Abstract

This article uses behavioral theories to develop an ethical decision-making model that describes how psychological factors affect the development of unethical intentions to commit fraud. We evaluate the effects of the dark triad of personality traits (i.e., psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism) on fraud intentions and behaviors. We use a combination of survey results, an experiment, and structural equation modeling to empirically test our model. The theoretical insights demonstrate that psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism affect different parts of the unethical decision-making process. Narcissism motivates individuals to act unethically for their personal benefit and changes their perceptions of their abilities to successfully commit fraud. Machiavellianism motivates individuals not only to act unethically, but also alters perceptions about the opportunities that exist to deceive others. Psychopathy has a prominent effect on how individuals rationalize their fraudulent behaviors. Accordingly, we find that the dark triad elements act in concert as powerful psychological antecedents to fraud behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“The environment of computers, the Cloud and the internet makes cyber fraudsters even more elusive than before. This behavior differs from what investigators are used to, and it is something they will have to adapt their methods to. But even cyber crimes are still likely to be driven by the same psychological profiles found previously; only the behavior may have changed” (KPMG 2013, p. 17).

The question of why and how individuals choose to act unethically continues to vex society. Unethical actions sever relationships and reputations also while having deleterious effects on commerce (Gino et al. 2010). A recent study on fraud by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (2014) found that the 1483 cases they reviewed cost organizations more than $3 billion. Moreover, as reflected in the quote above from a recent KPMG report on fraud, the challenge is great, because the modes by which fraud can be undertaken are constantly changing as new media, financial instruments, and means of conducting transactions evolve. In this paper, we focus on fraud intentions for the purpose of monetary gain and how personality characteristics can lead to these unethical intentions.

Individuals may choose to act unethically for a number of reasons (Brief et al. 2001; Lewicki et al. 1997). Unethical behaviors are defined as acts that are harmful to others and are ‘‘illegal or morally unacceptable to the larger community’’ (Jones 1991, p. 367). Research has begun to unravel important psychological factors that affect an individual’s propensity to engage in unethical behaviors, including fraud (Caruso and Gino 2011; Chugh et al. 2005; Gino and Bazerman 2009; Gino et al. 2010; Gino and Pierce 2009; Kern and Chugh 2009; Mazar et al. 2008; Tenbrunsel and Messick 2004). Although this body of literature continues to grow, questions remain regarding the psychological factors that cause people to behave unethically. Thus, the specific research questions that we seek to address in this research are: what are the personality characteristics that influence fraud and how do these traits influence decision-making processes?

A path to finding the answer to these research questions can be found by examining the literature. Incorporating Rest’s (1986, 1994) psychologically driven ethical decision-making model, Trevino (1986) proposed an interactionist perspective on ethical decision-making behavior conjecturing the need to look at individual differences and contextual variables. We utilize this interactionist perspective to study several personality characteristics, collectively referred to as the dark triad (for a meta-analysis, see O’Boyle et al. 2012), which have been shown to influence unethical activities. The dark triad is a term that refers to the combination of three psychological traits that, when present in combination, are considered to be predictive of callous, self-serving, and manipulative attitudes and behaviors. The three dark triad traits—psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism—have been shown to have an effect on various anti-social behaviors such as fraud (Johnson et al. 2012; Jones 2014).

Even though the dark triad is known to be related to unethical behavior, the question remains of exactly how these psychological traits work together to influence how individuals make ethical decisions (Spain et al. 2014). In fact, scant empirical research exists into how these psychological traits actually affect the decision-making processes of individuals who engage in behaviors such as fraud (Nikitkov et al. 2014). Furthermore, little distinction has been made between the influence of the dark triad on long-term, relationship-based, behaviors and short-term interactions individuals may encounter within work or social routines (Spain et al. 2014).

Consequently, an important goal of this research is to study these behaviors, and learn how these traits influence each of the factors that stimulate fraudulent behaviors during short-term interactions. We use the fraud triangle (Albrecht et al. 1982; Cressey 1953) to explore the effects of the dark triad on fraud behaviors in the context of an online purchasing decision. The fraud triangle is an interactionist perspective on unethical behavior (Trevino 1986) which posits that individuals who engage in fraud have a motivation to engage in the act, the opportunity to take advantage of another individual, and are able to rationalize the actions they are considering within their own code of ethics (Albrecht et al. 1982; Cressey 1953). Additionally, a fourth element, an individual’s capabilities, has been proposed as an additional factor that influences fraudulent behaviors because an individual will assess whether he has the relevant skills or abilities needed to successfully carry out the fraudulent behaviors that he is considering (Wolfe and Hermanson 2004).

This study contributes to research regarding how personality characteristics can lead to unethical behaviors. First, the key implication for theory is that the cognitive and decision-making processes of fraudsters can be affected in different ways by various psychological factors. Thus, when considering the impact of psychological factors upon fraud, we should consider how each factor impacts each of the elements of the fraud triangle in order to develop a better understanding of the decision-making processes used by fraud perpetrators. Our findings, across two empirical studies, support the position that each factor in the dark triad facilitates different parts of the cognitive processes that result in fraud. Psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism each influence factors in the fraud triangle during short-term interactions; however, each trait has a unique influence on different parts of the decision-making processes that result in online consumer fraud. This research also has practical implications. Specifically, this research challenges recommendations that focus on reducing opportunity as the most effective approach to stop fraud (Stone 2015). Based on our study, we endorse a fraud deterrence approach that considers both dispositional and situational factors. An interactionist approach recognizes that the origins of fraud vary by individual (Kandias et al. 2010), and can be used to understand fraud behaviors in a broad array of conditions. Consequently, our study points to the relevance of psychological traits for understanding unethical decision-making and demonstrates how these traits influence fraud behaviors.

Theoretical Foundations

The foremost model for examining fraud, the fraud triangle, emerged from the criminology and sociology domains (Albrecht et al. 1982; Cressey 1953; Sutherland 1983; Morales et al. 2014). The fraud triangle is an interactionist framework and is typically framed as analogous to fire whereby motivation (heat), opportunity (fuel), and rationalization (air) must all exist for fraudulent acts to follow (Albrecht et al. 2012). When presented as a framework, the fraud triangle lays out a set of constructs but does not define how these constructs relate in a causal structural model. However, scholars have suggested that the fraud triangle constructs should be considered in a causal model (Cohen et al. 2010; Rodgers et al. 2014) that better reflects the stages of ethical considerations where moral awareness precedes ethical decision-making (Rest 1994; Jones 1991). Thus, in this paper, we consider these constructs in a causal structural model to better understand how the dark triad traits influence each factor.

The Fraud Triangle

The fraud triangle, as originally proposed, includes three factors: motivation, opportunity, and rationalization (Albrecht et al. 1982). However, to commit an act of fraud, a fraudster also must be capable of deceiving the other party in an exchange (Wolfe and Hermanson 2004). Consequently, individuals must believe that they possess the capabilities to deceive victims to successfully commit an act of fraud. The effects of capabilities of a perpetrator are rooted in how they increase various forms of power and influence exchanges (Albrecht et al. 2007). Thus, technical capabilities may aid in some types of fraud, whereas interpersonal communication skills may be useful in other contexts. Fraudsters use their abilities to foster in their victims a false sense of trust so that they may gain some advantage and influence over their victims (Albrecht et al. 1982; Ramamoorti 2008).

