Abstract

Scholarly interest in employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior has begun to emerge. While this research is beginning to shed light on the predictors of workplace pro-environmental behavior, our understanding of the psychological mechanisms linking the various antecedents to employees’ environmentally responsible behavior and the circumstances under which any such effects are enhanced and/or attenuated is incomplete. The current study seeks to fill this gap by examining: (a) the effects of perceived corporate social responsibility on employees’ voluntary pro-environment behavior; (b) an underlying mechanism that links CSR perceptions to these behaviors; and (c) a boundary condition to these relationships. Data from 183 supervisor-subordinate dyads employed in large- and medium-sized casinos and hotels in Guangdong China and Macau revealed that employees’ corporate social responsibility perceptions indirectly affect their engagement in voluntary pro-environmental behavior through organizational identification, and these effects are stronger for employees high in empathy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is now considerable agreement that corporations significantly contribute to environmental degradation (Norton et al. 2015; Robertson and Barling 2015). As such, companies around the world are beginning to improve their environmental performance by influencing their employees to engage in voluntary pro-environmental behavior (Robertson and Barling 2015). This interest in workplace pro-environmental behavior has become the focus of scholarly inquiry such that a growing body of research on these behaviors has begun to emerge (Andersson et al. 2013; Norton et al. 2015; Robertson and Barling 2015). Within this literature, research has shown employees’ pro-environmental behavior not only affects the quality of the natural environment, but such behavior also has important implications for organizations (e.g., financial performance), their leaders (e.g., leader effectiveness) and employees (e.g., job satisfaction; see Norton et al. 2015).

Given the beneficial outcomes of workplace pro-environmental behavior, researchers have focused on identifying the predictors of this behavior. Some of this research has linked individual-level person factors to employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior (e.g., subjective norms, positive affect, conscientiousness and motivation; see Bissing-Olson et al. 2013; Flannery and May 2000; Kim et al. 2014; Graves et al. 2013). Other research has explored the influence of organizational factors. For example, perceived organizational support for the environment (e.g., Cantor et al. 2012; Lamm et al. 2015), strategic human resource management practices (e.g., Paillé et al. 2014), perceived management commitment to the environment (e.g., Erdogan et al. 2015; Ramus and Steger 2000), leaders’ supportive behaviors (e.g., Ramus and Steger 2000; Robertson and Barling 2013), environmental infrastructure (e.g., Holland et al. 2006; Van Houten et al. 1981) and incentives (e.g., Graves et al. 2013; Tam and Tam 2008) have been shown to predict workplace pro-environmental behavior. Researchers have also investigated whether or not the perceived presence of an organizational environmental policy affects employees’ engagement in environmentally responsible behavior. For example, Ramus and Steger (2000) reported a direct link, while Norton et al. (2014) and Paillé and Raineri (2015) found an indirect link through employees’ normative beliefs and their commitment to workplace environmental concerns, respectively.

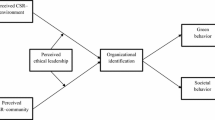

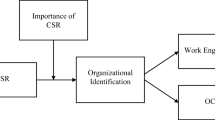

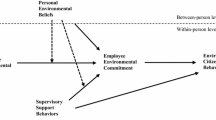

Although this research contributes to our growing understanding of the factors that influence employees to engage in voluntary pro-environmental behavior, research on the predictors of workplace pro-environmental behavior is still in its infancy (Robertson and Barling 2015). As a result, our understanding of the processes and mechanisms through which these antecedents affect employees’ environmentally responsible behavior, and under which conditions any such effects are enhanced and/or attenuated is incomplete (Norton et al. 2015). Further, an examination of the psychological mechanisms underlying the link between the perceived presence of organizational policies implemented at the firm level and workplace pro-environmental behavior has been neglected (Norton et al. 2014), and an understanding of what variables may moderate this relationship is lacking. Finally, there has been little progress in advancing a theoretical understanding of how corporate socially and environmentally responsible practices and policies are associated with employee pro-environmental behavior. Accordingly, we seek to fill these knowledge gaps by exploring how and when perceived corporate social responsibility (CSR)—defined as the perceived presence of socially and environmentally responsible practices and policies that aim to enhance the welfare of various stakeholders (Turker 2009)—affect employees’ propensity to engage in pro-environmental behavior. Specifically, we replicate previous research on the microfoundations of CSR (i.e., the study of how employees respond to perceived CSR; De Roeck et al. 2016) by first hypothesizing that employees’ CSR perceptions predict their organizational identification. We then extend the extant literature by examining: (a) how empathy moderates the effects of perceived CSR on organizational identification; (b) the mediating role of organizational identification to the relationship between perceived CSR and employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior; and (c) the moderating effect of empathy on the indirect effect of perceived CSR on employees’ engagement in environmentally friendly behavior through organizational identification (see Fig. 1). Given that organizations in China are often associated with social negligence and environmental pollution in the eyes of the public (Shen et al. 2008), and there is a need to fill knowledge gaps in the predictors of Chinese employees’ pro-environmental behavior (Chen et al. 2011), we test these hypotheses in the hotel industry in China.

Understanding how and when perceived CSR affects employees’ engagement in pro-environmental behavior is important for several reasons. First, examining the effects of perceived CSR on employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior will contribute to the growing body of literature on the predictors of workplace pro-environmental behavior by identifying another organizational means of enhancing pro-environmental behavior. Although the presence of an organizational environmental policy has been linked to workplace pro-environmental behavior, the role of perceived corporate policies and practices as a key antecedent to employees’ environmentally responsible behavior has not been fully explored (Paillé and Raineri 2015). Second, our examination of organizational identification as the mechanism through which perceived CSR affects workplace pro-environmental behavior provides further insight into how policies and practices implemented at the firm level impact employee behavior—one that highlights the role of employees’ attitudes toward their organization in the enactment of environmentally responsible behavior. Third, by examining the moderating effect of empathy on the relationship between perceived CSR and organizational identification, we identify a potential boundary condition to this relationship, and therefore, provide greater clarity to the “precise nature of this relationship” (De Roeck et al. 2016, p. 2). Finally, should empathy moderate the indirect effect of perceived CSR on workplace pro-environmental behavior through organizational identification, insights into under what circumstances employees are more (less) motivated to engage in pro-environmental behavior will be revealed.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Microfoundations of CSR

