Abstract

This paper contributes to growing research exploring employee attitudinal and behavioral reactions to organizational corporate social responsibility initiatives focused on environmental and social responsibility and sustainability. Drawing on social identity theory, we develop and test a moderated-mediation model where employees’ organizational identification mediates the relationship between their perceptions of organizational CSR initiatives and their work engagement and organizational citizenship behaviors, but this relationship is positive only when employees value the role of organizations in supporting environmental and social causes. In a survey of 250 employees from a variety of German organizations, across a range of industry sectors, our hypotheses were fully supported. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A growing body of research examines, and finds support, for a positive relationship between employee perceptions of their organization’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives—here defined as organizational initiatives focused on environmental and social responsibility and sustainability (Turker, 2009a)—and their work and organization-directed attitudes and behaviors (for reviews, see Glavas, 2016; Gond, El Akremi, Swaen, & Babu, 2017). Drawing predominantly from social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), various studies have confirmed positive relationships between employees’ perceptions of organizational CSR initiatives and their organizational identification (e.g., Kim, Lee, Lee, & Kim, 2010), affective organizational commitment (e.g., Brammer, Millington, & Rayton, 2007; Mueller, Hattrup, Spiess, & Lin-Hi, 2012), work engagement (e.g., Glavas, 2016), and organizational citizenship behaviors (Fu, Ye, & Law, 2014; Hansen, Dunford, Boss, Boss, & Angermeier, 2011). According to these studies, CSR matters because employees identify with, and are attracted to, organizations that invest in policies that “do good” for the environment and wider society (De Roeck & Delobbe, 2012; Rupp, Ganapathi, Aguilera, & Williams, 2006; Treviño, Weaver, & Brown, 2008).

Within this emerging body of work, studies have also begun to explore potential boundary conditions of these relationships. Of particular interest has been research that challenges the assumption that all individuals are attracted to organizations that invest in CSR activities (e.g., Coldwell, Billsberry, Van Meurs, & Marsh, 2008). For example, Turker (2009a) reports that the positive relationship between employees’ perceptions of their organizations CSR and their affective organizational commitment is significantly stronger for employees who recognize the importance of CSR and value a role for organizations beyond mere profit maximization (see also Crawshaw, Van Dick, & Boodhoo, 2014; Peterson, 2004; Rupp, Shao, Thornton, & Skarlicki, 2013).

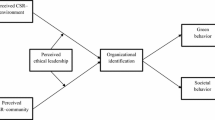

We extend this research by testing a moderated-mediation model, where (1) employees’ organizational identification mediates the relationship between their perceptions of their organization’s CSR policies for environmental and social responsibility and sustainability and their work engagement and OCB and (2) the nature of these relationships is more positive when employees believe that organizations investing in CSR are important than when they do not (see Fig. 1). Thus, while our research seeks to replicate the findings of extant studies, we contribute to this body of work by utilizing social identity theory as a framework for understanding employees’ reactions to employers’ CSR initiatives.

In turn, we provide practioners with further evidence, and explanation, of the potential utility of investing in CSR. While early CSR studies tended to focus attention on the environmental (e.g., Williamson, Lynch-Wood, & Ramsay, 2006), financial (e.g., Berrone, Surroca, & Tribó, 2007), and customer (e.g., Castaldo, Perrini, Misani, & Tencati, 2009) implications of an organizational CSR investments, we add to the burgeoning work that highlights the potentially important roles of CSR investment in attracting (Bhattacharya, Sen, & Korschun, 2008; Crawshaw, van Dick, & Boodhoo, 2014; Rupp et al., 2013) and engaging (e.g., Gond et al., 2017) key talent to achieve sustained competitive advantage in challenging business environments (Branco & Rodrigues, 2006; Mirvis, 2012).

CSR and Organizational Identification: the Moderating Role of the Importance of CSR

CSR is a heavily contested term (Carroll, 1999) that may refer to a range of micro and macro, internal and external, policies and initiatives (see Farooq, Rupp, & Farooq, 2017). Our interest is specifically in employee reactions to external-focused CSR initiatives and, as such, we draw on Barnett’s (2007) definition of CSR as the “discretionary allocation of corporate resources towards improving social [and environmental] welfare that serves as a means of enhancing relationships with key stakeholders” (Barnett, 2007, p. 801). In environmental terms, therefore, CSR initiatives may involve strategies for reducing one’s carbon or water footprint or raw material wastage. In social terms, such activities may include philanthropic contributions to local and international social causes (e.g., health and educational), or practices to ensure that strategic partners and suppliers also uphold agreed ethical working principles (Turker, 2009b).