Even when an individual possesses the skills necessary to commit an act of fraud, that person must recognize that some exploitable opportunity exists (Albrecht et al. 2012). The opportunity to commit fraud exists when there is a chance to intentionally exploit the trust of another for gain and the likelihood of being caught or punished seems remote (Ramamoorti 2008). Sometimes, perpetrators recognize gullibility or a lack of cleverness in potential victims that they may exploit (Albrecht et al. 1982). Other opportunities are often the result of weak controls and procedures that may mask or obscure the perpetrator’s fraudulent actions (Cohen et al. 2010). For example, the anonymity of individuals who are engaged in multiple transactions taking place on the Internet can increase the opportunity for fraud by reducing the likelihood that the perpetrator can be subsequently identified and held accountable (Zahra et al. 2005).

The construct of motivation is rooted in the idea that an individual resorts to fraud as a result of encountering some unshareable and unresolvable financial problem (Cressey 1953; Morales et al. 2014). This perspective also is aligned with the concept of ego depletion, where an individual lacks the resources to resist the temptation of engaging in unethical behaviors when the chance of being caught or punished seems remote (Yam et al. 2014). These expectations also are reflected in the moral intensity of the action, which includes estimations of consequences and probabilities of effects (Jones 1991). The most common motivation for committing fraud is the perception that a dishonest act could accrue a financial benefit to the perpetrator (Cohen et al. 2010). However, there also are non-monetary reasons why people may commit fraud (Dorminey et al. 2012). For example, social pressures to be perceived as successful, powerful, or affluent also have been shown to motivate people to commit fraud (Dilla et al. 2013).

An individual also must be willing to rationalize their fraudulent actions, despite their awareness that these actions deviate from common social norms against lying, cheating, or stealing (Reynolds 2006; Albrecht et al. 2012). Individuals rationalizing fraud still hold the same general attitudes toward fraudulent behaviors, but they generally find a reason to excuse their actions because of certain specific situational factors that they use for justifying the anti-social behaviors (Murphy and Dacin 2011). Thus, rationalization is the reconciliation of dishonest intentions with a personal code of ethics that enables one to act dishonestly or immorally in certain contexts (Ramos 2003). For example, one way that fraudsters rationalize their actions is by deflecting blame to their victims who were sufficiently gullible to be duped by the deceit (Ramamoorti 2008). Fraudsters often exhibit a lack of empathy for their victims and they are willing to value personal benefits derived from fraud over the damages they cause to others (Murphy and Dacin 2011). Similarly, individuals are often more willing to steal from an organization they work for than they are from their individual coworkers, because it is more difficult to rationalize fraudulent behaviors when considering the negative impacts to individuals (Greenberg 2002).

In causal models of fraud, rationalization plays a critical role that is distinct from perceptions of motivation, opportunities, or capabilities because rationalization acts as a final critical step in the reasoning processes leading to the development of unethical intentions and ultimately unethical actions (Murphy and Dacin 2011). This sequential process mirrors the progression from moral awareness to moral judgment before the establishment of moral intention and ultimately moral action (Rest et al. 1999; Reynolds 2006). We use these fraud triangle elements to describe how perceptions of motivation, opportunity, capabilities, and rationalization predict fraud behaviors in an interactionist causal model (Cohen et al. 2010). This interactionist approach suggests that fraud behaviors are the result of the same psychological profiles being applied through differing contexts. This implies that psychological factors affect various perceptions of capabilities, opportunities, motivations, and rationalization.

The Dark Triad

Psychologists have identified three related traits, psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism, collectively referred to as the “Dark Triad,” which are all individually linked to financial and other maladaptive behaviors (Babiak 1995; Johnson et al. 2012; Jones 2014; Tang et al. 2008). The dark triad factors describe personality traits that appear to affect all domains of human behaviors ranging from sexuality to ideology (Lee et al. 2013). While each of the dark triad characteristics correlate (Hare 1991), each construct is conceptually distinct from each of the other two constructs (Paulhus and Williams 2002). For example, while both narcissism and psychopathy are associated with impulsivity, psychopathy is associated with dysfunctional forms of impulsivity, while Machiavellianism is associated with functional forms of impulsivity (Jones and Paulhus 2011). As a result, narcissists may thrive in short-term interactions, while psychopaths tend to lack social awareness and engage in more self-destructive behaviors. Consequently, gaps remain in our understanding of how the dark triad factors differentially effect long-term, relationship-based interactions versus short-term exchanges (Spain et al. 2014). Furthermore, each of the traits in the dark triad has a strong inverse relationship with honesty and modesty (Lee and Ashton 2005). Individuals high in any of the traits in the dark triad are more prone to participate in selfish, callous, or unethical behaviors such as engaging in risky financial endeavors (Jones 2014). Therefore, the dark triad is frequently associated with increased criminal activity, including fraud (Lee et al. 2013; Nathanson et al. 2006) and other unethical behaviors in the workplace (Spain et al. 2014). We discuss each of these traits in turn.

Those who are high on Machiavellianism use manipulative behaviors and believe others to be gullible and foolish. A person rated high on Machiavellianism is characterized by holding cynical views of others and the belief that manipulation is a valid and useful method for attaining goals (O’Boyle et al. 2012). People exhibiting Machiavellianism are prone to making unethical decisions and often assume that others would make the same choices (Fehr et al. 1992; Jones and Paulhus 2011). Machiavellianism has been described as a willingness to use manipulation and act immorally (Christie and Geis 1970). Consequently, Machiavellianism has multiple dimensions and is associated with amorality, the desire for control, the desire for status, and a distrust of others (Dahling et al. 2009). Individuals rating high on the Machiavellianism trait are more likely to lie to, steal from, cheat, and mislead others (Fehr et al. 1992; Jones and Paulhus 2009; O’Boyle 2012). Machiavellianism is thought to be a contributing factor to unethical business behaviors of various types (Trevino and Youngblood 1990; Tang et al. 2008) and individuals exhibiting high ratings on Machiavellianism are more likely to defraud others within an organizational context (Harrell and Hartnagel 1976).

A narcissists’ ego and sense of entitlement create desires to boast and engage in other attention-seeking behaviors. Narcissists have a strong need for validation and narcissism is commonly thought to be the result of a lack of socialization that is characterized by a lack of empathetic and consistent childhood interactions (Kernburg 1975). Narcissists project a sense of grandiosity but have an inner fragility and low self-esteem. Narcissism has been described as a pervasive pattern of grandiosity, self-focus, and self-importance (Morf and Rhodewalt 2001). Aspects of narcissism include a willingness to exploit others, entitlement, and self-absorption (Emmons 1987; Millon 1990). Narcissists are generally viewed favorably during initial encounters, but viewed more negatively and prone to arrogance during subsequent interactions (Paulhus 1998). Thus, in short-term interactions such as those involving e-commerce transactions, those who have higher narcissistic traits would generally be more successful in gaining the trust of others. Narcissists expect special treatment and are generally non-empathetic and willing to exploit others. Narcissism is goal-oriented and aimed at getting affirmation, while being insensitive to any social constraints. A narcissist often incorporates entitlement with a strong desire for success and achievement (Ames et al. 2006). Furthermore, narcissistic behaviors and fraud motivation are considered by auditors to be significantly and positively related to fraud risk assessments and unethical financial behavior (Duchon and Drake 2009; Johnson et al. 2012).

Those rated high on psychopathy have been characterized as exhibiting a pattern of intrinsically anti-social behaviors that are based on judgments concerning an elevated importance of one’s own wishes and well-being while, at the same time, minimalizing the rights and well-being of others (Levenson 1992). Psychopathy manifests when a person exhibits a lack of guilt or remorse for actions that harm others. A psychopathic person is impulsive and has little concern for other people or social regulatory mechanisms (O’Boyle et al. 2012) and do not form meaningful personal relationships and, consequently, lack empathy, guilt, and regret when their decisions hurt others (Hare 1991). Psychopathy is demonstrated by the callous, remorseless, manipulation, and exploitation of others (Hare 1991; Lee and Ashton 2005). Psychopaths routinely are untruthful and willing to use dishonesty to their personal advantage (Karpman 1941). Psychopathy may confer some degree of social advantage, because it is highly associated with decisiveness and a willingness to take risks and, therefore, psychopaths may thrive in businesses, chaotic environments, and in leadership roles where stress is high (Babiak and Hare 2006; Babiak et al. 2010; Levenson 1992; Ramamoorti 2008).