CSR is regarded as an important organizational activity (Vlachos, Panagopoulos, and Rapp 2014) that has stimulated a great deal of research. To date, however, the vast majority of this research has focused on the macro-level of analysis (Aguinis and Glavas 2012; Morgeson et al. 2013). For example, macro-level studies have examined CSR’s impact on firm values (e.g., Servaes and Tamayo 2013), reputation (e.g., Brammer and Pavelin 2006), corporate identity (e.g., Lamond et al. 2010), environmental performance (e.g., Stanwick and Stanwick 1998) and financial performance (e.g., Orlitzky et al. 2003). It has only been more recently that studies on the microfoundations of CSR have begun to emerge (Morgeson et al. 2013). Within this literature, studies have shown that perceived CSR can impact employees’ attitudes toward their organization, such as firm attractiveness (e.g., Jones et al. 2014; Rupp et al. 2013), organizational commitment and identification (e.g., Brammer et al. 2007; Carmeli et al. 2007; De Roeck et al. 2016; Kim et al. 2010), and job satisfaction (e.g., Valentine and Fleischman 2008). Research within this realm has also shown that CSR perceptions can affect employees’ in-role and extra-role workplace behaviors, including their job performance (e.g., Korschun et al. 2014; Vlachos et al. 2014), and organizational citizenship behavior (e.g., Farooq et al. 2016; Jones 2010; Rupp et al. 2013).

Recently, Vlachos et al. (2014) extended the notion that employees respond positively to CSR to suggest that perceived CSR influences employees’ engagement in extra-role CSR-specific behavior. Specifically, Vlachos et al. (2014) found that when employees judge their company as socially and environmentally responsible, they are more likely to contribute ideas to, get involved with the implementation of and embrace their organization’s overall CSR program. This research suggests that perceived CSR impacts the extent to which an employee engages in behavior related to their firm’s CSR program. Given that employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior represents a type of extra-role behavior that is related to CSR activity (Boiral 2009), we examine whether, how and when perceived CSR affects employees’ engagement in voluntary pro-environmental behavior. In doing so, we seek to extend Vlachos et al.’s (2014) initial research by demonstrating that the effect of employees’ CSR perceptions extends beyond general CSR-specific behavior, potentially impacting employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior (i.e., a specific type of behavior that supports a firm’s CSR activity).

CSR Perceptions Foster Organizational Identification

Derived from social identity theory (Ashforth and Mael 1989; Tajfel and Turner 1986) and self-categorization theory (Haslam and Ellemers 2005), the concept of organizational identification (i.e., the degree to which a member defines him or herself by the same attributes that he/she believes define the organization; Dutton et al. 1994) is well established within the CSR literature (Korschun et al. 2014). According to this theory, due to the desire to enhance one’s self-concept and self-esteem needs (Farooq et al. 2016), when an organization’s internal (i.e., employees’ own organizational perceptions) and external (i.e., employees’ beliefs of how outsiders view the organization) image enhances self-continuity, self-distinctiveness, and self-enhancement, an employee is more likely to view their organization’s image as attractive, and in turn, identify with that organization (Dutton et al. 1994).

CSR perceptions are regarded as particularly important in influencing how attractive an employee will evaluate his/her organization (Farooq et al. 2016). According to Glavas and Godwin (2013), employees’ CSR perceptions affect the attractiveness of their organization’s internal and external image because it contributes to employees’ self-continuity and distinctiveness and fulfills their self-enhancement needs. In terms of self-continuity, social identity perspective suggests that an employee’s self-concept is reinforced when she/he believes their organization’s values mirror their own (Brammer et al. 2014; Dutton et al. 1994). With respect to self-distinctiveness, socially and environmentally responsible companies are often seen as prestigious (Glavas and Godwin 2013; Jones et al. 2014), and as such, external stakeholders differentiate them from non-socially and environmentally responsible companies (Brammer et al. 2014). Being associated with a company that is viewed as distinct provides employees with a sense of self-uniqueness (Dutton et al. 1994). Finally, working for a prestigious, distinct organization whose values are similar to one’s own fosters feelings of pride or reward (Dutton et al. 1994; Kim et al. 2010), which in turn, enhances self-esteem (Brammer et al. 2014) and self-worth, as employees bask in reflected glory of their organizations (Jones et al. 2014). By influencing employees’ self-continuity, distinctiveness and self-enhancement needs, employees begin to incorporate attributes of the organization into their own identity. Supporting these theoretical arguments, research has shown socially and environmentally responsible companies are more attractive to prospective employees (Jones et al. 2014; Rupp et al. 2013), and employees are more likely to identify with them (e.g., Brammer et al. 2014; De Roeck et al. 2016; Kim et al. 2010). Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1

Perceived CSR is positively related to organizational identification.

The Moderating Role of Empathy

Recently, scholars have begun to investigate the boundary conditions to the relationship between perceived CSR and organizational identification. For example, Farooq et al. (2016) demonstrated that employees’ social and cultural orientations affect the extent to which they identify with their organization as a result of their CSR perceptions. Similarly, De Roeck et al. (2016) found that employees are more likely to identify with their socially and environmentally responsible organizations when they perceive their company as being internally fair. Extending this research, we argue that how strongly employees identify with their organization as a result of their CSR perceptions will be contingent on individual differences in empathy.

EmpathyFootnote 1 is conceptualized as an individual difference that involves sharing of another’s feelings in relation to that other’s well-being (Batson 1990) and consists of both cognitive and emotional components (Duan and Hill 1996; Mencl and May 2009). Cognitive empathy captures an individual’s ability to take the perspective of those in need (Batson and Shaw 1991), while emotional empathy refers to “an other oriented emotional response elicited by and congruent with the perceived welfare of someone in need” (Batson 2008, p. 8). Through these cognitive and emotional components, empathy motivates helping of those in need (Batson 2009), and as a result, has been linked to ethical conduct. For example, within the management literature, empathy has been shown to be related to moral disengagement (Detert et al. 2008), ethical conduct toward customers (Verbeke and Bagozzi 2002) and ethical decision making (Dietz and Kleinlogel 2014; Mencl and May 2009). Thus, given its focus on identifying with others in need (i.e., those who CSR activities seek to help) and its relevance to ethics in organizational settings, we suggest that empathetic employees will be more likely to identify with their organization when they perceive it as socially and environmentally responsible.

Highly empathetic individuals are those who are able to take the perspective of someone in need, and as a result, experience a vicarious response such that they feel affected by what happens to that other person (Batson 1990, 2008). Recently, it has been argued that employees can feel empathy for others in need outside of the organization (Muller et al. 2014). This suggests that employees who are affected by what happens to others outside of the organization will be particularly sensitive to their organization’s CSR activities because CSR focuses on enhancing the welfare of various external stakeholders in need (Turker 2009). In turn, this sensitivity will affect the extent to which employees will identify with their organization. In contrast, those low in empathy do not react strongly to the welfare of others in need. These individuals tend to be less affected by others’ well-being, including those outside of the organization. Thus, employees low in empathy are likely to be less sensitive to how their organization treats external stakeholders, and as a result, their CSR perceptions are less likely to affect their organizational identification. On this basis, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2

Empathy moderates the relationship between perceived CSR and organizational identification such that the relationship will be stronger for employees with high levels of empathy and weaker for those with low levels of empathy.