In this paper, we build on the social identity approach and the role of employees’ organizational identification as a possible mediator between the organization’s CSR efforts and employee outcomes. The social identity approach comprises two closely related theories: social identity theory (SIT; Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and self-categorization theory (SCT; Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987). Both theories emphasize the potential for individuals to derive a sense of self from their membership of social groups—that is, from their social identity. To understand behavior in a range of significant social contexts, it is thus necessary to recognize that individuals can—and often do—define their self (“who they think they are”) in social (as “us” and “we”) and not just personal terms (“I” and “me”). Self-categorization theory has helped understand both the determinants and the consequences of self-definition in group-based terms. In this regard, one core insight of SCT is that shared social identity is the basis for mutual social influence (Turner, 1991). This means that when people perceive themselves to share group membership with others in a given context they are motivated to strive actively to reach agreement with them and to coordinate their behavior in relation to activities that are relevant to that identity.

Ashforth and Mael (1989) were the first who explicitly recognized the approach’s potential for organizational behavior. They noted that social identity has considerable capacity to provide a self-definitional and self-referential basis for people’s behavior in the workplace in light of the important role that various groups (e.g., teams, departments, or the organization itself) play in organizational dynamics. Indeed, Ashforth and Mael stated that if the social identity of employees is defined in terms of their membership of a particular organizational unit then they are likely to strive with relevant workmates to achieve positive outcomes for that unit and to perceive the successes (and failures) of that unit as their own. We follow Ashforth and Mael (1989) and define organizational identification as a specific form of social identification which refers to the feeling of oneness with their organization. Research showed that just as high organizational identification is a powerful predictor of individuals’ willingness to commit themselves to a specific organization (or organizational unit), so low identification is a strong predictor of their desire to disengage from and exit the organization—if not physically then psychologically (see, for instance, the meta-analyses by Riketta, 2005; Lee, Park, & Koo, 2015).

More specifically, social identity–based reasearch has shown the benefits of CSR initiatives, not only for the environmental and social good they serve but also for effective employee attraction, retention, and performance (e.g., Rupp et al., 2013). In short, for work-related contexts, social identity theory suggests that organizational CSR initiatives may serve an important relationship-building function for employees, helping them to develop shared identities with their employer in terms of ethics and social values (Rupp, 2011).

However, despite its centrality to this micro-CSR research, few studies have empirically tested the relationship between employees’ perceptions of CSR and their organizational identification and, within these studies, there are mixed findings (e.g., Kim et al., 2010). For example, Fu et al. (2014) and De Roeck & Delobbe (2012) found support for a positive relationship between employee perceptions of CSR and their organizational identification within the Chinese hospitality industry and European oil industries, respectively. Kim et al. (2010), on the other hand, reported no such relationships between employees’ perceptions of CSR and their organizational identification in a study of Korean firms, although they did report significant positive relationships between employees’ participation in CSR initiatives (like volunteering) and their organizational identification. On the whole, however, related research does tend to support these relationships, with various studies reporting positive associations between employee perceptions of organizational CSR initiatives and identity-related constructs such as their affective organizational commitment (Brammer et al., 2007; Collier & Esteban, 2007; Crawshaw et al., 2014; Mueller et al., 2012; Turker, 2009a), highlighting the potential usefulness of social identity theory as a framework for understanding employee reactions to organizational CSR initiatives.

While the majority of this burgeoning research has tended to assume universal positive effects of CSR on employee work-related attitudes and behaviors, a few studies have explored the potential moderating effects of individual differences (e.g., Hemingway, 2005). Individuals differ in their attitudes towards, and analysis of, issues and concerns of ethics and justice in the workplace (e.g., Cropanzano & Stein, 2009; Reynolds, 2006). Thus, CSR activities are likely to only resonate with individuals who share—with their organization—a concern for wider social and environmental issues and, where they do not, these policies and practices are unlikely to motivate them (Coldwell et al., 2008; Mael & Ashforth, 1992).

In related research, Rodrigo and Arenas (2008) categorize three types of employees, those who are committed, indifferent, and actively antagonistic (dissident) of their employers’ CSR policies and practices. Thus, CSR-committed employees are expected to see a fit between their own values and their organization’s and, as such, CSR activities are likely to promote greater organizational identification and work engagement (Rupp, 2011). However, those antagonistic to CSR policies and practices would see a disconnect between their own values and priorities and the priorities of their employer. As such, CSR policies and activities are likely to reduce organizational identification and work engagement (Rodrigo & Arenas, 2008).

