Abstract

Proactive corporate social responsibility (CSR) involves business practices adopted voluntarily by firms that go beyond regulatory requirements in order to actively support sustainable economic, social and environmental development, and thereby contribute broadly and positively to society. This empirical study examines the role of the economic, social and environmental dimensions of proactive CSR on the association between three specific capabilities—shared vision, stakeholder management and strategic proactivity—and financial performance in small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Using quantitative data collected from a sample of 171 Australian SMEs in the machinery and equipment manufacturing sector and employing structural equation modelling, we find that the adoption of practices in each CSR dimension by SMEs is influenced slightly differently by each capability, and affects financial performance differentially. The study also demonstrates the importance of the interaction between the three dimensions of proactive CSR in positively moderating the deployment of each individual CSR dimension to generate financial performance. Paying primary attention to the economic dimension of proactive CSR and selectively focusing on social and environmental elements of proactive CSR that drive and support the economic dimension are of key importance to sustainable long-term financial success for SMEs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In today’s business environment, business has come under increasing pressure to engage in practices described as corporate social responsibility (CSR). Whilst many of such practices are driven by regulatory compliance, business is encouraged to go beyond this and take a more active role in meeting societal needs. CSR and ‘sustainable development’ are two of many terms used to discuss the economic, social and environmental contributions and consequences of business practices. In this study, we have drawn on the notion of CSR (also called ‘responsible entrepreneurship’) produced by the European Commission (European Commission 2003, pp. 5–7) to define CSR as responsible business practices that support the three principles of sustainable development: economic growth and prosperity, social cohesion and equity and environmental integrity and protection. Embedding the three (economic, social and environmental) principles of sustainable development into CSR provides an alternative business model to the traditional growth and profit-maximisation model (Jenkins 2009).

Drawing on the long-established ‘reaction–defence–accommodation–proaction’ typology (Carroll 1979; Wartick and Cochran 1985; Wilson 1975), firms can be viewed as operating along a continuum of CSR ranging from reactive to proactive in nature. The assumption underpinning this continuum is that every firm has a social responsibility and that it is the degree and kind of CSR practices a firm uses to meet that responsibility which will vary (Carroll 1979; Wartick and Cochran 1985). In contrast to reactive CSR which aims at expending only the minimum level of effort required for non-voluntary regulatory compliance, proactive CSR relates to active and voluntary practices in which a firm engages, above and beyond regulatory requirements, in order to manage social responsibility issues as a competitive priority (Carroll 1979; Du et al. 2007; Groza et al. 2011; Wilson 1975). Proactive CSR embraces the design and development of sustainable products, operations and production processes that anticipate the projected evolution of external regulation and social trends (Groza et al. 2011; Wilson 1975). Engagement in proactive CSR is advocated by strategy scholars as a value-creating action from which a competitive advantage can be derived (Benn et al. 2006; Berry and Rondinelli 1998; Klassen and Whybark 1999; Sharma and Vredenburg 1998).

An increasing amount of research has used the resource-based view (RBV) of the firm (Barney 1991; Grant 1991) to understand how, and with what impact, proactive CSR can contribute to creating competitive advantage and superior performance (e.g. Aragon-Correa et al. 2008; Sharma and Vredenburg 1998). The RBV predicates on the idea that firms gain competitive advantage by implementing value-creating strategies derived not only from the acquisition of unique and heterogeneous resources but also from their ability to integrate and deploy those resources as the basis for core organisational ‘capabilities’ (Amit and Schoemaker 1993; Barney 1991; Grant 1991; Wernerfelt 1984). Much of research on proactive CSR has been done in the context of large enterprises; so far little attention has been given to the challenge that the adoption of such practices poses for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) (Aragon-Correa et al. 2008). It is conventionally assumed that business and legislative pressures produce only a reactive approach to CSR among SMEs; once compliance requirements have been satisfied, SMEs have limited or no resources with which to engage proactively in CSR; and, therefore SMEs are less likely to reap the benefits that proactive CSR offers (Gadenne et al. 2008; Palmer 2000; Russo and Fouts 1997; Rutherfoord et al. 2000; Schaper 2002; Tilley 1999). However, some empirical evidence to the contrary has been presented recently by Aragon-Correa et al. (2008), who found in a study of proactive environmental practices that SMEs can possess a set of distinctive organisational capabilities which helps overcome (slack) resource limitations and thus enables the successful adoption of practices similar to the advanced environmental practices of larger firms.

However, a lack of conclusive empirical evidence in the literature across all three dimensions of proactive CSR—economic, social and environmental—means an integrative and holistic understanding of the importance of proactive CSR to SME competitiveness remains a question of debate, as does the question of whether SMEs can develop the necessary enabling organisational capabilities for proactive CSR. This study aims to contribute to the debate by examining the role of the economic, social and environmental dimensions of proactive CSR on the association between organisational capabilities and financial performance in SMEs. Drawing on RBV theory that distinctive capabilities are critical foundations for formulating strategies (Barney 1991; Grant 1991), we consider three specific capabilities—shared vision, stakeholder management and strategic proactivity—which when leveraged by SMEs may make more likely the successful adoption of proactive CSR across all three dimensions. We focus on the importance of these capabilities in generating each dimension of proactive CSR, the influence each CSR dimension has on financial performance and the potential moderating effect the interaction between the three dimensions of proactive CSR has in enabling SMEs to make the best use of each individual CSR dimension to improve their financial performance.

Proactive CSR

In this study, proactive CSR is represented by a pattern of responsible business practices adopted voluntarily by firms that simultaneously support sustainable economic, social and environmental development at a level above that required to comply with government regulations. In what follows, each dimension of proactive CSR is discussed.

Economic Dimension of Proactive CSR

With the aim of supporting economic growth and prosperity, the economic dimension of proactive CSR is the means by which firms attempt to preempt issues (e.g. customer satisfaction, product quality and safety and supply chain management) that might arise in their interactions with customers, suppliers and stakeholders in the market place (European Commission 2003, p. 11). The way a firm operates in the market is taken as an indicator of how it has integrated action on economic responsibility concerns into its core business activities and decision-making processes. The aim of such integration is seen as going beyond short-term profit maximising issues to emphasise long-term economic performance issues, and the effective exploitation of market opportunities, as well as contribute to the improvement of the standard of living across the whole economy (e.g. Bansal 2005; Russell et al. 2007; Willard 2005). Economic-related proactive CSR creates value through fostering the development of new and different products that are desired by consumers, lowering the costs of inputs, and improving production efficiencies. However, as this CSR dimension requires effective management of several types of economic capital, firms need to adopt a long-term perspective in management and decision-making, so that at any time they can guarantee “cashflow sufficient to ensure liquidity while producing a persistent above average return to their shareholders” (Dyllick and Hockerts 2002, p. 133).

For SMEs, the owner-managed firm, where ownership and decision-making and managerial control rest with the owner–manager, is the most common form (Jenkins 2009). Research suggests that in general SME owner–managers are aware that their firms’ economic viability is crucially dependent on strong customer and supplier relationships (Hornsby et al. 1994; Lahdesmaki 2005; Vitell et al. 2000); and where this awareness is acute, economic-related proactive CSR is likely to occur. In comparison to many larger firms, those SMEs with the capacity to adapt flexibly and speedily in order to take advantage of changing market conditions and opportunities (Goffee and Scase 1995) are better positioned and equipped to benefit from new niche markets for goods and services that add value to the society. Nevertheless, research also indicates that the adoption of a long-term economic perspective often proves difficult for those SME owner–managers, whose personal style of management is primarily an adaptive process concerned with manipulating a limited amount of (financial and human) resources to gain maximum immediate financial gain and ensure economic survival at least in the short term (Beaver and Jennings 2000; Spence 1999).