Organizational Identification and Voluntary Pro-environmental Behavior

Research that has linked organizational identification to employee behavior (e.g., Brammer et al. 2014; Jones 2010; Mael and Ashforth 1992) suggests that when employees incorporate various aspects of their organization into how they define themselves, any perceived differences between their own interests and those of their employer are reduced, thereby fostering a stronger alignment between employee and organizational mission and goals. As a result, employees are more likely to internalize their organizations’ values, beliefs and goals as their own (Ashforth et al. 2008; Mael and Ashforth 1992), and in turn, engage in behaviors that are consistent with those values, beliefs and goals (Ashforth and Mael 1989; Jones 2010). For example, Farooq et al. (2016) recently found that when employees identify with an organization that values and believes in the fair and benevolent treatment of its employees, they are more likely to engage in behaviors that exemplify the fair and kind treatment of their co-workers (i.e., interpersonal helping). Moreover, when employees identify with their firm, they become vested in their organization’s success, and therefore, are motivated to engage in behaviors that support the organization (Ashforth and Mael 1989). Consistent with these arguments, organizational identification has been empirically linked to a variety of organizational citizenship behaviors that promote organizational success, including cooperating with work group members (e.g., Bartel 2001), exerting extra effort (e.g., Bartel 2001; Farooq et al. 2016), taking action to protect the organization (e.g., Newman et al. 2016), and promoting their organization to outsiders (e.g., Farooq et al. 2016; Jones 2010; Newman et al. 2016).

Employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior represents a type of workplace behavior that is consistent with a firm’s socially and environmentally responsible values, beliefs and goals (e.g., by enhancing the welfare of an external stakeholder—the natural environment), and that in the aggregate, contributes to organizational success (Boiral 2009; Norton et al. 2015). Previous empirical studies provide support for the impact of employees’ pro-environmental behavior on organizational environmental performance (e.g., Kennedy et al. 2015; Paillé et al. 2014), and research has shown that workplace pro-environmental behavior positively impacts financial performance (e.g., Chen et al. 2002; Tam and Tam 2008). As such, we argue that organizational identification is an important factor that could influence employees’ pro-environmental behavior. Specifically, we suggest that employees who identify with their organization are more likely to internalize that organization’s socially and environmentally responsible values, beliefs and goals and consequently, engage in behaviors that are consistent with and support those values, beliefs and goals, including voluntary pro-environmental behavior. Further, because employees who identify with their firm are vested in their organization’s success, and therefore engage in behaviors that support their firm (Mael and Ashforth 1992), we propose that these employees will engage in pro-environmental behavior, as such behavior contributes to organizational success. Thus, we make the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3

Organizational identification is positively related to employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior.

The Mediating Role of Organizational Identification

The pattern of relationships outlined above point to the potentially far-reaching effects of CSR, such that perceived CSR may indirectly (through organizational identification) influence employees’ workplace pro-environmental behavior. This is in line with Mael and Ashforth’s (1992) model of organizational identification, according to which, management can influence their employees to support their organization in various ways by first encouraging them to identify with their firm through the manipulation of symbols. Consistent with this model, a body of research suggests perceived CSR is an important organizational symbol that can affect employees’ propensity to identify with their organization, and in turn, their tendency to engage in various behaviors that support the firm. For example, Carmeli et al. (2007) reported that employees who perceived their company as socially and environmentally responsible are more likely to identify with their firms, and subsequently, exhibit higher levels of job performance. Jones (2010) showed empirically that due to their organizational identification, employees who more highly value their organization’s volunteerism program have stronger intentions to stay with their company and are more likely to speak favorably about their organization. More recently, Brammer et al. (2014) found that CSR is indirectly related to employee creative effort through organizational identification. In short, organizational identification is a primary mechanism through which perceived CSR affects a wide variety of employee behavior that aims to support the firm (Farooq et al. 2016; Jones 2010).

We accord a similar mediating role to organizational identification. Specifically, we suggest that when employees perceive their organization as one that contributes to some social or environmental good by benefitting various stakeholders (i.e., CSR; Turker 2009), they will be more likely to identify with that company. Consequently, they will be motivated to engage in behavior that seeks to support the organization. In particular, we suggest that because employees identify with a socially and environmentally responsible organization, they will want to support the firm’s CSR program specifically by engaging in behavior that strives to further benefit any one of the stakeholders the firm’s CSR efforts target, such as the natural environment (i.e., behavior that is aligned with the company’s goals, mission and values). One such type of behavior includes environmentally friendly behavior since this behavior promotes the quality of the natural environment by improving organizational environmental performance (Norton et al. 2015). Indirect support for these arguments comes from Ramus and Steger (2000) who claim organizational policies indirectly affect employees’ behavior, and research that has empirically showed corporate policies are an important precursor (directly and indirectly) to workplace pro-environmental behavior (e.g., Norton et al. 2014; Paillé and Raineri 2015; Ramus and Steger 2000). On this basis, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 4

Perceived CSR is indirectly related to employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior through organizational identification.

The Moderating Effect of Empathy on the Indirect Relationship Between Perceived CSR and Voluntary Pro-environmental Behavior Through Organizational Identification

While scarce, empathy has also been studied in the environmental psychology literature. Within this literature, it is argued that empathy can be generated for the environment, and in turn, affect pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors (Schultz 2000). More specifically, environmental psychology scholars (e.g., Berenguer 2007, 2008; Schultz 2000) draw upon the empathy-altruism hypothesis (i.e., empathy motivates helping behavior directed toward those in need; Batson 2009) to suggest that empathetic individuals can take the perspective of, and subsequently, feel for the welfare of the natural environment harmed by anthropogenic agents (i.e., an other in need). These feelings improve one’s attitude toward the environment, and ultimately, motivate behavior that would help improve the quality of the environment. Supporting this theoretical rationale are several studies that have empirically established the link between empathy and environmentally friendly attitudes and behaviors (e.g., Schultz 2000, 2001; Berenguer 2007), which, together, highlight the relevance of empathy for promoting pro-environmental behavior.