Peterson (2004) examined the importance of CSR as a boundary condition of employee reactions to CSR and reported that employee perceptions of their organization’s corporate citizenship activities are positively related to their affective organizational commitment, but only when they value CSR activities highly. When they do not, perhaps when they feel that organizations should be investing more in core business needs (Rodrigo & Arenas, 2008), Peterson (2004) found no significant relationship between corporate citizenship activities and employees’ affective organizational commitment—findings replicated by both Turker (2009a) and Crawshaw et al. (2014). We only found one study by El-Kassar, Messarra, and El-Khalil (2017) who investigated the interaction between organizational CSR activities and employees’ perceived importance of CSR on their organizational identification and normative commitment. In a sample of 287 employees in Lebanon, El-Kassar et al. could confirm the role of organizational identification as a mediator of the link between CSR activities and employees’ normative commitment, but they could not confirm the expected pattern of moderation by importance of CSR. Our study aims to test El-Kassar et al.’s prediction of a moderated effect of CSR on organizational identification. We extend their study, however, by also testing the unfolding relations that identification, in turn, has with employee engagement and organizational citizenship behaviors.

Specifically, we propose that the relationship between employee perceptions of their organizations’ CSR and their organizational identification will be a function of their attitudes regarding the importance of organizational responsibilities for CSR investments. The following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1 Employee perceptions regarding the importance of CSR will moderate the relationship between their perceptions of their own organization’s CSR activities and their organizational identification, where this relationship will only be positive when they value CSR.

Organizational Identification as a Mediator

Employees who identify with their organization perceive a sense of oneness and connectedness with it, and this connection fulfills an important psychological need for belongingness (e.g., Deci, Ryan, Gagne, Leone, Usunov, & Kornazheva, 2001). In turn, with this need for belongingness met, employees’ positive attitudes towards their employer and job are fostered (Haslam, Postmes, & Ellemers, 2003). In contrast, when organizational identification is low, employees are unlikely to fulfill these important belongingness needs, thus resulting in less favorable job and work-related attitudes.

Furthermore, organizational identification fuels employees’ motivation towards their organization, specifically their levels of potential psychological investment in their work and employment (Haslam et al., 2003). Employees with high organizational identification, therefore, tend to view organizational successes and failures as personally relevant (Mael & Ashforth, 1992), thus driving their work engagement and discretionary effort to help attain these shared goals for organizational success (van Dick, Grojean, Christ, & Wieseke, 2006; Lee et al., 2015). Conversely, employees with low organizational identification will be less psychologically invested in their work and employer, less likely to view organizational successes and failures as personally relevant, and thus less inclined to exhibit high levels of work engagement and discretionary effort (Mael & Ashforth, 1992). This positive relationship between employee organizational identification and work engagement and OCB has undergone much empirical testing and is well-established (e.g., Lee et al., 2015; Riketta, 2005; van Dick et al., 2006).

Thus, the link between organizational identification and the dependent variables of the present research, i.e., work engagement and OCBs, is strongly supported by existing research. As noted above, organizational identification should develop more strongly when the group one is a member of is seen as a “good group” in terms of generally positively valued standards and norms. If organizations show that they care for the society and environment, this will be generally seen as such positive standards. We believe, therefore, that organizational identification serves as a mediator, being influenced by CSR perceptions on the one hand and then, in turn, increasing the likelihood for more engagement. In line with this, we found a few studies that have examined and confirmed a main effect of employees’ perceptions of their organizations’ CSR on their work engagement (e.g., Gao, Zhang, & Huo, 2018; Glavas, 2016; Glavas & Piderit, 2009) and OCB (e.g., Hansen et al., 2011), and one study that confirmed organizational identification as a mediator of the relationship between employee perceptions of CSR and their OCB (Fu et al., 2014). However, and as argued above, we believe that the link between CSR and organizational identification will depend not only on the general norms in favor of CSR but also on the individual’s evaluation of such CSR activities by his or her organization. We believe that this perceived importance of CSR will moderate the link between CSR and organizational identification. To date, we could find no research that had explored not only the mediating role of organizational identification in this relationship but also whether or not employee attitudes towards CSR may moderate the indirect relationships of CSR on citizenship and engagement via identification.

Thus, we extend the current research, by developing a moderated-mediation model where employee organizational identification mediates the relationship between their perceptions of CSR and their work engagement and OCB, but this relationship is stronger when they value highly a role for organizations investing in CSR. In short, we propose that when employees view CSR investments as an important role for organizations, their perceptions of organizational CSR initiatives will be positively related to their work engagement and OCB because they share these values for CSR with their employer and thus their organizational identification is high (Coldwell et al., 2008). The following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2 Employee organizational identification will mediate the relationship between their perceptions of organizational CSR initiatives and their work engagement (2a) and OCB (2b), but this mediating relationship will be stronger when they value highly a role for organizations investing in CSR.