Social Dimension of Proactive CSR

Having the workplace and the community as two points of focus in creating social cohesion and equity, the social dimension of proactive CSR actively recognises “the health, safety and general well-being of employees; motivate[s] the workforce by offering training and development opportunities; and enable[s] firms to act as good citizens in the local community” (European Commission 2003, p. 5). Such social-related proactive CSR also involves creating a formal social dialogue to consider social and ethical questions that recognises the interests of all stakeholders in decision making; in so doing, mutually acceptable outcomes can result for the firm and its stakeholders (Bansal 2005).

Research examining the ability of SMEs to adopt social-related proactive CSR supports contrasting views. On the one hand, some researchers argue that because the image of a SME as an employer and actor in the local scene affects its competitiveness, the general value systems which dominate social networks in its industry and value chain are therefore likely to influence a firm’s business practices; that is, norms and pressures from employees, peer firms, and the community will thus drive SMEs to actively engage routinely in socially responsible behaviours (e.g. Arbuthnot 1997; Petts et al. 1999). In such cases, the imperative is not commonly expressed in formally written codes of conduct as in large firms; rather, it is derived from informal positive relationships (with personal knowledge and family ties) that engender trust and reciprocity in network interactions between SMEs and their employees and local communities, thereby allowing issues such as workplace flexibility, democracy and diversity to be addressed cooperatively (Hammann et al. 2009; Lahdesmaki 2005; Worthington et al. 2006).

On the other hand, some researchers (e.g. Brammer and Millington 2006; Gerrans and Hutchinson 2000) argue the evidence which suggests that SMEs experience substantial difficulties in proactively developing social-related CSR because of the financial and human resource costs they face in providing training and development opportunities for employees, or supporting community involvement through charitable donations or sponsorship. The argument runs that constrained by a lack of adequate resources, some SMEs may only be able to engage actively in a limited program of social-related CSR activities, or partly conduct such activities in isolation (Lepoutre and Heene 2006).

Environmental Dimension of Proactive CSR

As suggested in the literature (e.g. Aragon-Correa 1998; Buysse and Verbeke 2003), the environmental dimension of proactive CSR focuses on innovation, eco-efficiency, pollution prevention and environmental leadership. With the aim of minimising a firm’s ecological impact along the entire product life cycle, environmental-related proactive CSR is often characterised by adoption of internationally compliant environmental management systems (or a total quality management approach) to ensure the environmental impacts from a firm’s activities are monitored and managed systematically, thereby helping build a firm’s credibility with external stakeholders and ensure the embrace of the principle of environmental integrity and protection amongst internal stakeholders (Walley and Whitehead 1994).

The majority of researchers (e.g. Rutherfoord et al. 2000; Tilley 1999) contend that SMEs face more difficulties than large enterprises in adopting environmental-related proactive CSR, given it can require significant and sometimes quite sophisticated management and integration of value chain activities beyond the ken of SMEs. For example, recycling-based programs often require the integration of multiple components (production, inbound and outbound logistics and post-sales service) in the value chain. The complexity of integrating and linking multiple value chain activities reinforces the fact that the implementation of such environmental-related CSR requires substantial resources and sophisticated management expertise (Sharma and Vredenburg 1998). Research suggests factors such as a lack of capacity for shaping environmental behaviour beyond compliance, and the potential conflict that can arise between environmental goals and production and survival pressures, mitigate against the adoption of such proactive activity in SMEs (Hooper and Gibbs 1995; Petts 2000; Tilley 1999). Evidence from a number of studies (e.g. Schaper 2002; Williamson and Lynch-Wood 2001) highlighting the poor level of environmental awareness in SMEs also supports this view.

Nevertheless, there are a small number of studies (e.g. Aragon-Correa et al. 2008; Hillary 2000) that support a contrary view; their findings show that SMEs can successfully implement engage in environmental-related proactive CSR. Bianchi and Noci (1998) also, for instance, show that SME successful adoption of such proactive activity can be feasible if the establishment of positive and stable relationships with external stakeholders (e.g. public institutions, research centres, industrial unions and government agencies) provides SME access to the high-level skills, resources and information necessary for the introduction and management of complex environmental initiatives.

Interaction between Economic, Social and Environmental Dimensions of Proactive CSR

Possible interaction between the three dimensions of proactive CSR has been identified in the literature. For example, some research (e.g. Becker-Olsen et al. 2006) suggests that a trend towards a more socially acceptable and environmentally friendly form of consumerism is driving a transition from a narrow focus on economic-related CSR towards a broader focus incorporating the social and environmental dimensions of CSR. The emergence of this trend reflects the willingness and ability of an increasing number of consumers both to pay a premium for socially and environmentally friendly products and to exert market pressure by boycotting the products of firms with a poor reputation for social and environmental responsibility (Ellen et al. 2006; Gielissen 2011; Groza et al. 2011). In addition, suppliers may stop delivering inputs to such firms to protect their own reputation (Yoon et al. 2006). All of this implies that it is less risky for a firm, who wish to obtain long-term profitability, to engage simultaneously in economic, social and environmental dimensions of proactive CSR.

Furthermore, the social and environmental dimensions of proactive CSR may be complementary, in that successfully minimising a firm’s ecological footprint depends significantly on the participation and involvement of employees in the full range of value chain activities directly controlled by firms (Hart 1995; Nehrt 1998; Ramus and Steger 2000). Social-related CSR, such as engaging employees and providing values-oriented training and employee development opportunities, can complement environmental-related CSR by building awareness of and commitment to environmental values, as well as by improving the necessary technical and managerial skills for adopting such environmental activity (Graafland et al. 2003). Moreover, firms with a reputation for environmental-related proactive CSR may also build skill and knowledge resources by attracting and retaining highly qualified employees interested in preventive environmental management (Reinhardt 1999). Complementarity may also create an impetus in the firm that drives the transition towards economic dimension of proactive CSR (Chang and Kuo 2008); properly designed socially and environmentally responsible practices can trigger innovations that lower the cost of a product and improve the value proposition it represents to consumers (Porter and van der Linde 1995).

Capabilities for Proactive CSR

Drawing on RBV theory that organisational capabilities derive from a firm’s resources (or characteristics) provide the foundation for successful strategy formulation, which in turn promotes financial performance (Barney 1991; Grant 1991; Wernerfelt 1984), we consider three specific capabilities—shared vision, stakeholder management and strategic proactivity—that are likely to be associated with the adoption of proactive CSR by SMEs. These capabilities, which have been found to underpin environmental-related proactive CSR in large firms (see Buysse and Verbeke 2003), have recently been examined by Aragon-Correa et al. (2008) in an SME context. Aragon-Correa et al. (2008) argue that SMEs can develop these capabilities based on their distinctive strategic characteristics of shorter lines of communication and closer interaction within a firm, greater flexibility and innovativeness and entrepreneurial orientation. Extending this approach, we investigate these capabilities as foundations for the three dimensions of proactive CSR in SMEs.

Shared Vision

Shared vision is a capability that embodies the collective goals and aspirations of the members of a firm (Oswald et al. 1994). Such a capability entails a common feeling that the firm’s objectives are important and that all members may contribute to defining them (Graafland et al. 2003; Tsai and Ghoshal 1998). Goal clarity and shared responsibility for achievement of the firm’s goals have been shown to affect organisational learning and employee creativity positively at the interface between the business and the sustainable responsibility principles (Ramus and Steger 2000).