The dark triad variables affect a wide range of decisions that result in unethical behavior in a broad range of contexts (Lee et al. 2013). These traits also make it difficult for individuals to develop and maintain trusting relationships with their coworkers, a key basis for developing productive work routines (Robinson and Morrison 1995). Furthermore, the dark triad traits can have serious consequences in terms of overall business performance as there has been empirical support for the notion that negative workplace performance by individuals “poisons” the performance of their work teams (Dunlop and Lee 2004). Accordingly, understanding the role each element in the dark triad plays in decision-making processes is important for understanding how people react to various ethical contexts.

Online Consumer Fraud

Information systems have “flattened” the world and facilitate communication and trade in ways that had been impossible without them (Friedman 2006); however, maladaptive innovations using new technologies have followed on the heels of legitimate transactions. For example, online consumer fraud was reported to cost individuals almost $1 billion annually (IC3 2015). Online consumer fraud is facilitated by online interactions through various communication media. Common online consumer fraud practices include misrepresenting assets during sale and non-delivery of goods or services.

Certain characteristics have made online consumer transactions particularly prone to consumer fraud (Marett and George 2013) and the majority of online consumer fraud occurs through common communication channels like e-mail and webpages (Albrecht et al. 2007). The difficulties in assuring identities during online transactions provide ample opportunity to defraud others and reduces pressures to conform to social norms against fraud (Bürk and Pfitzmann 1990; Nunamaker et al. 1991). The unethical use of information systems occurs as a result of individuals acting on self-interest and the presence, or absence, of punishment and control systems (Chatterjee et al. 2015). Control systems in an online environment often are incomplete and quickly can become outdated as technology changes, making the detection of fraud difficult (Nikitkov and Bay 2008; Nikitkov et al. 2014). Thus, the Internet enables potential fraudsters to easily find and interact with victims and take advantage of scarce controls, making online consumer fraud an increasingly frequent approach for engaging in fraudulent transactions. Consequently, empirically examining online consumer fraud decisions represents a useful approach for evaluating an increasingly common problem in business and commerce. Furthermore, results from research in this area can help us answer questions about how psychological factors like the dark triad affect short-term interactive behaviors typical of those we see in online commerce. Because of these reasons, the scenarios we use in this research are set in the context of an online transaction.

Research Model

To understand how psychological characteristics affect the decision-making processes of individuals engaging in online consumer fraud, we analyze how the dark triad affects perceptions of the motivation, opportunity, capability, and rationalization of potential fraudsters. Our key premise is that the motivation, capabilities, opportunity, and rationalization an individual perceives when evaluating whether to use technology to engage in online consumer fraud are affected by their psychological characteristics. We posit that individuals who score higher on the dark triad of personality traits are more likely to perceive that they have a greater opportunity, increased capabilities, and more motivation to engage in online consumer fraud. Furthermore, we also expect that such a person would be more likely to rationalize and enact fraud behaviors.

We propose a research model that posits that the individual elements within the dark triad differentially affect the cognitive processes of fraud. Our model is based on the idea of fraud as a planned behavior whereby an individual considers the possible outcomes, both beneficial and unfavorable, before deciding whether to commit an act of fraud. This perspective is consistent with a model of ethical decision-making where moral awareness is an antecedent to moral judgment, which must occur before the development of intention and, ultimately, action (Rest 1994; Reynolds 2006). Rest’s original model was articulated with cognitive co-occurrence of each of the components (Rest 1986); however, subsequent work has indicated that a causal order exists in the moral development process (Rest et al. 1999). In this model, there are four critical components to moral decision-making: awareness of a moral problem, developing a justification for action, establishing the intention to act, and enactment of a moral action. We posit that interactionist situational factors used to evaluate ethical outcomes are contained within the elements of the fraud triangle. We further posit that a person’s psychological predisposition affects their behavioral decision-making. Consequently, we believe that the dark triad has an effect on the elements of the fraud triangle, as shown at a conceptual level in Fig. 1.

The dark triad and the fraud triangle each contain related, but distinct, elements (Paulhus and Williams 2002; Albrecht et al. 2012). The elements in the fraud triangle have been shown to have some important causal relationships (Cohen et al. 2010; Rodgers et al. 2014). In our proposed model, each of the elements of the dark triad has a different effect on the elements in the fraud triangle. These relationships reflect the idea that different psychological predispositions affect different parts of the decision-making processes. We have developed hypotheses to describe how the individual elements in the dark triad affect each of the elements in the fraud triangle. In this study, we seek to understand how intentions about fraudulent actions are developed, so our study is framed in the context of online consumer fraud. Consequently, our model presents the decision to engage in online consumer fraud as a casual process whereby the individual effects of each of the elements of the dark triad are evident and distinct. An improved understanding of how the psychology of an individual would affect decision-making in the context of fraud represents a potentially important step in developing methods and controls for mitigating fraud.

First, we consider the influence of narcissism. Although inwardly insecure, narcissists routinely overvalue their own contributions and abilities when describing them to others (Kernburg 1975; Ames and Kammrath 2004; Gosling et al. 1998). Narcissists exaggerate their own abilities and try to portray themselves as being more important than they really are (Morf and Rhodewalt 2001). Even within the context of private self-evaluations, narcissist evaluations are quite exaggerated. In fact, John and Robins (1994) found that of those people whose self-evaluations were the most unrealistically positive, tended to be higher in narcissism. This exaggerated self-view suggests that the unrealistically positive self-views may reflect a maladaptive self-regulatory style, because narcissistic tendencies are indicative of a long-term pattern of psychological distress and dysfunction (Robins and Beer 2001). Consequently, narcissism will be positively related to perceptions of capabilities to commit fraud.

Hypothesis 1A

Narcissism will be positively related to an individual’s perceptions of their capabilities to commit an act of fraud.

One of the key non-monetary motivators of fraud is ego (Albrecht et al. 2012; Dorminey et al. 2012). In general, narcissists desire to be portrayed as superior to others (Ames and Kammrath 2004). Aspects of narcissism include entitlement and self-absorption (Emmons 1987) and narcissists are interpersonally exploitative and socially inconsiderate (Millon 1990). Thus, narcissists are likely to engage in behaviors that get them what they think they are entitled to. Narcissists think they are owed more than others and will engage in behaviors, ethical or not, to accomplish this (Rijsesbilt and Commandeur 2013). In fact, when narcissists do not get what they feel they are entitled to, they are more likely to exhibit a lack of empathy, get angry, and act amorally (Rosenthal and Pittinsky 2006). Consequently, in an effort to be perceived with a higher status, narcissists will be more motivated to commit an act of fraud. As a result, we expect a positive relationship between narcissism and motivation as suggested below:

Hypothesis 1B

Narcissism will be positively related to an individual’s motivation to commit an act of fraud.