Accordingly, we draw upon the empathy-altruism hypothesis to examine how empathy moderates the indirect effect of CSR on employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior through organizational identification. Due to their ability to consider and feel affected by the welfare of the environment, we propose that empathetic employees will have more positive attitudes about the environment. Thus, when these employees identify with their organization as a result of their CSR perceptions, they will be more likely to engage in workplace pro-environmental behavior that supports their firm’s socially and environmentally responsible beliefs, values and goals. In contrast, employees low in empathy do not consider nor are they affected by harm caused to the environment. As a result, these employees are less likely to have positive attitudes toward the environment. Therefore, even though these employees’ identify with their organization as a result of the CSR perceptions, they are less likely to engage in behavior that seeks to improve the quality of the environment. Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 5

Empathy moderates the indirect relationship between perceived CSR and voluntary pro-environmental behavior through organizational identification such that the relationship will be stronger for employees with high levels of empathy and weaker for those with low levels of empathy.

Methodology

Sample and Procedure

To avoid issues associated with common method bias, the hypotheses of this study were tested using 183 supervisor-subordinate dyads from nine large- and medium-sized casinos and hotels in Guangdong China and Macau. Specifically, we followed guidelines (e.g., Podsakoff et al. 2012) to control for common method bias that may result from common rater effects by obtaining ratings for CSR perceptions, organizational identification and empathy from subordinates, and ratings for employees’ pro-environmental behavior from supervisors. Supervisors’ ratings were deemed appropriate to use because the majority of the participants work in casinos where supervisors and subordinates work alongside each other in a big casino lobby or public office, thereby allowing sufficient opportunities for supervisors to observe employees’ pro-environmental behavior.

To recruit participants, the researchers first discussed the objectives and procedures of the study with the Human Resource (HR) managers from each organization. The HR managers then randomly selected supervisor-subordinate dyads (i.e., HR managers selected the supervisors and one of their employees) and sent information about our study to them. Next, the researchers sent these randomly chosen dyads a recruitment email, informing them of the purpose of the research and a copy of the research survey. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. The researchers collected the completed questionnaires. Out of 600 administered questionnaires (i.e., 300 for supervisors, 300 for subordinates), a total of 366 usable, matched questionnaires (i.e., 183 supervisor–subordinate dyads) were returned, yielding a response rate of 61%. In the subordinate sample, 47% were male. The mean age and organizational tenure of the subordinates were 29.44 and 1.99 years, respectively. In the supervisor sample, 53.6% were male. The mean age and organizational tenure of the supervisors were 36.62 and 3.48 years, respectively.

Measures

The questionnaires were in Chinese, but the measures were originally written in English. The conventional method of back translation (Brislin 1980) was used to translate the measures into Chinese and then back into English. A pilot test of the Chinese version of the questionnaires using 20 employees was conducted to assess their face validity, usability and the quality of the translation. The respondents informed us that all survey measures were meaningful and applicable to their work context. Thus, all scales were deemed appropriate to use in the current context. All items were measured on a scale ranging from 1 ‘completely disagree’ to 5 ‘completely agree’ and all scales demonstrated good reliability (see Table 1).

Perceived CSR

We measured CSR perceptions at the individual level because much like HR policies, employees may not perceive them in the same way (Nishii et al. 2008), thereby questioning the appropriateness of aggregating individual CSR perceptions to a higher level (Morgeson et al. 2013). Specifically, like other studies on CSR in China (e.g., Hofman and Newman 2014; Tian et al. 2015), we used Turker’s (2009) scale, which measures employees’ perceptions that their organization acts responsibly toward the environment and society (e.g., “Our company participates in activities, which aim to protect and improve the quality of the natural environment”), customers (e.g., “Our company respects consumer rights beyond legal requirements”) and the government (e.g., “Our company complies with legal regulations completely and promptly”). We did not include items that measure CSR toward employees in our analyses because scholars do not regard this dimension as CSR but rather, suggest that it represents other already well-defined constructs, such as socially responsible HRM practices, work–family support and high-performance work systems (De Roeck et al. 2016; Farooq et al. 2016). The items we used to measure perceived CSR appear in the “Appendix”.

Organizational Identification

Employees’ rated their organizational identification on six items developed by Mael and Ashforth (1992). Sample items include, “This organization’s successes are my successes” and “When I talk about my organization, I usually say we rather than they.”

Empathy

In an effort to keep the survey short, and because we define empathy as consisting of both cognitive and emotional aspects, we used Dietz and Kleinlogel’s (2014) shortened version of Davis’ (1983) subscales that measure perspective taking (e.g., “I sometimes find it difficult to see things from the other guy’s perspective”) and empathetic concern (e.g., “I am often quite touched by things I see happen”). Following Dietz and Kleinlogel (2014), who found that the 10 items measuring each component of empathy form one overall factor, we averaged these items to compute one measure of empathy (see the “Appendix” for the abbreviated measure of empathy).

Workplace Pro-environmental Behavior

Recently, employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior has been conceptualized and operationalized as a type of environmental organizational citizenship behavior (OCBE; Boiral 2009; Boiral and Paillé 2012; Lamm et al. 2013). Thus, we operationalize voluntary pro-environmental behavior as OCBE and used Lamm et al.’s (2013) twelve item OCBE measure. Sample items include, “He/she is a person who properly disposes of electronic waste” and “He/she is a person who prints double-sided.”

Control Variables

Because some demographic characteristics of employees such as age, gender, and tenure have been linked to organizational identification (e.g., Edwards 2009; Riketta 2005) and general organizational citizenship behaviors (e.g., Van Dyne and Pierce 2004), we controlled for these variables in our analyses.

Data Analyses

Since our hypotheses constitute a test of moderated mediation (also called conditional indirect effects), we followed Preacher et al.’s (2007) method for testing moderated mediation by using Hayes’ (2013) PROCESS macros for SPSS. The PROCESS macros use ordinary least squares path analysis and generate bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CI) based on bootstrapped resamples to avoid problems related to violating assumptions of normality of the sample distribution. Unstandardized regression coefficients are reported for all analyses (Hayes 2013). The PROCESS macros allow for probing the conditional direct and indirect (i.e., moderated mediation) effects by producing bias-corrected CI for these effects at varying levels of the moderator. If the bias-correct CI for an effect did not straddle zero, the effect was significant at p < .05. Following Hayes’ (2013) recommendation, the mediating and moderating variables were mean centered to improve the interpretability of the results.

Results

Descriptive data, intercorrelations, and reliabilities (shown on table diagonals) for all study variables appear in Table 1. Due to the high correlations among the predictor variables included in our model, we first conducted multicollinearity diagnostics in SPSS. The variance inflation factors (VIF) for CSR perceptions (1.62), organizational identification (1.87) and empathy (1.33) revealed that multicollinearity is not a concern.