Research suggests that firms which successfully develop a shared vision capability are able to accumulate and harness the resources and skills necessary for developing proactive CSR more quickly, because tacit skill development through employee involvement is inherent to the capability (Hart 1995). As indicated by SME scholars (Jenkins 2006; Worthington et al. 2006), the simple management structures and shorter lines of communication characteristic of SMEs can facilitate greater involvement by all employees thus allowing the values and culture underpinning proactive CSR to be more easily embedded across the entire firm. Acting as a bonding mechanism that facilitates fluid communication across functions and level in a firm (Tsai and Ghoshal 1998), a shared vision capability can lead an SME to economic gains in terms of improved product quality and safety, and help determine which products present social and environmental responsibility risks. However, as resource constraints and unsophisticated management may prevent some SMEs owner–managers from working effectively with and engaging employees (Merz and Sauber 1995), a shared vision capability is not intrinsic to all SMEs. We thus argue that only SMEs that are able to exploit close interaction between the owner–manager and employees to develop a shared vision capability are more likely to adopt proactive CSR across its three dimensions. Therefore, we suggest:

Hypothesis 1a

A shared vision capability is positively associated with the adoption of the economic dimension of proactive CSR by SMEs.

Hypothesis 1b

A shared vision capability is positively associated with the adoption of the social dimension of proactive CSR by SMEs.

Hypothesis 1c

A shared vision capability is positively associated with the adoption of the environmental dimension of proactive CSR by SMEs.

Stakeholder Management

Stakeholder theory (e.g. Freeman 1984; Sharma and Vredenburg 1998) construes a firm as a series of connections with stakeholders that a firm attempts to manage, and from which a competitive advantage can be achieved. Sharma and Vredenburg (1998, p. 735) define a stakeholder management capability as “the ability to establish trust-based collaborative relationships with a wide variety of stakeholders, especially those with non-economic goals”. The challenge for firms is to develop this capability with which to manage the different and sometimes conflicting goals, priorities and demands effectively (Werhane and Freeman 1999).

Research suggests that firms that recognise a wide variety of stakeholders are more likely to adopt proactive CSR than those that focus on a narrow range of stakeholders (Buysse and Verbeke 2003; Henriques and Sadorsky 1999). A broadly focused stakeholder management capability supports active collaboration with all stakeholder types through which CSR concerns might be managed and reduced (Sharma et al. 2007).

Although the literature on stakeholder management mostly offers evidence for the importance of this capability for generating proactive CSR in large firms (e.g. Buysse and Verbeke 2003; Henriques and Sadorsky 1999), there is some limited empirical evidence that it is also likely to be important for SMEs (Aragon-Correa et al. 2008; Worthington et al. 2006). Because of their more limited internal resources, SMEs are less likely to utilise media and publicity for stakeholder management purposes compared to large firms; however, SMEs are more likely to derive a stakeholder management capability from their more flexible managerial structures and greater responsiveness to business and stakeholder needs (Jenkins 2006; Jones 2003). Such characteristics enable SMEs to prioritise and focus more closely on particularly important external stakeholder relationships, a point of significance given that implementation of complex responsibility practices often requires specialised information on regulatory and social trends not generally available within a SME (Bianchi and Noci 1998). Understanding and managing stakeholder concerns via engagement in trust-based relationships can help expand an SME’s resources for undertaking the three dimensions of proactive CSR. Therefore, we suggest:

Hypothesis 2a

A stakeholder management capability is positively associated with the adoption of the economic dimension of proactive CSR by SMEs.

Hypothesis 2b

A stakeholder management capability is positively associated with the adoption of the social dimension of proactive CSR by SMEs.

Hypothesis 2c

A stakeholder management capability is positively associated with the adoption of the environmental dimension of proactive CSR by SMEs.

Strategic Proactivity

Drawing on the study of Miles and Snow (1978) indicating that strategically managed firms develop entrepreneurial, engineering and administrative processes that integrate external information and opportunities, Aragon-Correa (1998, p. 557) defines strategic proactivity as “a firm’s tendency to initiate changes in its various strategic policies rather than to react to events”. This definition is extended by Sharma et al. (2007, p. 272), who define strategic proactivity as being “embedded in a firm’s routines and processes designed to maintain a leadership position via monitoring the external environment including the competitors’ strategies in competition”.

Research conducted mostly in a large firm context shows that firms possessing a strategic proactivity capability often design internal possesses that empower individuals to actively engage in CSR-oriented innovation, which assists in establishing a competitive advantage more quickly (Aragon-Correa 1998: Starik and Rands 1995). SME-based research suggests that being entrepreneurial and seeking niche strategies in competitive markets can aid the development of a strategic proactivity capability and hence the successful implementation of proactive CSR in SMEs (Sharma et al. 2007). In particular, the characteristic creativeness and innovativeness of SMEs can enable them to forecast external opportunities and threats and be proactive in taking advantage of new niche markets for products and services that have added value in the form of economic, social and environmental benefits (Jenkins 2006). Therefore, we suggest:

Hypothesis 3a

A strategic proactivity capability is positively associated with the adoption of the economic dimension of proactive CSR by SMEs.

Hypothesis 3b

A strategic proactivity capability is positively associated with the adoption of the social dimension of proactive CSR by SMEs.

Hypothesis 3c

A strategic proactivity capability is positively associated with the adoption of the environmental dimension of proactive CSR by SMEs.

Proactive CSR and Financial Performance

Of the three CSR dimensions, the economic dimension of proactive CSR, which emphasises long-term value creation and wealth generation (European Commission 2003; Bansal 2005), should by definition form a core part of a firm’s financial performance and underpin its business and competitive advantage. However, given SME resource constraints and the need to invest significant resources to establish effective economically responsible business practices, this assumption may apply to only those that do have the requisite skills and resources to exploit and leverage such economic-related activities.

In regard to a link between the social and environmental dimensions of proactive CSR and financial performance, published empirical results are inconclusive overall. Whereas the majority of studies indicate a positive influence on financial performance for social-related CSR (e.g. Hammann et al. 2009; Hillman and Keim 2001) and for environmental-related CSR (e.g. Klassen and Whybark 1999; Russo and Fouts 1997), other studies (e.g. Wagner et al. 2002) report contradictory results. The inconclusive nature of the empirical research to date has therefore led some authors to suggest that the relationship between the social and environmental dimensions of proactive CSR and financial performance may follow an inverted U-shaped pattern, meaning that such practices may improve financial performance at first, but sooner or later engagement will represent net costs (Burke and Logsdon 1996; Schaltegger and Synnestvedt 2002). Nevertheless, many scholars, in their study of CSR in large firms, argue that such social- and environmental-related CSR can enable the firm to differentiate its products, to improve production efficiencies and to reduce its exposure to risks, thereby increasing the value of a firm’s future cash flows and assisting in maximising the wealth of the firm’s equity holders (e.g. Hart and Milstein 2003; Mackey et al. 2007; McWilliams and Siegel 2001; Shrivastava 1995).

Although the debate remains ongoing over whether a lack of resources constrains the implementation of proactive CSR in SMEs (e.g. Gadenne et al. 2008; Miles et al. 1999; Orlitzky 2001; Rutherfoord et al. 2000; Simpson et al. 2004), a growing body of empirical research suggests a positive link between proactive CSR and financial performance in SMEs. For example, Sturdivant and Ginter (1977) found that SMEs with moderate to high levels of social-related CSR outperformed those that did not. Similarly, Aragon-Correa et al. (2008) found a positive association between environmental-related proactive CSR and SME financial performance. Similarly, by proposing and testing a model that combines an SME’s entrepreneurial value orientation with socially responsible business practices, Hammann et al. (2009) found a link between such practices and favourable financial outcomes in terms of cost reduction and increase in profit. In the light of what research evidence is available regarding the impact of proactive CSR on financial performance in SMEs, it is plausible to posit that each dimension of CSR could be financially beneficial to SMEs. However, given that the economic, social and environmental dimensions of proactive CSR interrelate, they are likely to influence each other in multiple ways to produce better positive financial results. Therefore, we suggest:

Hypothesis 4a

The economic dimension of proactive CSR is positively associated with SME financial performance.