Methods

Sample and Procedures

Data was collected using standardized questionnaires distributed through the third author’s networks and via postings on social and professional networks such as Facebook and XING. All participants were provided with a link to an online survey. In total, 252 participants completed the survey but two had more than 50% missing values and were excluded from further analysis. The final sample thus comprised 250 employees. Average age was 40.8 years, length of service was 8.5 years, 46.8% were female, and 37.6% were in management/supervisory positions. The majority of participants were employed in industry (19.2%), IT/consulting (14.4%), or the public sector (12.8%), but other sectors were represented in smaller numbers including banking/insurance (8%), trades (6.4%), transportation (4.8%), tourism (2.8%), and crafts (2.4%). These descriptive statistics suggest a heterogeneous sample with respect to participants’ gender, age, tenure, and employment position. The data is available at the open science framework under https://osf.io/923v6/.

Measures

All items were presented on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree) and surveys were distributed in German. Most scales were available in German, except for the two scales of perceived CSR and importance of CSR developed by Turker (2009b). These were translated and back-translated following the standard back-translation procedure proposed by Brislin (1970).

Employee Perceptions of CSR

CSR was measured using six items developed by Turker (2009b) focusing on organizations’ engagement with activities and campaigns aimed at promoting environmental and social responsibility and sustainability. A sample item for CSR is, “Our company contributes to campaigns and projects that promote the well-being of society.” Cronbach’s alpha was .92.

Importance of CSR

The perceived importance of organizational investments in CSR (ICSR) was measured using the modified version of Etheredge’s (1999) 5-item importance of ethics and social responsibility scale that was developed and used by Turker (2009b). A sample item is, “The overall effectiveness of a business can be determined to a great extent by the degree to which it is socially responsible.” Cronbach’s alpha was .84.

Organizational Identification

Employees’ organizational identification was measured using the 6-item scale by Mael and Ashforth (1992). A sample item is, “When I talk about this organization, I rather say ‘we’ than ‘they’.” Cronbach’s alpha was .88.

Work Engagement

To assess employee work engagement, we used the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale with nine items by Schaufeli, Bakker, and Salanova (2006). The scale comprises three dimensions including vitality (sample item: “At work I feel strong and vigorous”), dedication (sample item: “At work I am very persistent”), and absorption (sample item: “I am absorbed in my job”). The three dimensions are typically highly interrelated (in this study with r’s > .80), and thus an overall score for work engagement was computed. Cronbach’s alpha was .96.

OCB

We measured OCB using six items developed by Williams and Anderson (1991). Three of these items focused on OCB directed towards the organization (sample item: “I often make innovative suggestions”), and three items focused on OCB directed towards other individuals at work (sample item: “I help new colleagues orient”). Within our study, we combined these six items into a single OCB scale with the Cronbach’s alpha which was .78.

Controls

We collected information on participants’ gender, age, organizational tenure, leadership position, and personality as prior research has found these to be potential predictors of our key dependent variables. Personality was measured using the BIG-5 (i.e., agreeableness, openness, conscientiousness, neuroticisim, and extraversion) short scales developed by Gerlitz and Schupp (2005). We also measured and controlled for employees’ perceptions of internal (employee-focussed) CSR policies—those relating to the fairness of internal employment policies and practices. Past organizational justice research has shown that such perceptions predict strongly various employee attitudes and behaviors including their organizational identification, work engagement, and OCB (for a review, see Colquitt, Conlon, Wesson, Porter, & Ng, 2001). To measure employees’ perceptions of internal CSR policies and practices, we used Turker’s (2009b) six-item measure for employee-focused CSR policies. A sample item is, “The managerial decisions related with the employees are usually fair.” Cronbach’s alpha was .89.

To validate the measure of CSR based on perceptions, we also used questions intended to measure CSR more objectively with five items such as “My organization has a mission statement that emphasizes social responsibility towards employees,” “We do have clear CSR regulations in our organization,” or “My organization has a CSR representative.” We averaged the responses on these statements to a scale “objective CSR.” Providing evidence for the validity of Turker’s statements for employee perceptions of CSR, we found a substantial and significant correlation between the subjective and objective CSR measures of r = .40.

Results

All analyses were carried out using SPSS version 22 and the PROCESS macro version 2.16.3 (Hayes, 2018). Conditional indirect effects were examined using bootstrapping, with the number of bootstrap samples set at 5000 and bias-corrected confidence intervals at 95%. Significant (conditional indirect) effects were observed when the lower and upper confidence intervals did not include zero. To aid interpretation of the proposed interaction effect, the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable was plotted at 10%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 90% levels of the moderator.