Next, we used Hayes’ (2013) PROCESS macros, Model 58 to test our proposed hypotheses. Results from these analyses demonstrated that perceived CSR is positively related to organizational identification (b = .57, p < .001, CI [.44, .71]), thereby supporting Hypothesis 1. In support of Hypothesis 2, the results confirmed the interaction effect of empathy on the relationship between perceived CSR and organizational identification (b = .22, p < .05, 95% CI [.02, .42]). Probing this interaction revealed that perceived CSR is more strongly related to organizational identification among employees with high (i.e., the mean plus 1 standard deviation; conditional effect: b = .67, p < .05, 95% CI [.50, .85]) and moderate (i.e., the mean; conditional effect: b = .57, p < .05, 95% CI [.44, .71]) levels of empathy compared to employees with low levels of empathy (i.e., the mean minus 1 standard deviation; conditional effect: b = .48, p < .05, 95% CI [.32, .63]). See Fig. 2. Tests of simple slope significance supported these findings, showing that the slope significantly differed from 0 for both high t(182) = 7.73, p < .05 and low t(182) = 6.08, p < .01 levels of empathy. Supporting Hypothesis 3, we found organizational identification is positively related to pro-environmental behavior (b = .18, p < .05, CI [.03, .34]). The interaction effect of empathy on the indirect relationship between perceived CSR and pro-environmental behavior through organizational identification was also significant (b = .18, p = .05, 95% CI [.00, .37]). Probing this interaction revealed that perceived CSR is not indirectly linked to voluntary pro-environmental behavior via organizational identification for employees who are low in empathy (i.e., the mean minus 1 standard deviation; conditional indirect effect: b = .05, p > .05, 95% CI [−.03, .17]). However, this indirect effect is present for employees who are moderate (i.e., the mean; conditional indirect effect: b = .10, p < .05, 95% CI [.02, .24]) and high (i.e., the mean plus 1 standard deviation; conditional indirect effect: b = .18, p < .05, 95% CI [.03, .38]) in empathy (see Fig. 3). Tests of simple slope significance supported these findings, showing that the slope did not significantly differ from 0 at low levels of empathy t(182) = .97, p > .05, but did significantly differ from 0 at high levels of empathy t(182) = 2.01, p < .05. Taken together, these findings support our fourth and fifth hypotheses that perceived CSR is indirectly linked to pro-environmental behavior through organizational identification, but only among empathetic employees. See Tables 2 and 3 for the model summaries.

Discussion

Given the positive effects of employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior for the natural environment, organizations and its members, it is important for researchers to investigate these behaviors. While a body of research has begun to identify the antecedents to workplace pro-environmental behavior, greater attention needs to be paid to the processes and mechanisms through which these antecedents affect employees’ environmentally responsible behavior, and under which conditions any such effects are enhanced and/or attenuated (Norton et al. 2015). Accordingly, we sought to contribute to this body of research by examining how and when perceived CSR affects employee engagement in voluntary pro-environmental behavior. Data from supervisor-subordinate dyads supported all of the hypotheses specified in our theoretical model. Specifically, replicating previous research on the microfoundations of CSR, we found that when employees perceive their organizations as socially and environmentally responsible, they are more likely to identify with their organization. Extending this research, our results show that this relationship is stronger for empathetic employees. We also found that perceived CSR indirectly impacts employees’ environmentally friendly behavior through their organizational identification, but only among empathetic employees. That is, the indirect link between perceived CSR and workplace pro-environmental behavior through organizational identity is only present for those who demonstrate moderate and high levels of empathy. These findings point to the important roles CSR activities, organizational identification and empathy play in predicting employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior, and offer important theoretical and managerial implications.

Theoretical Implications

To begin, the current study advances the growing body of research on workplace pro-environmental behavior in several ways. First, we identify another organizational predictor of pro-environmental behavior. By examining the predictive role of CSR perceptions, our research echoes previous studies (e.g., Norton et al. 2014; Paillé and Raineri 2015) to highlight how some of the antecedents of employees’ pro-environmental behavior are rooted in employees’ perceptions of their employer’s socially and environmentally responsible policies and practices. Second, our study answers calls (e.g., Norton et al. 2015) for more research on the underlying mechanisms linking antecedents with workplace pro-environmental behavior. In doing so, we provide an additional explanation as to how policies and practices implemented at the firm level impact employee behavior. Specifically, our results show that employees increase their organizational identification when they perceive their company as socially and environmentally responsible, and in turn, support their firm’s CSR activities by engaging in voluntary pro-environmental behavior. Third, we not only empirically examined the mechanism that channels CSR to pro-environmental behavior, but we also established a boundary condition (i.e., empathy) to this indirect effect. This finding indicates that employees’ environmental performance is contingent on empathetic concern. More specifically, this result demonstrates that given their (in)ability to take the perspective of and feel for the welfare of the natural environment, employees higher (lower) in empathy are more (less) likely to engage in voluntary pro-environmental behavior when they identify with their organization as a result of their CSR perceptions. Overall, our research contributes to the workplace pro-environmental behavior literature by providing a deeper understanding of how both organizational and individual-level factors interact to influence employees’ pro-environmental behavior.

This research also contributes to the nascent literature on the microfoundations of CSR. Our study extends initial research (e.g., Vlachos et al. 2014) that has linked perceived CSR to employees’ engagement in behavior related to their firms’ CSR program by demonstrating that this effect extends beyond employees’ engagement in general CSR-specific behavior. Our finding that this relationship is indirect also answers recent calls for more research that investigates what influences employees to carry out CSR activities (Aguinis and Glavas 2012). Specifically, our research suggests that employees’ engagement in CSR-specific behavior is rooted, at least to some extent, in employees’ identification with their organization. Further, our finding that the link between perceived CSR and organizational identification is moderated by empathy extends emerging research that has begun to investigate the boundary conditions to the relationship between perceived CSR and organizational identification (e.g., De Roeck et al. 2016; Farooq et al. 2016). By identifying empathy as an additional boundary condition that affects the CSR-organizational identification relationship, we provide a more comprehensive understanding of the nature of this relationship. In particular, our study suggests that empathy can alter the way CSR perceptions affect the extent to which employees identify with their organization.

Finally, our research contributes to the empathy literature by answering calls to advance the empirical investigation of empathy in management research (e.g., Bagozzi 2003; Dietz and Kleinlogel 2014). Specifically, our research sheds light on how empathy can impact employees’ identification with their organization and their engagement in behavior related to their firm’s CSR activity. In doing so, our research highlights the important role empathy plays in influencing employees’ workplace attitudes and behaviors.