Hypothesis 4b

The social dimension of proactive CSR is positively associated with SME financial performance.

Hypothesis 4c

The environmental dimension of proactive CSR is positively associated with SME financial performance.

Hypothesis 4d

The interaction of the economic, social and environmental dimensions of proactive CSR has a positive effect on the capacity of an SME to deploy each individual CSR dimension to generate financial performance.

Research Method

We tested our research hypotheses in the Australian machinery and equipment manufacturing sector for three reasons. First, it is the largest sector in the Australian manufacturing industry in terms of gross value added and the second largest in terms of employment and export values (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS] 2009). Second, the environmental impacts of this sector are significant owning to the nature of the multiple activities and processes used to transform raw materials into finished products. As the Australian government delegated significant responsibility for the 2007 Kyoto Protocol to stabilise and limit carbon emissions and introduced a carbon pollution reduction scheme (ABS 2010), the machinery and equipment manufacturing sector has experienced increasing pressure to engage explicitly in CSR activities (see Matten and Moon 2008 for extensive discussion of explicit and implicit CSR). Finally, it is a growing industry sector experiencing new entries and high competition; therefore, firms in this sector tend to emphasise production of innovative products and their organisational structures can be expected to be flexible and less bureaucratic (Russo and Fouts 1997). For these reasons, the proactive adoption by this industry sector of policies and procedures associated with CSR across economic, social and environmental dimensions could be expected. Our sampling frame was a population of 1,388 SMEs (i.e. firms with less than 200 employees as defined by the ABS 2001) listed in a commercially available database (Dun and Bradstreet 2009).

As the focus of this study was on theory testing at the firm level of analysis, a quantitative survey-based method was employed. As no published data were available on capabilities, proactive CSR and performance for the targeted sample population, a questionnaire was developed based on the extant literature providing theoretical domains for the constructs of interest; existing published questionnaire items; and discussion with several SME owner–managers in the machinery and equipment manufacturing sector, as well as academic researchers and senior public servants familiar with CSR in this sector. A trial questionnaire was tested with SME owner–managers in three firms to ensure clarity and content validity. These trial responses were not used in the final study.

Data were collected from CEOs, managing directors and general managers who could be expected to have holistic and deep knowledge about their firm’s responsible business practices. Following the suggestion of previous research that in the case of SMEs, where decision making is often highly centralised and the views of a single experienced well-qualified informant may better capture a firm’s approach than the views of several informants (Chandler and Hanks 1993; Lyon et al. 2000), a single informant in each firm was identified for this study. Respondents were promised that analysis would be done at the aggregate level and no firm would be identified individually.

The survey was administered by mail in 2009 in April (Time 1) and November (Time 2), providing a 6-month time lag between the measurements of predictors/mediators (capabilities/all three dimensions of proactive CSR—Time 1) and dependent variable (financial performance—Time 2). This 6-month time lag was used in order to diminish a respondent’s ability and motivation to use previous responses to answer subsequent questions, as well as to allow for temporal ordering of variables. However, recognising that self-reporting methods could threaten the reliability of the constructs, all respondents were also asked to report their firm’s financial performance in Time 1 and their firm’s capabilities and proactive CSR (all dimensions) in Time 2, with the aim of testing the correlation between the same variable at the different time points. After an intensive follow-up process (via online, telephone and fax contact), 200 from a possible 1,388 responses were received, representing a 14.4 % response rate. After responses with missing data were eliminated, a total of 171 firms remained in the sample, resulting in a final response rate of 12.3 %.

All firms responding to our survey were owner-managed, and nearly 70 % of respondents were the ‘owner–managers’; 81.3 % had <50 employees, and 85.6 % had an estimated annual turnover >$1 million but <$30 million. Respondents confirmed that both the Time 1 and the Time 2 survey data were provided by the same person. To allow the respondents to make subtle distinctions in their answers, the questionnaire provided respondents with space for additional qualitative comments (via an open-ended question) relating to the difficulties their business faces in actively implementing responsible business strategies in today’s business environment. Fifty-eight respondents (34 %) provided comment in response to the question.

Given that the overall response rate was lower than might be expected (Anseel et al. 2010); the possibility of non-response bias was examined through Armstrong and Overton’s (1977) time-trend extrapolation procedure. Analysis showed no significant difference between early and late respondents in terms of their firm size, location and range of activities. Following a suggestion in the literature (e.g. MacCallum and Austin 2000; Kline 2005), a ‘power analysis’ was also conducted to ensure that the sample size had adequate power for detecting when null hypotheses were false. Estimated power was calculated at 0.7514, meaning that with a sample size of 171, if the model did not have close fit, then the probability of rejecting a model as incorrect was 75.14 %. Taken together these analyses suggested that our sampled data were valid for the targeted population and adequate for statistical analysis.

As the data were subjective assessments of single respondents, it was acknowledged that common method bias could have augmented relationships between the variables (Podsakoff et al. 2003). To test the presence of common method effect, Harman’s single-factor test (Podsakoff and Organ 1986) was conducted through both the exploratory and the confirmatory factor analyses. All of the 15 measured variables included in our measurement model were entered into an exploratory factor analysis, using unrotated principal components factor analysis to determine the number of factors that are necessary to account for the variance in the variables. The analysis revealed the presence of four distinct factors with eigenvalues >1, rather than a single factor. The four factors together accounted for 62 % of the total variance; and the largest factor did not account for a majority of the variance (28 %). Moreover, all of the 15 measured variables were loaded on one factor to examine the fit of the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model; and the results showed that the single-factor model did not fit the data well: χ² = 575.65 (p < 0.001), df = 90, RMSEA = 0.182, CFI = 0.65, IFI = 0.64, NNFI = 0.69). While the results of these analyses do not preclude the possibility of common method bias, they do suggest that the common method bias is not of great concern and thus unlikely to confound the interpretations of the results.

Measures

Proactive CSR: Economic, Social and Environmental Dimensions

Proactive CSR was measured using 27 items based on the extant literature (e.g. Aragon-Correa et al. 2008; Bansal 2005; European Commission 2003; Dyllick and Hockerts 2002; Jenkins 2006; Sharma et al. 2007) and initial discussion with pretest participants. The economic dimension of proactive CSR was measured using an eight-item scale; an eight-item scale was used to measure the social dimension; and an eleven-item scale was used to measure the environmental dimension (see Table 4 in Appendix). Respondents were asked to indicate, using a five-point scale (1 = ‘not addressed issue at all’ to 5 = ‘we are leaders on this issue’) for each of the three CSR dimensions, the extent to which their firms voluntarily engaged in CSR activity compared to similar firms in their industry sector. The use of this comparative approach enabled respondents to use an objective point of external reference for self-evaluation and helped increase the precision of the measurement results (Sharma et al. 2007). Exploratory maximum likelihood (ML) factor analysis with varimax rotation showed that the eight items of economic-related proactive CSR formed two factors with eigenvalues >1 (Cronbach’s α = 0.758 for Factor 1 and 0.716 for Factor 2); the eight items of social-related proactive CSR formed two factors (Cronbach’s α = 0. 832 for Factor 1 and 0.790 for Factor 2); and the eleven-items of environmental-related proactive CSR formed three factors (Cronbach’s α = 0.873 for Factor 1; 0.840 for Factor 2; and 0.795 for Factor 3). The factor scores of proactive CSR in each dimension for each firm were a weighted average of the relevant items calculated using the standardised loading obtained from the second-order CFA. A high score was indicative of high adoption of proactive CSR. The high correlation obtained for each CSR dimension between Time 1 and Time 2 surveys (r = 0.94, 0.92 and 0.95 for economic-, social- and environmental-related CSR, respectively) confirmed our confidence in the reliability of the scale of all the three dimensions of proactive CSR.