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations between study variables are presented in Table 1. As can be seen, employee perceptions of their organizations’ CSR policies and practices were significantly and positively related to their organizational identification (r = .26, p < .01), work engagement (r = .26, p < .01), and OCB (r = .19, p < .01).

Regarding our controls, participants’ gender, age, and tenure were not found to be significantly related to any of the main model dependent variables and were thus removed from all subsequent analysis. All other controls were significantly related to one or more of our dependent variables and thus were preserved for our main model testing. Reanalysis of the models without any controls produced virtually identical results.

Model Testing

In Hypothesis 1, we predicted an interactive effect of employee perceptions of organizational CSR policies and practices and their attitudes regarding the importance of CSR on their organizational identification. The interaction was significant (t = 3.44, [.07, .27]) (see Table 2) and simple slope analysis (see Fig. 2) shows that the relationship between CSR and organizational identification was significant and positive at high (90%) levels of perceived importance of CSR (t = 2.32, [.03, .39]) but significant and negative at low (10%) levels of perceived importance of CSR (t = − 2.64, [− .41, − .06]). At moderate (25%, 50%, 75%) levels of perceived importance of CSR, this relationship between employees’ perceptions of their organizations’ CSR policies and practices and organizational identification was non-significant. Hypothesis 1 is, therefore, supported.

As hypothesized, employee organizational identification was significantly and positively related to their work engagement (t = 6.90, [.29, .54]) (see Table 2). Importantly, results also highlighted a conditional indirect effect, whereby organizational identification mediated the positive relationship between employee perceptions of organizational CSR policies and practices and their work engagement at higher (75% and 90%) levels of perceived importance of CSR (75%: γ = .06, [.00, .13]; 90%: γ = .09, [.02, .17]) and mediated the negative relationship between employee perceptions of organizational CSR policies and practices and their work engagement at low (10%) levels of perceived importance of CSR (γ = − .10, [− .19, − .03]). The index of moderated-mediation for this conditional indirect effect is significant (γ = .07, [.03, .12]). Hypothesis 2a is thus supported.

As hypothesized, employee organizational identification was also significantly and positively related to their OCB (t = 4.37, [.09, .23]) (see Table 2). Importantly, results again highlighted a conditional indirect effect, whereby organizational identification mediated the positive relationship between employee perceptions of organizational CSR policies and practices and their OCB at higher (75% and 90%) levels of perceived importance of CSR (75%: γ = .02, [.00, .05]; 90%: γ = .03, [.01, .07]) and mediated the negative relationship between employee perceptions of organizational CSR policies and practices and their OCB at low (10%) levels of perceived importance of CSR (γ = − .04, [− .08, − .01]). The index of moderated-mediation for this conditional indirect effect is significant (γ = .07, [.04, .12]). Hypothesis 2b is supported.

Discussion

Our model was fully supported. As predicted, employee organizational identification mediates the relationship between their perceptions of organizational CSR policies and practices and their work engagement and OCB, and these relationships are positive when they believe organizations have an important role to play in investing in CSR, but negative when they do not. It appears, therefore, that investing resources into CSR that supports environmental and social responsibility and sustainability initiatives will only positively relate to employee organizational identification and their work engagement and OCB when employees share these values for CSR. In contrast, when employees do not value organizations investing in CSR, these initiatives may in fact have a negative relation to organizational identification and work engagement and OCB. We did not predict this negative relation under conditions of low importance but simply expected the positive relation under high importance. However, from a social identity theory’s perspective, the negative relation makes some sense: Identification with an organization reflects a feeling of oneness between self and organization based on the perception of overlap between one’s own and the organization’s values and norms. Thus, if an employee considers CSR as not important but perceives his or her organization as putting an emphasis on CSR activities, this may result in active dis-attachment from it, i.e., lower identification. Future research should, however, replicate this negative effect and look into it more deeply, probably by studying the reasons why some employees perceive CSR as important whereas others do not.

We provide the a test and confirmation of a social identity theory perspective on employees’ reactions to employer CSR. While previous research has been testing parts of our model (e.g., Crawshaw et al., 2014), the present study focuses explicitly on measuring employee organizational identification and exploring its mediating role in the relationship between employee perceptions of CSR and their work engagement and OCB. The meditational role of identification between CSR activities and employee engagement and OCB is also an extension of the study by El-Kassar et al. (2017) who aimed to test the same moderation model as we did but for both organizational identification and normative commitment. Their results, however, only confirmed the moderation of CSR importance for normative commitment but not for identification. A possible reason for the different results (i.e., confirmation of the moderated model for organizational identification in the present study but not by El-Kassar et al.) might be the nature of the samples under study. Lebanon, a heavily under-researched area of the world, may be compared with nearby Iran which was included in Hofstede, 1983 study and showed very different scores on every dimension compared to Germany (i.e., higher power distance, collectivism, masculinity, and uncertainty avoidance). Future studies should systematically explore how these cultural differences impact on the perceptions of CSR and its importance and the resulting effects.