Managerial Implications

The findings of this study also provide important practical implications. Our results demonstrate that when employees perceive their organization as socially responsible, firms benefit through enhanced employee environmental performance. Thus, one implication of our research for companies who wish to increase their environmental performance through employees’ pro-environmental behavior is for these firms to take steps to develop their employees’ CSR perceptions. While not shown in the current research, they could for example, communicate their CSR initiatives to employees through newsletters, training programs and/or mission statements. Further, given the motivational contributions of organizational identification to employee performance (Korschun et al. 2014) and other important employee outcomes (e.g., extra effort and organizational citizenship behaviors; Ashforth and Mael 1989; Farooq et al. 2016; Jones 2010), our study points to the value of fostering employees’ identification by implementing CSR activities. Finally, our findings that empathy moderates the effect of perceived CSR on organizational identification and the indirect effect of perceived CSR on employees’ pro-environmental behavior via organizational identification provide training implications. Specifically, our results show that empathetic employees are more inclined to identify with their organization when they perceive their firm as socially and environmentally responsible, and are more likely to engage in pro-environmental behavior when they identify with their organizations as a result of their CSR perceptions. Taken together, these findings indirectly suggest that organizations might benefit from implementing training programs in empathy. Drawing from past research that has shown perspective taking (i.e., the cognitive component of empathy) improved for college students who received training in empathy (e.g., Hatcher et al. 1994), we suggest one possibility is to first train employees in perspective taking. For example, it may be fruitful to train employees to ask themselves “how can my workplace behavior harm external stakeholders?”

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the contributions of the current study, several limitations warrant mention that should be addressed by future research. First, because our study examined casinos and hotels located in China and Macau, the generalizability of our findings to other industries and cultures remains to be established. Specifically, it is not clear whether the data might have been biased due to the unique nature of the hospitality industry (e.g., some issues like waste of food scraps and consumption of air conditioning are unique in the hospitality industry). Additionally, we do not know whether or how the paradox some employees may feel as a result of working for a socially and environmentally responsible organization that supports a practice often criticized on ethical grounds (i.e., gambling) may impact the relationships studied in the current research. Moreover, the fact that this study was conducted entirely in China may limit the generalizability of our findings to other cultural contexts because cross-culture theories suggest that reactions to perceived CSR vary among employees from different cultures (Rupp et al. 2013). Thus, future research should seek to replicate our findings in other organizational contexts and cultures.

A second limitation of our research arises from the cross-sectional design of the current study, precluding inferences about causality. We argue, however, that our hypothesized causal ordering is plausible given the consistent findings that CSR is an antecedent to employee outcomes (see Aguinis and Glavas 2012 for a review), not vice versa. Nevertheless, we encourage future research to adopt experimental and/or longitudinal designs to test the hypothesized causal ordering proposed in the current research.

A third limitation relates to our use of supervisors’ ratings of employees’ pro-environmental behavior. Although using supervisors’ ratings avoids issues associated with common method bias and several precautions were taken to encourage accurate ratings (e.g., we ensured anonymity, encouraged honest responding and clearly indicated that the organizations would not have access survey responses), it has been shown that supervisors’ ratings of employees’ organizational citizenship behavior (a construct similar to voluntary pro-environmental behavior) can be affected by employees’ impression management techniques (Bolino et al. 2006). Further, although the supervisors in our sample have regular contact with their subordinates, it may be the case that supervisors do not see all of the environmentally responsible behavior their employees engage in on a daily basis. Thus, future research should obtain ratings of workplace pro-environmental behavior from multiple sources.

A fourth limitation stems from our operationalization of employees’ pro-environmental behavior. Specifically, our measure considers only very specific conservation behaviors that people may also engage in at home. Thus, it may be argued that employees engage in these behaviors out of habit rather than because of their CSR perceptions and organizational identification. Future research should seek to determine the extent to which employees engage in the same pro-environmental behaviors examined in the current research at home. Doing so would provide insights into the extent to which employees engage in these behaviors as a result of habit, as well as point to any potential spill over effects (from private to public sphere and vice versa). It is also important that future research replicate our findings using more workplace-specific measures of pro-environmental behavior (e.g., Boiral and Paillé 2012).

In addition to addressing the limitations of our research, we encourage future research to identify other potential mediating and moderating variables to the relationship between CSR perceptions and employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior. For example, future research should investigate the potential mediating role of organizational pro-environmental work climate, a variable shown to mediate the effects of the presence an organizational environmental policy and employees’ environmental behavior (Norton et al. 2014). Future research should also examine other variables that may moderate the relationships examined in the current research. One potential variable may be environmentally specific transformational leadership. Given its focus on using the four transformational leadership behaviors to influence environmental sustainability (Robertson and Barling 2013), environmentally specific transformational leaders may influence employees’ propensity to identify with their organization in the first instance, and as a result, their likelihood to engage in behaviors that would support their firm’s CSR program.

Conclusion

Our study contributes to the growing body of research on the predictors of workplace pro-environmental behavior by identifying perceived CSR as an additional antecedent that is indirectly related to employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior through organizational identification, and by showing that these relationships depend upon empathy. Taken together, these findings enhance our understanding of the processes and conditions under which perceived CSR relates to workplace pro-environmental behavior.

Notes

It is important to note that empathy is conceptually similar to, yet distinct from, third-party justice judgments (i.e., innate moral and emotional reactions—usually anger- to the perceived unfair treatment of others; Rupp 2011). Specifically, both consist of cognitive and emotional components. That is, feeling empathy and experiencing third-party justice judgments both involve drawing one’s attention to some wrongful event (i.e., cognitive component) and exacerbating feelings toward the event (i.e., emotional component).

References

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility a review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4), 932–968.

Andersson, L., Jackson, S. E., & Russell, S. V. (2013). Greening organizational behavior: An introduction to the special issue. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(2), 151–155.

Ashforth, B. E., Harrison, S. H., & Corley, K. G. (2008). Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. Journal of Management, 34(3), 325–374.

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39.

Bagozzi, R. P. (2003). Positive and negative emotions in organizations. Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline, 12, 176–193.

Bartel, C. A. (2001). Social comparisons in boundary-spanning work: Effects of community outreach on members’ organizational identity and identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(3), 379–413.

Batson, C. D. (1990). Self-report ratings of empathic emotion. In N. Eisenberg & J. Strayer (Eds.), Empathy and its development (pp. 356–360). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Batson, C. D. (2008). Empathy-induced altruism motivation. Paper presented at the inaugrual Herzliya symposium on “prosocial motives, emotions and beavior”, Herzliya, Israel.

Batson, C. D. (2009). These things called empathy: Eight related but distinct phenomena. In J. Decety & W. Ickes (Eds.), The social neuroscience of empathy (pp. 3–15). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Batson, C. D., & Shaw, L. L. (1991). Encouraging words concerning the evidence for altruism. Psychological Inquiry, 2(2), 159–168.