Shared Vision Capability

A shared vision capability was measured using three items from Aragon-Correa et al. (2008)’s validated scale. All items were presented as statements related to the firm, against each of which respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement on a six-point scale (1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 6 = ‘strongly agree’) (see Table 5 in Appendix). Exploratory ML factor analysis showed that these three items formed only one factor with eigenvalues >1 (Cronbach’s α = 0.703). The factor scores were a weighted average of items using the standardised loading obtained from the second-order CFA. A high score was considered indicative of a high degree of a shared vision capability. The high correlation obtained for this capability between Time 1 and Time 2 surveys (r = 0.89) confirmed our confidence in the reliability of the shared vision scale.

Stakeholder Management Capability

Nine categories of stakeholders (competitors, customers, suppliers, shareholders/owners, employees, communities, government agencies, accountants and research and development providers) were identified from the literature and discussions with pre-test participants (see Table 6 in Appendix). Consistent with previous research (e.g. Aragon-Correa et al. 2008; Buysse and Verbeke 2003; Sharma et al. 2007), we adopted Ajzen and Fishbein’s (1980) approach to measure a firm’s stakeholder management capability in relation to these nine categories. Survey respondents were first asked to use a five-point scale (1 = ‘very low’, 5 = ‘very high’) to rate the level of attention their firm gave to each type of stakeholder in organisational decision making. Respondents were then asked to use a five-point scale (1 = ‘very low’, 5 = ‘very high’) to rate the importance of each type of stakeholder in helping them understand issues their firm was facing. The average value of a stakeholder management capability for each firm was calculated based on each respondent’s ratings of the attention given to each type of stakeholder and the perceived importance of each stakeholder. Exploratory ML factor analysis with varimax rotation showed that the nine items formed two factors with eigenvalues >1 (Cronbach’s α = 0.684 for Factor 1 and 0.688 for Factor 2). The factor scores were a weighted average of the items (within a factor) using the standardised loading obtained from the second-order CFA. A high final score was considered indicative of a high stakeholder management capability. The high correlation obtained for this capability between Time 1 and Time 2 surveys (r = 0.94) confirmed our confidence in the reliability of the stakeholder management scale.

Strategic Proactivity Capability

Three items from Aragon-Correa’s validated scale (1998) were used to measure a firm’s strategic proactivity capability. All items were presented as statements related to the firm, against each of which respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement on a six-point scale (1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 6 = ‘strongly agree’) (see Table 7 in Appendix). Exploratory ML factor analysis showed that the three items formed only one factor with eigenvalues >1 (Cronbach’s α = 0.720). The factor scores were a weighted average of the three items using the standardised loading obtained from the second-order CFA. A high score was considered indicative of a high strategic proactivity capability. The high correlation obtained for this capability between Time 1 and Time 2 surveys (r = 0.89) again confirmed our confidence in the reliability of the strategic proactivity scale.

Financial Performance

Discussions with pre-test participants indicated that respondents would be more likely to offer their general perceptions of their firm’s financial performance but very unlikely to provide specific quantitative data that was commercial-in-confidence in nature. Therefore, consistent with the literature that shows a high correlation and concurrent validity between objective and subjective data on performance, implying that both are valid when calculating a firm’s financial performance (e.g. Dess and Robinson 1984; Homburg et al. 1999), the respondents’ perceptions on three financial performance items—return on assets, net profits to sales and liquidity—were collected. These performance items were drawn from previous research (e.g. Ansoff 1965; Dess and Robinson 1984; Lin et al. 2011). Respondents were asked to rate their firm’s financial performance, over the preceding 6-month period compared to similar firms in their industry sector, using a five-point scale (1 = ‘much worse’ to 5 = ‘much better’) (see Table 8 in Appendix). Exploratory ML factor analysis of these three items showed that they formed only one factor with eigenvalues >1 (Cronbach’s α = 0.912). The factor scores were a weighted average of items using the standardised loading obtained from the second-order CFA. A high score was considered indicative of a high level of financial performance. In the absence of publicly available objective data, the high correlation obtained for financial performance between Time 1 and Time 2 surveys (r = 0.86) confirmed our confidence in the reliability of the financial performance scale.

Control Variables

Consistent with past research indicating that firm size has a significant effect on the association between CSR and financial performance (e.g. Bansal 2005; Moore 2001; Stanwick and Stanwick 1998), the size of a firm, measured by the number of employees employed on a regular basis, was controlled in this study. Recognising that the benefits from CSR might only become fully visible over the long term rather than the short term (Hart and Ahuja 1996), the duration of the firm’s experience ranging from 1 year to >9 years in managing each practice dimension of proactive CSR was the second control variable. Furthermore, as our study was conducted during the global financial crisis (GFC), the potentially negative impact on firm performance of this external influence was treated as a third control variable. This control variable was measured in terms of the extent to which general economic conditions had negatively impacted in the previous 6-month period in relation to three financial indicators (return on assets, net profits to sales and liquidity), using a five-point scale (1 = ‘no impact at all’ to 5 = ‘very high impact’). A high average score was considered indicative of a perceived high negative impact on a firm’s financial performance.

Analysis and Results

Structural equation modelling with LISREL 8.8, which is an inferential data analysis technique allowing the researcher to test prior theoretical assumptions against empirical data statistically (Joreskog and Sorbom 2006), was used to test our hypotheses. We carefully note that structural equation modelling does not prove causality or that the model proposed is valid and reliable; rather, it is a valuable technique for model creation that conveys information about the causal relations in the data, and for testing whether the theoretically and statistically derived model is plausible (Byrne 1998; Williams 1995). In this study, we adopted the concept of probabilistic (not deterministic) causation, which argues that a given factor increases (or decreases) the ‘probability’ of a particular outcome (de Vaus 2001). As suggested by de Vaus (2001), to infer that a probabilistic causal relationship exists between two variables, two basic criteria must be met: (i) there must be a co-variation (or correlation) of predictor and outcome variables and (ii) the assertion that one variable affects the other must make sense or be theoretically plausible.

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations and correlations for all latent variables analysed in this study. All pairs of predictor and outcome variables specified in our model were correlated; and as estimated correlations between these variables were well below the recommended cut-off of 0.70 (Pallant 2007), discriminant validity was also achieved. Furthermore, the structural model proposed and tested in this study draws on RBV theory (Barney 1991; Grant 1991) and prior research (e.g. Aragon-Correa et al. 2008). Meeting these two basic criteria of probabilistic causation demonstrated logically that our structural model was plausible and theoretically sound.

Following the two-step modelling approach of Anderson and Gerbing (1988), we tested and fitted the measurement model to the data through CFA prior to testing the structural model. An initial measurement model, which contained all of the factors loaded on the appropriate latent variables, was first specified. This measurement model, with 10 latent variables and 15 factors, contained 69 parameters to be estimated (15 factor loadings, 45 covariances and 9 error variances). The CFA showed that this measurement model was adequate fit for the data: χ² = 115.51, df = 51, RMSEA = 0.046, CFI = 0.97, IFI = 0.97 and NNFI = 0.95 (see Hair et al. 1998; Ho 2006). All factors were significantly related to the latent variables (p < 0.001) and the standardised factor loadings were all above the value of 0.50. This suggested that convergent validity was established for all constructs. Convergent validity was further confirmed through assessment of the composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) of latent variables defined by more than one factor (including each dimension of proactive CSR and a stakeholder management capability). The CR scores for these constructs ranged from 0.72 to 0.93 and the AVE scores were all above 0.50, suggesting no serious measurement concerns (see Hair et al. 1998).