We also meet recent calls for more research exploring the boundary conditions of CSR’s impact, helping to clarify how individual differences in terms of the perceived roles and responsibilities of organizations for delivering environmental and social responsibility and sustainability initiatives may influence whether organizational investments in CSR relate to employee organizational identification, work engagement, and OCB (Glavas, 2016). Only when the organization’s values (here: norms and activities in favor of CSR) match those of the employee (the individual preferences for social responsibility) will positive outcomes such as work motivation and related behaviors result. Indeed, where there is disconnect between individual and organizational attitudes regarding the strategic importance of CSR, we provide tentative evidence that this may lead to negative employee attitudes and behaviors directed towards the organization.

Limitations and Future Research

The findings of this study should be viewed in light of some limitations. First, the data has been collected at one point in time and using self-reports only. As such, we cannot, with any certainty, draw conclusions about causality and our results may be distorted by factors such as social desirability of respondents. This said, we have confidence in the causal ordering of our underlying hypotheses as these are very much in line with previous theorizing on the role of organizational identification and also on employee reactions to CSR (Turker, 2009a). Moreover, while the self-report nature of our data may account for overestimations of our main effects, it is unlikely to account for the conditional indirect effects we observed, and which form the main focus of our research (Siemsen, Roth, & Oliveira, 2010). As Siemsen et al. (2010) and others have well-established, common method bias, far from inflating interaction effects, is more likely to suppress them. Again, however, future research should aim to collect data from multiple, and where appropriate objective, sources in order to provide greater reliability and validity in these findings. A related limitation is the use of personal networks to recruit research participants. Of course, this may have led to a biased and non-representative sample. We do have some confidence in the generalizability of our results due to the fact that we did find variation in every variable and not only agreement to the importance of CSR which would have been in line with a social desirability argument. However, future studies that use representative samples would certainly be desired.

In addition to these methodological requests, we can also reiterate our calls for more micro-CSR research that clearly defines and measures CSR and, in turn, more research that focuses on employee reactions to organizational CSR policies and practices that are directed towards concerns of environmental and social responsibility and sustainability. It is, in our opinion, employee reactions to these policies and practices that have lacked the required theoretical and empirical testing.

This said, our final call is for more research at the intersection of CSR and organizational justice. While great strides are being made to integrate the organizational justice and behavioral ethics literatures (e.g., Crawshaw, Cropanzano, Bell, & Nadisic, 2013; Fortin, Nadisic, Bell, Crawshaw, & Cropanzano, 2016), we see similar opportunities here. Rupp’s (2011) work articulating the potential alternative employee and executive motives for CSR importance provides a potentially useful starting point and framework. Future research should, therefore, examine more specifically these competing motives so that we may further clarify when and why CSR matters to employees. Finally, organizational identification is, of course, not only influenced by CSR perceptions but to a large extend also by leadership variables. In particular, the employee’s direct supervisor’s own identification and his or her group prototypicality can be considered important factors which can both directly influence employee identification and moderate the impact of CSR on identification (see Koivisto & Lipponen, 2015).

Practical Implications

Despite these limitations, we believe our results have practical implications for employers and managers. They provide further evidence that CSR policies and practices have a role to play—alongside other human resources and management initiatives—in attracting, retaining, and motivating employees (see, for instance, Hansen et al., 2011). Our research shows that employees who think CSR is important and who perceive that their organization participates in more CSR identify with the organization more, and are more energized and willing to contribute behaviorally towards the organization. Our study shows that CSR only matters, in human capital management terms, when employees also care about CSR and their employers’ investments in wider environmental and social issues. This has a number of important people management implications. First, we provide further evidence of the importance, when recruiting employees, of matching employee and organizational interests—here investment in CSR. Thus, a clear two-way communication of these interests in any recruitment materials and processes is essential to tease out these shared concerns (Coldwell et al., 2008).

Relatedly, it is essential that the organization effectively communicates internally—to the existing workforce—these interests in, and commitment to, CSR (Garavan & McGuire, 2010). This should help generate, in employees who share these interests, a greater identification and engagement with the organization. However, it also gives the organization an opportunity for open dialogue with employees who may—for whatever reason—not share these interests and indeed be fairly antagonistic towards their employer’s investments in CSR. Through team meetings or appraisal processes for example, employers—through their line managers—can better explain to, and convince, employees of the strategic importance of these investments and, where they cannot, employees may be better placed to make decisions regarding their own future relationship with the organization (Garavan & McGuire, 2010). Indeed, line managers are likely to be the key in this communication, with their own interests in, and engagement with, CSR an important leadership role and modeling role (e.g., Bandura, 1969; Brown, Treviño, & Harrison, 2005).