Berenguer, J. (2007). The effect of empathy in proenvironmental attitudes and behaviors. Environment and Behavior, 39(2), 269–283.

Berenguer, J. (2008). The effect of empathy in environmental moral reasoning. Environment and Behavior, 42(1), 110–134.

Bissing-Olson, M., Iyer, A., Fielding, S., & Zacher, H. (2013). Relationships between daily affect and pro-environmental behavior at work: The moderating role of pro-environmental attitude. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(2), 156–175.

Boiral, O. (2009). Greening the corporation through organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(2), 221–236.

Boiral, O., & Paillé, P. (2012). Organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: Measurement and validation. Journal of Business Ethics, 109(4), 431–445.

Bolino, M. C., Varela, J. A., Bande, B., & Turnley, W. H. (2006). The impact of impression management tactics on supervisor ratings of organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(3), 281–297.

Brammer, S., He, H., & Mellahi, K. (2014). Corporate social responsibility, employee organizational identification, and creative effort: The moderating impact of corporate ability. Group and Organization Management, 40(3), 323–352.

Brammer, S., Millington, A., & Rayton, B. (2007). The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(10), 1701–1719.

Brammer, S. J., & Pavelin, S. (2006). Corporate reputation and social performance: The importance of fit. Journal of Management Studies, 43(3), 435–455.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. Handbook of Cross-cultural Psychology, 2(2), 349–444.

Cantor, D. E., Morrow, P. C., & Montabon, F. (2012). Engagement in environmental behaviors among supply chain management employees: An organizational support theoretical perspective. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 48(3), 33–51.

Carmeli, A., Gilat, G., & Waldman, D. A. (2007). The role of perceived organizational performance in organizational identification, adjustment and job performance. Journal of Management Studies, 44(6), 972–992.

Chen, Z., Li, H., & Wong, C. T. (2002). An application of bar-code system for reducing construction wastes. Automation in Construction, 11(5), 521–533.

Chen, X., Peterson, M., Hull, V., Lu, C., Lee, G. D., Hong, D., et al. (2011). Effects of attitudinal and sociodemographic factors on pro-environmental behavior in urban China. Environmental Conservation, 38(1), 45–52.

Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 113.

De Roeck, K., El Akremi, A., & Swaen, V. (2016). Consistency matters! How and when does corporate social responsibility affect employees’ organizational identification? Journal of Management Studies. doi:10.1111/joms.12216.

Detert, J. R., Treviño, L. K., & Sweitzer, V. L. (2008). Moral disengagement in ethical decision making: A study of antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 374.

Dietz, J., & Kleinlogel, E. P. (2014). Wage cuts and managers’ empathy: How a positive emotion can contribute to positive organizational ethics in difficult times. Journal of Business Ethics, 119(4), 461–472.

Duan, C., & Hill, C. E. (1996). The current state of empathy research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43(3), 261.

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(2), 239–263.

Edwards, M. R. (2009). HR, perceived organisational support and organisational identification: An analysis after organisational formation. Human Resource Management Journal, 19(1), 91–115.

Erdogan, B., Bauer, T. N., & Taylor, S. (2015). Management commitment to the ecological environment and employees: Implications for employee attitudes and citizenship behaviors. Human Relations, 68(11), 1669–1691.

Farooq, O., Rupp, D., & Farooq, M. (2016). The multiple pathways through which internal and external corporate social responsibility influence organizational identification and multifoci outcomes: The moderating role of cultural and social orientations. Academy of Management Journal. doi:10.5465/amj.2014.0849.

Flannery, B. L., & May, D. R. (2000). Environmental ethical decision making in the U.S. metal-finishing industry. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 642–662.

Glavas, A., & Godwin, L. N. (2013). Is the perception of ‘goodness’ good enough? Exploring the relationship between perceived corporate social responsibility and employee organizational identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(1), 15–27.

Graves, L. M., Sarkis, J., & Zhu, Q. (2013). How transformational leadership and employee motivation combine to predict employee proenvironmental behaviors in China. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 35, 81–91.

Haslam, S. A., & Ellemers, N. (2005). Social identity in industrial and organizational psychology: Concepts, controversies and contributions. International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 20(1), 39–118.

Hatcher, S. L., Nadeau, M. S., Walsh, L. K., Reynolds, M., Galea, J., & Marz, K. (1994). The teaching of empathy for high school and college students: Testing Rogerian methods with the Interpersonal Reactivity Index. Adolescence, 29(116), 961.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Hofman, P. S., & Newman, A. (2014). The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment and the moderating role of collectivism and masculinity: Evidence from China. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(5), 631–652.

Holland, R. W., Aarts, H., & Langendam, D. (2006). Breaking and creating habits on the working floor: A field-experiment on the power of implementation intentions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(6), 776–783.

Jones, D. A. (2010). Does serving the community also serve the company? Using organizational identification and social exchange theories to understand employee responses to a volunteerism programme. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(4), 857–878.

Jones, D. A., Willness, C. R., & Madey, S. (2014). Why are job seekers attracted by corporate social performance? Experimental and field tests of three signal-based mechanisms. Academy of Management Journal, 57(2), 383–404.

Kennedy, S., Whiteman, G., & Williams, A. (2015). Sustainable innovation at interface: Workplace pro-environmental behavior as a collective driver for continuous improvement. In J. L. Robertson & J. Barling (Eds.), The psychology of green organizations (pp. 351–377). New York: Oxford University Press.

Kim, A., Kim, Y., Han, K., Jackson, S. E., & Ployhart, R. E. (2014). Multilevel influences on voluntary workplace green behavior: Individual differences, leader behavior, and coworker advocacy. Journal of Management. doi:10.1177/0149206314547386.

Kim, H. R., Lee, M., Lee, H. T., & Kim, N. M. (2010). Corporate social responsibility and employee–company identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(4), 557–569.

Korschun, D., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Swain, S. D. (2014). Corporate social responsibility, customer orientation, and the job performance of frontline employees. Journal of Marketing, 78(3), 20–37.

Lamm, E., Tosti-Kharas, J., & King, C. E. (2015). Empowering employee sustainability: Perceived organizational support toward the environment. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(1), 207–220.

Lamm, E., Tosti-Kharas, J., & Williams, E. G. (2013). Read this article, but don’t print it: Organizational citizenship behavior toward the environment. Group and Organization Management, 38(2), 163–197.

Lamond, D., Dwyer, R., Arendt, S., & Brettel, M. (2010). Understanding the influence of corporate social responsibility on corporate identity, image, and firm performance. Management Decision, 48(10), 1469–1492.

Mael, F., & Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(2), 103–123.