Similar to narcissists, individuals with high levels of Machiavellianism can be good communicators and leaders (Deluga 2001). However, individuals with high levels of Machiavellianism have a strong distrust of others, which often manifests in paranoia and cynicism (Christie and Geis 1970; Dahling et al. 2009). While individuals with Machiavellianistic impulses may appear to be charismatic, they are skeptical of the intentions of others and are very cynical of other individuals (O’Boyle et al. 2012). Although most research on Machiavellianism suggests that high Machs seek opportunities to lie, cheat, and steal (Christie and Geis 1970), that expectation needs qualification (Cooper and Peterson 1980). Machiavellianism is composed of four dimensions: amorality, desire for control, desire for status, and distrust of others (Dahling et al. 2009). Of these sub-dimensions of Machiavellianism, we expect that the distrust of others has the most germane role when assessing opportunities to engage in fraud. Because high Machs are aware of those around them and are suspect of their intentions, they are wary to commit acts of fraud due to their skepticism of others’ intentions (Bogart et al. 1970). Paranoia, and a lack of trust in others, will often make high Machs hesitant to engage in unethical activities that others may witness (Christoffersen and Stamp 1995). For example, Cooper and Peterson (1980) found that when working with others, high Machs were much less likely to cheat than low Machs, the opposite occurred when working in isolation. As a result, individuals with high levels of Machiavellianism may be more willing to engage in an act of fraud, but will distrust individuals around them and will be more skeptical of opportunities available to them. That is, when high Machs perceive the risk of getting caught as high, then they will likely pass on the opportunity (Harrell and Hartnagel 1976).

Hypothesis 2A

Machiavellianism will be negatively related to an individual’s perceptions of an opportunity to commit an act of fraud.

Individuals with high levels of Machiavellianism believe that manipulation is a valid and useful mechanism for accomplishing their goals, and they often take pleasure in their ability to manipulate others (O’Boyle et al. 2012). Falbo (1977) found that high Machs use deceitful strategies and manipulate facial expressions, emotions, and dialogue to get others to do what they want. Individuals exhibiting Machiavellianism are compelled to get what they desire through any means, including cheating, lying, and stealing (Fehr et al. 1992; Jones and Paulhus 2009). Moreover, individuals with high levels of Machiavellianism desire control of others and the status that they associate with being in control of others (Dahling et al. 2009). For example, Hegarty and Sims (1978) found that Machiavellianism is related to the willingness to pay illegal kickbacks, while Ross and Robertson (2000) found that Machiavellianism is positively related to a salesperson’s willingness to lie. Furthermore, as the principal motivation of opportunism is to maximize personal interest (Williamson 1985), and Machiavellianism embraces economic opportunism (Hegarty and Sims 1978), there exists an association between Machiavellianism and motivations for economic profit. McHoskey (1999) found that high Machs have a control-oriented motivational orientation that is manifested in aspirations for financial success. These aspirations motivate high Machs to engage in behaviors and activities that promote their self-interest, regardless of the ethical nature of their acts. Consequently, these individuals also will be more strongly motivated by both monetary and non-monetary rewards, like ego and prestige, for committing an act of fraud.

Hypothesis 2B

Machiavellianism will be positively related to an individual’s motivation to commit an act of fraud.

Lastly, we consider psychopathy. The psychopathy trait is associated with a willingness to exploit others (Hare 1991). Psychopaths are comfortable dominating others and have no sensitivity for the feelings of people they hurt (Lee and Ashton 2005). Common behaviors among subclinical psychopaths are patterns of destructive, unethical, immoral, or even illegal behaviors coupled with superficial apologies (if any) that fail to convey any sense of remorse or regret (LeBreton et al. 2006). Extant research suggests that there may be differences between how “normal” individuals are pressured into rationalizing fraud and how psychopathic and criminal individuals seek out and rationalize predatory opportunities (Ramamoorti 2008; Dorminey et al. 2012). A disregard for societal norms and anti-social behavior are consistent attitudes exhibited by psychopaths (O’Boyle et al. 2012). Psychopaths believe they are above the social, moral, ethical, and legal principals in which our society governs (LeBreton et al. 2006). They rarely experience shame, guilt, remorse, or regret (Cleckley 1976; Gustafson 1999, 2000; Hare 1999; Williams and Paulhus 2004).

Furthermore, secondary psychopathy is associated with making impulsive, short-term, decisions. Decisions made for short-term benefits where individuals do not consider future effects have been linked to unethical judgment (Hershfield et al. 2012). Psychopaths are not concerned with the impact their behavior has on the emotional, financial, physical, social, or professional well-being of others (LeBreton et al. 2006). The careless and destructive ways they treat others are viewed as perfectly acceptable and appropriate. Their impulsivity has a largely narcissistic tone: they act because they “want to”. Although they prefer to describe their lifestyles as spontaneous, unstructured, and free-spirited, their behavior is often hasty and reckless and triggered by a whim with the sole purpose of immediate egocentric gratification (Cleckley 1976; Hare 1999). Accordingly, those rated higher on psychopathy exhibit more amoral and anti-social behaviors. Therefore, we expect that those individual who are rated with greater psychopathic characteristics will be more likely to rationalize acts of fraud.

Hypothesis 3

Psychopathy will be positively related to an individual’s willingness to rationalize an act of fraud.

Research on how an individual’s perceptions of their abilities to successfully complete some task is robust across social science. An individual’s expectation or confidence that they can perform a given task successfully is often referred to as self-efficacy (Bandura 1988). Individuals with higher self-efficacy pursue more opportunities (Hill et al. 1987). Narcissists have been found to rate their intelligence higher than non-narcissists (Gabriel et al. 1994) and have higher levels of self-confidence in achieving goals (Elliot and Thrash 2001). Thus, individuals who perceive that they possess the necessary capabilities to successfully perform acts of fraud will be more persistent in their actions and will anticipate that they can be successful (Bandura 1988).

Accordingly, individuals who perceive that they have greater social, procedural, or technical skills perceive a greater opportunity to exploit their superior skills to take advantage of others. Similarly, individuals who have relevant past experiences or task-related skills perceive that they need to exert less effort to successfully engage in similar actions (Ajzen 1991; Beach and Mitchell 1978). The opportunity an individual perceives to commit fraud reflects recognition of contextual factors that make it easier to manipulate or deceive others (Albrecht et al. 1982, 2012). Thus, people who possess greater capabilities for performing an act of fraud will have an easier time executing the act and will be more willing to perform the act (Wolfe and Hermanson 2004).

Hypothesis 4A

An individual’s perceptions of their capabilities to commit fraud will be positively related to their perceptions of an opportunity to commit that act of fraud.

The utilitarian perspective on decision-making suggests that individuals will rationalize unethical behavior when it the gains outweigh the potential damage to their self-image (Bersoff 1999). Individuals who possess greater capabilities for successfully committing an act of fraud will perceive that it takes less energy to commit the act of fraud and are more likely to do so successfully (Beach and Mitchell 1978). Because they feel that they can successfully pull of the fraud, they believe that it is in their own self-interest to engage in the act (Bersoff 1999). Moreover, people who perceive less risk due to their superior personal skills will anticipate a lesser chance of their deception being detected. As a result, individuals with greater capabilities for committing an act of fraud will perceive a better trade-off between risk and reward as it pertains to the act and will be better able to rationalize their actions due to a more confident assessment of the potential outcome (Murphy and Dacin 2011; Shover and Hochstetler 2005). Consequently, individuals who have more relevant skills and anticipate better outcomes will be willing to justify their actions.

Hypothesis 4B

An individual’s perceptions of their capabilities to commit fraud will be positively related to their willingness to rationalize that act of fraud.

Opportunity represents a person’s recognition of an improved chance or reduced effort required to successfully deceive and manipulate others (Albrecht et al. 1982). Within the fraud literature, the concept of opportunity plays a central role and can take into account a number of factors such as the organizational size, culture, and individual differences (Baucus 1994). The more opportunity perceived by the fraudster, the more the individual perceives an improved chance of success to commit an act of fraud (Baucus 1994; Albrecht et al. 2012). Thus, the greater opportunity to successfully commit fraud, the more reward they would expect to garner from their dishonest actions, and the lesser the perceived costs of detection or sanctions (Dorminey et al. 2012). These perceptions sway an individual’s calculus to anticipate greater rewards and fewer costs as a result of their actions. Thus, when a particularly opportune occasion is presented an individual will be more compelled to act unethically.