Conclusion

The present research explored the role of CSR in promoting more positive employee job attitudes and behaviors. Our findings suggest that this relationship may be more complex than previously thought. It seems that an organization’s investments in CSR that is focused on promoting environmental and social responsibility and sustainability may add value beyond the positive effects on relationships with external stakeholder relations (i.e., those with consumers and the wider society). It may, in turn, also have an important role to play in attracting, retaining, and motivating their employees, but only when individuals share these values for CSR. When they do not, such investments may actually be very detrimental to the employment relationship.

References

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14, 20–39.

Bandura, A. (1969). Social learning of moral judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 11, 275–279.

Barnett, M. L. (2007). Stakeholder influence capacity and the variability of financial returns to corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 32, 794–816.

Berrone, P., Surroca, J., & Tribó, J. A. (2007). Corporate ethical identity as a determinant of firm performance: A test of the mediating role of stakeholder satisfaction. Journal of Business Ethics, 76, 35–53.

Brammer, S., Millington, A., & Rayton, B. (2007). The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18, 1701–1719.

Bhattacharya, C. B., Sen, S., & Korschun, D. (2008). Using corporate social responsibility to win the war for talent. MIT Sloan Management Review, 49, 37–44.

Branco, M. C., & Rodrigues, L. L. (2006). Corporate social responsibility and resource-based perspectives. Journal of Business Ethics, 69, 111–132.

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1, 185–216.

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97, 117–134.

Carroll, A. B. (1999). Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Business & Society, 38, 268–295.

Castaldo, S., Perrini, F., Misani, N., & Tencati, A. (2009). The missing link between corporate social responsibility and consumer trust: The case of fair trade products. Journal of Business Ethics, 84, 1–15.

Coldwell, D. A., Billsberry, J., Van Meurs, N., & Marsh, P. J. (2008). The effects of person–organization ethical fit on employee attraction and retention: Towards a testable explanatory model. Journal of Business Ethics, 78, 611–622.

Collier, J., & Esteban, R. (2007). Corporate social responsibility and employee commitment. Business Ethics: A European Review, 16, 19–33.

Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C. O., & Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 425–445.

Crawshaw, J. R., Cropanzano, R., Bell, C. M., & Nadisic, T. (2013). Organizational justice: New insights from behavioral ethics. Human Relations, 66, 885–904.

Crawshaw, J. R., van Dick, R., & Boodhoo, Y. (2014). Corporate social responsibility and organizational commitment: The moderating role of individuals’ attitudes to CSR. Politische Psychologie, 3, 38–50.

Cropanzano, R., & Stein, J. H. (2009). Organizational justice and behavioral ethics: Promises and prospects. Business Ethics Quarterly, 19, 193–233.

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Gagne, M., Leone, D. R., Usunov, J., & Kornazheva, B. P. (2001). Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former eastern bloc country: A cross-cultural study of self-determination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 930–942.

De Roeck, K., & Delobbe, N. (2012). Do environmental CSR initiatives serve organizations’ legitimacy in the oil industry? Exploring employees’ reactions through organizational identification theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 110, 397–412.

El-Kassar, A. N., Messarra, L. C., & El-Khalil, R. (2017). CSR, organizational identification, normative commitment, and the moderating effect of the importance of CSR. The Journal of Developing Areas, 51, 409–424.

Etheredge, J. M. (1999). The perceived role of ethics and social responsibility: An alternative scale structure. Journal of Business Ethics, 18, 51–64.

Farooq, O., Rupp, D. E., & Farooq, M. (2017). The multiple pathways through which internal and external corporate social responsibility influence organizational identification and multifoci outcomes: The moderating role of cultural and social orientations. Academy of Management Journal, 60, 954–985.

Fortin, M., Nadisic, T., Bell, C. M., Crawshaw, J. R., & Cropanzano, R. (2016). Beyond the particular and universal: Dependence, independence, and interdependence of context, justice, and ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 137, 639–647.

Fu, H., Ye, B. H., & Law, R. (2014). You do well and I do well? The behavioral consequences of corporate social responsibility. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 40, 62–70.

Gao, Y., Zhang, D., & Huo, Y. J. (2018). Corporate social responsibility and work engagement: Testing a moderated mediation model. Journal of Business and Psycholology, 33, 661–673.

