embedding ethical leadership within and across organization levels. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 1053–1078.

Stajkovic, A. D. (2006). Development of a core confidence-higher order construct. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1208–1224.

Stajkovic, A. D., Lee, D., & Nyberg, A. J. (2009). Collective efficacy, group potency, and group performance: Meta-analyses of their relationships, and test of a mediation model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 814–828.

Stajkovic, A. D., & Luthans, F. (1998). Self-efficacy and work-related performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 240–261.

Suar, D., & Khuntia, R. (2010). Influence of personal values and value congruence on unethical practices and work behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 97, 443–460.

Treviño, L. K., Hartman, L. P., & Brown, M. (2000). Moral person and moral manager: How executives develop a reputation for ethical leadership. California Management Review, 42, 128–142.

Van Dyne, L., Cummings, L. L., & McLean Parks, J. (1995). Extra-role behaviors: In pursuit of construct and definitional clarity. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 17, pp. 215–285). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Van Dyne, L., & LePine, J. A. (1998). Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Academy of Management Journal, 41, 108–119.

Walumbwa, F. O., Mayer, D. M., Wang, P., Wang, H., Workman, K., & Christensen, A. L. (2011). Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: The roles of leader–member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115, 204–213.

Walumbwa, F. O., & Schaubroeck, J. (2009). Leader personality traits and employee voice behavior: Mediating roles of ethical leadership and work group psychological safety. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 1275–1286.

Zhang, J., & Bloemer, J. (2011). Impact of value congruence on affective commitment: Examining the moderating effects. Journal of Service Management, 22, 160–182.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, D., Choi, Y., Youn, S. et al. Ethical Leadership and Employee Moral Voice: The Mediating Role of Moral Efficacy and the Moderating Role of Leader–Follower Value Congruence. J Bus Ethics 141, 47–57 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2689-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2689-y