Hypothesis 5A

An individual’s perceptions of an opportunity to commit an act of fraud will be positively related to their motivation to commit that act of fraud.

When opportunities are readily available, individuals will find it easier to blame their intended victims for being gullible or foolish (Ramamoorti 2008). Individuals will be more willing to rationalize an act of fraud when presented with an exceptional opportunity in a weakly controlled environment or when there is an absence of capable guardians (Murphy and Dacin 2011). The perceived opportunity to commit an act of fraud represents the opinion that likelihood of being caught is remote (Dorminey et al. 2012). When punishment is uncertain or unlikely, people are more likely to commit unethical acts (Shover and Hochstetler 2005). When opportunities for committing fraud are readily available, individuals will interpret more favorable outcomes when weighing the costs and benefits associated with the action. Consequently, individuals using a calculus based on potential outcomes will be more likely to rationalize actions where they anticipate favorable results.

Hypothesis 5B

An individual’s perceptions of an opportunity to commit an act of fraud will be positively related to their willingness to rationalize that act of fraud.

The motivation to commit fraud is generally greed, a perceived need, or for egotistical reasons (Albrecht et al. 2012; Choo and Tan 2007). The greater rewards an individual anticipates as a result of their deceptive actions, the greater the likelihood they are willing to engage in fraud (Murphy and Dacin 2011). Rationalization involves the attempt to reduce the cognitive dissonance an individual experiences when considering performing fraudulent action (Dorminey et al. 2012). Rationalization is needed to reconcile personal beliefs of what is appropriate behavior with the unethical actions one is considering (Albrecht et al. 2012). Motivations to commit fraud include perceptions and expectations of the rewards associated with a successful outcome (Schweitzer et al. 2004; Schweitzer and Gibson 2008). Thus, for individuals using ends-oriented rationalizations, a large reward can be used by individuals to justify unethical behaviors (Ramamoorti 2008).

Hypothesis 6

An individual’s motivation to commit an act of fraud will be positively related to their willingness to rationalize that act of fraud.

Before enactment, fraud is rationalized and legitimized with an individual’s personal ethics (Albrecht et al. 2007; Murphy and Dacin 2011). A person will justify their actions with some context-specific reasoning, which may include arguing that the action is a special or one-time occurrence, necessary for a greater good, does not hurt anyone, is some form of karmic justice, or some other plethora of reasons. When a person is more capable of justifying their intended actions, they will be more willing to carry out the deed. For evaluating specific behaviors, personal considerations are considered to be the central driver of behavioral intention (Ajzen 1991); therefore, we expect an individual that is more capable of rationalizing an unethical action they are considering will have a greater intention to engage in that action.

Hypothesis 7

An individual’s willingness to rationalize an act of fraud will be positively related to their intention to engage in that fraudulent action.

Intention has been identified as a strong predictor of action in a variety of scenarios including ethical decision-making (Ajzen 2001; Rest 1994; Rest et al. 1999). When individuals develop an intention to act, they often follow through and enact their intended behaviors. As displayed in Fig. 2, we expect that individuals with greater intentions will be more likely to engage in the behaviors they intend.

Hypothesis 8

An individual’s intention to engage in fraud will be positively related to their engagement in that fraudulent action.

Research Methods

Scale Development and Validation

To analyze the influence of the dark triad on online consumer fraud, we used previously validated scales that have been used to measure subclinical levels of the dark triad elements. While extant validated scales exist for measuring the dark triad elements, we could find no existing validated scales for measuring the fraud triangle constructs. Therefore, we developed and validated survey items for measuring the fraud triangle constructs. The scales for measuring the fraud triangle constructs were developed in a scale validation process that included both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses (CFA). The measurement items for the fraud triangle constructs were validated through a multi-step process that rigorously followed the procedures outlined by MacKenzie and colleagues for new scale development (MacKenzie et al. 2011). This design is summarized in Fig. 3.

First, reflective measurement items were developed from definitions of the constructs in the extant literature. We initially developed five-item, unidimensional, reflective measures of the latent fraud triangle constructs. Next, the measurement items were presented to three experts with extensive experience working with the fraud triangle in a practical or research context. Each expert shared their recommendations for improving the measurement items during an hour-long meeting. The five-item scales were revised in response to these recommendations, and then presented to 10 novices. The novices reviewed the items for 30 min each, during which they evaluated the clarity of phrasing and performed a card sort to ensure that each measurement item loaded onto the same concept. The scales with five items each exhibited high reliability and validity when presented to a preliminary audience of 294 individuals in a preliminary survey. All the scales exhibited Cronbach’s alpha values greater than 0.89 and loaded onto the correct factors during the exploratory factor analysis. However, during the qualitative assessment of the scales, many respondents indicated that the repetitive nature of reflective measures made the survey too long when combined with other measures. Upon the recommendations of the participants, the scales were shortened to three items each. Because the scales contained reflective, interchangeable measures, a decision was made to trim the scales to 3 items each to limit response fatigue associated with completion of the survey.Footnote 1 The 3 items per construct retained in the refined scales, which are displayed in Table 1, were selected for their high correlations and reliability. We used 3 items to ensure the structural model would be identified for estimation (Hair et al. 2010). Our scale validation procedure completed each of the steps recommended in Roman’s (2007) scale development process: (1) defining dimensions (2) generating new items, (3) evaluating phrasing, and (4) eliminating redundancy.

After the scales were refined to their final form, the scales were presented to a new sample of subjects and 252 responses were collected for validation. These data were used to perform exploratory and CFA. The measurement model had a χ 2 value of 80.204 with 48° of freedom, the normed χ 2 value was 1.671, the CFI was 0.985, the TLI was 0.980, the RMSEA was 0.052, and the SRMR was 0.036. These global measures of fit provided evidence the measurement model fit well (Bentler 1992; Hu and Bentler 1999; Hair et al. 2010). The scale statistics and pattern matrix from the CFA are displayed Tables 4 and 5 in Appendix, respectively. These analyses indicate that all the measurement items created for the fraud triangle elements provided evidence of high reliability and validity. The composite reliability scores (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha values were greater than 0.84 for every construct, which indicates reliability. The average variance extracted (AVE) was greater than 0.50 for every latent construct and provided evidence of convergent validity (Fornell and Larcker 1981). For each latent construct, the square root of the AVE is also larger than any correlations to other constructs, providing additional evidence of discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Consequently, the statistical assessments of these measurement items consistently indicate that the scales provide reliable and valid measurement of motivation, capabilities, opportunity, and rationalization.

After the scales were validated, a new set of data containing 303 usable responses was collected to test the hypotheses in the structural model. Using a second dataset for testing hypotheses provides improved and convergent evidence of scale validity and reduces the impact of measurement biases on results (MacKenzie et al. 2011). However, before testing the structural model, the three-item scales were re-validated using confirmatory factor analysis. The factor analyses suggested that all three datasets had the same factor structure. We used a set of nested models to test this factor equivalence structure. The grouped measurement model had a χ 2 value of 200.231 with 144° of freedom, the normed χ 2 value was 1.391, the CFI was 0.993, the TLI was 0.991, the RMSEA was 0.021, and the SRMR was 0.030. Thus, the model fit well and provided evidence of factor structure equivalence (Bollen 1989; Hair et al. 2006). The model also showed evidence of factor loading equivalence (Hair et al. 2006; Marsh 1994). When the factor loadings across the three datasets were constrained to be equal to one another, a χ 2 difference test found no significant difference in the fit of the factor structure equivalence and factor loading equivalence models (∆χ 2 = 23.184 (16), p = 0.109). As shown in Table 2, the scales for measuring fraud triangle constructs consistently exhibited evidence of reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity.