Garavan, T. N., & McGuire, D. (2010). Human resource development and society: Human resource development’s role in embedding corporate social responsibility, sustainability, and ethics in organizations. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 12, 487–507.

Gerlitz, J. Y., & Schupp, J. (2005). Zur Erhebung der Big-Five-basierten persoenlichkeitsmerkmale im SOEP. DIW Research Notes, 4, 2005.

Glavas, A. (2016). Corporate social responsibility and employee engagement: Enabling employees to employ more of their whole selves at work. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 796. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00796.

Glavas, A., & Piderit, S. K. (2009). How does doing good matter? Effects of corporate citizenship on employees. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 9, 51–70.

Gond, J. P., El Akremi, A., Swaen, V., & Babu, N. (2017). The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38, 225–246.

Hansen, S. D., Dunford, B. B., Boss, A. D., Boss, R. W., & Angermeier, I. (2011). Corporate social responsibility and the benefits of employee trust: A cross-disciplinary perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 102, 29–45.

Haslam, S. A., Postmes, T., & Ellemers, N. (2003). More than a metaphor: Organizational identity makes organizational life possible. British Journal of Management, 14, 357–369.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (2nd). New York: Guilford.

Hemingway, C. A. (2005). Personal values as a catalyst for corporate social entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics, 60, 233–249.

Hofstede, G. (1983). National cultures in four dimensions: A research-based theory of cultural differences among nations. International Studies of Management & Organization, 13, 46–74.

Kim, H. R., Lee, M., Lee, H. T., & Kim, N. M. (2010). Corporate social responsibility and employee–company identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 95, 557–569.

Koivisto, S., & Lipponen, J. (2015). A leader’s procedural justice, respect and extra-role behavior: The roles of leader in-group prototypicality and identification. Social Justice Research, 28, 187–206.

Lee, E. S., Park, T. Y., & Koo, B. (2015). Identifying organizational identification as a basis for attitudes and behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 141, 1049–1080.

Mael, F., & Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 103–123.

Mirvis, P. (2012). Employee engagement and CSR. California Management Review, 54, 93–117.

Mueller, K., Hattrup, K., Spiess, S. O., & Lin-Hi, N. (2012). The effects of corporate social responsibility on employees’ affective commitment: A cross-cultural investigation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97, 1186–1200.

Peterson, D. K. (2004). The relationship between perceptions of corporate citizenship and organizational commitment. Business & Society, 43(3), 296–319.

Reynolds, S. J. (2006). Moral awareness and ethical predispositions: Investigating the role of individual differences in the recognition of moral issues. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 233–243.

Riketta, M. (2005). Organizational identification: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66, 358–384.

Rodrigo, P., & Arenas, D. (2008). Do employees care about CSR programs? A typology of employees according to their attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 83, 265–283.

Rupp, D. E. (2011). An employee-centered model of organizational justice and social responsibility. Organizational Psychology Review, 1, 72–94.

Rupp, D. E., Ganapathi, J., Aguilera, R. V., & Williams, C. A. (2006). Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: An organizational justice framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27, 537–543.

Rupp, D. E., Shao, R., Thornton, M. A., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2013). Applicants’ and employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: The moderating effects of first-party justice perceptions and moral identity. Personnel Psychology, 66, 895–933.

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire a cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66, 701–716.

Siemsen, E., Roth, A., & Oliveira, P. (2010). Common method bias in regression models with linear, quadratic, and interaction effects. Organizational Research Methods, 13, 456–476.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W.G. Austin, & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Monterey: Brooks/Cole.

Treviño, L. K., Weaver, G. R., & Brown, M. E. (2008). It’s lovely at the top: Hierarchical levels, identities, and perceptions of organizational ethics. Business Ethics Quarterly, 18, 233–252.

Turker, D. (2009a). How corporate social responsibility influences organizational commitment. Journal of Business Ethics, 89, 189–204.

Turker, D. (2009b). Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. Journal of Business Ethics, 85, 411–427.

Turner, J. C. (1991). Social influence. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group. Oxford: Blackwell.

van Dick, R., Grojean, M. W., Christ, O., & Wieseke, J. (2006). Identity and the extra mile: Relationships between organizational identification and organizational citizenship behavior. British Journal of Management, 17, 283–301.

Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 17, 601–617.

Williamson, D., Lynch-Wood, G., & Ramsay, J. (2006). Drivers of environmental behavior in manufacturing SMEs and the implications for CSR. Journal of Business Ethics, 67, 317–330.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Dick, R., Crawshaw, J.R., Karpf, S. et al. Identity, Importance, and Their Roles in How Corporate Social Responsibility Affects Workplace Attitudes and Behavior. J Bus Psychol 35, 159–169 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-019-09619-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-019-09619-w