Having confirmed that the measurement model had an acceptable fit, we then tested the proposed structural model. In this study, we employed the structural equation modelling with multiplicative terms (called moderated structural equation model) which was in line with the work of Kenny and Judd (1984). Following the approach recommended by Baron and Kenny (1986), we created the paths of three CSR dimensions and the interaction term or product of these three variables (interaction between all CSR dimensions) that directly influenced the dependent variable of financial performance. To prove moderation (based on Baron and Kenny’s (1986) suggestion), the interaction of all three CSR dimensions must significantly affect financial performance; there might also be significant direct effects for each CSR dimension but these would not be directly relevant conceptually to testing the moderation hypothesis. To avoid multicollinearity, we first mean-centred the raw data (for each CSR items) and then created the path coefficients and the error variances for the interaction and its multiplicative indicators. We note here that due to some elements of the economic-related proactive CSR (ECON4, ECON5 and ECON7—see Table 4 in Appendix for item details) being associated with the social- and environmental-related proactive CSR, we allowed the error covariance of the economic and social CSR dimensions and of the economic and environmental CSR dimensions to become free in order to take account of an unmeasured variable that may possibly lead to an error in the corresponding parameters.

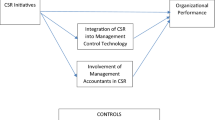

Results of the structural analysis, as shown in Fig. 1, provided a good fit to the data: χ² = 189.47, df = 59, RMSEA = 0.038, CFI = 0.98, IFI = 0.98, NNFI = 0.97. To further evaluate a better-fitting and parsimonious model, we compared the proposed model with an alternative nested model that incorporated the direct paths between all three capabilities and SME financial performance. Although this nested model provided an acceptable fit to the data (χ² = 182.98, df = 56, RMSEA = 0.079, CFI = 0.95, IFI = 0.95, NNFI = 0.90), it did not provide a significant improvement in fit over the proposed model (χ² different test: Δχ² = 6.49, Δdf = 3) and no significant direct effect of any of these capabilities was detected on financial performance. In accordance with parsimony principles (James et al. 2006), this alternative nested model was rejected, and the proposed model was thus used for testing research hypotheses (see Fig. 1). Table 2 provides a summary of the significant direct associations based on the results of the proposed model.

Based on the results as shown in Fig. 1 and Table 2, the adoption of each dimension of proactive CSR by SMEs was influenced slightly differently by each capability. A shared vision capability was significantly associated with environmental-related proactive CSR (γ = 0.11, p < 0.05), providing support for Hypothesis 1c. We found no significant association of a shared vision capability with the economic and social dimensions of proactive CSR; therefore, Hypotheses 1a and 1b were not supported. A stakeholder management capability was significantly associated with all three dimensions of proactive CSR: economic (γ = 0.12, p < 0.05), social (γ = 0.15, p < 0.01) and environmental (γ = 0.11, p < 0.05). Therefore, Hypotheses 2a–2c were supported. Similarly, a strategic proactivity capability was also found to be significantly associated with all proactive CSR dimensions: economic (γ = 0.14, p < 0.01), social (γ = 0.12, p < 0.05) and environmental (γ = 0.11, p < 0.05). These results provided support for Hypotheses 3a–3c. All three capabilities were also found to be significantly positively associated with the interaction between economic, social and environmental dimensions of proactive CSR at p < 0.001 (γ = 0.24 for shared vision; γ = 0.39 for stakeholder management and γ = 0.32 for strategic proactivity).

Each dimension of proactive CSR affected financial performance differentially. Economic-related proactive CSR was found to have a significant positive association with SME financial performance (β = 0.40, p < 0.001), providing support for Hypothesis 4a. No direct association was observed for social- and environmental-related proactive CSR, thereby providing no support for Hypotheses 4b and 4c. The interaction of all three CSR dimensions was positively significant (β = 0.52, p < 0.001). This result indicated the importance of the interaction between economic, social and environmental dimensions of proactive CSR in positively moderating the capacity of an SME to deploy each individual CSR dimension to generate financial performance, thereby providing support for Hypothesis 4d.

As structural equation modelling can also be used as a technique for understanding mediation in the model (Bollen 1989), we conducted a further additional analysis to assess the mediating role of the interaction between all three CSR dimensions on the ‘capability-performance’ association. Following recommendations outlined by MacKinnon et al. (2002), we calculated the coefficients using LISREL’s effect decomposition statistics, where a finding of a statistically significant ‘indirect’ effect would indicate that the association between the observed capability and firm financial performance occurs through the interaction between CSR dimensions (given that the only indirect path that all of the three capabilities could take to influence SME financial performance was through such an interaction). The results revealed that all three capabilities had a statistically significant indirect association with SME financial performance (standardised coefficient for indirect effect of shared vision = 0.11, p < 0.05; for stakeholder management = 0.23, p < 0.001; and for strategic proactivity = 0.15, p < 0.01). Therefore, our general expectation of the plausible importance of the interaction of economic, social and environmental dimensions of proactive CSR in enabling SMEs to successfully deploy all three capabilities for an improvement in financial performance was confirmed.

With regard to the control variables, firm size was found to have a direct positive association with all dimensions of proactive CSR [economic (γ = 0.16, p < 0.01), social (γ = 0.15, p < 0.05) and environmental (γ = 0.13, p < 0.01)], the interaction between CSR dimensions (γ = 0.16, p < 0.01) and SME financial performance (γ = 0.11, p < 0.05). On this basis, it was concluded that the larger the SME the more likely is the adoption of proactive CSR and the access to related financial benefits. The GFC was found to be negatively associated with economic-related proactive CSR (γ = −0.11, p < 0.05), the CSR interaction (γ = −0.12, p < 0.05) and financial performance (γ = −0.39, p < 0.001). No association was observed, between the duration of a firm’s experience with the management of CSR, on either of any proactive CSR dimension or associated financial returns.

While not the subject of extensive data analysis in this article, a review of the qualitative comments that were collected in conjunction with the quantitative survey reinforced these findings. The majority of respondents who commented stated that their firm had adopted proactive CSR to some extent; however, resource constraints, costs associated with the adoption of such activity, and perceptions that doing so is antagonistic to maximising profits, were highlighted by most as major stumbling blocks to the uptake of full-scale proactive CSR. The high costs imposed by business-related government policies in tough global economic conditions, particularly in relation to climate change initiatives, and the high competitive pressures from import penetration of products from lower cost economies, were identified as major threats to SME survival and the implementation of proactive CSR.

Table 3 presents the list of the research hypotheses proposed in this study, and whether they are supported by the structural equation modelling analysis. As can be seen in this table, of 13 proposed hypotheses, 9 hypotheses were supported.

Discussion

In this study, we sought to examine the role of the economic, social and environmental dimensions of proactive CSR on the association between three specific capabilities (shared vision, stakeholder management and strategic proactivity) and SME financial performance. Our findings show the probability that proactive CSR, rather than representing a business threat and cost burden for SMEs, can provide significant scope for enhancing financial performance and thus contribute to a competitive advantage if its economic, social and environmental dimensions are adopted in an integrated and synergistic manner. Evidence presented in this study of the moderating role of the interaction between CSR dimensions suggests the probability that such interaction represents a necessary mechanism for an improvement in SME financial performance, indicating that SMEs should address the need to incorporate CSR issues into business strategy if they are to remain financially competitive. The result of an indirect effect of each capability on SME financial performance through the CSR interaction found in this study also aligns with RBV theory that suggests adoption of value-creating strategies that make the most effective use of a firm’s capabilities is essential to financial success (Barney 1991; Grant 1991).