The scales for measuring the dark triad constructs were adopted from previously validated scales, for example, the LSRP (psychopathy), the MACH-IV (Machiavellianism), and NPI-16 (narcissism). The LSRP is based on the two-factor interpretation of the structure of the Psychopathy Checklist used to diagnose clinical psychopathy (Hare 1991). However, the LSRP is designed to measure psychopathy in the general population (Hare 1991; Levenson et al. 1995). This trait measure of psychopathy has two factors that can be approximately described as morality (i.e., primary psychopathy) and impulsiveness (i.e., secondary psychopathy). We measured primary and secondary psychopathy with three measurement items each. These items were used verbatim from the NPI-16 and psychopathy was specified as a higher order reflective construct in our model.

The Machiavellian Personality Scale (MPS) is a validated tool to measure the construct Machiavellianism (Dahling et al. 2009). The MPS consists of a set of reflective measurement items that were derived from the previously developed and widely used Mach-IV scale (Christie and Geis 1970). Amorality, desire for control, desire for status, and distrust of others are considered to be sub-dimensions of Machiavellianism within the MPS. We measured each of the four Machiavellianism subscales with three measurement items taken verbatim from the MPS and configured Machiavellianism as a higher order reflective construct.

The NPI-16 is a revised, forced choice instrument, used to measure narcissism in non-clinical populations (Raskin and Hall 1981; Ames et al. 2006). Similar to previous findings, we found a strong correlation between Machiavellianism and psychopathy. This is not surprising because both Machiavellianism and psychopathy include items measuring morality. The LRSP, MACH-IV, and NPI-16 generally exhibited evidence of construct validity, but as multi-dimensional constructs, these measures did not provide as statistically strong evidence of validity as the measures created for the fraud constructs. Specifically, a high correlation between Machiavellianism and psychopathy is due to the sub-dimensions of primary psychopathy (psychopathy) and morality (Machiavellianism) having close theoretical associations. This correlation has been thoroughly detailed in previous research and is expected when measuring the dark triad (Hare 1991; Paulhus and Williams 2002; Jonason and Webster 2010; Paulhus 2014; Maples et al. 2014). The dark triad traits share some similarities, including self-promotion, lack of empathy, duplicity, and aggressiveness causing significant correlations during measurement (Fehr et al. 1992; McHoskey et al. 1998). However, psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism remain distinct psychological concepts (Paulhus and Williams 2002; Maples et al. 2014).

To empirically test the dimensionality of the dark triad constructs, we followed the approach recommended by Wolfinbarger and Gilly (2003) and Roman (2007). In this procedure, a series of CFA are compared to determine which of a series of alternate models best fits the observed factor structure. The previously validated scales used in our analyses presented Machiavellianism and psychopathy as higher order reflective constructs, and measured Narcissism using a 16-item aggregated measure. These assessments tested whether the higher level factor structure proposed to segment the sub-dimensions of Machiavellianism (i.e., amorality, desire for control, desire for status, and distrust of others) and psychopathy (i.e., morality and impulsiveness) is necessary. Additionally, we tested whether the high correlations and conceptual overlap (e.g., morality) between Machiavellianism and psychopathy justified merging the two constructs together. These tests were performed using four alternative models which presented: (1) a lower order factor structure with all of the measurement items loading onto a single higher order construct (i.e., the dark triad), (2) a lower order factor structure with each of the measurement items loading directly to Machiavellianism and psychopathy, (3) a higher order factor structure with the measurement items loading into sub-dimensions associated with Machiavellianism and psychopathy with the sub-dimensions merged into a single construct, and (4) a higher order factor structure with the measurement items loading into the sub-dimensions associated with Machiavellianism and psychopathy. As displayed Table 6 in Appendix, our findings indicated that the higher order factor models fit significantly better than models that did not account for sub-dimensions of psychopathy or Machiavellianism. Also, the analyses indicated that a model specifying the dark triad constructs as three distinct constructs fits the data best. Our findings are empirically consistent with extant theory about the dimensionality and validity of these widely used instruments, and we consider the dark triad scales as valid for our research (Ames et al. 2006; Christie and Geis 1970; Levenson et al. 1995; Raskin and Hall 1981).

Study 1-Survey Responses

To use the validated instruments, we applied a scenario-based approach that has been effectively used as a means to elicit responses that realistically capture attitudes and perspectives about ethical behaviors that would otherwise be prone to reporting biases (Reynolds 2006; Furner and George 2012). This scenario-based approach is consistent with extant research methods for understanding unethical decision-making while minimizing response biases (Banerjee et al. 1998; Sarker et al. 2010; Street and Street 2006). The data were gathered using a survey that was e-mailed to undergraduate students in a junior-level business course at a large Midwestern university. Fraud activities taking place in online environments typically feature young, educated individuals with little official corporate experience (KPMG 2013). College-age students have experience with Internet communications (Palfrey and Gasser 2013), engage in e-commerce (Skinner and Fream 1997), and participate in online criminal activity (Tade and Aliyu 2011). Thus, college students represent an appropriate sample for this study because individuals in this demographic commonly engage in the type of peer-to-peer online commerce and behaviors described in our scenarios.

The participants in the study were presented with a scenario that depicted a common form of interpersonal fraud, the misrepresentation of an asset (see Table 1). Subjects were presented a scenario describing an online transaction where they could gain $100 by misrepresenting the condition of a tablet computer they were selling. This scenario was selected because it contained the defining elements of a misrepresentation of goods, and represents the most common form of online consumer fraud (IC3 2015). This form of online consumer fraud contains an intentional misrepresentation of assets for material gain (Grazioli and Jarvenpaa 2000; Albrecht et al. 2012). The amount of money was held constant in the vignettes to ensure that any differences in the respondents’ interpretations of utility and harm would be the result of personal disposition and attitudes. The respondents were asked to read the scenario about selling a tablet computer before being presented with survey questions that asked them about their attitudes and beliefs related to dark triad characteristics and their opinions about misrepresenting the sale of the tablet computer. Of the 327 surveys that were started, 303 (92.6%) were completed and used for the analysis. All respondents in this group indicated that they had participated in e-commerce prior to the survey and were familiar with the context of the scenarios.

Analysis for Study 1

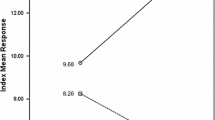

We analyzed the model fit statistics to validate the structure of the proposed model and tested the hypotheses using a covariance-based structural equation model in AMOS. Maximum-likelihood estimation was used to estimate the parameters in the model. The model used the survey responses as reflective measures of latent constructs. The structural model has a χ 2 value of 920.541 with 505° of freedom. The normed χ 2 value is 1.823, which is well below the recommended value of 3.000 (Hair et al. 2010), and provides evidence of good fit. The CFI is 0.950, meeting conventional recommendations of good fit (Bentler 1992; Hu and Bentler 1999). The NNFI/TLI is 0.944 and similarly indicates moderate-to-good fit. The RMSEA is 0.052, indicating moderate-to-good fit (MacCallum et al. 1996; Hu and Bentler 1999). The SRMR is 0.082, indicating moderate fit (Hu and Bentler 1999). Consequently, the preponderance of evidence supported the relationships proposed in the model and indicates that the data fit the model well. After finding evidence that the structural model fits the data well, the hypotheses describing the effects of the dark triad personality characteristics on fraud behaviors were tested for significance. As shown in Fig. 4, all of the hypothesized relationships tested in this model except for Hypothesis H1A and H5B are supported.