Mencl, J., & May, D. R. (2009). The effects of proximity and empathy on ethical decision-making: An exploratory investigation. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(2), 201–226.

Morgeson, F. P., Aguinis, H., Waldman, D. A., & Siegel, D. S. (2013). Extending corporate social responsibility research to the human resource management and organizational behavior domains: A look to the future. Personnel Psychology, 66(4), 805–824.

Muller, A. R., Pfarrer, M. D., & Little, L. M. (2014). A theory of collective empathy in corporate philanthropy decisions. Academy of Management Review, 39(1), 1–21.

Newman, A., Miao, Q., Hofman, P. S., & Zhu, C. J. (2016). The impact of socially responsible human resource management on employees’ organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating role of organizational identification. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(4), 440–455.

Nishii, L. H., Lepak, D. P., & Schneider, B. (2008). Employee attributions of the “why” of HR practices: Their effects on employee attitudes and behaviors, and customer satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 61(3), 503–545.

Norton, T. A., Parker, S. L., Zacher, H., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2015). Employee green behavior: A theoretical framework, multilevel review, and future research agenda. Organization & Environment, 28(1), 103–125.

Norton, T. A., Zacher, H., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2014). Organizational sustainability policies and employee green behavior: The mediating role of work climate perceptions. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 38, 49–54.

Orlitzky, M., Schmidt, F. L., & Rynes, S. L. (2003). Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organization Studies, 24(3), 403–441.

Paillé, P., Chen, Y., Boiral, O., & Jin, J. (2014). The impact of human resource management on environmental performance: An employee-level study. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(3), 451–466.

Paillé, P., & Raineri, N. (2015). Linking corporate policy and supervisory support with environmental citizenship behaviors: The role of employee environmental beliefs and commitment. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2548-x.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227.

Ramus, C. A., & Steger, U. (2000). The roles of supervisory support behaviors and environmental policy in employee eco-initiatives at leading-edge European companies. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 605–626.

Riketta, M. (2005). Organizational identification: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66(2), 358–384.

Robertson, J. L., & Barling, J. (2013). Greening organizations through leaders’ influence on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(2), 176–194.

Robertson, J. L., & Barling, J. (2015). Introduction. In J. L. Robertson & J. Barling (Eds.), The psychology of green organizations (pp. 3–11). New York: Oxford University Press.

Rupp, D. E. (2011). An employee-centered model of organizational justice and social responsibility. Organizational Psychology Review, 1(1), 72–94.

Rupp, D. E., Shao, R., Thornton, M. A., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2013). Applicants’ and employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: The moderating effects of first-party justice perceptions and moral identity. Personnel Psychology, 66(4), 895–933.

Schultz, P. W. (2000). Empathizing with nature: Toward a social-cognitive theory of environmental concern. Journal of Social Issues, 56, 391–406.

Schultz, P. W. (2001). Assessing the structure of environmental concern: Concern for self, other people and the biosphere. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21(4), 1–13.

Servaes, H., & Tamayo, A. (2013). The impact of corporate social responsibility on firm value: The role of customer awareness. Management Science, 59(5), 1045–1061.

Shen, Z., Liu, X., & Zhou, X. (2008). Research on state-owned enterprise reform: In view of social responsibility. China Industrial Economics, 9, 141–149.

Stanwick, P. A., & Stanwick, S. D. (1998). The relationship between corporate social performance, organizational size, financial performance, and environmental performance: An empirical examination. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(2), 195–204.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. S. Worchel, 8, 7–24.

Tam, V. W. Y., & Tam, C. M. (2008). Waste reduction through incentives: A case study. Building Research & Information, 36(1), 37–43.

Tian, Q., Liu, Y., & Fan, J. (2015). The effects of external stakeholder pressure and ethical leadership on corporate social responsibility in China. Journal of Management & Organization, 21(4), 388–410.

Turker, D. (2009). Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(4), 411–427.

Valentine, S., & Fleischman, G. (2008). Ethics programs, perceived corporate social responsibility and job satisfaction. Journal of Business Ethics, 77(2), 159–172.

Van Dyne, L., & Pierce, J. L. (2004). Psychological ownership and feelings of possession: Three field studies predicting employee attitudes and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(4), 439–459.

Van Houten, R. V., Nau, P. A., & Merrigan, M. (1981). Reducing elevator energy use: A comparison of posted feedback and reduced elevator convenience. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 14(4), 377–387.

Verbeke, W., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2002). A situational analysis on how salespeople experience and cope with shame and embarrassment. Psychology & Marketing, 19(9), 713–741.

Vlachos, P. A., Panagopoulos, N. G., & Rapp, A. A. (2014). Employee judgments of and behaviors toward corporate social responsibility: A multi-study investigation of direct, cascading, and moderating effects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(7), 990–1017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Abbreviated CSR Scale (Turker 2009)

-

1.

Our company participates in activities, which aim to protect and improve the quality of the natural environment.

-

2.

Our company makes investment to create a better life for future generations.

-

3.

Our company implements special programs to minimize its negative impact on the natural environment.

-

4.

Our company targets sustainable growth, which considers future generations.

-

5.

Our company supports nongovernmental organizations working in problematic areas.

-

6.

Our company contributes to campaigns and projects that aim to promote the well-being of the society.

-

7.

Our company encourages its employees to participate in voluntary activities.

-

8.

Our company respects consumer rights beyond the legal requirements.

-

9.

Our company provides full and accurate information about its product to its customers.

-

10.

Customer satisfaction is highly important for our company.

-

11.

Our company always pays its taxes on a regular and continuing basis.

-

12.

Our company complies with legal regulations completely and promptly.

Abbreviated Empathy Scale (Dietz and Kleinlogel 2014)

-

1.

I sometimes find it difficult to see things from the ‘‘other guy’s’’ perspective.

-

2.

I sometimes try to understand my friends better by imagining how things look from their perspective.

-

3.

When I’m upset at someone, I usually try to ‘‘put myself in his shoes’’ for a while.

-

4.

Before criticizing somebody, I try to imagine how I would feel if I were in their place.

-

5.

I often have tender, concerned feelings for people less fortunate than me.

-

6.

Sometimes I don’t feel very sorry for other people when they are having problems.

-

7.

When I see someone being taken advantage of, I feel kind of protective toward them.

-

8.

Other people’s misfortunes do not usually disturb me a great deal.

-

9.

When I see someone being treated unfairly, I sometimes don’t feel very much pity for them.

-

10.

I am often quite touched by things I see happen.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, Q., Robertson, J.L. How and When Does Perceived CSR Affect Employees’ Engagement in Voluntary Pro-environmental Behavior?. J Bus Ethics 155, 399–412 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3497-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3497-3