Notwithstanding support shown for the integrated use of the three capabilities, the importance of each capability in relation to each dimension of proactive CSR has been shown to be slightly different. The economic and social dimensions of proactive CSR were found to be influenced by both stakeholder management and strategic proactivity capabilities, but not by a shared vision capability. The finding of a positive influence of stakeholder management and strategic proactivity capabilities suggests that an SME’s ability to manage sometimes competing stakeholder interests and its ability to initiate changes in strategic policies for capitalising new opportunities are of key importance in proactively developing CSR practices that reduce costs and ensure long-term firm survival in a rapidly changing business environment, whilst at the same time support social cohesion and equity. The finding of no influence of a shared vision capability on the adoption of economic-related proactive CSR may be explained by the greater degree of autonomy and scope for action in allocating organisational resources that decision-making control provides to SME owner–managers (Jenkins 2009). In combination with the priority SME owner–managers give to the achievement of a firm’s financial goals (European Commission 2003), this control can reduce the incentive to work closely with employees in developing shared goals embracing economic-related proactive CSR. In regard to the non-influence of a shared vision capability on the adoption of social-related proactive CSR, this could reflect an acknowledgement, notwithstanding the substantial decision-making autonomy of SME owner–managers, that productive and satisfied employees do contribute to business success; hence, a willingness on the part of some SME owner–managers to engage voluntarily, at least to some degree, in social-related proactive CSR to foster employee well-being and motivation, even in the absence of clear common social goals between the owner–manager and their employees.

In contrast to the economic and social dimensions, the environmental dimension of proactive CSR was found to be influenced by all the three capabilities. These findings, which are in line with those reported by Aragon-Correa et al. (2008), imply that the successful adoption of environmental-related CSR requires: a shared vision capability to serve as a basis for building commitment to an environmental culture, developing employees’ environmental skills, and shaping responsible behaviour (Hart 1995; Ramus and Steger 2000); a stakeholder management capability to enable collaboration with a wide stakeholder set in order to allocate resources effectively for generating a proactive approach towards an environmental practice (Hart 1995; Sharma et al. 2007); and a strategic proactivity capability to influence business strategy towards capitalising on new opportunities created by emerging environmental issues (Aragon-Correa 1998).

Turning now to SME financial performance, only one of the three dimensions of CSR, economic-related proactive CSR, was shown to have a direct association with SME financial performance. This result suggests the probability of economic responsibility being the only CSR dimension that directly predicts improvement in SME financial performance. Interestingly, our finding of no direct association between the social and environmental dimensions of proactive CSR and SME financial performance is contrary to other previous empirical research (e.g. Aragon-Correa et al. 2008; Hillman and Keim 2001). One plausible explanation for this outcome may be that previous studies have not included the economic dimension of CSR in their model; and therefore, their results may be misleading. We tested this possibility by performing an additional analysis that excluded the economic dimension of proactive CSR from the model; and as expected, a significant direct association on SME financial performance was found for both CSR dimensions (β = 0.39 for social CSR and β = 0.28 for environmental CSR, p < 0.001).

Further to the preceding discussion, we note that the finding of no direct association for either social or environmental dimension of proactive CSR on SME financial performance may reflect the significant costs involved in their implementation. If the difference between costs and financial returns is too great in the short term, then SMEs with limited resources are unlikely to adopt social- and environmental-related CSR and be willing to wait on superior financial returns over the long term (Bianchi and Noci 1998; Brammer and Millington, 2006). However, the evidence that the association between each individual CSR dimension and SME financial performance is contingent on or moderated by the interaction of all three CSR dimensions found in this study suggests that the adoption of both social and environmental CSR dimensions is necessary for reinforcing the effectiveness of economic-related proactive CSR, and to make more likely the improvements in financial performance that are crucial to long-term success for SMEs. In other words, in order to enhance their economic-related CSR and maximise the financial benefits, SMEs may need to identify and adopt those elements of social- and environmental-related CSR for which they are best equipped.

Implications, Limitations and Future Research Directions

Implications

Contrary to the traditional assumption that a lack of slack resources prevents SMEs from successfully implementing proactive CSR (e.g. Bansal 2005; Brammer and Millington 2006; Gadenne et al. 2008; Palmer 2000), our findings show the probability that in the SME context the adoption of proactive CSR can be related to specific organisational capabilities, and that proactive CSR across its three dimensions can lead to superior financial performance. These findings are in line with RBV theory and lend support to the argument that size, a common proxy for organisational resources, is a relevant but not deterministic factor for the adoption of proactive CSR in SMEs. The evidence of the simultaneous positive influence of firm size (and the general thrust of the anecdotal evidence found in the qualitative data) and organisational capabilities on proactive CSR revealed in this study, suggests that SMEs which do have the set of three capabilities in place—shared vision, stakeholder management and strategic proactivity—could overcome the absence of (existing) slack resources to engage in proactive CSR across its three dimensions. The study findings are also consistent with RBV theory that resources on their own are unlikely to deterministically drive competitive strategy development, and that it is the integration and coordination of multiple resources to create capability which drives strategy and performance improvement (Barney 1991; Grant 1991).

The direct effect on SME financial performance of economic-related proactive CSR (and the interaction effect of all three CSR dimensions) is the key finding of this study. Clearly, if cost-based and/or differentiation-based competitive advantages are to be gained then the economic dimension of proactive CSR, shown here to contribute directly to improvement in SME financial performance, needs to be adopted in conjunction with the social and environmental dimensions of proactive CSR. While resource constraints might limit full adoption of a proactive CSR agenda, SMEs have the opportunity to secure improvements in financial performance by leveraging three specific organisational capabilities to implement the particular sub-set of social-and environmental-related CSR they are best equipped to adopt for supporting economic-related CSR.

The study findings also have practical implications for SME owner–managers juggling competing resource demands and the need to take strategic actions aimed at achieving a competitive edge in the marketplace. Specifically, the findings suggest that SMEs wishing to adopt proactive CSR as a strategic action should give a priority in resource allocation to the development of their shared vision, stakeholder management and strategic proactivity capabilities; it is by leveraging these three capabilities to engage in proactive CSR across its three dimensions that superior financial performance can be achieved by SMEs.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

In interpreting the study findings, several limitations to the research need to be borne in mind. First, difficulties in generalising results, from sample to population to other sectors/industries and from Australia to other economies, cannot be discounted. Although we attempted to minimise differences between SMEs by sampling only in a single industry sector, SMEs are by nature quite heterogeneous in their characteristics; and, although a sample size of 171 was sufficient for the structural equation analysis, it might not be sufficient to assure representativeness of all SMEs in the sector. The possibility of some regulatory requirements being ambiguously defined, thus causing difficulty for SME managers in differentiating between reactive and proactive CSR, also needs to be acknowledged. Furthermore, the findings are limited by the self-report nature of the data collection process; in particular, due to commercial-in-confidence concerns and the absence of publicly available objective data on financial performance of (owner-managed) SMEs, we were unable to test the correlation between subjective self-reported data and objective data.