Hypothesis 1A predicts that narcissism will be positively related to an individual’s perceptions of their capabilities to commit an act of fraud. The regression weight from narcissism to perceived capabilities (−0.086) is significant (p < 0.001) but does not support Hypothesis 1A. While narcissism had a statistically significant effect, the effect is in the opposite direction to what we had hypothesized and, therefore, the results contradict Hypothesis 1A. Hypothesis 1B predicts that narcissism will be positively related to an individual’s motivation to commit an act of fraud. The regression weight from narcissism to motivation (0.066) is significant (p = 0.012), supporting Hypothesis 1B.

Hypothesis 2A predicts that Machiavellianism will be negatively related to an individual’s perceptions of an opportunity to commit an act of fraud. The regression weight from Machiavellianism to perceived opportunity (−0.172) is significant (p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 2A. Hypothesis 2B predicts that Machiavellianism will be positively related to an individual’s motivation to commit an act of fraud. The regression weight from Machiavellianism to motivation (0.228) is significant (p = 0.005), supporting Hypothesis 2B. Hypothesis 3 predicts that psychopathy will be positively related to an individual’s willingness to rationalize an act of fraud. The regression weight from psychopathy to willingness to rationalize (1.019) is significant (p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 4A predicts that an individual’s perceptions of their capabilities to commit fraud will be positively related to their perceptions of an opportunity to commit that act of fraud. The regression weight from perceived capabilities to perceived opportunity (0.290) is significant (p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 4A. Hypothesis 4B predicts that an individual’s perceptions of their capabilities to commit fraud will be positively related to their willingness to rationalize that act of fraud. The regression weight from perceived capabilities to willingness to rationalize (0.156) is significant (p = 0.005), supporting Hypothesis 4B. Hypothesis 5A predicts that an individual’s perceptions of an opportunity to commit an act of fraud will be positively related to their motivation to commit that act of fraud. The regression weight from perceived opportunity to motivation (0.233) is significant (p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 5A. Hypothesis 5B predicts that an individual’s perceptions of an opportunity to commit an act of fraud will be positively related to their willingness to rationalize that act of fraud. The regression weight from perceived opportunity to willingness to rationalize (−0.026) is not significant (p = 0.745), which does not support Hypothesis 5B.

Hypothesis 6 predicts that an individual’s motivation to commit an act of fraud will be positively related to their willingness to rationalize that act of fraud. The regression weight from motivation to willingness to rationalize (0.129) is significant (p = 0.015), supporting Hypothesis 6. Lastly, Hypothesis 7 predicts that an individual’s willingness to rationalize an act of fraud will be positively related to their intention to engage in that fraudulent action. The regression weight from rationalization to intention (0.746) is significant (p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 7.

After testing the hypotheses, we tested the substantive effects on the dependent variables. The R-squared value for capabilities was 0.041 and the accompanying effect size of 0.202 is considered small (Cohen 1988). The R-squared values for opportunity and motivation were 0.201 and 0.104. The accompanying correlation effect sizes of 0.448 and 0.322 are considered to represent a medium-sized effect. The R-squared values for the final two endogenous latent variables in the model, rationalization and fraudulent intention, were 0.512 and 0.513, respectively. Each of these represents a large amount of variance in the endogenous variable that can be described by the model.

We included three control variables when analyzing the model’s effects on rationalization and intention. We included dichotomous variables for the sex of the subject, their previous use of the technology to sell goods, and their experience with Internet fraud. The respondent’s sex (p = 0.596), having previously been defrauded (p = 0.424), and having experience selling goods using technology-mediated communication (p = 0.955) are not significantly related to rationalization. Likewise, the respondent’s sex (p = 0.786), having previously been defrauded (p = 0.983), and having experience selling goods using technology-mediated communication (p = 0.221) also are not significantly related to intention. None of the control variables had a significant effect on fraudulent intention. Consequently, none of the control variables substantively changed the interpretations of significance of any paths or altered the R-squared values associated with the dependent variables. Thus, the interpretation of the model is consistent whether the control variables are included or excluded.

Finally, to test for common method bias, we used Harman’s single-factor test, where an unrotated factor solution is checked to see how much variance is explained by a single factor (Podsakoff et al. 2012). In this case, 29.3% of the variance is explained by the single factor, which is considerably less than the recommended cutoff of 50.0% indicating that common method bias is not a problem. Because Harman’s single-factor test is regarded as a less-stringent measure of common method bias, we also used a correlation-based marker variable analysis (Lindell and Whitney 2001; Podsakoff et al. 2012). We used information transmission as a reliable construct that is unrelated to the variables of interest, identified an estimate of method bias for the correlations between variables, and then created bias-controlled disattenuated partial correlations. All of the partial correlations remained at the same significance levels following the adjustment to control for method bias. This suggests that common method bias did not have a substantive effect on the model results and key criterion remained statistically significant when common method variance is controlled for (Lindell and Whitney 2001).

Study 2-Experimental Research Data

We created an experiment to test if the model validated in Study 1 could be extended beyond intentions to predict fraud behaviors. While intentions have been closely linked to actual behaviors in a variety of contexts (Ajzen 1988, 1991, 2001; Bagozzi 1992; Tett and Meyer 1993), measures of agreement are most appropriate for measuring psychological factors and not actual behaviors. We employed an experimental design with observable behavioral outcomes drawn from Facebook advertisements that participants created. Facebook advertisements are a popular context for online consumer transactions, and represent a potential venue for online consumer fraud. For consistency with the first study and because college students represent an appropriate sample for studying the misrepresentation in these conditions, the data were again gathered from undergraduate students in a junior-level business course at a large Midwestern university.

We conducted Study 2 in two phases, Phase 1 and Phase 2, which occurred approximately 1 week apart. Of the 367 respondents that participated in the study, 343 (93.5%) participated in both batches of the study, and 329 responses (95.9%) were completed and used for the analysis. All respondents in this group indicated that they had participated in e-commerce prior to the survey and were familiar with the context of the scenarios. Using two phases in the experimental design allowed us to separate the subject’s honest estimate of the product’s value from the value they would later assign to the product when they created an advertisement to sell that product online.

The first batch of data collected in Phase 1 consisted of psychological and demographic data, including measures of the dark triad. During Phase 1, participants were presented with a used 4G iPhone and were asked to estimate its true value. We selected an iPhone for use in the study for consistency with the first study (e.g., online misrepresentation of electronic devices) and because the device would have familiarity and relevance to the study participants. To reduce the potential for participants to remember the value they estimated for the iPhone during Phase 2, participants were also asked to provide estimates of the values of other items’ in Phase 1. Six items were presented to participants including included laptop computers, desktop computers, tablet computers, digital cameras, DVD players, and smart phones.

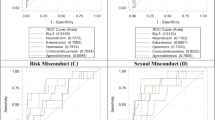

Phase 2 of the experiment took place about a week after Phase 1. The same participants were presented the exact same 4G iPhone that they assigned a value to in Phase 1 and were told that they would be creating a profile to sell the phone in a Facebook classified advertisement. Then, the participants were presented the same scales used for measuring the dark triad and fraud triangle used during Study 1, and were asked to create an advertisement to sell the iPhone. We collected the sale price and condition listed in the advertisements the respondents created. These data, when compared to their previous estimates of the true value of the iPhone, allowed us to calculate the amount of misrepresentation within the advertisements the respondents created. This attempt to illicitly profit from the intentional misrepresentation of a material good represents a common form of online consumer fraud (IC3 2015). An example of an advertisement created by a participant in the study is shown in Fig. 5. In this study, we conceptualized an observed dependent variable to evaluate actual fraud behaviors based on the amount of deception represented in the advertisement that each respondent created. To evaluate deceptive action, we observed the degree to which the respondent misrepresented the iPhone to appear to be in a better condition than they had rated it to be in Phase 1. Thus, our conceptualization of action in this context contains the necessary elements to constitute a fraudulent action: (1) an intentional misrepresentation and (2) a willingness to profit from dishonest actions (Grazioli and Jarvenpaa 2000; Albrecht et al. 2012).

First, the standard description ratings for Facebook classified ads (i.e., “Like New”, “Excellent”, “Good”, “Used” and “Fair”) were collected for each of the items and used as a second measure of intentional misrepresentation. Because all participants were presented the exact same used iPhone to sell, any description rating better than “used” or “fair” was an intentional misrepresentation of the condition of the iPhone. The iPhone presented to respondents was visibly worn and had slight damage in the form of scratches. The better the condition listed in the advertisement, the further the description deviated from the true condition of the phone. The measure of the price difference between the estimate and advertisement, and the degree to which the condition of the iPhone was misrepresented were combined into a variable in the model.

In addition, the difference between the price posted in the subject’s advertisement in Phase 2 and the value the respondent estimated for the item during Phase 1 was an indication of the over-valuation of the item within the advertisement. For example, if a participant had estimated the iPhone to be worth $200, but then attempted to sell it in the advertisement for $250, the participant over-valued the item by $50. This type of intentional misrepresentation of value is one of the most common forms of online consumer fraud (IC3 2015) and represents a signal that an individual is willing to profit from deception. Consequently, the measure of misrepresentation used in this study reflected two critical facets of online consumer fraud: (1) the willingness to misrepresent the condition of the item being sold online and (2) the attempt to profit from that misrepresentation. These facets represent necessary dimensions of fraud that are consistent in all contexts and jurisdictions (Albrecht et al. 2012).

Analysis for Study 2

As was done in Study 1, the analysis of the data for Study 2 was performed using a covariance-based structural equation model in AMOS that used maximum-likelihood estimation. The structural model has a χ 2 value of 921.187 with 574° of freedom. The normed χ 2 value is 1.605, which is well below the recommended value of 3.000 (Hair et al. 2010), and provides evidence of good fit. The CFI is 0.944 and the NNFI/TLI is 0.938, which both meet levels indicating moderate-to-good fit (Bentler 1992; MacCallum et al. 1996; Hu and Bentler 1999). The RMSEA is 0.043, indicating good fit (Hu and Bentler 1999). The SRMR is 0.080, indicating good fit (Hu and Bentler 1999). Consequently, the preponderance of evidence supports the relationships proposed in the model and indicates that the data fit the model well. Next, we tested the hypotheses describing the effects of the dark triad personality characteristics on fraud behaviors. The results of the experiment’s hypothesis tests are displayed in Fig. 6. The findings from the experiment in Study 2 directly support the findings from the survey performed in Study 1 with the exception that the relationship between narcissism and motivation was not significant in Study 2. The results indicate additional support for the following relationships: narcissism increases perceived capabilities (H1A), Machiavellianism decreases perceived opportunity (H2A) and increases motivation (H2B), and psychopathy increases willingness to rationalize fraud (H3). Additionally, there is evidence that perceived capabilities increase perceived opportunity (H4A) and that perceived opportunity increases motivation (H5A). Likewise, there is evidence that perceived capabilities (H4B) and motivation (H6) increase willingness to rationalize fraud. Finally, the data indicate that willingness to rationalize fraud increases intention (H7) and intention increases action (H8). As in Study 1, our findings did not indicate that narcissism affects motivation (H1B) or that perceived opportunity (H5B) affects willingness to rationalize fraud.

To validate our findings that each of the dark triad traits consistently had a differential effect on a different component of the fraud triangle, we tested a model with a fully saturated set of factor estimates from each of the dark triad elements to each of the fraud triangle elements. These tests used an atheoretical model, where each of the dark triad elements is tested as a potential antecedent of each of the fraud triangle elements. The standardized parameter estimates and hypotheses tests for these effects are shown Table 7 in Appendix. These tests support our other findings and imply that Machiavellianism also may affect perceptions of capabilities. There is not sufficient evidence of any other significant causal relationships besides the ones described above between the dark triad elements to the fraud triangle factors. These findings, when considered in conjunction with the similar results of Study 1 and Study 2 (as shown in Table 3), indicate support for the notion that each element in the dark triad affects a different part of the fraud decision-making process.

Finally, the control variables included in the model did not significantly affect these findings and there were no indications that common method bias significantly influences these results. The control variables for the sex of the subject (p = 0.900) and their experience with Internet fraud had no significant effect on the outcome (p = 0.370). An unrotated factor solution explained 27.1% of the variance by the single factor, which is less than the recommended cutoff of 50.0% and indicates that common method bias is not a problem.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that the dark triad does affect fraud behaviors but, importantly, the results strongly demonstrate that each dark triad element affects different factors involved in fraudulent decision-making (i.e., the factors in the fraud triangle model). Our research contradicts other research in fraud detection that recommends focusing almost solely on the role of opportunity in staving off fraud (Stone 2015). This is because we show that a focus on opportunity alone will not be equally as effective among individuals with differing psychological traits. The analysis indicates that each of the psychological factors in the dark triad differentially affects parts of the fraud triangle, and that the effects of psychopathy and Machiavellianism have a stronger influence on fraud intentions than does narcissism. The effects of narcissism on perceptions of motivation and capabilities were significant, albeit not substantive. In contrast, the effects of Machiavellianism on opportunity and motivation and the effects of psychopathy on rationalization are both significant and substantive. These disparate effects of the three dark triad personality characteristics have important ramifications because individuals with a combination of higher scores on psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism possess a special collection of undesirable psychological traits that stimulate every phase in the cognitive process of fraud. This finding also indicates that different deterrence mechanisms will have differential impacts on individuals based on their psychological predispositions.

Theoretical Contribution and Practical Implications

Narcissism, which is largely defined by internal insecurities and grandiose goals and displays (Kernburg 1975), has an effect on perceptions of capabilities and motivation (Johnson et al. 2012). Our findings support previous research that indicates narcissism is positively correlated with the motivation to commit fraud. However, it is interesting and unexpected to find that narcissism has an inverse relationship with capabilities. We speculate that the internal insecurities of a narcissist manifest in their perceptions of their capabilities for committing a successful act of fraud. Thus, while narcissists tend to outwardly display egotistical behaviors, their perception of an opportunity to successfully engage in an act of fraud is driven by their personal insecurities. In the context of fraud decisions, narcissism has the least substantive effects of the dark triad personality characteristics.

Extant theory about narcissism suggests that weak effect sizes may be due to the contrasting nature of the internal and external manifestations of narcissism as they pertain to fraud situations. For example, narcissists want to look outwardly capable, while in actuality being deeply insecure about their own abilities (Paulhus 1998). Similarly, narcissists not only want the power and prestige associated with the accumulation of wealth and power, but also fear the social ramifications of detection. Historically, many fraudsters who exhibited narcissism and had been convicted of fraud actually refused to acknowledge that their acts constituted a criminal misrepresentation (Ramamoorti 2008; Albrecht et al. 2012). However, in these instances, even a small but statistically significant effect size is useful to both theory and practice, because the manipulation of these effects can ultimately lead to a reduction in fraud. Fraud has dire ramifications for victims, which warrant the development of measures to create even small reductions in the likelihood of fraud’s occurrence. Our evidence suggests that narcissistic individuals may doubt their ability to successfully engage in fraud, but will covet the rewards of fraudulent action more than will those who are less narcissistic.