Second, we note that structural equation modelling is not an analytical method for discovering causes, but rather a statistical method applied to a structural model formulated by the researcher on the basis of prior theoretical considerations. In this study, the recursive relationships between variables specified was based on the RBV theory which indicates that superior performance results from a (existing) strategy efficiently exploiting and enhancing a firm’s (existing) capabilities (Grant 1991); and we used the 6-month time lag in data collection to allow for temporal ordering of independent/mediating and dependent variables. However, this 6-month time gap was insufficient time to establish ‘proof of causality’. Also, it is possible that the association between capabilities, proactive CSR and financial performance may be non-recursive characterised by a feedback loop; for example, an improvement of SME financial performance may stimulate slack resources, and thus increases the probability of their future engagement in proactive CSR. Without testing this reversed relationship—coupled with the fact that there may also be other models that fit the data at or near to the same degree, and other unknown intervening variables may lead to an error in the analysis—the ‘deterministic’ causation (meaning that a cause must always be followed by an effect) cannot be confirmed, and only the ‘probabilistic causation’, where the findings of causal relationships are not imply correctness or truth but only plausibility, can be inferred (de Vaus 2001; MacCallum and Austin 2000).

Future extensions of this study might include a quasi-experimental longitudinal study over a longer time period, with a larger sample size and a test of non-recursive relationships, to confirm the importance of proactive CSR on the association between capabilities and financial performance, and thus to allow for broader generalizability in findings. A study linking the model variables to additional sources of data that take into account objective measures, and which include multiple informants and case studies, could provide multi-level insights. Another possibility is a research study comparing proactive CSR in large firms and SMEs that further explores the extent to which SME resource disadvantages can be offset by capabilities that derive from their special organisational characteristics. Such research could yield high value to individual SME owner–managers and government policy makers alike.

References

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Amit, R., & Schoemaker, P. J. H. (1993). Strategic assets and organizational rent. Strategic Management Journal, 14(1), 33–46.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practices: A review and recommended two step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423.

Anseel, F., Lievens, F., Schollaert, E., & Choragwicka, B. (2010). Response rates in organizational science, 1995–2008: A meta-analytic review and guidelines for survey researchers. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25, 335–349.

Ansoff, H. I. (1965). Corporate strategy. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Aragon-Correa, J. A. (1998). Strategic proactivity and firm approach to the natural environment. Academy of Management Journal, 41(5), 556–567.

Aragon-Correa, J. A., Hurtado-Torres, N., Sharma, S., & Garcia-Morales, J. V. (2008). Environmental strategy and performance in small firms: A resource-based perspective. Journal of Environmental Management, 86(1), 88–103.

Arbuthnot, J. J. (1997). Identifying ethical problems confronting small retail buyers during the merchandise buying process. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(7), 745–755.

Armstrong, J., & Overton, T. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14, 396–402.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2001). Small business in Australia. Canberra: Australian Government Printers.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2009). International trade in goods and services in Australia. Canberra: Australian Government Printers.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2010). Australia’s environment: Issues and trends, Jan 2010. Canberra: Australian Government Printers.

Bansal, P. (2005). Evolving sustainably: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strategic Management Journal, 26(3), 197–218.

Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Beaver, G., & Jennings, P. (2000). Editorial overview: Small business, entrepreneurship and enterprise development. Strategic Change, 9(7), 397–403.

Becker-Olsen, K. L., Cudmore, B. A., & Hill, R. P. (2006). The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 59(1), 46–53.

Benn, S., Dunphy, D., & Griffiths, A. (2006). Enabling change for corporate sustainability: An integrated perspective. Australasian Journal of Environmental Management, 13(3), 156–165.

Berry, M. A., & Rondinelli, D. A. (1998). Proactive corporate environment management: A new industrial revolution. The Academy of Management Executive, 12(2), 38–50.

Bianchi, R., & Noci, G. (1998). Greening SMEs competitiveness. Small Business Economics, 11(3), 269–281.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley.

Brammer, S., & Millington, A. (2006). Firm size, organizational visibility and corporate philanthropy: An empirical analysis. Business Ethics: A European Review, 15(1), 6–18.

Burke, L., & Logsdon, J. M. (1996). How corporate social responsibility pays off. Long Range Planning, 29(4), 494–502.

Buysse, K., & Verbeke, A. (2003). Proactive environmental strategies: A stakeholder management perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 24(5), 453–470.

Byrne, B. M. (1998). Structural equation modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Academy of Management Review, 4(1), 497–505.

Chandler, G. N., & Hanks, S. H. (1993). Measuring the performance of emerging business: A validation study. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(5), 391–408.

Chang, D., & Kuo, L. R. (2008). The effects of sustainable development on firms’ financial performance—an empirical approach. Sustainable Development, 16, 365–380.

de Vaus, D. A. (2001). Research design in social research. London: SAGE.

Dess, G. G., & Robinson, R. B. (1984). Measuring organizational performance in the absence of objective measures: The case of the privately-held firm and conglomerate business unit. Strategic Management Journal, 5(3), 265–275.

Du, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2007). Reaping relational rewards from corporate social responsibility: The role of competitive positioning. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 24(3), 224–241.

Dun and Bradstreet. (2009). Australia’s premier source of business intelligence just got even better (Dun & Bradstreet, Australia).

Dyllick, T., & Hockerts, K. (2002). Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment, 11(2), 130–141.

Ellen, P. S., Webb, D. J., & Mohr, L. A. (2006). Building corporate associations: Consumer attributions for corporate socially responsible programs. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(2), 147–157.

European Commission. (2003). Responsible entrepreneurship: A collection of good practice cases among small and medium-sized enterprises across Europe (Bruxelles, Belgium).

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Marshall: Pitman.

Gadenne, D. L., Kennedy, J., & McKeiver, C. (2008). An empirical study of environmental awareness and practices in SMEs. Journal of Business Ethics, 10, 1–19.

Gerrans, P., & Hutchinson, B. (2000). Sustainable development and small to medium-sized enterprises: A long way to go. In R. Hillary (Ed.), Small and medium-sized enterprises and the environment (pp. 75–81). Sheffield: Greenleaf Publishing.

Gielissen, R. B. (2011). Why do customers buy socially responsible products? International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(3), 21–35.

Goffee, R., & Scase, R. (1995). Corporate realities: The dynamics of large and small organisations. London: International Thomson Business Press.

Graafland, J., van de Ven, B., & Stoffele, N. (2003). Strategies and instruments for organising CSR by small and large businesses in the Netherlands. Journal of Business Ethics, 47(1), 45–60.

Grant, R. M. (1991). The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. California Management Review, 33(3), 114–135.

Groza, M. D., Pronschinske, M. R., & Walker, M. (2011). Perceived organizational motives and consumer responses to proactive and reactive CSR. Journal of Business Ethics, 102, 639–652.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall International.

Hammann, E., Habisch, A., & Pechlaner, H. (2009). Values that create value: Socially responsible business practices in SMEs—empirical evidence from German companies. Business Ethics: A European Review, 18(1), 37–51.

Hart, S. L. (1995). A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Academy of Management Review, 20(4), 986–1014.

Hart, S. L., & Ahuja, G. (1996). Does it pay be green?: An empirical examination of the relationship between emission reduction and firm performance. Business Strategy and the Environment, 5, 30–37.

Hart, S. L., & Milstein, M. B. (2003). Creating sustainable value. Academy of Management Executive, 17(2), 56–69.

Henriques, I., & Sadorsky, P. (1999). The relationship between environmental commitment and managerial perceptions of stakeholder importance. Academy of Management Journal, 42(1), 87–99.

Hillary, R. (2000). Small and medium-sized enterprises and the environment. Sheffield: Greenleaf Publishing.

Hillman, A. J., & Keim, G. D. (2001). Shareholder value, stakeholder management, and social issues: What’s the bottom line? Strategic Management Journal, 22(2), 125–139.

Ho, R. (2006). Handbook of univariate and multivariate data analysis and interpretation with SPSS. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC.

Homburg, C., Krohmer, H., & Workman, J. P. (1999). Strategic consensus and performance: The role of strategy type and market-related dynamism. Strategic Management Journal, 20(4), 339–357.